Abstract

Background: Dense breasts on mammography independently increases breast cancer risk and decreases mammography sensitivity. Thirty-two states have adopted notification laws to raise awareness among women with dense breasts about supplemental screening. Little is known about these policies' impact on clinical practice among primary care providers (PCPs).

Materials and Methods: This study explores PCP attitudes, knowledge, and the impact of the Massachusetts dense breast notification legislation on clinical practice after its enactment in 2015. An anonymous, online survey at two urban safety-net hospitals was administered in 2015–2016. Practicing MDs and nurse practitioners in primary care were invited to participate.

Results: All 145 PCPs in general internal medicine at the two sites were e-mailed a survey link and 80 (55%) were completed. While 64 of 80 PCPs surveyed (80%) had some familiarity with the legislation, none identified the 8 required components of notifications contained in the Massachusetts legislation. Forty-nine percent (39/80) did not feel prepared to respond to patient questions about dense breasts. Forty-one percent (33/80) correctly identified that no current guidelines recommend the use of supplemental screening tests solely based on breast density and 85% (68/80) indicated interest in further training. Female and less experienced providers were more likely to be in favor of the legislation (49% vs. 11% by gender; 76% <5 years vs. 9%> 20 years). Women practitioners (55%) who were more likely than men (17%, p = 0.01) to agree with the policy changed their discussions of mammography results with patients.

Conclusions: PCPs feel underprepared to counsel women about breast density identified on mammography and its implications.

Keywords: : breast cancer screening, breast density, health policy, primary care

Introduction

Breast density has garnered attention in recent years, as it may increase risk for developing breast cancer while also reducing the sensitivity of mammography.1,2 Estimates of the increase in risk conferred by the presence of dense breast tissue vary. When comparing screening mammograms with the highest density (extremely dense breasts, ≥75% dense tissue) to those with the lowest density (fatty breasts, <5% or <10% dense tissue), women with the highest density have between a 1.5 and 4.7 increased odds of a breast cancer diagnosis.3–5 The absolute increase in risk, however, is much smaller as density must be taken into consideration with other clinical factors that also contribute to breast cancer risk.6–8 For example, the absolute increase in risk from a woman with no family history of breast cancer, no prior biopsy, and average density compared with a similar woman with extremely dense breast tissue is estimated to be 0.6%.6 In addition, mammography sensitivity decreases by up to 50% among women with extremely dense breasts versus those with mostly fatty breasts.1 As such, density is increasingly being incorporated into clinical assessments of breast cancer risk and discussions about risk with patients.6

Some advocacy groups suggest supplemental imaging for women with dense breast parenchyma to increase the chance that cancers masked by density will be detected before they become symptomatic. Supplemental imaging with breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound (US) after a normal mammogram may reduce the interval cancer rate (rate of cancers detected because of symptoms in the interval between recommended screenings) among women with dense breasts, but these tests also increase false-positive imaging tests and biopsies.3,9 Early detection in this setting is important since interval cancers, or invasive cancer diagnosed within 12 months of a normal mammogram, are associated with more aggressive tumors.10–12 In response to this emerging evidence, a large grassroots movement13 has initiated a series of legislative policies to raise awareness among women with dense breasts as a means to promote informed decision-making about supplemental screening.14

In January 2015, Massachusetts became the 21st state to pass breast density notification legislation. The Massachusetts legislation mandates that women whose mammograms are determined by a radiologist to show “heterogeneously or extremely” dense breasts receive a notification including the following eight required informational components15: (1) that a woman's mammogram displays dense breast tissue; (2) the degree of density and explanation about the given degree of density; (3) that dense breast tissue is common and not abnormal, but may increase one's risk of cancer; (4) that dense breast tissue can make it more difficult to view cancer on a mammogram, rendering the potential need for additional testing to complete reliable breast cancer screening; (5) that supplemental screening tests may be advisable and results of the mammogram should be discussed with a woman's physician or primary care physician; (6) that a woman has the right to discuss the mammogram results with either the interpreting radiologist or referring physician; (7) that a report of the mammogram has been sent to the referring physician and is included as part of the patient's medical record; and (8) where additional information about breast dense tissue can be found.

At this time, 32 states (including Indiana whose law does not explicitly require notification) have passed some form of breast density notification legislation, with additional states considering bills, and discussion of national legislation.16 There is, however, controversy about breast density notification legislation, in large part, due to the lack of professional guidelines to support the use of supplemental screening, which many of these laws endorse. National guidelines from the American Cancer Society do recommend annual screening MRI in high-risk women regardless of breast density,17 but do not recommend supplemental screening with MRI and US in average-risk women with dense breasts.18

In 2016, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) also released updated recommendations for breast cancer screening concluding that current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of the benefits and harms of supplemental screening with US or MRI for women with dense breasts.19 Of note, the USPSTF guideline process prioritizes outcomes from randomized controlled trials, despite evidence that supplemental screening in certain populations with dense breast parenchyma indeed reduces interval cancer rates and increases rates of cancer detection.9,20,21

Experts have raised concerns about the legislation's ability to promote informed decision-making and evidence-based care due to concerns about the subjectivity of density assessment, the potential overreliance on density as a risk factor for cancer, as well the potential for notifications to increase patient anxiety, distress or fear, generate uncompensated imaging costs, or even lead to overdiagnosis.7,22–27

Primary care providers (PCPs), who are at the forefront of decision-making with patients who receive these notifications, are now faced with the challenges inherent in clinical decision-making without sufficient evidence to guide them. Despite the widespread adoption of such legislation, little is known about its impact on clinical practice28–30 and the consequences of the legislation on the PCP have only been minimally explored31 despite many states recommending that women receiving the notification follow up with primary care. Given the limited resources available in primary care, particularly in safety-net settings where providers encounter complex and competing demands, it is imperative that we assess the impact of such legislative initiatives on providers practicing in this setting. Therefore, we conducted a study to describe the perspectives about the breast density legislation among PCPs practicing in two Massachusetts safety-net hospitals (defined as institutions with greater than 25% of their patient population uninsured or covered through Medicaid).

Materials and Methods

This descriptive study aimed to explore provider attitudes, knowledge, and the impact of the Massachusetts dense breast notification legislation on clinical practice after its enactment in January 2015. A cross-sectional survey of PCPs practicing at two academic safety-net hospitals in Boston was administered between August 2015 and March 2016. The IRBs at both institutions determined this study to be exempt.

Survey design and measures

An anonymous, web-based survey consisting of 18 multiple choice Likert and open-ended questions collected information on providers' perspectives on the Massachusetts breast density notification legislation. Provider gender, practice site, and years of practice were the only demographics collected, in an effort to preserve anonymity. Three main domains covering individual attitudes, knowledge, and impact on clinical practice guided survey question design. Table 1 displays each domain and associated questions with response options. Briefly, providers' attitudes and knowledge were captured through three and four questions, respectively. One of the knowledge questions used a clinical vignette format to assess providers' decision-making and knowledge following a finding of dense breasts in a hypothetical patient. Provider perceptions about the impact of the legislation on clinical practice were captured through three questions. Four open-ended questions elicited additional comments and concerns about the legislation, and inquired about what support providers felt was needed to assist them in dealing with issues arising from this new mandate.

Table 1.

Survey Domains and Questions

| Response options | |

|---|---|

| Attitudes | |

| I believe that this policy will promote informed decision-making for my patients. | ○ Strongly disagree ○ Disagree ○ Neither agree nor disagree ○ Agree ○ Strongly agree |

| I am in favor of this policy to inform women of their breast density as part of their mammogram results. | |

| Counseling women about breast density is primarily my responsibility as a primary care physician versus the responsibility of other clinicians or imaging providers. | |

| Impact on Clinical Practice | |

| This policy has affected my clinical practice. | ○ Strongly disagree ○ Disagree ○ Neither agree nor disagree ○ Agree ○ Strongly agree |

| This policy has changed how I discuss mammography results with patients. | |

| I feel prepared to respond to requests from patients who are notified that they have dense breasts. | |

| Knowledge | |

| How familiar are you with the new Massachusetts policy that went into effect in January 2015 that requires mammography providers to notify women if they are found to have dense breasts on mammography? | ○ Very familiar ○ Somewhat familiar ○ Not at all familiar |

| Evidence suggests the following supplemental screening tests may be warranted for women with dense breasts (check all that apply): | ○ Screening US ○ MRI ○ Tomosynthesis (3D mammography) ○ Genetic testing ○ None of the above |

| Scenario question: | |

| Janice is a 60-year-old patient of yours who comes to your office to talk to you about a notification she received in the mail. She recently had her screening mammogram done and received a letter stating that she had “dense breasts” and recommending she discuss supplemental screening with you. She is confused about what this means… What would you recommend for Janice? |

○ US ○ MRI ○ Tomosynthesis (3D mammography) ○ Conduct a breast cancer risk assessment ○ Yearly routine mammogram ○ No additional screening |

| The breast density notification mandate includes several specific components. To the best of your knowledge, which of the following statements are included in the letters provided to women? (check all that apply) | ○ The patient's mammogram showed dense breast tissue ○ The degree of density ○ Dense breast tissue increases the risk of breast cancer ○ Dense breast tissue is common ○ Dense breast tissue can make it more difficult to find cancer on a mammogram ○ Additional screening may be advisable ○ MRI or US is the best means to find potential cancers in dense breasts ○ The patient should discuss results with their primary care physician or the referring physician ○ The patient has a right to discuss results with a radiologist |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; US, ultrasound.

Data collection

We aimed to survey all practicing PCPs (MDs and nurse practitioners) practicing in outpatient general internal medicine practices at two urban academic, safety-net hospitals. Trainees (i.e., residents) were excluded from participation. To garner the highest response rate possible, we enlisted clinical leaders within the divisions (i.e., division/section chiefs, directors of primary care practices) to send out the survey link and encourage participation. An e-mail invitation briefly describing the study's purpose and time requirements was sent to all practicing PCPs in general internal medicine departments from clinical directors at each institution (n = 145). The e-mail included a link to a website where the survey could be completed anonymously (Qualtrics©, Provo, UT). A total of three reminder e-mails over the course of 8 weeks were sent. At each site, a paper version of the survey was also distributed at an in-person meeting (e.g., Grand Rounds) to bolster participation. Paper surveys were combined with electronic data using double entry for quality assurance.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics summarized the distribution of demographic variables within the sample. For each survey question, frequencies and relative frequencies were computed. Likert scale responses representing five levels of agreement were collapsed into three categories: strongly agree/agree, neutral, and strongly disagree/disagree for all analyses. Similarly, when asking how familiar providers were with the legislation (very, somewhat, or not at all), responses were collapsed into dichotomous indicators, grouping “very” and “somewhat” familiar responses. Bivariate statistics were generated to explore differences in responses by gender, the number of years in practice, and practice site using chi-square tests. For these comparisons, Fisher's exact test was used when indicated by small cell sizes. In comparative analyses, we included all responses, and then excluded those with any missing data to test for differences. Tables report the proportion of completed responses. Overall, rates of missing responses were low (one to five participants or 1%–6% across most items). All analyses were completed using SAS® version 9.3, Copyright© 2002–2010 SAS Institute, Inc. (Cary, NC). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Eighty out of 145 invited PCPs completed the survey (55% response rate). As seen in Table 2, the same proportions of providers (65%, 52/80) were female and practiced at site A, while years in clinical practice were widely distributed in this sample (Table 1). Among those who reported complete demographic data (n = 76), the years in clinical practice were distributed similarly for men and women (p = 0.77).

Table 2.

Sample Demographics

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 24 (30) |

| Female | 52 (65) |

| Unknown | 4 (5) |

| Years in clinical practice | |

| <5 | 25 (31) |

| 5–10 | 15 (19) |

| 10–20 | 24 (30) |

| >20 | 13 (16) |

| Unknown | 3 (4) |

| Site | |

| Site A | 52 (65) |

| Site B | 28 (35) |

Knowledge

Overall, the majority of the PCPs (64/80, 80%) stated they were either very or somewhat familiar with the Massachusetts dense breast legislation, whereas 20% (16/80) indicated they were not at all familiar (Table 3). However, when providers were asked to identify the specific mandated elements required to be included in the notification, none (0/80) correctly identified all eight components. A third knowledge item assessed provider awareness of the evidence for supplemental screening in the setting of dense breasts. Correct responses were considered those that indicated “none of the above” on the question that asked if evidence suggests any of the following supplemental screening tests are warranted based on breast density: screening US, MRI, tomosynthesis, or genetic testing. Correct responses to this question were based on available evidence and recommendations for supplemental screening by the USPSTF and American Cancer Society, which do not support the use of supplemental screening in this context.18,19,21 Less than half (41%, 33/80) of respondents correctly identified that no current guidelines recommend the use of these services solely based on a finding of dense breasts.

Table 3.

Provider Perceptions of Dense Breast Legislation and Impact on Clinical Practice

| Yes, n (%)a | No, n (%)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | |||

| I am familiar with dense breast legislation | 64 (80) | 16 (20) | |

| Correctly identified all eight mandate components | 0 (0) | 75 (100) | |

| Aware of evidence for supplemental screening | 33 (41) | 47 (59) | |

| Strongly agree/agree, n (%) | Neutral, n (%) | Strongly disagree/disagree, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | |||

| In favor of this policy | 23 (38) | 14 (23) | 23 (38) |

| Policy will promote informed decision-making | 20 (25) | 29 (37) | 30 (38) |

| Counseling women about breast density is a PCP's responsibility | 34 (43) | 23 (29) | 22 (28) |

| Impact on clinical practice | |||

| Policy has affected my clinical practice | 23 (38) | 15 (25) | 22 (37) |

| Policy has changed how I discuss mammography results with patients | 33 (42) | 23 (29) | 22 (28) |

| Feel prepared to respond to requests from patients about dense breasts | 27 (34) | 13 (16) | 39 (49) |

| How interested are you in future training on how to manage patients with dense breasts? | 68 (85) | 11 (14) | 1 (1) |

Percentages reflect proportion of complete responses.

PCP, primary care providers.

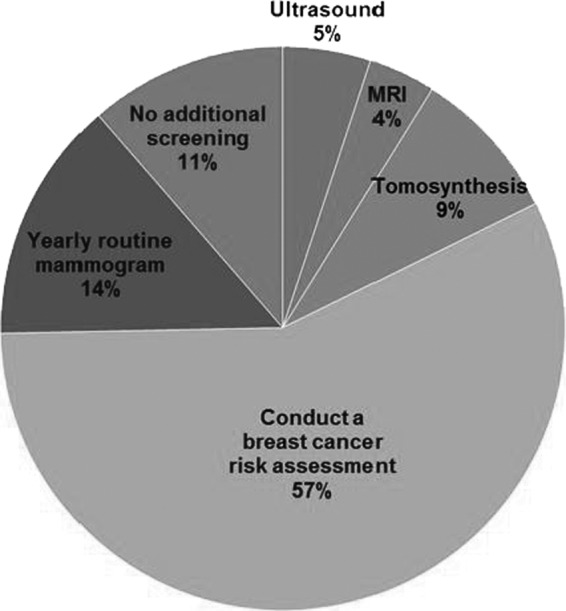

The survey also included a knowledge question in a scenario format, using a hypothetical patient and asking respondents to provide a recommendation for follow-up (see Table 1 for question). Correct answers indicated that providers would conduct a breast cancer risk assessment. As shown in Figure 1, 57% of the providers (46/80) responded correctly, suggesting awareness of the need to consider overall breast cancer risk (not only breast density) in decision-making related to supplemental screening.

FIG. 1.

Provider responses to a scenario-based knowledge question.

Attitudes

Providers' perceptions of the breast density mandate varied (Table 3). The same proportions of providers were in favor of the policy as not (38% each), with the remainder being neutral. Despite the intention of the legislation to promote informed decision-making about breast cancer screening, only 25% of the responding PCPs felt the policy would do so, while the remainder were evenly divided between neutral and perceiving that the policy will not promote informed decisions. Finally, 43% felt counseling women about breast density is a PCP's responsibility, 29% were neutral, and 28% felt it was the responsibility of other clinical specialties (e.g., radiologists, breast health providers).

Impact on clinical practice

When asked whether the policy has changed the discussion of mammography results with patients, 42% (33/80) responded affirmatively, 29% (23/80) responded neutrally, and 28% (22/80) stated their counseling practices had not changed. However, almost half (49%, 39/80) of the PCPs surveyed did not feel prepared to discuss requests from patients about dense breasts. Congruent with these responses, 85% (68/80) responded that they were somewhat or very interested in further training on how to manage women with dense breasts, with only one individual not at all interested in such training.

Responses by gender and years of clinical practice

As seen in Table 4 below, there were statistically significant differences in responses when compared by provider gender and years in clinical practice. A significantly larger percentage of women (49%, 19/39) compared to men (11%, 2/18) were in favor of the mandate (p = 0.03). Sixty-three percent (15/24) of men and 33% of women (17/52) were knowledgeable about the evidence for supplemental screening when asked to identify which tests are warranted for women with dense breasts (p = 0.01). Women practitioners were more likely to agree that the policy has changed the discussion of mammography results with patients compared to men (55%, 28/51 vs. 17%, 4/23; p = 0.01).

Table 4.

Percentage of Strongly Agree or Agree Responses by Gender and Practice Years

| Male (%) | Female (%) | p | <5 Years (%) | 5–10 Years (%) | 10–20 Years (%) | >20 Years (%) | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | ||||||||

| Aware of evidence for supplemental screening | 15 (63) | 17 (33) | 0.01 | 7 (28) | 5 (33) | 15 (63) | 6 (46) | 0.09 |

| I am familiar with dense breast legislation | 16 (67) | 46 (88) | 0.03 | 22 (88) | 11 (83) | 20 (83) | 9 (69) | 0.83 |

| Attitudes | ||||||||

| In favor of this policy | 2 (11) | 19 (49) | 0.02 | 13 (76) | 4 (36) | 4 (21) | 1 (9) | <0.01 |

| Policy will promote informed decision-making | 3 (13) | 16 (31) | 0.26 | 10 (40) | 3 (20) | 4 (17) | 3 (23) | 0.13 |

| Counseling women about breast density is a PCP's responsibility | 8 (33) | 25 (49) | 0.44 | 18 (72) | 6 (40) | 7 (29) | 3 (25) | 0.04 |

| Impact on clinical practice | ||||||||

| Policy has affected my clinical practice | 3 (17) | 20 (51) | 0.05 | 10 (59) | 1 (9) | 8 (42) | 4 (36) | 0.19 |

| Policy has changed how I discuss mammography results with patients | 4 (17) | 28 (55) | 0.01 | 15 (60) | 7 (47) | 6 (27) | 4 (31) | 0.08 |

| Feel prepared to respond to requests from patients about dense breasts | 8 (33) | 19 (37) | 0.92 | 10 (40) | 5 (36) | 6 (25) | 6 (46) | 0.83 |

p-Values for chi-square tests including years of practice variable generated using Fisher's exact test.

All statistically significant values (p < 0.05) appear in bold.

Examining differences in responses by years spent in clinical practice revealed differences along two dimensions. First, length of practice was negatively associated with the attitudes of favorability, with those practicing fewer than 5 years being most likely to be in favor of the policy (13/17, 76% for <5 years decreasing to 1/11, 9% for >20 years; p < 0.01). Second, PCPs with fewer years of experience were more likely to agree that counseling women about breast density is a PCP's responsibility (72%, 18/25) compared with providers practicing 5–10 years (40%, 6/15), 10–20 years (29%, 7/24), and more than 20 years (25%, 3/12; p = 0.04). No significant differences were found by site (data not shown).

Discussion

The results of this survey of general internists in Massachusetts subsequent to passage of the Massachusetts dense breast notification law suggest that providers have limited knowledge about the legislation and few perceive it will have the intended effect of promoting informed decision-making for patients. While most (80%) had at least some familiarity with the legislation, none was able to identify all eight required components of the notification and half of PCPs did not feel prepared to respond to patient questions about dense breasts, with the vast majority indicating interest in further training. Female and less experienced providers were more likely to report being in favor of the legislation and women were more likely to report that it changed their discussions of mammography.

Our findings in Massachusetts are in contrast to studies of PCPs in California.31 While 80% of our providers indicated familiarity with the legislation, 49% of surveyed providers in the California study reported no knowledge of their legislation. This is likely due to the recent proliferation of these laws nationally and the increased attention on available scientific evidence on this topic, which may have alerted providers to the coming changes in 2015 in Massachusetts, whereas California adopted the legislation in 2013. However, these study findings were similar in identifying PCPs' discomfort counseling on this topic and a high desire for further training.

We found that 38% of our providers favored the legislation, similar to another single-institution study of radiologists in Pennsylvania.32 These data suggest that a broad spectrum of providers do not favor the law. This low favorability in our study, combined with only 43% of those surveyed feeling breast density counseling was their responsibility, could suggest that PCPs are wary of policies that increase their workload in light of competing health priorities that must be addressed in a clinic visit, although our data did not directly assess this explanation. Concerns about the increased effort required to appropriately address breast density in a visit may be warranted, as others have documented a lack of systems (e.g., Electronic Health Record decision support) that support breast cancer screening in primary care33 and the need to streamline the supplemental screening process,34 which may be especially true in safety-net settings with fewer supportive resources.

Another potential contributor to providers' lack of support for this legislation is that scientific evidence to support the adoption of supplemental screening is still emerging and controversial,22 so providers have limited tools to guide shared decision-making for women with dense breasts.35 The benefits of supplemental US and/or MRI include higher rates of cancer detection and lower rates of interval cancers.21,36–39 USs find 1.1–7.2 additional breast cancers per 1000 screened, resulting in 0.36 averted deaths, but also incurring 47–354 false positives per 1000 screened individuals.9,20,36,39 Use of supplemental MRI finds an additional 10 cancers per 1000 tests over mammography alone, but has a high false-positive rate of 7%–23% and no established mortality benefit.21,36,38,40,41 However, these tests are associated with additional costs to individuals and the health system, higher rates of false positives resulting in biopsies with associated potential harms, and are a source of emerging concern regarding overdiagnosis of breast cancer.20,38,42 Alternatively, primary screening with tomosynthesis leads to lower rates of recall in women with dense breasts, maintaining high specificity and sensitivity,43 but there is still a paucity of evidence that any of these screening tests leads to improved clinical outcomes,21 unlike mammography.19

While data on outcomes related to supplemental screening and/or alternative primary screening modalities for dense breasts continue to be generated, providers can assist patients in weighing the benefits and risks on an individual basis, helping women choose screening modalities based on their individual risk of developing cancer and personal preferences for more or less screening. Primary care is one possible venue for such discussions, as PCPs generally initiate screening recommendations and referrals. However, it is the responsibility of an array of care providers to ensure shared decision-making in this setting, and thus, a range of specialties should be prepared to engage in these discussions (e.g., radiologists).

Indeed, expert panels around the country advocate for the incorporation of risk assessment and personal preferences into screening decisions to guide informed decision-making about supplemental screening in the setting of dense breasts.24,35,44 However, a prior study of PCPs' attitudes and practices surrounding risk assessment and management found that while providers often elicited a family history of breast cancer (71%), very few ever explicitly calculated risk for individual patients (24%).45 A second study confirmed that PCPs generally limit discussions of breast cancer risk to family and personal history, and are concerned about discussing risk if there are limited options for modifying risk.46

Others have reported that providers indicate a lack of confidence in knowledge of risk and risk assessment as a barrier to more comprehensive discussions of risk, including tailoring screening by risk status.45 These studies are congruent with responses to the scenario knowledge question presented here, where a significant minority of respondents (43%) did not indicate risk assessment as the correct course of action. Building the capacity of PCPs to counsel about breast cancer risk in conjunction with breast density is an important but overlooked complement to these legislative efforts, without which the goals of the legislation will remain unfulfilled.

The differences observed in terms of attitudes and knowledge between genders and years of clinical practice are also consistent with findings from other settings. It is well documented that gender concordance between female physicians and patients is associated with more preventive counseling and testing,47,48 as well as higher levels of patient-centered communication.49 This may, in part, explain why female PCPs in this sample were more likely to be in favor of this legislation and report that it changed their practice, particularly around the discussion of mammography. Providers with fewer years in practice may be more amenable to taking on this counseling responsibility because of an increasing emphasis on informed decision-making in medical education, with the incorporation of skills training such as brief motivational interviewing into medical curricula.50

The intended effect of breast density notification legislation to increase awareness and promote informed decision-making requires activated and informed PCPs. PCPs participating in this survey in Massachusetts indicated they do not feel prepared to counsel their patients with dense breasts. Raising patient awareness about risk factors without an informed clinical workforce has the potential to lead to increased patient anxiety and confusion about the appropriate course of action.

Limitations

These data were collected at two academic safety-net hospitals in one urban area, reflecting the local attitudes and perceptions of the Massachusetts breast density legislation. While our findings are congruent with those from PCPs in other settings,31 they are not representative of all PCPs nationally. The academic center context may have made these providers more likely to be aware of medical evidence, yet the safety-net status of these practices implies they may have fewer resources and see higher acuity patients with complex social and medical needs. These data were collected within 6–10 months after the enactment of the legislation. Changes in perceptions may have occurred over this period, influencing results. Furthermore, longitudinal studies are needed to assess the long-term impact of breast density notification, including the changes in practice over time. Because of our sample size, we are not able to assess whether physician gender or years of practice were the major factors accounting for the differences we identified.

Conclusions

Until well-designed, long-term comparative studies of supplemental screening of women with dense breasts are available to guide clinical practice, dense breast notification laws will prompt mammography providers to alert women in the absence of a sufficient evidence base to guide screening decisions. This study demonstrated that PCPs do not feel prepared to respond to the increasing informational needs of these patients. Further analysis of why PCPs do not support dense breast legislation is needed to understand the impact of such policies. Evidence-based education on how to best counsel women with dense breasts using available risk assessment tools, and appropriate triaging for additional screening and prevention may support PCPs in the states in which breast density legislation has been enacted.

Acknowledgment

Preliminary results of this article were presented at The Society for General Internal Medicine Annual Research Meeting, May 2016, Hollywood, FL.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Mandelson MT, Oestreicher N, Porter PL, et al. Breast density as a predictor of mammographic detection: Comparison of interval- and screen-detected cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1081–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:673–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2007;356:227–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:1159–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pettersson A, Graff RE, Ursin G, et al. Mammographic density phenotypes and risk of breast cancer: A meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:pii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tice JA, Cummings SR, Smith-Bindman R, Ichikawa L, Barlow WE, Kerlikowske K. Using clinical factors and mammographic breast density to estimate breast cancer risk: Development and validation of a new predictive model. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:337–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haas JS, Kaplan CP. The divide between breast density notification laws and evidence-based guidelines for breast cancer screening: Legislating practice. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1439–1440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engmann NJ, Golmakani MK, Miglioretti DL, Sprague BL, Kerlikowske K; for the Breast Cancer Surveillance C. Population-attributable risk proportion of clinical risk factors for breast cancer. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1228–1236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg WA, Blume JD, Cormack JB, et al. Combined screening with ultrasound and mammography vs mammography alone in women at elevated risk of breast cancer. JAMA 2008;299:2151–2163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porter PL, El-Bastawissi AY, Mandelson MT, et al. Breast tumor characteristics as predictors of mammographic detection: Comparison of interval- and screen-detected cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:2020–2028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drukker CA, Schmidt MK, Rutgers EJT, et al. Mammographic screening detects low-risk tumor biology breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014;144:103–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nederend J, Duijm LEM, Louwman MWJ, et al. Impact of the transition from screen-film to digital screening mammography on interval cancer characteristics and treatment—A population based study from the Netherlands. Eur J Cancer 2014;50:31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Are you Dense Advocacy, Inc. 2016. D.E.N.S.E. State Efforts. Available at: http://areyoudenseadvocacy.org Accessed November15, 2016

- 14.Cappello NM. Decade of “normal” mammography reports—The happygram. J Am Coll Radiol 2013;10:903–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.An Act Relative to Breast Cancer Early Detection. House No 3733. United States of America, The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dense Breast Info, Inc. 2017. Legislation and Regulations—What is Required? Available at: http://densebreast-info.org/legislation.aspx# Accessed May30, 2017

- 17.Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin 2007;57:75–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA 2015;314:1599–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siu AL. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:279–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parris T, Wakefield D, Frimmer H. Real world performance of screening breast ultrasound following Enactment of Connecticut Bill 458. Breast J 2013;19:64–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melnikow J, Fenton JJ, Whitlock EP, et al. Supplemental screening for breast cancer in women with dense breasts: A systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:268–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slanetz PJ, Freer PE, Birdwell RL. Breast-density legislation—Practical considerations. N Engl J Med 2015;372:593–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall FM. Breast density categorization creep. Radiology 2014;271:927–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhodes D, Conners A. Breast density legislation. Implications for patients and primary care providers. Minn Med 2014;97:43–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ray KM, Price ER, Joe BN. Breast density legislation: Mandatory disclosure to patients, alternative screening, billing, reimbursement. Am J Roentgenol 2015;204:257–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcus EN. The conundrum of explaining breast density to patients. Cleve Clin J Med 2013;80:761–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dolan NC, Goel M. It's not all about breast density: Risk matters. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:729–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhodes DJ, Breitkopf CR, Ziegenfuss JY, Jenkins SM, Vachon CM. Awareness of breast density and its impact on breast cancer detection and risk. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1143–1150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manning M, Purrington K, Penner L, Duric N, Albrecht TL. Between-race differences in the effects of breast density information and information about new imaging technology on breast-health decision-making. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:1002–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nayak L, Miyake KK, Leung JWT, et al. Impact of breast density legislation on breast cancer risk assessment and supplemental screening: A survey of 110 radiology facilities. Breast J 2016;22:493–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khong KA, Hargreaves J, Aminololama-Shakeri S, Lindfors KK. Impact of the California breast density law on primary care physicians. J Am Coll Radiol 2015;12:256–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gur D, Klym AH, King JL, Bandos AI, Sumkin JH. Impact of the new density reporting laws: Radiologist perceptions and actual behavior. Acad Radiol 2015;22:679–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schapira MM, Sprague BL, Klabunde CN, et al. Inadequate systems to support breast and cervical cancer screening in primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:1148–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen SL, Margolies LR, Schwager SJ, et al. Early discussion of breast density and supplemental breast cancer screening: Is it possible? Breast J 2014;20:229–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freer P, Slanetz P, Haas J, et al. Breast cancer screening in the era of density notification legislation: Summary of 2014 Massachusetts experience and suggestion of an evidence-based management algorithm by multi-disciplinary expert panel. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;153:455–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho JM, Jafferjee N, Covarrubias GM, Ghesani M, Handler B. Dense breasts: A review of reporting legislation and available supplemental screening options. Am J Roentgenol 2014;203:449–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hooley RJ, Greenberg KL, Stackhouse RM, Geisel JL, Butler RS, Philpotts LE. Screening US in patients with mammographically dense breasts: Initial experience with Connecticut Public Act 09-41. Radiology 2012;265:59–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Flynn EAM, Ledger AEW, deSouza NM. Alternative screening for dense breasts: MRI. Am J Roentgenol 2015;204:W141–W149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sprague BL, Stout NK, Schechter C, et al. Benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of supplemental ultrasonography screening for women with dense breasts. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:157–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans DG, Kesavan N, Lim Y, Gadde S, Hurley E, Massat NJ. MRI breast screening in high-risk women: Cancer detection and survival analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014;145:663–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raikhlin A, Curpen B, Warner E, Betel C, Wright B, Jong R. Breast MRI as an adjunct to mammography for breast cancer screening in high-risk patients: Retrospective review. Am J Roentgenol 2015;204:889–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1998–2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA 2016;315:1784–1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Price ER, Hargreaves J, Lipson JA, et al. The California Breast Density Information Group: A collaborative response to the issues of breast density, breast cancer risk, and breast density notification legislation. Radiology 2013;269:887–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sabatino SA, McCarthy EP, Phillips RS, Burns RB. Breast cancer risk assessment and management in primary care: Provider attitudes, practices, and barriers. Cancer Detect Prev 2007;31:375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collins IM, Steel E, Mann GB, et al. Assessing and managing breast cancer risk: Clinicians' current practice and future needs. Breast 2014;23:644–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henderson J, Weisman C. Physician gender effects on preventive screening and counseling: An analysis of male and female patients' health care experiences. Med Care 2001;39:1281–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krähenmann-Müller S, Virgini VS, Blum MR, et al. Patient and physician gender concordance in preventive care in university primary care settings. Prev Med 2014;67:242–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bertakis K, Franks P, Epstein R. Patient-centered communication in primary care: Physician and patient gender and gender concordance. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:539–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martino S, Haeseler F, Belitsky R, Pantalon M, Fortin AH. Teaching brief motivational interviewing to year three medical students. Med Educ 2007;41:160–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]