Abstract

Background

Platelet P2Y12 antagonist ticagrelor reduces mortality after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) compared to clopidogrel, but the underlying mechanism is unknown. Because activated platelets, leukocytes, and endothelial cells release proinflammatory and prothrombotic extracellular vesicles (EVs), we hypothesized that the release of EVs is more efficiently inhibited by ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel.

Objectives

We compared EV concentrations and EV procoagulant activity in plasma of patients after AMI treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel.

Methods

After percutaneous coronary intervention, 60 patients with first AMI were randomized to ticagrelor or clopidogrel. Flow cytometry was used to determine concentrations of EVs from activated platelets (CD61+, CD62p+), fibrinogen+, phosphatidylserine (PS+), leukocytes (CD45+), endothelial cells (CD31+, 146+), and erythrocytes (CD235a+) in plasma at randomization, after 72 hours and 6 months of treatment. A fibrin generation test was used to determine EV procoagulant activity.

Results

Concentrations of platelet, fibrinogen+, PS+, leukocyte, and erythrocyte EVs increased 6 months after AMI compared to the acute phase of AMI (P ≤ .03). Concentrations of platelet EVs were lower on ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel after 6 months (P = .03). Concentrations of fibrinogen+, PS+, and leukocyte EVs were lower on ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel both after 72 hours and 6 months (P ≤ .03). Concentrations of endothelial EVs and EV procoagulant activity did not differ between patient groups and over time (P ≥ .17).

Conclusions

Ticagrelor attenuates the increase of EV concentrations in plasma after acute myocardial infarction compared to clopidogrel. The ongoing release of EVs despite antiplatelet therapy might explain recurrent thrombotic events after AMI and worse clinical outcomes on clopidogrel compared to ticagrelor.

Keywords: adenosine diphosphate receptors, antiplatelet drugs, extracellular vesicles, platelets, ticagrelor

Essentials.

Activated platelets, leukocytes, and endothelial cells release extracellular vesicles (EVs)

A randomized controlled trial was performed to compareEV concentrations on ticagrelor or clopidogrel.

Flow cytometry detectors were calibrated in comparable units to ensure reliable EV analysis.

Ticagrelor attenuates the increase in platelet and leukocyteEV concentrations compared to clopidogrel.

1. BACKGROUND

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the vessel wall leading to acute myocardial infarction (AMI).1 In the course of AMI, activated platelets, leukocytes, and endothelial cells (ECs) release extracellular vesicles (EVs).2 A recent systematic review with meta‐analysis of seven clinical studies demonstrated that plasma concentrations of EVs are two‐fold higher in patients with AMI, compared to healthy controls.3 EVs are membrane‐enclosed cell‐derived particles exposing proteins derived from the parent cell. Although a generic EV marker is lacking,4 proteins binding phosphatidylserine (PS) are commonly used to stain ~50% of all plasma EVs.5 Because PS facilitates the assembly of tenase and prothrombinase complexes in the presence of calcium ions, thereby accelerating thrombin formation, PS‐exposing EVs are considered procoagulant.6 EVs also expose specific cell markers (clusters of differentiation, CD) revealing their cellular origin. For example, EVs from activated platelets expose the identification marker glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa (CD41/CD61), and platelet activation markers, such as P‐selectin (CD62p) and fibrinogen.7 Platelet EVs exposing P‐selectin or fibrinogen likely contribute to inflammation and thrombosis. For example, P‐selectin binds to P‐selectin glycoprotein ligand‐1 on monocytes, leading to production and exposure of tissue factor (TF) on monocytes and secretion of pro‐inflammatory cytokines.8 Fibrinogen binds both to the CD11b/CD18 receptor (Mac‐1) on monocytes, thereby activating monocytes, and to the activated GPIIb/IIIa, thereby enabling platelet aggregation.9 Altogether, EVs exposing PS, P‐selectin, and/or fibrinogen may (a) contribute to thrombus formation, and (b) be involved in maintaining the chronic inflammatory state of the vessel wall after AMI. Therefore, inhibition of EV release might be a unique opportunity for combined antithrombotic and anti‐inflammatory treatment strategy after AMI.10

Because AMI is caused by activation of platelets on a ruptured atherosclerotic plaque, dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and antagonist of the platelet P2Y12 receptor for adenosine diphosphate (ADP) has become the standard of care to prevent recurrent thrombotic events after AMI.11 The P2Y12 receptor antagonist ticagrelor provides faster and more pronounced and consistent inhibition of platelet aggregation than clopidogrel, the previous standard antiplatelet treatment after AMI.12 Whereas both clopidogrel and ticagrelor inhibit the platelet P2Y12 receptor for ADP, only ticagrelor inhibits the reuptake of adenosine, thus increasing the concentration of adenosine in the bloodstream.13 Both inhibition of the P2Y12 receptor and activation of the A2a receptor by adenosine inhibit platelet activation.14 Ticagrelor reduces the rate of recurrent thrombotic events and mortality compared to clopidogrel, as shown in the PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patients Outcomes) study, confirming that the extent of platelet inhibition is associated with prognosis.15 However, improved prognosis on ticagrelor cannot be explained solely by ticagrelor anti‐aggregatory effect, because the anti‐aggregatory effect is achieved directly after ticagrelor administration, whereas reduction in mortality starts after at least 2 weeks and increases with the length of treatment.15 Thus, likely other mechanisms than inhibition of platelet aggregation contribute to the benefits of long‐term treatment with ticagrelor.

We hypothesized that ticagrelor decreases plasma concentrations of prothrombotic and pro‐inflammatory EVs compared to clopidogrel, which potentially contributes to improved prognosis in patients treated with ticagrelor. Because P2Y12 receptors are exposed also on leukocytes,16, 17 and vascular ECs,18, 19 ticagrelor and clopidogrel might affect the release of EVs from leukocytes and ECs as well.

2. OBJECTIVES

The goal of the AFFECT EV (Antiplatelet therapy eFFECT on Extracellular Vesicles) trial was to compare the effect of ticagrelor and clopidogrel on the concentration and procoagulant activity of circulating EVs in patients after AMI.

3. METHODS

3.1. Study design

AFFECT EV was an investigator‐initiated, single‐center, randomized study conducted at the First Chair and Department of Cardiology, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland, in collaboration with the Vesicle Observation Centre, Amsterdam University Medical Centres (UMC), the Netherlands. The study protocol, designed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the Ethics Committee of Medical University of Warsaw (approval number: KB/112/2016), registered in the ClinicalTrials database (NCT02931045) and published previously.20 All participants provided written informed consent.

3.2. Selection of participants

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. Patients were eligible for enrollment if they (a) were admitted to the hospital due to the first ST‐segment elevation of acute myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non‐STEMI (NSTEMI) with an onset of symptoms during the previous 24 hours, and (b) underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stent implantation. When study was initiated, the majority of patients with STEMI were pretreated with clopidogrel before hospital admission. Hence, only patients who received a loading dose of clopidogrel (600 mg) were enrolled to obtain a homogenous group. STEMI was diagnosed based on persistent ST‐segment elevation of at least 0.1 mV in at least two contiguous electrocardiography leads or a new left bundle‐branch block.21 NSTEMI was diagnosed as ST‐segment changes on electrocardiogram (ECG) including ST depression, transient ST elevation, and T‐wave changes, along with a positive cardiac troponin test indicating myocardial necrosis in patients with the typical anginal chest pain.22

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for the study

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

Abbreviations: AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CYP3A4, cytochrome P450 izoenzyme 3A4; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GP, glycoprotein; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention

3.3. Randomization and blinding

The trial schedule is presented in Figure 1A. Within 24 hours PCI, patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio either to replace clopidogrel with ticagrelor (study group) or to continue treatment with clopidogrel (control group). Block randomization with fixed block size of eight without stratification was conducted using a sealed envelope system by an independent operator (MP), who was otherwise not involved in sample collection and analysis. During the trial, participants were identified by an individual randomization number, and samples were coded with a unique sample number. All samples were measured in one block by an operator blinded to treatment‐related data (AG). Flow cytometry data analysis was performed by an independent operator, blinded to any clinical data (EvdP). Statistical analysis was performed by an independent operator (MB).

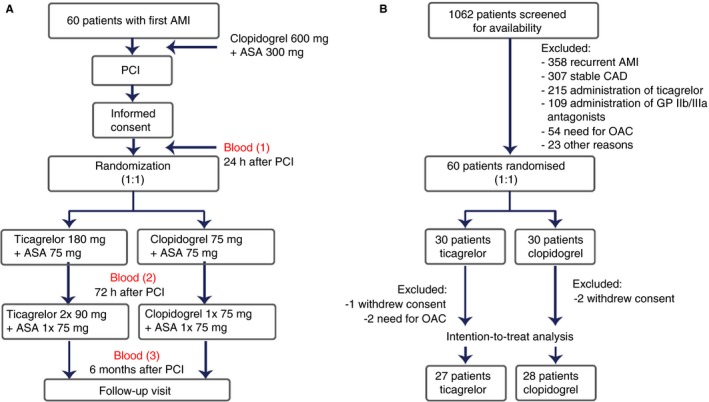

Figure 1.

Study design (A) and inclusion and exclusion chart (B). Abbreviations: AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; CAD, coronary artery disease; GP, glycoprotein; OAC, oral anticoagulation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention

3.4. Study treatment

Ticagrelor was given in a loading dose of 180 mg, followed by a maintenance dose of 90 mg twice daily. Clopidogrel was continued with a maintenance dose of 75 mg daily. At discharge, patients received either ticagrelor or clopidogrel for 6 months of treatment, when a follow‐up visit was scheduled. In addition, all patients received 75 mg aspirin and at least 10 mg atorvastatin once daily. All patients received standard treatment after AMI according to the guidelines, including β‐blocker, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, aldosterone receptor antagonist, and protein pump inhibitor, depending on the individual clinical characteristics and comorbidities.21

3.5. Clinical data collection

As baseline, we defined the moment of randomization. The following data were collected at baseline: demographics (age, gender), body mass index, diagnosis at admission, cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes), history of cardiovascular disease (stroke, carotid artery disease, peripheral artery disease). In addition, routine laboratory parameters were recorded. Before discharge, patients underwent detailed echocardiographic evaluation and left ventricle ejection fraction and global longitudinal strain was recorded. At discharge, pharmacotherapy was recorded. At the follow‐up visit, compliance was checked by counting of tablets, pharmacotherapy was recorded again, and data regarding major adverse cardiovascular events (recurrent AMI, need for urgent revascularization, recurrent hospital admission) and bleeding events since the index hospitalisation were recorded.

3.6. Samples collection and handling

Venous blood was collected from fasting patients (a) 24 hours after administration of clopidogrel (randomization ~ baseline), (b) 48 hours following randomization to ticagrelor or clopidogrel group (matching the length of the hospital stay of patients after AMI ~ 72 hours), and (c) 6 months following the index hospitalization (follow‐up visit). With fasting, we mean ≥8 hours after last consumption. Blood was collected and processed by an experienced operator (KP), according to the recent guidelines to study EVs.23 Briefly, blood was collected in 10 mL 0.109 mol/L citrated plastic tubes (S‐Monovette, Sarstedt) via antecubital vein puncture using a 19‐gauge needle, without tourniquet. The first 2 mL were discarded to avoid pre‐activation of platelets. Within maximum 15 minutes from blood collection, platelet‐depleted plasma was prepared by double centrifugation using a Rotina 380 R equipped with a swing‐out rotor and a radius of 155 mm (Hettich Zentrifugen). The centrifugation parameters were: 2500 g, 15 minutes, 20°C, acceleration speed 1, no brake.24 The first centrifugation step was done with 10 mL whole blood collection tubes. Supernatant was collected 10 mm above the buffy coat. The second centrifugation step was done with 3.5 mL plasma in 15 mL polypropylene centrifuge tubes (Greiner Bio‐One B.V). Supernatant (platelet‐depleted plasma) was collected 5 mm above the buffy coat, transferred into 5 mL polypropylene centrifuge tubes (Greiner Bio‐One B.V.), mixed by pipetting, transferred to 1.5 mL low‐protein binding Eppendorfs (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and stored in −80°C until analyzed. Prior to analysis, samples were thawed for 1 minute in a water bath (37°C) to avoid cryoprecipitation. At each time point, an additional blood sample was collected to 2.7 mL hirudin tube to assess platelet reactivity using multiple electrode aggregometry (Roche Diagnostics) to check the compliance and response to ASA and P2Y12 antagonists.

3.7. Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the concentration of EVs from activated platelets (exposing CD61 and P‐selectin) at 6 months. The secondary endpoints were (a) the concentration of platelet EVs exposing CD61 and P‐selectin at 72 hours, and (b) the concentration of platelet EVs exposing fibrinogen, leukocyte EVs, and EC‐derived EVs at 72 hours and 6 months. The tertiary endpoint was procoagulant activity of plasma EVs at 72 hours and 6 months, defined as (a) the concentration of plasma EVs exposing PS, and (b) the TF‐dependant procoagulant activity of all plasma EVs. The study was not powered for mortality or other adverse events.

3.8. Laboratory assays

3.8.1. Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry (A60‐Micro, Apogee Flow Systems) was used to determine the concentration of EV subtypes in platelet‐depleted plasma. The reported concentrations describe the number of particles (a) that exceeded the side scatter threshold, corresponding to a side scattering cross section of 10 nm2, (b) with a diameter >200 nm as determined by Flow‐SR,25 (c) having a refractive index <1.42 to omit false positively labeled chylomicrons,26 and (d) that are positive at the fluorescence detector(s) corresponding to the used label(s), per mL of platelet‐depleted plasma. We aimed to label activated platelets (CD61+/P‐selectin+), fibrinogen+, leukocytes (CD45+), ECs (CD31+/CD146+), erythrocytes (CD235a+), and all procoagulant EVs (PS+) in platelet‐depleted plasma. To improve the reproducibility of our EV flow cytometry experiments, we (a) applied the new reporting framework for the standardized reporting of EV flow cytometry experiments (MIFlowCyt‐EV),27 (b) calibrated all detectors, (c) determined the EV diameter and refractive index by the flow cytometry scatter ratio (Flow‐SR),25 and (d) applied custom‐built software to fully automate data calibration and processing. All relevant details about sample preparation, assay controls, instrument calibration, data acquisition, and EV characterization are included in the Supporting Information.

3.8.2. Procoagulant activity of plasma EVs

The procoagulant activity of plasma EVs was determined as the ability of EVs to generate fibrin in platelet‐depleted but EV‐containing plasma.28 Briefly, after pre‐incubation for 5 minutes at 37°C, clotting was initiated by adding CaCl2 (final concentration 2.5 mmol/L). Fibrin formation (~clotting) over 1 hour was determined by measuring the optical density (OD; λ = 405 nm) in duplicate on a spectrophotometer (SpectraMax) at 37°C. When plasma clots, the OD increases. Because TF is the key initiator of the coagulation, and because plasma EVs in patients with AMI expose TF,29 the procoagulant activity of plasma EVs was evaluated in the absence and presence of antibodies against human TF (anti‐TF; CLB; clone CLB‐VII‐1). Recombinant human TF was used as a positive control, and saline was used as a negative control. Only reproducible results were taken into account for analysis. At the beginning, the OD was set to 0. Clotting was defined as an increase in OD from 0 to >0.2. Reproducible results were defined as results which showed clotting or lack thereof in duplicate. To obtain the clotting time (V max), OD versus time data were fitted with the Hill function by least square fitting (MATLAB R2018b, Mathworks). The following parameters were calculated: (a) clotting inhibition or delay by anti‐TF, defined as percentage of patients in whom clotting was either entirely inhibited or at least 10% delayed in presence of anti‐TF; (b) clotting time delay by anti‐TF, defined as clotting time of plasma in absence of anti‐TF minus clotting time of plasma in presence of anti‐TF; and (c) OD decrease by anti‐TF, defined as OD of plasma in absence of anti‐TF minus OD of plasma in presence of anti‐TF, as an indirect measure of changes in clot thickness.

3.8.3. Compliance and response to dual antiplatelet therapy

Platelet reactivity in response to dual antiplatelet therapy was assessed by multiple electrode aggregometry using the commercially available ASPI test (arachidonic acid, 0.5 mmol/L) and the ADP test (ADP, 6.5 µmol/L), respectively.30 The TRAP (thrombin receptor‐activating peptide‐6 [SFLLRN], 32 µmol/L) test was used as a positive control. Although ADP released from platelets activated by TRAP amplifies the response to TRAP, the TRAP test was the best available control. Unstimulated whole blood was used as a negative control.

3.9. Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated based on preliminary in vitro experiments.20 We observed that in the presence of ticagrelor, activated platelets release two‐fold fewer EVs than in the absence of ticagrelor. Based on this observation, the required sample size was calculated by a two‐sided t‐test at a significance level of .05 with the following assumptions: (a) standard deviation (SD) in each group ± 1.0, (b) mean difference between the groups = 1, and (c) nominal test power = 0.9. Based on this sample size estimation, a total of 46 patients (23 per group) should be enrolled in the study to observe a mean difference in the platelet EV concentrations. Taking into account that up to 30% of patients can be potentially lost to follow‐up, 60 patients (30 per group) were included in the study.

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 24.0 (IBM). Categorical variables were presented as number and percent and compared using Fischer's exact test. A Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess normal distribution of continuous variables. Continuous variables were presented as mean and SD or median with interquartile range. Linear regression taking into account EV concentration at baseline and at 72 hours as additional covariates were used to compare the concentrations between the two treatment arms at 6 months. All other variables were compared using an unpaired t‐test or Mann‐Whitney U test, depending on the data distribution. Differences in variables between three time points were assessed using a Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn's correction for multiple comparisons. Correlations between EV concentrations and platelet reactivity or parameters of a fibrin generation test (FGT) were analyzed using a Spearman correlation coefficient test. Mortality and other adverse events were reported descriptively. A P‐value below .05 was considered significant.

4. RESULTS

An exclusion and inclusion chart of the study is shown in Figure 1B. Of the 1062 patients who underwent PCI with stent implantation between January 2017 and June 2018, 60 patients were randomized and 55 patients were included in the final analysis (27 in the ticagrelor group and 28 in the clopidogrel group). Patient characteristics are presented in Table 2. There were no differences in baseline, clinical, and laboratory characteristics between the groups. At hospital discharge after AMI, the mean left ventricle ejection fraction and global longitudinal strains, as well as pharmacotherapy, were well balanced between the groups. All patients received aspirin; all patients except for one received atorvastatin; and more than 90% of patients received a β‐blocker, an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, and a proton pump inhibitor. All additional orally administered drugs are listed in Table S3 in supporting information and were comparable between the groups.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics (intention‐to‐treat population)

| Characteristic | Ticagrelor (n = 27) | Clopidogrel (n = 28) | P‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | SD, range, % | N | SD, range, % | .23 | |

| Age, years – mean ± SD | 66 | 10 | 63 | 10 | .77 |

| Male gender – number (%) | 19 | 70 | 21 | 75 | .38 |

| BMI – median (IQR) | 28 | 5 | 29 | 4 | .38 |

| Diagnosis at admission – number (%) | |||||

| STEMI | 18 | 67 | 22 | 79 | .38 |

| NSTEMI | 9 | 33 | 6 | 21 | .76 |

| Administration of morphine at admission | 6 | 22 | 8 | 28 | .76 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors – number (%) | |||||

| Arterial hypertension | 18 | 67 | 18 | 57 | .78 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 | 19 | 5 | 18 | 1.00 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 18 | 67 | 23 | 82 | .23 |

| Smoking | 26 | 96 | 23 | 82 | .19 |

| History of CVD – number (%) | |||||

| Stroke | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1.00 |

| Carotid artery disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 0 | 0 | 3 | 11 | .24 |

| Laboratory characteristics at admission | |||||

| CK‐MB, ng/mL – median (IQR) | 16 | 4‐97 | 37 | 12‐93 | .57 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL – median (IQR) | 0.9 | 0.7‐1.1 | 1 | 0.8‐1.1 | .56 |

| C‐reactive protein – median (IQR) | 3 | 2‐6 | 4 | 2‐6 | .75 |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL – mean ± SD | 14 | 1 | 14 | 2 | .11 |

| INR – median (IQR) | 1.1 | 1.0‐1.2 | 1.1 | 1.0‐1.2 | .75 |

| LDL‐C – mean ± SD | 120 | 40 | 127 | 39 | .48 |

| NT‐proBNP – median (IQR) | 1277 | 361‐2498 | 628 | 211‐1765 | .33 |

| Platelet count, 103/μL – mean (SD) | 237 | 78 | 245 | 65 | .64 |

| Troponin I, ng/mL – median (IQR) | 11 | 1‐35 | 23 | 4‐37 | .24 |

| Echocardiography at discharge | |||||

| LVEF, % – median (IQR) | 45 | 27‐53 | 45 | 35‐50 | .28 |

| GLS, % – mean ± SD | 17.3 | 4.5 | 16.2 | 4.7 | .61 |

| Pharmacotherapy at discharge – number (%) | |||||

| Aspirin | 27 | 100 | 28 | 100 | 1.00 |

| Atorvastatin | 27 | 100 | 27 | 96 | 1.00 |

| β‐blocker | 25 | 93 | 25 | 89 | 1.00 |

| ACE‐inhibitor or ARB | 25 | 93 | 28 | 100 | .24 |

| Aldosterone receptor antagonist | 7 | 26 | 7 | 25 | 1.00 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 26 | 96 | 26 | 93 | 1.00 |

| Pharmacotherapy at 6 mo – number (%) | |||||

| Aspirin | 27 | 100 | 28 | 100 | 1.00 |

| Atorvastatin | 27 | 100 | 28 | 100 | 1.00 |

| β‐blocker | 25 | 93 | 26 | 93 | 1.00 |

| ACE‐inhibitor or ARB | 25 | 93 | 27 | 96 | 1.00 |

| Aldosterone receptor antagonist | 6 | 22 | 5 | 18 | .75 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 89 | 89 | 25 | 89 | 1.00 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin‐receptor blockers; BMI, body mass index, weight in kilograms divided by square of the height in meters; CK‐MB, creatine kinase muscle‐brain isoenzyme; CVD, cardiovascular disease; GLS, global longitudinal strain; INR, international normalized ratio; IQR, interquartile range; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein‐cholesterol; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; NSTEMI, non‐ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐b‐type natriuretic peptide; SD, standard deviation; STEMI, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction.

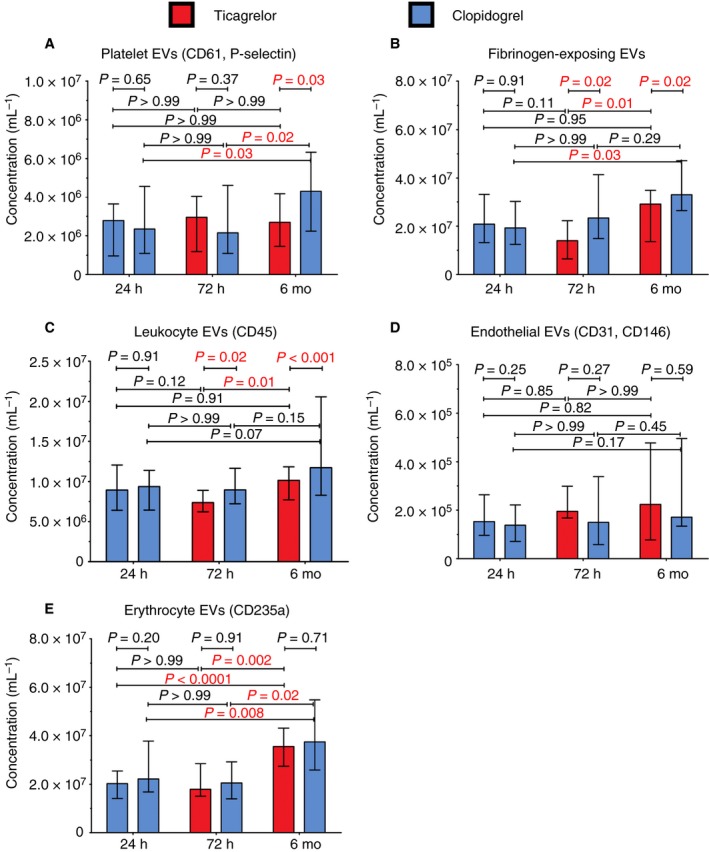

4.1. Concentrations of extracellular vesicles

Figure 2 shows the concentrations of EVs in platelet‐depleted plasma, measured with flow cytometry at 24 hours and after 72 hours and 6 months of treatment with ticagrelor or clopidogrel. At 24 hours, concentrations of all EV subtypes were comparable between patient groups.

Figure 2.

Concentrations of extracellular vesicles (EVs) measured with flow cytometry in platelet‐depleted plasma prepared from patients treated with ticagrelor and clopidogrel after 24 hours, 72 hours, and 6 months after onset of AMI. We included EVs exceeding the side scatter threshold (≥10 nm2), having a diameter >200 nm, having a refractive index <1.42, and being positive for the labelled fluorophore. A,B, EVs from activated platelets exposing activation/aggregation markers (CD61 and P‐selectin, fibrinogen). C, EVs from leukocytes. D, EVs from endothelial cells. E, EVs from erythrocytes

Figure 2A shows the concentrations of EVs from activated platelets (CD61+/P‐selectin+). After 72 hours, EVs from activated platelets were comparable between the patient groups. After 6 months, EVs from activated platelets were lower on ticagrelor, compared to clopidogrel. Over time, the concentrations of EVs from activated platelets remained stable on ticagrelor and increased two‐fold on clopidogrel.

Figure 2B shows the concentrations of EVs from activated platelets/aggregates (fibrinogen+). After 72 hours and after 6 months, the concentrations of fibrinogen+ EVs were lower on ticagrelor, compared to clopidogrel. Over time, the concentrations of fibrinogen+ EVs increased ~two‐fold both on ticagrelor and on clopidogrel.

Figure 2C shows the concentrations of EVs from leukocytes (CD45+). After 72 hours and after 6 months, the concentrations of leukocyte EVs were lower on ticagrelor, compared to clopidogrel. Over time, the concentrations of leukocyte EVs increased on ticagrelor and remained stable on clopidogrel.

Figure 2D shows the concentrations of EVs from ECs (CD31+/CD146+). After 72 hours and after 6 months, the concentrations of EC EVs were comparable between the patient groups. Over time, the concentrations of EC EVs did not change.

Figure 2E shows the concentrations of EVs from erythrocytes (CD235+; “control EVs”). After 72 hours and after 6 months, the concentrations of EVs from erythrocytes were comparable between the patient groups. Over time, the concentrations of erythrocyte EVs increased two‐fold in both patient groups.

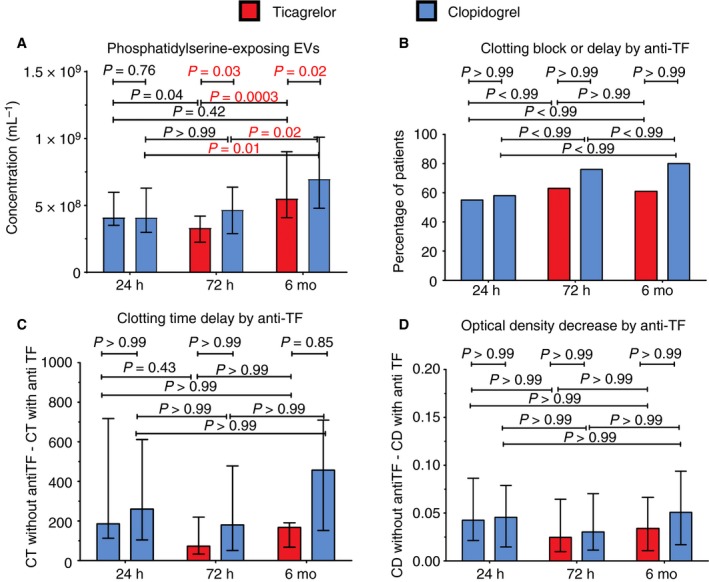

4.2. Procoagulant activity of plasma EVS

Figure 3 shows plasma EV procoagulant activity in patients treated with ticagrelor and clopidogrel determined as (a) the concentration of all EVs exposing PS measured with flow cytometry (Figure 3A), and (b) the TF‐dependent procoagulant activity of all EVs measured with FGT (Figure 3B‐D) at 24 hours, after 72 hours, and 6 months.

Figure 3.

Procoagulant activity of plasma extracellular vesicles (EVs) in platelet‐depleted plasma prepared from patients treated with ticagrelor and clopidogrel determined as the concentration of phosphatidylserine‐exposing EVs (A) and as the ability of EVs to generate fibrin in platelet‐free, but EV‐containing plasma following recalcification (fibrin generation test) in absence and presence of antibody against human tissue factor (activated factor VII; B‐D). A, includes EVs exceeding the side scatter threshold (≥10 nm2), having a diameter >200 nm, having a refractive index <1.42, and being positive for the labelled fluorophore. CT, clotting time; OD, optical density

Figure 3A shows the concentrations of EVs exposing PS (lactadherin+). At 24 hours, the concentrations of PS‐exposing EVs were comparable between the patient groups. After 72 hours and after 6 months, the concentrations of PS‐exposing EVs were lower on ticagrelor, compared to clopidogrel. Over time, concentrations of PS‐exposing EVs increased both on ticagrelor and on clopidogrel.

Figure 3B‐D shows the results of FGT: the inhibition (complete block) or delay (at least 10% prolongation) of clotting (Figure 3B), the amount of clotting time delay in the presence of anti‐TF (Figure 3C), and the decrease in OD reflecting a change in clot thickness (Figure 3D) in the presence of anti‐TF. The reproducible results were obtained in 21 patients on ticagrelor (77%), and 17 patients on clopidogrel (61%). The coefficients of variations of the measured parameters were between 0.01% and 47%. All FGT parameters were comparable between the treatment groups both at 24 hours, after 72 hours, and after 6 months. None of the parameters changed over time. The examples of the FGT clotting curves are included in the Supporting Information.

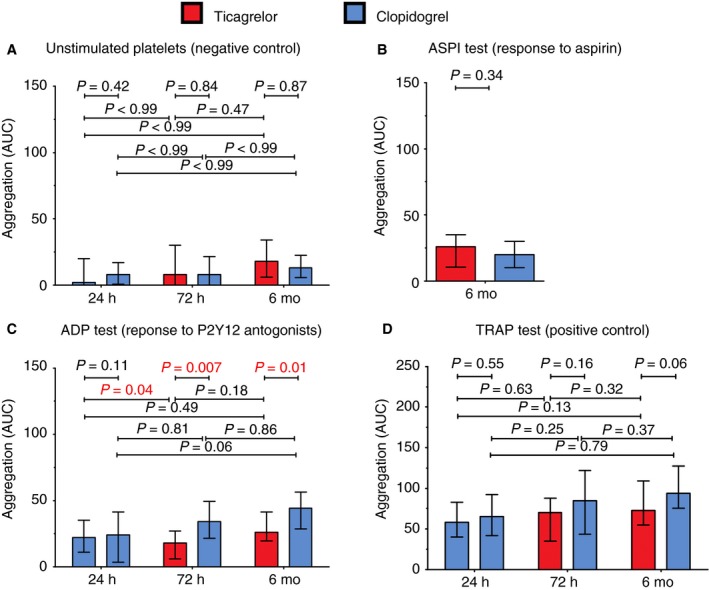

4.3. Platelet reactivity

Figure 4 shows platelet reactivity of unstimulated platelets (negative control), in response to arachidonic acid (response to aspirin), ADP (response to P2Y12 antagonists), and TRAP (positive control) at 24 hours, and after 72 hours and 6 months of treatment with ticagrelor or clopidogrel. Platelet reactivity of unstimulated platelets, platelets activated with AA, and TRAP was comparable at each time point and stable over time (Figure 4A,B,D). Platelet reactivity in response to ADP was comparable between patient groups at 24 hours, when all patients were treated with clopidogrel. After 72 hours and after 6 months, platelet reactivity in response to ADP was lower in patients treated with ticagrelor. Over time, platelet reactivity in response to ADP decreased on ticagrelor (Figure 4C). High‐on treatment platelet reactivity (HTPR), defined as platelet reactivity >46 aggregation units in response to 6.5 μmol/L ADP,31 was observed in one patient on ticagrelor (4%) and nine patients on clopidogrel (32%) at 6 months (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Platelet aggregation in blood collected from patients treated with ticagrelor and clopidogrel; control (unstimulated platelets) and in response to arachidonic acid (ASPI test), adenosine diphosphate (ADP test), and thrombin receptor‐activating peptide‐6 (TRAP test)

4.4. Correlations

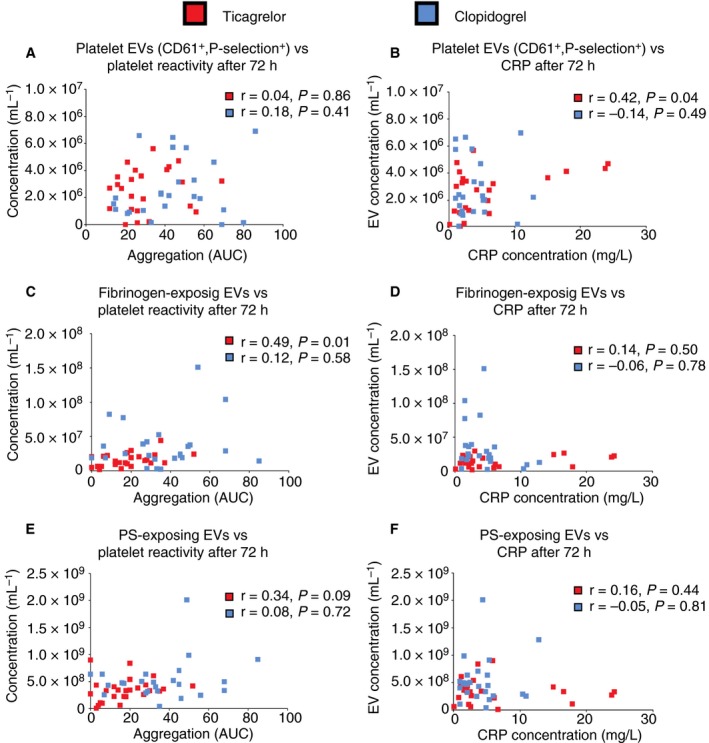

Figure 5 shows the correlations between (a) concentrations of EVs and platelet reactivity in response to ADP (Figure 5A,C,E) and (b) concentrations of EVs and concentration of C‐reactive protein (CRP; Figure 5B,D,F) after 72 hours of treatment with clopidogrel or ticagrelor. In the ticagrelor group, the concentration of EVs from activated platelets (CD61+, P‐selectin+) correlated with the concentration of CRP (Figure 5B), whereas the concentration of EVs exposing fibrinogen correlated with platelet reactivity (Figure 5C). In the clopidogrel group, we did not find any correlations between concentrations of EVs and CRP or platelet reactivity in response to ADP after 72 hours (Figure 5A‐F). We did not find any correlations between concentrations of any EV subtype and platelet reactivity in response to ADP after 6 months (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Correlations between (a) concentrations of extracellular vesicles (EVs) and platelet reactivity in response to ADP (A, C, E) and (b) concentrations of EVs and concentration of C‐reactive protein (CRP; B, D, F) after 72 hours of treatment with clopidogrel or ticagrelor

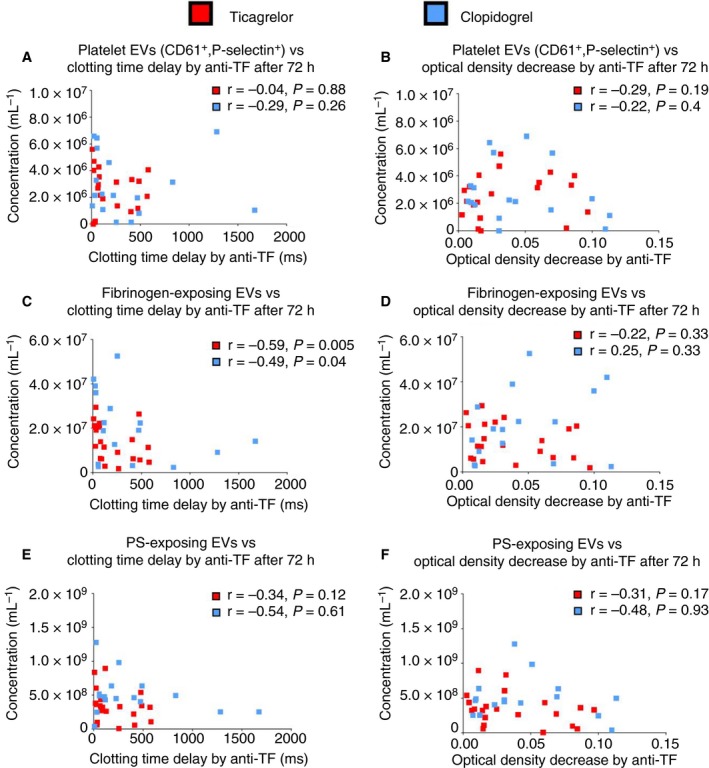

Figure 6 shows the correlations between (a) concentrations of EVs and clotting time delay by anti‐TF (Figure 6A,C,E) and (b) concentrations of EVs and decrease in OD by anti‐TF (Figure 6B,D,F) after 72 hours of treatment with clopidogrel or ticagrelor. There was a negative correlation between fibrinogen‐exposing EVs and clotting time delay by anti‐TF both on ticagrelor and on clopidogrel (Figure 6C), indicating that higher concentration of fibrinogen‐exposing EVs is associated with greater procoagulant activity of plasma TF‐exposing EVs (less inhibition by anti‐TF).

Figure 6.

Correlations between (a) concentrations of EVs and clotting time delay by anti‐TF (A, C, E) and (b) concentrations of EVs and decrease in OD by anti‐TF (B, D, F) after 72 hours of treatment with clopidogrel or ticagrelor

4.5. Clinical outcomes

There were no deaths and no recurrent thrombotic events during the study. There were two recurrent hospitalizations: (a) due to exacerbation of heart failure in the ticagrelor group, and (b) due to pneumonia in the clopidogrel group. There was one major bleeding event from the gynecologic tract in the ticagrelor group and one major bleeding event from a diabetic foot ulcer in the clopidogrel group. Both bleeding events were reported to the local authorities and assessed by the Steering Committee as unrelated to the study treatment.

4.6. Compliance

Based on counting of tablets, one patient on ticagrelor (4%) and one patient on clopidogrel (4%) temporarily interrupted antiplatelet therapy due to major bleeding event, as described above. Antiplatelet therapy was re‐initiated after less than a week, once the cause of bleeding had been managed.

5. DISCUSSION

AFFECT EV is the first clinical study which directly compared the long‐term effects of P2Y12 antagonists ticagrelor and clopidogrel on the concentrations and procoagulant activity of plasma EVs in a randomized and investigator‐blinded way. Different P2Y12 antagonists added to whole blood or platelet‐rich plasma were shown to decrease the agonist‐induced release of platelet EVs.28, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 However, the previous evidence was derived from experimental studies28, 34 and one uncontrolled cohort study,37 whereas our study compared the effects of ticagrelor and clopidogrel on EV release head‐to‐head, in a randomized and investigator‐blinded way. Thus, our study increased the level of evidence of this finding from level C (data derived from small, observational studies) to level B (data derived from a single randomized controlled trial).11, 21, 22 Further, AFFECT EV is the first clinical study in which the recently standardized protocols and guidelines23, 27, 38, 39 were applied to prevent artefacts and maximize the reliability and reproducibility of the results. For example, we determined the EV diameter and refractive index by Flow‐SR,25 we calibrated all flow cytometry detectors in comparable measurement units and automated data processing to ensure reliability, comparability, and reproducibility.38 Thus, we present the first comparable EV data in a clinical study.

The main finding of our study is that ticagrelor attenuates the increase of platelet (CD61+, P‐selectin+), fibrinogen+, PS+, and leukocyte EV concentrations in plasma after acute myocardial infarction compared to clopidogrel. The increase in EV exposing P‐selectin, fibrinogen and PS and EVs from leukocytes over time might at least partly explain the 10% of recurrent thrombotic events on ticagrelor observed in the PLATO study, as well as the higher rate of recurrent thrombotic events on clopidogrel, compared to ticagrelor. It was previously reported that the aggregation of platelets is a prerequisite for EV release.40 Because ticagrelor blocks platelet aggregation to a greater extent than clopidogrel, the larger “anti‐EV” effect of ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel may be merely due to incomplete platelet inhibition by clopidogrel. Indeed, in a recent observational study in 38 patients after AMI, patients treated with ticagrelor or prasugrel had lower concentrations of P‐selectin+ platelet EVs, compared to those treated with clopidogrel.37 Hence, prasugrel might have the same effect on EVs as ticagrelor. On the other hand, ticagrelor blocks platelet aggregation via a double pathway (blocking the P2Y12 receptor and increasing the concentration of adenosine), whereas clopidogrel and prasugrel block the P2Y12 receptor only.14, 41 Because adenosine has both antiplatelet and anti‐inflammatory effects,12, 17, 41 adenosine may also contribute to the “anti‐EV” effect of ticagrelor. Because we did not measure adenosine serum level, we can only speculate about the mechanism underlying the inhibition of EV release by ticagrelor.

In patients treated with ticagrelor, the concentrations of EVs exposing CD61 and P‐selectin correlated with the concentration of CRP (r = .42, P = .04), whereas the concentrations of EVs exposing fibrinogen correlated with platelet reactivity (r = .49, P = .01), suggesting that EVs exposing P‐selectin are indicators of inflammation, whereas EVs exposing fibrinogen reflect ongoing thrombosis. In the case of ticagrelor, the correlation between fibrinogen‐exposing EVs and platelet reactivity30, 37 suggests that EVs could potentially be applied as a tool to monitor antiplatelet therapy. The lack of correlation between P‐selectin exposing EVs and CRP in the clopidogrel group may result from different effects of ticagrelor and clopidogrel on immune signalling.42 In the PLATO study, the concentration of CRP was higher on ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel at hospital discharge.42 Despite higher CRP concentrations at discharge, patients treated with ticagrelor had a lower rate of infection‐related death during a 12‐month observation period, suggesting that the increase in CRP in the acute phase of AMI paradoxically translates to better long‐term outcomes. In turn, the lack of correlation between fibrinogen exposing EVs and platelet reactivity on clopidogrel may be caused by the fact that, in case of ticagrelor, the antiplatelet and “anti‐EV” effect are associated with each other, whereas in the case of clopidogrel the antiplatelet effect is present in most patients and the “anti‐EV” effect is absent.

Lower concentrations of EVs exposing P‐selectin, fibrinogen, and PS as well as leukocyte EVs in the acute phase of AMI, compared to the later phase, might be due to the fact that the baseline values are suppressed by administration of the loading dose of antiplatelet drugs and/or anticoagulants in the first 24 hours after AMI. Indeed, in a recent meta‐analysis the post‐PCI concentrations of platelet EVs were shown to be 100% lower, compared to the pre‐PCI concentrations.3 Alternatively, EVs may become part of a thrombus during AMI. In vitro, perfusion of whole blood over type I collagen decreased the concentration of platelet EVs exposing the activated glycoprotein IIb‐IIIa in post‐perfusion blood.43 Further, scanning electron microscopy revealed that thrombi expose 0.1‐0.5 μm in diameter, granular and CD61‐positive particles, suggesting that platelet EVs adhere to fibrin.44, 45 Incorporation of EVs in thrombi in the acute phase of AMI may result in a lower concentration of platelet EVs in systemic blood. To support this, concentrations of P‐selectin+ platelet EVs increased over a 2‐year follow‐up period in 105 patients after AMI.46

Because no placebo group was included in the study due to ethical reasons, it cannot be excluded that not only ticagrelor, but also clopidogrel, decreases the release of EVs. If present, the “anti‐EV effect” of clopidogrel is less compared to ticagrelor. In fact, the inhibition of EV release does not seem to be specific for P2Y12 antagonists. GPIIb/IIIa antagonists (abciximab, tirofiban) also inhibit EV release, whereas aspirin does not.40, 47 Because (a) ADP‐induced platelet aggregation is not impaired by aspirin,48 (b) ADP amplifies platelet aggregation in response to any platelet agonist,49 and (c) binding of fibrinogen to activated GPIIb/IIIa is crucial for platelet aggregation,41 it seems that only blocking ADP‐dependent aggregation and downstream pathways blocks EV release.

We observed no differences in the concentrations of EC‐EVs over time and no differences after 72 hours and 6 months between the patient groups. In contrast to platelets and leukocytes,17, 50 ECs have mostly A1 receptors for adenosine, and fewer A2a receptors.19 The differences in adenosine receptor profiles between platelets/leukocytes and ECs might explain the lack of effect of the P2Y12 antagonists on EC‐EVs.

In contrast to our expectations, we observed an increase in erythrocyte EVs over time both on ticagrelor and clopidogrel, with no differences between the patient groups. Likely, erythrocyte EVs are affected either by drugs other than P2Y12 antagonists routinely administered in the acute phase of AMI (eg, heparin) or after AMI (eg, statins; Table 2, Table S3). Other studies focusing specifically on erythrocyte EVs are required to explain their increase after AMI and potential effect of drugs.

Regarding the procoagulant function of EVs, we did not find changes in clotting time and clot thickness in patients treated with ticagrelor, compared to clopidogrel. However, because ~30% of the samples were excluded from the analysis due to lack of reproducibility, the functional assay results are underpowered and require further exploration. Other authors demonstrated that ticagrelor suppresses prothrombotic changes in the fibrin clot ultrastructure, compared to clopidogrel, in a group of 20 healthy volunteers administered endotoxin.51

6. LIMITATIONS

The main limitation of our study is the small size and short follow‐up time. Therefore, despite differences in the primary and secondary end points between the groups, the results should be interpreted with caution. The second limitation is the lack of clinical end points, making the results hypothesis generating rather than ultimately proving that lower concentrations of (platelet) EVs are associated with improved prognosis on ticagrelor, or worse prognosis on clopidogrel. Furthermore, although the study was investigator‐blinded, it was open‐label to study participants, so that observer (participant) bias cannot be excluded. Finally, we assessed the response to aspirin only at 6 months, which is less reliable than assessment at each time point.

7. CONCLUSIONS

We found that ticagrelor attenuates the increase of platelet (CD61+, P‐selectin+), fibrinogen+, PS+, and leukocyte EV concentrations in plasma after acute myocardial infarction compared to clopidogrel. Whereas EVs exposing P‐selectin correlate with CRP, EVs exposing fibrinogen correlate with platelet reactivity. Because platelet EVs exposing P‐selectin, fibrinogen, and PS are thought to disseminate thrombosis and inflammation, the ongoing release of platelet EVs despite treatment with clopidogrel or ticagrelor after AMI may explain recurrent thrombotic events despite antiplatelet therapy, as well as worse clinical outcomes on clopidogrel, compared to ticagrelor. Further studies are needed to establish whether there is an association between concentrations of EVs and recurrent thrombotic events during treatment with P2Y12 antagonists.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

E. van der Pol is a cofounder and shareholder of Exometry BV. All other authors report no declarations of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to concept and design, analysis, and/or interpretation of data; critical writing or revising the intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A. Gasecka and K.J. Filipiak acknowledge AstraZeneca/MedImmune for Externally Sponsored Scientific Research Grant in the form of ticagrelor for the study. E. van der Pol acknowledges funding from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research ‐ Domain Applied and Engineering Sciences (NWO‐TTW), research program VENI 15924.

Gasecka A, Nieuwland R, Budnik M, et al. Ticagrelor attenuates the increase of extracellular vesicle concentrations in plasma after acute myocardial infarction compared to clopidogrel. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:609–623. 10.1111/jth.14689

Manuscript handled by: Yukio Ozaki

Final decision: Yukio Ozaki, 25 November 2019

Funding information

The study was funded by the Young Researcher's Grant of the Medical University of Warsaw (1WR\PM2\18 to AG). E. van der Pol was funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research – Domain Applied and Engineering Sciences (NWO‐TTW), research program VENI 15924.

REFERENCES

- 1. Asaria P, Elliott P, Douglass M, et al. Articles acute myocardial infarction hospital admissions and deaths in England: a national follow‐back and follow‐forward record‐linkage study. Lancet Public Heal. 2017;2:e191‐e201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gasecka A, Böing AN, Filipiak KJ, Nieuwland R. Platelet extracellular vesicles as biomarkers for arterial thrombosis. Platelets. 2017;28:228‐234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sun C, Zhao W‐B, Chen Y, Hu H‐Y. Higher plasma concentrations of platelet microparticles in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:1325.e1–1325.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Rond L, van der Pol E, Hau CM, et al. Comparison of generic fluorescent markers for detection of extracellular vesicles by flow cytometry. Clin Chem 2018;64(4):680‐689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arraud N, Linares R, Tan S, et al. Extracellular vesicles from blood plasma: determination of their morphology, size, phenotype and concentration. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:614‐627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Suades R, Padró T, Vilahur G, Badimon L. Circulating and platelet‐derived microparticles in human blood enhance thrombosis on atherosclerotic plaques. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108:1208‐1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rank A, Nieuwland R, Delker R, et al. Cellular origin of platelet‐derived microparticles in vivo. Thromb Res. 2010;126:e255‐e259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Freedman JE, Loscalzo J. Platelet‐monocyte aggregates: bridging thrombosis and inflammation. Circulation. 2002;105:2130‐2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Luyendyk JP, Schoenecker JG, Flick MJ. The multifaceted role of fibrinogen in tissue injury and inflammation. Blood. 2019;133:511‐520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen Arazi H, Badimon JJ. Anti‐inflammatory effects of anti‐platelet treatment in atherosclerosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:4311‐4325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, et al. ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: the Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:213–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kubisa M, Jezewski MP, Gasecka A, Siller‐Matula JM, Postuła M. Ticagrelor–toward more efficient platelet inhibition and beyond. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Armstrong D, Summers C, Ewart L, Nylander S, Sidaway JE, van Giezen JJJ. Characterization of the adenosine pharmacology of ticagrelor reveals therapeutically relevant inhibition of equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19:209‐219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cattaneo M, Schulz R, Nylander S. Adenosine‐mediated effects of ticagrelor: evidence and potential clinical relevance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2503‐2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med Mass Medical Soc. 2009;361:1045‐1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diehl P, Olivier C, Haischeid C, Helbing T, Bode C, Moser M. Clopidogrel affects leukocyte dependent platelet aggregation by P2Y 12 expressing leukocytes. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105:379‐387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Linden J. Regulation of leukocyte function by adenosine receptors. Adv Pharmacol. 2011;61:95‐114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simak J, Gelderman MP. Cell membrane microparticles in blood and blood products: potentially pathogenic agents and diagnostic markers. Transfus Med Rev. 2006;20:1‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kobayashi R, Saitoh O, Nakata H. Identification of adenosine receptor subtypes expressed in the human endothelial‐like ECV304 cells. Pharmacology. 2005;74:143‐151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gasecka A, Nieuwland R, Budnik M, et al. Randomized controlled trial protocol to investigate the antiplatelet therapy effect on extracellular vesicles (AFFECT EV) in acute myocardial infarction. Platelets. 2018;1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2017;2018(39):119‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST‐segment elevation: Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267‐315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Coumans FAW, Brisson AR, Buzas EI, et al. Methodological guidelines to study extracellular vesicles. Circ Res. 2017;120:1632‐1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lacroix R, Robert S, Poncelet P, Kasthuri RS, Key NS, Dignat‐George F. Standardization of platelet‐derived microparticle enumeration by flow cytometry with calibrated beads: results of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis SSC Collaborative workshop. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2571‐2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van der Pol E, de Rond L, Coumans FAW, et al. Absolute sizing and label‐free identification of extracellular vesicles by flow cytometry. Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol Med, 2018;14:801–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. de Rond L, Libregts SFWM, Rikkert LG, et al. Refractive index to evaluate staining specificity of extracellular vesicles by flow cytometry. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019;8:1643671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Welsh JA, van der Pol E, Arkesteijn GJA, et al. MIFlowCyt‐EV: a framework for standardized reporting of extracellular vesicle flow cytometry experiments. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gasecka A, Nieuwland R, van der Pol E, et al. P2Y12 antagonist ticagrelor inhibits the release of procoagulant extracellular vesicles from activated platelets. Cardiol J. 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chiva‐Blanch G, Laake K, Myhre P, et al. Platelet‐, monocyte‐derived and tissue factor‐carrying circulating microparticles are related to acute myocardial infarction severity. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0172558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Storey RF, James SK, Siegbahn A, et al. Lower mortality following pulmonary adverse events and sepsis with ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel in the PLATO study. Platelets. 2014;25:517‐525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Siller‐Matula JM, Trenk D, Schrör K, et al. How to improve the concept of individualised antiplatelet therapy with P2Y12receptor inhibitors – Is an algorithm the answer? Thromb Haemost. 2015;113:37‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Connor DE, Ly K, Aslam A, et al. Effects of antiplatelet therapy on platelet extracellular vesicle release and procoagulant activity in health and in cardiovascular disease. Platelets. 2016;27:805‐811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Giacomazzi A, Degan M, Calabria S, Meneguzzi A, Minuz P. Antiplatelet agents inhibit the generation of platelet‐derived microparticles. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2016;7:1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Behan MWH, Fox SC, Heptinstall S, Storey RF. Inhibitory effects of P2Y12 receptor antagonists on TRAP‐induced platelet aggregation, procoagulant activity, microparticle formation and intracellular calcium responses in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Platelets. 2005;16:73‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Judge HM, Buckland RJ, Sugidachi A, Jakubowski JA, Storey RF. The active metabolite of prasugrel effectively blocks the platelet P2Y12 receptor and inhibits procoagulant and pro‐inflammatory platelet responses. Platelets. 2008;19:125‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Judge HM, Buckland RJ, Holgate CE, Storey RF. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa and P2Y12 receptor antagonists yield additive inhibition of platelet aggregation, granule secretion, soluble CD40L release and procoagulant responses. Platelets. 2005;16:398‐407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chyrchel B, Drożdż A, Długosz D, Stepien E, Surdacki A. Platelet reactivity and circulating platelet‐derived microvesicles are differently affected by P2Y 12 receptor antagonists. Int J Med Sci. 2019;16:264‐275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. van der Pol E, Sturk A, van Leeuwen TG, et al. Standardization of extracellular vesicle measurements by flow cytometry through vesicle diameter approximation. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16:1236‐1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yuana Y, Böing AN, Grootemaat AE, et al. Handling and storage of human body fluids for analysis of extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:29260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gemell CH, Seftoni MV, Yeo EL. Platelet‐derived microparticle formation involves glycoprotein IIb‐IIIa. Inhibition by RGDS and a Glanzmann's thrombasthenia defect. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14586‐14589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nylander S, Femia EA, Scavone M, et al. Ticagrelor inhibits human platelet aggregation via adenosine in addition to P2Y12 antagonism. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1867‐1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kafian S, Mobarrez F, Wallén H, Samad B. Association between platelet reactivity and circulating platelet‐derived microvesicles in patients with acute coronary syndrome Association between platelet reactivity and circulating platelet‐derived microvesicles in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Platelets. 2015;26:467‐473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Suades R, Padró T, Vilahur G, et al. Growing thrombi release increased levels of CD235a+microparticles and decreased levels of activated platelet‐derived microparticles. Validation in ST‐elevation myocardial infarction patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:1776‐1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hess MW, Siljander P. Procoagulant platelet balloons: evidence from cryopreparation and electron microscopy. Histochem Cell Biol. 2001;115:439‐443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zubairova LD, Nabiullina RM, Nagaswami C, et al. Circulating microparticles alter formation, structure, and properties of fibrin clots. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Haemostasis C, Christersson C, Siegbahn A. Microparticles during long‐term follow‐up after acute myocardial infarction association to atherosclerotic burden and risk of cardiovascular events. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:1571‐1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tomaniak M, Gasecka A, Filipiak KJ. Cell‐derived microvesicles in cardiovascular diseases and antiplatelet therapy monitoring—a lesson for future trials? Current evidence, recent progresses and perspectives of clinical application. Int J Cardiol. 2017;226:93‐102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Velik‐Salchner C, Maier S, Innerhofer P, et al. Point‐of‐care whole blood impedance aggregometry versus classical light transmission aggregometry for detecting aspirin and clopidogrel: the results of a pilot study. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1798‐1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hechler B, Gachet C. Purinergic receptors in thrombosis and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:2307‐2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cattaneo M, Schulz R, Nylander S. Adenosine‐mediated effects of ticagrelor evidence and potential clinical relevance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2503‐2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thomas MR, Outteridge SN, Ajjan RA, et al. Platelet P2Y12 inhibitors reduce systemic inflammation and its prothrombotic effects in an experimental human model. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:2562‐2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials