Abstract

Objective

To investigate in a cross-sectional study the contributions of altered cerebellar resting-state functional connectivity (FC) to cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease (PD).

Methods

We conducted morphometric and resting-state FC-MRI analyses contrasting 81 participants with PD and 43 age-matched healthy controls using rigorous quality assurance measures. To investigate the relationship of cerebellar FC to cognitive status, we compared participants with PD without cognitive impairment (Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR] scale score 0, n = 47) to participants with PD with impaired cognition (CDR score ≥0.5, n = 34). Comprehensive measures of cognition across the 5 cognitive domains were assessed for behavioral correlations.

Results

The participants with PD had significantly weaker FC between the vermis and peristriate visual association cortex compared to controls, and the strength of this FC correlated with visuospatial function and global cognition. In contrast, weaker FC between the vermis and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex was found in the cognitively impaired PD group compared to participants with PD without cognitive impairment. This effect correlated with deficits in attention, executive functions, and global cognition. No group differences in cerebellar lobular volumes or regional cortical thickness of the significant cortical clusters were observed.

Conclusion

These results demonstrate a correlation between cerebellar vermal FC and cognitive impairment in PD. The absence of significant atrophy in cerebellum or relevant cortical areas suggests that this could be related to local pathophysiology such as neurotransmitter dysfunction.

Dementia affects as many as 80% of patients with Parkinson disease (PD).1 Cognitive impairment can affect most cognitive domains early in the disease process.2 Dementia is refractory to dopaminergic therapy, suggesting involvement of other neurotransmitter systems or brain regions beyond the nigrostriatal pathway. Visuospatial dysfunction predicts progression to dementia and may be linked to cholinergic perturbation.3–5 Most neuroimaging studies of PD have focused on striatal dopaminergic circuitry, which does not fully explain cognitive impairment.

The cerebellum has reciprocal anatomic and functional connections with motor and association cortex.6–8 The vermis harbors a rich population of cholinergic neurons; its malfunction could contribute to cognitive impairments. This notion is supported by [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose PET data showing that vermal hypermetabolism predicted poor cognitive performance.9 To further investigate cerebellar dysfunction in PD, we used resting-state functional connectivity (FC) MRI to study relationships between cerebellum and cortical regions.

Previous studies revealed modest dysfunction in cerebellocortical FC in PD and only limited behavioral correlates.10–13 Significantly increased FC between right lobule V and precuneus in PD correlated with worse cognition.10 Thus, the cognitive correlates of altered cerebellar FC in PD, especially within specific cognitive domains remain uncertain.

We hypothesized that altered cerebellar circuitry contributes to cognitive dysfunction in PD. We investigated this possibility by conducting FC-MRI analyses in a large cohort of PD and age-matched controls. We report cerebellar FC differences contrasting participants with PD and controls as well as participants with PD with and without cognitive impairment. We focus on the relationships between cerebellar FC and comprehensive cognitive measures.

Methods

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and participant consents

The study was approved by the Washington University in St. Louis Human Research Protection Office, and written informed consent was provided by all participants.

Participants

Participants with clinically definite idiopathic PD (based on modified United Kingdom PD Brain Bank criteria excluding the dementia exclusionary criterion)14 and age-matched controls were recruited from the Movement Disorders Center at the Washington University School of Medicine and the community. All controls had a normal neurologic examination without clinical evidence of parkinsonism or cognitive impairment and did not have a family history of PD. Structural and fMRI data were acquired from 153 participants with PD in the “off” state and from 60 controls.

Clinical and neuropsychological assessment

The Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) motor subscale (UPDRS-III) videos were rated by blinded fellowship-trained movement disorder specialists. The truncated UPDRS-III subscale score (excluding rigidity) in the “off” state was used for all statistical analyses. Independent studies demonstrate the reliability and validity of this method.15,16 In addition, gait/postural stability subscore (by adding these 2 individual scores from the UPDRS-III score) was also used for behavioral correlations. Comprehensive neuropsychological assessments, including tests of memory, language, attention, visual-spatial processing, and executive function, were implemented17; appendix e-1 (doi.org/10.5061/dryad.92b0gq1) provides details. The neuropsychological assessment was not available for 1 participant with PD. Individual cognitive domain average z scores and a composite cognitive z score (averaged across the 5 individual cognitive domains) were computed.17 Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in PD was assessed in participants with PD according to the Movement Disorder Society (MDS) Task Force proposed criteria.18 The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score was obtained as a surrogate global cognitive measure.19 Severity of dementia was staged by certified raters according to the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale using the global weighted average.20 A CDR score of 0 is considered cognitively normal, whereas score of ≥0.5 reflects increasing degrees of cognitive impairment.

Neuroimaging data acquisition

MRI was acquired on a 3T Siemens Trio scanner (Siemens, Munich, Germany) with a standard 12-channel head coil using identical sequence parameters as previously described.17,21 MRI scans in participants with PD were obtained in the “off” state after overnight withdrawal of antiparkinsonian medications. Each participant contributed up to 3 resting-state fMRI runs (200 volumes per run). All participants were instructed to keep their eyes closed but to stay awake during fMRI acquisition; the importance of wakefulness was reiterated before each fMRI run and verbally confirmed at its completion.

Structural MRI preprocessing and volumetric analysis

Automatic segmentation of anatomic scans were done with the FreeSurfer image analysis suite (version 5.3, surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). The outputs were visually inspected, and manual edits and reprocessing were performed as needed. Cerebellar segmentation was achieved in an unbiased way with the SUIT toolbox.22 The processing stream was optimized to account for the age-related atrophy in our older participants.23 This substantially improved automatic segmentation (data available from Dryad, figure e-1, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.92b0gq1), and all outputs were inspected for accuracy. The FreeSurfer and/or SUIT segmentation outputs from 12 participants with PD and 5 controls were judged to be inaccurate and excluded from further analysis. The SUIT atlas combines lobules I, II, III, and IV; hence, lobules I through IV were investigated as a single region. The anatomic subdivisions of the cerebellar vermis were combined given their small individual sizes, and the whole vermis was used for all subsequent analyses. Segmentation of lobule X remained inconsistent despite the above modifications; hence, this region was not considered for further analyses. The SUIT toolbox also was used to reslice the atlas to permit extraction of individual lobular volumes (bilateral IIV, V, VI; Crus I, II, VIIb, VIIIa, IX; and vermis); this was normalized for head size from the estimated total intracranial volume, obtained from FreeSurfer. Any lobule with normalized volume 2.5 SDs greater or less than the mean normalized volume for that lobule was considered an outlier (<1%) and excluded from further analysis. The regional thickness of significant cortical clusters reported here was extracted by mapping these on the FreeSurfer FSaverage surface using an affine transform; this was normalized by individual global mean cortical thickness.

Preprocessing of FC-MRI

FC-MRI preprocessing was done as previously described.21 To minimize registration bias, a study-specific atlas-representative template was generated with an equal number of participants with PD and controls. FC preprocessing steps included spatial smoothing (6-mm full width at half-maximum), temporal low-pass filtering (<0.1 Hz), and nuisance regression of 9 waveforms: 6 rigid body head motion estimates obtained by rigid body head motion correction, mean CSF, and white matter signal averaged from respective regions of interests and global signal regression.24,25 DVARS (D referring to temporal derivative of timecourses, VARS referring to RMS variance of voxels; a measure of the rate of change of blood oxygen level–dependent signal across the entire brain at each frame of data)24 was used for censoring of highly artifact-contaminated volumes.

Quality assurance

Stringent quality assurance (QA) measures were enforced to minimize data corruption from head motion at the individual and group levels. For each participant, the root-mean-squared (RMS) head motion (in millimeters) as estimated from a series of rigid body transforms and the voxel-wise time series SD averaged over the whole brain after preprocessing were evaluated. QA-based exclusion criteria were set a priori as described previously.21,25 fMRI runs with RMS head motion >0.6 mm and whole-brain mean fMRI signal SD >0.5% were excluded. In addition, temporal censoring with a DVARS >0.5% was used for scrubbing of motion contaminated volumes, and runs requiring exclusion of >15% volumes were excluded. Any participant with RMS head motion or voxel-wise time series SD 2.5 standard deviations above the global average across groups was considered an outlier and excluded. Only participants with at least 2 usable fMRI runs were included for further analysis. Applying these rigorous QA criteria led to the exclusion of 26% of the participants (46 of 153 with PD and 10 of 60 controls); ultimately 81 participants with PD and 43 controls met the predefined stringent QA standards. Indices of fMRI data quality measures did not significantly differ across groups in the retained data (data available from Dryad, figure e-2, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.92b0gq1).

Correlation mapping and cerebellar FC

The time series from each cerebellar seed region of interest was extracted by averaging over all included voxels, and this was correlated with all the other brain voxels. Correlation maps were computed with the Pearson product moment formula as described, and Fisher z transform was applied.25,26 Group-averaged Fisher z-transformed correlation [z(r)] maps were compared by use of random-effects analysis. Significant clusters, based on extent and z-score thresholds, were computed after permutation resampling by bootstrapped Monte Carlo simulations (10,000 iterations) at p = 0.05 to rigorously correct for multiple comparisons across all brain voxels.25 The FC measures in significant seed-cluster pairs were extracted for additional statistical analyses.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (version 25, IBM Analytics, Armonk, NY). Exploratory univariate 1-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) of normalized lobular volumes was performed with appropriate covariates (covariates for individual analysis are detailed in the Results section). Bonferroni correction was used to correct for multiple comparisons in these volumetric analyses.

Univariate 1-way ANCOVA analysis using the Fisher z(r) correlation coefficients for seed:significant cortical cluster pairs was also done to control for potentially confounding variables, including sex mismatch between groups in the FC-MRI analyses.

Third-order Pearson partial correlations, while controlling for multiple confounders (detailed in Results) were used to investigate the association of the seed:significant cluster correlation coefficients with cognition (including individual cognitive domain z scores and composite cognitive z scores), Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons was applied. Spearman correlations were used for the UPDRS-III rank-order nonparametric measures. All tests were 2 tailed, and values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant unless specified otherwise.

Data availability

Anonymized data will be shared on request by any qualified investigator.

Results

Demographic variables

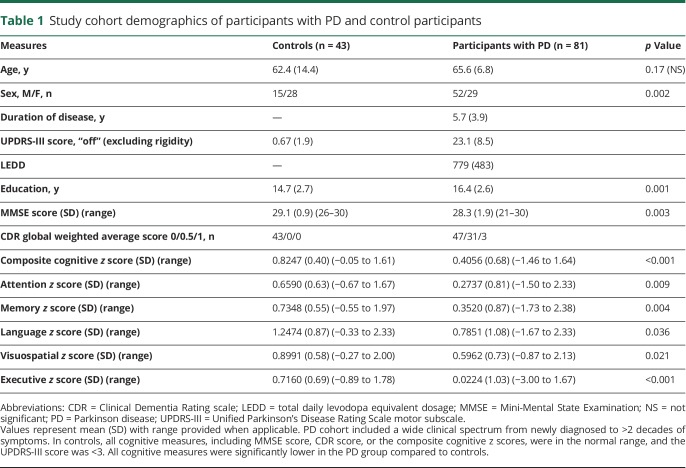

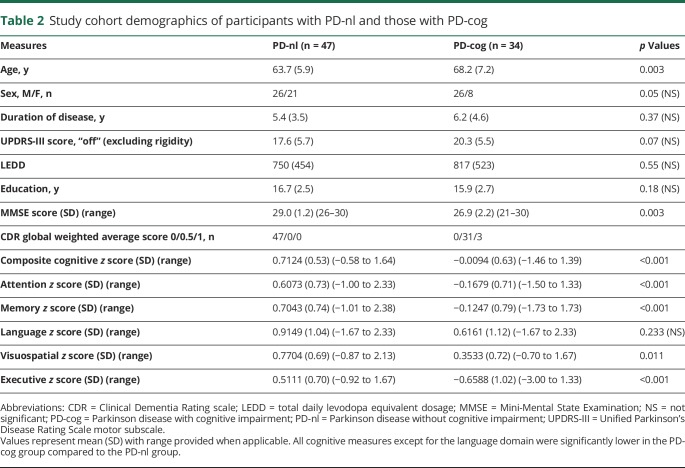

Imaging from 81 participants with PD and 43 controls satisfied the aforementioned stringent quality control measures; table 1 lists the demographic details. Although the groups were age matched, significant differences were noted in the proportion of male participants and the slightly higher education levels in the PD cohort. Thus, sex and education were factored as covariates whenever appropriate. Regarding stratification by cognitive status, only 15 participants with PD met the MDS criteria for PD-MCI using a cutoff score of 1.5 SD below the normative mean as evidence of impairment18; a more inclusive criterion of 1.0 SD yielded 24 participants meeting PD-MCI criteria. In contrast, 34 participants with PD had cognitive impairment based on CDR score (≥0.5). Hence, the CDR score provided a more sensitive measure of cognitive impairment in this study of a relatively mildly affected PD cohort. Thus, participants with PD were categorized into 2 subgroups: PD with cognitive impairment (PD-cog; CDR score ≥0.5) and PD without impairment (PD-nl; CDR score 0). Only 3 participants had dementia (CDR score 1), and the vast majority (31 of 34) were only mildly affected (CDR score 0.5).

Table 1.

Study cohort demographics of participants with PD and control participants

The PD-cog group was slightly older and had lower cognitive scores (table 2).

Table 2.

Study cohort demographics of participants with PD-nl and those with PD-cog

Cerebellar morphometry

To investigate group differences in normalized volumes of individual cerebellar lobules, including the vermis, univariate ANCOVA for each lobule using a Bonferroni-adjusted significance threshold of α < 0.002 was performed. No significant group difference in volumes of any lobules was noted on the basis of either disease (control vs PD; covariates: age, sex; all p > 0.12) or cognitive status (PD-nl vs PD-cog; covariates: age, sex, duration of symptoms; all p > 0.11).

Cerebellar FC in PD

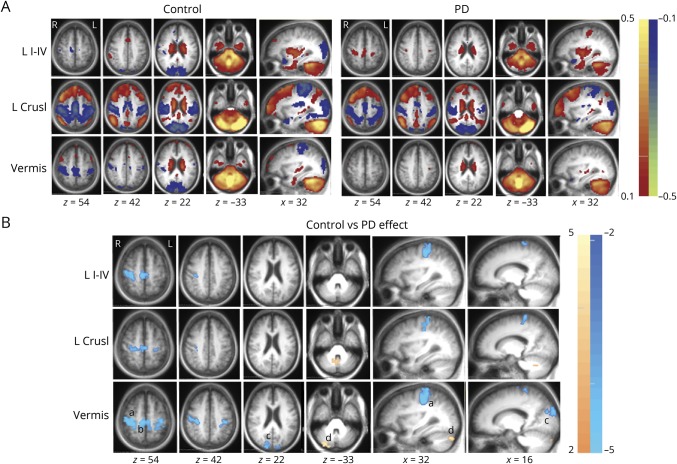

Group contrasts were analyzed on the basis of disease status (PD vs controls) with SUIT-derived individual anatomic cerebellar lobules, including the entire vermis as seeds. Group averages and clusters of contiguous voxels satisfying the previously delineated rigorous statistical criteria are shown in figure 1. Cerebellar FC to association cortex in PD differed significantly from that in controls only with the vermis seed region; none of the other cerebellar lobules had altered FC with association cortex (data available from Dryad, figure e-3, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.92b0gq1). The vermis in participants with PD had weaker anticorrelations (closer to 0) with the peristriate occipital cortex (visual association cortex, Brodmann area [BA] 19) (figure 2A). Significant group differences in intracerebellar FC were present only between the vermis and right Crus I or bilateral Crus II. All significant group clusters mentioned were reported at t ≥ 3.5 and p < 0.001.

Figure 1. Cerebellar FC differences based on disease status.

(A) Cerebellar resting-state functional connectivity (FC) [z(r) maps] averaged over participants in the control (left) and Parkinson disease (PD) (right) groups. Each row corresponds to a distinct cerebellar lobular seed region of interest. Warm and cool colors represent positive and negative correlations. The underlying image is the study-specific atlas template. The Talairach atlas plane of section is indicated under each column; z and x correspond to the axial and sagittal sections, respectively. (B) Random-effects analysis contrasting the control and PD groups. Mapped quantity is the gaussianized t statistic (z score) thresholded at |z| > 3.5. All clusters are significant at the p ≤ 0.05 level. Warm colors indicate more positive correlations in the control group. Cool colors indicate more negative correlations in the control group. Significant clusters of altered vermal FC in PD reported here include the right peristriate occipital cortex (BA19, cluster size 142, Talairach coordinates x = 16, y = −88, and z = 24), right sensorimotor cortex (Brodmann area [BA] 4, 3, 1, 2, cluster size 493, Talairach coordinates x = 37, y = −27, and z = 51). a = sensorimotor cortex; b = supplementary motor area; c = peristriate visual association cortex (BA 19); d = right Crus I and Crus II; L CrusI = left Crus I lobule seed region; L I-IV = left lobules I through IV seed region.

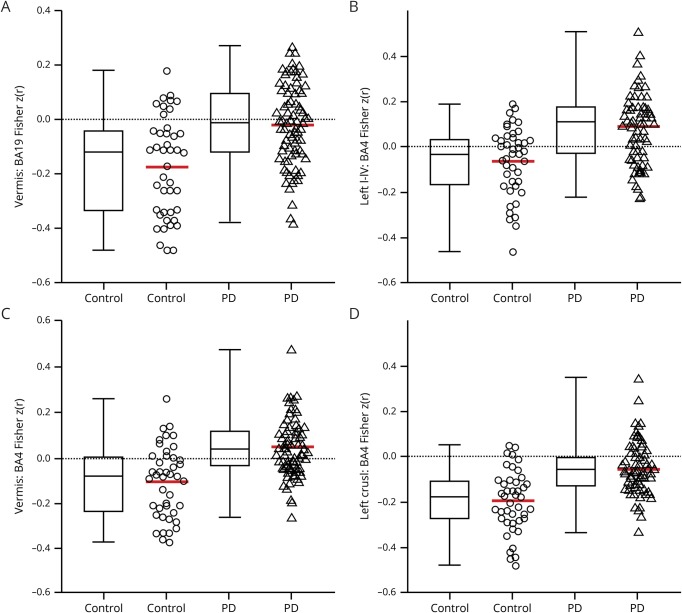

Figure 2. Boxplots and scatterplots contrasting FC of significant cortical clusters based on disease status.

Boxplots (with median value and interquartile range) and scatterplots with mean value (red) demonstrate the significant differences of mean Fisher z(r) correlation coefficients between control and Parkinson disease (PD) groups. (A) Significantly weaker anticorrelations (closer to 0) in vermis:Brodmann area [BA]19 resting-state functional connectivity (FC) in PD (triangles) cohort compared to controls (circles). Cerebellar FC to sensorimotor cortex (BA4) (B–D) ranged from modestly stronger (more positive) correlations with (B) left lobules I-IV:BA4 to weaker (closer to 0) correlations in (C) vermis:BA4 and (D) left Crus I:BA4 FC in PD (triangles) group compared to controls (circles).

Cerebellar FC abnormalities in association cortex were restricted to the vermis. In contrast, multiple cerebellar seeds showed significant FC abnormalities in the primary sensorimotor cortex (BA 3, 2, 1, and 4) and supplementary motor area (BA6) (figure 2, B–D and data available from Dryad (figure e-3, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.92b0gq1). These effects ranged from modestly stronger positive correlations in cerebellar lobules (bilateral lobules I–IV, V, and VI) having direct anatomic connections with sensorimotor cortex (SMC) to weaker (closer to 0) in those without dense interconnections (bilateral lobules Crus I and Crus II). Cortical FC in lobules VIIb and VIIIa in PD was not significantly different.

To check whether local cortical atrophy was responsible for significant FC differences, normalized local cortical thickness for each of the significant clusters (including BA19, BA4) was extracted. No differences in thickness between participants with PD and controls were observed for any of these cortical areas (all p > 0.16).

To investigate whether the sex mismatch between PD and controls in our study drove the group differences, mean Fisher z(r) correlation coefficients were averaged over significant clusters, and univariate ANCOVA was performed while controlling for age, sex, respective lobular volumes, and local cortical thickness. The group differences were robust for all tested seed:cluster pairs (ANCOVA; F1,121 range 24.37–34.84, all p < 0.000002). The role of sex mismatch also was evaluated by matching the female-male distribution in controls to 29 female participants with PD and adding randomly selected 15 male participants with PD. Univariate ANCOVA controlling for age, local cortical thickness, and lobular volume confirmed the observed differences also in these sex-matched groups (ANCOVA; F1,82 range 19.63–25.73, all p < 0.00004).

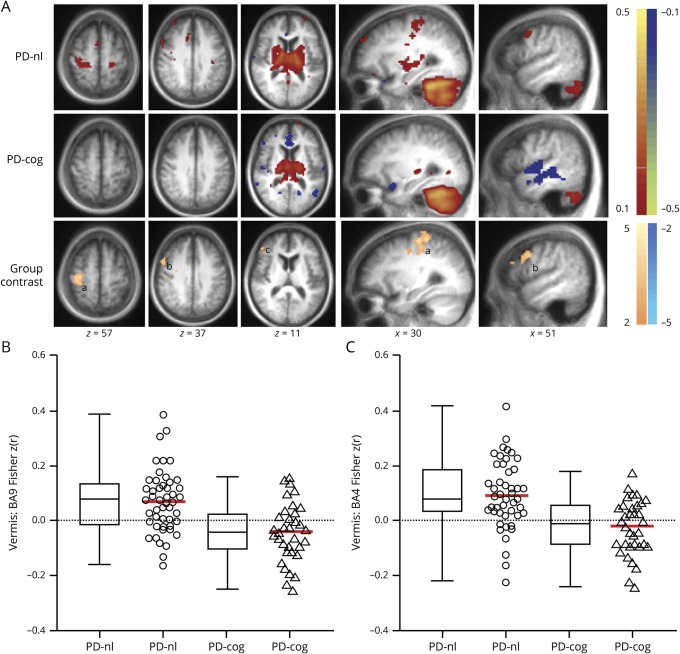

Cerebellar FC in PD-cog

The vermis was the only cerebellar region with significantly altered cortical FC in participants with PD-cog; no other cerebellar lobules yielded any significant clusters based on cognitive status (PD-nl vs PD-cog). Significant clusters of contiguous voxels are reported at t ≥ 2.7 and p ≤ 0.01 (figure 3). Weaker FC of the vermis (less positive correlations closer to 0) was observed with right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC; BA9 and BA46) and SMC (BA4) in the PD-cog subgroup (figure 3, B and C). Corresponding group differences in normalized local cortical thickness were not found (all p > 0.73).

Figure 3. Cerebellar FC differences based on cognitive status.

(A) Cerebellar resting-state functional connectivity (FC) [z(r) maps] with vermis seed region averaged over participants in the Parkinson disease (PD) group without cognitive impairment (PD-nl, top row) and PD with impaired cognition (PD-cog, middle row). Warm and cool colors represent positive and negative correlations. Random-effects analysis contrasting PD-nl and PD-cog groups (bottom row). Mapped quantity is the gaussianized t statistic (z score) thresholded at |z| > 2.6. All clusters are significant at the p ≤ 0.05 level. Warm colors indicate more positive correlations in the PD-nl group. Significant clusters reported here include right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Brodmann area [BA] 9,46, cluster size 120, Talairach coordinates x = 49, y = 10, and z = 33) and right sensorimotor cortex (BA4, 3, 1, 2, cluster size 219, Talairach coordinates x = 35, y = −22, and z = 51). (B and C) Boxplots (with median value and interquartile range) and scatterplots with mean value (red) demonstrate the significantly weaker (less positive) (B) vermis:dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (BA9) FC and (C) vermis:sensorimotor cortex (BA4) FC in the PD-cog (triangles) group compared to the PD-nl (circles) cohort. a = sensorimotor cortex; b = right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, BA9; c = right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, BA46.

FC differences in relation to cognitive status were less robust compared to the contrast based on disease status. Hence, to further investigate whether confounding variables drove the group differences, we extracted Fisher z(r) correlation coefficients from significant clusters and performed univariate ANCOVA while controlling for covariates including age, sex, duration of symptoms, disease severity as reflected by total “off” UPDRS-III scores, local cortical thickness, and volume of vermis. After adjustment for these covariates, the PD-cog group still had significantly lower FC of the vermis with right DLPFC (ANCOVA; F1,77 = 9.36, p = 0.003, partial η2 = 0.12), as well as the SMC (ANCOVA; F1,77 = 19.12, p = 0.00004, partial η2 = 0.22).

Behavioral correlations of cerebellar FC in PD

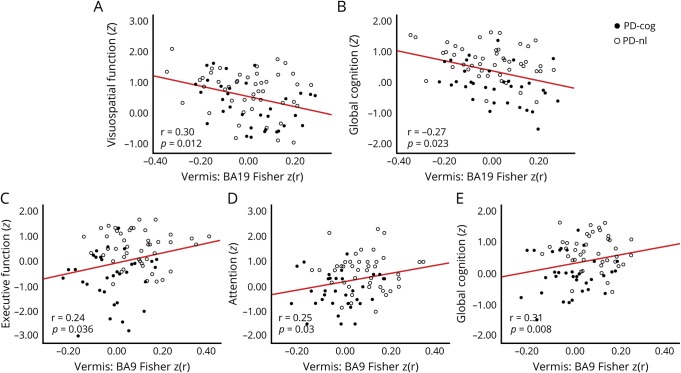

Behavioral correlates of the FC findings in PD were investigated for all reported seed:significant cortical cluster pairs. The UPDRS-III score or its gait/postural stability subscore did not correlate with FC in any cerebellar-sensorimotor cluster, including vermis:BA4 (all p > 0.2). In contrast, vermal FC with the right BA19 cluster correlated with visuospatial domain z scores (r = −0.30, df = 69, p = 0.012) and composite cognitive z score (r = −0.27, df = 70, p = 0.023) after controlling for age, education, duration of symptoms, UPDRS-III score, local cortical thickness, and volume of vermis. Participants with PD with weaker vermal FC had lower cognitive scores (figure 4, A and B). Vermal FC with left BA19 correlated only with the composite cognitive z score (r = −0.25, df = 71, p = 0.035). Vermis:BA19 FC did not correlate with motor UPDRS-III score (p = 0.59). No motor or cognitive correlate was found for lower vermis:left Crus I intracerebellar FC.

Figure 4. Behavioral correlation of significantly altered vermal FC in participants with PD based on disease status (A and B) and cognitive status (C–F).

Scatterplots for only the significant correlations (p < 0.05) are shown here. Correlation of vermis:Brodmann area (BA) 19 (peristriate visual association cortex) significant cortical cluster resting-state functional connectivity (FC) [Fisher z(r) correlation coefficients] in Parkinson disease (PD) with (A) visuospatial domain z score and (B) composite cognitive z score. Correlation of vermis:BA9 (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) significant cortical cluster FC with (C) executive function z score, (D) attention z score, and (E) composite cognitive z score in participants with PD. Solid black circles represent participants with PD with cognitive impairment (PD-cog); open circles represent those without cognitive impairment (PD-nl).

Significantly lower vermal FC with DLPFC (noted in PD-cog) was similarly analyzed for cognitive correlates while controlling for appropriate covariates, including local cortical thickness and the volume of the vermis. Vermis:BA9 FC correlated with the z scores of attention (r = 0.25, df = 72, p = 0.03), executive function (r = 0.24, df = 72, p = 0.036), and the composite cognitive z score (r = 0.31, df = 73, p = 0.008), such that participants with PD with weaker FC had lower cognitive scores (figure 4, D–F). All the correlations reported here withstood Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons (at a false discovery rate of 0.1). It should also be noted that these results were based only on significant FC clusters that were rigorously multiple comparisons corrected.

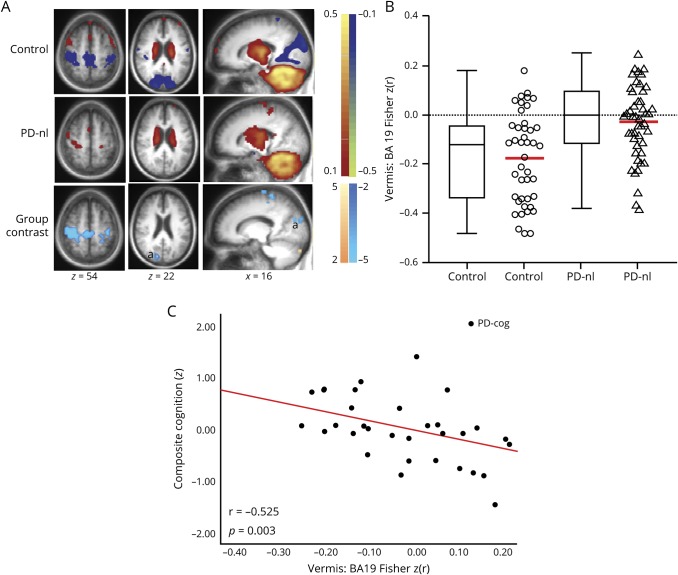

Post hoc analysis: Vermal FC in PD-nl

Our PD-nl subgroup failed to meet the CDR or MDS PD-MCI criteria for cognitive impairment. Nevertheless, the PD-nl cohort had significantly lower visuospatial z scores (ANCOVA; F1,88 = 4.485, p = 0.037) and composite cognitive z scores (ANCOVA; F1,88 = 4.559, p = 0.036) compared to controls after controlling for years of education (education level was significantly different between groups; p < 0.001). The PD-nl group, however, had only mild impairment (visuospatial z score ≥−0.87 and composite cognitive z score ≥−0.58, table 2). We further evaluated vermal FC group differences between controls (n = 43) and the PD-nl cohort (n = 47). Vermis:BA19 FC also was significantly weaker in the PD-nl cohort compared to controls (figure 5, A and B).

Figure 5. Vermal FC differences between participants with PD without cognitive impairment and controls.

(A) Resting-state functional connectivity (FC) [z(r) maps] with vermis seed region averaged over control participants (top row) and Parkinson disease (PD) group without cognitive impairment (PD-nl, middle row). Warm and cool colors represent positive and negative correlations. Random-effects analysis contrasting the controls and PD-nl group (bottom row). Mapped quantity is the gaussianized t statistic (z score) thresholded at |z| > 3.5. All clusters are significant at the p ≤ 0.05 level. Cool colors indicate more negative correlations in the control group. (B) Boxplots (with median value and interquartile range) and scatterplots with mean value (red) demonstrate the significantly weaker anticorrelations (closer to 0) of vermis:BA19 FC in the PD-nl group compared to controls and (C) correlation of vermis:BA19 significant cortical cluster FC with composite cognitive z score showing the much larger effect size (r = −0.525) in the subset of participants with PD with cognitive impairment (PD-cog). a = peristriate visual association cortex, BA19.

Discussion

We report detailed cognitive assessments combined with FC-MRI analysis of the cerebellum, using individual anatomic lobules and entire vermis as seed regions, in PD-cog and PD-nl. The principal findings in PD were weaker vermal correlations with the visual association cortex; weaker FC of the vermis with DLPFC in cognitively impaired participants; and significant correlation of the altered vermal FC with cognitive measures after controlling for potentially confounding variables, including cortical or cerebellar atrophy. Attributes of this study include the stringent FC-MRI QA measures, including global signal regression and censoring of high-artifact volumes, optimized cerebellar segmentation, inclusion of comprehensive neuropsychological assessment spanning 5 cognitive domains, and large participant samples. The importance of these QA factors in FC-MRI studies of PD has been described recently.17,27

Weaker FC of the vermis with visual association cortex (BA19) in participants with PD compared to controls correlated with lower visuospatial function and global cognition. This is important because visuospatial dysfunction predicts dementia onset in PD.4,5 In our data, the correlation of vermis:BA19 FC with global cognition had a much larger effect size (r = −0.53, p = 0.003) in the subset of participants with PD-cog (figure 5C). Prior longitudinal studies using [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose-PET showed that decreased metabolism in visual association cortex predicted dementia onset in PD.28 This result further elevates the importance of the altered vermis:BA19 FC findings reported here. Multiple cognitive domains, especially nonamnestic, can be affected in PD even early in the disease process.2 Consistent with this, the PD-nl subgroup had mild impairment of visuospatial function and global cognition compared to controls. The significant vermis:BA19 FC differences in this subgroup suggest that vermal FC could reflect early pathophysiology in a group who do not meet standard clinical criteria of cognitive impairment in PD.

Prior neuroimaging-based anatomic studies of PD revealed selective atrophy of posterior cortical areas, including visual association cortex, which correlated with visuospatial impairment.29 In contrast, we found no atrophy of the BA19 cortical cluster in our PD cohort. Prior PET studies showed enhanced BA19 regional cerebral blood flow responses to tasks involving visuospatial working memory with a distinct lateralization to the right hemisphere.30

In our data, bilateral vermal:BA19 FC significantly correlated with the composite cognitive z score, whereas the FC of the right BA19 also correlated with the visuospatial domain z score. This result agrees with the reported pattern of right lateralization, highlighting the pathophysiologic relevance of the altered vermal FC reported here.

A recent large-scale study by our group specifically investigated FC group difference in PD across the entire connectome and at the network level.17 Of note, there was substantial overlap in the participants with PD reported here. Directly relevant to this study, the greatest FC differences involved somatomotor, thalamic, and cerebellar networks with much smaller striatal effects. Impaired visuospatial performance (in those with PD and controls) correlated with weaker cerebellar-visual network correlations. The current study, using an independent seed-based approach, extends this observation by showing that the network-level differences could be driven by significantly altered FC between vermis and BA19. In contrast, striatal FC with caudate or putamenal seeds did not reveal similar FC abnormalities with visual association cortex.

Hypothetically, our findings, in aggregate, suggest an alternative pathophysiologic basis of vermal FC differences other than nigrostriatal pathology. We cannot directly support this hypothesis because none of our participants had dopaminergic imaging.

Our PD cohort did not differ from controls in cerebellar FC with other cortical regions traditionally associated with cognition. The mild degree of cognitive impairment in our PD cohort could account for this negative finding. The role of DLPFC in executive functions and attention has been clearly established; prior PET analysis of regional cerebral blood flow found coactivation of vermis and DLPFC with sequence learning tasks.31 We found significantly lower vermal FC with DLPFC in the PD-cog vs PD-nl contrast. More important, as one might anticipate, the strength of this FC correlated with attention and executive function. In contrast, FC between the striatum and DLPFC was not significantly altered according to disease or cognitive status in our cohort. Thus, altered vermal FC correlated with visuospatial, attention, and executive deficits in our PD cohort. This is important because worsening of deficits in these specific cognitive domains predicts progression from MCI to dementia in PD.4 Whether FC of the cerebellar vermis can predict subsequent cognitive decline in PD needs to be investigated longitudinally.

Cognitive status was not associated with significant atrophy in any cerebellar lobule, including the vermis, in our cohort. Prior voxel-based morphometric analyses also found no atrophy,32,33 yet some studies reported cerebellar gray matter loss in PD.34 A recent study reported only modest (≤5%) atrophy.12 The default SUIT template was used, which we found to provide poor segmentation of cerebellar lobules due to underlying atrophy in our older study participants. The discordance in the literature concerning cerebellar atrophy could reflect variability in patient demographics (e.g., age, sex, disease duration) or differences in methodology. The major pathologic hallmarks of PD, α-synuclein deposition with Lewy bodies or mitochondrial dysfunction, are conspicuously absent in the cerebellum, including the vermis.13 Hence, the lack of relevant atrophy in our cohort may suggest that the vermal FC differences could be secondary to alternative pathophysiology such as local neurotransmitter dysfunction.

Visuospatial domain impairments predict dementia onset3,5 and have been linked to cholinergic dysfunction. The vermis harbors a significant population of cholinergic neurons. This is corroborated by recent PET studies using presynaptic vesicular acetylcholine transporter tracer.35 The vermis also receives input from the cholinergic pedunculopontine nucleus.36 Selective degeneration in the pedunculopontine nucleus occurs in PD with as much as 43% neuronal loss and residual Lewy body pathology.37 Intriguingly, altered cerebellar FC with association cortex was limited to the vermis in our analysis. The cerebellum anatomically connects with BA19,6 and prior pathologic studies have demonstrated selective degeneration of cholinergic neurons in the extrastriate occipital cortex in PD.38 Vesicular acetylcholine transporter-SPECT and PET study of acetylcholinesterase activity has corroborated this result in patients with early-stage PD without dementia.39,40 Both studies found reduced cholinergic activity in these same visual association areas, which emphasizes the pathophysiologic importance of altered vermal FC. It is possible that the observed FC differences reflect cholinergic denervation of the vermis; this hypothesis remains to be tested.

Visuospatial dysfunction has been linked to visual hallucinations41; anticholinergics can provoke visual hallucinations,42 suggesting its cholinergic basis. Electric stimulation of visual association area BA19 elicits structured complex visual hallucinations.43 Selective atrophy of the cuneus and middle occipital gyrus (BA19) occurs in patients with PD with visual hallucinations independent of their cognitive status.44 Concomitant atrophy of the vermis may accompany this finding.45 Task-based fMRI studies have shown hyperactivation in the visual association cortex, including BA19, in patients with PD with hallucinations.46 Speculatively, the altered FC of the vermis with BA19 reported here may represent a link between visuospatial dysfunction, visual hallucinations, and subsequent onset of dementia.

Altered cerebellar-sensorimotor FC did not correlate with any motor behavioral measures, including UPDRS-III score and a gait/postural stability subscore. Omission of rigidity in the UPDRS-III used here may partly account for this negative finding. However, cerebellar hyperactivity failed to show any correlation with rigidity, bradykinesia, or UPDRS-III score11,47 in multiple prior fMRI studies, while another reported positive correlation with UPDRS score.48 Failure to detect correlation with the gait/postural stability measures, especially with the vermis, could be due to the restricted range of this dependent variable in our cohort. Whether the stronger cerebello-sensorimotor FC observed with bilateral lobules I through IV, V, and VI represents compensatory hyperactivity to counter motor deterioration remains speculative, but multiple prior fMRI studies have reported similar findings.13 Visuospatial deficits have also been linked to freezing41; altered vermal FC to the sensorimotor and the visual association cortex may reflect the common pathophysiologic basis, but this remains to be tested.

Our study has some limitations. We believe that strict quality control measures generally strengthen this study. However, rigorous head motion criteria led to exclusion of participants with PD (and controls) and could have preferentially eliminated participants with tremor-dominant motor subtype of PD (data were acquired in the “off” state). Analysis of the available data (including all participants with both UPDRS-II and UPDRS-III subscale scores) using the standard guidelines49 showed a large preponderance of postural instability and gait difficulty (PIGD) motor subtype in the starting PD cohort (96 of 138 [70%] were PIGD subtype), and this did not significantly differ from the ultimately reported PD cohort (38 of 56 [68%] were PIGD subtype). Hence, this likely was not a relevant issue in our study. Moreover, a recent study demonstrated the lack of stability and the inherent variability of this traditional characterization even early in PD.50 Cognitive impairment, when present, was only mild, but this did not preclude finding FC correlates. We used CDR to categorize cognitive status of the participants with PD. This could be another limitation because the CDR emphasizes memory impairment. However, altered vermal FC with association cortex did not correlate with memory z scores. Instead, we observed vermal FC with expected cognitive and pathophysiologic correlates. Antiparkinsonian medications (including amantadine) were held overnight. Only 7 participants with PD took benzodiazepines, but none before the imaging or clinical assessments on the day of the study. While this does not eliminate potential medication confounds, close scrutiny of the data (data available from Dryad, figure e-4, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.92b0gq1) and the small number of involved participants with PD suggest that medication bias was not a substantial issue. The restricted range of the gait/postural stability behavioral measures may also limit the current study. No behavioral correlates of altered cerebellar FC with SMC were detected, but the lack of more sophisticated motor measures likely led to a false-negative result.

This cerebellar FC-MRI analysis demonstrates cognitive correlates of significantly altered FC of the cerebellar vermis in PD. This is significant in view of the association of vermal FC with specific cognitive domains that predict progression to dementia. Whether these FC changes predict dementia remains to be determined. Our results pertain to the pathophysiology of cognitive impairment in PD and may ultimately lead to novel biomarkers and subsequent targets for therapeutic interventions. Cholinergic dysfunction of the vermis may underlie both altered FC and impaired cognition in PD; this hypothesis remains to be prospectively tested.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the study participants for their dedication, time, and effort to enhance the understanding of pathophysiology of PD.

GLOSSARY

- ANCOVA

analysis of covariance

- BA

Brodmann area

- CDR

Clinical Dementia Rating

- DLPFC

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- FC

resting-state functional connectivity

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- MDS

Movement Disorder Society

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- PD

Parkinson disease

- PD-cog

PD with cognitive impairment

- PD-nl

PD without cognitive impairment

- PIGD

postural instability and gait difficulty

- QA

quality assurance

- RMS

root-mean-squared

- SMC

sensorimotor cortex

- UPDRS-III

Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor subscale

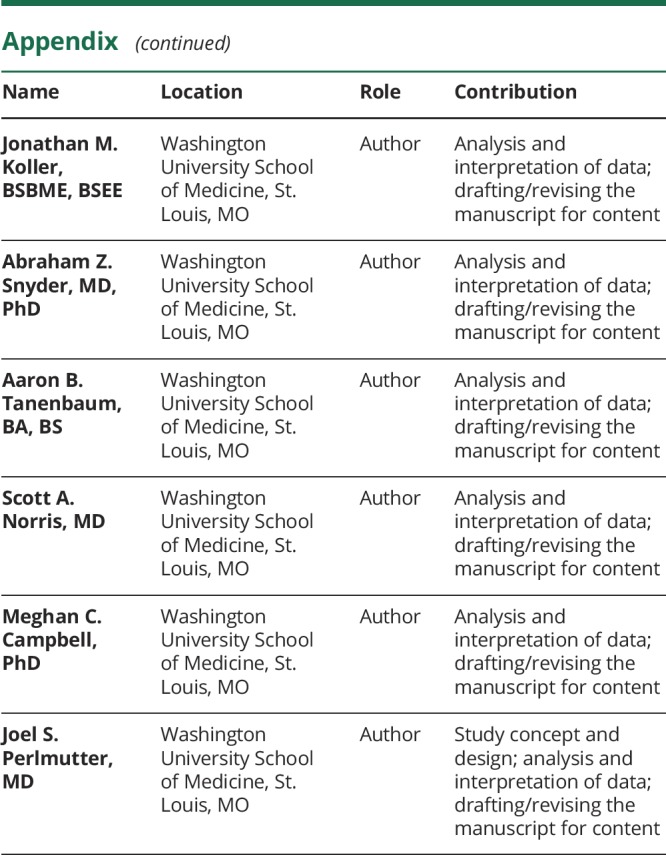

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

This work was supported by National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke/National Institute on Aging NIH RO1 NS075321, NIH RO1 NS097437, and P30 NS098577-01, American Academy of Neurology and American Brain Foundation Clinical Research Training Fellowship in Parkinson's Disease (to B.M), KL2 TR002346 National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH (to B.M), Parkinson Study Group, Parkinson's Disease Foundation Mentored Clinical Research Award (to B.M), American Parkinson Disease Association, Greater St. Louis Chapter of American Parkinson Disease Association, Washington University ICTS/Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation Clinical Translation Award (to M.C.C.), the Jo Oertli Fund, and the Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation (Elliot Stein Family Fund and Parkinson Disease Research Fund).

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Aarsland D, Kurz MW. The epidemiology of dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. Brain Pathol 2010;20:633–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aarsland D, Bronnick K, Larsen JP, Tysnes OB, Alves G; Norwegian ParkWest Study Group. Cognitive impairment in incident, untreated Parkinson disease: the Norwegian ParkWest study. Neurology 2009;72:1121–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kehagia AA, Barker RA, Robbins TW. Cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease: the dual syndrome hypothesis. Neurodegener Dis 2013;11:79–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gasca-Salas C, Estanga A, Clavero P, et al. Longitudinal assessment of the pattern of cognitive decline in non-demented patients with advanced Parkinson's disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2014;4:677–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams-Gray CH, Evans JR, Goris A, et al. The distinct cognitive syndromes of Parkinson's disease: 5 year follow-up of the CamPaIGN cohort. Brain 2009;132:2958–2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bostan AC, Dum RP, Strick PL. Cerebellar networks with the cerebral cortex and basal ganglia. Trends Cogn Sci 2013;17:241–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckner RL, Krienen FM, Castellanos A, Diaz JC, Yeo BT. The organization of the human cerebellum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol 2011;106:23222345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sang L, Qin W, Liu Y, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity of the vermal and hemispheric subregions of the cerebellum with both the cerebral cortical networks and subcortical structures. Neuroimage 2012;61:1213–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang C, Mattis P, Tang C, Perrine K, Carbon M, Eidelberg D. Metabolic brain networks associated with cognitive function in Parkinson's disease. Neuroimage 2007;34:714–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Festini SB, Bernard JA, Kwak Y, et al. Altered cerebellar connectivity in Parkinson's patients ON and OFF L-DOPA medication. Front Hum Neurosci 2015;9:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H, Edmiston EK, Fan G, et al. Altered resting-state functional connectivity of the dentate nucleus in Parkinson's disease. Psychiatry Res 2013;211:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Callaghan C, Hornberger M, Balsters JH, Halliday GM, Lewis SJ, Shine JM. Cerebellar atrophy in Parkinson's disease and its implication for network connectivity. Brain 2016;139:845–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu T, Hallett M. The cerebellum in Parkinson's disease. Brain 2013;136:696–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992;55:181–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Racette BA, Tabbal SD, Jennings D, Good LM, Perlmutter JS, Evanoff BA. A rapid method for mass screening for parkinsonism. Neurotoxicology 2006;27:357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdolahi A, Scoglio N, Killoran A, Dorsey ER, Biglan KM. Potential reliability and validity of a modified version of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale that could be administered remotely. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013;19:218–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gratton C, Koller JM, Shannon W, et al. Emergent functional network effects in Parkinson disease. Cereb Cortex 2019;29:2509–2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litvan I, Goldman JG, Troster AI, et al. Diagnostic criteria for mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease: Movement Disorder Society Task Force guidelines. Mov Disord 2012;27:349–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell MC, Koller JM, Snyder AZ, Buddhala C, Kotzbauer PT, Perlmutter JS. CSF proteins and resting-state functional connectivity in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2015;84:2413–2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diedrichsen J. A spatially unbiased atlas template of the human cerebellum. Neuroimage 2006;33:127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers PS, McNeely ME, Koller JM, Earhart GM, Campbell MC. Cerebellar volume and executive function in Parkinson disease with and without freezing of gait. J Parkinsons Dis 2017;7:149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage 2012;59:2142–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hacker CD, Perlmutter JS, Criswell SR, Ances BM, Snyder AZ. Resting state functional connectivity of the striatum in Parkinson's disease. Brain 2012;135:3699–3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med 1995;34:537541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciric R, Wolf DH, Power JD, et al. Benchmarking of participant-level confound regression strategies for the control of motion artifact in studies of functional connectivity. Neuroimage 2017;154:174–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohnen NI, Koeppe RA, Minoshima S, et al. Cerebral glucose metabolic features of Parkinson disease and incident dementia: longitudinal study. J Nucl Med 2011;52:848–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Diaz AI, Segura B, Baggio HC, et al. Cortical thinning correlates of changes in visuospatial and visuoperceptual performance in Parkinson's disease: a 4-year follow-up. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018;46:62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jonides J, Smith EE, Koeppe RA, Awh E, Minoshima S, Mintun MA. Spatial working memory in humans as revealed by PET. Nature 1993;363:623–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura T, Ghilardi MF, Mentis M, et al. Functional networks in motor sequence learning: abnormal topographies in Parkinson's disease. Hum Brain Mapp 2001;12:42–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagano-Saito A, Washimi Y, Arahata Y, et al. Cerebral atrophy and its relation to cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2005;64:224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burton EJ, McKeith IG, Burn DJ, Williams ED, O'Brien JT. Cerebral atrophy in Parkinson's disease with and without dementia: a comparison with Alzheimer's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and controls. Brain 2004;127:791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borghammer P, Ostergaard K, Cumming P, et al. A deformation-based morphometry study of patients with early-stage Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol 2010;17:314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrou M, Frey KA, Kilbourn MR, et al. In vivo imaging of human cholinergic nerve terminals with (-)-5-(18)F-fluoroethoxybenzovesamicol: biodistribution, dosimetry, and tracer kinetic analyses. J Nucl Med 2014;55:396–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muller ML, Bohnen NI. Cholinergic dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2013;13:377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gai WP, Halliday GM, Blumbergs PC, Geffen LB, Blessing WW. Substance P-containing neurons in the mesopontine tegmentum are severely affected in Parkinson's disease. Brain 1991;114:2253–2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perry EK, Curtis M, Dick DJ, et al. Cholinergic correlates of cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease: comparisons with Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985;48:413–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bohnen NI, Albin RL. Cholinergic denervation occurs early in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2009;73:256–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuhl DE, Minoshima S, Fessler JA, et al. In vivo mapping of cholinergic terminals in normal aging, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol 1996;40:399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davidsdottir S, Cronin-Golomb A, Lee A. Visual and spatial symptoms in Parkinson's disease. Vis Res 2005;45:1285–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Celesia GG, Wanamaker WM. Psychiatric disturbances in Parkinson's disease. Dis Nerv Syst 1972;33:577–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz R, Woermann FG, Ebner A. When written words become moving pictures: complex visual hallucinations on stimulation of the lateral occipital lobe. Epilepsy Behav 2007;11:147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldman JG, Stebbins GT, Dinh V, et al. Visuoperceptive region atrophy independent of cognitive status in patients with Parkinson's disease with hallucinations. Brain 2014;137:849–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pagonabarraga J, Soriano-Mas C, Llebaria G, Lopez-Sola M, Pujol J, Kulisevsky J. Neural correlates of minor hallucinations in non-demented patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014;20:290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holroyd S, Wooten GF. Preliminary FMRI evidence of visual system dysfunction in Parkinson's disease patients with visual hallucinations. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;18:402–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu H, Sternad D, Corcos DM, Vaillancourt DE. Role of hyperactive cerebellum and motor cortex in Parkinson's disease. Neuroimage 2007;35:222–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu T, Wang L, Chen Y, Zhao C, Li K, Chan P. Changes of functional connectivity of the motor network in the resting state in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett 2009;460:6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jankovic J, McDermott M, Carter J, et al. Variable expression of Parkinson's disease: a base-line analysis of the DATATOP cohort: the Parkinson Study Group. Neurology 1990;40:1529–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simuni T, Caspell-Garcia C, Coffey C, et al. How stable are Parkinson's disease subtypes in de novo patients: analysis of the PPMI cohort? Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;28:62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared on request by any qualified investigator.