Abstract

IL-33 has been deorphanized as a member of the IL-1 family and has key roles as an alarmin and cytokine with potent capacity to drive type 2 inflammation. This has led to a plethora of studies surrounding its role in chronic diseases with a type 2 inflammatory component. Here, we review the roles of IL-33 in two chronic respiratory diseases, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). We discuss the hallmark and paradigm-shifting studies that have contributed to our understanding of IL-33 biology. We cover animal studies that have elucidated the mechanisms of IL-33 and assessed the role of anti-IL-33 treatment and immunization against IL-33. We highlight key clinical evidence for the potential of targeting increased IL-33 in respiratory diseases including exacerbations, and we outline current clinical trials using an anti-IL-33 monoclonal antibody in asthma patients. Finally, we discuss some of the challenges that have arisen in IL-33 biology and highlight potential future directions in targeting this cytokine in chronic respiratory diseases.

Keywords: IL-33, anti-IL-33, ST2, eosinophils, asthma, COPD

Introduction

Since the deorphanization of interleukin (IL)-33 as a member of the IL-1 family in 2003, a plethora of studies assessing its roles in disease have emerged, with >3000 publications in Pubmed. IL-33 (previously known as nuclear factor from high endothelium venules [NF-HEV] and IL-1 family 11 [IL-1F11]) has two main forms. The full length IL-33 (f-IL-33, fIL-33, or IL-33FL) form consists of 270 amino acids, resides predominantly in the nucleus, and regulates gene expression. The cleaved mature IL-33 (m-IL-33, processed/cleaved) form is an extracellular cytokine released after cells sense inflammatory signals or undergo necrosis. Processing of f-IL-33 occurs through serine proteases, neutrophil elastase, cathepsin-G, and proteinase-3 in neutrophils and mast cells, which results in m-IL-33.1 In addition, there is also alternate splicing of IL-33.2 Inactivation of m-IL-33 occurs by binding to soluble suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (sST2), processing by caspase-3 and -7 or by oxidation (forming of two disulfide bonds).3

Full length IL-33 nuclear localization has been identified in numerous cell types, including epithelial and endothelial cells, fibroblasts, airway smooth muscle, and mast cells. Both the f-IL-33 and m-IL-33 can act on the ST2 receptor (otherwise known as IL-1LR1 [interleukin-1-like] receptor, T1ST2 receptor, IL-33R). Various subtypes of the receptor exist, including the transmembrane bound ST2L receptor which is expressed in most cell types, including macrophages and type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), sST2, and ST2 V which are expressed in gastrointestinal organs. m-IL-33 has greater bioactivity than f-IL-33. Binding of IL-33 to ST2 results in recruitment of IL-1 receptor accessory protein (IL-1RA), and subsequent downstream signaling via myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88), IL-1R-associated kinase-1 and -4 (IRAK1/4), tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK), and p38 (reviewed in ref (4)).

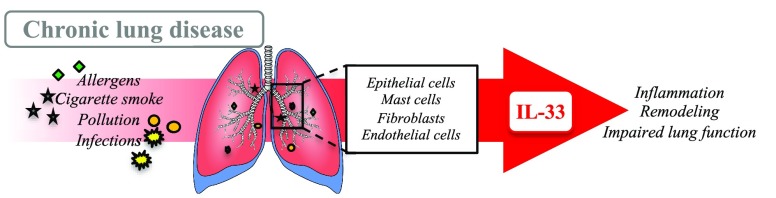

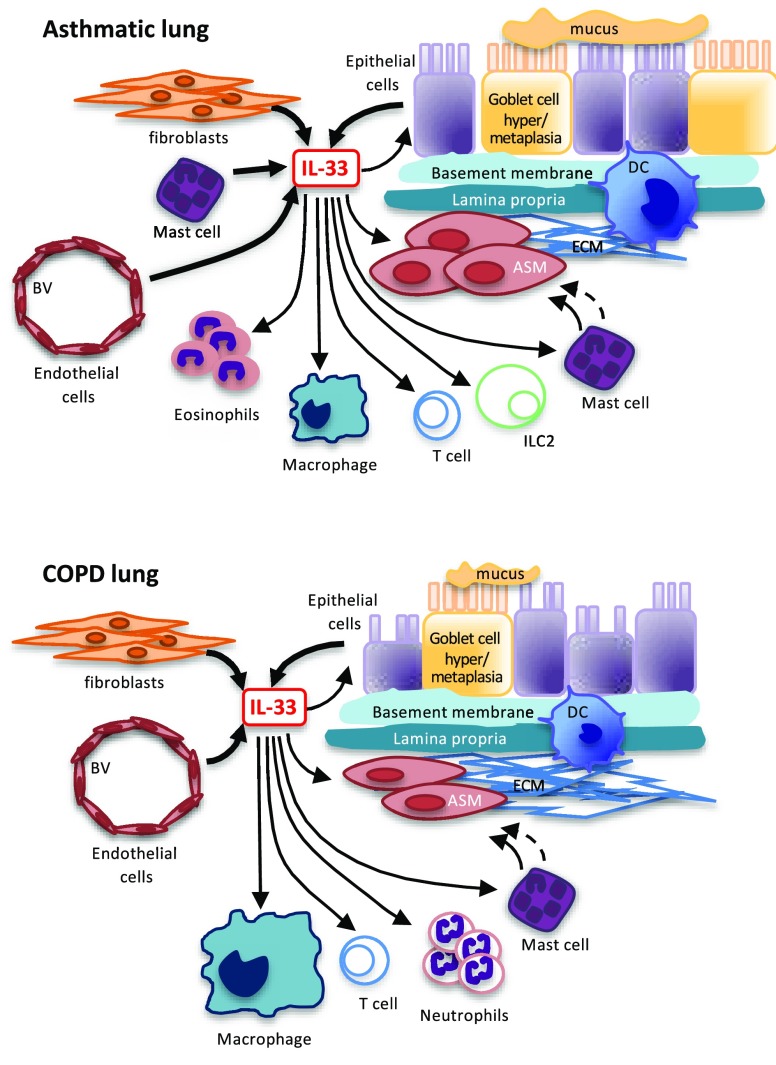

In the respiratory tract, IL-33 is predominantly released from epithelial cells, alveolar type II epithelial cells, endothelial cells, mast cells, and fibroblasts5−7 (Figure 1). It serves as an “alarmin” following insult with inhaled stimuli such as allergens, infections, pollution, and cigarette smoke, which results in activation, migration, and recruitment of innate and adaptive immune cells including eosinophils, ILC2s, mast cells, T cells, natural killer T cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and hematopoietic progenitor cells8 and production of type 2 (Th2) cytokines including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 (reviewed in refs (5), (9), and (10)). Like many pleotropic cytokines, the potency of IL-33 is dependent on the timing, onset, and kinetics of responses (reviewed in ref (11)). Recent studies demonstrate a key role of IL-33 in mast cell to airway smooth muscle cell crosstalk, with both these cell types producing IL-33, and IL-33 activation of mast cells increasing IL-13 and subsequent airway smooth muscle contraction in vitro and in vivo.12,13 Furthermore, IL-33 activation of mast cells can lead to the recruitment and activation of neutrophils (reviewed in ref (11)). Thus, diseases with increased mast cell activation may be benefit from targeting IL-33.9,10

Figure 1.

Role of IL-33 in asthmatic and COPD lungs. IL-33 is released from epithelial cells, fibroblasts, mast cells, and endothelial cells with actions on multiple cell types within the airways, including neutrophils, eosinophils, macrophages, T cells, ILC2s, mast cells, and airway smooth muscle. ASM = airway smooth muscle, BV = blood vessel, DC = dendritic cell, ECM = extracellular matrix, IL-33 = interleukin-33, ILC2 = innate lymphoid cell. Thick →, release of IL-33; thin →, direct response of IL-33; thin broken →, indirect response of IL-33

With increasing research into its biology, there has been a significant increase in the reagents available to assess IL-33 levels and functional roles in disease, including protein- and PCR-based gene assays, genetically modified mice, and pharmacological inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies. Protein assays exist for studying IL-33 in different samples. In serum, Ketelaar et al. comprehensively assessed well-characterized asthmatic human serum against four human ELISA kits specifically designed for measuring serum IL-33.14 The authors obtained very variable data with many samples below the lower limit of detection, and none of the kits could differentiate between free IL-33 and IL-33 bound to sST2. They suggest that the post-translational modifications (including cathepsin or elastase cleavage or oxidation of IL-33) may have contributed to the variable results. Nonetheless, they have clearly demonstrated that sST2 can interfere with measurements of IL-33, which must be taken into account in all studies assessing IL-33, including in samples other than serum. IL-33 Citrine reporter mice (Il33Cit/+) have been useful in overcoming some of the limitations of detecting IL-33 ex vivo as citrine can be measured as a surrogate marker for IL-33.15Il33–/– mice (Il33Cit/Cit) have also been used, as a double knock-in of citrine into the IL-33 gene causes it to be depleted.15St2–/– mice16 have both transmembrane and soluble ST2 deleted, which interestingly has no effect on basal immune function. However, it is important to note that when St2–/– mice are exposed to experimental asthma, TSLP-driven IL-9+ and IL-13+ ILC2s subpopulations emerge,17 which is in contrast to wild type mice which have primarily IL-33/ST2 ILC2 populations. Thus, compensatory mechanisms are important to consider in these genetically modified mice exposed to models of respiratory diseases.

Most importantly, there are pharmacological activators and inhibitors of IL-33. This includes recombinant mouse and human protein activators, and helminth parasite alarmin release inhibitor (HpARI) and anti-IL-33 monoclonal antibodies. The known specific effects of IL-33 in asthma, COPD and exacerbations are outlined below. Importantly, IL-33 is also implicated in other lung diseases such as obstructive sleep apnea and this has been comprehensively reviewed by Gabryelska et al.18

IL-33 in Asthma

Asthma affects ∼339 million individuals worldwide, with the prevalence increasing in developing countries.19 It is a heterogeneous disease characterized by episodes of chest tightness, wheezing, shortness of breath, and airway obstruction.20 Severity is characterized by impaired lung function (lower than predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1]) and airways that are hyper-responsive (AHR), where they contract too easily and too much to stimuli.21 Symptoms are largely caused by inflammation and remodelling in chronic disease.22 While the causes of the induction of asthma are incompletely understood, early life viral23 and bacterial infections24 are significant risk factors, and associated IL-33 responses may play a role in the development of asthma in children and adulthood (reviewed in ref (25)).

The inflammatory component of asthma is classically considered as being driven by type 2 immune responses (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13) with eosinophilic inflammation; however, there are subgroups of patients that have increased type 1/17 immune responses associated with neutrophilic inflammation.20,26 Furthermore, a systematic review and murine studies have demonstrated that inflammation and remodelling in asthma may not be linked, suggesting that remodelling may be independent of inflammation and AHR.27,28 While mainstay therapies (glucocorticoids and beta-agonists) target inflammation and AHR, some patients are resistant to steroids and thereby do not respond to current medication through a variety of mechanisms,9,20,29 and current treatment does not effectively target airway remodelling.

Research into IL-33 in asthma has exponentially increased in the last 20 years. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified genetic variations in both the IL33 and IL1RL1 genes (the latter of which encodes the ST2 receptor) in subjects from many different geographical ancestries, including European, North American, African, Mexican, and Asian populations, which are strongly associated with asthma compared with healthy controls30−32 and confirmed the key role of IL1RL1 in regulating type 2 inflammation.2 Unsurprisingly, multiple studies to date have demonstrated increased IL-33 and soluble ST2 in sputum and serum from asthma patients compared with controls and correlated IL-33 with disease severity.33 In support of these studies, identification of a rare IL33 loss-of-function mutation (rs1465997587-C) results in a truncated IL-33 protein that has normal intracellular localization but is dysfunctional (i.e., it cannot bind to ST2 or ST2-expressing cells), which is associated with lower blood eosinophil counts and reduced risk of asthma.34 In addition, IL-33 expression also is increased in lung biopsies from pediatric severe asthmatics, and in a neonatal mouse model of allergic airway disease, the authors demonstrated that IL-33 induces airway remodelling in the absence of IL-13, suggesting a direct role of IL-33 on airway remodelling in asthma.35

Nevertheless, the role of IL-33 in asthma is complex, and signaling occurs through a plethora of cells and pathways. The first murine study to assess the potential for therapeutic targeting IL-33 was in 2014, whereby mice were sensitized and challenged with ovalbumin (OVA) prior to administration of anti-IL-33 or soluble ST2. Treatment with both compounds reduced eosinophils and type 2 associated cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10).36 This study was confirmed in St2–/– mice, whereby OVA treatment resulted in significantly reduced hallmark features of allergic airway disease compared with wild type controls37 and in a mixed allergen model of allergic airways disease.17 In addition to anti-IL-33 and soluble ST2 administration, immunization against IL-33 in house dust mite models of allergic airways disease also inhibits AHR and inflammation,38 supporting the key role of IL-33 in asthma.

Since the seminal study of anti-IL-33 treatment in an OVA model and following supporting studies, additional mechanisms of IL-33 have been discovered, including (1) the potent role of IL-33 in ILC2 activation which leads to increased IL-13 and AHR,39 (2) activation of basophils in allergic asthma,40 and (3) IL-33-/IL-13-dependent homing of hematopoietic progenitor cells to the lung in allergic asthma.8

As IL-33 exists in multiple forms (full length or mature), it is surprising that many studies to date have not identified whether the pathogenic role of IL-33 in murine models and/or human cell experiments is caused by the full length or mature form. An important study by Gordon et al. in 20162 comprehensively assessed splice variants of IL-33 in human epithelial cells as an additional mechanism compared with necrotic release of mature IL-33 from cells of asthmatics. The authors comprehensively demonstrated that when IL-33 exons 3 and 4 are spliced in epithelial cells IL-33 localizes to the cytoplasm (rather than the nucleus) and is actively secreted but retains the ability to induce type 2 cytokines and IL-8. Interestingly, sputum cells from asthmatic patients that are IL-33-responsive are predominately basophils, mast cells, B cells, and eosinophils, but not macrophages and neutrophils, suggesting that splice variants of IL-33 (particularly exon 3 and 4) can activate other immune cells to cause persistent inflammation in asthma.

IL-33 in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a heterogeneous and progressive mild to very severe disease. All stages involve variable symptoms of cough, sputum production, fixed airway obstruction, breathing difficulties, and impaired lung function that all worsen as disease progresses. COPD is primarily caused by environmental irritants, including cigarette smoke and air pollution, and pathogenesis is driven by airway inflammation, remodelling (including an increase in the volume fraction of extracellular matrix within the airway smooth muscle layer), and the breakdown of parenchymal tissue.41,42 Conventionally, COPD is a Th1/Th17-driven disease that can occur with increased IL-33 levels in whole lung samples; however, a subset of patients also have eosinophilic inflammation. Thus, unlike asthma whereby IL-33 induces classical Th2 responses, IL-33 signaling in COPD is complex. IL-33 and ST2 expression is increased in the whole lung samples of COPD patients and in epithelial and endothelial cells,43−45 with increased IL-33 correlating with reduced lung function (a measure of disease severity).44 In addition, IL-33 is increased in plasma from stable COPD patients,46 which correlated with disease severity and increased eosinophil count in the blood, and an IL-33 gene polymorphism (rs1891385) is associated with impaired lung function (FEV1/forced viral capacity [FVC] ratio) and early onset COPD.47

A recent study also demonstrated that IL-33 induces the production of autoantibodies against alveolar epithelial cells in mice and humans;6 while COPD is not archetypally an autoimmune disease, these data suggest that there is an autoimmune response against lung tissue which, in part, can be initiated by IL-33. IL-33 is also increased in a caspase-4-dependent manner in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from COPD patients compared with healthy nonsmokers and smokers alone and when stimulated with ultrafine particles.48 This suggests that IL-33 may play a role in COPD in patients that is cigarette smoke independent.

In murine studies, IL-33 expression and protein levels are increased in models of cigarette smoke exposure,43,49 with an associated mechanism of pathology via IL-33-/IL-13-dependent increases in lung inflammation, mucin production,43 and collagen deposition.49 In asthma, IL-33 is primarily released from epithelial cells through necrotic/apoptotic mechanisms and results in ILC2 proliferation and increased IL-13. In contrast in COPD, oxidative stress can also enhance the expression and release of IL-33 in human airway epithelial cells,50 and the increased levels of IL-33 do not result in increased ILC2 proliferation as demonstrated in both human and murine studies.44,49

It is clear that IL-33 has different roles in asthma and COPD, which could, in part, be due to the different mechanisms of activation and its release from epithelial cells, although this requires additional studies. In addition, the splice variants or post-translational modifications of IL-33 in COPD may also explain why ILC2 proliferation is reduced compared with asthma.

IL-33 in Respiratory Disease Exacerbations

Exacerbations are a major cause of disease progression in asthma and COPD and are predominantly induced by infections.51 IL-33 drives influenza-induced asthma and COPD exacerbations but this does not correlate with increased ILC 2s, indicating an ILC2-independent mechanism.44,52 Multiple murine models of allergen and virus infection have demonstrated a key role for IL-33 in innate immunity and reducing interferon (IFN) responses/antiviral immunity.52−54 In a murine model of pneumonia virus and cockroach extract (model of virus and allergen exposure), IL-33 was increased following aeroallergen exposure, and dampened antiviral immunity by impairing IFNα production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells, through toll-like receptor-7 signaling.53 This response was reversed with anti-IL-33 treatment,54 and the suppressive effects of IL-33 on antiviral immunity were confirmed in healthy and asthmatic airway epithelial cells infected with rhinovirus.54 Following these studies, Ravanetti et al. comprehensively demonstrated that IL-33 drives viral-induced asthma exacerbations by instructing airway epithelial cells and dendritic cells to dampen the innate immune response, which prevents a Th1 dendritic cell phenotype (by increased induction of OX40L and reduced IL-12p35 expression).52 In addition, IL-33 had no effect on Th2-like responses in viral-induced exacerbations of asthma.52 Together, these studies clearly demonstrate a key role of IL-33 in dampening antiviral immunity, predominately in epithelial and dendritic cells, following allergen exposure and virus inoculation. However, it remains to be elucidated whether IL-33 reduces innate and adaptive antiviral immunity in COPD.

In paradigm-shifting studies, Kearley et al. identified that IL-33 plays a key role in influenza-induced exacerbations of acute cigarette smoke exposure.44 This study was the first to challenge the classical IL-33 inducing Th2 signaling responses in COPD. Mice exposed to cigarette smoke had increased epithelial IL-33 which primed the system so that when the mice were subsequently infected with influenza virus, IL-33 was released from epithelial cells and exacerbated viral-induced responses compared with virus infection alone.44 However, it is worth noting that in cigarette smoke/COPD, the induction of Th1 pro-inflammatory responses is caused by IL-33 activation of ST2+ cells that are not ILC2s,44 as ILC2s are reduced following cigarette smoke exposure.44,49

Recent evidence demonstrates that IL-33 can directly induce eosinophil differentiation from hematopoietic progenitor cells (in an IL-5-dependent manner) and increase ST2L expression in mature eosinophils.55 Interestingly, Verma et al. demonstrated that the IL-33/ST2 axis is crucial for persistent eosinophilic inflammation due to increased IL-9+ and IL-13+ ILC2s, but is redundant in mucus production and AHR.17

Targeting IL-33 in Human Clinical Trials

We know from clinical studies with targeted biologics in respiratory diseases that patient characterization prior to randomized control trials is crucial in determining the efficacy of new therapies.9,10,20 Over the past 10 years, there has been an exponential increase in biologics targeting specific cytokines and/or their receptors in asthma and COPD including IL-4 (dupilumab), IL-5 (mepolizumab, reslizumab, and benralizumab), IL-13 (levrikizumab and tralokinumab), and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP; tezepelumab).9,10,20 While these antibodies in well-stratified patient cohorts have shown promising results, there remains a proportion of patients that require additional therapies. Indeed, anti-IL-33 monoclonal antibodies are in clinical trials for the treatment of asthma and COPD (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of Ongoing Clinical Trials with Anti-IL-33 Monoclonal Antibody in Asthma and COPD.

| disease | patients | study design | clinicaltrials.gov identifier | phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| asthma | moderately severe patients | randomized double blind | NCT03207243 | II |

| asthma | mild allergic asthma | randomized | NCT03112577 | I |

| COPD | moderate to severe COPD | randomized double blind | NCT03546907 | I |

Etokimab (ANB020) is an anti-IL-33 monoclonal antibody currently in phase II clinical trials for eosinophilic asthma.56 In a phase IIa proof-of-concept study, 12 patients selected for high blood eosinophils (>300/μL) were administered a single intravenous dose of Etokimab and were required to maintain high-dose inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta-2 agonists. Treatment reduced blood eosinophils and improved FEV1 (relative to baseline) and asthma control questionnaire scores.56 In a different phase II clinical study that enrolled 296 asthmatics with high blood eosinophil counts, some patients were treated with SAR440340/REGN3500 (anti-IL-33 monoclonal antibody) and demonstrated improvements in lung function and asthma control compared with the placebo cohort.57 Data from a recent clinical trial of anti-IL-33 treatment in 12 atopic dermatitis patients also demonstrated safety and efficacy of anti-IL-33 treatment and indicated that in addition to reducing eosinophil numbers Etokimab treatment inhibited IL-33-induced neutrophil migration.58

Furthermore, a proof-of-concept study assessing the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of SAR440340/REGN3500 in moderate to severe COPD patients is ongoing, but no data has yet been reported from this study.59 Together, these studies demonstrate that in the cohorts examined Etokimab and SAR440340 are safe and well-tolerated with no adverse outcomes reported relating to the drug treatment. Thus, in addition to targeting respiratory diseases with a high eosinophilic component (such as some phenotypes of severe asthma, eosinophilic COPD, and the overlap between asthma and COPD [asthma–COPD overlap]), anti-IL-33 treatment could also be assessed in diseases with a neutrophilic component (such as some severe asthma phenotypes, COPD with a neutrophilic component, and asthma–COPD overlap).

Challenges and Future Directions

There are challenges that remain in accurately measuring IL-33 due to technical limitations and rapid processing of IL-33 in vivo and ex vivo; however, there is now unequivocal evidence from murine and human studies demonstrating the activation and release of IL-33 from many different cell types and its actions on various cells depending on the localization within the lung, which can increase disease severity. However, nuclear IL-33’s molecular mode of action is yet to be fully elucidated. Such studies would increase our understanding of nuclear IL-33 that may uncover novel associations between IL-33 and other pathways in disease. While clinical studies targeting IL-33 in eosinophil-driven airway diseases are in the early stages, preclinical and some clinical evidence suggests that targeting IL-33 may also provide therapeutic benefit in neutrophilic-driven disease. This may provide treatment options for patients who urgently require new and effective therapeutic options.

Acknowledgments

C.D. is funded by a Fellowship and Grants from the NHMRC (1120152 and 1138402), and P.M.H. is funded by a a Fellowship and Grants from the NHMRC (1079187 and 1175134).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AHR

airway hyper-responsiveness

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- f-IL-33

full length IL-33

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- GWAS

genome-wide association studies

- HpARI

helminth parasite alarmin release inhibitor

- IFN

interferon

- ILC2

type 2 innate lymphoid cells

- IL-1RA

IL-1 receptor accessory protein

- IL-33

interleukin-33

- IRAK1/4

IL-1R-associated kinase-1 and -4

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinases

- m-IL-33

mature IL-33

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MyD88

myeloid differentiation primary response 88

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhance of activated B cells

- OVA

ovalbumin

- sST2

soluble suppression of tumorigenicity 2

- Th2

type 2

- TRAF6

tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-associated factor 6

- TSLP

thymic stromal lymphopoietin

Author Present Address

# C.D.: Centre for Inflammation, Centenary Institute Building 93, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital grounds, John Hopkins Drive, Camperdown, NSW 2050, Australia.

Author Contributions

C.D. conceptualized and wrote the review article. P.M.H. critically evaluated and revised the article.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This article is made available for a limited time sponsored by ACS under the ACS Free to Read License, which permits copying and redistribution of the article for non-commercial scholarly purposes.

References

- Afonina I. S.; Muller C.; Martin S. J.; Beyaert R. (2015) Proteolytic Processing of Interleukin-1 Family Cytokines: Variations on a Common Theme. Immunity 42, 991–1004. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon E. D.; Simpson L. J.; Rios C. L.; Ringel L.; Lachowicz-Scroggins M. E.; Peters M. C.; Wesolowska-Andersen A.; Gonzalez J. R.; MacLeod H. J.; Christian L. S.; Yuan S.; Barry L.; Woodruff P. G.; Ansel K. M.; Nocka K.; Seibold M. A.; Fahy J. V. (2016) Alternative splicing of interleukin-33 and type 2 inflammation in asthma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 8765–8770. 10.1073/pnas.1601914113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E. S.; Scott I. C.; Majithiya J. B.; Rapley L.; Kemp B. P.; England E.; Rees D. G.; Overed-Sayer C. L.; Woods J.; Bond N. J.; Veyssier C. S.; Embrey K. J.; Sims D. A.; Snaith M. R.; Vousden K. A.; Strain M. D.; Chan D. T.; Carmen S.; Huntington C. E.; Flavell L.; Xu J.; Popovic B.; Brightling C. E.; Vaughan T. J.; Butler R.; Lowe D. C.; Higazi D. R.; Corkill D. J.; May R. D.; Sleeman M. A.; Mustelin T. (2015) Oxidation of the alarmin IL-33 regulates ST2-dependent inflammation. Nat. Commun. 6, 8327. 10.1038/ncomms9327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayrol C.; Girard J. P. (2018) Interleukin-33 (IL-33): A nuclear cytokine from the IL-1 family. Immunol Rev. 281, 154–168. 10.1111/imr.12619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan C.; Bourke J. E.; Vlahos R. (2016) Targeting the IL-33/IL-13 Axis for Respiratory Viral Infections. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 37, 252–261. 10.1016/j.tips.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.; Hu Y.; Chen Y.; Lv Z.; Wang J.; An G.; Du X.; Wang H.; Corrigan C. J.; Wang W.; Ying S. (2019) IL-33 induces production of autoantibody against autologous respiratory epithelial cells: a potential mechanism for the pathogenesis of COPD. Immunology 157, 137–150. 10.1111/imm.13054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallstrand T. S.; Hackett T. L.; Altemeier W. A.; Matute-Bello G.; Hansbro P. M.; Knight D. A. (2014) Airway epithelial regulation of pulmonary immune homeostasis and inflammation. Clin. Immunol. 151, 1–15. 10.1016/j.clim.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. G.; Gugilla A.; Mukherjee M.; Merim K.; Irshad A.; Tang W.; Kinoshita T.; Watson B.; Oliveria J. P.; Comeau M.; O’Byrne P. M.; Gauvreau G. M.; Sehmi R. (2015) Thymic stromal lymphopoietin and IL-33 modulate migration of hematopoietic progenitor cells in patients with allergic asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 135, 1594–1602. 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansbro P. M.; Kaiko G. E.; Foster P. S. (2011) Cytokine/anti-cytokine therapy - novel treatments for asthma?. Br. J. Pharmacol. 163, 81–95. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansbro P. M.; Scott G. V.; Essilfie A. T.; Kim R. Y.; Starkey M. R.; Nguyen D. H.; Allen P. D.; Kaiko G. E.; Yang M.; Horvat J. C.; Foster P. S. (2013) Th2 cytokine antagonists: potential treatments for severe asthma. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 22, 49–69. 10.1517/13543784.2013.732997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divekar R.; Kita H. (2015) Recent advances in epithelium-derived cytokines (IL-33, IL-25, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin) and allergic inflammation. Curr. Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 15, 98–103. 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur D.; Gomez E.; Doe C.; Berair R.; Woodman L.; Saunders R.; Hollins F.; Rose F. R.; Amrani Y.; May R.; Kearley J.; Humbles A.; Cohen E. S.; Brightling C. E. (2015) IL-33 drives airway hyper-responsiveness through IL-13-mediated mast cell: airway smooth muscle crosstalk. Allergy 70, 556–567. 10.1111/all.12593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman M. C.; Lai Y.; Nolin J. D.; Long S.; Chen C. C.; Piliponsky A. M.; Altemeier W. A.; Larmore M.; Frevert C. W.; Mulligan M. S.; Ziegler S. F.; Debley J. S.; Peters M. C.; Hallstrand T. S. (2019) Airway epithelium-shifted mast cell infiltration regulates asthmatic inflammation via IL-33 signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 4979–4991. 10.1172/JCI126402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketelaar M. E.; Nawijn M. C.; Shaw D. E.; Koppelman G. H.; Sayers I. (2016) The challenge of measuring IL-33 in serum using commercial ELISA: lessons from asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 46, 884–887. 10.1111/cea.12718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardman C. S.; Panova V.; McKenzie A. N. (2013) IL-33 citrine reporter mice reveal the temporal and spatial expression of IL-33 during allergic lung inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 488–498. 10.1002/eji.201242863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend M. J.; Fallon P. G.; Matthews D. J.; Jolin H. E.; McKenzie A. N. (2000) T1/ST2-deficient mice demonstrate the importance of T1/ST2 in developing primary T helper cell type 2 responses. J. Exp. Med. 191, 1069–1076. 10.1084/jem.191.6.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma M.; Liu S.; Michalec L.; Sripada A.; Gorska M. M.; Alam R. (2018) Experimental asthma persists in IL-33 receptor knockout mice because of the emergence of thymic stromal lymphopoietin-driven IL-9(+) and IL-13(+) type 2 innate lymphoid cell subpopulations. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 142, 793–803. 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabryelska A.; Kuna P.; Antczak A.; Bialasiewicz P.; Panek M. (2019) IL-33 Mediated Inflammation in Chronic Respiratory Diseases-Understanding the Role of the Member of IL-1 Superfamily. Front. Immunol. 10, 692. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enilari O.; Sinha S. (2019) The Global Impact of Asthma in Adult Populations. Ann. Glob Health 85, 2. 10.5334/aogh.2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansbro P. M.; Kim R. Y.; Starkey M. R.; Donovan C.; Dua K.; Mayall J. R.; Liu G.; Hansbro N. G.; Simpson J. L.; Wood L. G.; Hirota J. A.; Knight D. A.; Foster P. S.; Horvat J. C. (2017) Mechanisms and treatments for severe, steroid-resistant allergic airway disease and asthma. Immunol Rev. 278, 41–62. 10.1111/imr.12543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma D. S.; Kerstjens H. A. (1998) Characteristics of airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 158, S187–192. 10.1164/ajrccm.158.supplement_2.13tac170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saglani S.; Lloyd C. M. (2015) Novel concepts in airway inflammation and remodelling in asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 46, 1796–1804. 10.1183/13993003.01196-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansbro N. G.; Horvat J. C.; Wark P. A.; Hansbro P. M. (2008) Understanding the mechanisms of viral induced asthma: new therapeutic directions. Pharmacol. Ther. 117, 313–353. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansbro P. M.; Beagley K. W.; Horvat J. C.; Gibson P. G. (2004) Role of atypical bacterial infection of the lung in predisposition/protection of asthma. Pharmacol. Ther. 101, 193–210. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson K.; McSorley H. J. (2019) Interleukin-33 in the developing lung-Roles in asthma and infection. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 30, 503–510. 10.1111/pai.13040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa R.; Dua K.; Adcock I. M.; Horvat J. C.; Kim R. Y.; Hansbro P. M. (2019) Cellular mechanisms underlying steroid-resistant asthma. European Respiratory Review 28, 190096. 10.1183/16000617.0096-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. C. W.; Le Cras T. D.; Larcombe A. N.; Zosky G. R.; Elliot J. G.; James A. L.; Noble P. B. (2018) Independent and combined effects of airway remodelling and allergy on airway responsiveness. Clin. Sci. 132, 327–338. 10.1042/CS20171386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Rodriguez J. A.; Saglani S.; Rodriguez-Martinez C. E.; Oyarzun M. A.; Fleming L.; Bush A. (2018) The relationship between inflammation and remodeling in childhood asthma: A systematic review. Pediatr Pulmonol 53, 824–835. 10.1002/ppul.23968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Jing Li J.; Foster P. S.; Hansbro P. M.; Yang M. (2010) Potential therapeutic targets for steroid-resistant asthma. Curr. Drug Targets 11, 957–970. 10.2174/138945010791591412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt M. F.; Gut I. G.; Demenais F.; Strachan D. P.; Bouzigon E.; Heath S.; von Mutius E.; Farrall M.; Lathrop M.; Cookson W. (2010) A large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association study of asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 1211–1221. 10.1056/NEJMoa0906312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgerson D. G.; Ampleford E. J.; Chiu G. Y.; Gauderman W. J.; Gignoux C. R.; Graves P. E.; Himes B. E.; Levin A. M.; Mathias R. A.; Hancock D. B.; et al. (2011) Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of asthma in ethnically diverse North American populations. Nat. Genet. 43, 887–892. 10.1038/ng.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotenboer N. S.; Ketelaar M. E.; Koppelman G. H.; Nawijn M. C. (2013) Decoding asthma: translating genetic variation in IL33 and IL1RL1 into disease pathophysiology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 131, 856–865. 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamzaoui A.; Berraies A.; Kaabachi W.; Haifa M.; Ammar J.; Kamel H. (2013) Induced sputum levels of IL-33 and soluble ST2 in young asthmatic children. J. Asthma 50, 803–809. 10.3109/02770903.2013.816317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.; Helgason H.; Sulem P.; Bjornsdottir U. S.; Lim A. C.; Sveinbjornsson G.; Hasegawa H.; Brown M.; Ketchem R. R.; Gavala M.; Garrett L.; Jonasdottir A.; Jonasdottir A.; Sigurdsson A.; Magnusson O. T.; Eyjolfsson G. I.; Olafsson I.; Onundarson P. T.; Sigurdardottir O.; Gislason D.; Gislason T.; Ludviksson B. R.; Ludviksdottir D.; Boezen H. M.; Heinzmann A.; Krueger M.; Porsbjerg C.; Ahluwalia T. S.; Waage J.; Backer V.; Deichmann K. A.; Koppelman G. H.; Bonnelykke K.; Bisgaard H.; Masson G.; Thorsteinsdottir U.; Gudbjartsson D. F.; Johnston J. A.; Jonsdottir I.; Stefansson K. (2017) A rare IL33 loss-of-function mutation reduces blood eosinophil counts and protects from asthma. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006659 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saglani S.; Lui S.; Ullmann N.; Campbell G. A.; Sherburn R. T.; Mathie S. A.; Denney L.; Bossley C. J.; Oates T.; Walker S. A.; Bush A.; Lloyd C. M. (2013) IL-33 promotes airway remodeling in pediatric patients with severe steroid-resistant asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 132, 676–685. 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. Y.; Rhee C. K.; Kang J. Y.; Byun J. H.; Choi J. Y.; Kim S. J.; Kim Y. K.; Kwon S. S.; Lee S. Y. (2014) Blockade of IL-33/ST2 ameliorates airway inflammation in a murine model of allergic asthma. Exp. Lung Res. 40, 66–76. 10.3109/01902148.2013.870261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An G., Wang W., Zhang X., Huang Q., Li Q., Chen S., Du X., Corrigan C. J., Huang K., Wang W., Chen Y., and Ying S.. Combined blockade of IL-25, IL-33 and TSLP mediates amplified inhibition of airway inflammation and remodelling in a murine model of asthma. (2019) Respirology. 10.1111/resp.13711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y.; Boinapally V.; Zoltowska A.; Adner M.; Hellman L.; Nilsson G. (2015) Vaccination against IL-33 Inhibits Airway Hyperresponsiveness and Inflammation in a House Dust Mite Model of Asthma. PLoS One 10, e0133774 10.1371/journal.pone.0133774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson C. A.; Goplen N. P.; Zafar I.; Irvin C.; Good J. T. Jr.; Rollins D. R.; Gorentla B.; Liu W.; Gorska M. M.; Chu H.; Martin R. J.; Alam R. (2015) Persistence of asthma requires multiple feedback circuits involving type 2 innate lymphoid cells and IL-33. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 136, 59–68. 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter B. M.; Oliveria J. P.; Nusca G.; Smith S. G.; Tworek D.; Mitchell P. D.; Watson R. M.; Sehmi R.; Gauvreau G. M. (2016) IL-25 and IL-33 induce Type 2 inflammation in basophils from subjects with allergic asthma. Respir. Res. 17, 5. 10.1186/s12931-016-0321-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.; Donovan C.; Liu G.; Gomez H. M.; Chimankar V.; Harrison C. L.; Wiegman C. H.; Adcock I. M.; Knight D. A.; Hirota J. A.; Hansbro P. M. (2017) Animal models of COPD: What do they tell us?. Respirology 22, 21–32. 10.1111/resp.12908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. L.; Noble P. B.; Elliot J. G.; Mitchell H. W.; McFawn P. K.; Hogg J. C.; James A. L. (2016) Airflow obstruction is associated with increased smooth muscle extracellular matrix. Eur. Respir. J. 47, 1855–1857. 10.1183/13993003.01709-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers D. E.; Alexander-Brett J.; Patel A. C.; Agapov E.; Dang-Vu G.; Jin X.; Wu K.; You Y.; Alevy Y.; Girard J. P.; Stappenbeck T. S.; Patterson G. A.; Pierce R. A.; Brody S. L.; Holtzman M. J. (2013) Long-term IL-33-producing epithelial progenitor cells in chronic obstructive lung disease. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 3967–3982. 10.1172/JCI65570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearley J.; Silver J. S.; Sanden C.; Liu Z.; Berlin A. A.; White N.; Mori M.; Pham T. H.; Ward C. K.; Criner G. J.; Marchetti N.; Mustelin T.; Erjefalt J. S.; Kolbeck R.; Humbles A. A. (2015) Cigarette smoke silences innate lymphoid cell function and facilitates an exacerbated type I interleukin-33-dependent response to infection. Immunity 42, 566–579. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J.; Zhao J.; Shang J.; Li M.; Zeng Z.; Zhao J.; Wang J.; Xu Y.; Xie J. (2015) Increased IL-33 expression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Physiol Lung Cell Mol. Physiol 308, L619–627. 10.1152/ajplung.00305.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. W.; Rhee C. K.; Kim K. U.; Lee S. H.; Hwang H. G.; Kim Y. I.; Kim D. K.; Lee S. D.; Oh Y. M.; Yoon H. K. (2017) Factors associated with plasma IL-33 levels in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chronic Obstruct. Pulm. Dis. 12, 395–402. 10.2147/COPD.S120445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B. B.; Ma L. J.; Qi Y.; Zhang G. J. (2019) Correlation of IL-33 gene polymorphism with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol Sci. 23, 6277–6282. 10.26355/eurrev_201907_18449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Falco G.; Colarusso C.; Terlizzi M.; Popolo A.; Pecoraro M.; Commodo M.; Minutolo P.; Sirignano M.; D’Anna A.; Aquino R. P.; et al. (2017) Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease-Derived Circulating Cells Release IL-18 and IL-33 under Ultrafine Particulate Matter Exposure in a Caspase-1/8-Independent Manner. Front. Immunol. 8, 1415. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan C.; Starkey M. R.; Kim R. Y.; Rana B. M. J.; Barlow J. L.; Jones B.; Haw T. J.; Mono Nair P.; Budden K.; Cameron G. J. M.; Horvat J. C.; Wark P. A.; Foster P. S.; McKenzie A. N. J.; Hansbro P. M. (2019) Roles for T/B lymphocytes and ILC2s in experimental chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Leukocyte Biol. 105, 143–150. 10.1002/JLB.3AB0518-178R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa H.; Koarai A.; Shishikura Y.; Yanagisawa S.; Yamaya M.; Sugiura H.; Numakura T.; Yamada M.; Ichikawa T.; Fujino N.; et al. (2018) Oxidative stress enhances the expression of IL-33 in human airway epithelial cells. Respir. Res. 19, 52. 10.1186/s12931-018-0752-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkey M. R.; Jarnicki A. G.; Essilfie A. T.; Gellatly S. L.; Kim R. Y.; Brown A. C.; Foster P. S.; Horvat J. C.; Hansbro P. M. (2013) Murine models of infectious exacerbations of airway inflammation. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 13, 337–344. 10.1016/j.coph.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravanetti L.; Dijkhuis A.; Dekker T.; Sabogal Pineros Y. S.; Ravi A.; Dierdorp B. S.; Erjefalt J. S.; Mori M.; Pavlidis S.; Adcock I. M.; Rao N. L.; Lutter R. (2019) IL-33 drives influenza-induced asthma exacerbations by halting innate and adaptive antiviral immunity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 143, 1355–1370. 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J. P.; Werder R. B.; Simpson J.; Loh Z.; Zhang V.; Haque A.; Spann K.; Sly P. D.; Mazzone S. B.; Upham J. W.; Phipps S. (2016) Aeroallergen-induced IL-33 predisposes to respiratory virus-induced asthma by dampening antiviral immunity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 138, 1326–1337. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werder R. B.; Zhang V.; Lynch J. P.; Snape N.; Upham J. W.; Spann K.; Phipps S. (2018) Chronic IL-33 expression predisposes to virus-induced asthma exacerbations by increasing type 2 inflammation and dampening antiviral immunity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 141, 1607–1619. 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolarski B.; Kurowska-Stolarska M.; Kewin P.; Xu D.; Liew F. Y. (2010) IL-33 exacerbates eosinophil-mediated airway inflammation. J. Immunol. 185, 3472–3480. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. L.; Gutowska-Owsiak D.; Hardman C. S.; Westmoreland M.; MacKenzie T.; Cifuentes L.; Waithe D.; Lloyd-Lavery A.; Marquette A.; Londei M.; Ogg G. (2019) Proof-of-concept clinical trial of etokimab shows a key role for IL-33 in atopic dermatitis pathogenesis. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaax2945. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aax2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regeneron and Sanofi Announce Positive Topline Phase 2 Results for IL-33 Antibody in Asthma. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/regeneron-and-sanofi-announce-positive-topline-phase-2-results-for-il-33-antibody-in-asthma-300872459.html (accessed October 27, 2019).

- Etokimab. https://www.anaptysbio.com/pipeline/etokimab/ (accessed October 27, 2019).

- Proof-of-Concept Study to Assess the Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of SAR440340 (Anti-IL-33 mAb) in Patients With Moderate-to-severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03546907 (accessed October 27, 2019).