Abstract

Prescription drug misuse (PDM), or medication use without a prescription or in ways not intended by the prescriber, is a notable public health concern, especially in the United States. Accumulating research has characterized PDM prevalence and processes, but age-based or lifespan changes in PDM are understudied. Given age-based differences in the medical or developmental concerns that often underlie PDM, it is likely that PDM varies by age. This review summarizes the literature on PDM across the lifespan, examining lifespan changes in prevalence, sources, motives and correlates for opioid, stimulant, and tranquilizer/sedative (or benzodiazepine) PDM. In all, prevalence rates, sources and motives vary considerably by age group, with fewer age-based differences in correlates or risk factors. PDM prevalence rates tend to decline with aging, with greater use of physician sources and greater endorsement of self-treatment motives in older groups. Recreational motives (such as to get high) tend to peak in young adulthood, with greater use of peer sources or purchases to obtain medication for PDM in younger groups. PDM co-occurs with other substance use and psychopathology, including suicidality, across age groups. The evidence for lifespan variation in PDM is strongest for opioid PDM, with a need for more research on tranquilizer/sedative and stimulant PDM. The current literature is limited by the few studies of lifespan changes in PDM within a single sample, a lack of longitudinal research, little research addressing PDM in the context of polysubstance use, and little research on minority groups, such as sexual and gender minorities.

Keywords: prescription drug misuse, opioid, stimulant, benzodiazepine, lifespan

Prescription drug misuse (PDM) has received increasing focus in the past decade, owing to precipitous increases in overdoses resulting primarily from opioids. PDM is defined in various ways, but a common definition is use without a prescription or in ways not intended by the prescriber. This definition underlies the nationally representative National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)1 and National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) surveys.2,3 While other definitions separate out “abuse” from “misuse,”4 this review will use the NSDUH/NESARC-based definition because of wider use in the literature and to avoid confusion with the DSM-IV diagnosis of substance abuse.

The increased focus on opioid PDM specifically, and PDM more generally, has not just occurred in the United States (US); evidence suggests increases in opioid-related overdose and other consequences in Canada,5,6 the United Kingdom (UK)7 and the rest of the European Union (EU).8 Preliminary 2018 estimates suggest that US opioid-related overdose deaths fell for the first time in over a decade, from 48 958 in 2017 to 47 608 in 2018, or by 2.8%.9 In all, prescription opioid misuse accounted for roughly one-third of opioid overdose fatalities in 2018.9

In addition, there were 11 537 benzodiazepine-related overdose deaths in 2017, with the vast majority of these involving opioids.10 Overdose deaths from prescription stimulant misuse are virtually impossible to disentangle from methamphetamine, but stimulant misuse has been associated with significant substance use treatment demand and emergency department utilization.11 Even when PDM does not lead to overdose, substance use treatment, or other healthcare utilization, it is not benign: the correlates (other variables or outcomes with which PDM is cross-sectionally linked)12-18 and consequences19-23 associated with PDM are significant and suggest a need for intervention.

Across most age groups, PDM prevalence rates trail only those of alcohol, marijuana/cannabis and nicotine/tobacco, with cocaine prevalence rates similar in specific cases (eg, versus prescription stimulants in those 26 and older).24 The increasing focus on PDM referenced earlier has led to better characterization of prevalence in the wider US population and by different subgroups, including by age,16,17,24,25 sex,3,26-28 race/ethnicity,27-31 sexual identity/behavior,32-34 and educational attainment.35-37 PDM sources have been identified and characterized,16,18,38-42 as have motives for engagement.18,43-47 While gaps still clearly exist in the literature on PDM, our understanding of PDM has improved markedly since 2010.

As noted above, there has been increasing research on PDM by age group, with evidence suggesting important age-based differences. There are two key reasons to suspect that examining PDM differences by age group (or using a lifespan/life-stage perspective48) is warranted. First, PDM prevalence varies by age groups, with increases through adolescence49 and a peak in late adolescence or young adulthood.17,50-52 From there, however, the slope of the decline across the lifespan in PDM prevalence depends somewhat on medication class. Older adults have very low rates of prescription stimulant misuse, relative to their opioid or benzodiazepine misuse prevalence, which are still much lower than in other age groups.24,53-55 For substance use disorder (SUD) from prescription misuse, rates are lowest in those 45 and older, with peaks for sedative and stimulant misuse in the 30 to 44 year range.56

Second, the medical conditions or developmental concerns underlying PDM vary considerably by age. For opioid medication, chronic pain and prevalence of significant surgical procedures increase with aging,57-61 furthermore, older adults have greater access to opioid medication, given the frequency with which they are prescribed such medication.62 Increasing access, via prescription, to benzodiazepine medication also occurs with aging,17,62 despite practice guidelines advising against benzodiazepine use in older adults.63 Sleep disturbances64 and significant anxiety65,66 are common in older adults, with benzodiazepines commonly employed as treatment.67 On the other hand, prescription stimulant misuse is often driven by academic and cognitive enhancement motives,38,68,69 and academic demands tend to be concentrated in adolescence and young adulthood. Elevated rates of prescription stimulant misuse in young adult college students and recent graduates supports this idea.35,37

Since PDM varies across the lifespan, our primary aim is to address how PDM prevalence rates, sources, motives, correlates and consequences vary by age. As noted, the literature on PDM across the lifespan is growing, and accumulating evidence strongly suggests differences in medication sources, motives, and, to a lesser extent, correlates across the lifespan. As the current literature on age-based differences in PDM is somewhat limited, this review is intended to be a narrative review, not a systematic review; we do not feel that the literature would support a systematic review, but it is developed enough to highlight key age-based differences in PDM. Finally, we will use the limitations of the current literature to propose topics for future research.

Search methodology

We searched PubMed/MEDLINE, PsycInfo, Scopus, Web of Science (including a cited reference search) and Google Scholar, with the literature search conducted over the November to December 2019 timeframe. Searches used one of the medication class terms: “opioid or analgesic, opioid,” “stimulant or psychostimulant or amphetamine,” or “barbiturate or benzodiazepine or sedative or tranquilizer or anti-anxiety drugs or z-drugs or hypnotic.” All searches also used the term “misuse or nonmedical or abuse” and term for the specific focus: “prevalence,” “source or sources,” “motive or motives or reason or reasons,” “correlate or correlates or consequence or consequences or predictor or predictors or risk factor or risk factors or outcome or outcomes.” Thus, a search for opioid misuse sources would be “opioid AND (source or sources) AND (misuse or nonmedical or abuse).”

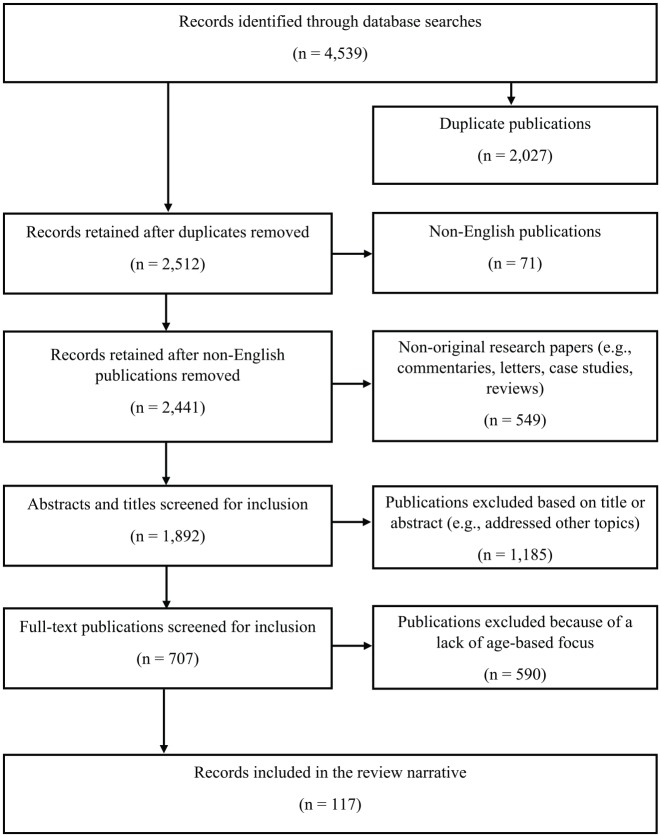

The searches produced over 4500 potential articles for screening, with the screening process outlined in Figure 1. We excluded duplicates (ie, two or more search results flagging the same article in different databases), articles not written in English, articles that were not original research (eg, review articles, commentaries, letters to the editor), articles that focused on non-PDM topics (eg, animal/pre-clinical studies of drug effects, studies of “minor tranquilizers,” which is a term of some antipsychotic medication), and then articles focused only on PDM across the population. We also excluded articles without a clear definition of PDM included. We considered any articles from 2000 to the present (December 2019) for inclusion in the review. In the cases where articles from the general population were retained (eg, Compton and colleagues18), these reports were used to establish population-wide baseline estimates for comparison to specific age groups. This left 117 articles and reports for inclusion in the narrative of the review (see Figure 1). Table 1 includes the 117 articles, summarizing the sample, dataset, design, research objectives and key results; it is organized in order of citation number, in the first column.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of records identified, screened, and included.

Table 1.

Research studies included in the narrative review (organized by citation number).

| Citation | Sample | Dataset, Location | Design | Objective | Results/Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saha et al3 | 36 609 adults (18 and older) | 2012-13 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III), USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine prevalence rates of opioid misuse and prescription opioid SUD, correlates and prevalence of receiving treatment for opioid misuse in adults | Opioid PDM is linked with other substance use, psychopathology and suicidal ideation; prevalence rates of both misuse and prescription opioid use disorder are lower in those 65 and older. |

| Ford & McCutcheon14 | 17 705 adolescents (12-17 years) | 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), USA | Cross-sectional | To examine prescription zolpidem misuse correlates in adolescents | Lifetime zolpidem misuse prevalence of 1.4%; correlates included age, depression, peer substance use, subject other substance use. |

| Mowbray & Quinn16 | 1 13 665, 12 years and older | 2011-12 NSUDH, USA | Cross-sectional | To examine correlates of and sources for opioid misuse across the lifespan | Correlates of opioid misuse are relatively consistent across the lifespan and include other substance use and lower incomes. Older adults were somewhat more likely to use multiple physician sources. |

| Schepis et al17 | 1 14 043, 12 years and older | 2015-16 NSDUH, USA | Cross-sectional | To examine correlates of tranquilizer/ sedative misuse across the lifespan | Tranquilizer/sedative PDM peaks in young adulthood. Sociodemographics were more weakly associated with PDM than mental health or substance use correlates, with more limited associations in those 65 and older. |

| Compton et al18 | 1 02 000 adults (18 and older) | 2015-16 NSDUH, USA | Cross-sectional | To examine the prevalence of stimulant use, misuse, use disorders, sources, and motives in adults | Stimulant PDM peaks in young adulthood, with very low rates in older adults (50 and older); use follows similar patterns, with less steep declines with aging. |

| McCabe et al21 | 4072 high school (HS) seniors (17/18 years) | 1976-2013 Monitoring the Future (MTF), USA | Longitudinal, from 17/18 to 35 years of age | To examine links between opioid exposure (assessed as HS seniors) with the risk of opioid misuse and substance use disorder (SUD) symptoms at age 35 | Appropriate use of opioid medication, without misuse, was not associated with increased risk at 35 years, versus no exposure; adult SUD symptoms were more likely in those with any opioid misuse by 17/18 years. |

| McCabe et al22 | 8362 HS seniors (17/18 years) | 1976-2013 MTF, USA | Longitudinal, from 17/18 to 35 years of age | To examine links between stimulant exposure (assessed as HS seniors) with educational outcomes and SUD symptoms at age 35 | Appropriate stimulant use by 17/18 years was associated with similar outcomes to those without stimulant use. In contrast, those with stimulant misuse had lower educational attainment and greater risk of SUD symptoms at age 35. |

| McCabe et al23 | 8373 HS seniors (17/18 years) | 1976-2013 MTF, USA | Longitudinal, from 17/18 to 35 years of age | To examine the association between opioid misuse characteristics (eg, motives) in HS seniors and risk of SUD symptoms at age 35 | Co-ingestion of an opioid and another drug, misuse of US Schedule II opioid medications, and either appropriate use after misuse or misuse only were associated with especially elevated odds of SUD symptoms at age 35. |

| Schepis25 | 1 74 667, 12 years and older | 2009-11 NSDUH, USA | Cross-sectional | To examine the prevalence and correlates of zolpidem misuse across the population, with a focus on age-based differences | Zolpidem misuse was least common in adolescents (12-17 years) and those 50 and older. Substance use and mental health correlates were more weakly associated with zolpidem misuse in those 50 and older. |

| Smith et al26 | 2717 college undergraduates (17-57 years) | date not provided, local Southern university sample, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine sex differences in stimulant misuse motives, correlates, and perceived acceptability | Academic enhancement motives (eg, to study longer, to concentrate on schoolwork) were most common, with higher rates in female students. |

| Cook et al29 | 11 663 adults (18 and older) | January 2013 to September 2015, Electronic Health Records sample from Northeastern USA | Cross- Sectional | To examine racial and ethnic differences in prescription benzodiazepine use and misuse | Prescription benzodiazepine use increased with age in the sample, with a greater prevalence of more than one such prescription with age. |

| Martins et al31 | 36 781 young adults (18-25 years) | 2008-10 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the relationship between PDM and current educational attainment in young adults | Prescription opioid misuse and use disorder were less likely in current college students, while stimulant misuse and use disorder were more likely in current college students. |

| McCabe et al36 | 1 06 845 young adults (18-25 years) | 2009-14 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine PDM prevalence, sources and correlates of sources, with a focus on educational status, in young adults | PDM prevalence varied by educational status, with weaker relationships between source and educational status. Those with multiple sources had the highest prevalence of other substance use and SUD, with poor profiles in those using theft or purchases. |

| Schepis et al37 | 13 585 adolescents (12-17 years) and 14 553 young adults (18-25 years) | 2015 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine differences by educational status in prescription use, PDM and PDM use disorder symptoms prevalence in adolescents and young adults | PDM prevalence was highest in adolescents who had dropped out of school or who were at risk for dropout. In young adults, prevalence varied by educational status: highest opioid rates in those not in school and highest stimulant rates in those in college or who were recent graduates. |

| Garnier-Dykstra et al38 | 1253 college undergraduates (17-19 years) | 2004-2009, local mid-Atlantic sample, USA | Longitudinal | To examine prescription stimulant misuse prevalence, motives, sources, correlates, and routes of administration | Peers remained the most common source of stimulant medication across college, though motives changed: academic motives increased, which misuse to experiment decreased over college. |

| McCabe et al40 | 18 549 HS seniors (17/18 years) | 2009-16 MTF, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine latent classes of adolescent PDM sources and link classes to substance use and sociodemographic correlates | Five latent classes were identified, with the greatest concurrent substance use found in the multiple source class and the lowest concurrent use in the leftover medication (ie, misusing one’s own medication) class. |

| Schepis et al41 | 1 03 920 adolescents (12-17 years) | 2009-14 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine PDM sources in adolescents, educational differences in sources and correlates of specific sources | Use of friends or relatives for free to obtain medication for PDM was most common, followed by use of physician sources or purchases. Multiple source use was associated with the highest odds of other substance use and SUD, with elevated odds in those using purchases. |

| Rabiner et al44 | 3407 college undergraduates (17-19 years) | date not provided, local Southeastern sample, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine stimulant misuse motives and perceived consequences, and to examine the potential influence of attentional variables in college undergraduates | Attentional difficulties were associated with stimulant misuse, and the most common motives were academic enhancement-related. |

| Han et al45 | 51 200 adults (18 and older) | 2015 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence of opioid use, misuse, use disorders, sources, and motives in adults | Prescription opioid use increased with age, with the highest rates in those 50 and older; in contrast, misuse decreased from young adults (18-25 years) to adults 50 and older. |

| Blevins et al46 | 199 college undergraduates (18 and older; mean age 19.7) | date not provided, local Southeastern sample, USA | Cross-Sectional | To evaluate the correlates of and motives for stimulant misuse in an undergraduate sample | Academic enhancement motives (eg, to study) are more common than recreational motives (eg, to get high) in college undergraduates. |

| Messina et al47 | 1016 college undergraduates (19 and older; mean age 20.5) | date not provided, local Southeastern sample, USA | Cross-Sectional | To evaluate motive patterns among college students engaged in PDM | Motives in undergraduates appear to be separable into self-treatment and recreational groups, with the highest prevalence of self-treatment only motives, followed by combined motives and then recreational-only motives. |

| Austic et al51 | 5185 adolescents (12-18 years) | 2009-12, southeastern Michigan school-based sample, USA | Cross-Sectional | To evaluate peak annual incidence rates for medical use and PDM of controlled medications used in PDM among adolescents | Incidence of opioid PDM peaked at 16 years of age for both opioid medical (appropriate) use and for opioid PDM, with evidence of earlier peaks in younger cohorts. |

| Dollar & Ray52 | 38 067 adults (18 and older) | 2010 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To evaluate the relationship between social bonds and PDM in adults | PDM peaks in young adulthood, with evidence that marriage is associated with lower PDM prevalence across adults. |

| Schepis & McCabe53 | 22 489 older adults (50 and older) | 2002-03 and 2012-13 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To evaluate trends in PDM prevalence among older adults over a 10-year period | Opioid and tranquilizer/sedative prevalence increased over the 2002/03 to 2012/13 timeframe in older adults, with the strongest evidence in the 50 to 64 year cohort. Lifetime stimulant PDM also increased. |

| Schepis et al55 | 3 36 643, 12 years and older | 2009-14 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine opioid PDM prevalence, sources and correlates of sources; particular focus was on age-based changes | Opioid PDM prevalence peaked in young adults (18-25 years) and decreased to adults 65 years and older. Use of physician sources increased with aging, while multiple source use peaked in young adults and decreased with aging; multiple source use was associated with the highest odds of prescription opioid use disorder symptoms and other substance use in adults 50 and older. |

| Paulozzi et al62 | N not provided, all residents of eight US states included | 2013, Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine controlled medication prescribing rates by age, race/ethnicity, and state across the population | Older adults, 50 years and older, had the highest overall rates of prescription opioid or benzodiazepine prescriptions, with rates slightly higher in the 50 to 64 year group. |

| McCabe et al70 | 1 14 043 adults (18 and older) | 2015-16 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine age-based differences in controlled medication use and PDM prevalence, and SUD from PDM | Prescription opioid, tranquilizer and sedative use increased from young adults (18-25 years) to older adults (50 and older), while PDM decreased. Stimulant use was less variant by age, but stimulant PDM also decreased by age. |

| Guy et al71 | N not provided, over 59 000 pharmacies and 88% of prescriptions included | 2006-15, retail prescription data from QuintilesIMS | Cross-Sectional | To examine controlled prescription rates by age group, race/ethnicity, other sociodemographics and US county. | Prescription opioid and benzodiazepine use rates are highest in older adults, increasing with aging. |

| Arria et al72 | 1253 college undergraduates (17-19 years) | 2004-2012, local mid-Atlantic sample, USA | Longitudinal | To examine eight-year longitudinal patterns in incidence and prevalence of substance use, including PDM | Peak PDM prevalence rates were at 20 years of age across stimulants, opioids and tranquilizers, with the highest rates in stimulants; modal age of onset was 20 (opioids, stimulants) or 21 years (tranquilizers). |

| Hu et al73 | 5 42 556, aged 12 to 34 years | 2004-13 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine age-related patterns in opioid PDM across a 10-year period | Peak opioid PDM occurs between 18 to 21 years, plateaus and declines in the early 30s; in contrast, prescription opioid use disorder prevalence increases into the early 30s. |

| McCabe et al74 | 71 980 HS seniors (17/18 years) | 1977-2006 MTF, USA | Longitudinal | To examine the course of past-year PDM over an eight-year period, from 17/18 years of age to 25/26 years | Opioid PDM prevalence and frequency decline steadily from 17/18 years of age to 25/26 years; stimulant, sedative and tranquilizer PDM prevalence and frequency are roughly steady over this period. |

| Wall et al75 | 73 026 adults, aged 18 to 64 years | 2013-14 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine adult generational differences in the sequence of drug initiation, with a focus on prescription opioids | “Millennials” (birth years 1979-1996) had a higher lifetime opioid PDM prevalence than “Generation X” (1964-1979) or “Baby Boomer” (1949-1964) individuals, with progressively increasing likelihood of opioid PDM as the first substance use. |

| Martins et al76 | 62 243 adults, aged 18 to 57 years | 1991-92 National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey (NLAES) and 2001-02 NESARC-I, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the 10-year change in lifetime and past-year prescription opioid use disorder in adults | Lifetime and past-year prescription opioid use disorder prevalence rates increased over the 10-year period between surveys, even after controlling for birth cohort. |

| McCabe et al77 | 27 268 HS seniors (17/18 years) | 1976-2005 MTF, USA | Longitudinal | To examine the longitudinal prevalence of past-year opioid PDM from 17/18 years to 23/24 years | Ongoing opioid PDM, or PDM at multiple timepoints increased over the longitudinal study period, with ongoing PDM associated with greater odds of concurrent other substance use behaviors. |

| West & Dart78 | 57 681 adults, aged 20 and older | 2006-14 Poison Center Call Data, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine trends in prescription opioid misuse and serious outcomes from such misuse in two age cohorts (20-59 years and 60 and older) | Opioid misuse rates increased over 2006-10 in adults 20 to 59 years, then declined to 2014; in contrast, rates increased over the study period in adults 60 and older, though increases declined over time; rates of serious medical outcomes increased in older adults, as well. |

| West et al79 | 1 84 136 adults, aged 20 and older | 2006-13 Researched Abuse, Diversion and Addiction-Related Surveillance System Data | Cross-Sectional | To examine trends in prescription opioid abuse, misuse and associated fatality rates in two age cohorts (20-59 years and 60 and older) | Opioid abuse and misuse were less prevalence in the older cohort (60 and older), but mortality in this older adult group increased over the study period, specifically use with suicidal intent. |

| Schuler et al80 | 8228 individuals engaged in past-year opioid misuse, 12 and older | 2015-17 NSUDH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine age-related changes in opioid PDM sources and motives in a population-wide sample engaged in opioid PDM | Opioid sources and motives changed over the life course, with greater use of physician sources with aging and greater endorsement of opioid PDM for pain relief with aging; in contrast, opioid PDM to get high or to experiment peaked at younger ages. |

| Schepis & Krishnan-Sarin81 | 18 678 adolescents (12-17 years) | 2005 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence and correlates of PDM in adolescents | Opioid misuse had the highest prevalence rate; correlates of PDM included other substance use, poorer grades and psychopathology. Among those with PDM, SUD symptoms were more likely in those with past-year major depression or frequent PDM. |

| Schepis & Krishnan-Sarin82 | 36 992 adolescents (12-17 years) | 2005-06 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine PDM sources, differences in sources by sex and race/ethnicity and in correlates of sources in adolescents | The most common source of medication for PDM is from friends or family for free, with evidence of sex- and race/ethnicity-based differences. Those who purchased medication for misuse had the greatest odds of other substance use. |

| Ford et al83 | 1 06 845 young adults (18-25 years) | 2009-14 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine sources used by friends or family members, who then divert opioid medication for misuse to respondents | Physician sources are the most common source for friends or relatives who then divert opioid medication. Multiple source use by friends/family who divert opioids are associated with opioid use disorder and any SUD, with elevated risk in those whose friends/family purchased opioids. |

| Rigg et al84 | 125 adults (20-62 years) with past-year opioid misuse or heroin use | July 2017 to July 2018, Southeastern Pennsylvania, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine age-based patterns in opioid misuse initiation and changes in sources over time | The vast majority of opioid misuse initiation occurs in young adulthood (18-25 years); patterns of sources used changes over time, with greater reliance on purchases one year after initiation. |

| Han et al85 | 1 06 845 adults (18 and older) | 2015 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine opioid use, misuse, misuse motives, and opioid use disorder correlates in adults | Opioid misuse for pain relief was the main motive for most engaged in misuse, with misuse to get high or to relax was less common, at around 10%. Any opioid PDM was associated with greater odds of other substance use or suicidal ideation, though pain relief as the most important motive was linked to lower relative odds than other motives. |

| Ashrafioun et al86 | 45 074 adults (18 and older) | 2015-17 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine links between past-year suicidal ideation, plans and attempts and past-year opioid use and/or misuse | Versus adults with opioid use but not misuse, those engaged in misuse had higher odds of suicidal ideation and plan. Those with both pain and non-pain motives had the highest odds and had higher odds of a suicide attempt than those with use without misuse. |

| McCabe et al87 | 2964 secondary school students (11-18 years) | 2011-12 Southeastern Michigan school sample, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine prevalence of opioid misuse motives and differences in sociodemographics, substance use and opioid diversion in adolescents by motive | Pain relief motives were endorsed by the majority of the sample (motives were non-exclusive), and non-pain relief motives were associated with problem substance use and opioid diversion. |

| McCabe & Cranford88 | 12 431 HS seniors (17/18 years) | 2002-06 MTF, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine latent classes of adolescent PDM motives and link motive classes to odds of problematic substance use indicators (eg, non-oral PDM) in HS seniors | Higher rates of recreational opioid misuse motives than pain relief motives were found in adolescents; for tranquilizer medication, self-treatment was more common. Recreational motives were associated with greater odds of other problematic substance use. |

| McCabe et al89 | 3639 college undergraduates (mean age, 19.9 years) | 2005, large public university, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine PDM subtypes, based on motives, route of administration, and co-ingestion with alcohol in undergraduates | The recreational and mixed subtypes, marked by recreational motives, non-oral administration, and/or co-ingestion were associated with greater odds of other problematic substance use. |

| Schepis et al90 | 5826 individuals engaged in past-year opioid misuse, 12 and older | 2015-16 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine age-based changes in opioid PDM motives across the population and correlates of motives in adults 50 years and older | Opioid PDM for pain relief increased with aging, while such PDM to experiment or get high decreased. The presence of non-pain relief motives in older adults (50 years and older) was associated with elevated odds of other substance use and suicidal ideation. |

| Levi-Minzi et al91 | 88 adults aged 60 and older | Year not provided, South Florida Health Survey, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the sociodemographic, health and other substance use associated with opioid misuse in older adults; sources and motives were also examined | Provided preliminary evidence that pain relief motives for opioid misuse may be more prevalent in older adults than across the general population or in younger groups. |

| Ghandour et al92 | 570 university students (mean age 19.9 years) | 2010, large private university, Lebanon | Cross-Sectional | To examine differences between appropriate opioid medication use and misuse, in terms of other substance use correlates; misuse motives were also examined in university students | Appropriate medication use was not linked to greater concurrent substance use (versus non-use), but misuse was. Misuse for non-self-treatment motives was linked to the highest prevalence rates of other substance use outcomes. |

| Boyd et al93 | 2627 adolescents (mean age, 14.8 years) | 2009-10, southeastern Michigan school-based sample, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine differences in correlates between appropriate opioid use and opioid misuse, and of correlates for opioid misuse motives | Those engaged in appropriate use often had greater levels of psychological symptoms than those without use, but the highest levels of both psychological symptoms and other substance use were in those with opioid PDM, especially those with recreational motives. |

| Chang94 | 130 older adults (50 and older) | Year not provided, medical and senior community settings, western New York, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence and correlates of opioid misuse in older adults | Opioid PDM was associated with younger age (within the 50 and older cohort), psychopathology, pain interference and greater other substance use. |

| McCabe et al95 | 4522 HS seniors (17/18 years) | 2002 MTF, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence and correlates of opioid misuse in HS seniors. | Those engaged in opioid misuse were more likely to be white, male, have lower grades and have higher prevalence rates of other concurrent substance use. |

| McCabe et al96 | 10 904 college undergraduates (18 and older) | 2001 College Alcohol Study, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence and correlates of opioid misuse in college students | Those engaged in opioid misuse were more likely to be white and have poorer GPAs; they also had much greater odds of other substance use and problematic use behaviors (eg, DUI). |

| Schepis & McCabe97 | 14 667 older adults (50 years and older) | 2012-13 NESARC-III, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the physical health, mental health and SUD correlates of opioid PDM by recency of such PDM in older adults | Any opioid PDM was associated with elevated rates of SUD, psychopathology and physical health concerns, with the worst profiles in those with ongoing or persistent PDM (ie, those with both past-year and prior to past-year opioid PDM). |

| Catalano et al98 | 912 adolescents/ young adults (15/16-21 years of age) | 1993-2006 Raising Healthy Children Study, Pacific Northwest, USA | Longitudinal | To examine substance use sequencing (including opioid PDM), polysubstance use and related consequences in emerging adults | Polysubstance use is very common, at over 90%, in emerging adults engaged in opioid PDM. Opioid PDM alone appears to account for fewer consequences than other substance use. |

| Grigsby & Howard99 | 26 033, 12 and older, engaged in past-month opioid PDM or other substance use | 2016 NSUDH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence and correlates of past-month opioid PDM and combined opioid PDM and other substance use | Combined past-month opioid PDM with other substance use was more common in adolescents (12-17 years) and young adults (18-25 years) than in adults 26 years and older. |

| Schepis & Hakes100 | 1755 adults (18 and older) | 2001-02 NESARC-I, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the correlates of development of opioid dependence and time to dependence among adults with a history of opioid misuse | Earlier age of opioid misuse initiation was associated with greater odds of opioid dependence and a slower time to dependence. Alcohol use disorder was also associated with a more rapid progression to opioid dependence. |

| Arkes & Iguchi101 | 164 870, 12 years and older | 2001-03 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine PDM correlates across age groups and see if age-based differences exist across the population | In particular, opioid misuse correlates varied by age, with weaker correlate associations with aging; this effect was much less pronounced for stimulant misuse. |

| Boggis & Feder102 | 4 82 639 adults (18 and older) | 2002-2014 NSUDH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine trends in and correlates of past-year benzodiazepine misuse among adults engaged in opioid PDM | Past-year benzodiazepine misuse was less likely in those over the age of 26, versus those 18 to 25 years, but frequency of benzodiazepine PDM was elevated in the 26 and older group. |

| Kuramoto et al103 | 37 933 adults (18 and older) | 2009 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine whether opioid misuse is linked to suicidality and whether relationships vary by state of misuse and presence of opioid use disorder in adults | Persistent opioid misuse (past-year and prior to past-year) was most strongly associated with suicidal ideation, as was presence of an opioid use disorder; among those with ideation, persistent and past-year onset opioid misuse were linked to a suicide attempt. |

| Martins et al104 | 34 653 adults (18 and older) participating in both NESARC waves | 2001-02 NESARC-I and 2004-05 NESARC-II, USA | Longitudinal | To examine bidirectional influences of baseline opioid PDM and psychopathology on wave 2 opioid PDM and psychopathology in adults | Psychopathology and opioid PDM evidenced robust and bidirectional relationships, but baseline opioid use disorder did not predict psychopathology at wave 2. |

| Martins et al105 | 43 093 adults (18 and older) | 2001-02 NESARC-I, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine cross-sectional relationships between opioid PDM and psychopathology in adults | Preexisting psychopathology was associated with a greater likelihood of later opioid PDM initiation, and preexisting opioid PDM was associated with greater odds of psychopathology onset. |

| Schepis & Hakes106 | 34 653 adults (18 and older) participating in both NESARC waves | 2001-02 NESARC-I and 2004-05 NESARC-II, USA | Longitudinal | To examine the influence of wave 1 PDM on the incidence and recurrence of psychopathology in adults | Any lifetime PDM at baseline was associated with the incidence of psychopathology, with opioid PDM linked to recurrence of SUD and tranquilizer PDM linked to anxiety disorder recurrence. |

| Schepis & Hakes107 | 34 653 adults (18 and older) participating in both NESARC waves | 2001-02 NESARC-I and 2004-05 NESARC-II, USA | Longitudinal | To examine the influence of baseline PDM frequency on the incidence and recurrence of psychopathology in adults | Any PDM was associated with a greater likelihood of psychopathology recurrence and incidence, with weaker effects for greater frequency of PDM. |

| Schepis & McCabe108 | 1 66 617, 12 years and older | 2005-07 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine relationships between age of PDM initiation and lifetime and past-year major depression; also, to examine age of major depression onset and lifetime and past-year PDM across the population | Earlier onset of either PDM or major depression increased the odds of the other, both past-year and lifetime. Age cohorts evidenced differential relationships between PDM and major depression, with stronger effects on PDM of early major depression onset in those 65 and older. |

| Huang et al109 | 43 093 adults (18 and older) | 2001-02 NESARC-I, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence and correlates of PDM in adults | PDM is robustly linked to many forms of psychopathology and other substance use disorders. |

| Ford & Perna110 | 55 268 adults (18 and older) | 2012 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the relationship between PDM and suicidal ideation in adults | Both any PDM and opioid PDM specifically are linked to suicidal ideation in adults. |

| Ashrafioun et al111 | 41 053 adults (18 and older) | 2014 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the relationship between frequency of past-year opioid PDM and past-year suicidality indicators in adults | Any opioid PDM was linked to suicidal ideation, planning and attempts, with frequency related to ideation in a linear manner. Conversely, planning and attempts were only linked to opioid PDM in those engaged in weekly or more frequent opioid PDM. |

| Edlund et al112 | 1 12 600 adolescents (12-17 years) | 2008-12 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the relationship between opioid PDM and major depression, other substance use, sociodemographics and religiosity in adolescents | Major depression was linked to both opioid PDM and opioid dependence in adolescents; when major depression and opioid PDM were comorbid, major depression preceded opioid PDM more often. |

| Zullig & Divin113 | 22 873 young adult college undergraduates (18-25 years) | 2018 Fall National College Health Assessment (NCHA), USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the associations between PDM and depressive symptoms or PDM and suicidality in college students | Feelings of hopelessness, sadness and/or depression, and of suicidal urges were linked to PDM, with specific links differing slightly by medication class. |

| Bouvier et al114 | 199 young adults (median age, 25 years) | 2015-16 Rhode Island Young Adult Prescription Drug Study, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine depressive symptoms in young adults engaged in past-month opioid PDM | Young adults engaged in opioid PDM have high levels of depressive symptoms, with differential motives in those with elevated depression scores. |

| Davis et al115 | 889 college undergraduates (mean age 21.7 years) | Year not provided, south-central public university, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine links between opioid PDM and suicidality in college students | Opioid PDM was linked to suicidal ideation, planning and attempts in college students. |

| Schepis et al116 | 17 608 older adults (50 years and older) | 2015-16 NSUDH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the relationship between past-year suicidal ideation and either past-year opioid or benzodiazepine PDM in older adults | Both opioid and benzodiazepine PDM were associated with past-year suicidal ideation in older adults, even after controlling for sociodemographic, substance use, physical health and mental health variables associated with suicidality. |

| Brooks et al117 | 1036 older adults (50 years and older) | 2005-13 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), USA | Cross-Sectional | To investigate the relationship between opioid medication potency and depressive symptoms in older adults engaged in opioid use. | High depressive symptom levels were linked to higher potency opioid use, but this relationship only held for those with arthritis after controlling for covariates. |

| Salas et al118 | 1 10 428, 12 years and older | 2012-13 NSUDH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the effects of race/ethnicity on the major depression link to prescription opioid use disorder across the population | While major depression and prescription opioid use disorder were significantly associated in white individuals, this link was not significant in black individuals. |

| Cochran et al119 | 318 older adults (50 years and older) | Year not provided, four southwestern Pennsylvania community pharmacies, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine whether prescription opioid misuse characteristics and correlates differ between older adults aged 50 to 64 and those 65 and older | Correlates differed by age cohort, with an association between PTSD and opioid misuse in those 50 to 64 years but not those 65 and older. |

| Perlmutter et al120 | 58 486 adults, 26 years and older | 2011-13 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine whether prescription opioid or stimulant misuse were linked to employment status in adults 26 years and older | Compared to those in full-time jobs, unemployed individuals had the highest odds of opioid misuse, while those not in the workforce had the highest odds of stimulant misuse. |

| Day & Rosenthal121 | 26 322 older adults (50 years and older) | 2015-17 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine whether living along and/or marital status was associated with odds of past-year opioid misuse, benzodiazepine misuse or combined misuse in older adults | Older adults with combined opioid and benzodiazepine misuse in the past-year were more likely to be unmarried than those without misuse; specifically, odds were significantly elevated in those who were never married or divorced/separated, but not those who were widowed. |

| Olfson et al122 | N not provided, over 33 000 pharmacies and 60% of prescriptions included | 2008 IMS Health Retail Prescription data, USA | Longitudinal | To examine prescription benzodiazepine use and patterns of use (eg, duration) over a year-long period across the population | Rates of benzodiazepine prescriptions increased with age, with the highest rates in the 65 to 80 year cohort. This pattern was similar for long-acting benzodiazepine medications. |

| Palamar et al123 | 5 60 099, 12 years and older | 2005-14 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine trends in prescription tranquilizer misuse and trends in other substance use among those engaged in tranquilizer misuse | Tranquilizer PDM increased notably over the 2005-14 study period in adults 50 and older, with declines or small increases in other age groups. |

| Maust et al124 | 86 186 adults (18 and older) | 2015-16 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To evaluate prescription benzodiazepine use, misuse and misuse motives. | Adults 50 to 64 years had the highest rates of benzodiazepine use, with those 50 and older more likely to use benzodiazepines more often than prescribed and to help with sleep. |

| Schepis & McCabe125 | 3162, 12 years and older | 2009-14 NSUDH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To evaluate tranquilizer/sedative sources by age group and correlates of sources in adults 50 years and older | Use of physician sources increased with aging, though these were associated with greater concurrent substance use and psychopathology in older adults (versus use of family or friends for free as a source). |

| Boyd et al126 | 1086 secondary school students (12-18 years) | 2005, southeastern Michigan school sample, USA | Cross-Sectional | To evaluate motives for PDM in school-attending adolescents and link motives to different patterns of other substance use | Recreational motives were associated with a higher prevalence of problematic other drug use, versus self-treatment motives. Also, to decrease anxiety, to help sleep, and to get high were the most common motives. |

| Abrahamsson & Hakansson127 | 58 000, 15 to 64 years | 2008-09, Swedish national household survey, Sweden | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence and correlates of PDM in the Swedish general population | Females were more likely than males to engage in PDM, which is contrary to many results in the USA; otherwise, PDM was associated with poorer health and other substance use. |

| Snipes et al128 | 767 college undergraduates (18-25 years) | Year not provided, university setting not provided, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the link between religiosity and PDM in college students | Males were more likely than females to report PDM. Higher levels of religiosity were associated with lower odds of PDM engagement. |

| Blanco et al129 | 1 02 000 adults (18 and older) | 2015-16 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence and correlates of benzodiazepine use and misuse in adults | Benzodiazepine misuse was more common in younger individuals, males, and those with lower educational attainment, suicidal ideation and other substance use. |

| McCabe et al130 | 8373 HS seniors (17/18 years) | 1976-2013 MTF, USA | Longitudinal | To examine the later life (age 35) SUD associated with tranquilizer/sedative use and misuse by the age of 18. | Those with appropriate tranquilizer/sedative use only at age 18 did not have elevated odds of SUD symptoms over those without any use; in contrast, those with misuse or both use and misuse had higher rates of SUD symptoms at age 35. |

| Rigg & Ford131 | 19 264 adolescents (12-17 years) | 2011 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the correlates of benzodiazepine misuse in adolescents | In multivariate models, the strongest correlates of benzodiazepine misuse were male sex, greater numbers of negative life events, and other substance use. |

| Tucker et al132 | 12 904 secondary school students (12-18 years) | 2008-14, southern California after-school substance use prevention program, USA | Longitudinal | To examine the correlates of early PDM initiation and relationships between early initiation and future psychosocial functioning | PDM initiation was associated with delinquent behavior in adolescents, including school suspensions and engaging in fights. |

| Ford et al133 | 19 430 adolescents (12-17 years) | 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA), USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine relationships between PDM and neighborhood characteristics in adolescents | PDM was more common in adolescents living in disorganized or disadvantaged neighborhoods that had lower levels of mutual assistance among residents. |

| Boyd et al134 | 34 653 adults (18 and older) participating in both NESARC waves | 2001-02 NESARC-I and 2004-05 NESARC-II, USA | Longitudinal | To examine whether baseline tranquilizer/sedative PDM is associated with continued PDM, SUD from PDM or other SUD at wave 2 in adults | The majority of adults engaged in tranquilizer/sedative PDM at baseline ceased by the time of the three-year follow-up, with very low rates of tranquilizer/sedative SUD; presence of any other SUD was quite high, though, in those with baseline tranquilizer/sedative PDM. |

| Austic135 | 2 50 910 adolescents and young adults (12-21 years) | 2004-12 NSUDH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the peak ages of PDM incidence in individuals aged 12 to 21 years | Peak incidence of PDM is between 17 and 19 years, with evidence of sex differences. |

| Striley et al136 | 5585 females, 10 to 18 years | 2008-11 National Monitoring of Adolescent Prescription Stimulants Study (N-MAPSS), USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the correlates of stimulant PDM in a female adolescent sample | Stimulant PDM incidence and prevalence rose with age, with such PDM strongly associated with other problematic substance use; multiple source use was somewhat common, at 18.1%. |

| Wang et al137 | 10 048, 10 to 18 years | 2008-11 N-MAPSS, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine stimulant use and misuse prevalence and patterns, and to examine correlates of use/misuse patterns | Those with misuse only had the highest prevalence rates of other substance use, with individuals with both misuse and use having elevated rates. Prevalence increased through with age. |

| Lasopa et al138 | 10 048, 10 to 18 years | 2008-11 N-MAPSS, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine stimulant diversion (ie, receiving, giving or selling medication) in adolescents | Diversion was common among those with a stimulant prescription, with slightly over half engaged in diversion. |

| Bachmann et al139 | 3 683 488, zero to 19 years | Pharmacy and other administrative data sources in five countries, USA, UK, Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark | Cross-Sectional | To examine age- and year-based patterns in stimulant use in individuals 19 years and younger. | Stimulant use patterns differ from medication use patterns for opioid or tranquilizer/sedative medication, with peaks for stimulant use in early to mid-adolescence. Stimulant use generally increased in the examined countries over time. |

| Compton et al140 | 1 02 000 adults (18 and older) | 2015-16 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence and correlates of stimulant use and misuse in adults | Stimulant misuse was associated with greater use of other substance, with the most common source being friends/family for free; the most common motives were cognitive enhancement (eg, to concentrate) in nature. |

| McCabe & Boyd141 | 9161 undergraduate students (18 years and older) | 2003, large public Midwestern university, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine medication sources for PDM in undergraduate students | Peer sources were the most commonly used sources across medication classes, whether the medication was purchased from a peer for obtained for free. |

| Rabiner et al142 | 115 undergraduate students (18 years and older) | 2007, two southeastern universities, USA | Cross- Sectional | To examine stimulant misuse and diversion prevalence among undergraduates with a stimulant prescription | Diversion of medication to peers was somewhat common, at 26%. Motives were primarily academic-related (eg, to study) in nature. |

| Chen et al143 | 4945, 12 and older | 2006-11 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine stimulant misuse sources and correlates of specific sources used | There were higher relative rates of physician source in adolescents and higher relative rates of friend/relative or illegal (eg, theft) sources in young adults, versus adolescents. |

| Teter et al144 | 15 098 HS seniors (17/18 years) | 2009-15 MTF, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine patterns of academic-related motives for stimulant misuse in HS seniors | Stimulant PDM involving “to study” as a motive was common, at nearly half of participants, but stimulant PDM only “to study” was rare, at less than 10%. |

| Whiteside et al145 | 4389 emergency department (ED) patients, 14 to 20 years | 2010-11, University of Michigan ED, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence, correlates and severity of stimulant misuse among those 14 to 20 years of age presenting at the ED | Stimulant PDM was strongly associated with other drug use and delinquent behavior, with weaker associations between more severe stimulant PDM and other ED visits in the past-year. |

| Herman-Stahl et al146 | 17 709 adolescents (12-17 years) | 2002 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the correlates of stimulant misuse in adolescents | Mental health treatment and other substance use in the past-year were associated with stimulant misuse, with evidence of racial/ethnic differences. |

| Herman-Stahl et al147 | 23 645 young adults (18-25 years) | 2002 NSDUH, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the correlates of stimulant misuse in young adults | Other substance use, college enrollment, and non-white race/ethnicity were associated with stimulant misuse. |

| McCabe et al148 | 9161 undergraduate students (18 years and older) | 2003, large public Midwestern university, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence and correlates of appropriate stimulant use and stimulant misuse in college undergraduates | Stimulant misuse was associated with lower GPAs and fraternity/sorority membership. In addition, later initiation of stimulant use (of any kind) was associated with greater odds of problematic substance use. |

| Teter et al149 | 9161 undergraduate students (18 years and older) | 2003, large public Midwestern university, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence and correlates of stimulant misuse in college undergraduates; motives were also examined | Prescription stimulant misuse was associated with high prevalence rates of other substance use. While aiding concentration was the most common motive, “to get high” was endorsed by over 40% of participants engaged in stimulant misuse. |

| McCabe et al150 | 4755 secondary students (12/13-17/18 years) | 2009-13 Southeastern Michigan school sample, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine relationships between other substance use and early onset of appropriate stimulant use or misuse in adolescents | For appropriate use, later stimulant initiation was associated with greater odds of other substance use problems; in contrast, earlier initiation of stimulant misuse was associated with greater odds of other substance use problems. |

| Wilens et al151 | 298 undergraduate students (mean age, 20.6 years) | Year not provided, Boston, Massachusetts area colleges, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the neuropsychological correlates of stimulant misuse in undergraduate students | Those with stimulant misuse had a large number of diverse neuropsychological deficits (eg, working memory, executive functioning), as compared to those without misuse; these results were moderated by ADHD symptoms, with greater deficits in those with greater ADHD symptoms. |

| Wilens et al152 | 298 undergraduate students (mean age, 20.6 years) | Year not provided, Boston, Massachusetts area colleges, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the substance use and mental health correlates of stimulant misuse in undergraduate students | Stimulant misuse was associated with higher rates of other SUDs and greater ADHD symptoms, versus those with no misuse; of a subset of those with stimulant misuse, two-thirds had symptoms of a stimulant SUD. |

| Grant et al153 | 3659 undergraduate and graduate students (ages not provided) | Year not provided, large Midwestern university, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine relationships between stimulant misuse and substance use or psychological characteristics among individuals in higher education | Stimulant misuse was linked to higher prevalence rates of other substance use, lower GPAs, greater impulsivity and riskier sexual behavior engagement. |

| Verdi et al154 | 807 college graduate students (ages not provided) | Year not provided, five public university campuses, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine relationships between stimulant misuse and psychological variables (eg, anxiety, depression) in graduate students | Stimulant misuse was linked to higher levels of anxiety, stress and ADHD symptoms (but not depressive symptoms). |

| Dussault & Weyandt155 | 3639 college undergraduates (18 years and older) | 2010, five university campuses, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine relationships between stimulant misuse and psychological variables (eg, anxiety, depression) in undergraduates | Fraternity/sorority membership was associated with a higher prevalence rate of stimulant misuse. Levels of anxiety, stress, internal impulsivity, and internal restlessness were elevated among those engaged in stimulant misuse. |

| Teter et al156 | 3639 college undergraduates (mean age, 19.9 years) | 2005, large public university, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine relationships between stimulant misuse frequency and non-oral stimulant misuse and depressive symptoms in undergraduate students | Individuals with monthly or more frequent stimulant misuse and individuals with non-oral stimulant misuse had over 100% greater odds of depressed mood than those without misuse; those with less frequent misuse or oral misuse only did not have higher odds of depressed mood. |

| Jeffers & Benotsch157 | 707 undergraduate students (18-25 years) | 2012, large eastern university, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine the prevalence and correlates of stimulant misuse specifically for weight loss in undergraduate students | Among undergraduate students engaged in stimulant misuse for weight loss, concurrent disordered eating behaviors or weight suppression efforts are common. |

| Teter et al158 | 5389 undergraduate students (18 years and older) | 2005, large Midwestern university, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine stimulant misuse prevalence, motives and routes of administration in undergraduate students | Oral administration was most common, though over one-third of participants snorted the stimulant. Weight loss motives were significantly more common in females than in males. |

| McCabe et al159 | 12 431 HS seniors (17/18 years) | 2002-2006 MTF, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine prevalence rates of simultaneous co-ingestion (ie, in the same use episode) of prescription stimulant medication with other drugs in HS seniors | Among those engaged in past-year stimulant misuse, nearly two-thirds also engaged in co-ingestion with another substance, most commonly alcohol or cannabis. Those engaged in co-ingestion had higher rates of poor misuse indicators (eg, non-oral administration) than those without co-ingestion. |

| McCabe et al160 | 12 441 HS seniors (17/18 years) | 2002-2006 MTF, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine prevalence rates of simultaneous co-ingestion (ie, in the same use episode) of prescription opioid medication with other drugs in HS seniors | Nearly 70% of those who misused opioid medication also engaged in co-ingestion, with alcohol and cannabis as the most commonly co-ingested substances. Those engaged in co-ingestion had much higher rates of other substance use and poor misuse indictors than those without co-ingestion. |

| Schepis et al161 | 11 444 HS seniors (17/18 years) | 2002-2006 MTF, USA | Cross-Sectional | To examine prevalence rates of simultaneous co-ingestion (ie, in the same use episode) of prescription tranquilizer/sedative medication with other drugs in HS seniors | Of those with past-year tranquilizer/sedative misuse, 72.6% engaged in co-ingestion; as with stimulant or opioid medication, alcohol and cannabis were the most commonly co-ingested substances, and those engaged in co-ingestion had significantly higher rates of other substance use and non-oral PDM. |

Notes: The table is organized by the first column of citations, by citation number (in superscript).

Prescription opioid misuse across the lifespan

Prevalence

For any past-year prescription opioid use, rates increase with aging per retail prescription data and nationally representative US data across adults 18 and older,70,71,162 peaking at roughly 40% in those 50 and older.45 Conversely, past-year and past-month prevalence rates of opioid PDM increase through adolescence (12-17 years, unless otherwise noted) into young adulthood (18-25 years, unless otherwise noted) and decline with aging, per nationally representative data from the NSDUH.37,55,70 Work examining local college undergraduate samples72 and birth cohorts of adolescents and young adults via nationally representative US data21,73 indicates a consistent pattern in both past-year opioid PDM and prescription opioid use disorder (P-OUD): peak opioid PDM occurs between 18 to 21 years, plateaus and declines in the early 30s;72-74 for P-OUD, increases occur from young adulthood steadily into the early 30s.73 Data from a large school-based sample of adolescents in southeastern Michigan suggests that incidence peaks in late adolescence,51 implying an increase in level or frequency of use to the early adult prevalence peak.

Members of the “Millennial” generation (birth years 1979-1996) had higher lifetime opioid PDM rates than members of the “Generation X” (birth years 1964-1979) or “Baby Boomer” (birth years 1949-1964) cohorts, with increasing likelihood of opioid PDM as the first substance used in “Millennials,” per nationally representative US data.75 Similar work using difference age cohorts and different nationally representative data across adults 18 to 57 years also found increased odds of opioid PDM in members of younger generations.76 Longitudinal data from US high school seniors indicated that the likelihood of persisting opioid PDM (ie, PDM at multiple longitudinal timepoints) increased in younger generations, and persisting opioid PDM was associated with problematic other substance use behaviors.77 Despite lower overall rates, both NSDUH data in adults 50 and older53 and US nationwide poison call center data78,79 suggested that opioid PDM increased in adults 50 years and older between 2002 and 2014,53,78,79 with increases in PDM among older adults for reasons related to suicidality79 and increases in serious medical outcomes related to older adult opioid PDM.78

Medication sources for prescription opioid misuse

As with opioid PDM prevalence, evidence strongly suggests that the opioid sources vary by age group. Older NSDUH data suggests that young adults are more likely than other age groups to purchase or steal opioid medication from friends and family and to purchase opioids from strangers (including dealers), while adults 50 years and older were more likely to use multiple physicians.16 Per more recent NSDUH data across the population, young adults have the highest rates of prescription opioid purchases and multiple source use, while adolescents have slightly higher rates of theft.55 Conversely, use of physician sources (ie, one’s own medication) increases with aging, with the highest rates in adults 65 years and older.55,80 Regardless, obtaining an opioid for free from friends or family was the most common source, except in those 65 and older.55

Across ages, research consistently indicates that purchases and use of multiple sources are associated with higher odds of concurrent other substance use, like binge alcohol use, marijuana use, prescription opioid use disorder or any SUD. Conversely, use of physician sources/one’s own medication or obtaining opioid medication from friends or family for free is generally associated with lower relative risk. These findings are consistent in US nationally representative data across adolescents,40,81,82 young adults36 and older adults (50 and older),55 though physician source use in older adults may not be associated with lower relative risk.55 Adolescents have relatively high rates of multiple source use, with 20.9% and 44.2% using multiple opioid sources in two recent reports across adolescents41 and in high school seniors.40 A key difference in these studies is that the report with the higher prevalence40 separated friend from family sources, allowing for a greater number of overall sources.

Recent research on young adults suggests that when the friend or family member’s source (ie, the source for the person who gives the respondent medication for free) is from a purchase or from multiple sources, odds of other substance use problems in the respondent are also elevated.83 Having a family member on long-term opioid therapy increases odds of longer post-surgical use in adolescents and young adults,163 and having a family member with any opioid prescription increases the likelihood of developing an opioid use disorder.164 Finally, Rigg and colleagues84 examined a local, southeastern Pennsylvania sample of adults 20 to 62 years and found that the pattern of sources at the initial opioid misuse episode differed from the past-year pattern in respondents, with somewhat higher rates of obtaining from a friend or family member and of purchases from a dealer at the later assessment.

Motives for prescription opioid misuse

Across the population, the most common motive for opioid PDM is pain relief. In adults 18 years and older, NSDUH data indicate that 63.4% of those engaged in past-year opioid PDM endorsed pain relief as their key motive, followed by to get high (11.6%), and to relax/relieve tension (10.9%).45,85 While any opioid PDM was associated with higher rates of other substance use and suicidal ideation, opioid PDM for pain relief was generally associated with the lowest rates of these correlates.85 Ashrafioun and colleagues86 linked opioid PDM motives to suicidality in adults 18 and older, with pain relief only and other motives each linked to higher rates of suicidal ideation and planning (versus no PDM). Combined pain relief and other motives, however, were linked to higher rates of attempts, with evidence that rates of ideation and planning were higher in the combined motive group than the pain relief only group.86

Two studies examined adolescent samples, finding lower endorsement of pain relief motives than in the general population. In a US regional adolescent sample (11-18 years of age), over 80% of those engaged in opioid PDM endorsed pain relief as a motive, though other motives could be selected as well.87 Conversely, nationally representative data from high school seniors completing the Monitoring the Future series of surveys suggests that other motives (to relax, experiment or get high; all above 50%) were more commonly endorsed than pain relief (45.5%).88 A local sample of college undergraduates was similar in that pain relief only was endorsed by less than half of participants, with particularly low rates (29.7%) in those with past-year opioid PDM.89 Opioid PDM to relieve pain markedly increases with age, peaking in those 65 years and older, per both nationally representative NSDUH data across the US population80,90 and data from Florida in adults aged 60 and older.91 In contrast, there are decreases in opioid PDM motivated to get high or experiment, which peak either in adolescence or young adulthood.80,90 Adolescent and young adult opioid PDM for non-pain relief motives is consistently associated with poorer outcomes, mirroring the general population.87-89,92 Furthermore, analyses of data from Florida found elevated prevalence rates of SUD and suicidal ideation in adults 60 and older engaged in opioid PDM for non-pain relief motives.90

Correlates and consequences of prescription opioid misuse

While opioid PDM prevalence rates, sources and motives vary significantly by age group, the correlates and consequences of such misuse are more invariant. Across age groups, prescription opioid misuse is associated with higher rates of concurrent substance use, including binge alcohol use, marijuana use, other illicit drug use, SUD symptoms from prescription opioid misuse and SUDs from any substance.16,81,93-97 Furthermore, polysubstance rates of 90% or higher appear to be common in adolescents and young adults (aged 15-21 years) engaged in opioid PDM,98 with nationally representative data across the population indicating significantly higher rates of opioid PDM with other substance use (including other polysubstance use) in adolescents and young adults, versus those 26 and older.99 Earlier initiation of opioid PDM is associated with elevated odds of later opioid use disorder100 and with opioid use disorder symptoms at the age of 35 years.21,23 Limited evidence from the NSDUH suggests that links between opioid PDM and other substance use vary by age group,101 with evidence both that past-year benzodiazepine PDM is less likely with aging among those engaged in opioid PDM but that frequency of past-year benzodiazepine PDM is somewhat higher in those 26 and older (versus young adults).102

Findings in individual age groups are consistent with the population-wide findings that link psychopathology and suicidality to opioid PDM.3,103-111 In particular, the links between major depressive disorder, depressive symptoms and/or suicidality and opioid PDM are robust and well-established in adolescents,16,41,81,112 young adults16,113-115 and older adults (50 years and older),16,94,97,116,117 with a variety of different data sources used. The psychopathology-opioid PDM link may be mediated by race/ethnicity118 or age,119 with those 65 and older having weaker psychopathology-opioid PDM associations.

The age-based relationship of sociodemographics and opioid PDM is less clear. In bivariate associations across age groups, white, non-Latino/a males consistently have higher rates of opioid PDM, with unemployed persons, and those with lower family incomes and/or lower educational attainment also often linked.3,16,35,37,45,81,120 In some cases (eg, adolescents, per Schepis and Krishnan-Sarin81) these sociodemographic differences cease to be significant once mental health and/or other substance use correlates are included in models. Mowbray and Quinn16 found limited between age group differences in opioid PDM correlates via NSDUH data across the population, with the previously mentioned sociodemographic correlates of opioid PDM still significantly associated in most age groups. Their research, however, often did not find associations in older adults. Finally, Day and Rosenthal121 found that being either divorced/separated or never married (but not widowed) was associated with higher odds of combined past-year opioid and benzodiazepine misuse in those 50 years and older.

Prescription tranquilizer/sedative and benzodiazepine misuse across the lifespan

Prevalence

Data from nationally representative US surveys and administrative prescription databases find increased prevalence of benzodiazepine or tranquilizer/sedative (a survey-specific term capturing benzodiazepine or Z-drug medication) use with increasing age, though the 50-64 and 65 and older groups are equaivalent.17,29,62,122 For PDM, nationally representative US data indicate that young adults have the highest rates of past-year (5.8%) and past-month (1.8%) misuse, and adults aged 26 to 34 years evidenced the highest rates of lifetime rates (8.1%) and the second highest rates of both past-year and past-month tranquilizer/sedative PDM (4.0% and 1.4%, respectively).17

Prevalence of tranquilizer/sedative PDM has changed differentially by age group in the past 20 years. In adults 50 and older, lifetime tranquilizer/sedative PDM increased in all older adults, those 50 to 64 years and those 65 and older, and past-year tranquilizer/sedative PDM increased for those 50 to 64 years over the 2002/03 to 2012/13 time period.53 Over the 2005/06 to 2013/14 timeframe, tranquilizer PDM decreased in adolescents, young adults, and adults 35 to 49 years by 28.5%, 17.5% and 18.5%, respectively. Tranquilizer PDM increased by 22.3% in adults 26 to 34 years of age, and it doubled in adults 50 years and older, increasing by 108.1%.123 Overall, rates of Z-drug only misuse are relatively low. Lifetime zolpidem (Ambien®) misuse was endorsed by only 1.4% of adolescents,14 with peak lifetime rates in adults aged 26 to 34 years.25 Past-year zolpidem misuse prevalence was similar in young adults and adults aged 26 to 34 years, at 1.2% and 1.3%, respectively.25

Medication sources for prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse

Adolescents are most likely to obtain prescription tranquilizer/sedative medication for free from a friend or relative, followed by purchases.40,41,82 The most common source for young adults is also from friends or relatives for free, especially among full-time college students or recent graduates; the second most common young adult source is from purchases.36 Adults 18 to 49 years were more likely than those 50 and older to obtain benzodiazepines at their most recent PDM episode from friends or family for free (55.4% versus 45.1%) or purchase them (23.1% versus 8.7%), while adults 50 and older were more likely to use physician sources (40.3% versus 14.9%).124 Physician sources for tranquilizer/sedative medication misuse increase from young adulthood (9.9%) to a peak in those 65 years and older (38.2%), while purchases decrease from young adults (25.9%) to those 65 and older (2.3%).125 Across age groups, use of multiple sources and purchases is associated with higher relative rates of problematic substance use and SUD,36,40,41,55,82,125 though even misuse of one’s own medication (ie, physician sources) is associated with elevated risk above those without PDM.70 Notably, use of physician sources may not be linked with lower relative risk in older adults.125

Motives for prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse

Motives underlying prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse often align with the medication’s FDA indication, such as to induce sleep or relieve anxiety.165 In a study on tranquilizer/sedative PDM motives in a southeastern Michigan sample aged 12 to 18 years, the most commonly endorsed reasons for misusing to help decrease anxiety, to help sleep, and to get high.126 Nationally representative data in high school seniors suggest that the most common motives were to relax (66.0%), get high (53.3%), and experiment (49.5%); misuse to sleep was not assessed.88 In undergraduate college student US samples, conflicting findings suggest that self-treatment is less common than are recreational or combined self-treatment and recreational motives,89 and conversely that self-treatment was the key set of motives.47 Data in adults 18 years and older suggests that those 50 and older were more likely than those 18 to 49 years of age to misuse benzodiazepine medication to help with sleep (41.7% and 22.4%, respectively) and less likely to do so to get high (3.0% versus 13.9%); the most common motive, to relax (47.1% overall), did not differ by age.124

Correlates and consequences of prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse

Across the population, white/non-Latino/a individuals have elevated tranquilizer/sedative or benzodiazepine misuse, with inconsistent findings for sex differences.29,165,127,128 Consistently, though, those engaged in tranquilizer/sedative or benzodiazepine PDM have higher rates of other problematic substance use and SUD, psychopathology and suicidality.17,106,107,116,124,129-131,162,165 Adolescents, those not in school, those living in socially disorganized neighborhoods, and those with delinquent behavior have higher rates of tranquilizer/sedative PDM.37,131-133 Young adults not in college also had higher rates of tranquilizer/sedative PDM.37 Research over a three-year period found that while only a small percentage (4.3%) of adults 18 and older engaged in tranquilizer/sedative misuse develop a tranquilizer/sedative-specific SUD, a much larger percentage (45%) developed an SUD from any substance.134

Only two studies have directly compared tranquilizer/sedative PDM across age groups (12 and older, both using NSDUH data), with one examining any tranquilizer/sedative misuse,17 and the other examining zolpidem misuse specifically.25 In both cases, sociodemographic correlates showed a weaker pattern of age-based association with PDM than substance use and SUD correlates.17,25 Generally speaking, substance use/SUD and psychopathology variables were more weakly associated (or not significantly associated) with tranquilizer/sedative PDM in adults 50 and older,17,25 especially in the 65 and older cohort.17

Prescription stimulant misuse across the lifespan

Prevalence

As with other medication classes, incidence of stimulant PDM peaks between 17 and 19 years of age. There is a clear female peak at 18 years and a bimodal distribution in males with peaks at 17 and 20 years, per NSDUH data in those 12 to 21 years of age.135 Other research in adolescents 10 to 18 years points toward increasing prevalence across this age window,136,137 corresponding with increases in receipt of diverted stimulant medication.138 Young adults have the highest stimulant PDM point prevalence rates,36,37,52 with evidence that current full-time college students and recent college graduates have the highest rates within young adults.35,37 Limited evidence suggests increased lifetime stimulant PDM in adults 50 to 64 years of age and 65 years and older between 2002/03 and 2012/13, but prevalence rates are both much lower than younger groups and quite low overall.53 Notably, while the pattern of stimulant PDM prevalence mirrors other medication classes, nationally representative US data and multi-national administrative pharmacy data indicate that stimulant use patterns differ, with increases through childhood and adolescence to a peak in young adulthood, followed by declines.18,139

Medication sources for prescription stimulant misuse

Data from across US adults 18 and older indicates that obtaining stimulants for PDM from friends or family for free was the most common recent source, at 56.9%; 21.8% purchased or stole the stimulant from a friend or relative, while 11.1% used physician sources.140 Older nationally representative data in adolescents indicated that use of friends or family to obtain stimulant medication for free was somewhat less common (47.2%) and purchases were somewhat more common (29.7%) than in adults.82 More recent nationally representative adolescent data indicated that 18.1% of adolescents used multiple sources.136 The greatest difference between the older (which did not include multiple sources) and newer data was in use of friends or family to obtain stimulant medication for free (29.0% versus 47.2%),41 suggesting that adolescents obtaining stimulant medication from friends or family for free may have high rates of multiple source use.