Abstract

Background

The decreased life expectancy and care costs of mental disorders could be enormous. However, research that compares mortality and utilization concurrently across the major category of mental disorders is absent. This study investigated all-cause mortality and medical utilization among patients with and without mental disorders, with an emphasis on identifying the psychiatric category of high mortality and low medical utilization.

Methods

A total of 570,250 individuals identified from the 2002–2013 Taiwan National Health Insurance Reearch Database consistuted 285,125 psychiatric patients and 285,125 non-psychiatric peers through 1:1 dual propensity score matching (PSM). The expenditure survival ratio (ESR) was proposed to indicate potential utilization shortage. The category of mental disorders and 13 covariates were analyzed using the Cox proportional hazard model and general linear model (GLM) through SAS 9.4.

Results

PSM analyses indicated that mortality and total medical expenditures per capita were both significantly higher in psychiatric patients than those in non-psychiatric patients (all P <.0.0001). Patients with substance use disorders were reported having the youngest ages at diagnosis and at death, with the highest 25.64 of potential years of life loss (YPLL) and relevant 2904.89 of ESR. Adjusted Cox model and GLM results indicated that, compared with anxiety disorders, affective disorders and substance use disorders were significantly associated with higher mortality (HR = 1.246 and 1.064, respectively; all P < 0.05); schizophrenia was significantly associated with higher total medical expenditures per capita (P < 0.0001). Thirteen additional factors were significantly associated with mortality or utilization (all P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Substance use disorders are the category of highest YPLL but notably in insufficient utilization. Health care utilization in patients with substance use disorders should be augmented timely after the diagnosis, especially toward home and community care. The factors related to mortality and utilization identified by this study merit clinical attention.

Keywords: Category of mental disorders, Mortality, Medical utilization, Potential years of life loss, Expenditure survival ratio

Background

Mental disorders are leading causes of life years with disability worldwide [1]. The high impact on life expectancy of a certain category of mental disorders has been reported by previous studies, such as affective disorders [2, 3], substance use disorders [4], and schizophrenia [1, 5, 6]. The life impacts of such disease require substantial attention. Previous studies have indicated that mental disorders are highly contributed to the death causes of accident and self- inflicted injury [7–9]. According to prior research of mortality in patients with mental disorders, overall survival time after the diagnosis was 36.2 years [10]; average life expectancy (LE) and potential years of life loss (YPLL) among psychiatric patients was 55.5 years and 17.7 years, respectively [11, 12]. Nevertheless, age at the diagnosis of mental disorders highly impacts on the survival time. The survival time was greatly shortened to only 1.32 years among people who first experienced mental illness in age higher than 60 years [13]. Therefore, study of life impacts including survival time, mortality, death age, and YPLL substantiates the necessity of investigation on age at diagnosis.

Mental illness is debilitating because of functional impairment. The health care for psychiatric patients is rather challenging. Prior research has documented that health care expenditures on patients with mental disorders were higher than those on the general population [14]. Average medical expenditure per capita of psychiatric patients and non-psychiatric patients were reported to be 12,358 USD and 7927 USD, respectively [15]. Specifically, the average inpatient expenditure per capita in psychiatric patients was double of that in general public [16]; hospital length of stay in patients with depression disorder was also higher than non-depressive patients [17, 18]. Consequently, patients with mental disorders were likely to become high utilizers of medical care [19]. Use of emergency services, mental health assessment, and psychotherapy specific to psychiatric patients could lead to additional medical expenditures [20, 21].

Severe psychiatric patients with certain characteristics might be related with high mortality and medical expenditures. Previous studies have indicated that dual diagnosis (co-occurring disorders) and involuntary hospitalization, two indications of high psychiatric severity, were linked to a high risk of death [22] and high medical utilization [23]. Moreover, medical comorbidity, such as diabetes and cancer, could lead to higher mortality and medical utilization [24–28]. According to the existing literature, various medications have been linked to high mortality and expenditures, such as haloperidol, tricyclic antidepressants, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors [29, 30]. Overall, clinical severity in this study includes psychiatry-specific indications, namely dual diagnoses and voluntary hospitalization, and other medical characteristics, including comorbidity and medication. The aforementioned four medical characteristics should be included in the analysis.

Most of the population-based studies examined life outcomes between psychiatric and non-psychiatric patients without using a matching method [31–33]. Information on average age at diagnosis, LE, and YPLL for various categories of mental disorders is also lacking. Most psychiatric studies investigated one single type of disorder and reported on either mortality or medical expenditure [18]. Lack of research that investigates both mortality and expenditures using a paired comparison justifies this study. Out of a complete spectrum of mental disorders, which psychiatric category is linked to the high risk of premature death and low medical utilization is obscure. Therefore, the present study investigated the mortality and medical expenditures of the major category of mental disorders by using numerous factors. A certain category of mental disorders with relatively high YPLL and low utilization would be identified.

Methods

Hypothesis and research design

This study hypothesized that mortality and medical utilization were associated with various factors including health and medication characteristics, demographic characteristics, provider characteristics, and geographic characteristics. The presence and category of mental disorders were considered as the key factors. A longitudinal retrospective population-based design was used to examine the hypothesis by analyzing nationwide data of psychiatric patients versus matched non-psychiatric patients in Taiwan. The current study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee at China Medical University and Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan, under no. CMUH105-REC3–016.

Data source and study sample

The Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) program was launched in 1995 and covers more than 99.7% of 23.74 million people in Taiwan [1]. Both grants funded by China Medical University and the Ministry of Science and Technology provided support to obtain the study data, which were retrieved from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), which contains the registration files and medical claims data including ambulatory and inpatient care for one million randomly sampled NHI beneficiaries from 2002 to 2013.

The diagnostic codes 290.x–319.x of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) were used to identify psychiatric patients. Patients with only one time of psychiatric diagnosis were excluded from the study to ensure a reliable identification of cases. Furthermore, to ascertain that study patients were newly diagnosed with mental disorders, those diagnosed with mental disorders in 2002 were excluded from the study. Consequently, 285,125 patients with mental disorders (study group) were matched with 285,125 counterparts without mental disorders (control group) at a 1:1 ratio according to a propensity score [34]. The matched variables included gender, age, comorbidity, urbanization level, and index date of diagnosis. After the use of the propensity score matching method, the selection bias was reduced and the similarity between the two groups was substantially enhanced [2–4].

Variables

The outcome variables included all-cause death and medical utilization, both of which were observed in the period of 2003 to 2013. Death was defined dichotomously, whereas medical utilization was represented by a continuous measure of total medical expenditures per capita (in USD; exchange rate of 1 USD to 30 TWD as of November 6, 2019) comprising ambulatory and inpatient claims. The two major independent variables were the presence of mental disorders and the category of mental disorders. The presence of mental disorders was defined as claims with main diagnosis codes of 290.x–319.x [35]. Based on previous studies and frequency distributions, patients with mental disorders were classified into the following five categories: affective disorders (296.xx), anxiety disorders (300.xx, 308.3, and 309.81), substance use disorders (303.xx, 304.xx, and 305.xx), schizophrenia (295.xx), and other (the remaining codes) [36–38]. The category of mental disorders was determined on the diagnosis code of a mental disorder that occurred first (with a 1-year observation window of non-mental disorder claims) in 2003 and had at least two mental disorder claims within 6 months of first occurrence for a patient to ensure a reliable classification.

In addition to the presence of mental disorders and the category of mental disorders, based on the existing studies, the present research included the following four groups of characteristics that were possibly related to mortality and utilization among patients with mental disorders: 1. Health and medication characteristics: multiple diagnoses [22], involuntary hospitalization [23], comorbidity [28], and use of psychiatric medication [30]; 2. Demographic characteristics: gender [5], age [6], occupation [39], and premium-based monthly salary [40]; 3. Provider characteristics: level of hospital [41], ownership of hospital [41], and seniority of care psychiatrist [42]; 4. Geographic characteristics: region and urbanization level [43]. Among the five categories of mental disorders defined in this study, when a patient underwent more than one category during the observation period of 2003 to 2013, multiple diagnoses would be coded present; otherwise, absent. Comorbidity was measured using the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [44], a frequently used instrument in clinical research. Psychiatric medications were categorized from frequently used drugs in the treatments for patients with mental disorders. The seniority of major care psychiatrist for a patient in this study was classified into four levels on the basis of frequency distribution. Urbanization level was graded on a seven-level scale, with levels 1 and 7 indicating the highest and lowest urbanization levels, respectively. The rest of the variables were defined according to the official classifications of the registry for NHI beneficiaries and the medical claims. All the 15 independent variables were measured in a categorical or an ordinal level.

Statistical analysis

The statistical methods in this study included the chi-square test, survival analysis, and general linear model (GLM). The chi-squared test was used to report the prevalence rates of all-cause death among patients with mental disorders in bivariate analysis. Cox proportional hazard model was used to estimate the risks of all-cause death during the 11-year observation period, with the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) being reported. GLM was selected to test the mean differences in total medical expenditures per capita because of its capacity for the estimation of means (least squares means) for each level of the independent variables when adjusting all other covariates [45]. Furthermore, derived from the concept of survival ratio reported by a previous study [46], a standardized measure, expenditure survival ratio (ESR) was proposed to represent medical expenditures invested per survival time. When the medical expenditure is similar, shorter survival time entails larger ESR, which potentially implying the effect of insufficient utilization on life outcome. Moreover, collinearity diagnostics was conducted using indices including tolerance and variance inflation. Data were analyzed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

The result of the 1:1 propensity score matching indicated no differences in the five matched variables, including gender, age, comorbidity, urbanization level, and index date of diagnosis, between patients with and without mental disorders (all P = 1), confirming that the two groups (285,125 versus 285,125, Table 1) were eligible for the comparisons. Furthermore, this study did not detect significant signs of collinearity. Propensity-matched analysis indicated that, after adjustment for all other covariates, the odds of all-cause death were significantly higher in patients with mental disorders than in those without mental disorders (HR = 1.150, 95% CI = 1.127–1.175, P < 0.0001). The estimated mean of total medical expenditures per capita in patients with mental disorders was also significantly higher than that in patients without such disorders (18,455.43 versus 14,248.66, P < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Propensity score-matched comparisons of mortality and total medical expenditures per capita between patients with and without mental disorders, controlling for all other variables (Cox proportional hazard model and GLM, N = 570,250)

| Variables | n | % | Death | P-value | Mean of total medical expenditures (USD) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR | 95% CI | ||||||

| Mental disorders | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | |||||

| Present | 285,125 | 50.00 | 1.150 | 1.127–1.175 | 18,455.43 | ||

| Absent | 285,125 | 50.00 | – | – | 14,248.66 | ||

* P < 0.05

HR hazard ratio

Other variables in the models included: comorbidity, gender, age, occupation, premium-based monthly salary, level of hospital, ownership of hospital, seniority of care physician, region, and urbanization level.

The chi-square test results indicated that the category of mental disorders was significantly associated with the risk of death (Table 2, P < 0.0001). Among the five psychiatric categories, the mortality was higher in schizophrenia and affective disorders (11.67 and 10.67%, respectively). All other 13 independent variables were significantly associated with the mortality of psychiatric patients (all P < 0.05). Specifically, other health and medication characteristics significantly associated with a higher likelihood of death included the presence of multiple diagnoses (8.73%), the presence of involuntary hospitalization (12.89%), CCI ≥ 2 (29.40%), and use of multiple categories of psychiatric medication (13.89%).

Table 2.

Mortality of psychiatric patients, by the category of mental disorders and other characteristics (Chi-square test, N = 285,125)

| Variables | Frequency | % | Death | No death | χ2 P-value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n1 | % | n2 | % | ||||

| 23,136 | 8.11 | 261,989 | 91.89 | ||||

| Health and Medication Conditions | |||||||

| Category of mental disorders | < 0.0001* | ||||||

| Affective disorders | 17,608 | 6.18 | 1879 | 10.67 | 15,729 | 89.33 | |

| Anxiety disorders | 136,642 | 47.92 | 8636 | 6.32 | 128,006 | 93.68 | |

| Substance use disorders | 22,830 | 8.01 | 1983 | 8.69 | 20,847 | 91.31 | |

| Schizophrenia | 1662 | 0.58 | 194 | 11.67 | 1468 | 88.33 | |

| Other disorders | 106,383 | 37.31 | 10,444 | 9.82 | 95,939 | 90.18 | |

| Multiple diagnoses | < 0.0001* | ||||||

| Present | 95,345 | 33.44 | 8320 | 8.73 | 87,025 | 91.27 | |

| Absent | 189,780 | 66.56 | 14,816 | 7.81 | 174,964 | 92.19 | |

| Involuntary hospitalization | 0.0051* | ||||||

| Present | 256 | 0.09 | 33 | 12.89 | 233 | 87.11 | |

| Absent | 284,869 | 99.91 | 23,103 | 8.11 | 261,766 | 91.89 | |

| Comorbidity (CCI) | < 0.0001* | ||||||

| 0 | 182,941 | 64.16 | 7142 | 3.90 | 175,799 | 96.10 | |

| 1 | 89,485 | 31.38 | 12,261 | 13.70 | 77,224 | 86.30 | |

| ≥ 2 | 12,699 | 4.45 | 3733 | 29.40 | 8966 | 70.60 | |

| Use of psychiatric medication | < 0.0001* | ||||||

| Mood stabilizer | 95,758 | 33.58 | 8719 | 9.11 | 87,039 | 90.89 | |

| Antidepressants | 9078 | 3.18 | 605 | 6.66 | 8473 | 93.34 | |

| Antipsychotics | 8269 | 2.90 | 956 | 11.56 | 7313 | 88.44 | |

| Multiple categories | 47,170 | 16.54 | 6550 | 13.89 | 40,620 | 86.11 | |

| None | 124,850 | 43.79 | 6306 | 5.05 | 118,544 | 94.95 | |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Gender | < 0.0001* | ||||||

| Male | 131,097 | 45.98 | 13,587 | 10.36 | 117,510 | 89.64 | |

| Female | 154,027 | 54.02 | 9549 | 6.20 | 144,478 | 93.80 | |

| Age (years) | < 0.0001* | ||||||

| < 19 | 222,77 | 7.81 | 142 | 0.64 | 22,135 | 99.36 | |

| 20–34 | 50,083 | 17.57 | 943 | 1.88 | 49,140 | 98.12 | |

| 35–49 | 72,599 | 25.46 | 2546 | 3.51 | 70,053 | 96.49 | |

| 50–64 | 75,812 | 26.59 | 3463 | 4.57 | 72,349 | 95.43 | |

| ≥ 65 | 64,354 | 22.57 | 16,042 | 24.93 | 48,312 | 75.07 | |

| Occupationa | < 0.0001* | ||||||

| First category | 152,681 | 53.55 | 9215 | 6.04 | 143,466 | 93.96 | |

| Second category | 63,142 | 22.15 | 3736 | 5.92 | 59,406 | 94.08 | |

| Third category | 40,454 | 14.19 | 6170 | 15.25 | 34,284 | 84.75 | |

| Fourth category | 1078 | 0.38 | 67 | 6.22 | 1011 | 93.78 | |

| Fifth category | 1228 | 0.43 | 217 | 17.67 | 1011 | 82.33 | |

| Sixth category | 26,542 | 9.31 | 3731 | 14.06 | 22,811 | 85.94 | |

| Premium-based monthly salary (USD) | < 0.0001* | ||||||

| ≤ 576 | 163,453 | 57.33 | 12,014 | 7.35 | 151,439 | 92.65 | |

| 576–760 | 77,404 | 27.15 | 8891 | 11.49 | 68,513 | 88.51 | |

| 760–960 | 10,790 | 3.78 | 566 | 5.25 | 10,224 | 94.75 | |

| 960–1210 | 11,801 | 4.14 | 714 | 6.05 | 11,087 | 93.95 | |

| 1210–1526 | 10,177 | 3.57 | 513 | 5.04 | 9664 | 94.96 | |

| > 1526 | 11,500 | 4.03 | 438 | 3.81 | 11,062 | 96.19 | |

| Provider Features | |||||||

| Level of hospital | < 0.0001* | ||||||

| Medical center | 45,470 | 17.11 | 4131 | 9.09 | 41,339 | 90.91 | |

| Regional hospital | 70,237 | 26.42 | 6875 | 9.79 | 63,362 | 90.21 | |

| District hospital | 34,245 | 12.88 | 4307 | 12.58 | 29,938 | 87.42 | |

| Clinic | 115,852 | 43.59 | 6154 | 5.31 | 109,698 | 94.69 | |

| Ownership of Hospital | < 0.0001* | ||||||

| Public | 51,920 | 18.26 | 5742 | 11.06 | 46,178 | 88.94 | |

| Private | 157,478 | 55.37 | 10,565 | 6.71 | 146,913 | 93.29 | |

| Consortium | 67,277 | 23.66 | 5809 | 8.63 | 61,468 | 91.37 | |

| Association | 7733 | 2.72 | 675 | 8.73 | 7058 | 91.27 | |

| Psychiatrist’s year of practice | < 0.0001* | ||||||

| ≤ 5 | 74,789 | 26.23 | 4469 | 5.98 | 70,320 | 94.02 | |

| 6–10 | 103,619 | 36.34 | 8545 | 8.25 | 95,074 | 91.75 | |

| 11–15 | 49,063 | 17.21 | 4864 | 9.91 | 44,199 | 90.09 | |

| ≥ 16 | 57,654 | 20.22 | 5258 | 9.12 | 52,396 | 90.88 | |

| Geographic Characteristics | |||||||

| Region | < 0.0001* | ||||||

| Taipei | 102,630 | 36.25 | 7279 | 7.09 | 95,351 | 92.91 | |

| Northern | 34,842 | 12.30 | 2854 | 8.19 | 91,988 | 91.81 | |

| Central | 54,734 | 19.33 | 4343 | 7.93 | 50,391 | 92.07 | |

| Southern | 40,425 | 14.28 | 3837 | 9.49 | 36,588 | 90.51 | |

| Southeast | 43,345 | 15.31 | 3865 | 8.92 | 39,840 | 91.08 | |

| Eastern | 7178 | 2.54 | 776 | 10.81 | 6402 | 89.19 | |

| Urbanization level | < 0.0001* | ||||||

| Level 1 (Highest) | 84,967 | 30.20 | 5635 | 6.63 | 79,332 | 93.37 | |

| Level 2 | 82,327 | 29.26 | 6127 | 7.44 | 76,200 | 92.56 | |

| Level 3 | 47,269 | 16.80 | 3758 | 7.95 | 43,511 | 92.05 | |

| Level 4 | 39,430 | 14.02 | 3884 | 9.85 | 35,546 | 90.15 | |

| Level 5 | 7076 | 2.52 | 870 | 12.30 | 6206 | 87.70 | |

| Level 6 | 11,050 | 3.93 | 1453 | 13.15 | 9597 | 86.85 | |

| Level 7 (Lowest) | 9214 | 3.28 | 1096 | 11.89 | 8118 | 88.11 | |

a First category includes private employees and public servants; Second category includes labor union members; Third category includes farmers and fishermen; Fourth category includes soldiers; Fifth category includes social security insureds; Sixth category includes veterans and religious group members

Table 3 lists the means for age at diagnosis of mental disorders, survival time, age at death, YPLL, and ESR, respectively, for the five categories of psychiatric patients who died in the observation period of 2003 to 2013. Among the five categories, patients with substance use disorders experienced the disease and died both earliest at the age of 51.38 and 54.38 years, respectively. Accordingly, substance use disorders were reported with the highest YPLL of 25.64 years, the ESR for substance use disorders was 2904.89, which is in concordance with the YPLL results. The GLM test results indicated significant differences in ESR between the categories of mental disorders (P < 0.0001). Schizophrenia and anxiety disorders have the highest and lowest average ESRs of 12,183.39 and 1236.34 among the five categories of mental disorders.

Table 3.

Average potential years of life loss and expenditure survival ratio in patients with mental disorders, by the category of mental disorders (Descriptive statistics and GLM, N = 23,136)

| Category of mental disorders | Age at diagnosis | Survival time | Age at death | YPLL | Expenditure survival ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective disorders | 61.15 | 2.72 | 63.87 | 16.15 | 5411.26 |

| Anxiety disorders | 63.91 | 3.32 | 67.23 | 12.79 | 1236.34 |

| Substance use disorders | 51.38 | 3.00 | 54.38 | 25.64 | 2904.89 |

| Schizophrenia | 55.70 | 2.90 | 58.60 | 21.42 | 12,183.39 |

| Other disorders | 71.90 | 2.60 | 74.50 | 5.52 | 2307.80 |

YPLL was calculated on the reference age of 80.02 years (LE) for the Taiwanese population in 2013.

Expenditure survival ratio was estimated using multivariate GLM (P < 0.0001).

Table 4 presents the results of multivariate analyses for all-cause mortality and total medical expenditures per capita among patients with mental disorders. Anxiety disorders were used as the reference group for the category of mental disorders in the Cox model because of the lowest death rate (6.32%) among the categories. The adjusted Cox model results indicated that the category of mental disorders was significantly associated with the risk of death (all P < 0.05). Compared with patients with anxiety disorders, patients with affective disorders, substance use disorders, and other mental disorders were more likely to die (HR = 1.246, 1.064, and 1.233, respectively). When all other variables were constant, the other significant factors related to the risk of death among patients with mental disorders included multiple diagnoses, comorbidity, use of psychiatric medication, gender, age, occupation, premium-based monthly salary, level of hospital, ownership of hospital, seniority of care psychiatrist, region, and urbanization level (all P < 0.05). The high risk of death was associated with the following main characteristics: the absence of multiple diagnoses, CCI ≥ 2, use of antipsychotics, male, high ages, social security insureds, income between $760 and $960, regional hospitals, association-owned hospitals, psychiatrist seniority ≤10 years, southern and eastern regions, and lowest level of urbanization. Furthermore, information regarding death per 1000 person-days was listed in Table 4. Among the five categories of mental disorders, schizophrenia was associated with the highest death rate per 1000 person-days (P = 0.0685). Moreover, after adjustment for all other covariates, the GLM test results indicated significant means differences in total medical expenditures per capita between the categories of mental disorders (P < 0.0001). Schizophrenia was ranked the highest in total medical expenditures per capita with the estimation of USD 29,748.05. Ten other factors associated with mean differences in the medical expenditures included multiple diagnoses, involuntary hospitalization, use of psychiatric medication, gender, age, occupation, premium-based monthly salary, level of hospital, ownership of hospital, and seniority of care psychiatrist (all P < 0.05). Other characteristics associated with high averaged total medical expenditures per capita included the presence of multiple diagnoses, the presence of involuntary hospitalization, use of multiple categories of psychiatric medication, male, age ≥ 65, social security insureds, income ≤576, medical centers, public hospitals, and seniority of care psychiatrist ≥16 years.

Table 4.

Association between the category of mental disorders, mortality, and total medical expenditures per capita, controlling for all other variables (Cox proportional hazard model and GLM, N = 285,125)

| Variables | Death per 1000 person-days | Death | P-value | Mean of total medical expenditures (USD) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR | 95% CI | |||||

| Health and Medication Conditions | ||||||

| Category of mental disorders | < 0.0001* | |||||

| Affective disorders | 0.0617 | 1.246 | 1.180–1.316 | < 0.0001* | 15,791.06 | |

| Anxiety disorders | 0.0335 | – | – | – | 12,618.92 | |

| Substance use disorders | 0.0500 | 1.064 | 1.009–1.122 | 0.0231* | 13,307.55 | |

| Schizophrenia | 0.0685 | 1.072 | 0.923–1.245 | 0.3646 | 29,748.05 | |

| Other disorders | 0.0546 | 1.233 | 1.195–1.271 | < 0.0001* | 13,016.03 | |

| Multiple diagnoses | < 0.0001* | |||||

| Present | 0.0488 | – | – | – | 17,275.36 | |

| Absent | 0.0421 | 1.095 | 1.062–1.130 | < 0.0001* | 16,517.29 | |

| Involuntary hospitalization | < 0.0001* | |||||

| Present | 0.0892 | – | – | – | 28,345.00 | |

| Absent | 0.0443 | 1.417 | 0.988–2.032 | 0.0579 | 5447.64 | |

| Comorbidity (CCI) | 0.4944 | |||||

| 0 | 0.0212 | – | – | – | 16,887.48 | |

| 1 | 0.0744 | 1.004 | 0.970–1.040 | 0.8134 | 16,869.13 | |

| ≥ 2 | 0.1825 | 1.178 | 1.126–1.233 | < 0.0001* | 16,932.35 | |

| Use of psychiatric medication | < 0.0001* | |||||

| Mood stabilizer | 0.0503 | 1.061 | 1.025–1.098 | 0.0007* | 16,743.08 | |

| Antidepressants | 0.0365 | 1.057 | 0.968–1.153 | 0.2169 | 16,357.20 | |

| Antipsychotics | 0.0579 | 1.237 | 1.152–1.330 | < 0.0001* | 16,591.78 | |

| Multiple categories | 0.0763 | – | – | – | 18,354.09 | |

| None | 0.0274 | 1.213 | 1.166–1.261 | < 0.0001* | 16,435.46 | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Gender | < 0.0001* | |||||

| Male | 0.0578 | 1.039 | 1.009–1.069 | 0.0104* | 17,058.96 | |

| Female | 0.0333 | – | – | – | 16,733.68 | |

| Age (years) | < 0.0001* | |||||

| < 19 | 0.0035 | – | – | – | 16,905.26 | |

| 20–34 | 0.0105 | 1.760 | 1.460–2.122 | < 0.0001* | 16,768.65 | |

| 35–49 | 0.0187 | 2.143 | 1.789–2.567 | < 0.0001* | 16,892.76 | |

| 50–64 | 0.0238 | 1.915 | 1.598–2.294 | < 0.0001* | 16,847.92 | |

| ≥ 65 | 0.1458 | 1.809 | 1.514–2.162 | < 0.0001* | 17,067.00 | |

| Occupationa | < 0.0001* | |||||

| First category | 0.0327 | 1.073 | 1.021–1.127 | 0.0053* | 16,757.76 | |

| Second category | 0.0318 | – | – | – | 16,719.60 | |

| Third category | 0.0847 | 1.066 | 1.011–1.124 | 0.0180* | 16,749.59 | |

| Fourth category | 0.0338 | 1.058 | 0.817–1.371 | 0.6670 | 16,464.26 | |

| Fifth category | 0.1031 | 1.193 | 1.029–1.382 | 0.0190* | 17,809.09 | |

| Sixth category | 0.0814 | 1.065 | 1.003–1.130 | 0.0400* | 16,877.63 | |

| Premium-based monthly salary (USD) | < 0.0001* | |||||

| ≤ 576 | 0.0407 | 1.095 | 0.987–1.214 | 0.0857 | 17,166.44 | |

| 576–760 | 0.0622 | 1.079 | 0.967–1.205 | 0.1755 | 17,050.43 | |

| 760–960 | 0.0277 | 1.185 | 1.038–1.352 | 0.0119* | 16,888.68 | |

| 960–1210 | 0.0322 | 1.064 | 0.938–1.208 | 0.3322 | 16,879.77 | |

| 1210–1526 | 0.0264 | 1.024 | 0.895–1.171 | 0.7319 | 16,713.87 | |

| > 1526 | 0.0198 | – | – | – | 16,678.74 | |

| Provider Features | ||||||

| Level of hospital | < 0.0001* | |||||

| Medical center | 0.0478 | 1.123 | 1.068–1.181 | < 0.0001* | 17,468.25 | |

| Regional hospital | 0.0550 | 1.200 | 1.146–1.256 | < 0.0001* | 17,110.40 | |

| District hospital | 0.0644 | 1.101 | 1.056–1.148 | < 0.0001* | 16,871.55 | |

| Clinic | 0.0295 | – | – | – | 16,135.08 | |

| Ownership of Hospital | < 0.0001* | |||||

| Public | 0.0625 | 1.013 | 0.972–1.056 | 0.5297 | 17,341.45 | |

| Private | 0.0359 | – | – | – | 16,581.21 | |

| Consortium | 0.0464 | 1.012 | 0.968–1.058 | 0.6082 | 16,605.31 | |

| Association | 0.0669 | 1.139 | 1.044–1.243 | 0.0035* | 17,057.32 | |

| Psychiatrist’s year of practice | < 0.0001* | |||||

| ≤ 5 | 0.0484 | 1.709 | 1.629–1.793 | < 0.0001* | 16,838.19 | |

| 6–10 | 0.0436 | 1.237 | 1.193–1.283 | < 0.0001* | 16,843.31 | |

| 11–15 | 0.0445 | 1.020 | 0.980–1.062 | 0.3206 | 16,938.61 | |

| ≥ 16 | 0.0423 | – | – | – | 16,965.18 | |

| Geographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Region | 0.1356 | |||||

| Taipei | 0.0388 | – | – | – | 16,906.41 | |

| Northern | 0.0455 | 1.009 | 0.959–1.062 | 0.7265 | 16,897.61 | |

| Central | 0.0433 | 1.028 | 0.982–1.076 | 0.2401 | 16,819.57 | |

| Southern | 0.0516 | 1.087 | 1.036–1.142 | 0.0008* | 16,891.88 | |

| Southeast | 0.0480 | 1.014 | 0.970–1.061 | 0.5367 | 16,878.81 | |

| Eastern | 0.0617 | 1.141 | 1.043–1.247 | 0.0038* | 16,983.65 | |

| Urbanization level | 0.7318 | |||||

| Level 1 (Highest) | 0.0361 | 1.063 | 0.976–1.158 | 0.1597 | 16,906.04 | |

| Level 2 | 0.0405 | 1.080 | 0.996–1.171 | 0.0636 | 16,912.38 | |

| Level 3 | 0.0435 | 1.069 | 0.984–1.161 | 0.1131 | 16,921.85 | |

| Level 4 | 0.0541 | 1.050 | 0.970–1.136 | 0.2301 | 16,851.65 | |

| Level 5 | 0.0688 | – | – | – | 16,928.21 | |

| Level 6 | 0.0730 | 1.081 | 0.989–1.182 | 0.0855 | 16,872.15 | |

| Level 7 (Lowest) | 0.0645 | 1.114 | 1.013–1.224 | 0.0264* | 16,881.97 | |

* P < 0.05

HR hazard ratio

a First category includes private employees and public servants; Second category includes labor union members; Third category includes farmers and fishermen; Fourth category includes soldiers; Fifth category includes social security insureds; Sixth category includes veterans and religious group members

Discussion

Mental disorders in higher mortality and utilization

Through PSM, the higher mortality and utilization in patients with mental disorders were identified, warranting more attention throughout the disease course. The high rate of all-cause deaths among patients with mental disorders could be engendered by the higher risk of suicide [47, 48] and road traffic accidents [49] because of potentially emotional or cognitive instability leading to unnatural deaths [9]. From the perspective of comorbidity, psychosomatic susceptibility and pathological changes might lead to the potential bidirectional relationship between mental disorders and cancer [50], thus increasing the mortality of this vulnerable population [51]. Furthermore, certain psychiatric medications that slow down metabolism could increase body weight and further contribute to the developments of endocrine disorders and cardiovascular diseases [52, 53]. The psychophysiological conditions of psychiatric patients are closely related to the subsequently high mortality and medical expenditure per capita determined. The finding that total medical expenditures per capita in patients with mental disorders were higher than those in general population is consistent with a previous study [14].

Affective disorders and substance use disorders in higher mortality

This study identified that affective disorders, substance use disorders, and other disorders had higher mortality rate. Indicated by a previous study, the mortality of anxiety disorders was relatively low, compared with that of affective disorders [54]. However, the high rate of suicides resulted in the high mortality among patients with affective disorders [55], with the YPLL of 11 to 20 years reported by prior research [6]. Furthermore, substance use disorders might increase the risk of traffic accidents [56, 57]. Notably, instead of natural causes of death, severe driver injuries in patients with substance use disorders could lead to a loss of 25 years in LE [58] that mirrors the finding of YPLL at 25.64 years in this study. Physio-psychological impairment and decreased level of consciousness induced by substance use as well as poor compliance with treatments are highly life-threatening [59] and thus merit policy emphasis.

Substance use disorders in higher YPLL but in lower utilization

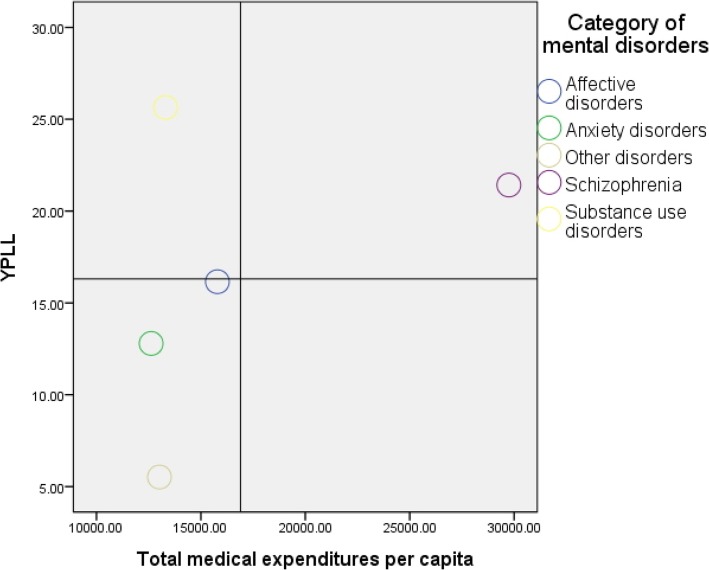

The averaged medical expenditures in patients with schizophrenia were estimated (USD. 29,748.05) to be almost double of those in patients with all other categories, which is similar to the finding of a previous study [60]. However, the mortality estimated in HR for patients with schizophrenia was not the highest among all the psychiatric patients. Furthermore, in a broader consideration of life impacts, ESR carries clinical and policy implications. Substance use disorders, with the earliest onset age and youngest death age, produced the notable ESR of 2904.89, which indicates a room for incremental utilization in terms of premature death. Figure 1 depicts the scatterplots by the two dimensions of YPLL and total medical expenditures per capita for the five categories of mental disorders. According to the classification in this graph, substance use disorders are the only category that falls into the quadrant of high YPLL and low medical expenditures. Substance use disorders are related to a variety of medical treatment, family, and social problems. In view of effects of substance use disorders on the family, effective interventions and mutual support programs involving engagement of the family members are crucial [61]. Therefore, in addition to acute care in hospitals, decision-makers should re-allocate health care resources into a non-acute health network involving home and community-based services (HCBS) where patients with substance use disorders reside to form a more comprehensive safeguard that should be launched timely after the diagnosis of substance use disorders.

Fig. 1.

Scatterplots of YPLL and total medical expenditures per capita for the five categories of mental disorders

Other factors related to mortality and utilization merit medical attention

Other characteristics associated with high mortality among patients with mental disorders, such as CCI ≥ 2, use of antipsychotics, and low seniority of care psychiatrist, deserve more clinical attention and require further research. The improvement of life outcomes among patients with mental disorders should focus on early prevention for the risk of comorbid physical illnesses [62]. Moreover, the identified additional characteristics related to high medical expenditures are supported by the evaluated need component of the well-known health care utilization behavioral model [63], such as multiple diagnoses, involuntary hospitalization, use of multiple categories of psychiatric medication, and the lowest income bracket because of easy access to health care under NHI. Extant studies that investigated the various factors of medical expenditures are scarce. These findings on expenditures are valuable to the field of health services administration. Further scrutiny is required on the associations of low seniority–high mortality and high seniority–high utilization because the two links may intriguingly imply the necessity of human resources strategy concerning clinical performance. Overall, a majority of the related predictors performed differently in mortality and utilization.

The limitations of the current study stem from the NHIRD used. First, the NHIRD encompasses only government-reimbursed data, representing the majority of medical utilization. Self-provided medical items are not included in the database; thus, extrapolation of the study findings to other medical circumstances requires deliberation. Second, the NHIRD used does not contain data pertaining to education, marital status, and lifestyle, thus limiting further analysis in this study. Nevertheless, this study fully utilized all obtainable data for analysis. Finally, based on existing literature and frequency distributions, this study analyzed for the five major categories of mental disorders. Other category of mental disorders could not be further classified in this study. Future related research should concentrate on mortality and utilization for minor categories.

Conclusions

Among the five categories of mental disorders, patients with schizophrenia faced the highest death rate and used medical resources the most. However, this study identified patients with substance use disorders as the vulnerable group of the highest YPLL but with substantially insufficient medical utilization, highlighting a noteworthy health disparity. Policy-makers should strengthen access to health care among patients with substance use disorders, especially HCBS, and intervene timely in the high-risk patients using the mortality related factors identified by this study. The present study suggests that life impacts and medical utilization should be investigated concurrently for a comprehensive analysis in order to improve the welfare of patients with mental disorders.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Taiwan National Health Research Institutes for providing the NHIRD.

Abbreviations

- CCI

Charlson comorbidity index

- CI

Confidence interval

- ESR

Expenditure survival ratio

- GLM

General linear model

- HCBS

Home and community-based services

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- LE

Life expectancy

- NHI

National Health Insurance

- NHIRD

National Health Insurance Research Database

- YPLL

Years of life loss

Authors’ contributions

JYW conceived the research idea, designed the study, and wrote the results, CCC revised the manuscript, MCL assisted in the literature review and analysis, YJL wrote and proofread the manuscript, contributed to the discussion, and prepared the manuscript for submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by China Medical University, Taiwan (Grant No. CMU107-S-18 and CMU107-Z-04) and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (Grant No. MOST105–2410-H-039-008-MY2).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee at China Medical University and Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan, under no. CMUH105-REC3–016. Dr. Jong-Yi Wang granted the administrative permissions to access the raw data.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cheng SH, Chen CC, Tsai SL. The impacts of DRG-based payments on health care provider behaviors under a universal coverage system: a population-based study. Health Policy. 2012;107:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat. 1985;39:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dehejia RH, Wahba S. Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Rev Econ Stat. 2002;84:151–161. doi: 10.1162/003465302317331982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin PC. A comparison of 12 algorithms for matching on the propensity score. Stat Med. 2014;33:1057–1069. doi: 10.1002/sim.6004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohnert KM, Ilgen MA, Louzon S, McCarthy JF, Katz IR. Substance use disorders and the risk of suicide mortality among men and women in the US Veterans Health Administration. Addiction. 2017;112:1193–1201. doi: 10.1111/add.13774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laursen TM, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, Westman J, Ösby U, Alinaghizadeh H, Gissler M, Nordentoft M. Life expectancy and death by diseases of the circulatory system in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in the Nordic countries. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castagnini A, Foldager L, Bertelsen A. Excess mortality of acute and transient psychotic disorders: comparison with bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;128:370–375. doi: 10.1111/acps.12077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatt M, Perera S, Zielinski L, Eisen RB, Yeung S, El-Sheikh W, DeJesus J, Rangarajan S, Sholer H, Iordan E, Mackie P, Islam S, Dehghan M, Thabane L, Samaan Z. Profile of suicide attempts and risk factors among psychiatric patients: a case-control study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Large M, Myles N, Myles H, Corderoy A, Weiser M, Davidson M, Ryan CJ. Suicide risk assessment among psychiatric inpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of high-risk categories. Psychol Med. 2018;48:1119–1127. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717002537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Capasso RM, Lineberry TW, Bostwick JM, Decker PA, St Sauver J. Mortality in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: an Olmsted County, Minnesota cohort: 1950–2005. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nordentoft M, Wahlbeck K, Hallgren J, Westman J, Osby U, Alinaghizadeh H, Gissler M, Laursen TM. Excess mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270,770 patients with recent onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PLoS One. 2013;8:55176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wahlbeck K, Westman J, Nordentoft M, Gissler M, Laursen TM. Outcomes of Nordic mental health systems: life expectancy of patients with mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2011;199:453–458. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flint AJ, Rifat SL. Two-year outcome of psychotic depression in late life. Am J Psychiatr. 1998;155:178–183. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiavegatto Filho ADP, Wang Y-P, Campino AC, Malik AM, Viana MC, Andrade LH. Incremental health expenditure and lost days of normal activity for individuals with mental disorders: results from the São Paulo megacity study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:745. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han X, Lin CC, Li C, de Moor JS, Rodriguez JL, Kent EE, Forsythe LP. Association between serious psychological distress and health care use and expenditures by cancer history. Cancer. 2015;121:614–622. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Menil VP, Knapp M, McDaid D, Njenga FG. Service use, charge, and access to mental healthcare in a private Kenyan inpatient setting: the effects of insurance. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowan P, Davidson K, Campbell J, Dobrez DG, MacLean DR. Depressive symptoms predict medical care utilization in a population-based sample. Psychol Med. 2002;32:903–908. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702005767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mausbach BT, Irwin SA. Depression and healthcare service utilization in patients with cancer. Psychooncology. 2017;26:1133–1139. doi: 10.1002/pon.4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson RL, Grabner M, Palli SR, Faries D, Stephenson JJ. Covariates of depression and high utilizers of healthcare: impact on resource use and costs. J Psychosom Res. 2016;85:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schweickhardt A. Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trivedi TK, Glenn M, Hern G, Schriger DL, Sporer KA. Emergency medical services use among patients receiving involuntary psychiatric holds and the safety of an out-of-hospital screening protocol to “medically clear” psychiatric emergencies in the field, 2011 to 2016. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.08.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arias F, Szerman N, Vega P, Mesías B, Basurte I, Rentero D. Bipolar disorder and substance use disorders. Madrid study on the prevalence of dual disorders/pathology. Adicciones. 2017;29:186–194. doi: 10.20882/adicciones.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reeves E, Henshall C, Hutchinson M, Jackson D. Safety of service users with severe mental illness receiving inpatient care on medical and surgical wards: a systematic review. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27:46–60. doi: 10.1111/inm.12426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baumeister H, Haschke A, Munzinger M, Hutter N, Tully PJ. Inpatient and outpatient costs in patients with coronary artery disease and mental disorders: a systematic review. BioPsychoSocial Medicine. 2015;9:11. doi: 10.1186/s13030-015-0039-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ducat L, Philipson LH, Anderson BJ. The mental health comorbidities of diabetes. JAMA. 2014;312:691–692. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kisely S, Forsyth S, Lawrence D. Why do psychiatric patients have higher cancer mortality rates when cancer incidence is the same or lower? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:254–263. doi: 10.1177/0004867415577979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kao LT, Liu SP, Lin HC, Lee HC, Tsai MC, Chung SD. Poor clinical outcomes among pneumonia patients with depressive disorder. PLoS One. 2014;9:e116436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradford DW, Goulet J, Hunt M, Cunningham NC, Hoff R. A cohort study of mortality in individuals with and without schizophrenia after diagnosis of lung Cancer. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:e1626–e1630. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerhard T, Huybrechts K, Olfson M, Schneeweiss S, Bobo WV, Doraiswamy PM, Devanand DP, Lucas JA, Huang C, Malka ES, Levin R, Crystal S. Comparative mortality risks of antipsychotic medications in community-dwelling older adults. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:44–51. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.122499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson JC, Spyker DA. Morbidity and Mortality Associated with Medications Used in the Treatment of Depression: An Analysis of Cases Reported to U.S. Poison Control Centers, 2000–2014. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:438–450. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crump C, Sundquist K, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Mental disorders and risk of accidental death. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203(3):297–302. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.123992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemogne C, Niedhammer I, Khlat M, Ravaud JF, Guillemin F, Consoli SM, Fossati P, Chau N. Lorhandicap group. Gender differences in the association between depressive mood and mortality: a 12-year follow-up population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kilbourne AM, Morden NE, Austin L, Ilgen M, McCarthy JF, Dalack G, Blow FC. Excess heart-disease-related mortality in a national study of patients with mental disorders: identifying modifiable risk factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenbaum PR, Rubina DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55. doi: 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ICD-9-CM guidelines . ICD-9-CM. US Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldman-Mellor S, Jia Y, Kwan K, Rutledge J. Syndromic surveillance of mental and substance use disorders: a validation study using emergency department chief complaints. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(1):55–60. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vin-Raviv N, Akinyemiju TF, Galea S, Bovbjerg DH. Depression and anxiety disorders among hospitalized women with breast cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang WC, Lu ML, Chen VC, Ng MH, Huang KY, Hsieh MH, Hsieh MJ, McIntyre RS, Lee Y, Lee CT. Asthma, corticosteroid use and schizophrenia: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Probst C, Roerecke M, Behrendt S, Rehm J. Socioeconomic differences in alcohol-attributable mortality compared with all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:1314–1327. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee SU, Oh IH, Jeon HJ, Roh S. Suicide rates across income levels: retrospective cohort data on 1 million participants collected between 2003 and 2013 in South Korea. J Epidemiol. 2017;27:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.je.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharp AL, Choi H, Hayward RA. Don't get sick on the weekend: an evaluation of the weekend effect on mortality for patients visiting US EDs. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:835–837. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:511–520. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-6-200209170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kisely S, Crowe E, Lawrence D. Cancer-related mortality in people with mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:209–217. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Searle SR, Speed FM, Milliken GA. Population marginal means in the linear model: an alternative to least squares means. Am Stat. 1980;34:216–221. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Good PD, Cavenagh J, Ravenscroft PJ. Survival after enrollment in an Australian palliative care program. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2004;27:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin PH, Liao SC, Chen IM, Kuo PH, Shan JC, Lee MB, Chen WJ. Impact of universal health coverage on suicide risk in newly diagnosed cancer patients: population-based cohort study from 1985 to 2007 in Taiwan. Psychoooncology. 2017;26:1852–1859. doi: 10.1002/pon.4396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holmstrand C, Bogren M, Mattisson C, Brådvik L. Long-term suicide risk in no, one or more mental disorders: the Lundby study 1947–1997. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132:459–469. doi: 10.1111/acps.12506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alavi SS, Mohammadi MR, Souri H, Mohammadi Kalhori S, Jannatifard F, Sepahbodi G. Personality, driving behavior and mental disorders factors as predictors of road traffic accidents based on logistic regression. Iran J Med Sci. 2017;42:24–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guan NC, Termorshuizen F, Laan W, Smeets HM, Zainal NZ, Kahn RS, De Wit NJ, Boks MP. Cancer mortality in patients with psychiatric diagnoses: a higher hazard of cancer death does not lead to a higher cumulative risk of dying from cancer. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:1289–1295. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0612-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rieke K, Schmid KK, Lydiatt W, Houfek J, Boilesen E, Watanabe-Galloway S. Depression and survival in head and neck cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 2017;65:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coryell WH, Butcher BD, Burns TL, Dindo LN, Schlechte JA, Calarge CA. Fat distribution and major depressive disorder in late adolescence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:84–89. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sahlberg M, Holm E, Gislason GH, Køber L, Torp-Pedersen C, Andersson C. Association of selected antipsychotic agents with major adverse cardiovascular events and noncardiovascular mortality in elderly persons. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001666. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat. 2015;72:334–341. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Remington G. Suicide in schizophrenia: an observational study of coroner records in Toronto. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:e98–103. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Afzali S, Saleh A, Rabiei MAS, Taheri K. Frequency of alcohol and substance abuse observed in drivers killed in traffic accidents in Hamadan, Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16:240–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hels T, Lyckegaard A, Simonsen KW, Steentoft A, Bernhoft IM. Risk of severe driver injury by driving with psychoactive substances. Accid Anal Prev. 2013;59:346–356. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Westman J, Wahlbeck K, Laursen TM, Gissler M, Nordentoft M, Hällgren J, Arffman M, Ösby U. Mortality and life expectancy of people with alcohol use disorder in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131:297–306. doi: 10.1111/acps.12330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Almeida OP, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, Norman PE, Flicker L. Mortality among people with severe mental disorders who reach old age: a longitudinal study of a community-representative sample of 37,892 men. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu J, Wang J, Wimo A, Qiu C. The economic burden of mental disorders in China, 2005–2013: implications for health policy. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:137. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0839-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Daley DC. Family and social aspects of substance use disorders and treatment. J Food Drug Anal. 2013;21:S73–S76. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2013.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kessing LV, Vradi E, McIntyre RS, Andersen PK. Causes of decreased life expectancy over the life span in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2015;180:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9:208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.