Abstract

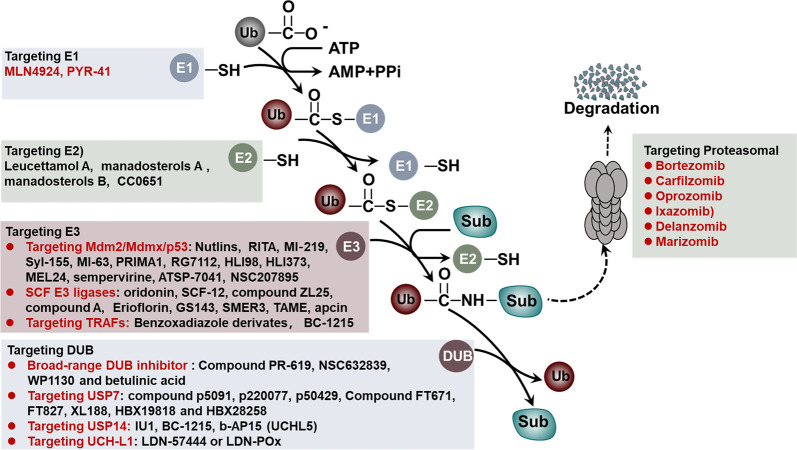

Ubiquitination, an important type of protein posttranslational modification (PTM), plays a crucial role in controlling substrate degradation and subsequently mediates the “quantity” and “quality” of various proteins, serving to ensure cell homeostasis and guarantee life activities. The regulation of ubiquitination is multifaceted and works not only at the transcriptional and posttranslational levels (phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, etc.) but also at the protein level (activators or repressors). When regulatory mechanisms are aberrant, the altered biological processes may subsequently induce serious human diseases, especially various types of cancer. In tumorigenesis, the altered biological processes involve tumor metabolism, the immunological tumor microenvironment (TME), cancer stem cell (CSC) stemness and so on. With regard to tumor metabolism, the ubiquitination of some key proteins such as RagA, mTOR, PTEN, AKT, c-Myc and P53 significantly regulates the activity of the mTORC1, AMPK and PTEN-AKT signaling pathways. In addition, ubiquitination in the TLR, RLR and STING-dependent signaling pathways also modulates the TME. Moreover, the ubiquitination of core stem cell regulator triplets (Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2) and members of the Wnt and Hippo-YAP signaling pathways participates in the maintenance of CSC stemness. Based on the altered components, including the proteasome, E3 ligases, E1, E2 and deubiquitinases (DUBs), many molecular targeted drugs have been developed to combat cancer. Among them, small molecule inhibitors targeting the proteasome, such as bortezomib, carfilzomib, oprozomib and ixazomib, have achieved tangible success. In addition, MLN7243 and MLN4924 (targeting the E1 enzyme), Leucettamol A and CC0651 (targeting the E2 enzyme), nutlin and MI‐219 (targeting the E3 enzyme), and compounds G5 and F6 (targeting DUB activity) have also shown potential in preclinical cancer treatment. In this review, we summarize the latest progress in understanding the substrates for ubiquitination and their special functions in tumor metabolism regulation, TME modulation and CSC stemness maintenance. Moreover, potential therapeutic targets for cancer are reviewed, as are the therapeutic effects of targeted drugs.

Subject terms: Cancer metabolism, Cancer therapy, Cancer microenvironment, Cancer stem cells

Introduction

Ubiquitin (Ub), a highly conserved regulatory protein containing 76 amino acids, can be covalently tagged to target proteins via a cascade of enzymatic reactions, including Ub-activating (E1), Ub-conjugating (E2) and Ub-ligating (E3) enzymes. Subsequently, mono- or polyubiquitination regulates the function of a large number of proteins in various physiological and/or pathological conditions.1,2 Polyubiquitin with different chain topologies and lengths linked to specific lysine residues on substrates is associated with different functional consequences.3 Moreover, the function of Ub ligases can also be reversed by deubiquitinases (DUBs), which are also critical for almost all cellular signaling pathways, such as the cell cycle, apoptosis, receptor downregulation and gene transcription, by removing Ub from substrate proteins.4,5

Proteins are the fundamental units in regulating cellular functions, and ubiquitination is the second most common posttranslational modification (PTM) for proteins, behind only phosphorylation.6 Thus, aberrant ubiquitination may lead to disease development and progression, especially cancer.7 Mounting evidence suggests that alterations in the activity of many E3 ligases are significantly associated with the etiology of human malignancies.8 Mutations of E3 ligases may result in the rapid degradation of tumor suppressors or, conversely, the lack of ubiquitination of oncogenic proteins.9 The pathological processes not only involve tumor metabolism regulation but also contribute to immunological tumor microenvironment (TME) modulation and cancer stem cell (CSC) stemness maintenance.10 Moreover, due to their high substrate specificity, E3 ligases and DUBs are promising potential therapeutic targets for cancer treatment. Currently, anti-cancer drugs targeting the proteasome, E3 and DUBs have been actively developed, and their therapeutic effects have been suggested by animal experiments and clinical trials.11,12 Here, we specifically summarize the mechanisms of the different components of the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS), including E1, E2, E3, the proteasome and deubiquitinating enzymes, in mediating substrate ubiquitination/deubiquitination, highlight the unique functions of ubiquitination in tumorigenesis, including tumor metabolism regulation, immunological TME modulation and CSC stemness maintenance, and review potential therapeutic targets and the therapeutic effects of targeted drugs.

The components and processes of the UPS

Ub

Ub, named for its wide distribution in various types of cells among eukaryotes, was first identified by Gideon Goldstein et al. in 1975 and further confirmed over the next several decades.13,14 In the human genome, Ub is encoded by four genes, namely, UBB, UBC, UBA52 and RPS27A. The UBA52 and RPS27A genes encode single copy Ub, which is fused to the N-terminus of the ribosomal protein subunits L40 and S27a, respectively; the UBB and UBC genes encode polyubiquitin molecules that repeat the tandem 3 and 9 times, respectively. In cells, DUBs specifically cleave these fusion proteins to produce active Ub molecules. Occasionally, the monomeric Ub unit cannot be directly utilized by E1, E2 or E3. For example, PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)-mediated phosphorylation of Ser at position 65 of Ub is necessary for the ubiquitination of mitochondrial membrane proteins. Therefore, phosphorylation at Ser65 of Ub plays an important role in mitophagy.15–18 In addition to Ser65, Ub can also be phosphorylated at Thr7, Thr12, Thr14, Ser20, Ser57, Tyr59 and Thr66, and phosphorylated monoubiquitin and polyubiquitin chains may alter their recognition by E3 ligases or Ub-binding proteins.19–22 Additionally, the Ub molecule can also be modified by other PTMs. For instance, the acetylation of Ub at K6 and K48 inhibits the formation and elongation of Ub chains.23,24 These characteristics further complicate the Ub codes, including the length of the Ub chain, the degree of mixing and the state of the branch.

Ubiquitination

In 1977, Goldknopf et al. discovered that intracellular histones could be modified by ubiquitination, and ubiquitination emerged as a new protein PTM. In 2004, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry to three scientists, Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko and Irwin Rose, for their significant contributions in the field of ubiquitination.

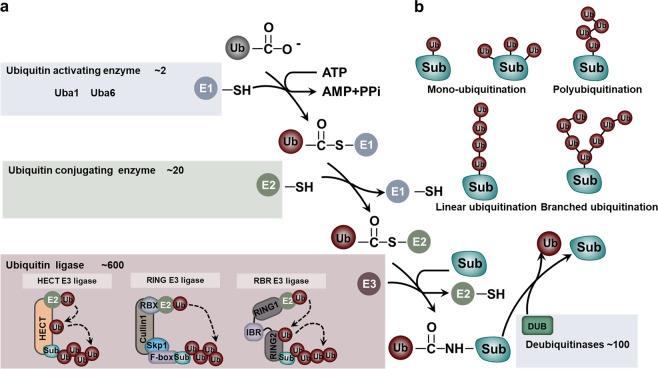

Ubiquitination is carried out in a highly specific manner that labels substrate proteins with Ub. The attachment of Ub to the substrate requires an enzymatic cascade consisting of E1, E2 and E3.13 Specifically, these processes include a three-step enzymatic reaction. Initially, Ub is activated by E1 in an adenosine triphosphate-dependent manner and then is transferred to E2. This process involves the formation of a thioester bond between the active site Cys residue of E1 and the C-terminal carboxyl group of Ub (E1~Ub). The human genome encodes only two kinds of E1, namely, UBa1 and UBa6 (Fig. 1a).25 In the second step, E1 delivers the activated Ub to E2 and assists the specific E3s in transferring the activated Ub to the substrate. Generally, humans have 35 distinct Ub-binding enzymes. Although all E2s contain a very conserved Ub-binding catalytic domain, members of this family exhibit significant specificity in their interaction with E3s (Fig. 1a).26,27 Finally, E3 ligases catalyze the transfer of Ub from E2~Ub to a specific substrate protein. When this process is completed, an isopeptide bond is formed between the lysine ε-amino group of the substrate and the C-terminal carboxyl group of Ub (Fig. 1a). The E3 ligase is the largest and most complex component of the UPS.26,28 To date, more than 600 E3 Ub ligases have been identified in the human genome (Fig. 1a). Although some E2s can directly transfer Ub to substrate proteins, in most ubiquitination processes, substrate selection and Ub linkage are achieved by E3.28,29

Fig. 1.

The components and processes of the UPS. a The components of the UPS and different classes of E3 ligases. b The ubiquitination linkage

Ubiquitination linkage

According to the structural characteristics, three main types of ubiquitination linkages have been identified: monoubiquitination, polyubiquitination and branched ubiquitination (Fig. 1b). Monoubiquitination refers to the attachment of a single Ub to a specific lysine residue of the substrate under the enzymatic cascade of E1, E2 and E3.5 Accumulating evidence has revealed that monoubiquitination is involved in the regulation of DNA damage repair. For example, the E3 ligase Rad18 regulates proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) monoubiquitination in response to DNA damage repair via the recruitment of DNA polymerases.30 In addition, the monoubiquitination of H2AX driven by TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) is a prerequisite for recruiting ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM).31 In other cases, monoubiquitination does not regulate DNA damage repair but mediates other cellular processes, such as autophagy and chromatin remodeling. For instance, monoubiquitination of membrane proteins can modulate their interaction with the autophagy adapter protein p62, thereby promoting mitochondrial autophagy and peroxisome autophagy.32 In addition, a well-defined case is the lysine-specific monoubiquitination of histone, whose modification takes part in chromatin remodeling.33 Moreover, Ras can also undergo multiple ubiquitination events at multiple sites and then regulate various signaling pathways.34

Polyubiquitination refers to the attachment of more than two Ub molecules to the same lysine residue of the substrate. Compared to monoubiquitination, there are many types of polyubiquitination, which can be linked by any lysine residues in Ub (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48 and K63) or through its N-terminal Met.35,36 Initially, the ubiquitination of the K48 type was considered to be the only polyubiquitination. It serves as a degradation signal for transferring proteins to the 26S proteasome.37 With the deepening of research, scientists have realized that K48-type polyubiquitination is only the tip of the ubiquitination iceberg.23,38,39 To date, eight types of polyubiquitin linkages have been identified (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63 and Met1) with specific functions. Unlike K48 polyubiquitination, K6 polyubiquitination takes part in the process of DNA damage repair;40,41 K11 polyubiquitination plays an important role in the cell cycle and trafficking events;42,43 K27 polyubiquitination regulates mitochondrial autophagy;44,45 K29 polyubiquitination modulates ubiquitin-fusion degradation (UFD)-mediated protein degradation;46,47 and K33 polyubiquitination participates in Toll receptor-mediated signaling pathways.48,49 K63 polyubiquitination typically takes part in protein–protein interactions, protein activity and trafficking, thereby regulating various biological processes.50–52 Moreover, Met1 is usually involved in the coupling of the C-terminus of Ub to the methionine (M1) residue on the substrate to form a peptide bond. This type of ubiquitination modification is catalyzed by a specific E3 ligase and usually controls the TNFα signaling pathway.53–55

A Ub chain with a single linkage is called a homologous chain, and a branched polyubiquitin chain contains a variety of linkages. To date, in addition to the polyubiquitination of K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63 and Met1, branched polyubiquitination also plays an important role in regulating various cellular processes.51 For example, the mixed K11 and K63 linkages participate in the Epsin1-mediated endocytosis of major histocompatibility complex I (MHCI).51,56

E3 ligases

E3 ligases are extraordinarily important in determining the specific type of ubiquitinated substrate. According to the catalytic structure, the E3 ligases are historically grouped into three types: the RING (really interesting new gene) family, the HECT (homologous to the E6-AP carboxyl terminus) family and the RBR (ring between ring fingers) family (Fig. 1a).57

RING type of E3 ligases

RING E3 is characterized by its RING or U-box folding catalytic domain that facilitates direct Ub transfer from E2 to the substrate (Fig. 1a). There are more than 600 E3 ligases in the human genome, and the RING family, encoded by ~270 human genes, is the largest family of E3 ligases. The RING finger protein generally contains the following amino acid sequence: Cys-X2-Cys-X9–39-Cys-X1–3-His-X2–3-Cys/His-X2-Cys-X4–48-Cys-X2-Cys, wherein X represents any amino acid. An E3 can bind directly to the substrate without the assistance of other proteins in catalyzing the ubiquitination of the substrate.58,59 For example, Mdm2 (murine double minute2)/Hdm2 (HDM2 being the human enzyme) and RNF152 (ring finger protein 152) belong to this class of E3s. The former promotes p53 degradation,60 and the latter mediates the polyubiquitination of RagA.61 Instead, some E3 catalytic domains and substrate recruitment modules are composed of multiple proteins, including SCF (Skp1-cullin1-F-box) and APC/C (anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome).62,63 SCF is a multisubunit complex consisting of four proteins: invariant Rbx1 (recruit the E2 enzyme), Cul1 (scaffold protein), Skp1 (bridge F-box proteins (FBPs)) and a different FBP (harbor catalytic activity). Approximately 70 FBPs have been identified in humans. Generally, the FBP takes effect in substrate recognition in the complex and selectively regulates many downstream biological processes.64 F-box/WD repeat-containing protein 7 (FBXW7) and S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (SKP2) are well-studied FBPs. As an important tumor suppressor, FBXW7 participates in the degradation of many oncogenes, such as Myc, c-Jun, cyclin E, mTOR, Notch-1 and Mcl-1. Its mutation and deletion are often associated with tumorigenesis.65 SKP2, an important oncogene, regulates a number of CDK inhibitors (such as p27) and cell cycle proteins (such as p21, p57, cyclin A, cyclin E and cyclin D1).66 Another representative example is APC/C, which is the most sophisticated RING E3 ligase. APC/C contains a cullin-related scaffolding protein, APC2, to catalyze the ubiquitination reaction and further precisely controls cell cycle progression by alternately engaging with the substrate binding module, CDC20 (recruiting cell division cycle 20) or CDC20-like protein 1 (CDH1). APC/C-CDC20 promotes the cell cycle transition from metaphase to anaphase, while APC/C-CDH1 mediates mitotic exit and early G1 entry.67,68

HECT-type of E3 ligases

The second category of E3s is the HECT Ub ligase, which can be further divided into three subfamilies: Nedd4/Nedd4-like E3s containing a WW domain, HERC E3s containing an RLD domain and other E3s without a WW or RLD domain. Compared with RING E3s, there are fewer HECT E3s, with only 28 coding genes in the human genome.59,69 The most obvious feature of HECT E3s is the HECT domain, which forms a transiently covalent bound to Ub through a conserved Cys. Unlike RING E3s, HECT E3s bind to Ub in E2-Ub and form a thioester-linked intermediate before being ligated to the lysine residue of the substrate. That is, Ub is transferred from E2 to E3, and then E2 activates HECT, thereby linking Ub to the HECT E3s via a thioester bond and transferring Ub to the substrate (Fig. 1a).70

The polyubiquitination linkage promoted by HECT E3s is determined by the C-terminal region of E3s rather than E2s.71 For instance, E6-related protein (E6AP), the first identified HECT E3, promotes K48-linkage polyubiquitination and substrate degradation; Rsp5, which belongs to the Nedd4 family of HECT, adds K63 linkage polyubiquitination to the substrate and regulates cellular endocytosis (receptors, ion channels, etc.).72,73 It is surprising that replacing the 62 amino acid sequence in the C-terminal amino acid of Rsp5 with the corresponding sequence of E6AP makes Rsp5 form a specific K48 polyubiquitin chain.74 In addition to E6AP and Nedd4, HECT E3s bind directly to the PY motifs or variant regions of the substrate through the WW domain. This interaction is critical in regulating signaling pathways, especially in the Hippo and TGFβ signaling pathways.75–78

RBR-type of E3 ligases

The RBR family is a special type of E3 ligase with an activation mechanism that is different from those of the RING and HECT types. The human genome encodes more than a dozen RBR E3s, and the family members are all multidomain proteins consisting of really interesting new gene 1 (RING1), in-between RING (IBR) and really interesting new gene 2 (RING2) (Fig. 1a).79 Among them, RING1 binds to E2 and has the characteristics of RING-type E3s. RING2, which contains a catalytic Cys nucleophile, has a similar activity as HECT E3. It forms a thioester bond intermediate with Ub and transfers Ub to the substrate (Fig. 1a).80–82 The most striking E3 of the RBR family is the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC) complex, consisting of HOIP, HOIL-1L and Sharpin. It is specifically responsible for regulating the linear ubiquitination of substrates, which plays a very important role in various biological processes, such as innate immunity and inflammation.55,83–85

All RBR E3s have a special regulation of self-inhibition due to their special structure. Mechanically, in the RBR E3 ligase, the domain outside the RING1, IBR and RING2 domains separates the RING2 domain from the RING1–IBR domain and structurally masks the active site Cys. The spatial distance between the active site of RING2 and E2 inhibits the thiol-transfer reaction and decreases the activity of RBR.80,86,87 Thus, the E3 ligase of the RBR family needs to undergo a conformational change to expose the Cys of RING2 and activate the E3 ligase.86

The activity of the RBR E3 family needs to be regulated in an orderly manner, and aberrant activity may lead to a number of diseases, including cancer and Parkinson’s disease (PD). For example, although its mutation is a major cause of familial PD,88,89 Parkin can function as a tumor suppressor to downregulate some substrates, such as cyclin D and cyclin E, and subsequently control cell cycle progression.90 Additionally, Parkin can promote the degradation of TRAF2 and TRAF6, thereby inhibiting the nuclear factor-kappa-B (NF-κB) signaling pathway and inducing tumor apoptosis.91

Nonclassical ubiquitination

Although the UPS is exclusive to eukaryotes, a recent report revealed that the SidE (siderophore E) effector family could perform atypical ubiquitination on a variety of host proteins.92 It is derived from Legionella pneumophila and works as an E3 ligase independent of E1 and E2 enzymes. The diverse strategies adopted by SidE are divided into two steps. First, the mART domain of SidE catalyzes the attachment of ADP-ribose to Arg42 of Ub and forms ADP-ribosylated Ub (ADPr-Ub). Second, the PDE domain of SidE further cleaves the phosphodiester bond in ADPr-Ub to form phospho-ribosylated Ub (Pr-Ub), which is covalently attached to the Ser of the substrate through the PDE domain of SidE. Further mechanistic studies successfully revealed a high-resolution crystal structure of the pre-reaction (SidE protein alone), the first step reaction complex (mART-Ub-NAD) and the second step reaction complex (PDE-Ub-ADP ribose). Combined with a large number of biochemical experiments and mutant analysis, the interaction between the novel E3 ligase SidE with Ub and ligand is completely presented.93,94 These exciting findings not only open a new chapter in the ubiquitination field but also provide a theoretical basis for developing targeted drugs.

Ub-like proteins

In addition to Ub, the Ub superfamily also contains Ub-like (UBL) proteins, which includes NEDD8, SUMO, FAT10, ISG15, ATG8, ATG1, HUB1 and FUB1. These UBL proteins not only have sequence homology and structural similarity to Ub but also use a similar enzymatic cascade to modify their substrate proteins.95,96 Due to space limitations, we will mainly discuss neddylation and SUMOylation below in this review.

NEDD8

In the UBL superfamily, NEDD8 has the highest homology with Ub and is indispensable in various biological processes. The specific attachment of NEDD8 to the substrate protein is called neddylation, which is a dynamic and reversible process. To date, there are many kinds of NEDD8-specific E3 ligases that determine the specificity of substrates, along with one E1 (NEDD8 activating enzyme, NAE) and two NEDD8-specific E2 ligases. The NEDD8 modification can be reversed by the COP9 signalosome (CSN), which deconjugates NEDD8 from the cullin protein.96–98

Unlike ubiquitination, neddylation does not degrade the substrate. However, as a PTM, neddylation also regulates the activation of substrates and subsequently controls a variety of cellular biological functions, such as cell cycle regulation and signal transduction. For example, neddylation mediates the biological function of the cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase (CRL) family and regulates the activity of the E3 complex by cullins, the key subunit of CRLs. Blocking the neddylation of cullins leads to substrate accumulation.99,100

Small ubiquitin-related modifier

Small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO), a widely expressed UBL protein in eukaryotes, is named for its similar structure and enzymatic cascade with Ub.101 SUMOylation is the process in which SUMO links to a substrate by forming an isopeptide bond between its terminal glycine and the lysine of the substrate.96,102 Currently, more than 500 substrates have been reported to undergo SUMOylation and take part in regulating the localization, stability and activity of many proteins.103,104 For instance, the SUMOylation of RPA1 (RPA subunit) regulates the affinity between RPA and RAD51 and promotes homologous recombination (HR)-mediated DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair.105 RNF4, a SUMO-targeted E3 ligase, has been identified as the link between ubiquitination and SUMOylation. SUMOylation of PML recruits RNF4 and triggers its degradation in a ubiquitination-proteasome-dependent way.106–108 Therefore, SUMOylation takes part in a variety of cellular physiological activities, such as gene stability maintenance and transcriptional regulation, and aberrant SUMOylation is closely related to the development and progression of certain diseases, including cancer.

Deubiquitinating enzymes

Ubiquitination, a dynamic and reversible process, is regulated by DUBs and E3 ligases.109 DUBs belong to the family of Cys proteases and cleave the isopeptide bond (the attachment of Ub to lysine) or the peptide bond (the connection of Ub to the N-terminal methionine of the protein) with high specificity.70,109

Currently, the human genome encodes no less than 100 DUBs (Fig. 1a). According to their sequence and structural similarities, they can be divided into six families: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), otubain proteases (OTUs), Machado-Joseph disease protein domain proteases (MJDs), JAMM/MPN domain-associated metallopeptidases (JAMMs) and monocyte chemotactic protein-induced proteins (MCPIPs). Among them, all DUBs are Cys proteases except the JAMM family of metalloproteinases. These enzymes are capable of directly binding to different types, topologies or lengths of Ub chains and removing Ub chains from the substrate.110 Engineered deubiquitination synthesis reveals that the OTU specifically removes the K29 linkage Ub chain from the substrate,111 and the JAMM, such as AMSH, AMSH-LP, BRCC36 and POH1, are often specific for the Ub chain for K63 linkage ubiquitination.112,113 CYLD is more likely to act on linear ubiquitination and the K63 linkage Ub chain.114 Similarly, OTU domain-containing ubiquitin aldehyde-binding protein 1 (OTUB1) specifically acts on K48-linked ubiquitination,115,116 with Cezanne specifically removing the K11 linkage Ub chain,117,118 and TRABID specifically recognizing the K29-linked or K33-linked Ub chain.119 These specific Ub-type deubiquitinating enzymes cannot remove the last molecule of Ub-modified on the substrate, which may generate a monoubiquitinated substrate protein.

To date, many DUBs have been found to be associated with p53 regulation in tumorigenesis. For example, USP7 regulates the stability of both p53 and Mdm2 and maintains p53 ubiquitination levels;120 USP2 mediates the stability of Mdm2;121 USP10 modulates p53 localization and stability;122 OTUB1 abrogates p53 ubiquitination and activates p53.123 Interestingly, USP10 can stabilize both mutated and wild-type p53, with a dual role in tumorigenesis. USP11 participates in the regulation of DNA DSB repair. USP11 is often overexpressed in cancer and induces resistance to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) inhibitors.124

Ubiquitination in tumor metabolism regulation

Ubiquitination in the mTORC1 signaling pathway

As an important nutrient and key environmental stimulus, amino acids play a critical role in the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling pathway. The mechanism of the amino acid-induced mTORC1 signaling pathway is still under continuous research. One well-demonstrated model has proposed that the activation of mTORC1 is induced by amino acid sensing cascades, including Rag GTPase, Ragulator and vacuolar H+-ATPase (v-ATPase), at lysosomes. During this process, amino acids can promote RagA/B binding to GTP, which is essential for mTORC1 lysosome localization.125–127 Moreover, many regulators of RagA/B have been identified, and these include the SLC38A9 functioning as the guanosine exchange factor (GEF) of RagA/B,128 Sestrin2 identified as the guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (GDI) of RagA/B,129 and the GATOR1 complex acting as a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) to RagA/B.130 However, the role of ubiquitination in the RagA-mTORC1 pathway in response to amino acids is still poorly understood.

Ubiquitination of RagA

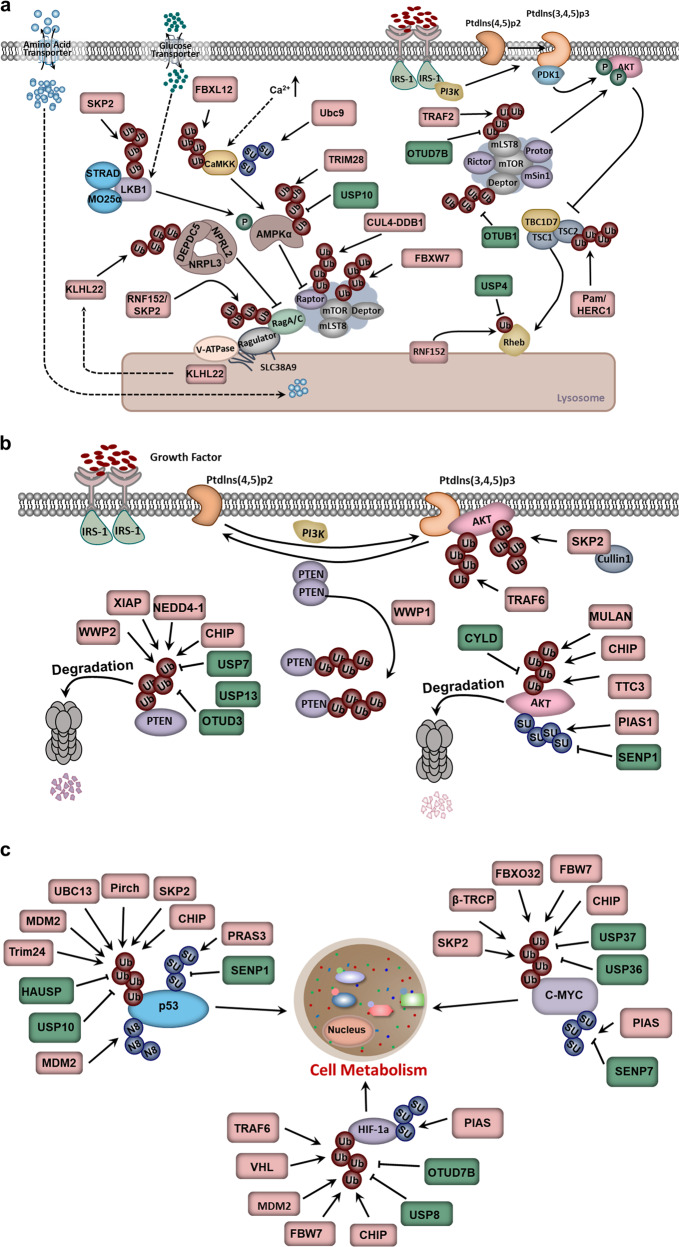

Recently, RagA and mTORC1 were found to be inactivated upon acute amino acid withdrawal. In this study, RagA was modified by polyubiquitination in an amino acid-sensitive manner. By screening a series of E3 ligases, RNF152, a lysosomal E3 ligase, was identified to mediate K63-linked polyubiquitination of RagA. In addition, ubiquitination of RagA recruited GATOR1, led to the inactivation of RagA and caused mTORC1 release from the lysosomal surface, thereby blocking the inactivation of the mTORC1 signaling pathway.61 Moreover, SKP2, another E3 ligase, could mediate RagA polyubiquitination on lysine 15.131 Thus, the polyubiquitination of RagA plays an important role in regulating the mTORC1 signaling pathway (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Ubiquitination in tumor metabolism regulation. a Ubiquitination in the mTORC1 signaling pathway. b Ubiquitination in the PTEN-AKT signaling pathway. c Ubiquitination of key transcription factors in cell metabolism regulation

Ubiquitination of mTOR

Undoubtedly, mTOR occupies a decisive position in the amino acid-induced mTORC1 signaling pathway. As mentioned above, being located on lysosomes via RagA deubiquitination is the premise of mTORC1 activation.130,132–134 In addition to RNF152/SKP2, TRAF6, an E3 ligase, is also reported to regulate mTOR translocation to the lysosome in response to amino acid stimulation by catalyzing the K63 ubiquitination of mTOR in the form of the p62-TRAF6 heterodimer complex. Thus, TRAF6 regulates autophagy and cancer cell proliferation by activating mTORC1.135 In addition to K63 ubiquitination, other types of polyubiquitin linkages have also been identified on mTOR. K48 ubiquitination is reported to be involved in the stability of mTOR. In this process, FBXW7 directly binds to mTOR and mediates its degradation by the proteasome (Fig. 2a).136 These results highlight the dominant role of ubiquitination in the mTORC1 pathway and reveal that different types of ubiquitination linkages lead to different functions.

Ubiquitination of DEPDC5

Amino acid stimulation can abolish the interaction between Sestrin2/CASTOR1/2 and the GATOR2 complex, which is essential for the activation of Rag GTPase. GATOR2 dissociates from Sestrin2/CASTOR1/2 and activates RagA/B by inhibiting the activity of GATOR1, which consists of DEPDC5, NPRL3 and NPRL2, and displays GAP activity to RagA/B.129,130,132,137 In addition, ubiquitination is also involved in the regulation of GATOR1 activity, in which Cullin3-KLHL22 E3 ligase promotes K48 linkage polyubiquitination of DEPDC5 and mediates its degradation by proteasomes under amino acid-stimulated conditions (Fig. 2a). KLHL22 plays a conserved role in the mTORC1-mediated autophagy, cell size and regulation of the nematode lifespan through DEPDC5. Moreover, the expression of KLHL22 is significantly negatively correlated with DEPDC5 in patients with breast cancer. Therefore, pharmacological interventions targeting KLHL22 may have therapeutic potential for relevant diseases, such as breast cancer and age-related diseases.138

Ubiquitination of mLST8

mTOR predominantly exists in two multicomponent kinase complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2, which are structurally related but functionally distinct. The mTORC1 and mTORC2 signaling pathways are not independent.127 The activation of mTORC1 is inseparable from AKT activated by mTORC2, and the feedback inhibition of mTORC2 activation requires mTORC1-mediated Sin1 phosphorylation.139 mTORC2 contains six components, of which mTOR, DEPTOR and mLST8 are identical to mTORC1. Therefore, the dynamic assembly of mammalian lethality with SEC13 protein 8 (mLST8) in the two complexes is important for both complexes. Previous studies have shown that the K63 linkage polyubiquitination of mLST8, promoted by TRAF2, determines the homeostasis of mTORC1 formation and activation. Specifically, the K63 linkage polyubiquitination of mLST8 disrupts its interaction with the mTORC2 component Sin1 to favor mTORC1 formation. In addition, the deubiquitinating enzyme OTUD7B was reported to facilitate the formation of mTORC2 by removing the polyubiquitin chain on mLST8 and then promoting the interaction between mLST8 and Sin1. Collectively, the dynamic assembly and activation of mTORC1 and mTORC2 are dependent on the ubiquitination of mLST8, further demonstrating the importance of ubiquitination in the mTOR signaling pathway (Fig. 2a).140

Ubiquitination of DEPTOR

DEP domain-containing mTOR-interacting protein (DEPTOR) is an important component and negative regulator of both mTORC1 and mTORC2.141 Its stability is governed in a Ub-proteasome pattern by the E3 ligase beta-transducin repeat containing protein 1 (β-TrCP1), simultaneously proven by three different teams.142–144 In these studies, DEPTOR was recognized by β-TrCP1 via its degron sequence and subsequently ubiquitinated and degraded. Moreover, DEPTOR accumulation upon β-TrCP1 knockdown or the degron mutation could promote autophagy by inactivating mTORC1 (Fig. 2a).

The regulatory mechanisms of DEPTOR stability have also been explored. OTUB1 specifically interacts with DEPTOR via its N-terminal domain, removes the Ub chain on DEPTOR and stabilizes DEPTOR via DUB activity in an Asp88-dependent but not Cys91-dependent manner (Fig. 2a). Thus, β-TrCP1 and OTUB1 can balance cell survival and autophagy by activating mTORC1 through regulating DEPTOR ubiquitination, which also illuminates the importance of ubiquitination in the mTORC1 signaling pathway.145

Ubiquitination of TSC-Rheb

As a major regulator of Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb), the TSC complex is the central node for many growth and stress signals, ranging from growth factors, glucose, oxygen and energy to oncogenes and tumor suppressors. TSC2, a short-lived protein, is regulated by PTM in response to upstream signals.146 ERK- and AKT-mediated phosphorylation of TSC2 can result in the activation of Rheb,147,148 while ubiquitination can regulate the stability of TSC2. For example, TSC2 can bind to FBW5, a compound of the FBW5-DDB1-CUL4-ROC1 E3 ligase. The overexpression of FBW5 or CUL4A promotes TSC2 ubiquitination and degradation. Thus, FBW5 is a specific E3 ligase targeting TSC2 for its degradation and promoting TSC complex turnover (Fig. 2a).149

mTORC1 is recruited to lysosomes, where it is activated by its interaction with GTP-bound Rheb.133 The ubiquitination of Rheb regulates its activity. It has been reported that the ubiquitination of Rheb governs its nucleotide-bound status and controls the transformation between Rheb-GDP and Rheb-GTP. The lysosomal E3 ligase RNF152 can induce Rheb ubiquitination and promote its binding to the TSC complex in an epidermal growth factor (EGF)-sensitive manner. Upon growth factor stimulation, USP4 removes the Ub chain from Rheb in an AKT-dependent manner, which leads to the release of Rheb from the TSC complex, resulting in the subsequent activation of both Rheb and mTORC1. Therefore, the ubiquitination of Rheb, determined by RNF152 and USP4, also plays an important role in mTORC1 activation and consequent tumorigenesis (Fig. 2a).150

Ubiquitination in the adenylate-activated protein kinase signaling pathway

Adenylate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), the master sensor of energy in cells and organisms, is the core in regulating intracellular metabolic homeostasis, and its mutation is associated with tumorigenesis.151,152 When the cellular level of ATP decreases and AMP/ATP increases, the activation of AMPK increases. For instance, in response to a high AMP/ATP ratio in the cytosol, AMPK enhances glucose uptake and utilization by regulating key proteins in the cellular metabolic pathway, as well as fatty acid oxidation, to produce more energy.151,153 In addition to being phosphorylated, AMPK can also undergo ubiquitination. Specifically, the E3 ligase MAGE-A3/6-TRIM28 can ubiquitinate AMPK and promote its degradation. Furthermore, two homologs, MAGE-A3 and MAGE-A6, originally expressed only in the male germline, are reactivated in tumors. In mice, overexpressing MAGE-A3/A6 in cell lines promotes tumor growth and metastasis. In this process, MAGE interacts with the E3 ligase TRIM28, which controls the stability of AMPKα by mediating the K48 linkage polyubiquitination of AMPKα (Fig. 2a).154

In addition to K48 linkage polyubiquitination, the activation of AMPKα is also regulated by K63-specific polyubiquitination, which may mask its structure to block the access of liver kinase B1 (LKB1) and inhibit the activation of AMPKα. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP10 can remove the Ub chain from AMPKα and promote AMPKα activation by facilitating LKB1-mediated AMPKα phosphorylation, thereby participating in glucose and lipid metabolism in cells.155 In addition, ubiquitination also acts on LKB1. Generally, LKB1 functions as an oncoprotein and is activated by a complex with STRAD and MO25.156–158 SKP2 promotes the K63 polyubiquitination of LKB1 and plays an important role in LKB1 activation by maintaining the intact LKB1-STRAD-MO25 complex (Fig. 2a). Additionally, in a hepatocellular carcinoma model, SKP2-mediated LKB1 polyubiquitination is required for its activation and cell survival.159

In addition, ubiquitination is also involved in the regulation of the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 2 (CaMKK2)–AMPK signaling pathway. For example, the stability of CaMKK2 is controlled by the E3 ligase Fbxl12, which facilitates the degradation of CaMKK2 by promoting its ubiquitination (Fig. 2a).160 Thus, to maintain intracellular metabolic homeostasis, ubiquitination should not be ignored in the regulation of AMPK.

Ubiquitination in the PTEN-AKT signaling pathway

Unlike amino acid stimulation, growth factors are sensed by PTEN-AKT. It has been validated that both the PTEN-AKT and mTOR signaling pathways are important for the growth factor response. However, the two pathways were not unified until the identification of two key proteins: the small GTPase Rheb and its negative regulator TSC complex (Fig. 2a).148,161–163

Ubiquitination of PTEN

PTEN, a tumor suppressor and lipid phosphatase, plays an important role in tumorigenesis by inhibiting the PI3K signaling pathway. Generally, PTEN can be ubiquitinated and deubiquitinated. Nedd4-1, WW domain-containing ubiquitin E3 ligase 2 (WWP2), X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) and C-terminus of HSC70-interacting protein (CHIP) have been identified as the specific E3 ligases for PTEN, and the ubiquitination of PTEN mediated by each of them has different functions.164–167 For example, Nedd4-1, an E3 ligase of the HECT family, can promote both monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination of PTEN at K13 and K289, leading to the cytoplasmic localization and subsequent degradation of PTEN. PTEN is usually stable and not polyubiquitinated in the nucleus. The monoubiquitination of PTEN induces its translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, and further polyubiquitination functions as a proteolytic signal to degrade PTEN via the proteasome.168 Moreover, WWP2 is also found to ubiquitinate PTEN and regulate cell apoptosis by mediating PTEN degradation.165 Additionally, the E3 ligase WWP1-induced PTEN ubiquitination inhibits PTEN dimerization, membrane recruitment and function. Inhibiting the activity of WWP1 leads to PTEN reactivation and blocks MYC-driven tumorigenesis.169 Moreover, the E3 ligases XIAP and CHIP can also target PTEN for ubiquitination and degradation and further activate the AKT signaling pathway (Fig. 2b).166,167

Due to the reversibility of ubiquitination, the deubiquitination of PTEN has also attracted the attention of researchers. USP7, a highly expressed DUB in prostate cancer and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), plays a direct role in PTEN deubiquitination and regulates its localization rather than protein stability.170 In addition, USP13 and OTUD3 can interact with PTEN and remove its polyubiquitin chain. Subsequently, blocking the degradation of PTEN inhibits the activity of the AKT signaling pathway and tumor growth (Fig. 2b).171,172

Ubiquitination of AKT

As a critical upstream target of the mTORC1 signaling pathway, AKT kinase transfers growth factor signals from the extracellular environment to the intercellular space. Its activation, which depends on the localization to the plasma membrane and is associated with K63-linked ubiquitination, is essential for cell growth, proliferation and metabolism.173,174 TRAF6, SKP2, tetratricopeptide repeat domain 3 (TTC3), CHIP, Nedd4 and MULAN have been identified as E3 ligases for AKT and participate in AKT kinase activation. TRAF6 is a direct E3 ligase for AKT in response to IGF-1 stimulation, and K63 polyubiquitination by TRAF6 is necessary for AKT membrane recruitment, phosphorylation and activation. The cancer-associated AKT mutation displays an increasing trend in AKT ubiquitination.175 In addition, SKP2 is also the E3 ligase for ErbB-receptor-mediated AKT ubiquitination. In a breast cancer metastasis model, SKP2 deficiency decreases the activation of the AKT kinase.176 Moreover, K48 linkage ubiquitination was also identified to regulate the stability of AKT instead of its activation. In addition, many studies have been identified that CHIP, MULAN and TTC3, an E3 Ub ligase, can ubiquitinate AKT and mediate its degradation (Fig. 2b).177–180

Corresponding to ubiquitination, “eraser” DUBs can also regulate protein degradation, localization, activation and protein–protein interactions of AKT. The cylindromatosis (CYLD), a well-known tumor suppressor, can interact directly with AKT and deubiquitinate its K63-linked ubiquitination in response to the stimulation of growth factors, which results in K48 linkage polyubiquitination via BRCA1 or TTC3 (Fig. 2b).181 The loss of CYLD accelerates tumorigenesis and triggers cisplatin resistance in melanoma and oral squamous cell carcinoma.182,183 Thus, CYLD is considered a molecular switch for the ubiquitination of AKT and determines the localization and activation of AKT during cancer progression.

To date, it has been well documented that the AKT kinase can be modified by phosphorylation, ubiquitination, acetylation, methylation and hydroxylation.184,185 Moreover, SUMOylation can also be responsible for AKT activation (Fig. 2b). Lysine 276, located in the SUMOylation consensus motif, is essential for AKT activation, while the mutation of K276R can reduce the SUMOylation of AKT, and AKT E17K can mediate cell proliferation, migration and tumorigenesis.186

Ubiquitination of key transcription factors in cell metabolism regulation

Transcription factors also play crucial roles in regulating cellular metabolism. When cells are in a state of limited energy intake or starvation, transcription factors can activate the related genes in glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle, increase hepatic glucose production, reduce insulin secretion and provide a substrate for gluconeogenesis. Among them, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), Myc and p53 are closely related to cell metabolism.151,187,188

Ubiquitination regulates HIF-1α

HIF1, a transcription factor widely expressed under hypoxic conditions, is the key regulator of oxygen homeostasis in cells.189 It can induce the expression of many glycolytic genes, such as glucose transporter member 1, hexokinase 1 and hexokinase 2, lactate dehydrogenase A, monocarboxylate transporters 4 and PDK1, which are indispensable in glucose uptake. HIFs include three subtypes: HIF1, HIF2 and HIF3. They are composed of α and β subunits, wherein the α subtype, which is sensitive to oxygen, is easily degraded via the proteasome pathway; and in contrast, the β subunit is more stable.190,191

Due to the important role of HIF in cells, many studies have been performed to investigate the regulatory mechanism of HIF.192,193 Among them, E3 ligases and DUBs have been found to regulate the stability of HIF. Under normal conditions, HIF-1α is extremely unstable. The tumor suppressor E3 ligase von Hippel-Lindau (VHL), which is widely involved in tumor vascularization, interacts with HIF-1α in a proline hydroxylation-dependent manner and mediates its degradation, thereby inhibiting tumor growth (Fig. 2c).194

It has been found that glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3β) phosphorylates HIF-1α and promotes K48 polyubiquitination by FBW7, thereby mediating the degradation of HIF-1α and inhibiting angiogenesis, cell migration and tumor growth.195 On the other hand, the FBW7-mediated proteolytic signal can be removed by the deubiquitinating enzyme USP28.196 In addition to VHL, the tumor suppressors p53, Tap73 and PTEN also recruit the E3 ligase Mdm2 to HIF-1α, leading to the ubiquitination and degradation of HIF-1α by the proteasome.197 Unlike K48 linkage polyubiquitination, TRAF6 can mediate the K63 linkage polyubiquitination of HIF-1α and block its degradation (Fig. 2c).198 Moreover, the E3 ligase FBXO11 can reduce the mRNA level of HIF-1α but has no effect on its protein stability.199

Similarly, HIF-1α can also be deubiquitinated. For example, OTU deubiquitinase 7B (OTUD7B) can deubiquitinate HIF-1α and inhibit its degradation by the lysosome.200 By screening an siRNA library, the deubiquitinating enzyme USP8 interacts with HIF-1α, removes the Ub chain from HIF-1α, and maintains its expression and transcriptional activity under normal oxygen.201 Moreover, HIF-1α can also undergo SUMOylation. Overexpressing the SUMO molecule and SUMO ligase in lymphatic endothelial cells can induce the SUMOylation of HIF-1α and maintain the stability and transcriptional activity of HIF-1α (Fig. 2c).202

Ubiquitination regulates c-Myc

The transcription factor c-Myc can regulate cell proliferation, metabolism and metastasis by mediating a variety of cellular metabolism pathways, such as glucose metabolism, fatty acid and nucleotide biosynthesis. c-Myc is involved in glucose uptake and glycolysis, and its activation upregulates the expression of glucose transporters and hexokinases.203,204 As a very unstable protein with a very short half-life, c-Myc can be degraded in a proteasome-dependent manner, and many studies have identified the E3 ligase and DUB of c-Myc. For example, in the G1 to S phases of the cell cycle, the E3 ligase SKP2 can interact with c-Myc and mediate its degradation by ubiquitination, thereby blocking the cell cycle and inhibiting tumorigenesis.205,206 Additionally, the phosphorylation of c-Myc on Thr58 by GSK3 promotes its interaction with Fbw7 and facilitates K48 linkage polyubiquitination. The subsequent degradation inhibits cell proliferation and tumor growth. Missense mutations of Fbw7 are found in many malignancies; for example, the mutation R465C fails to degrade c-Myc in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.207 In addition to Fbw7, other E3 ligases, such as β-TrCP1, CHIP and FBXO32, can also ubiquitinate c-Myc, mediate its subsequent degradation and inhibit tumorigenesis.208–210 Moreover, the USP37 and USP36 can promote tumorigenesis by stabilizing c-Myc.211,212 By mass spectrometry, SUMO ligase protein inhibitor of activated STAT (PIAS) and Sentrin-specific protease 7 (SENP7) were also found to control the SUMOylation of c-Myc at K326 and regulate its ubiquitination and degradation (Fig. 2c).213

Ubiquitination regulates p53

p53, one of the most important tumor suppressors, works in multiple cellular processes, such as cell cycle regulation, DNA repair and apoptosis. In addition, p53 also plays an important role in cell metabolism by inhibiting glycolysis and promoting oxidative phosphorylation in response to nutrient stimulation.214,215

Under the stimulation of low carcinogenicity and genotoxicity, p53 is persistently expressed, but its protein level is often maintained at low levels. Under the stimulation of the external environment, the degradation of p53 is inhibited, resulting in the improvement of its stabilization and transcriptional activity.214 To date, more than 15 E3 ligases of p53 have been identified, and they are divided into the RING family (Mdm2, Pirh2, Trim24, Cul1/Skp2, Cul4a/DDB1/Roc, Cul5, Cul7, Synoviolin, Cop1, CARP1/2, CHIP, UBE4B) and HECT family (ARF-BP1, Msl2/WP1) ligases. Moreover, both K48- and K63-linked ubiquitination have been found on p53. The former can promote the degradation of p53 via the proteasome, while the latter is required for the translocation of p53 to the cytoplasm. More specifically, the E3 ligases Mdm2, Pirh2, Trim24, Cul1/Skp2, Cul4a/DDB1/Roc, Cul5, Synoviolin, Cop1, CARP1/2, ARF-BP1, Msl2/WP1, CHIP and UBE4B mediate K48 linkage polyubiquitination, which degrades p53 via the proteasome, while Cul7-mediated polyubiquitination regulates the localization and activity of p53 (Fig. 2c).9,216,217

As mentioned above, deubiquitination is also a key regulatory step in cell metabolism. The deubiquitination enzymes HAUSP and USP10 can remove the proteolytic signal of p53 and abolish its degradation. HAUSP, which is localized in the nucleus, can prevent the degradation of p53 by deubiquitinating even under the circumstance of highly expressed Mdm2.120,218 Unlike HAUSP, USP10 is generally located in the cytoplasm. In the case of DNA damage, the phosphorylation of USP10 at Thr42 and Ser337 mediated by ATM is essential for its translocation to the nucleus, where USP10 induces the deubiquitination of p53 and makes p53 work as a tumor suppressor (Fig. 2c).122

In addition to ubiquitination, p53 can also undergo other ubiquitination-like modifications, such as neddylation and SUMOylation. For example, Mdm2 can inhibit p53-mediated transcriptional activity via neddylation on K370, K372 and K373 of p53.219 SUMOylation of p53 can regulate the transcriptional activity under genotoxic stress (Fig. 2c).220

Ubiquitination in immunological TME modulation

The innate immune system can recognize invading pathogenic microorganisms by inducing the expression of proinflammatory and anti-infective genes. During the process of tumorigenesis, premalignant lesions, regarded as invaders, can lead to inflammation and activate local innate immune surveillance to the malignant cells in the early stages.221 Then, the inflammatory, immunological and metabolic processes of the tumor and the tumor-draining lymph nodes (TDLNs), constituting the immunological TME, are also reprogrammed.222 According to Dvorak’s 1986 comment, malignancies are regarded as “wounds that do not heal”.223,224 As an important risk factor for malignancy, chronic immune activation and inflammation persistently promote TME formation by providing inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and TGF-β and ultimately lead to angiogenesis and antitumor immunity.225,226

Ubiquitination, a ubiquitous PTM in cells, appears to be a critical mediator of the host cell defense and immunological TME modulation by regulating cell signal transduction pathways. On the one hand, as a multifunctional signal regulator, ubiquitination can precisely regulate the process of the immune response in a time and space manner.227 On the other hand, it can effectively induce antitumor immunity by mediating the degradation of key signal transduction molecules to stabilize and maintain the balance between tumor suppressors and oncoproteins.228,229 The Toll-like receptor (TLR), RIG-like receptor (RLR) and DNA recognition receptor signaling pathways are very important in the immune system; thus, we introduce the functions of ubiquitination in TLR, RLR and DNA recognition receptor signaling pathways, and related molecular regulatory mechanisms are relatively highly studied.

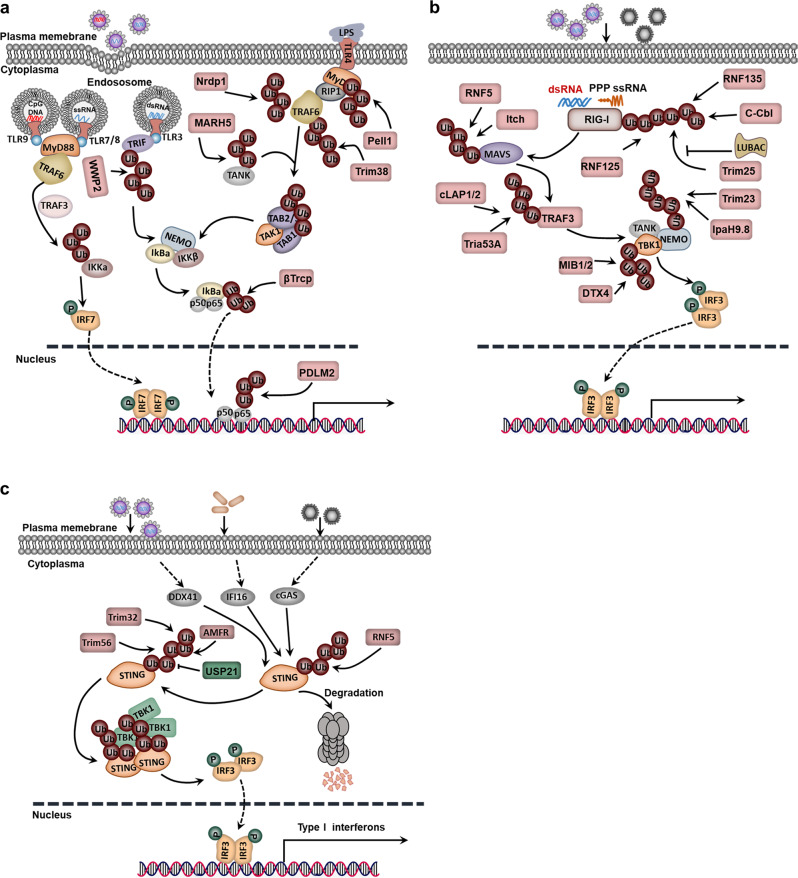

Ubiquitination in the TLR signaling pathway

As innate immune receptors, TLRs are involved in the recognition of microorganisms by the immune system. Generally, TLRs recognize a conserved component of the pathogen and then activate the signaling pathway.230 TLR signaling in immune and inflammatory cells of the TME also induces the production of proinflammatory cytokines and leads to the polarization of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), activation of protumorigenic functions of immature myeloid cells and transformation from fibroblasts into cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs).231 TLR, a family of receptors, has 13 members. Among them, TLR4/7/8/9 activates the MyD88-dependent signaling pathway and subsequently elevates the activity of the downstream TRAF6. In the TLR4 signaling pathway, the K63 polyubiquitin chain catalyzed by TRAF6 recruits the TGF-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) complex and IκB kinase (IKK) complex and then increases the expression of inflammatory factors downstream of NF-κB. The K63 polyubiquitin chain also recruits TRAF3, IKKα and IRF7 and ultimately increases the expression of type I interferon in the TLR7/8/9 signaling pathway.232,233 In addition, the K63 polyubiquitination of receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), catalyzed by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Peli1, plays an important role in the TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF)-dependent TLR signaling pathway, which significantly enhances the activation of NF-κB by transferring NF-κB or IRF3 to the nucleus to regulate the transcription of target genes.234 MARCH5, an E3 ligase located on mitochondria, catalyzes K63-linked polyubiquitination of TRAF family member-associated NF-κB activator (TANK) and then enhances the activation of the TLR signaling pathway (Fig. 3a).235

Fig. 3.

Ubiquitination in immunological tumor microenvironment (TME) modulation. a Ubiquitination in the TLR signaling pathway. b Ubiquitination in the RLR signaling pathway. c Ubiquitination in the STING-dependent signaling pathway

NF-κB signaling pathway inhibitors are degraded by the ubiquitination-proteasome pathway. For example, the transcription factor NF-κB is retained in the cytoplasm due to its interaction with the inhibitor IκBα in the remaining cells, while lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation induces the phosphorylation of IκBα by IKKβ and degradation by the E3 ligase β-TrCP1.236 In some cases, polyubiquitination at K48 and K63 can also synergistically promote the activation of signaling pathways. For example, MyD88 is crucial for gathering TRAF6, TRAF3 and cIAP1/2 in the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway. More specifically, TRAF6, recruited by MyD88, activates cIAP by catalyzing the K63-linked polyubiquitination of cIAP, while activated cIAP induces the K48 polyubiquitination of TRAF3, leading to the degradation of TRAF3 by the proteasome.237 TRAF6 can also result in the ubiquitination of ECSIT and increase mitochondrial and cellular TLR-induced ROS generation.238 Recently, USP4 has been identified as a new DUB of TRAF6 and can negatively regulate the NF-κB signaling pathway.239

The ubiquitination process is also a safeguard to prevent tumorigenesis by inhibiting the overactivation of NF-κB at multiple sites. A negative regulator A20 can cooperate with RNF11, ITCH and TAX1BP1 to remove the K63-linked polyubiquitin chain catalyzed by TRAF6 from cIAP.240 Additionally, Nrdp1, Trim38, WWP2 and PDLIM2 trigger the K48-linked polyubiquitination of MyD88, TRAF6, TRIF and p65, respectively, and promote the degradation of target proteins by proteasomes (Fig. 3a).241–244

Ubiquitination in the RLR signaling pathway

The RLR family comprises three members: retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 (RIG-I), melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) and laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 (LGP2). The RIG-I/MDA5 receptor recognizes and binds to viral RNA and regulates the expression of antiviral genes through the MAVS-TBK1-IRF3 signaling pathway.245 Many E3 ligases are involved in regulating the downstream signaling of MAVS. For example, the E3 ligase Trim25 catalyzes the K63 polyubiquitination of RIG-I. Subsequently, MAVS is recruited, and the activation signal is transferred to the MAVS signal complex.246 Another is LUBAC, which decreases the activation of RIG-I by inhibiting the binding of Trim25 and RIG-I or mediating the polyubiquitination and degradation of Trim25.247 Similar to Trim25, RNF135 (also known as Riplet) also catalyzes the K63 polyubiquitination of RIG-I and activates the RIG-I signaling pathway.248 Additionally, the E3 ligase MIB1/2 regulates the activation of TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) by catalyzing TBK1 K63-linked polyubiquitination. The K27-linked polyubiquitination of NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO), which is mediated by Trim23 and Shigella effector IpaH9.8, can also promote the activation of the TBK1 and IKK complexes (Fig. 3b).249,250 Thus, E3 ligases have a key regulatory function in the RLR signaling pathway, and the regulation of ubiquitination on the immune response is complex and precise.

To avoid tumorigenesis caused by excessive activation of the RLR signaling pathway, host cells inhibit the overproduction of downstream inflammatory factors and interferons by ubiquitinating and degrading key proteins in the RLR signaling pathway. The E3 ligase RNF125 catalyzes the K48 linkage ubiquitination of RIG-I/MDA5 and promotes the degradation of RIG-I/MDA5 through the proteasome.251 More importantly, upon stimulation with an RNA virus, the lectin family member Siglec-G recruits the E3 ligase c-Cbl, catalyzes the K48-linked ubiquitination of RIG-I, and promotes the degradation of RIG-I.252 As a pivotal protein of the RLR signaling pathway, mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) is also regulated by ubiquitination. The poly(rC)-binding protein PCBP2 recruits the E3 ligase ITCH, which catalyzes the K48 ubiquitination of MAVS, regulates its degradation, and inhibits the activation of the RLR signaling pathway mediated by MAVS.253 Many E3s have been identified to regulate the stability of MAVS downstream signaling components. For example, NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 4 (NLRP4) recruits the E3 ligase DTX4 and promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of TBK1.254 Triad3A catalyzes the K48 polyubiquitination of TRAF3.255 The E3 ligase RNF5 promotes the K48-linked ubiquitination and degradation of MAVS (Fig. 3b).256

Ubiquitination in the STING-dependent signaling pathway

STING, an adapter transmembrane protein residing in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), is an important innate immune sensor for tumor detection.257–259 The STING pathway is activated by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and produces type I IFNs. Subsequently, adequately activated APCs in the TME induce CD8+ T cell priming and lead to adaptive anticancer immune responses.260 Recently, many DNA-binding proteins have been reported in the cytoplasm and include cGAS, Mre11, IFI16 (p204), DDX41 and DNA-PKcs. They recognize DNA in the cytoplasm and strongly initiate the type I interferon gene through the STING-TBK1-IRF3 signaling axis. In response to the stimulation of cytoplasmic DNA, STING on the ER can rapidly dimerize and transfer from the ER to the nuclear peripheral bodies. Interestingly, TBK1 also aggregates into the nuclear peripheral bodies and forms the STING-TBK1 complex, which is essential for the activation of TBK1 (Fig. 3c).261,262

Currently, various polyubiquitinations of STING have been identified, including polyubiquitination of K63, K48, K11 and K27, all of which play important roles in the innate immune response against RNA and DNA infections. The different connections between these polyubiquitin chains not only broaden the functional spectrum of STING but also determine its strength and duration in regulating the expression of type I interferon genes. Under the stimulation of exogenous DNA, Trim56 induces K63 linkage ubiquitination of STING and promotes STING dimerization and recruitment to TBK1.263 In addition to Trim56, the E3 ligase Trim32 promotes the interaction between STING and TBK1 by catalyzing the K63-linked polyubiquitination of STING and finally increases the expression of STING-mediated interferon-β.264 To control cancer cells, HER2 also connects with STING and recruits AKT1 to directly phosphorylate TBK1, which prevents TBK1 K63-linked ubiquitination.265 Additionally, K48 polyubiquitination also inhibits signal transduction by promoting the degradation of STING. In detail, under the stimulation of DNA or RNA, RNF5 catalyzes the K48 polyubiquitination of STING at K150 and K48. This modification serves as a proteolytic signal by targeting STING for degradation via the 26S proteasome.266 The E3 ligase RNF26 localized on the ER catalyzes the ubiquitination of the K11 linkage of STING. In the early stage of viral infection, the K11 polyubiquitin chain catalyzed by RNF26 competes with the K48 ubiquitination of STING, prevents the RNF5-mediated degradation of STING, and increases the expression of type I interferon, whereas in the late stage of a viral infection, RNF26 inhibits the expression of type I interferon by promoting lysosomal degradation of IRF3.267 In addition, K27-linked polyubiquitination of STING induced by autocrine motility factor receptor (AMFR) works as a molecular platform to recruit TBK1 and promotes the translocation of TBK1 to the nuclear peripheral bodies (Fig. 3c).268

Modification of the K27- and K63-linked ubiquitination chains of STING activates anti-DNA viral effects in cells. USP21 can interact directly with STING and remove the K27 and K63 Ub chains on STING, thereby inhibiting the production of type I interferons. In the late stage of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) infection, protein kinase p38 phosphorylates USP21 and recruits it to bind to STING. Inhibiting the activity of p38 in mice blocks the binding of USP21 to STING, which in turn protects mice from an HSV-1 infection by inhibiting the production of type I interferons. Additionally, in USP21 knockout mice, resistance to DNA viruses was enhanced (Fig. 3c).269

Ubiquitination in CSC stemness maintenance

The “stemness” state of stem cells is the key ability to self-renew and differentiate into the germline. Stem cells can be found in adult and embryonic tissues and play an extremely important role in cell regeneration, growth and embryonic development. CSCs are a subpopulation of tumor masses with pluripotent tumorigenesis, metastasis dissemination, drug resistance and cancer recurrence.270 In CSCs, a fine-tuning circuit consisting of a core set of transcription factors regulates stemness-specific gene expression profiles, including the core stem cell regulator triplet, Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog.271–273 In addition, some signaling pathways, including the Hippo and Wnt signaling pathways, also participate in CSC stemness maintenance. Ubiquitination plays an important role in CSC characteristics, such as self-renewal, maintenance, differentiation and tumorigenesis. By comparing the protein expression and ubiquitination levels between pluripotent and differentiated stem cells via quantitative proteomics, Iannis surprisingly found the ubiquitination of core transcription factors, which included Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2, indicating the crucial roles of the ubiquitination-mediated transcriptional regulatory network in maintaining the stemness and pluripotency of stem cells.274 This section focuses on the recent progress in the ubiquitination-mediated transcriptional regulatory network and signaling pathways in maintaining the stemness and pluripotency of stem cells.

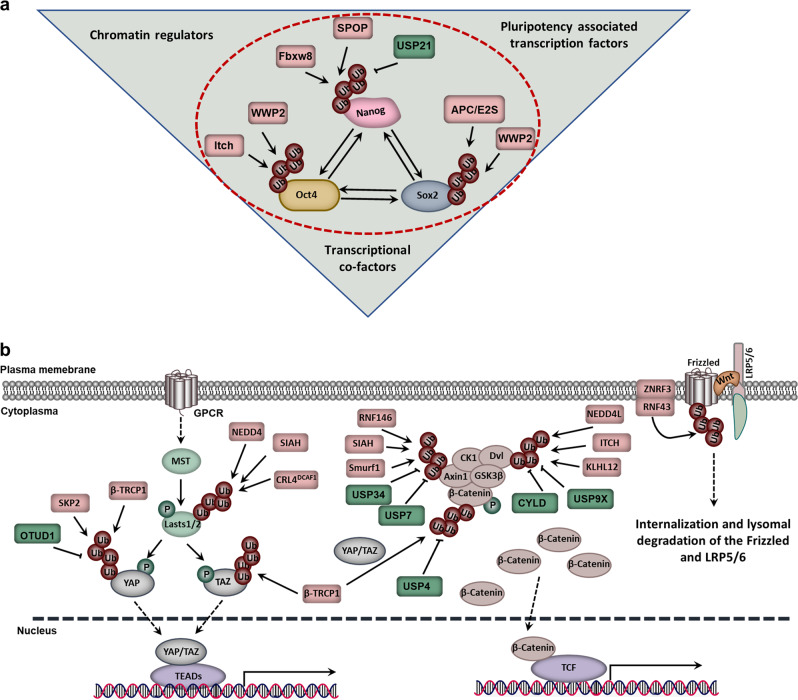

Nanog ubiquitination

As the key transcription factor for maintaining stem cell pluripotency and promoting somatic cell reprogramming, Nanog is mainly regulated by its allele, transcription factors and PTM in stem cells. Nanog contains a degradation determinant PEST sequence with a very short half-life. However, the regulatory mechanism of Nanog stability was unclear until 2014. Researchers identified that ERK1 phosphorylated the Ser52 of Nanog and promoted its interaction with Fbxw8, which played an important role in Nanog's proteasome pathway degradation and the differentiation of stem cells (Fig. 4a).275

Fig. 4.

Ubiquitination in cancer stem cell (CSC) stemness maintenance. a The ubiquitination-mediated regulation of the transcriptional regulatory network in maintaining the stemness of stem cells. b Ubiquitination in the Wnt and HIPPO signaling pathways

In addition to Fbxw8, another investigation proposed that SPOP, the Cullin3-dependent E3 ligase, could also mediate Nanog degradation. SPOP contains a BTB domain linked to Cullin3 and a MATH domain that specifically recognizes and binds to substrates. A variety of biological processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis and cell senescence, are regulated by SPOP by degrading a variety of substrates, such as AR, DEK, ERG, SRC3, DAXX and SENP7.276–281 Two independent studies revealed that the Pin1 or AMPK-BRAF signaling pathway phosphorylated Nanog-Ser68; then, the modified Nanog was recognized and polyubiquitinated by SPOP and finally degraded via the proteasome (Fig. 4a).282,283

As ubiquitination is a reversible process, Nanog may also be regulated by deubiquitinating enzymes during stem cell or somatic cell reprogramming. To screen the DUB of Nanog, the deubiquitinating enzyme USP21 was identified by the efficient dual-luciferase reporter assay system. USP21 could significantly enhance the stability of Nanog and then maintain the self-renewal of stem cells. The interaction between USP21 and Nanog could be blocked by ERK-mediated phosphorylation at position 539 of USP21, which subsequently promoted the differentiation of stem cells by downregulating the stability of Nanog.284,285 Additionally, USP21 was also reported to maintain the self-renewal of embryonic stem cells by stabilizing Nanog (Fig. 4a).285,286

Oct4 ubiquitination

As a member of the POU transcription factor family, Oct4 plays a key role in maintaining the stemness and pluripotency of stem cells.287 In stem cells, the protein level of Oct4 is accurately regulated, and the abnormal expression of Oct4 is the main cause of somatic cell cloning failure. In terms of the regulation of Oct4, the UPS plays an important role. WWP2, an E3 ligase of the HECT family, interacts directly with Oct4 and mediates its proteasome degradation by promoting its ubiquitination.288,289 Additionally, the E3 ligase ITCH can also interact with Oct4, promote its ubiquitination and then regulate Oct4 transcription activation; however, ITCH cannot mediate the degradation of Oct4 (Fig. 4a).288 The different functions of the two E3 ligases for Oct4 in stem cells suggest that the same substrate can be regulated by different E3 ligases. In addition, ERK1 can phosphorylate Ser111 of Oct4, induce its ubiquitination and promote its degradation and cytoplasm location.289

Sox2 ubiquitination

Similar to Oct4 and Nanog, the protein level of the core transcription factor Sox2 is also regulated by the UPS in stem cells.290 In 2014, the methylation enzyme Set7 was found to induce the monomethylation of Sox2. It not only inhibited the expression of Sox2 but also promoted the ubiquitination of Sox2 by facilitating the interaction between WWP2 and Sox2. Thus, Set7 can mediate the degradation of Sox2 and stem cell differentiation. In contrast, AKT phosphorylates Sox2 and inhibits the Set7-mediated methylation of Sox2, thereby inhibiting the ubiquitination of Sox2 and maintaining the self-renewal of stem cells, suggesting that Sox2 is precisely regulated by PTM to maintain stem cell pluripotency and direct differentiation.291 As an important regulator of stem cell self-renewal, Sox2 can also interact with APC and Ube2s directly, which mediates the degradation of Sox2 by promoting K11 linkage ubiquitination at the Lys123 of Sox2 (Fig. 4a).292–295

In addition, USP7 is able to maintain stem cell self-renewal by inhibiting the E3 ubiquitin ligase β-TrCP1-mediated ubiquitination of REST, a stemness transcription factor that plays an important role in neural differentiation (Fig. 4a).296 In addition to USP7, many deubiquitinating enzymes have been identified in transcriptional regulation in stem cells based on genome-wide localization analysis. For example, USP10, USP16, USP3, USP37 and USP44 are reported to bind to the promoter of Nanog; USP44 is capable of binding to the promoter of Oct4; and USP22, USP25, USP44 and USP49 are proven to bind to the promoter of Sox2.273

Ubiquitination in the Wnt signaling pathway

The Wnt signaling pathway is an evolutionarily conserved signaling pathway that is critical in regulating CSCs.297 In the absence of Wnt on the cell surface, the “destructive complex” of β-catenin, a multisubunit complex consisting of four proteins, GSK3β, Axin, casein kinase 1α (CK1α) and adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), can bind to β-catenin and promote its phosphorylation at the N-terminus via CK1α and GSK3β. β-TrCP1 can recognize phosphorylated β-catenin and promote its ubiquitination and degradation, thereby negatively regulating the Wnt signaling pathway.298–300 As a ligand, Wnt bridges the Frizzled-LRP5/6 protein and phosphorylates LRP5/6 through CK1a. Subsequently, it recruits the “destructive complex” to the cell membrane, inhibits the phosphorylation and ubiquitination of β-catenin and promotes its accumulation in the nucleus to regulate CSC stemness maintenance.301,302

In addition to the degradation of β-catenin, the internalization and lysosomal degradation of Frizzled-LRP5/6 can be regulated by the E3 ligases ZNRF3- and RNF43-mediated ubiquitination. It is also an important way to negatively regulate Wnt signaling.303–306 As a feedback regulator of Wnt signaling, inactivation of RNF43 and ZNRF3 leads to a significant expansion of the crypt proliferation region and promotes tumorigenesis. Moreover, RNF43 inactivating mutations can be found in various cancers.307,308

Axin is a key scaffold protein in the “destructive complex”, and its regulation is associated with the Wnt signaling pathway. For example, the E3 ligase RNF146 promotes ubiquitination-mediated proteasomal degradation of Axin on the basis of the PARsylation of Axin,309,310 while SIAH binds to Axin and mediates its degradation, which amplifies the feedback regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway.311 Unlike the degradation signal, SMURF1 inhibits its interaction with LRP5/6 by mediating the K29-linked polyubiquitination of Axin and negatively regulates the Wnt signaling pathway.312

Notably, UPS also regulates the ubiquitination of different components in the Wnt signaling pathway. For example, Nedd4L, ITCH and KLHL12 are able to negatively regulate the Wnt signaling pathway by targeting Disheveled (Dvl) degradation.313–315 In addition, the deubiquitinating enzymes USP34/USP7, CYLD/USP9X and USP4 can bind to Axin, Dvl and β-catenin, respectively, thereby promoting the nuclear localization of β-catenin and the Wnt signaling pathway by inhibiting their ubiquitination.316–320

Ubiquitination in the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway

In mammals, the Hippo signaling pathway can also maintain CSC stemness, regulate cell growth, control the size of organs and take part in tumorigenesis.321,322 Ubiquitination also plays an important role in regulating the Hippo signaling pathway, with a variety of E3 ligases being identified. For example, CRL4DCAF1 negatively regulates the Hippo signaling pathway by ubiquitinating and degrading Lats1 while promoting the monoubiquitination of Lats2 and inhibiting its activity.323 Similarly, the stability of Last2 is also regulated by the E3 ligase SIAH2. SIAH2, an important regulator of the HIF signaling pathway, degrades PHD3/1 by ubiquitination in a hypoxic environment. In turn, the activation of the Hippo signaling pathway also controls the stability of HIF1α and the HIF1α signaling pathway (Fig. 4b).194,324 This part of the work highlights the important roles of the hypoxic environment in regulating the ubiquitination of the Hippo signaling pathway.

YAP/TAZ is the key component in the Hippo signaling pathway. The stability of YAP/TAZ is also controlled by PTM. For example, phosphorylated YAP is recognized and ubiquitinated by the E3 ligase β-TrCP1.325 The CK1ε-mediated phosphorylation of TAZ is recognized by β-TrCP1 and promotes the Κ48-linkage ubiquitination of TAZ. The ubiquitination of TAZ mediates its entrance into the proteasome for degradation (Fig. 4b).326 Unlike K48 linkage ubiquitination, a recent report indicated that the E3 ligase SKP2 induces the nonproteolytic K63 linkage ubiquitination of YAP and leads to its nuclear localization and interaction with the nuclear binding partner TEAD. In this process, OTUD1 could remove the K63 linkage ubiquitination of YAP and negatively regulate transcriptional activity and cell growth (Fig. 4b).327

The Wnt signaling pathway, associated with CSC stemness maintenance, also plays an important role in regulating the stability and degradation of TAZ. Phosphorylated β-catenin can serve as a platform for TAZ and β-TrCP1 and promotes TAZ degradation by β-TrCP1.328 Moreover, YAP/TAZ is essential for β-TrCP1 recruitment to the APC complex and β-catenin inactivation. Under Wnt OFF conditions, YAP/TAZ is sequestered in the APC complex by binding to Axin1 and then recruiting β-TrCP1 to degrade β-catenin. Under Wnt ON conditions, YAP/TAZ is dissociated from Axin1 and accumulates in the nucleus to regulate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.329 In addition to the Ub ligases reported above, the K48 linkage polyubiquitination mediated by Nedd4 also functions as a proteolytic signal and degrades WW45 and Last1/2 via the proteasome (Fig. 4b).330 Taken together, these clues indicate that ubiquitination can regulate the Hippo and Wnt signaling pathways by controlling the stability of different substrates.

Cancer therapeutic strategy via targeting the UPS

As mentioned above, the UPS plays an essential role in protein degradation and fundamental cellular process regulation.331,332 Genetic alterations, abnormal expression or dysfunction of the UPS often lead to human pathogenesis, especially cancer. Thus, these components can serve as potential drug targets for therapeutic strategies against cancer.8 Currently, many small molecule inhibitors have been developed that target different components of the UPS, which include the proteasome, E3 ligases, E1 enzymes, E2 enzymes and DUBs, and their therapeutic effects are gradually being tested.333

Targeting the proteasome activity

Among all UPS components, only the proteasome has been successfully exploited as a therapeutic target for the clinical treatment of cancer. Tangible success has been achieved using proteasome inhibitors (PIs), such as bortezomib, carfilzomib, oprozomib and ixazomib (Fig. 4b).334,335 Under normal physiological conditions, selective tagging of proteins with Ub is targeted to the proteasome and results in proteasome-mediated proteolysis.336 The proteasome exhibits three distinct activities, namely, chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like and caspase-like activities. Its alterations are found in various human diseases. In tumorigenesis, proteasome abnormalities are not observed; thus, the function of the proteasome in tumor cells may be on the basis of their own needs.11

The boronic acid derivative bortezomib (Velcade, Millennium Pharmaceuticals), a unique first-in-class compound, can slowly and reversibly block chymotrypsin-like and decrease trypsin-like and caspase-like activities of the 20S proteasome.337 Previous studies have proven that bortezomib can inhibit proliferation and induce cell apoptosis by blocking the NF-κB pathway, activating the c-Jun/AP-1 pathway and increasing cyclin-CDK inhibitors (p21 and p27) in various tumor cell lines, such as squamous cell carcinoma, multiple myeloma (MM), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), hepatocellular carcinoma and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).338–343 In the clinic, it is the first approved PI by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for relapsed MM344 and MCL.345 Later, it was expanded for use in patients with NSCLC and pancreatic cancer.346 Despite its promising results, some off-target and adverse effects, such as fatigue, asthenia, thrombocytopenia, peripheral neuropathy and gastrointestinal symptoms, also limit its application.347,348 The off-target effects may lead to dose-limiting toxicity and subsequently result in permanent nerve damage to the extremities, called bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy (BIPN).349 Moreover, bortezomib resistance may occur within an average of 1 year, especially for solid tumors.350–352 The resistance mechanism includes an enhanced aggresome-autophagy pathway, increased expression of proinflammatory macrophages, alterations in apoptotic signaling and decreased ER stress response.353,354

Another approved PI for relapsed or refractory MM is carfilzomib (PR-171; Kyprolis; Onyx Pharmaceutical), a second-in-class PI (Fig. 5).355 Similar to bortezomib, carfilzomib also inhibits the chymotrypsin-like activity of the 20S proteasome. However, unlike bortezomib, the activity of carfilzomib is irreversible. In addition, carfilzomib is more effective than bortezomib in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells by inducing apoptosis and inhibiting proliferative activity.356 It also shows improved safety in terms of peripheral neurotoxicity and maintains its cytotoxic potential in bortezomib-resistant cell lines.357 Due to the good tolerance and promising efficacy for MM in phase I and II clinical trials, carfilzomib was approved by the FDA for the treatment of relapsed MM patients who experience disease progression within 60 days after the treatment of bortezomib and immunomodulatory drugs.358 Carfilzomib treatment can also cause adverse effects, such as cardiovascular complications (hypertension, heart failure), hematologic complications (thrombocytopenia, anemia), gastrointestinal complications (diarrhea, nausea/vomiting) and systemic symptoms (fever, fatigue). Therefore, its treatment should also be monitored carefully359,360

Fig. 5.

Cancer therapeutic strategy by targeting the UPS

As a new generation of PIs, oprozomib (ONX0912; PR-047) is designed as a tripeptide analog of carfilzomib (Table 1).361 In contrast to intravenously administered bortezomib and carfilzomib, oprozomib has better oral bioavailability and is suitable for oral administration. It also has a similar antitumor activity, potency and selectivity as carfilzomib in MM and can be used to treat bortezomib-, dexamethasone- or lenalidomide-resistant MM.362 In the treatment of solid tumors, it induces cell apoptosis by upregulating proapoptotic Bik and Mcl-1.363 However, due to oral administration, oprozomib has a high rate of gastrointestinal toxicities and unstable pharmacokinetics.364

Table 1.

Selected compounds targeting the UPS

| Target | Compounds | Molecular mechanisms | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20S proteasome | Bortezomib507 | Inhibition of proteasome-mediated proteolysis, which may lead to cell cycle arrest or apoptosis or inhibit the tumor growth. | FDA approved for MM, MCL, NSCLC and PaCa |

| Carfilzomib508 | Inhibition of proteasome-mediated proteolysis, which may lead to cell cycle arrest or apoptosis or inhibit the tumor growth. | FDA approved for relapsed and refractory MM | |

| MLN9708509 | A second-generation small-molecule proteasome inhibitor that displays antitumor activity in a variety of mouse models of HM. | Phase III for MM | |

| Marizomib371 | A novel proteasome inhibitor that exhibits effects in patients with refractory and relapsed MM. | Phase III for Glioblastoma | |

| CRBN | Thalidomide510,511 | Binds to CRBN and suppresses its activity. | FDA approved for MM |

| Lenalidomide, Pomalidomide512–514 | Binds to CRBN and suppresses its activity. | FDA approved for refractory MM | |

| Mdm2 | PRIMA387,515,516 | Restores transcriptional activity of unfolded wild-type or mutant p53. | FDA approved for LiCa and PaCa |

| Serdemetan517,518 | Increases p53 levels and inhibits proliferation, formation of the capillary tube and migration of HMEC-1 cells. | Phase I for solid tumor | |

| RG7112519 | Increases p53 levels and transcriptional activation of p53 target genes. | Phase I for HM | |

| RG738861,520,521 | Increases p53 levels and signaling and suppresses neuroblastoma cell growth. | Preclinical/research | |

| RITA383 | A small molecule inhibitor preventing the interaction between p53 and Mdm2 in the A-498 and TK-10 cell lines. | Preclinical/research | |

| HLI373389,397 | Increases p53 levels through inhibiting Hdm2-mediated ubiquitination in U2OS cells. | Preclinical/research | |

| MEL23390 | Increases p53 levels in U2OS, RKO and HCT116 cultures, and shown to induce RKO and MEF cell death. | Preclinical/research | |

| Nutlin-3a522 | Inhibits the growth of HM, GBM and AML cells by activating the p53-dependent apoptotic pathway. | Preclinical/research | |

| HLI98388 | Activates p53 signaling and inhibits the tumor cell growth. | Preclinical/research | |

| MdmX | SJ-172550523 | Inhibits the MDMX-p53 interaction in cultured retinoblastoma cells. | Preclinical/research |

| NSC207895395 | Inhibits MDMX expression in MCF-7 cells. | Preclinical/research | |