Abstract

Background: Thyroid immune-related adverse events (IRAEs) have been reported more frequently with programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) inhibitors than cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitors, but there is limited data describing endocrinopathies from programmed cell death protein–ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors. This study characterizes thyroid IRAEs in cancer patients treated with PD-L1 inhibitors and examines the impact on overall survival.

Methods: This is a retrospective cohort study of cancer patients treated with atezolizumab and avelumab at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, from June 1, 2016 to January 30, 2018, and followed for a median of 10.1 months. Thyroid IRAEs were characterized as new onset hypothyroidism, thyrotoxicosis, and worsening of pre-existing hypothyroidism.

Results: Of 91 patients treated with a PD-L1 inhibitor, 19 (21%) developed new onset thyroid dysfunction, of whom 14 presented with hypothyroidism and 5 with thyrotoxicosis (3 progressed to hypothyroidism and 2 returned to euthyroidism), and 4 (4%) had worsening of pre-existing hypothyroidism. Thyroid IRAEs occurred after a median of two doses (6 weeks), 48% required thyroid hormone replacement, and none required steroids or discontinuation of immunotherapy. Two out of four patients with thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody >9 IU/mL at baseline developed thyroid IRAEs. Median TPO antibody titer was not different between those with and without thyroid IRAEs but was higher in those with overt than those with subclinical hypothyroidism (5 vs. 0.3 IU/mL, p = 0.003) and those prescribed thyroid hormone replacement as compared with observation (5.5 vs. 0.3, p = 0.008). Diffusely increased thyroid 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) uptake on positron emission tomography (PET) scan occurred in 71% with thyroid IRAE as compared with 6% without thyroid IRAEs (p = 0.001). Patients who developed thyroid IRAEs had longer overall survival (p = 0.027) and lower mortality (hazard ratio 0.49 [95% CI 0.25–0.99], p = 0.034) after adjusting for potential confounders.

Conclusions: PD-L1 inhibitors lead to immune-mediated thyroiditis, the most frequent endocrine IRAE. In most cases, management is supportive without requiring steroids or discontinuation of immunotherapy. Diffusely increased thyroid 18FDG uptake on PET scan may predict the occurrence of thyroiditis, whereas TPO antibodies may help identify its severity. Thyroiditis may be a biomarker for antitumor immune response, highlighting the need to further characterize its underlying mechanism.

Keywords: thyroid immune-related adverse events, immune-mediated thyroiditis, immune checkpoint inhibitor, survival, thyroid dysfunction, hypothyroidism

Introduction

Tumors can evade immune-mediated cell death (1) with the help of immune checkpoints cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and programmed cell death protein–ligands 1 and 2 (PD-L1 and PD-L2). CTLA-4 is expressed on T cells where its role is to downregulate T cell proliferation upon B7 engagement early in immune response, primarily in lymph nodes. PD-1 is expressed on activated T cells, including T regulatory cells, B cells, and myeloid cells. Its major role is to limit the activity of T cells in peripheral tissues at the time of an inflammatory response and to limit autoimmunity. In the context of cancer, it binds to its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 expressed on tumor cells that causes inhibition of T cell receptor-mediated positive signaling, leading to reduced proliferation, reduced cytokine secretion, and reduced survival of effector T cells. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are humanized monoclonal antibodies designed to block these checkpoints, thus resulting in a derepression of cytotoxic T cell function (2,3), in turn leading to enhanced antitumor immune response. The first ICI approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011 was the CTLA-4 inhibitor, ipilimumab, for use in melanoma (4). Since then, six ICIs have been approved by the FDA for clinical practice across multiple tumor types. These include PD-1 inhibitors pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and cemiplimab, and the most recent class of ICIs, which are PD-L1 inhibitors atezolizumab, avelumab, and durvalumab based on clinical trials demonstrating efficacy in various malignancies (5–8).

ICIs have now emerged as a novel cause of endocrinopathies affecting the pituitary, thyroid, and pancreas, and rarely the adrenals and parathyroid glands (9,10). Hypophysitis is the most frequent endocrinopathy reported with CTLA-4 inhibitor ipilimumab (11) but less frequently with PD-1 inhibitors (12,13). In contrast, thyroid dysfunction has been reported more commonly with PD-1 inhibitors, at a rate of 7–21% (10,12–17) as compared with 0–6% with the CTLA-4 inhibitor ipilimumab (10,12,16). The meta-analysis of clinical trials by Barroso-Sousa et al. (18) is in line with the higher frequency reported with PD-1 inhibitors pembrolizumab and nivolumab (6.5–8% for hypothyroidism and 2.5–3.8% for hyperthyroidism) as compared with ipilimumab (3.8% for hypothyroidism). Combination therapy with ipilimumab and a PD-1 inhibitor has demonstrated the highest rates of thyroid dysfunction (13.2% for hypothyroidism and 8% for hyperthyroidism) (18). Data from clinical trials are not optimal to characterize endocrinopathies because important information such as the time of onset, biochemical parameters, clinical course, and possible reversibility of such events are not systematically recorded. Also, trials often report hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism as separate entities, whereas most of these cases represent immune-mediated thyroiditis.

The clinical trial for atezolizumab reported thyroid dysfunction in 10% of patients (8). However, due to the recent development of PD-L1 inhibitors, there were none or very few patients on these agents in comprehensive observational cohort studies (12–14,17,19,20), but a case of other endocrinopathies with use of PD-L1 inhibitors (21) has been reported. To our knowledge, there have not been any comprehensive studies on the occurrence or natural history of endocrinopathies with use of PD-L1 inhibitors, particularly thyroiditis. There remain conflicting data regarding the role of thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies in thyroid immune-related adverse events (IRAEs) (13,15,19). Overall survival has been shown to be better in patients with certain endocrine IRAEs, for example ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis, as reported by Faje et al. (11) and pembrolizumab-induced thyroiditis as recently reported by Osorio et al. (15). However their results did not account for other competing factors that might affect survival in these patients, such as age, sex, and type of cancer. In this study, which represents the only study to comprehensively evaluate for occurrence of thyroid dysfunction in a cohort of patients treated with PD-L1 inhibitors, we address these knowledge gaps with an aim to characterize the frequency and course of thyroid IRAEs from PD-L1 inhibitors, to identify risk factors of thyroid IRAEs from PD-L1 inhibitors, and to investigate a possible impact on overall survival.

Materials and Methods

Study population

We performed an institutional review board-approved retrospective cohort study of adult cancer patients treated with a PD-L1 inhibitor (atezolizumab and avelumab) at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, for a period of 18 months from June 1, 2016 (first PD-L1 inhibitor used at our institution) through January 30, 2018. Durvalumab was not used at our institution during the study duration. When clinically indicated, a specific PD-L1 inhibitor was administered with intravenous infusions of 1200 mg every 3 weeks.

Subject identification and case definition

Thyroid IRAE was defined when a patient had two or more abnormal thyroid function tests (TFTs) after starting a PD-L1 inhibitor, and in the absence of other causes. Thyroid dysfunction presentation was characterized as:

-

(1)

New onset primary hypothyroidism, either overt that was defined by thyrotropin (TSH) ≥4.3 mIU/L and free thyroxine (T4) ≤0.8 ng/dL or subclinical that was defined by TSH ≥4.3 mIU/L and free T4 0.9–1.7 ng/dL.

-

(2)

Thyrotoxicosis, either overt that was defined by TSH ≤0.2 mIU/L and free T4 ≥ 1.8 ng/dL or subclinical that was defined by TSH ≤0.2 mIU/L and free T4 0.9–1.7 ng/dL.

-

(3)

Worsened/recurrent primary hypothyroidism as identified in patients with a history of hypothyroidism and on stable thyroid hormone replacement who, after initiation of the PD-L1 inhibitor, developed an acute rise in TSH requiring an increase in their levothyroxine dose by >50%.

All laboratory testing was performed at the Mayo Medical Laboratory, Rochester, Minnesota. Our laboratory's reference rages are 0.3–4.2 mIU/L for TSH and 0.9–1.7 ng/dL for free T4 for adults. Results of TPO antibodies (reference range <9.0 IU/mL), TSH receptor antibodies (TRAbs) (reference range ≤1.75 IU/L), thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) (reference range ≤1.3 TSI index), and thyroglobulin (TG) antibodies (reference range <4.0 IU/mL) when tested were also collected. A TPO antibody titer >9 IU/mL was defined as elevated TPO antibodies. When available, baseline and post-therapy 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET) scan images were reviewed.

Outcomes

The main outcomes were frequency and natural history of thyroid IRAEs after PD-L1 inhibitor use, association of thyroid IRAEs with TPO antibody and diffuse thyroid 18FDG uptake on PET scan, and difference in overall survival between those with and without thyroid IRAEs.

Statistics

Categorical variables are described as number and percentage, and continuous variables as median and interquartile range (IQR). Nonparametric statistical tests were utilized due to the non-normal distribution and small sample size. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to describe overall survival utilizing Log rank p value, and Cox proportional hazards model was used to adjust for potential confounding variables. Statistical significance was determined by a p value <0.05. Statistical testing was performed on software JMP 14.1.0 copyright 2018 SAS Institute, Inc.

Results

Study population

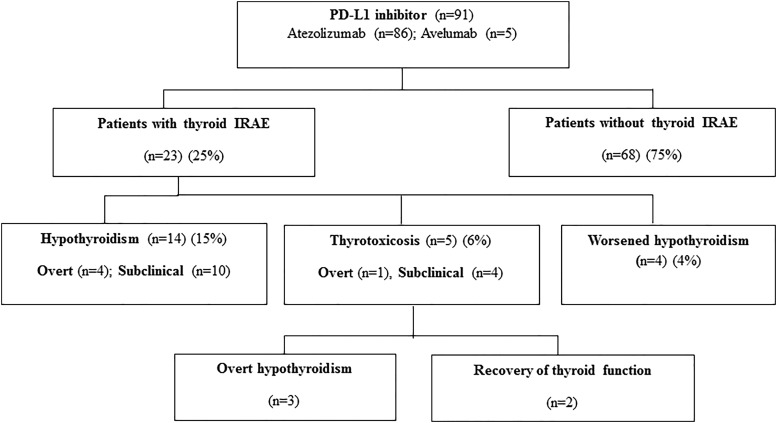

During the study period, a total of 91 patients were treated with a PD-L1 inhibitor, of which 86 patients were treated with atezolizumab with 1 receiving nivolumab previously, and 5 received avelumab (Fig. 1). The median age at start of therapy was 67.9 years, 47% were male, and lung cancer was the primary malignancy in 65% of patients. The baseline characteristics of the 23 cases with thyroid IRAEs as compared with the 68 cases without thyroid IRAEs are summarized in Table 1. One patient in the group without thyroid IRAEs developed autoimmune type-1–like diabetes mellitus.

FIG. 1.

Overview of investigated cohort of PD-L1 inhibitor-treated cancer patients to identify the occurrence of thyroid IRAE. IRAE, immune-related adverse event; PD-L1, programmed cell death protein–ligand 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics Before Initiation of Programmed Cell Death Protein–Ligand 1 Inhibitor in Patients, Comparing Those Who Developed Thyroid Immune-Related Adverse Events and Those Who Did Not

| Baseline characteristics n (%) or median (IQR) | Thyroid IRAEs (n = 23) | No thyroid IRAE (n = 68) | All patients (n = 91) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) at PD-L1 inhibitor initiation | 69.6 (65.8–75.4) | 65.9 (60.3–73.3) | 67.9 (61.4–73.9) | 0.150 |

| Males | 9 (39.1) | 38 (55.9) | 47 (51.6) | 0.165 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 22 (95.7) | 66 (97.1) | 88 (96.7) | 0.162 |

| African American | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 2 (2.9) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Hashimoto's hypothyroidism | 5 (21.7) | 1 (1.5) | 6 (6.5) | NA |

| Malignancy | ||||

| Lung | 16 (69.7) | 49 (72.1) | 65 (71.4) | 0.819 |

| Uroepithelial | 5 (21.7) | 14 (20.6) | 19 (20.9) | 0.907 |

| Merkel cell | 1 (4.3) | 4 (5.9) | 5 (5.5) | NA |

| Prostate | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | NA |

| Penis | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.1) | NA |

| PD-L1 inhibitor | 0.780 | |||

| Atezolizumab | 21 (91.3) | 64 (94.1) | 85 (93.4) | |

| Atezolizumab preceded by Nivolumab | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Avelumab | 1 (4.3) | 4 (5.9) | 5 (5.5) | |

| Elevated TPO antibody (>9 IU/mL) | 2/5 (40) | 2/8 (25) | 4/13 (30.7) | 0.569 |

| Months from PD-L1 inhibitor initiation to death or last follow-up | 15.1 (4.4–20.9) | 9.3 (4.3–16.9) | 10.1 (4.2–18.2) | 0.285 |

IQR, interquartile range; IRAE, immune-related adverse event; NA, not applicable; PD-L1, programmed cell death protein–ligand 1; TPO, thyroid peroxidase.

Frequency and presentation of thyroid IRAEs

Out of 91 cancer patients treated with a PD-L1 inhibitor, 23 patients (25%) developed thyroid IRAEs during a median follow-up of 10.1 months: of whom 19 patients (21%) developed new onset thyroid dysfunction, 14 presenting with hypothyroidism (4 overt and 10 subclinical), and 5 with thyrotoxicosis (1 overt and 4 subclinical). There were four patients with pre-existing Hashimoto's hypothyroidism, and all had worsening of their hypothyroidism as defined by a >50% increase in thyroid hormone replacement dosage after starting PD-L1 inhibitor (Fig. 1).

Natural history of thyroid IRAEs

All patients had normal TFTs drawn at baseline before starting the PD-L1 inhibitor; the four patients with pre-existing primary hypothyroidism were biochemically euthyroid on a stable dose of thyroid hormone replacement. The first abnormality in TFTs occurred after median of 2 (IQR 1–3) doses, corresponding with 6 (IQR 3–8) weeks after initiation of PD-L1 inhibitor. All patients experienced painless thyroiditis, with none demonstrating neck pain, thyroid tenderness, or thyromegaly at presentation. These cases were followed for a median of 6.2 (IQR 3.6–10.8) months. The PD-L1 inhibitor was not discontinued due to occurrence of thyroid IRAEs. Management included observation in 52% and thyroid hormone replacement with levothyroxine in the rest. The 5 patients who presented with thyrotoxicosis were asymptomatic, 3 of them progressed to overt hypothyroidism after a median of 3 (IQR 2–5) weeks, and 2 had spontaneous resolution of thyroid dysfunction (Fig. 1). Spontaneous progression to an euthyroid state also occurred in two patients who presented with subclinical hypothyroidism. The individual patient course is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of 23 Cases of Thyroid Immune-Related Adverse Event in the Setting of Programmed Cell Death Protein–Ligand 1 Inhibitor Therapy

| Thyroid IRAE | Age/sex | Malignancy/PD-L1 inhibitor | Time to onset in week/doses | TSH (mIU/L) | Free T4 (ng/dL) | TPO Ab titer (IU/mL) | Diffusely increased thyroid uptake on 18FDG-PET |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New hypothyroidism, overt | 67/F | Lung/atezolizumab | 8/2 | 79.8 | 0.005 | 544 | + |

| New hypothyroidism, subclinical | 69/F | Lung/atezolizumab | 6/2 | 8.9 | 1.1 | — | |

| New hypothyroidism, overt | 61/M | Lung/atezolizumab | 3/1 | 18.9 | 0.8 | — | |

| New hypothyroidism, subclinical | 62/M | Uroepithelial/atezolizumab | 18/3 | 6.2 | 1.2 | — | |

| New hypothyroidism, subclinical | 71/F | Lung/atezolizumab | 13/3 | 4.5 | — | ||

| New hypothyroidism, overt | 72/M | Lung/atezolizumab | 3/1 | 7.4 | 0.8 | ||

| New hypothyroidism, subclinical | 85/F | Uroepithelial/atezolizumab | 4/2 | 4.8 | |||

| New hypothyroidism, subclinical | 75/F | Lung/atezolizumab | 3/1 | 6.5 | − | ||

| New hypothyroidism, subclinical | 67/F | Lung/atezolizumab | 6/2 | 4.9 | — | ||

| New hypothyroidism, subclinical | 55/M | Lung/atezolizumab | 6/2 | 4.4 | 1.1 | — | |

| New hypothyroidism, subclinical | 65/M | Lung/atezolizumab | 6/2 | 5.1 | 1.3 | — | + |

| New hypothyroidism, subclinical | 68/M | Lung/atezolizumab | 3/2 | 4.4 | 1.5 | — | |

| New hypothyroidism, overt | 60/M | Lung/atezolizumab | 8/3 | 7.2 | 0.8 | — | |

| New hypothyroidism, subclinical | 69/F | Lung/atezolizumab | 19/6 | 4.8 | 1.4 | — | |

| Worsened hypothyroidism | 70/M | Prostate/atezolizumab | 6/2 | 5.5 | 1.5 | 76 → 126 | + |

| Worsened hypothyroidism | 66/F | Uroepithelial/atezolizumab | 3/1 | 12.1 | 1.5 | — | + |

| Worsened hypothyroidism | 61/F | Lung/atezolizumab | 6/1 | 9.5 | 1.4 | 35 → 36 | |

| Worsened hypothyroidism | 76/F | Uroepithelial/atezolizumab | 2/1 | 87.3 | 0.5 | — | |

| Subclinical thyrotoxicosis progressing to overt hypothyroidism | 79/F | Lung/atezolizumab | 9/2 | 0.1 → 22.8 | 1.3 → 0.5 | — | |

| Overt thyrotoxicosis progressing to overt hypothyroidism | 77/F | Lung/atezolizumab | 5/2 | 0.02 → 24 | 2 → 0.3 | 316 | |

| Subclinical thyrotoxicosis with spontaneous resolution | 74/M | Uroepithelial/atezolizumab | 8/3 | 0.1 | 1.3 | − | |

| Subclinical thyrotoxicosis with spontaneous resolution | 71/F | Lung/atezolizumab | 6/2 | 0.2 | 1.6 | ||

| Subclinical thyrotoxicosis progressing to overt hypothyroidism | 75/F | Merkel cell/avelumab | 9/3 | 0.2 → 5.1 | 1.6 → 0.8 | — | + |

18FDG-PET, 18-fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography; T4, thyroxine; TSH, thyrotropin.

Thyroid antibody testing and 18FDG-PET imaging

Baseline TPO antibody data were available for 13 patients, and elevated (>9 IU/mL) in 4, of whom 2 had pre-existing Hashimoto's hypothyroidism (Table 3). Of these four patients, the two with Hashimoto's hypothyroidism had worsened hypothyroidism on PD-L1 inhibitor therapy and demonstrated an increase in TPO antibody titers (Table 2). TPO antibodies were elevated in 4 of 18 patients (22%) at the time of thyroid IRAE (median titer 220.9 IU/mL), 2 of these patients had elevated TPO antibodies at baseline and 2 were not tested before therapy. Comparisons of TPO antibody titers by subgroups of severity of thyroid IRAE are reported in Table 3. TRAbs were tested and resulted negative in 3 patients with thyrotoxicosis at presentation; TG antibodies were tested and resulted negative in 4 patients. Diffusely increased thyroid 18FDG uptake on PET scan preceded abnormal TFTs in 5 of 7 patients (71%) as compared with 1 of 17 (5.6%) (p value 0.001) in those with normal TFTs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Thyroid Peroxidase Antibody Titer and Frequency of Diffusely Increased Thyroid 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose Uptake on Positron Emission Tomography Scan Compared Between Different Subgroups

| Subgroup analysis n (%) or median (IQR) | TPO antibody titer (IU/mL) | p | Diffusely increased thyroid uptake on 18FDG-PET | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroid IRAE | 0.8 (0.3–14.2) | 0.267 | 5/7 (71.4) | 0.001 |

| No thyroid IRAE | 0.4 (0.1–2.3) | 1/17 (5.6) | ||

| Overt hypothyroidism | 5 (1.3–373) (n = 6) | 0.003 | 3/3 (100) | 0.171 |

| Subclinical hypothyroidism | 0.3 (0.1–0.4) (n = 7) | 1/2 (50) | ||

| Thyroid hormone replacement | 5.5 (0.6–125.8) (n = 11) | 0.008 | 4/4 (100) | 0.053 |

| Observation | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) (n = 7) | 1/3 (33) |

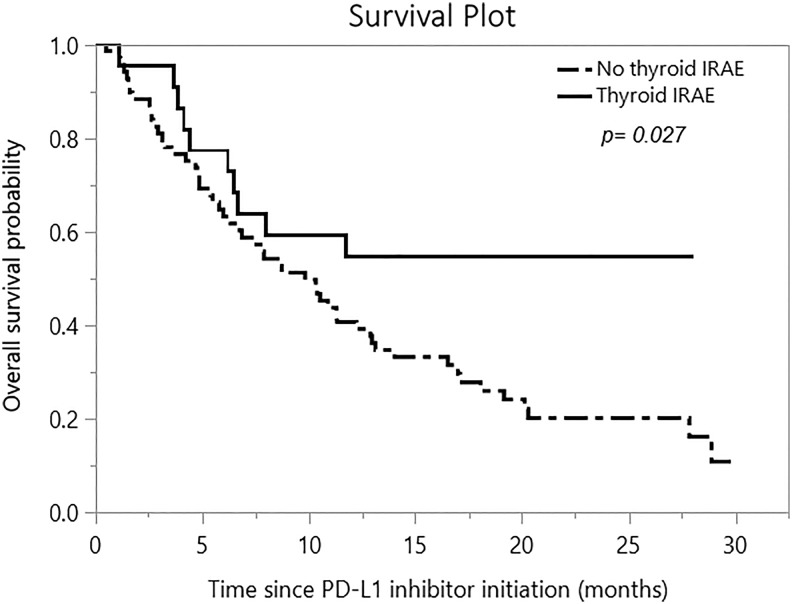

Overall survival and mortality risk

The mortality rate in patients with thyroid IRAEs was 43.5% as compared with 79.4% in those without thyroid IRAEs (p value = 0.001). In patients with thyroid IRAEs, the median overall survival cutoff was not reached as compared with those without thyroid IRAEs where median overall survival was 9.8 ([95% CI 6.3–12.9], p value = 0.027) months (Fig. 2). Survival analysis performed separately for n = 86 treated with atezolizumab also showed that the median overall survival cutoff was not reached in patients with thyroid IRAEs as compared with those without thyroid IRAEs, where the median overall survival was 9.3 ([95% CI 5.8–12.2], p value 0.027) months. There was only 1 death in n = 5 treated with avelumab; hence, analysis for survival difference could not be performed. After adjusting for age, sex, and cancer type, patients with thyroid IRAEs had a hazard ratio for mortality of 0.49 ([95% CI 0.25–0.99], p value = 0.034) as compared with patients without thyroid IRAEs (Table 4).

FIG. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing comparison of overall survival between those with and without thyroid IRAEs after therapy with a PD-L1 inhibitor.

Table 4.

Cox Proportional Hazards for Mortality in Patients Treated with Programmed Cell Death Protein–Ligand 1 Inhibitors Adjusted for Potential Confounders

| Potential variables affecting mortality | Hazard ratio for mortality (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Thyroid IRAE compared with no thyroid IRAE | 0.49 (0.25–0.99) | 0.034 |

| Male compared with female | 1.10 (0.67–1.82) | 0.696 |

| Age at PD-L1 inhibitor start (years) | 1.88 (0.32–12.01) | 0.489 |

| Malignancy | 0.175 | |

| Merkel cell compared with lung | 0.22 (0.03–1.61) | |

| Uroepithelial compared with lung | 0.97 (0.53–1.77) |

Discussion

Frequency and presentation of thyroid IRAEs

Similar to PD-1 inhibitors, PD-L1 inhibitors are associated with a high rate of thyroid IRAEs. In our study of 91 PD-L1 inhibitor-treated patients, 21% presented with new onset thyroid dysfunction (most commonly hypothyroidism, less frequently thyrotoxicosis progressing to hypothyroidism, or normalization of thyroid function) and 4% presented with worsened hypothyroidism (Fig. 1). The higher frequency of thyroid IRAEs in our study as compared with that initially reported in the atezolizumab trial (8) likely reflects the dynamic evaluation of serial TFTs during successive cycles of PD-L1 inhibitor therapy, as well as inclusion of both new onset thyroid dysfunction and worsening hypothyroidism in our study. All four patients with pre-existing hypothyroidism required an increase in the thyroid hormone replacement dose by >50% after PD-L1 inhibitor initiation, likely due to worsening destructive thyroiditis in the context of Hashimoto's thyroid disease. A similar phenomenon has been reported to occur after other ICIs (13,14,22). In other studies, for example by Iyer et al. (19), the course of patients with thyroiditis referred to their clinic was analyzed, and those with pre-existing hypothyroidism and those presenting with new onset hypothyroidism were excluded, thus presumably leading to an underestimation of the frequency of thyroid IRAEs.

Although not the primary focus of our study, we evaluated screened cases for other new onset endocrinopathies and identified one patient who developed insulin-dependent diabetes with elevated GAD65 antibodies after atezolizumab. This phenomenon has been reported with PD-1 inhibitors (23,24). Hypophysitis has commonly been reported with the CTLA-4 inhibitor ipilimumab (11,12,18) but less frequently with PD-1 inhibitors (13,18), and it has not been identified with PD-L1 inhibitors in this study; however, comprehensive testing for pituitary axes was not routinely performed in this cohort. None of the patients in our study had evidence of central hypothyroidism with a low FT4 and inappropriately normal or low TSH; however, in larger clinical settings, should this occur, consideration should be given for the presence of either nonthyroidal illness or hypophysitis.

Natural history of thyroid IRAEs

The first abnormal TFTs occurred after a median of 2 doses or 6 weeks from PD-L1 inhibitor initiation. This duration is similar to that reported with PD-1 inhibitor-induced thyroiditis (13–15,19,20), but shorter than for occurrence of CTLA-4 inhibitor-induced hypophysitis (11) and PD-1 inhibitor-induced diabetes mellitus (23,24). The 5 patients who presented with thyrotoxicosis were asymptomatic, had negative TRAbs when tested, with progression to overt hypothyroidism in 3 and spontaneous resolution in 2. This presentation is consistent with a destructive thyroiditis rather than a true hyperthyroidism etiology, such as Graves' disease. There have been case reports of a Graves' disease-like presentation with persistent hyperthyroidism and elevated TRAb/TSI after CTLA-4 inhibitors (25,26) but not with PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors. Thus, if the thyrotoxicosis phase fails to resolve in 4–6 weeks, workup for Graves' disease is appropriate. Based on this study and previously published data with PD-1 inhibitors (13,14), thyroid IRAEs are characterized by a destructive thyroiditis, manifested by diffusely increased 18FDG uptake in the thyroid followed by a transient thyrotoxic phase that progresses either to hypothyroidism or returns to normal thyroid function. Some patients present with overt hypothyroidism without an antecedent thyrotoxic phase, perhaps very mild and missed between testing. Unlike thyrotoxicosis, which may resolve, hypothyroidism does not appear reversible; however, TSH levels were not repeated after a trial off thyroid hormone replacement in our study. Overall, 12% of the entire PD-L1 inhibitor-treated cohort or 48% of those with any thyroid dysfunction presented with new or worsened or progression to overt hypothyroidism that required therapy with thyroid hormone replacement. This frequency is higher than reported in classic painless thyroiditis. Also, as compared with classic painless thyroiditis requiring 2–4 months to progress to hypothyroidism, the time for progression from thyrotoxicosis to hypothyroidism in 3 thyroid IRAE patients was shorter, suggesting an alternative or additional mechanism of thyroid destruction with PD-L1 inhibitors.

Potential factors influencing thyroid IRAE occurrence and severity

Patients with thyroid IRAEs did not differ from those without thyroid IRAEs in terms of age at therapy initiation, sex distribution, race/ethnicity, PD-L1 inhibitor type, or the primary malignancy (Table 1). This is in contrast to noncancer-related autoimmune thyroid disease, which is more common in young and middle aged women (27). There is conflicting data regarding the presence of TPO antibodies in ICI-induced thyroiditis with variable frequencies of antibody positivity reported (13,15,19). Most of the studies report TPO antibodies at the time of thyroid IRAEs, which could merely reflect exposure of thyroid antigens from the destructive thyroiditis process rather than a causal etiology. In our study, 4 of 13 patients had elevated TPO antibodies at baseline, 2 of whom had Hashimoto's hypothyroidism and demonstrated worsening of hypothyroidism after PD-L1 inhibitor therapy (Table 2).

In total, 22% of patients with thyroid IRAEs had elevated TPO antibodies (Table 2) compared with >90% reported in Hashimoto's thyroiditis (28), and 8–10% reported in the healthy population (28). This frequency is slightly lower or similar to the 23–44% reported with PD-1 inhibitor-induced thyroiditis (15,19,20), likely due to the differences in cutoff used for identifying elevated TPO antibodies and the smaller number of patients in our study in whom they were tested. There was no association of TPO antibody titer with the occurrence or time to occurrence of thyroid IRAEs. On subgroup analysis, the TPO antibody titer was higher in patients with new onset overt hypothyroidism and in those treated with thyroid hormone replacement than in those with subclinical hypothyroidism and in those managed with observation, respectively (Table 3). These findings suggest that elevated TPO antibodies may not be very helpful for identifying those at risk of thyroid IRAEs; however, elevated TPO antibodies at the time of thyroid IRAEs might influence the severity of thyroid dysfunction, thus help identifying patients who will progress to overt hypothyroidism and require thyroid hormone replacement.

Diffusely increased thyroid 18FDG uptake on PET scan preceded or coincided with abnormal TFTs in 5 of 7 (71.4%) patients with thyroid IRAEs (Table 2), similar to that with pembrolizumab-induced thyroiditis (13) and like that seen in Hashimoto's disease, serving as a biomarker for thyroiditis.

Association of thyroid IRAEs with overall survival and mortality risk

Patients with thyroid IRAEs had a lower mortality rate, and median overall survival was not reached in them as compared with those without thyroid IRAEs whose median overall survival was 9.8 months (Fig. 2), suggesting improved overall survival in those with thyroid IRAEs. The difference in survival was also present in the 86 patients treated with atezolizumab but could not be tested separately for those treated with avelumab due to the small number of events. These median overall survival durations are shorter than 40 months in patients with pembrolizumab-induced thyroiditis versus 14 months in those without pembrolizumab-induced thyroiditis shown by Osorio et al. (15), but are affected by shorter duration of follow-up in our study due to the recent onset access to PD-L1 inhibitors. Owing to early onset of thyroiditis after PD-L1 inhibitor therapy, there is minimal lead time bias in evaluating the effects on overall survival.

Overall survival has been shown to be better in ipilimumab-treated patients who develop hypophysitis (11), as well as in nivolumab-treated patients who develop all IRAEs combined (29), as well as skin IRAEs (29,30). Osorio et al. (15) reported that patients with pembrolizumab-induced thyroiditis had lower risk of mortality (hazard ratio, 0.29 [95% CI 0.09–0.94], p value = 0.04); however, the authors did not adjust for other confounding factors that might affect survival in these patients, such as age, sex, and type of cancer. In our study, after adjusting for potential confounding variables including age at PD-L1 inhibitor initiation, sex, and cancer type, patients who developed thyroid IRAEs had a 51% lower mortality risk than those who did not (Table 4). This suggests that thyroid IRAEs may be a biomarker for antitumor immune response. We hypothesize that enhanced T cell function and signaling caused by PD-L1 inhibitors likely influence both the development of IRAEs and antitumor responses. This finding adds to the currently available knowledge regarding the underlying mechanism of ICI-induced thyroiditis (13,14). It also highlights the importance of further investigating the underlying mechanism of IRAEs and their association with antitumor response in a prospective manner.

Our study has limitations including its retrospective nature and paucity of baseline TPO antibody testing, which might have limited our ability to analyze the predictive role of baseline antibody status on the occurrence of thyroid IRAEs. The sample size was not large enough to compare survival differences between severities of thyroid dysfunction. The median follow-up of 10.1 months of the entire cohort was adequate to identify the occurrence of most thyroid IRAEs, but insufficient to characterize their full course. This duration of follow-up was adequate to demonstrate a survival difference between those with and without thyroid IRAEs but precludes us from reporting an accurate overall survival probability in the entire cohort of patients treated with PD-L1 inhibitors.

In summary, PD-L1 inhibitors are associated with a 25% risk of thyroiditis, which is the most frequent endocrine IRAE with these agents, with a similar time to onset as with PD-1 inhibitors. It can present as new/worsened hypothyroidism sometimes preceded by a mild thyrotoxic phase, which might be missed in some cases. Hypothyroidism in this setting appears to be permanent in most cases. Management depends on the phase and severity of presentation of thyroiditis but does not usually require steroids or discontinuation of immunotherapy. Diffusely increased thyroid 18FDG uptake on PET scans may predict the occurrence of thyroid dysfunction, whereas the TPO antibody titer may help predict its severity and course. The association of thyroid IRAEs with longer overall survival and reduced mortality risk suggests that they may be a biomarker for antitumor immune response, highlighting the need to further characterize the underlying mechanism.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This publication was made possible by CTSA Grant No. UL1 TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. 2011. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144:646–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. 1996. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science 271:1734–1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sharma P, Wagner K, Wolchok JD, Allison JP. 2011. Novel cancer immunotherapy agents with survival benefit: recent successes and next steps. Nat Rev Cancer 11:805–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R RO bert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, Akerley W, van den Eertwegh AJ, Lutzky J, Lorigan P, Vaubel JM, Linette GP, Hogg D, Ottensmeier CH, Lebbe C, Peschel C, Quirt I, Clark JI, Wolchok JD, Weber JS, Tian J, Yellin MJ, Nichol GM, Hoos A, Urba WJ. 2010. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 363:711–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, Kowanetz M, Vansteenkiste J, Mazieres J, Park K, Smith D, Artal-Cortes A, Lewanski C, Braiteh F, Waterkamp D, He P, Zou W, Chen DS, Sandler A, Rittmeyer A. 2016. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 387:1837–1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, van der Heijden MS, Balar AV, Necchi A, Dawson N, O'Donnell PH, Balmanoukian A, Loriot Y, Srinival S, Retz MM, Grivas P, Joseph RW, Galsky MD, Fleming MT, Petrylak DP, Perez-Garcia JL, Blurris HA, Castellano D, Canil C, Bellmunt J, Bajorin D, Nickles D, Bourgon R, Frampton GM, Cui N, Mariathasan S, Abidoye O, Fine GD, Dreicer R. 2016. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 387:1909–1920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Apolo AB, Infante JR, Balmanoukian A, Patel MR, Wang D, Kelly K, Mega AE, Britten CD, Ravaud A, Mita AC, Safran H, Stinchcombe TE, Sradanov M, Gelb AB, Schlichting M, Chin K, Gulley JL. 2017. Avelumab, an anti-programmed death-ligand 1 antibody, in patients with refractory metastatic urothelial carcinoma: results from a multicenter, phase Ib study. J Clin Oncol 35:2117–2124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McDermott DF, Sosman JA, Sznol M, Massard C, Gordon MS, Hamid O, Powderly JD, Infante JR, Fasso M, Wang YV, Zou W, Hegde PS, Fine GD, Powles T. 2016. Atezolizumab, an anti–programmed death-ligand 1 antibody, in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: long-term safety, clinical activity, and immune correlates from a phase Ia study. J Clin Oncol 34:833–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chang LS, Barroso-Sousa R, Tolaney SM, Hodi FS, Kaiser UB, Min L. 2019. Endocrine toxicity of cancer immunotherapy targeting immune checkpoints. Endocr Rev 40:17–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Torino F, Corsello SM, Salvatori R. 2016. Endocrinological side-effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Opin Oncol 28:278–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Faje AT, Sullivan R, Lawrence D, Tritos NA, Fadden R, Klibanski A, Nachtigall L. 2014. Ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis: a detailed longitudinal analysis in a large cohort of patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:4078–4085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ryder M, Callahan M, Postow MA, Wolchok J, Fagin JA. 2014. Endocrine-related adverse events following ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma: a comprehensive retrospective review from a single institution. Endocr Relat Cancer 21:371–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Delivanis DA, Gustafson MP, Bornschlegl S, Merten MM, Kottschade L, Withers S, Dietz AB, Ryder M. 2017. Pembrolizumab-induced thyroiditis: comprehensive clinical review and insights into underlying involved mechanisms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102:2770–2780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yamauchi I, Sakane Y, Fukuda Y, Fujii T, Taura D, Hirata M, Hirota K, Ueda Y, Kanai Y, Yamashita Y, Kondo E, Sone M, Yasoda A, Inagaki N. 2017. Clinical features of nivolumab-induced thyroiditis: a case series study. Thyroid 27:894–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Osorio JC, Ni A, Chaft JE, Pollina R, Kasler MK, Stephens D, Rodriguez C, Cambridge L, Rizvi H, Wolchok JD, Merghoub T, Rudin CM, Fish S, Hellmann MD. 2017. Antibody-mediated thyroid dysfunction during T-cell checkpoint blockade in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 28:583–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Corsello SM, Barnabei A, Marchetti P, De Vecchis L, Salvatori R, Torino F. 2013. Endocrine side effects induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98:1361–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Filette J, Jansen Y, Schreuer M, Everaert H, Velkeniers B, Neyns B, Bravenboer B. 2016. Incidence of thyroid-related adverse events in melanoma patients treated with pembrolizumab. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101:4431–4439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barroso-Sousa R, Barry WT, Garrido-Castro AC, Hodi FS, Min L, Krop IE, Tolaney SM. 2018. Incidence of endocrine dysfunction following the use of different immune checkpoint inhibitor regimens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 4:173–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Iyer PC, Cabanillas ME, Waguespack SG, Hu MI, Thosani S, Lavis VR, Busaidy NL, Subudhi SK, Diab A, Dadu R. 2018. Immune-related thyroiditis with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Thyroid 28:1243–1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kobayashi T, Iwama S, Yasuda Y, Okada N, Tsunekawa T, Onoue T, Takagi H, Hagiwara D, Ito Y, Morishita Y, Goto M, Suga H, Banno R, Yokota K, Hase T, Morise M, Hashimoto N, Ando M, Kiyoi H, Gotoh M, Ando Y, Akiyama M, Hasegawa Y, Arima H. 2018. Patients with antithyroid antibodies are prone to develop destructive thyroiditis by nivolumab: a prospective study. J Endocr Soc 2:241–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lanzolla G, Coppelli A, Cosottini M, Del Prato S, Marcocci C, Lupi I. 2019. Immune checkpoint blockade anti–PD-L1 as a trigger for autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome. J Endocr Soc 3:496–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Narita T, Oiso N, Taketomo Y, Okahashi K, Yamauchi K, Sato M, Uchida S, Matsuda H, Kawada A. 2016. Serological aggravation of autoimmune thyroid disease in two cases receiving nivolumab. J Dermatol 43:210–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stamatouli AM, Quandt Z, Perdigoto AL, Clark PL, Kluger H, Weiss SA, Gettinger S, Sznol M, Young A, Rushakoff R, Lee J, Bluestone JA, Anderson M, Herold KC. 2018. Collateral damage: insulin-dependent diabetes induced with checkpoint inhibitors. Diabetes 67:1471–1480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kotwal A, Haddox C, Block M, Kudva YC. 2019. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: an emerging cause of insulin-dependent diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 7:e000591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gan EH, Mitchell AL, Plummer R, Pearce S, Perros P. 2017. Tremelimumab-induced Graves hyperthyroidism. Eur Thyroid J 6:167–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Azmat U, Liebner D, Joehlin-Price A, Agrawal A, Nabhan F. 2016. Treatment of ipilimumab induced Graves' disease in a patient with metastatic melanoma. Case Rep Endocrinol 2016:2087525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Antonelli A, Ferrari SM, Corrado A, Di Domenicantonio A, Fallahi P. 2015. Autoimmune thyroid disorders. Autoimmun Rev 14:174–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mariotti S, Caturegli P, Piccolo P, Barbesino G, Pinchera A. 1990. Antithyroid peroxidase autoantibodies in thyroid diseases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 71:661–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haratani K, Hayashi H, Chiba Y, Kudo K, Yonesaka K, Kato R, Kaneda H, Hasegawa Y, Tanaka K, Takeda M, Nakagawa K. 2018. Association of immune-related adverse events with nivolumab efficacy in non-small-cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 4:374–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Freeman-Keller M, Kim Y, Cronin H, Richards A, Gibney G, Weber JS. 2016. Nivolumab in resected and unresectable metastatic melanoma: characteristics of immune-related adverse events and association with outcomes. Clin Cancer Res 22:886–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]