Abstract

The Ebola virus is a human aggressive pathogen causes Ebola virus disease that threatens public health, for which there is no Food Drug Administration approved medication. Drug repurposing is an alternative method to find the novel indications of known drugs to treat the disease effectively at low cost. The present work focused on understanding the host–virus interaction as well as host virus drug interaction to identify the disease pathways and host-directed drug targets. Thus, existing direct physical Ebola–human protein–protein interaction (PPI) was collected from various publicly available databases and also literature through manual curation. Further, the functional and pathway enrichment analysis for the proteins were performed using database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery and the enriched gene ontology biological process terms includes chromatin assembly or disassembly, nucleosome organization, nucleosome assembly. Also, the enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome pathway terms includes systemic lupus erythematosus, alcoholism, and viral carcinogenesis. From the PPI network, important large histone clusters and tubulin were observed. Further, the host–virus and host–virus–drug interaction network has been generated and found that 182 drugs are associated with 45 host genes. The obtained drugs and their interacting targets could be considered for Ebola treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13337-020-00570-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Drug repurposing, Zaire Ebola virus, Host–virus interaction, Protein–protein interaction

Introduction

Ebola virus is a non-segmented negative sense and single-stranded RNA virus belongs to the Filoviridae family which causes Ebola virus disease (EVD). It’s a contagious disease through contact with body fluids, blood or consumption of infected animal’s meat. The virus enters through the mucous membrane via mouth, eyes, ears, open wounds either by direct or indirect contact of the infected source [13]. Moreover, it is reported that Ebola hemorrhagic fever resulted in mortality rate up to 90% in human as well as non-human primates (NHPs) [28, 43]. The virus family has been classified into five species named after the origin of the outbreaks, such as Zaire ebolavirus (ZEBOV), Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV), Tai Forest ebolavirus (TAFV), Bundibugyo ebolavirus (BDBV) and Reston ebolavirus (RESTV). Recent studies report the outbreak of the Ebola in Western Africa and is deadly destructive [3]. Among all the Ebola species, only RESTV does not cause disease in humans [7]. The genome size of the virus is approximately 19 kb and encodes seven structural proteins such as, envelop glycoprotein (GP), membrane-associated virion protein (VP24), transcription activator (VP30), polymerase cofactor (VP35), matrix protein (VP40), nucleoprotein (NP) and RNA dependent RNA polymerase (L) [49]. Even though Ebola has been reported in 1976, still the pathogenesis of the virus remains unclear [45].

Also, the requirement of Biosafety Level 4 (BSL4) facility for conducting the preclinical studies [38] make the process of designing a drug for Ebola becomes tedious. Further, the conventional drug discovery process takes more than 15 years with an approximate amount of $1.5 billion to bring out an effective drug successfully. Identifying and developing new drugs is an effort and time-consuming process at a higher cost. In a conventional drug designing procedure, only 35% of new drugs are approved by regulatory agencies [10]. Such limitations led the researchers to focus on drug repurposing which may have new disease indications for other treatment. However, no recent research has been reported on the availability of approved therapeutic and licensed drugs for the treatment of EVD. Although, ZMapp and GS-5734 have been encouraged to treat Ebola in the ongoing clinical trials [2].

Drug repurposing is the process to find the new function of existing drugs with an advantage of ready to use with already satisfied basic absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity (ADMET) properties. Thus, the main challenge of drug repurposing is to study the effectiveness of established approved drugs [13]. Host-directed therapies (HDT) is an emerging method targeting the host terrain which interferes the host cell factors and vital for pathogen survival in the host framework. In spite of the fact that HDTs incorporating interferon’s are entrenched for the treatment of chronic viral hepatitis, hence novel method need to proceed to cure viral infections and the improvement of expansive range antivirals is essential against the rising infections [20].

Therefore, in the current study, 182 drugs associated with 45 host genes were found to have direct interaction with viral proteins. In addition, the obtained drugs are classified as microtubule inhibitors, estrogen receptors, antihistamines and pump/channels.

Materials and methods

Data collection

The EVD has continuously been re-emerging for almost 50 years in the African continent to cause contagious and highly fateful hemorrhagic fever. Significant challenges ahead to govern, control and managing future epidemics and patient care, particularly in remote areas where typically Ebola reemerges [24]. For the current study, the proteins/genes involved in Ebola human interactions were collected from experimentally reported literature and databases and also abstracts of original publications describing an experimental proof of the association of human host proteins with Zaire Ebola virus. The term “Ebola” or specific Ebola protein along with the keywords like Ebola interaction, Ebola virus infection, an inhibitor of ebola, Ebola viral protein, viral receptor and human host with “Yeast two hybridization and ebola”, “co-immune precipitation” were used as a search query. The proteins were also collected from various databases such as VirusMentha [4], VirHostNet [16] and IntAct [17]. The overall workflow of the study is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Host proteins overlapping analysis

To remove duplicates, the collected data are subjected to overlapping analysis using Venny v2.0 [33], an interactive tool for comparison (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html).

Enrichment analysis

Database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery (DAVID) tool [9] incorporated the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome (KEGG) database [19] was utilized to carry out the functional and pathway enrichment analysis of the interacted proteins/genes in the protein–protein interaction network [26]. Where, functional annotation analysis includes a cellular component (CC), molecular function (MF) and biological process (BP). p < 0.05 was considered as statistical significance.

Protein–protein interaction analysis

To understand the interaction of host proteins; a network is generated by The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database [42]. Where, the STRING database gives the experimental and predicted information on protein–protein interaction (PPI), which is based on neighborhood, gene fusion, and co-occurrence, and co-expression, experimental evidence from various other databases such as IntAct [21], BioGrid [6], HPRD [34], and MINT [5].

Module and enrichment analysis

To study the protein complexes and its functional modules among the Ebola interacted human proteins [42], the top three modules were identified using MCODE Cytoscape plugin. The default parameters such as degree cutoff 2, node score cut off = 0.2, K-core = 2 and max. Depths = 100 are used for top three cluster generation. Further, these clusters were analyzed for their functional and pathway annotation using ClueGO plugin version 2.3.5 [1] in Cytoscape. It integrates GO terms as well as KEGG/Biocarta pathways and creates functionally enriched network. It can take one or two list of genes and analyze and comprehensively visualize the gene enrichment as network and chart. Enrichment analysis was calculated by right-sided hypergeometric with Benjamini–Hochberg correction and kappa score of 0.3.

Host–virus interaction network

To understand the Ebola-protein interaction with humans during infection, a host–virus interaction network was constructed by interrogating host factors using Cytoscape v3.4.0 [39]. The dataset imported by excel files which contain host and viral genes.

Host–virus–drug interaction network

Further, host–virus–drug interaction network is generated using CyTargetLinker, a Cytoscape plug-in, and an open source which provides a user-friendly interface to study biological regulatory networks such as microRNA-target, transcription factor-target analysis, and drug-target.

Results

Host gene overlapping analysis

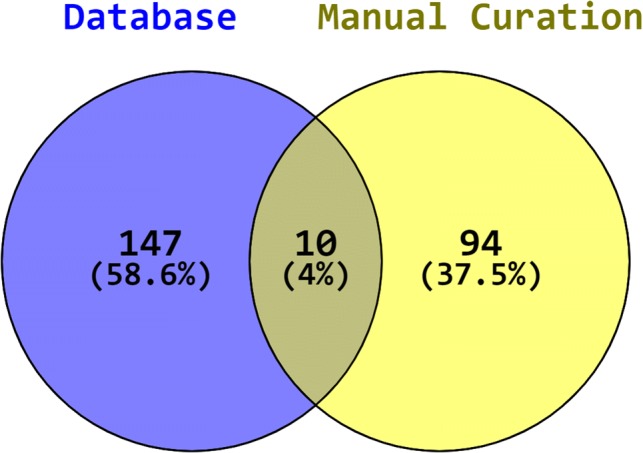

The collected data are preprocessed in order to remove the duplicates. In total, 270 genes are obtained out of 157 from databases and 104 by manual curation as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

List of curated host factors affected during EVD infection. An overlap of 10 genes and self-overlapping genes on both side of the Venn diagram found but interactions are with different targets

Pathway enrichment analysis

From the network, the pathways enriched are, systemic lupus erythematosus, alcoholism, viral carcinogenesis, influenza A, hepatitis C, protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, spliceosome, pathogenic Escherichia coli infection, measles, hepatitis B tabulated as Supplementary Table 1. Gene ontology terms are associated with, Chromatin assembly or disassembly, nucleosome organization, nucleosome assembly, chromatin assembly, protein–DNA complex assembly, DNA packaging, cellular macromolecular complex assembly, cellular macromolecular complex subunit organization tabulated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Top 10 enriched Gene Ontology (biological process) of host–Zaire Ebola virus infection

| Term | Category | Description | Count | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0006333 | BP | Chromatin assembly or disassembly | 35 | 1.78 × 10−33 |

| GO:0034728 | BP | Nucleosome organization | 31 | 2.39 × 10−32 |

| GO:0006334 | BP | Nucleosome assembly | 30 | 2.73 × 10−32 |

| GO:0031497 | BP | Chromatin assembly | 30 | 9.03 × 10−32 |

| GO:0065004 | BP | Protein–DNA complex assembly | 30 | 4.10 × 10−31 |

| GO:0006323 | BP | DNA packaging | 32 | 2.08 × 10−30 |

| GO:0034622 | BP | Cellular macromolecular complex assembly | 44 | 5.13 × 10−29 |

| GO:0034621 | BP | Cellular macromolecular complex subunit organization | 45 | 5.70 × 10−28 |

| GO:0006325 | BP | Chromatin organization | 38 | 4.79 × 10−20 |

| GO:0065003 | BP | Macromolecular complex assembly | 48 | 1.73 × 10−19 |

Protein–protein interaction analysis

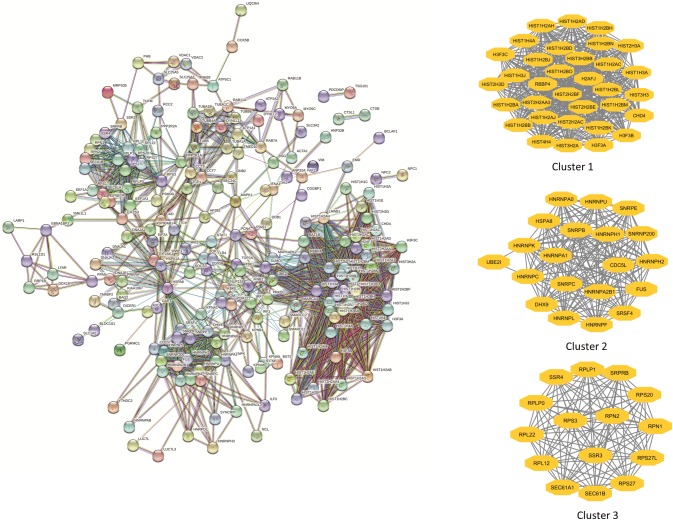

PPI network is generated for Ebola interacted human proteins for understanding virus-associated protein functional complexes with a confidence score of 0.70 (high confidence) consists of 246 nodes and 1518 edges and top three sub modules generated by MCODE are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Construction of PPI network using experimental data for the interaction of host protein with Ebola on the basis of protein–protein interaction. The top three sub clusters are generated by as represented as yellow diamond (color figure online)

Identification of modules and their enrichment

The top thee modules are selected with MCODE score for cluster 1 (score = 31.438, nodes = 33, edges = 503), cluster 2 (score = 18.211, nodes = 20, edges = 173), cluster 3 (score = 15, nodes = 15, edges = 105). Next, gene ontology for these modules were further analyzed using ClueGO (Fig. 3). The enriched terms are IRE-1 mediated unfold protein response, ribosome assembly, innate immune response, spliceosome snRNA assembly, negative regulation of gene expression epigenetic, SRP dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membrane, chromatin assembly and disassembly, mRNA stabilization, RNA splicing via transesterification reactions with bulged adenosine as nucleophile, chromatin silencing.

Fig. 3.

The sub clusters generated by MCODE are visualized in CluGO for gene enrichment, cluster 1 represented by green color, cluster 2 represented by green blue, cluster 3 represented by red color (color figure online)

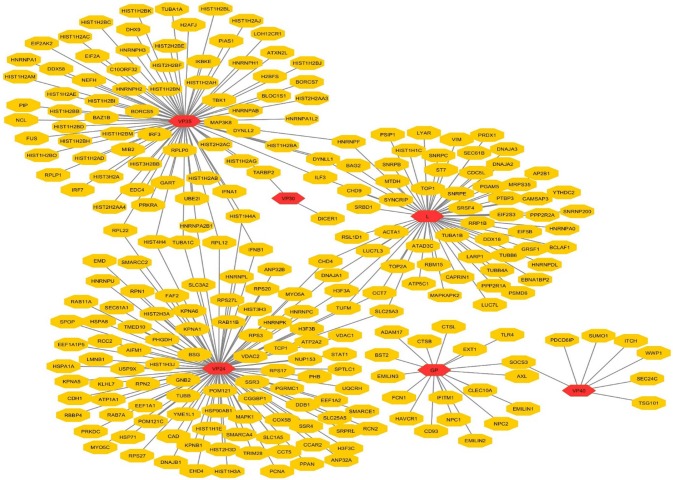

Host–virus interaction network

Out of collecting host factors interacted with ZEBOV, 270 host genes are obtained by combining 163 host genes identified from databases and 107 from the experimentally reported literatures. Finally, the proteins/genes were inputted in Cytoscape and the network was constructed which consists of 257 nodes and 270 edges. From 270 host factors, 18 are found to interact with Glycoprotein (GP), 103 interact with VP24, 2 with VP30, 78 with VP35, 7 with VP40 and 62 host factors with L (RNA dependent RNA polymerase) viral protein as shown in Table 2 and Fig. 4.

Table 2.

Total number of human proteins involved in direct interactions with Ebola proteins

| S. no. | Virus protein | Number of interacting human genes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | GP | 18 |

| 2. | VP24 | 103 |

| 3. | VP30 | 02 |

| 4. | VP35 | 78 |

| 5. | VP40 | 07 |

| 6. | L | 62 |

Fig. 4.

Direct interaction network of host protein-virus using Cytoscape v3.5.1 Red hexagons represent Ebola proteins and yellow represents host proteins human genes (color figure online)

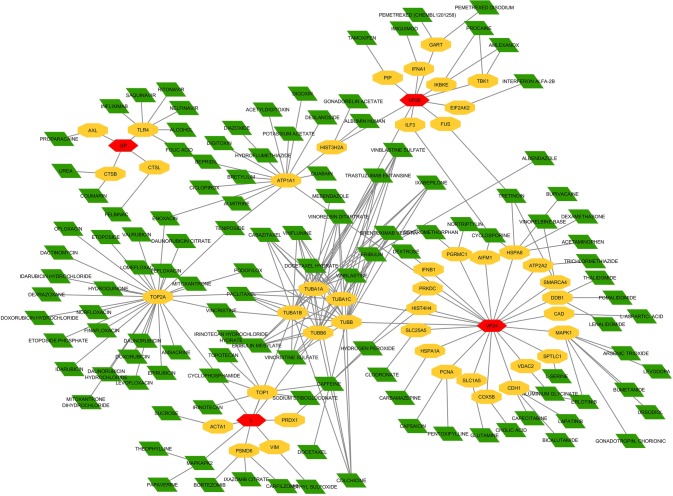

Host–virus–drug interaction

The constructed host–virus interaction network is considered to generate the drug-host interaction network. The network is generated to find the alternative drugs which interact with a host may inhibit ZEBOV replication and infection. The drugs interacted with the set of 270 host factors are queried using DGIdb [8] and CyTargetlinker, a Cytoscape based plug-in as shown in Supplementary Table 2 and Fig. 5. EBOV-host interaction associated repurposed drugs listed are based on the multi-targeted host–virus–drug interaction (Table 3 and Fig. 6) (Supplementary Table 3). In total, 270 Zaire Ebola viruses associated host genes are collected out of where 163 genes are derived from databases and 107 from the literature survey. From the host–virus–drug network, it is noticed these 182 drugs in teract with 45 host gene targets.

Fig. 5.

The network of direct physical interactions of virus–host–drug using Cytoscape v3.5.1 red hexagons represent Zaire Ebola viral proteins, yellow represents human genes and green diamond represents drugs (color figure online)

Table 3.

List of repurposed drugs

| S. No. | Drugs name | Human gene name | Viral gene name | Description of the drug |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Paclitaxel |

TUBA1C TUBB |

VP24 | Paclitaxel is an FDA approved cancer drug, the main function of this drug is to stabilize microtubule and induce the mitotic arrest which causes cell death [48]. It initiates the apoptosis by binding specifically interacting tubulin [40] |

| TUBA1A | VP35 | |||

|

TUBA1B TUBB6 TOP2A |

L | |||

| 2. | Vincristine sulfate |

TUBA1C TUBB |

VP24 | The mechanism of vincristine sulfate inhibits the function of mitotic spindle formation which leads to the arrest of cells in the metaphase stage [11] |

| TUBA1A | VP35 | |||

|

TUBA1B TUBB6 |

L | |||

| 3. | Vinblastine sulfate |

TUBA1C TUBB |

VP24 | Vinblastin is tubulin binding molecules used for anti-tumor drugs [47] |

| TUBA1A | VP35 | |||

|

TUBA1B TUBB6 |

L | |||

| 4. | Eribulin mesylate |

TUBA1C TUBB |

VP24 | Eribulin mesylate is the novel inhibitor that interferes with the microtubule dynamics [15] |

| TUBA1A | VP35 | |||

|

TUBA1B TUBB6 |

L | |||

| 5. | Docetaxel hydrate |

TUBA1C TUBB |

VP24 | Docetaxel interferes with the normal function of microtubule dynamics [29] |

| TUBA1A | VP35 | |||

|

TUBA1B TUBB6 |

L | |||

| 6. | Tretinoin |

HSPA8, SMARCA4 |

VP24 | Used in acne treatment and involved in opsonization of the immune system [37] |

| FUS | VP35 | |||

| 7. | Cyclosporine |

AFM1 HSPA8 |

VP24 | Interact with heat shock protein [30] |

| ILF3 | VP35 | |||

| 8. | Enoxacin | ATP1A1 | VP24 | Enoxacin interact with topoisomerase II [22] |

| TOP2A | L | |||

| 9. | Hydrogen peroxide | HIST4H4 | VP24 | HSV-1 shown sensitive by treatment of Hydrogen Peroxide in the presence of catalase inhibitor [32] |

| PRDX1 | L | |||

| 10. | Teniposide | HIST3H2A | VP35 | Teniposide interacting with topoisomerase II, which leads to inhibition of DNA synthesis. It interferes with the cell cycle at S or early G2 phase, this prevents the cells from entering mitosis [46] |

| TOP2A | L | |||

| 11. | Caffeine | PRKDC | VP24 | Caffeine is efficient suppresses the DNA. Repair and DNA damage-activated checkpoints. This inhibits retroviral transduction [31] |

| TOP1 | L | |||

| 12. | Podofilox | TUBB | VP24 | Interfere with the function of topoisomerase [18] |

| TOP2A | L |

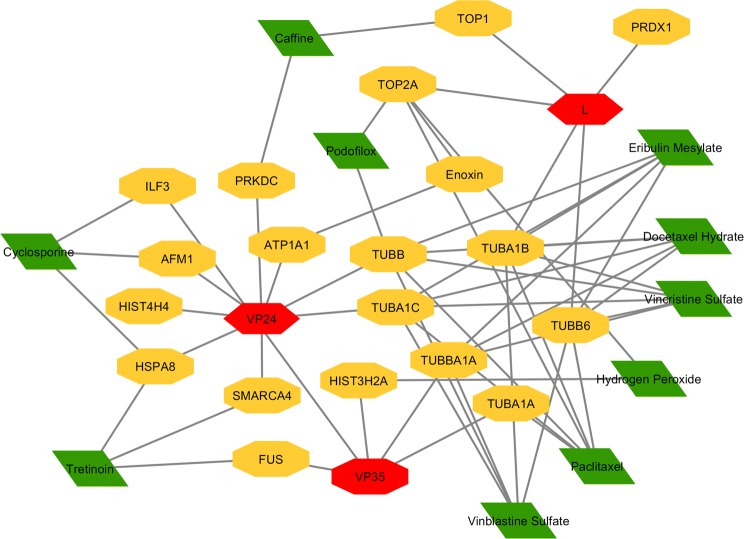

Fig. 6.

The repurposed drugs has connection more than one connection, red hexagons represent Zaire Ebola viral proteins, yellow represents human genes and green diamond represents drugs (color figure online)

Out of 45 targets, which have more than one connection are selected with criteria the targets which have more than one. Paclitaxel, vincristine sulfate vinblastine, sulfate, eribulin mesylate, docetaxel hydrate, tretinoin, cyclosporine, enoxacin, hydrogen peroxide, teniposide, caffeine, podofilox drug have more interactions among 182 drugs and may have the property to inhibit the of ebola. Most of these drugs are microtubule inhibitors used for the cancer treatment, and remaining classes of drugs are used for acne, rheumatoid arthritis, urinary tract infection, fatigue, and genital warts.

Discussion

Ebola virus is a life threatening virus, where there is no approved medication and they depend on host cell machinery to promote their replications, thus it is necessary to understand the mechanism of pathogenesis. In the present study, the data consisting of existing direct physical Ebola–human protein–protein interaction (PPI) were collected to build the host–virus network and drug host virus interaction to predict the therapeutic targets. Also, gene ontology results indicate that the genes are mainly enriched in chromatin assembly or disassembly, Nucleosome organization, Nucleosome assembly, Protein–DNA complex assembly, DNA packing, cellular macromolecular complex assembly, cellular molecular complex subunit organization, and macromolecular complex assembly.

The host–virus networks are constructed in order to understand the interaction and to find the therapeutic targets. These findings of the current research are also supported by recents reported studies, where the epigenetic modification of virus affects the normal chromatin dynamics [25]. Kuznetsova et al. reported that 53 active compounds blocks HDT Ebola virus-like particle (VLP) through drug repurposing and classified as microtubule inhibitors, anticancer/antibiotics, estrogen receptor modulators, antihistamines, antipsychotics, and pump/channel antagonists [24]. Also, it is understood that the interplay between virus-chromatin interactions paves a way to understand the role of chromatin in viral infection [23] and Madrid et al. [27] assembled and screened the efficacy of 1012 FDA approved drugs for various bacterial and viral pathogens by in vitro cell culture assays.

Microtubules play a vital role as a part of the infection process. Ebola matrix protein VP40 co-localized with microtubules and enhances the tubulin polymerization without any cellular mediators. Microtubules may play an important role in Ebolavirus life cycle and potentially act as a novel therapeutic target [35]. It also participates in early and late events of assembly, budding, shuttling intermediate viral products, important transcription regulator of several negative-strand RNA viruses [35, 36, 41]. Microtubules inhibitors are most potent to inhibit the entry of ebola, but with the wild type of viruses, it is not confirmed with drug activity [24]. Structural bioinformatics analysis of the interactions may further lead to identify effective drugs. Cellular protein tubulin beta chain has a higher probability of interaction with VP24 [14]. Ebola GP protein has a receptor binding region (RBR) which helps the virus to enter into the host and consistently its transport to the cell surface which is controlled by microtubules [12].

The functional analysis of host–virus–drug interaction is necessary to find the potential host-oriented anti-viral drugs. As host-oriented drug target identification has many benefits than the virus due to its lower mutation rate in human than viral genes and also host targets are better to solve the problem of drug resistance than viruses [44].

In summary, the conventional drug discovery process is much costlier, lengthy and time-consuming for approval where drug repurposing is an alternative method to identify the new action of old therapeutics. In this work, the experimentally reported Ebola and human interacting genes are collected followed by the enrichment analysis to understand host–virus interactions. Then, the host–virus–drug network is generated to predict the insights into the development of new antiviral.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The Centre for Bioinformatics, Pondicherry University provided infrastructure and facility to carry out the work. Mathavan Muthaiyan acknowledges a Junior Research Fellowship from Rajiv Gandhi National Fellowship (RGNF). Leimarembi Devi Naorem acknowledges a Senior Research Fellowship from the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Hackl H, Charoentong P, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, et al. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-into decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bixler SL, Duplantier AJ, Bavari S. Discovering drugs for the treatment of Ebola virus. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2017;9:299–317. doi: 10.1007/s40506-017-0130-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley JH, Harrison A, Corey A, Gentry N, Gregg RK. Ebola virus secreted glycoprotein decreases the anti-viral immunity of macrophages in early inflammatory responses. Cell Immunol. 2018;324:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calderone A, Licata L, Cesareni G. VirusMentha: a new resource for virus–host protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D588–D592. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatr-aryamontri A, Ceol A, Palazzi LM, Nardelli G, Schneider MV, Castagnoli L, et al. MINT: the molecular INTeraction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2006–2008. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatr-Aryamontri A, Oughtred R, Boucher L, Rust J, Chang C, Kolas NK, et al. The BioGRID interaction database: 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D369–D379. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng AC, Kelly H. Are we prepared for Ebola and other viral haemorrhagic fevers? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38:403–404. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotto KC, Wagner AH, Feng Y, Kiwala S, Coffman C, Spies G, et al. DGIdb 3.0: a redesign and expansion of the drug–gene interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:1068–1073. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dennis G, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane H, et al. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-9-r60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimasi JA, Hansen RW, Grabowski HG. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. J Health Econ. 2003;22:151–185. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douer D. Efficacy and safety of vincristine sulfate liposome injection in the treatment of adult acute lymphocytic leukemia. Oncologist. 2016;21:840–847. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dube D, Schornberg KL, Shoemaker CJ, Delos SE, Stantchev TS, Clouse KA, et al. Cell adhesion-dependent membrane trafficking of a binding partner for the ebolavirus glycoprotein is a determinant of viral entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:16637–16642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008509107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyary HO, Rahman HS, Othman HH, Abdullah R, Chartrand MS. Advancements in the therapy of Ebola virus disease. Pediatr Infect Dis Open Access. 2016;01:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.García-Dorival I, Wu W, Dowall S, Armstrong S, Touzelet O, Wastling J, et al. Elucidation of the Ebola virus VP24 cellular interactome and disruption of virus biology through targeted inhibition of host–cell protein function. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:5120–5135. doi: 10.1021/pr500556d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goel S, Mita AC, Mita M, Rowinsky EK, Chu QS, Wong N, et al. Cancer therapy: clinical a phase i study of eribulin mesylate (E7389), a mechanistically novel inhibitor of microtubule dynamics, in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4207–4213. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guirimand T, Delmotte S, Navratil V. VirHostNet 2.0: surfing on the web of virus/host molecular interactions data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D583–D587. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hermjakob H. IntAct: an open source molecular interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D452–D455. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamal A, Suresh P, Ramaiah MJ, Mallareddy A, Ashwini B, Raju P, et al. Bioorganic and medicinal chemistry synthesis and biological evaluation of 4β-acrylamidopodophyllotoxin congeners as DNA damaging agents. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:4589–4600. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:109–114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufmann SHE, Dorhoi A, Hotchkiss RS, Bartenschlager R. Host-directed therapies for bacterial and viral infections. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:35–56. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerrien S, Aranda B, Breuza L, Bridge A, Broackes-Carter F, Chen C, et al. The IntAct molecular interaction database in 2012. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D841–D846. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khanderao A, Sankunny J, Karuppayil M. Molecular docking studies on thirteen fluoroquinolines with human topoisomerase II a and b. In Silico Pharmacol. 2017;5:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40203-017-0021-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knipe DM, Lieberman PM, Jung JU, Mcbride AA, Morris KV, Ott M, et al. Snapshots: chromatin control of viral infection. Virology. 2014;435:141–156. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kouznetsova J, Sun W, Martínez-Romero C, Tawa G, Shinn P, Chen CZ, Schimmer A, Sanderson P, McKew JC, Zheng W, García-Sastre A. Identification of 53 compounds that block Ebola virus-like particle entry via a repurposing screen of approved drugs. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2014;3:1–6. doi: 10.1038/emi.2014.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lieberman PM. Chromatin organization and virus gene expression. J Cell Physiol. 2008;216:295–302. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu L, Wei J, Ruan J. Pathway enrichment analysis with networks. Genes (Basel) 2017;8:1–12. doi: 10.3390/genes8100246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madrid PB, Chopra S, Manger ID, Gilfillan L, Keepers TR, Shurtleff AC, et al. A systematic screen of FDA-approved drugs for inhibitors of biological threat agents. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahanty S, Bray M. Reviews pathogenesis of filoviral haemorrhagic fevers. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:487–498. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01103-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohapatra S, Saha A, Mondal P, Jana B, Ghosh S. Synergistic anticancer effect of peptide-docetaxel nanoassembly targeted to tubulin: toward development of dual warhead containing nanomedicine. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6:1600718. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201600718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moss ML, Palmer RE, Kuzmih P, Dunlap BE, Henzelq W, Kofron JL, et al. Identification of actin and HSP 70 as cyclosporin A binding proteins assays. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22054–22059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murayama M, Tsujimoto K, Uozaki M, Katsuyama Y, Yamasaki H, Utsunomiya H, et al. Effect of caffeine on the multiplication of DNA and RNA viruses. Med Rep. 2008;68:251–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newcomb WW, Brown JC. Internal catalase protects herpes simplex virus from inactivation by hydrogen peroxide. J Virol. 2012;86:11931–11934. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01349-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oliveros JC. VENNY. An interactive tool for comparing lists with Venn Diagrams. 2007. http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html.

- 34.Peri S. Human protein reference database as a discovery resource for proteomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;32:D497–D501. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruthel G, Demmin GL, Kallstrom G, Javid MP, Badie SS, Will AB, et al. Association of Ebola virus matrix protein VP40 with microtubules. J Virol. 2005;79:4709–4719. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.4709-4719.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanderson CM, Hollinshead M, Smith GL. The vaccinia virus A27L protein is needed for the microtubule-dependent transport of intracellular mature virus particles. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:47–58. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt N, Gans EH. Tretinoin: a review of its anti-inflammatory properties in the treatment of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:22–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuler J. A systematic review of computational drug discovery, development, and repurposing for Ebola virus disease treatment. Molecules. 2017;22:1777. doi: 10.3390/molecules22101777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shannon P, Markiel A, Owen O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sordet O, Goldman A, Pommier Y. Topoisomerase II and tubulin inhibitors both induce the formation of apoptotic topoisomerase I cleavage complexes. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:3139–3145. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suryanarayana K, Baczko K, Volker M, Wagner RR. Transcription inhibition and other properties of matrix proteins expressed by M genes cloned from measles viruses and diseased human brain tissue. J Virol. 1994;68:1532–1543. doi: 10.1128/JVI.68.3.1532-1543.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v10: protein–protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D447–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takada A, Kawaoka Y. The pathogenesis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:506–511. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tavassoli A. Targeting the protein–protein interactions of the HIV lifecycle. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:1337–1346. doi: 10.1039/C0CS00092B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Timmins J, Scianimanico S, Schoehn G, Weissenhorn W. Vesicular release of Ebola virus matrix protein VP40. Virology. 2001;283:1–6. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uesaka T, Shono T, Kuga D, Suzuki SO, Niiro H, Miyamoto K, et al. Enhanced expression of DNA topoisomerase II genes in human medulloblastoma and its possible association with etoposide sensitivity. J Neurooncol. 2007;84:119–129. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9360-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang C, Ravelli RBG, Roussi F, Steinmetz MO, Knossow M, Curmi PA. Structural basis for the regulation of tubulin by vinblastine. Nat Lett. 2005;435:519–522. doi: 10.1038/nature03566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weaver BA. How Taxol/paclitaxel kills cancer cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:2677–2681. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e14-04-0916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao Y. Towards structural based drug development for Ebola virus disease. J Chem Biol Ther. 2016;1:1–3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.