Abstract

Neboviruses and genogroup III noroviruses (NoVsGIII) are causative agents of calf diarrhea. The purpose of this study was to investigate the presence of neboviruses and noroviruses in cattle in China. Twenty-eight diarrhea fecal samples collected from 5 different farms were analyzed by RT-PCR. The results showed that 3 nebovirus positive samples were detected on 2 farms, with two strains being related to Bo/DijonA216/06/FR strain and the other one clustering with NB-like strains. Meanwhile, 3 norovirus positive samples were detected on 3 farms, all of which belonged to genotype 1. Our results confirmed the presence of neboviruses and NoVsGIII in China for the first time, and supported the presence of a novel “DijonA216-like” nebovirus genotype.

Keywords: Nebovirus, Norovirus, RT-PCR, Calf, China

Caliciviruses are small non-enveloped viruses with a positive-stranded RNA genome, which widely infect humans and other animals, causing gastrointestinal disorders and even fatal bleeding [1]. The Caliciviridae family includes the genera Vesivirus, Sapovirus, Lagovirus, Norovirus and Nebovirus. Neboviruses and genogroup III noroviruses (NoVsGIII) have been associated with enteric disease in calves [2, 3].

Nebovirus was officially classified as a new genus in 2010 [4]. Experimental infection with neboviruses can cause intestinal lesions and diarrhea 2 to 5 days after infection [2, 5, 6]. Initially, the genotypes Nebraska (NB) and Newbury-1 (NA1) have been suggested for sub-classifying neboviruses [12]. Recently, in 2011, the strain Bo/DijonA216/06/FR was detected in France, which could represent a novel genotype [7]. Until now, NB-like strains have been found in the United States, the United Kingdom, France, South Korea, Italy, Tunisia and Turkey [2, 7–12], while NA1-like strains have been found in the United Kingdom and Brazil [12, 13]. “DijonA216-like” has only been detected in France, and this genotype has only one sequence in GenBank.

Bovine noroviruses, belonging to genogroup III (NoVsGIII), are divided into two distinct genotypes, genotype 1 and genotype 2. Experimental infection with NoVsGIII causes calf diarrhea of a long duration, with the symptoms of genotype 1 being more severe than genotype 2 [3, 14]. Previous reports have shown that NoVsGIII has been detected in 17 countries with various prevalence rates [7, 8, 10, 15–28]. Indeed, high prevalence rates now indicate that NoVsGIII have become the major pathogen causing calf diarrhea in the Midwestern United States [19, 29].

The purpose of this study was to investigate the presence of neboviruses and noroviruses in cattle in China. From September 2016 to April 2017, twenty-eight diarrhea fecal samples were collected from 5 different farms in the Hebei and Sichuan Provinces, China. The ages of the calves ranged from 3 to 4 months. The fecal specimens were shipped on ice and stored at -80 °C.

The clinical fecal samples were fully resuspended in PBS (1:5) and total RNA from 300 μL of the fecal suspension was extracted using TrizolTM Reagent (TaKaRa, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using the PrimescriptTM reverse transcription kit (TaKaRa, China) and stored at -20 °C.

Primers targeting the nebovirus genome were designed (using Primer 5.0 software) based on virus metagenomics sequencing data [GenBank accession number SUB2762873] obtained from a previously acquired calf diarrhea sample, which included nebovirus, as well as the nebovirus nucleotide sequences in GenBank. The primer sequences were as follows; F: 5’-CAGCCCGTCTGGGTGAAT-3’; R: 5’-CCAGCGTTAGCGTTCCAG-3’. The amplified fragment was 524 bp, composing part of the RdRp (1 bp to 297 bp) and the capsid gene (298 bp to 524 bp). For NoVsGIII, primer sets CBECU-F/CBECU-R were used to amplify 532 bp of the RdRp ORF of the virus according to previous reports [30].

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed with Premix Taq™ (TaKaRa, China), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The PCR amplification products were gel-purified using a gel extraction kit (OMEGA, USA) and then cloned into the pMD19-T vector and transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells. The recombinant plasmids were extracted using a plasmid extraction kit (OMEGA, USA) and sent to Sangon Biotech (China, Chengdu) for sequencing.

Among the 28 fecal samples from cattle, 3 diarrhea samples from 2 farms were positive for nebovirus (accession numbers in GenBank: MF182624-MF182626 for strains LZB-1, YLA-1 and YLA-2 respectively). Meanwhile, 3 diarrhea samples from 3 farms were positive for NoVsGIII (accession numbers in GenBank: MF182621-MF182623 for strains HBC-1, SCD-1 and YLA-3, respectively). YLA-1, YLA-2 and YLA-3 were all discovered at the same farm, which indicated there was co-circulation of nebovirus and norovirus at this farm.

Diarrhea is one of the commonest diseases of calves in China, which leads to serious economic losses. Bovine rotavirus, bovine coronavirus and bovine viral diarrhea virus have been identified as major diarrhea causing viruses. However, there is little attention to neboviruses and noroviruses in terms of calf diarrhea. Although the number of samples was limited, the study confirmed for the first time the presence of neboviruses and NoVsGIII in China, which has significant implications for the diagnosis and control of calf diarrhea in China.

The partial nucleotide sequences of the neboviruses and noroviruses identified in this study were analyzed using the MegAlign software to calculate sequence identities to other strains in GenBank. MEGA 6.0 was used to perform multiple sequence alignment and subsequently to build a neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree with bootstrap support.

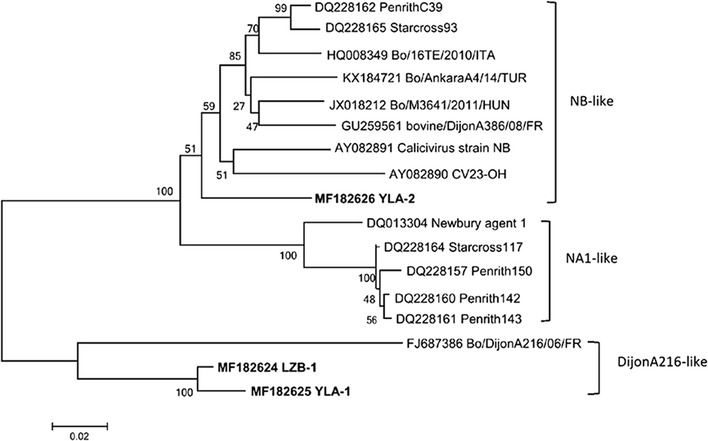

The 524 bp of the 3 neboviruses sequences in this study shared 88.4% to 97.7% nt identity to each other and 77.1% to 92.9% nt identity with neboviruses sequences in GenBank. The YLA-1 and LZB-1 strains shared 84.7% nt identity with Bo/DijonA216/06/FR, 81.5-85.1% nt identity with NB-like strains and 77.9-80.0% nt identity with NA1-like strains. The YLA-2 strain shared 90.1-92.9% nt identity with NB-like strains, 87.4-88.4% nt identity with NA1-like strains and 77.1% nt identity with Bo/DijonA216/06/FR. Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that two of the three strains clustered with Bo/DijonA216/06/FR isolated in France (Fig. 1), which supported the presence of a novel “DijonA216-like” genotype in China. The other strain clustered with the NB-like strains.

Fig. 1.

Neighbour-joining phylogenetic analysis of neboviruses based on the cloned 524 bp fragments identified in this study. The numbers at the nodes represent the percentage branching following 1000 bootstrap replicates. Bars indicate the number of inferred substitutions per site. The nebovirus sequences determined in this study are show in bold

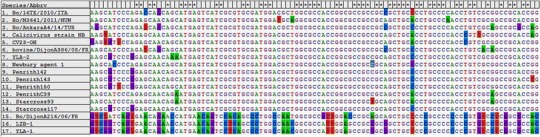

An alignment of the cloned 524 bp fragment amplified from neboviruses showed that YLA-1 and LZB-1 had similar nucleotide organization to Bo/Dijon216/06/FR. Interestingly, this genotype of nebovirus shared regular nucleotide mutations within the partial capsid sequence (312 bp to 412 bp within the cloned sequences) when compared with the other two genotypes of nebovirus (Fig. 2). This data further supports the results whereby YLA-1 and LZB-1 clustered phylogenetically with Bo/DijonA216/06/FR .

Fig. 2.

The nebovirus sequence alignment generated by MEGA 6.0/. The sequences shown represent 312 bp to 412 bp of the cloned sequences

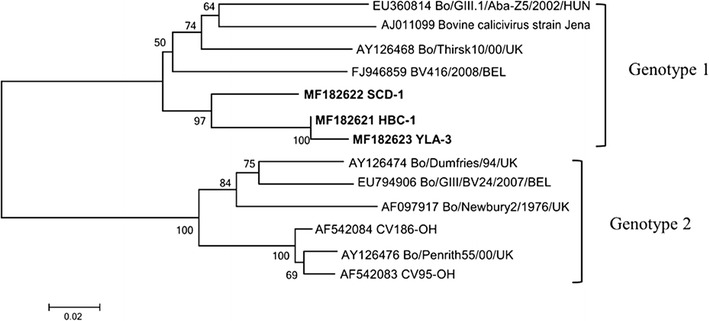

Analysis of the 532 bp fragment representing the NoVsGIII isolates indicated that the 3 NoVsGIII sequences shared 91.7% to 98.5% nt identity with each other and 75.3% to 89.0% nt identity with NoVsGIII sequences in GenBank. The 3 NoVsGIII strains in this study shared 84.8-88.9% nt identity with genotype 1 and 76.1%-80.8% nt identity with genotype 2. Phylogenetic analysis confirmed that all 3 strains were genotype 1. Interestingly, the 3 sequences clustered into an independent branch (Fig. 3). Previous studies have suggested that genotype 2 is the main genotype worldwide, and genotype 1 is a minor circulating genotype [7, 10, 27]. It is therefore valuable to further investigate the prevalence and genotypes of NoVsGIII in China.

Fig. 3.

Neighbour-joining phylogenetic analysis of NoVsGIII based on a partial region of the RdRp polymerase ORF (532 bp). The numbers at the nodes represent the percentage branching following 1000 bootstrap replicates. Bars indicate the number of inferred substitutions per site. The NoVsGIII sequences determined in this study are show in bold

In conclusion, this study has confirmed for the first time the presence of neboviruses and NoVsGIII in China, which will have significant implications for the diagnosis and control of calf diarrhea in China. The two nebovirus strains in this study clustered with Bo/DijonA216/06/FR, which supports the presence of a novel “DijonA216-like” nebovirus genotype in China.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the 13th Five-Year Plan National Science and Technology Support Program (Grant number 2016YFD0500907), as well as the Innovative Research Project of Graduate Students in Southwest University for Nationalities (Grant number CX2017SZ056).

Compliance with ethical standards

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors and is in compliance with ethical standards for research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Van Der Poel WH, Vinje J, van Der Heide R, Herrera MI, Vivo A, et al. Norwalk-like calicivirus genes in farm animals. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6(1):36–41. doi: 10.3201/eid0601.000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smiley JR, Chang KO, Hayes J, Vinjé J, Saif LJ. Characterization of an enteropathogenic bovine calicivirus representing a potentially new calicivirus genus. J Virol. 2002;76(20):10089–10098. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10089-10098.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otto PH, Clarke IN, Lambden PR, Salim O, Reetz J, et al. Infection of calves with bovine norovirus GIII.1 strain jena virus: an experimental model to study the pathogenesis of norovirus infection. J Virol. 2011;85(22):12013–12021. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05342-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carstens EB. Ratification vote on taxonomic proposals to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2009) Arch Virol. 2010;155:133–146. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0547-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridger JC, Hall GA, Brown JF. Characterization of a calici-like virus (Newbury agent) found in association with astrovirus in bovine diarrhea. Infect Immun. 1984;43(1):133–138. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.1.133-138.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woode GN, Bridger JC. Isolation of small viruses resembling astroviruses and caliciviruses from acute enteritis of calves. J Med Microbiol. 1978;11(4):441–452. doi: 10.1099/00222615-11-4-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplon J, Guenau E, Asdrubal P, Pothier P, Ambert-Balay K. Possible novel nebovirus genotype in cattle, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(6):1120–1123. doi: 10.3201/eid/1706.100038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park SI, Jeong C, Park SJ, Kim HH, Jeong YJ, et al. Molecular detection and characterization of unclassified bovine enteric caliciviruses in South Korea. Vet Microbiol. 2008;130(3–4):371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di MB, Di PF, Martella V, Ceci C, Marsilio F. Evidence for recombination in neboviruses. Vet Microbiol. 2011;153(3–4):367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassine-Zaafrane M, Kaplon J, Sdiri-Loulizi K, Aouni Z, Pothier P, et al. Molecular prevalence of bovine noroviruses and neboviruses detected in central-eastern Tunisia. Arch Virol. 2012;157(8):1599–1604. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alkan F, Karayel I, Catella C, Bodnar L, Lanave G, et al. Identification of a bovine enteric calicivirus, Kirklareli virus, distantly related to neboviruses, in calves with enteritis in Turkey. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(11):3614–3617. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01736-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliver SL, Asobayire E, Dastjerdi AM, Bridger JC. Genomic characterization of the unclassified bovine enteric virus newbury agent-1 (Newbury1) endorses a new genus in the family Caliciviridae. Virology. 2006;350(1):240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Candido M, Alencar AL, Almeida-Queiroz SR, Buzinaro MG, Munin FS, et al. First detection and molecular characterization of Nebovirus in Brazil. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(9):1876–1878. doi: 10.1017/S0950268816000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung K, Scheuer KA, Zhang Z, Wang Q, Saif LJ. Pathogenesis of GIII.2 bovine Norovirus, CV186-OH/00/US strain in gnotobiotic calves. Vet Microbiol. 2014;168(1):202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohamed FF, Mansour SMG, El-Araby IE, Mor SK, Goyal SM. Molecular detection of enteric viruses from diarrheic calves in Egypt. Arch Virol. 2017;162(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-3088-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng Y, Batten CA, Liu BL, Lambden PR, Elschner M, et al. Studies of epidemiology and seroprevalence of bovine noroviruses in Germany. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(6):2300–2305. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2300-2305.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattison K, Shukla A, Cook A, Pollari F, Friendship R, et al. Human noroviruses in Swine and Cattle. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(8):1184–1188. doi: 10.3201/eid1308.070005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poel WH, Heide R, Verschoor F, Gelderblom H, Vinjé J, et al. Epidemiology of norwalk-like virus infections in cattle in The Netherlands. Vet Microbiol. 2003;92(4):297. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00421-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wise AG, Monroe SS, Hanson LE, Grooms DL, Sockett D, et al. Molecular characterization of noroviruses detected in diarrheic stools of Michigan and Wisconsin dairy calves: circulation of two distinct subgroups. Virus Res. 2004;100(2):165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milnes AS, Binns SH, Oliver SL, Bridger JC. Retrospective study of noroviruses in samples of diarrhoea from cattle, using the Veterinary Laboratories Agency’s Farmfile database. Vet Rec. 2007;160(10):326–330. doi: 10.1136/vr.160.10.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alcala AC, Hidalgo MA, Obando C, Vizzi E, Liprandi F, et al. Molecular identification of bovine enteric calciviruses in Venezuela. Acta Cientifica Venezolana. 2003;54(2):148–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf S, Williamson W, Hewitt J, Rivera-Aban M, Lin S, et al. Sensitive multiplex real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay for the detection of human and animal noroviruses in clinical and environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(17):5464–5470. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00572-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mauroy A, Scipioni A, Mathijs E, Saegerman C, Mast J, et al. Epidemiological study of bovine norovirus infection by RT-PCR and a VLP-based antibody ELISA. Vet Microbiol. 2009;137(3):243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reuter G, Pankovics P, Egyed L. Detection of genotype 1 and 2 bovine noroviruses in Hungary. Vet Rec. 2009;165(18):537–538. doi: 10.1136/vr.165.18.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mijovski JZ, Poljsak-prijatelj M, Steyer A, Barlic-Maganja D, Koren S. Detection and molecular characterisation of noroviruses and sapoviruses in asymptomatic swine and cattle in Slovenian farms. Infect Genet Evol. 2010;10(3):413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yilmaz H, Turan N, Altan E, Bostan K, Yilmaz A, et al. First report on the phylogeny of bovine norovirus in Turkey. Arch Virol. 2011;156(1):143–147. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0833-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di BI, Ponterio E, Monini M, Ruggeri FM. A pilot survey of bovine norovirus in northern Italy. Vet Rec. 2011;169(3):73. doi: 10.1136/vr.d2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferragut F, Vega CG, Mauroy A, Conceicao-Neto N, Zeller M, et al. Molecular detection of bovine Noroviruses in Argentinean dairy calves: Circulation of a tentative new genotype. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;40:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho YI, Han JI, Wang C, Cooper V, Schwartz K, et al. Case–control study of microbiological etiology associated with calf diarrhea. Vet Microbiol. 2013;166(3–4):375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smiley JR, Hoet AE, Travén M, Tsunemitsu H, Saif LJ. Reverse transcription-PCR assays for detection of bovine enteric caliciviruses (BEC) and analysis of the genetic relationships among BEC and human caliciviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(7):3089–3099. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3089-3099.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]