Abstract

Orthaga olivacea Warre (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) is an important agricultural pest of camphor trees (Cinnamomum camphora). To further supplement the known genome-level features of related species, the complete mitochondrial genome of Orthaga olivacea is amplified, sequenced, annotated, analyzed, and compared with 58 other species of Lepidopteran. The complete sequence is 15,174 bp, containing 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 22 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, 2 ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes, and a putative control region. Base composition is biased toward adenine and thymine (79.02% A+T) and A+T skew are slightly negative. Twelve of the 13 PCGs use typical ATN start codons. The exception is cytochrome oxidase 1 (cox1) that utilizes a CGA initiation codon. Nine PCGs have standard termination codon (TAA); others have incomplete stop codons, a single T or TA nucleotide. All the tRNA genes have the typical clover-leaf secondary structure, except for trnS(AGN), in which dihydrouridine (DHU) arm fails to form a stable stem-loop structure. The A+T-rich region (293 bp) contains a typical Lepidopter motifs ‘ATAGA’ followed by a 17 bp poly-T stretch, and a microsatellite-like (AT)13 repeat. Codon usage analysis revealed that Asn, Ile, Leu2, Lys, Tyr and Phe were the most frequently used amino acids, while Cys was the least utilized. Phylogenetic analysis suggested that among sequenced lepidopteran mitochondrial genomes, Orthaga olivacea Warre was most closely related to Hypsopygia regina, and confirmed that Orthaga olivacea Warre belongs to the Pyralidae family.

Introduction

The insect mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is a closed-circular molecule ranging in size from 14,000 to 19,000 bp [1]. It generally contains 37 genes, of which seven are NADH dehydrogenase subunits (nad1-nad6 and nad4L), three cytochrome C oxidase subunits (cox1-cox3), two ATPase subunits (atp6 and atp8), one cytochrome b (cytb) subunit, two ribosomal RNAs (rrnL and rrnS), and 22 transfer RNAs (tRNA) [2, 3], and a variable length A+T-rich region, the largest noncoding sequence that modulates transcription and replication [4, 5, 6]. Whole mitochondrial genomes are a useful data source for several research areas [7, 8], such as evolutionary genomics [9, 10] and comparative molecular evolution [11, 12], phylogeography [13], and population genetics [14].

The Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) comprises over 160,000 described species, classified into 45–48 superfamilies and is cosmopolitan in distribution [15]. Pyralidae is one of the largest families in Lepidoptera, including over 25,000 species and some of pyralids are important agricultural pests, such as Ostrinia nubilalis and Cnaphalocrocis medinalis, whose complete mitogenomes had been sequenced [16–18]. Despite their diversity and great importance as pests of agricultural and forestry plants, they are also valuable for pollinating plants of economic importance. Most species in the family Pyralidae do not yet have sequenced mitogenomes.

Orthaga olivacea Warre (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) is a notorious pest, widely distributed in East China. The larvae feed on Cinnamomum camphora leaves and cause considerable economic losses. Farmers apply chemical prevention and removal strategies to combat this pest species particularly during larval and pupa life stages [19]. However, overlapping generations and irregularity of abundance in the field from May to October make it very difficult to control [19]. Previous studies have investigated the host preference, distribution and morphological characteristics of Orthaga olivacea Warre, and the control of it by bio-pesticide has been investigated [20, 21]. However, the use of pesticides is harmful to the environment. Therefore, it is necessary to find new strategies to prevent this pest. In this study we sequenced the complete mitogenome of Orthaga olivacea Warre, and compared it with other insect species, especially with the members of Pyralidae species. Phylogenetic relationships among lepidopteran superfamilies were reconstructed using the nucleotide sequences from the 13 PCGs to test the position of Orthaga olivacea within Pyralidae. The study of mitogenomes of Orthaga olivacea can provide fundamental information for mitogenome architecture, phylogeography, future phylogenetic analyses of Pyralidae, and biological control of pests.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and DNA isolation

Orthaga olivacea Warre, larvae (the larvae are about 22–30 mm long, brown, reddish-brown on the head and anterior thoracic plate, and have a brown wide band on the back of the body, with two yellow-brown lines on each side.) were collected from the camphor trees on the campus of Anhui Agricultural University (Hefei, China). Specimens were preserved with 100% ethanol and stored at -80°C. This insect is not an endangered or protected species. Total genomic DNA was extracted from the larvae using the Aidlab Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Aidlab Co., Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Extracted DNA quality was assessed by 1% agarose (w/v) gel electrophoresis.

Amplification and sequencing

Thirteen pairs of conserved primers were designed from the mitogenomes of previously sequenced Pyralidae species (synthesized by BGI Tech Co., Shenzhen, China) (Table 1). All PCRs were performed in 50 μL reaction volumes; 34.75 μL sterilized distilled water, 5 μL 5 × Taq buffer (Mg2+ plus), 4 μL dNTPs (2.5 mM), 2 μL genomic DNA, 2 μL of each primer (10 μM) and 0.25 μL (1.25 unit) Taq polymerase (TaKaRa Co., Dalian, China). A two-step PCR was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 30s at 94°C, annealing 2–3 min (depending on putative length of the fragments) at 51–58°C (depending on primer combination) and a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min.

Table 1. Details of the primers used to amplify the mitogenome of O. olivacea Warre.

| Primer pair | Primer sequence (5’ -3’) |

|---|---|

| F1 | TAAAAATAAGCTAAATTTAAGCTT |

| R1 | TATTAAAATTGCAAATTTTAAGGA |

| F2 | AAACTAATAATCTTCAAAATTAT |

| R2 | AAAATAATTTGTTCTATTAAAG |

| F3 | ATTCTATATTTCTTGAAATATTAT |

| R3 | CATAAATTATAAATCTTAATCATA |

| F4 | TGAAAATGATAAGTAATTTATTT |

| R4 | AATATTAATGGAATTTAACCACTA |

| F5 | TAAGCTGCTAACTTAATTTTTAGT |

| R5 | CCTGTTTCAGCTTTAGTTCATTC |

| F6 | CCTAATTGTCTTAAAGTAGATAA |

| R6 | TGCTTATTCTTCTGTAGCTCATAT |

| F7 | TAATGTATAATCTTCGTCTATGTAA |

| R7 | ATCAATAATCTCCAAAATTATTAT |

| F8 | ACTTTAAAAACTTCAAAGAAAAA |

| R8 | TCATAATAAATTCCTCGTCCAATAT |

| F9 | GTAAATTATGGTTGATTAATTCG |

| R9 | TGATCTTCAAATTCTAATTATGC |

| F10 | CCGAAACTAACTCTCTCTCACCT |

| R10 | CTTACATGATCTGAGTTCAAACCG |

| F11 | CGTTCTAATAAAGTTAAATAAGCA |

| R11 | AATATGTACATATTGCCCGTCGCT |

| F12 | TCTAGAAACACTTTCCAGTACCTC |

| R12 | AATTTTAAATTATTAGGTGAAATT |

| F13 | TAATAGGGTATCTAATCCTAGTT |

| R13 | ACTTAATTTATCCTATCAGAATAA |

PCR amplicons were analyzed on 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis, and purified using a gel extraction kit (CWBIO Co., Beijing, China). Purified fragments were ligated into the T-vector (TaKaRa Co., Dalian, China) and transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α. Positive recombinant colonies with insert DNA were sequenced in both directions and at least three times by Invitrogen Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Sequence annotation

The complete mtDNA sequence was assembly using the DNAStar package (DNAStar Inc. Madison, USA) and sequence annotation was performed using the blast tools from NCBI (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast). The sequences were submitted to GenBank at NCBI under the accession number MN078362. The tRNA genes were identified using the tRNAscan-Se program software available online at http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/, and visually identify sequences using the alignment with the appropriate anticodons capable of folding into the typical clover-leaf structure [22]. PCGs were initially identified by sequence identity with Pyralidae species and aligned with the other lepidopteran using ClustalX version 2.0 [23]. Nucleotide sequences of the PCGs were translated into their putative amino acids based on the invertebrate mtDNA genetic code. Composition skew was performed according to the formulas AT skew = [A−T]/[A+T], GC skew = [G−C]/[G+C]) [24]. Relative Synonymous Codon Usage (RSCU) values were calculated in MEGA 6.0 [25]. Tandem repeats in the A+T-rich region were predicted using the Tandem Repeats Finder program (http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.html) [26].

Phylogenetic analysis

To reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships of Lepidoptera, 58 lepidopteran mitogenomes (Table 2) representing seven lepidopteran superfamilies (Bombycoidea, Noctuoidea, Geometroidea, Pyraloidea, Tortricoidea, Papilionoidea and Yponomeutoidea) were used. The mitogenomes of Limnephilus hyalinus (NC_044710.1) [27], Locusta migratoria (NC_001712.1) [28], and Drosophila yakuba (NC_001322) [29] were used as outgroups. The 13 PCGs concatenated nucleotide sequences of these lepidopterans were initially aligned using ClustalX version 2.0. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using Maximum Likelihood (ML) method with the MEGA 6.0 program. This method was used to infer phylogenetic trees with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Table 2. Details of the lepidopteran mitogenomes used in this study.

| Superfamily | Family | Species | Size (bp) | GenBank accession no. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bombycoidea | Bombycidae | Bombyx mandarina | 15,682 | AY301620 | [30] |

| Bombyx mori | 15,643 | NC_002355 | Direct submission | ||

| Rondotia menciana | 15,301 | KC881286.1 | [31] | ||

| Saturniidae | Antheraea pernyi | 15,566 | AY242996 | [32] | |

| Antheraea yamamai | 15,338 | NC_012739 | [33] | ||

| Sphingidae | Manduca sexta | 15,516 | NC_010266 | [34] | |

| Sphinx morio | 15299 | KC470083.1 | [35] | ||

| Noctuoidea | Lymantriidae | Lymantria dispar | 15,569 | NC_012893 | Unpublished |

| Euproctis pseudoconspersa | 15461 | KJ716847.1 | [36] | ||

| Erebidae | Amata formosae | 15,463 | KC513737 | [37] | |

| Notodontidae | Ochrogaster lunifer | 15,593 | NC_011128 | [38] | |

| Noctuidae | Ctenoplusia agnata | 15261 | KC414791.1 | [39] | |

| Agrotis ipsilon | 15,377 | KF163965 | [40] | ||

| Nolidae | Gabala argentata | 15,337 | KJ410747 | [41] | |

| Geometroidea | Geometridae | Apocheima cinerarium | 15,722 | KF836545 | [42] |

| Biston thibetaria | 15,484 | KJ670146.1 | Unpublished | ||

| Pyraloidea | Crambidae | Chilo suppressalis | 15,395 | NC_015612 | [43] |

| Diatraea saccharalis | 15,490 | NC_013274 | [44] | ||

| Ostrinia furnacalis | 14,536 | NC_003368 | [45] | ||

| Ostrinia nubilalis | 14,535 | NC_003367.1 | [45] | ||

| Cnaphalocrocis medinalis | 15388 | NC_015985 | [43] | ||

| Paracymoriza distinctalis | 15354 | KF859965.1 | [46] | ||

| Tyspanodes hypsalis | 15329 | NC_025569 | [47] | ||

| Paracymoriza prodigalis | 15,326 | NC_020094.1 | [48] | ||

| Elophila interruptalis | 15,351 | NC_021756.1 | [49] | ||

| Pseudargyria interruptella | 15.231 | NC_029751.1 | Direct submission | ||

| Chilo auricilius | 15,367 | NC_024644.1 | [50] | ||

| Chilo sacchariphagus | 15,378 | NC_029716.1 | Direct submission | ||

| Evergestis junctalis | 15,438 | NC_030509.1 | Direct submission | ||

| Nomophila noctuella | 15,309 | NC_025764.1 | [51] | ||

| Tyspanodes striata | 15,255 | NC_030510.1 | Direct submission | ||

| Glyphodes quadrimaculalis | 15,255 | NC_022699.1 | [52] | ||

| Spoladea recurvalis | 15,273 | NC_027443.1 | [53] | ||

| Dichocrocis punctiferalis | 15,355 | NC_021389.1 | [54] | ||

| Glyphodes pyloalis | 14,960 | NC_025933.1 | Unpublished | ||

| Maruca vitrata | 15,385 | NC_024099.1 | Unpublished | ||

| Maruca testulalis | 15,110 | NC_024283.1 | [55] | ||

| Haritalodes derogat | 15,253 | NC_029202.1 | Unpublished | ||

| Pycnarmon lactiferalis | 15,219 | NC_033540.1 | [56] | ||

| Loxostege sticticalis | 15,218 | NC_027174.1 | Unpublished | ||

| Pyralidae | Orthaga olivacea Warre | This study | |||

| Lista haraldusalis | 15213 | NC_024535 | [57] | ||

| Galleria mellonella | 15320 | KT750964 | Unpublished | ||

| Corcyra cephalonica | 15,273 | NC_016866.1 | [58] | ||

| Amyelois transitella | 15,205 | NC_028443.1 | [59] | ||

| Plodia interpunctella | 15,264 | NC_027961.1 | Unpublished | ||

| Ephestia kuehniella | 15,295 | NC_022476.1 | Direct submission | ||

| Meroptera pravella | 15,260 | NC_035242.1 | [60] | ||

| Hypsopygia regina | 15,212 | NC_030508.1 | Direct submission | ||

| Endotricha consocia | 15,201 | NC_037501.1 | [61] | ||

| Euzophera pyriella | 15,184 | NC_037175.1 | [62] | ||

| Tortricoidea | Tortricidae | Grapholita molesta | 15,717 | NC_014806 | [63] |

| Spilonota lechriaspis | 15,368 | NC_014294 | [64] | ||

| Papilionoidea | Papilionidae | Luehdorfia taibai | 15,553 | KC952673 | [65] |

| Teinopalpus aureus | 15,242 | NC_014398 | Unpublished | ||

| Apatura ilia | 15,242 | NC_016062 | [66] | ||

| Apatura metis | 15,236 | NC_015537 | [67] | ||

| Yponomeutoidea | Plutellidae | Plutella xylostella | 16,179 | JF911819 | [68] |

| Lyonetiidae | Leucoptera malifoliella | 15,646 | NC_018547 | [69] |

Results and discussion

Genomic structure, organization and composition

The complete mitogenome of Orthaga olivacea Warre is a circular molecule with 15,174 base pairs (bp) in size (Fig 1). This is comparable to the mitogenome sizes documented for other sequenced lepidopterans which range from 14,535 bp in Ostrinia nubilalis to 16,179 bp in Plutella xylostella, and it is similar to Lista haraldusalis (15213) (Table 2). The Orthaga olivacea Warre mitogenome is identical to that of other lepidopterans in terms of gene organization, including all 13 PCGs (cox1–3, nad1–6, nad4L, cytb, atp6 and atp8), 22 tRNA genes, two ribosomal RNAs (rrnS and rrnL), and the important non-coding region also known as “A+T-rich region” [70, 71] (Fig 1; Table 3). Variety in non-coding regions is the primarily reason for size differences across Lepidoptera mitochondrial genomes. Nucleotide composition revealed that the most common base is T = 6249 (41.18%) and the least common base is G = 1249 (8.23%) and AT skew [72] (As to Ts) is slightly negative (−0.042). This trend has also been reported from Manduca sexta (−0.005) [34], Ctenoplusia agnata (−0.023) [39], Paracymoriza distinctalis (−0.002) [46], and Lista haraldusalis (−0.007) [57]. In addition, the GC skew (Gs to Cs) is also negative (−0.215). Base composition of the Orthaga olivacea Warre mitogenome is A+T rich (79.02% A+T content and 20.98% G+C content). Highly A+T biased mitogenomes have been previously sequenced from lepidopterans (ranging from 77.8% in Rondotia menciana to 81.94% in Cnaphalocrocis medinalis) [17, 31], (Table 4). Nucleotide skew is negative, similar to the mitogenome of other lepidopterans, such as M. sexta (-0.005 and -0.181) [33] and C.medinalis (-0.030 and -0.175) [17] (Table 4).

Fig 1. Map of the mitogenome of O. olivacea Warre.

Labeling tRNA genes according to the IUPAC-IUB single-letter amino acids: cox1, cox2 and cox3 present the three subunits of cytochrome c oxidase; cob present cytochrome b; nad1-nad6 constitutes NADH dehydrogenase; rrnL and rrnS refer to ribosomal RNAs. Genes named above the bar are located on major strand, while the others are located on minor strand. Anti-clockwise rRNA or PCGs genes are located on L strand and others are located on H strand.

Table 3. Summary results for characteristics of the mitogenome of Orthaga olivacea Warre.

| Gene | Location | Direction | Size | Intergenic Nucleotides | Start codon | Stop codon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tRNA-Met | 1–67 | F | 67 | 1 | — | — |

| tRNA-Ile | 69–132 | F | 64 | -3 | — | — |

| tRNA-Gln | 130–198 | R | 69 | 52 | — | — |

| ND2 | 251–1264 | F | 1014 | 0 | ATT | TAA |

| tRNA-Trp | 1265–1332 | F | 68 | -8 | — | — |

| tRNA-Cys | 1325–1394 | R | 70 | 4 | — | — |

| tRNA-Tyr | 1399–1464 | R | 66 | 3 | — | — |

| COX1 | 1468–2973 | F | 1506 | 0 | CGA | TAA |

| tRNA-Leu1 | 2974–3040 | F | 67 | 0 | — | |

| COX2 | 3041–3712 | F | 672 | 0 | ATT | TAA |

| tRNA-Sup | 3713–3781 | F | 69 | 4 | — | — |

| tRNA-Asp | 3786–3853 | F | 68 | 0 | — | — |

| ATP8 | 3854–4015 | F | 162 | -7 | ATC | TAA |

| ATP6 | 4009–4689 | F | 681 | -1 | ATG | TAA |

| COX3 | 4689–5478 | F | 790 | 2 | ATG | T |

| tRNA-Gly | 5481–5548 | F | 68 | 0 | — | — |

| ND3 | 5549–5902 | F | 354 | 12 | ATT | TAA |

| tRNA-Ala | 5915–5980 | F | 66 | 0 | — | — |

| tRNA-Arg | 5981–6044 | F | 64 | 2 | — | — |

| tRNA-Asn | 6047–6112 | F | 66 | 3 | — | — |

| tRNA-Ser1 | 6116–6168 | F | 53 | 19 | — | — |

| tRNA-Glu | 6188–6253 | F | 66 | -2 | — | — |

| tRNA-Phe | 6252–6318 | R | 67 | 0 | — | — |

| ND5 | 6319–8052 | R | 1734 | 0 | ATT | TAA |

| tRNA-His | 8053–8118 | R | 66 | 0 | — | — |

| ND4 | 8119–9455 | R | 1337 | 0 | ATA | TA |

| ND4L | 9456–9746 | R | 291 | 2 | ATG | TAA |

| tRNA-Thr | 9749–9812 | F | 64 | 0 | — | — |

| tRNA-Pro | 9813–9877 | R | 65 | 0 | — | — |

| ND6 | 9878–10398 | F | 521 | 9 | ATA | TAA |

| CYTB | 10408–11566 | F | 1159 | -2 | ATG | T |

| tRNA-Ser2 | 11565–11631 | F | 67 | 20 | — | — |

| ND1 | 11652–12577 | R | 926 | 1 | ATG | TA |

| tRNA-Leu2 | 12579–12648 | R | 70 | 0 | — | — |

| rRNA-16s | 12649–14032 | R | 1384 | 0 | — | — |

| tRNA-Val | 14033–14096 | R | 64 | 0 | — | — |

| rRNA-12s | 14097–14881 | R | 785 | 0 | — | — |

| A-T-rich region | 14882–15174 | F | 293 | — | — |

Table 4. Composition and skewness in different Lepidopteran mitogenomes.

| Species | Size (bp) | A% | G% | T% | C% | A+T % | ATskewness | GCskewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole genome | ||||||||

| O. olivacea Warre | 15174 | 37.83 | 8.23 | 41.18 | 12.75 | 79.02 | −0.042 | −0.215 |

| B. mori | 15643 | 43.05 | 7.32 | 38.27 | 11.36 | 81.32 | 0.051 | −0.216 |

| R. menciana | 15301 | 41.42 | 7.82 | 37.45 | 13.31 | 78.86 | 0.050 | −0.259 |

| M. sexta | 15516 | 40.67 | 7.46 | 41.11 | 10.76 | 81.79 | −0.005 | −0.181 |

| E. pseudoconspersa | 15461 | 40.42 | 7.61 | 39.51 | 12.46 | 79.93 | 0.011 | −0.241 |

| C. agnata | 15261 | 39.58 | 7.71 | 41.52 | 11.2 | 81.1 | −0.023 | −0.184 |

| A. cinerarium | 15722 | 41.51 | 7.80 | 39.32 | 11.37 | 80.83 | 0.027 | −0.186 |

| D. saccharalis | 15490 | 40.87 | 7.42 | 39.15 | 12.56 | 80.02 | 0.021 | −0.258 |

| C. medinalis | 15388 | 40.36 | 7.45 | 41.58 | 10.61 | 81.94 | −0.030 | −0.175 |

| 1P. distinctalis | 15354 | 41.04 | 7.49 | 41.22 | 10.24 | 82.27 | −0.002 | −0.155 |

| L. haraldusalis | 15213 | 40.47 | 7.66 | 41.04 | 10.83 | 81.52 | −0.007 | −0.172 |

| G. mellonella | 15320 | 38.62 | 7.47 | 41.80 | 12.11 | 80.42 | −0.039 | −0.237 |

| S. lechriaspis | 15368 | 39.86 | 7.63 | 41.34 | 11.17 | 81.19 | −0.018 | −0.188 |

| A. ilia | 15,242 | 39.77 | 7.75 | 40.68 | 11.80 | 80.45 | −0.011 | −0.207 |

| P. xylostella | 16179 | 40.66 | 7.68 | 40.22 | 10.82 | 80.89 | 0.005 | −0.170 |

| PCG | ||||||||

| O. olivacea Warre | 11147 | 37.12 | 9.11 | 40.24 | 13.53 | 77.36 | −0.040 | −0.195 |

| B. mori | 11177 | 42.92 | 8.17 | 36.66 | 12.26 | 79.57 | 0.079 | −0.200 |

| R. menciana | 11225 | 40.97 | 8.58 | 36.12 | 14.33 | 77.1 | 0.063 | −0.251 |

| M. sexta | 11185 | 40.41 | 8.23 | 39.88 | 11.48 | 80.30 | 0.007 | -0.165 |

| E. pseudoconspersa | 11187 | 3969 | 8.43 | 38.3 | 13.58 | 77.99 | 0.017 | −0.233 |

| C. agnata | 11238 | 39.12 | 8.37 | 40.79 | 11.72 | 79.91 | −0.020 | −0.166 |

| A. cinerarium | 11227 | 40.63 | 8.78 | 38.19 | 12.39 | 78.83 | 0.031 | −0.171 |

| D. saccharalis | 11206 | 40.34 | 8.27 | 37.55 | 13.83 | 77.90 | 0.036 | −0.252 |

| C. medinalis | 11210 | 39.88 | 8.15 | 40.69 | 11.28 | 80.56 | −0.010 | −0.161 |

| P. distinctalis | 11189 | 40.54 | 8.12 | 40.53 | 10.81 | 81.07 | 0 | −0.142 |

| L. haraldusalis | 11193 | 39.88 | 8.47 | 40.16 | 11.49 | 80.04 | −0.003 | −0.151 |

| G. mellonella | 11196 | 38.03 | 8.20 | 40.84 | 12.92 | 78.88 | −0.036 | −0.224 |

| S. lechriaspis | 11256 | 39.30 | 8.35 | 40.41 | 11.93 | 79.72 | −0.014 | −0.177 |

| A. ilia | 11,148 | 39.41 | 8.41 | 39.49 | 12.69 | 78.89 | −0.001 | −0.203 |

| P. xylostella | 11049 | 40.47 | 8.82 | 38.85 | 11.86 | 79.32 | 0.020 | −0.147 |

| tRNA | ||||||||

| O. olivacea Warre | 1452 | 39.461 | 8.26 | 40.70 | 11.57 | 80.17 | −0.015 | −0.167 |

| B. mori | 1468 | 42.10 | 7.90 | 39.31 | 10.69 | 81.40 | 0.034 | −0.150 |

| R. menciana | 1485 | 41.08 | 8.08 | 39.93 | 10.91 | 81.01 | 0.014 | −0.149 |

| M. sexta | 1554 | 40.99 | 7.92 | 41.06 | 10.04 | 82.05 | −0.001 | −0.118 |

| E. pseudoconspersa | 1466 | 41.41 | 8.19 | 40.18 | 10.23 | 81.58 | 0.015 | −0.111 |

| C. agnata | 1477 | 41.23 | 8.19 | 40.22 | 10.36 | 81.45 | 0.012 | −0.117 |

| A. cinerarium | 1483 | 42.01 | 8.02 | 39.45 | 10.52 | 81.46 | 0.031 | −0.135 |

| D. saccharalis | 1478 | 41.81 | 7.713 | 40.32 | 10.15 | 82.14 | 0.018 | −0.136 |

| C. medinalis | 1475 | 41.29 | 8.00 | 40.81 | 9.90 | 82.10 | 0.006 | −0.106 |

| P. distinctalis | 1536 | 42.19 | 8.14 | 39.78 | 9.9 | 81.97 | 0.029 | −0.098 |

| L. haraldusalis | 1451 | 41.08 | 7.86 | 41.42 | 9.65 | 82.49 | −0.004 | −0.102 |

| G. mellonella | 1489 | 40.09 | 8.06 | 40.90 | 10.95 | 80.51 | −0.010 | −0.152 |

| S. lechriaspis | 1450 | 40.97 | 8.00 | 40.90 | 10.14 | 81.86 | 0.001 | −0.118 |

| A. ilia | 1433 | 40.61 | 8.30 | 40.96 | 10.12 | 81.58 | −0.004 | −0.099 |

| P. xylostella | 1468 | 42.51 | 8.17 | 38.83 | 10.49 | 81.34 | 0.045 | −0.124 |

| rRNA | ||||||||

| O. olivacea Warre | 2169 | 39.65 | 4.84 | 44.35 | 11.16 | 84.00 | −0.056 | −0.389 |

| B. mori | 2158 | 43.74 | 4.59 | 41.06 | 10.61 | 84.80 | 0.032 | −0.396 |

| R. menciana | 2147 | 43.04 | 4.84 | 40.71 | 11.41 | 83.74 | 0.028 | −0.404 |

| M. sexta | 2168 | 41.37 | 4.84 | 44.05 | 9.73 | 85.42 | −0.031 | −0.335 |

| E. pseudoconspersa | 2225 | 42.56 | 4.54 | 42.11 | 10.79 | 84.67 | 0.005 | −0.408 |

| C. agnata | 2112 | 40.01 | 5.07 | 44.65 | 10.27 | 84.66 | −0.055 | −0.339 |

| A.cinerarium | 2179 | 43.97 | 4.77 | 41.17 | 10.10 | 85.13 | 0.033 | −0.358 |

| D. saccharalis | 2193 | 41.45 | 6.84 | 43.59 | 10.17 | 85.04 | −0.025 | −0.360 |

| C. medinalis | 2170 | 41.47 | 5.02 | 43.87 | 9.63 | 85.35 | −0.028 | −0.314 |

| P. distinctalis | 2174 | 41.31 | 5.34 | 44.02 | 9.34 | 85.33 | −0.032 | −0.272 |

| L. haraldusalis | 2121 | 42.20 | 4.67 | 43.33 | 9.81 | 85.53 | −0.013 | −0.355 |

| G. mellonella | 2143 | 40.18 | 4.95 | 44.19 | 10.69 | 84.37 | −0.048 | −0.367 |

| S. lechriaspis | 2160 | 41.71 | 4.95 | 43.84 | 9.49 | 85.56 | −0.025 | −0.314 |

| A. ilia | 2109 | 40.11 | 4.98 | 44.86 | 10.05 | 84.97 | −0.056 | −0.337 |

| P. xylostella | 2162 | 41.44 | 4.90 | 43.94 | 9.71 | 85.38 | −0.029 | −0.329 |

| A+T-rich region | ||||||||

| O. olivacea Warre | 293 | 44.03 | 2.73 | 49.83 | 3.41 | 93.86 | −0.062 | −0.111 |

| B. mori | 449 | 44.69 | 1.60 | 50.70 | 3.00 | 95.39 | −0.063 | −0.304 |

| R. menciana | 357 | 43.7 | 3.36 | 47.34 | 5.6 | 91.04 | −0.040 | −0.250 |

| M. sexta | 324 | 45.06 | 1.54 | 50.31 | 3.09 | 95.37 | −0.005 | −0.335 |

| E. pseudoconspersa | 388 | 43.56 | 2.32 | 50.26 | 3.87 | 93.81 | −0.071 | −0.250 |

| C. agnata | 334 | 46.71 | 1.5 | 46.71 | 5.09 | 93.41 | 0.000 | −0.545 |

| A. cinerarium | 625 | 47.20 | 1.92 | 48.64 | 2.24 | 95.84 | −0.015 | −0.077 |

| D. saccharalis | 335 | 43.28 | 0.60 | 51.64 | 4.48 | 94.93 | −0.088 | −0.765 |

| C. medinalis | 339 | 42.48 | 0.88 | 53.39 | 3.24 | 95.87 | −0.114 | −0.571 |

| P. distinctalis | 349 | 46.13 | 1.15 | 49 | 3.72 | 95.13 | −0.030 | −0.528 |

| L. haraldusalis | 310 | 45.81 | 0.97 | 50.32 | 2.90 | 96.13 | −0.047 | −0.499 |

| G. mellonella | 350 | 44.29 | 0.29 | 52.86 | 2.57 | 97.14 | −0.088 | −0.8 |

| S. lechriaspis | 441 | 40.36 | 2.49 | 52.38 | 4.76 | 92.74 | −0.130 | −0.313 |

| A. ilia | 403 | 42.93 | 3.23 | 49.63 | 4.22 | 92.56 | −0.072 | −0.133 |

| P. xylostella | 1081 | 37.74 | 2.50 | 45.42 | 5.09 | 83.16 | −0.092 | −0.341 |

Protein-coding genes

The concatenated protein-coding genes are 11,147 bp in length, accounting for approximately 73.46% of the mitogenome. All PCGs are initiated by typical ATN start codons, except cox1, which is initiated by CGA (Table 3). The use of a non-canonical start codon for this gene is common across lepidopterans [17, 37, 73, 74], and cox1 transcripts do not overlap with the upstream tRNA, as has been proposed for several insect species [75]. Annotation of cox1 start codon can be justifiably conducted on the basis of comparative amino acid alignments, aiming to identify conserved sites downstream of the flanking tRNA, and there is thus no justification for continued speculation about polynucleotide start codon [76].

Nine PCGs have canonical termination codons TAA or TAG, while four have incomplete termination codons single T (cox3 and cytb) or TA (nad4 and nad1) (Table 3). Incomplete stop codons have been observed in most other lepidopteran mitogenomes and are common across mitogenomes [77]. It has been proposed that polycistronic pre-mRNA transcripts are processed by endonucleases, cleaving between tRNAs, and that polyadenylation of adjacent PCGs produces functional stop-codons from the partial termination codons such as a single T [78].

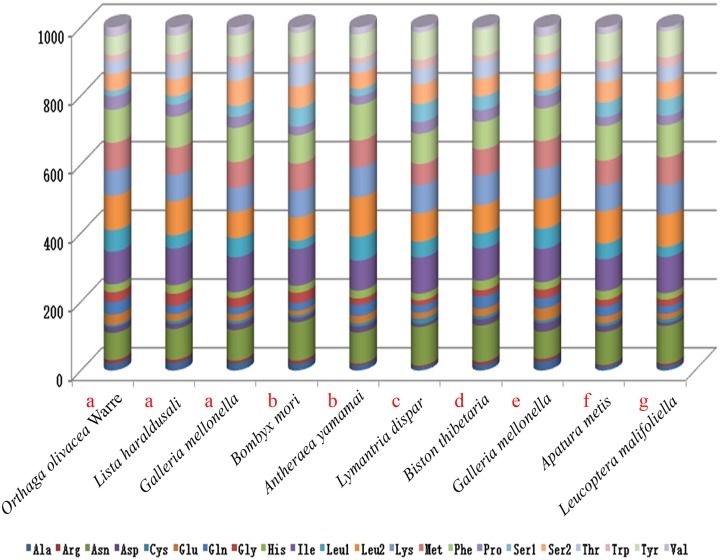

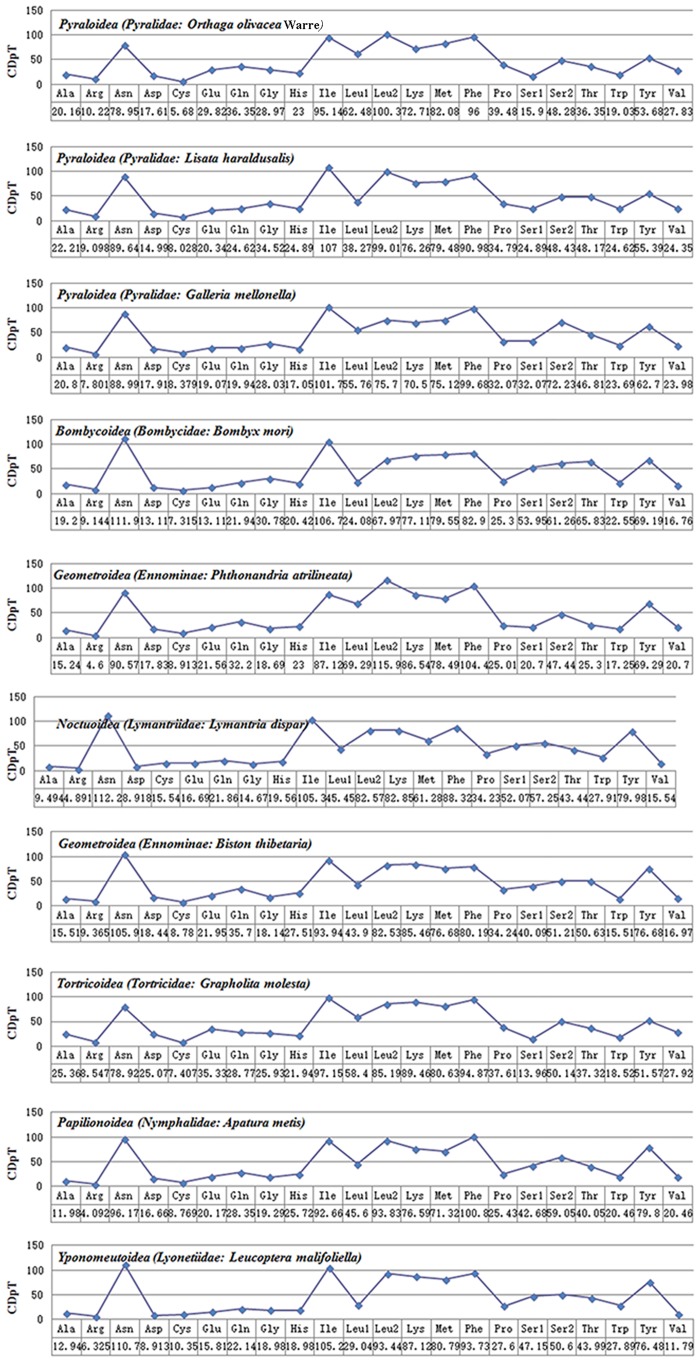

Complete mitogenome sequences of several lepidopterans were evaluated for codon usage. These species belonged to seven superfamilies (three species belonging to Pyraloidea, two species belonging to Bombycoidea, and one from each Noctuoidea, Geometroidea, Tortricoidea, Papilionoidea and Yponomeutoidea) (Fig 2). The analysis of codon usage showed that Asn, Ile, Leu2, Lys, Tyr and Phe were the amino acids with high relative usage frequency, while Arg was the least used amino acid. Three species of Geometroidea have consistent codon distributions in and each amino acid has equal content in them (Fig 3). The least used codons are those with high G and C, possibly due to high AT skew in lepidoptera PCGs [37, 79], for instance, L. haraldusalis, G. mellonella, B. mori, B. thibetaria, and L. malifoliella species all lack GCT codons, while G. molesta lacks CGT codons. However, in the present study all of these codons were observed in the mitogenome of Orthaga olivacea Warre (Fig 4) like that of A. yamamai, L. dispar and A. metis species [33, 67].

Fig 2. Codon usage patterns of O. olivacea Warre mitochondrial genome compared with other species of the Lepidoptera.

The lowercase letters above species name (a, b, c, d, e, f and g) indicate the superfamily which the species belong to (a: Pyraloidea, b: Bombycoidea, c: Noctuoidea, d: Geometroidea, e: Tortricoidea, f: Papilionoidea, g: Yponomeutoidea).

Fig 3. Codon distribution of O. olivacea Warre compared with other species of the Lepidoptera.

CDspT = codons per thousand codons.

Fig 4. The Relative Synonymous Codon Usage (RSCU) of the eight superfamilies mitochondrial genome of Lepidoptera.

Codon family is displayed on the X axis. Codons which are not present in mitochondrial genomes are indicated above.

Transfer and ribosomal RNA genes

Orthaga olivacea Warre mitogenome has 22 tRNA genes, ranging in size from 53 bp (tRNASer1) to 70 bp (tRNACys and tRNALeu). TRNAs show high A+T content (80.17%) and negative AT-skew (−0.015). All the tRNAs display typical cloverleaf secondary structures, except trnSAGN which is missing a stable dihydrouridine (DHU) arm (Fig 5); this phenomenon is common across insects [17, 80, 81].

Fig 5. Putative secondary structures of the 22 tRNA genes of the Orthaga olivacea Warre mitogenome.

The rRNAs showed higher A+T content (84.00%) in comparison to the PCGs and tRNAs; this value falls within the range of sequenced insects (Table 4).

Overlapping and intergenic spacer regions

Six overlapping sequences with a total length of 23 bp were identified in the Orthaga olivacea Warre mitogenome. These sequences varied in length from 1 to 8 bp, and between tRNATrp and tRNACys with the biggest overlapping region (8 bp). The overlapping region located between atp8 and atp6 was 7 bp, 3 bp between tRNAIle and tRNAGln, while the remainders were shorter than 3 bp (Table 3). The 7 bp overlapping region “ATGATAA” (Fig 6B) has also been documented in several lepidopterans sequenced to date [82, 83].

Fig 6. Conserved sequence across the Lepidoptera order.

(A) Intergenic spacer region alignment between trnS2 (UCN) and ND1 of several Lepidopterans. The framework ‘ATACTAA’ motif is conserved across the Lepidoptera order. (B) Intergenic overlap region alignment between ATP8 and ATP6 of several Lepidopterans. The bold ‘ATGATAA’ motif is the overlap region and it’s conserved across the Lepidoptera order. (C) Features present in the A+T-rich region of Orthaga olivacea Warre. The sequence is shown in the reverse strand. The ATAGA motif is bolded. The poly-T stretch is underlined. The single microsatellite T/A repeat sequence are double underlined.

The intergenic spacers of Orthaga olivacea Warre mitogenomes spread over fourteen regions and ranged in size from 1 to 52 bp with a total length of 134 bp. The longest intergenic spacer (52 bp) resided between tRNAGln and nad2. The 20 bp intergenic spacer region located between tRNASer2 and nad1 contained the ‘ATACTAA’ motif. The 7 bp motif is considered to be a conserved structure found in most of the insect mtDNAs (Fig 6A).

The A+T-rich region

The mitogenome of Orthaga olivacea Warre includes an A+T-rich region of 293 bp. This region showed the highest A+T content (93.86%), within the range reported of other lepidopterans (Table 4). Variation in intergenic length of noncoding regions particularly repeat sequences is responsible for most size variation in mitogenome. The control region is usually the largest noncoding part in the mitogenome [84, 85]. Several conserved structures found in other lepidopteran mitogenomes were also observed in the AT-rich region of Orthaga olivacea Warre, including the ‘ATAGA’ motif followed by a 17 bp poly-T stretch, and a microsatellite-like (AT)13 reapeat [86, 87] (Fig 6C).

Above all, there are many remarkable characteristics in nucleotide composition. Compared with reported lepidopteran species, these characteristics include the structure of tRNAs and PCGs, A+T rich region and intergenic spacer region share similarities but also some differences. And these differences and similarities between them can be used as potential markers in phylogenetic analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis

We reconstructed the phylogenetic relationships among seven lepidopteran superfamilies using Maximum Likelihood (ML) method based on concatenated nucleotide sequences of the 13 PCGs. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that different species from the same family clustered together (Fig 7). The complete nucleotide sequences of 59 species of Lepidoptera, represent 16 families (Bombycidae, Saturniidae, Sphingidae, Lymantriidae, Erebidae, Notodontidae, Noctuidae, Nolidae, Geometridae, Crambidae, Pyralidae, Tortricidae, Papilionidae, Nymphalidae, Plutellidae, and Lyonetiidae) were downloaded from GenBank to reconstruct phylogenetic relationships among them. The species Orthaga olivacea Warre belonging to the superfamily Pyralidae, and the relationship were closer with Hypsopygia regina than that with Galleria mellonella and Corcyra cephalonica. Phylogenetic analyses showed that Pyraloidea is clustered with other superfamilies including Bombycoidea, Geometroidea, Noctuoidea, Papilionoidea, Tortricoidea, and Yponomeutoidea. Of these Bombycoidea and Geometroidea were sister groups, and the relationgship of them were closer than Noctuoidea in ML analysis (Fig 7). In the present study, the relationships at superfamily level are consistent with prior studies of lepidopteran phylogeny [88–90]. Previous classifications of Pyralidae species were mostly based on morphology, of which numerous studies are regionally limited; therefore, the precise position of Pyralidae within the Pyraloidea remained unclear, more studies are needed on the complete mitochondrial genome of the diverse Pyraloidea species in order to understand the complexity of phylogenetic relationships.

Fig 7. Phylogenetic relationships tree among Lepidopteran insects.

The Maximum Likelihood method was used in the tree constructing. Bootstrap values (1000 repetitions) of the branches are indicated. Limnephilus hyalinus (NC_044710.1), Drosophila incompta (NC_025936) and Locusta migratoria (JN858212) were used as outgroups.

Conclusion

The newly accessible mitogenome of Orthaga olivacea Warre (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) is 15,174 bp long, including 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), two rRNA genes, 22 tRNA genes and an A+T-rich region. The arrangement of 13 PCGs is same to that of other sequenced lepidopterans. All PCGs of the mitogenome start with typical ATN codons, except for cytochrome c oxidase 1 (cox1) with the start codon CGA. The canonical termination codon (TAA or TAG) occurs in nine PCGs (TAA for nad2, cox1, cox2, atp8, atp6, nad3, nad5, nad4L and nad6 genes), and the remainders PCGs were terminated with a single T or TA (a single T for cox3 and cytb genes, TA for nad4 and nad1 genes). Phylogenetic analysis suggested that Orthaga olivacea Warre is more closely related to the Lista haraldusalis, and confirms that Orthaga olivacea Warre belongs to the family Pyralidae.

Data Availability

All sequences date files are available from the GenBank at NCBI database (accession number mitochondrion MN078362).

Funding Statement

GQW was supported by the grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31472147) the earmarked fund for Anhui International Joint Research and Development Center of Sericulture Resources Utilization (2017R0101). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jiang ST, Hong GY, Yu M, Li N, Yang Y, Liu YQ, et al. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of the giant silkworm moth, Eriogyna pyretorum (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae). Int J Biol Sci. 2009;5(4):351–65. 10.7150/ijbs.5.351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boore JL. Animal mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(8):1767–80. 10.1093/nar/27.8.1767 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolstenholme DR. Animal mitochondrial DNA: structure and evolution. International Review of Cytology. 1992;141(6):173 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62066-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron SL. Insect Mitochondrial Genomics: Implications for Evolution and Phylogeny. Annu Rev Entomol. 2014;59:95–117. 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taanman JW. The mitochondrial genome: structure, transcription, translation and replication. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1999;1410(2):103–23. 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00161-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang DX, Hewitt G.M.,. Insect mitochondrial control region: a review of its structure, evolution and usefulness in evolutionary studies. Biochem Syst Evol. 1997;25:99–120. 10.1016/s0305-1978(96)00042-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae JS, Kim I, Sohn HD, Jin BR. The mitochondrial genome of the firefly, Pyrocoelia rufa: complete DNA sequence, genome organization, and phylogenetic analysis with other insects. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;32(3):978–85. 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowton M, Castro LR, Austin AD. Mitochondrial gene rearrangements as phylogenetic characters in the invertebrates: the examination of genome ‘morphology’. Invertebrate Systematics. 2002;16(3):345–56. 10.1071/IS02003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saccone C, De GC, Gissi C, Pesole G, Reyes A. Evolutionary genomics in Metazoa: the mitochondrial DNA as a model system. Gene. 1999;238(1):195–209. 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00270-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miya M, Kawaguchi A, Nishida M. Mitogenomic exploration of higher teleostean phylogenies: a case study for moderate-scale evolutionary genomics with 38 newly determined complete mitochondrial DNA sequences. Molecular Biology & Evolution. 2001;18(11):1993–2009. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forstén A. Mitochondrial-DNA time-table and the evolution of Equus: comparison of molecular and paleontological evidence. Annales Zoologici Fennici. 1991;28(3/4):301–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayasaka K, Gojobori T, Horai S. Molecular phylogeny and evolution of primate mitochondrial DNA. Molecular Biology & Evolution. 1988;5(6):626 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avise JC, Arnold J, Ball RM, Bermingham E, Lamb T, Neigel JE, et al. Intraspecific Phylogeography: The Mitochondrial DNA Bridge Between Population Genetics and Systematics. Annual Review of Ecology & Systematics. 1987;18(X):489–522. 10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.002421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ort BS, Pogson GH. Molecular population genetics of the male and female mitochondrial DNA molecules of the California sea mussel, Mytilus californianus. Genetics. 2007;177(2):1087 10.1534/genetics.107.072934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hao JS, Sun QQ, Zhao HB, Sun XY, Gai YH, Yang Q. The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Ctenoptilum vasava (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae: Pyrginae) and Its Phylogenetic Implication. Comp Funct Genom. 2012;2012(3):328049 10.1155/2012/328049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coates BS, Sumerford DV, Hellmich RL. Geographic and voltinism differentiation among North American Ostrinia nubilalis (European corn borer) mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase haplotypes. J Insect Sci. 2004;4(1):35 10.1673/031.004.3501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chai HN, Du YZ, Zhai BP. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genomes of Cnaphalocrocis medinalis and Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8(4):561–79. 10.7150/ijbs.3540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Q, Jiang X, Hou X, Hong Y, Chen W. The mitochondrial genome of Ephestia elutella (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2018;3(1):189–90. 10.1080/23802359.2018.1436993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei SJ, Xu FL, Hua FL, Lu JD, Zhang CG, Chen XX. A camphor insect pest——bionomics of Orthaga olivacea. Chinese Bulletin of Entomology. 2008;45(4):562–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen HL. A Differentiation on Orthaga olivacea and Orthaga achatina [J]. Journal of Zhejiang Forestry College, 1994;11(2):218–21. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang N, Qian B. Preliminary report on control of Orthaga achatina by bio-pesticide [J]. Journal of Zhejiang Forestry Science and Technology, 2004;24(6):24–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(5):955–64. 10.1093/nar/25.5.955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, et al. Clustal W and clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(21):2947–8. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junqueira ACM, Lessinger AC, Torres TT, da Silva FR, Vettore AL, Arruda P, et al. The mitochondrial genome of the blowfly Chrysomya chloropyga (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Gene. 2004;339:7–15. 10.1016/j.gene.2004.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–9. 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(2):573–80. 10.1093/nar/27.2.573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Baeity H, Allard LS, Arreza L, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of the North American pale summer sedge caddisfly Limnephilus hyalinus (Insecta: Trichoptera: Limnephilidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2019;4(1): 413–15. 10.1080/23802359.2018.1547158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flook PK, Rowell CH, Gellissen G. The sequence, organization, and evolution of the Locusta migratoria mitochondrial genome. J Mol Evol. 1995;41(6):928–41. 10.1007/bf00173173 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clary DO, Wolstenholme DR. The mitochondrial DNA molecular of Drosophila yakuba: nucleotide sequence, gene organization, and genetic code. J Mol Evol. 1985;22(3):252–71. 10.1007/bf02099755 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan MH, Yu QY, Xia YL, Dai FY, Liu YQ, Lu C, et al. Characterization of mitochondrial genome of Chinese wild mulberry silkworm, Bomyx mandarina (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae). Sci China Ser C. 2008;51(8):693–701. 10.1007/s11427-008-0097-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kong WQ, Yang JH. The complete mitochondrial genome of Rondotia menciana (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae). J Insect Sci. 2015;15(1):48 10.1093/Jisesa/Iev032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu YQ, Li YP, Pan MH, Dai FY, Zhu XW, Lu Cheng, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of the Chinese oak silkmoth, Antheraea pernyi (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae). Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica. 40(8):693–703 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SR, Kim MI, Hong MY, Kim KY, Kang PD, Hwang JS, et al. The complete mitogenome sequence of the Japanese oak silkmoth, Antheraea yamamai (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae). Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36(7):1871–80. 10.1007/s11033-008-9393-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cameron SL, Whiting MF. The complete mitochondrial genome of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta, (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Sphingidae), and an examination of mitochondrial gene variability within butterflies and moths. Gene. 2008;408(2):112–23. 10.1016/j.gene.2007.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim MJ, Choi SW, Kim I. Complete mitochondrial genome of the larch hawk moth, Sphinx morio (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). Mitochondr DNA. 2013;24(6):622–4. 10.3109/19401736.2013.772155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong WW, Dong SY, Jiang GF, Huang GH. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of tea tussock moth, Euproctis pseudoconspersa (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) and its phylogenetic implications. Gene. 2016;577(1):37–46. 10.1016/j.gene.2015.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu HF, Su TJ, Luo AR, Zhu CD, Wu CS. Characterization of the Complete Mitochondrion Genome of Diurnal Moth Amata emma (Butler) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) and Its Phylogenetic Implications. Plos One. 2013;8(9):e72410 10.1371/journal.pone.0072410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salvato P, Simonato M, Battisti A, Negrisolo E. The complete mitochondrial genome of the bag-shelter moth Ochrogaster lunifer (Lepidoptera, Notodontidae). Bmc Genomics. 2008;9(1):331 10.1186/1471-2164-9-331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong YJ, Wu QL, Wei SJ. Complete mitogenome of the Argyrogramma agnata (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Mitochondr DNA. 2013;24(4):391 10.3109/19401736.2013.763241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu QL, Cui WX, Wei SJ. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of the black cutworm Agrotis ipsilon (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Mitochondr DNA. 2015;26(1):139–40. 10.3109/19401736.2013.815175 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang X, Cameron SL, Lees DC, Xue D, Han H. A mitochondrial genome phylogeny of owlet moths (Lepidoptera: Noctuoidea), and examination of the utility of mitochondrial genomes for lepidopteran phylogenetics. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2015;85:230–7. 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.02.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu SX, Xue DY, Cheng R, Han HX. The complete mitogenome of Apocheima cinerarius (Lepidoptera: Geometridae: Ennominae) and comparison with that of other lepidopteran insects. Gene. 2014;547(1):136–44. 10.1016/j.gene.2014.06.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chai HN, Du YZ, Zhai BP. Characterization of the Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Cnaphalocrocis medinalis and Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8(4):561–79. 10.7150/ijbs.3540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li WW, Zhang XY, Fan ZX, Yue BS, Huang FN, King E, et al. Structural Characteristics and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Mitochondrial Genome of the Sugarcane Borer, Diatraea saccharalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). DNA Cell Biol. 2011;30(1):3–8. 10.1089/dna.2010.1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coates BS, Sumerford DV, Hellmich RL, Lewis LC. Partial mitochondrial genome sequences of Ostrinia nubilalis and Ostrinia furnicalis. Int J Biol Sci. 2005;1(1):13–8. 10.7150/ijbs.1.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye F, You P. The complete mitochondrial genome of Paracymoriza distinctalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Mitochondrial Dna A Dna Mappseq Anal. 2014;27(1):28–9. 10.3109/19401736.2013.869678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, Li PF, You P. The complete mitochondrial genome of Tyspanodes hypsalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Mitochondr DNA Part A. 2016;27(3):1821–2. 10.3109/19401736.2014.971241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye F, Shi Y, Xing L, Yu H, You P. The complete mitochondrial genome of\\r Paracymoriza prodigalis\\r (Leech, 1889) (Lepidoptera), with a preliminary phylogenetic analysis of Pyraloidea. Aquatic Insects. 35(3–4):71–88. 10.1080/01650424.2014.948456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park JS, Kim MJ, Kim S-S, Kim I. Complete mitochondrial genome of an aquatic moth, Elophila interruptalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Mitochondr DNA. 2014;25(4):275–7. 10.3109/19401736.2013.800504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cao SS, Du YZ. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Chilo auricilius and comparison with three other rice stem borers. Gene. 2014;548(2):270–6. 10.1016/j.gene.2014.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Min T, Tan M, Meng G, Yang S, Xu S, Liu S, et al. Multiplex sequencing of pooled mitochondrial genomes—a crucial step toward biodiversity analysis using mito-metagenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(22):e166 10.1093/nar/gku917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park JS, Min JK, Ahn SJ, Kim I. Complete mitochondrial genome of the grass moth Glyphodes quadrimaculalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Mitochondr DNA. 2013;26(2):247–9. 10.3109/19401736.2013.823183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He SL, Yuan Z, Li-Fang Z, Wen-Qi M, Xiu-Yue Z, Bi-Song Y, et al. The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of the Beet Webworm, Spoladea recurvalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) and Its Phylogenetic Implications. Plos One. 2015;10(6):e0129355 10.1371/journal.pone.0129355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu QL, Gong YJ, Shi BC, Gu Y, Wei SJ. The complete mitochondrial genome of the yellow peach moth Dichocrocis punctiferalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Mitochondr DNA. 2012;24(2):105–7. 10.3109/19401736.2012.726621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zou Y, Ma W, Zhang L, He S, Zhang X, Tao Z. The complete mitochondrial genome of the bean pod borer, Maruca testulalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae: Spilomelinae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 2016;27(1):740–1. 10.3109/19401736.2014.913167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen S, Li FH, Lan XE, You P. The complete mitochondrial genome of Pycnarmon lactiferalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2016;1(1):638–9. 10.1080/23802359.2016.1214551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ye F, Yu HL, Li PF, You P. The complete mitochondrial genome of Lista haraldusalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Mitochondr DNA. 2015;26(6):853–4. 10.3109/19401736.2013.861427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu YP, Li J, Zhao JL, Su TJ, Luo AR. The complete mitochondrial genome of the rice moth, Corcyra cephalonica. J Insect Sci. 2012;12(72). 10.1673/031.012.7201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang Z, Shen Q-Q. The complete mitochondrial genome of the navel orangeworm Amyelois transitella (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Mitochondr DNA Part A. 2016;27(6):4561–2. 10.3109/19401736.2015.1101564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Consortium LPM, Peterson CS, M JM. The complete mitochondrial genome of the lesser aspen webworm moth Meroptera pravella (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2017;2(1):344–6. 10.1080/23802359.2017.1334525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu WB, Yan J, Song JR, You P. The first mitochondrial genomes for Pyralinae (Pyralidae) and Glaphyriinae (Crambidae), with phylogenetic implications of Pyraloidea. Plos One. 2018;13(3):e0133068 10.1371/journal.pone.0194672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang ML, Feng SQ, Gao Y, Han X, Xiong RC, Li ZH. The complete mitochondrial genome of the pear pyralid moth, Euzophera pyriella Yang. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2017;2(1):275–6. 10.1080/23802359.2017.1325338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gong YJ, Shi BC, Kang ZJ, Zhang F, Wei SJ. The complete mitochondrial genome of the oriental fruit moth Grapholita molesta (Busck) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(3):2893–900. 10.1007/s11033-011-1049-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao JL, Zhang YY, Luo AR, Jiang GF, Cameron SL, Zhu CD. The complete mitochondrial genome of Spilonota lechriaspis Meyrick (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38(6):3757–64. 10.1007/s11033-010-0491-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xing LX, Li PF, Wu J, Wang K, You P. The complete mitochondrial genome of the endangered butterfly Luehdorfia taibai Chou (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae). Mitochondr DNA. 2014;25(2):122–3. 10.3109/19401736.2013.800506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen M, Tian LL, Shi QH, Cao TW, Hao JS. Complete mitogenome of the Lesser Purple Emperor Apatura ilia (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Apaturinae) and comparison with other nymphalid butterflies. Zoological research. 2012;33(2):191–201. 10.3724/SP.J.1141.2012.02191 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang M, Nie XP, Cao TW, Wang JP, Li T, Zhang XN, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of the butterfly Apatura metis (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae). Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(6):6529–36. 10.1007/s11033-012-1481-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wei SJ, Shi BC, Gong YJ, Li Q, Chen XX. Characterization of the Mitochondrial Genome of the Diamondback Moth Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) and Phylogenetic Analysis of Advanced Moths and Butterflies. Dna & Cell Biology. 2013;32(4):173–87. 10.1089/dna.2012.1942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu YP, Zhao JL, Su TJ, Li J, Zhu CD. The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Leucoptera malifoliella Costa (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae). Dna & Cell Biology. 2012;31(10):1508–22. 10.1089/dna.2012.1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rand DM. Endotherms, ectotherms, and mitochondrial genome-size variation. J Mol Evol. 1993;37(3):281–95. 10.1007/bf00175505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mcknight ML, Shaffer HB. Large, rapidly evolving intergenic spacer in the mitochondrial DNA of the salamander family Ambystomatidae (Amphibia: Caudata). Molecular Biology & Evolution. 1997;14(11):1167–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Perna NT, Kocher TD. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. J Mol Evol. 1995;41(3):353–8. 10.1007/bf00186547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liao F, Wang L, Wu S, Li YP, Zhao L, Huang GM, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of the fall webworm, Hyphantria cunea (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae). Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6(2):172–86. 10.7150/ijbs.6.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu QN, Zhu BJ, Dai LS, Wang L, Qian C, Wei GQ, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of the common cutworm, Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidade). Mitochondr DNA. 2016;27(1):122–3. 10.3109/19401736.2013.873934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sheffield NC, Song H, Cameron SL, Whiting MF. A comparative analysis of mitochondrial genomes in Coleoptera (Arthropoda: Insecta) and genome descriptions of six new beetles. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25(11):2499–509. 10.1093/molbev/msn198 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cameron SL. How to sequence and annotate insect mitochondrial genomes for systematic and comparative genomics research. Systematic Entomology. 2014;39(3):400–411. 10.1111/syen.12071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ojala D, Merkel C, Gelfand R, Attardi G. The tRNA genes punctuate the reading of genetic information in human mitochondrial DNA. Cell. 1980;22(2):393–403. 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90350-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wich GN, Hummel H, Jarsch M, Bär U, Böck A. Transcription signals for stable RNA genes in Methanococcus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14(6):2459 10.1093/nar/14.6.2459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sun QQ, Sun XY, Wang XC, Gai YH, Hu J, Zhu CD, et al. Complete sequence of the mitochondrial genome of the Japanese buff-tip moth, Phalera flavescens (Lepidoptera: Notodontidae). Genet Mol Res. 2012;11(4):4213–25. 10.4238/2012.September.10.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jiao Y, Hong GY, Wang AM, Cao YZ, Wei ZJ. Mitochondrial genome of the cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and comparison with other Lepidopterans. Mitochondr DNA. 2010;21(5):160–9. 10.3109/19401736.2010.503242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yin J, Wang AM, Hong GY, Cao YZ, Wei ZJ. Complete mitochondrial genome of Chilo suppressalis (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Mitochondr DNA. 2011;22(3):41 10.3109/19401736.2011.605126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu LT, Su BL, Ma JT, et al. A research on biological characteristics and occurrence regularity of semiothisa cinerearia. Jouanal of Jilin agriculture university. 2008;30(8):24–6. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhu BJ, Liu QN, Dai LS, Wang L, Sun Y, Lin KZ, et al. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Diaphania pyloalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralididae). Gene. 2013;527(1):283–91. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.035 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Saito S, Tamura K, Aotsuka T. Replication origin of mitochondrial DNA in insects. Genetics. 2005;171(4):1695–705. 10.1534/genetics.105.046243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oliveira MT, Azeredoespin AML, Lessinger AC. The Mitochondrial DNA Control Region of Muscidae Flies: Evolution and Structural Conservation in a Dipteran Context. J Mol Evol. 2007;64(5):519 10.1007/s00239-006-0099-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim MJ, Wan X, Kim KG, Hwang JS, Kim I. Complete nucleotide sequence and organization of the mitogenome of endangered Eumenis autonoe (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae). Afr J Biotechnol. 2010;9(5):735–54. 10.5897/ajb09.1486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Park JS, Cho Y, Kim MJ, Nam SH, Kim I. Description of complete mitochondrial genome of the black-veined white, Aporia crataegi (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea), and comparison to papilionoid species. J Asia-Pac Entomol. 2012;15(3):331–41. 10.1016/j.aspen.2012.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zheng N, Sun YX, Yang LL, Wu L, Abbas MN, Chen C, et al. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Biston marginata (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) and phylogenetic analysis among lepidopteran insects. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2018;113:961–70. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.02.110 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dai LS, Qian C, Zhang CF, Wang L, Wei GQ, Li J, et al. Characterization of the Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Cerura menciana and Comparison with Other Lepidopteran Insects. Plos One. 2015;10(8):e0132951 10.1371/journal.pone.0132951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sun YX, Wang L, Wei GQ, Qian C, Dai LS, Sun Y, et al. Characterization of the Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Leucoma salicis (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) and Comparison with Other Lepidopteran Insects. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39153 10.1038/srep39153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]