ABSTRACT

Mucopolysaccharidosis type I (MPS I or Hurler syndrome) is a multisystem genetic disorder caused by α-L-iduronidase (IDUA) deficiency, which leads to widespread accumulation of glycosaminoglycans triggering tissue damage and organ dysfunction. A variety of ocular manifestations have been described in Hurler Syndrome. We present the case of an 11-year-old boy with Hurler Syndrome and optic disc edema related to ocular glycosaminoglycan deposition. This report advances the idea that the optic nerve swelling seen in MPS I is likely influenced as much by biomechanical changes at the optic nerve head as by increased intracranial pressure.

KEYWORDS: Mucopolysaccharidosis type I, optic disc edema, Bruch’s membrane, increased intracranial pressure

Introduction

Mucopolysaccharidosis type I (MPS I or Hurler syndrome) is a multisystem genetic disorder caused by α-L-iduronidase (IDUA) deficiency, which leads to widespread accumulation of glycosaminoglycans triggering tissue damage and organ dysfunction. Symptoms mostly start in the first year of life and include upper airway obstruction, laryngeal and tracheal narrowing, hearing and visual deficits, skeletal deformities, organomegaly, abdominal herniae, and progressive neurological disease with severe cognitive delay.1 A variety of ocular manifestations have been described in Hurler Syndrome including decreased visual acuity and high hyperopia,2 abnormal corneal hysteresis,3 and optic nerve head swelling and optic atrophy.4 Other mucopolysaccharidoses have ocular manifestations as well including diffuse fine corneal deposits, pigmentary retinal degeneration, pseudopapilledema, and macular-edema.5 The authors present the case of an 11-year-old boy with Hurler Syndrome and optic disc edema related to ocular glycosaminoglycan deposition.

Case report

An 11-year-boy with genetically-proven Hurler Syndrome on laronidase presented with bilateral optic disc edema that was discovered during the workup of new-onset headaches. His BMI was 20.52, and he denied diplopia, transient visual obscurations, and pulse synchronous tinnitus. Brain MRI revealed optic nerve head protrusion into the globes bilaterally, and lumbar puncture demonstrated an opening pressure of 32 cm H20. He was treated with acetazolamide and topiramate without improvement in his symptoms, so a ventriculoperitoneal shunt was placed. Shunt placement resulted in nearly immediate resolution of his headaches. Two years later, however, he continued to have bilateral optic disc edema despite a functioning shunt and a lack of symptoms of increased intracranial pressure. He presented for neuro-ophthalmic evaluation of persistent optic disc edema.

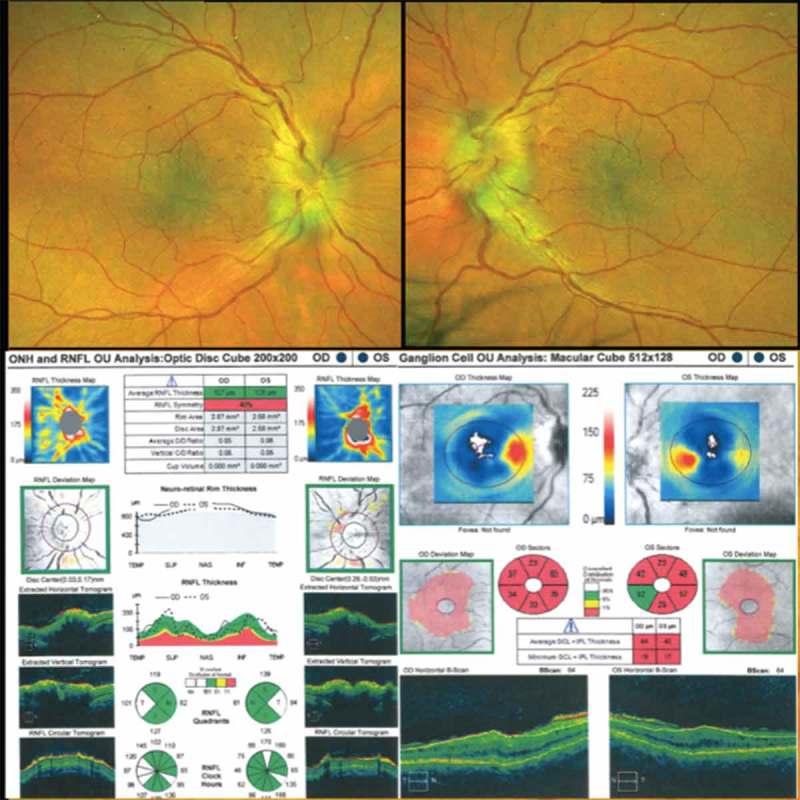

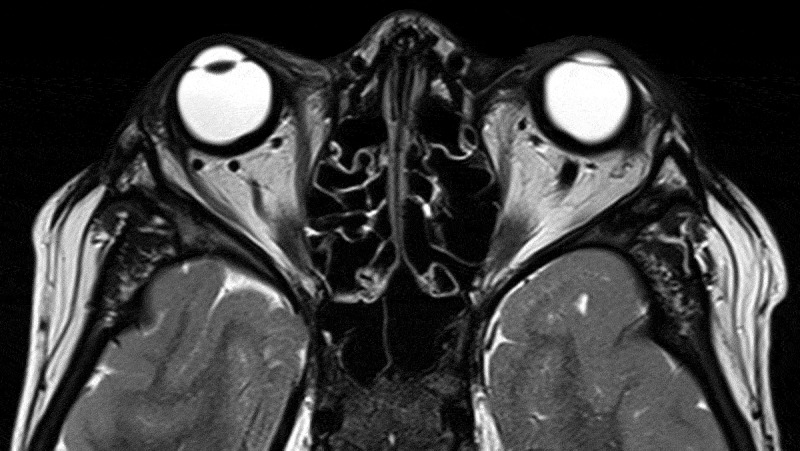

On examination his best-corrected visual acuity was 20/50+ right eye and 20/40 left eye with normal color vision testing. His intraocular pressures by applanation were 17 mmHG bilaterally. Automated perimetry revealed a superonasal defect in the right eye and superior and inferior nerve fiber layers defects in the left eye. Dilated fundoscopic exam showed bilateral optic disc edema and retinal folds in a radial orientation around the maculae bilaterally. Optical coherence tomography of the maculae showed thickening, scattered fluid, chorioretinal folds, and loss of the foveal contour bilaterally (Figure 1). MRI scan showed marked thickening of the posterior globes (Figure 2). He was observed clinically without any deterioration of his vision or changes in his optic disc structure.

Figure 1.

Dilated fundoscopic exam showing bilateral optic disc edema and retinal folds in a radial orientation around the maculae in the right and left eyes. OCT of the retinal nerve fiber layer showing bilateral optic disc edema and of the maculae showing thickening, scattered fluid, and loss of the foveal contour bilaterally.

Figure 2.

T2 axial MRI scan showing marked thickening of the posterior globes.

His history, examination, and testing were judged to be most consistent with resolved increased intracranial pressure, but persistent optic disc edema due to local ocular factors. Historically, he had immediate resolution of headaches on shunt implantation; these headaches did not recur. On examination, his optic disc edema did not change substantially over two years, which would be unusual in a dynamic process such as increased intracranial pressure. Additionally, he had substantial macular changes and a hyperopic shift, which were out of proportion to his optic disc edema and pointed towards a local process. Finally, his MRI scan shows thickening of the posterior globes bilaterally, which in the context of Hurler Syndrome is highly suggestive of glycosaminoglycan deposition.

Discussion

MPS I can trigger tissue damage and dysfunction in many different organ systems including the eye. Ocular manifestations are very common. They can affect all parts of the eye,6 and can cause significant visual loss.7 Systemic treatments such as enzyme replacement therapy can increase life expectancy for MPS I patients, yet these same treatments may not prevent progression of ocular changes,8 thus it is important for ophthalmologists to have an understanding of the ocular manifestations of MPS I.

In a case series of MPS I patients, over half had optic disc edema.4 Another sonographic series found deformation and elevation of the optic nerve head, an increased diameter of the optic nerve and its sheath, and scleral thickening to be the major morphological changes observed in patients with MPS I.9 The mechanisms underlying these optic nerve changes are not always clear. Increased intracranial pressure may be the primary driver in some cases, but local tissue changes may also play a role. The patient presented here, as in the series by Schumacher, had significant scleral thickening due to deposition of glycosaminoglycans. Our patient’s scleral thickening is evident on his MRI scan (Figure 2), and seqeulae of the thickened sclera are seen in the macular changes and hyperopic shift. Such changes can be expected to alter the properties of the tissues at the optic nerve head, including their compliance and the diameter of Bruch’s membrane opening. Less compliance and a smaller Bruch’s membrane opening would cause impaired axoplasmic flow, optic disc edema, and retinal folds as seen in this patient. We suspect that our patient’s mildly impaired best-corrected visual acuity results from macular changes as opposed to optic neuropathy based on the appearance of the maculae as well as on his relatively spared color vision.

This case demonstrates an important ocular manifestation of MPS I. It advances the idea that the optic nerve swelling seen in MPS I is likely influenced as much by biomechanical changes at the optic nerve head as by increased intracranial pressure.

Funding Statement

None.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

- 1.Neufeld EF, Muenzer J.. The Mucopolysaccaridoses In: Scriver C, Beaudet A, Sly W, Valle D, eds. The Metabolic and Nolecular Basis of Inherited Disease. New York: Mc Graw Hill; 2001:3421–3452. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fahnehjelm KT, Tornquist AL, Malm G, Winiarski J. Ocular findings in four children with mucopolysaccharidosis I-Hurler (MPS I-H) treated early with haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84(6):781–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2006.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fahnehjelm KT, Chen E, Winiarski J. Corneal hysteresis in mucopolysaccharidosis I and VI. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90(5):445–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins ML, Traboulsi E, Maumenee IH. Optic nerve head swelling and optic atrophy in the systemic mucopolysaccharidoses. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1445–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Usui T, Shirakashi M, Takagi M, Abe H, Iwata K. Macular edema-like change and pseudopapilledema in a case of Scheie syndrome. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1991;11(3):183–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenzl CR, Teramoto K, Moshirfar M. Ocular manifestations and management recommendations of lysosomal storage disorders I: mucopolysaccharidoses. Clin Ophthalmol (Auckland, NZ). 2015;9:1633–1644. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S78368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashworth JL, Biswas S, Wraith E, Lloyd IC. The ocular features of the mucopolysaccharidoses. Eye. 2006a;20:553–563. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitz S, Ogun O, Bajbouj M, Arash L, Schulze-Frenking G, Beck M. Ocular changes in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis I receiving enzyme replacement therapy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(10):1353–1356. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.10.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schumacher RG, Brzezinska R, Schulze-Frenking G, Pitz S. . Sonographic ocular findings in patients with mucopolysaccharidoses I, II and VI. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38(5):543–550. doi: 10.1007/s00247-008-0788-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]