Abstract

The pepper weevil, Anthonomus eugenii Cano (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), is the main insect pest of peppers (Capsicum spp.) throughout the southern U.S. and a potential target for novel control methods that may require gene expression analyses. Careful selection of adequate reference genes to normalize RT-qPCR data is an important prerequisite for gene expression studies since the expression stability of reference genes can be affected by the experimental conditions leading to biased or erroneous results. The lack of studies on validation of reference genes for RT-qPCR analysis in A. eugenii limits the investigation of gene expression, therefore it is needed a systematic selection of suitable reference genes for data normalization. In the present study, three programs (BestKeeper, geNorm and NormFinder) were used to analyze the expression stability of candidate reference genes (β-ACT, ArgK, EF1-α, GAPDH, RPL12, RPS23, α-TUB, 18S and 28S) in A. eugenii under different experimental conditions. Our results revealed that the most stably expressed reference genes in A. eugenii varied according to the experimental condition evaluated: developmental stages (EF1-α, 18S and RPL12), sex (RPS23 and RPL12), low temperature (GAPDH and α-TUB), high temperature (α-TUB and RPS23), all temperatures (α-TUB and GAPDH), starvation (RPL12 and α-TUB), and dsRNA exposure (α-TUB and RPL12). Our study provides for the first time valuable information on appropriate reference genes that can be used in the analysis of gene expression by RT-qPCR in biological experiments involving A. eugenii.

Subject terms: RNAi, RNAi, RNAi, RNA, RNA

Introduction

Reverse-transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) is widely used in gene expression studies due to its simplicity, reproducibility, high sensitivity, accuracy and cost-effectiveness1,2. Although RT-qPCR is considered a highly accurate technique, several experimental factors can lead to results that are not reliable measurements of gene expression. These factors include purity and integrity of RNA, quantity of starting RNA and cDNA, reverse transcription and PCR efficiency, and pipetting errors3. Thus, in RT-qPCR analysis is necessary to use reference genes to normalize the data in order to eliminate or at least reduce the technical variation among the tested samples and precisely estimate the expression of the target genes4.

Usually, housekeeping genes related to basic cellular functions are used as reference genes in the normalization strategy because these genes are supposed to have constitutive and stable expression under a variety of physiological conditions and experimental treatments. However, several studies have demonstrated that the expression of housekeeping genes is not always stable and can be influenced by developmental stage, tissue, sex, and biotic or abiotic stresses that the organism is subjected5–9. Therefore, the selection of suitable reference genes according to the specific experimental conditions is essential to ensure accurate results.

The pepper weevil, Anthonomus eugenii Cano (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), is the most economically important pest of cultivated peppers (Capsicum spp.) in the southern United States, Mexico, Central America and some Caribbean islands10–15. A. eugenii larvae feed preferentially inside floral buds and immature fruits, while adults feed on buds, flowers, fruits, and even young leaves. Premature abscission of the fruits as a result of larval and adult feeding leads to losses in the production of marketable fruits which is the main damage caused by this insect16.

Gene expression analysis is an important tool to improve the understanding of molecular and genetic processes in A. eugenii, which in turn may provide insight into the development of novel management strategies for this emerging insect pest, such as RNAi-based control methods. However, optimal reference genes for RT-qPCR data normalization have not yet been identified in A. eugenii, thereby limiting further studies of gene expression. In this study, the stability of nine candidate reference genes, including β-Actin (β-ACT), Arginine kinase (ArgK), Elongation factor 1-α (EF1-α), Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), 60S ribosomal protein L12 (RPL12), 40 ribosomal protein S23 (RPS23), α-Tubulin (α-TUB), 18S ribosomal RNA (18S) and 28S ribosomal RNA (28S) was evaluated using three statistical algorithms, BestKeeper, geNorm and NormFinder. In addition, the most stable reference genes for dsRNA treatment were used to evaluate the expression of target genes in insects treated with RpII140 and Prosα-2 dsRNA.

Results

Primer specificity and efficiency of candidate reference genes

PCR products generated by each primer pair using cDNA from A. eugenii as a template were visualized as single bands of the expected size on 1.5% agarose gel (Supplementary Fig. S1). The specificity of primer pairs was confirmed by sequencing of RT-PCR products and alignment with their corresponding gene fragment sequences. Additionally, the primer specificity was evaluated by melting curve analysis which showed the presence of a single peak (Supplementary Fig. S2). A standard curve was generated for each primer pair using a serial dilution of the cDNA in order to calculate the correlation coefficient (R2) and primer efficiency (E). E values varied from 93.65% to 108.39% and R2 values were superior to 0.993 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Primers for the candidate reference genes and RNAi target genes used in the RT-qPCR analyses.

| Gene | Acession number | Primer | Sequence 5′-3′ | Size (bp) | Eff. (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-ACT | MH560343 | β-ACT-Ae-qp-F | GGCATCCTCACCCTGAAATA | 98 | 108.02 | 0.9938 |

| β-ACT-Ae-qp-R | CGCAGCTCGTTGTAGAAGGT | |||||

| ArgK | MK440119 | ArgK-Ae-qp-F | CCCAGACAAAGTGGAGGAAA | 113 | 103.92 | 0.9998 |

| ArgK-Ae-qp-R | TCTCCACTCGTGTCAGATGC | |||||

| EF1-α | MK440120 | EF1-α-Ae-qp-F | TCTCCAAAAACGGACAGACC | 100 | 98.42 | 0.9998 |

| EF1-α-Ae-qp-R | GGTTCAGTGGAATCCATTTTGT | |||||

| GAPDH | MH560346 | GAPDH-Ae-qp-F | GACTTTACCGACAGCCTTGG | 90 | 103.95 | 0.9976 |

| GAPDH-Ae-qp-R | CCCTCTGGAAAGTTGTGGAG | |||||

| RPL12 | MK440124 | RPL12-Ae-qp-F | TGTGATTTTCAGCCCTTTCC | 80 | 101.66 | 0.9996 |

| RPL12-Ae-qp-R | GCCCTTTAGGTCTGTCACCA | |||||

| RPS23 | MK440125 | RPS23-Ae-qp-F | TTCCTACCGAAACCTGCAAC | 97 | 102.25 | 0.9998 |

| RPS23-Ae-qp-R | AGAACGGCAAGAAAATCACG | |||||

| α-TUB | MK440121 | α-TUB-Ae-qp-F | ACTGGTGTCCAACAGGTTTCA | 93 | 105.73 | 0.9999 |

| α-TUB-Ae-qp-R | ACACGGCACGTTGTACCTTT | |||||

| 18S | MK434327 | 18S-Ae-qp-F | CGCTAGCTGGCATCGTTTAT | 117 | 91.95 | 0.9997 |

| 18S-Ae-qp-R | ACGAACAGAAGCGAAAGCAT | |||||

| 28S | MK434925 | 28S-Ae-qp-F | TGCCATCTCCCACTTATGCT | 95 | 92.17 | 0.9956 |

| 28S-Ae-qp-R | GGAAAAATTAGCGGGGAAAG | |||||

| RpII140 | MK440123 | RpII140-Ae-qp-F | ATAATCGAAGCGCACACTCC | 108 | 96.52 | 0.9694 |

| RpII140-Ae-qp-R | CATGTCTCCCGATGATTTGA | |||||

| Prosα-2 | MK440122 | Prosα-2-Ae-qp-F | CGTTTTTGGAGAAAAGATACAGTG | 86 | 105.63 | 0.9776 |

| Prosα-2-Ae-qp-R | CTCGAAGCTCTCCTTCAACG |

Expression profile of candidate reference genes

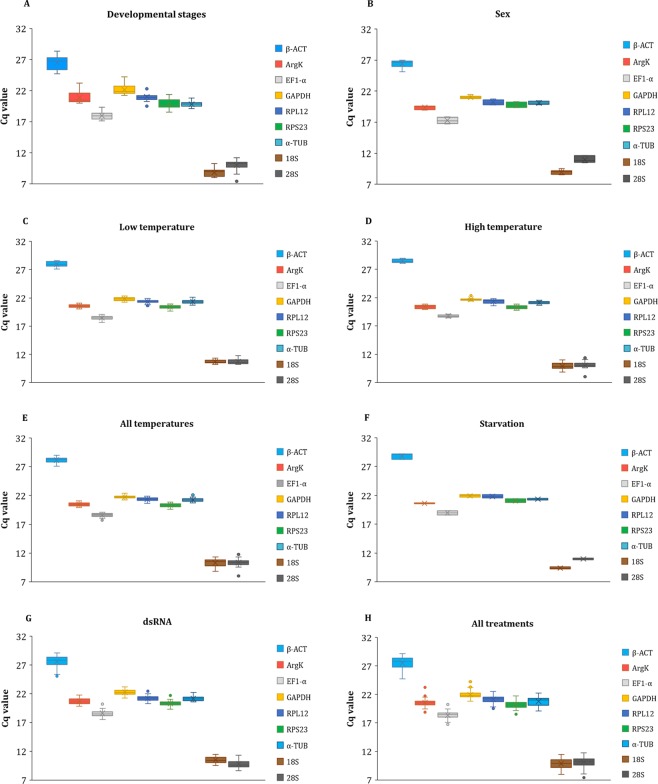

The mean quantification cycle (Cq) values varied considerably among the nine candidate reference genes, ranging from 8.82 (18S) in samples from different developmental stages to 28.83 (β-ACT) in samples from the starvation experiment (Fig. 1A,F). Overall, the candidate reference genes displayed similar expression patterns under different treatments. 18S and 28S had the lowest mean Cq values in all experimental conditions exhibiting the highest expression levels, whereas β-ACT and GAPDH showed the highest mean Cq values corresponding to the lowest expression levels (Fig. 1A–G). The mean Cq values of the reference genes considering all treatments varied from 9.86 (18S) to 27.45 (GAPDH) and the standard deviations (SD) of Cq values ranged from 0.58 (RPS23) to 1.16 (β-ACT) (Fig. 1H).

Figure 1.

Expression profiles of candidate reference genes in different experimental conditions. Box and whisker plot chart showing the range of Cq values for each candidate reference gene under different treatments, developmental stages (A), sex (B), low temperature (C), high temperature (D), all temperatures (E), starvation (F), dsRNA (G) and in all treatments (H). The upper and lower edges of the boxes indicate the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. Whiskers represent the minimum and maximum Cq values, the line and the x within the box marks indicate the median and mean, respectively. Small circles indicate the outliers.

Stability of candidate reference genes under different experimental conditions

Developmental stages

EF1-α, 18S, 28S and α-TUB were determined to be the most stable reference genes by BestKeeper and NormFinder among different developmental stages, while RPL12, RPS23 and EF1-α were the top three most reliable reference genes according to geNorm. In contrast, geNorm and NormFinder ranked β-ACT and ArgK as the most unstable reference genes, whereas ArgK and α-TUB were considered the least appropriate genes by BestKeeper (Table 2).

Table 2.

Stability of candidate reference genes according to BestKeeper, geNorm and NormFinder.

| Experimental condition | Ranking | BestKeeper | geNorm | NormFinder | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Coefficient correlation (r) | Gene | M value | Gene | Stability value | ||

| Developmental stages | 1 | EF1-α | 0.930 | RPL12 | 0.401 | EF1-α | 0.163 |

| 2 | 18S | 0.867 | RPS23 | 0.414 | 18S | 0.240 | |

| 3 | 28S | 0.823 | EF1-α | 0.441 | α-TUB | 0.313 | |

| 4 | RPL12 | 0.769 | 28S | 0.539 | RPL12 | 0.325 | |

| 5 | RPS23 | 0.759 | 18S | 0.584 | 28S | 0.349 | |

| 6 | GAPDH | 0.606 | α-TUB | 0.624 | GAPDH | 0.401 | |

| 7 | β-ACT | 0.514 | GAPDH | 0.686 | RPS23 | 0.411 | |

| 8 | α-TUB | 0.503 | ArgK | 0.737 | ArgK | 0.454 | |

| 9 | ArgK | 0.426 | β-ACT | 0.875 | β-ACT | 0.786 | |

| Sex | 1 | RPS23 | 0.969 | RPL12 | 0.094 | α-TUB | 0.050 |

| 2 | RPL12 | 0.944 | RPS23 | 0.095 | GAPDH | 0.079 | |

| 3 | GAPDH | 0.917 | EF1-α | 0.097 | RPS23 | 0.134 | |

| 4 | 28S | 0.916 | 28S | 0.130 | RPL12 | 0.156 | |

| 5 | EF1-α | 0.915 | α-TUB | 0.198 | 18S | 0.183 | |

| 6 | α-TUB | 0.907 | GAPDH | 0.221 | EF1-α | 0.207 | |

| 7 | 18S | 0.820 | 18S | 0.236 | 28S | 0.215 | |

| 8 | β-ACT | 0.206 | ArgK | 0.313 | ArgK | 0.298 | |

| 9 | ArgK | −0.160 | β-ACT | 0.409 | β-ACT | 0.430 | |

| Low temperature | 1 | GAPDH | 0.985 | GAPDH | 0.148 | GAPDH | 0.054 |

| 2 | α-TUB | 0.933 | α-TUB | 0.156 | EF1A | 0.086 | |

| 3 | EF1-α | 0.930 | EF1-α | 0.159 | α-TUB | 0.107 | |

| 4 | 18S | 0.912 | 18S | 0.173 | 18S | 0.110 | |

| 5 | 28S/RPS23 | 0.888 | ArgK | 0.190 | RPS23 | 0.117 | |

| 6 | 28S | 0.233 | ArgK | 0.119 | |||

| 7 | ArgK | 0.832 | RPL12 | 0.267 | 28S | 0.157 | |

| 8 | β-ACT | 0.610 | β-ACT | 0.302 | RPL12 | 0.178 | |

| 9 | RPL12 | 0.578 | RPS23 | 0.331 | β-ACT | 0.212 | |

| High temperature | 1 | 28S | 0.949 | α-TUB | 0.249 | GAPDH | 0.122 |

| 2 | 18S | 0.943 | RPS23 | 0.251 | RPS23 | 0.149 | |

| 3 | α-TUB | 0.922 | GAPDH | 0.261 | EF1-α | 0.152 | |

| 4 | RPS23 | 0.837 | EF1-α | 0.276 | α-TUB | 0.174 | |

| 5 | GAPDH | 0.656 | RPL12 | 0.296 | ArgK | 0.179 | |

| 6 | RPL12 | 0.551 | β-ACT | 0.317 | β-ACT | 0.189 | |

| 7 | EF1-α | 0.207 | ArgK | 0.351 | RPL12 | 0.251 | |

| 8 | ArgK | 0.076 | 18S | 0.391 | 28S | 0.307 | |

| 9 | β-ACT | −0.152 | 28S | 0.455 | 18S | 0.735 | |

| All temperatures | 1 | α-TUB | 0.917 | GAPDH | 0.235 | GAPDH | 0.101 |

| 2 | 28S | 0.907 | α-TUB | 0.256 | α-TUB | 0.111 | |

| 3 | 18S | 0.866 | ArgK | 0.271 | RPS23 | 0.122 | |

| 4 | RPS23 | 0.816 | EF1-α | 0.315 | ArgK | 0.205 | |

| 5 | GAPDH | 0.807 | RPL12 | 0.346 | EF1-α | 0.215 | |

| 6 | RPL12 | 0.522 | RPS23 | 0.369 | RPL12 | 0.225 | |

| 7 | ArgK | 0.505 | β-ACT | 0.396 | 18S | 0.307 | |

| 8 | EF1-α | 0.326 | 18S | 0.446 | 28S | 0.310 | |

| 9 | β-ACT | −0.009 | 28S | 0.490 | β-ACT | 0.360 | |

| Starvation | 1 | RPL12 | 1.006 | 18S | 0.070 | RPL12 | 0.020 |

| 2 | RPS23 | 1.001 | α-TUB | 0.080 | GAPDH | 0.036 | |

| 3 | α-TUB | 0.999 | RPL12 | 0.090 | 18S | 0.041 | |

| 4 | EF1-α | 0.988 | GAPDH | 0.100 | α-TUB | 0.058 | |

| 5 | 18S | 0.979 | RPS23 | 0.114 | RPS23 | 0.070 | |

| 6 | ArgK | 0.946 | EF1-α | 0.124 | EF1-α | 0.090 | |

| 7 | GAPDH | 0.936 | ArgK | 0.143 | ArgK | 0.117 | |

| 8 | β-ACT | 0.829 | 28S | 0.169 | 28S | 0.190 | |

| 9 | 28S | 0.281 | β-ACT | 0.220 | β-ACT | 0.270 | |

| dsRNA | 1 | α-TUB | 0.839 | RPL12 | 0.144 | α-TUB | 0.135 |

| 2 | 28S | 0.810 | RPS23 | 0.147 | RPL12 | 0.159 | |

| 3 | RPL12 | 0.794 | α-TUB | 0.169 | RPS23 | 0.188 | |

| 4 | RPS23 | 0.793 | 18S | 0.234 | GAPDH | 0.278 | |

| 5 | 18S | 0.774 | 28S | 0.251 | EF1-α | 0.279 | |

| 6 | EF1-α | 0.634 | EF1-α | 0.275 | 18S | 0.311 | |

| 7 | ArgK | 0.485 | ArgK | 0.324 | ArgK | 0.325 | |

| 8 | GAPDH | 0.200 | GAPDH | 0.358 | 28S | 0.388 | |

| 9 | β-ACT | 0.144 | β-ACT | 0.403 | β-ACT | 0.624 | |

Sex

Different sets of suitable reference genes were identified by each algorithm when both sexes were evaluated. The most stable genes were RPS23, RPL12 and GAPDH according to BestKeeper, RPL12, RPS23 and EF1-α based on geNorm analysis, and α-TUB, GAPDH and RPS23 by NormFinder. All algorithms indicated that β-ACT and ArgK exhibited the highest variations in expression (Table 2).

Low temperature

Consistent results were obtained by all algorithms which included GAPDH, α-TUB and EF1-α as the top three most stable reference genes under low temperature treatment. β-ACT and RPL12 were ranked as the least stable genes by BestKeeper and NormFinder, and β-ACT and RPS23 by geNorm (Table 2).

High temperature

28S, 18S and α-TUB were ranked as the most suitable genes by BestKeeper, α-TUB, RPS23 and GAPDH by geNorm, and GAPDH, RPS23 and EF1-α by NormFinder under high temperature treatment. GeNorm and NormFinder identified 18S and 28S as the least stable genes, whereas BestKeeper indicated that β-ACT and ArgK had the worst performance (Table 2).

All temperatures

When the gene stability was evaluated in insects submitted to high and low temperature stresses, GAPDH and α-TUB were the most stably expressed reference genes followed by ArgK or RPS23, according to geNorm and NormFinder. Based on BestKeeper, α-TUB, 28S and 18S displayed the most stable expression. β-ACT and EF1-α; 28S and 18S; β-ACT and 28S were the least stable genes according to BestKeeper, geNorm and NormFinder, respectively (Table 2).

Starvation

BestKeeper analysis revealed that RPL12, RPS23 and α-TUB were the most stably expressed genes under starvation condition, while geNorm identified 18S, α-TUB and RPL12 as the most stable genes. According to results from NormFinder, RPL12, GAPDH and 18S showed the highest stability. All algorithms indicated that β-ACT and 28S were highly variable in their expression levels (Table 2).

dsRNA

Based on geNorm and NormFinder, RPL12, RPS23 and α-TUB exhibited the highest expression stability for dsRNA exposure experiment, while BestKeeper indicated α-TUB, 28S and RPL12 as the most stable genes. BestKeeper and geNorm ranked GAPDH and β-ACT as the least stably expressed genes, while NormFinder indicated that 28S and β-ACT were the least stable (Table 2).

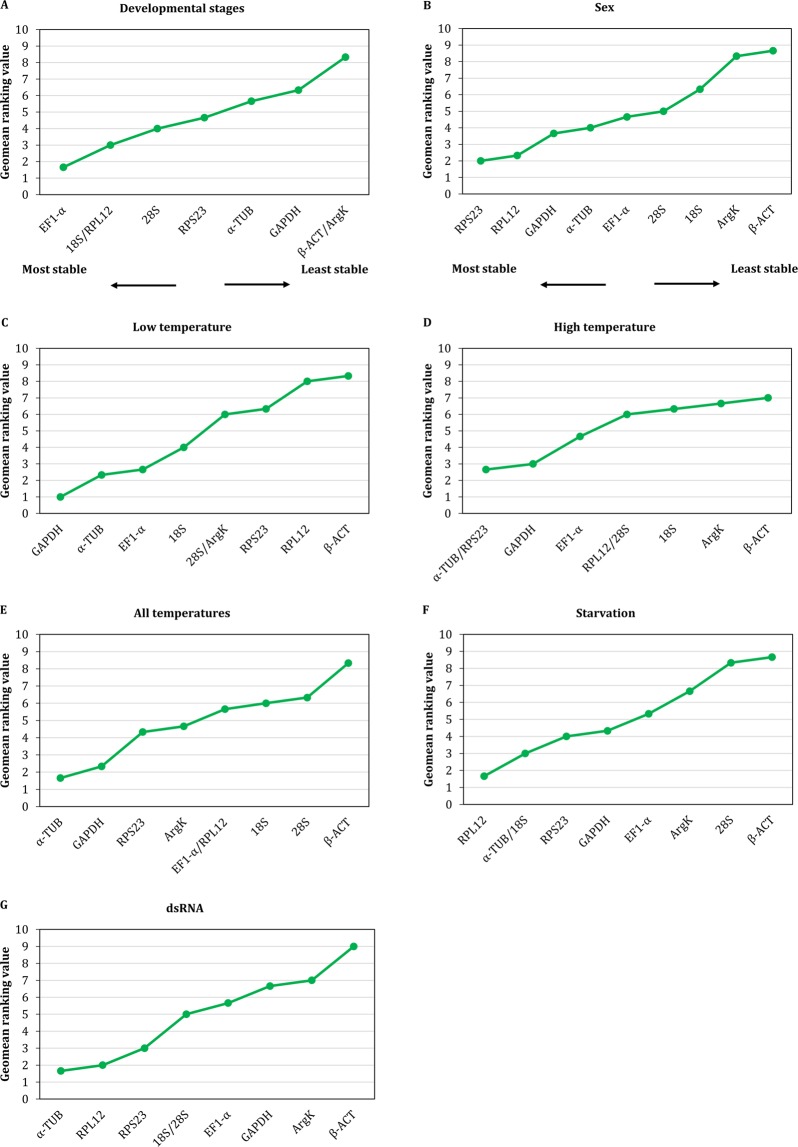

Overall ranking of candidate reference genes

As shown in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1, the comprehensive ranking of candidate reference genes from the most to the least stable among the experimental conditions was as follows: EF1-α > 18S/RPL12 > 28S > RPS23 > α-TUB > GAPDH > β-ACT/ArgK across the developmental stages; RPS23 > RPL12 > GAPDH > α-TUB > EF1-α > 28S > 18S > ArgK > β-ACT for sex; GAPDH > α-TUB > EF1-α > 18S > 28S/ArgK > RPS23 > RPL12 > β-ACT for insects submitted to low temperatures; α-TUB/RPS23 > GAPDH > EF1-α > RPL12/28S > 18S > ArgK > β-ACT for insects exposed to high temperatures; α-TUB > GAPDH > RPS23 > ArgK > EF1-α/RPL12 > 18S > 28S > β-ACT when all temperatures where taken in account; RPL12 > α-TUB/18S > RPS23 > GAPDH > EF1-α > ArgK > 28S > β-ACT for starvation stress; and α-TUB > RPL12 > RPS23 > 18S/28S > EF1-α > GAPDH > ArgK > β-ACT for dsRNA treatment.

Figure 2.

Comprehensive stability ranking of candidate reference genes based on BestKeeper, geNorm and NormFinder results.

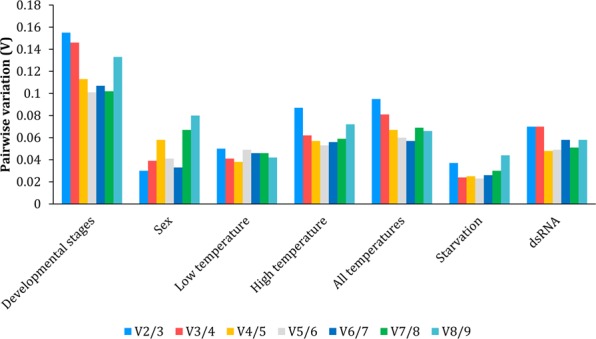

Optimal number of candidate reference genes

The pairwise variation (Vn/n + 1) analyses between two sequential normalization factors indicated that the pairwise variation V2/3 value was lower than the threshold value of 0.15 for sex, temperature, starvation and dsRNA treatments, suggesting that two reference genes are the optimal number of reference genes for accurate normalization of gene expression data in A. eugenii under these conditions. The pairwise variation V3/4 value was below the acceptable limit across developmental stages, therefore the use of three reference genes would be advisable to normalize the gene expression data (Fig. 3). The best combination of reference genes for normalization in each experimental condition is shown in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Determination of the optimal number of reference genes for accurate normalization using pairwise variation (Vn/n + 1) analysis by geNorm.

Table 3.

Recommended reference genes according to the experimental condition.

| Experimental condition | Reference genes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental stages | EF1-α | 18S | RPL12 |

| Sex | RPS23 | RPL12 | |

| Low temperature | GAPDH | α-TUB | |

| High temperature | α-TUB | RPS23 | |

| All temperatures | α-TUB | GAPDH | |

| Starvation | RPL12 | α-TUB | |

| dsRNA | α-TUB | RPL12 | |

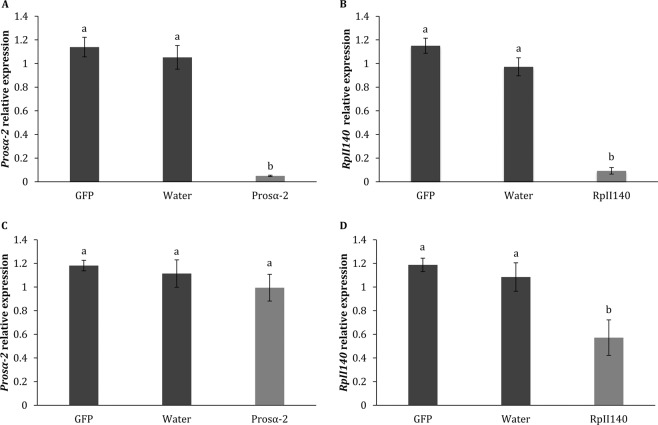

Reference gene validation

In order to validate some of the reference genes selected in this study, we evaluated the expression level of DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB2 (RpII140) and Proteasome subunit alpha type2 (Prosα-2) genes in insects treated with the respective dsRNAs for these genes using the recommended set of reference genes (α-TUB and RPL12). We observed a significant gene knockdown of 92.2% and 96.5% in the insects injected with dsRNA targeting RpII140 and Prosα-2, respectively, compared to the control treatment in which the insects were injected with GFP dsRNA. However, only the insects fed on RpII140 dsRNA showed a significant decrease in gene expression level by 51.7% (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Relative expression of Prosα-2 and RpII140 genes using the recommended reference genes (α-TUB and RPL12) for normalization. Expression of target RNAi genes in insects injected with dsRNA (A,B) and insects fed on dsRNA (C,D). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of error. Different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05 (One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test).

Discussion

RT-qPCR has been used extensively to assess gene expression in entomological research17–20. Normalization of RT-qPCR data with reference genes is one of the most common strategies used to correct experimental errors introduced through the steps of RT-qPCR analysis; however, the choice of reference genes with low expression variation is necessary to guarantee valid normalization and avoid inaccurate gene expression quantification21,22. Molecular studies provide important information about the genetic mechanisms underlying a variety of biological events and metabolic pathways, but only a few studies at the molecular level have been performed on A. eugenii. The selection of suitable reference genes for gene expression analysis will facilitate and boost such investigations in this important pest species.

In the present study, differences in the stability of potential reference genes were evaluated in order to select appropriate normalization factors for gene expression analysis in A. eugenii. Our results demonstrated that while some genes were ranked at the same position by BestKeeper, geNorm and NormFinder for a given condition, in general the stability ranking of the reference genes generated by these algorithms varied considerably. Variation in the ranking order has been observed in many studies and can be attributed to the different statistical approaches implemented in the algorithms23,24. To address this issue, a comprehensive ranking of reference genes was created based on the ranking value attributed by the algorithms geNorm, NormFinder and BestKeeper as performed previously25–28.

Our results indicated that α-TUB and RPL12 were consistently ranked as the most stable genes according to the overall ranking and at least one of these genes was included in the set of normalizer genes suggested for each experimental condition. α-TUB is the main component of microtubules that form the cytoskeleton structure, which plays an important role in several eukaryotic cellular processes, including cell mobility and division, and intracellular trafficking29. Our results are consistent with previous studies reporting that α-TUB was stable for developmental stages, sexes, tissues, temperature and photoperiod stresses in Empoasca onukii8, among various tissues from Coleomegilla maculata30 and Mythimna separata24, for different temperatures in Phenacoccus solenopsis31 as well as for developmental stages, tissues and sexes in Hermetia illucens32. The RPL12 gene encodes a structural protein of ribosomes and is involved in protein translation33. This gene exhibited high stability in Acyrthosiphon pisum exposed to temperature stresses34 and in M. separata under different photoperiod and temperature treatments, and larval tissues35.

In contrast to our results, α-TUB was not a suitable reference gene for normalization across developmental stages of Cryptolestes ferrugineus36, in different tissues of Diaphorina citri37, developmental stages, sexes and in response to temperature stress in Propylea japonica38, and in nonviruliferous/viruliferous Frankliniella occidentalis39. These results indicate that the gene stability can be affected by the biotic and abiotic conditions and even the insect species evaluated. As a consequence, the selection of condition-specific reference genes is strongly recommended prior RT-qPCR analysis.

Our analyses further identified β-ACT and ArgK as the least stable reference genes for most of the experimental conditions indicating that these genes are not ideal for RT-qPCR data normalization in A. eugenii under the conditions tested. Although β-ACT and ArgK are traditional reference genes and have been used in many gene expression studies, they are not always stably expressed. Consistent with our results, many studies have shown unstable expression of β-ACT under variable conditions in a variety of species, including Bemisia tabaci40, M. separata35, F. occidentalis39, Henosepilachna vigintioctopunctata41, P. japonica38, Hippodamia convergens42 and C. maculata30, as well as for ArgK in Spodoptera litura43, P. japonica38, C. maculata30 and E. onukii8.

The evaluation of gene expression is a fundamental and routine analysis in RNAi-related studies, and therefore the choice of adequate reference genes is crucial to achieve precise results. We demonstrated that the selected reference genes were suitable to measure the relative expression of the target genes Prosα-2 and RpII140 in insects treated with dsRNA corresponding to these genes. The reference genes α-TUB and RPL12 identified in our work can be useful for normalization of target gene expression levels in further research on RNAi in A. eugenii. To date, neither the genomic or transcriptomic data are available for A. eugenii; however, this sequencing information could provide a valuable resource to gain a deeper understanding of different molecular mechanisms and to discover potential target genes that can be used in RNAi-mediated control methods against this insect pest. Future studies should focus on genome and transcriptome sequencing to fill the gap of genetic information on A. eugenii.

Despite the importance of accessing reference gene stability, these analyses are often not performed prior gene expression studies44,45. Our results highlighted the need to adopt this practice for proper normalization of RT-qPCR data. We found that the best combinations of reference genes that should be used as internal controls were EF1-α, 18S and RPL12 for developmental stages; RPS23 and RPL12 for sex, GAPDH and α-TUB for low temperature; α-TUB and RPS23 for high temperature; α-TUB and GAPDH for all temperatures; RPL12 and α-TUB for starvation; α-TUB and RPL12 for dsRNA treatment. The selected reference genes may be helpful in further gene expression studies in A. eugenii. In addition, the set of primers validated in this study can be used to evaluate the suitability of the candidate reference genes in experimental conditions other than those tested here.

Methods

Insect colony

A. eugenii colony was maintained at 27 ± 10 °C, 30 ± 5% relative humidity, 14:10 h light:dark photoperiod and supplied with jalapeno peppers (Capsicum annuum) as an oviposition substrate and food source for both larvae and adults.

Reference gene selection, gene fragment cloning and primer design

Based on a literature search, we selected nine genes (β-ACT, ArgK, EF1-α, GAPDH, RPL12, RPS23, α-TUB, 18S and 28S) commonly used as reference genes and that have shown high stability in other insect species to investigate their suitability as reference genes for RT-qPCR in A. eugenii7,8,30,34,43,46. Degenerate primers for RPS23, 18S, 28S and RpII140 were manually designed based on conserved nucleotide sequence among other Coleoptera species. Primers for ArgK, EF1-α, RPL12, α-TUB and Prosα-2 were obtained from previous works30,47 (Supplementary Table S2). PCR amplifications consisted of 5 µL of 10x PCR buffer, 8 µL of MgCl2 (50 mM), 5 µL of dNTPs mix (10 mM of each nucleotide), 8 µL of each primer (10 µM), 1.25 µL of Taq DNA Polymerase (5U/µL) (ThermoFisher Scientific), 2 µL of cDNA (diluted 10×) and 12.75 µL of nuclease-free water. The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: one cycle of 95 °C for 3 min; 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 sec, 50–55 °C for 30 sec and 72 °C for 30 sec; a final cycle of 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) and cloned into the pJET1.2/blunt cloning vector using the CloneJET PCR Cloning Kit (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Recombinant plasmids were transformed into One Shot® TOP10 Chemically Competent Escherichia coli cells (Invitrogen) and sequenced by GENEWIZ company (South Plainfield, NJ, USA). According to the partial sequences of the genes, specific primers were designed using Primer3Plus software48 (http://www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/primer3plus/primer3plus.cgi). Primers for β-ACT gene were designed based on the sequence available on NCBI (Accession number MH560343) and the primers for GAPDH were obtained from a previous work49 (Table 1).

Experimental treatments

Developmental stages

Samples of each developmental stage of A. eugenii including eggs, first, second and third instars, pupae and adults were collected. Each biological replicate included 20 eggs, 18 first instar larvae, 12 second instar larvae, 10 third instar larvae, 6 pupae or 6 adults (3 females and 3 males).

Sex

Six adults of A. eugenii (males or females) were pooled as one biological replicate.

Starvation

A. eugenii adults were placed in a plastic vial and starved for 24 h at 27 ± 1 °C, 75 ± 5% relative humidity in a growth chamber. Each biological replicate consisted of six insects.

Temperature

To examine the effects of temperature on gene expression stability, A. eugenii adults were exposed to temperatures ranging from 5–40 °C at 5 °C increments for 3 h in a climate-controlled chamber. Insects maintained at 5–20 °C were included in the low temperature treatment, while insects maintained at 30–40 °C were included in the high temperature treatment. Insects exposed to 25 °C constituted the control group for both treatments. Each biological replicate consisted of six adults. Gene expression stability was also evaluated when insects exposed to all temperatures were taken into account.

dsRNA

For the RNAi experiments, we selected two target genes (RpII140 and Prosα-2) that could potentially be used in RNAi-mediated control methods against A. eugenii based on previous studies demonstrating mortality of insects exposed to dsRNA targeting homologs of these genes50,51. DNA template for the synthesis of dsRNA was amplified by PCR using gene-specific primers containing a T7 polymerase promoter sequence at the 5′ (Table 4) from plasmid DNA. The PCR reaction was purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) and the dsRNA synthesized and purified using the MEGAScriptTM RNAi Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the bioassay by microinjection, A. eugenii adults (11–12 insects) were injected dorsally with 0.5 µL of RpII140 dsRNA or Prosα-2 dsRNA at 1000 ng/µL using the IM-11–2 microinjector (Narishige). Control insects were injected with an equivalent amount of GFP dsRNA or nuclease-free water. After the injections, insects were maintained at 27 ± 1 °C, 75 ± 5% relative humidity and fed on pepper. Biological replicates of each treatment were collected three days post-injection. Each biological replicate consisted of one insect. In the feeding bioassay, a droplet consisting of 24 µL of 20% sucrose solution with green food dye containing RpII140 dsRNA or Prosα-2 dsRNA at a concentration of 500 ng/µL was offered to twelve A. eugenii adults placed in a plastic vial. GFP dsRNA and nuclease-free water were used as controls. The droplets were replaced on the third day. Biological replicates consisting of a pool of three insects were collected on the fifth day.

Table 4.

Primers used for dsRNA synthesis.

| Primer | Sequence 5′−3′ | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| RpII140-Ae-ds-F | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGCGGGATGAATCTCACAGT | 334 |

| RpII140-Ae-ds-R | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGCGTCAGATGGACATTATCG | |

| Prosα-2-Ae-ds-F | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGCAACGGAAAATAAACACA | 338 |

| Prosα-2-Ae-ds-R | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTCCATGCAAAGTAAGCTCCA |

Bold letters represent the T7 promoter sequence.

The collected samples from all experimental treatments performed in this study were placed in centrifuge tubes, rapidly flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C until RNA extraction. Each treatment included three biological replicates.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and on-column genomic DNA digestion was performed using the RNase-free DNase Set (Qiagen) as recommended by the manufacturer. RNA samples were quantified by Nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The absence of DNA contamination and the RNA integrity was analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel. Total RNA (500 ng) was reverse transcribed to cDNA using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The cDNA was diluted 50-fold with nuclease-free water for subsequent RT-qPCR assays.

Reverse-transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

The RT-qPCR assays were carried out using a BioRad CFX96 qPCR System (Bio-Rad) with an optical 96-well plate. Each RT-qPCR reaction mix contained 2 μL of cDNA diluted 50×, 5 μL of SsoAdvancedTM Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), 0.2 μL of each primer at 10 μM and 3.6 μL of nuclease-free water for a total volume of 10 μL. Thermal cycling conditions were 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 sec and 60 °C for 30 sec. To assure the specificity of the primers and to eliminate the possibility of primer dimer formation, melting curves ranging from 65 °C to 95 °C with 0.5 °C/5 sec increment were included after amplification. Non-template control (NTC) was used as a negative control for each master mix. Assays were performed with three biological replicates each comprising three technical replicates. The PCR amplification efficiency of the primer pairs was determined from the standard curve generated with 5-fold serial dilutions of cDNA.

Analysis of the stabilities of candidate reference genes

Three algorithms, geNorm accessed as part of the qbase+ analysis software from Biogazelle52 (http://medgen.ugent.be/*jvdesomp/genorm/), NormFinder version 0.95353 (https://www.moma.dk/normfinder-software) and BestKeeper version 154 (https://www.gene-quantification.de/bestkeeper.html) were used to evaluate the expression stability of the candidate reference genes. For NormFinder analyses, Cq values were transformed into non-normalized relative quantities according to the formula: (E)ΔCq where E represents the primer efficiency for each gene and ΔCq represents the lowest Cq value - Cq value of each sample. Raw Cq values were employed in geNorm and BestKeeper analyses. The comprehensive ranking of the reference genes was based on the geometric mean of geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper results.

BestKeeper calculates the standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) based on the Cq values for each candidate reference gene. Genes with SD greater than 1 are considered unstable. It also estimates the BestKeeper Index and then calculates the correlation coefficient (r) between each candidate gene and the BestKeeper index. Genes with higher stability have higher r values. GeNorm evaluates the stability of the potential reference gene based on an “M” value which represents the average pairwise variation of a specific candidate reference gene with all other genes. The genes with the lowest M values are considered the most stably expressed. For homogeneous samples, suitable reference genes should have M values lower than 0.5, but if the samples are considered heterogeneous M values up to 1 are acceptable. GeNorm was used to determine the optimal number of reference genes required for accurate normalization. It calculates the pairwise variation values (Vn/n + 1) between two consecutively ranked normalization factors (NFn and NFn+1), where n is the number of reference genes used in the normalization factor. The stepwise inclusion of the subsequent more stable reference gene can result in an increase or decrease in Vn/n + 1 value and a Vn/n + 1 below 0.15 indicates that the inclusion of an additional reference gene is not necessary for normalization. NormFinder analyzes the intra- and inter-group variations to estimate the stability of each candidate reference gene. Lower stability values indicate higher gene expression stability.

Validation of the reference genes in A. eugenii

The combination of the most stable reference genes (α-TUB and RPL12) in insects treated with dsRNA was validated by evaluating the expression of Prosα-2 and RpII140 genes. The relative expression of the target genes was calculated using the 2− ΔΔCt method55. Three technical and three biological replicates were performed in this analysis. Gene expression data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro 13 Software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SE).

Supplementary information

Selection of reference genes for normalization of RT-qPCR data in gene expression studies in Anthonomus eugenii Cano (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Caitlin Taylor for her assistance with some experiments and Lucile Skelley for providing the insects used in the bioassays.

Author contributions

D.H.P. and B.D.S. conceived and designed the experiments. D.H.P. performed the experiments. D.H.P. performed statistical analysis. D.H.P. and B.D.S. interpreted the data and composed the manuscript. D.H.P. and B.D.S. revised the manuscript.

Data availability

All relevant data analyzed during this study are included in this article and its Supplementary Information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-61739-z.

References

- 1.Wong ML, Medrano JF. Real-time PCR for mRNA quantitation. Biotechniques. 2005;39:75–85. doi: 10.2144/05391RV01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative Ct method. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bustin SA, et al. The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009;55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kozera B, Rapacz M. Reference genes in real-time PCR. J. Appl. Genet. 2013;54:391–406. doi: 10.1007/s13353-013-0173-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.García-Reina A, Rodríguez-García MJ, Galián J. Validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in tiger beetles across sexes, body parts, sexual maturity and immune challenge. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:10743. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28978-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sagri E, et al. Housekeeping in Tephritid insects: the best gene choice for expression analyses in the medfly and the olive fly. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:45634. doi: 10.1038/srep45634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang X, Pan H, Yuan L, Zhou X. Reference gene selection for RT-qPCR analysis in Harmonia axyridis, a global invasive lady beetle. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:2689. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20612-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu Y, et al. Reference genes selection for quantitative gene expression studies in tea green leafhoppers, Empoasca onukii Matsuda. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0205182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basu S, et al. Evaluation of reference genes for real-time quantitative PCR analysis in southern corn rootworm, Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi (Barber) Sci. Rep. 2019;9:10703. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47020-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Brien CW, Wibmer GJ. Annotated checklist of the weevils (Curculionidae sensu lato) of North America, Central America, and the West Indies (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea). Mem. Am. Entomol. Institute, Ann. Arbor, MI. 1982;34:462. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke HR, Woodruff RE. The pepper weevil (Anthonomus eugenii Cano) in Florida (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) Fla. Dept. Agr. Consum. Serv. Entomol. Cir. 1980;2:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrews KL, et al. A supervised control programme for the pepper weevil, Anthonomus eugenii Cano, in Honduras, Central America. Trop. Pest Manag. 1986;32:1–4. doi: 10.1080/09670878609371017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elmore JC, Davis C, Campbell RE. The pepper weevil. USDA Tech. Bull. n. 1934;447:27. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schultz, P. B. & Kuhar, T. P. First record of pepper weevil infestation in Virginia. Plant Health Progress, 10.1094/php-2008-0118-01-br (2008).

- 15.Ingerson-Mahar J, Eichinger B, Holmstrom K. How does pepper weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) become an important pepper pest in New Jersey? J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2015;6:2–8. doi: 10.1093/jipm/pmv022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seal D, Martin C, Seal DR, Martin CG. Pepper weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) preferences for specific pepper cultivars, plant parts, fruit colors, fruit sizes, and timing. Insects. 2016;7:9. doi: 10.3390/insects7010009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Zhang RR, Gao GQ, Ma MY, Chen H. Cold tolerance and silencing of three cold-tolerance genes of overwintering Chinese white pine larvae. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34698. doi: 10.1038/srep34698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meagher R, et al. Mechanism and DNA-based detection of field-evolved resistance to transgenic Bt corn in fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) Sci. Rep. 2017;7:10877. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09866-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mello TRP, et al. Developmental regulation of ecdysone receptor (EcR) and EcR-controlled gene expression during pharate-adult development of honeybees (Apis mellifera) Front. Genet. 2014;5:445–464. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z, Zhou W, Hameed MS, Liu J, Zeng X. Characterization and expression profiling of neuropeptides and g-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) for neuropeptides in the asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:3912. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guénin S, et al. Normalization of qRT-PCR data: The necessity of adopting a systematic, experimental conditions-specific, validation of references. J. Exp. Bot. 2009;60:487–493. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huggett J, Dheda K, Bustin S, Zumla A. Real-time RT-PCR normalisation; strategies and considerations. Genes Immun. 2005;6:279–284. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, et al. Selection and validation of appropriate reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR normalization in staminate and perfect flowers of andromonoecious Taihangia rupestris. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:729. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H-B, et al. Screening potential reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis in the oriental armyworm, Mythimna separata. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pombo MA, et al. Transcriptome-based identification and validation of reference genes for plant-bacteria interaction studies using Nicotiana benthamiana. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1632. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-38247-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacerda ALM, et al. Reference gene selection for qPCR analysis in tomato-bipartite begomovirus interaction and validation in additional tomato-virus pathosystems. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gong H, et al. Evaluation of candidate reference genes for RT-qPCR studies in three metabolism related tissues of mice after caloric restriction. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:38513. doi: 10.1038/srep38513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hossain MS, Ahmed R, Haque MS, Alam MM, Islam MS. Identification and validation of reference genes for real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis in jute. BMC Mol. Biol. 2019;20:13. doi: 10.1186/s12867-019-0130-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen MG, Gadagkar SR, Gutzwiller L. Tubulin evolution in insects: gene duplication and subfunctionalization provide specialized isoforms in a functionally constrained gene family. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010;10:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang C, et al. Selection of reference genes for RT-qPCR analysis in a predatory biological control agent, Coleomegilla maculata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) Sci. Rep. 2016;5:18201. doi: 10.1038/srep18201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arya SK, et al. Reference genes validation in Phenacoccus solenopsis under various biotic and abiotic stress conditions. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:13520. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao Z, Deng W, Zhu F. Reference gene selection for quantitative gene expression analysis in black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) PLoS One. 2019;14:e0221420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagaraj S, Senthil-Kumar M, Ramu VS, Wang K, Mysore KS. Plant ribosomal proteins, RPL12 and RPL19, play a role in nonhost disease resistance against bacterial pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;6:1192. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang C, Pan H, Liu Y, Zhou X. Selection of reference genes for expression analysis using quantitative real-time PCR in the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris) (Hemiptera, Aphidiae) PLoS One. 2014;9:e110454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li K, Xu N, Yang YJ, Zhang JH, Yin H. Identification and validation of reference genes for RT-qPCR normalization in Mythimna separata (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Biomed Res. Int. 2018;2018:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2018/1828253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang PA, Duan JY, Wu HJ, Ju XR, Yuan ML. Reference gene selection to determine differences in mitochondrial gene expressions in phosphine-susceptible and phosphine-resistant strains of Cryptolestes ferrugineus, using qRT-PCR. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:7047. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07430-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bin S, et al. Selection of reference genes for optimal normalization of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction results for Diaphorina citri adults. J. Econ. Entomol. 2018;112:355–363. doi: 10.1093/jee/toy297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lü J, et al. Selection of appropriate reference genes for RT-qPCR analysis in Propylea japonica (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) PLoS One. 2018;13:e0208027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang C, et al. Stable reference gene selection for RT-qPCR analysis in nonviruliferous and viruliferous Frankliniella occidentalis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dai T-M, Lü Z-C, Liu W-X, Wan F-H. Selection and validation of reference genes for qRT-PCR analysis during biological invasions: The thermal adaptability of Bemisia tabaci MED. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lü J, et al. Selection and validation of reference genes for RT-qPCR analysis of the ladybird beetle Henosepilachna vigintioctopunctata. Front. Physiol. 2018;9:1614. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pan H, Yang X, Siegfried BD, Zhou X. A comprehensive selection of reference genes for RT-qPCR analysis in a predatory lady beetle, Hippodamia convergens (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu Y, et al. Identification and validation of reference genes for gene expression analysis using quantitative PCR in Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) PLoS One. 2013;8:e68059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Busato S, Mezzetti M, Logan P, Aguilera N, Bionaz M. What’s the norm in normalization? A frightening note on the use of RT-qPCR in the livestock science. Gene X. 2019;1:100003. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.100003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chapman JR, Waldenström J. With reference to reference genes: A systematic review of endogenous controls in gene expression studies. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu W, et al. Exploring valid reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis in Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2013;9:792–802. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pinheiro DH, Taylor CE, Wu K, Siegfried BD. Delivery of gene-specific dsRNA by microinjection and feeding induces RNAi response in Sri Lanka weevil, Myllocerus undecimpustulatus undatus Marshall. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019;76:936–943. doi: 10.1002/ps.5601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Untergasser A, et al. Primer3Plus, an enhanced web interface to Primer3. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:71–74. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu K, et al. Lethal RNA interference response in the pepper weevil. J. Appl. Entomol. 2019;143:699–705. doi: 10.1111/jen.12644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christiaens O, et al. RNA interference: A promising biopesticide strategy against the African Sweetpotato Weevil Cylas brunneus. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep38836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knorr E, et al. Gene silencing in Tribolium castaneum as a tool for the targeted identification of candidate RNAi targets in crop pests. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:2061. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20416-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vandesompele J, et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:34–1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andersen CL, Jensen JL, Ørntoft TF. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: A model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5245–5250. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pfaffl MW, Tichopad A, Prgomet C, Neuvians TP. Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: BestKeeper – Excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004;26:509–515. doi: 10.1023/B:BILE.0000019559.84305.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Selection of reference genes for normalization of RT-qPCR data in gene expression studies in Anthonomus eugenii Cano (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data analyzed during this study are included in this article and its Supplementary Information files.