Abstract

Background

Recruiting participants to trials can be extremely difficult. Identifying strategies that improve trial recruitment would benefit both trialists and health research.

Objectives

To quantify the effects of strategies for improving recruitment of participants to randomised trials. A secondary objective is to assess the evidence for the effect of the research setting (e.g. primary care versus secondary care) on recruitment.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Methodology Review Group Specialised Register (CMR) in the Cochrane Library (July 2012, searched 11 February 2015); MEDLINE and MEDLINE In Process (OVID) (1946 to 10 February 2015); Embase (OVID) (1996 to 2015 Week 06); Science Citation Index & Social Science Citation Index (ISI) (2009 to 11 February 2015) and ERIC (EBSCO) (2009 to 11 February 2015).

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised trials of methods to increase recruitment to randomised trials. This includes non‐healthcare studies and studies recruiting to hypothetical trials. We excluded studies aiming to increase response rates to questionnaires or trial retention and those evaluating incentives and disincentives for clinicians to recruit participants.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data on: the method evaluated; country in which the study was carried out; nature of the population; nature of the study setting; nature of the study to be recruited into; randomisation or quasi‐randomisation method; and numbers and proportions in each intervention group. We used a risk difference to estimate the absolute improvement and the 95% confidence interval (CI) to describe the effect in individual trials. We assessed heterogeneity between trial results. We used GRADE to judge the certainty we had in the evidence coming from each comparison.

Main results

We identified 68 eligible trials (24 new to this update) with more than 74,000 participants. There were 63 studies involving interventions aimed directly at trial participants, while five evaluated interventions aimed at people recruiting participants. All studies were in health care.

We found 72 comparisons, but just three are supported by high‐certainty evidence according to GRADE.

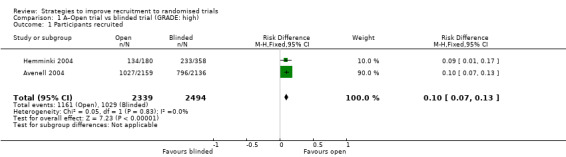

1. Open trials rather than blinded, placebo trials. The absolute improvement was 10% (95% CI 7% to 13%).

2. Telephone reminders to people who do not respond to a postal invitation. The absolute improvement was 6% (95% CI 3% to 9%). This result applies to trials that have low underlying recruitment. We are less certain for trials that start out with moderately good recruitment (i.e. over 10%).

3. Using a particular, bespoke, user‐testing approach to develop participant information leaflets. This method involved spending a lot of time working with the target population for recruitment to decide on the content, format and appearance of the participant information leaflet. This made little or no difference to recruitment: absolute improvement was 1% (95% CI −1% to 3%).

We had moderate‐certainty evidence for eight other comparisons; our confidence was reduced for most of these because the results came from a single study. Three of the methods were changes to trial management, three were changes to how potential participants received information, one was aimed at recruiters, and the last was a test of financial incentives. All of these comparisons would benefit from other researchers replicating the evaluation. There were no evaluations in paediatric trials.

We had much less confidence in the other 61 comparisons because the studies had design flaws, were single studies, had very uncertain results or were hypothetical (mock) trials rather than real ones.

Authors' conclusions

The literature on interventions to improve recruitment to trials has plenty of variety but little depth. Only 3 of 72 comparisons are supported by high‐certainty evidence according to GRADE: having an open trial and using telephone reminders to non‐responders to postal interventions both increase recruitment; a specialised way of developing participant information leaflets had little or no effect. The methodology research community should improve the evidence base by replicating evaluations of existing strategies, rather than developing and testing new ones.

Plain language summary

What improves trial recruitment?

Key messages

We had high‐certainty evidence for three methods to improve recruitment, two of which are effective:

1. Telling people what they are receiving in the trial rather than not telling them improves recruitment.

2. Phoning people who do not respond to a postal invitation is also effective (although we are not certain this works as well in all trials).

3. Using a tailored, user‐testing approach to develop participant information leaflets makes little or no difference to recruitment.

Of the 72 strategies tested, only 7 involved more than one study. We need more studies to understand whether they work or not.

Our question

We reviewed the evidence about the effect of things trial teams do to try and improve recruitment to their trials. We found 68 studies involving more than 74,000 people.

Background

Finding participants for trials can be difficult, and trial teams try many things to improve recruitment. It is important to know whether these actually work. Our review looked for studies that examined this question using chance to allocate people to different recruitment strategies because this is the fairest way of seeing if one approach is better than another.

Key results

We found 68 studies including 72 comparisons. We have high certainty in what we found for only three of these.

1. Telling people what they are receiving in the trial rather than not telling them improves recruitment. Our best estimate is that if 100 people were told what they were receiving in a randomised trial, and 100 people were not, 10 more would take part n the group who knew. There is some uncertainty though: it could be as few as 7 more per hundred, or as many as 13 more.

2. Phoning people who do not respond to a postal invitation to take part is also effective. Our best estimate is that if investigators called 100 people who did not respond to a postal invitation, and did not call 100 others, 6 more would take part in the trial among the group who received a call. However, this number could be as few as 3 more per hundred, or as many as 9 more.

3. Using a tailored, user‐testing approach to develop participant information leaflets did not make much difference. The researchers who tested this method spent a lot of time working with people like those to be recruited to decide what should be in the participant information leaflet and what it should look like. Our best estimate is that if 100 people got the new leaflet, 1 more would take part in the trial compared to 100 who got the old leaflet. However, there is some uncertainty, and it could be 1 fewer (i.e. worse than the old leaflet) per hundred, or as many as 3 more.

We had moderate certainty in what we found for eight other comparisons; our confidence was reduced for most of these because the method had been tested in only one study. We had much less confidence in the other 61 comparisons because the studies had design flaws, were the only studies to look at a particular method, had a very uncertain result or were mock trials rather than real ones.

Study characteristics

The 68 included studies covered a very wide range of disease areas, including antenatal care, cancer, home safety, hypertension, podiatry, smoking cessation and surgery. Primary, secondary and community care were included. The size of the studies ranged from 15 to 14,467 participants. Studies came from 12 countries; there was also one multinational study involving 19 countries. The USA and UK dominated with 25 and 22 studies, respectively. The next largest contribution came from Australia with eight studies.

The small print

Our search updated our 2010 review and is current to February 2015. We also identified six studies published after 2015 outside the search. The review includes 24 mock trials where the researchers asked people about whether they would take part in an imaginary trial. We have not presented or discussed their results because it is hard to see how the findings relate to real trial decisions.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Open trial versus blinded trial.

| Open RCT versus blinded RCT | |||||

| Patient or population: individuals eligible for a trial Settings: any Intervention: open trial Comparison: blinded, placebo trial | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Effect with blinded trial | Effect with open trial | ||||

| Number recruited | As measureda | RR 1.25 (1.18 to 1.34) | 4833 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

| 41 per 100 | 50 per 100 (51 to 55) | ||||

| Lowb | |||||

| 10 per 100 | 13 per 100 (12 to 13) | ||||

| Moderateb | |||||

| 30 per 100 | 38 per 100 (35 to 40) | ||||

| Highb | |||||

| 50 per 100 | 63 per 100 (59 to 67) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect for the open trial (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the the comparison group (blinded trial) and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

aThis is the baseline recruitment measured in the studies presented in the 'Summary of findings' table. bWe selected the low, moderate and high illustrative recruitment levels of 10%, 30% and 50% based on our prior experience with trial recruitment.

Summary of findings 2. Telephone reminder versus no telephone reminder.

| Telephone reminder versus no telephone reminder | ||||||

| Patient or population: individuals eligible for a trial Settings: any Intervention: telephone reminder Comparison: no telephone reminder | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Effect with no telephone reminder | Effect with telephone reminder | |||||

| Number recruited | As measureda | RR 1.90 (1.35 to 2.67) | 978 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Highc | Both included studies had very low baseline recruitment of < 10%. | |

| 6 per 100 | 11 per 100 (8 to 16) |

|||||

| Lowb | ||||||

| 10 per 100 | 19 per 100 (14 to 27) | |||||

| Moderateb | ||||||

| 30 per 100 | 57 per 100 (41 to 80) | |||||

| Highb | ||||||

| 50 per 100 | 95 per 100 (68 to 100) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect with the telephone reminder (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group (no reminder) and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aThis is the baseline recruitment measured in the studies presented in the 'Summary of findings' table. bWe selected the low, moderate and high illustrative recruitment levels of 10%, 30% and 50% based on our prior experience with trial recruitment.. cThe evidence for this intervention comes entirely from trials with low (< 10%) underlying recruitment. When applied to trials with higher recruitment we would downgrade the assessment of certainty to moderate due to indirectness.

Summary of findings 3. Bespoke, user‐tested participant information leaflet (PIL) vs usual PIL.

| Bespoke user‐tested participant information leaflet (PIL) vs usual PIL | |||||

| Patient or population: individuals eligible for trial Settings: any Intervention: bespoke, user‐tested PIL Comparison: usual PIL | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Effect with usual PIL | Effect with bespoke user‐tested PIL | ||||

| Willingness to participate/number recruited | As measureda | RR 1.15 (0.92 to 1.44) | 6634 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

| 5 per 100 |

6 per 100 (5 to 7) |

||||

| Lowb | |||||

| 10 per 100 | 12 per 100 (9 to 14) | ||||

| Moderateb | |||||

| 30 per 100 | 35 per 100 (28 to 43) | ||||

| Highb | |||||

| 50 per 100 | 58 per 100 (46 to 72) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect with the bespoke user‐tested PIL (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group (usual PIL) and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

aThis is the baseline recruitment measured in the studies presented in the 'Summary of findings' table. bWe selected the low, moderate and high illustrative recruitment levels of 10%, 30% and 50% based on our prior experience with trial recruitment..

Summary of findings 4. Brief participant information leaflet (PIL) vs usual PIL.

| Brief participant information leaflet (PIL) vs usual PIL | |||||

| Patient or population: individuals eligible for a trial Settings: any Intervention: brief PIL Comparison: usual PIL | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Effect with usual PIL | Effect with brief PIL | ||||

| Number recruited | As measureda | RR 1.00 (0.93 to 1.07) | 4633 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | |

| 33 per 100 |

33 per 100 (31 to 35) |

||||

| Lowb | |||||

| 10 per 100 | 10 per 100 (9 to 11) | ||||

| Moderateb | |||||

| 30 per 100 | 30 per 100 (28 to 32) | ||||

| Highb | |||||

| 50 per 100 | 50 per 100 (47 to 54) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect with the brief PIL (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group (usual PIL) and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

aThis is the baseline recruitment measured in the studies presented in the 'Summary of findings' table. bWe selected the low, moderate and high illustrative recruitment levels of 10%, 30% and 50% based on our prior experience with trial recruitment. cWe downgraded the certainty by 1 level because of indirectness: Chen 2011 actually measures entry to pre‐randomisation phase, not recruitment.

Summary of findings 5. Participant information leaflet (PIL) developed with feedback from users vs usual PIL.

| Participant information leaflet (PIL) developed with feedback from users vs usual PIL | |||||

| Patient or population: individuals eligible for a trial Settings: any Intervention: PIL developed with feedback from users Comparison: usual PIL | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Effect with usual PIL | Effect with PIL developed with feedback from users | ||||

| Number recruited | As measureda | RR 1.09 (0.96 to 1.25) | 16763 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | |

| 5 per 100 |

5 per 100 (5 to 6) |

||||

| Lowb | |||||

| 10 per 100 | 11 per 100 (10 to 13) | ||||

| Moderateb | |||||

| 30 per 100 | 33 per 100 (29 to 38) | ||||

| Highb | |||||

| 50 per 100 | 55 per 100 (48 to 63) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect with a PIL developed with feedback from users (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group (usual PIL) and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

aThis is the baseline recruitment measured in the studies presented in the 'Summary of findings' table. bWe selected the low, moderate and high illustrative recruitment levels of 10%, 30% and 50% based on our prior experience with trial recruitment. cWe downgraded evidence by 1 level because of indirectness: Chen 2011 actually measures entry to pre‐randomisation phase, not recruitment.

Summary of findings 6. Providing information by video versus by standard means alone.

| Video information versus standard information alone | |||||

| Patient or population: individuals eligible for trial Settings: any Intervention: video information Comparison: standard information (mixed but not including video) | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Effect with standard information | Effect with video information | ||||

| Number recruited | As measureda | RR 1.08 (0.89 to 1.31) | 4695 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc, d, e | |

| 33 per 100 |

36 per 100 (29 to 43) |

||||

| Lowb | |||||

| 10 per 100 | 11 per 100 (9 to 13) | ||||

| Moderateb | |||||

| 30 per 100 | 32 per 100 (27 to 39) | ||||

| Highb | |||||

| 50 per 100 | 54 per 100 (45 to 66) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect with the video information (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group (standard information) and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

aThis is the baseline recruitment measured in the studies presented in the 'Summary of findings' table. bWe selected the low, moderate and high illustrative recruitment levels of 10%, 30% and 50% based on our prior experience with trial recruitment. cWe downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations: both Du 2008 and Du 2009 were at unclear risk of bias. dWe downgraded 1 level because of inconsistency. All 3 studies suggest little or no difference in recruitment due to the intervention but the Hutchison 2007 point estimate was in favour of control, while that of Du 2008 and Du 2009 studies was in favour of the intervention. eWe downgraded 1 level because of imprecision and wide CIs.

Summary of findings 7. Financial incentive vs no incentive.

| Financial incentive vs no incentive | |||||

| Patient or population: individuals eligible for a trial Settings: any Intervention: financial incentive Comparison: no incentive | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Effect with no incentive | Effect with financial incentive | ||||

| Number recruited | As measureda | RR 1.48 (0.85 to 2.58) | 1506 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | |

| 9 per 100 |

13 per 100 (8 to 23) |

||||

| Lowb | |||||

| 10 per 100 | 15 per 100 (9 to 26) | ||||

| Moderateb | |||||

| 30 per 100 | 44 per 100 (26 to 77) | ||||

| Highb | |||||

| 50 per 100 | 74 per 100 (43 to 100) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect with a financial incentive (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group (no incentive) and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

aThis is the baseline recruitment measured in the studies presented in the 'Summary of findings' table. b We selected the low, moderate and high illustrative recruitment levels of 10%, 30% and 50% based on our prior experience with trial recruitment. cWe downgraded 1 level for inconsistency. There was substantial heterogeneity, I2 = 65%.

Background

All randomised trials need to recruit participants, but this is often a challenge. Poor recruitment can lead to an underpowered study, which may report clinically relevant effects as statistically non‐significant. A non‐significant finding increases the risk that an effective intervention will be abandoned before its true value is established, or that there will be a delay in demonstrating this value while more trials or meta‐analyses are done. Underpowered trials also raise an ethical problem: trialists have exposed participants to an intervention with uncertain benefit but may still be unable to determine whether the intervention does more good than harm on completion. Poor recruitment can also lead to the extension of the trial, increasing costs.

Although investigations differ in their estimates of how many studies achieve their recruitment targets, the proportion is likely to be less than half (Charlson 1984; Foy 2003; Haidich 2001; McDonald 2006; Sully 2013). For example, McDonald 2006 found that only 38 (31%) of 114 trials achieved their original recruitment target, and 65 (53%) were extended. More recent replications of this work by Sully 2013 and Walters 2017 found that the number of trials meeting recruitment targets had increased to around 50%. In Sully 2013, the overall start to recruitment was delayed in 47 (41%) trials and early recruitment problems occurred in 77 (63%). The costs of poor recruitment can be huge (Kitterman 2011).

Trialists use many interventions to improve recruitment (see for example Caldwell 2010, Watson 2006 and Prescott 1999), but it is generally difficult to predict their effect.

This review updates our previous reviews (Treweek 2010; Treweek 2013). In addition to updating the search, we have made some important changes that affect how studies are selected for presentation in the Results and Discussion sections; essentially we neither present nor discuss studies that we consider are at high risk of bias unless it was possible to include them in a meta‐analysis.

Objectives

To quantify the effects of strategies for improving recruitment of participants to randomised trials. A secondary objective is to assess the evidence for the effect of the research setting (e.g. primary care versus secondary care) on recruitment.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised and quasi‐randomised trials of interventions to improve recruitment of participants to randomised trials.

Types of data

Randomised and quasi‐randomised trials of recruitment strategies set in the context of trials but not limited to health care; interventions that work in other fields (e.g. education, housing) could be applicable to healthcare settings. Strategies both within real settings and in hypothetical trials (studies that ask potential participants whether they would take part in a trial if it was run but the trial does not actually exist) are eligible for this version of the review.

However, in future versions of this review we will exclude hypothetical trials since we consider their design to confer a high risk of bias because the recruitment decision is not a real one; many also have other methodological problems. The three main reasons for excluding these trials in future versions of the review are as follows.

The relevance of the results of hypothetical trials will always be in doubt because of uncertainty as to how people would have reacted had the decision to take part in a trial been real rather than hypothetical.

It is possible to study recruitment interventions in real trials, avoiding the above problem.

Now that the number of evaluations in real trials has increased, we do not think the trade‐off between value added and work involved to include hypothetical trials is worthwhile for future versions of this review.

We excluded research into ways to improve questionnaire response and research looking at incentives and disincentives for clinicians to recruit participants to trials, as complementary Cochrane Methodology Reviews address these issues (Edwards 2009; Rendell 2007; Preston 2016). We also excluded studies of retention strategies, as a Cochrane Methodology Review on strategies to reduce attrition from trials already exists (Brueton 2013).

Types of methods

Any intervention that aimed to improve recruitment of participants to a randomised trial. The interventions being studied could be directed at potential participants (e.g. patients being randomised to a trial), collaborators (e.g. clinicians recruiting patients for a trial), or others (e.g. research ethics committees). Examples of such interventions are signed letters introducing the trial from influential people, alternative methods of providing information about the trial to potential participants, presenting ethics committees with (and getting approval for) a ranked list of recruitment strategies that might be used depending how recruitment goes so as to avoid delays before trials teams can implement additional recruitment strategies, additional training for collaborators, financial incentives for participants, telephone follow‐up of expressions of interest and modifications to the design of the trial (e.g. using a preference design).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Proportion of eligible individuals or centres recruited.

Secondary outcomes

None.

Note: the lack of any secondary outcomes is a change from the previous version of the review, which gave 'Rate at which participants were recruited' as a secondary outcome. We have removed this because rate is rarely reported. We will continue to report rate of recruitment if the primary outcome is not available but will no longer consider it as a secondary outcome. We will reconsider this decision in future versions of this review.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the following electronic databases without language restriction for eligible studies.

The Cochrane Methodology Review Group Specialised Register (CMR) in the Cochrane Library (July 2012; searched 11 February 2015).

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In Process (OVID) (1946 to 10 February 2015).

Embase (OVID) (1996 to 2015 Week 06).

Science Citation Index & Social Science Citation Index (ISI) (2009 to 11 February 2015)

ERIC (EBSCO) (2009 to 11 February 2015).

Appendix 1 details the full search strategies for all databases. We downloaded the search results to Endnote reference management software and de‐duplicated them.

Data collection and analysis

We prepared a revised protocol for this updated review, including it as Appendix 2 to make it available alongside this review in the Cochrane Library.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of all references identified by the search strategy. We obtained the full versions of papers not definitely excluded at that stage for detailed review. Two review authors independently assessed all potentially eligible studies to determine if they met the inclusion criteria. We discussed differences of opinion and when necessary, a third review author read the full papers.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently carried out data extraction for each included record (using a proforma specifically designed for the purpose). We resolved differences in data extraction by discussion. We extracted data on the method evaluated; country where the study took place; nature of the population; nature of the study setting; nature of the study to be recruited into; randomisation or quasi‐randomisation method; and numbers and proportions of participants in the intervention and comparator groups of the study comparing recruitment strategies.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Cochrane Risk of Bias tool), including reassessing all 44 of the included studies from the previous version of this review carried forward into the update. We used GRADE on all studies where relevant data were available (Guyatt 2008). Where we have done a meta‐analysis, we provide the details of the GRADE assessment in the relevant 'Summary of findings' table. Where we used GRADE on a single study, we used the following rules for assigning a GRADE rating of high, moderate, low or very low certainty.

Baseline rating: all studies start at high.

Study limitations: downgrade all studies at high risk of bias by two levels; downgrade all studies at uncertain risk of bias by one level.

Inconsistency: assume no serious inconsistency.

Indirectness: downgrade all hypothetical studies by two levels.

Imprecision: downgrade all single studies by one level because of the sparsity of data; downgrade by a further level if the confidence interval is wide and includes a risk difference of 0.

Reporting bias: assume no serious reporting bias.

At least two reviewers performed all GRADE assessments. We generated 'Summary of findings' tables using only studies with real recruitment (i.e. not data for hypothetical studies). We present information on risk of bias for all included studies in Characteristics of included studies.

Although we did not exclude studies because of a high of risk of bias, we do not mention them in the text of the Results or Discussion because of the low confidence we have in the data they present, except in cases where we could include them in a meta‐analysis and interpret the datatogether with data from other studies.

Studies at high risk of bias do appear in Data and analyses, but we suggest that readers use these data only to make decisions as to whether they would like to evaluate the intervention themselves in a more rigorous way. We do not believe the data support judgements about effect.

Data for hypothetical studies are included in Data and analyses for this version of the review. We will exclude these studies from future versions of this review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We sought statistical evidence of heterogeneity of results of trials using the Chi2 test for heterogeneity, and we quantified the degree of heterogeneity observed in the results using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). Where we detected substantial heterogeneity, we informally investigated possible explanations and summarised the data using a random‐effects analysis if appropriate. We planned to explore the following factors in subgroup analyses, assuming enough studies were identified, as we believed that these were plausible explanations for heterogeneity.

Type of design used to evaluate recruitment strategies (randomised versus quasi‐randomised) and allocation concealment (adequate versus inadequate or unclear).

Setting of the study recruiting participants (e.g. primary versus secondary care; healthcare versus non‐healthcare settings).

Disease area in which the evaluation was done (e.g. cancer versus lifestyle change).

Design of the study recruiting participants (e.g. open versus blinded studies, trials with placebo arms versus those without).

Target group (e.g. ethics committees, clinicians, patients).

Recruitment to hypothetical versus real trials (future versions of this review, which will exclude hypothetical trials, will not include this subgroup).

Assessment of reporting biases

We investigated reporting (publication) bias for the primary outcomes using a funnel plot where 10 or more studies were available.

Data synthesis

We grouped trials according to the type of intervention based on the categorisation used in the Online Resource for Recruitment research in Clinical triAls (ORRCA) project. We split one ORRCA category (Recruitment Information Needs) into two so as to separate out interventions aimed at the consent process from those aimed at more general participant information. This classification results in seven categories.

Design (category A). This includes changes to the general design of the trial specifically done to increase recruitment.

Pre‐trial planning (category B). This includes work done before the trial starts (possibly in a separate study) to explicitly make it more likely that recruitment will be successful.

Trial conduct changes (category C). This includes initiatives implemented once the trial has started such as better ways of identifying participants, changes to how data are collected, changes to the type of data collected and tailoring recruitment to different types of participant.

Modifications to the consent process (category D). This includes changes to the staff member helping with consent, when consent is taken, what sort of consent information is presented and how it is presented.

Modification to the information given to potential participants about the trial (category E). This includes who provides it, when, where what sort of information is presented, how the information is presented.

Interventions aimed at the recruiter or recruitment site (category F). This includes anything that is aimed at the recruiter or recruitment site staff rather than the person being recruited, such as changes to training.

Incentives (category G). Financial and other incentives for participants (but not staff, which is covered by a separate review).

We present results as risk differences (RD) with the associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) where sufficient data were available. We only included cluster‐randomised trials in the meta‐analysis if sufficient data were reported to allow inclusion of analyses that adjusted for clustering; an odds ratio (OR) was used as the summary effect in the meta‐analysis result if risk difference or risk ratio clustering adjusted analyses were not possible with available data. Where two or more studies could be included in a meta‐analyses, we used a fixed‐effect approach to produce a pooled estimate in the absence of substantial heterogeneity.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

We screened 25,432 titles and abstracts (9098 in this update) and sought the full text of 377 records (76 in this update) to confirm inclusion or clarify uncertainties regarding eligibility, generally due to the lack of an abstract. We were able to obtain the full text of 374 of these articles; the remaining three records were not retrievable because the title or abstract reference was incomplete or incorrect.

Additionally, we retrieved the full text of six articles identified outside the search. A colleague identified Fleissig 2001 as missed in the previous version of the review; our search strategy had picked up the article, but we had rejected it in error during abstract checking. Man 2015a and Man 2015b (a single study describing two embedded recruitment trials), Jennings 2015a, Jennings 2015b, Jennings 2015c, Jennings 2015d, Jennings 2015e (a single study describing five embedded recruitment trials), Foss 2016, Lee 2017 and Cockayne 2017 are more recent studies that we identified while updating the review. We excluded one study that we had included in the previous version of the review, Harris 2008, because it was not recruiting to a trial and was therefore ineligible.

A total of 68 studies were eligible for inclusion. Studies came from 12 countries; there was also one multinational study involving 19 countries. The USA and UK dominated, with 25 and 22 studies, respectively. The next largest was Australia with eight studies. The full breakdown is given in Table 8.

1. Countries where the included studies took place.

| Country | Number of studies |

| Australia | 8 |

| Austria | 1 |

| Canada | 4 |

| Denmark | 1 |

| Estonia | 1 |

| France | 1 |

| Italy | 1 |

| Multinational | 1 (involved 19 countries) |

| Norway | 1 |

| Sweden | 1 |

| Tanzania | 1 |

| UK | 22 |

| USA | 25 |

There were 63 studies involving interventions aimed directly at trial participants, and five evaluated interventions aimed at those recruiting participants. At least 74,519 individuals were involved in the 68 studies; it was not clear how many participants were recruited in two studies. The figure of 74,519 includes both individuals who were recruited as well as those who were approached about recruitment but declined. A breakdown of participant numbers is given in Appendix 3.

There were too few studies evaluating the same or similar interventions to allow us to do any of our planned subgroup analyses.

Risk of bias in included studies

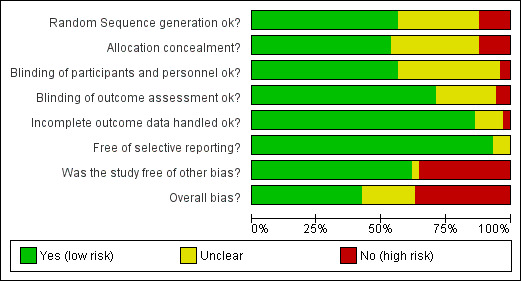

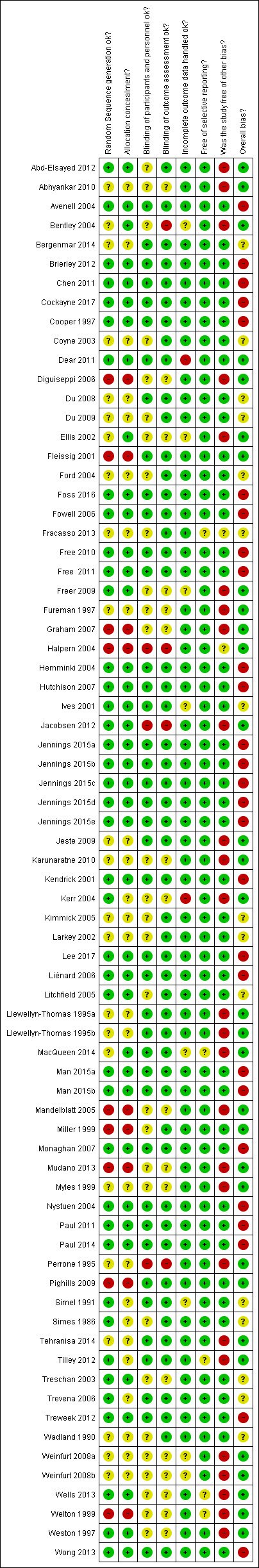

See Characteristics of included studies; Figure 1; Figure 2.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Trialists described all their studies as either randomised (62 studies) or quasi‐randomised (6 studies). We considered the overall assessment of the risk of bias as low for 22 studies, unclear for 14 studies and high for 32 studies.

There were 26 studies involving hypothetical trials, and we judged 24 of these to be at high risk of bias because the participation decision was not a real one (there may also have been other weaknesses). We judged Treschan 2003 to be at unclear risk of bias because although participants were not told the trial was hypothetical initially, it was not clear if this remained the case throughout. Simel 1991 also involved a hypothetical trial, but participants were unaware of this; the use of a hypothetical trial did not therefore affect our risk of bias assessment for this study, and we judged it to be at unclear risk of bias.

Effect of methods

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7

Table 9 shows the list of included studies in each of our seven categories. The divisions between categories were not always clear, and we placed studies according to the original study authors' stated focus.

2. Intervention categories.

| Study | Host trial intervention | Type of participants |

| A–Design. This includes changes to the general design of the trial specifically done to increase recruitment. | ||

| Avenell 2004 | Drug: vitamin D tablet | Patients (adults): attending a fracture clinic or orthopaedic ward |

| Cooper 1997 | Drug/surgery: medical management or transcervical resection of the endometrium | Patients (adults): first‐time attendees at a gynaecological clinic |

| Fowell 2006 | Drug: anti‐emetics only if symptomatic | Patients (adults): cancer inpatients receiving palliative care |

| Hemminki 2004 | Drug: HRT | Patients (adults): postmenopausal women considering HRT |

| Litchfield 2005 | Device: alternative delivery systems (NovoPen and Innovo) for insulin | Patients (probably adults): people with type 1 diabetes |

| Paul 2011 | Drug: adjuvant treatment | Patients (probably adults): with colorectal cancer |

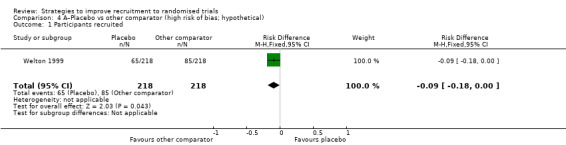

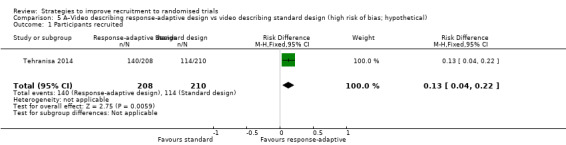

| Tehranisa 2014a | Hypothetical drug: acute stroke trial | Patients (adults): people attending emergency department |

| Welton 1999a | Hypothetical drug: HRT | Healthy volunteers (adults): women who had not had a hysterectomy |

| B–Pre‐trial planning. This includes work done before the trial starts (possibly in a separate study) that explicitly aims to increase recruitment success. | ||

| None | ||

| C–Trial conduct changes. This includes initiatives implemented once the trial has started, such as better ways of identifying participants, changes to how data are collected, changes to the type of data collected and tailored recruitment to different types of participant. | ||

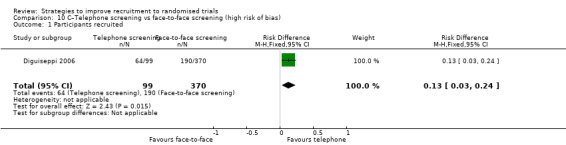

| Diguiseppi 2006a | Hypothetical behavioural trial | Patients (adults): attending hospital with acute injury |

| Free 2010 | Behaviour: mobile phone‐based smoking cessation | Healthy volunteers (adults): smokers |

| Free 2011 | Behaviour: mobile phone‐based smoking cessation | Healthy volunteers (adults): smokers |

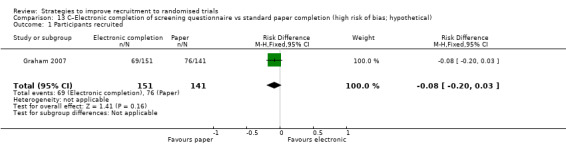

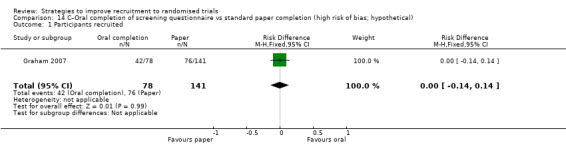

| Graham 2007a | Hypothetical lifestyle trial | Patients (adults): attending hospital with acute injury |

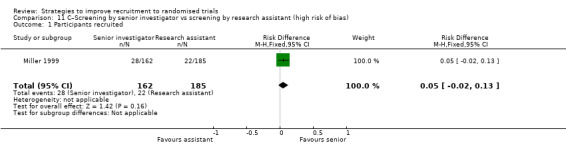

| Miller 1999 | Drug or therapy: psychotherapy, antidepressant medication, or both | Patients (adults): eligible for 1 of the 2 trials being run through the unit: 18‐75 years old and DSM‐IV dysthymic disorder, double depression (major depression superimposed on antecedent dysthymia), or chronic major depression |

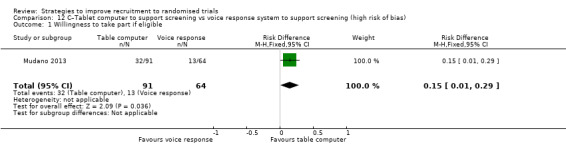

| Mudano 2013 | Hypothetical drug: osteoporosis | Healthy volunteers (adults): women 65 years or over with no reported use of osteoporosis medication in last year |

| Nystuen 2004 | Therapy: psychologist intervention for issues linked to psychological problems or musculoskeletal pain | Patients (adults): on sick leave receiving benefits |

| Treweek 2012 | Drug: antibiotic prescribing | Health professionals (adults): family doctors |

| Wong 2013 | Screening: colorectal cancer screening | Healthy volunteers (adults): eligible for colorectal cancer screening |

| D–Modification to the consent form or process. This includes changes to the staff member helping with consent, when consent is taken, what sort of consent information is presented and how it is presented. | ||

| Abd‐Elsayed 2012 | Drug or blood storage trials | Patients (adults): eligible for 1 of 3 trials, all of whom had substantial illness requiring major surgery (cardiac) |

| Abhyankar 2010a | Hypothetical drug or surgery | Healthy volunteers (adults): women and students on university mailing list |

| Coyne 2003 | Drug: various | Patients (adults): eligible for cancer trial |

| MacQueen 2014a | Hypothetical drug: HIV treatment | Healthy volunteers (adults): sexually active women |

| Myles 1999a | Hypothetical drug: various | Patients (adults): eligible for surgery |

| Perrone 1995a | Hypothetical drug: various | Healthy volunteers (adults): attending a public event |

| Trevena 2006 | Screening: colorectal cancer | Healthy volunteers (adults): eligible for colorectal screening |

| Wadland 1990 | Lifestyle: smoking cessation | Healthy volunteers (adults): smokers |

| E–Modification to the information given to potential participants about the trial. This includes who provides it, when, where what sort of information is presented, how the information is presented. | ||

| Bergenmar 2014 | Drug: various | Patients (probably adults): eligible for cancer trials |

| Brierley 2012 | Therapy: cognitive behavioural therapy | Patients (adults): depression |

| Chen 2011 | Unclear | Patients (probably adults): unclear what type |

| Cockayne 2017 | Device: orthosis | Patients (adults): podiatry |

| Dear 2011 | Information: access to cancer trials site | Patients (adults): have cancer |

| Du 2008 | Cancer trials (unspecified) | Patients (adults): lung cancer |

| Du 2009 | Cancer trials (unspecified) | Patients (adults): women with breast cancer |

| Ellis 2002a | Hypothetical cancer trials (unspecified) | Patients (adults): women with breast cancer |

| Ford 2004 | Screening: prostate, lung and colorectal cancer screening | Healthy volunteers (adults): men eligible for prostate, lung and colorectal cancer screening |

| Foss 2016 | Vaccination | Healthy volunteers (adults): pregnant women |

| Fracasso 2013 | Cancer trials (unspecified) | Patients (adults): cancer (various) |

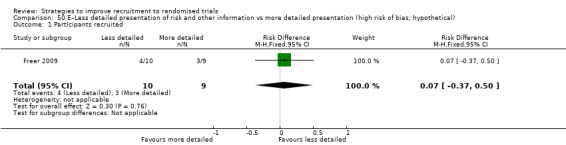

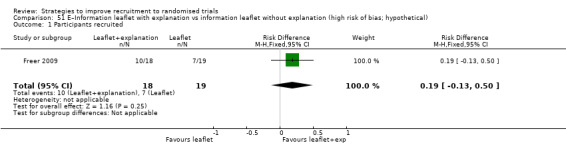

| Freer 2009a | Hypothetical intensive care (unspecified) | Healthy volunteers (adults): parents of infants admitted to hospital |

| Fureman 1997a | Hypothetical vaccine trial: HIV | Healthy volunteers (adults): drug users |

| Hutchison 2007 | Cancer trials (unspecified) | Patients (probably adults): cancer (various) |

| Ives 2001 | Unclear but probably drug | Patients (adults): people with HIV |

| Jacobsen 2012a | Hypothetical cancer trial | Patients (adults): cancer (various) |

| Jeste 2009a | Hypothetical drug trial | Patients (adults): schizophrenia |

| Karunaratne 2010a | Hypothetical device trial | Patients (adults): diabetes |

| Kendrick 2001 | Injury prevention trial | Healthy volunteers (adults and children): families |

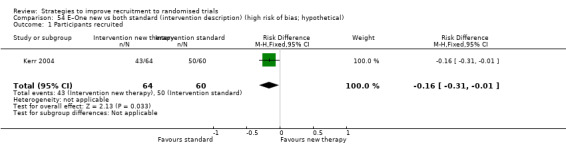

| Kerr 2004a | Hypothetical drug trial | Healthy volunteers (adults): attending college |

| Kimmick 2005 | Cancer trials (various) | Patients (adults): cancer (various) |

| Larkey 2002 | Various targeting cardiovascular disease, cancer and osteoporosis | Healthy volunteers: (adults) women |

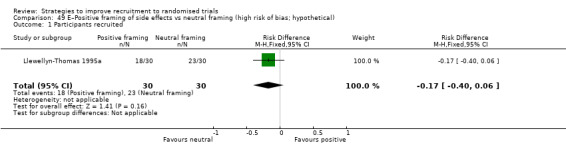

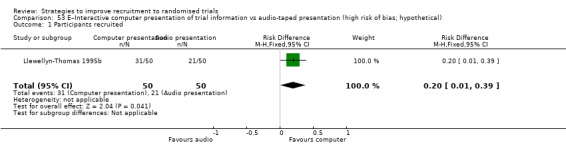

| Llewellyn‐Thomas 1995aa | Hypothetical drug trial | Patients (adults): colorectal cancer |

| Llewellyn‐Thomas 1995ba | Hypothetical drug trial | Patients (adults): cancer |

| Man 2015ab | Therapy: telephone support and self‐management | Patients (adults): cardiovascular |

| Man 2015bb | Therapy: telephone support and self‐management | Patients (adults): cardiovascular |

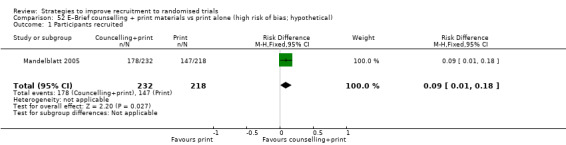

| Mandelblatt 2005a,c | Hypothetical drug trial | Healthy volunteers (adults): cancer prevention |

| Paul 2014 | Screening: colorectal cancer | Healthy volunteers (adults): colorectal cancer screening |

| Pighills 2009 | Therapy: falls prevention | Healthy volunteers (adults): older people at risk of falling |

| Simel 1991a,c | Hypothetical drug trial (participants were not told it was hypothetical) | Patients (adults): people attending ambulatory care clinic |

| Simes 1986 | Unclear: cancer | Patients (adults): cancer |

| Treschan 2003a,c | Hypothetical surgery trial (participants were not told it was hypothetical) | Patients (adults): people undergoing minor surgery with general anaesthetic |

| Weinfurt 2008aa | Hypothetical drug trial | Patients (adults): coronary heart disease |

| Weinfurt 2008ba | Hypothetical drug trial | Patients (adults): coronary heart disease |

| Wells 2013a | Hypothetical: unclear what type, probably drug | Patients (adults): cancer |

| Weston 1997a | Hypothetical surgery trial | Healthy volunteers (adults): women attending antenatal clinics. |

| F–Interventions aimed at the recruiter or recruitment site. This includes anything that is aimed at the recruiter or recruitment site staff rather than the person being recruited such as changes to training | ||

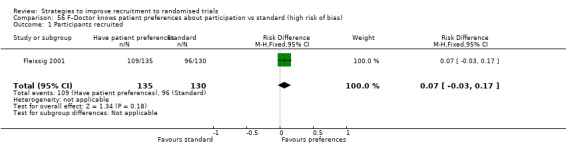

| Fleissig 2001 | Diverse: cancer | Patients (adults): cancer |

| Lee 2017 | Therapy: pain education | Staff at primary care clinics (sites are target, not patients) |

| Liénard 2006 | Drug: breast cancer treatment | Staff at breast cancer treatment centres (sites are target, not patients) |

| Monaghan 2007 | Unclear: diabetes management | Staff at clinical sites recruiting to a diabetes and vascular disease treatment trial (sites are target, not patients) |

| Tilley 2012 | Drug: Parkinson's disease | Neurologists, primary care doctors and internists (adults) |

| G–Incentives. Financial and other incentives for participants | ||

| Bentley 2004a | Hypothetical drug trial | Healthy volunteers (adults): students |

| Free 2010 | Lifestyle: mobile phone‐based smoking cessation | Healthy volunteers (adults): smokers |

| Halpern 2004a,c | Hypothetical drug study | Patients (probably adults): mild hypertension |

| Jennings 2015ad | Drug: NSAID | Patients (adults): arthritis |

| Jennings 2015bd | Drug: hyperuricaemia | Patients (adults): symptomatic hyperuricaemia |

| Jennings 2015cd | Drug: hypertension | Patients (adults): hypertension |

| Jennings 2015dd | Drug: hypertension | Patients (adults): hypertension |

| Jennings 2015ed | Drug: diuretic therapy | Patients (adults): metabolic syndrome |

DSM‐IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; HRT: hormone replacement therapy; NSAID: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs. aStudies were recruiting to hypothetical trials or asking questions about intention to participate rather than asking people to make a real decision about participation. bMan 2015a and Man 2015b are actually a single study that describes 2 embedded recruitment trials. cSimel 1991, Treschan 2003 and Halpern 2004 used hypothetical trials but did not tell participants until after they had made their decisions; Mandelblatt 2005 involved a real trial but asked about intention to take part, not actual taking part. dJennings 2015a, Jennings 2015b, Jennings 2015c, Jennings 2015d and Jennings 2015e are actually a single study that describes 5 embedded recruitment trials.

We report the results of studies rated as being at low or uncertain risk of bias here. The full list of 72 comparisons tested, irrespective of risk of bias, is given in Appendix 4.

We produced 'Summary of findings' tables for all interventions where more than one study done in a real trial was available, giving seven in total (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7).

Design ‐ category A

Eight studies focused on trial design as a way to improve recruitment; we judged two (25%) of these to be at high risk of bias and do not present them here. The remaining six studies involved 5637 participants; one study also targeted general practices and recruited 28 centres.

We summarise the results for the six studies as follows.

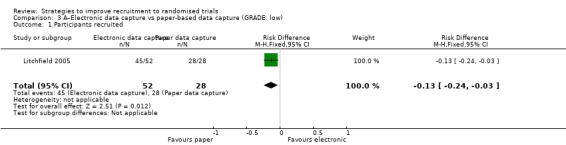

An open design compared to a blinded, placebo‐controlled design increases recruitment: RD = 10% (95% CI 7% to 13%); GRADE: high; Analysis 1.1; Table 1. This is based on two studies: Avenell 2004 (fracture prevention); RoB: low; Hemminki 2004 (postmenopausal hormone therapy) RoB: low.

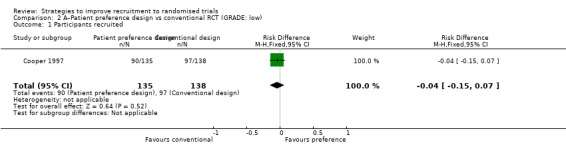

A patient preference design increased total participation but made little or no difference to recruitment to the randomised trial: RD = ‐4% (reduced recruitment) (95% CI ‐15% to 7%); GRADE: low (‐2 levels: imprecision– single study; wide CI crossing RD=0); Analysis 2.1. This is based on one study: Cooper 1997 (management strategies for heavy menstrual bleeding) RoB: low.

Internet‐based, electronic data collection compared to paper‐based may reduce recruitment: RD = ‐13% (reduced recruitment) (95% CI ‐24% to ‐3%); GRADE: low (‐1 level: study limitations–unclear RoB; ‐1 level: imprecision–single study); Analysis 3.1. This is based on one study: Litchfield 2005 (delivery systems for insulin) RoB: unclear.

Cluster‐randomised design compared to Zelen design. The study had only two sites (clusters) with few participants: 6 out of 24 potential participants were recruited in the cluster arm, compared to 0 out of 29 in the Zelen arm; RoB: low. This is based on one study: Fowell 2006 (palliative care) RoB: low.

Two‐stage randomisation to choose duration of treatment. Data on numbers recruited not available for one arm but up‐front randomisation to 3 or 6 months treatment gave a recruitment rate of 5.21 per year per centre compared to 4.09 for delayed randomisation to decide whether second 3 month treatment given. This is based on one study: Paul 2011 (adjuvant treatment for colorectal cancer) RoB: low.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 A–Open trial vs blinded trial (GRADE: high), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 A–Patient preference design vs conventional RCT (GRADE: low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 A–Electronic data capture vs paper‐based data capture (GRADE: low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

Pre‐trial planning ‐ category B

There were no studies in this category.

Trial conduct changes ‐ category C

Nine studies assessed changes in trial conduct to improve recruitment. We judged four (44%) to be at high risk of bias and do not present them here. The remaining five studies involved 4531 participants.

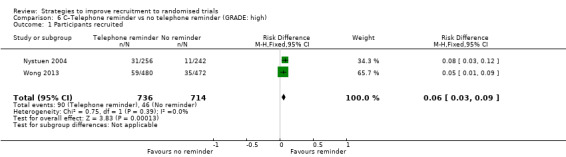

Using a telephone reminder to contact non‐responders to a postal invitation increases recruitment. RD = 6% (95% CI 3% to 9%); GRADE: high; Analysis 6.1; Table 2. This is based on two studies: Nystuen 2004 (getting people to return to work); RoB: low; Wong 2013 (colorectal cancer) RoB: low. NOTE: the evidence for this intervention comes entirely from trials with low (<10%) underlying recruitment. When applied to trials with higher recruitment we would downgrade the GRADE assessment because of Indirectness to moderate.

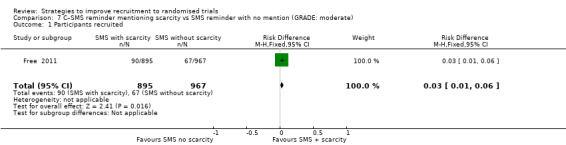

Mentioning scarcity of trial places in SMS messages probably increased recruitment. RD = 3% (95% CI = 1% to 6%); GRADE: moderate (‐1 level: imprecision–single study); Analysis 7.1. This is based on one study: Free 2011 (smoking cessation) RoB: low..

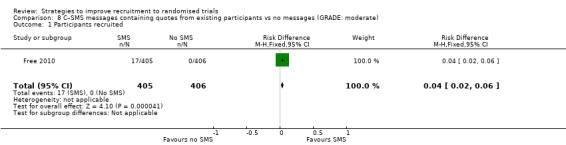

Giving quotes from previous participants in SMS messages probably increased recruitment. RD = 4% (95% CI = 2% to 6%); GRADE: moderate (‐1 level: imprecision–single study); Analysis 8.1. This is based on one study: Free 2010 (smoking cessation) RoB: low.

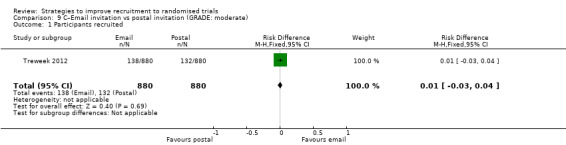

Using email invitations made little or no difference to recruitment compared to postal invitations. RD = 1% (95% CI = ‐3% to 4%); GRADE: moderate (‐1 level: imprecision–single study); Analysis 9.1. This is based on one study: Treweek 2012 (antibiotic prescribing by GPs) RoB: low.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 C–Telephone reminder vs no telephone reminder (GRADE: high), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 C–SMS reminder mentioning scarcity vs SMS reminder with no mention (GRADE: moderate), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 C–SMS messages containing quotes from existing participants vs no messages (GRADE: moderate), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 C–Email invitation vs postal invitation (GRADE: moderate), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

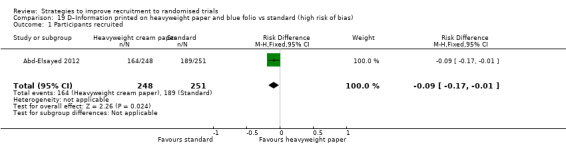

Modification to the consent process ‐ category D

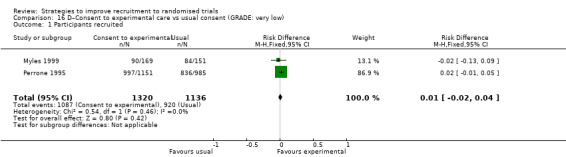

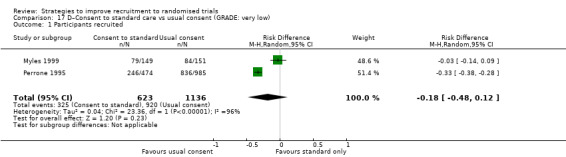

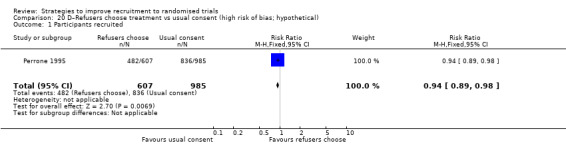

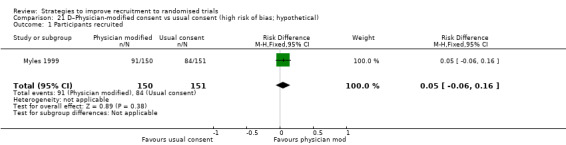

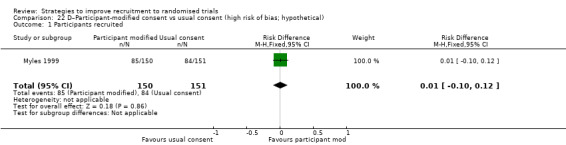

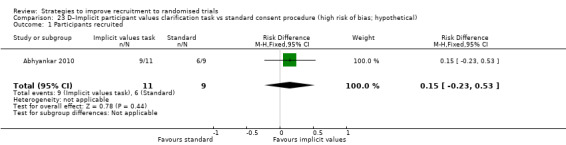

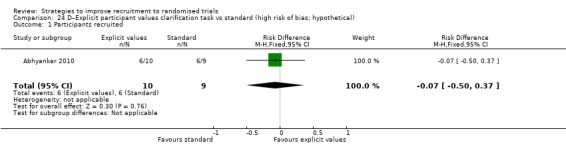

Eight studies assessed the effect of modifying the consent process on trial recruitment. Of the five (63%) we judged to be at high risk of bias, we could have combined two (Myles 1999; Perrone 1995): however, both were hypothetical, and we do not present them here. The three studies presented here involved 482 participants.

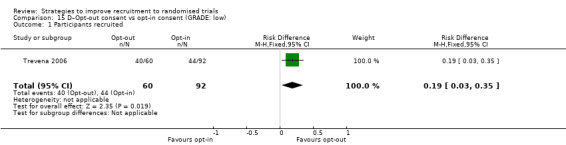

Opt‐out consent may improve recruitment. RD = 19% (95% CI = 3% to 35%); GRADE: low (‐1 level: study limitations–unclear RoB; ‐1 level: imprecision–single study); Analysis 15.1. This is based on one study: Trevena 2006 (colorectal cancer) RoB: unclear.

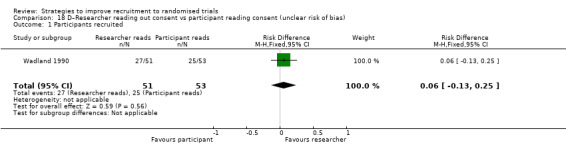

It is very uncertain whether a researcher reading out the consent details affects recruitment. RD = 6% (95% CI = ‐13% to 25%); GRADE: very low (‐1 level: study limitations–unclear RoB; ‐2 levels: imprecision–single study; wide CI crossing RD=0); Analysis 18.1. This is based on one study: Wadland 1990 (smoking cessation) RoB: unclear.

Easy to read consent form. Although the authors of this cluster trial did not present centre‐level recruitment data, or provide an intracluster correlation coefficient, they did consider intracluster correlation in their analysis and found that recruitment did not differ significantly between the two trial groups (RD=3; P = 0.32). This is based on one study: Coyne 2003 (cancer) RoB: unclear.

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 D–Opt‐out consent vs opt‐in consent (GRADE: low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

18.1. Analysis.

Comparison 18 D–Researcher reading out consent vs participant reading consent (unclear risk of bias), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

Modification to the information given to potential participants about the trial ‐ category E

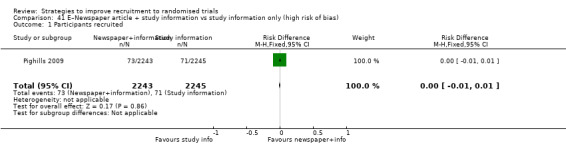

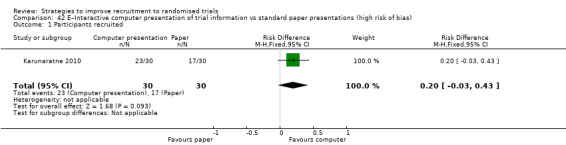

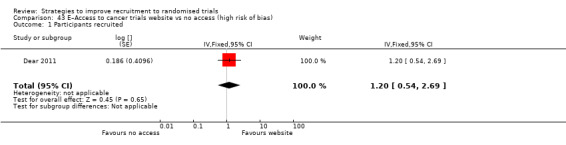

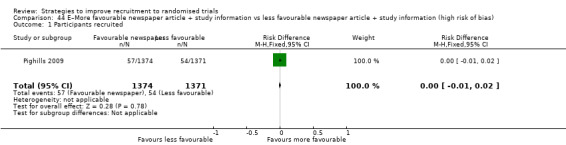

Thirty‐five studies assessed the effects of modifying the information given to potential participants about the trial for trial recruitment. We judged 17 (49%) to be at high risk of bias and do not present them here. The remaining 17 studies involved 42,826 participants.

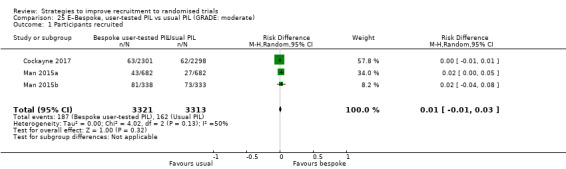

Optimising the participant information leaflet (PIL) through a particular, bespoke process involving formal user‐testing makes little or no difference to recruitment. RD = 1% (95% CI = ‐1% to 3%); GRADE: high; Analysis 25.1; Table 3. This is based on three studies: Man 2015a (depression) RoB: low; Man 2015b (cardiovascular disease) RoB: low; Cockayne 2017 (falls prevention) RoB: low.

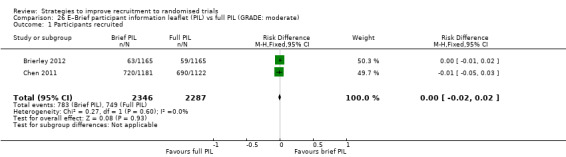

Using a brief patient information leaflet (PIL) makes little or no difference to recruitment compared to a full PIL. RD = 0% (95% CI = ‐2% to 2%); GRADE: moderate (‐1 level: indirectness, Chen 2011 actually measures entry to pre‐randomisation phase); Analysis 26.1; Table 4. This is based on two studies: Chen 2011 (unclear) RoB: low; Brierley 2012 (depression) RoB: low.

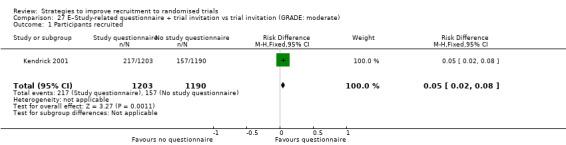

Enclosing a questionnaire covering issues relevant to trial with the invitation probably increases recruitment. RD = 18% (95% CI = 16% to 20%); GRADE: moderate (‐1 level: imprecision–single study); Analysis 27.1 This is based on one study: Kendrick 2001 (injury prevention, recruiting family units) RoB: low.

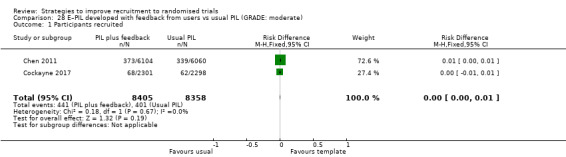

Optimising the PIL through using user feedback probably makes little or no difference in recruitment. RD = 0% (95% CI = 0% to 1%); GRADE: moderate (‐1 level: indirectness, Chen 2011 actually measures entry to pre‐randomisation phase); Analysis 28.1; Table 5 This is based on two studies: Chen 2011 (unclear) RoB: low; Cockayne 2017 (falls prevention) RoB: low.

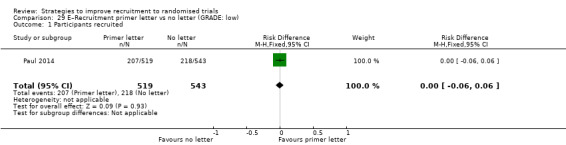

Sending a recruitment primer letter may have little or no effect on recruitment. RD = 0% (95% CI = ‐6% to 6%); GRADE: low (‐2 levels: imprecision–single study; wide CI crossing RD=0); Analysis 29.1 This is based on one study: Paul 2014 (colorectal cancer) RoB: low.

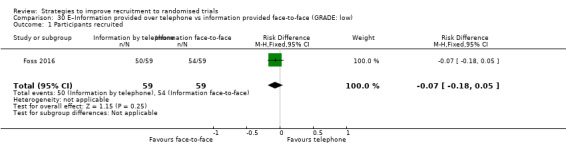

Providing information over the telephone may have little or no effect on recruitment. RD = ‐7% (reduced recruitment) (95% CI = ‐18% to 5%); GRADE: low (‐2 levels: imprecision–single study; wide CI crossing RD=0); Analysis 30.1 This is based on one study: Foss 2016 (vaccination) RoB: low.

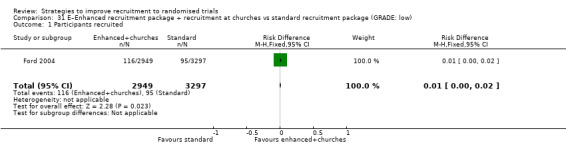

Recruitment at a church and other enhancements may improve recruitment. RD = 1% (95% CI = 0% to 2%); GRADE: low (‐1 level: study limitations–unclear RoB; ‐1 level: imprecision–single study); Analysis 31.1 This is based on one study: Ford 2004 (cancer) RoB: unclear.

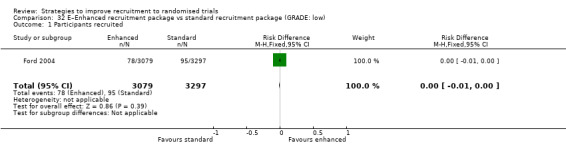

An enhanced recruitment package including more contact may make little or no difference in recruitment. RD = 0% (95% CI = ‐1% to 0%); GRADE: low (‐1 level: study limitations–unclear RoB; ‐1 level: imprecision–single study); Analysis 32.1 This is based on one study: Ford 2004 (cancer) RoB: unclear.

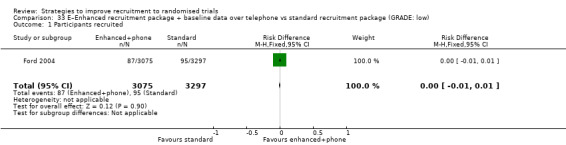

An enhanced recruitment package including more contact by telephone may make little or no difference in recruitment. RD = 0% (95% CI = ‐1% to 1%); GRADE: low (‐1 level: study limitations–unclear RoB; ‐1 level: imprecision–single study); Analysis 33.1 This is based on one study: Ford 2004 (cancer) RoB: unclear.

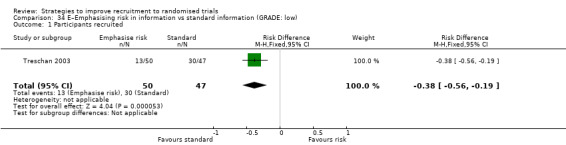

Emphasising risk in information may make little or no difference to recruitment. RD = 0% (95% CI = ‐1% to 1%); GRADE: low (‐1 level: study limitations–unclear RoB; ‐1 level: imprecision–single study); Analysis 34.1 This is based on one study: Treschan 2003 (unclear) RoB: unclear.

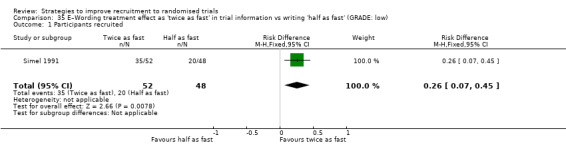

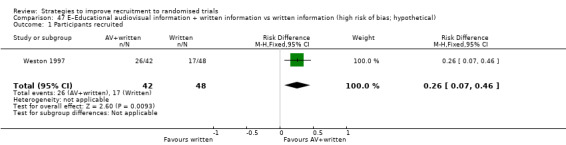

Writing treatment effect as 'twice as fast' rather than 'half as fast' may improve recruitment. RD = 26% (95% CI = 7% to 45%); GRADE: low (‐1 level: study limitations–unclear RoB; ‐1 level: imprecision–single study); Analysis 35.1 This is based on one study: Simel 1991 (pain relief) RoB: unclear.

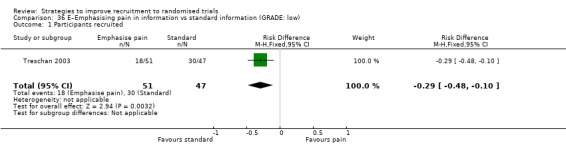

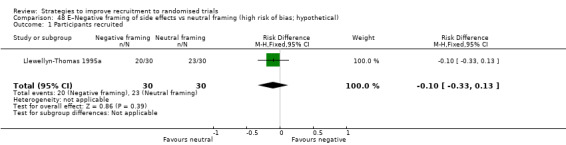

Emphasising pain in information may reduce recruitment. RD = ‐29% (reduced recruitment) (95% CI = ‐48% to ‐10%); GRADE: low (‐1 level: study limitations–unclear RoB; ‐1 level: imprecision–single study); Analysis 36.1 Thsi is based on one study: Treschan 2003 (unclear) RoB: unclear.

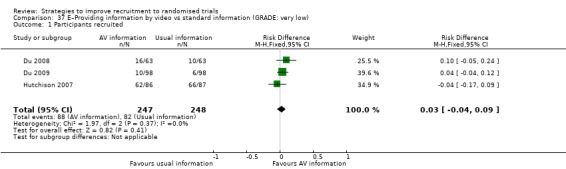

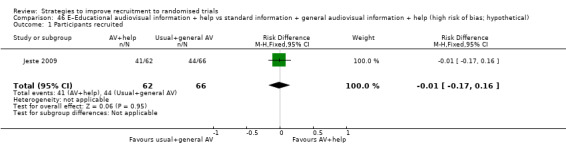

It is very uncertain whether providing trial information by video affects recruitment. RD = 3% (95% CI = ‐3% to 9%); GRADE: very low (‐1 level: study limitations–unclear RoB; ‐1 level: inconsistency; ‐1 level: imprecision–wide CI crossing RD=0); Analysis 37.1; Table 6 This is based on three studies: Hutchison 2007 (cancer) RoB: low; Du 2008 (lung cancer) RoB: unclear; Du 2009 (breast cancer) RoB: unclear.

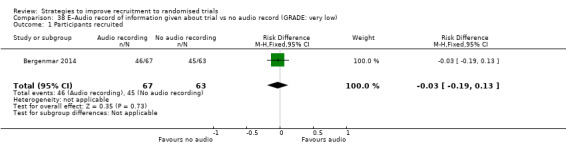

It is very uncertain whether providing an audio record of the discussion about the trial affects recruitment. RD = ‐3% (reduced recruitment) (95% CI = ‐19% to 13%); GRADE: very low (‐1 level: study limitations–unclear RoB; ‐2 levels: imprecision–single study; wide CI crossing RD=0); Analysis 38.1 This is based on one study: Bergenmar 2014 (cancer) RoB: unclear.

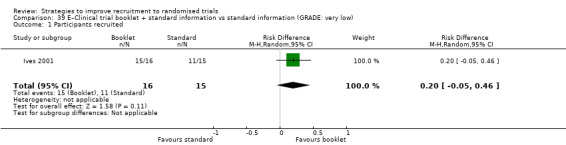

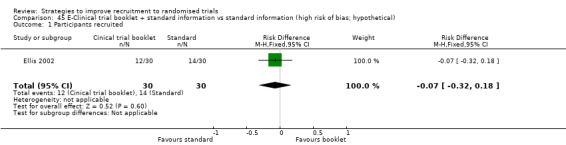

It is very uncertain whether providing a clinical trial booklet together with standard information affects recruitment. RD = 20% (95% CI = ‐5% to 46%); GRADE: very low (‐1 level: study limitations–unclear RoB; ‐2 levels: imprecision–single study; wide CI crossing RD=0); Analysis 39.1 This is based on one study: Ives 2001 (HIV) RoB: unclear.

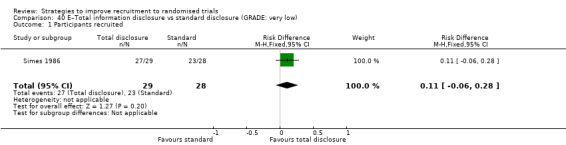

It is very uncertain whether providing total information disclosure rather than leaving it to recruiters as to what to reveal affects recruitment. RD = 11% (95% CI = ‐6% to 28%); GRADE: very low (‐1 level: study limitations–unclear RoB; ‐2 levels: imprecision–single study; wide CI crossing RD=0); Analysis 40.1 This is based on one study: Simes 1986 (cancer) RoB: unclear.

Educational material to provide additional information about a trial. Although the authors of this cluster trial did not present centre‐level recruitment data, or provide an intracluster correlation coefficient, they did consider intracluster correlation in their analysis. An educational package did not significantly increase recruitment compared to standard information alone (31% of participants aged over 65 in both intervention and control groups in year 2, P = 0.83). This is based on one study: Kimmick 2005 (cancer) RoB: unclear.

Trained recruiters from a similar ethnic background to study population already taking part in a trial as lay advocates. The authors of this cluster trial did not report an analysis that corrected for the clustering or provide an intracluster correlation coefficient. Data at the recruiter aggregate level were reported on whether a recruiter did or did not recruit anyone to the trial. Eight of the 28 trained Hispanic recruiters recruited one or more women to the trial whereas none of the 26 untrained Hispanic women recruited anyone the trial. Two of the 42 untrained Anglo control group recruited two women. This is based on one study: Larkey 2002 (unclear) RoB: low.

25.1. Analysis.

Comparison 25 E–Bespoke, user‐tested PIL vs usual PIL (GRADE: moderate), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

26.1. Analysis.

Comparison 26 E–Brief participant information leaflet (PIL) vs full PIL (GRADE: moderate), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

27.1. Analysis.

Comparison 27 E–Study‐related questionnaire + trial invitation vs trial invitation (GRADE: moderate), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

28.1. Analysis.

Comparison 28 E–PIL developed with feedback from users vs usual PIL (GRADE: moderate), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

29.1. Analysis.

Comparison 29 E–Recruitment primer letter vs no letter (GRADE: low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

30.1. Analysis.

Comparison 30 E–Information provided over telephone vs information provided face‐to‐face (GRADE: low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

31.1. Analysis.

Comparison 31 E–Enhanced recruitment package + recruitment at churches vs standard recruitment package (GRADE: low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

32.1. Analysis.

Comparison 32 E–Enhanced recruitment package vs standard recruitment package (GRADE: low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

33.1. Analysis.

Comparison 33 E–Enhanced recruitment package + baseline data over telephone vs standard recruitment package (GRADE: low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

34.1. Analysis.

Comparison 34 E–Emphasising risk in information vs standard information (GRADE: low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

35.1. Analysis.

Comparison 35 E–Wording treatment effect as 'twice as fast' in trial information vs writing 'half as fast' (GRADE: low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

36.1. Analysis.

Comparison 36 E–Emphasising pain in information vs standard information (GRADE: low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

37.1. Analysis.

Comparison 37 E–Providing information by video vs standard information (GRADE: very low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

38.1. Analysis.

Comparison 38 E–Audio record of information given about trial vs no audio record (GRADE: very low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

39.1. Analysis.

Comparison 39 E–Clinical trial booklet + standard information vs standard information (GRADE: very low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

40.1. Analysis.

Comparison 40 E–Total information disclosure vs standard disclosure (GRADE: very low), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

Interventions aimed at the recruiter or recruitment site ‐ category F

Five studies assessed interventions aimed at the recruiter or recruitment site. We judged two (40%) of these to be at high risk of bias and do not present them here. The remaining three studies involved at least 602 participants; it was not clear how many participants were involved in one study, although 167 recruitment sites were involved.

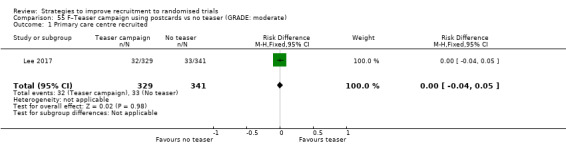

Using a postcard teaser campaign made little or no difference to recruitment. RD = 0% (95% CI = ‐4% to 5%); GRADE: moderate (‐1 level: imprecision–single study); Analysis 55.1 This is based on one study: Lee 2017 (recruiting GP practices to low back pain trial) RoB: low.

Onsite initiation visits. The authors did not present the proportion of eligible participants recruited, only the number recruited: visited sites recruited 302 participants while those not receiving visits recruited 271. This is based on one study: Liénard 2006 (breast cancer) RoB: low.

Additional communication strategies such as tailored feedback on recruitment. The median total number of participants in the additional communication group was 37.5, compared to 37.0 in the standard communication group. Intervention centres achieved half their recruitment targets in 4.4 months, compared to 5.8 months for control centres. This is based on one study: Monaghan 2007 (diabetes) RoB: low.

55.1. Analysis.

Comparison 55 F–Teaser campaign using postcards vs no teaser (GRADE: moderate), Outcome 1 Primary care centre recruited.

Incentives ‐ category G

Four studies assessed incentives for recruitment, but we judged two (50%) to be at high risk of bias and do not present them here. The remaining two studies included one that involved five trials of the same intervention and together both studies involved a total of 1,506 participants.

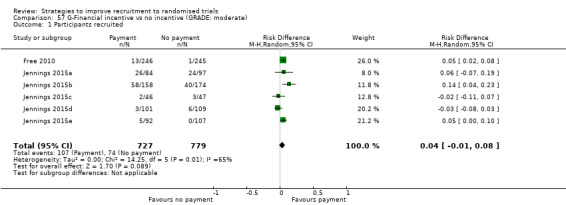

1. Financial incentives offered to potential participants probably improve recruitment. RD = 4% (95% CI = ‐1% to 8%); GRADE: moderate (‐1 level: inconsistency); Analysis 57.1; Table 7 This is based on six studies, one including five trials within a single published study: Free 2010 (smoking cessation) RoB: low; Jennings 2015a; Jennings 2015b; Jennings 2015c; Jennings 2015d; Jennings 2015e (primary care, older people, mainly hypertension) RoB: low.

57.1. Analysis.

Comparison 57 G‐Financial incentive vs no incentive (GRADE: moderate), Outcome 1 Participants recruited.

Discussion

Principal findings

Trialists looking to the literature to select components of an evidence‐informed trial recruitment strategy will be disappointed to find that the literature has plenty of variety but little depth, and therefore much uncertainty. There are three findings that carry a GRADE high certainty of the evidence.

An open design compared to a blinded, placebo‐controlled design increases recruitment (RD 10%, 95% CI 7% to 13%; Analysis 1.1; Table 1; intervention category A).

Using a telephone reminder to contact non‐responders to a postal invitation increases recruitment (RD 6%, 95% CI 3% to 9%; Analysis 6.1; Table 2); intervention category C; see note below).

Optimising the participant information leaflet (PIL) through bespoke development plus formal user‐testing makes little or no difference to recruitment (RD 1%, 95% CI −1% to 3%; Analysis 25.1; Table 3; intervention category E).

Findings 2 and 3 could in principle be considered for many trials. Finding 1 is unlikely to be widely attractive because of the internal validity problem that open trial designs present. Moreover, the evidence for finding 2 comes entirely from trials with low (< 10%) underlying recruitment. When seeking to apply this to trials with higher recruitment, we would downgrade the GRADE assessment to moderate certainty due to indirectness.

There are eight findings that carry a moderate GRADE certainty of the evidence, mostly from single, well‐conducted studies (three in intervention category C, three in category E, one in category F and one in Category G). We rated the GRADE certainty of the evidence for all other findings as low or very low, or as being at high risk of bias if insufficient data were available to do a GRADE assessment. There are no evaluations of an intervention used pre‐trial to support recruitment (category B) and no evaluations of a consent‐related intervention (category D) with a GRADE certainty of the evidence better than low.

Of the 68 included studies, none addresses recruitment to paediatric trials (see Table 9), meaning trialists lack any evidence to inform decisions around participation in these trials. Therefore, identifying effective interventions to support recruitment to paediatric trials is also a priority. Researchers may be wary of adding research methods evaluations to paediatric trials because of, among other challenges, additional ethical requirements. However, because the challenges of recruitment to paediatric trials are likely to be different from those of other trials, extrapolating from trials in adults is unlikely to be sufficient. Moreover, one of the key ethical requirements for research with children – that it is not possible to do the work with adults – is met. For some trials it is likely that the target of the recruitment intervention will be parents rather than children despite being a paediatric trial, so the ethical requirements may in fact be similar to those for trials in adults. Finally, recruitment to paediatric trials will remain less efficient than it could be without work evaluating alternative approaches to recruitment.

While new studies were added to the review, the overall picture with regard to interventions to improve recruitment to trials remains similar to our 2010 version (Treweek 2010), which was in turn largely unchanged from the 2007 version before it (Mapstone 2007). In other words, a decade of research into the effect of interventions to improve trial recruitment has not substantively reduced our uncertainty with regards to which interventions make recruitment more likely. The chief reasons for this are a preference for methodology researchers to evaluate new interventions rather than to replicate evaluations of existing interventions. Poor reporting also leads to uncertain risk of bias assessments.

There is some good news, though. While the intervention type of the studies added to this update is the same as in the 2010 update (Category E, modification to the information given to participants dominates both updates), the methodological quality of studies seems to be improving. Of the 18 studies new to the 2010 update, 12 were at high risk of bias (66%), compared to 11 out of 24 (46%) added in 2017. We judged all 5 of the included studies published in the last three years (2015 to 2017) and all 10 of the recruitment evaluations they describe, to be at low risk of bias (Cockayne 2017; Foss 2016; Jennings 2015a; Jennings 2015b; Jennings 2015c; Jennings 2015d; Jennings 2015e; Lee 2017; Man 2015a; Man 2015b). Equally important, initiatives such as START (research.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/mrcstart) are leading to coordinated evaluation of recruitment interventions in many trials, participant information leaflets and video information in the case of START. The three studies in the bespoke, user‐tested participant information leaflet analysis (Analysis 25.1; Table 3) came via START over a three‐year period (2015 to 2017). By contrast, the two studies in the telephone reminder analysis (Analysis 6.1; Table 2) are nine years apart (2004 to 2013). START will provide more studies for the next update of this review. Timely reduction in uncertainty around interventions needs focus, coordination and replication.

Nevertheless, we judged around half of the 68 included studies to be at high risk of bias, meaning that we have so little confidence in their findings that we chose to neither present nor discuss their results. We will continue to make this choice in future versions of this review. Encouragingly, more recent studies are better reported and much more likely to be judged to be at low risk of bias. A recent reporting standard for embedded recruitment studies may improve things further (Madurasinghe 2016).

We will exclude 24 hypothetical studies from future versions of this review because their findings are not based on real decisions and provide only indirect evidence. It is clearly possible to do studies in real trials, and these will be our focus inthe future.

Finally, we would welcome feedback about studies that we have missed or newly published studies that we should include in future versions of the review.

Authors' conclusions

Implication for methodological research.

The methodological literature with regard to recruitment needs more depth. The current approach of uncoordinated evaluation has led to the usable information content of this review remaining largely unchanged for more than a decade despite the addition of 41 studies. The implications for methodological research are clear.

The research community should establish a process for prioritising which recruitment interventions are most in need of evaluation. While an ongoing, formal process is developed, we suggest that trialists focus on the evaluations highlighted below and the comparisons in this review with moderate‐certainty evidence, especially where there is still only a single study. The PRioRiTy project, which ran a James Lind Alliance prioritisation process for recruitment methods research, is due to publish in 2018 and will provide an excellent list of prioritised areas in need of recruitment intervention work.

The development and evaluation of recruitment interventions for use in paediatric trials is a priority.

We need much more replication and perhaps a little less innovation. This review of 72 comparisons has a total of only seven meta‐analyses. The remainder of the comparisons are single study evaluations of a new intervention.

Trialists evaluating recruitment interventions should do so through Studies Within A Trial (SWATs), using a registered protocol for replication or developing one for new evaluations (Clarke 2015). The SWAT Repository (go.qub.ac.uk/SWAT‐SWAR) supports this at no cost.