Abstract

Background

IgA nephropathy is the most common glomerulonephritis world‐wide. IgA nephropathy causes end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) in 15% to 20% of affected patients within 10 years and in 30% to 40% of patients within 20 years from the onset of disease. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2003 and updated in 2015.

Objectives

To determine the benefits and harms of immunosuppression strategies for the treatment of IgA nephropathy.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 9 September 2019 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs of treatment for IgA nephropathy in adults and children and that compared immunosuppressive agents with placebo, no treatment, or other immunosuppressive or non‐immunosuppressive agents.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed study risk of bias and extracted data. Estimates of treatment effect were summarised using random effects meta‐analysis. Treatment effects were expressed as relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for dichotomous outcomes and mean difference (MD) and 95% CI for continuous outcomes. Risks of bias were assessed using the Cochrane tool. Evidence certainty was evaluated using GRADE methodology.

Main results

Fifty‐eight studies involving 3933 randomised participants were included. Six studies involving children were eligible. Disease characteristics (kidney function and level of proteinuria) were heterogeneous across studies. Studies evaluating steroid therapy generally included patients with protein excretion of 1 g/day or more. Risk of bias within the included studies was generally high or unclear for many of the assessed methodological domains.

In patients with IgA nephropathy and proteinuria > 1 g/day, steroid therapy given for generally two to four months with a tapering course probably prevents the progression to ESKD compared to placebo or standard care (8 studies; 741 participants: RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.65; moderate certainty evidence). Steroid therapy may induce complete remission (4 studies, 305 participants: RR 1.76, 95% CI 1.03 to 3.01; low certainty evidence), prevent doubling of serum creatinine (SCr) (7 studies, 404 participants: RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.65; low certainty evidence), and may lower urinary protein excretion (10 studies, 705 participants: MD ‐0.58 g/24 h, 95% CI ‐0.84 to ‐0.33;low certainty evidence). Steroid therapy had uncertain effects on glomerular filtration rate (GFR), death, infection and malignancy. The risk of adverse events with steroid therapy was uncertain due to heterogeneity in the type of steroid treatment used and the rarity of events.

Cytotoxic agents (azathioprine (AZA) or cyclophosphamide (CPA) alone or with concomitant steroid therapy had uncertain effects on ESKD (7 studies, 463 participants: RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.20; low certainty evidence), complete remission (5 studies; 381 participants: RR 1.47, 95% CI 0.94 to 2.30; very low certainty evidence), GFR (any measure), and protein excretion. Doubling of serum creatinine was not reported.

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) had uncertain effects on the progression to ESKD, complete remission, doubling of SCr, GFR, protein excretion, infection, and malignancy. Death was not reported.

Calcineurin inhibitors compared with placebo or standard care had uncertain effects on complete remission, SCr, GFR, protein excretion, infection, and malignancy. ESKD and death were not reported.

Mizoribine administered with renin‐angiotensin system inhibitor treatment had uncertain effects on progression to ESKD, complete remission, GFR, protein excretion, infection, and malignancy. Death and SCr were not reported.

Leflunomide followed by a tapering course with oral prednisone compared to prednisone had uncertain effects on the progression to ESKD, complete remission, doubling of SCr, GFR, protein excretion, and infection. Death and malignancy were not reported.

Effects of other immunosuppressive regimens (including steroid plus non‐immunosuppressive agents or mTOR inhibitors) were inconclusive primarily due to insufficient data from the individual studies in low or very low certainty evidence. The effects of treatments on death, malignancy, reduction in GFR at least of 25% and adverse events were very uncertain. Subgroup analyses to determine the impact of specific patient characteristics such as ethnicity or disease severity on treatment effectiveness were not possible.

Authors' conclusions

In moderate certainty evidence, corticosteroid therapy probably prevents decline in GFR or doubling of SCr in adults and children with IgA nephropathy and proteinuria. Evidence for treatment effects of immunosuppressive agents on death, infection, and malignancy is generally sparse or low‐quality. Steroid therapy has uncertain adverse effects due to a paucity of studies. Available studies are few, small, have high risk of bias and generally do not systematically identify treatment‐related harms. Subgroup analyses to identify specific patient characteristics that might predict better response to therapy were not possible due to a lack of studies. There is no evidence that other immunosuppressive agents including CPA, AZA, or MMF improve clinical outcomes in IgA nephropathy.

Plain language summary

Immunosuppressive agents for treating IgA nephropathy

What is the issue? IgA nephropathy is a common kidney disease that often leads to decreased kidney function and may result ultimately in kidney failure for one‐third of affected people. The cause of IgA nephropathy is not known, although most people with the disease have abnormalities in their immune system.

What did we do? We searched for all the research trials that assessed the effect of immunosuppressive therapy in people with IgA nephropathy in September 2019. We measured the certainty we could have about the treatments using a system called "GRADE".

What did we find? We found 58 studies involving 3933 adults and children who were treated with immunosuppressive therapy. Patients in the studies were given either steroids or other forms of therapy to reduce the actions of their immune system. The treatment they got was decided by random chance. Steroid therapy taken for 2 to 4 months appeared to slow damage to the kidney and probably prevents patients from developing kidney failure. It is really uncertain whether steroids cause side effects such as serious infection. One study was stopped early because patients who received steroid therapy had more infections than those patients who were given placebo. Other medications like cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil did not clearly protect kidney function in people with IgA nephropathy.

Conclusions

Steroid therapy may prevent kidney failure in IgA nephropathy but the risks of serious infections are uncertain with treatment.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

IgA nephropathy was first described in 1968 by Dr J. Berger. Characterised by prominent mesangial IgA deposits seen diffusely on immunofluorescence microscopy, the condition was initially thought to be a rare and benign cause of recurrent haematuria (Berger 1968). It has since become apparent, however, that IgA nephropathy is neither rare nor benign. Although biopsy practices differ from region to region, thus affecting the frequency of diagnosis of IgA nephropathy, it has been demonstrated that IgA nephropathy is the most common glomerular disease world‐wide (D'Amico 1987; Han 2010) with a variable prevalence ranging from 5% to more than 40% (Schena 2009).

The natural history of IgA nephropathy is now known to be highly heterogeneous and far from benign in many patients. While up to 50% of patients experience lasting remission (Kim 2016; Nolin 1999), 40% can develop end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) within 20 years (Manno 2007), while another 30% to 40% experience decreased kidney function (Inagaki 2017; Rekola 1991). Overall, as many as 15% to 50% of those affected develop chronic kidney disease (CKD) and eventually ESKD (Rostoker 1995; Schena 2001). Studies have demonstrated that risk factors associated with disease progression include evidence of proteinuria, especially in people with proteinuria < 1 g/day (Reich 2007), hypertension (Liu 2019) or elevated serum creatinine (SCr) at the time of kidney biopsy, microhematuria at diagnosis (Gallo 1988; Manno 2007; Neelakantappa 1988), and specific histological lesions (as reported in the Oxford classification) (Cattran 2009; Haas 2017; Trimarchi 2017). These prognostic data may help stratify those patients at highest need for effective therapy.

Evidence suggests that IgA nephropathy is a consequence of abnormal glycosylation of O‐linked glycans in the hinge region of IgA1, resulting in increased circulation of galactose‐deficient IgA1 (Gd‐IgA1) (Gale 2017; Mestecky 1993). Most patients have some abnormalities of the immune system some time in their disease course, including increased circulating IgA or some other humoral or cellular abnormality. It has been shown that the IgA molecules deposited in the glomerular mesangium have the same abnormalities of glycosylation (Hiki 2001). Altered IgA glycosylation may enhance mesangial deposition due to the formation of pathogenic immune complexes or by promoting IgA molecular interactions with kidney matrix proteins and/or mesangial cell immune receptors.

Complement system activation occurs in IgA nephropathy through the alternative and lectin pathways, with complement components identified in pathogenic mesangial deposits (Maillard 2015), Evidence for complement activity in the progression of IgA nephropathy glomerular injury has led to the development of short interfering RNA molecules (siRNA) against complement component 5 (C5) which is undergoing evaluation in a phase 2 randomised controlled trial (RCT) (NCT03841448).

Description of the intervention

Despite better understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms causing IgA nephropathy, there is no established disease‐targeted treatment for IgA nephropathy and various treatments have been applied, including corticosteroid, azathioprine (AZA), calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), cyclophosphamide (CPA), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), rituximab and leflunomide (Hou 2017; Lafayette 2017; Locatelli 1999; Pozzi 2010; Song 2017).

IgA nephropathy has been identified as having an inflammatory basis leading to the biological rationale of corticosteroid therapy (Coppo 2018). Over the last decades, some studies have reported that intravenous steroid pulse therapy in combination with oral prednisolone are effective for reducing proteinuria and preventing ESKD, as well as increasing 10‐year survival (Pozzi 1999). Evidence from observational studies (Tesar 2015) and RCTs (TESTING 2017) showed potential benefits of corticosteroid treatment in patients with proteinuric IgA nephropathy, although severe infectious complications and a higher mortality risk has suggested the need to evaluate intervention strategies that have lower toxicity.

Tonsillectomy combined with steroid pulse therapy has been shown to induce had a significant impact on clinical remission of IgA proteinuria and may be beneficial for long‐term kidney survival (Hotta 2001). In Asian countries, tonsillectomy is performed in at least 50% of adults with IgA nephropathy, however genetic variation may impact on IgA susceptibility and therapeutic response to this intervention strategy (Hirano 2019). By contrast, some studies have shown no therapeutic effect of corticosteroid (Lai 1986) and tonsillectomy (Piccoli 2010) in patients with IgA nephropathy leading to therapeutic uncertainty.

The recent focus on the role of gut–kidney axis in IgA nephropathy has led to development of selective corticosteroid formulations targeting the intestinal mucosal immune system, aiming to reduce proteinuria and stabilise kidney function with fewer systemic adverse events from steroid therapy (NEFIGAN 2017).

Patients may not always respond to corticosteroid therapy leading to consideration of additive immunosuppressive therapies to obtain a synergistic effect. Although IgA nephropathy is likely an autoimmune kidney disease, there is uncertainty about whether some immunosuppressive agents such as AZA or CPA suppress disease activity, reduce proteinuria or protect kidney function particularly in the absence of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (Locatelli 1999; Walker 1990a). The supportive versus immunosuppressive therapy for the treatment of progressive IgA nephropathy (STOP‐IgAN 2008) RCT showed that combined corticosteroid and immunosuppressive therapy may be superior to supportive care alone.

CNIs possess potent immunosuppressive properties, suppressing the activation and proliferation of T cells to inhibit synthesis of interleukin (IL)‐2. This suppresses secondary synthesis of various cytokines, including IL‐4 and tumour necrosis factor‐alpha. Despite these immunomodulating effects, there are limited data for protection of kidney function and evidence of increased side effects with CNIs (Song 2017).

MMF selectively inhibits the proliferation of T and B lymphocytes, antibody production, generation of cytotoxic T cells and the recruitment of leukocytes to sites of inflammation. However, experimental evidence has not clearly shown that the anti‐inflammatory properties of MMF, by attenuating glomerular and interstitial injury, are beneficial in the treatment of progressive IgA nephropathies with an acceptable safety profile (Maes 2004).

Few RCTs have evaluated the efficacy of leflunomide in the treatment of IgA nephropathy to demonstrate reduction in proteinuria and protection of kidney function (Cheng 2015). Leflunomide, generally evaluated in China, has very limited efficacy data (Lou 2006).

There has been limited stratification by risk of ESKD or disease severity in studies evaluating IgA nephropathy management. Substantial disease heterogeneity suggests a validated tool for IgA nephropathy could support accurate prediction of disease progression and enrich trial populations with patients at highest risk of ESKD (Barbour 2019). Although clinical evidence suggests that treatment of IgA nephropathy with either single and combined treatments regimen can lead to partial or complete remission and prevent loss of kidney function, some patients still experience progressive kidney injury (Moriyama 2019). The protective role of immunosuppressive therapy has been uncertain in part due to the small sample sizes and short duration therapy and follow‐up in available studies. In addition, global heterogeneity in disease activity and susceptibility based on ethnicity may impact on interpretation of treatment efficacy in different ethnicity groups and international regions (Kiryluk 2012). As a consequence of fewer data and heterogeneous disease activity in existing studies, the longer term effects of immunosuppression have been uncertain.

How the intervention might work

IgA nephropathy often progresses very slowly, taking decades to reach the clinical outcomes usually studied in clinical studies (death and need for dialysis or kidney transplantation). It has thus been difficult to establish the most effective treatment regimen for IgA nephropathy. Reviews have examined the evidence for treatment of both adults (Nolin 1999) and children (Wyatt 2001) with IgA nephropathy to find optimal regimens. These analyses included studies of varying methodological quality, and are mostly case series and other forms of non‐randomised evaluation. These data have resulted in conflicting information regarding the optimal therapy. The most commonly used regimens include immunosuppressive agents such as glucocorticoids (steroids), cyclosporin A (CSA), or CPA. Additionally, non‐immunosuppressive medications including fish oils, anticoagulants, antihypertensive agents and surgical tonsillectomy with and without immunosuppression have been tested in a variety of studies including RCTs.

Why it is important to do this review

Given the burden of disease and the known risks of progression, as well as the lack of an accepted effective therapy, a systematic review of these treatments was necessary to aid healthcare providers in managing this condition. The present review focuses on the benefits and harms of immunosuppressive treatment for IgA nephropathy. The initial review was published in 2003 (Samuels 2003b; Samuels 2004) and was updated in 2015 (Vecchio 2015).

A separate review summarises the benefits and harms of non‐immunosuppressive treatments for IgA nephropathy (Reid 2011).

Objectives

To determine the benefits and harms of immunosuppression for the treatment of IgA nephropathy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) that compared immunosuppressive therapy (corticosteroids, cytotoxic agents, MMF, leflunomide, or other) with other immunosuppressive agents, non‐immunosuppressive treatment (including antihypertensive agents and anticoagulants), or placebo or no treatment/standard care for the treatment of IgA nephropathy were included.

Types of participants

Adult and children with biopsy‐proven IgA nephropathy.

Types of interventions

Immunosuppressive agent versus placebo, no treatment/standard care, or other non‐immunosuppressive agent (including renin‐angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors)

Head to head comparisons between immunosuppressive agents.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

ESKD requiring kidney replacement therapy (KRT) (dialysis or kidney transplantation)

Complete remission: defined by a reduction in urinary protein excretion to less than 1 g/24 hours in three consecutive daily samples or as defined by the investigators

Doubling of SCr

SCr (µmol/L)

Estimated or measured glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (either creatinine clearance (CrCl) (mL/min) or Cockcroft clearance (mL/min/1.73 m2)

Urinary protein excretion (g/24 hours)

Secondary outcomes

Death

Infection

Malignancy

Where possible, time to reach the above end‐points in each treatment arm was included in the analysis.

Adverse effects

Dropout rate due to treatment‐related adverse events

Bone density, fracture or shorter stature

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 9 September 2019 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Searches of kidney and transplant journals, and the proceedings and abstracts from major kidney and transplant conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of search strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available on the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant website.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Contacting relevant individuals/organisations seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies.

Grey literature sources (e.g. abstracts, dissertations and theses), in addition to those already included in the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies, were searched.

Data collection and analysis

The initial review was undertaken by five authors (JAS, GFMS, JCC, FPS, DAM) and was updated by 10 authors (PN, SCP, MR, VS, JCC, MV, JAS, DAM, FPS, GFMS).

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that may be relevant to the review. The titles and abstracts were screened independently by at least two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable; however, studies and reviews that may have included relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed retrieved abstracts and, where necessary the full text, of these studies to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by at least two authors using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports be grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. When relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions these data were used. Any discrepancies between published versions were to highlighted.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were assessed independently by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (seeAppendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (mortality, infection, ESKD, doubling of SCr, malignancy, reduction in GFR at least 25 or 50%, complete remission, adverse events) results were expressed as relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for individual studies. When continuous scales of measurement were used, we assessed the effects of treatment (SCr, CrCl, annual GFR loss and urinary protein excretion), using the mean difference (MD), or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales had been used. Adverse events were summarised descriptively. As measures of proteinuria and albuminuria were reported using various measures, including relative to urinary creatinine, we have harmonised all endpoints to a single measure of milligrams per day or excretion. We followed the methods reported by Lambers Heerspink 2015 to convert the albumin excretion rate per day to protein excretion rate by dividing the albumin excretion by 0.6, recognising that a total daily protein excretion of 500 mg/day is approximately equal to 300 mg/day of albumin.

Dealing with missing data

Any further information required from the original author was requested by written correspondence (e.g. emailing or writing to corresponding author) and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot. We then quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2003). A guide to the interpretation of I2 values was as follows:

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P‐value from the Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2) (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

It was planned that if sufficient RCTs were identified, an attempt would be made to assess for publication bias using a funnel plot (Egger 1997). However, insufficient data precluded subgroup analyses in this review update.

Data synthesis

Treatment effects were summarised using a random effects model. For each analysis, the fixed effects model was also evaluated to ensure robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was planned to explore how possible sources of heterogeneity (paediatric versus adult population, stage of renal biopsy, race of participants) might have influenced the treatment effects observed. However, due to the small number of studies, subgroup analyses to determine the impact of patient characteristics on treatment effectiveness were not possible.

Post hoc subgroup analysis

We performed a post hoc subgroup analysis to assess the effect of the background of treatments with and without RAS blockade and blood pressure (BP) control (ACE inhibitor and/or ARB) on risks of ESKD.

'Summary of findings' tables

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schunemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schunemann 2011b). We presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

We presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' table:

ESKD

Complete remission

≥ 50% GFR loss

Annual GFR loss (mL/min/1.73 m2)

Death (any cause)

Infection

Malignancy

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

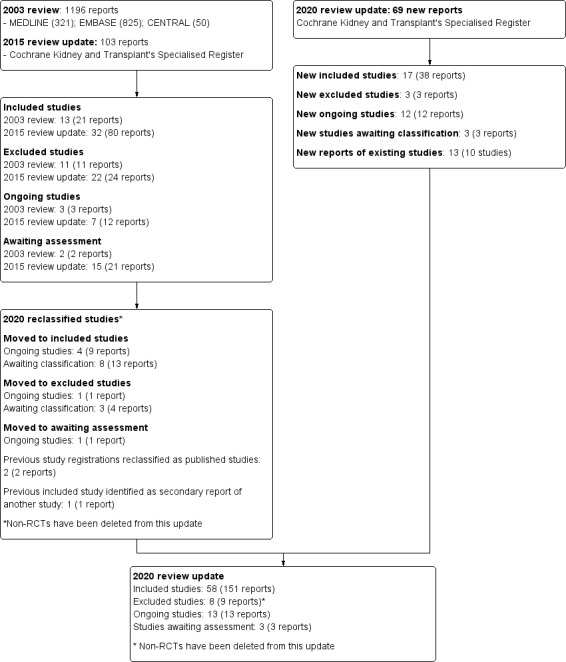

Search results are shown in Figure 1. For this 2020 review update, we identified 69 new reports. There were 36 new studies (56 reports) and 13 new reports of 10 existing studies. Seventeen new studies (38 reports) were eligible (BRIGHT‐SC 2016; CAST‐IgA 2015; Cheung 2018; Hirai 2017; Hou 2017; Koitabashi 1996; Lee 2003; Masutani 2016; Min 2017; NEFIGAN 2017; Shen 2013; Shi 2012a; Shima 2018; STOP‐IgAN 2008; TESTING 2017; Wu 2016; Yamauchi 2001) and three studies (three reports) were excluded (GloMY 2010; Imai 2006; Yonemura 2000b).

1.

Study flow diagram.

There are 13 ongoing studies (AIGA 2016; ARTEMIS‐IgAN 2018; ChiCTR1800014442; MAIN 2013; NCT00657059; NCT02808429; NCT03468972; NEFIGARD 2018; PIRAT 2015; SIGN 2014; TIGER 2017; TOPplus‐IgAN 2013; UMIN000032031) that have not yet been completed according to details held within the www.ClinicalTrials.gov registry, www.chictr.org.cn and https://upload.umin.ac.jp/; and three studies are awaiting classification while we try to determine if they meet our inclusion criteria (NCT00301600; NCT02160132; NCT02571842). These 16 studies will be assessed in a future update of this review.

In addition, four previous ongoing studies (2nd NA IgAN 2004; Hou 2017; Lafayette 2017; STOP‐IgAN 2008) and eight studies awaiting assessment (Chen 2002; Cruzado 2011; Kawamura 2014; Kim 2013b; Liu 2010a; Liu 2014; Stangou 2011; Xie 2011) have been reclassified as included. One ongoing study (Dal Canton 2005) and three studies awaiting classification have been reclassified as excluded (Chen 2009b; Czock 2007; Shen 2009).

For this 2020 update there are 58 included studies, 13 ongoing studies, 3 studies awaiting assessment and 8 excluded studies. Non‐RCTs have been removed from this update.

Included studies

The characteristics of the participants and the interventions in included studies are detailed in the Characteristics of included studies. Overall, 58 studies (151 publications) enrolling a total of 3933 patients, were included in this review update (2nd NA IgAN 2004; Ballardie 2002; BRIGHT‐SC 2016; Cao 2008; CAST‐IgA 2015; Chen 2002; Cheung 2018; Cruzado 2011; Frisch 2005; Harmankaya 2002; Hirai 2017; Horita 2007; Hou 2017; Julian 1993; Kanno 2003; Katafuchi 2003; Kawamura 2014; Kim 2013b; Kobayashi 1996; Koike 2008; Koitabashi 1996; Lafayette 2017; Lai 1986; Lai 1987; Lee 2003; Liu 2010a; Liu 2014; Locatelli 1999; Lou 2006; Lv 2009; Maes 2004; Manno 2001; Masutani 2016; Min 2017; NA IgAN 1995; NEFIGAN 2017; Ni 2005; Nuzzi 2009; Pozzi 1999; Segarra 2006; Shen 2013; Shi 2012a; Shima 2018; Shoji 2000; Stangou 2011; STOP‐IgAN 2008; Takeda 1999; Tang 2005; TESTING 2017; Walker 1990a; Welch 1992; Woo 1987; Wu 2016; Xie 2011; Yamauchi 2001; Yoshikawa 1999; Yoshikawa 2006; Zhang 2004). Ten authors were contacted for clarifications relating to their publications and to request additional unpublished information. Four authors replied to our request.

Six studies included paediatric participants (Kobayashi 1996; Nuzzi 2009; Shima 2018; Welch 1992; Yoshikawa 1999; Yoshikawa 2006). Twenty‐six studies included people with daily protein excretion > 1 g/24 hours (Cao 2008; Chen 2002; Cruzado 2011; Frisch 2005; Horita 2007; Hou 2017; Kawamura 2014; Lee 2003; Kobayashi 1996; Lai 1987; Liu 2014; Locatelli 1999; Lou 2006; Lv 2009; Maes 2004; Manno 2001; Min 2017; Ni 2005; Pozzi 1999; Segarra 2006; Shen 2013; Shi 2012a; Stangou 2011; Tang 2005; TESTING 2017; Walker 1990a). Thirteen studies (BRIGHT‐SC 2016; Chen 2002; Cheung 2018; Kawamura 2014; Koitabashi 1996; Lafayette 2017; Nuzzi 2009; Segarra 2006; Shi 2012a; Shima 2018; Takeda 1999; Welch 1992; Yamauchi 2001) did not report data in an extractable format that could be included in our meta‐analysis.

We identified five study of head‐to‐head comparisons between different immunosuppressive agents (Chen 2002; Hou 2017; Liu 2010a; Shen 2013; Wu 2016) and there were no studies that compared different doses of the same immunosuppressive agents.

Excluded studies

We excluded eight studies (nine reports) as they did not include all participants with IgA nephropathy (Imai 2006; Sulimani 2001; Yonemura 2000b), did not evaluate a immunosuppressive agent intervention (Chen 2009b; Czock 2007; Shen 2009), or did not complete the participant recruitment (Dal Canton 2005; GloMY 2010). See Characteristics of excluded studies.

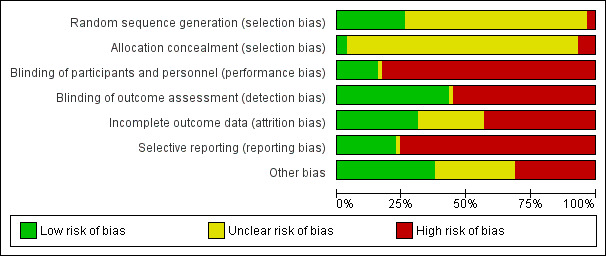

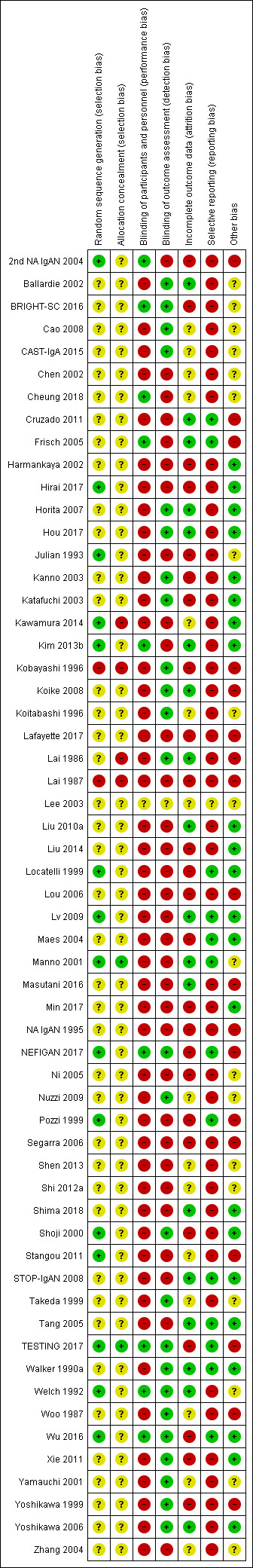

Risk of bias in included studies

The risks of bias in the included studies are summarised in Figure 2. Risks of bias in individual studies are shown in Figure 3 and described in the Characteristics of included studies.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation was considered at low risk of bias in 15 studies (2nd NA IgAN 2004; Hirai 2017; Julian 1993; Kawamura 2014; Kim 2013b; Locatelli 1999; Lv 2009; Manno 2001; NEFIGAN 2017; Pozzi 1999; Shoji 2000; Stangou 2011; TESTING 2017; Welch 1992; Wu 2016), at high risk in two studies (Kobayashi 1996; Lai 1987), and unclear in the remaining 41 studies.

Allocation concealment was adjudicated as low risk of bias in two studies (Manno 2001; TESTING 2017), at high risk in four studies (Kawamura 2014; Kobayashi 1996; Lai 1986; Lai 1987); and unclear in the remaining 52 studies.

Blinding

Nine studies (2nd NA IgAN 2004; BRIGHT‐SC 2016; Cheung 2018; Frisch 2005; Kim 2013b; NEFIGAN 2017; TESTING 2017; Welch 1992; Wu 2016) were blinded and considered to be at low risk of bias and one study (Lee 2003) was assessed as unclear risk of performance bias. The remaining 48 studies were not blinded and were considered at high risk of performance bias.

Outcome assessment was considered to be at low risk of detection bias in 25 studies (Ballardie 2002; BRIGHT‐SC 2016; Cao 2008; CAST‐IgA 2015; Horita 2007; Hou 2017; Kanno 2003; Katafuchi 2003; Kobayashi 1996; Koike 2008; Koitabashi 1996; Lai 1986; NEFIGAN 2017; Nuzzi 2009; Shoji 2000; Takeda 1999; TESTING 2017; Walker 1990a; Welch 1992; Woo 1987; Wu 2016; Xie 2011; Yamauchi 2001; Yoshikawa 1999; Yoshikawa 2006), unclear in one study (Lee 2003), and high risk the remaining 32 studies.

Incomplete outcome data

Eighteen studies were judged to be a low risk of attrition bias (Ballardie 2002; Cruzado 2011; Frisch 2005; Horita 2007; Hou 2017; Kim 2013b; Koike 2008; Lai 1986; Liu 2010a; Lv 2009; Manno 2001; Masutani 2016; Shima 2018; STOP‐IgAN 2008; Tang 2005; Walker 1990a; Welch 1992; Yoshikawa 2006), 25 studies were at high risk of attrition bias (2nd NA IgAN 2004; BRIGHT‐SC 2016; Harmankaya 2002; Hirai 2017; Julian 1993; Kanno 2003; Katafuchi 2003; Kobayashi 1996; Lafayette 2017; Lai 1987; Liu 2014; Locatelli 1999; Lou 2006; Maes 2004; Min 2017; NA IgAN 1995; NEFIGAN 2017; Ni 2005; Pozzi 1999; Segarra 2006; Shoji 2000; TESTING 2017; Wu 2016; Xie 2011; Yoshikawa 1999), and the remaining 15 studies were unclear.

Selective reporting

Thirteen studies were judged to be at low risk of reporting bias (Cruzado 2011; Frisch 2005; Locatelli 1999; Lv 2009; Maes 2004; Manno 2001; NEFIGAN 2017; Pozzi 1999; STOP‐IgAN 2008; Tang 2005; TESTING 2017; Walker 1990a; Wu 2016), one study was unclear (Lee 2003), and 44 were at high risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We adjudicated 22 studies as low risk of bias from other potential sources (Harmankaya 2002; Hirai 2017; Horita 2007; Hou 2017; Kanno 2003; Katafuchi 2003; Kawamura 2014; Kim 2013b; Liu 2010a; Liu 2014; Locatelli 1999; Lv 2009; Maes 2004; Min 2017; Shima 2018; Shoji 2000; STOP‐IgAN 2008; Tang 2005; Walker 1990a; Wu 2016; Xie 2011; Yoshikawa 2006) considering balance of participant characteristics and co‐interventions, governmental or academic sources of funding and balanced timing of outcome assessment for all treatment groups. Eighteen studies (2nd NA IgAN 2004; Cruzado 2011; Frisch 2005; Kobayashi 1996; Koike 2008; Lafayette 2017; Lai 1986; Lai 1987; Lou 2006; Masutani 2016; NA IgAN 1995; NEFIGAN 2017; Pozzi 1999; Segarra 2006; Stangou 2011; TESTING 2017; Woo 1987; Yoshikawa 1999) was assessed as high risk of bias. Risk of bias was unclear in the remaining 18 studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Systemic corticosteroid versus no corticosteroid regimen for IgA nephropathy.

| Systemic corticosteroid versus no corticosteroid regimen for IgA nephropathy | |||||

|

Patient or population: adults and children who have IgA nephropathy proven on renal biopsy Setting: Australia, China, Europe, Japan, USA Intervention: corticosteroid regimen (includes steroids alone or with RAS inhibitors) Comparison: no corticosteroid regimen | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute benefits* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with no steroids | Risk with steroids | ||||

|

End‐stage kidney disease Follow‐up: 2 to 10 years |

141 per 1000 | 55 per 1000 (32 to 92) |

RR 0.39 (0.23 to 0.65) |

741 (8) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate 1 |

|

Complete remission Follow‐up: 2 to 5 years |

364 per 1000 | 641 per 1000 (375 to 1000) | RR 1.76 (1.03 to 3.01) |

305 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1,3 |

|

GFR loss ≥ 50% Follow‐up: 2 to 2.1 years |

96 per 1000 | 54 per 1000 (24 to 119) |

RR 0.56 (0.25 to 1.24) |

326 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1,2 |

|

Annual GFR loss (mL/min/1.73 m2) Follow‐up: 2.1 to 5 years |

The mean annual GFR loss ranged across control groups from 6.17 to 6.95 mL/min/1.73 m2 | The mean annual GFR loss in the intervention group was ‐5.40 mL/min/1.73 m2 less than the control group (95% CI ‐8.55 less to ‐2.25 less) | ‐‐ | 359 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate 1 |

|

Death (any cause) Median follow‐up: 2.1 years |

8 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (1 to 162) |

RR 1.85 (0.17 to 20.19) |

262 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,4 |

|

Infection Median follow‐up: 2.1 years |

No events | 11/136** | RR 21.32 (1.27, 358.10) | 262 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2,3 |

|

Malignancy Follow‐up: 6 years |

23 per 1000 | 23 per 1000 (1 to 356) |

RR 1.00 (0.06 to 15.48) |

86 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2,4 |

|

The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio ** Event rate derived from the raw data. A 'per thousand' rate is non‐informative in view of the scarcity of evidence and zero events in the control group | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1 Downgraded due to study limitations including lack of allocation concealment and lack of blinding

2 Downgraded due to imprecision in treatment estimate (consistent with appreciable benefit or harm)

3 Downgraded due to evidence of important statistical heterogeneity

4 Downgraded two levels due to severe imprecision in treatment estimate (consistent with appreciable benefit or harm)

Summary of findings 2. Cytotoxic regimen versus no cytotoxic regimen for IgA nephropathy.

| Cytotoxic regimen versus no cytotoxic regimen for IgA nephropathy | |||||

|

Patient or population: adults and children who have IgA nephropathy proven on renal biopsy Settings: Australia, China, Europe, Japan Intervention: cytotoxic therapy (including combinations of cyclophosphamide or azathioprine with steroid therapy) Comparison: no cytotoxic therapy | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute benefits* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with no cytotoxic therapy | Risk with cytotoxic therapy | ||||

|

End‐stage kidney disease Follow‐up: 1 to 7 years |

166 per 1000 | 105 per 1000 (55 to 199) |

RR 0.63 (0.33 to 1.20) |

463 (7) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1,3 |

|

Complete remission Follow‐up: 0.5 to 5 years |

337 per 1000 | 495 per 1000 (317 to 775) |

RR 1.47 (0.94 to 2.30) |

381 (5) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,3,4 |

| GFR loss ≥ 50% | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable |

|

Annual GFR loss (mL/min/1.73 m2) Follow‐up: 3 years |

The mean GFR loss was 0.01 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the control group | The mean GFR loss in the intervention group was 0.01 mL/min/1.73 m2 lower than the control group (95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.01) | ‐‐ | 162 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1,3 |

|

Death (any cause) Follow‐up: 3 years |

13 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (1 to 199) |

RR 0.98 (0.06 to 15.33) |

162 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

|

Infection Follow‐up: 1 to 7 years |

22 per 1000 | 37 per 1000 (10 to 149) |

RR 1.70 (0.43 to. 6.76) |

268 (4) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

|

Malignancy Follow‐up: 3 years |

No events | 2/82** | RR 4.88 (0.24 to 100.08) |

162 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

|

The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio ** Event rate derived from the raw data. A 'per thousand' rate is non‐informative in view of the scarcity of evidence and zero events in the control group | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1 Downgraded due to study limitations including lack of allocation concealment and lack of blinding

2 Downgraded two levels due to severe imprecision in treatment estimate (consistent with appreciable benefit or harm)

3 Downgraded due to imprecision in treatment estimate (consistent with appreciable benefit or harm)

4 Downgraded due to evidence of important statistical heterogeneity

Summary of findings 3. MMF regimen versus no MMF regimen for IgA nephropathy.

| MMF regimen versus no MMF regimen for IgA nephropathy | |||||

|

Patient or population: adults and children who have IgA nephropathy proven on renal biopsy Settings: Australia, China, Europe Intervention: MMF regimen (includes MMF alone, or in combination with RAS inhibitors or steroids) Comparison: mo MMF regimen | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute benefits* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk without MMF | Risk with MMF | ||||

|

End‐stage kidney disease Follow‐up: 1 to 3 years |

96 per 1000 | 70 per 1000 (15 to 310) |

RR 0.73 (0.16 to 3.23) |

280 (4) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2,3 |

|

Complete remission Follow‐up: 1 to 2 years |

267 per 1000 | 280 per 1000 (195 to 406) |

RR 1.05 (0.73 to 1.52) |

271 (4) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

|

GFR loss ≥ 50% Follow‐up: 2 years |

133 per 1000 | 294 per 1000 (67 to 1000) |

RR 2.21 (0.50 to 9.74) |

32 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

|

Annual GFR loss (mL/min/1.73 m2) Follow‐up: 1 year |

The mean GFR loss was 10.6 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the control group | The mean GFR loss in the intervention group was 2.00 mL/min/1.73 m2 lower than the control group (95% CI ‐25.15 to 29.15) | ‐‐ | 28 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

| Death (any cause) | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable |

|

Infection Follow‐up: 1 to 3 years |

169 per 1000 | 230 per 1000 (147 to 358) |

RR 1.36 (0.87 to 2.12) |

301 (4) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

|

Malignancy Follow‐up: 1 to 3 years |

50 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (2 to 127) |

RR 0.28 (0.03 to 2.54) |

86 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

| The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1 Downgraded due to study limitations including lack of allocation concealment and lack of blinding

2 Downgraded two levels due to severe imprecision in treatment estimate (consistent with appreciable benefit or harm)

3 Downgraded due to evidence of important statistical heterogeneity

Summary of findings 4. Calcineurin inhibitor regimen versus no calcineurin inhibitor regimen for IgA nephropathy.

| Calcineurin inhibitor regimen versus no calcineurin inhibitor regimen for IgA nephropathy | |||||

|

Patient or population: adults and children who have IgA nephropathy proven on renal biopsy Settings: China Intervention: calcineurin inhibitor regimen (includes calcineurin inhibitor alone or in combination with steroids) Comparison: no calcineurin inhibitor regimen | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute benefits* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk without calcineurin inhibitor | Risk with calcineurin inhibitor | ||||

| End‐stage kidney disease | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable |

|

Complete remission Follow‐up: 0.5 to 1 year |

541 per 1000 | 492 per 1000 (325 to 752) |

RR 0.91 (0.60 to 1.39) |

72 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

| GFR loss ≥ 50% | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable |

|

Annual GFR loss (mL/min/ 1.73 m2) |

No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable |

| Death (any cause) | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable |

|

Infection Follow‐up: 1 year |

130 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (4 to 356) |

RR 0.31 (0.03 to 2.74) |

48 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

|

Malignancy Follow‐up: 1 year |

40 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (1 to 338) |

RR 0.36 (0.02 to 8.45) |

48 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

| The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1 Downgraded due to study limitations including lack of allocation concealment and lack of blinding

2 Downgraded two levels due to severe imprecision in treatment estimate (consistent with appreciable benefit or harm)

Summary of findings 5. Mizoribine regimen versus no mizoribine regimen for IgA nephropathy.

| Mizoribine regimen compared with no mizoribine regimen for IgA nephropathy | |||||

|

Patient or population: adults and children who have IgA nephropathy proven on renal biopsy Settings: Japan Intervention: mizoribine regimen (includes mizoribine alone or with RAS inhibitors) Comparison: no mizoribine regimen | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute benefits* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk without mizoribine | Risk with mizoribine | ||||

|

End‐stage kidney disease Follow‐up: 3 years |

48 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 (3 to 718) |

RR 1.00 (0.07 to 14.95) |

42 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

|

Complete remission Follow‐up: 3 years |

467 per 1000 | 887 per 1000 (495 to 1000) |

RR 1.90 (1.06 to 3.43) |

24 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

| GFR loss ≥ 50% | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable |

|

Annual GFR loss (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable |

| Death (any cause) | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable |

|

Infection Follow‐up: 1 to 2.1 years |

60 per 1000 | 91 per 1000 (8 to 969) |

RR 1.52 (0.14 to 16.15) |

104 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2,3 |

|

Malignancy Follow‐up: 3 years |

No events | 1/21** | RR 3.00 (0.13 to 69.70) |

42 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

|

The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. ** Event rate derived from the raw data. A 'per thousand' rate is non‐informative in view of the scarcity of evidence and zero events in the control group | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1 Downgraded due to study limitations including lack of allocation concealment and lack of blinding

2 Downgraded two levels due to severe imprecision in treatment estimate (consistent with appreciable benefit or harm)

3 Downgraded due to evidence of important statistical heterogeneity

Summary of findings 6. Leflunomide regimen versus no leflunomide regimen for IgA nephropathy.

| Leflunomide regimen compared with no leflunomide regimen for IgA nephropathy | |||||

|

Patient or population: adults and children who have IgA nephropathy proven on renal biopsy Settings: China Intervention: leflunomide regimen (includes leflunomide alone or with steroids or RAS inhibitor) Comparison: no leflunomide regimen | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute benefits* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk without leflunomide | Risk with leflunomide | ||||

|

End‐stage kidney disease Follow‐up: 7.3 years |

111 per 1000 | 76 per 1000 (19 to 294) |

RR 0.68 (0.17 to 2.65) |

85 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

|

Complete remission Follow‐up: 0.25 to 7.3 years |

357 per 1000 | 386 per 1000 (286 to 521) |

RR 1.08 (0.80 to 1.46) |

282 (4) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

| GFR loss ≥ 50% | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable |

|

Annual GFR loss (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable |

| Death (any cause) | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable |

|

Infection Follow‐up: 0.5 to 7.3 years |

56 per 1000 | 54 per 1000 (25 to 117) |

RR 0.97 (0.45 to 2.09) |

387 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

| Malignancy | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable |

| The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1 Downgraded due to study limitations including lack of allocation concealment and lack of blinding

2 Downgraded two levels due to severe imprecision in treatment estimate (consistent with appreciable benefit or harm)

See: Table 1: Steroid regimen versus no steroid regimen for treating IgA nephropathy; Table 2: Cytotoxic regimen versus no cytotoxic regiment for treating IgA nephropathy; Table 3: MMF regimen versus no MMF regimen for IgA nephropathy; Table 4: CNI regimen versus no CNI regimen for IgA nephropathy; Table 5: Mizoribine regimen versus no mizoribine regimen for IgA nephropathy; Table 6: Leflunomide regimen versus no leflunomide regimen for IgA nephropathy.

We grouped the included studies into nine treatment comparisons.

Systemic corticosteroid versus no corticosteroid regimen (Julian 1993; Kanno 2003; Katafuchi 2003; Lee 2003; Kobayashi 1996; Koike 2008; Lai 1986; Lv 2009; Manno 2001; NA IgAN 1995; Nuzzi 2009; Pozzi 1999; Shoji 2000; Takeda 1999; TESTING 2017; Welch 1992; Yamauchi 2001)

Locally‐acting steroid versus no locally‐acting steroid (NEFIGAN 2017)

Cytotoxic (CPA, AZA or belimumab) versus no cytotoxic regimen (Ballardie 2002; BRIGHT‐SC 2016; Cheung 2018: Harmankaya 2002; Koitabashi 1996; Lafayette 2017; Locatelli 1999; Stangou 2011; STOP‐IgAN 2008; Yoshikawa 1999; Yoshikawa 2006; Walker 1990a; Woo 1987)

MMF versus no MMF regimen (2nd NA IgAN 2004; Chen 2002; Frisch 2005; Hou 2017; Maes 2004; Tang 2005)

CNI versus no CNI regimen (Kim 2013b; Lai 1987; Liu 2014; Shen 2013)

Mizoribine versus no mizoribine regimen (Hirai 2017; Masutani 2016; Shima 2018; Xie 2011)

Leflunomide versus no leflunomide regimen (Cao 2008; Liu 2010a; Lou 2006; Min 2017; Ni 2005; Shi 2012a; Wu 2016; Zhang 2004)

Steroid plus non‐immunosuppressive agents versus steroid alone (CAST‐IgA 2015; Horita 2007; Kawamura 2014; Segarra 2006)

mTOR inhibitor versus no mTOR inhibitor regimen (Cruzado 2011).

End‐stage kidney disease requiring kidney replacement therapy

In patients mostly with mild to moderate kidney disease and protein excretion of over 1 g/24 hours, steroid treatment was administered generally as oral prednisolone 0.6 to 1 mg/kg during 2 to 4 months of therapy followed by a tapering course for a median follow‐up of 54 months (between 24 and 120 months). Participant follow‐up for occurrence of ESKD was generally between 2 and 10 years. In eight studies, steroid therapy probably reduces the absolute risk of reaching ESKD compared with standard care without steroid therapy or placebo (Analysis 1.1 (8 studies, 741 participants): RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.65; I2 = 0%; moderate certainty evidence). There was moderate statistical heterogeneity in the treatment effects between the studies.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Systemic corticosteroid versus no corticosteroid regimen, Outcome 1 ESKD.

CPA or AZA alone or with concomitant steroid treatment for 3 to 6 months had uncertain effects on ESKD over 2 to 7 years of follow‐up (Analysis 3.1 (7 studies; 463 participants): RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.20; I2 = 34%; low certainty evidence) compared to standard care or placebo without steroid therapy.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cytotoxic versus no cytotoxic regimen, Outcome 1 ESKD.

MMF (1.5 to 2 g/day) with or without steroid therapy administered for between 24 weeks and 3 years had uncertain effects on progression to ESKD when compared with placebo, standard care or steroid alone (Analysis 4.1 (4 studies; 280 participants): RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.16 to 3.23; I2 = 54%; very low certainty evidence). There was moderate statistical heterogeneity in the treatment effects between the studies.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 MMF versus no MMF regimen, Outcome 1 ESKD.

Mizoribine administered at 150 mg/day for 12 months had uncertain effects within a single study in which two ESKD events (one in each group) occurred over 36 months (Analysis 6.1 (42 participants): RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.07 to 14.95; very low certainty evidence).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Mizoribine versus no mizoribine regimen, Outcome 1 ESKD.

Leflunomide (20 mg/day) for 12 months in conjunction with oral prednisone (0.8 mg/day) for 4 to 6 weeks versus prednisone (1.0 mg/day) for 8 to 12 weeks had uncertain effects on ESKD in a single study (Analysis 7.1 (85 participants): RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.17 to 2.65; very low certainty evidence).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Leflunomide versus no leflunomide regimen, Outcome 1 ESKD.

There was no evidence for the effects of CNIs, steroids combined with non‐immunosuppressive agents, or mTOR inhibitors on ESKD.

Complete remission

Prednisone (0.8 to 1 mg/kg/d or 40 to 60 mg/day), methylprednisolone (0.6 to 0.8 mg/kg/day), or prednisolone (40 to 60 mg/day) were administered during 10 weeks to 8 months of therapy followed by a tapering course. Steroid therapy may incur complete remission compared with placebo, standard care or RAS inhibitor therapy during 2 to 5 years follow‐up (Analysis 1.2 (4 studies, 305 participants): RR 1.76, 95% CI 1.03 to 3.01; I2 = 69%; low certainty evidence). There was substantial heterogeneity in treatment effects observed between the studies.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Systemic corticosteroid versus no corticosteroid regimen, Outcome 2 Complete remission.

CPA or AZA with concomitant steroid treatment given for 4 months to 2 years had uncertain effects on complete remission compared to steroid alone, standard care or anticoagulant/antiplatelet during 6 months to 5 years follow‐up (Analysis 3.2 (5 studies, 381 participants): RR 1.47, 95% CI 0.94 to 2.30; I2 = 72%; very low certainty evidence). There was substantial heterogeneity in treatment effects observed between the studies.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cytotoxic versus no cytotoxic regimen, Outcome 2 Complete remission.

MMF (1.5 to 2 g/day) with or without steroid therapy administered given for 6 months to 1 year had uncertain effects on complete remission when compared with placebo, standard care or steroid alone (Analysis 4.2 (4 studies, 271 participants): RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.52; I2 = 0%; very low certainty evidence).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 MMF versus no MMF regimen, Outcome 2 Complete remission.

CNIs (CSA 3 mg/day or tacrolimus 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg/day) were administered during 6 months to 1 year with concomitant steroid treatment had uncertain effects on complete remission (Analysis 5.1 (2 studies, 72 participants): RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.39; I2 = 0%; very low certainty evidence).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) versus no CNI regimen, Outcome 1 Complete remission.

Mizoribine administered at 150 mg/day for 12 months had uncertain effects within a single study in which 15 complete remissions occurred during 36 months follow‐up (Analysis 6.2 (24 participants): RR 1.90, 95% CI 1.06 to 3.43; very low certainty evidence).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Mizoribine versus no mizoribine regimen, Outcome 2 Complete remission.

Leflunomide (10 to 60 mg/day) for 3 to 12 months with or without oral prednisone had uncertain effects on complete remission over 3 to 88 months follow‐up (Analysis 7.2 (4 studies, 282 participants): RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.46; I2 = 0%; very low certainty evidence) compared to prednisone alone or RAS inhibitor.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Leflunomide versus no leflunomide regimen, Outcome 2 Complete remission.

Steroid (steroid pulse followed by prednisolone or prednisolone alone 30 mg followed by a tapering course) for 6 to 24 months with RAS inhibitor or ARB had uncertain effects on complete remission for 24 months follow‐up (Analysis 8.1 (2 studies, 115 participants): RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.31; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence) compared to prednisolone with or without steroid pulse and tonsillectomy.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Steroid plus non‐immunosuppressive agents versus steroid alone, Outcome 1 Complete remission.

There was no evidence for the effects of mTOR inhibitors on complete remission.

Doubling of serum creatinine

Prednisone (0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day or 40 to 60 mg/day) and prednisolone (0.8 mg/kg/day or 20 to 60 mg/day) with or without methylprednisolone (1 g IV) were administered during 10 weeks to 2 years of therapy followed by a tapering course. Steroid therapy may prevent the doubling of SCr compared with standard care or RAS inhibitor therapy during 1 to 10 years follow‐up (Analysis 1.3 (7 studies, 404 participants): RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.65; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Systemic corticosteroid versus no corticosteroid regimen, Outcome 3 Doubling of serum creatinine.

MMF (2 g/day) for up to 3 years had uncertain effects on occurrence of doubling of SCr when compared with placebo or standard care (Analysis 4.3 (2 studies, 74 participants): RR 2.01, 95% CI 0.28 to 14.44; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 MMF versus no MMF regimen, Outcome 3 Doubling of serum creatinine.

Leflunomide (40 mg/day) for 12 months with oral prednisone had uncertain effects on occurrence of doubling of SCr over 88 months follow‐up in a single study (Analysis 7.3 (85 participants): RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.50; low certainty evidence) compared to prednisone alone.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Leflunomide versus no leflunomide regimen, Outcome 3 Doubling of serum creatinine.

There was no evidence for the effects of cytotoxic agents, CNIs, mizoribine, steroids combined with non‐immunosuppressive agents or of mTOR inhibitors on doubling of SCr.

Serum creatinine

Prednisone (0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day or 40 to 60 mg/day) and prednisolone (0.5 to 0.8 mg/kg/day or 20 to 60 mg/day) with or without methylprednisolone (1 g IV) were administered during 4 to 36 months of therapy followed by a tapering course. Steroid therapy had uncertain effects on SCr compared with standard care or other non‐immunosuppressive treatment during 1 to 6 years follow‐up (Analysis 1.4 (7 studies, 211 participants) MD ‐21.07 µmol/L, 95% CI ‐44.12 to 1.99; I2 = 78%; very low certainty evidence). There was substantial heterogeneity in treatment effects observed between the studies.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Systemic corticosteroid versus no corticosteroid regimen, Outcome 4 Serum creatinine.

MMF (1.5 g/day) with steroid therapy administered for 6 months of therapy followed by a tapering course had uncertain effects on SCr when compared with steroid combined with leflunomide in a single study (Analysis 4.4 (40 participants): MD ‐1.58 µmol/L, 95% CI ‐19.29 to 16.13; low certainty evidence).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 MMF versus no MMF regimen, Outcome 4 Serum creatinine.

CSA (5 mg/kg/day) or tacrolimus (0.1 mg/kg/day) administered for 3 to 4 months followed by a tapering course had uncertain effects on SCr when compared with placebo during 4 to 6 months follow‐up (Analysis 5.2 (2 studies, 62 participants): MD 7.75 µmol/L, 95% CI ‐6.76 to 22.27; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) versus no CNI regimen, Outcome 2 Serum creatinine.

Leflunomide (40 to 50 mg/day) for 6 to 12 months followed by a tapering course with oral prednisone had uncertain effects on SCr over 6 to 88 months follow‐up (Analysis 7.4 (2 studies, 125 participants): MD ‐4.29 µmol/L, 95% CI ‐15.81 to 7.24; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence) compared to prednisone with or without MMF.

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Leflunomide versus no leflunomide regimen, Outcome 4 Serum creatinine.

There was no evidence for the effects of cytotoxic agents, mizoribine, steroids combined with non‐immunosuppressive agents or of mTOR inhibitors on SCr.

Glomerular filtration rate

Reduction in glomerular filtration rate (at least 50%)

In the two studies evaluating steroid treatment and reporting this outcome, steroids were administered as prednisone (initially 60 mg/m2) on alternate days or methylprednisolone (0.6 to 0.8 mg/kg/day) were administered during 6 to 24 months of therapy. Participant follow‐up for reduction in GFR of at least 50% was generally over two years. Steroid therapy had uncertain effects on risks of a ≥ 50% reduction compared to fish oil or placebo (Analysis 1.5 (2 studies; 326 participants): RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.24; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Systemic corticosteroid versus no corticosteroid regimen, Outcome 5 GFR loss: ≥ 50%.

MMF administered at 2000 mg for 52 weeks had uncertain effects on the risk of GFR reduction ≥ 50% at 2 years of follow‐up in a single study (Analysis 4.5 (32 participants) RR 2.21, 95% CI 0.50 to 9.74; very low certainty evidence).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 MMF versus no MMF regimen, Outcome 5 GFR loss: ≥ 50%.

Risks of reduction in GFR of at least 50% was not reported for cytotoxic agents, CNIs, mizoribine, leflunomide, steroids combined with non‐immunosuppressive agents, or mTOR inhibitors.

Reduction glomerular filtration rate (at least 25%)

MMF (2 g/day) had uncertain effects on the risk of GFR reduction ≥ 35% over 3 years in a single study (Analysis 4.6 (34 participants): RR 2.17, 95% CI 0.53 to 8.88; low certainty evidence).

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 MMF versus no MMF regimen, Outcome 6 GFR loss: ≥ 25%.

Risks of reduction in GFR of at least 25% was not reported for steroids, cytotoxic agents, CNIs, mizoribine, leflunomide, steroids combined with non‐immunosuppressive agents, or mTOR inhibitors.

Annual glomerular filtration loss

Prednisone (1 mg/kg/day) or methylprednisolone (0.6 to 0.8 mg/kg/d were administered during 6 to 8 months of therapy followed by a tapering course. Steroid therapy probably prevents annual GFR loss compared with placebo or RAS inhibitors during 2.1 to 5 years follow‐up (Analysis 1.6 (2 studies, 359 participants): MD ‐5.40 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI ‐8.55 to ‐2.25; I2 = 0%; moderate certainty evidence).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Systemic corticosteroid versus no corticosteroid regimen, Outcome 6 Annual GFR loss [mL/min/1.73 m2].

CPA followed by AZA with concomitant steroid treatment given for 6 months had uncertain effects on annual GFR loss compared to standard care during 3 years follow‐up in a single study (Analysis 3.3 (162 participants): MD ‐0.01 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.01; low certainty evidence).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cytotoxic versus no cytotoxic regimen, Outcome 3 Annual GFR loss [mL/min/1.73 m2].

MMF (2 g/day) had uncertain effects on annual GFR loss compared to placebo during 12 months follow‐up in a single study (Analysis 4.7 (28 participants): MD 2.0 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI ‐25.15 to 29.15; very low certainty evidence).

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 MMF versus no MMF regimen, Outcome 7 Annual GFR loss [mL/min/1.73 m2].

There was no evidence for the effects of CNIs, mizoribine, leflunomide, steroids combined with non‐immunosuppressive agents, or mTOR inhibitors on annual GFR loss.

Glomerular filtration rate (any measure)

Prednisolone (0.8 mg/kg/day or 40 to 60 mg/day) and prednisone (0.5 mg/kg/day or 40 to 60 mg/day) with or without methylprednisolone (1 g IV) were administered during 4 to 18 months of therapy followed by a tapering course. Steroid therapy had uncertain effects on GFR compared with standard care or other non‐immunosuppressive treatment during 1 to 10 years follow‐up (Analysis 1.7 (4 studies, 138 participants): MD 17.87 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI 4.93 to 30.82; I2 = 53%; very low certainty evidence). There was moderate heterogeneity in treatment effects observed between the studies.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Systemic corticosteroid versus no corticosteroid regimen, Outcome 7 GFR (any measure).

AZA (1 to 2 mg/kg/day) with concomitant steroid treatment given for 1 to 2 years had uncertain effects on GFR compared to steroid alone or anticoagulant/antiplatelet therapy (Analysis 3.4 (3 studies, 174 participants): MD 3.07 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI ‐6.57 to 12.72; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cytotoxic versus no cytotoxic regimen, Outcome 4 GFR (any measure) [mL/min/1.73 m2].

MMF (2 g/day) administered for 12 months had uncertain effects on GFR when compared with placebo in a single study (Analysis 4.8 (28 participants): MD ‐2.50 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI ‐30.79 to 25.79; low certainty evidence).

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 MMF versus no MMF regimen, Outcome 8 GFR (any measure) [mL/min/1.73 m2].

CSA (3 to 5 mg/day) with or without concomitant steroid treatment and tacrolimus (0.1 mg/kg/day) for 3 to 12 months had uncertain effects on GFR during 4 to 60 months follow‐up (Analysis 5.3 (3 studies, 110 participants): MD ‐0.18 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI ‐7.42 to 7.07; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) versus no CNI regimen, Outcome 3 GFR (any measure).

Mizoribine (150 to 250 mg/day) with RAS inhibitor treatment had uncertain effects on GFR when compared with RAS inhibitor alone in a single study (Analysis 6.3 (65 participants): MD 2.05 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI ‐10.16 to 14.26; low certainty evidence).

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Mizoribine versus no mizoribine regimen, Outcome 3 GFR (any measure).

Leflunomide (40 to 60 mg/day) for 6 to 12 months with or without oral prednisone had uncertain effects on GFR over 6 to 88 months follow‐up (Analysis 7.5 (2 studies, 131 participants): MD 11.11 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI ‐3.32 to 25.55; I2 = 62%; very low certainty evidence) compared to prednisone alone or RAS inhibitor. There was substantial heterogeneity in treatment effects observed between the studies.

7.5. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Leflunomide versus no leflunomide regimen, Outcome 5 GFR (any measure).

Prednisolone (30 mg) followed by a tapering course for 24 months combined with ARB had uncertain effects on GFR in a single study (Analysis 8.2 (38 participants): MD 16.00 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI ‐6.89 to 38.89; low certainty evidence) compared to prednisolone alone.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Steroid plus non‐immunosuppressive agents versus steroid alone, Outcome 2 GFR (any measure) [mL/min/1.73 m2].

There was no evidence for the effects of mTOR inhibitors on GFR.

Urinary protein excretion

Methylprednisolone (0.6 to 0.8 mg/kg/day), prednisolone (0.4 to 0.8 mg/kg/day or 20 to 60 mg/day) and prednisone (0.5 mg/kg/day or 40 to 60 mg/day) with or without methylprednisolone (1 g IV) were administered during 4 to 24 months of therapy followed by a tapering course. Steroid therapy may lower urinary protein excretion compared with placebo, standard care or other non‐immunosuppressive treatment during 1 to 10 years follow‐up (Analysis 1.8 (10 studies, 705 participants): MD ‐0.58 g/24 h, 95% CI ‐0.84 to ‐0.33; I2 = 60%;low certainty evidence). There was substantial heterogeneity in treatment effects observed between the studies.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Systemic corticosteroid versus no corticosteroid regimen, Outcome 8 Urinary protein excretion.

CPA and/or AZA with concomitant steroid treatment given for 3 to 24 months had uncertain effects on urinary protein excretion compared to standard care, steroid alone or other non‐immunosuppressive treatment (Analysis 3.5 (5 studies, 255 participants): MD ‐0.77 g/24 h, 95% CI ‐1.80 to 0.26; I2 = 98%; very low certainty evidence). There was substantial heterogeneity in treatment effects observed between the studies.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cytotoxic versus no cytotoxic regimen, Outcome 5 Urinary protein excretion.

MMF (1.5 to 2 g/day) with or without steroid therapy administered for up to 3 years had uncertain effects on urinary protein excretion when compared with placebo, standard care or steroid with leflunomide over 6 months to 3 years follow‐up (Analysis 4.9 (5 studies, 172 participants): MD ‐0.06 g/24 h, 95% CI ‐0.92 to 0.81; I2 = 96%; very low certainty evidence). There was substantial heterogeneity in treatment effects observed between the studies.

4.9. Analysis.

Comparison 4 MMF versus no MMF regimen, Outcome 9 Urinary protein excretion.

CSA (3 to 5 mg/day) with or without concomitant steroid treatment or tacrolimus (0.1 mg/kg/day) for 3 to 12 months had uncertain effects on urinary protein excretion during 4 to 60 months follow‐up (Analysis 5.4 (3 studies, 110 participants): MD ‐0.50 g/24 h, 95% CI ‐1.12 to 0.12; I2 = 82%; very low certainty evidence). There was substantial heterogeneity in treatment effects observed between the studies.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) versus no CNI regimen, Outcome 4 Urinary protein excretion.

Mizoribine (150 to 250 mg/day) with RAS inhibitor or steroid treatment had uncertain effect on reduction of urinary protein excretion when compared with RAS inhibitor or steroid alone (Analysis 6.4 (2 studies, 105 participants): MD ‐0.04 g/24 h, 95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.22; low certainty evidence).

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Mizoribine versus no mizoribine regimen, Outcome 4 Urinary protein excretion.

Leflunomide (20 to 50 mg/day) with or without oral prednisone had uncertain effects on urinary protein excretion over 3 to 6 months follow‐up (Analysis 7.6 (3 studies, 125 participants): MD 0.20 g/24 h, 95% CI ‐0.60 to 1.00; I2 = 69%; very low certainty evidence) compared to steroid with or without MMF. There was substantial heterogeneity in treatment effects observed between the studies.

7.6. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Leflunomide versus no leflunomide regimen, Outcome 6 Urinary protein excretion.

Prednisolone (30 mg) followed by a tapering course for 24 months combined with ARB had uncertain effect on reduction of urinary protein excretion in a single study (Analysis 8.3 (38 participants): MD ‐0.20 g/24 h, 95% CI ‐0.26 to ‐0.14; low certainty evidence) compared to prednisolone alone.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Steroid plus non‐immunosuppressive agents versus steroid alone, Outcome 3 Urinary protein excretion.

Sirolimus (1 mg/day) had uncertain effect on reduction of urinary protein excretion during 12 months follow‐up compared with no mTOR inhibitors in a single study (Analysis 9.1 (23 participants): MD ‐0.80 g/24 h, 95% CI ‐1.83 to 0.23; low certainty evidence).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 mTORi versus no mTORi regimen, Outcome 1 Urinary protein excretion.

Death (any cause)

Due to the rarity of death during follow‐up with this condition, the effects of all treatment strategies on the outcome of total death were either imprecisely known or not reported.

One parallel‐group study measured the effects of steroid versus placebo on the risks of death (any cause). During a median of 25 months, 3 deaths among 262 participants were reported. The comparative effects of treatment on death (any cause) was uncertain with an imprecise treatment effect (Analysis 1.9: RR 1.85, 95% CI 0.17 to 20.19; very low certainty evidence). Similarly, in a parallel‐group study evaluating CPA followed by AZA plus steroid versus steroid alone for 36 months, two deaths (one in each group) were recorded and treatment effects were uncertain (Analysis 3.6 (162 participants): RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.33; very low certainty evidence).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Systemic corticosteroid versus no corticosteroid regimen, Outcome 9 Death (any cause).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cytotoxic versus no cytotoxic regimen, Outcome 6 Death (any cause).

Death (any cause) was not reported for other treatment regimens including MMF, CNIs, mizoribine, leflunomide, steroid therapy combined with non‐immunosuppressive agents and mTOR inhibitors.

Infection