The proportion of adolescents reporting minority sexual orientation identity and same-sex sexual contacts increased between 2009 and 2017, while disparities in suicide attempts persisted.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Sexual minority adolescents face mental health disparities relative to heterosexual adolescents. We evaluated temporal changes in US adolescent reported sexual orientation and suicide attempts by sexual orientation.

METHODS:

We used Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance data from 6 states that collected data on sexual orientation identity and 4 states that collected data on sex of sexual contacts continuously between 2009 and 2017. We estimated odds ratios using logistic regression models to evaluate changes in reported sexual orientation identity, sex of consensual sexual contacts, and suicide attempts over time and calculated marginal effects (MEs).

RESULTS:

The proportion of adolescents reporting minority sexual orientation identity nearly doubled, from 7.3% in 2009 to 14.3% in 2017 (ME: 0.8 percentage points [pp] per year; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.6 to 0.9 pp). The proportion of adolescents reporting any same-sex sexual contact increased by 70%, from 7.7% in 2009 to 13.1% in 2017 (ME: 0.6 pp per year; 95% CI: 0.4 to 0.8 pp). Although suicide attempts declined among students identifying as sexual minorities (ME: −0.8 pp per year; 95% CI: −1.4 to −0.2 pp), these students remained >3 times more likely to attempt suicide relative to heterosexual students in 2017. Sexual minority adolescents accounted for an increasing proportion of all adolescent suicide attempts.

CONCLUSIONS:

The proportion of adolescents reporting sexual minority identity and same-sex sexual contacts increased between 2009 and 2017. Disparities in suicide attempts persist. Developing and implementing approaches to reducing sexual minority youth suicide is critically important.

What’s Known on This Subject:

The proportion of the population that identifies as sexual minorities may be increasing over time. How sexual orientation and related health disparities are changing over time in the United States remains unstudied in a consistent sample over time.

What This Study Adds:

Between 2009 and 2017, the proportion of US adolescents identifying as sexual minorities increased 96%, from 7.3% to 14.3%. The proportion of adolescents reporting same-sex sexual contacts increased 70%, from 7.7% to 13.1%. Sexual minority disparities in suicide attempts persisted.

Adolescence is a time of sexual and social development and increased risk for mental health disorders, suicide, substance abuse, and sexually transmitted disease transmission.1 Adolescents who are sexual minorities, defined as having same-sex attraction, behavior, or orientation, face elevated levels of each of these health risks, particularly suicide.2–4 Those identifying as sexual minorities have nearly 5 times the rate of suicide attempts relative to their heterosexual peers on the basis of representative data from the Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance Survey (YRBSS).2 The disproportionate burden of poor mental health among sexual minorities has been linked to stigma.5,6

Adolescents are developing in a changing societal context for sexual minorities. Public support for same-sex marriage has increased over time, from 37% in 2009 to 62% in 2017.7 Same-sex marriage, linked to improved mental health,8,9 has been legal across the United States since 2015.10 At the same time, recent years have seen a rise in state and national policies curtailing sexual minority rights and linked to worse mental health.11,12 Changes in the social context may affect sexual orientation identity and reporting.

Each of the 3 dimensions of sexual orientation—attraction, identity, and the sex of sexual partners—may differ from each another, may change over time among individuals and in populations, and may be influenced by the broader social context.13–15 There is evidence of broad underreporting of same-sex attraction, sexual minority identity, and same-sex sexual behavior, even on anonymous surveys.16 In a study of adult women in the United States, legal recognition of same-sex relationships was associated with women reporting that their sexual orientation identity changed from heterosexual to a minority sexual orientation over time.17

Little previous research has evaluated how reported sexual orientation and related health disparities have changed over time. Based on representative data from adults in Britain, reports of lifetime same-sex sexual contact increased from 4% to 16% among women and from 6% to 7% among men between a 1990 and 1991 survey wave and a 2010–2012 survey wave, a period when support for same-sex relationships increased.18 Although few surveys representative of the US population have included questions on sexual orientation until recent years, some YRBSS states have included sexual orientation questions for several years. A previous analysis of changes in sexual orientation over time based on YRBSS data found increases in the proportion of adolescents reporting sexual minority identities and same-sex sexual contact between 2005 and 2015,19 but the study was based on potentially overlapping data from states and cities in different combinations across years (7 sites in 2005, increasing to 42 sites by 2015), making it difficult to determine if changes over time were due to the sites included in each year or changes in sexual orientation.20 The study also did not include evaluation of changes in mental health disparities over time.

Understanding temporal changes in the proportion of adolescents who are sexual minorities and changes in suicidality among those who are sexual minorities is important to guide policies and programs that reduce health disparities, particularly at a time of increasing adolescent suicide fatalities.21 We estimated population-level changes in adolescent sexual orientation identity, same-sex sexual contacts, and suicide attempts on the basis of YRBSS data from states that continuously collected representative data between 2009 and 2017.

Methods

Sample

We used data from high school students from the state-level YRBSS.22 The YRBSS is a repeated cross-sectional survey conducted in every odd year through partnerships between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and state health or education departments. The YRBSS uses 2-stage sampling and population weighting to develop a sample representative of students in each state. States decide which questions to include in the YRBSS. Whereas <10 states collected sexual orientation data in 2009, 32 states did so in 2017.

We defined 3 samples. Sample A consisted of YRBSS data from adolescents from the 6 states that collected information on sexual orientation identity in each survey year between 2009 and 2017 and that maintained a consistent sampling frame during that time period: Delaware, Illinois, Massachusetts, Maine, North Dakota, and Rhode Island. Sample B consisted of YRBSS data from adolescents from a different set of the 4 states that collected information on the sex of sexual contacts in each survey year between 2009 and 2017, that maintained a consistent sampling frame during that time period, and that also collected data on whether adolescents had ever been forced to have sexual contact: Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, and Rhode Island. We excluded sample B participants without any sexual contact as well as those who reported being forced to have sexual contact; it was not possible to determine the extent to which such contact was consensual. Sample C consisted of YRBSS data from adolescents in a subset of all 3 states that collected data on sexual orientation identity, the sex of sexual contacts, and sexual assault and that maintained a consistent sampling frame each year between 2009 and 2017: Delaware, Illinois, and Rhode Island. In sample C, we again excluded adolescents with no sexual contacts and who reported sexual assault. We could not investigate questions about gender identity because too few states included questions on gender identity. This study was exempt from institutional review board approval because it involved only the use of anonymous, secondary data.

Exposures

The main exposure of interest was time in years, measured as a linear term between 2009 and 2017.

Outcomes

There were 3 main outcomes of interest. The first outcome was reported sexual orientation identity, defined as any response other than “heterosexual” to the question, “Which of the following best describes you?” with 4 response categories: heterosexual, gay or lesbian, bisexual, or not sure. The second outcome was same-sex sexual contacts based on the respondent’s sex and the question, “During your life, with whom have you had sexual contact?” and response options of female, male, or female and males. The third outcome was ≥1 suicide attempt based on the question, “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” We chose this binary outcome as the standard CDC approach to reporting suicide23 and because of particularly large disparities in suicide attempts by sexual orientation.2

Analyses

We conducted 4 main analyses, estimating odds ratios by conducting logistic regression analyses and calculating the marginal effects (MEs) at the mean value of covariates. We adjusted for race and ethnicity, sex, age in years, and state of residence in all analyses. We included weights calculated by the CDC to make the YRBSS population representative of all students in each state. We used linearized SEs, which are robust to heteroskedasticity.

We first estimated whether there were changes in reported sexual orientation identity over time using the 6-state sample A. We conducted the analyses among all adolescents and by sex. Second, we evaluated changes in reported same-sex sexual contacts over time using data from adolescents in the 4 sample B states among all adolescents and by sex. Third, we evaluated changes in reported sexual orientation identity among all sample C adolescents, by sex of sexual contact and by sex. Finally, we evaluated temporal changes in suicide attempts over time by sexual orientation (sample A) and by the sex of sexual contacts (sample B) overall and by sex through logistic regression analyses. Finally, we tabulated the proportion of all students who were both sexual minorities and reported suicide attempts and the proportion of suicide attempts that were among sexual minorities. We conducted all analyses in Stata version 12 (Stat Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

We describe the 3 samples in Table 1. Sample A consisted of 110 243 adolescents from 6 states that collected data on sexual orientation identity between 2009 and 2017. Sample B consisted of 25 994 adolescents from 4 states that collected data on the sex of sexual contacts and on sexual assault between 2009 and 2017. Sample C consisted of 20 655 sexually active adolescents from 3 states that collected data on sexual orientation identity, the sex of sexual contacts, and sexual assault between 2009 and 2017. Across the samples, the proportion of adolescents who were non-Hispanic white ranged from 56% to 63%, the proportion of adolescents who were non-Hispanic African American ranged from 13% to 19%, and the proportion of adolescents who were Hispanic ranged from 17% to 19%.

TABLE 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Sample A: Adolescents From 6 States That Collected Data on Sexual Orientation Identity (N = 110 243) | Sample B: Sexually Active Adolescents From 4 States That Collected Data on Sex of Sexual Contact and Sexual Assault (N = 25 994) | Sample C: Sexually Active Adolescents From 3 States That Collected Data on Sexual Orientation Identity, Sex of Sexual Contact, and Sexual Assault (N = 20 655) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age in years | |||

| ≤14 | 13 314 (10.1) | 1965 (6.6) | 1490 (6.2) |

| 15 | 27 822 (24.9) | 5325 (19.9) | 4226 (20.2) |

| 16 | 28 922 (25.9) | 7229 (25.8) | 5767 (25.9) |

| 17 | 26 416 (24.1) | 7445 (28.8) | 5999 (28.8) |

| ≥18 | 13 769 (15.0) | 4030 (18.9) | 3173 (18.9) |

| Race and/or ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 71 738 (63.3) | 12 333 (57.8) | 9211 (56.3) |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 10 981 (12.8) | 5000 (17.7) | 4444 (19.0) |

| Hispanic | 16 279 (16.7) | 6501 (19.1) | 5245 (19.3) |

| Another race and/or ethnicity | 11 245 (7.2) | 2160 (5.3) | 1755 (5.5) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 56 208 (50.3) | 13 613 (46.7) | 9824 (53.1) |

| Female | 54 035 (49.7) | 12 381 (53.3) | 10 831 (46.9) |

Percent estimates include weights to make data representative of the full population.

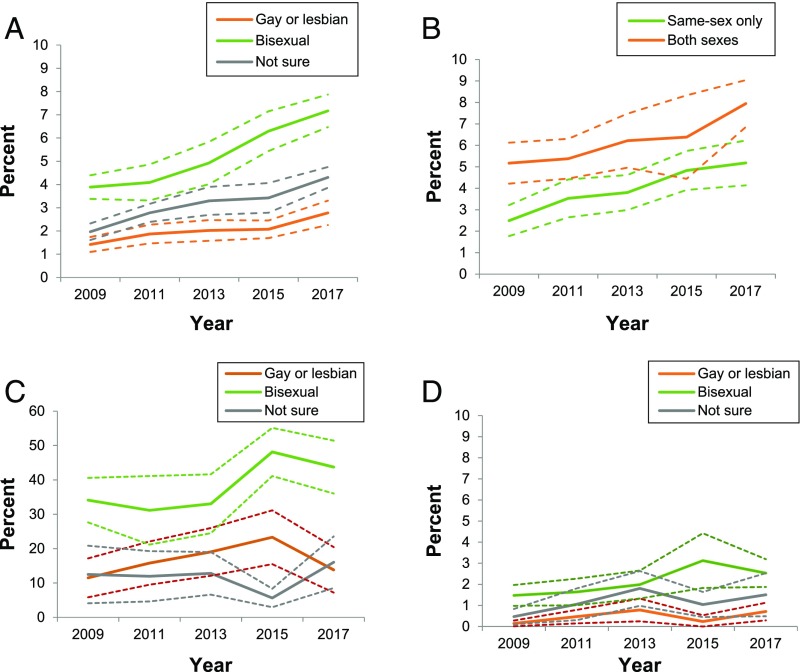

Among all adolescents in the 6 states that collected data on sexual orientation identity (sample A), the proportion of adolescents identifying as heterosexual declined from 92.7% in 2009 to 85.7% in 2017; the proportion of adolescents who identified as sexual minorities increased 96%, from 7.3% in 2009 to 14.3% in 2017 ( ME: 0.79 percentage points [pp] per year; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.65 to 0.94 pp; Fig 1A, Tables 2 and 3). The proportion who reported identifying as gay or lesbian doubled from 1.4% in 2009 to 2.8% in 2017 (ME: 0.13 pp per year; 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.20 pp). The proportion who reported identifying as bisexual increased 85%, from 3.9% in 2009 to 7.2% in 2017 (ME: 0.37 pp per year; 95% CI: 0.28 to 0.45 pp). The proportion who reported they were not sure of their sexual orientation identity increased 115%, from 2.0% in 2009 to 4.3% in 2017 (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 0.24 pp per year; 95% CI: 0.19 to 0.31 pp). The overall trends in sexual orientation identity were mirrored in trends for both male and female adolescents. Female adolescents were approximately twice as likely as male adolescents to identify as sexual minorities in 2017 (19.6% vs 8.9%).

FIGURE 1.

Changes in reported sexual minority orientation identity and same-sex sexual contacts over time. A, Sexual minority orientation identity over time. B, Sex of sexual contacts over time. C, Sexual orientation among students with same-sex sexual contacts. D, Sexual orientation among students with opposite-sex sexual contacts. Note that y-axis scales range from 0% to 10% for all graphs except for the bottom left (C), where the scale is from 0% to 60%. Heterosexual sexual orientation identity and opposite-sex sexual contacts are excluded from the graphs, so the graphs can be presented at a scale that improves visualization of temporal changes in sexual minority identity and in same-sex sexual contacts.

TABLE 2.

Changes in Reported Sexual Orientation Identity Over Time: 2009–2017

| Sexual Orientation Identity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterosexual | Gay or Lesbian | Bisexual | Not Sure | Any Sexual Minority (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, or Not Sure) | |

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| All adolescents (N = 110 243) | |||||

| 2009 | 92.7 (92.0 to 93.5) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) | 3.9 (3.4 to 4.4) | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.3) | 7.3 (6.5 to 8.0) |

| 2011 | 91.3 (90.2 to 92.3) | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.3) | 4.1 (3.3 to 4.9) | 2.8 (2.4 to 3.2) | 8.7 (7.7 to 9.8) |

| 2013 | 89.8 (88.5 to 91.0) | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.5) | 4.9 (4.0 to 5.8) | 3.3 (2.7 to 3.9) | 10.2 (9.0 to 11.5) |

| 2015 | 88.2 (87.0 to 89.4) | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.4) | 6.3 (5.4 to 7.2) | 3.4 (2.8 to 4.1) | 11.8 (10.6 to 13.0) |

| 2017 | 85.7 (84.4 to 87.1) | 2.8 (2.3 to 3.3) | 7.2 (6.5 to 7.9) | 4.3 (3.9 to 4.8) | 14.3 (12.9 to 15.6) |

| Female students (N = 54 035) | |||||

| 2009 | 90.8 (89.7 to 91.9) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.5) | 5.9 (5.2 to 6.7) | 2.2 (1.7 to 2.7) | 9.2 (8.1 to 10.3) |

| 2011 | 88.4 (87.0 to 90.0) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.2) | 6.4 (5.2 to 7.5) | 3.5 (2.8 to 4.2) | 11.6 (10.1 to 13.0) |

| 2013 | 87.0 (85.3 to 88.7) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.3) | 7.9 (6.4 to 9.3) | 3.4 (2.7 to 4.1) | 13.0 (11.3 to 14.7) |

| 2015 | 85.1 (83.3 to 87.0) | 1.9 (1.3 to 2.5) | 9.1 (7.9 to 10.3) | 3.8 (2.9 to 4.7) | 14.9 (13.0 to 16.7) |

| 2017 | 80.4 (78.7 to 82.0) | 2.9 (2.3 to 3.5) | 11.3 (10.2 to 12.5) | 5.4 (4.7 to 6.2) | 19.6 (18.0 to 21.3) |

| Male students (N = 56 208) | |||||

| 2009 | 94.6 (93.7 to 95.6) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.1) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.4) | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.4) | 5.4 (4.4 to 6.3) |

| 2011 | 94.1 (93.1 to 95.1) | 2.1 (1.4 to 2.7) | 1.8 (1.3 to 2.4) | 2.1 (1.6 to 2.5) | 5.9 (4.9 to 6.9) |

| 2013 | 92.4 (91.2 to 93.6) | 2.3 (1.7 to 3.0) | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.6) | 3.2 (2.4 to 4.0) | 7.6 (6.4 to 8.8) |

| 2015 | 91.2 (90.1 to 92.4) | 2.2 (1.7 to 2.7) | 3.5 (2.7 to 4.4) | 3.1 (2.3 to 3.8) | 8.8 (7.6 to 9.9) |

| 2017 | 91.1 (89.9 to 92.2) | 2.6 (2.0 to 3.3) | 3.1 (2.6 to 3.5) | 3.2 (2.6 to 3.8) | 8.9 (7.8 to 10.1) |

Sample A: sexual orientation identity among adolescents from 6 states with data on sexual orientation identity, 2009–2017.

TABLE 3.

Regression Analyses of Changes in Reported Sexual Orientation Identity of Adolescents From 6 States Per Year: 2009–2017

| Sexual Orientation Identity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterosexual | Gay or Lesbian | Bisexual | Not Sure | Any Sexual Minority (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, or Not Sure) | |

| Point Estimate (95% CI) | Point Estimate (95% CI) | Point Estimate (95% CI) | Point Estimate (95% CI) | Point Estimate (95% CI) | |

| All adolescents (N = 110 243) | |||||

| aOR | 0.91* (0.90 to 0.93) | 1.07* (1.04 to 1.11) | 1.09* (1.07 to 1.12) | 1.09* (1.07 to 1.11) | 1.10* (1.08 to 1.11) |

| pp | −0.79* (−0.94 to −0.65) | 0.13* (0.07 to 0.20) | 0.37* (0.28 to 0.45) | 0.24* (0.19 to 0.30) | 0.79** (0.65 to 0.94) |

| Female students (N = 56 208) | |||||

| aOR | 0.90* (0.88 to 0.92) | 1.11* (1.05 to 1.16) | 1.10* (1.07 to 1.12) | 1.10* (1.07 to 1.13) | 1.11* (1.09 to 1.13) |

| pp | −1.17* (−1.40 to −0.94) | 0.17* (0.09 to 0.25) | 0.65* (0.48 to 0.82) | 0.32* (0.22 to 0.42) | 1.17* (0.94 to 1.40) |

| Male students (N = 54 035) | |||||

| aOR | 0.93* (0.91 to 0.95) | 1.05** (1.01 to 1.09) | 1.09* (1.05 to 1.13) | 1.07* (1.03 to 1.12) | 1.07* (1.05 to 1.10) |

| pp | −0.46* (−0.62 to −0.31) | 0.09** (0.01 to 0.17) | 0.19* (0.11 to 0.27) | 0.17* (0.07 to 0.27) | 0.46* (0.31 to 0.62) |

Sample A: adolescents from 6 states with data on sexual orientation identity, 2009–2017. Estimates are adjusted for the age, race and/or ethnicity, and sex categories described in Table 1.

P < .01

P < .05

In the population of adolescents from 4 states with data on the sex of consensual sexual contacts (sample B), there was a decline in the proportion of adolescents who reported only opposite-sex sexual contact from 92.3% in 2009 to 86.9% in 2017; the proportion of adolescents who reported any same-sex sexual contact increased 70%, from 7.7% in 2009 to 13.1% in 2017 (ME: 0.60 pp per year; 95% CI: 0.39 to 0.80 pp; Fig 1B, Tables 4 and 5). This increase reflects both an increase in the proportion of adolescents reporting only same-sex sexual contact (2.5% in 2009 to 5.2% in 2017; ME: 0.32 pp per year; 95% CI: 0.22 to 0.42) and an increase in the proportion of adolescents reporting sexual contact with both sexes (5.2% in 2009 to 7.9% in 2017; ME: 0.26 pp per year; 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.40 pp). These trends were consistent among male and female adolescents, although the increase in the proportion of male adolescents who had sexual contact with both sexes was not significant.

TABLE 4.

Changes in Reported Sex of Sexual Contacts Over Time: 2009–2017

| Sex of Sexual Contacts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opposite-Sex Only | Same-Sex Only | Both Sexes | Any Sexual Minority (Same-Sex or Both Sexes) | |

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| All sexually active adolescents (N = 25 994) | ||||

| 2009 | 92.3 (90.9 to 93.8) | 2.5 (1.8 to 3.2) | 5.2 (4.2 to 6.1) | 7.7 (6.2 to 9.1) |

| 2011 | 91.1 (89.7 to 92.5) | 3.5 (2.6 to 4.4) | 5.4 (4.5 to 6.3) | 8.9 (7.5 to 10.3) |

| 2013 | 90.0 (88.3 to 91.7) | 3.8 (3.0 to 4.6) | 6.2 (5.0 to 7.5) | 10.0 (8.3 to 11.7) |

| 2015 | 88.8 (86.7 to 90.9) | 4.8 (3.9 to 5.7) | 6.4 (4.4 to 8.3) | 11.2 (9.1 to 13.3) |

| 2017 | 86.9 (85.0 to 88.8) | 5.2 (4.1 to 6.2) | 7.9 (6.9 to 9.0) | 13.1 (11.2 to 15.0) |

| Sexually active female students (N = 12 381) | ||||

| 2009 | 89.4 (86.8 to 92.0) | 2.6 (1.7 to 3.5) | 8.0 (5.8 to 10.2) | 10.6 (8.0 to 13.2) |

| 2011 | 87.7 (85.1 to 90.3) | 4.2 (2.9 to 5.5) | 8.1 (6.2 to 10.1) | 12.3 (9.7 to 14.9) |

| 2013 | 85.4 (82.6 to 88.3) | 3.8 (2.6 to 5.0) | 10.8 (8.4 to 13.1) | 14.6 (11.7 to 17.4) |

| 2015 | 85.4 (82.0 to 88.8) | 5.5 (4.2 to 6.9) | 9.1 (6.2 to 12.0) | 14.6 (11.2 to 18.0) |

| 2017 | 82.0 (79.9 to 84.1) | 5.9 (4.6 to 7.1) | 12.1 (10.6 to 13.6) | 18.0 (15.9 to 20.1) |

| Sexually active male students (N = 13 613) | ||||

| 2009 | 94.8 (93.6 to 96.0) | 2.4 (1.5 to 3.3) | 2.8 (1.7 to 3.8) | 5.2 (4.0 to 6.4) |

| 2011 | 94.2 (92.8 to 95.5) | 3.0 (1.9 to 4.0) | 2.9 (1.8 to 3.9) | 5.8 (4.5 to 7.2) |

| 2013 | 93.7 (92.2 to 95.2) | 3.8 (2.9 to 4.8) | 2.5 (1.5 to 3.5) | 6.3 (4.8 to 7.8) |

| 2015 | 91.9 (89.9 to 93.9) | 4.2 (3.1 to 5.3) | 3.9 (2.0 to 5.8) | 8.1 (6.1 to 10.1) |

| 2017 | 91.3 (89.4 to 93.2) | 4.8 (3.2 to 5.9) | 4.1 (2.9 to 5.3) | 8.7 (6.8 to 10.6) |

Sample B: sex of sexual contacts among adolescents from 4 states with data on sex of sexual contacts and sexual assault, 2009–2017.

TABLE 5.

Regression Analyses of Changes in Reported Sex of Sexual Partners of Adolescents From 4 States Per Year: 2009–2017

| Sex of Sexual Contacts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opposite-Sex Only | Same-Sex Only | Both Sexes | Any Sexual Minority (Same-Sex or Both Sexes) | |

| Point Estimate (95% CI) | Point Estimate (95% CI) | Point Estimate (95% CI) | Point Estimate (95% CI) | |

| All sexually active adolescents (N = 25 994) | ||||

| aOR | 0.93* (0.91 to 0.95) | 1.10* (1.06 to 1.13) | 1.05* (1.03 to 1.09) | 1.08* (1.05 to 1.10) |

| pp | −0.60* (−0.80 to −0.39) | 0.32* (0.22 to 0.42) | 0.26* (0.12 to 0.40) | 0.60* (0.40 to 0.80) |

| Sexually active female students (N = 12 381) | ||||

| aOR | 0.93* (0.90 to 0.96) | 1.10* (1.06 to 1.15) | 1.05* (1.02 to 1.10) | 1.08* (1.04 to 1.11) |

| pp | −0.85* (−1.21 to −0.49) | 0.38* (0.22 to 0.53) | 0.46* (0.14 to 0.77) | 0.85* (0.49 to 1.21) |

| Sexually active male students (N = 13 613) | ||||

| aOR | 0.93 (0.90 to 0.96) | 1.09* (1.04 to 1.13) | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.11 | 1.07* (1.04 to 1.11) |

| pp | −0.42* (−0.63 to −0.22) | 0.26* (0.14 to 0.39) | 0.15 (−0.02 to 0.32) | 0.42* (0.22 to 0.63) |

Sample B: adolescents from 4 states with data on sex of sexual contacts and sexual assault, 2009–2017. Estimates are adjusted for the age, race and/or ethnicity, and sex categories described in Table 1.

P < .01

In the subset of adolescents with data on sexual orientation identity and sexual contact (sample C), those who had same-sex sexual contacts had 48.3 (95% CI: 38.6 to 60.6) times the odds of reporting sexual minority orientation identity relative to peers with only opposite-sex sexual contacts. Among those with same-sex sexual contacts, the proportion of adolescents reporting they were heterosexual declined from 41.9% in 2009 to 26.4% in 2017 (ME: −2.42 pp per year; 95% CI: −3.88 to −0.97; Fig 1C, Tables 6 and 7). There were no changes in the proportion reporting they were gay or lesbian (11.5% in 2009 and 13.8% in 2017; ME: 0.45 pp per year; 95% CI: −0.53 to 1.44 pp) or not sure of their sexual orientation (12.5% in 2009 and 16.0% in 2017; ME: 0.02 pp per year; 95% CI: −1.14 to 1.19 pp). There were increases in the proportion of adolescents who reported identifying as bisexual from 34.1% in 2009 to 43.7% in 2017, a 28% relative increase (ME: 2.01 pp per year; 95% CI: 0.73 to 3.30 pp).

TABLE 6.

Changes in Reported Alignment of Sexual Orientation Identity and Sex of Sexual Contacts Over Time: 2009–2017

| Heterosexual | Gay or Lesbian | Bisexual | Not Sure | Any Sexual Minority (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, or Not Sure) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| All sexually active adolescents (N = 20 655) | |||||

| 2009 | 94.1 (92.8 to 95.4) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.4) | 3.7 (3.0 to 4.3) | 1.3 (0.6 to 2.0) | 5.9 (4.6 to 7.2) |

| 2011 | 92.1 (90.3 to 93.8) | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.4) | 4.2 (3.0 to 5.3) | 2.0 (1.0 to 3.0) | 7.9 (6.2 to 9.7) |

| 2013 | 89.6 (87.8 to 91.4) | 2.5 (1.6 to 3.5) | 5.0 (3.7 to 6.3) | 2.9 (2.0 to 3.7) | 10.4 (8.6 to 12.2) |

| 2015 | 87.5 (84.8 to 90.1) | 2.8 (1.8 to 3.9) | 8.2 (5.9 to 10.4) | 1.6 (0.8 to 2.3) | 12.5 (9.9 to 15.2) |

| 2017 | 86.9 (85.0 to 88.8) | 2.3 (1.3 to 3.3) | 7.5 (6.0 to 9.0) | 3.3 (2.2 to 4.4) | 13.1 (11.2 to 15.0) |

| Sexually active adolescents with any same-sex sexual contact (N = 2200) | |||||

| 2009 | 41.9 (32.0 to 51.9) | 11.5 (5.8 to 17.2) | 34.1 (27.6 to 40.6) | 12.5 (4.1 to 20.9) | 58.1 (48.1 to 68.0) |

| 2011 | 41.1 (31.6 to 50.6) | 15.8 (9.5 to 22.1) | 31.1 (21.1 to 41.1) | 12.0 (4.6 to 19.3) | 58.9 (49.4 to 68.4) |

| 2013 | 35.1 (27.5 to 42.7) | 19.1 (12.1 to 26.0) | 33.0 (24.5 to 41.6) | 12.8 (6.6 to 19.0) | 64.9 (57.3 to 72.5) |

| 2015 | 22.9 (18.0 to 27.9) | 23.3 (15.5 to 31.1) | 48.1 (41.1 to 55.1) | 5.6 (2.9 to 8.3) | 77.1 (72.1 to 82.0) |

| 2017 | 26.4 (20.2 to 32.6) | 13.8 (7.2 to 20.4) | 43.7 (36.0 to 51.4) | 16.0 (8.5 to 23.5) | 73.6 (67.4 to 79.8) |

| Sexually active adolescents with only opposite-sex sexual contact (N = 18 455) | |||||

| 2009 | 97.9 (97.4 to 98.5) | 0.1 (<0.1 to 0.3) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.0) | 0.5 (0.1 to 0.8) | 2.1 (1.5 to 2.6) |

| 2011 | 96.8 (95.7 to 98.0) | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.8) | 1.6 (1.0 to 2.3) | 1.1 (0.3 to 1.8) | 3.2 (2.0 to 4.3) |

| 2013 | 95.4 (94.3 to 96.7) | 0.8 (0.2 to 1.3) | 2.0 (1.3 to 2.7) | 1.8 (1.0 to 2.6) | 4.6 (3.4 to 5.7) |

| 2015 | 95.6 (94.2 to 96.9) | 0.2 (<0.1 to 0.5) | 3.1 (1.8 to 4.4) | 1.0 (0.4 to 1.6) | 4.4 (3.1 to 5.7) |

| 2017 | 95.2 (94.0 to 96.5) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.1) | 2.5 (1.9 to 3.2) | 1.5 (0.5 to 2.5) | 4.8 (3.5 to 6.0) |

Sample C: alignment of sexual orientation identity and sex of sexual contacts among adolescents from 3 states with data on sexual orientation identity and sex of sexual contacts, 2009–2017.

TABLE 7.

Regression Analyses of Changes in Reported Sexual Orientation Identity and Sex of Sexual Partners of Adolescents From 3 States Per Year: 2009–2017

| Sexual Orientation Identity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterosexual | Gay or Lesbian | Bisexual | Not Sure | Any Sexual Minority (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, or Not Sure) | |

| Point Estimate (95% CI) | Point Estimate (95% CI) | Point Estimate (95% CI) | Point Estimate (95% CI) | Point Estimate (95% CI) | |

| All sexually active adolescents (N = 20 655) | |||||

| aOR | 0.90* (0.87 to 0.93) | 1.10* (1.04 to 1.17) | 1.12* (1.08 to 1.16) | 1.09* (1.02 to 1.16) | 1.11* (1.08 to 1.15) |

| pp | −0.84* (−1.07 to −0.61) | 0.18* (0.06 to 0.30) | 0.45* (0.29 to 0.60) | 0.16* (0.05 to 0.27) | 0.84* (0.61 to 1.07) |

| Sexually active adolescents with any same-sex sexual contact (N = 2200) | |||||

| aOR | 0.89* (0.84 to 0.96) | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.12) | 1.09* (1.03 to 1.15) | 1.00 (0.89 to 1.13) | 1.12* (1.05 to 1.14) |

| pp | −2.42* (−3.88 to −0.97) | 0.45 (−0.53 to 1.44) | 2.01* (0.73 to 3.30) | 0.02 (−1.14 to 1.19) | 2.42* (0.94 to 3.92) |

| Sexually active adolescents with only opposite-sex sexual contact (N = 18 455) | |||||

| aOR | 0.91* (0.88 to 0.95) | 1.10 (1.00 to 1.21) | 1.09* (1.03 to 1.15) | 1.09** (1.00 to 1.19) | 1.09* (1.05 to 1.14) |

| pp | −0.28* (−0.42 to −0.14) | 0.03** (<0.01 to 0.07) | 0.13* (0.04 to 0.22) | 0.09** (0.01 to 0.16) | 0.28 (0.13 to 0.43) |

Sample C: adolescents from 3 states with data on sexual orientation identity and sex of sexual contacts, 2009–2017. aOR is per year; pp are per year and calculated by using MEs at the means of covariates. Estimates are adjusted for the age, race and/or ethnicity, and sex categories described in Table 1.

P < .01

P < .05

Among sample C adolescents with only opposite-sex sexual contact, there was a smaller decline in the proportion of adolescents who reported identifying as heterosexual from 97.9% in 2009 to 95.2% in 2017 (ME: −0.28 pp per year; 95% CI: −0.42 to −0.14 pp; Fig 1D, Table 7). The proportion of adolescents reporting only opposite-sex sexual contacts who reported identifying as gay or lesbian increased from 0.1% in 2009 to 0.7% in 2017 (ME: 0.03 pp per year; 95% CI: <0.01 to 0.07). The proportion of adolescents reporting they were bisexual increased from 1.5% in 2009 to 2.5% in 2017 (ME: 0.13 pp per year; 95% CI: 0.04 to 0.22 pp), and the proportion reporting they were not sure of their sexual orientation identity increased from 0.5% in 2009 to 1.5% in 2017 (ME: 0.09 pp per year; 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.16 pp).

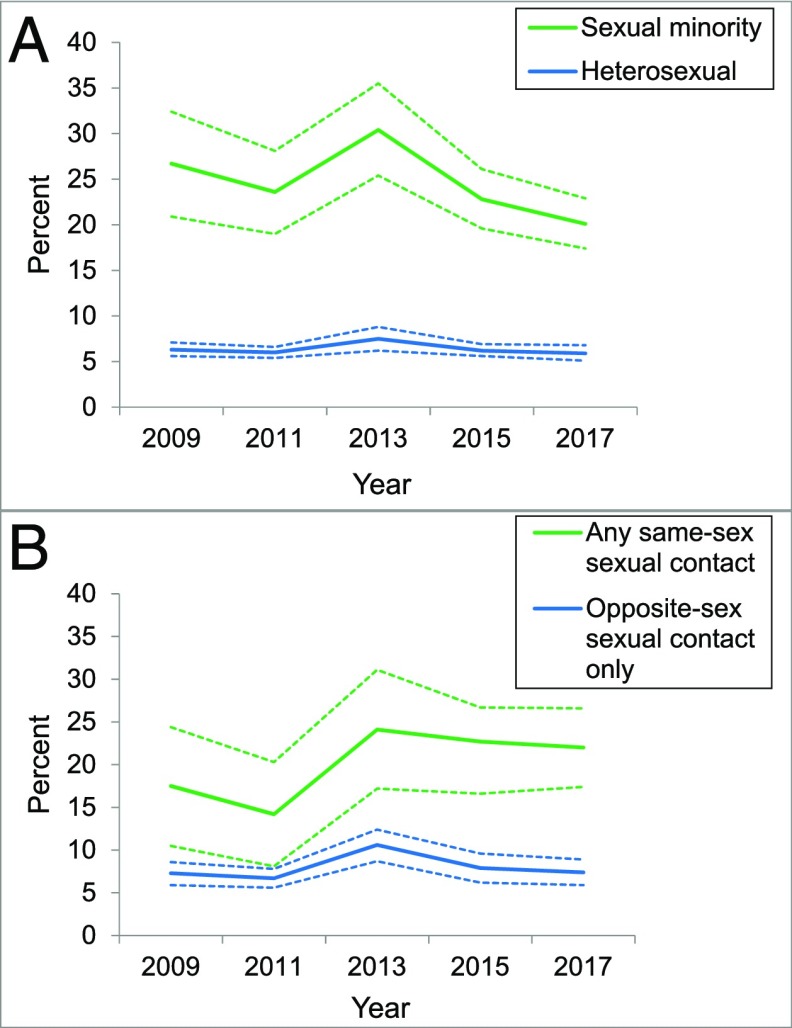

In 2017, suicide attempts remained elevated for sexual minority relative to heterosexual students on the basis of both orientation identity (ME: 12.6 pp; 95% CI: 10.0 to 15.1 pp; Fig 2A, Table 8) and the sex of sexual contacts (ME: 9.1 pp; 95% CI: 7.2 to 11.1 pp). Over time, there was a decline in suicide attempts among students with sexual minority identities (ME: −0.8 pp per year; 95% CI: −1.4 to −0.2), whereas suicide attempts among heterosexual students did not change (ME: −0.04 pp per year; 95% CI: −0.2 to 0.1 pp). There were also no changes in suicide attempts over time among students with same-sex sexual contacts (s (ME: 0.7 pp per year; 95% CI: −0.2 to 1.7 pp; Fig 2B, Table 9) or opposite-sex sexual contacts (ME: 0.09 pp per year; 95% CI: −0.2 to 0.3 pp). The same patterns were observed for each sex, although the declines in suicide attempts were not significant in the sex-specific analyses among students with sexual minority identities.

FIGURE 2.

Changes in the proportion of adolescents reporting ≥1 suicide attempt over time, by sexual orientation identity and sex of sexual contacts. A, Suicide attempts by sexual orientation identity. B, Suicide attempts by sex of sexual contacts.

TABLE 8.

Percent of Adolescents Who Reported a Suicide Attempt in the Past Year by Sexual Orientation Identity, 2009–2017

| Sexual Orientation Identity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide Attempts Among Adolescents With Sexual Minority Identity | Suicide Attempts Among Adolescents With Heterosexual Identity | Suicide Attempts Among Sexual Minority Relative to Heterosexual Adolescents | Suicide Attempts Among Sexual Minority Relative to Heterosexual Adolescents | |

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | pp (95% CI) | |

| Total | ||||

| 2009 | 26.7 (20.9 to 32.4) | 6.3 (5.6 to 7.1) | 5.2* (3.8 to 7.1) | 18.9 (13.2 to 24.5) |

| 2011 | 23.6 (19.0 to 28.1) | 6.0 (5.4 to 6.6) | 4.6* (3.5 to 6.1) | 16.2 (11.8 to 20.7) |

| 2013 | 30.4 (25.4 to 35.5) | 7.5 (6.2 to 8.8) | 4.9* (3.6 to 6.6) | 19.9 (14.7 to 25.1) |

| 2015 | 22.8 (19.6 to 26.1) | 6.2 (5.6 to 6.9) | 4.2* (3.5 to 5.1) | 15.2 (12.2 to 18.3) |

| 2017 | 20.1 (17.4 to 22.9) | 5.9 (5.1 to 6.8) | 3.8* (3.0 to 4.6) | 12.6 (10.0 to 15.1) |

| Female students | ||||

| 2009 | 24.4 (19.4 to 29.5) | 6.3 (5.5 to 7.1) | 4.7* (3.4 to 6.5) | 9.5* (7.4 to 11.7) |

| 2011 | 25.7 (19.3 to 32.0) | 6.5 (5.8 to 7.2) | 4.9* (3.4 to 7.2) | 10.9* (8.4 to 13.4) |

| 2013 | 31.6 (26.2 to 36.9) | 8.7 (6.8 to 10.6) | 4.7* (3.3 to 6.9) | 13.6* (11.0 to 16.1) |

| 2015 | 23.4 (17.9 to 29.0) | 6.2 (5.2 to 7.3) | 4.2* (3.0 to 5.8) | 9.4* (7.2 to 11.7) |

| 2017 | 21.5 (17.8 to 25.2) | 6.8 (5.6 to 8.0) | 3.8* (3.0 to 4.7) | 9.8* (7.9 to 11.6) |

| Male students | ||||

| 2009 | 30.9 (18.8 to 42.9) | 6.4 (5.3 to 7.5) | 6.1* (3.5 to 10.6) | 11.0* (7.5 to 14.5) |

| 2011 | 19.4 (13.8 to 24.9) | 5.5 (4.5 to 6.4) | 4.1* (2.8 to 6.1) | 7.4* (5.0 to 9.7) |

| 2013 | 28.5 (20.1 to 36.8) | 6.4 (4.9 to 7.9) | 5.2* (3.3 to 8.2) | 10.3* (7.3 to 13.3) |

| 2015 | 21.8 (15.2 to 28.5) | 6.2 (5.1 to 7.3) | 4.1* (2.8 to 6.2) | 8.5* (5.9 to 11.0) |

| 2017 | 16.9 (10.8 to 23.0) | 5.1 (4.2 to 6.0) | 3.7* (2.3 to 5.8) | 6.3* (2.9 to 8.6) |

Sample A: adolescents from 6 states with data on sexual orientation identity, 2009–2017. The pp are based on the MEs of sexual minority identity or any same-sex sexual contacts relative to heterosexual orientation identity or opposite-sex-only sexual contacts. Estimates are adjusted for the age, race and/or ethnicity, and sex categories described in Table 1.

P < .01

TABLE 9.

Percent of Adolescents Who Reported a Suicide Attempt in the Past Year by Sex of Sexual Contacts, 2009–2017

| Sex of Sexual Contacts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide Attempts Among Adolescents With Any Same-Sex Sexual Contact | Suicide Attempts Among Adolescents With Opposite-Sex Only | Suicide Attempts Among Adolescents With Same-Sex Relative to Opposite-Sex Sexual Contacts | Suicide Attempts Among Adolescents With Same-Sex Relative to Opposite-Sex Sexual Contacts | |

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | pp (95% CI) | |

| Total | ||||

| 2009 | 17.5 (10.5 to 24.4) | 7.3 (5.9 to 8.6) | 2.6* (1.3 to 4.9) | 6.1* (1.8 to 10.5) |

| 2011 | 14.2 (8.1 to 20.3) | 6.7 (5.6 to 7.8) | 2.2* (1.2 to 4.0) | 5.0* (1.5 to 8.5) |

| 2013 | 24.1 (17.2 to 31.1) | 10.6 (8.7 to 12.4) | 2.5* (1.6 to 3.7) | 8.7* (4.9 to 12.5) |

| 2015 | 22.7 (16.6 to 26.7) | 7.9 (6.2 to 9.6) | 2.9* (2.0 to 4.1) | 8.1* (5.5 to 10.7) |

| 2017 | 22.0 (17.4 to 26.6) | 7.4 (5.9 to 8.9) | 3.3* (2.4 to 4.6) | 9.1* (7.2 to 11.1) |

| Female students | ||||

| 2009 | 15.4 (6.1 to 24.7) | 7.4 (5.0 to 9.7) | 2.3 (0.8 to 6.3) | 4.9 (−1.4 to 11.1) |

| 2011 | 14.6 (5.3 to 24.0) | 7.9 (6.4 to 9.5) | 2.1 (0.9 to 4.8) | 5.3 (−0.8 to 11.5) |

| 2013 | 24.3 (16.8 to 31.8) | 12.2 (9.8 to 14.5) | 2.3* (1.6 to 3.4) | 8.9* (4.6 to 13.2) |

| 2015 | 22.8 (14.6 to 31.1) | 8.2 (4.9 to 11.5) | 2.4* (1.6 to 3.7) | 6.5* (3.7 to 9.2) |

| 2017 | 23.2 (16.1 to 30.3) | 8.2 (5.7 to 10.8) | 3.4* (2.4 to 4.8) | 10.2* (6.9 to 13.5) |

| Male students | ||||

| 2009 | 22.1 (8.2 to 35.9) | 7.2 (5.0 to 9.3) | 3.4* (1.3 to 8.6) | 7.5* (1.3 to 13.6) |

| 2011 | 13.2 (5.8 to 20.6) | 5.6 (4.1 to 7.1) | 2.6* (1.2 to 5.7) | 4.9* (1.0 to 8.8) |

| 2013 | 23.8 (13.2 to 34.5) | 9.3 (6.9 to 11.6) | 2.9* (1.4 to 6.0) | 9.2* (3.6 to 14.8) |

| 2015 | 19.7 (9.9 to 29.5) | 7.7 (5.4 to 9.9) | 2.9* (1.6 to 5.5) | 7.8* (2.9 to 12.8) |

| 2017 | 19.2 (11.2 to 27.2) | 6.6 (4.9 to 8.4) | 3.2* (1.7 to 5.9) | 7.7* (3.9 to 11.4) |

Sample B: sexually active adolescents from 4 states with data on sex of sexual contacts and sexual assault, 2009–2017. The pp are based on the MEs of sexual minority identity or any same-sex sexual contacts relative to heterosexual orientation identity or opposite-sex-only sexual contacts. Estimates are adjusted for the age, race and/or ethnicity, and sex categories described in Table 1.

P < .01.

Sexual minority adolescents accounted for an increasing proportion of suicide attempts (Supplemental Tables 10 and 11). Among adolescents who attempted suicide, the proportion who were of sexual minority orientation increased from 24.6% (95% CI: 20.1% to 29.2%) in 2009 to 35.6% (95% CI: 31.31% to 39.93%) in 2017. Among sexually active adolescents who attempted suicide, the proportion who had same-sex sexual contacts increased from 15.8% (95% CI: 9.3% to 22.4%) in 2009 to 30.3% (95% CI: 24.0% to 36.7%) in 2017.

Discussion

In a large, multistate sample of high school students in states that continuously collected sexual orientation data in the YRBSS, the proportion of adolescents who reported identifying as gay or lesbian, bisexual, or not sure of their sexual identity increased 96% between 2009 and 2017. The proportion of sexually active adolescents who reported consensual same-sex sexual contact also increased by 70% between 2009 and 2017. Increases in reported sexual minority orientation and same-sex sexual contacts could reflect either increased comfort with reporting or underlying population changes in sexual orientation. The observed increases in the proportion of the population reporting being sexual minorities are consistent with evidence from US adolescents19 and from British adults.18

Although suicide attempts declined over time among students identifying as sexual minorities, suicide attempts remained elevated among sexual minorities compared with heterosexual students. In 2017, students identifying as sexual minorities were >3 times as likely to attempt suicide relative to heterosexual students. Students with same-sex sexual contacts were more than twice as likely to report suicide attempts relative to those with only opposite-sex sexual contacts. With sexual minorities accounting for a growing proportion of the population and suicide attempt disparities persisting, sexual minority adolescents accounted for a growing proportion of all adolescent suicide attempts. Policies and interventions that address suicide attempts among sexual minority adolescents are critical, particularly given that suicide is the second leading cause of death among adolescents24 and is increasing over time.21

Policies and institutions play important roles in shaping mental health disparities.5,6 With increasing numbers of national and state policies restricting sexual minority rights and linked to worse mental health,11,25,26 sexual minority mental health disparities may grow. At the same time, policies around nondiscrimination, antibullying, and inclusive education policies may support sexual minority health.27

Health and educational institutions can also play an important role in reducing mental health disparities. Whereas most health care providers currently have little or no training in caring for sexual minority populations,28 medical and nursing schools can ensure that they train health care providers to provide culturally competent care that addresses sexual minority mental and sexual health disparities.29 School environments that are supportive of sexual minorities are also associated with improved sexual minority adolescent mental health.30,31

A strength of the study is that we used data representative of adolescents in each state. Whereas authors of a previous study on sexual orientation over time also used YRBSS data,19 our approach of only including states that collected sexual orientation data continuously throughout the study period allowed us to evaluate changes in sexual orientation in the same population over time. At the same time, the number of included states was small and represented only the northeast, mid-Atlantic, and Midwest, meaning the results may only be generalizable to these regions. We did not have data from states in the southeast, southwest, or northwest, and results are not representative of the entire country. The limited amount of data on sexual orientation available for this study highlights the importance of collecting sexual orientation data in the YRBSS and other population surveys. We also excluded adolescents who reported any sexual assault from the analyses involving sex of sexual contacts because we were unable to determine if sexual contacts were consensual. The YRBSS excludes youth absent from school; given evidence of the associations between sexual orientation and sexual assault2 and homelessness32 and between sexual assault and homelessness with suicide,33,34 this analysis may underestimate disparities in suicide attempts by sexual orientation. The YRBSS does not include questions on the attraction dimension of sexual orientation or on gender identity. We were unable to determine to what extent increases in sexual orientation identity and sex of sexual contact reflect changes in underlying identity and behaviors or changes in reporting.

Conclusions

The proportion of adolescents identifying as sexual minorities increased 96% and the proportion with consensual same-sex sexual partners increased 70% between 2009 and 2017. Disparities in suicide attempts by sexual orientation persisted in 2017. Sexual minority adolescents account for a growing proportion of adolescent suicide attempts. There is a need for further research on national, state, and local policies that reduce sexual minority adolescent suicide attempts and promote sexual minority health. There is also a need for further research on policies, training practices, and interventions to promote sexual minority health in education and health care institutions.

Acknowledgments

We thank the CDC, the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, and the Connecticut Department of Public Health for providing state YRBSS data used in this study.

Glossary

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI

confidence interval

- ME

marginal effect

- pp

percentage point

- YRBSS

Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance Survey

Footnotes

Dr Raifman conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Charlton, Arrington-Sanders, Chan, Rusley, Mayer, Stein, Austin, and McConnell contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Funded by National Institutes of Health grants K01MH116817 and R25MH083620. The funder played no role in the study design; in data collection, analysis, or interpretation; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPERS: Companions to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2019-2221 and www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2019-4002.

References

- 1.Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, et al. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1630–1640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kann L. Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9-12 - United States and selected sites, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(9):1–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hess KL, Hu X, Lansky A, Mermin J, Hall HI. Lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(4):238–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report 2016. Vol 28 Atlanta, GA: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2016-vol-28.pdf. Accessed January 17, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma and the health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23(2):127–132 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):813–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pew Research Center Changing attitudes on same-sex marriage. 2019. Available at: https://www.pewforum.org/fact-sheet/changing-attitudes-on-gay-marriage/ Accessed January 2, 2020

- 8.Raifman J, Moscoe E, Austin SB, McConnell M. Difference-in-differences analysis of the association between state same-sex marriage policies and adolescent suicide attempts. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(4):350–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatzenbuehler ML, O’Cleirigh C, Grasso C, Mayer K, Safren S, Bradford J. Effect of same-sex marriage laws on health care use and expenditures in sexual minority men: a quasi-natural experiment. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(2):285–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Supreme Court of the United States. Opinion of the court: Obergefell et al. v. Hodges, Director, Ohio Department of Health, et al. Available at: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/14pdf/14-556_3204.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2016

- 11.Raifman J, Moscoe E, Austin SB, Hatzenbuehler ML, Galea S. Association of state laws permitting denial of services to same-sex couples with mental distress in sexual minority adults: a difference-in-difference-in-differences analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(7):671–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mason E, Williams A, Elliott K. The dramatic rise in state efforts to limit LGBT rights. Washington Post. June 10, 2016. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/national/lgbt-legislation/?utm_term=.f59c77ee8edd. 2017. Accessed July 8, 2017.

- 13.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Predicting different patterns of sexual identity development over time among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: a cluster analytic approach. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;42(3–4):266–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ott MQ, Corliss HL, Wypij D, Rosario M, Austin SB. Stability and change in self-reported sexual orientation identity in young people: application of mobility metrics. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(3):519–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman RC. Male Homosexuality: A Contemporary Psychoanalytic Perspective. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coffman KB, Coffman LC, Ericson KMM. The size of the LGBT population and the magnitude of anti-gay sentiment are substantially underestimated. Manag Sci. 2016;63(10):3168–3186 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlton BM, Corliss HL, Spiegelman D, Williams K, Austin SB. Changes in reported sexual orientation following US states recognition of same-sex couples. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(12):2202–2204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mercer CH, Tanton C, Prah P, et al. Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain through the life course and over time: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet. 2013;382(9907):1781–1794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips G II, Beach LB, Turner B, et al. Sexual identity and behavior among U.S. high school students, 2005-2015 [published correction appears in Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48(5):1481]. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48(5):1463–147931123950 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Combining YRBS Data Across Years and Sites. Atlanta, GA: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2015/2015_yrbs_combining_data.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stone DM, Simon TR, Fowler KA, et al. Vital signs: trends in state suicide rates - United States, 1999-2016 and circumstances contributing to suicide - 27 states, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(22):617–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brener ND, Kann L, Shanklin S, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System–2013. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62(RR):1–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(8):1–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 10 Leading Causes of Death by Age Group, United States - 2016. Atlanta, GA: National Center FOR Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/images/lc-charts/leading_causes_of_death_age_group_2016_1056w814h.gif [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: a prospective study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):452–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raifman J. Sanctioned stigma in health care settings and harm to LGBT youth. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(8):713–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. Inclusive anti-bullying policies and reduced risk of suicide attempts in lesbian and gay youth. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(suppl 1):S21–S26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 2011;306(9):971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez NF, Rabatin J, Sanchez JP, Hubbard S, Kalet A. Medical students’ ability to care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered patients. Fam Med. 2006;38(1):21–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coulter RW, Birkett M, Corliss HL, Hatzenbuehler ML, Mustanski B, Stall RD. Associations between LGBTQ-affirmative school climate and adolescent drinking behaviors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:340–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poteat VP, Sinclair KO, DiGiovanni CD, Koenig BW, Russell ST. Gay–Straight Alliances are associated with student health: a multischool comparison of LGBTQ and heterosexual youth. J Res Adolesc. 2013;23(2):319–330 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corliss HL, Goodenow CS, Nichols L, Austin SB. High burden of homelessness among sexual-minority adolescents: findings from a representative Massachusetts high school sample. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(9):1683–1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomasula JL, Anderson LM, Littleton HL, Riley-Tillman TC. The association between sexual assault and suicidal activity in a national sample. Sch Psychol Q. 2012;27(2):109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edidin JP, Ganim Z, Hunter SJ, Karnik NS. The mental and physical health of homeless youth: a literature review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012;43(3):354–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]