Abstract

Sleep plays an integral role in maintaining health and quality of life. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a prevalent sleep disorder recognized as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and arrhythmia. Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is a common and devastating event. Out-of-hospital SCD accounts for the majority of deaths from cardiac disease, which is the leading cause of death globally. A limited but emerging body of research has further elaborated on the link between OSA and SCD. In this article, we aim to provide a critical review of the existing evidence by addressing the following questions: (1) what epidemiologic evidence exists linking OSA to SCD; (2) what evidence exists for a pathophysiologic connection between OSA and SCD; (3) are there electrocardiographic markers of SCD found in patients with OSA; (4) does heart failure represent a major effect modifier regarding the relationship between OSA and SCD; and (5) what is the impact of sleep apnea treatment on SCD and cardiovascular outcomes. Finally, we elaborate on ongoing research to enhance our understanding of the OSA-SCD association.

Key Words: Obstructive sleep apnea, QTc, Sleep, Sudden cardiac death, Ventricular arrhythmia

Disorders of sleep such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), insomnia, abnormal sleep duration, and poor sleep quality have been associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity and mortality.1–5 OSA, despite being underdiagnosed, is by far the most common form of sleep apnea, affecting 9–38% of the global adult population.6 Its prevalence increases with body weight, age, and being male.6–8 Given the aging population and pandemic of obesity globally, the public burden of OSA is likely to increase further.9–11 OSA’s impact on CVD has been highlighted extensively, and the condition has been linked to increased risk of congestive heart failure (CHF), coronary artery disease (CAD), stroke, atrial fibrillation (AF), sinus pauses, increased burden of premature ventricular complexes (PVC), and first-degree heart block.3,5,12–14

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is defined as an unanticipated natural death from cardiac pathology ≤1 h from symptom onset in a person without any prior condition that would appear fatal.15 According to the American Heart Association, in the USA, approximately 366,807 cases of SCD occurred in 2015.16 Globally, CVD is the leading cause of mortality, with SCD being the most common manifestation.17 Fatal arrhythmia is widely recognized as the underlying process in the majority of cases of SCD, with ischemic heart disease present in 75% of cases.18 A number of studies have examined the role OSA plays in malignant arrhythmias by characterizing its association with high-risk electrocardiography (ECG) features.19–24 Despite the paucity of evidence, there is a growing body of work evaluating OSA as a risk factor for SCD. In the present study we lay out connections between SCD and OSA that have been highlighted in recent studies.

Methods

Based on the consensus of three reviewers, targeted areas of review were determined. Thereafter, all three reviewers independently searched Pubmed, Medline US, NIH Clinicaltrial.gov, and Google Scholar to find studies pertinent to the targeted questions. We restricted our search to manuscripts published in peer-reviewed journals from 1980 to 2018. The primary search phrases used were “obstructive sleep apnea”, “sudden cardiac death”, “ventricular arrhythmia”, “arrhythmia”, “atrial fibrillation”, “cardiac arrest”, “arrhythmogenic”, “continuous positive airway pressure”, “sleep disordered breathing”, “coronary artery disease”, “acute coronary syndrome” “pathophysiology”, “epidemiology”, “prolonged QTc”, “nocturnal sudden death”, and “heart failure”. Subsequently, other studies were identified based on the citations of the retrieved studies. A total of 79 articles were used for this review. Critical assessment for each article was independently performed by three reviewers.

Epidemiologic Evidence Linking OSA and SCD

There is a paucity of epidemiological data examining the association between OSA and SCD. This is largely attributed to the rarity of an adequately large cohort with availability of baseline information about OSA and a sufficient longitudinal follow-up period. Given that a sleep study is a prerequisite, it is impossible to derive any incident relationship in typical community-based cohorts that lack systematic OSA screening. This was overcome, however, in a clinic-based cohort study by Gami et al in which 10,701 adults who underwent clinically indicated sleep study in a single academic center were followed.25 During an average 5-year follow-up, the investigators found that the lowest nocturnal O2 saturation was independently, albeit modestly, predictive of SCD. Every 10% decrease in the lowest nadir O2 saturation (cohort mean, 93±3%) was associated with a 14% increase in the risk of SCD. Despite statistical adjustments, these results could have been driven by underlying cardiopulmonary conditions or body habitus, which are associated with both nadir O2 saturation and SCD.26 More traditional metrics such as apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) were not predictive of SCD in the study. This study represents the first of its kind to implicate OSA as a possible independent risk factor for SCD.

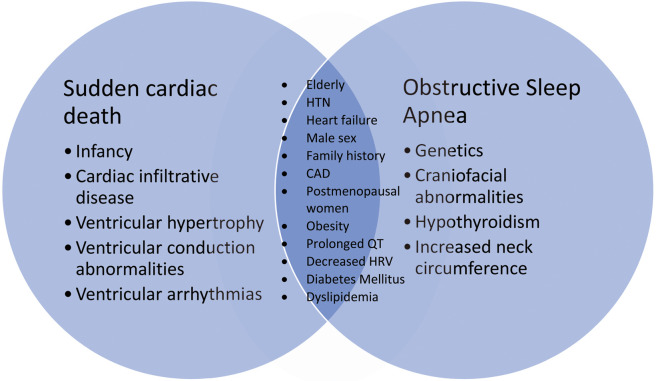

A growing body of evidence has elaborated on the connection between OSA and various forms of CVD.12,19–22 Individuals with OSA have a high burden of CVD, including CHF, which can serve as a substrate for SCD. Thus, CVD and its risk factors likely mediate the association between OSA and SCD. Research over the past two decades has identified many common risk factors shared by OSA and SCD that indirectly link the two entities (Figure 1).7,17,18,27–29

Figure 1.

Shared risk factors between sudden cardiac death and obstructive sleep apnea. CAD, coronary artery disease; HRV, heart rate variability; HTN, hypertension.

Impact of OSA on Nocturnal Sudden Death

Studies have brought to light a more specific link between OSA and SCD in the form of shifting day-night patterns of SCD in patient with OSA.30,31 A 2005 retrospective study found that the relative risk of SCD was 2.57-fold higher between midnight and 6 a.m. in patients with OSA compared with the general population;31 and, further, that this relative risk of SCD increased in proportion to the increasing severity of AHI.

Myocardial ischemia, a leading factor for SCD, is seen with a higher prevalence during nocturnal hours in patients with OSA.32,33 A prior cohort study found that patients with OSA who had myocardial infarctions (MI) were 6-fold more likely to have the MI between the hours of midnight and 6 a.m. than those without OSA.33 This change in the timing of MI may help explain, in part, the shifting day-night patterns of SCD in patients with OSA.

Even in the absence of CAD, nocturnal sudden death can still occur. The phenomenon of sudden unexplained nocturnal death in patients without known cardiac disease has been examined for more than a century.34 Mutations in SCN5A that alter repolarization and predispose individuals to ventricular arrhythmia have become increasingly recognized as a contributing factor in nocturnal sudden death.34,35 Patients with OSA are more likely to have nocturnal bradyarrhythmia than those without OSA,36 and have a higher frequency of ventricular ectopy.20,37 These electrophysiologic changes associated with OSA may contribute to nocturnal SCD in patients with channelopathies and altered repolarization.34,35

Common Pathophysiologic Connection Between OSA and SCD

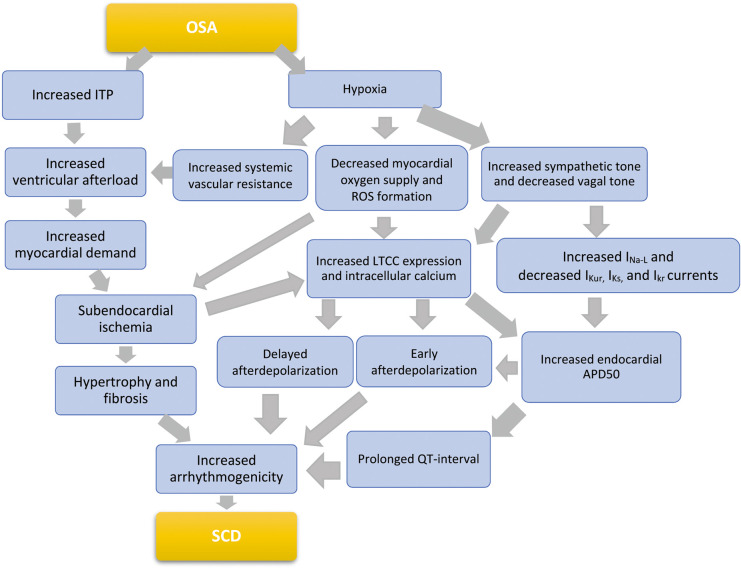

OSA is characterized by repeated episodes of pharyngeal airway obstruction during sleep. This obstructed breathing leads to a cascade of responses by the body driven by swings in intrathoracic pressure and hypoxia (Figure 2). The resulting negative intrathoracic pressure increases afterload and transmural cardiac pressure, thereby increasing myocardial oxygen demand and precipitating subendocardial ischemia. Through mechano-electrical feedback, this increased pressure exacerbates ventricular ectopy, raises sympathetic tone, and promotes arrhythmia.38 The summative impact of mechanical stress, ischemia, and oxidative stress causes upregulation of signaling kinases and transcription factors such as p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinases, MAPK, TNF-α, IGF-II, NF-κB, and IL-6. Maladaptive cardiac remodeling ensues with upregulation of apoptosis and subsequent myocardial hypertrophy.39–41

Figure 2.

Proposed complex pathophysiology connecting obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and sudden cardiac death (SCD). APD50, action potential duration 50%; IKr, rapid delayed rectifier current; IKs, slow delayed rectifier current; IKur, ultra rapid delayed rectifier current; INa-L, late sodium current; ITP, intrathoracic pressure; LTCC, L-type calcium channel; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Systemic hypoxia contributes to the subendocardial ischemia that sets the stage for the structural and electrical remodeling known to predispose to SCD.18 Additionally, intermittent hypoxia contributes to increased sympathetic tone in OSA through chemoreceptor and baroreceptor triggering, along with catecholamine release.19 Repeat apneas and awakenings over time can alter normal hemodynamics and cause inflammatory disturbances. The resulting cardiac remodeling can be a nidus for arrhythmia, independent from that caused by OSA acutely.

There are also changes in ventricular electrophysiological properties and cardiac ion channel expression brought about by hypoxia. Intermittent hypoxia in OSA increases expression of endocardial L-type calcium channels and prolongation of the corrected QT interval (QTc) and Tpeak-Tend intervals, which are known to predispose to ventricular arrhythmias.18,19,22 The increase in calcium channel expression is due to both hypoxia inducible factor-1 expression and direct catecholamine effects. Increasing intracellular calcium increases arrhythmogenicity via predisposing to early afterdepolarization (EAD)- and delayed afterdepolarization (DAD)-triggered activity, as well as by increasing the endocardial action potential duration (APD).23 Increased APD itself further increases the frequency of EAD, which, in combination with a prolonged QT interval, compounds arrhythmogenicity.19 AHI was also recently found to be inversely correlated with circulation potassium channel levels in patients with OSA, likely further contributing to prolonged cardiac repolarization.42

Bradycardia, atrial-ventricular block, and sinus arrest occur more often in patients with OSA,36 with any form of heart block occurring in approximately 10% of patients with OSA.43 Patients with OSA typically have a longer duration of heart block and at a higher frequency compared with age-matched controls.43,44 Bradycardia creates an electrophysiologic substrate that further increases the risk of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; a risk further compounded by prolonged APD and increased triggered activity (Figure 2).

Patients with OSA have an increased incidence of, and harder-to-control, AF.12,45 Separately, there is evidence that AF is an independent risk factor for SCD.46–49 In a large meta-analysis of 20,918 participants, AF was independently associated with an increased risk of SCD (HR, 2.47; 95% CI: 1.95–3.13; P<0.001).47 In the context of OSA, however, it is still unclear whether AF plays a direct role in SCD; acts as a compounding risk factor for SCD; or is simply an indicator of complex changes in the ECG substrate that occur in patients with OSA.

ECG Markers of SCD in Patients With OSA

There are multiple ECG markers of increased risk of SCD associated with OSA.20,50 These include PVC, increased heart rate “turbulence”, QT interval prolongation, AF, and T-wave alternans.20 Atrioventricular block has also been shown to be a frequent rhythm disturbance in OSA.43 Individuals with severe OSA have a higher risk of nocturnal cardiac arrhythmia including non-sustained ventricular tachycardia and complex ventricular ectopy.37 Patients with these ECG abnormalities have an approximate 2-fold increase in SCD during sleep.21

There are robust data on increased QTc and QTc dispersion in patients with OSA.22,46,51 Given the known association between prolonged QTc and the incidence of ventricular arrhythmia,52–54 it is possible that SCD in OSA is in part mediated by changes in ventricular repolarization in this population. Increasing severity of OSA has been shown to be related to degree of QT interval prolongation, albeit in a cohort of patients with congenital long QT syndrome.55 In a similar manner, the magnitude of QTc has a consistent relationship with the degree of hypoxia.56 Given the report of patients with OSA having a predilection for SCD during sleeping hours, dynamic change in QT during these times may contribute to these events.31,57

The influence that OSA has on ventricular repolarization can also be seen in abnormal frontal and spatial QRS-T angle in patients with OSA. A 2018 analysis found that higher AHI was associated with greater odds of abnormal QRS-T angle.58 It would be valuable to examine the prognostic and therapeutic implication of these ECG markers in patients with OSA. For example, patients with OSA and ventricular repolarization abnormality such as prolonged QTc or abnormal QRS-T angle may represent a higher risk subgroup for SCD.

OSA-induced hypoxia can cause ischemic changes on ECG in patients with underlying CAD.59 These changes were reported to be relieved by continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in one study.59 Changes have also been seen in acute MI, with an increase in PVC noted in OSA compared with non-OSA groups.60 Both ischemic ventricular arrhythmias from exposure to chronic intermittent hypoxia and the nocturnal arrhythmogenic state produced by alterations of the autonomic nervous system contribute to the increase in SCD in this patient population.19

OSA and SCD in Patients With CHF

Sleep apnea, namely OSA, central sleep apnea (CSA), and mixed-type apnea are common in patients with CHF. Patients with both OSA and CHF are at further risk of SCD, and may represent a unique population. In patients with CHF and an implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD), there is a higher prevalence of sleep apnea,61,62 and the rate of appropriate defibrillation for ventricular arrhythmia (a surrogate marker for SCD) is higher in patients with sleep apnea.48 Moreover, appropriate defibrillation in these patients has been seen to have a nocturnal predilection.63 This emerging pattern of increased nocturnal ICD therapy and SCD coupled with a known increase in QT interval and changes in ion channel activity in OSA patients with CHF deserves further evaluation.

Impact of Sleep Apnea Treatment on SCD

Studies examining the impact of nocturnal CPAP therapy on SCD are scarce. The SAVE study, which followed patients with known CVD or cerebrovascular disease and OSA for a mean of 3.7 years, found that therapy with CPAP plus usual care did not decrease the rate of composite cardiovascular events.64 SCD events were not assessed in that study. Intriguingly, the study remained non-significant even when only patients with >4 h of CPAP adherence were included.64

The recent SERVE-HF trial, which randomized patients with both CHF and CSA to treatment with adaptive servo continuous positive pressure ventilation vs. no therapy, examined appropriate ICD therapy as a component of the primary endpoint.65 Measurement of this outcome, however, which could be viewed as a surrogate for SCD, was not completed due to early termination of the trial.65 Interestingly, the investigators unexpectedly found that the treatment group had significantly higher rates of cardiovascular causes of death than the control group. This included death from CHF, MI, SCD, procedure-related death, stroke, and presumed cardiac cause of death.65 Consequently, no conclusion could be derived regarding whether treatment of CSA in patients with CHF would have any impact on SCD. The ongoing ADVENT-HF trial, which includes both patients with OSA and CSA, may provide more insight into this.66 In general, examining the therapeutic effects of intervention on SCD remains a challenge due to lack of power in typical clinical trials.

Impact of Sleep Apnea Treatment on Cardiovascular Outcomes

A 2018 meta-analysis examining the effects of CPAP on long-term cardiovascular outcomes in patients with CVD and OSA found that CPAP might prevent subsequent cardiovascular events.67 Specifically, treatment with CPAP was associated with a significantly lower risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in six of seven observational studies (RR, 0.61; 95% CI: 0.39–0.94, P=0.02).

A similar meta-analysis by Yu et al looked at 7,266 pooled patients with sleep apnea and found that CPAP use, compared with no treatment or sham, was not associated with reduced risk of composite cardiovascular outcomes or death.68 That meta-analysis conducted subgroup analysis for ≥4 h of adherence, and noted a significant reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events (RR, 0.58; 95% CI: 0.34–0.99). The authors of that study noted that the result may point to the importance of good CPAP adherence for achieving benefit, but also note that the result of the subgroup analysis could be related to chance. Other studies have found significantly better composite cardiovascular outcomes when patients had ≥4 h of CPAP use per night.69,70

In a 2018 randomized control trial of patients with OSA, a significant reduction was noted in QTc interval by 11.3 ms with therapeutic CPAP use.71 The change in QTc interval was most pronounced in patients with baseline QTc >430 ms and during the hours 6 p.m.–12 p.m.71 That study provides a biological underpinning for how CPAP therapy may influence SCD. In a separate randomized study looking at CPAP therapy for OSA in CHF patients, 1 month of CPAP therapy significantly reduced nocturnal hypoxia, urinary norepinephrine, and ventricular ectopy.72 These changes with CPAP therapy suggest a decrease in sympathetic nervous system tone. To date, no trials have been conducted that examine the impact of OSA treatment on SCD directly in the general population. The studies discussed here, however, provide an indirect look at the interactions between the entities.

Influence of Normal Sleep on Arrhythmogenicity

Even in the absence of pathologic sleep, there are sleep stage-dependent shifts in autonomic nervous system activity. Increased baroreceptor gain and vagal tone during non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) sleep increase the frequency of sinus arrhythmia and bradycardia.73 In the context of QT interval prolongation, repolarization abnormalities, and triggered activity, hypothetically, these bradyarrhythmias can generate an electrophysiologic substrate for polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.34,74

With transition to REM sleep, specifically during phasic REM, sympathetic nervous system activity increases.73,75 Although REM sleep is generally considered a sympathetic nervous system-dominant state, it also involves bursts of vagal activity, making it a period of bradyarrythmias such as sinus pause.

Physiologic sleep affects arrhythmogenicity at the molecular level. In mice models, circadian rhythm was found to influence the expression of Krüppel-like factor 15, and, thus, kChIP2 (a voltage-gated potassium channel), which modulates ventricular repolarization normally, and can contribute to arrhythmogenicity.76 Additional work also found that the circadian rhythm controls expression of voltage-gated sodium channels in ventricular cardiomyocytes, resulting in QRS prolongation and slowing of heart rate.77 Changes in the complex molecular clock mediated via the circadian rhythm produce electrophysiologic changes that, in the setting of underlying cardiac disease, promote arrhythmia and may contribute to nocturnal SCD.76,78 Therefore, the sleep state itself, independent of OSA, brings on physiologic changes that increase susceptibility to SCD.

Future Research Goals and Ongoing Studies

With the growing body of evidence elucidating the relationship between OSA and SCD, there has been a resultant rise in the number of published works involving these two conditions. There are few ongoing observational studies or clinical trials investigating their direct relationship, however, and no studies to date have been conducted using SCD as the endpoint in patients with OSA. In light of the difficulty in designing an adequately powered study evaluating the impact of OSA treatment on SCD in the general population, identification of high-risk groups would be important. Such groups may include patients with OSA who have established CAD, CHF, or baseline ECG abnormalities who could be more prone to adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Two pertinent clinical trials are focusing on these patient populations. A European group is currently investigating patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and OSA to further elaborate on the nature of OSA as an independent risk factor for SCD. The group is also examining if treatment of OSA with CPAP decreases the risk of SCD in ischemic cardiomyopathy patients (European Sleep Apnea and Sudden Cardiac Death Project; ESCAPE-SCD).

A separate group is targeting patients with long QT syndrome and OSA to elaborate on the extent that OSA is associated with QT prolongation, which has been posited as a key mechanism of SCD. Further, they aim to investigate the extent that treatment with CPAP changes QT prolongation (Long QT Syndrome and Sleep Apnea).79

More large-scale studies with long follow-up periods are needed to better understand the risk that OSA carries for SCD in specific patient populations, in addition to studies that further elaborate on the role of OSA in arrhythmogenicity.

Conclusions

The link between OSA and SCD is highly complex, and involves myocardial ischemia, maladaptive autonomic nervous system changes, altered ion channel expression, increased arrhythmogenicity, and hemodynamic shifts that act in a way that raises the biologic plausibility for a convincing link between the two conditions. There is a paucity of evidence, however, for a direct link between the two at a population level.

Recent studies underscore an interaction between sleep and SCD, but do not allow for clear conclusions on causation to be made. A growing body of evidence supports the ongoing investigation of the influence of OSA treatment on markers of SCD in both the general population and those with CVD.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by NIH R21HL140432 (Y.K.).

References

- 1. Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA.. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J 2011; 32: 1484–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kwok CS, Kontopantelis E, Kuligowski G, Gray M, Muhyaldeen A, Gale CP, et al.. Self-Reported sleep duration and quality and cardiovascular disease and mortality: A dose-response meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2018; 7: e008552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Redline S, Yenokyan G, Gottlieb DJ, Shahar E, O’Connor GT, Resnick HE, et al.. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and incident stroke: The sleep heart health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182: 269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tobaldini E, Costantino G, Solbiati M, Cogliati C, Kara T, Nobili L, et al.. Sleep, sleep deprivation, autonomic nervous system and cardiovascular diseases. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017; 74: 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gottlieb DJ, Yenokyan G, Newman AB, O’Connor GT, Punjabi NM, Quan SF, et al.. Prospective study of obstructive sleep apnea and incident coronary heart disease and heart failure: The sleep heart health study. Circulation 2010; 122: 352–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Senaratna CV, Perret JL, Lodge CJ, Lowe AJ, Campbell BE, Matheson MC, et al.. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 2017; 34: 70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garvey JF, Pengo MF, Drakatos P, Kent BD.. Epidemiological aspects of obstructive sleep apnea. J Thorac Dis 2015; 7: 920–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J.. Longitudinal study of moderate weight change and sleep-disordered breathing. JAMA 2000; 284: 3015–3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM.. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 177: 1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Young T, Peppard PE, Taheri S.. Excess weight and sleep-disordered breathing. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2005; 99: 1592–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Punjabi NM.. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008; 5: 136–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kwon Y, Koene RJ, Johnson AR, Lin GM, Ferguson JD.. Sleep, sleep apnea and atrial fibrillation: Questions and answers. Sleep Med Rev 2018; 39: 134–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kwon Y, Gharib SA, Biggs ML, Jacobs DR, Alonso A, Duprez D, et al.. Association of sleep characteristics with atrial fibrillation: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Thorax 2015; 70: 873–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Peker Y, Carlson J, Hedner J.. Increased incidence of coronary artery disease in sleep apnoea: A long-term follow-up. Eur Respir J 2006; 28: 596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zipes DP, Wellens HJ.. Sudden cardiac death. Circulation 1998; 98: 2334–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Benjamin E, Virani S, Callaway C, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, et al.. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2018 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018; 137: e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adabag AS, Luepker RV, Roger VL, Gersh BJ.. Sudden cardiac death: Epidemiology and risk factors. Nat Rev Cardiol 2010; 7: 216–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deo R, Albert CM.. Epidemiology and genetics of sudden cardiac death. Circulation 2012; 125: 620–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morand J, Arnaud C, Pepin JL, Godin-Ribuot D.. Chronic intermittent hypoxia promotes myocardial ischemia-related ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Raghuram A, Clay R, Kumbam A, Tereshchenko LG, Khan A.. A systematic review of the association between obstructive sleep apnea and ventricular arrhythmias. J Clin Sleep Med 2014; 10: 1155–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schlatzer C, Bratton DJ, Craig SE, Kohler M, Stradling JR.. ECG risk markers for atrial fibrillation and sudden cardiac death in minimally symptomatic obstructive sleep apnoea: The MOSAIC randomised trial. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e010150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shamsuzzaman A, Amin RS, van der Walt C, Davison DE, Okcay A, Pressman GS, et al.. Daytime cardiac repolarization in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath 2015; 19: 1135–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chadda KR, Fazmin IT, Ahmad S, Valli H, Edling CE, Huang CLH, et al.. Arrhythmogenic mechanisms of obstructive sleep apnea in heart failure patients. Sleep 2018; 41: zsy136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nakamura T, Chin K, Hosokawa R, Takahashi K, Sumi K, Ohi M, et al.. Corrected QT dispersion and cardiac sympathetic function in patients with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Chest 2004; 125: 2107–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gami AS, Olson EJ, Shen WK, Wright RS, Ballman KV, Hodge DO, et al.. Obstructive sleep apnea and the risk of sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62: 610–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adabag S, Huxley RR, Lopez FL, Chen LY, Sotoodehnia N, Siscovick D, et al.. Obesity related risk of sudden cardiac death in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Heart 2015; 101: 215–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guralnick AS.. Obstructive sleep apnea: Incidence and impact on hypertension? Curr Cardiol Rep 2013; 15: 415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Newman AB, Foster G, Givelber R, Nieto FJ, Redline S, Young T.. Progression and regression of sleep-disordered breathing with changes in weight: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165: 2408–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lin YN, Li QY, Zhang XJ.. Interaction between smoking and obstructive sleep apnea: Not just participants. Chin Med J (Engl) 2012; 125: 3150–3156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martins EF, Martinez D, da Silva FABS, Sezerá L, da Rosa de Camargo R, Fiori CZ, et al.. Disrupted day-night pattern of cardiovascular death in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med 2017; 38: 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gami AS, Howard DE, Olson EJ, Somers VK.. Day–night pattern of sudden death in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1206–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Myerburg RJ, Junttila MJ.. Sudden cardiac death caused by coronary heart disease. Circulation 2012; 125: 1043–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kuniyoshi FHS, Garcia-Touchard A, Gami AS, Romero-Corral A, van der Walt C, Pusalavidyasagar S, et al.. Day-night variation of acute myocardial infarction in obstructive sleep apnea. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52: 343–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zheng J, Zheng D, Su T, Cheng J.. Sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome: The hundred years’ enigma. J Am Heart Assoc 2018; 7: e007837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tobaldini E, Brugada J, Benito B, Molina I, Montserrat J, Kara T, et al.. Cardiac autonomic control in Brugada patients during sleep: The effects of sleep disordered breathing. Int J Cardiol 2013; 168: 3267–3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Becker H, Brandenburg U, Peter JH, Von Wichert P.. Reversal of sinus arrest and atrioventricular conduction block in patients with sleep apnea during nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 151: 215–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mehra R, Benjamin EJ, Shahar E, Gottlieb DJ, Nawabit R, Kirchner HL, et al.. Association of nocturnal arrhythmias with sleep-disordered breathing: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173: 910–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Franz MR.. Mechano-electrical feedback. Cardiovasc Res 2000; 45: 263–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen LM, Kuo WW, Yang JJ, Wang SGP, Yeh YL, Tsai FJ, et al.. Eccentric cardiac hypertrophy was induced by long-term intermittent hypoxia in rats. Exp Physiol 2007; 92: 409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spooner PM, Albert C, Benjamin EJ, Boineau R, Elston RC, George AL, et al.. Sudden cardiac death, genes, and arrhythmogenesis: Consideration of new population and mechanistic approaches from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop, part I. Circulation 2001; 103: 2361–2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vgontzas AN, Papanicolaou DA, Bixler EO, Kales A, Tyson K, Chrousos GP.. Elevation of plasma cytokines in disorders of excessive daytime sleepiness: Role of sleep disturbance and obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997; 82: 1313–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jiang N, Zhou A, Prasad B, Zhou L, Doumit J, Shi G, et al.. Obstructive sleep apnea and circulating potassium channel levels. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5: e003666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Koehler U, Fus E, Grimm W, Pankow W, Schäfer H, Stammnitz A, et al.. Heart block in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: Pathogenetic factors and effects of treatment. Eur Respir J 1998; 11: 434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bjerregaard P.. Mean 24 hour heart rate, minimal heart rate and pauses in healthy subjects 40–79 years of age. Eur Heart J 1983; 4: 44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhang L, Hou Y, Po SS.. Obstructive sleep apnoea and atrial fibrillation. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2015; 4: 14–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Voigt L, Haq SA, Mitre CA, Lombardo G, Kassotis J.. Effect of obstructive sleep apnea on QT dispersion: A potential mechanism of sudden cardiac death. Cardiology 2011; 118: 68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen LY, Sotoodehnia N, Bůžková P, Lopez FL, Yee LM, Heckbert SR, et al.. Atrial fibrillation and the risk of sudden cardiac death: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study and Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS). JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173: 29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kwon Y, Koene RJ, Kwon O, Kealhofer JV, Adabag S, Duval S.. Effect of sleep-disordered breathing on appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2017; 10: e004609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen LY, Benditt DG, Alonso A.. Atrial fibrillation and its association with sudden cardiac death. Circ J 2014; 78: 2588–2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kwon Y, Picel K, Adabag S, Vo T, Taylor BC, Redline S, et al.. Sleep-disordered breathing and daytime cardiac conduction abnormalities on 12-lead electrocardiogram in community-dwelling older men. Sleep Breath 2016; 20: 1161–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Çiçek D, Lakadamyali H, Gökay S, Sapmaz I, Muderrisoglu H.. Effect of obstructive sleep apnea on heart rate, heart rate recovery and QTc and P-wave dispersion in newly diagnosed untreated patients. Am J Med Sci 2012; 344: 180–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yap YG, Camm AJ.. Drug induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. Heart 2003; 89: 1363–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Elming H, Holm E, Jun L, Torp-Pedersen C, Køber L, Kircshoff M, et al.. The prognostic value of the QT interval and QT interval dispersion in all-cause and cardiac mortality and morbidity in a population of Danish citizens. Eur Heart J 1998; 19: 1391–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. de Bruyne MC, Hoes AW, Kors JA, Hofman A, van Bemmel JH, Grobbee DE.. Prolonged QT interval predicts cardiac and all-cause mortality in the elderly: The Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J 1999; 20: 278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shamsuzzaman AS, Somers VK, Knilans TK, Ackerman MJ, Wang Y, Amin RS.. Obstructive sleep apnea in patients with congenital long QT syndrome: Implications for increased risk of sudden cardiac death. Sleep 2015; 38: 1113–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Latshang TD, Kaufmann B, Nussbaumer-Ochsner Y, Ulrich S, Furian M, Kohler M, et al.. Patients with obstructive sleep apnea have cardiac repolarization disturbances when travelling to altitude: Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of acetazolamide. Sleep 2016; 39: 1631–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gillis AM, Stoohs R, Guilleminault C.. Changes in the QT interval during obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 1991; 14: 346–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kwon Y, Misialek JR, Duprez D, Jacobs DR, Alonso A, Heckbert SR, et al.. Sleep-disordered breathing and electrocardiographic QRS-T angle: The MESA study. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2018; 23: e12579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Franklin KA, Sahlin C, Nilsson JB, Näslund U.. Sleep apnoea and nocturnal angina. Lancet 1995; 345: 1085–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Kogan I.. Obstructive sleep apnea and acute myocardial infarction: Clinical implications of the association. Sleep 1998; 21: 809–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Javaheri S.. Sleep disorders in systolic heart failure: A prospective study of 100 male patients. The final report. Int J Cardiol 2006; 106: 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Grimm W, Apelt S, Timmesfeld N, Koehler U.. Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Europace 2013; 15: 515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Serizawa N, Yumino D, Kajimoto K, Tagawa Y, Takagi A, Shoda M, et al.. Impact of sleep-disordered breathing on life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia in heart failure patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Am J Cardiol 2008; 102: 1064–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. McEvoy RD, Antic NA, Heeley E, Luo Y, Ou Q, Zhang X, et al.. CPAP for prevention of cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 919–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K, Angermann C, d’Ortho MP, Erdmann E, et al.. Adaptive servo-ventilation for central sleep apnea in systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1095–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. US National Library of Medicine.. Effect of adaptive servo ventilation (ASV) on survival and hospital admissions in heart failure (ADVENT-HF). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01128816 (accessed September 28, 2019).

- 67. Wang X, Zhang Y, Dong Z, Fan J, Nie S, Wei Y.. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on long-term cardiovascular outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease and obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res 2018; 19: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yu J, Zhou Z, McEvoy RD, Anderson CS, Rodgers A, Perkovic V, et al.. Association of positive airway pressure with cardiovascular events and death in adults with sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2017; 318: 156–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Barbé F, Durán-Cantolla J, Sánchez-de-la-Torre M, Martínez-Alonso M, Carmona C, Barceló A, et al.. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on the incidence of hypertension and cardiovascular events in nonsleepy patients with obstructive sleep apnea: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012; 307: 2161–2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Peker Y, Glantz H, Eulenburg C, Wegscheider K, Herlitz J, Thunström E.. Effect of positive airway pressure on cardiovascular outcomes in coronary artery disease patients with nonsleepy obstructive sleep apnea: The RICCADSA Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194: 613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schlatzer C, Bratton DJ, Schwarz EI, Gaisl T, Pepperell JCT, Stradling JR, et al.. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure therapy on circadian patterns of cardiac repolarization in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: Data from a randomized trial. J Thorac Dis 2018; 10: 4940–4948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ryan CM, Usui K, Floras JS, Bradley TD.. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on ventricular ectopy in heart failure patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax 2005; 60: 781–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Somers VK, Dyken ME, Clary MP, Abboud FM.. Sympathetic neural mechanisms in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Invest 1995; 96: 1897–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. van den Berg MP, Wilde AA, Viersma TJW, Brouwer J, Haaksma J, van der Hout AH, et al.. Possible bradycardic mode of death and successful pacemaker treatment in a large family with features of long QT syndrome type 3 and Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2001; 12: 630–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Elsenbruch S, Harnish MJ, Orr WC.. Heart rate variability during waking and sleep in healthy males and females. Sleep 1999; 22: 1067–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Jeyaraj D, Haldar SM, Wan X, McCauley MD, Ripperger JA, Hu K, et al.. Circadian rhythms govern cardiac repolarization and arrhythmogenesis. Nature 2012; 483: 96–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Schroder EA, Lefta M, Zhang X, Bartos DC, Feng HZ, Zhao Y, et al.. The cardiomyocyte molecular clock, regulation of Scn5a, and arrhythmia susceptibility. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2013; 304: C954–C965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Schroder EA, Burgess DE, Zhang X, Lefta M, Smith JL, Patwardhan A, et al.. The cardiomyocyte molecular clock regulates the circadian expression of Kcnh2 and contributes to ventricular repolarization. Heart Rhythm 2015; 12: 1306–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. US National Library of Medicine.. Long QT syndrome and sleep apnea. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03678311 (accessed November 14, 2018).