Abstract

Objective.

Exposure to community violence has disabling effects on the mental health of youth in the US, especially for African American adolescents from underserved, urban communities, fostering increased externalizing problems. The current study assessed the utility of problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidant coping strategies for reducing aggression and delinquency amidst this uncontrollable stress. It was hypothesized that greater use of avoidant strategies would most consistently reduce externalizing behaviors over time, with these effects being stronger for boys than girls.

Method.

Following confirmatory factor analyses, longitudinal moderated moderation analyses were conducted with a sample of 263 Black students from low-income, urban areas (60% female, M=11.65 years), who completed surveys in sixth, seventh, and eighth grades.

Results.

For sixth grade boys who witnessed violence, using more problem-focused strategies increased delinquency in eighth grade, whereas less use of problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidant coping increased eighth grade delinquency for girls with both indirect and direct violence exposure. Girls showed a similar pattern for aggression in seventh and eighth grade. Problem-focused coping was endorsed most frequently overall by boys and girls. Violence exposure was associated with greater use of avoidant strategies in sixth grade.

Conclusions.

These results suggest that using fewer coping strategies was detrimental for girls, while boys may require more resources to support their coping efforts. This research enhances understanding of how boys and girls adaptively cope with community violence differently, while addressing concerns with conceptualizing categories of coping to inform clinicians in these communities.

Keywords: African American, adolescent, community violence, coping, externalizing behavior

Exposure to community violence (ECV) is recognized as a major public health problem for youth in the United States (Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, 2015; Fowler, Tompsett, Braciszewski, Jacques-Tiura, & Baltes, 2009), and is particularly prevalent in low-income, urban communities, being the leading cause of death for Black youth aged 10 to 24 years (Thomas, Woodburn, Thompson, & Leff, 2011). Rates of witnessing violence for Black urban youth are 112% higher than White youth (Zimmerman & Messner, 2013), with violent victimization rates reaching up to 37% (Farrell & Bruce, 1997), and especially high rates in Chicago (Voisin, 2007). Both witnessing and victimization can have harmful effects on youth development, but with their own distinct roles in how adolescent distress manifests (Howard, Feigelman, Li, Cross, & Rachuba, 2002). Adolescents are particularly susceptible to the adverse effects of violence exposure, as this period is coupled with increased engagement in unstructured activities with decreased adult supervision (Richards, Larson, Miller, Parrella, Sims, & McCauley, 2004). For these reasons, adolescence is a critical time period during which to intervene to prevent deterioration in mental health and enhance adaptive strategies.

A plethora of research has demonstrated that all forms of ECV are more strongly linked to externalizing problems such as aggression and delinquency, relative to internalizing problems, especially among adolescents (Fowler et al., 2009; Chen, Voisin, & Jacobson, 2016). This pattern is fueled by engagement in crime and gangs as ways for youth in violent neighborhoods to counter their feelings of powerlessness and danger, such as carrying a weapon to protect themselves (Listenbee et al., 2012). When violence and aggression are consistently observed and normalized (Huesmann & Kirwil, 2007), youth become desensitized, cope less effectively, feel more hopeless, and have less confidence in their abilities (McMahon, Felix, Halpert, & Petropoulos, 2009). Aggressive beliefs thus become more acceptable over time and the perceived consequences of acting on these beliefs become less salient (Guerra, Huesmann, & Spindler, 2003). ECV has also been found to be associated with increases in delinquent behaviors, such as lying, stealing, and vandalism, and these types of behaviors can exist independent of aggression due to their own set of risk factors (e.g., deviant peers) (Weaver, Borkowski, & Whitman, 2008; Barnow, Lucht, & Freyberger, 2005).

Coping with Exposure to Community Violence

Fortunately, not all youth with ECV are destined to have externalizing problems (Copeland-Linder, Lambert, & Ialongo, 2010), and coping plays a role in protecting these youth. From a positive youth development standpoint, an adolescent is resilient when the dynamic interaction between themselves and their high-stress environment leads to positive adaptation (Lerner, Agans, Arbeit, Chase, Weiner, Schmid, & Warren, 2013). Ways of coping, understood as cognitive and behavioral efforts that are dependent upon the context of the psychological and environmental demands of the stressor, can positively or negatively affect how stress impacts an adolescent’s adjustment and future development (Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001). According to the cognitive-transactional model, the effectiveness of a coping strategy depends on the situation, specifically its level of harm and controllability (Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel-Schetter, DeLongis, & Gruen, 1986). In this way, coping strategies can be identified that provide the best fit for Black youth exposed to violence (Gaylord-Harden, Gipson, Mance, & Grant, 2008), and these strategies may be useful in therapy.

With more than 100 category systems and 400 category labels, isolating consistent patterns of coping can be very difficult (Skinner, Edge, Altman, & Sherwood, 2003). The overarching category of approach, or active coping, consists of managing the stress appraisal of a situation or behaviorally dealing with the stressor (Roth & Cohen, 1986). This typically involves techniques such as seeking guidance and taking concrete action to actively interact with the source of stress, or more covert strategies to accept the strain as real while restructuring it more positively (e.g., logically analyzing the situation, praying, admitting one’s own errors, and rehearsing alternative actions) (Blalock & Joiner, 2000). Oppositely, avoidant coping involves avoiding confrontation with the stressor and mentally blocking it out (Sandler, Tein, & West, 1994). This can include trying to forget about the problem, leaving the situation, seeking alternate rewards and activities, blaming others, releasing tension or negative emotions, and minimizing or denying the seriousness of the crisis (Blalock & Joiner, 2000). Another common and related distinction exists between problem-focused coping, or efforts to resolve the source of stress, and emotion-focused coping, or efforts to regulate emotional states related to stressful events (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

There is significant debate in the literature over which types of coping should be promoted to improve mental health. In general stress and coping literature, approach and problem-focused coping allow for instrumental action regarding distressing experiences that in turn reduces externalizing and internalizing problems (Compas et al., 2017). Historically, avoidant coping has been shown to be associated with more psychopathology (Compas et al., 2017), but it can also lessen distress and provide safety and conservation of resources amid hardship (Roth & Cohen, 1986). Roth & Cohen (1986) suggest that avoidant coping is better suited when the situation is uncontrollable, emotional resources are limited, short-term memory is overloaded, the source of stress is unknown or unresolvable, the immediate outcome is more important, and time is limited.

Recent studies appear to support these claims for avoidant coping in under-resourced communities where youth encounter many uncontrollable stressors. The appraisal of a situation as uncontrollable or unalterable (e.g., racial discrimination, ECV) is often associated with more avoidant coping processes (Tolan & Grant, 2009), which can predict to better life satisfaction and self-esteem (Utsey, Ponterotto, Reynolds, & Cancelli, 2000), as it can be very frustrating to use active strategies with little success. Youth who attempt to intervene or engage in community violence situations, such as confronting perpetrators, may place themselves at higher risk of danger (Grant et al. 2000). In general, African Americans reported behavioral avoidance to be their most frequent and recommended process of coping with ECV (Howard, Kaljee, & Jackson, 2002). Similarly, Edlynn, Gaylord-Harden, Richards, and Miller (2008) found that greater avoidant coping was associated with feeling safer, suggesting that youth make a conscious effort to avoid unsafe circumstances in their high-crime environments. Even mild substance use, a component of avoidance, has been found to benefit urban populations more so than for other groups of people (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Henry, Chung, & Hunt, 2002). In this way, the type and context of a stressor are crucial in determining how an adolescent successfully responds (Bonanno & Burton, 2013).

Coping and Externalizing Problems

Research also supports the benefits of avoidant coping for externalizing difficulties specifically. Cross-sectional moderation results suggest that for males, avoidance can be beneficial and approach, or confrontational coping, can be risky for externalizing symptoms and delinquency, respectively (Grant et al., 2000; Rosario, Salzinger, Feldman, & Ng-Mak, 2003). Similarly, Carothers, Arizaga, Carter, Taylor, and Grant (2016) showed that in a sample of urban, low-income Black and Latino youth, active coping acted as a risk factor for externalizing symptoms for girls, but led to more positive outcomes at low levels of violence exposure. Together, these studies reinforce the notion that the context of uncontrollable stress influences the effectiveness of coping strategies. However, additional research is needed on this topic that is longitudinal, incorporates child report of ECV, and delineates effects for aggression and delinquency separately in order to assert changes over time, prevent underestimation of risk, and achieve a more nuanced understanding of these effects. While preliminary evidence suggests that avoidance provides the best goodness of fit with community violence, this pattern must be replicated across samples, while examining specific strategies these youth tend to endorse.

In general, it is understood that males report more victimization and witnessing (Gladstein, Rusonis, & Heald, 1992), as well as exhibit more externalizing problems than females (e.g., Snyder & Sickmund, 1999), particularly in response to violence (Mrug & Windle, 2009). Further, the way in which males respond to violence tends to be more physically retaliatory, while females engage in more relational aggression (Lansford et al., 2012). Accordingly, it seems that males would receive increased benefit from using more avoidance and less approach coping, as this would lessen their chances for retaliation. In terms of frequency, boys have been found to use more avoidant coping than girls (Eschenbeck, Kohlmann, & Lohaus, 2007). In terms of interaction effects, Rosario et al. (2003) and Grant et al. (2000) showed protective effects of avoidant coping for externalizing problems for boys but not girls, while active coping was more detrimental for girls (Carothers et al., 2016). Although the studies examining gender effects are limited and mixed, the evidence suggests that males would benefit more from avoidance to reduce behavior problems in violent neighborhoods.

Present Study

Overall, it is evident that the relationships among violence exposure, coping, and mental health outcomes are very complicated and not yet fully understood. Several gaps exist in the coping literature, particularly regarding which form of coping functions best amidst high levels of uncontrollable stress. Few models have been tested longitudinally combining ECV, forms of avoidant and approach coping, and aggression and delinquency. Gender has been shown to frequently moderate coping outcomes, but in varied directions. Overall, the findings of this research will serve to further illuminate the kinds of coping techniques youth adopt when presented with violent stressors, and whether these strategies align with what caregivers and clinicians should encourage youth to use when living in disadvantaged, violent neighborhoods.

Coping in the current study is viewed as a moderator that affects the relationship between the predictor and outcome variables, such that the degree of positive impact of ECV on externalizing outcomes varies according to the level and type of coping. In this way, the coping strategy is either a protective or risk factor in that it reduces or enhances the effects of high levels of stress. Whereas mediation models assume that coping efforts are more situationally-based, moderation models assume that coping is more stable (Holmbeck, 1997). While this study design does maintain that the effectiveness of a coping strategy depends on the type of stressor, coping itself is more of a dispositional trait in that it becomes an engrained response to constant violence exposure in one’s environment. Previous researchers have used moderation models specifically to examine the effects of coping on the relationship between high stress and externalizing problems (Rosario et al., 2003; Carothers et al., 2016). Therefore, the current study does not seek to investigate whether coping is the mechanism that explains the relationship between ECV and externalizing difficulties, but rather does coping qualify this relationship. This effect is further elucidated with gender as a moderator of the moderation model.

The hypotheses are as follows: (1) Coping in the current sample is composed of three individual correlated factors: problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, and avoidant coping. (2) Avoidant coping will serve to most frequently mitigate the positive relationship between ECV at sixth grade and externalizing behaviors (delinquency and aggression) at seventh and eighth grade. Problem-focused and emotion-focused coping at sixth grade will serve to increase delinquency and aggression over one and two years. (3) Relative to girls, boys will demonstrate greater reduction and increase in aggression and delinquency, respectively.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data for the current study were derived from a larger 3-year longitudinal study of the predictors and outcomes of ECV in Black youth. Sixth graders were recruited from six public schools from low-income communities in Chicago during the 1999–2000 school year. These schools were selected based on their ethnic make-up as well as the crime statistics and income level of their locations within Chicago. The crime rates (e.g., murder, sexual and aggravated assault, and robbery) for these neighborhoods were two to seven times higher than average rates for the city (Chicago Police Department, 2001). The proportion of Black students at each school exceeded 90%. Thirty-one percent of parents reported being unemployed and median family income ranged from $10,000 to $20,000. Almost half (48%) of participants lived in single parent households and the average number of family members in each household was five. Eighty-three percent of parents reported having a high school degree, while ten percent indicated having a college or graduate/professional degree.

The larger sample from which this study was derived included 316 Black adolescents in sixth grade (mean age = 11.65 years; 60% females). Of the original sample, 94.78% of participants were retained at seventh grade, and 82.84% were retained in the eighth grade. The current study included 263 children (59.9% female) who completed the necessary measures in sixth grade as well as 199 parents at that same time point. In seventh grade, 244 children and 169 parents, and in eighth grade, 198 children and 184 parents completed surveys.

Student assent and parental consent were obtained from all participants prior to the start of data collection. Fifty-eight percent of families recruited via forms sent home with students agreed to participate. Trained research staff administered questionnaires to each student at their school over the course of five consecutive days during each of the three time points: 6th grade, 7th grade, and 8th grade. Parent measures were sent home with participants to be returned to the school by the participants themselves. To account for participants’ reading and comprehension levels, all survey questions were read aloud by staff. Youth were given the options of games, gift certificates, and sports equipment as compensation for participation after each time point.

Measures

Demographics.

The Parent Information Form was included to assess marital status, ethnicity, education level, family structure, income level, and employment status, while the Student Information Form included questions about the child’s age, date of birth, and gender.

Exposure to Community Violence.

ECV was assessed with an adaptation of the 25-item My Exposure to Violence Interview (EV-R; Buka, Selner-O’Hagan, Kindlon, & Earls, 1997). This measure separates ECV into victimization (12 items; e.g., “Have you been stabbed with a knife?”) and witnessing (13 items; e.g., “Have you seen someone get shot with a gun?”). Participants reported frequency of lifetime exposure to each incident on a five-point scale ranging from 0, (“never”), to 4, (“four or more times”). In the current sample, this scale yielded an alpha reliability coefficient of .71 for witnessing and .70 for victimization at sixth grade.

Coping.

Coping strategies were assessed using the 21-item Adolescent Coping Efforts Scale (Jose & Huntsinger, 2005). This measure was modified slightly in that participants indicated the most violent event they have experienced in the past year, rather than the most stressful event. Participants then rated how often they used particular coping strategies in response to this event. Each item was rated on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“a lot”). This scale has been shown to predict well-being in adolescents (Jose & Huntsinger, 2005) and Black youth (Jose, Cafasso, & D’Anna, 1994). The scale developers used exploratory factor analyses to obtain three factors of coping: problem-focused (5 items; efforts to deal with the problem itself), emotion-focused (5 items; efforts to deal with emotions related to the problem), and avoidance (6 items; efforts to ignore the problem entirely), based on conceptualization from Tobin, Holroyd, Reynolds, and Wigal (1989) and the three most common types of coping mechanisms used by adolescents according to Zeidner and Endler (1996). Two avoidance items that measured delinquent approaches to coping were removed for this study as they were confounded with the outcome measures. Factor analysis and reliability coefficients for the current sample are presented below as results.

Delinquency.

Frequency of delinquent behaviors as reported by the child was assessed using the 18 items from the Juvenile Delinquency Scale - Self-Report (JDS-SR; Tolan, 1988) unrelated to aggressive acts. This measure addresses behaviors ranging from minor delinquency (e.g., truancy, tobacco use) to illegal acts (e.g., stealing, substance use, property damage) on a six-point scale ranging from “never” (0) to “five times or more” (5). This scale yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of .87 at sixth grade, .85 at seventh grade, and .79 at eighth grade.

Frequency of delinquent behaviors as reported by the parent was assessed using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The 13-item delinquency subscale includes items such as, “Steals outside the home,” for which parents rate how true each item is within the past 6 months, using a 3-point scale ranging from “not true (as far as you know)” (0) to “very true or often true” (2). Internal reliability for the externalizing problems scale in the current sample is .75 at sixth grade, .81 at seventh grade, and .78 at eighth grade.

Aggression.

Frequency of aggressive behaviors as reported by the child was assessed using a combination of the Things I Do scale (TID) and five aggression items from the Juvenile Delinquency Scale (JDS). The nine items of the TID reflect aggressive and oppositional behavior (e.g., ‘‘How often do you push or shove others?’’) on a 4-point rating of occurrence from 0 (never) to 3 (a lot). The TID and JDS were significantly correlated for sixth grade (r = .36, p < .001), seventh grade (r = .28, p < .001), and eighth grade (r = .40, p < .001). Therefore, items from these two measures were standardized and combined to create the child-report of aggression variable. In the current sample, this combined scale yielded an alpha of .74 at sixth grade, .74 at seventh grade, and .69 at eighth grade.

Frequency of aggressive behaviors as reported by the parent were assessed using the 20-item aggressive behavior subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Parents rated how true each item is now, or was within the past 6 months, using a 3-point scale ranging from “not true (as far as you know)” (0) to “very true or often true” (2) for items such as, “Cruelty, bullying, or meanness to others.” Internal reliability for this subscale in the current sample is .88 at sixth grade, .90 at seventh grade, and .88 at eighth grade.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

No significant group differences were found between the retained sample and the group of participants lost due to attrition in parental education, annual household income, or parents’ marital status (Goldner, Peters, Richards, & Pearce, 2011) or parent reports of aggression or delinquency. However, there were significant group differences between the retained sample and those lost due to attrition for child-reported aggression and child-reported delinquency at baseline. Participants retained through eighth grade had significantly lower baseline levels of aggression and delinquency than those who dropped out. Power analyses performed using PASS Version 14 (Hintze, 2008) indicated sufficient sample size for the proposed moderation analyses. Correlations between dependent, moderator, and independent variables at each time point were performed (Table 1). Missing data was addressed by including only those participants who responded to all of the items in each particular scale. Multiple imputation was not used because data were not missing completely at random for any scale (Little, 1988).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations of Variables

| 6th Grade | M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ECV – Witnessing | 0.259 | .337 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 2. ECV – Victimization | 0.124 | .263 | .60** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 3. Problem-Focused Coping | 1.597 | 1.016 | .02 | .07 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4. Emotion-Focused Coping | 1.438 | .966 | −.01 | .07 | .75** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 5. Avoidant Coping | 1.422 | .785 | .19** | .15* | .48** | .53** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 6. Delinquency (c)a | 0.001 | .625 | .03 | .03 | .04 | .13* | .19** | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 7. Delinquency (p)a | 0.165 | .208 | −.03 | .01 | −.02 | −.03 | .03 | .06 | -- | -- | -- |

| 8. Aggression (c)a | −0.001 | .561 | .10 | .10 | .03 | .10 | .33** | .43** | .11 | -- | -- |

| 9. Aggression (p)a | 0.367 | .313 | .13 | .11 | −.01 | −.12 | .02 | .08 | .64** | .05 | -- |

| 10. Baseline Agea | 11.65 | .703 | .04 | −.05 | −.04 | −.02 | .08 | .22** | .07 | .14* | −.02 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 7th Gradeb | M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. |

|

| |||||||||||

| 6. Delinquency (c) | 0.001 | .596 | .08 | .10 | .01 | .01 | .19** | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 7. Delinquency (p) | 0.157 | .224 | .15 | .10 | −.01 | −.04 | .03 | .22** | -- | -- | -- |

| 8. Aggression (c) | 0.001 | .522 | .09 | .06 | −.02 | .03 | .19** | .45** | .17* | -- | -- |

| 9. Aggression (p) | 0.315 | .324 | .11 | .08 | −.09 | −.11 | −.06 | .20* | .72** | .27** | -- |

| 10. Baseline Agea | 11.65 | .703 | .04 | −.05 | −.04 | −.02 | .08 | .11 | .07 | −.03 | .01 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 8th Grade | M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. |

|

| |||||||||||

| 6. Delinquency (c) | −0.001 | .490 | .27** | .09 | .01 | −.07 | .07 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 7. Delinquency (p) | 0.166 | .197 | .11 | .01 | −.12 | −.17* | .01 | .31** | -- | -- | -- |

| 8. Aggression (c) | 0.001 | .535 | .21** | .12 | .06 | .03 | .14* | .53** | .26** | -- | -- |

| 9. Aggression (p) | 0.314 | .296 | .12 | .07 | −.05 | −.09 | .08 | .33** | .77** | .28** | -- |

| 10. Baseline Agea | 11.65 | .703 | .04 | −.05 | −.04 | −.02 | .08 | .23** | .22** | .02 | .11 |

Note: (c) = child report, (p) = parent report.

p<.05

p<.01

Variables examined as covariates.

Lines 1–5 are not repeated as these values did not change for those analyses performed in seventh and eighth grade.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

A first-order oblique three factor CFA was run (N = 254) using Mplus 8.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2019) software to confirm that the three factor structure of coping found in the exploratory factor analysis performed by Jose et al. (1994) is appropriate for the current sample at sixth grade. A power analysis was performed which showed 100% power at alpha level of .05 (df = 101, null RMSEA = .05, alternative RMSEA = .10) (Preacher & Coffman, 2006). Mean-and variance-adjusted weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimation was incorporated due to unequal response intervals (DiStefano & Morgan, 2014). The oblique three-factor model indicated acceptable fit of the model to the data (χ2 (74) = 167.19, RMSEA = .070, CFI = .956, TLI = .946, SRMR = .052). The resulting coping factors displayed generally acceptable reliability within each factor, except for Avoidant Coping (Problem-Focused α = .82, Emotion-Focused α = .75, Avoidant α = .57). The items included in these factors are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for Coping Categories and Individual Strategies

| Coping Strategy | Full Sample n = 263 |

Males n = 105 |

Females n = 158 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion-Focused Coping | 1.44 (0.97) | 1.37 (0.79) | 1.48 (1.07) |

| 5. I tried to tough it out until the problem went away. | .95 (1.14) | 1.13 (1.19) | .83 (1.10) |

| 12. I thought about the problem in a different way, and tried to see the good side. | 1.54 (1.21) | 1.50 (1.17) | 1.57 (1.24) |

| 14. I accepted the way things were. | 1.34 (1.18) | 1.17 (1.10) | 1.44 (1.21) |

| 20. I tried to control my feelings, calm down, and relax. | 1.74 (1.26) | 1.50 (1.24) | 1.89 (1.25) |

| 21. I laughed or joked in order to deal with the problem. | 1.33 (1.23) | 1.40 (1.17) | 1.27 (1.26) |

|

| |||

| Problem-Focused Coping | 1.60 (1.02) | 1.54 (0.86) | 1.63 (1.11) |

| 10. I talked to someone in order to feel better. | 1.69 (1.18) | 1.66 (1.17) | 1.71 (1.19) |

| 11. I asked someone to give me help to solve the problem. | 1.44 (1.20) | 1.41 (1.15) | 1.46 (1.24) |

| 13. I tried to solve the problem. | 1.71 (1.21) | 1.78 (1.15) | 1.67 (1.23) |

| 16. I tried to get more information about the problem. | 1.34 (1.24) | 1.29 (1.18) | 1.38 (1.21) |

| 17. I thought about all the things I could do to make the situation better. | 1.57 (1.19) | 1.49 (1.14) | 1.62 (1.23) |

|

| |||

| Avoidant Coping | 1.42 (0.79) | 1.44 (0.73) | 1.41 (0.82) |

| 1. I watched TV, listened to music, or played sports or games in order to feel better. | 2.05 (1.15) | 2.10 (1.06) | 2.01 (1.21) |

| 2. I ignored or tried to get away from the problem. | 1.42 (1.21) | 1.60 (1.18) | 1.31 (1.22) |

| 4. I went off by myself to get away from other people. | .98 (1.17) | 1.15 (1.20) | .85 (1.13) |

| 7. I let my feelings out: cried, yelled, looked sad, or other things. | 1.23 (1.23) | .91 (1.09) | 1.43 (1.27) |

Coping Strategy Use

In examining the rate of use of each coping strategy independently in response to violent events, it appears that “watching TV, listening to music, and playing sports or games in order to feel better,” “trying to control one’s feelings, calm down, and relax,” and “trying to solve the problem” were the most highly endorsed strategies regardless of category. In contrast, “toughing it out until the problem went away,” “going off by oneself to get away from other people,” and “letting my feelings out” were the least endorsed strategies. Problem-focused coping (M = 1.60) was endorsed significantly more than both emotion-focused coping (M = 1.44, t(265) = 3.67, p < .01) and avoidant coping (M = 1.42, t(263) = 2.65, p < .01), and these differences were consistent across males and females. Of note, males and females both included “I talked to someone in order to feel better” as one of their top three strategies. Means and standard deviations for these strategies are listed in Table 2.

There were also several significant correlations that highlight important associations between community violence exposure, coping, and externalizing behaviors (Table 1). As expected, victimization and witnessing were positively correlated with each other in sixth grade, and the four outcomes were often positively correlated with each other across time points. The three coping factors were also positively correlated with each other in sixth grade. Notably, avoidant coping in sixth grade was positively associated with witnessing violence and victimization in sixth grade, as well as child-reported delinquency and aggression across all time points except for delinquency in eighth grade. Emotion-focused coping was positively associated with child-reported delinquency at sixth grade and parent-reported delinquency at eighth grade.

Moderated Moderation Analyses

Several longitudinal linear regression moderated moderation analyses were performed using PROCESS v2.16 module for SPSS (Model 3; Hayes, 2013). The independent variable of sixth grade ECV was separated into witnessing and victimization. The dependent variables of delinquency and aggression were assessed as reported by the child and parent separately at seventh and eighth grade. The moderator variables consisted of each of the three factors of coping. Gender was entered in as the moderator of the two-way interactions. Each outcome at sixth grade, as well as coping categories at sixth grade that were not included as the moderator, were entered as control variables. The only demographic variable significantly correlated with the dependent variables was age, therefore this was also entered as a covariate. Significant and trending interaction and main effects are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Significant and Trending Main Effects, Two-way Interactions, and Three-way Interactions

| Dependent Variable (DV) | Time of DV | Independent/Moderator Variables (6th grade) | B | t | p | ΔR 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child-reported Delinquency | 8th grade | ECV witness | −2.13 | −4.08 | .001** | -- |

| n = 184 | ECV witness, Problem-Focused | 1.26 | 4.08 | .001** | -- | |

| ECV witness, Gender | 1.84 | 5.38 | .001** | -- | ||

| ECV witness, Problem-Focused, Gender | −.98 | −4.73 | .001** | .089 | ||

| ECV witness | −1.50 | −2.86 | .005* | -- | ||

| Emotion-Focused | −.34 | −1.83 | .069 | -- | ||

| ECV witness, Emotion-Focused | .98 | 2.99 | .003** | -- | ||

| ECV witness, Gender | 1.47 | 4.48 | .001** | -- | ||

| Emotion-Focused, Gender | .20 | 1.91 | .058 | -- | ||

| ECV witness, Emotion-Focused, Gender | −.85 | −4.03 | .001** | .067 | ||

| ECV witness | −2.38 | −2.88 | .004** | -- | ||

| ECV witness, Avoidant | 1.32 | 2.87 | .005** | -- | ||

| ECV witness, Gender | 2.12 | 4.22 | .001** | -- | ||

| ECV witness, Avoidant, Gender | −1.11 | −3.73 | .001** | .058 | ||

| ECV victim | −1.43 | −1.92 | .057 | -- | ||

| Problem-Focused | .27 | 1.93 | .056 | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Problem-Focused | .89 | 1.99 | .048* | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Gender | 1.13 | 2.06 | .041* | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Problem-Focused, Gendera | −.58 | −2.00 | .047* | .020 | ||

| ECV victim | −1.56 | −1.91 | .058 | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Gender | 1.50 | 2.40 | .017* | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Emotion-Focused, Gender | −.69 | −2.12 | .035* | .023 | ||

| ECV victim | −3.07 | −1.96 | .052 | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Avoidant | 1.88 | 1.93 | .056 | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Gender | 2.43 | 2.41 | .017* | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Avoidant, Gender | −1.41 | −2.27 | .024* | .026 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Parent-reported Delinquency | 7th grade | Emotion-Focused, Gender | .11 | 1.95 | .053 | -- |

| n = 122 | ECV victim, Emotion-Focused, Gendera | −.56 | −1.79 | .077 | .023 | |

| 8th grade | ECV victim, Gender | .74 | 1.98 | .050 | -- | |

| n = 126 | ECV victim, Emotion-Focused, Gender | −.56 | −2.12 | .037* | .023 | |

|

| ||||||

| Child-reported aggression | 8th grade | ECV witness | −.97 | −1.71 | .089 | -- |

| n = 172 | ECV witness, Problem-Focused | .64 | 1.91 | .058 | -- | |

| ECV witness, Gender | .88 | 2.36 | .020* | -- | ||

| ECV witness, Problem-Focused, Gender | −.48 | −2.08 | .039* | .020 | ||

| ECV witness, Gender | .66 | 1.88 | .062 | -- | ||

| ECV witness, Emotion-Focused, Gender | −.41 | −1.76 | .080 | .014 | ||

| ECV victim, Problem-Focused | .89 | 1.85 | .066 | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Problem-Focused, Gender | −.51 | −1.65 | .100 | .013 | ||

| ECV victim, Avoidant | 1.97 | 1.91 | .058 | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Gender | 2.22 | 2.06 | .041* | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Avoidant, Gender | −1.56 | −2.35 | .020* | .027 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Parent-reported Aggression | 7th grade | ECV victim | −1.63 | −2.47 | .015* | -- |

| n = 124 | ECV victim, Problem-Focused | 1.08 | 2.20 | .030* | -- | |

| ECV victim, Gender | 2.35 | 2.50 | .014* | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Problem-Focused, Gender | −.82 | −2.42 | .017* | .034 | ||

| ECV victim | −1.78 | −2.24 | .027* | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Emotion-Focused | 1.21 | 2.08 | .040* | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Gender | 1.39 | 2.13 | .034* | -- | ||

| ECV victim, Emotion-Focused, Gender | −.86 | −2.14 | .035* | .027 | ||

Note: Baseline outcomes, age, and coping categories at sixth grade that were not included as the moderator, were entered as control variables. Main effects of control variables were significant in most models but are not reported here to conserve space.

p<.05

p<.01

Conditional effects for gender were not significant.

Aggression over one year.

There was a significant three-way interaction between ECV victimization, problem-focused coping, and gender on parent-reported aggression in seventh grade. The conditional effect of victimization on parent-reported aggression was significant only for females. At very low and low levels of problem-focused coping (10th and 25th percentile), higher victimization in sixth grade predicted increased aggression in seventh grade. While not all percentiles were significant, this relationship decreased in slope as coping increased, suggesting that more problem-focused coping may be associated with less delinquency for females victimized by violence. There were no significant two or three-way interaction effects for the outcome of child-reported aggression at seventh grade.

Aggression over two years.

There was a significant three-way interaction between ECV witnessing, problem-focused coping, and gender on child-reported aggression in eighth grade. The conditional effect of witnessing on child-reported aggression was trending only for females. When females reported very low to moderate levels of problem-focused coping (10th, 25th, and 50th percentile), more witnessing in sixth grade predicted increased aggression in eighth grade. This relationship decreased in slope as coping increased, suggesting that more problem-focused coping may contribute to less aggression for females witnessing violence. The same pattern occurred for very low to low emotion-focused coping, with a trending three-way interaction.

There was also a significant three-way interaction between ECV victimization, avoidant coping, and gender on child-reported aggression in eighth grade. The conditional effect of victimization on child-reported aggression was significant only for females. At very low and low levels of avoidant coping (10th – 25th percentile), higher victimization in sixth grade predicted increased aggression in eighth grade. Of note, while the three-way interaction between victimization, problem-focused coping, and gender was only trending for males, as problem-focused coping increased from moderate to very high, the positive relationship between victimization and aggression increased in severity. There were no significant two or three-way interaction effects for the outcomes of parent-reported aggression in eighth grade.

Delinquency over one year.

There were no significant two or three-way interaction effects for the outcomes of parent-reported or child-reported delinquency in seventh grade.

Delinquency over two years.

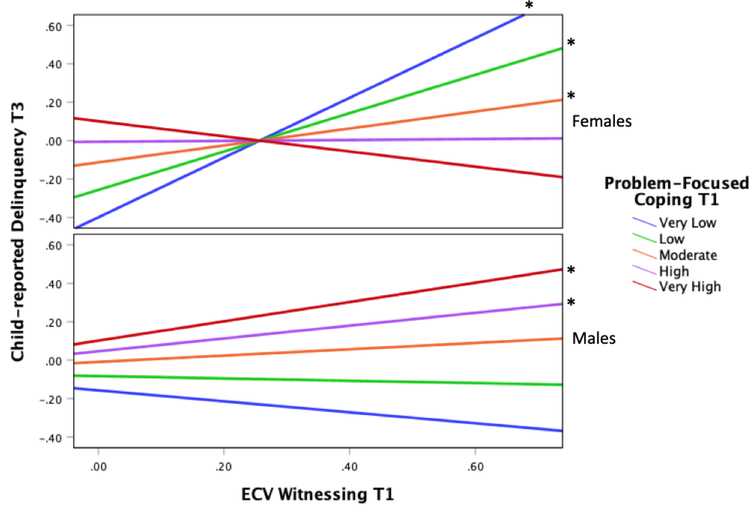

There was a significant three-way interaction between sixth grade ECV witnessing, problem-focused coping, and gender on child-reported delinquency in eighth grade. The conditional effect of witnessing on child-reported delinquency was significant for males and females. When females reported very low to moderate levels of problem-focused coping (10th – 50th percentile), more witnessing in sixth grade predicted increased delinquency in eighth grade. This relationship decreased in slope as coping increased, suggesting that again more problem-focused coping may contribute to less delinquency for females witnessing violence. Among males, at the two highest levels of problem-focused coping (75th and 90th percentile), witnessing predicted increased delinquency in eighth grade. This relationship appears to increase in slope as coping increases, suggesting that males, using less problem-focused coping, may endorse less delinquency amidst witnessing violence (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The relationship between witnessing at 6th grade and child-reported delinquency at 8th grade as moderated by problem-focused coping at 6th grade, further moderated by gender.

Note: Asterisk (*) indicates a significant percentile.

A significant three-way interaction between sixth grade ECV witnessing, emotion-focused coping, and gender on child-reported delinquency in eighth grade. The conditional effect of witnessing on child-reported delinquency was significant for females only, suggesting a similar pattern for females as found for problem-focused coping. More emotion-focused coping was associated with less delinquency for females witnessing violence. A similar pattern emerged for victimization and emotion-focused coping for females.

Similarly, a significant three-way interaction between sixth grade ECV witnessing, avoidant coping, and gender on child-reported delinquency in eighth grade showed the same pattern for females. Greater witnessing among girls at sixth grade predicted increased delinquency at eighth grade among girls using less avoidant coping, suggesting that when females who witnessed violence used more avoidance, they endorsed less delinquency. The same pattern was present for ECV victimization and avoidant coping.

Discussion

Overall, the goal of this research was to promote resiliency by illuminating the best ways for disadvantaged Black youth to handle the stress of exposure to community violence, in turn reducing maladaptive behavior. First, the current study sought to confirm that a previously validated three-factor structure of coping provided good fit for the current sample. Next, the current study aimed to utilize these categories to assess which type of coping would mitigate or exacerbate the positive relationship between exposure to community violence and externalizing outcomes. Avoidance was expected to reduce delinquency and aggression over time and problem-focused and emotion-focused strategies were expected to increase maladaptive behavior. These effects were expected to be more prevalent for males than females. Interestingly, for all coping strategies, low use of coping was harmful for females, but only high use of problem-focused coping was harmful for males. Problem-focused coping was used at the highest rates for all youth regardless of their gender. Item-level analyses reveal important nuances about which coping strategies are most prevalent in this violence-exposed sample.

Risk and Resilience Effects of Coping

Overall, no type of coping was adaptive for dealing with exposure to community violence and its effects on delinquency and aggression in males over the course of one or two years. For those males reporting higher violence exposure, only greater use of problem-focused strategies appeared to exacerbate youth-reported externalizing problems over two years. These results indicate support for the original hypothesis regarding problem-focused coping as a risk factor, such as talking to someone in order to feel better or trying to solve the problem (the two most highly endorsed problem-focused strategies). Given these findings, one might suggest that deterring boys at this age from confronting violence could be the most helpful when they are experiencing more violence in their community. Contrary to males, several significant effects appeared for females. Regardless of the type of coping, females endorsing very low to moderate use of coping strategies maintained higher levels of youth-reported delinquency over two years when indirectly and directly victimized. This effect was repeated for problem-focused coping for direct victimization and parent-reported aggression over one year, as well as avoidant and problem-focused coping for violence and child-reported aggression over two years. These relationships start to decrease as coping increases, suggesting a potential protective buffering effect of coping (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000).

Interpret with Caution: Considerations for Conceptualizing Avoidant Coping

In examining the construct of avoidant coping in the current study, several concerning issues arise that make conclusions about this factor inappropriate and misleading. First, while the three-factor structure provided acceptable fit to the data, the internal consistency of the avoidance factor was fairly poor, making this a generally unreliable construct. Second, the items included in this factor as part of the Adolescent Coping Efforts Scale (Jose & Huntsinger, 2005) do not map onto other well-supported conceptualizations of avoidant coping, such as the Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist (Ayers, Sandler, West, & Roosa, 1996). Only “trying to stay away from the problem” fits within the Avoidant Actions subscale of Avoidance, whereas none of the other items in this study constitute the more cognitive aspects of avoidance, such as Repression or Wishful Thinking. Instead, watching TV and doing other activities fits best with Distraction, and both “going off by myself” and “letting my feelings out” could be considered to be more like internalizing symptoms than specific strategies to avoid stress and do not fit within the Ayers et al. (1996) framework. Although there are many possibilities for conceptualizing avoidant coping, the limited scope and negative focus of the current factor’s four items preclude it from serving as a thorough or accurate portrayal of the main components of avoidance.

Similar problems with how to conceptualize avoidant coping using self-report scales have likely contributed to the mixed findings that exist in the present violence exposure literature. While some authors have found protective effects of avoidance amidst ECV (Grant et al., 2000; Rosario et al., 2003; Carothers et al., 2016), others have failed to provide evidence that avoidance helps reduce psychological problems (Sanchez, Lambert, & Cooley-Strickland, 2013; Rosario, Salzinger, Feldman, & Ng-Mak, 2008), and some authors posit that avoidance strategies may be less powerful in more high stress contexts due to the depletion of youth’s social support resources (Seidman, Lambert, Allen, & Aber, 2003; Gaylord-Harden et al., 2010). Therefore, these contradictions may less represent actual differences in risk and resilience, and more represent differences in the way that avoidant coping is measured. Of note, none of the aforementioned studies conceptualized coping in the exact same way, all using different scales or factor analyses, and some combined similar yet distinct constructs in their definition of avoidance (e.g., self-defense, distraction, withdrawal), which further muddles conceptualization. Researchers should aim to achieve consensus over the true meaning of avoidance, or at minimum consider how its measurement may impact interpretation of results.

Conclusions

While making sure to limit the claims that can be asserted about avoidant coping, the current study findings do not align with the original gender hypothesis and imply, instead, that girls may benefit more than boys from coping strategies in general in terms of diminishing externalizing behaviors amidst exposure to community violence, although this effect was generally not significant at the highest percentiles of coping. Girls were more at risk of behavioral problems when they did not use problem-focused, emotion-focused, or avoidant coping strategies. In other words, coping strategies were seen as detrimental when used at low levels for girls. Contrastingly, use of more problem-focused coping appears to be a risk factor for increased behavioral problems in boys, as expected.

In this sample, the frequency of coping seems to be more salient than type of coping for girls with the particular stressor of exposure to community violence. This finding may be related to coping frequency being more of a proximal moderator than type, which may be especially pertinent at this stage of youth development. It is possible that for early adolescents, there is a more generalized effect of coping due to the earlier stages of development of higher level cognitive processes. Because the brain is very actively maturing at this point, these youth are forming their own self-confidence, self-efficacy, future orientation, and executive functioning, while attempting to navigate a world full of risks and challenges (Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006). Thus, internal resources may be more directed toward general coping with a high-risk environment, leading to better outcomes as girls cope more.

Contrastingly, boys did not seem to benefit from any type of coping and were actually more at risk when they focused on solving the problem, begging the question of why trying to handle the violence-related stress did not aide these youth in reducing delinquency. Effective coping may be undermined at high levels of community violence exposure for males because the uncontrollable stress is too overwhelming for them to manage by themselves (Scarpa, Haden, & Hurley, 2006; Katz, Esparza, Carter, Grant, & Meyerson, 2012). Similarly, girls may be better able to utilize approach coping strategies to produce actual changes in behavior because of their advanced maturity and brain development compared to boys. Without proper supports, coping efforts can foster unhealthy behaviors (e.g., externalizing problems) despite good intentions, as has been shown to occur for those with advanced chronic illness (e.g., searching incessantly for a cure without success) (Cameron & Wally, 2015). Kliewer, Parrish, Taylor, Jackson, Walker, and Shivy (2006) found a rise in externalizing problems as a result of problem-focused efforts in Black adolescents coping with violence, which they explain may be connected to some youth experiencing difficulty regulating their emotions if problem-solving attempts are unsuccessful. Given that boys are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD (Xu et al., 2018), they may also be more likely to react behaviorally after failed attempts to use problem-focused coping.

Another possible explanation is that boys are simply at greater risk of delinquency and aggression in general, and especially amidst exposure to community violence, thus requiring increased external resources to supplement their coping strategies in order to reduce maladaptive behaviors (Mrug & Windle, 2009). In the current study, boys were significantly higher than girls in self-reported delinquency at sixth and seventh grade, and are more likely to get physically aggressive in general and in response to violence (Lansford et al., 2012), suggesting that they would require greater efforts to reduce such behavior to achieve the same outcome levels as girls. Coping efforts are also reinforced by caregivers who socialize youth in how to respond to stress, such as the eleven percent of caregivers who suggested using aggressive coping amidst violence in Kliewer et al. (2006). Therefore, “trying to solve the problem” could mean more aggressive behavior for boys if they are the main recipient of these suggestions. It is also possible that the construct in itself may not address coping in a way that is most appropriate for boys. For example, the increases in delinquency associated with higher use of problem-focused coping may occur if these coping techniques interfere with other types of resilience that are more valuable to boys (e.g., social support). Either way, this finding coincides with the newly defined challenge of adaptive calibration for Black boys, such that behavioral efforts to modify their stress responses to adapt to adverse conditions can be mislabeled as problematic or deviant (Gaylord-Harden, Barbarin, Tolan, & Murry, 2018). When these behaviors are acknowledged as adaptive responses instead, society can start to portray more empathy and decrease stigma.

The lack of effects supporting one particular type of coping as protective for girls or boys may signify that the measure of coping is not fully capturing the successfulness of a particular strategy or category. People first undergo an appraisal process in which they label the situation as controllable or uncontrollable, and thus cope according to that label (Folkman, 2013). Some youth may view violent incidents as something they can control, perhaps because they have family members or friends actively involved in gangs, or feel they can retaliate. Additional research should examine situation appraisal together with coping strategy endorsement in order to obtain a complete picture of the coping process. There is also an argument for coping to be construed in terms of emotion regulation, specifically the control and accommodation strategies used for adaptive self-regulation rather than problem-solving. In this way, an overarching emotion regulation construct may be more appropriate than distinguishing between orientation of efforts towards or away from the stressor (Compas et al., 2017).

Like coping frequency, child-reported delinquency may be the most proximal outcome of ECV and coping, as it had the greatest number of significant effects. Delinquency may be the easiest to target by simply changing one’s amount of coping with violence, especially since aggression is so consistently modeled and engrained in these at-risk environments. Very similar patterns emerged for both witnessing violence and being personally violently victimized, suggesting that these coping effects may not vary according to whether the violence exposure is direct or indirect, contrary to past literature (Hammack, Richards, Luo, Edlynn, & Roy, 2004). The emergence of more significant results over the course of two years suggests that coping may have more of an impact over time (Tolan, Guerra, & Montaini-Klovdahl, 1997). As noted above, undergoing puberty and brain development typical of early adolescence may reduce the capacity to integrate these strategies. Community violence is so all-encompassing that youth could take longer to achieve demonstrable change in response.

Coping Strategies for High-Risk Youth

Avoidant coping was significantly positively associated with both types of violence exposure and externalizing problems, but it is likely that these correlations are driven by the presence of distraction and internalizing symptoms in this factor (Tolan et al., 2002). In contrast with the ECV coping literature, problem-focused coping was endorsed most frequently in youth’s response to violent events, which suggests that youth adopted more traditional approaches used to counter controllable stress (Compas et al., 2017). Some violent experiences may not be so severe that they warrant or promote complete removal from the stress, therefore this should not become an automatic assumption from clinicians. Deeper analysis of the actual violent events reported would aid in interpreting this main effect.

Of the strategies endorsed, distraction through doing unrelated activities (e.g., watching TV) was interestingly the favorite coping strategy across genders. This provides some evidence that youth may prefer not to immediately attempt to manage stress through one of their other preferred strategies (i.e., trying to control their feelings, trying to solve the problem, or talking to someone), suggesting ways therapists can engage effectively with buy-in from clients. Distraction coping has been shown to withstand negative mental health effects during initial stressful periods (Sandler et al., 1994), and failed to elevate problem behaviors and post-traumatic stress amidst violence (Boxer, Sloan-Power, Mercado, & Schappell, 2012). Toughing it out, getting away from other people, and letting feelings out were the least preferred, which shows a trend towards youth’s attempts to regulate emotion and be near others for positive support. Clinicians and program leaders should take these frequencies into consideration before jumping into a violence intervention, in that they might be more successful in supporting the youth’s coping efforts by giving youth enough space to relax and build rapport first, but not so much space that they are not present when the child is ready to address the problem.

Strengths and Limitations

This research was performed utilizing a fairly large sample of low-income Black youth, providing increased power to detect effects and increased potential for generalizability to other youth in this ethnic group. This particular study builds upon the literature on how to conceptualize coping and its role in helping or hindering youth exposed to community violence. The incorporation of parent and child reports, longitudinal data, and distinct community violence and externalizing variables add value to the ECV coping literature. The inclusion of gender effects accounts for differences between the groups that may occur due to differing developmental trajectories and social influences. Overall, this study makes a significant contribution to the knowledge base for how coping affects how youth interact with their larger community environment, or exosystem, and how coping conceptualizations can vary widely.

Despite the many strengths of this study, limitations exist. First, those participants who dropped out of the study were inherently higher in delinquency and aggression as reported by the children themselves, therefore more likely to be non-compliant. The preceding results may not reflect the full range of outcomes that could occur for such youth, and do not assess coping responses to many violent events at once. Additionally, surveys were only examined at sixth grade for ECV and coping, and only once each of the three years for outcomes, thus this study does not account for more subtle changes within each year. Coping is a very nuanced concept constantly adjusting to the nature of the stressor, thus if the stressor changes in intensity, the type of coping changes, or something else major happens, these factors could have varying effects on coping depending on when a child is surveyed. Lastly, this study’s dependence on coping categories can preclude important distinctions from being made if these categories are not exhaustive or properly calibrated for the youth being surveyed, as was especially detrimental for making conclusions about avoidant coping.

Future Directions and Implications

Future studies should continue to utilize other meaningful methods for conceptualizing coping, especially avoidant coping, so that more fine-grained interpretations can be made for use in prevention and intervention programs. These methods might entail adopting the Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist or mirroring its factors (Ayers et al., 1996), using emotion regulation strategies in place of traditional coping strategies (Compas et al., 2017), perceiving coping as a continuum as opposed to categories, using person-centered statistical approaches, or locating suppressor effects of all coping types together (Gaylord-Harden et al., 2010). A wider age range would be beneficial, as well, since youth delinquency and aggression can appear differently in early adolescence compared to middle and late adolescence. Additional research is warranted in examining children’s qualitative perspectives regarding primary and secondary appraisal to address how they interpret a violent event and subsequently choose a particular coping strategy (Folkman, 2013), and why they revert to certain strategies more than others so as to enhance future therapeutic alliances.

First and foremost, this research reveals further complexities in coping with community violence and shows how crucial it is to advance our knowledge of what makes youth resilient or vulnerable from their own perspective. The results outlined in this study speak to the utility of viewing coping within the context of the cognitive-transactional model, in that how youth allocate their emotional and behavioral resources and successfully cope with violence can vary depending on their own individual or group factors. The current study revealed greater youth endorsement of distraction along with problem-solving strategies, generalized benefits of coping for girls, difficulty with problem-focused coping for boys as they adapt to adversity, and delinquency as a salient proximal target of coping. These factors are particularly useful to understand when there is an ethnic or cognitive mismatch between a therapist and client, and the therapist requires additional context in order to better treat their client (Zane et al., 2005). It is the ultimate hope that clinicians in intervention or prevention programs take advantage of these findings when fostering youth resilience and engagement in coping activities in exceptional contexts such as urban, low-income Black communities.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Grant R01–MH57938 from the National Institute of Mental Health awarded to Maryse H. Richards.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment Burlington, VT: ASEBA. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers T, Sandier I, West S, & Roosa M (1996). A dispositional and situational assessment of children’s coping: Testing alternative models of coping. Jour of Personality,64,923–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnow S, Lucht M, & Freyberger HJ (2005). Correlates of aggressive and delinquent conduct problems in adolescence. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression, 31(1), 24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ, & Choudhury S (2006). Development of the adolescent brain: implications for executive function and social cognition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3‐4), 296–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blalock JA, & Joiner TE Jr (2000). Interaction of cognitive avoidance coping and stress in predicting depression/anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24(1), 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, & Burton CL (2013). Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspectives on Psych. Sci, 8(6), 591–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Sloan-Power E, Mercado I, & Schappell A (2012). Coping with stress, coping with violence: Links to mental health outcomes among at-risk youth. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34(3), 405–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron LD, & Wally CM (2015). Chronic illness, psychosocial coping with. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2(3), 549–554. [Google Scholar]

- Carothers KJ, Arizaga JA, Carter JS, Taylor J, & Grant KE (2016). The costs and benefits of active coping for adolescents residing in urban poverty. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(7), 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Voisin DR, & Jacobson KC (2016). Community violence exposure and adolescent delinquency: Examining a spectrum of promotive factors. Youth & Society, 48(1), 33–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, & Wadsworth ME (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Jaser SS, Bettis AH, Watson KH, Gruhn MA, Dunbar JP, … & Thigpen JC(2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(9), 939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland-Linder N, Lambert SF, & Ialongo NS (2010). Community violence, protective factors, and adolescent mental health: A profile analysis. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(2), 176–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano C, & Morgan GB (2014). A comparison of diagonal weighted least squares robust estimation techniques for ordinal data. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 425–438. [Google Scholar]

- Edlynn ES, Gaylord-Harden NK, Richards MH, & Miller SA (2008). African American inner-city youth exposed to violence: Coping skills as a moderator for anxiety. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78(2), 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenbeck H, Kohlmann CW, & Lohaus A (2007). Gender differences in coping strategies in children and adolescents. Journal of individual differences, 28(1), 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD & Bruce SE (1997). Impact of exposure to community violence on violent behavior and emotional distress among urban adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 26(1), 2–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, & Hamby SL (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the national survey of children’s exposure to violence. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(8), 746–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S (2013). Stress: appraisal and coping. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine (pp. 1913–1915). Springer: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, & Gruen RJ (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(5), 992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler PJ, Tompsett CJ, Braciszewski JM, Jacques-Tiura AJ, & Baltes BB (2009). Community violence: A meta-analysis on effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Development and Psychopathology, 21(1), 227–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden NK, Barbarin O, Tolan PH, & Murry VM (2018). Understanding development of African American boys and young men: Moving from risks to positive youth development. American Psychologist, 73(6), 753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden NK, Cunningham JA, Holmbeck GN, & Grant KE (2010). Suppressor effects in coping research with African American adolescents from low-income communities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(6), 843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden NK, Gipson P, Mance G, & Grant KE (2008). Coping patterns of African American adolescents: A confirmatory factor analysis and cluster analysis of the Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist. Psychological Assessment, 20(1), 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldner J, Peters TL, Richards MH, & Pearce S (2011). Exposure to community violence and protective and risky contexts among low income urban African American adolescents: A prospective study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(2), 174–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstein J, Rusonis EJS, & Heald FP (1992). A comparison of inner-city and upper-middle class youths’ exposure to violence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 13(4), 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, O’Koon JH, Davis TH, Roache NA, Poindexter LM, Armstrong ML, … & McIntosh JM (2000). Protective factors affecting low-income urban African American youth exposed to stress. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 20(4), 388–417. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Huesmann L, & Spindler A (2003). Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children. Child Development, 74(5), 1561–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hintze J (2008). PASS 2008 NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah. (Sample size and power software). [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN (1997). Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(4), 599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard D, Feigelman S, Li X, Cross S, & Rachuba L (2002). The relationship among violence victimization, witnessing violence, and youth distress. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31(6), 455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE, Kaljee L, & Jackson L (2002). Urban African American adolescents’ perceptions of community violence. American Journal of Health Behavior, 26(1), 56–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR, & Kirwil L (2007). Why observing violence increases the risk of violent behavior by the observer. The Cambridge Handbook of Violent Beh. and Agg, 545–570.

- Jose PE, Cafasso LL, & D’Anna CA (1994). Ethnic group differences in children’s coping strategies. Sociological Studies of Children, 6, 25–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jose P & Huntsinger C (2005). Moderation and mediation effects of coping by Chinese American and European American adolescents. Journal of Genetic Psych, 166, 16–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz BN, Esparza P, Carter JS, Grant KE, & Meyerson DA (2012). Intervening processes in the relationship between neighborhood characteristics and psychological symptoms in urban youth. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 32(5), 650–680. [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Parrish KA, Taylor KW, Jackson K, Walker JM, & Shivy VA (2006). Socialization of coping with community violence: Influences of caregiver coaching, modeling, and family context. Child Development, 77(3), 605–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Skinner AT, Sorbring E, Giunta LD, Deater‐Deckard K, Dodge KA, … & Uribe Tirado LM (2012). Boys’ and girls’ relational and physical aggression in nine countries. Aggressive Behavior, 38(4), 298–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, Agans JP, Arbeit MR, Chase PA, Weiner MB, Schmid KL, & Warren AEA (2013). Resilience and positive youth development: A relational developmental systems model. In Goldstein S & Brooks RB (Eds.) Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 293–308). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Listenbee RL, Torre J, Boyle G, Cooper SW, Deer S, Durfee DT, … Taguba A (2012). Report of the Attorney General’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence. Defending Childhood Initiative Retrieved from http://www.justice.gov/defendingchildhood/cev-rpt-full.pdf

- Little RJ (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, & Becker B (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon SD, Felix ED, Halpert JA, & Petropoulos LA (2009). Community violence exposure and aggression among urban adolescents: Testing a cognitive mediator model. Journal of Community Psychology, 37(7), 895–910. [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, & Windle M (2009). Mediators of neighborhood influences on externalizing behavior in preadolescent children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(2), 265–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2019). Mplus User’s Guide Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Coffman DL (2006). Computing power and minimum sample size for RMSEA Available from http://quantpsy.org.

- Richards MH, Larson RW, Miller BV, Parrella DP, Sims B, & McCauley C (2004). Risky and protective contexts and exposure to violence in urban African American young adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33(1), 145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Salzinger S, Feldman RS, & Ng‐Mak DS (2003). Community violence exposure and delinquent behaviors among youth: The moderating role of coping. Journal of Community Psychology, 31(5), 489–512. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Salzinger S, Feldman RS, & Ng-Mak DS (2008). Intervening processes between youths’ exposure to community violence and internalizing symptoms over time: The roles of social support and coping. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1–2), 43–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, & Cohen LJ (1986). Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American Psychologist, 41(7), 813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez YM, Lambert SF, & Cooley-Strickland M (2013). Adverse life events, coping and internalizing and externalizing behaviors in urban African American youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(1), 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Tein JY, & West SG (1994). Coping, stress, and the psychological symptoms of children of divorce: A cross‐sectional and longitudinal study. Child Development, 65(6), 1744–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A, Haden SC, & Hurley J (2006). Community violence victimization and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder: The moderating effects of coping and social support. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(4), 446–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman E, Lambert B, Allen L, & Aber L (2003). Urban adolescents’ transition to junior high school and protective family transactions. Journal of Early Adol, 23, 166–193. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Edge K, Altman J, & Sherwood H (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: a review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HN, & Sickmund M (1999). Juvenile offenders and victims: 1999 national report Washington, DC: National Center for Juvenile Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DE, Woodburn EM, Thompson CI, & Leff SS (2011). Contemporary interventions to prevent and reduce community violence among African American youth. In Handbook of African American Health (pp. 113–127). Springer; New York. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin DL, Holroyd KA, Reynolds R, & Wigal J (1989). The hierarchical factor structure of the Coping Strategies Inventory. Cognitive therapy and research, 13(4), 343–361. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan P (1988). Socioeconomic, family, and social stress correlates of adolescent antisocial and delinquent behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 16(3), 317–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman–Smith D, Henry D, Chung KS, & Hunt M (2002). The relation of patterns of coping of inner–city youth to psychopathology symptoms. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12(4), 423–449. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Guerra NG, & Montaini-Klovdahl LR (1997). Staying out of harm’s way. In Handbook of Children’s Coping (pp. 453–479). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan P & Grant K (2009). How social and cultural contexts shape the development of coping: Youth in the inner city as an example. New Dir. for Child and Adol. Dev, 124, 61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Ponterotto JG, Reynolds AL, & Cancelli AA (2000). Racial discrimination, coping, life satisfaction, and self-esteem among African Americans. Journal of Counseling and Development, 78(1), 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DR (2007). The effects of family and community violence exposure among youth: Recommendations for practice and policy. Journal of Social Work Education, 43, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver CM, Borkowski JG, & Whitman TL (2008). Violence breeds violence: Childhood exposure and adolescent conduct problems. Jour of Comm Psych, 36, 96–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Strathearn L, Liu B, Yang B, & Bao W (2018). Twenty-year trends in diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among US children and adolescents, 1997–2016. JAMA Network Open, 1(4), e181471–e181471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zane N, Sue S, Chang J, Huang L, Huang J, Lowe S, … & Lee E (2005). Beyond ethnic match: Effects of client–therapist cognitive match in problem perception, coping orientation, and therapy goals on treatment outcomes. Journal of Community Psychology, 33(5), 569–585. [Google Scholar]

- Zeidner M, & Endler NS (Eds.). (1996). Handbook of coping: Theory, research, applications (Vol. 195). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman GM, & Messner SF (2013). Individual, family background, and contextual explanations of racial and ethnic disparities in youths’ exposure to violence. American Journal of Public Health, 103(3), 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]