Abstract

Opisthopappus Shih is an endemic and endangered genus restricted to the Taihang Mountains that has important ornamental and economic value. According to the Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae (FRPS, Chinese version), this genus contains two species (Opisthopappus longilobus and Opisthopappus taihangensis), whereas in the Flora of China (English version) only one species O. taihangensis is present. The interspecific phylogenetic relationship remains unclear and undefined, which might primarily be due to the lack of specific molecular markers for phylogenetic analysis. For this study, 2644 expressed sequence tag-simple sequence repeats (EST-SSRs) from 33,974 unigenes using a de novo transcript assembly of Opisthopappus were identified with a distribution frequency of 7.78% total unigenes. Thereinto, mononucleotides (1200, 45.39%) were the dominant repeat motif, followed by trinucleotides (992, 37.52%), and dinucleotides (410, 15.51%). The most dominant trinucleotide repeat motif was ACC/GGT (207, 20.87%). Based on the identified EST-SSRs, 245 among 1444 designed EST-SSR primers were selected for the development of potential molecular markers. Among these markers, 63 pairs of primers (25.71%) generated clear and reproducible bands with expected sizes. Eventually, 11 primer pairs successfully amplified all individuals from the studied populations. Through the EST-SSR markers, a high level of genetic diversity was detected between Opisthopappus populations. A significant genetic differentiation between the O. longilobus and O. taihangensis populations was found. All studied populations were divided into two clusters by UPGMA, NJ, STRUCTURE, and PCoA. These results fully supported the view of the FRPS, namely, that O. longilobus and O. taihangensis should be regarded as two distinct species. Our study demonstrated that transcriptome sequences, as a valuable tool for the quick and cost-effective development of molecular markers, was helpful toward obtaining comprehensive EST-SSR markers that could contribute to an in-depth assessment of the genetic and phylogenetic relationships between Opisthopappus species.

Keywords: Opisthopappus, transcriptome sequencing, EST-SSRs development, population genetics, phylogenetic relationship

Introduction

Opisthopappus Shih is a perennial herbaceous genus of the Asteraceae family, which is endemic to and endangered within China, that grows primarily in the cliff cracks and rock gaps of the Taihang Mountains (Shih, 1979; Ding and Wang, 1997; Wu et al., 1999; Hu et al., 2008). This genus exhibits excellent drought tolerance and leanness resistance that make it an important wild Chrysanthemum resource (Chai et al., 2018). Being a diploid, Opisthopappus is a 2A asymmetrical karyotype that has an intimate relationship with the Artemiisinae subtribe (Zhao et al., 2009). AFLP analysis has revealed that Opisthopappus is clustered with a majority of Ajania taxa, located on the basal branch of Dendranthema and Ajania. This indicates that Opisthopappus might have been a more primitive group during the eastward spread and evolutionary process of Dendranthema ancestor groups (Zhao et al., 2010).

According to the Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae (FRPS)1 (Shih and Fu, 1983), Opisthopappus contains two species, Opisthopappus longilobus Shih and Opisthopappus taihangensis (Ling) Shih. The morphological differentiation between these two species presents mainly on the leaves and bracts. For O. longilobus, which has hairless leaves, there is one pinnatisect, except the basal stem leaves, and a pair of bracteal leaves beneath the involucres. For O. taihangensis, there is appressed puberulent on both surfaces of the leaves, two pinnatisect stem leaves, and no bracteal leaves. Nevertheless, according to the Flora of China2 (Wu et al., 2013), O. taihangensis was the only one species in the genus of Opisthopappus and O. longilobus was merged into it. Its basal leaves are one- or two-pinnatisect, both surfaces sparsely pubescent or glabrous, and the stem leaves are similar to the basal leaves, uppermost leaves pinnatifid.

Based on the observation on the pollen morphology of Opisthopappus, the results showed the pollen of O. longilobus at spine length and density, ostiole, density, colpus depth is more highly evolved than that of O. taihangensis (Gao et al., 2011). The micromorphological characteristics of leaves revealed that these two species differed in their characteristics and density of glandular hairs, size and density of stomata, anticlinal wall patterns, wax characteristics, as well as the size and density of salt vesicles (Jia and Wang, 2015). A comparison between the biological characteristics of O. longilobus and O. taihangensis in their natural habitats and artificial populations indicated stable inheritable characters and significant differences in their leaf morphologies and other features (Hu et al., 2008). And above all, the evolutionary relationships and taxonomic status of the species within Opisthopappus remain debated and inconclusive. Further investigations and analysis are required to definitively determine whether O. longilobus and O. taihangensis should be regarded as two distinct species or a single species.

Our previous research endeavored to explore the relationships between Opisthopappus species through various molecular markers, such as Inter-Simple Sequence Repeat (ISSR), Sequence Related Amplified Polymorphism (SRAP), Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS), and chloroplast gene sequences (Wang, 2013; Wang and Yan, 2013, 2014; Wang et al., 2015). However, cluster analysis revealed that neither O. longilobus nor O. taihangensis formed a monophyletic clade (Wang, 2013; Wang and Yan, 2013), particularly, some populations of O. longilobus always gathered with O. taihangensis populations. These cluster analysis results indicated that the two species would seemingly be merged into one species, or the limited gene data offered from the above molecular markers might not be sufficient for phylogeny analysis. Zhang et al. (2019) also pointed that the phylogenetic relationships and genetic components between species were unclear due to the limited detection capacity of specific or unique nuclear gene sequences. Therefore, the development of transferable and orthologous molecular markers between phylogenetically related species of Opisthopappus is essential and critical.

Recently, RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has been employed in the development of a high-throughput sequencing technology that has the ability to profile the entire transcriptome of any organism, particularly for non-model plants that lack sequenced genomic data (Gross et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014; Du et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2019). Meanwhile, transcriptome sequencing holds great potential as a platform for the generation of molecular markers (Martin et al., 2013). Further, de novo RNA-Seq assembly can provide a cost-effective approach to identify molecular markers, such as microsatellite markers (SSRs) and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (Davey et al., 2011; Karan et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2019). What is more, both of SSRs and SNPs markers are codominant and the reflection of specific segment or sequence information, which are recommended by UPOV-BMT molecular testing guidelines as optimal molecular markers for authenticity identification of varieties and database construction (UPOV-BMT, International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants-Molecular Biology Technology Working Group 20073). Based on the predicted SNPs, we have successfully developed eight SNP markers for population genetic analysis in Opisthopappus (Chai et al., 2018). However, with the help of the new technology and effective method, more information and further evidences are needed for more comprehensively and accurately solving the problem on the taxonomy of Opisthopappus.

Simple sequence repeats derived from ESTs (EST-SSRs) identified from transcribed RNA sequences typically contain mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, or hexa-nucleotide units, and possess abundant information, codominance, and loci specificity (Song et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2016). With codominant features between distantly related species, EST-SSRs cross-transferability can shed new light on the evolution of plant genomes, changes in gene location, and genome organization (Bazzo et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). Moreover, this transferability provides a cost-effective source of markers for related species, which is important for taxa with low microsatellite frequencies, or for those whose microsatellites are difficult to isolate (Bazzo et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). Previous transcriptome sequences in Opisthopappus, which generated and identified 33,974 unigenes and more than 3410 differentially expressed transcripts (DETs), provided crucial genetic resources and sequence data toward the development of EST-SSR markers (Chai et al., 2018).

Therefore, in this study, we developed EST-SSR markers from the Opisthopappus transcriptome and characterized their frequency, distribution, and function, which were further employed to elucidate the genetic differentiation and phylogenetic relationships between O. longilobus and O. taihangensis.

Materials and Methods

Development of EST-SSR Markers From Opisthopappus Transcriptome

The cDNA libraries were constructed using Opisthopappus tissue samples, and sequenced based on next-generation sequencing (NGS) (Chai et al., 2018). The obtained raw reads were preprocessed to filter adaptor sequences, low-quality sequences, and reads with qualities of less than Q30 using the FASTX toolkit (Gordon and Hannon, 2010). Following the removal of raw reads, high-quality clean reads were assembled de novo into contigs and unigenes using a short read assembling program called Trinity RNA-Seq Assembler (Haas et al., 2013). The assembled unigene sequences were directly identified by using MicroSatellite (MISA) identification tools (Thiel et al., 2003), for which the parameters were set at mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexa-nucleotide motifs as a minimum repeat number of 12, 6, 5, 5, 4 and 4, respectively. Based on the MISA results, the EST-SSR primers were designed using Primer3 software (Untergasser et al., 2012).

Plant Materials for Genetic Analysis

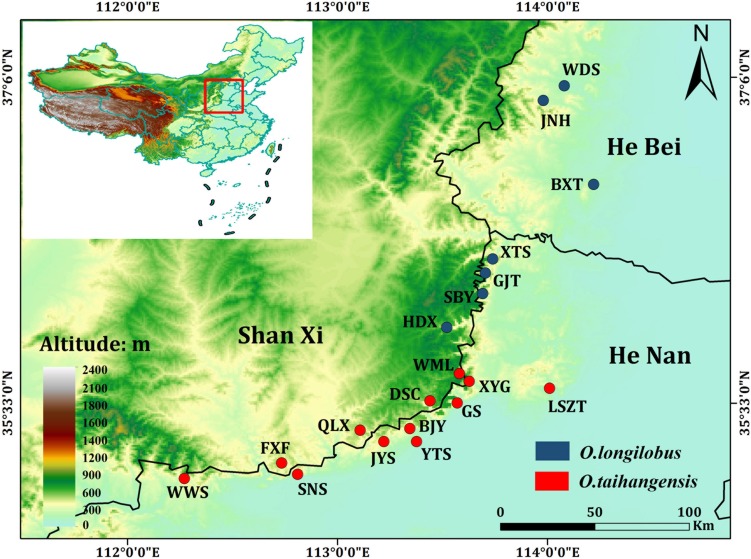

Nineteen populations of Opisthopappus were sampled, including 12 populations of O. taihangensis and 7 populations of O. longilobus, which were collected during August and September of 2017 that essentially covered their distribution ranges (Table 1 and Figure 1). Each individual from the same population was collected from different locations at least 5 m apart. Fresh young leaves were selected in each of the sample sites, where 10–15 individuals from each population were collected, for a total of 214 samples from 19 populations. The collected samples were quickly dried with silica gel and stored at 20°C for future use. A global positioning system (GPS) was employed to demarcate each sample site and record the longitude, latitude, and altitude of each population.

TABLE 1.

Sampling location information and genetic diversity of Opisthopappus based on EST-SSR markers.

| Population | Species | Location | No. | E (°) | N (°) | Alt | Na | Ne | H | I | PPB (%) |

| HDX | O. longilobus | Hongdouxia, Shanxi | 11 | 113.52 | 35.91 | 1070 | 1.282 | 1.232 | 0.2326 | 0.248 | 63.35 |

| XTS | O. longilobus | Xiantaishan, Henan | 10 | 113.73 | 36.18 | 873 | 0.774 | 1.131 | 0.0438 | 0.139 | 34.71 |

| WDS | O. longilobus | Wudangshan, Hebei | 12 | 114.08 | 37.06 | 1160 | 0.854 | 1.234 | 0.1311 | 0.201 | 36.89 |

| JNH | O. longilobus | Jingnianghu, Hebei | 12 | 113.98 | 36.99 | 650 | 0.981 | 1.218 | 0.0645 | 0.201 | 46.84 |

| BXT | O. longilobus | Beixiangtang, Hebei | 15 | 114.22 | 36.59 | 520 | 0.350 | 1.045 | 0.0315 | 0.056 | 17.23 |

| SBY | O. longilobus | Shibanyan, Henan | 15 | 113.68 | 36.07 | 720 | 1.226 | 1.144 | 0.1049 | 0.189 | 61.17 |

| GJT | O. longilobus | Gaojiatai, Henan | 12 | 113.69 | 36.11 | 805 | 1.138 | 1.160 | 0.112 | 0.196 | 56.80 |

| Species level | 1.937 | 1.356 | 0.137 | 0.327 | 96.84 | ||||||

| SNS | O. taihangensis | Shennongshan, Henan | 14 | 112.81 | 35.21 | 1028 | 1.449 | 1.377 | 0.1466 | 0.350 | 71.60 |

| FXF | O. taihangensis | Fuxifeng, Shanxi | 14 | 112.73 | 35.26 | 1120 | 1.284 | 1.295 | 0.0806 | 0.282 | 63.35 |

| GS | O. taihangensis | Guanshan, Henan | 14 | 113.57 | 35.55 | 609 | 1.539 | 1.352 | 0.1691 | 0.333 | 75.97 |

| WWS | O. taihangensis | Wangwushan, Henan | 12 | 112.27 | 35.19 | 1521 | 1.214 | 1.306 | 0.1817 | 0.287 | 59.22 |

| WML | O. taihangensis | Wangmangling, Shanxi | 12 | 113.58 | 35.69 | 1421 | 1.092 | 1.237 | 0.1454 | 0.235 | 53.64 |

| LSZT | O. taihangensis | Linshizuting, Henan | 13 | 114.01 | 35.62 | 530 | 0.976 | 1.252 | 0.1463 | 0.229 | 46.36 |

| BJY | O. taihangensis | Baijiayan, Henan | 15 | 113.42 | 35.42 | 866 | 1.068 | 1.234 | 0.1448 | 0.234 | 52.18 |

| YTS | O. taihangensis | Yuntaishan, Henan | 15 | 113.43 | 35.42 | 1011 | 1.374 | 1.304 | 0.1845 | 0.298 | 67.96 |

| XYG | O. taihangensis | Xiyagou, Shanxi | 12 | 113.59 | 35.64 | 1268 | 1.090 | 1.198 | 0.1269 | 0.211 | 53.16 |

| QLX | O. taihangensis | Qinglongxia, Shanxi | 13 | 113.17 | 35.42 | 841 | 1.274 | 1.344 | 0.1148 | 0.309 | 60.68 |

| JYS | O. taihangensis | Jingyingsi, Henan | 10 | 113.22 | 35.39 | 1006 | 1.444 | 1.373 | 0.1292 | 0.350 | 71.36 |

| DSC | O. taihangensis | Dashuangcun, Shanxi | 11 | 113.44 | 35.56 | 868 | 1.214 | 1.323 | 0.0706 | 0.295 | 57.77 |

| Species level | 1.867 | 1.223 | 0.103 | 0.271 | 93.20 | ||||||

| Opisthopappus | 2.000 | 1.300 | 0.2028 | 0.344 | 100.00 |

No., sample number; E, longitude; N, latitude; Alt, altitude; Na, observed number of alleles; Ne, effective number of alleles; H, Nei’s genetic diversity; I, Shannon’s information index; PPB, the percentage of polymorphic loci/band.

FIGURE 1.

Geographic distribution of the 19 sampled populations of Opisthopappus in China. For population abbreviations, see Table 1 for details.

DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

The genomic DNA was extracted from leaves though modified CTAB methods (Doyle et al., 1987). The quantity and quality of the DNA samples were determined using a NanoDrop ND1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis, which were then diluted to 30 ng/μl and stored at −20°C until further use.

Two hundred twenty-five EST-SSR primer pairs were initially designed based on the potential SSR loci identified in transcriptome. Subsequently, 63 primer pairs were selected to amplify 19 random DNA samples (one for each population) for the pre-experiments (primer screening). These abided by the following principles: the primer length was controlled between 18 and 25 bp, the GC content was from 40 to 60%, and the annealing temperature was from 50 to 60°C. Hairpin structures, dimers, hat structures, and mismatches were avoided as much as possible.

The primers were synthesized by Shanghai Sangon Biological Engineering Technology (Shanghai, China). Among these 63 primer pairs, 11 primers were ultimately selected based on high transferability, polymorphism, and repeatability to generate clear and reproducible bands with expected sizes, which were used to further amplify all individuals of the Opisthopappus populations (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Genetic diversity index of the used EST-SSR markers in Opisthopappus.

| Primer | SSRs | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Tm (°C) | T | TP | PPB (%) | He | Ho | PIC |

| 1 | ACA(6) | GTTCCACCACCATTG | TGCCTAAGAGAACAGATA | 56.15 | 31 | 31 | 49.07 | 0.147 | 0.154 | 0.3667 |

| CAA(6) | AGTTTGTGAG | ATGAGAT | ||||||||

| 2 | ACA(6) | GTTCCACCACCATTG | GATGGTCAATCAAAGAGT | 56.8 | 34 | 34 | 54.95 | 0.136 | 0.143 | 0.2878 |

| CAA(6) | AGTTTGTGAG | GTGGCTA | ||||||||

| 3 | ACA(6) | GTTCCACCACCATTG | AGGAATGGGAATACAAA | 56.85 | 27 | 27 | 49.12 | 0.131 | 0.137 | 0.3372 |

| CAA(6) | AGTTTGTGAG | GACGAAAA | ||||||||

| 4 | AAAC(5) | CGGAGAAATAGTAAGTCG | GAGTAGGCATGAGTGGGT | 49.7 | 52 | 52 | 62.65 | 0.183 | 0.192 | 0.3860 |

| 5 | AAAC(5) | ACTCCTACAGTGTCGGTG | AATACTACTGCTACTGGCTCTT | 53.65 | 39 | 39 | 66.94 | 0.191 | 0.200 | 0.4411 |

| 6 | AGCA(5) | GAGTGGTGTGGTGTTTTACTGTCGT | ACGATTTGTGCTGTTCTGGGAGTGG | 57.35 | 31 | 31 | 46.01 | 0.116 | 0.122 | 0.3411 |

| 7 | GAA(6) | CAAGGTCGTCAACTCATAA | CTGCTGTGATGGGAAAGA | 51.3 | 44 | 44 | 61.96 | 0.171 | 0.180 | 0.3863 |

| 8 | GAA(6) | ATGTTCCGTTTGACGAGA | GCTACTCCTGACCGACTT | 53.85 | 47 | 47 | 48.82 | 0.138 | 0.145 | 0.3756 |

| 9 | AGCA(5) | AACAATAAGTCCGCCACA | ACTCACCCAAGAATACATCG | 53.45 | 38 | 38 | 49.31 | 0.166 | 0.174 | 0.3958 |

| 10 | AGCA(5) | ATGTGCTTTACCCTTACC | GGAGAAGAGTAAAGAGGAGGCT | 53.75 | 40 | 40 | 54.47 | 0.171 | 0.180 | 0.3817 |

| 11 | AGCA(5) | GATTTGTGCTGTTCTGGGAG | GAGGCTGGGATTTGGGTT | 55.7 | 29 | 29 | 58.26 | 0.136 | 0.143 | 0.2919 |

T, total number of amplified bands; TP, total number of polymorphic bands; PPB, percentage of polymorphism; He, expected heterozygosity; Ho, observed heterozygosity; PIC, polymorphic information content.

Each 20 μL PCR reaction contained 10 μL 2× MasterMix, 0.7 μL 10 μM forward primer, 0.7 μL 10 μM reverse primer, 3 μL DNA template (30 ng/μL), and 5.6 μL H2O. The following PCR conditions were employed: 95°C pre-denaturation for 3 min; 35 cycles of 95°C denaturation for 60 s, 50–60°C annealing for 60 s, and 72°C elongation for 5 min; and a final step at 72°C elongation for 10 min, then held at 4°C. The PCR products were detected using 12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with 400 V for 3–4 h, which were then stained and photographed.

Data Analysis

The presence or absence of each SSR fragment was coded as “1” and “0,” respectively, and only clear and reproducible bands were considered. For the neutrality test of microsatellite alleles, we used the Bayesian-based outlier analysis of the multinomial-Dirichlet model (BayeScan analysis) to assess the FST distribution among all alleles by BAYESCAN v 2.1 (Beaumont and Nichols, 1996; Hsiung et al., 2017).

Genetic diversity parameters, including the observed number of alleles (Na), effective number of alleles (Ne), Nei’s genetic diversity (H), Shannon’s information index (I), and the percentage of polymorphic bands (% PPB) were calculated using the POPGENE v 1.31 program (Yeh et al., 1999).

A principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was constructed using GENALEX v 6.5 (Peakall and Smouse, 2012) and visualized with the R package “ggplot2” (Wickham, 2015). The unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic means (UPGMA) tree and neighbor-joining (NJ) trees were constructed using MEGA v 7 (Kumar et al., 2016), through which the probabilities for each node was assessed by PUAP with 1000 replicates bootstrap (Swofford, 2000). The analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was employed to investigate the total genetic variation between and within species, and among and within populations using GENALEX v 6.5 (Peakall and Smouse, 2012).

Bayesian clustering analysis (BCA) was utilized to examine the similarity and divergence of genetic components between populations, and was performed using STRUCTURE 2.3.4 (Hubisz et al., 2009). The analysis was run for K-values ranging from 1 to 19 possible clusters with 15 independent runs each and a burn-in of 10,00,000 iterations and 20,00,000 subsequent MCMC steps to evaluate consistency. The combination of an admixture and a correlated-allele frequencies model was used. The posterior probability number of grouping was evaluated using △K by STRUCTURE HARVESTER 0.6.94 (Earl, 2012). These runs were aligned and summarized using CLUMPP 1.1.2 (Jakobsson and Rosenberg, 2007), and the visualization of the results was plotted using DISTRUCT 1.1 (Rosenberg, 2004).

Pearson correlation analysis was used to test the correlations between the genetic parameters and geographic factors (longitude, latitude, altitude). Correlations between pairwise genetic distance and adjusted pairwise geographic distances were calculated with GENALEX v 6.5 (Peakall and Smouse, 2012) using the mantel test with 9999 permutations. The generalize linear regression model (GLRM) was conducted between the two distances (Nelder and Wedderburn, 1972).

Results

Characterization and Distribution of EST-SSR Markers

Through the removal of adaptors, approximately 34.9 million clean reads were obtained. The average Q30 was >95%, which reflected the high quality of the sequencing data, whereas the percentage of unknown nucleotides was only ∼0.01%. The obtained unigenes were 33,974 having paired-end reads with average lengths of 801 bp. Among these unigenes, the lengths of 14,810 unigenes (43.59%) ranged from 200 to 500 bp, and 1893 (5.57%) unigenes were longer than 2 kb. Of the 33,974 unigenes, all were successfully annotated in the NR and GO databases. About 990 of the unigenes (2.91%) were simultaneously annotated in all of the databases (NR, NCBI non-redundant protein sequences; Go, Gene Ontology; KEEG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome; eggNOG, evolutionary genealogy of genes: non-supervised Orthologous Groups; Swiss-Prot) (Supplementary Table S1).

A total of 2644 putative EST-SSRs were identified from 33,974 unigenes (Supplementary Table S2). Among these potential SSRs, five types of motifs were identified: 1200 (45.39%) mono-nucleotide, 410 (15.51%) di-nucleotide, 992 (37.52%) tri-nucleotide, 39 (1.48%) tetra-nucleotide, and 3 (0.11%) penta-nucleotide (Supplementary Table S2).

The repeat numbers for di-nucleotides, tri-nucleotides, tetra-nucleotides varied from 6 to 11, from 5 to 11, and from 6 to 8, respectively. The repeat number for penta-nucleotides was only 6 (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S2). On average, the unigenes contained one SSR per 10.30 kb and a total of 620 (23.45%) SSRs were repeated more than five times, whereas 277 (10.48%) SSRs were repeated more than 15 times. Among the SSRs identified, the AC/GT (268, 10.14%), AG/CT (94, 3.56%), AT/AT (44, 1.67%), ACC/GGT (207, 7.83%), ATC/ATG (185, 7.00%), AAG/CTT (121, 4.58%), AAC/GTT (111, 4.20%), and AGC/CTG (102, 3.86%) motifs were more prevalent than the other motifs.

TABLE 3.

Summary of the different repeat units of identified EST-SSRs.

| Number of repeat unit | Mono- | Di- | Tri- | Tetra- | Penta- | Total | Percentage (%) |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 620 | 0 | 0 | 620 | 23.45 |

| 6 | 0 | 201 | 250 | 32 | 3 | 486 | 18.38 |

| 7 | 0 | 86 | 106 | 6 | 0 | 198 | 7.49 |

| 8 | 0 | 47 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 2.31 |

| 9 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 31 | 1.17 |

| 10 | 415 | 32 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 448 | 16.94 |

| 11 | 250 | 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 265 | 10.02 |

| 12 | 112 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112 | 4.24 |

| 13 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 76 | 2.87 |

| 14 | 70 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 2.65 |

| ≥15 | 277 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 277 | 10.48 |

| Total | 1200 | 410 | 992 | 39 | 3 | 2644 | 100 |

Genetic Analysis of Opisthopappus Species

There were total 420 alleles generated by 11 EST-SSR primers across 214 samples. Eight alleles were removed with the neutrality tests by BAYESCAN 2 and the remaining 412 alleles used for further genetic population assessment and divergence tests (Supplementary Figure S1).

The percentage of polymorphisms (PPB), expected heterozygosity (He), and observed heterozygosity (Ho) ranged from 46.01 to 66.94, 0.116 to 0.191, and 0.122 to 0.200%, respectively. The pair primer 5 performed the highest PPB (66.94%) and PIC (0.4411) value (Table 2).

For the genus Opisthopappus, the PPB was 100%. Among all populations, the observed allele number (Na) ranged from 0.35 to 1.539, with an average of 1.13805. The expected allele number (Ne) ranged from 1.045 to 1.377, with an average of 1.2505. Nei’s genetic diversity (H) ranged from 0.0315 to 0.2326, with an average of 0.128185. Shannon diversity index (I) was from 0.056 to 0.35, with an average of 0.24435.

In general, O. longilobus had a relatively higher level of genetic diversity (Na = 1.937, Ne = 1.356, H = 0.137, I = 0.327, PPB = 96.84%) than O. taihangensis (Na = 1.867, Ne = 1.223, H = 0.103, I = 0.271, PPB = 93.20%). By comparing means, the results showed that the average value of diversity parameters was significantly different between O. longilobus and O. taihangensis, except for the Nei’s genetic diversity index (H) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3).

Analysis of molecular variance (Table 4) was employed to evaluate variance components between and within different populations and species. The results revealed that 67% of the total variation occurred within Opisthopappus populations, whereas 33% of the total variation existed between the genus populations. For each species, variations also significantly occurred within populations of both O. longilobus (62%) and O. taihangensis (74%). This was consistent with the hierarchical AMOVA results, which revealed that most of the genetic variation resided within populations (65%) rather than among groups (7%).

TABLE 4.

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) based on pairwise differences for Opisthopappus.

| Source | df | SS | MS | Estimated variance | Variance percentage (%) | ||

| O. longilobus | Among Pops | 6 | 1642.795 | 273.799 | 20.035 | 38 | FST = 0.380 |

| Within Pops | 78 | 2548.381 | 32.672 | 32.672 | 62 | P = 0.001 | |

| Total | 84 | 4191.176 | 52.707 | 100 | |||

| O. taihangensis | Among Pops | 11 | 2614.417 | 237.674 | 17.589 | 26 | FST = 0.261 |

| Within Pops | 117 | 5821.738 | 49.758 | 49.758 | 74 | P = 0.001 | |

| Total | 128 | 8436.155 | 67.348 | 100 | |||

| Opisthopappus | Among Pops | 18 | 5023.073 | 279.06 | 21.042 | 33 | FST = 0.329 |

| Within Pops | 195 | 8370.119 | 42.924 | 42.924 | 67 | P = 0.001 | |

| Total | 213 | 13,393.192 | 63.966 | 100 | |||

| Hierarchical AMOVA | Among Groups | 1 | 765.86 | 765.86 | 4.829 | 7 | FCT = 0.073 |

| based on two groups | Among Pops | 17 | 4257.213 | 250.424 | 18.592 | 28 | FSC = 0.302 |

| Within Pops | 195 | 8370.119 | 42.924 | 42.924 | 65 | FST = 0.353 | |

| (O. longilobus and O. taihangensis) | Total | 213 | 13,393.192 | 66.345 | 100 | P = 0.001 |

FCT, genetic differentiation among groups; FSC, genetic differentiation among populations within groups; FST, genetic differentiation among populations.

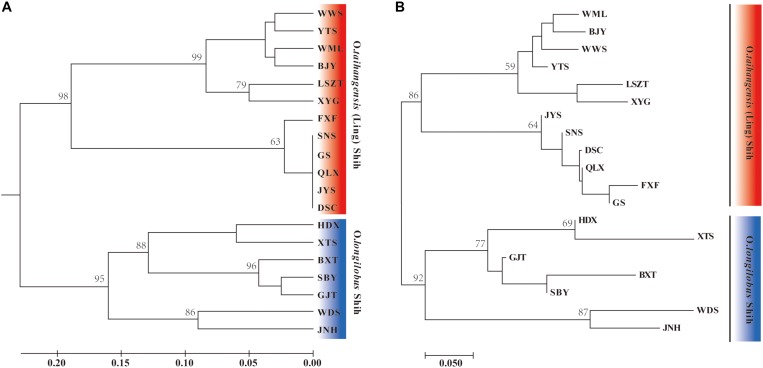

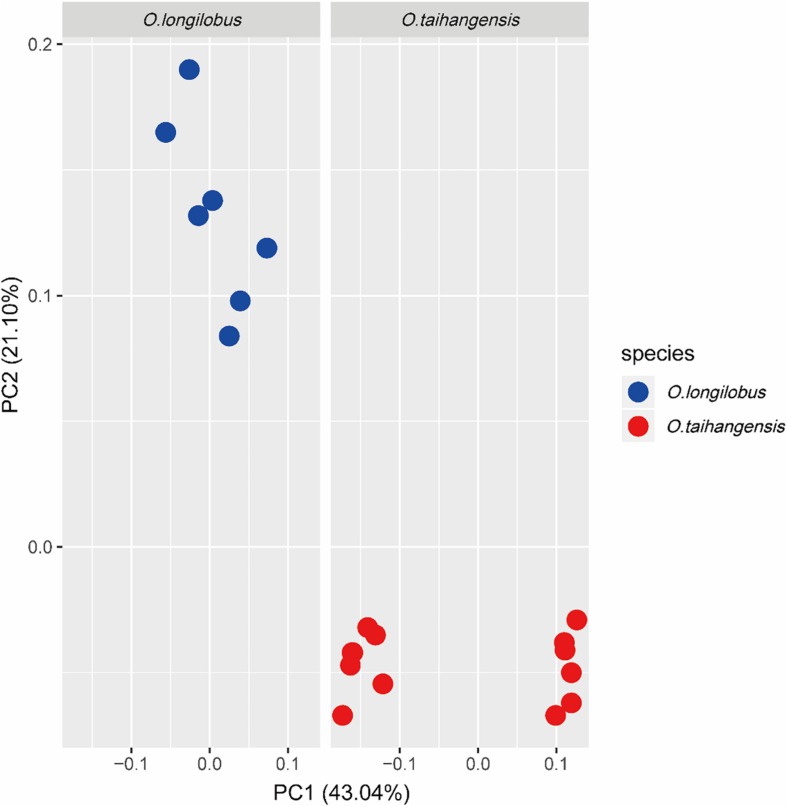

Clustering analysis well distinguished all populations into two major clusters in both UPGAM and NJ tree (Figure 2): O. taihangensis cluster and O. longilobus cluster. The results we observed from the PCoA were in agreement with the clustering analysis (Figure 3). The first two principal coordinates detected 64.14% of the total variation. The first coordinate axis explained 43.04% of the total genetic components, whereas the second coordinate axis explained 21.10% of the genetic components. A moderate but clear separation between the populations of different species was observed (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Dendrogram of Opisthopappus populations, generated using UPGMA (A) and NJ (B) cluster analysis. Bootstrap analysis was applied using 1000 replicates and only bootstrap values (%) >50 were given. Nineteen populations were clustered into two groups corresponding to O. longilobus and O. taihangensis in both UPGMA and NJ trees.

FIGURE 3.

The principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) for Opisthopappus. PC1 explained 43.04% variations of genetic components and PC2 explained 21.10% variations of genetic components. The O. longilobus and the O. taihangensis could be divided into two different groups corresponding to their distribution on axis1 and axis2.

The genetic structures of 19 populations of Opisthopappus were analyzed using STRUCTURE software. Based on maximum-likelihood and K (ΔK)-values, the optimal number of groups was two (K = 2). As shown in Figure 4, the O. longilobus species could be separated from the O. taihangensis species, although some individuals were mixed between populations. When K = 3 (the second-best ΔK-value), 7 populations of O. longilobus still gathered into one group, while 12 populations of O. taihangensis were divided into two subgroups. Specifically, the WWS, YTS, WML, BJY, LSZT, and XYG populations were gathered together, whereas the other 6 populations FXF, SNS, GS, QLX, JYS, and DSC were clustered into another subgroup (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Results of the Bayesian clustering analysis conducted using STRUCTURE. (A) The ΔK plot shows that K = 2 got the highest ΔK-value and K = 3 got the second-best ΔK-value, meaning that the most probable grouping number could be two or three. (B) Estimated genetic structure for K = 2 obtained for Opisthopappus. (C) Estimated genetic structure for K = 3 for Opisthopappus.

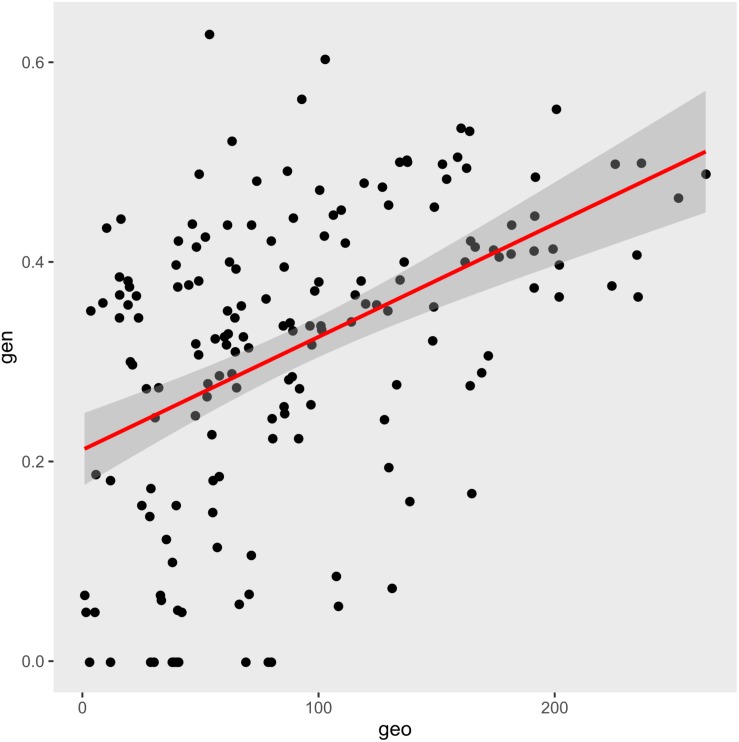

The Mantel test was employed to investigate the correlations between genetic distances and geographic distances (Figure 5). Positive correlations between the genetic and geographic distances were clearly found in the GLRM (r = 0.4565, P = 0.001; y = 0.0011x + 0.2117, R2 = 0.2082) (Figure 5), which indicated that the genetic differentiation of the populations was linearly correlated with geographic distances.

FIGURE 5.

Geographic distance was positively correlated with genetic distance. The generalized linear regression model (GLRM): y = 0.0011x + 0.2117, R2 = 0.2082. Mantel test: r = 0.4565, P = 0.001.

Discussion

The Development of EST-SSRs Markers Based on Opisthopappus Transcriptome Database

Due to the lack of sufficient genetic information and effective molecular marker systems, the phylogenetic relationship between Opisthopappus (Asteraceae) species remains unclear and unresolved to a certain extent. SSR markers are considered to be one of the most important marker systems for plant genetic studies, with high polymorphisms, high abundance, co-dominance, and genome-wide distribution (Thakur and Randhawa, 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). Compared with the genomic SSRs, EST-SSRs are effective and useful markers for non-model plants, which are easily transferred between related species owing to these regions being more evolutionarily conserved than non-coding sequences (Varshney et al., 2005; Ellis and Burke, 2007; Tahan et al., 2009; Bazzo et al., 2018; Park et al., 2019).

The application of EST-SSR markers for genetic diversity, phylogenetic analyses, the construction of genetic maps, and the marker-assisted selection of important traits has recently been reported for several plant species (Dutta et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014; Jo et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016; Vatanparast et al., 2016; Taheri et al., 2019). At present, the transcriptome sequencing technology (RNA-Seq) is a rapid, reliable, and cost-effective tool for the characterization of gene content, and the identification of polymorphic markers in non-model plants (Taheri et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). An increasing number of successful examples have supported the strategy of using transcriptome data to predict SSR molecular markers (Zalapa et al., 2012; Han et al., 2018; Taheri et al., 2019).

For our work, among 33,974 assembled unigene sequences, 2644 potential EST-SSRs were identified, which represented ∼7.78% of the transcriptomic sequences (Supplementary Table S2), and the distribution density was one SSR per 10.30 kb. The SSRs frequency and distribution density were higher than some species, such as Argyranthemum broussonetii (2.3%, 27 kb) (White et al., 2016) and Zingiber officinale (2.7%, 25.2 kb) (Awasthi et al., 2017), and lower than Arachis hypogaea (17.7%, 3.3 kb) (Wang et al., 2018), Curcuma longa (14.6%, 5.3 kb; 14.9%, 5.2 kb; 20.5%, 4.8 kb) (Annadurai et al., 2013), and Curcuma alismatifolia (12.5%, 6.6 kb) (Taheri et al., 2019). Differences in the frequency of SSRs in ESTs could be partially attributed to the different genetic basis of various plant species, the size of the unigene assembly dataset, SSR search criteria, sequence redundancy, as well as the mining tools utilized (Kumpatla and Mukhopadhyay, 2005; Chen et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2018; Taheri et al., 2019).

Based on the number of bases, five different repeat motifs from mono- to penta-nucleotide were identified, in which the most abundant SSR motifs were mononucleotide repeats (45.39%), followed by trinucleotide repeats (37.52%), and dinucleotide repeats (15.51%). In contrast, hexa (1.48%) and penta (0.11%) were rare (Supplementary Table S2). This result was similar to previous findings of di- and tri-nucleotide motifs, which were reported as the more frequent SSR motif types within the transcriptome sequences of many other plants (Zheng et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014; Awasthi et al., 2017; Park et al., 2019; Taheri et al., 2019). In many organisms, the extensive distribution of trinucleotide repeats in coding sequences is an indicator of the effects of selection and evolution. Because open-reading frames do not disturb insertions and deletions within translated regions, this signifies that these SSRs do not change the coding frame of the gene regions (Feng et al., 2012; Bazzo et al., 2018). When there were variations in SSR lengths of other repetitions, they would lead to frame shifts and induce negative mutations, which might restrict the development of other motif types (Barrero et al., 2011; Park et al., 2019; Taheri et al., 2019).

Among the mononucleotide repeats, A/T repeats (95.08%) were far more prevalent than G/C repeats (4.92%), which was consistent with most plants (Gao et al., 2013; Yue et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2017; Taheri et al., 2019). The most abundant dinucleotide repeat was the AC/GT motif (65.37%), followed by AG/CT (22.93%) and AT/TA (10.73%), which was similar to previous findings in other Chrysanthemum species Chrysanthemum indicum (Han et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the most frequent repeats of this kind of motif might vary between different species, such as in Zanthoxylum bungeanum and Oryza sativa (Asp et al., 2007; Feng et al., 2017). For trinucleotide repeat motifs, the most abundant motif was ACC/GGT (22.50%), followed by ATC/ATG (20.11%), AAG/CTT (13.15%), AAC/GTT (12.07%), and AGC/CTG (11.09%), similar to reports on C. indicum (Han et al., 2018).

Abundant trinucleotide repeats generally encoded for threonine, isoleucine, lysine, asparagine, and serine, respectively, and except for isoleucine, these were primarily small hydrophilic amino acids. It is possible that the codon repeats corresponding to hydrophilic amino acids more easily tolerated selection pressures, which might eliminate codon repeats that encoded hydrophobic and basic amino acids (Katti et al., 2001; Han et al., 2018; Taheri et al., 2019). Consequently, the high occurrence level of these motifs was significant, as amino acids generated by them were observed in proteins to a high degree (Bazzo et al., 2018; Taheri et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). The Opisthopappus species typically grows within the cliff cracks and rock gaps of the Taihang Mountains, have good drought tolerance, and are leanness-resistant (Hu et al., 2008; Chai et al., 2018). Abundant repetitions of the acids from the trinucleotide motif might explain these characteristics.

The 63 designed EST-SSR primers were obtained and verified, which offered an informative and applicable approach for the evaluation of genetic relationships between Opisthopappus species. Of the 63 primer pairs, 11 (17.5%) of the pair primers produced clear bands. This rate was relatively lower than that of previously reported species (Feng et al., 2017; Bazzo et al., 2018; Taheri et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Since there were no specificity or assembly errors following careful checking, the other 52 pair primers failed to generate the expected amplification size or non-amplification PCR products, which may have been due to the presence of introns and indels.

Meanwhile, the EST-SSR markers developed from Opisthopappus transcriptome data exhibited good transferability across different Opisthopappus species, indicating that these EST-SSR markers were useful tools for further genetic diversity analysis for this genus. The transferable nature of the EST-SSR markers between related species extended their usefulness in plant genetic studies (Varshney et al., 2005; Mathithumilan et al., 2013; Jia et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018; Park et al., 2019).

Genetic Differentiation and Phylogenetic Relationships Between Opisthopappus Species

Opisthopappus, which is an endemic and endangered genus that is geographically distributed in the Taihang Mountains, includes two species, according to the FRPS, while these two species are merged into a single species in the Flora of China. Therefore, the exact phylogenetic status of the Opisthopappus species remains under debate. Although the systematic classification and phylogenic research on Opisthopappus has been reported previously (Gao et al., 2011; Wang and Yan, 2013; Jia and Wang, 2015), O. longilobus populations are not well separated from O. taihangensis populations.

A number of reports have been published regarding the interspecific relationships between Opisthopappus species based on molecular markers (Wang, 2013; Wang and Yan, 2013); however, such research has been limited due to the lack of specific genomic information on Opisthopappus. Compared with other EST-SSR markers of plants (Kudapa et al., 2012; Onda et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018), the developed Opisthopappus transcriptomic SSR markers showed a high level of genetic diversity (Table 2), which indicated that the identified microsatellite loci possessed high allele numbers and heterozygosity, which provided efficient genetic markers for Opisthopappus populations.

Genetic diversity and fitness play a critical role in influencing the genetic structures of populations. High genetic diversity within populations is a successful strategy for adapting to various habitats and environmental conditions (Booy et al., 2000), which also increases the capacity of individuals plants, or populations thereof, to reach and colonize new habitats (Crawford and Whitney, 2010; Drummond and Vellend, 2012). Therefore, as one of the three forms of biodiversity, genetic diversity is recognized by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) as deserving conservation along with species and ecosystems (Reed and Frankham, 2003).

As an endangered perennial herb that is native to the Taihang Mountains, Opisthopappus genus populations are facing the prospect of completely disappearing in China. However, our results revealed that the genetic diversity of the populations evaluated with EST-SSR markers was more robust (Table 1). Moreover, O. longilobus populations exhibited a relatively higher level of genetic diversity than that of O. taihangensis populations (Table 1). O. longilobus primarily distributed along the northern regions of the Taihang Mountains, which has relatively low temperatures and high precipitation (Hu et al., 2008; Gong, 2010). In contrast, O. taihangensis is mainly distributed in the Southern Taihang Mountains (Hu et al., 2008; Gong, 2010). In comparison, the environmental conditions in which O. longilobus grown should be relatively harsher than that for O. taihangensis. Thus, the relatively inhospitable surroundings of O. longilobus might have cumulatively imbued it with high levels of genetic diversity.

In addition, based on the newly developed EST-SSR markers, it was found that there was a significant differentiation between Opisthopappus species (Figures 2–4). This differentiation might have resulted from long-term adaptions within a heterogeneous environment, as there are many gully valleys and gulches in the Taihang Mountains. Meanwhile, the complex topographies and diverse localized climates have also led to the varied surroundings of different species or populations.

The mantel test and GLRM (Figure 5) revealed a significant correlation between genetic and geographical distances; thus, geological impacts may have played a major role in driving and governing the genetic divergence of Opisthopappus. As new mountains formed, a long established population might have been broken up into spatially isolated subpopulations, which gradually accumulated genetic differences via adaptations to the local environment caused by this geographic segmentation (Meng et al., 2015). Originally, with changing monsoon patterns in East Asia during the Middle Miocene, the genus Opisthopappus have begun to differentiate into two major lineages: O. longilobus and O. taihangensis (Ye et al., 2019) and might have been homogeneously distributed across Northern China. Subsequently, with the uplift of Taihang Mountains and the glacial–interglacial cycles during Quaternary period (Gong, 2010; Zhang and Li, 2014), the population was spatially and geologically decollated into several different subpopulations situated in specific and distinct ecological niches, which initiated genetic differentiation and variation.

Furthermore, the Northern Taihang Mountains belong to a temperate continental semi-humid monsoon climate, while the Southern Taihang Mountains have a warm temperate continental monsoon climate (Wu et al., 1999; Gong, 2010). In the southern regions, the annual mean temperature is 12.7°C and the annual mean precipitation is 606.4 mm, whereas in the northern domains, the annual mean temperature is ∼10°C and the annual mean precipitation is 700 mm. Climatic and environmental diversity would result in geographical and ecological isolation between the species/populations, and promote the differentiation and speciation of O. longilobus and O. taihangensis. Therefore, with this accumulation of genetic differences, these isolated subpopulations began to evolve into genetically distinct lineages as the result of their adaptations to localized environmental conditions, to form the speciation pattern of Opisthopappus.

Clustering analysis (Figure 2) showed that all Opisthopappus populations were grouped into two major clusters, where O. longilobus populations gathered into one cluster, and O. taihangensis congregated into another (Figure 2). PCoA results also showed an obvious difference in the two groups (Figure 3), which was consistent with the clustering analysis (Figure 2). Moreover, BCA suggested that the best grouping number (K) was 2, and the second-best K was 3 based on the △K (Figure 4). All studied O. longilobus populations were gathered into one group in both K = 2 and K = 3. Nevertheless, the populations of O. taihangensis were inferred into two subgroups when K = 3. Therefore, we inferred that the O. taihangensis may retain a divergence potentiality to differentiation into distinct groups. The two inferences (K = 2 or K = 3) were similar and consistently indicated that the populations should be divided into two major groups, namely O. taihangensis and O. longilobus.

Conclusion

For the current study, we provided a number of EST-SSR markers to elucidate the genetic relationships of Opisthopappus species, based on a de novo RNA-Seq assembly. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to develop SSR markers for this endemic and endangered genus. In the light of the above and previous results, the strategy for obtaining EST-SSRs and SNPs from the transcriptome proved to be efficient. Using the designed EST-SSRs and SNPs markers, a significant genetic differentiation was revealed between O. longilobus and O. taihangensis (Chai et al., 2018).

All of the studied Opisthopappus populations were separated into two distinct groups, which corresponded to O. longilobus and O. taihangensis species. These results indicated that O. longilobus and O. taihangensis should be regarded as two independent species, which was well supported by the FRPS. The developed and identified EST-SSR markers were shown to be efficient and significantly contributed to the genetic and evolutionary study of Opisthopappus.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the NCBI and the GenBank accession numbers were SUB4002238 and PRJNA471103.

Author Contributions

MC, HY, and ZW performed the experiments. HY, ZW, JW, and YG collected and analyed the transcriptome data. WH, EZ, WR, and HZ analyed the population genetics of Opishopappus species. MC, HY, and YW wrote the manuscript. MC, HY, YZ, GS, and YW edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. This work was supported by the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (31970358), the Scientific and Technological Innovation Programs of Higher Education Institutions in Shanxi (201804019), and the National Natural Science Foundation of Modern College of Humanities and Sciences of Shanxi Normal University.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2020.00177/full#supplementary-material

References

- Annadurai R. S., Neethiraj R., Jayakumar V., Damodaran A. C., Rao S. N., Katta M. A., et al. (2013). De Novo transcriptome assembly (NGS) of Curcuma longa L. rhizome reveals novel transcripts related to anticancer and antimalarial terpenoids. PLoS One 8:e56217. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asp T., Frei U. K., Didion T., Nielsen K. K., Lübberstedt T. (2007). Frequency, type, and distribution of EST-SSRs from three genotypes of Lolium perenne, and their conservation across orthologous sequences of Festuca arundinacea, Brachypodium distachyon, and Oryza sativa. BMC Plant Biol. 7:36. 10.1186/1471-2229-7-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi P., Singh A., Sheikh G., Mahajan V., Gupta A. P., Gupta S., et al. (2017). Mining and characterization of EST-SSR markers for Zingiber officinale roscoe with transferability to other species of Zingiberaceae. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrero R. A., Chapman B., Yang Y., Moolhuijzen P., Keeble-Gagnã..Re G., Zhang N., et al. (2011). De novo assembly of Euphorbia fischeriana root transcriptome identifies prostratin pathway related genes. BMC Genomics 12:600. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzo B. R., de Carvalho L. M., Carazzolle M. F., Pereira G. A. G., Colombo C. A. (2018). Development of novel EST-SSR markers in the macaúba palm (Acrocomia aculeata) using transcriptome sequencing and cross-species transferability in Arecaceae species. BMC Plant Biol. 18:276. 10.1186/s12870-018-1509-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont M. A., Nichols R. A. (1996). Evaluating loci for use in the genetic analysis of population structure. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 263 1619–1626. 10.1098/rspb.1996.0237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Booy G., Hendriks R. J. J., Smulders M. J. M., Van Groenendael J. M., Vosman B. (2000). Genetic diversity and the survival of populations. Plant Biol. 2 379–395. [Google Scholar]

- Chai M., Wang S., He J., Chen W., Fan Z., Li J., et al. (2018). De novo assembly and transcriptome characterization of Opisthopappus (Asteraceae) for population differentiation and adaption. Front. Gent. 9:371 10.3389/fgene.2018.00371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Wang L., Wang S., Liu C., Cheng X. (2015). Transcriptome sequencing of mung bean (vigna radiate L.) genes and the identification of EST-SSR markers. PLoS One 10:e0120273. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Huang X., Yan X., Liang Y., Wang Y., Li X., et al. (2013). Transcriptome analysis in sheepgrass (Leymus chinensis): a dominant perennial grass of the eurasian steppe. PLoS One 8:e67974. 10.1371/journal.pone.0067974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford K. M., Whitney K. D. (2010). Population genetic diversity influences colonization success. Mol. Ecol. 19 1253–1263. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04550.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey J. W., Hohenlohe P. A., Etter P. D., Boone J. Q., Catchen J. M., Blaxter M. L. (2011). Genome-wide genetic marker discovery and genotyping using next-generation sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12 499–510. 10.1038/nrg3012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding B., Wang S. (1997). Flora of Henan, Zhengzhou. Beijing: Henan Science and Technology (Press). [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J. J., Doyle J. L., Doyle J. A., Doyle F. J. (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf material. Phytochem. Bull. 19 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond E. B. M., Vellend M. (2012). Genotypic diversity effects on the performance of taraxacum officinale populations increase with time and environmental favorability. PLoS One 7:e30314. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du F., Wu Y., Zhang L., Li X.-W., Zhao X.-Y., Wang W.-H., et al. (2015). De novo assembled transcriptome analysis and SSR marker development of a mixture of six tissues from Lilium oriental hybrid ‘Sorbonne’. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 33 281–293. 10.1007/s11105-014-0746-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S., Kumawat G., Singh B. P., Gupta D. K., Singh S., Dogra V., et al. (2011). Development of genic-SSR markers by deep transcriptome sequencing in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan (L.) Millspaugh). BMC Plant Biol. 11:17. 10.1186/1471-2229-11-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl D. A. (2012). STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 4 359–361. 10.1007/s12686-011-9548-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J. R., Burke J. M. (2007). EST-SSRs as a resource for population genetic analyses. Heredity 99:125. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6801001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C., Chen M., Xu C. J., Bai L., Yin X. R., Li X., et al. (2012). Transcriptomic analysis of Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra) fruit development and ripening using RNA-Seq. BMC Genomics 13:19. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., Zhao L., Liu Z., Liu Y., Yang T., Wei A. (2017). De novo transcriptome assembly of Zanthoxylum bungeanum using Illumina sequencing for evolutionary analysis and simple sequence repeat marker development. Sci. Rep. 7:16754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. H., Dai P. F., Ji Z. F., Han X., Wang Y. L. (2011). Studies on pollen morphology of Opisthopappus shih. Acta Bot. Boreali Occidentalia Sin. 31 2464–2472. [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z., Wu J., Liu Z. A., Wang L., Ren H., Shu Q. (2013). Rapid microsatellite development for tree peony and its implications. BMC Genomics 14 886–886. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong M. Q. (2010). Uplifting Process of Southern Taihang Mountain in Cenozoic. Thesis for Doctor’ Degree. Beijing: Chinese Academy of Geological Science. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A., Hannon G. J. (2010). Fastx-Toolkit. FASTQ/A Short-Reads Pre-Processing Tools. Available at: http://Hannonlab.Cshl.Edu/Fastx_Toolkit. [Google Scholar]

- Gross S. M., Martin J. A., Simpson J., Abraham-Juarez M. J., Wang Z., Visel A. (2013). De novo transcriptome assembly of drought tolerant CAM plants, Agave deserti and Agave tequilana. BMC Genomics 14:563. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas B. J., Papanicolaou A., Yassour M., Grabherr M., Blood P. D., Bowden J., et al. (2013). De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8:1494. 10.1038/nprot.2013.084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z., Ma X., Min W., Tong Z., Zhan R., Chen W. (2018). SSR marker development and intraspecific genetic divergence exploration of Chrysanthemum indicum based on transcriptome analysis. BMC Genomics 19:291. 10.1186/s12864-018-4702-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiung H. Y., Huang B. H., Chang J. T., Huang Y. M., Huang C. W., Liao P. C. (2017). Local climate heterogeneity shapes population fenetic structure of two undifferentiated insular scutellaria species. Front. Plant Sci. 8:159. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G. Y., Jian L., Jin L., Li Z. S., Xia L., Sun Q. W., et al. (2008). Preliminary study on the origin identification of natural gas by the parameters of light hydrocarbon. Sci. China 51 131–139. 10.1007/s11430-008-5017-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Yan H. D., Zhang X. Q., Zhang J., Frazier T. P., Huang D. J., et al. (2016). De novo transcriptome analysis and molecular marker development of two hemarthria species. Front. Plant Sci. 7:610. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubisz M. J., Falush D., Stephens M., Pritchard J. K. (2009). Inferring weak population structure with the assistance of sample group information. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 9 1322–1332. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02591.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson M., Rosenberg N. A. (2007). CLUMPP: a cluster matching and permutation program for dealing with label switching and multimodality in analysis of population structure. Bioinformatics 23 1801–1806. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia R. Z., Wang Y. L. (2015). Leaves micromorphological characteristics of Opisthopappus taihangensis and Opisthopappus longilobus from Taihang Mountain, China. Vegetos 28 82–89. 10.5958/2229-4473.2015.00041.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H., Yang H., Sun P., Li J., Zhang J., Guo Y., et al. (2016). De novo transcriptome assembly, development of EST-SSR markers and population genetic analyses for the desert biomass willow, Salix psammophila. Sci. Rep. 6:39591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo K. M., Jo Y., Chu H., Lian S., Cho W. K. (2015). Development of EST-derived SSR markers using next-generation sequencing to reveal the genetic diversity of 50 Chrysanthemum cultivars. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 60 37–45. 10.1016/j.bse.2015.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karan M., Evans D. S., Reilly D., Schulte K., Wright C., Innes D., et al. (2012). Rapid microsatellite marker development for African mahogany (Khaya senegalensis, Meliaceae) using next-generation sequencing and assessment of its intra-specific genetic diversity. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 12 344–353. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03080.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katti M. V., Ranjekar P. K., Gupta V. S. (2001). Differential distribution of simple sequence repeats in eukaryotic genome sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18:1161. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudapa H., Bharti A. K., Cannon S. B., Farmer A. D., Mulaosmanovic B., Kramer R., et al. (2012). A comprehensive transcriptome assembly of Pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L.) using sanger and second-generation sequencing platforms. Mol. Plant 5 1020–1028. 10.1093/mp/ssr111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpatla S. P., Mukhopadhyay S. (2005). Mining and survey of simple sequence repeats in expressed sequence tags of dicotyledonous species. Genome 48 985–998. 10.1139/g05-060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Li M., Hou L., Zhang Z., Pang X., Li Y. (2018). De novo transcriptome assembly and population genetic analyses for an endangered Chinese endemic acer miaotaiense (Aceraceae). Genes 9:378. 10.3390/genes9080378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Shao W., Shen Y., Ji M., Chen W., Ye Y., et al. (2018). Characterization of new microsatellite markers based on the transcriptome sequencing of Clematis finetiana. Hereditas 155:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L. B. B., Fei Z., Giovannoni J. J., Rose J. K. C. (2013). Catalyzing plant science research with RNA-seq. Front. Plant Sci. 4:66. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathithumilan B., Kadam N. N., Biradar J., Reddy S. H., Ankaiah M., Narayanan M. J., et al. (2013). Development and characterization of microsatellite markers for Morus spp. and assessment of their transferability to other closely related species. BMC Plant Biol. 13:194. 10.1186/1471-2229-13-194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L., Chen G., Li Z., Yang Y., Wang Z., Wang L. (2015). Refugial isolation and range expansions drive the genetic structure of Oxyria sinensis (Polygonaceae) in the Himalaya-Hengduan Mountains. Sci. Rep. 5:10396. 10.1038/srep10396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelder J. A., Wedderburn R. W. (1972). Generalized linear models. J. R. Stat. Ser. A (General) 135 370–384. [Google Scholar]

- Onda Y., Mochida K., Yoshida T., Sakurai T., Seymour R. S., Umekawa Y., et al. (2015). Transcriptome analysis of thermogenic Arum concinnatum reveals the molecular components of floral scent production. Sci. Rep. 5:8753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Son S., Shin M., Fujii N., Hoshino T., Park S. J. (2019). Transcriptome-wide mining, characterization, and development of microsatellite markers in Lychnis kiusiana (Caryophyllaceae). BMC Plant Biol. 19:14. 10.1186/s12870-018-1621-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakall R., Smouse P. E. (2012). GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research–an update. Bioinformatics 28 2537–2539. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed D. H., Frankham R. (2003). Correlation between fitness and genetic diversity. Conserv. Biol. 17 230–237. 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01236.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg N. A. (2004). DISTRUCT: a program for the graphical display of population structure. Mol. Ecol. Notes 4 137–138. 10.1046/j.1471-8286.2003.00566.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shih C. (1979). Opisthopappus shih-a new genus of compositae from China. Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 32 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- Shih C., Fu G. X. (1983). “Compositae (3) anthemideae,” in Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae, eds Lin Y., Shih C. (Beijing: Science Press; ), 144–145. [Google Scholar]

- Song S., Huang Y. Z., Dong L. M., Huang Y. J., Zeng Y. R., Wu Z. M. (2012). Simple sequence repeat(SSR) markers in Carya cathayensis. J. Zhejiang A&F Univ. 29 626–633. 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.2012.04.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford D. L. (2000). PUAP: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimong, ver. 4.0b. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tahan O., Geng Y., Zeng L., Dong S., Fei C., Jie C., et al. (2009). Assessment of genetic diversity and population structure of Chinese wild almond, Amygdalus nana, using EST- and genomic SSRs. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 37 146–153. 10.1016/j.bse.2009.02.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taheri S., Abdullah T. L., Rafii M. Y., Harikrishna J. A., Werbrouck S. P. O., Teo C. H., et al. (2019). De novo assembly of transcriptomes, mining, and development of novel EST-SSR markers in Curcuma alismatifolia (Zingiberaceae family) through Illumina sequencing. Sci. Rep. 9:3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur O., Randhawa G. S. (2018). Identification and characterization of SSR, SNP and InDel molecular markers from RNA-Seq data of guar (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba, L. Taub.) roots. BMC Genomics 19:951. 10.1186/s12864-018-5205-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel T., Michalek W., Varshney R., Graner A. (2003). Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor. Applied Genet. 106 411–422. 10.1007/s00122-002-1031-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser A., Cutcutache I., Koressaar T., Ye J., Faircloth B. C., Remm M., et al. (2012). Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:e115. 10.1093/nar/gks596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney R. K., Sigmund R., Borner A., Korzun V., Stein N., Sorrells M. E., et al. (2005). Interspecific transferability and comparative mapping of barley EST-SSR markers in wheat, rye and rice. Plant Sci. 168 195–202. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vatanparast M., Shetty P., Chopra R., Doyle J. J., Sathyanarayana N., Egan A. N. (2016). Transcriptome sequencing and marker development in winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus, Leguminosae). Sci. Rep. 6:29070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Jiang J., Chen S., Qi X., Peng H., Li P., et al. (2013). Next-generation sequencing of the Chrysanthemum nankingense (Asteraceae) transcriptome permits large-scale unigene assembly and SSR marker discovery. PLoS One 8:e62293. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Lei Y., Yan L., Wan L., Cai Y., Yang Z., et al. (2018). Development and validation of simple sequence repeat markers from Arachis hypogaea transcript sequences. Crop J. 6 172–180. 10.1016/j.cj.2017.09.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. (2013). Chloroplast microsatellite diversity of Opisthopappus Shih (Asteraceae) endemic to China. Plant Syst. Evol. 299 1849–1858. 10.1007/s00606-013-0840-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Yan G. (2013). Genetic diversity and population structure of Opisthopappus longilobus and Opisthopappus taihangensis (Asteraceae) in China determined using sequence related amplified polymorphism markers. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 49 115–124. 10.1016/j.bse.2013.03.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Yan G. (2014). Molecular phylogeography and population genetic structure of O. longilobus and O. taihangensis (Opisthopappus) on the Taihang mountains. PLoS One 9:e104773. 10.1371/journal.pone.0104773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. L., Zhang C. Q., Lin L. L., Yuan L. H. (2015). ITS sequence analysis of Opisthopappus taihangensis and Opisthopappus longilobus. Acta Hortic. Sin. 1:12. [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z., Sun Z., Cui B., Zhang Q., Xiong M., Wang X., et al. (2016). Transcriptome analysis of colored calla lily (Zantedeschia rehmannii Engl.) by Illumina sequencing: de novo assembly, annotation and EST-SSR marker development. Peerj 4:e2378. 10.7717/peerj.2378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White O. W., Bethany D., Carine M. A., Chapman M. A. (2016). Transcriptome sequencing and simple sequence repeat marker development for three Macaronesian endemic plant species. Appl. Plant Sci. 4:1600050. 10.3732/apps.1600050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H. (2015). ggplot2. Wiley Interdiscipl. Rev. Comput. Statist. 3 180–185. 10.1002/wics.147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C., Zhang X., Ma Y. (1999). The Taihang and Yan mountains rose mainly in Quaternary. North China Earthq. Sci. 17 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Luo S., Wang R., Zhong Y., Xu X., Lin Y. E., et al. (2014). The first Illumina-based de novo transcriptome sequencing and analysis of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch.) and SSR marker development. Mol. Breed. 34 1437–1447. 10.1007/s11032-014-0128-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. Y., Peter H. R., Hong D. Y. (2013). Asteraceae, Opisthopappus Shih. Flora of China. Beijing: Science Press, 20–21,6,654,758. [Google Scholar]

- Ye J. W., Zhang Z. K., Wang H. F., Bao L., Ge J. P. (2019). Phylogeography of Schisandra chinensis (Magnoliaceae) reveal multiple refugia with ample gene flow in Northeast China. Front. Plant Sci. 10:199. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh F., Yang R., Boyle T. (1999). POPGENE Version 1.32: Microsoft Windows–Based Freeware for Population Genetic Analysis, Quick User Guide. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: Center for International Forestry Research, University of Alberta. [Google Scholar]

- Yue C., Song Y., Liu Z. P., Ren W. C., Liu J., Wei M. A. (2016). Study on quality evaluation of sequence and SSR information in transcriptome of Astragalus membranacus. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 1430–1434. 10.4268/cjcmm20160810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalapa J. E., Cuevas H., Zhu H., Steffan S., Senalik D., Zeldin E., et al. (2012). Using next-generation sequencing approaches to isolate simple sequence repeat (SSR) loci in the plant science. Am. J. Bot. 99 193–208. 10.3732/ajb.1100394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Li P. (2014). Discussion on the main uplift period of the southern segment of Taihang Mountains. Territ. Nat. Resour. Study 4 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Dai S., Hong Y., Song X. (2014). Application of genomic SSR locus polymorphisms on the identification and classification of Chrysanthemum cultivars in China. PLoS One 9:e104856. 10.1371/journal.pone.0104856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Xie W., Zhang J., Zhao X., Zhao Y., Wang Y. (2018). Phenotype- and SSR-based estimates of genetic variation between and within two important elymus species in western and northern China. Genes 9:147. 10.3390/genes9030147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Xie W., Zhao Y., Zhang J., Wang N., Ntakirutimana F., et al. (2019). EST-SSR marker development based on RNA-sequencing of E. sibiricus and its application for phylogenetic relationships analysis of seventeen Elymus species. BMC Plant Biol. 19:235. 10.1186/s12870-019-1825-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H. B., Li C., Tang F. P., Chen F. D., Chen S. M. (2009). Chromosome numbers and morphology of eighteen Anthemideae (Asteraceae) taxa from China and their systematic implications. Caryologia 62 288–302. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H. B., Miao H. B., Wu G. S., Chen F. D., Guo W. M. (2010). Intergeneric phylogenetic relationship of Dendranthema (DC.) Des Moul., Ajania Poljakov and their allies based on amplified fragment length polymorphism. Sci. Agric. Sin. 43 1302–1313. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X., Pan C., Diao Y., You Y., Yang C., Hu Z. (2013). Development of microsatellite markers by transcriptome sequencing in two species of Amorphophallus (Araceae). BMC Genomics 14:490–490. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q., Luo D., Ma L., Xie W., Wang Y., Wang Y., et al. (2016). Development and cross-species transferability of EST-SSR markers in Siberian wildrye (Elymus sibiricus L.) using Illumina sequencing. Sci. Rep. 6: 20549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the NCBI and the GenBank accession numbers were SUB4002238 and PRJNA471103.