Abstract

Infectious diseases and cancers are some of the commonest causes of deaths throughout the world. The previous two decades have witnessed a combined endeavor across various biological sciences to address this issue in novel ways. The advent of recombinant DNA technologies has provided the tools for producing recombinant proteins that can be used as therapeutic agents. A number of expression systems have been developed for the production of pharmaceutical products. Recently, advances have been made using plants as bioreactors to produce therapeutic proteins directed against infectious diseases and cancers. This review highlights the recent progress in therapeutic protein expression in plants (stable and transient), the factors affecting heterologous protein expression, vector systems and recent developments in existing technologies and steps towards the industrial production of plant-made vaccines, antibodies, and biopharmaceuticals.

Keywords: Antibodies, Bacterial cells, Biopharmaceuticals, Mammalian cells, Protein expression, Vaccines

Introduction

The constant threat of disease-causing microorganisms is a serious concern and has evoked a paradigm shift in the pharmaceutical and biotechnological industries, prompting them to exploit the heterologous expression of compounds in living systems. Plants occupy an important position in the current short list of biofactories and promise rapid developments in the field of plant-derived biopharmaceutical agents and edible vaccines. The simple and convenient approach involved, the high yields of proteins, the lower production and storage cost, the elimination of pathogen contamination, the little processing required, and the secure delivery of oral vaccines are the predominant benefits that have boosted the use of this system in recent years. However, certain limitations often reduce the expression of target genes in plant systems, encouraging researchers to comprehensively investigate heterologous protein expression in plants and to develop novel strategies to ensure the sufficient expression of biopharmaceutical peptides that can induce immune responses.

Background

The advent of recombinant DNA technology has widened the research arena for biologists. The manipulation of Escherichia coli provided the first expression system (Itakura et al. 1977) for therapeutic proteins, pioneering the production of recombinant proteins. The subsequent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval (Human insulin receives FDA approval 1982), of an E. coli-based insulin (Goeddel et al. 1979) confirmed the utility of recombinant therapeutic protein production. As a prokaryote, E. coli cannot accurately express complex eukaryotic protein because almost all eukaryotic proteins are modified post-translationally and require the appropriate machinery to impart the characteristic structural features that are essential for their functional integrity. Resolution of this problem has led to the development of other expression systems, including the yeast system, the Baculovirus system, the mammalian cell system, and the plant expression system. Each type of expression system has been used extensively for the production of recombinant therapeutic compounds, with varying success, because no single system is universally appropriate for all tasks. However, plant expression systems excel in the production of plant-derived edible vaccines (Goeddel et al. 1979; Mishra et al. 2008; Yang and Yang 2010) and have tremendous growth potential as the basis of the modern discipline, providing immediate cures for infectious diseases. Simultaneous expression of multigenes reviewed by (Zorrilla-Lopez et al. 2013) into plants can alter complex metabolic pathways that can be used to produce compounds of pharmaceutics.

The transfer of foreign DNA from diverse organisms and its integration into a host genome form the backbone of recombinant DNA technology. However, the expression of a foreign gene in a host plant cell is dependent on the cumulative effects of several elements essential for cell transformation (coding sequence, promoter region, transcript termination, etc.), the plant cell pH, the efficiency and accuracy of the transcriptional and translational machinery, plant cell biochemistry, the availability of the amino acids required for the recombinant protein, the interaction between and storage of the expressed proteins in the plant cellular environment, and many other predictable and unknown factors. Moreover, various modern plant biotechnological strategies are evolving for the targeted optimization of recombinant protein expression in host cells (including plant cells) using novel strategies (Fahad et al. 2014).

The expression of biopharmaceutical proteins in plants is based on both stable and transient expression systems. The stable transfer of a foreign gene is targeted to either the nucleus or chloroplast. The stable nuclear and plastid expression in recombinant plants (Horsch et al. 1985; Verma and Daniell 2007) and pharmaceutical proteins dates back to 1989, when transgenic-tobacco-derived immunoglobulins were efficiently assembled as functional antibodies in plants (Hiatt et al. 1989). Several studies were subsequently conducted that confirmed the use of plants to produce edible vaccines by applying this technology to rice, (Nochi et al. 2007; Shin et al. 2013; Tokuhara et al. 2013; Yuki et al. 2013), carrot (Rosales-Mendoza et al. 2008) and soybean (Moravec et al. 2007). The delivery of the gene of interest to the plant cell nucleus is achieved either with microprojectile bombardment (Lindbo 2007a) or, preferably, with Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (Nochi et al. 2007) or mediation by another non-Agrobacterium species (Broothaerts et al. 2005). Horizontal gene transfer and the constant expression of recombinant proteins are prominent features of stable nuclear transformation. Although this is a classical strategy, nuclear transformation is associated with several problems, including gene silencing (Chebolu and Daniell 2009), haphazard gene integration resulting in position effects of the transgene (Gorantala et al. 2011), low yields (<1 % of the total soluble protein), and a high risk of transgene contamination, which strongly discourage the commercialization of the strategy for large-scale plant-derived pharmaceutical production.

Stable plastid transformation has become an alternative strategy to nuclear transformation for the commercial production of plant-based and edible pharmaceutical compounds. Chloroplasts are characteristic plant cell organelles that are maternally inherited in most plant species (Hagemann 2004), with tiny DNA genomes of 120–150 kb (Bendich 1987). Each mesophyll plant cell contains approx. 100 chloroplasts, with 100 copies of the plastome in each chloroplast. This prompted the idea of expressing multiple transgenes with a single transgenesis process. This also extends the production potential of the transgenic plant (Maliga 2004), a crucial step in the commercialization.

An interesting feature of chloroplast DNA is that it contradicts the principles of Mendelian inheritance because it is maternally inherited in most plants, thus prohibiting gene contamination (Kittiwongwattana et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2009; Lossl and Waheed 2011). However, the pollen of transplastomic plants may occasionally be responsible for transgene contamination (Daniell et al. 1998; Svab and Maliga 2007). Therefore, rigorous selection of the parental lines is advocated by researchers to avoid this exceptional possibility (Svab and Maliga 2007; Ruf et al. 2007). Furthermore, the presence of a single promoter is sufficient to express multiple genes because most chloroplast genes are arranged in operons and are transcribed as polycistronic mRNA (Quesada-Vargas et al. 2005). In short, the potential for polycistronic expression, with minimal chance of horizontal or vertical gene transfer through pollen transmission, the enormous replication potential, and very high yields of proteins in transplastomic plants are the key benefits of plastid transformation over nuclear transformation.

The transient expression of foreign genes in plants does not require the transgene to be integrated into the host genome nor does it follow the molecular central dogma for expression in plants. However, it provides an opportunity to express recombinant proteins within a very short period of time (Verma and Daniell 2007), another novel attribute that has stimulated the development of plants as biofactories for pharmaceutical production. Therefore, the rapid commercialization of plant-derived vaccines, antigens, antibodies, and therapeutic drugs is likely in the near future based on the distinct merits of this transient expression system, including its rapid expression of target genes, the simplicity of the system, the fact that it does not require sophisticated laboratory equipment or techniques, and the possibility of improving expression levels with novel optimization techniques (Komarova et al. 2010).

The first in vitro and in vivo expression of viral RNAs (Marillonnet et al. 2004) were milestones in this field and encouraged researchers to explore the utility of plant viral vectors for producing recombinant proteins in crop plants. Plant viral vectors do not integrate into the host genome and are characterized by their tremendous expression potential because they are rapidly transmitted from one plant cell to another (Tiwari et al. 2009). The expression of an antigen epitope (Haynes et al. 1986) was demonstrated using the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV)-coat protein in a plant system. A short comparison of the technologies used in the production of recombinant proteins as biopharmaceutical agents is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of stable (nuclear, chloroplast) and transient expression systems

| Type of transformation | Host plant/location | Vector/promoter | Recombinant protein | Expression level | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable expression | |||||

| Nuclear transformation | Rice endosperm | Tapur promoter | Human lysozyme | 41.6 µg/grain | Hennegan et al. (2005) |

| Tobacco cell compartments | pTRA | Haemagglutinin surface protein | 640–1,440 mg/kg | Mortimer et al. (2012) | |

| Rice Seeds | CaMV-35S | Cholera toxin B (CTB) | 0.3 % | Gunn et al. (2012) | |

| Tobacco | CaMV-35S | Heat labile enterotoxin B | 1.6 % | Larsen and Curtis (2012) | |

| Soybean | ubi3 | Heat labile enterotoxin B | >2.0 % | Moravec et al. (2007) | |

| Carrot | CaMV-35S | Heat labile enterotoxin B | 3.0 µg/g | Rosales-Mendoza et al. (2008) | |

| Chloroplast transformation | Tobacco leaves | rice psbA promoter-E2 | pE2 polypeptide | pE2 polypeptide | Zhou et al. (2006) |

| Tobacco | NEP promoter | HPV 16-L1 capsomere | 1.5 % | Waheed et al. (2012) | |

| Tobacco | psbA promoter | HCV core Protein | 0.1 % TLP | Hiroi and Takaiwa (2006) | |

| Tobacco | prrn promoter | C4V3 protein | 25 µg/g FW | Tregoning et al. (2005) | |

| Sugarbeet | prrn promoter | GFP | NA | Haq et al. (1995) | |

| Brassica | 16S rRNA promoter | Anti-spectinomycin | NA | Turpen et al. (1995) | |

| Transient expression | |||||

| Epitope presentation | Tobacco | CMVCP–F/HN | CMV VLPs | 1–2 mg/ml | (Rigano et al. 2013) |

| Tobacco | Potato virus X | HPV-16 L2 | 170 mg/kg | McCormick et al. (2008) | |

| Tobacco | Potato virus X Alt. mosaic virus | Influenza virus M2E | 1–3 mg/g | Mason et al. (1998) | |

| Agroinfilteration | Tobacco | Binary vector | GFP/HFBI | 38 % | Itakura et al. (1977) |

| Tobacco | Ptrac | HIV-1 pr55GAG | 0.3 % | Pillai and Panchagnula (2001) | |

| Tobacco | Binary vector | HIV monoclonal antibody 2G12 | NA | Mishra et al. (2008) | |

| Tomato | Pepino mosaic virus PepMV | FMDV 2A catalytic peptide | 0.2–0.4 g/kg | Boothe et al. (2010) | |

| magniCON | Tobacco | PVX amplicon vector | COPV L1-protein | NA | Azhakanandam et al. (2007) |

| Tobacco | TRBO | GFP, HA peptide | 3.3–5.5 g/kg | Lindbo (2007a) | |

| Tobacco | TMV vector | GFP | NA | Lindbo (2007b) | |

| Tobacco | pTBSV | HBc (VLPs), GFP | 0.8 mg/g FW | Huang et al. (2009) | |

| Tobacco | TMV-Gate vector | GFP, GUS | 2.5–4.7 mg/g | Kagale et al. (2012) | |

| Suspension cell culture | Tobacco | CaMV-35S | Active dust mite allergens | NA | Lindbo (2007b) |

| Tobacco | CaMV-35S | GUS | 0.03–0.12 % | Broothaerts et al. (2005) | |

| Targeted specific expression | Tomato fruit | Pepino mosaic virus PepMV | FMDV 2A catalytic peptide | 0.2–0.4 g/kg | Sempere et al. (2011) |

| Rice seeds | CaMV-35S | Cholera toxin B (CTB) | 0.3 % | Gunn et al. (2012) | |

| Rice endosperm | Tapur promoter | Human lysozyme | 41.6 µg/grain | Hennegan et al. (2005) | |

| Virus induced gene silencing (VIGS) | Soyabean | Apple latent spherical Virus (ALSV) vector | – | Transmission of silencing (20–30 %) | Yamagishi and Yoshikawa (2009), Sasaki et al. (2011) |

| Wheat spike | Barley stripe mosaic virus (BSMV) vector | NA | NA | Ma et al. (2012a, b) | |

| Viral like particles (VLPs) | Tobacco | Binary vector pPSP19 | Hepatitis B core antigen | 0.8 mg/g FW | (Huang et al. 2009) |

| Tobacco | Chimeric double CaMV-35S promoter | HA peptide | 50 mg/kg FW | D’Aoust et al. (2008), Landry et al. (2010) | |

| Codon optimization | Tobacco | pZP200 with double CaMV-35S promoter | SAG1 protein | 1.3 µg/g FW | Laguía-Becher et al. (2010) |

| 3′ and 5′ UTRs | Tobacco/cotton | CaMV-35S promoter with 28nt synthetic 5′UTR | GUS protein | 2.7–14,955.0 pmol MU/min/µg protein | Kanoria and Burma (2012) |

| Arabidopsis | CaMV-35S promoter with Fluc mRNA attached to 5′UTR | HPR (By2) | 23 mg/L | Matsui et al. (2012) | |

| Tobacco | T7 promoter with attached bacteriphage 5′UTR | Ce16a/aadA | 10 % TSP | Yang et al. (2013) | |

| Epigenetic modifications | Tobacco | Tomato leaf curl Java begmovirus vector | βC1/GFP | Silenced expression observed | Kon et al. (2007) |

| Tobacco | Binary vector (PVX and TRV vectors) | GFP | Silenced Expression observed | Buchmann et al. (2009) | |

Plant system versus other heterologous protein expression systems

Pharmaceutics proteins, such as hGAD65, NVCP, 2G12 and hIL-6, have been produced using heterologous systems, for example in bacteria, yeast, mouse embryo cells, Spodoptera frugiperda cells, baby hamster kidney cells and hybridoma clones with different level of expressions. The same recombinant proteins have been expressed and produced in photosynthetically-active organisms, such as plants and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii using different organs of plants like leaves, seeds, tubers and tape roots (Merlin et al. 2014). Plants maintain a strong position among the heterologous protein production biofactories, with many advantages over other systems. The important benefits of using plants as biofactories include their ease of growth, their relatively low water usage, lower storage costs, requirements for only CO2 and minerals to grow, their adaptability to cell culture or agricultural production, the lack of pathogen contamination, and a highly scalable production system. Plants also post-translationally modify the expressed proteins correctly, allowing their proper functioning (Lossl and Waheed 2011). Escherichia coli is inappropriate for the expression of some antigenic proteins because it lacks the capacity for a variety of post-translational modifications and folding requirements. Yeast and insect cell lines can perform some of these essential post-translational modifications but there can be immunologically-significant differences in these modifications, which limit the usefulness of these systems as expression platforms for vaccine development (Houdebine 2009). In Table 2, the different expression systems used to produce heterologous proteins are compared and their most notable advantages and limitations specified.

Table 2.

Comparison of different systems used for the expression of heterologous proteins

| Expression system | Major advantages | Major limitations | Approved biopharmaceutics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial cell system (E. coli) | Availability in short duration and the most simplest system | Unable to perform glycosylation in recombinant proteins | ABthrax (Rader 2013) Human genome sciences ins., GSK |

| Yeast cell system | Correct folding in functional recombinant proteins, low cost of purification | Produced sialylated glycoproteins are not found fit for human consumption | Recombivax HB (Gilbert et al. 2012) MERCK KGAA |

| Baculovirus expression vector system (BEV) | Able to produce glycosylated recombinant proteins and suited for production of proteins requiring post-translational modifications | Presence of lipidic envelopes in virions and less efficient in processing of polyproteins | Flublok (Treanor et al. 2011) Protein Sciences Co. |

| Mammalian cell system | Highly adaptive and able to produce glycosylated protein with post-translational modifications | Associated with slow growth, increased fermentation cost and higher risks of viral infection | Flucelvax (Rader 2013) (Novartis) |

| Plant cell system | Rapid growth, low cost of purification, highly adaptive for producing glycosylated protein and any modification in Expression system is possible | Highly specific to plant of choice and any universal recombinant production system have not reported to date | Recombinant (Rader 2013) Glucocerebrosidase (Protalix) |

Plants as heterologous protein expression systems to fight infectious diseases and cancers

The important viral diseases that cause significant deaths or pandemics in human populations are influenza, measles, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, hepatitis E, human immunodeficiency virus acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV-AIDS), human papilloma virus (HPV) infection, and rabies, whereas considerable economic losses in animals are attributable to avian influenza, Norwalk virus, and foot and mouth disease. Cholera, tuberculosis, and diphtheria are among the bacterial diseases that cause considerable loss of life. Plants are used as expression systems to produce vaccines and other pharmaceuticals used as prophylactic and curative agents for these diseases. Some biopharmaceuticals recently produced in plants against important viral, bacterial, and protozoan diseases and cancers are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Biopharmaceutical compounds developed against infectious diseases and cancers using plants as biofactories

| Disease | Pathogen | Bio-pharma-ceutics | Promoter/vector | Expression system | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protozoan infection | ||||||

| Malaria | Plasmodium | pyMSP119 | Deconstructed TMV vector | magnICON Tobacco | Ma et al. (2012a, b) | |

| CTB-MSP1 AMA-1 | psba/rrn Promoters | Transplastomic transformation lettuce/choloroplast | Davoodi-Semiromi et al. (2010) | |||

| Bacterial diseases | ||||||

| Cholera | Vibrio cholarae | CTB | TMV vector | magnICON tobacco | Hiatt et al. (1989) | |

| LTB | CaMV-35S Codon optimized carrot | Somatic embryogenesis | Kohl et al. (2007), Mason et al. (1992) | |||

| LTB-ST | prrn promoter | Transplastomic transformation tobacco | Koya et al. (2005) | |||

| Seed-specific LTB | Soyabean glycinin promoter | Stable transformation somatic embryogenesis soyabean | Gleba et al. (2005) | |||

| CTB-MSP1 AMA-1 | Psba/rrn promoters | Transplastomic transformation lettuce/chloroplast | Laanger (2011) | |||

| Tuberculosis | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Immune-dominant antigens | Patatin promoter | Stable transformation Tobacco | (Modelska et al. 1998) | |

| CTB-ESTA6 | psbA promoter | Transplastomic transformation tobacco/lettuce | Hiroi and Takaiwa (2006) | |||

| TB vaccine protein | CaMV-35S promoter | Agroinfilteration tobacco | Tregoning et al. (2005) | |||

| Diphtheria Pertussis and tetani (DPT) | Diphtheria Pertussis and tetani (DPT) | sDPT polypeptide | CaMV-35S | Stable transformation tomato | Soria-Guerra et al. (2007, 2011) | |

| Viral diseases | ||||||

| SARS | Corana virus (human) | SARS-Cov | OCS3MAS | Stable nuclear transformation cauliflower | McCormick et al. (2008) | |

| Small pox | Variola virus (human) | Viral coat B5 | CaMV-35S | Stable nuclear transformation, collard | Pogrebnyak et al. (2006) | |

| Candidate pB5 | CaMV-35S | Magnifection, tobacco | Mason et al.(1998), Itakura et al. (1977) | |||

| Diarrhea | Rota virus gastroenteritis (Human) | RV VLPs | CaMV-35S | Stable nuclear transformation, tobacco | Yang et al. (2011) | |

| Post weaning diarrhea (PWD) | Procrine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) (Pigs) | sLTB–sCOE | HMW–GS (Bx17) | Epitope presentation rice endosperms | Lindbo (2007a) | |

| Functional recombinant FaeG | psbA promoter | Biolistic chloroplast transformation | Kolotilin et al. (2012) | |||

| Measles | Measles virus (human) | MV-H protein | CaMV-35S | Stable nuclear transformation, tobacco | Yang and Yang (2010), Verma and Daniell (2007) | |

| Rabies | Rabies virus (human) | Rabies nucleoprotein | CaMV-35S | Nuclear transformation and agroinfilteration, tomato | Hennegan et al. (2005) | |

| Influenza | H1N1 | HA1-protein | Binary vector AscI–PacI | Stable transformation tobacco | Nochi et al. (2007) | |

| H1N5 | HA1-5 (VLPs) | Alfalfa plastocyanin promoter | Agroinfilteration tobacco | Landry et al. (2010), D’Aoust et al. (2008) | ||

| H7N7 | HA7-7 | CaMV-35S | Agroinfilteration Tobacco | Kanagarajan et al. (2012) | ||

| H1N5, H1N5 | HA1-5/1 | Launch vector | magnICON Tobacco | Chichester et al. (2012), Shoji et al. (2011) | ||

| Hepatitis | HBV | S-HBsAg | CaMV-35S | Stable transformation lettuce | Pniewski et al. (2011) | |

| HCV | Chimeric CMVs | Cucumber mosaic Virus | magnICON Tobacco | Nuzzaci et al. (2007, 2009, 2010) | ||

| HEV | pE2 | Rice-psbA promoter E2 | Biolistic chloroplasted transformation tobacco | Zhou et al. (2006) | ||

| AIDS | Human immune deficiency virus HIV | C4V3 polypeptide | prrn promoter | Biolistic chloroplasted transformation tobacco | Rubio-Infante et al. (2012) | |

| HIVmAbs | CaMV35-S | Agroinfilteration Tobacco | Rosenberg et al. (2012) | |||

| Cancer | ||||||

| Cancer | Human pappilloma virus (HPV) | HPV16-L2 epitope | PVX | magnICON, tobacco | Cerovska et al. (2012) | |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | HPV16-L1mAbs | CaMV-35S | Stable transformation Tobacco | Liu et al. (2013) | ||

| HPV11-L1-NLS proteins | CaMV-35S | Stable transformation arabidopsis/tobacco | Kohl et al. (2007) | |||

| Dengue | Dengue virus (DENV) | Dengue virus tetra-epitope peptide (cE-DI/IIp) | Tobacco psbA promoter/pRL1001 | Lettuce plastid transformation | Maldaner et al. (2013) | |

Strategies to enhance transient recombinant protein expression in plants

Several plant transient expression rely on viral vector systems. In the 1990s scientists were using Agrobacterium to do transient expression in plants which does not rely on viral vectors (Kapila et al. 1997). The study of plant viruses revealed their latent ability to carry foreign genes. The discovery of the positive-sense RNA viruses, TMV, Tobacco rattle virus (TRV), and Potato virus X (PVX), facilitated their use as heterologous protein expression vectors (Hefferon 2012).

Viral vectors can be classified in different ways, according to the purpose they serve. The two main groups are (i) independent viral vectors; and (ii) minimal viral vectors. Independent viral vectors can replicate and be inoculated into plants as viral particles, multiply at the site of infection, and then move systemically as virus-encoded particles to infect maximum plant tissues. Minimal vectors, in contrast, can replicate but lack systemic movement and are modified to achieve greater protein expression. Although the discovery of plant viruses that can be used as vectors was a milestone in the production of recombinant proteins, their inability to carry large constructs hindered their development until they were optimized with much needed modifications. This limitation was addressed by the development of “magnifection” technology (Gleba et al. 2005), in which Agrobacterium is used as a systemic movement agent to deliver viral replicons in plants to produce high yields of recombinant proteins. This strategy combines the benefits of three systems: the DNA delivery capacity of Agrobacterium, the expression levels of RNA viruses, and the post-translational modifications and low production costs of plants.

Magnifection technology has many benefits, including the ease of biocontainment of the transgenes, simple scale-up, high-level expression of heterologous proteins, low cost, and versatile protein expression (single-chain antibodies, antigens, enzymes, etc.). However, it is still limited in its capacity to post-translationally modify the recombinant proteins. In particular, aberrant glycosylation patterns can make the recombinant protein nonfunctional, by affecting its immunogenicity in the case of vaccines (Gleba et al. 2005). The high expression levels of some recombinant proteins can also have a lethal effect on plants, such as the hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen (HBsAg; Gleba et al. 2005) mostly on cell expansion and cell division. The production of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies with magnifection is also difficult because it requires the manipulation of viral vectors. Recent modifications have generated magnICON (the trade name for magnifection), which has allowed the expression of many important biopharmaceutical products for important diseases, including pyMSP119 for malaria, using deconstructed viral vectors (Ma et al. 2012a, b). A few examples in which the magnICON system or its modified form has been used include the production of follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma Yusibov et al. (2011) and E. coli heat-labile enterotoxin B (LTB) (Rosales-Mendoza et al. 2008). Virus-like particle development is another important technique for high protein expression for example chimeric cucumber mosaic viruses (CMVs) for hepatitis C virus (Nuzzaci et al. 2007, 2009, 2010), while PVX is used in expressing HPV16-L2 against HPV (Cerovska et al. 2012).

The shortcomings of the magnICON system have been addressed by constructing the pEAQ vector system. pEAQ is a special type of non-replicating vector based on the Cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV). This system provides high recombinant protein expression without the fear of biocontamination or genetic drift (Peyret and Lomonossoff 2013). The new expression system, based on a deleted version of CPMV RNA-2 with a mutated 5′-untranslated region (UTR), enhances the expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP), DsRed, the HBV core antigen (HBcAg), and human anti-HIV antibody 2G12 (Sainsbury and Lomonossoff 2008; Joensuu et al. 2009).

To enhance heterologous protein production in plants, scientists have modified the strategies by using expression vectors derived from virus origins and utilizing reporter genes such as GUS and GFP while including plant-based introns for proper expression in eukaryotic cells (Canizares et al. 2005; Lico et al. 2008; Marillonnet et al. 2004, 2005). A minimal PVX vector solely with its RNA polymerase gene proved to be more effective by the expression of GUS protein yield which was 6.6-fold more than utilizing the full length PVX vector (Larsen and Curtis 2012). Post-transcriptional gene silencing was expressed when minimal PVX fragment was co-expressed with other solanaceae based viral vectors such as P19 (viral protein of tomato bushy stunt virus) and HC-Pro (viral protein of tobacco etch). Furthermore, enhanced expression of protein was attained while using major sequence from CPMV in non replicating viral vector (Canizares et al. 2005). Using hairy root as protein expression system, TRV vector exhibited higher expression of protein accumulation than PVX based vector (Larsen and Curtis 2012).

A number of strategies have been used to introduce foreign genes with CMV-based systems (CMV-based inducible vectors and CMV-based advanced replicating vectors), including the manipulation of the cloning sites, which are easy to use, and also the reassortment of genotypes is taken into consideration. The deletion of the CMV movement protein also leads to greater protein accumulation. Nicotiana benthamiana is the most suitable host for recombinant protein production using agroinfiltration and, because of its wide host range, CMV has a particular edge as the vector of choice because various plants can be used as recombinant protein factories (Hwang et al. 2012). The hydrophobin (HFB1) sequence from Trichoderma reesei fused to GFP, infiltrated on Agrobacterium, and transiently expressed in N. benthamiana, was reported to enhance the accumulation of GFP, with the concentration of the fusion protein reaching 51 % of the total soluble protein, with delayed necrosis of the infiltrated leaves (Joensuu et al. 2009).

Interestingly, the GFP–HFB1 fusion was targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where it produced large novel protein bodies. This allowed the recovery of the HFB1 fusion protein from extracts with a simple and scalable recovery process based on an aqueous two-phase system. Single-step phase separation selectively recovered 91 % of the GFP–HFB1, accounting for 10 mg/ml. Fusion with HFB1 not only increases the expression of recombinant proteins but also provides an easy method for their subsequent purification. This HFB1 fusion technology, combined with the speed and post-translational modification capacities of plants, has increased the value of transient plant-based systems (Joensuu et al. 2009). Furthermore, the lower expression of desired genes are challenged by weak promoters in plants, which can be optimized by generation of synthetic promoters as reviewed by Liu et al. (2013). The technologies described by Liu et al. (2013) can be further utilized for improving therapeutic protein expression in plants to achieve desired results.

The development of transient expression was further improved by the molecular and bioinformatic analysis of the sequences which enabled manipulation of synthetic enhancers, suppressors transcription factor binding domains and promoters. (Sainsbury and Lomonossoff 2014). These studies suggest that there is still much to be done to improve the expression of heterologous proteins in plants, most of which will involve optimizing the vector systems. It will be necessary to find regions in vector systems that do not affect their innate ability to replicate, ways to suppress transgene silencing, an interesting review by Alba et al., covers several gene silencing pathways in plants (Martínez de Alba et al. 2013) and further improvements to non-replicating viral systems that rely on hypertranslation rather than replication, such as the pEAQ vector system.

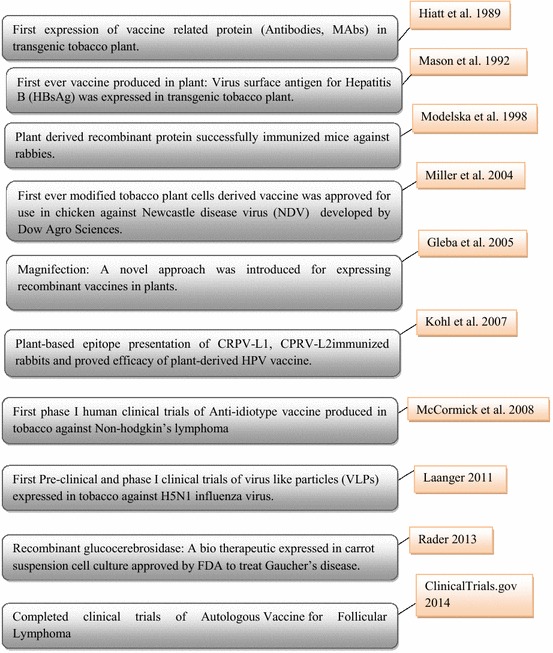

Key events in the development of the plant-derived biopharmaceutical industry

The key events in the development of plant-derived biopharmaceuticals are summarized briefly in Fig. 1. The momentum to use plants as biofactories increased when the first vaccine-related protein was expressed in transgenic tobacco plants (Hiatt et al. 1989). In the decade after this development, a number of breakthroughs occurred, in particular the expression of HbsAg in tobacco plants (Mason et al. 1992), followed by the presentation of a malarial parasite epitope (Turpen et al. 1995). Heat-labile enterotoxin B, LTB, produced in potato plants (Haq et al. 1995) as functional as that expressed in E. coli and the first human phase I clinical trial of plant-derived LTB then paved the way for the design and production of edible vaccines (Rigano et al. 2013).

Fig. 1.

Key events in the development of plant-derived biopharmaceuticals

The low-level expression of the recombinant proteins has hindered the development in this exciting field until an anthrax antigen was expressed in the chloroplast-based system and was successfully used to immunize mice (Koya et al. 2005). It was at this time that the magnifection technology was introduced to enhance heterologous protein expression (Gleba et al. 2005). This technology is an important breakthrough in increasing recombinant protein expression, with several modifications being reported subsequently. In the same year (2005), a single intranasal dose of a plant-derived vaccine produced in tobacco efficiently activated CD4+ T cells and antibodies against tetanus toxin in mice (Tregoning et al. 2005).

Progress in this field continues with reports of plant-based epitope presentation of cottontail rabbit papilloma virus CRPV-L1 and the immunization of rabbits with CPRV-L2, confirming the efficacy of a plant-derived HPV vaccine (Kohl et al. 2007). Later, the first plant-derived vaccine was approved to immunize chickens against newcastle disease virus (Miller et al. 2004), and the first phase I and II clinical trials of a plant-derived therapeutic compound from a suspension culture of carrot cells, directed against Gaucher’s disease, were undertaken (Rigano et al. 2013). In 2008, the first phase I human clinical trial of an anti-idiotype vaccine against non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was performed (McCormick et al. 2008) and, in 2010, the first preclinical and clinical trials of virus-like particles (VLPs) against H5N1 influenza and the first phase II clinical trials of caroRX (a plant-derived antibody) against dental decay were undertaken (Rigano et al. 2013). In 2011, the FDA approved a phase II human clinical trial of VLPs against H5N1 (Laanger 2011).

Conclusion

Plants can provide vaccines and other therapeutic compounds in a number of ways, including in cell or root cultures, in greenhouses, or in the field. The low productivity of heterologous proteins hindered the commercialization of plant-made biopharmaceutical products for a long time but recent developments that have increased heterologous protein expression in plants with various novel techniques, including magnifection and its optimization, have made this commercialization possible. Plant viral vectors, combined with HFB1s, provide a new way to increase recombinant protein production and to improve bioprocessing. A number of factors must be considered during recombinant protein expression, such as codon optimization, organelle- and organ-specific expression, proteases, etc., which have been extensively reviewed elsewhere. The world is threatened again by an influenza pandemic and, in such situations, plants provide a quick and reliable vaccine production system. The major hurdle remains the glycosylation pathway in plants, which is highly resistant to change, so the post-transcriptional modification of recombinant proteins for human and animals remains limited. This can be overcome by installing a novel glycosylation pathway in plants. The installation of such a novel pathway has been achieved in Arabidopsis thaliana, where a photorespiration suppression pathway was installed to increase the biomass production. Such novel technologies can be used to overcome health concerns by providing cheaper medicines to third-world countries, where the disease burden is high. Therefore, it is time for governments and commercial enterprises to allocate more funds for research into plant-made vaccines and therapeutic agents and their further commercialization.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Key Technology Program R & D of China (project no. 2012BAD04B12) and MOA Special Fund for Agro-Scientific Research in the Public Interest of China (no. 201103003) for funding.

Footnotes

Shah Fahad and Faheem Ahmed Khan have contributed equally to this work.

References

- Azhakanandam K, Weissinger SM, Nicholson JS, Qu R, Weissinger AK. Amplicon-plus targeting technology (APTT) for rapid production of a highly unstable vaccine protein in tobacco plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2007;63:393–404. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-9096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendich AJ. Why do chloroplasts and mitochondria contain so many copies of their genome? BioEssays. 1987;6:279–282. doi: 10.1002/bies.950060608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothe J, Nykiforuk C, Shen Y, Zaplachinski S, Szarka S, Kuhlman P, Murray E, Morck D, Moloney MM. Seed-based expression systems for plant molecular farming. Plant Biotechnol J. 2010;8:588–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broothaerts W, Mitchell HJ, Weir B, Kaines S, Smith LMA, Yang W, Maye JE, Roa-Rodríguez C, Jefferson RA. Gene transfer to plants by diverse species of bacteria. Nature. 2005;433:629–633. doi: 10.1038/nature03309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann RC, Asad S, Wolf JN, Mohannath G, Bisaro DM. Geminivirus AL2 and L2 proteins suppress transcriptional gene silencing and cause genome-wide reductions in cytosine methylation. J Virol. 2009;83:5005–5013. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01771-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canizares MC, Nicholson L, Lomonossoff GP. Use of viral vectors for vaccine production in plants. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83:263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerovska N, Hoffmeisterova H, Moravec T, Plchova H, Folwarczna J, Synkova H, Ryslava H, Ludvikova V, Smahel M. Transient expression of Human papilloma virus type 16 L2 epitope fused to N- and C-terminus of coat protein of Potato virus X in plants. J Biosci. 2012;37:125–133. doi: 10.1007/s12038-011-9177-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chebolu S, Daniell H. Chloroplast-derived vaccine antigens and biopharmaceuticals: expression, folding, assembly and functionality. Curr Top Microbiol. 2009;332:33–54. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-70868-1_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chichester JA, Jones RM, Green BJ, Stow M, Miao F, Moonsammy G, Streatfield SJ, Yusibov V. Safety and immunogenicity of a plant-produced recombinant hemagglutinin-based influenza vaccine (HAI-05) derived from A/Indonesia/05/2005 (H5N1) influenza virus: a phase 1 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study in healthy adults. Viruses. 2012;4:3227–3244. doi: 10.3390/v4113227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical trials for autologous vaccine for follicular lymphoma (2014) clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01022255. Accessed 26 June 2014

- D’Aoust MA, Lavoie PO, Couture MM, Trépanier S, Guay JM, Dargis M, Mongrand S, Landry N, Ward BJ, Vézina LP. Influenza virus-like particles produced by transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana induce a protective immune response against a lethal viral challenge in mice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2008;6:930–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniell H, Datta R, Varma S, Gray S, Lee SB. Containment of herbicide resistance through genetic engineering of the chloroplast genome. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:345–348. doi: 10.1038/nbt0498-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoodi-Semiromi A, Schreiber M, Nalapalli S, Verma D, Singh ND, Banks RK, Chakrabarti D, Daniell H. Chloroplast-derived vaccine antigens confer dual immunity against cholera and malaria by oral or injectable delivery. Plant Biotechnol J. 2010;8:223–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahad S, Nie L, Khan FA, Chen Y, Hussain S, Wu C, et al. Disease resistance in rice and the role of molecular breeding in protecting rice crops against diseases. Biotechnol Lett. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10529-014-1510-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert CL, Klopfer SO, Martin JC, Schödel FP, Bhuyan PK. Safety and immunogenicity of a modified process hepatitis B vaccine in healthy adults >50 years. Hum Vaccine. 2012;7:1336–1342. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.12.18333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleba Y, Klimyuk V, Marillonnet S. Magnifection: a new platform for expressing recombinant vaccines in plants. Vaccine. 2005;23:2042–2048. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeddel DV, et al. Expression in Escherichia coli of chemically synthesized genes for human insulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:106–110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorantala J, Grover S, Goel D, Rahi A, Jayadev Magani SK, Chandra S, Bhatnagar R. A plant based protective antigen [PA(dIV)] vaccine expressed in chloroplasts demonstrates protective immunity in mice against anthrax. Vaccine. 2011;29:4521–4533. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn KS, Singh N, Giambrone J, Wu H. Using transgenic plants as bioreactors to produce edible vaccines. J Biotechnol Res. 2012;4:92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann R. The sexual inheritance of plant organelles. In: Daniell H, Chase C, editors. Molecular biology and biotechnology of plant organelles. Netherlands: Springer; 2004. pp. 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Haq TA, Mason HS, Clements JD, Arntzen CJ. Oral immunization with a recombinant bacterial antigen produced in transgenic plants. Science. 1995;268:714–716. doi: 10.1126/science.7732379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes JR, Cunningham J, Seefried AV, Lennick M, Garvin RT, Shen S. Development of a genetically-engineered, candidate polio vaccine employing the self-assembling properties of the tobacco mosaic virus coat protein. Nat Biotechnol. 1986;4:637–641. doi: 10.1038/nbt0786-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefferon KL. Recent advances in virus expression vector strategies for vaccine production in plants. Virol Mycol. 2012;1:105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt A, Cafferkey R, Bowdish K. Production of antibodies in transgenic plants. Nature. 1989;342:76–78. doi: 10.1038/342076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi T, Takaiwa F. Peptide immunotherapy for allergic diseases using a rice-based edible vaccine. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6:455–460. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000246621.34247.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsch RB, Fry JE, Hoffmann NL, Eicholz D, Rogers SG, Fraley RT. A simple and general method for transferring genes into plants. Science. 1985;227:1229–1231. doi: 10.1126/science.227.4691.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdebine LM. Production of pharmaceutical proteins by transgenic animals. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;32:107–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Chen Q, Hjelm B, Arntzen C, Mason H. A DNA replicon system for rapid high-level production of virus-like particles in plants. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;103:706–714. doi: 10.1002/bit.22299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human insulin receives FDA approval (1982) FDA. Drug Bull 12:18-19 [PubMed]

- Hwang MS, Lindenmut BE, McDonald KA, Falk BW. Bipartite and tripartite cucumber mosaic virus-based vectors for producing the Acidothermus cellulolyticusendo-1,4-β-glucanase and other proteins in non-transgenic plants. BMC Biotechnol. 2012;12:66. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-12-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura K, Hirose T, Crea R, Riggs AD, Heyneker HL, Bolivar F, Boyer HW. Expression in Escherichia coli of a chemically synthesized gene for the hormone somatostatin. Science. 1977;198:1056–1063. doi: 10.1126/science.412251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joensuu JJ, Conley AJ, Lienemann M, Brandle JE, Linder MB, Menassa R. Hydrophobin fusions for high-level transient protein expression and purification in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Physiol. 2009;152:622–633. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.149021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagale S, Uzuhashi S, Wigness M, Bender T, Yang W, Borhan MH, Rozwadowski K. TMV-gate vectors: gateway compatible tobacco mosaic virus based expression vectors for functional analysis of proteins. Sci Rep. 2012;2:874. doi: 10.1038/srep00874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagarajan S, Tolf C, Lundgren A, Waldenström J, Brodelius PE. Transient expression of hemagglutinin antigen from low pathogenic avian influenza A (H7N7) in Nicotiana benthamiana. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanoria S, Burma PK. A 28 nt long synthetic 5′UTR (synJ) as an enhancer of transgene expression in dicotyledonous plants. BMC Biotechnol. 2012;12:1472–6750. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-12-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapila J, DeRycke R, Van Montagu M, Angenon G. An Agrobacterium-mediated transient gene expression system for intact leaves. Plant Sci. 1997;122:101. [Google Scholar]

- Kittiwongwattana C, Lutz K, Clark M, Maliga P. Plastid marker gene excision by the phiC31 phage site-specific recombinase. Plant Mol Biol. 2007;64:137–143. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl TO, Hitzeroth II, Christensen ND, Rybicki EP. Expression of HPV-11 L1 protein in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum. BMC Biotechnol. 2007;7:56. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-7-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolotilin I, Kaldis A, Devriendt B, Joensuu J, Cox E, Menassa R. Production of a subunit vaccine candidate against porcine post-weaning diarrhea in high-biomass transplastomic tobacco. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova TV, Baschieri S, Donini M, Marusic C, Benvenuto E, Dorokhov YL. Transient expression systems for plant-derived biopharmaceuticals. Exp Rev Vaccines. 2010;9:859–876. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon T, Sharma P, Ikegami M. Suppressor of RNA silencing encoded by the monopartite tomato leaf curl Java begomovirus. Arch Virol. 2007;152:1273–1282. doi: 10.1007/s00705-007-0957-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koya V, Moayeri M, Leppla SH, Daniell H. Plant-based vaccine: mice immunized with chloroplast-derived anthrax protective antigen survive anthrax lethal, toxin challenge. Infect Immun. 2005;73:8266–8274. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8266-8274.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laanger E. New plant expression systems drive vaccine innovation and opportunity. BioProcess Int. 2011;9:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Laguía-Becher M, Martín V, Kraemer M, Corigliano M, Yacono ML, Goldman A, Clemente M. Effect of codon optimization and subcellular targeting on Toxoplasma gondii antigen SAG1 expression in tobacco leaves to use in subcutaneous and oral immunization in mice. BMC Biotechnol. 2010;10:52. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-10-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry N, Ward BJ, Trépanier S, Montomoli E, Dargis M, Lapini G, Vézina LP. Preclinical and clinical development of plant-made virus-like particle vaccine against avian H5N1 influenza. PLoS One. 2010;5:0015559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen JS, Curtis WR. RNA viral vectors for improved Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression of heterologous proteins in Nicotiana benthamiana cell suspensions and hairy roots. BMC Biotechnol. 2012;12:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-12-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lico C, Chen Q, Santi L. Viral vectors for production of recombinant proteins in plants. J Cell Physiol. 2008;216:366–377. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindbo JA. High-efficiency protein expression in plants from agroinfection: compatible tobacco mosaic virus expression vectors. BMC Biotechnol. 2007;7:52. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-7-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindbo JA. TRBO: a high-efficiency tobacco mosaic virus rna-based overexpression Vector. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:1161–1170. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.106377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Yuan JS, Stewart CN., Jr Advanced genetic tools for plant biotechnology. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:781–793. doi: 10.1038/nrg3583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lossl AG, Waheed MT. Chloroplast-derived vaccines against human diseases: achievements, challenges and scopes. Plant Biotechnol J. 2011;9:527–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Wang L, Webster DE, Campbell AE, Coppel RL. Production, characterization and immunogenicity of a plant-made plasmodium antigen-the 19 kDa C-terminal fragment of plasmodium yoelii merozoite surface protein 1. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;94:151–161. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M, Yan Y, Huang L, Chen M, Zhao H. Virus-induced gene-silencing in wheat spikes and grains and its application in functional analysis of HMW-GS-encoding genes. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:141. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldaner FR, Aragão FJL, dos Santos FB, Franco OL, Lima MdRQ, de Oliveira Resende R, Vasques RM, Nagata T. Dengue virus tetra epitope peptide expressed in lettuce chloroplasts for potential use in dengue diagnosis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:5721–5729. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-4918-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maliga P. Plastid transformation in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:289–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marillonnet S, Giritch A, Gils M, Kandzia R, Klimyuk V, Gleba Y. In planta engineering of viral RNA replicons: efficient assembly by recombination of DNA modules delivered by Agrobacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6852–6857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400149101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marillonnet S, Thoeringer C, Kandzia R, Klimyuk V, Gleba Y. Systemic Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transfection of viral replicons for efficient transient expression in plants. Nat Biotech. 2005;23:718–723. doi: 10.1038/nbt1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez de Alba AE, Elvira-Matelot E, Vaucheret H. Gene silencing in plants: a diversity of pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829:1300–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason HS, Lam DM, Arntzen CJ. Expression of hepatitis B surface antigen in transgenic plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11745–11749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason HS, Haq TA, Clements JD, Arntzen CJ. Edible vaccine protects mice against Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin (LT): potatoes expressing a synthetic LT-B gene. Vaccine. 1998;16:1336–1343. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)80020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T, Matsuura H, Sawada K, Takita E, Kinjo S, Takenami S, Ueda K, Nishigaki N, Yamasaki S, Hata K, Yamaguchi M, Demura T, Kato K. High level expression of transgenes by use of 5′-untranslated region of the Arabidopsis thaliana arabinogalactan-protein 21 gene in dicotyledons. Plant Biotechnol J. 2012;29:319–322. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick AA, Reddy S, Reinl SJ, Cameron TI, Czerwinkski DK, Vojdani F, Hanley KM, Garger SJ, White EL, Novak J, Barrett J, Holtz RB, Tusé D, Levy R. Plant-produced idiotype vaccines for the treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: safety and immunogenicity in a phase I clinical study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10131–10136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803636105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin M, Gecchele E, Capaldi S, Pezzotti M, Avesani L. Comparative evaluation of recombinant protein production in different biofactories: the green perspective. BioMed Res Intern. 2014;2014:14. doi: 10.1155/2014/136419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller T, Fanton M, Webb S (2004) Transforming tobacco cell line containing sequences encoding antigens (such as hemagglutinin/neuraminidase protein from Newcastle Disease Virus), culturing, washing, suspending in lysis buffer, disrupting cells, then separating debris; vaccines. US Patent 0268442A1

- Mishra N, Gupta PN, Khatri K, Goyal AK, Vyas SP. Edible vaccine: a new approach to oral immunization. Indian J Biotechnol. 2008;7:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Modelska A, Dietzschold B, Sleysh N, Fu ZF, Steplewski K, Hooper DC, Koprowski H, Yusibov V. Immunization against rabies with plant-derived antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2481–2485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moravec T, Schmidt MA, Herman EM, Woodford-Thomas T. Production of Escherichia coli heat labile toxin (LT) B subunit in soybean seed and analysis of its immunogenicity as an oral vaccine. Vaccine. 2007;25:1647–1657. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer E, Maclean JM, Mbewana S, Buys A, Williamson AL, Hitzeroth II, Rybicki EP. Setting up a platform for plant-based influenza virus vaccine production in South Africa. BMC Biotechnol. 2012;12:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-12-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nochi T, Takagi H, Yuki Y, Yang L, Masumura T, Mejima M, Nakanishi U, Matsumura A, Uozumi A, Hiroi T, Morita S, Tanaka K, Takaiwa F, Kiyono H. Rice-based mucosal vaccine as a global strategy for cold-chain and needle-free vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10986–10991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703766104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzaci M, Piazzolla G, Vitti A, Lapelosa M, Tortorella C, Stella I, Natilla A, Antonaci S, Piazzolla P. Cucumber mosaic virus as a presentation system for a double hepatitis C virus-derived epitope. Arch Virol. 2007;152:915–928. doi: 10.1007/s00705-006-0916-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzaci M, Bochicchio I, De Stradis A, Vitti A, Natilla A, Piazzolla P, Tamburro AM. Structural and biological properties of cucumber mosaic virus particles carrying hepatitis C virus-derived epitopes. J Virol Methods. 2009;155:118–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzaci M, Vitti A, Condelli V, Lanorte MT, Tortorella C, Boscia D, Piazzolla P, Piazzolla G. In vitro stability of cucumber mosaic virus nanoparticles carrying a Hepatitis C virus-derived epitope under simulated gastrointestinal conditions and in vivo efficacy of an edible vaccine. J Virol Methods. 2010;165:211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyret H, Lomonossoff GP. The pEAQ vector series: the easy and quick way to produce recombinant proteins in plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2013;83:51–58. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai O, Panchagnula R. Insulin therapies-past, present and future. Drug Discov Today. 2001;6:1056–1061. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(01)01962-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pniewski T, Kapusta J, Bociąg P, Wojciechowicz J, Kostrzak A, Gdula M, Fedorowicz-Strońska O, Wójcik P, Otta H, Samardakiewicz S, Wolko B, Płucienniczak A. Low-dose oral immunization with lyophilized tissue of herbicide-resistant lettuce expressing hepatitis B surface antigen for prototype plant-derived vaccine tablet formulation. J Appl Genet. 2011;52:125–136. doi: 10.1007/s13353-010-0001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogrebnyak N, Markley K, Smirnov Y, Brodzik R, Bandurska K, Koprowski H, Golovkin M. Collard and cauliflower as a base for production of recombinant antigens. Plant Sci. 2006;171:677–685. [Google Scholar]

- Pogue GP, Holzberg S (2012) Transient virus expression systems for recombinant protein expression in dicot- and monocotyledonous plants. In: Dhal NK. (Ed.) Plant Science, ISBN: 978-953-51-0905-1, InTech. doi: 10.5772/54187

- Quesada-Vargas T, Ruiz ON, Daniell H. Characterization of heterologous multigene operons in transgenic chloroplasts: transcription, processing, and translation. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1746–1762. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.063040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rader RA. FDA biopharmaceutical product approvals and trends in 2012. BioProcess Int. 2013;11:18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rigano MM, Guzman GD, Walmsley AM, Frusciante L, Barone A. Production of pharmaceutical proteins in solanaceae food crops. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:2753–2773. doi: 10.3390/ijms14022753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales-Mendoza S, Soria-Guerra RE, López-Revilla R, Moreno-Fierros L, Alpuche-Solís AG. Ingestion of transgenic carrots expressing the Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit protects mice against cholera toxin challenge. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27:79–84. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0439-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg Y, Sack M, Montefiori D, Forthal D, Mao L, Hernandez-Abanto S, Urban L, Landucci G, Fischer R, Jianget X. Rapid High-level production of functional hiv broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies in transient plant expression systems. PLoS One. 2012;8(3):e58724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Infante N, Govea-Alonso DO, Alpuche-Solís AG, García-Hernández AL, Soria-Guerra RE, Paz-Maldonado LMT, Ilhuicatzi-Alvarado D, Varona-Santos JT, Verdín-Terán L, Korban SS, Moreno-Fierros L, Rosales-Mendoza S. A chloroplast-derived C4V3 polypeptide from the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is orally immunogenic in mice. Plant Mol Biol. 2012;78:337–349. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9870-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf S, Karcher D, Bock R. Determining the transgene containment level provided by chloroplast transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6998–7002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700008104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury F, Lomonossoff GP. Extremely high-level and rapid transient protein production in plants without the use of viral replication. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:1212–1218. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.126284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury F, Lomonossoff GP. Transient expressions of synthetic biology in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2014;19:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S, Yamagishi N, Yoshikawa N. Efficient virus-induced gene silencing in apple, pear and Japanese pear using Apple latent spherical virus vectors. Plant Methods. 2011;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sempere RN, Gómez P, Truniger V, Aranda MA. Development of expression vectors based on pepino mosaic virus. Plant Methods. 2011;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin YJ, Kwon TH, Seo JY, Kim TJ. Oral immunization of fish against iridovirus infection using recombinant antigen produced from rice callus. Vaccine. 2013;31:5210–5215. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji Y, Chichester JA, Jones M, Manceva SD, Damon E, Mett V, Musiychuk K, Bi H, Farrance C, Shamloul M, Kushnir N, Sharma S, Yusibov V. Plant-based rapid production of recombinant subunit hemagglutinin vaccines targeting H1N1 and H5N1 influenza. Hum Vaccine. 2011;7:41–50. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.0.14561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria-Guerra RE, Rosales-Mendoza S, Márquez-Mercado C, López-Revilla R, Castillo-Collazo R, Alpuche-Solís AG. Transgenic tomatoes express an antigenic polypeptide containing epitopes of the diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus exotoxins, encoded by a synthetic gene. Plant Cell Rep. 2007;26:961–968. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0306-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria-Guerra RE, Rosales-Mendoza S, Moreno-Fierros L, López-Revilla R, Alpuche-Solís AG. Oral immunogenicity of tomato-derived sDPT polypeptide containing Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Bordetella pertussis and Clostridium tetaniexotoxin epitopes. Plant Cell Rep. 2011;30:417–424. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0973-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svab Z, Maliga P. Exceptional transmission of plastids and mitochondria from the transplastomic pollen parent and its impact on transgene containment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7003–7008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700063104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S, Verma PC, Singh PK, Tuli R. Plants as bioreactors for the production of vaccine antigens. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27:449–467. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuhara D, et al. Rice-based oral antibody fragment prophylaxis and therapy against rotavirus infection. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3829–3838. doi: 10.1172/JCI70266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treanor JJ, El Sahly H, King J, Graham I, Izikson R, Kohberger R, Patriarca P, Cox M. Protective efficacy of a trivalent recombinant hemagglutinin protein vaccine [FluBlok(R)] against influenza in healthy adults: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Vaccine. 2011;29:7733–7739. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tregoning JS, Clare S, Bowe F, Edwards F, Fairweather N, Qazi O, Nixon PJ, Maliga P, Dougan G, Hussell T. Protection against tetanus toxin using a plant-based vaccine. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1320–1326. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turpen TH, Reini SJ, Charoenvit Y, Hoffman SL, Fallarme V, Grill LK. Malarial epitopes expressed on the surface of recombinant tobacco mosaic virus. Nat Biotechnol. 1995;13:53–57. doi: 10.1038/nbt0195-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma D, Daniell H. Chloroplast vector systems for biotechnology applications. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:1129–1143. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.106690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waheed MT, Gottschamel J, Hassan SW, Lösslet AG. Plant-derived vaccines: an approach for affordable vaccines against cervical cancer. Hum Vaccines Immunotherap. 2012;8:403–406. doi: 10.4161/hv.18568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HH, Yin WB, Hu ZM. Advances in chloroplast engineering. J Genet Genomics. 2009;36:387–398. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi N, Yoshikawa N. Virus-induced gene silencing in soybean seeds and the emergence stage of soybean plants with apple latent spherical virus vectors. Plant Mol Biol. 2009;71:15–24. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9505-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TG, Yang MS. Current trends in edible vaccine development using transgenic plants. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2010;15:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Li X, Yang H, Qian Y, Zhang Y, Fang R, Chen X. Immunogenicity and virus-like particle formation of rotavirus capsid proteins produced in transgenic plants. Sci China Life Sci. 2011;54:82–89. doi: 10.1007/s11427-010-4104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Gray BN, Ahner BA, Hanson MR. Bacteriophage 5′ untranslated regions for control of plastid transgene expression. Planta. 2013;237:517–527. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1770-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuki Y, et al. Induction of toxin-specific neutralizing immunity by molecularly uniform rice-based oral cholera toxin B subunit vaccine without plant-associated sugar modification. Plant Biotechnol J. 2013;11:799–808. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusibov V, Streatfield SJ, Kushnir N. Clinical development of plant-produced recombinant pharmaceuticals: vaccines, antibodies and beyond. Hum Vaccine. 2011;7(3):313–321. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.3.14207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YX, Lee MY, Ng JM, Chye ML, Yip WK, Zee SY, Lam E. A truncated hepatitis E virus ORF2 protein expressed in tobacco plastids is immunogenic in mice. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:306–312. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i2.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorrilla-Lopez U, Masip G, Arj´o G, Bai C, Banakar R, et al. Engineering metabolic pathways in plants by multigene transformation. Int J Dev Biol. 2013;57:565–576. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.130162pc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]