Key Points

Question

Are age-standardized suicide mortality ratios (SMRs) for male and female physicians high worldwide after 1980, and did they decrease from before to after 1980?

Findings

In a meta-analysis of 9 studies and databases, female physicians’ SMRs were high, while male physicians’ SMRs were significantly lower since 1980, and both SMRs decreased over time. A systematic review showed increased risk associated with male sex, relationship difficulties, youthful or elderly age ranges, and especially career difficulties; suicide methods were by poisoning, firearms, and asphyxiation.

Meaning

More research is critical to address modifiable risks of physician suicide and understand what causes vulnerability in physician subpopulations.

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluates male and female physician suicide risks compared with the general population from 1980 to date and tests whether there is a reduction of the standardized mortality ratio in cohorts after 1980 compared with before 1980.

Abstract

Importance

Population-based findings on physician suicide are of great relevance because this is an important and understudied topic.

Objective

To evaluate male and female physician suicide risks compared with the general population from 1980 to date and test whether there is a reduction of SMR in cohorts after 1980 compared with before 1980 via a meta-analysis, modeling studies, and a systematic review emphasizing physician suicide risk factors.

Data Sources

This study uses studies retrieved from PubMed, Scielo, PsycINFO, and Lilacs for human studies published by October 3, 2019, using the search term “(((suicide) OR (self-harm) OR (suicidality)) AND ((physicians) OR (doctors))).” Databases were also searched from countries listed in articles selected for review. Data were also extracted from an existing article by other authors to facilitate comparisons of the pre-1980 suicide rate with the post-1980 changes.

Study Selection

Original articles assessing male and/or female physician suicide were included; for the meta-analysis, only cohorts from 1980 to the present were included.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The preregistered systematic review and meta-analysis followed Cochrane, PRISMA, and MOOSE guidelines. Data were extracted into standardized tables per a prespecified structured checklist, and quality scores were added. Heterogeneity was tested via Q test, I2, and τ2. For pooled effect estimates, we used random-effects models. The Begg and Egger tests, sensitivity analyses, and meta-regression were performed. Proportional mortality ratios were presented when SMR data could not be extracted.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Suicide SMRs for male and female physicians from 1980 to the present and changes over time (before and after 1980).

Results

Of 7877 search results, 32 articles were included in the systematic review and 9 articles and data sets in the meta-analysis. Meta-analysis showed a significantly higher suicide SMR in female physicians compared with women in general (1.46 [95% CI, 1.02-1.91]) and a significantly lower suicide SMR in male physicians compared with men in general (0.67 [95% CI, 0.55-0.79]). Male and female physician SMRs significantly decreased after 1980 vs before 1980 (male physicians: SMR, −0.84 [95% CI, −1.26 to −0.42]; P < .001; female physicians: SMR, −1.96 [95% CI, −3.09 to −0.84]; P = .002). No evidence of publication bias was found.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, suicide SMR was found to be high in female physicians and low in male physicians since 1980 but also to have decreased over time in both groups. Physician suicides are multifactorial, and further research into these factors is critical.

Introduction

Suicide leads to more annual deaths globally than natural disasters, violence inflicted by others, war, and conflict combined.1,2 Suicide caused almost 800 000 deaths worldwide in 2016, down from nearly 850 000 suicide deaths in 2004.1,2 In 2016, the age-standardized suicide rates were 10.53 per 100 000 persons globally.1,2 Crude suicide rates for both men and women decreased between 2000 and 2016 in Europe and all World Health Organization regions other than the Americas.1,2 In the United States, age-standardized suicide rates rose for both men and women over the same period, reaching 21.1 and 6.4 deaths per 100 000 persons, respectively.1,2

Suicide risk factors are male sex (for completed suicides),3,4 younger age, fewer years of formal education, unmarried status, and the presence of mental disorders.5,6,7 Occupational hazards are also associated with suicide risk8,9,10; physicians typically have higher suicide rates than the general population, including the military.9 Overall, age-standardized suicide mortality ratios (SMRs) for physicians were significantly higher (ie, higher suicide rates in physicians compared with the general population) according to a meta-analysis, including much higher findings for female physicians and moderately higher findings for male physicians.11 However, heterogeneity was considerable for the meta-analysis overall, and data quality was higher for the suicides of male physicians, possibly because the data ranged from 1910 to 1998 and multiple articles had no data on female physicians.

Meanwhile, from 1980 to 2015, the proportion of female US medical school graduates increased from 23.3% to 47.6%,12 but female participants in the US civilian labor force rose only from 42.5% to 46.8%.13 This implies that gender dynamics in medicine changed much more rapidly than in the general population during this period, which may have affected female and male physicians’ SMRs. However, many additional cultural, socioeconomic, and political changes influenced health care during this period,14,15 reinforcing the need for action regarding physician suicides.

As to the general population, the rates of college and university graduation (a protective factor against suicide) are increasing among women but decreasing among men.16 Additionally, unemployment, which affects suicide risk among men more than women,17 has been increasing worldwide.18 Even among individuals who are employed, suicide rates are highest among working-class men.19 These factors are consistent with increasing suicide rates among men in general, which are less likely to affect physicians in recent times.

In light of the literature, we hypothesized a higher risk of male and female physician suicide compared with the general population from the 1980s to date; we also hypothesized that the suicide rate ratio of both female and male physicians seen before 1980 would be reduced after 1980.11 In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aimed to answer the following research questions: are age-standardized suicide SMRs for male and female physicians high worldwide after 1980, and did they decrease after 1980 compared with before 1980?

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with recommendations of the Cochrane group, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement,20 and the Meta-analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Checklist (MOOSE)21 guidelines. The study is registered at the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (CRD42019124985).

Literature Search

We used Boolean operators on PubMed, Scielo, PsycINFO, and Lilacs for human research studies published from database inception to October 3, 2019, using the following keywords: “(((suicide) OR (self-harm) OR (suicidality)) AND ((physicians) OR (doctors)).” In PubMed, the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) term suicide was combined with the MeSH term physicians. Additionally, we largely followed the methods used by Schernhammer and Colditz11 to make our meta-analysis comparable with that study (eMethods 1 in the Supplement). We also searched for databases from the countries listed in the articles selected for review, including the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the US National Outcomes Measurement System, and the UK Office of National Statistics (ONS) (eMethods 1 in the Supplement).

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria were original articles in English, Portuguese, Spanish, or French that assessed male and/or female physician suicide as an outcome. For the meta-analysis, we included only cohort periods from 1980 to the present. We also allowed for up to 1 year of data prior to 1980.

Exclusion criteria included studies lacking abstracts; nonoriginal articles; studies missing completed suicide data; studies without physicians’ suicide data or with only physicians of some medical specialties included; and articles covering similar periods plus or minus 2 years, if the source material was exactly the same, but not if additional source material was used (eg, an additional database or different US states).

For the meta-analysis, we excluded articles that did not compare male and female physician age-standardized suicide rates with the general population (observed/expected suicide rates), if this information could not be calculated from relevant sources (ie, the databases listed). We also excluded studies where cohort data could not be extracted from 1980 and after and studies with a substantial overlap (of 2 or more years) that used the same source material.

Data Extraction

After excluding ineligible records, 4 authors (D.D., M.M.E., W.G., and T.C.C.) extracted data into standardized tables per a prespecified structured checklist. Three authors (D.D., M.M.E., and W.G.) further reviewed the extracted data, entered the relevant numbers into the final extraction form, and added the quality scores.

We replicated the methods of Schernhammer and Colditz,11 including their quality scores. Additionally, we performed analyses based on approaches from recent studies.22,23

Following the meta-analysis approach if the primary outcome (the SMR) was not provided by the articles, we calculated SMR values from the observed (O) and expected (E) suicide deaths (SMR = O/E, where O equaled total physician suicides divided by the total physician population and E equaled total population suicides divided by the total population, using the same age groups, locations, and year ranges; eMethods 2 in the Supplement). That is, SMRs on suicides in physicians within each country were based on the comparison with the general population of that country of the same age group.

Statistical Analysis

The calculation for SMRs of the period being studied was the male or female physician suicide mortality rate per 100 000 person-years, divided by the suicide mortality rate of male or female individuals in the general population per 100 000 persons per year. If 95% CIs were missing, we estimated them using the logarithm of the proportions, assuming an approximate gaussian distribution. We also log-transformed the main SMR data using upper and lower CIs, accounting for the effect of potential extreme outliers, to check if the transformation changes the results.

We calculated all analyses using the statistical packages for meta-analysis of Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp). We tested for heterogeneity by giving commands for the Q test, I2, and also τ2 to estimate heterogeneity variance.24 Values of P < .10 for the Q test and greater than 35% for I2 were deemed indicative of study heterogeneity, according to the Cochrane Handbook.25 We used random-effects models for the analysis of male and female physicians, for comparability and because we assumed that the cohort populations across time and countries have differences that could affect the true results; this model addresses effect-size distributions and is better for potentially heterogeneous populations.26,27

The Begg and Egger tests,28,29 sensitivity analyses, meta-regression (including before and after 1980), and cumulative meta-analysis were performed (eMethods 3 in the Supplement). We also present proportionate mortality ratios (PMRs) when SMR data could not be extracted, such as National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health–National Outcomes Measurement System (eMethods 3 in the Supplement).

Furthermore, to evaluate the effect of quality scores and duration of cohort on SMR, we performed a meta-regression with each variable in a separate model and then ran a model with all variables (with the SMR as the dependent variable and the above-mentioned variables as the independent variables) by using a modified model.30 We also performed a meta-regression testing the effect of time (before and after 1980), sex, and the interaction term (time × sex) on SMR and on observed and expected suicide rates. For this meta-regression, pre-1980 data was extracted from Schernhammer and Colditz11 and post-1980 data was mainly from our meta-analysis.

Results

Search Results and Sample Characteristics

The initial search led to 7877 results. On applying our criteria, we ended up with 32 articles8,9,10,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61 (eFigure 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement). We excluded 13 studies from the systematic review (eTable 1 in the Supplement) and meta-analysis.

Systematic Review

Characteristics of Physician vs General Population Suicides in the Systematic Review

Twenty-one articles8,9,31,32,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,54,61,62 showed significant differences between suicide rates in physicians and those of the general population; 11 articles10,49,50,51,52,53,55,56,57,61,62 showed none. Most articles separated physicians by sex, with 11 studies8,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 and 9 articles8,33,35,36,39,41,42,43,44 showing significantly higher suicide risk in female and male physicians, respectively, than the general population. One article45 and 3 articles9,33,45 showed significantly lower rates among female and male physicians compared with the general population. Of articles that combined male and female individuals, 2 of 4 reported lower suicide rates among physicians,45,46 and the other half reported higher rates47,48 (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Psychiatric Comorbidities

Psychiatric illnesses were reported as risk factors in only 4 articles,44,49,50,51 mainly depression, substance abuse, or both. Prior suicide attempts and suicidal ideation were not discussed.

Demographic Factors

Eight studies34,36,37,44,47,50,51,52 reported the most prominent demographic risk factors for suicide. These were sex (although results were mixed), followed by increasing age.34,37,44,51 Additionally, there were mixed findings for race/ethnicity36,44,47 and consistent findings of increased risk for interpersonal relationship factors,47,50,51,52 especially being divorced,47,51,52 but also being widowed,51 single,52 or having relationship problems.50

Career-Associated Factors

Specialties were addressed in 7 articles.37,38,39,41,47,53,54 Physician specialties associated with higher risk of suicide included psychiatry37,41,53,54 and anesthesiology,39,41,54 followed by radiology,41 rehabilitation medicine,41 community health,54 and general practice.54 As to surgery, results were mixed.38,53 One study47 reported no differences between specialties.

Eight studies8,10,31,33,36,38,43,47 compared physician suicides with those of nonphysician occupations, with mixed results. Some found that physicians had higher suicide rates than other professions (including teachers, academics, and veterinarians),8,31,33,38,43,47 while other studies found increased risk in other professions (including dentists, pharmacists, and nurses).10,31,33,43 Some studies reported on a specific race or sex8,36,38,43 or found different occupation associations by sex.31

Work or training demands were indirectly hinted at by 6 studies.42,44,45,49,50,55 In the United States, male physicians mostly died by suicide when professionally productive,55 during early training,45 or following competitive schooling, when they had work problems, had work incapacity, or were working in isolation.42 Heavy workloads or isolation also contributed to suicidality.44,49,50

Suicide Methods

Sixteen articles9,31,33,37,39,40,41,44,45,47,48,50,51,52,53,55 included at least partial descriptions of physician suicide methods (eTable 2 in the Supplement), typically by poison, firearms, or suffocation. In the United States, Brazil, and South Africa, the common suicide methods were firearms and poisoning and were modulated by geographic location and sex (eTable 2 in the Supplement).41,44,45,51,52 Poisoning was also the most common choice in Europe,33,37,39,48,53 Australia,50 and New Zealand.9 Asphyxiation by hanging or other methods was often mentioned9,31,33,41,45,50,52,53 but was never reported as the most common method.

Meta-analysis

In our meta-analysis of 9 studies and data sets, there was a total of 547 male physician suicides and 162 female physician suicides (Table). Similar to Schernhammer and Colditz,11 consistency in quality scoring between reviewers was 97%.

Table. Meta-analysis of Male and Female Physician Suicides.

| Source | Suicides Among Physicians, No. | Deaths, No. per 100 000 Population | SE | Standardized Mortality Ratioa (95% CI) | Age Range, y | Total Quality Control | Location | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | ||||||||

| Innos et al,57 2002 | |||||||||

| Men | 6 | 6 | 10 | 0.4 | 0.58 (0.21-1.27) | 20-65 | 6 | Estonia | 1983-1998 |

| Women | 5 | 5 | 8 | 0.434 | 0.62 (0.20-1.45) | 20-65 | |||

| Petersen and Burnett,34 2008 | |||||||||

| Men | 181 | 21.3 | 27.2 | 0.170 | 0.8 (0.53-1.2) | 20-64 | 7 | 26 US states | 1984-1992 |

| Women | 22 | 11.8 | 5.7 | 0.603 | 2.39 (1.52-3.77) | 20-64 | |||

| Lindeman et al,37 1997 | |||||||||

| Men | 35 | 54 | 62 | 0.119 | 0.87 (0.69-1.10) | >25 | 7 | Finland | 1986-1993 |

| Women | 16 | 35 | 15 | 0.394 | 2.33 (1.08-5.05) | >25 | |||

| Hawton et al,54 2001 | |||||||||

| Men | 42 | 14 | 21 | 0.178 | 0.67 (0.47-0.87) | 25-64 | 6 | England and Wales | 1991-1995 |

| Women | 15 | 13 | 6 | 0.601 | 2.02 (1.00-3.04) | 25-59 | |||

| Kõlves et al,50 2013 | |||||||||

| Men | 20 | 21.09 | 30.58 | 0.150 | 0.69 (0.43-1.09) | 25-64 | 6 | Queensland, Australia | 1990-2007 |

| Women | 7 | 14.38 | 8.25 | 0.460 | 1.74 (0.76-3.78) | 25-64 | |||

| Palhares-Alves et al,52 2015 | |||||||||

| Men | 38 | 4.9 | 7.2 | 0.295 | 0.68 (0.29-1.16) | Mean age 46.8 (men and women combined) | 4 | São Paulo, Brazil | 2000-2009 |

| Women | 12 | 2.9 | 1.8 | 0.851 | 1.6 (0.54-2.78) | ||||

| Milner et al, 2016, and the Australian Bureau of Statistics31,58 | |||||||||

| Men | 62 | 14.8 | 22.1 | 0.174 | 0.67 (0.48-2.10) | 20-70 for physicians, 20-69 for population | 7 | Australia | 2001-2012 |

| Women | 17 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 0.408 | 1.03 (0.46-2.16) | 20-70 for physicians, 20-69 for population | |||

| ONS59 | |||||||||

| Men | 104 | 6.57 | 18.81 | 0.136 | 0.35 (0.27-3.74) | 20-64 | 7 | England | 2001-2010 |

| Women | 46 | 5.30 | 5.62 | 0.409 | 0.94 (0.42-2.37) | 20-64 | |||

| ONS59 | |||||||||

| Men | 59 | 12.4 | 18.9 | 0.186 | 0.63 (0.43-2.28) | 20-64 | 7 | England | 2011-2015 |

| Women | 22 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 0.434 | 1.01 (0.44-2.31) | 20-64 | |||

| Proportionate Mortality Ratiob | |||||||||

| NOMS59 | |||||||||

| White men | 398 | NA | NA | 0.052 | 1.77 (1.60-1.96) | 18-90 | 7 | 26 US states | 1985-1998 |

| Black men | 8 | NA | NA | 0.428 | 2.50 (1.08-4.92) | 18-90 | |||

| White women | 42 | NA | NA | 0.166 | 2.66 (1.92-3.60) | 18-90 | |||

| Black women | NA (<5) | NA | NA | NA | NA (<5) | 18-90 | |||

| NOMS63 | |||||||||

| White men | 310 | NA | NA | 0.059 | 2.03 (1.81-2.27) | 18-90 | 7 | 26 US states | 1999-2003, 2004-2007, 2013 |

| Black men | 11 | NA | NA | 0.354 | 4.24 (2.12-7.59) | 18-90 | |||

| White women | 51 | NA | NA | 0.151 | 2.42 (1.80-3.18) | 18-90 | |||

| Black women | NA (<5) | NA | NA | NA | NA (<5) | 18-90 | |||

| ONS59 | |||||||||

| Men | 59 | NA | NA | 0.139 | 1.85 (1.41-2.38) | 20-64 | 7 | England | 2011-2015 |

| Women | 22 | NA | NA | 0.240 | 1.97 (1.23-2.98) | 20-64 | |||

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; NIOSH, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; NOMS, National Occupational Mortality Service; ONS, Office for National Statistics.

Physician suicide mortality relative to that of general population.

The proportionate mortality ratio data are only for (1) US NOMS and NIOSH data, because we could not obtain a standardized mortality ratio, and (2) England ONS, to compare standardized mortality ratio and proportionate mortality ratio data.

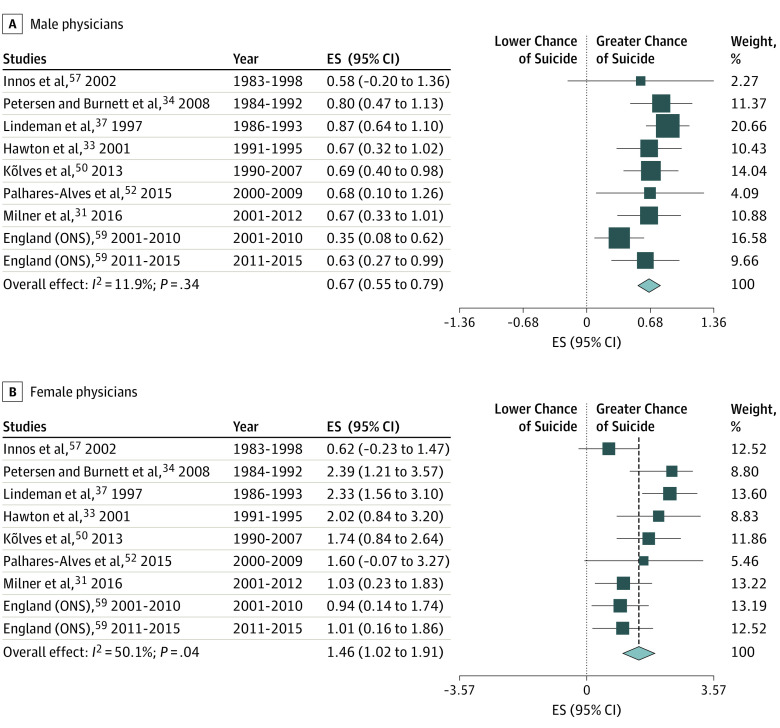

Male Physicians

Male physicians’ SMR was significantly lower than the SMR of the general male population (ie, there were lower suicide rates in male physicians than men in general; 0.67 [95% CI, 0.55-0.79]; Figure 1A). Heterogeneity testing results included a Cochran Q test of 9.08 (P < .001), an I2 of 11.9% (indicating low heterogeneity), and a τ2of 0.4%. Additionally, all studies’ 95% CIs overlapped.

Figure 1. Forest Plots of Random-Effects Models.

A, Male physicians. B, Female physicians. C, Age-standardized mortality ratio suicide in male physicians. D, Age-standardized mortality ratio for suicide in female physicians. ES indicates effect size.

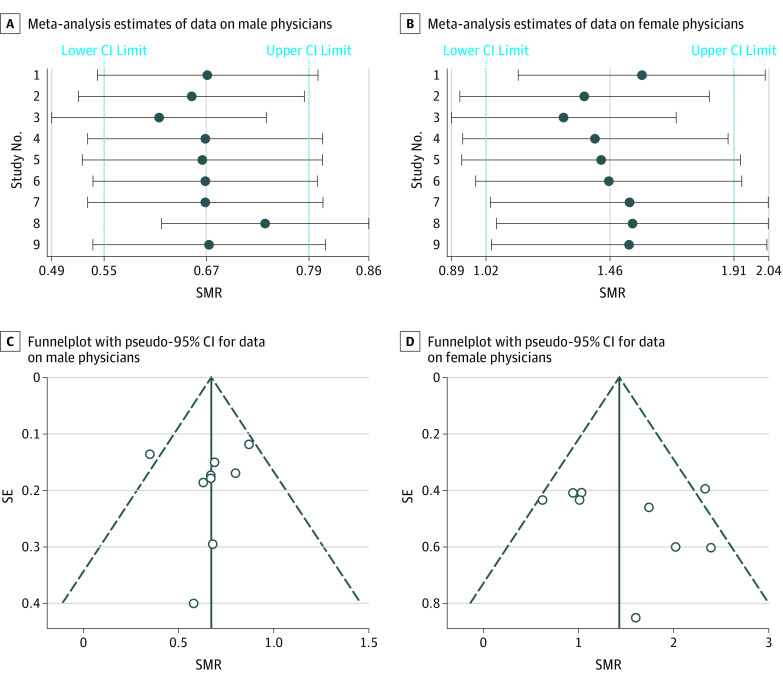

To better evaluate heterogeneity, we then performed sensitivity analyses on the male physician cohort by removing individual studies, which did not change the direction or significance of the pooled results (Figure 2B). When analyzing the subset of studies with higher quality scores (>5), the forest plot and sensitivity analysis were similar (eFigure 2 and eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Further evaluating heterogeneity, 2 univariate meta-regressions each showed no significant association between quality score (β = −0.067; P = .41) and duration of cohort (β = −0.004; P = .85) with SMR. A multiple meta-regression model including quality score and duration of cohort as variables and SMR as an outcome was not significant. Finally, log-transformed data showed a significant pooled effect of −0.29 (95% CI, −0.43 to −0.14) in the same direction as the main SMR analysis.

Figure 2. Sensitivity Analyses on Pooled Effects on Removing Individual Studies.

A, Male physicians. B, Female physicians. C, Funnel plots showing no publication bias for male physician suicide age-standardized mortality ratio for suicide (SMRs). D, Funnel plots showing no publication bias for female physician suicide SMRs.

Female Physicians

Female physicians’ SMR was significantly higher than the SMR of the general female population (ie, higher suicide rates in female physicians than women in general; SMR, 1.46 [95% CI, 1.02-1.91]; Figure 1B). Heterogeneity testing results included a Cochran Q test of 16.02 (P = .04), an I2 of 50.1% (moderate heterogeneity), and a τ2 of 22.6%.

To better evaluate heterogeneity, we then performed a sensitivity analysis by removing individual studies (Figure 2C). We found that on excluding several articles,33,34,37,50,52 the 95% CI crossed the null; that is, the risk of suicide among female physicians became not significantly greater than that of the general female population. Additionally, higher-quality studies31,34,37,50,54,57,58,59,63 had a nonsignificant SMR for female physicians, and the sensitivity analysis has a pattern similar to that of main analysis (eFigure 4 and eFigure 5 in the Supplement). Further evaluating heterogeneity, 2 univariate meta-regressions each showed no significant association between quality score (β = −0.081; P = .76) and duration of cohort (β = −0.042; P = .47) with SMR. A multiple meta-regression model including quality score and duration of cohort as variables and SMR as an outcome was not significant. Finally, log-transformed data showed a pooled effect size of 0.43 (95% CI, 0.13-0.72), which was significant and in the same direction as the SMR.

Publication Bias

There was no evidence of publication bias in studies on male and female physician suicides, as shown by respectively regressing suicide SMR with the inverse of study variance; in other words, the Egger test (intercept estimates: male physicians, −0.29; P = .78; female physicians, 0.85; P = .42), the Begg test (male physicians: continuity-corrected z score, 0.94; P = .35; female physicians: continuity-corrected z score, 0.63; P = .53), and the visual assessment of the funnel plot showed relative symmetry (Figure 2B).

Cumulative Meta-analysis Overall

We performed a cumulative meta-analysis (a statistical procedure to retrospectively calculate the sequence of meta-analyses by starting with a single study—the one with the earliest cohort—and adding the later studies one at a time); it shows how the overall estimate changes over time as each study is added to the pool. Calculating the cumulative evidence over time revealed significantly decreasing male physician SMR and increasing precision (effect sizes from 0.58 [95% CI, −0.20 to 1.36] to 0.67 [95% CI, 0.56-0.78]; eFigure 6 in the Supplement). This goes in the opposite direction of the previous cumulative meta-analysis.11 The cumulative meta-analysis among female physicians showed an early increase (effect sizes from 0.62 [95% CI, -0.23 to 1.47] to 1.76 [95% CI, 1.34-2.18]), followed by a trend toward decreasing suicide risk (effect size, 1.43 [95% CI, 1.12-1.73]) that is still high compared with women in the general population (eFigure 7 in the Supplement).

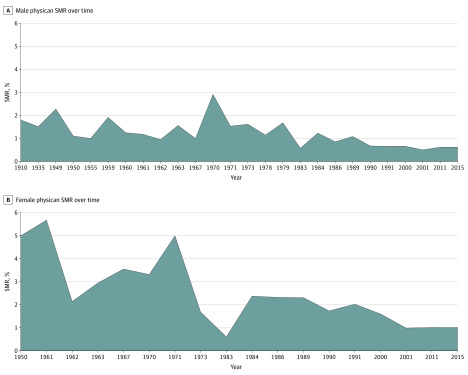

Meta-regression Comparing Cohorts Before and After 1980

In male physicians, the meta-regression of SMR over time (dichotomized by before and after 1980) led to a significant result of −0.84 (95% CI, −1.26 to −0.42; P < .001) and explained 36.9% (by adjusted R2) of the variance in the model. This represents an SMR decrease of 0.84 from the cohorts before 1980 to those after 1980.

In female physicians, the meta-regression of SMR over time (dichotomized to before and after 1980) led to a significant result of −1.96 (95% CI, −3.09 to −0.84; P = .002) and explained 43.9% (by adjusted R2) of the variance in the model. This represents an SMR decrease of 1.96.

Using a stepwise approach, we then tested a multivariate meta-regression model including time (before and after 1980) and sex (male and female physicians) and another model adding the interaction term time × sex. The meta-regression model better reflected the data and was significant (P < .001) with several terms (time, −0.85 [95% CI, −1.40 to –0.29]; P = .003; sex, 1.94 [95% CI, 1.25-2.62]; P < .001; interaction term time × sex, −1.06 [95% CI, −2.03 to −0.10]; P = .03). This is consistent with the greatest change being seen in female physicians after 1980 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Age-Standardized Mortality Ratio (SMR) for Suicide Trends Over Time.

A, Male physicians. B, Female physicians. Cohort years reflect the first year of each cohort, except for 2015, which reflects the last year of the last cohort. Pre-1980 cohort data were taken from a meta-analysis by Schernhammer and Colditz11; all post-1980 data were taken from the meta-analysis data sets, except for 3 studies in Schernhammer and Colditz.11

Meta-regression of Observed and Expected Suicide Rates Over Time

We performed separate meta-regressions of observed suicide rates in male and female physicians each, as well as separate meta-regressions of expected suicide rates in men and women of the general population each. The meta-regressions help us better understand whether the SMR changes over time (before and after 1980) were driven by observed suicide rates in physicians (male and female) or alternatively by expected suicide rates in men and women of the general population.

We found that on meta-regression assessing the association of time with expected suicide rates in men in the general population and the association of time with observed suicide rates in male physicians, both meta-regression results were in the direction of decreased suicides after 1980, but this was only significant in male physicians (β = −35.37 [95% CI, −62.33 to −8.41]; P = .01), and time explained 20.21% of the variance in the data. Meanwhile, the results were nonsignificant in each of the meta-regressions for expected suicide rates among women in the general population) and observed suicide rates in female physicians (eMethods 5 in the Supplement).

Data Sets Not in Main Analysis

Physician SMRs compare observed suicide rates (suicides in physicians divided by physician populations) to expected suicide rates (suicides in the general population divided by the general population). Conversely, physician-suicide PMRs indicate the ratio of physician-suicide proportionate mortality (ie, suicides divided by all-cause mortality within physician populations) to general population–suicide proportionate mortality (ie, suicides divided by all-cause mortality within general populations). In the United States (per National Outcomes Measurement System–National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health data), physician PMRs respectively increased in white male physicians and especially black male physicians from the first recorded time span (1985-1998) to the second (roughly 1999-2014) (white male physicians, 1.77 [95% CI, 1.60-1.96] vs 2.03 [95% CI, 1.81-2.27]; black male physicians, 2.50 [95% CI, 1.08-4.92] vs 4.24 [95% CI, 2.12-7.59]) but decreased for white female physicians during those periods (2.66 [95% CI, 1.92-3.60] vs 2.42 [95% CI, 1.80-3.18]) (Table). (There were insufficient suicide data on black female physicians.) The US PMR data indicate that suicide makes up a higher proportion of all-cause mortality within all these physician groups than it does for the comparable general populations of the same ages, sexes, and races—that is, suicide causes more of the deaths within the physician populations than within the general population.

As to the English data set (2011-2015; Table), the suicide PMR was also high for male physicians (1.85 [95% CI, 1.41-2.38]) and higher for female physicians (1.97 [95% CI, 1.23-2.98]), which was significant in both cases despite the much lower and nonsignificant risks suggested by their suicide SMRs (0.63 [95% CI, 0.43-2.28] and 1.01 [95% CI, 0.44-2.31] for male and female physicians, respectively). This apparent discrepancy within the same sample reflects the differences in how SMRs and PMRs are calculated.

Suicide rates in male physicians (observed rate, 12.4 per 100 000 population) were lower than rates in men in the general population (expected rate, 18.9 per 100 000 population), which was consistent with the low SMR for male physicians and implied that the elevated PMR was driven by relatively lower all-cause mortality rather than more suicides in male physicians compared with men in general. Likewise, female physicians and women in general had similar suicide rates (5.5 per 100 000 population and 5.4 per 100 000 population, respectively); therefore, the elevated PMR in female physicians may be driven by lower all-cause mortality relative to women in general.

Discussion

The latest meta-analysis of physician suicide was published in 200411 and included cohort data mainly before 1980. That study found suicide SMRs in male physicians (1.41 [95% CI, 1.21-1.65]) and especially female physicians (2.27 [95% CI, 1.90-2.73]) significantly higher than the expected population suicide rates. We had therefore hypothesized a higher risk of physician suicides compared with the general population from the 1980s to date, and our data confirmed a high SMR for female physicians (1.46) but a low SMR for male physicians (0.67). We had also hypothesized that the suicide SMRs of both female and male physicians seen before 1980 would decrease after 1980, and this was confirmed by the models; additionally, female physicians had the greatest decrease in SMR after 1980. These population-based findings are of great relevance, because physician suicide is an important and understudied topic.

Our meta-regression suggested that the decrease in male physician suicide SMR over time was driven by the rate of physician suicides rather than population suicides. This may be because male physicians are relatively protected from workforce or unemployment factors affecting men of lower socioeconomic status, which may have obscured any burnout-associated outcomes. Conversely, we could not make the same claim for female physicians vs women in the general population, potentially because the pre-1980 data was underpowered. Yet the SMR for female physicians, while decreasing, was still high, implying that greater female representation in the physician workforce may not have overcome the magnitude of their increased risk compared with women in general. It also raises the question of a lag in improved workforce conditions compared with workforce numbers.

Meanwhile, the PMR and SMR data within a single sample provide different views of physician suicides. For example, SMR data suggest that male physicians in England are at lower risk of suicide than the male population while female physicians had risk comparable with that of women in general, yet the PMR data suggest that suicide makes up a relatively large proportion of mortality in both male and female physicians, perhaps because physicians die less frequently of other (eg, cardiovascular, pulmonary) causes. This is consistent with studies in Denmark48 and Maryland41 suggesting lower overall physician mortality yet greater suicide mortality compared with what would be expected. As to the United States, we find that PMRs are high in black and white male physicians and white female physicians. It is important to highlight that SMRs and PMRs are different health indicators with potentially different applications—for example, a physician might care more about risk of suicide compared with dying of other causes, while a policy maker might prioritize how suicide risk in physicians compares with that of the general population. Overall, suicide is among the top 10 mortality causes in physicians and general population per the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institute for Mental Health.64 We further discuss important risk factors.

Suicide Risks and Methods

Generally speaking, major risk factors for suicide in the population are previous suicide attempts; a family history of suicide; mental disorders; homosexuality; male sex; divorced, widowed, or single marital or relationship status; young adult or elderly age ranges; acute stressors; and childhood trauma.7,65,66,67 However, we only found reports associated with sex, relationship status, and age factors. Suicide methods were by poisoning or drugs, firearms, and suffocation, but the frequency varied by geographic location (and accessibility), sex, and other factors. In this review, career-associated factors seemed to be the most prominent risk, while psychiatric illnesses seemed to be underreported.52,68,69

Psychiatric Disorders

The most common disorders in this review were depression and/or substance abuse. Unfortunately, physicians are less likely to seek mental health services70 out of career concerns, culture, and/or a predisposition toward self-reliance. Additionally, retrospective toxicology screening of suicide data finds that physicians are more likely than nonphysicians to have positive results for antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates but not antidepressants.68 This links to physicians being undertreated for depression despite current effective treatments,71 whereas the positive toxicology findings may indicate substance abuse, self-medication, or intentional toxicity.

Associated With Career/Work

Psychiatry and anesthesiology were the top 2 specialties at risk in this review. However, we excluded studies analyzing only specialist data, some of which reported higher suicide rates for anesthesiologists, typically by drugs.72,73,74,75 It is well established that anesthesiologists tend to have much higher rates of substance abuse than other physicians.76 Psychiatrists are also known to have more mental distress, mental illness, and burnout compared with other physician groups, and 1 systematic review77 found concerning rates of depression, psychotropic drug use, and “almost-clinical-level emotional disturbance caused by patient suicide.”77(p212) Our review hints at career or workload burden contributions to suicidality.39,43,51 Some associated factors could be the judicialization of medicine, organization oversight, and burnout, topics that are beyond the scope of this article.

Demographics

Some of the most consistent physician suicide risk factors were increasing age, and divorce or relationships, although marriage is reportedly protective in men and not clearly so in women or female physicians.70 Additionally, there is some suggestion of an association between sex, race, and suicidality (eg, an elevated risk in black male physicians).

Implications

Physician suicide is suboptimally reported and addressed; our meta-analysis showed decreasing suicide rates, but the data sets showed paradoxical trends that may be affected by gender, race, location, and time. What is driving the data? Studies need to be systematized to clarify underlying patterns, identify vulnerable subsets of physicians at risk, and explore suicide prevention by addressing the modifiable risk factors suggested by this research.

Limitations

A probable bias in physician suicidality studies is underreporting, because colleagues may be unwilling to classify deaths as suicides.38,43,53 For example, most unintentional poisonings involved prescription drugs, yet physicians probably would not unintentionally overdose more than the population.53 Another limitation is broad study locations, time span, and methods (eg, different International Classification of Diseases codes and data sources). However, quality scores, analysis of heterogeneity, publication bias, and meta-regression were used to increase validity.

Similar to the previous meta-analysis,11 our study primarily reflects northern European and North American populations (eMethods 6 in the Supplement). The National Outcomes Measurement System data sets do not include races other than black and white. However, other racial/ethnic groups, particularly Asian populations, are more highly represented in medicine than in the general population.12

Conclusions

Our population-based meta-analysis showed suicide SMRs that were high in female physicians and low in male physicians after 1980, and both SMRs decreased over time (from before to after 1980). Nevertheless, suicide PMRs highlight the importance of suicide relative to other causes of mortality in physicians. This qualitative and quantitative work illustrates physician suicide patterns and characteristics for future studies and policies.

eMethods 1. Literature search.

eFigure 1. Flow diagram of the systematic review

eMethods 2. Data Extraction

eMethods 3. Statistical Analysis

eTable 1. Papers excluded from main review and analyses, and the reasons for exclusion

eMethods 4. Meta-analysis

eTable 2. Systematic review of physician suicide

eFigure 2. Forest plot of male physician suicide high quality studies using random effects model

eFigure 3. Sensitivity analysis of male physician suicide high quality studies

eFigure 4. Forest plot of female physician suicide high quality studies using random effects model

eFigure 5. Sensitivity analysis of female physician suicide high quality studies

eFigure 6. Cumulative meta-analysis of male physician studies per year of cohort

eFigure 7. Cumulative meta-analysis of female physician studies per year of cohort

eMethods 5. Meta-regression of observed and expected suicide rates over time

eMethods 6. Other Datasets Not in Main Analysis

eReferences.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Suicide data. https://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/#.XMG_V82L8bE.mendeley. Published 2018. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- 2.World Health Organization Disease burden and mortality estimates. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/index1.html#.XMHAUySKxRI.mendeley. Published 2019. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- 3.Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, et al. ; GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators . Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459-1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Crosby AE, Jack SPD, Haileyesus T, Kresnow-Sedacca M-J. Suicide trends among and within urbanization levels by sex, race/ethnicity, age group, and mechanism of death—United States, 2001-2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(18):1-16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28981481. Internet. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6618a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. . Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):98-105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duarte DGG, Neves M de CL, Albuquerque MR, de Souza-Duran FL, Busatto G, Corrêa H. Gray matter brain volumes in childhood-maltreated patients with bipolar disorder type I: a voxel-based morphometric study. J Affect Disord. 2016;197:74-80. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro e Couto T, Brancaglion MYM, Cardoso MN, et al. . Suicidality among pregnant women in Brazil: prevalence and risk factors. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(2):343-348. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0552-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefansson CG, Wicks S. Health care occupations and suicide in Sweden 1961-1985. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1991;26(6):259-264. doi: 10.1007/BF00789217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skegg K, Firth H, Gray A, Cox B. Suicide by occupation: does access to means increase the risk? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(5):429-434. doi: 10.3109/00048670903487191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts SE, Jaremin B, Lloyd K. High-risk occupations for suicide. Psychol Med. 2013;43(6):1231-1240. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA. Suicide rates among physicians: a quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis). Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2295-2302. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in medical education: AAMC facts & figures 2016. https://www.aamcdiversityfactsandfigures2016.org/. Published 2016. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- 13.US Department of Labor Facts over time—women in the labor force. https://www.dol.gov/wb/stats/NEWSTATS/facts/women_lf.htm#one. Published 2016. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- 14.Rothenberger DA. Physician burnout and well-being: a systematic review and framework for action. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(6):567-576. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wood J. Exploring the decline in the male share of college enrollment: what it says about masculinity. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/262/?utm_source=scholarworks.uvm.edu%2Fhcoltheses%2F262&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages. Published 2018. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- 17.Milner A, Page A, LaMontagne AD. Cause and effect in studies on unemployment, mental health and suicide: a meta-analytic and conceptual review. Psychol Med. 2014;44(5):909-917. . doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Bureau of Labor Statistics International comparisons of annual labor force statistics, 1970-2012. https://www.bls.gov/fls/flscompar elf/lfcompendium.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- 19.Peterson C, Stone DM, Marsh SM, et al. . Suicide rates by major occupational group—17 states, 2012 and 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(45):1253-1260. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6745a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. . Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting, Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334-341. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manouchehrinia A, Tanasescu R, Tench CR, Constantinescu CS. Mortality in multiple sclerosis: meta-analysis of standardised mortality ratios. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(3):324-331. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-310361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaimani A, Mavridis D, Salanti G. A hands-on practical tutorial on performing meta-analysis with Stata. Evid Based Ment Health. 2014;17(4):111-116. doi: 10.1136/eb-2014-101967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Sterne JA Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5. http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/. Published 2011. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- 26.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Rothstein H Meta-analysis fixed effect vs. random effects. https://www.meta-analysis.com/downloads/M-a_f_e_v_r_e_sv.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- 27.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt A):139-145. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088-1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knapp G, Hartung J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat Med. 2003;22(17):2693-2710. doi: 10.1002/sim.1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milner AJ, Maheen H, Bismark MM, Spittal MJ. Suicide by health professionals: a retrospective mortality study in Australia, 2001-2012. Med J Aust. 2016;205(6):260-265. doi: 10.5694/mja15.01044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Everson RB, Fraumeni JFJ Jr. Mortality among medical students and young physicians. J Med Educ. 1975;50(8):809-811. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197508000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawton K, Agerbo E, Simkin S, Platt B, Mellanby RJ. Risk of suicide in medical and related occupational groups: a national study based on Danish case population-based registers. J Affect Disord. 2011;134(1-3):320-326. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petersen MR, Burnett CA. The suicide mortality of working physicians and dentists. Occup Med (Lond). 2008;58(1):25-29. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqm117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hem E, Haldorsen T, Aasland OG, Tyssen R, Vaglum P, Ekeberg O. Suicide rates according to education with a particular focus on physicians in Norway 1960-2000. Psychol Med. 2005;35(6):873-880. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704003344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frank E, Biola H, Burnett CA. Mortality rates and causes among U.S. physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(3):155-159. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00201-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindeman S, Läärä E, Hirvonen J, Lönnqvist J. Suicide mortality among medical doctors in Finland: are females more prone to suicide than their male colleagues? Psychol Med. 1997;27(5):1219-1222. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnetz BB, Hörte LG, Hedberg A, Theorell T, Allander E, Malker H. Suicide patterns among physicians related to other academics as well as to the general population: results from a national long-term prospective study and a retrospective study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1987;75(2):139-143. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02765.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richings JC, Khara GS, McDowell M, McDowell M. Suicide in young doctors. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;149:475-478. doi: 10.1192/bjp.149.4.475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pitts FNJ Jr, Schuller AB, Rich CL, Pitts AF. Suicide among U.S. women physicians, 1967-1972. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(5):694-696. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.5.694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torre DM, Wang N-Y, Meoni LA, Young JH, Klag MJ, Ford DE. Suicide compared to other causes of mortality in physicians. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35(2):146-153. doi: 10.1521/suli.35.2.146.62878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ullmann D, Phillips RL, Beeson WL, et al. . Cause-specific mortality among physicians with differing life-styles. JAMA. 1991;265(18):2352-2359. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03460180058033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rimpelä AH, Nurminen MM, Pulkkinen PO, Rimpelä MK, Valkonen T. Mortality of doctors: do doctors benefit from their medical knowledge? Lancet. 1987;1(8524):84-86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)91919-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dean G. The causes of death of South African doctors and dentists. S Afr Med J. 1969;43(17):495-500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yaghmour NA, Brigham TP, Richter T, et al. . Causes of death of residents in ACGME-accredited programs 2000 through 2014: implications for the learning environment. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):976-983. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shang T-F, Chen P-C, Wang J-D. Mortality of doctors in Taiwan. Occup Med (Lond). 2011;61(1):29-32. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqq159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rose KD, Rosow I. Physicians who kill themselves. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973;29(6):800-805. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.04200060072011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Juel K, Mosbech J, Hansen ES. Mortality and causes of death among Danish medical doctors 1973-1992. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(3):456-460. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.3.456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iannelli RJ, Finlayson AJ, Brown KP, et al. . Suicidal behavior among physicians referred for fitness-for-duty evaluation. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(6):732-736. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kõlves K, De Leo D, Kõlves K, et al. . Suicide in medical doctors and nurses: an analysis of the Queensland Suicide Register. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201(11):987-990 doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Revicki DA, May HJ. Physician suicide in North Carolina. South Med J. 1985;78(10):1205-1207. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198510000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palhares-Alves HN, Palhares DM, Laranjeira R, Nogueira-Martins LA, Sanchez ZM. Suicide among physicians in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, across one decade. Braz J Psychiatry. 2015;37(2):146-149. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carpenter LM, Swerdlow AJ, Fear NT. Mortality of doctors in different specialties: findings from a cohort of 20000 NHS hospital consultants. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54(6):388-395. doi: 10.1136/oem.54.6.388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hawton K, Clements A, Sakarovitch C, Simkin S, Deeks JJ. Suicide in doctors: a study of risk according to gender, seniority and specialty in medical practitioners in England and Wales, 1979-1995. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(5):296-300. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.5.296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rich CL, Pitts FNJ Jr. Suicide by male physicians during a five-year period. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(8):1089-1090. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.8.1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meltzer H, Griffiths C, Brock A, Rooney C, Jenkins R. Patterns of suicide by occupation in England and Wales: 2001-2005. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(1):73-76. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Innos K, Rahu K, Baburin A, Rahu M. Cancer incidence and cause-specific mortality in male and female physicians: a cohort study in Estonia. Scand J Public Health. 2002;30(2):133-140. doi: 10.1177/14034948020300020701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Australian Bureau of Statistics 3317.0.55.002–information paper: ABS causes of death statistics: concepts, sources and methods, 2006. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/3317.0.55.002Main+Features12006?OpenDocument. Published 2008. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- 59.UK Office for National Statistics Welcome to the Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- 60.Asp S, Hernberg S, Collan Y. Mortality among Finnish doctors, 1953-1972. Scand J Soc Med. 1979;7(2):55-62. doi: 10.1177/140349487900700202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dublin LI, Spiegelman M, Leland RG. Longevity and mortality of physicians. Postgrad Med. 1947;2(3):188-202. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1947.11692566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.National Occupational Mortality Surveillance (NOMS) PMR query system for industry (1999, 2003-2004, 2007-2014). https://wwwn.cdc.gov/niosh-noms/industry2.aspx. Published 2018. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- 63.National Occupational Mortality Surveillance PMR query system for occupation, 1985-1998. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/niosh-noms/industry1.aspx. Published 2015. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- 64.National Institutes of Health Suicide. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml. Published 2019. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- 65.Turecki G, Brent DA. Suicide and suicidal behaviour. Lancet. 2016;387(10024):1227-1239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00234-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Duarte DGG, Neves MCL, Albuquerque MR, et al. . Structural brain abnormalities in patients with type I bipolar disorder and suicidal behavior. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2017;265:9-17. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2017.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duarte DG, Neves M de C, Albuquerque MR, Neves FS, Corrêa H. Sexual abuse and suicide attempt in bipolar type I patients. Braz J Psychiatry. 2015;37(2):180-182. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gold KJ, Sen A, Schwenk TL. Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(1):45-49 doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hikiji W, Fukunaga T. Suicide of physicians in the special wards of Tokyo Metropolitan area. J Forensic Leg Med. 2014;22:37-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2013.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Physician suicide: a fleeting moment of despair. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6(1):18-22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.El-Hagrassy MM, Jones F, Rosa G, Fregni F. CNS non-invasive brain stimulation In: Gilleran J, Alpert S (Eds). Adult and Pediatric Neuromodulation. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing, Cham; 2018:151-184. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-73266-4_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lew EA. Mortality experience among anesthesiologists, 1954-1976. Anesthesiology. 1979;51(3):195-199. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197909000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alexander BH, Checkoway H, Nagahama SI, Domino KB. Cause-specific mortality risks of anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2000;93(4):922-930. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200010000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neil HA, Fairer JG, Coleman MP, Thurston A, Vessey MP. Mortality among male anaesthetists in the United Kingdom, 1957-83. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;295(6594):360-362. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6594.360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ohtonen P, Alahuhta S. Mortality rates for Finnish anaesthesiologists and paediatricians are lower than those for the general population. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2017;61(8):880-884. doi: 10.1111/aas.12936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mayall R. Substance abuse in anaesthetists. BJA Educ. 2016;16(7):236-241. doi: 10.1093/bjaed/mkv054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Howard R, Kirkley C, Baylis N. Personal resilience in psychiatrists: systematic review. BJPsych Bull. 2019;43(5):209-215. doi: 10.1192/bjb.2019.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Literature search.

eFigure 1. Flow diagram of the systematic review

eMethods 2. Data Extraction

eMethods 3. Statistical Analysis

eTable 1. Papers excluded from main review and analyses, and the reasons for exclusion

eMethods 4. Meta-analysis

eTable 2. Systematic review of physician suicide

eFigure 2. Forest plot of male physician suicide high quality studies using random effects model

eFigure 3. Sensitivity analysis of male physician suicide high quality studies

eFigure 4. Forest plot of female physician suicide high quality studies using random effects model

eFigure 5. Sensitivity analysis of female physician suicide high quality studies

eFigure 6. Cumulative meta-analysis of male physician studies per year of cohort

eFigure 7. Cumulative meta-analysis of female physician studies per year of cohort

eMethods 5. Meta-regression of observed and expected suicide rates over time

eMethods 6. Other Datasets Not in Main Analysis

eReferences.