Abstract

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) breastfeeding peer counselling (BFPC) program supports optimal early life nutrition by providing evidenced‐based breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support. The Lactation Advice Through Texting Can Help (LATCH) study was a randomized controlled trial that tested the effectiveness of a text messaging intervention designed to augment the BFPC program. The purpose of the present study was to understand the topics discussed during the text message exchanges between breastfeeding peer counsellors (PCs) and their clients in the intervention arm of the LATCH study, from the time of enrollment up to two‐weeks postpartum. Text messaging data were first coded and analysed for one‐ and two‐way text message exchanges. Text messages of participants with a high volume of two‐way exchanges were then analysed qualitatively. Four domains were identified in both the prenatal and postpartum periods: the mechanics of breastfeeding, social support, baby's nutrition, and PCs maintaining contact with participants. Additional themes and subthemes identified in the postpartum period included the discussion of breastfeeding problems such as latching trouble engorgement, plugged ducts, pumping, other breastfeeding complications, and resuming breastfeeding if stopped. Two‐way text messaging in the context of the WIC BFPC program provides an immediate and effective method of substantive communication between mothers and their PC.

Keywords: breastfeeding, breastfeeding knowledge, breastfeeding promotion, breastfeeding support, peer support, postpartum

Abbreviations

- DOB

date of birth

- EDD

expected due date

Key messages

Integration of the LATCH program into the WIC breastfeeding peer counselling standard of care effectively augments the breastfeeding peer counselling Loving Support program by providing additional and repeated opportunities for breastfeeding education and support in the prenatal and postpartum periods.

The first 2 weeks postpartum is a critical period for the establishment and maintenance of lactation. The present study demonstrates that effective communication occurred via text message during this period between WIC mothers and their breastfeeding peer counsellors regarding common and important breastfeeding problems such as latching trouble, engorgement, plugged ducts, pumping, and resuming breastfeeding if stopped.

LATCH has strong potential for scale‐up within the WIC breastfeeding peer counselling program as a means to augment and reinforce the existing peer counselling model. An implementation science approach is needed for state‐wide adoption, implementation, scale‐up and maintenance of LATCH as an adjunct tool in the breastfeeding peer counselling program.

The LATCH intervention targeted WIC mothers with the prenatal intention to breastfeed. In order to broaden the reach of the intervention, adaptations are needed to reach mothers prenatally without a strong intention to breastfeed.

1. BACKGROUND

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) serves pregnant and postpartum low‐income women who are at risk of poor nutrition, reaching 48.0% of all infants born in the United States and 28.0% of all postpartum women as of 2016 (Oliveira, Prell, & Cheng, 2019). The Loving Support Makes Breastfeeding Work (Loving Support) program is an essential evidence‐based, peer counsellor (PC)‐led program designed to protect, promote, and support breastfeeding among WIC mothers. Breastfeeding PCs encourage breastfeeding as the foundation of early life nutrition by providing basic breastfeeding information and support in a socially and culturally appropriate manner. Peer counsellors are trained to provide culturally sensitive breastfeeding support under the supervision of an International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC). breastfeeding peer counselling is an effective means of providing repeated opportunities for education and support, both prenatally and in the postpartum period, to improve rates of initiation, duration and intensity (Chapman, Morel, Anderson, Damio, & Pérez‐Escamilla, 2010; Chapman & Pérez‐Escamilla, 2012). While rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration have improved among WIC mothers since the inception of the Loving Support program in 2004, strong barriers to breastfeeding remain, especially among the most vulnerable (Pérez‐Escamilla & Sellen, 2015).

An important body of qualitative research has documented the barriers to breastfeeding in this population, particularly in the first 2 weeks postpartum. These include lack of time to breastfeed, embarrassment to breastfeed in public, and social constraints at school or at work (Pérez‐Escamilla, 2012). Perceived low milk supply is one of the primary reasons for breastfeeding cessation and is expressed as a mother's belief her infant is not getting enough milk, that the infant is always hungry, and as mother's concerns about the infant's weight (Perez‐Escamilla, Buccini, Segura‐Perez, & Piwoz, 2019; Rozga, Kerver, & Olson, 2015). Poverty is also a factor; for example, a study found that while WIC mothers understood the benefits of breastfeeding, their financial needs required them to return to work within a few weeks of delivering their baby, in work environments that did not accommodate breast pumping breaks (i.e., waitressing or jobs requiring travel; Rojjanasrirat & Sousa, 2010). African‐American women attending the WIC program identified a need for improved social support for new mothers and their social networks in order to create a comprehensive breastfeeding friendly environment (Kim, Fiese, & Donovan, 2017). These qualitative studies demonstrate that innovative interventions are needed to augment the timeliness and reach of the WIC breastfeeding peer counselling program and that the interventions should address these important social, emotional, and breastfeeding skills barriers in this population in a timely fashion.

The Lactation Advice Through Texting Can Help (LATCH) intervention is an innovative approach to augment the effectiveness of PCs (Harari et al., 2017; Martinez‐Brockman et al., 2018). The LATCH study was a single‐blind, randomized controlled trial that tested the effectiveness of a two‐way text messaging intervention on exclusive breastfeeding in a sample of women attending one of four different WIC clinics in Connecticut and participating in the BFPC program. Control group participants received the BFPC standard of care Loving Support program. Intervention group participants received the standard of care + the text messaging intervention. The standard of care allows for the reinforcement of breastfeeding messages, both in‐person and by phone. The text messaging intervention allows for further repetition of key messages, which is important to the success of health education programs (National Academies, 2002). Results showed that while rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 2 weeks postpartum did not significantly differ between intervention and control group participants, mothers in the intervention group had a slightly higher rate of exclusive breastfeeding and significantly earlier contact with their PC after the baby was born than mothers in the control group (Martinez‐Brockman, Harari, Segura‐Perez, et al., 2018). Those mothers with a higher intensity of engagement via text were more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding at 2 weeks postpartum than those with a lesser intensity of engagement (Martinez‐Brockman, Harari, & Perez‐Escamilla, 2018). Intensity of engagement was defined as the number of breastfeeding issues addressed via two‐way exchanges. Early breastfeeding support is instrumental for longer term breastfeeding success. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to understand the topics discussed during the exchange of text messages between PCs and their clients in the intervention arm of the LATCH study, from the time of enrollment to 2 weeks postpartum. The specific objective was to identify the key domains, themes, and subthemes of discussion during the prenatal and postnatal periods.

2. METHODS

2.1. LATCH study design

The LATCH study (parent study) and the present study were approved by the Yale University Human Subjects Investigation Committee. LATCH was conducted from August 2014 to January 2016 and was registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov (protocol #: 1206010472) prior to the start of recruitment.

The LATCH study methods are described in detail elsewhere (Martinez‐Brockman, Shebl, Harari, & Perez‐Escamilla, 2017). Briefly, pregnant women ≤28 weeks gestation were eligible to participate if they attended one of four WIC clinics in CT, were enrolled in the BFPC program through that WIC clinic, and intended to breastfeed. Given the importance of prenatal intention to breastfeed on breastfeeding intensity and duration (Amir & Donath, 2007; Donath, Amir, & ALSPAC Study Team, 2003), potential participants were asked if they planned to breastfeed their child and if they answered affirmatively, were provided with a full description of the intervention. Breastfeeding PCs recruited participants, obtained informed consent, and enrolled mothers into LATCH. Participants completed a baseline telephone interview with a bilingual, bicultural research assistant within 2 weeks of enrollment and upon completion, were randomized to the intervention or the control group. In the intervention group only, text messages were exchanged and recorded via a HIPPA‐compliant web‐based text messaging platform (described below). By study design, PCs did not exchange text messages with control group participants.

2.1.1. Text messaging platform

The Mobile Commons (MC) two‐way text messaging platform was used to send text messages to intervention group participants. Table 1 explains the differences between the BFPC standard of care and LATCH with respect to the timing of contacts with mothers. The platform recorded the date and time the messages were sent, whether they were delivered successfully, and all message exchanges between participants and their PC.

Table 1.

Comparison of contacts with WIC mothers between control and intervention

| WIC BFPC programa (control) | LATCH study (intervention) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time frame | Frequency of contact | Time frame | Frequency of contact |

| Prenatal period | |||

| Enrollment to baby's DOB | At least once during pregnancy | Enrollment to 20 days before EDD | 1 text/2 days |

| — | — | 20 days before EDD | 1 text/day |

| Postpartum period | |||

| DOB to 7–10 days postpartum | Every 2–3 days (and within 24 hr if breastfeeding issue arises) | Days 1–4 | 5 texts/day |

| Days 5 and 6 | 4 texts/day | ||

| Days 7–14 | 3 texts/day | ||

| Month 1b | Weekly after BF going smoothly | Days 14–30 | 2 texts/day |

| Month 2b | 1/month | Days 30–60 | 2 texts/day |

| Month 3b | 1/month | Days 60–90 | 1 text/day |

| Year 1 | 1/month | — | — |

Abbreviations: BFPC, breastfeeding peer counselling; DOB, date of birth; EDD, expected due date; LATCH, Lactation Advice Through Texting Can Help; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children.

United States Department of Agriculture (2016).

The LATCH study continued to 3 months postpartum (Martinez‐Brockman, Harari, Segura‐Perez, et al., 2018), thus we display text message frequency for the full intervention; however, the current analyses are limited to the first 2 weeks (14 days) postpartum.

2.1.2. Text messaging

One‐way text message exchanges were defined as those that occurred between participants and the automated text messaging schedule and typically involved a brief response by the participant to an automated message (Martinez‐Brockman, Harari, & Perez‐Escamilla, 2018). Two‐way text message exchanges were defined as those that were initiated by the automated schedule (i.e., via preprogrammed and automated questions or automated check‐ins), the participant, or the PC and included an exchange between the participant and the PC (Martinez‐Brockman, Harari, & Perez‐Escamilla, 2018). The text messaging schedule was designed to augment and reinforce the Loving Support program BFPC standard of care.

2.2. Qualitative analysis

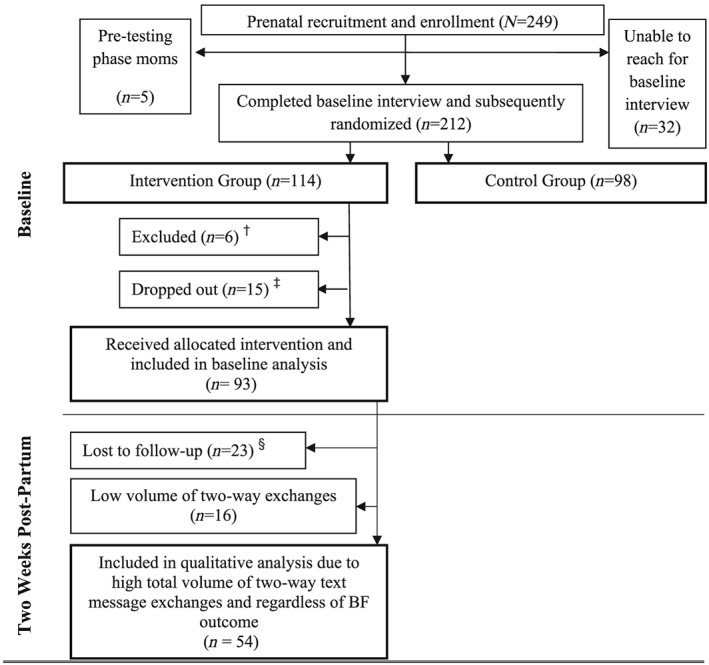

Figure 1 depicts the sample selection for this analysis. Per study design, the analysis presented only pertains to intervention group participants. The sample selected for the qualitative analysis (n = 54) was determined based on the total volume of two‐way text message exchanges between participants and their PC during the prenatal period. High volume was defined as >4 two‐way exchanges (above the median split), and low volume was ≤4 two‐way exchanges (below the median split). The total volume of exchanges in the prenatal period was used because participants were identified prenatally‐prior to establishing breastfeeding status at 2 weeks postpartum‐with the intention of following their text message conversations over time through the first 2 weeks postpartum. The text messaging data of the 54 participants with a high volume of two‐way exchanges were analysed to determine domains, themes, and subthemes during the prenatal and postpartum periods. The purpose of this analysis was to understand the topics discussed during the exchange of text messages between PCs and their clients.

Figure 1.

Sample selection for qualitative analysis. †Reasons for exclusion: premature birth (n = 1), withdrew from breastfeeding peer counselling (n = 1), miscarriage (n = 1), not singleton (n = 1), <5 lb at birth (n = 1), randomized to control but received intervention (n = 1). ‡Reasons for dropping out: opted out of study (n = 9), unable to obtain baby's date of birth (n = 6). §Participants were considered lost to follow‐up after eight unanswered call attempts and two unanswered text messages

First, text messaging data were coded and analysed for one‐ and two‐way exchanges. All text messages sent to and received from each participant were retrieved from the Mobile Commons platform to individual Excel files. Text messages were independently coded by two researchers as either one‐way or two‐way text message exchanges. Researchers met regularly to compare codes and discuss and resolve discrepancies.

Next, the two‐way text messages of participants with a high volume of two‐way exchanges were analysed qualitatively. The qualitative analysis sought to characterize the topics discussed prenatally and during the first 2 weeks postpartum through the systematic identification of domains, themes, and subthemes based on a rigorous consensus process. The analysis focused on the 54 participants with a high‐volume of engagement because the low‐volume participants did not have enough substantive two‐way exchanges to analyse. Substantive exchanges were broadly defined as those that did not involve the PC reestablishing contact with a participant (Martinez‐Brockman, Harari, & Perez‐Escamilla, 2018). This was because PCs were required to reestablish contact with a mom if that mom had been out of touch via text message for 2 weeks or longer. Two researchers independently analysed the two‐way text message exchanges to identify domains, themes, and subthemes using inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and the constant comparative method for qualitative analyses (Boeiji, 2002; Curry, Nembhard, & Bradley, 2009; Strauss & Corbin, 1990), both within and between PC‐mother dyads. Researchers met regularly to discuss the coding for each participant and to resolve discrepancies in coding. Saturation occurred when no new domains, themes or subthemes emerged—approximately mid‐way through the coding exercise. All analyses were conducted using Atlas.ti 7 (Berlin, Germany). Direct quotations from the text messages exchanges are presented below and are contextualized using mother's parity, previous breastfeeding experience, and the onset of copious milk production, variables associated with the likelihood of breastfeeding success (Chapman & Pérez‐Escamilla, 1999a, 1999b; Haughton, Gregorio, & Pérez‐Escamilla, 2010; Mirkovic, Perrine, Scanlon, & Grummer‐Strawn, 2014).

2.3. Quantitative analysis

Data were collected on maternal biomedical characteristics, breastfeeding planning and experience, infant feeding intentions, demographics, cell phone plan and type, household income, and household food insecurity. Univariate analyses were conducted using SAS Software Version 9.4.

2.4. Study strengths and limitations

We employed a qualitative approach to coding the two‐way text messages and conducted an in‐depth qualitative analysis of the text messaging conversations themselves. To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative analysis of two‐way text messaging conversations in an mHealth intervention. There are several study limitations to note. By study design, control group participants did not interact with their PC over text message, limiting the analysis to intervention group participants only. Although PCs were asked not to engage via text message with control group participants, we had one PC who used text messaging to schedule and coordinate home visits with control group participants as this was her standard of care prior to LATCH. We were unable to determine whether text message conversations were occurring outside of the LATCH platform in the control group, and if so, whether the content of those text message conversations were substantively different from the conversations happening between the intervention group participants and their PCs within the LATCH platform. A second limitation is that the text messages of participants in the intervention arm with a low volume of two‐way exchanges (below the median) were not analysed. This was because there were very few text message exchanges to analyse. The large majority of exchanges that did exist in the low‐volume group were exchanges initiated by the PC to reestablish contact with the participant. This may mean that the low‐volume participants were more passive consumers of the text message content as opposed to active and engaged consumers like the high‐volume participants, and that passive consumption does not lead to improved breastfeeding outcomes. Third, in several instances the domain, theme, or subtheme may have been influenced by the specific content of the automatic messages. Automated messages were scheduled to be delivered at predetermined time points based on the baby's expected due date (Martinez‐Brockman et al., 2017). Themes derived from exchanges triggered by an automated message may not have occurred without the automatic message or may have been different if the content of automated message had been different. Finally, the LATCH study recruited mothers who intended to breastfeed their infants. The results of the present study are only applicable to mothers with the intention to breastfeed. Adaptations may need to be made to the intervention for the prenatal period if it were to target women without a clear intention to breastfeed. For example, the intervention would need to more intensely address key variables that affect the formation of the intention to breastfeed. These include a mother's outcome expectancies (the pros and cons of breastfeeding behavior), risk perception (how risky she views breastfeeding to be both for herself and her child), and action self efficacy (confidence in her ability to initiate breastfeeding; Martinez‐Brockman et al., 2017).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Description of the sample

At baseline, participants ranged in age from 18 to 41 and were on average 27.3 ± 5.4 years old (Table 2). About 66% were Hispanic, 77.4% single, never married, and 42.6% were high school graduates or had obtained their General Education Diploma (GED). The average prepregnancy weight was 165.7 ± 47.6 pounds, with the average BMI in the overweight category (29.9 ± 7.1). Participants were 23.1 ± 2.8 weeks gestation on average at recruitment. While 61.1% of mothers had other children at home, more than half (52.8%), had no previous breastfeeding experience.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics of women included in the qualitative analysis (n = 54)a

| Maternal biomedical characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27.3 ± 5.4 |

| Prepregnancy weight (lb) | 165.7 ± 47.6 |

| Prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 29.9 ± 7.1 |

| Gestational age at recruitment (week) | 23.1 ± 2.8 |

| Primiparous | |

| Yes | 21 (38.9) |

| No | 33 (61.1) |

| Breastfeeding planning and experience | |

| Planned any BF duration (month) | 8.8 ± 5.0 |

| Planned EBF | |

| Yes | 39 (72.2) |

| No | 15 (27.8) |

| Planned EBF duration (month) | 5.6 ± 5.0 |

| Planned partial BF | |

| Yes | 33 (61.1) |

| No | 21 (38.9) |

| Planned partial duration (month) | 3.0 ± 4.0 |

| Previous BF experience | |

| Yes | 25 (47.2) |

| No | 28 (52.8) |

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 35 (66.0) |

| Non‐Hispanic | 18 (34.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Single, never married | 41 (77.4) |

| Married | 9 (17.0) |

| Divorced/sep./widowed | 3 (5.7) |

| Living with partner | |

| Yes | 37 (69.8) |

| No | 16 (30.2) |

| Maternal education | |

| High school grad/GED | 20 (42.6) |

| <HS | 7 (14.9) |

| >HS | 20 (42.6) |

| Language preference | |

| English | 37 (69.8) |

| Spanish | 16 (30.2) |

Abbreviations: BF, breastfeeding; BMI, body mass index; GED, General Education Diploma .

Table values are mean ± SD for continuous variables and n (column %) for categorical.

Of the 54 participants whose two‐way text messaging data were analysed for this study, 23 were exclusively breastfeeding at 2 weeks postpartum (42.6%), 22 were partially breastfeeding (40.7%), one was no longer breastfeeding (1.9%), and eight were unable to be reached and thus did not have a breastfeeding status (14.8%). While the qualitative analysis was conducted independent of breastfeeding status, this information helps to contextualize the qualitative findings presented below.

3.2. Prenatal domains, themes and subthemes

During the prenatal period, four main domains of discussion were identified: (a) the mechanics of breastfeeding; (b) social support; (c) baby's nutrition; and (d) PCs maintaining contact with participants. Each of these domains and their themes and subthemes (where applicable) are presented in Table 3 and described in detail.

Table 3.

Qualitative domains, themes, and subthemes by time perioda

| Prenatal | First two weeks postpartum |

|---|---|

| 1. Mechanics of breastfeeding | |

| a. Timing | a. Timing |

| Length of feedings | Length of feedings |

| BF initiation and skin‐to skin | Frequency of feedings |

| Frequency of feedings | b. Milk supply |

| Start of milk production | Signs baby is hungry/full |

| b. Milk supply | What to do if baby still hungry |

| Milk production (colostrum) | How to maintain/increase supply |

| Signs baby is hungry/full | c. Proper positioning |

| c. Proper positioning | Feeding positions and pain |

| Feeding positions and pain | Where to feed baby—locations |

| Latching concerns | d. Breastfeeding problems |

| d. Other breastfeeding questions | Latching trouble |

| BF while on medication | Pumping |

| How to obtain breast pump | Engorgement |

| BF after caesarean section | Plugged ducts |

| Other breast complications | |

| Resuming BF if stopped | |

| 2. Social support | |

| a. Social support from PC | a. Social support from PC |

| b. Asking other professionals for help | b. Asking other professionals for help |

| c. PC calling participants | c. Family support |

| d. Pressure to give formula | |

| 3. Baby's nutrition | |

| a. Nutritional benefits of BF | a. Addition of formula |

| b. Addition of formula | b. Diverse diet and drink water |

| c. Introduction of solids | c. Check if baby getting enough breast milk |

| 4. PC maintaining contact with participants | |

| a. Scheduling appointments | a. Scheduling appointments |

| b. Check‐ins for baby's arrival | b. Check‐ins related to mom's well‐being and BF progress |

| c. Maintaining or reestablishing contact | c. Maintaining or reestablishing contact |

| d. Helpfulness of texts | d. Helpfulness of texts |

Abbreviations: BF, breastfeeding, PC, peer counsellor.

Domains are numbered, themes are lettered, and subthemes appear beneath themes. Postpartum themes and subthemes in italics differ from prenatal themes and subthemes.

3.2.1. Mechanics of breastfeeding

The mechanics of breastfeeding was one of the principal topics of discussion during the prenatal period. Participants asked their PCs about the when, where, and how of breastfeeding, generating four themes: (a) timing; (b) milk supply; (c) proper positioning; and (d) other breastfeeding questions. With respect to timing or time‐related aspects of breastfeeding, four subthemes emerged. Participants wanted to know how long each feed was going to take, when to start feeding the baby (breastfeeding initiation and skin to skin contact), how often to feed the baby (frequency of feedings), and when milk production would begin. In many instances, the participant's questions came in response to an automated message (Note: in the exchanges presented below, “automated message” refers to the preprogrammed text messaging schedule. These messages may be interspersed in conversations between PCs and participants.):

| Message | Date/time |

|---|---|

| Automated message: Great! If you have any more questions let me know! | 9/16/14 20:48 |

| Mom: Yes. | 9/16/14 20:48 |

| Mom: I know with formula I have to feed the baby every 2–3 hours. How often with breast milk? | 9/16/14 20:50 |

| Mom: Or does it depend on the baby? | 9/16/14 20:51 |

| PC: With breast milk is 8 to 10 times a day, usually every one to two hours. Breast milk is easier to digest that's why you need to breastfeed more often. | 9/17/14 20:26 |

| PC: When they get older, like around 3 months, they usually feed every 3 hours. | 9/17/14 20:28 |

| Mom: Oh my goodness. I'm in for a rude awakening. | 9/17/14 21:10 |

| PC: Good morning! Hope you had a good night. I know it might sound overwhelming about the average time breastfeeding babies eat. Try not to focus on the number. | 9/18/14 15:30 |

| PC: It is very important to watch for signs the baby is hungry. All babies are different and fall into their own feeding patterns. I hope this is comforting to you. | 9/18/14 15:31 |

| Mom: Yes it is thanks. | 9/18/14 15:40 |

| —Multiparous participant with no previous breastfeeding experience, whose milk came in one day postpartum, and who was partially breastfeeding at two weeks. | |

Participants also had conversations with their PC about milk supply. The primary concern was being able to make enough milk for the baby. Two subthemes emerged, milk production (including colostrum) and signs baby is hungry/full. General milk production and supply conversations addressed concerns that mothers had about not making enough milk for their babies. Some participants who were not leaking colostrum wanted to know if they would make enough milk, and those who were leaking colostrum wondered if the colour and composition would change once the baby was born and if it would be enough. PCs reassured moms that they would make enough milk for their baby and reinforced the concept of demand and supply‐the more milk that is removed, the more milk mom will make. One participant wondered whether her milk would come in the same way, if she delivered early, as it would if she delivered before or around her due date. Her PC reassured her that even if her baby is born prematurely, “your milk will be there and ready with all the important nutrients that your baby is going to need.”

Participants also wanted to know how to determine whether the baby is hungry or has had enough milk. PCs explained the early signs that baby is hungry, such as sucking on their fists, and that crying is a late sign of hunger. They also explained that the baby is usually full when she releases the breast and stops feeding on her own:

| Message | Date/time |

|---|---|

| Automated message: Crying is a late sign of hunger. Look for early cues that your baby is hungry (smacking lips, sucking hands). For more signs see: [link] | 8/10/15 18:00 |

| Mom: How do I know if my baby is full? | 8/10/15 18:02 |

| PC: Excellent question [name]! Many babies will stop feeding on their own when they are full. They come off the breast on their own or they fall asleep. | 8/11/15 14:12 |

| PC: We also know they are eating enough by seeing how many dirty diapers they make in 24 hours. | 8/11/15 14:13 |

| Automated message: Good morning [name]. It's [PC]. Just checking on you. Did you have baby yet? | 8/11/15 14:16 |

| Mom: No not yet. 2 more weeks. | 8/11/15 14:38 |

| Automated message: Ok. Is my number in your phone? Text BABY HERE when baby is born. The first few days are very important. We'll work together to get breastfeeding going well. [PC]. | 8/11/15 14:38 |

| Mom: Yes. And thank you I will. | 8/11/15 14:43 |

| PC: Did we help answer your question about how you know your baby is satisfied? | 8/11/15 15:09 |

| Mom: Yes. | 8/11/15 15:10 |

| PC: Excellent, let us know if we can help in any way. Stay dry and safe today. | 8/11/15 16:04 |

| —Multiparous participant with previous breastfeeding experience that was not positive, whose milk came in three days postpartum and who was exclusively breastfeeding at two weeks. | |

The third theme within the mechanics domain was proper positioning. Two subthemes emerged‐feeding positions and pain and latching concerns. Participants asked their PC about how to position their baby during feedings and how to know if the baby is latching on well. Some participants wanted to know whether pain while breastfeeding was normal and should be expected. Their PC reassured them that “it is not supposed to hurt if the baby opens its mouth well and latches well, there is no reason it should hurt.”

Finally, the other breastfeeding questions theme addressed concerns related to the mechanics of breastfeeding that were not specifically about timing, positioning, or supply. Subthemes included breastfeeding while on medication, how to obtain a breast pump, and breastfeeding after a c‐section. Participants asked their PCs about breastfeeding while on methadone, while on medication for irritable bowel syndrome, and while on medication after a c‐section. They also wanted to know how to obtain a breast pump and when to start using it. PCs also addressed participants' concerns that they would not be able to breastfeed right away if they had a c‐section. The following exchange exemplifies how PCs used the text messages as a means to educate participants about the benefits of breastfeeding, even in difficult or complex circumstances:

| Message | Date/time |

|---|---|

| Mom: Could mothers breastfeed while they are on methadone? | 15 14:39 |

| PC: Yes it is greatly recommended. The babies whose mothers are currently on methadone have withdraw symptoms and when moms chose to breastfeed babies feel … | 3/31/15 14:39 |

| Mom: And are you sure that is ok to breastfeed while smoking cigarettes or have nicotine in my system | 3/31/15 14:50 |

| PC: … better with mothers [sic] milk will help them with the withdraw symptoms after being born and as they continue to breastfeed | 3/31/15 14:51 |

| Mom: Is it ok to breastfeed while having nicotine in your system | 3/31/15 14:52 |

| PC: The biggest concern in terms of breastfeeding and smoking it is milk supply. Smoking can lower your milk supply. | 3/31/15 14:53 |

| PC: When breastfeeding and smoking the risks of not breastfeeding places your baby at far higher risks for a lot of different diseases. | 3/31/15 14:54 |

| PC: When you breastfeed you are protecting your baby more than if you were not. | 3/31/15 14:55 |

| PC: If you have anymore [sic] concerns I could print out some more information about breastfeeding and smoking. Unfortunately now I have a client that just arrived. | 3/31/15 14:56 |

| PC: Or I can call you later if you wish. Let me know if anything. – [name]. | 3/31/15 14:56 |

| —Multiparous participant with no previous breastfeeding experience, whose milk came in the same day baby was born, and who was exclusively breastfeeding at two weeks postpartum. | |

Social support

The social support domain exemplifies the manner in which participants sought support from their PCs and how the PCs worked with their clients to improve their self‐efficacy. Three main themes emerged, including obtaining social support from the PC, asking other professionals for help, and PCs calling participants to provide further in‐depth support. PCs used the text messages to reassure participants that they would be there to provide breastfeeding support as soon as the baby was born. They also encouraged moms to ask the hospital staff for breastfeeding help, explaining that nurses are trained to help moms learn how to breastfeed and resolve breastfeeding issues. PCs also used the text messages to let moms know they were going to call them to follow‐up on a certain topic.

Baby's nutrition

The third domain addressed participant's questions and concerns about their baby's nutrition. Three themes emerged including the nutritional benefits of breastfeeding, the addition of formula, and the introduction of solids. Participants asked questions about how breastfeeding would benefit their baby, when and how to introduce formula, when to introduce solids, and what kinds of solids to start with.

| Message | Date/time |

|---|---|

| Mom: Hi can one mix breast milk with cereal for the baby? | 7/16/15 17:39 |

| Automated message: Usually breastfeeding lasts 15–20 minutes or longer. But, there is no set time. Remember, watch your baby (not the clock) to know when s/he is full. | 7/16/15 18:00 |

| PC: Most babies can start solids around 6 mos. Any sooner can be risky. Best first foods are all natural and iron rich … | 7/16/15 18:39 |

| PC: … which means processed cereal with artificial iron is a poor choice. You can always mix your milk with baby's table foods. Good way to prevent constipation. | 7/16/15 17:40 |

| PC: Does that answer your question? ☺ | 7/16/15 17:40 |

| Mom: Yes, thank you | 7/16/15 17:41 |

| —Primiparous participant whose milk came in the same day baby was born and who was exclusively breastfeeding at two weeks postpartum. | |

PC maintaining contact with participants

The final domain identified during the prenatal period addressed themes that involved the PC attempting to maintain communication with participants. Themes included scheduling appointments, check‐ins for baby's arrival, maintaining and/or reestablishing contact, and helpfulness of texts. For example, PCs used text messaging to schedule in‐person appointments (office and home visits). They also checked‐in periodically with participants to determine if the baby had been born before its due date and to make sure moms were receiving all of the text messages. For those that had been out of touch for 2 weeks or more, the PCs used the text messages as a way to send a personal note and reestablish contact with participants. Finally, PCs periodically asked participants if they found the text messages helpful. The following exchange exemplifies the scheduling subtheme and incorporates a discussion about colostrum:

| Message | Date/time |

|---|---|

| Mom: Do you begin to produce milk as soon as the baby is born? The liquid I have now is not milk, it's clear. | 5/16/15 22:33 |

| Automated message: Breastfed babies control what they eat by themselves; they take what they need at each feeding. | 5/18/15 18:00 |

| PC: Hi [name] it's [IBCLC], I work with [PC]. Great question! You may have some leaking now that shows you are preparing to breastfeed. | 5/18/15 19:54 |

| Mom: Okay thank you. I also wanted to let you know that on the 22 nd this upcoming Friday I get out of work at 1 pm and am available to meet you or [PC] at that time. | 5/18/15 19:56 |

| PC: When baby is born you produce a yellowish thick liquid called colostrum which is the exact amount your baby needs. About 4 days after it changes to white. | 5/18/15 19:56 |

| PC: [PC] will be back on Wednesday and can set up a time or I'll be there on Friday at 1:00 pm so I can see you then if you'd like. # XXX‐XXX‐XXXX, ext. XXX. | 5/18/15 20:00 |

| Mom: Okay sounds great! It would be nice to meet you both! | 5/18/15 20:01 |

| —Primiparous participant whose milk came in two days postpartum and who was exclusively breastfeeding at two weeks. | |

3.2.2. Postpartum domains, themes, and subthemes

During the first 2 weeks postpartum, the same four domains of discussion emerged; however, the themes differed somewhat from the prenatal period as anticipated. Each of the themes and subthemes are described in detail below.

Mechanics of breastfeeding

In the mechanics of breastfeeding domain, the first three themes remained the same in that participants continued to have questions about timing (breastfeeding duration and frequency of feedings), milk supply (signs baby is hungry/full, what to do if the baby is still hungry, and how to maintain or increase supply), and positioning (feeding positions and where to feed—finding a quiet and calm location). A fourth theme, breastfeeding problems, emerged in the postpartum period and contained several subthemes including: latching trouble, pumping, engorgement, plugged ducts, other breast complications, and resuming breastfeeding if stopped. Where possible, PCs responded to these issues via text and called to follow‐up with participants and/or schedule an in‐person visit where needed. Many participants sought advice for engorgement and plugged ducts:

| Message | Date/time |

|---|---|

| Automated message: Excellent! You are still breastfeeding today! Sometimes your breasts can feel hard and sensitive. Text me or call me if this is how you feel. | 1/15/15 13:00 |

| Mom: Yes | 1/15/15 13:07 |

| Mom: My breasts are very hard. | 1/15/15 13:08 |

| Mom: One question – I have somewhat large lumps (in my breasts) and pain in my armpits. | 1/15/15 13:09 |

| PC: Good morning [name]. Your breasts feel hard and with lumps because they are full. | 1/15/15 14:22 |

| PC: You need to breastfeed frequently, [use] luke warm compresses, and massage the lumps while you are breastfeeding. The lumps are ducts plugged with milk and they are resolved with massage. | 1/15/15 14:26 |

| PC: Another suggestion is to use a comfortable bra without an underwire. Also, different breastfeeding position may help. | 1/15/15 14:35 |

| PC: If this does not help, please let me know. | 1/15/15 14:26 |

| —Multiparous participant with no previous breastfeeding experience whose milk came in the same day baby was born. Breastfeeding status at two weeks was missing. | |

Social support

PCs continued to provide social support in the postpartum period, addressing specific problems or concerns. Four themes emerged, with the first two mirroring those during the prenatal period. They included: support from the PC, asking other professionals for help, family support, and pressure to give formula. PCs encouraged moms who were having difficulties, cheered on successes, and provided support and guidance via text message and in‐person where possible. They encouraged participants to seek family support and addressed pressures from family and others to provide formula. They also encouraged participants to ask nurses and other hospital staff for breastfeeding support immediately after giving birth.

Baby's nutrition

The themes identified in this third domain differed slightly from the prenatal period. PCs continued to address questions and concerns about the addition of formula as they did prenatally. Different from prenatal conversations, they also spoke with moms about the importance of a diverse diet for meeting the baby's nutrient needs and drinking plenty of water while breastfeeding to maintain milk supply. They also advised participants how to check if baby was getting enough breast milk by monitoring the colour and quality of baby's bowel movements and the number of wet diapers:

| Message | Date/time |

|---|---|

| Automated message: You are doing great! Please text me if you need any help. | 8/21/15 12:00 |

| Mom: Thank you! He is doing good. He latched yesterday for like 30 minutes and sleep for 3 hours straight. | 8/21/15 13:12 |

| PC: Great! Feed on demand and make sure he does not go to sleep over 3 hours wake him up. | 8/21/15 13:16 |

| PC: We want him to eat often so he gains back his birth weight and more. | 8/21/15 13:17 |

| Mom: And he's pooping every time he eats now, it's yellow | 8/21/15 13:18 |

| PC: Great, how many times in the last 24 hours? | 8/21/15 13:30 |

| Mom: 6 | 8/21/15 13:31 |

| PC: Poop is yellow and seedy? | 8/21/15 13:31 |

| Mom: Yes | 8/21/15 13:34 |

| PC: Great! How about pees? How many? | 8/21/15 13:45 |

| Mom: Every time I change a dirty diaper it's pee too, plus I changed 3 just pee. | 8/21/15 14:02 |

| PC: Great! The more he pee [sic] and poop it means he is eating enough | 8/21/15 14:04 |

| PC: Around this age we want to see 4 pees or more and 3 poops or more in 24 hours so that means he is doing excellent. | 8/21/15 14:05 |

| PC: Remember I am here if you have questions | 8/21/15 14:12 |

| Mom: Thank you so much for your help! | 8/21/15 14:20 |

| PC: You're welcome! | 8/21/15 14:47 |

| —Multiparous participant with previous breastfeeding experience that was not positive, whose milk came in three days postpartum and who was exclusively breastfeeding at two weeks. | |

PC maintaining contact with participants

As in the prenatal period, PCs used the text messaging platform to maintain contact after the baby was born. Themes included scheduling appointments, check‐ins related to mom's well‐being and breastfeeding progress, maintaining and/or reestablishing contact, and assessing the helpfulness of texts. In the example below, the participant responds to an automated text asking how breastfeeding is going. The IBCLC then reaches out via text to offer her support.

| Message | Date/time |

|---|---|

| Automated message: You'll be going home with your new baby soon. Is breastfeeding going well? (yes/no) | 8/7/15 12:00 |

| Mom: No | 8/7/15 12:41 |

| Automated message: What's going on exactly? We can work together on this [PC] | 8/7/15 12:41 |

| Mom: He only fed well 3 times since being born. I hand expressed and fed him with a syringe once also but he's just not sucking. He is latching well … | 8/7/15 12:43 |

| Mom: … but not sucking. Last night I had to use a nipple shield to get him to suck and he fed well with that. | 8/7/15 12:43 |

| Automated message: Before going home make sure your baby has a doctors [sic] visit for a weight check. Make sure this is about 2 days after going home. | 8/7/15 14:00 |

| PC: Hi [name]. [IBCLC] from WIC. Call if you would like BF support: XXX‐XXX‐XXXX till 4 pm today. | 8/7/15 15:07 |

| —Primiparous participant whose milk came in three days postpartum and who was exclusively breastfeeding at two weeks. | |

4. DISCUSSION

This qualitative analysis demonstrated that two‐way text messaging provides mothers with an easily accessible method of communicating with their PC on topics related to breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support‐both prenatally and in the first 2 weeks postpartum. Prenatally, moms expressed their questions and doubts about breastfeeding via two‐way text messaging with their PC. Based on our findings here and those of a separate analysis (Martinez‐Brockman et al., 2017), it is likely that the topics discussed allowed mothers to enhance their breastfeeding knowledge and self‐efficacy, as well as build and reinforce their social support network at home and by developing a relationship with their PC. In the postpartum period, moms drew upon their newfound support with their PC to resolve breastfeeding problems. The texting platform (in combination with the BFPC standard of care procedures like follow‐up phone calls and in‐person visits) can be used to help address most breastfeeding issues in a timely manner like engorgement, plugged ducts, latching concerns, and to resolve pain and discomfort so as not to affect the mother's milk supply or the baby's caloric intake. This study strongly suggests that two‐way text messaging is an innovative way for moms to discuss these critical breastfeeding issues with their PC as they emerge. It also demonstrates that well trained and supervised PCs can indeed engage in the delivery of care of breastfeeding women as part of a health care team.

5. CONCLUSION

The qualitative findings presented here add to previous LATCH study findings in several ways. First, they help to contextualize the quantitative findings regarding the time‐to‐first text message contact after delivery and exclusive breastfeeding behavior—the primary and secondary outcomes of the randomized controlled trial (Martinez‐Brockman et al., 2017; Martinez‐Brockman, Harari, & Perez‐Escamilla, 2018; Martinez‐Brockman, Harari, Segura‐Perez, et al., 2018), by demonstrating that substantive breastfeeding conversations were occurring via text message. Second, they demonstrate that planning for the standard of care, in‐person and telephone follow‐up, was also occurring via text. Third, they add to the mHealth and breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support literature by demonstrating that important breastfeeding issues can be discussed and addressed via two‐way SMS. Together with previous LATCH study findings, they provide a convincing case for the refining and scale‐up of the LATCH model via the WIC program. Key components that lent themselves to the success of the project and that will need to be in place for the scaling up of LATCH included the enthusiasm that the IBCLCs and PCs had for the adjunct tool, particularly the desire to find a more immediate method of communicating with WIC mothers, and the support of the WIC BFPC program administrators at the state level. The automated nature of the texts and the ability to monitor text message conversations via the online platform also facilitated PC work flow. Scale‐up of LATCH should be guided by an implementation science framework (Damschroder et al., 2009) and the implementation and scale‐up strategy should be tested using an implementation research design (Curran, Bauer, Mittman, Pyne, & Stetler, 2012) to ensure that the integration of the intervention into BFPC standard of care is feasible, useful to all key stakeholders, and sustainable.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors participated in the design of this study. Author J.M.B. wrote the first version of this manuscript and authors N.H., R.P.E., L.G., and V.B. critically reviewed and provided feedback on each subsequent version.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Diksha Ashwin Brahmbatt for her help in the qualitative coding and analysis. This project was funded with Federal funds from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service through grant WIC NEI‐12‐TX to Baylor College of Medicine to Dr. Rafael Pérez‐Escamilla at Yale University. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the view or policies of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Martinez‐Brockman JL, Harari N, Goeschel L, Bozzi V, Pérez‐Escamilla R. A qualitative analysis of text message conversations in a breastfeeding peer counselling intervention. Matern Child Nutr. 2020;16:e12904 10.1111/mcn.12904

REFERENCES

- Amir, L. H. , & Donath, S. M. (2007). A systematic review of maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation and duration. BMC Pregancy & Childbirth, 7, 9 10.1186/1471-2393-7-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeije, H. (2002). A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality and Quantity, 36, 391–409. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, D. J. , Morel, K. , Anderson, A. K. , Damio, G. , & Pérez‐Escamilla, R. (2010). Breastfeeding peer counseling: From efficacy through scale‐up. Journal of Human Lactation, 26, 314–326. 10.1177/0890334410369481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, D. J. , & Pérez‐Escamilla, R. (1999a). Does delayed perception of the onset of lacatation shorten breastfeeding duration? Journal of Human Lactation, 15, 107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, D. J. , & Pérez‐Escamilla, R. (1999b). Identification of risk factors for delayed onset of lactation. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 4, 450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, D. J. , & Pérez‐Escamilla, R. (2012). Breastfeeding among minority women: Moving from risk factors to interventions. Advances in Nutrition, 3, 95–104. 10.3945/an.111.001016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran, G. M. , Bauer, M. , Mittman, B. , Pyne, J. M. , & Stetler, C. (2012). Effectiveness‐implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical Care, 50, 217–226. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry, L. A. , Nembhard, I. M. , & Bradley, E. H. (2009). Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation, 119, 1442–1452. 10.1161/circulationaha.107.742775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder, L. J. , Aron, D. C. , Keith, R. E. , Kirsh, S. R. , Alexander, J. A. , & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4, 50 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath, S. M. , Amir, L. H. , & ALSPAC Study Team (2003). Relationship between prenatal infant feeding intention and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: A cohort study. Acta Paediatrica, 92, 352–356. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2003.tb00558.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harari, N. , Rosenthal, M. S. , Bozzi, V. , Goeschel, L. , Jayewickreme, T. , Onyebeke, C. , … Perez‐Escamilla, R. (2017). Feasibility and acceptability of a text message intervention used as an adjunct tool by WIC breastfeeding peer counsellors: The LATCH pilot. Maternal & Child Nutrition, e12488 10.1111/mcn.12488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughton, J. , Gregorio, D. , & Pérez‐Escamilla, R. (2010). Factors associated with breastfeeding duration among Connecticut Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) participants. Journal of Human Lactation, 26, 266–273. 10.1177/0890334410365067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. H. , Fiese, B. H. , & Donovan, S. M. (2017). Breastfeeding is natural but not the cultural norm: A mixed‐methods study of first‐time breastfeeding, African American mothers participating in WIC. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 49, S151–S161.e151. 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez‐Brockman, J. L. , Harari, N. , & Perez‐Escamilla, R. (2018). Lactation Advice Through Texting Can Help (LATCH): An analysis of intensity of engagement via two‐way text messaging. Journal of Health Communication, 23, 40–51. 10.1080/10810730.2017.1401686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez‐Brockman, J. L. , Harari, N. , Segura‐Perez, S. , Goeschel, L. , Bozzi, V. , & Perez‐Escamilla, R. (2018). Impact of the Lactation Advice Through Texting Can Help (LATCH) trial on time‐to‐first‐contact and exclusive breastfeeding among WIC participants. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 50, 33–42.e31. 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez‐Brockman, J. L. , Shebl, F. M. , Harari, N. , & Perez‐Escamilla, R. (2017). An assessment of the social cognitive predictors of exclusive breastfeeding behavior using the Health Action Process Approach. Social Science & Medicine, 182, 106–116. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirkovic, K. R. , Perrine, C. G. , Scanlon, K. S. , & Grummer‐Strawn, L. M. (2014). In the United States a mother's plans for infant feeding are associated with her plans for employment. Journal of Human Lactation, 30, 292–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies (2002). Committee on communication for behavior change in the 21st century: Improving the health of diverse populations and Behavioral Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, V. , Prell, M. , & Cheng, X. (2019). The economic impacts of breastfeeding: A focus on USDA's Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; Retrieved from https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/91273/err‐261.pdf?v=2226.3 [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. (2012). Breastfeeding social marketing: Lessons learned from USDA's “Loving Support” campaign. Breastfeeding Medicine, 7, 358–363. 10.1089/bfm.2012.0063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez‐Escamilla, R. , Buccini, G. S. , Segura‐Perez, S. , & Piwoz, E. (2019). Perspective: Should exclusive breastfeeding still be recommended for 6 mo? Advances in Nutrition, 00, 1–13. 10.1093/advances/nmz039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , & Sellen, D. (2015). Equity in breastfeeding: Where do we go from here? Journal of Human Lactation, 31, 12–14. 10.1177/0890334414561062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojjanasrirat, W. , & Sousa, V. D. (2010). Perceptions of breastfeeding and planned return to work or school among low‐income pregnant women in the USA. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19, 2014–2022. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03152.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozga, M. R. , Kerver, J. M. , & Olson, B. H. (2015). Self‐reported reasons for breastfeeding cessation among low‐income women enrolled in a peer counseling breastfeeding support program. Journal of Human Lactation, 31, 129–137. 10.1177/0890334414548070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A. C. , & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service (2016). Loving support through peer counseling: A journey together—For WIC managers (2016). Washington, DC, Author; Retrieved from https://wicworks.fns.usda.gov/wicworks/LovingSupport/PCManagement/SpeakerNotes.pdf [Google Scholar]