Abstract

Background

Gap Park in Sydney, Australia has historically been recognised as a suicide jumping site. In 2010–2011 the Gap Park Masterplan initiative implemented a series of suicide prevention measures. This study applied a mixed-methods design to evaluate the effectiveness of the Masterplan in reducing suicides.

Methods

Data from the Australian National Coronial Information System (NCIS) was examined to compare suicides at Gap Park before and after the Masterplan was implemented. This was complemented with qualitative data from interviews with police officers who respond to suicidal behaviours at Gap Park.

Findings

Joinpoint analysis of NCIS data showed a non-significant upward trend in jumping suicides during the study period. A significant upward trend in suicides was seen for females before the implementation of the Masterplan (2000–2010), followed by a significant downward trend from the implementation period onwards (2010–2016) for females: however, a non-significant upward trend for males was observed. Qualitative analysis of police interviews identified six key themes: romanticism and attraction at hotspots, profiles and behavioural patterns of suicidal individuals, responding to a person in a suicidal crisis, repeat attempts, means restriction, and personal impacts on police officers.

Interpretation

The mixed-method study provided important insights, suggesting the Gap Park Masterplan has contributed to a reduction in female, but not in male jumping suicides. Further qualitative information from police officers suggested that the safety barriers were not difficult to climb, and may be more of a visual or psychological barrier. However, the effectiveness of CCTV and alarms in the detection and location of suicide attempters was highlighted.

Funding

Lifeline Research Foundation

Keywords: Suicide, Hotspots, Jumping, Mixed-methods

Research in Context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science with the terms ‘hotspot’ or ‘jumping site’ or ‘means restriction’ AND ‘suicid*’ or ‘self-harm’ without language or time limit. A systematic review and a meta-analysis of research on interventions to reduce suicides at hotspots were identified, both of which highlighted the need for ongoing assessment and evaluation to strengthen the evidence base for interventions at suicide hotspots. One 2014 study specifically assessed the effectiveness of the Gap Park Masterplan. There were no statistically significant trends in reductions in suicides and further research over a longer time-period was recommended.

Added value of this study

A major strength of this study is the application of a mixed-methods study design which provided important contextual information for understanding and interpreting the quantitative results. Police officers confirmed that the CCTV and alarms were effective in detecting and locating suicidal individuals, thus providing more opportunities for police to intervene. However, police believed the fencing was not difficult to climb and thus not a significant deterrent. Given the significant reduction in suicides for females, it is possible that the fencing may be more of a physical (of even psychological) barrier for females than for males.

Implications of all the available evidence

The results of this study suggest that the Gap Park suicide prevention interventions appear to be working for females, but not for males. It is possible that some unusual peaks in both male and female suicides may have coincided with sensationalised media reporting of suicides at the site. Therefore, a comprehensive media analysis would be valuable to understand the impact of media reporting on suicides at hotspots. The insights gained from police officers should be considered when implementing suicide hotspot prevention programs. It will also be important to ensure that police responding to suicidal incidents are provided with appropriate support.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Suicide hotspots are accessible and usually public sites, including cliffs, tall structures, railway tracks, and isolated locations that are frequently used for suicide [1]. In recent years there has been debate over the use of the term, ‘hotspot’ and whether this language may be demonising or suggest that a suicide at a well-known location is less tragic than other suicides [2]. We concur that it is critical to avoid stigmatising language when referring to suicide, but believe that the proposed alternative, ‘frequently used location’ [2] seems imprecise [3]. Consistent with Pirkis and colleagues [3] we have decided to use the term ‘hotspot’ for the purpose of this paper as it has a precise and well-defined meaning in the scientific literature.

Research on interventions to prevent suicides at suicide hotspots has shown mixed evidence for their effectiveness. For example, a systematic review [1] and a meta-analysis [4] assessing the effectiveness of hotspot interventions, found strong evidence for reducing access to means in preventing suicides at hotspots, and promising, but weaker evidence for other interventions (i.e., encouraging help-seeking through signs and telephones, increasing the likelihood of intervention by a third party, and encouraging responsible media reporting of suicides). To further understand the impact of combined suicide prevention initiatives at hotspots the current study investigated the effectiveness of Australia's Gap Park Masterplan.

Gap Park, situated in a coastal escarpment area in Sydney, Australia has historically been a recognised hotspot for jumping suicides. In 2010 the Woollahra Council, in collaboration with several partners, established the Gap Park Self-Harm Minimisation Masterplan project. This involved the implementation of a series of suicide prevention initiatives including fencing (Photo 1), CCTV surveillance, protocols with police and the installation of phone booths and promotion of the Lifeline Suicide Hot Spot Emergency Phone Service. As preliminary evaluation of these initiatives was undertaken in 2012 [5], it is now timely to more deeply examine the efficacy of the project. This study therefore aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the Gap Park Masterplan in reducing suicides through the application of a convergent parallel mixed-methods design [6]. The quantitative component analysed trends in suicide numbers before, during and after the intervention. The intervention period was distinguished from postintervention given that publicity during the implementation of the Masterplan may have potentially impacted on suicides. The qualitative component, conducted concurrently, provided wider contextual information through interviews with experienced police officers responding to suicide interventions at Gap Park.

Photo 1.

Gap park fencing.

2. Method

2.1. Data collection

We followed the guidelines for Good Reporting of A Mixed Methods Study (GRAMMS) [7] which comprises justification for using a mixed-methods approach; description of design in terms of purpose, priority and sequence of methods; description of each method in terms of sampling, data collection and analysis; description of where integration has occurred, how it has occurred; any limitations of one method associated with the presence of another method; and any insights gained from mixing or integrating methods. The mixed-method design of the present study enables a triangulation of quantitative and qualitative research methods to add richness and depth to the research findings.

2.1.1. Quantitative component

The Gap Park Masterplan area occupies a relatively small proportion of the wider postcode area of 2030 in Sydney. Previous analysis on the efficacy of the Masterplan examined suicide data for the entire 2030 postcode area [5]. However, to evaluate the effectiveness of the Gap Park suicide prevention initiatives, it is important to also specifically examine the Masterplan area, and over a longer time-period. Therefore, two separate searches were conducted for the overall postcode 2030 and the Gap Park Masterplan area only. An initial search was conducted in the National Coronial Information System (NCIS) for closed cases (by the coroner) where a suicide occurred for 2000-2016, within postcode 2030. A more refined search for cases that occurred within the Gap Park Masterplan area was conducted manually to examine the details of each case and excluded those that occurred in areas outside of the Masterplan area. Where there was any ambiguity regarding geographic boundaries, researchers consulted local police and council for guidance. Background information about each suicide were obtained.

2.2. Data statement

Special permission was obtained to extract data from the National Coronial Information System which is managed by the Victorian Department of Justice and Community. The authors do not have authority to release or share this data.

2.2.1. Qualitative component

A senior police officer from the local Waverley police station was assigned by the NSW police to recruit officers trained in responding to suicidal individuals at Gap Park to participate in the study. The interviewer, a registered psychologist, contacted all officers to invite them to participate and to organise interview times. No incentives were offered, and all officers contacted agreed to participate. The interviews were conducted between March-June 2018. A total of eight individual face-to-face interviews were conducted with police officers (seven males and one female): an adequate number in this context to obtain data saturation in non-probabilistic sampling [8]. The semi-structured interviews (see Supplementary material) took between 30 min and one and a half hours, and were recorded and professionally transcribed. All participants were provided with written information about the project and consented to participate.

2.2.2. Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (2017/558), the Justice Human Research Ethics Committee (JHREC) (ref no: CF/18/8733), and the NSW Police Force.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Analyses comparing the characteristics of the suicide cases from the NCIS (i.e., demographics, alcohol use, and lifetime suicidality) at the time-points of preintervention, intervention, and postintervention were conducted using Chi-square tests. Joinpoint regression analysis was used to test changes in trends in numbers of suicides for 2000-2016. Joinpoint regression enables the identification of the best-fitting points where a statistically significant change in trend occurred and calculates the annual percentage change (APC) in suicides with the 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). The analyses were performed using the Joinpoint Regression Program version 4.2.0.1 and SPSS 25.0.

The qualitative data was analysed using generic thematic analysis [9]. An inductive or data-driven approach was applied, where the coding and theme development were directed by the content of the data [10]. Initial coding was undertaken independently by two researchers (VR and KK). To ensure validity of analysis, the researchers then worked together to group coded items into overarching themes with supporting verbatim examples from the transcripts. Using an iterative process, themes were reassessed and interpretations with any discrepancies negotiated until consensus was reached.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative analysis

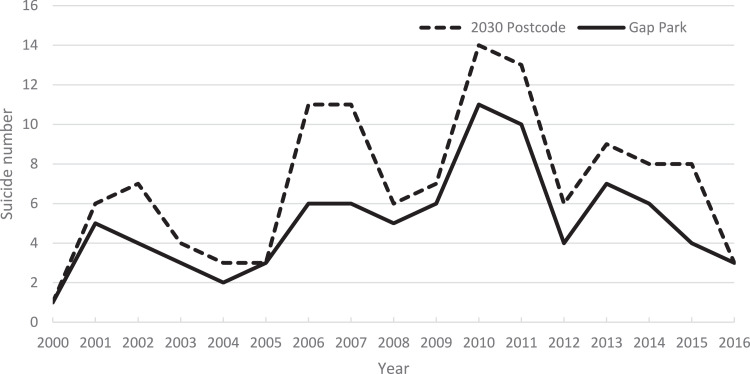

In 2000-2016, there was a total of 120 confirmed suicides by jumping (96% of all suicides) within postcode 2030, where Gap Park is located. Of these, 86 suicides (71.7%), comprised of 48 male and 38 females were confirmed to have occurred within the Gap Park Masterplan area. The highest suicide mortality was observed during the time of the Masterplan implementation in 2010–2011, with numbers gradually decreasing after this time (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Suicides by the Postcode 2030 and the Gap Park Masterplan area, 2000–2016.

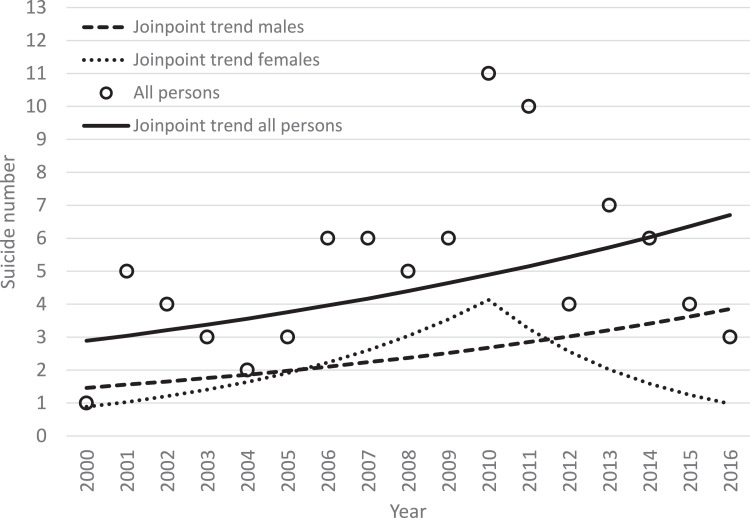

Joinpoint analysis for all suicides within the Gap Park Masterplan area from 2000-2016 (Fig. 2) showed a slight upward trend (APC = 5·41%, 95%CI:−0·38,11·53, p = 0·07). Further analysis by sex presented a similar upward trend in male suicides (APC = 6·23%, 95%CI:−0·41,13·30, p = 0·06). An analysis for females revealed one joinpoint, with an upward trend from 2000-2010 (APC = 16·64%, 95%CI: 8·18, 25·76, p < 0·001) followed by a downward trend from 2010-2016 (APC = -21·27%, 95%CI:-33·14,−7·30, p = 0·01). The joinpoint analysis for all suicides within 2030 postcode area from 2000-2016 showed similar trends.

Fig. 2.

Joinpoint regression analysis by sex at the Gap Park Masterplan area, 2000–2016.

Table 1 shows that in the Gap Park Masterplan area, there was a slight decrease in the proportion of male suicides during the intervention period (2010–2011), followed by an increase in the proportion of suicides after the intervention. Suicides were most prevalent in the 25–44 years age group, in those who did not have a partner, and were employed; however, differences between the groups across three study periods were not significant. There were no significant differences across the study periods for alcohol use or lifetime suicidality.

Table 1.

Characteristics of suicides, before, during and after interventions, Gap Park Masterplan area.

| Preintervention (2000-2009) |

Intervention (2010-2011) |

Postintervention (2012-2016) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | χ2 | p | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 22 | 53·7% | 10 | 47·6% | 16 | 66·7% | 1·80 | 0·408 |

| Female | 19 | 46·3% | 11 | 52·4% | 8 | 33·3% | ||

| Age group | ||||||||

| Below 25 | 6 | 14·6% | 6 | 28·6% | ≤5 | 12·5% | 0·807b | |

| 25 to 44 | 19 | 46·3% | 8 | 38·1% | 12 | 50·0% | ||

| 45 to 64 | 13 | 31·7% | ≤5 | 23·8% | 8 | 33·3% | ||

| 65 + | ≤5 | 7·3% | ≤5 | 9·5% | ≤5 | 4·2% | ||

| Marital Status | ||||||||

| Not married/de factoa | 19 | 46·3% | 13 | 61·9% | 12 | 50·0% | 6·13 | 0·190 |

| Married/de factoa | 15 | 36·6% | ≤5 | 14·3% | ≤5 | 16·7% | ||

| Unknown | 7 | 17·1% | ≤5 | 23·8% | 8 | 33·3% | ||

| Employment | ||||||||

| Employed | 22 | 53·7% | 10 | 47·6% | 8 | 33·3% | 0·410b | |

| Unemployed | ≤5 | 7·3% | ≤5 | 9·5% | ≤5 | 8·3% | ||

| Out of the workforce | ≤5 | 12·2% | 6 | 28·6% | ≤5 | 20·8% | ||

| Unknown | 11 | 26·8 % | ≤5 | 14·3% | 9 | 37·5% | ||

| Alcohol consumed | ||||||||

| Yes | 6 | 14·6% | ≤5 | 14·3% | ≤5 | 16·7% | 1·000b | |

| No/unknown | 35 | 85·4% | 18 | 85·7% | 20 | 83·3% | ||

| Lifetime suicidality | ||||||||

| Yes | 11 | 26·8% | 8 | 38·1% | 13 | 54·2% | 4·85 | 0·088 |

| None known | 30 | 73·2% | 13 | 61·9% | 11 | 45·8% | ||

A de facto relationship, under the Family Law Act 1975, is defined as a relationship between two people (who are not legally married or related by family) who, having regard to all of the circumstances of their relationship, lived together on a genuine domestic basis.

Rows x Columns equivalent of Fisher's exact (2-sided) used for analyses where less than 80% of the cells have expected values of 5 or less.

Table 2 shows that similar patterns were seen for the Gap Park Masterplan. The exception was previous lifetime suicidality, which was which was significantly higher at postintervention (p = 0·01).

Table 2.

Characteristics of suicides, before, during and after interventions in Postcode 2030.

| Preintervention (2000-2009) |

Intervention (2010-2011) |

Postintervention (2012-2016) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | χ2 | p-value | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 36 | 61·0% | 12 | 44·4% | 25 | 73·5% | 5·35 | 0·069 |

| Female | 23 | 39·0% | 15 | 55·6% | 9 | 26·5% | ||

| Age Group | ||||||||

| Below 25 | 6 | 10·2% | 6 | 22·2% | ≤5 | 8·8% | 0·486b | |

| 25 to 44 | 34 | 57·6% | 10 | 37·0% | 16 | 47·1% | ||

| 45 to 64 | 15 | 25·4% | 8 | 29·6% | 12 | 35·3% | ||

| 65 + | ≤5 | 6·8% | ≤5 | 11·1% | ≤5 | 8·8% | ||

| Marital Status | ||||||||

| Not married/de factoa | 32 | 54·2% | 15 | 55·6% | 18 | 52·9% | 3·44 | 0·486 |

| Married/de factoa | 19 | 32·2% | ≤5 | 18·5% | 8 | 23·5% | ||

| Unknown | 8 | 13·6% | 7 | 25·9% | 8 | 23·5% | ||

| Employment | ||||||||

| Employed | 28 | 47·5% | 12 | 44·4% | 15 | 44·1% | 0·430b | |

| Unemployed | 6 | 10·2% | ≤5 | 11·1% | ≤5 | 5·9% | ||

| Out of the workforce | 7 | 11·9% | 8 | 29·6% | 8 | 23·5% | ||

| Unknown | 18 | 30·5% | ≤5 | 14·8% | 9 | 26·5% | ||

| Alcohol consumed | ||||||||

| Yes | 9 | 15·3% | ≤5 | 18·5% | 8 | 23·5% | 0·99 | 0·610 |

| No/unknown | 50 | 84·7% | 22 | 81·5% | 26 | 76·5% | ||

| Lifetime suicidality | ||||||||

| Yes | 15 | 25·4% | 8 | 29·6% | 19 | 55·9% | 9.24 | 0·010 |

| None known | 44 | 74·6% | 19 | 70·4% | 15 | 44·1% | ||

A de facto relationship, under the Family Law Act 1975, is defined as a relationship between two people (who are not legally married or related by family) who, having regard to all of the circumstances of their relationship, lived together on a genuine domestic basis.

Rows x Columns equivalent of Fisher's exact (2-sided) used for analyses where less than 80% of the cells have expected values of 5 or less.

3.2. Qualitative analysis

Six themes were identified: (1) romanticism and attraction; (2) profiles and behavioural patterns; (3) responding to a person in a suicidal crisis; (4) follow-up care and repeat attempts; (5) means restriction; and (6) personal impacts on police officers.

3.2.1. Romanticism and attraction

Police officers described the Gap Park as iconic, beautiful and known for lethality. It was reported the site is so infamous as a hotspot that people frequently travel long distances (from interstate and abroad). Officers highlighted the peculiarity that suicidal individuals are drawn there despite the proximity of other jumping sites that are easier to access and less visible to the public. It was suggested that spectacular views offer a suicidal person a helicopter view of the world while contemplating ending their life and that the aquatic setting contributes to the attraction, both aesthetically and psychologically.

It often makes me wonder if the fact that they're jumping into the sea and not concrete, if that makes sense? If they're not jumping off a building, if that in some way looking down at the ocean is psychologically easier to jump into than jumping off a building onto concrete or people or cars.

The powerful influence of internet sites on the site's attraction as a hotspot was highlighted as direct influence in numerous cases.

I think mainly from the people that I have asked is simply that they have Googled it. There's YouTube videos and stuff. So, there's a lot of stuff out there that people can access if they just Google… (It is) unfortunately is one of the things that pops up.

3.2.2. Profiles and behavioural patterns

In terms of profiles of suicidal individuals, officers described a mix of gender, and a range of ages and reasons for suicidality. Anecdotally, it was reported that suicidal individuals at Gap Park were mainly 30–40-year-old Caucasian males. Key reasons included relationship, financial and study related problems, and mental health issues. Officers suggested there were more suicidal behaviour at Christmas, New Year, and Valentine's Day. Call-outs were more likely during the night, or at sunrise or sunset.

I find the Gap is about love, money, study. All ages, all nationalities. I think the lowest age I had was 17 right up to probably 90. So, it literally captures everyone. People that visit Australia, people that are born in Australia, all races, both genders.

Based on their experience, police officers described two categories of suicidal individuals at jumping sites. There are individuals who are resolute in their decision to die, who will go to the site and jump immediately before anyone can intervene. In contrast, other individuals may remain at the site for hours in contemplation; their behaviour suggesting a level of ambivalence. Police described behaviour patterns of pacing and agitation, or standing, sitting or lying on the edge of the jumping site. According to many officers, the longer a person is in this contemplative state, the higher the likelihood of successful intervention. Suicidal people also tend to dispose of their personal possessions at the site, with police describing the removal of numerous personal items, including shoes and socks, associated with increased preparedness to jump.

Police spoke of the difficulties in engaging with individuals who were more resolute in their decision to jump, who were often non-responsive and despondent. However, officers highlighted many cases where these individuals were anxious about jumping and were able to be brought back to safety. Officers also revealed that people at these sites are more likely to be dismissive rather than aggressive towards police officers.

They're despondent, they're non-responsive. They'll ignore you. Sometimes they might say ‘go away’. It's like they're not even hearing us. So they're like signing off on life, they're done…

Officers emphasised that most suicidal people do not want others to witness them jump or to cause any distress to bystanders, including police officers. This was considered to be a reason why people go to Gap Park during the night or during times when it was not expected that there would be others around.

They don't want to do it in front of anyone… I think that's why we have more incidents late at night when there's no-one there. It's pretty rare in the day time.

One person said she choose the spot because it was isolated, and no-one would see her jump – she didn't want it to effect an innocent bystander.

3.2.3. Responding to a person in a suicidal crisis

When responding to a suicidal person, police officers stressed that it is important not to problem-solve, but rather to apply a consequence management approach. As one officer pointed out, problem-solving can sometimes result in emphasising a lack of options (e.g., suggesting new medication/different treatment, only to find that these have already been tried unsuccessfully). As one officer stated: If we delete their options by trying to problem solve, then we're not going to help.

Officers described how they instead talk to the individual about the consequences of their choices and try to re-connect them back to their own life. As well as highlighting the hurt to loved ones left behind and milestones of life that will be missed, police officers also emphasise the traumatising impact their jumping will have on others. This was reported to be a highly effective technique.

Officers described responding to a suicidal person as a form of crisis management. They saw their role as helping the person to safety, after which they would be taken to a health provider. Officers also stressed how building trust was crucial to this process. Active listening without judgement, empathy, warmth and kindness were all described as key to creating a rapport and trust.

We are not mental health professionals in any way, shape or form. We deal with people in crisis, then once we get them out of crisis we take them to a care provider. Warmth and genuineness to help is key.

I don't think there's any textbook that can teach you. Yes, you can learn the communication skills; empathy, rapport. That helps; however, at the end of the day it's down to a connection that you build with that person.

Many officers spoke of the importance of time and patience to effectively intervene with a suicidal person. Despite time being crucial, it was noted that this was also an issue for police with competing demands on their time and under pressure to quickly resolve the situation.

A suicidal person generally will be quite tired, because there's a lot of mental anguish that they've been wrestling for a long period of time that no one has probably ever noticed. So, communicating with them can be quite hard, purely because they're mentally exhausted. So, they take a bit of energy to get involved with and to understand and to assist.

3.2.4. Re-attempts

The importance of appropriate care after a person has been brought to safety was emphasised, as it was reported that many individuals who re-attempt. As one officer stated: It's not just a matter of getting them back over the fence. The importance was highlighted of being genuine and not making false promises to the suicidal individual (e.g., promising to solve child custody or legal issues) as a means to coaxing them back to safety.

I think the most dangerous thing you can possibly do is lie and tell them that you can do things that you can't. So, when you get that person back over the fence you've already broken that trust because then you chuck them in the back of an ambulance and take them up to hospital.

Under current legislation in Australia [11], the procedure after intervening a suicide attempt is for the person to be involuntarily taken by ambulance to a hospital for a mental health assessment. Officers described how suicidal individuals often do not want to go to hospital and subsequently tell hospital staff they are no longer suicidal so they can be released. Police were therefore concerned about patients receiving appropriate treatment at the hospital and being discharged before it was safe to do so.

They know they're going to hospital if the cops turn up, and no one – they don't want to go to hospital. They've been to hospital before – they don't want to go back to hospital. They don't want the medication, they don't want the stigma of being locked in a white room and fed full of pills.

Officers gave a number of examples where people were released from hospital, only to return days or even hours later to die by suicide. The need to improve communication between emergency responders, hospital staff and mental health teams to ensure the best possible outcomes was described as critical.

So my main aim is to get that person to be as honest as possible, and to be as raw as possible to the people that they speak to in order to get the help they need. So when they do get released they're not straight back up there.

3.2.5. Means restriction

There was a consensus that while the fencing is not a strong deterrent to suicide, the CCTV and alarms are extremely effective in saving lives through detection and location of suicide attempters (which is challenging due to the size and geography of the area). The fencing was considered relatively easy to climb and possibly more of a visual or psychological barrier, than a physical barrier. However, climbing the fence sets off sensors which activate an alarm for the security monitoring service and alerts police. Officers spoke of how the introduction of the CCTV and cameras has enabled them to intervene in potential suicides that they would otherwise not have known about.

The biggest impact that those cameras have had is the ability for us to get up there to try and intervene. I've seen a lot of suicide attempts where we go up there because of the (alarm) activations – then you are able to speak to that person, and after a period of time of discussion, they do come back.

You have seen people get to the Gap and go back and forth on the correct side. Then once they jump that fence, they jump. So, it could be that's a barrier for them to think, ‘am I going to do it? ‘

One negative aspect is that following an intervention, individuals are aware that the CCTV and alarms will notify police. For some suicidal individuals, this means if they cross the fence in future, they will jump immediately to avoid being intercepted.

The next time that they do go up, they are aware that those cameras are there, and they don't muck around the next time. …then they know if they don't do it quickly, you're going to come and stop them.

From my experience, people at The Gap… the thought of going to hospital… sometimes it's enough to make them jump, or consider jumping, or refuse to come back for hours.

3.2.6. Personal impacts on police officers

Police officers described responding to a suicide attempt at a jumping site as very different to other types of call outs for police intervention. Whereas police are generally in control of an emergency situation, in a suicide attempt context the suicidal person is in control. Officers described their stress and the extreme caution necessary to avoid saying anything that might inadvertently trigger the person to jump. The need to effectively apply communication techniques and to build a genuine rapport with the suicidal person was cited as critical. Police reported an enormous sense of responsibility to save the person's life, and anxiety about the scrutiny they may face if they failed. Some officers mentioned concerns about the legal ramifications of police losing someone to suicide.

I'm responsible for that person's life and I'm a police officer, and we're here now to try and save this person. But, at the same time, you're also thinking, ‘I've got to be very careful what I say, because if I say the wrong thing and then they jump, am I going to be scrutinised? Am I going to be criticised? Are the family going to blame me?’ Because I said, ‘oh, your family love you’, and they say, ‘I hate my family because I was abused as a child’, and then they jump.

Officers described their own and other officers’ distress at witnessing suicides and how recalling particular incidents (e.g., hearing a person's screams after jumping) can cause ongoing distress. Several officers mentioned that responding to a suicide intervention can be more personal for new recruits who are lacking in experience.

They take it hard … ‘what if I'd said this? Or what if I'd done that?’ They don't realise that the intention for someone to do that has already been made.

Some officers believed there was a perception that asking for help could be interpreted negatively, both professionally and in terms of the stigma attached to mental health issues.

I think everyone is still afraid of what could happen if someone does put their hand up and say, ‘this is affecting me’, or, ‘I've been thinking about this’. Everyone is scared that will flag them, which is not good. But that's the culture, and it's very hard to change.

4. Discussion

This paper presents, to the best of our knowledge, one of the first mixed-method evaluations of suicide prevention hotspots initiatives to be reported. The integration of the suicide trend analysis with qualitative police interviews, or process triangulation [12], provides a deeper understanding of how the suicide prevention initiatives are working, and in doing so, enhances the validity of the results. The study is also the first to apply in-depth interviews with police officers: a method that has enabled us to gain insights from the considerable expertise of front-line officers intervening in suicide attempts.

Examination of quantitative data for 2000-2016 for Gap Park revealed an unusual peak in female suicides in 2010. This may have been potentially influenced by sensationalised media reporting of an inquest into the Gap Park suicide of a young female newsreader at this time [5]. Trend analysis showed a significant drop in female suicides from 2010, coinciding with the implementation of the Gap Park suicide prevention initiatives. In contrast, trends for male suicides showed quite a different pattern and did not appear to have been impacted as much as females by the suicide prevention initiatives. These results are consistent with existing literature, which suggests that females may be more responsive to means restriction than males [13]. Given the known impact of media on suicides [14,15] a comprehensive media analysis would be useful in increasing current understanding of how the media impacts on male and female suicides at hotspots.

Interviews with police officers provided important contextual factors which enhanced understanding of the of quantitative results, and how specific aspects of the Gap Park Masterplan appear to be working. Officers confirmed that the CCTV and alarms were considered very effective in saving lives through detection and location of suicide attempters. However, they emphasised that the fencing at Gap Park is not difficult to climb and may therefore be a more visual or psychological barrier. Given the significant reduction in female suicides, it is possible that the fence could be more of a physical, or even psychological barrier for women.

The interviews also provided valuable insights into the profiles and behaviours of suicidal individuals, and effective techniques for intervening in suicide attempts. Police officers also highlighted the dangers of information available on the internet in influencing individual's decisions to jump from at Gap Park. The judicious placement of Lifeline's crisis support and suicide prevention information, so it appears in searches pertaining to suicide at Gap Park is a potentially useful strategy to minimise the harm of the internet. Officers spoke of the significant personal stressors involved with responding to suicides and suicide attempts, and of how help-seeking was not viewed positively due to the stigma of mental health issues. As with all first responders it is vital that more opportunities are made available to access help and support when needed [16].

A major strength of this study is the novel application of a mixed-methods approach to evaluation. However, a clear limitation is that due to suicide being a rare event, the small numbers in the analysis make it difficult to detect statistically significant changes in trends. In addition, it was not possible to obtain accurately recorded suicide attempt data for the site. Continued monitoring of suicide data as it becomes available will be critical in evaluating the long-term effectiveness of the Gap Park suicide prevention measures.

Declaration of competing interest

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The funding body did not have any role in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report. We acknowledge the Department of Justice and Regulation for proving access to the Australian National Coronial Information System (NCIS).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100265.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Cox G.R., Owens C., Robinson J., Nicholas A., Lockley A., Williamson M. Interventions to reduce suicides at suicide hotspots: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owens C. “Hotspots” and “copycats”: a plea for more thoughtful language about suicide. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(1):19–20. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pirkis J., Krysinska K., Cheung Y.T., San Too L., Spittal M.J., Robinson J. “Hotspots” and “copycats”: a plea for more thoughtful language about suicide–Authors' reply. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(1):20. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00548-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pirkis J., San Too L., Spittal M.J., Krysinska K., Robinson J., Cheung Y.T. Interventions to reduce suicides at suicide hotspots: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(11):994–1001. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00266-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lockley A., Cheung Y.T., Cox G., Robinson J., Williamson M., Harris M. Preventing suicide at suicide hotspots: a case study from Australia. Suicide Life‐Threaten Behav. 2014;44(4):392–407. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creswell J.W., Clark V.L. Sage publications; 2017. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'cathain A., Murphy E., Nicholl J. The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13(2):92–98. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2007.007074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guest G., Bunce A., Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradbury-Jones C., Breckenridge J., Clark M.T., Herber O.R., Wagstaff C., Taylor J. The state of qualitative research in health and social science literature: a focused mapping review and synthesis. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2017;20(6):627–645. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 11.New South Wales Government. Mental Health Act 2007 (NSW). Accessed 2 June 2019. https://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/#/view/act/2007/8.

- 12.O'Cathain A., Murphy E., Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ. 2010;341:c4587. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yip P.S., Caine E., Yousuf S., Chang S.S., Wu K.C., Chen Y.Y. Means restriction for suicide prevention. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2393–2399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60521-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niederkrotenthaler T., Fu K.W., Yip P.S., Fong D.Y., Stack S., Cheng Q. Changes in suicide rates following media reports on celebrity suicide: a meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2012;66(11):1037–1042. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sisask M., Värnik A. Media roles in suicide prevention: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(1):123–138. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9010123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch B.J. The psychological impact on police officers of being first responders to completed suicides. J Police Criminal Psychol. 2010;25(2):90–98. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.