SUMMARY

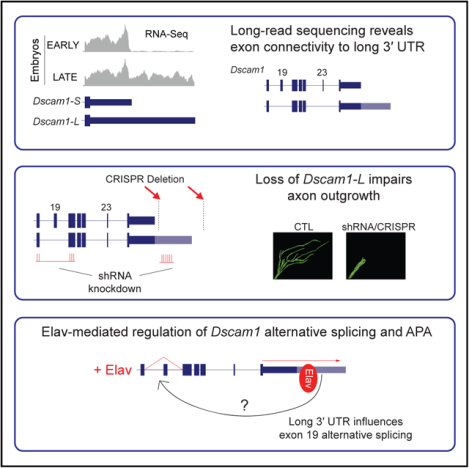

Many metazoan genes express alternative long 3′ UTR isoforms in the nervous system, but their functions remain largely unclear. In Drosophila melanogaster, the Dscam1 gene generates short and long (Dscam1-L) 3′ UTR isoforms because of alternative polyadenylation (APA). Here, we found that the RNA-binding protein Embryonic Lethal Abnormal Visual System (Elav) impacts Dscam1 biogenesis at two levels, including regulation of long 3′ UTR biogenesis and skipping of an upstream exon (exon 19). MinION long-read sequencing confirmed the connectivity of this alternative splicing event to the long 3′ UTR. Knockdown or CRISPR deletion of Dscam1-L impaired axon outgrowth in Drosophila. The Dscam1 long 3′ UTR was found to be required for correct Elav-mediated skipping of exon 19. Elav thus co-regulates APA and alternative splicing to generate specific Dscam1 transcripts that are essential for neural development. This coupling of APA to alternative splicing might represent a new class of regulated RNA processing.

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Like most metazoan genes, Dscam1 expresses alternative short and long 3′ UTR mRNAs. Zhang et al. find that loss of Dscam1 long 3′ UTR transcripts impairs axon outgrowth in Drosophila. Long-read sequencing reveals that these long 3′ UTR mRNAs preferentially skip an upstream exon, altering Dscam1 amino acid sequence.

INTRODUCTION

Alternative polyadenylation (APA) is a key event in RNA processing that most commonly results in mRNAs with different length 3′ UTRs (tandem APA or 3′ UTR APA) (Miura et al., 2014; Tian and Manley, 2017). Well over half of genes in Drosophila, zebrafish, mice, and humans undergo APA (Hoque et al., 2013; Lianoglou et al., 2013; Sanfilippo et al., 2017; Smibert et al., 2012; Ulitsky et al., 2012). APA generates alternative length 3′ UTRs depending on tissue and cell type, with testis generating short 3′ UTR isoforms and brain tissue generating extended or long 3′ UTR isoforms (Miura et al., 2013; Ramskӧld et al., 2009; Sanfilippo et al., 2017; Smibert et al., 2012).

Previous RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) studies have uncovered that 3′ UTR extension or lengthening is a pervasive event in metazoan nervous systems. In Drosophila, hundreds of genes have been found to express alternative long 3′ UTR isoforms in neural tissues (Brown et al., 2014; Smibert et al., 2012). In mice and humans, thousands of genes were found to express previously unannotated long 3′ UTR isoforms (Miura et al., 2013). Long 3′ UTR isoforms tend to be associated with lower molecular weight polysomal fractions than their shorter counterparts, suggesting they are less efficiently translated (Blair et al., 2017). Elements within 3′ UTRs are also important for localization to dendrites and axons (Cioni et al., 2018; Glock et al., 2017).

Alternative long 3′ UTRs harbor increased real estate compared with their short counterparts for regulation by RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and microRNAs that can control mRNA stability, localization, and translation (Miura et al., 2014). Several long 3′ UTR isoforms have been previously implicated in neural development. An alternative long 3′ UTR isoform of Impa1 directs mRNA localization to axons, and its knockdown by small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) leads to axonal degeneration in rat sympathetic neurons (Andreassi et al., 2010). Other studies have used indirect methods to abrogate alternative 3′ UTR isoforms. For instance, to study the function of long BDNF transcripts in mice, a SV40 polyadenylation (polyA) site was inserted downstream of the BDNF proximal polyA site to inhibit expression of the long 3′ UTR (An et al., 2008). These mice had impaired synaptic transmission and exhibited hyperphagic obesity (An et al., 2008; Liao et al., 2012). More recently, the function of the long 3′ UTR isoform of CamKII was studied indirectly by generating a CamKII knockout that continued to express short 3′ UTR CamKII via maternal contribution (Kuklinetal., 2017).These flies displayed impaired synaptic plasticity, which was at least partially attributed to impaired local translation of CamKII.

The neuronal RBP embryonic lethal abnormal visual system (Elav) binds to U-rich elements to regulate alternative splicing and APA (Soller and White, 2003; Zaharieva et al., 2015). Elav has been proposed to compete with the cleavage and polyadenylation machinery for the downstream U-rich element (DUE) found at polyA sites, thus promoting long 3′ UTR biogenesis (Hilgers et al., 2012). This mechanism has been described for other RBPs in regulating APA (Gawande et al., 2006; Mansfield and Keene, 2012; Zhu et al., 2007). In addition, a role for Elav binding to gene promoters has also been implicated in the mechanism of 3′ UTR lengthening (Oktaba et al., 2015).

The Drosophila Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule (Dscam1) gene encodes a transmembrane receptor that plays an important role in neurite self-avoidance, axon guidance, and maintenance of neural circuits (Schmucker and Chen, 2009; Zipursky et al., 2006). Dscam1 expresses two 3′ UTR variants, a short 3′ UTR of ~1.1 kb (Dscam1-S) and a long 3′ UTR variant of ~2.8 kb (Dscam1-L) (Smibert et al., 2012). Dscam1 is appreciated as the most extensively alternatively spliced gene known in nature, with the potential to generate over 38,000 mRNA protein isoforms (Brown et al., 2014; Schmucker et al., 2000). With advances in long-read sequencing it has become possible to identify mRNA alternative exon connectivity in an unambiguous way. MinION long-read RNA-seq of the three Dscam1 hypervariable exon clusters 4, 6, and 9, which are important for dendritic self-avoidance (Hughes et al., 2007; Matthews et al., 2007), identified at least 7,874 unique splice-forms (Bolisetty et al., 2015). In addition to these clusters, alternative splicing of exons 19 and 23 generates endodomain diversity (Yu et al., 2009). Suppression of Dscam1 mRNAs lacking exons 19 or 23 was previously found to inhibit postembryonic neuronal morphogenesis, demonstrating the crucial importance of skipping these exons for Dscam1 function in neurons (Yu et al., 2009). Despite their importance, the factors that regulate alternative splicing of exons 19 and 23 are unknown.

In this study, we set out to determine the functional impact of long Dscam1 3′ UTR loss on neural development. We found that Elav promotes Dscam1 long 3′ UTR biogenesis, which restricts its expression to neurons. We specifically knocked down Dscam1-L by short hairpin RNA (shRNA) in neurons and found that this resulted in severely compromised locomotion and adult lethality. Overall Dscam1 protein levels remained unchanged in the knockdown condition. This prompted us to investigate upstream splicing events that coincide with the expression of the long 3′ UTR. We identified that Dscam1-L transcripts preferentially exclude exon 19. Knockdown of Dscam1-L severely impaired mushroom body (MB) bifurcation and suppressed axon outgrowth of small ventral lateral neurons (sLNvs). The importance of Dscam1-L for axon outgrowth was confirmed in flies harboring a CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of the long 3′ UTR region. We found that the skipping of exon 19 is mediated by Elav, and this skipping event is deregulated upon loss of the long 3′ UTR. In summary, we have found that Elav regulates Dscam1 at both the levels of alternative splicing and APA, and the resulting transcripts that bear the long 3′ UTR and lack exon 19 are required for axon outgrowth.

RESULTS

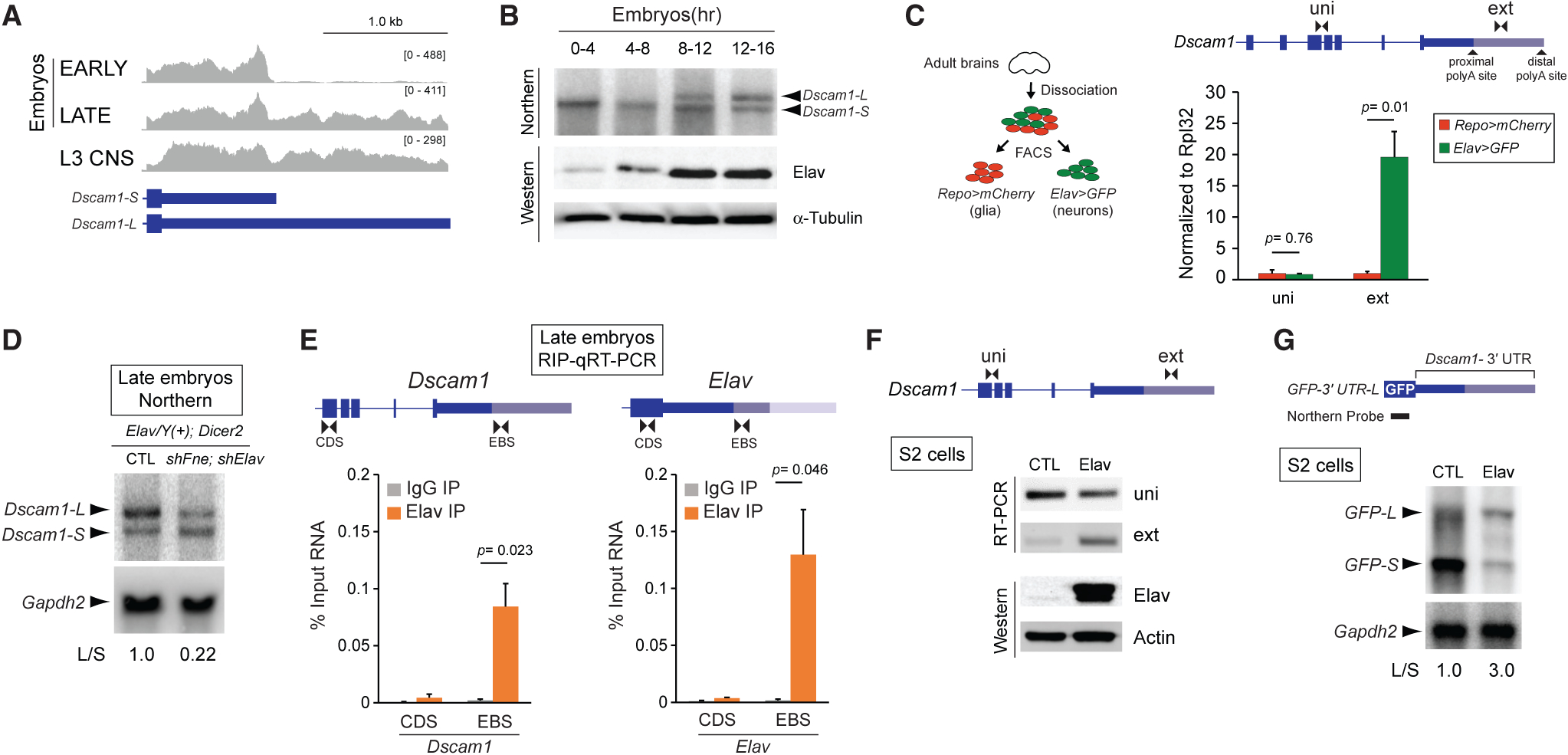

Elav Regulates Biogenesis of Dscam1-L

Dscam1 expresses two 3′ UTR variants, a short 3′ UTR of ~1.1 kb (Dscam1-S) and a long 3′ UTR variant of ~2.8 kb (Dscam1-L). We sought to determine the mechanism that regulates biogenesis of Dscam1-L. Visual examination of publicly available RNA-seq tracks (see STAR Methods) using Integrated Genomics Viewer (Thorvaldsdόttir et al., 2013) suggested that the Dscam1 long 3′ UTR isoform is not expressed in early-stage embryos, but appears in late-stage embryos, which coincides with the development of the nervous system. The long 3′ UTR is also expressed in the larval stage 3 (L3) CNS (Figure 1A). To confirm these trends, we monitored Dscam1 3′ UTR isoforms by northern analysis using a probe hybridizing to the constitutively expressed Dscam1 exon 11. We found that late-stage embryos (8–12 h, 12–16 h after egg laying) exhibited expression of Dscam1-L, whereas early-stage embryos did not (0–4 h, 4–8 h) (Figure 1B). There have been reports that 3′ UTRs can be cleaved and form stable fragments separated from their upstream protein-coding regions (Kocabas et al., 2015; Malka et al., 2017). Northern blot using a probe targeting the 3′ UTR downstream of the stop codon did not reveal evidence for such isolated 3′ UTRs, although this does not preclude their existence (Figure S1). Western analysis showed that late-stage embryos express enhanced levels of Elav protein compared with early stages, which coincides with the expression of Dscam1-L (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Elav Regulates Dscam1 Long 3′ UTR Biogenesis.

(A) RNA-seq tracks demonstrate extension of Dscam1 3′ UTR is absent in early (6–8 h after egg laying) embryos, but is induced in late embryos (16–18 h) and L3 larval CNS.

(B) Northern analysis shows expression of Dscam1 long 3′ UTR isoform (Dscam1-L) in late-stage embryos, whereas the short 3′ UTR isoform (Dscam1-S) is expressed throughout development (top panel). Northern probe was designed to target common Dscam1 exon 11. Western blot shows increased expression of Elav in the later embryonic time points. α-Tubulin is shown as a loading control.

(C) FACS analysis of adult brains from Repo-positive cells (glia) and Elav-positive cells (neurons). qRT-PCR detection of both the short and long Dscam1 transcripts using uni primers shows similar levels between Repo- and Elav-positive cells. Detection using ext primers demonstrates that Dscam1-L is highly enriched in Elav-positive cells. Error bars represent SEM. n = 3. p value reflects two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(D) Northern analysis of 16–20 h embryos shows that knockdown of Elav and the related protein FNE by shRNAs in neurons resulted in a reduction in the ratio of Dscam1-L to Dscam1-S (L/S). Elav represents Elav-GAL4, and Dicer2 represents UAS-Dicer2. Dscam1 northern probe targets common exon 11. Gapdh2 northern is shown as a loading control.

(E) RIP-qRT-PCR experiments demonstrate binding of Elav downstream of the Dscam1 proximal polyA site (left), and as a positive control, binding of Elav downstream of the Elav proximal polyA site (right). RIP was performed using rat and mouse anti-Elav antibodies from 12–16 h embryos. Primers were designed to detect a region in the CDS or a region immediately downstream of the proximal polyA site (EBS). Error bars represent SEM of four separate immunoprecipitation reactions on independently prepared nuclei. n = 4. p value reflects two-tailed paired Student’s t test.

(F) RT-PCR experiments show that transfection of S2 cells with Elav induces endogenous expression of Dscam1-L (detected using ext primers). Anti-Elav western blot confirms Elav overexpression. Actin is shown as a loading control.

(G) Northern blot detecting GFP for S2 cells transfected with a GFP reporter construct harboring the Dscam1 long 3′ UTR (GFP-3′ UTR-L). Overexpression of Elav resulted in reduced short and increased long transcripts from the reporter. Gapdh2 northern is shown as a loading control.

L/S, ratio of long to short 3′ UTR transcripts. See also Figures S1 and S2.

We hypothesized that neurons selectively express Dscam1-L given the known neuronal enrichment of Elav and its low or undetectable expression in glia (Berger et al., 2007). To test this, we performed fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) experiments. Using the LexA system (Pfeiffer et al., 2010), we generated flies that simultaneously express mCherry from a glial-specific driver (repo-Gal4) and GFP from a neuron-specific driver (elav-LexA) (Figure 1C). After FACS of dissected adult brains of these animals, qRT-PCR was performed using primers to detect all Dscam1 transcripts (“uni”) or Dscam1-L transcripts (extension “ext”). Dscam1-L was found to be ~20-fold higher in the sorted neurons versus glia, whereas total Dscam1 mRNA levels were unchanged between neurons and glia (Figure 1C). These data show that Dscam1-L expression is more abundant in, if not exclusive to, Elav-positive neurons.

To determine whether Elav regulates biogenesis of Dscam1-L in vivo, we performed shRNA knockdown of elav and the related gene found in neurons (fne) in neurons, and monitored Dscam1 3′ UTR mRNA isoforms by northern analysis. Elav and FNE have overlapping roles (Zaharieva et al., 2015), and we found that knocking down both genes together was lethal in the larval stage (data not shown). Elav/FNE knockdown in late-stage embryos (16–20 h) resulted in a marked decrease in the ratio of Dscam1-L/Dscam1-S. (Figure 1D).

Elav Binds the Dscam1 Proximal PolyA Site

Elav has been proposed to compete with the polyadenylation machinery for access to U-rich regions downstream of proximal polyA sites, thus promoting selection of distal polyA sites (Hilgers et al., 2012). Analysis of Dscam1 3′ UTR sequence revealed the presence of a U-rich element downstream of the proximal cleavage site. To test whether Elav binds to this motif, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) and found that Elav bound to a U-rich region downstream of the proximal polyA site in a manner dependent on the integrity of U stretches (Figure S2). To determine whether Elav binds to regions near the proximal polyA site in vivo, we performed RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays on RNA fragments from sonicated 12–16 h embryo nuclear extracts. Ribonucleoprotein complexes containing Elav were purified using anti-Elav antibodies followed by qRT-PCR. Elav is known to regulate APA of its own gene (Hilgers et al., 2012). Thus, as a positive control, we tested for Elav binding to an established Elav binding site (EBS) near the proximal polyA site of the elav mRNA. By qRT-PCR, this region was found to bind Elav (EBS), but not control coding sequence (CDS) (Figure 1E). Similarly, Elav binding was observed at the Dscam1 proximal polyA site (EBS), but not the CDS. Thus, Elav binds at or near the proximal polyA site of Dscam1 in vivo.

The Schneider 2 (S2) Drosophila cell line expresses very low levels of Elav protein and Dscam1-L. Elav overexpression by transient transfection led to an expected increase in endogenous Dscam1-L expression (Figure 1F). To determine whether Elav could regulate Dscam1 long 3′ UTR biogenesis solely via elements in the 3′ UTR, we generated a reporter plasmid containing the Dscam1 long 3′ UTR sequence, plus U-rich sequence downstream of the distal polyA site, and sub-cloned this downstream of a GFP reporter (GFP-3′ UTR-L). Cells transfected with GFP-3′ UTR-L predominantly expressed the short 3′ UTR isoform and only low levels of the long 3′ UTR isoform as measured by northern blot using a probe against GFP. Overexpression of Elav increased the ratio of long/short reporter mRNA by 3-fold (Figure 1G). Thus, sequences located in Dscam1 3′ UTR are sufficient for Elav to promote long 3′ UTR expression.

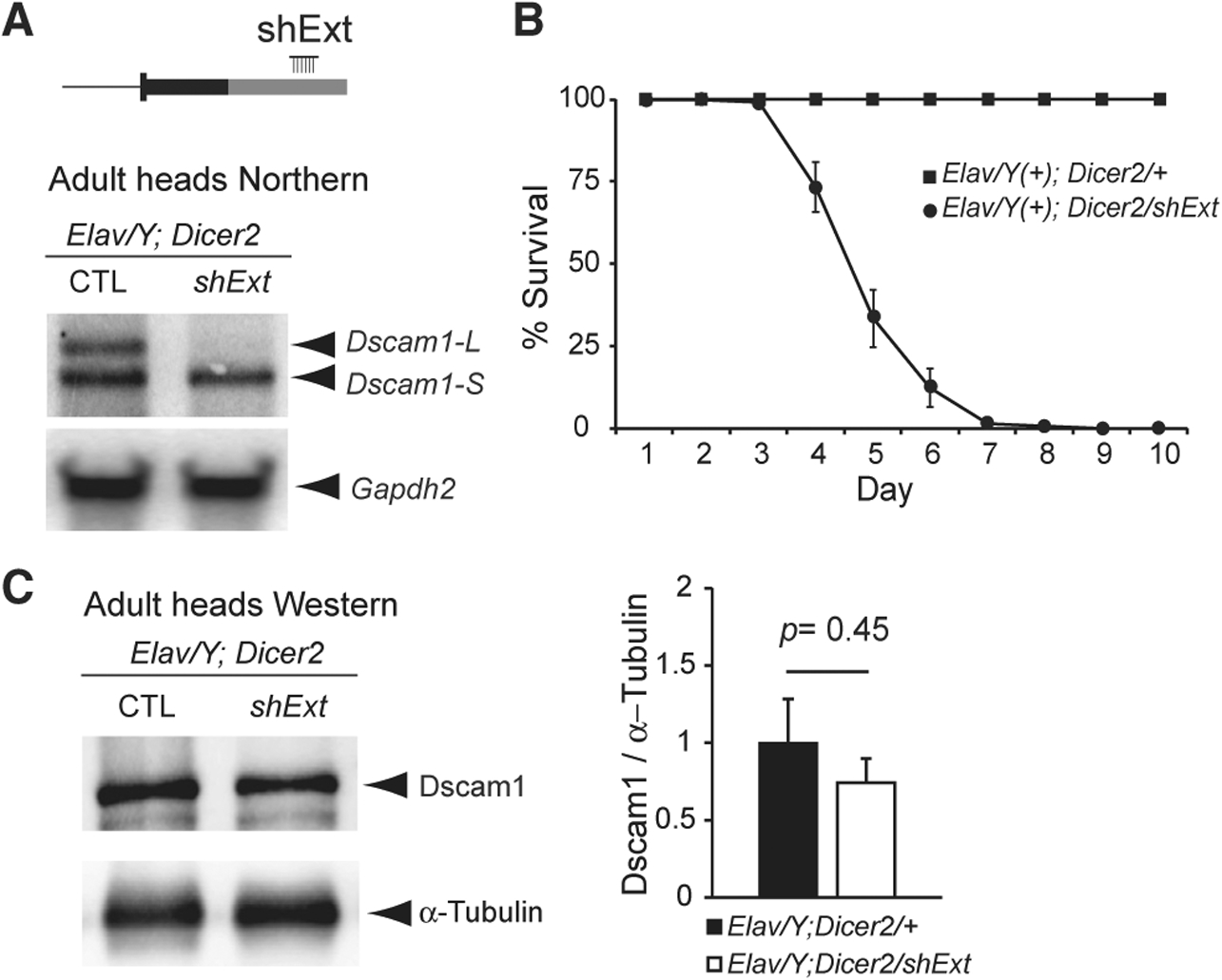

Knockdown of Dscam1-L in Neurons Is Lethal in Adult Flies

We next sought to determine a functional role for Dscam1-L transcripts in vivo. Using elav-GAL4, a neuronal-specific driver, we expressed an shRNA targeting the long (extended) 3′ UTR to neurons (shExt). Northern analysis of dissected male heads showed that Dscam1-L was undetectable in the knockdown condition, whereas Dscam1-S transcripts persisted (Figure 2A). This validated the effectiveness of the shRNA targeting and also provided additional support that Dscam1-L is exclusively expressed in neurons.

Figure 2. Dscam1-L Knockdown in Neurons Is Adult Lethal.

(A) Top: schematic showing location of shRNA to knockdown Dscam1-L (shExt) using the GAL4-UAS system. Bottom: northern analysis using a probe for Dscam1 common exon 11 shows that shExt driven by Elav caused loss of Dscam1-L in dissected heads.

(B) Dscam1-L knockdown caused reduced survival in mixed sex adult flies. n = 6; 20 flies per replicate.

(C) Western analysis of Dscam1 normalized to α-tubulin shows no significant difference in shExt heads compared with control heads. n = 7. p value represents two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

Elav represents ELAV-Gal4, and Dicer2 represents UAS-Dicer2. See also Video S1.

Neuronal knockdown of Dscam1-L using shExt yielded progeny that could survive to adulthood, unlike Dscam1 null flies (Schmucker et al., 2000). However, these animals displayed severely impaired locomotion and could not fly (Video S1). We quantified post-eclosion survival of adults and found that all progeny died by 9 days post-eclosion (Figure 2B). Thus, Dscam1-L expression in neurons is required for adult locomotion and survival. We anticipated that the loss of the long 3′ UTR isoform would impact translation of Dscam1. To our surprise, despite the loss of Dscam1-L in adult heads, Dscam1 protein levels were not significantly reduced as determined by western analysis (Figure 2C).

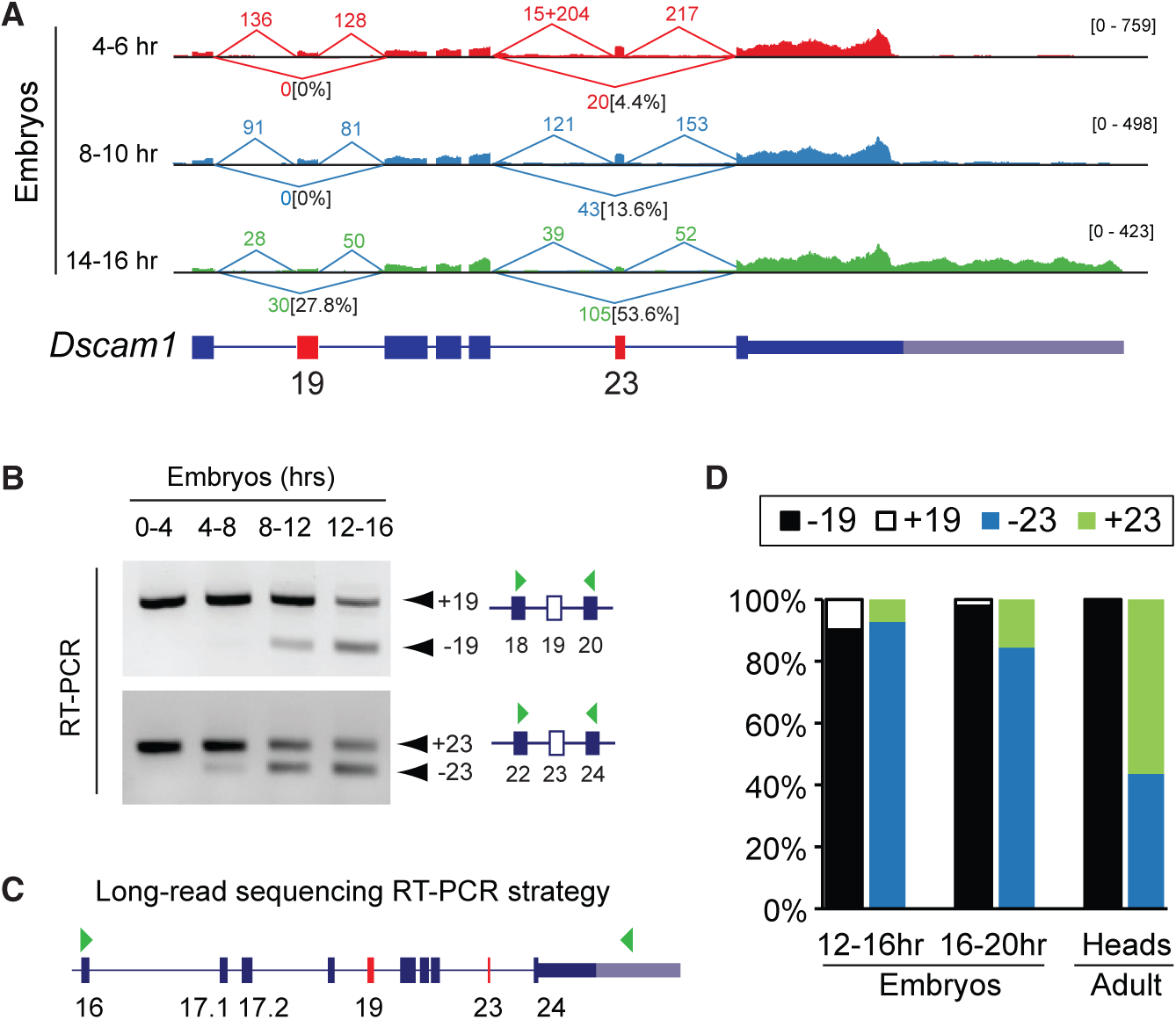

Long-Read Sequencing Demonstrates that Dscam1-L Preferentially Skips Exon 19

We were puzzled by the severity of the locomotion phenotype in Dscam1-L knockdown animals despite total Dscam1 protein levels being unaffected. We hypothesized that Dscam1-L transcripts might harbor particular protein-coding exons that are not found in Dscam1-S. Examination of short-read RNA-seq tracks at the Dscam1 locus from different stages of embryonic development revealed an apparent trend of alternative splicing that was coincident with the emergence of the long 3′ UTR in 14–16 h embryos (Figure 3A). In particular, visualization of splicing events revealed that in later-stage embryos there was increased skipping of exons 19 and 23 (Figure 3A). To confirm these trends, we monitored skipping of exons 19 and 23 during embryogenesis by RT-PCR. We found that late-stage embryos exhibited increased skipping of exons 19 and 23 compared with early-stage embryos (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Long-Read Sequencing Demonstrates that Dscam1-L Transcripts Preferentially Skip Exon 19.

A) Sashimi plot visualization of RNA-seq data at the Dscam1 locus showing spliced read counts from various stages of embryonic development. Note the increased skipping of exon 19 in 14–16 h embryos that correlates with long 3′ UTR expression. The percentage of reads skipping exons 19 and 23 is noted.

(B) RT-PCR shows skipping of exons 19 and 23 in late versus early stages of embryonic development.

(C) PCR strategy to capture cDNA products from Dscam1 exon 16 through to the long 3′ UTR in exon 24 (denoted by green arrowheads) for lon-gread sequencing. Note this strategy detects transcripts exclusively expressing the long 3′ UTR.

(D) Nanopore MinION long-read sequencing of RT-PCR products shows a progressive increase of exon 19 skipping during embryonic development, with all adult head Dscam1-L isoforms found to skip exon 19. Exon 23 usage in adult heads is mixed for Dscam1-L.

See also Figures S3 and S4.

In order to determine the connectivity of these exon-skipping events to the long 3′ UTR, we employed long-read Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencing. Conventional RNA-seq reads do not provide connectivity information for most transcripts because of the short length of reads. We devised a PCR strategy to capture the full content of Dscam1-L from exon 16 through to the long 3′ UTR (Figure 3C). This region contained both constitutively expressed and alternative exons. Note that this strategy provides information only on Dscam1-L transcripts, and not Dscam1-S. We performed MinION sequencing of these PCR products from cDNA of 12–16 h embryos, 16–20 h embryos, and adult heads. Counting of long reads showed that Dscam1-L transcripts progressively skipped exon 19 through the time points. Strikingly, 100% of the reads in adult heads were found to have exon 19 skipped (Figure 3D). In contrast, there was mixed usage of exon 23 for long 3′ UTR transcripts in adult head. This shows the preference for Dscam1-L transcripts to skip exon 19 in adult head. Analysis of the nanopore data revealed other interesting features of Dscam1 long 3′ UTR mRNAs (Figure S3). For instance, novel microexons flanking either side of exon 23 were observed in some amplicons, providing additional complexity to Dscam1 transcript isoforms (Figure S3).

Exon 18 of Dscam1 harbors additional complexity. Exon 18 uses two distinct splice donor sites that differ by 12 nt (Yu et al., 2009). The slightly longer exon 18 encodes four additional amino acids (T-V-I-S) (Figure S4A). Here, we call this variant exon 18-shifted (18 s). We analyzed short-read RNA-seq data during embryonic development, L3 CNS, and white pre-pupae (WPP) CNS to determine the isoform usage and connectivity of exons 18, 18 s, 19, and 20. For this analysis, we chose short-read RNA-seq datasets because 150-nt reads were long enough to resolve the connectivity, and they had a lower sequencing error rate compared with the MinION data. This analysis showed that transcripts skipping exon 19 predominantly used exon 18 s (18 s | − 19) versus exon 18 (18 | − 19). In contrast, transcripts including exon 19 rarely used 18 s (Figure S4B). Thus, in addition to CNS samples preferentially skipping exon 19, they also prefer usage of 18 s.

Dscam1-L Loss Impairs Axon Outgrowth

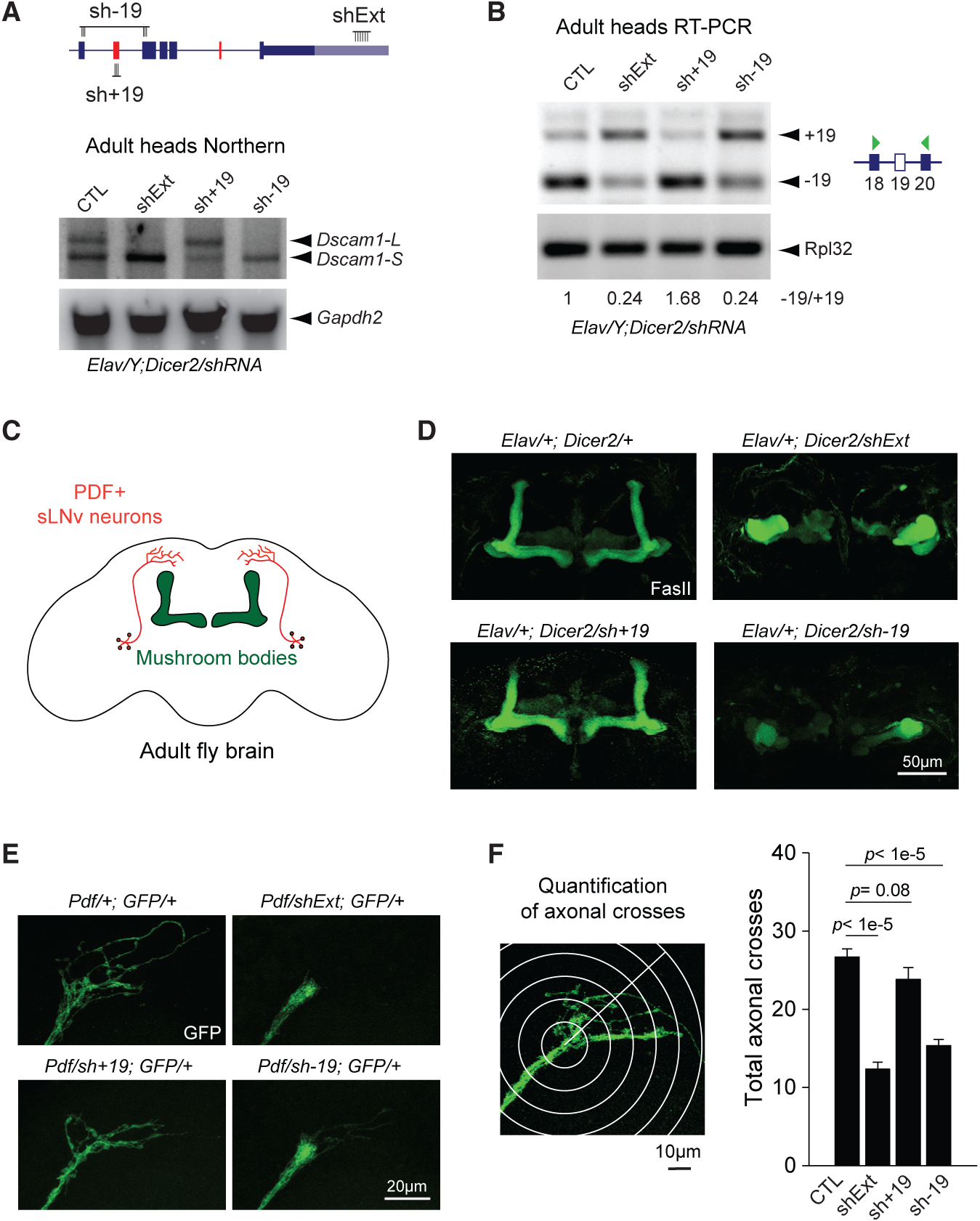

To provide conclusive evidence of the connectivity between exon 19 skipped transcripts and the long 3′ UTR, we obtained shRNA knockdown lines that have been previously validated to target Dscam1 transcripts including exon 19 (sh+19) or excluding exon 19 (sh−19) (Yu et al., 2009) (Figure 4A). The sh−19 shRNA targets the sequence spanning the junction of the exon 18 s 5′ splice site and exon 20 3′ splice site (18 s | − 19) (Figure S4A) (Yu et al., 2009). sh+19 targeted the sequence spanning the exon 18 5′ splice site and exon 19 3′ splice site (18 | +19).

Figure 4. Loss of Dscam1-L Impairs Axon Projection.

(A) Top: schematic of shRNA constructs targeting specific Dscam1 splice junctions (sh−19, sh+19) and the long 3′ UTR (shExt). Bottom: northern blot of male heads from Elav-driven shRNA knockdown shows loss of Dscam1-L upon knockdown with sh−19 or shExt, but not sh+19. Gapdh2 northern is shown as a loading control.

(B) RT-PCR shows exon 19 skipping patterns under knockdown conditions in adult heads.

(C) Schematic showing central brain and MB anatomy, with MB highlighted in green and sLNv neurons highlighted in red.

(D) Staining of adult brains with anti-Fasciclin II (FasII) reveals massive disorganization of the central brain and impaired bifurcation of the MBs upon neuronal knockdown using shExt and sh−19, but not sh+19.

(E) Impaired axonal outgrowth in adult sLNv neurons expressing sh−19 or shExt driven by Pdf-Gal4.

(F) Left: methodology of axonal outgrowth quantification of PDF-positive sLNv neurons. Right: Sholl analysis demonstrates that both shExt and sh−19 flies have significantly reduced axonal crossing compared with controls. Error bars represent SEM. n = 16–19.

Elav represents Elav-GAL4, Dicer2 represents UAS-Dicer2, shExt represents UAS-shExt, sh−19 represents UAS-sh−19, sh+19 represents UAS sh+ 19, and GFP represents UAS-mCD8::EGFP.

Knockdown in neurons using sh−19 led to effective reduction of Dscam1-L as shown by northern blot of dissected male heads, confirming that most Dscam1-L transcripts skip exon 19 (Figure 4A). As was previously found in the shExt condition, these flies also showed impaired locomotion and could not fly (Video S2). In contrast, knockdown using sh+19 did not reduce Dscam1-L expression. RT-PCR analysis revealed that knockdown using shExt or sh−19 increased the ratio of +19/−19 in heads (Figure 4B). As expected, sh+19 decreased the ratio of +19/−19 (Figure 4B).

We proceeded to employ these knockdown strategies to examine the cellular functions of Dscam1-L transcripts that skip exon 19. Previous work on Dscam1 null mutants has demonstrated the role of Dscam1 in axon branching and guidance (Wang et al., 2002). Using anti-Fasciclin II (FasII) staining to image the neuropil in the adult central brain (Figure 4C), we found that neuronal-specific knockdown of Dscam1-L using shExt impaired the axonal L-shaped bifurcation structure of the MBs, indicating a severe axonal developmental defect (Figure 4D). Neuronal sh−19 knockdown flies showed a very similar loss of MBs bifurcation defect, whereas sh+19 knockdown flies did not.

The above results suggested a role for Dscam1-L in axon growth and guidance. To further investigate the nature of this neurodevelopmental impairment, we used Pdf-GAL4 to drive GFP expression in pigment-dispersing factor (PDF)-positive ventral lateral neurons (LNvs) in adult brain. Among the PDF-positive LNvs, the sLNvs have stereotyped axonal projections toward the dorsal protocerebrum in adult fly brain that can be readily quantified for growth defects (Sivachenko et al., 2013) (Figure 4C). When we knocked down Dscam1-L in sLNv neurons, they failed to form arborized axonal terminals (Figure 4E). Using Sholl analysis (Sivachenko et al., 2013), we found that both shExt and sh−19 knockdown in sLNv cells resulted in a significant decrease in the number of axonal crosses, whereas sh+19 knockdown did not (Figure 4F). This defect shows clearly that without exon 19 skipped or long 3′ UTR Dscam1 mRNAs, neurons cannot undergo proper axonal outgrowth.

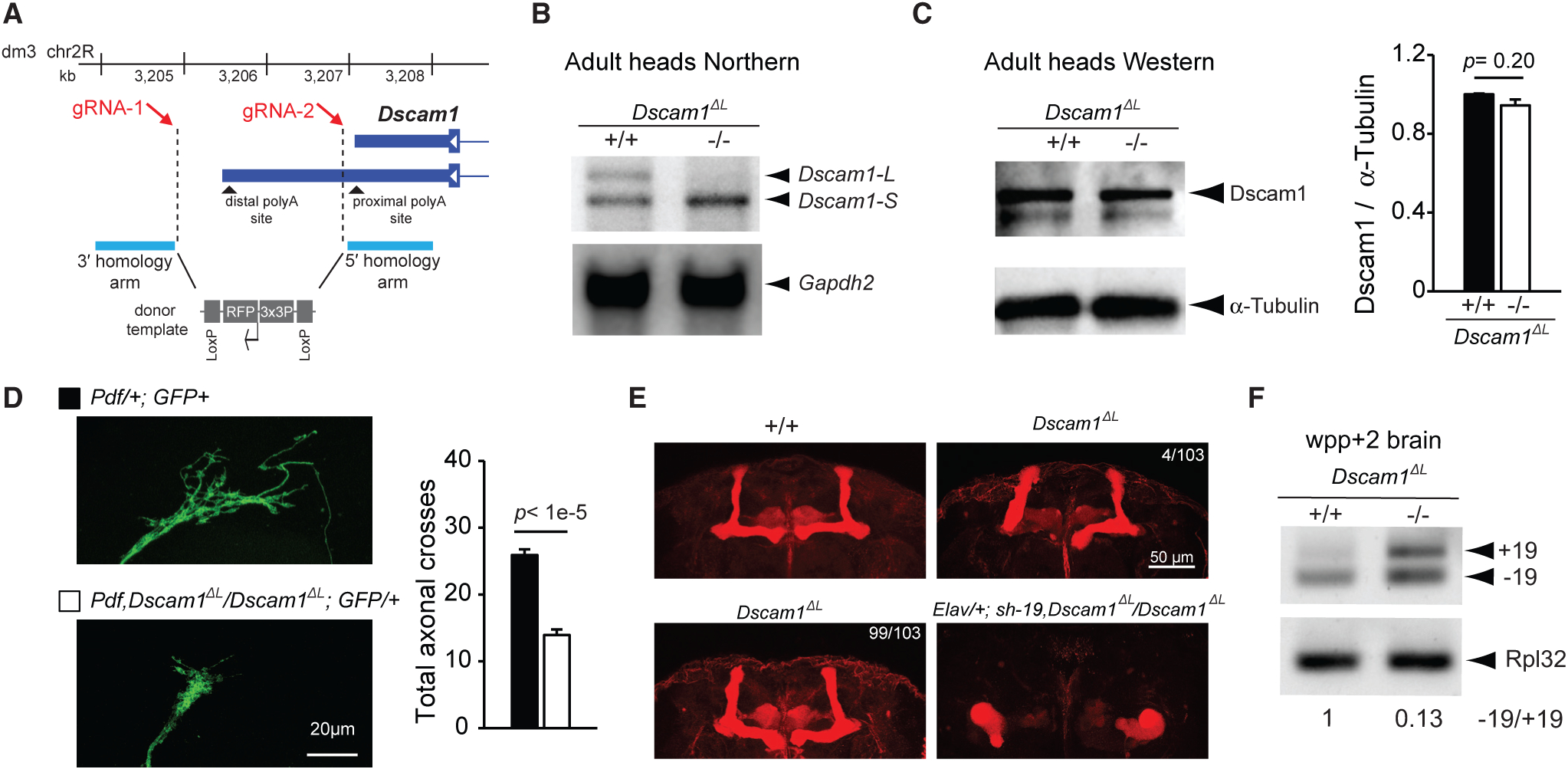

CRISPR Deletion of Dscam1-L

To validate the importance of Dscam1-L for correct axon outgrowth, we used CRISPR/Cas9 to generate flies harboring a deletion of the long 3′ UTR region (Dscam1ΔL). Using a homology-directed repair strategy (see STAR Methods), we removed the genomic region encompassing the distal polyA site and most of the long 3′ UTR, but retained the proximal polyadenylation site and replaced it with an RFP cassette (Figure 5A).Northern blot of adult heads revealed that Dscam1-L was completely lost, whereas Dscam1-S expression persisted (Figure 5B). As previously found for Dscam1-L shRNA knockdown, Dscam1 protein levels in heads were not significantly changed from the wild-type condition (Figure 5C). We found that sLNv neurons had reduced axon arborization in Dscam1ΔL flies (Figure 5D). Impaired bifurcation of the MBs was also observed; however, this phenotype was milder than that observed in the shExt experiments, with<4%of adults showing an abnormally thin or absent lobe (Figure 5E). The milder MB phenotype in the CRISPR Dscam1ΔL flies (Figure 5E) compared with the shExt condition (Figure 4D) led us to speculate that Dscam1–19 transcripts were primarily responsible for MB formation, more so than the long 3′ UTR. To test this, we performed shRNA knockdown of −19 in the Dscam1ΔL flies (Elav/+; sh−19, Dscam1ΔL/Dscam1ΔL) and found that 100% of these flies failed to properly form MB (Figure 5E).

Figure 5. CRISPR-Generated Dscam1ΔL Flies Show Impaired Axon Projection.

(A) CRISPR/Cas9 genome-editing strategy for deletion of the Dscam1 long 3′ UTR to generate Dscam1ΔL flies. Note that the design avoids disruption of the proximal polyA site.

(B) Northern analysis of head lysates using a probe targeting common Dscam1 exon 11 shows Dscam1ΔL flies lack expression of Dscam1-L. Gapdh2 northern is shown as a loading control.

(C) Anti-Dscam1 western blot of head lysates and quantification shows that Dscam1 expression is unchanged in Dscam1ΔL flies compared with control. n = 4.

(D) Left: representative images of sLNv neuron axon terminals from wild-type and Dscam1ΔL mutants. Right: quantification of sLNv neuron axon terminals shows significantly reduced axonal crosses. Pdf represents Pdf-GAL4, and GFP represents UAS-mCD8::EGFP. See STAR Methods for additional details. n = 18–19. All error bars represent SEM.

(E) Staining of adult brains with anti-Fasciclin II reveals impaired bifurcation of the MBs in Dscam1ΔL flies. There was low penetrance of this phenotype with 4/103 brains examined showing impaired bifurcation (top right), whereas 99/103 showed normal bifurcation (bottom left). In contrast, knockdown using sh−19 in the Dscam1ΔL background caused 100% of the flies to have malformed MBs (bottom right; Elav/+; sh−19, Dscam1ΔL/Dscam1ΔL, 7/7 brains examined).

(F) RT-PCR analysis of WPP +2 day brains show increased +19 expression and −19 expression in Dscam1ΔL mutants.

The increased severity of the MB phenotype in the Dscam1ΔL flies after knockdown of −19 transcripts suggested that −19 transcripts persist in expression in Dscam1ΔL flies. Performing an RT-PCR experiment for exon 19 splicing in WPP + 2 day brain samples, which are enriched for neurons, revealed that levels of −19 were not reduced, but instead were actually increased (Figure 5F). In addition, there was increased expression of +19 transcripts in the Dscam1ΔL mutants, which suggested alternative splicing of exon 19 was affected by long 3′ UTR loss (see below). Together, these results suggest that the severe MB phenotype is more attributed to the loss of the −19 transcripts. On the other hand, with no reduction in −19 expression detected in Dscam1ΔL brains (Figure 5F), the axon outgrowth phenotype in sLNv neurons might be more attributed to loss of the long 3′ UTR.

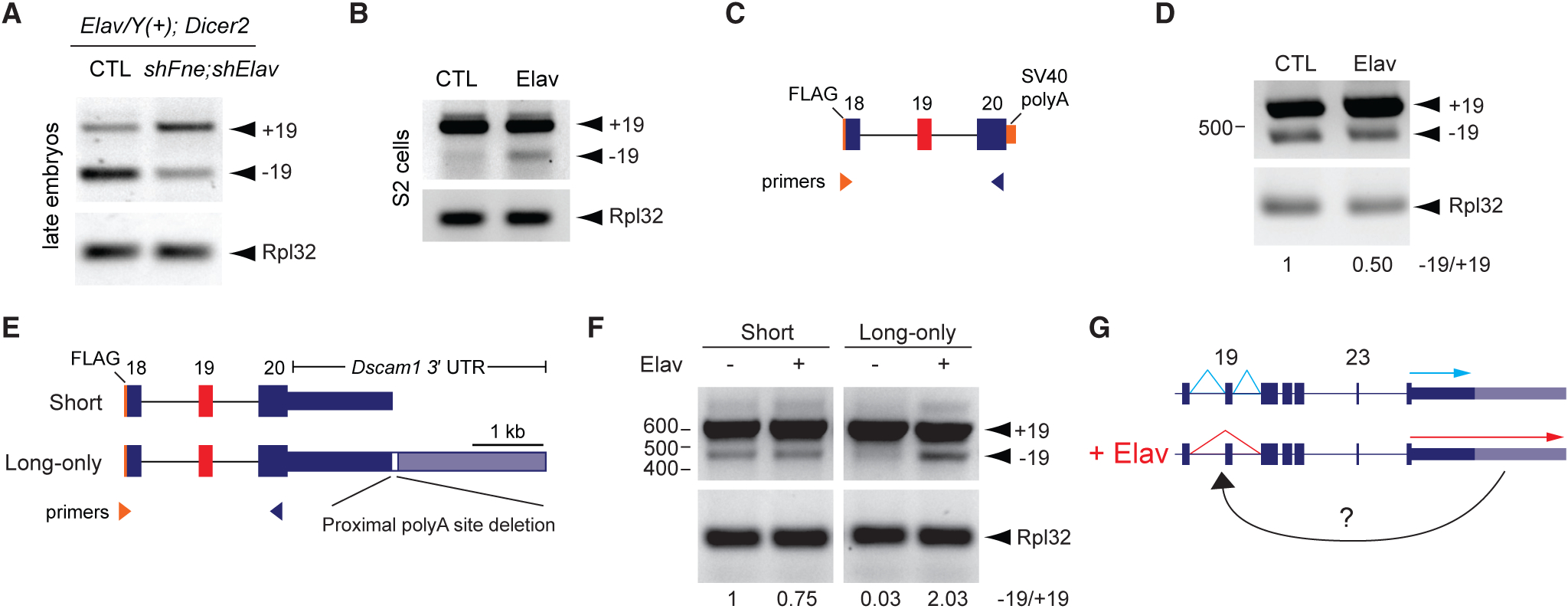

Dscam1 Long 3′ UTR Is Required for Elav-Mediated Regulation of Exon 19 Skipping

Given the established roles of Elav in alternative splicing, and the connectivity of exon 19 skipping events to the long 3′ UTR, we predicted that Elav might regulate exon 19 skipping. Knockdown of Elav/FNE in 16–20 h embryos resulted in a decrease in the ratio of −19/+19 as measured by RT-PCR (Figure 6A). S2 cells were found to express the +19 isoform, but the −19 isoform was nearly undetectable. Transient transfection of Elav led to a moderate increase in −19 expression (Figure 6B). We generated a mini-genereporter construct to monitor exon 19 splicing that included a sequence from exon 18 through exon 20, including intervening introns. This reporter contained a FLAG tag at the 5′ end to distinguish the reporter cassette from endogenous exon 19 splicing events and an SV40 polyA signal at the 3′ end (Figure 6C). Using RT-PCR, we observed a low level of exon 19 skipping from this reporter construct in the absence of Elav. Strangely, transient co-transfection with Elav failed to promote additional exon skipping (Figure 6D). This suggested to us that the exon 19 skipping event might require additional cis elements.

Figure 6. Elav-Mediated Exon 19 Skipping Requires the Dscam1 Long 3′ UTR.

(A) RT-PCR analysis of 16–20 h embryos shows that knockdown of Elav and the related protein FNE by shRNAs in neurons resulted in reduced −19 versus +19 transcripts. Elav represents Elav-GAL4, and Dicer2 represents UAS-Dicer2.

(B) Elav overexpression in S2 cells induced skipping of endogenous exon 19 as measured by RT-PCR.

(C) Schematic of exon 19 splicing mini-gene reporter. Note FLAG sequence at 5′ end allows for distinguishing reporter exon 19 splicing from endogenous exon 19 splicing.

(D) RT-PCR analysis shows no increase in exon 19 skipping from the reporter upon Elav overexpression.

(E) Top: schematic of mini-gene reporters and RT-PCR strategy. Note “long-only” reporter has sequence constituting the proximal polyA site deleted.

(F) RT-PCR analysis shows exon 19 skipping was induced only from the “long-only” reporter upon Elav overexpression.

(G) Schematic summarizing requirement of long 3′ UTR for correct Elav-mediated alternative splicing of exon 19.

We next tested whether the presence of the long 3′ UTR influences exon 19 alternative splicing. Mini-gene reporter constructs were generated that harbored the genomic region from exon 18 through exon 20 fused to the Dscam1 short 3′ UTR sequence (“short”) or long 3′ UTR sequence (“long-only”). The “long-only” reporter had the proximal polyA site deleted in order to prevent short 3′ UTR biogenesis and force expression of the long 3′ UTR (Figure 6E). No artificial polyA sequences were included at the 3′ end of these reporters. Reporter constructs were co-trans-fected with Elav in S2 cells, and skipping of exon 19 was measured by RT-PCR. The mini-gene reporter harboring the short Dscam1 3′ UTR showed mostly inclusion of exon 19, and Elav overexpression failed to induce additional exon skipping (Figure 6F). For the “long-only” reporter there was less expression of −19 in S2 cells in contrast with the “short” reporter, implying that the long 3′ UTR prevented exon 19 skipping in the absence of Elav. Strikingly, co-transfection of Elav with the “long-only” reporter led to a clear induction of exon 19 skipping (Figure 6F). Together with the observation that loss of the long 3′ UTR in pupal brain leads to de-regulated alternative splicing of exon 19 (Figure 5F), these results suggest that the long 3′ UTR contains information required for Elav-mediated skipping of exon 19.

DISCUSSION

APA most commonly changes the length of the 3′ UTR but does not alter the protein CDS (3′ UTR APA) (Miura et al., 2014; Tian and Manley, 2017). APA can also alter the entire terminal exon, resulting in unique 3′ UTRs and C-terminal protein-coding sequences (Alternative Last Exon APA) (Tian and Manley, 2017). Our work here presents a distinct paradigm involving the 3′ UTR APA of Dscam1 in the terminal exon (exon 24) being linked to skipping of a distant upstream exon (exon 19). This coordination of alternative splicing and APA is achieved via coregulation by the RBP Elav (Figure 6G). This represents a new category of RNA biogenesis regulation in which polyA site choice and upstream alternative splicing events are linked.

Given the connectivity of the Dscam1 long 3′ UTR to skipping of exon 19, it is difficult to decouple the relative contribution of the long 3′ UTR versus −19 transcripts to the neural phenotypes we observed. Some hints, however, can be gleaned by the differences in phenotype severity between the long 3′ UTR mutants versus the long 3′ UTR knockdown flies. Dscam1ΔL flies and shExt knockdown flies had similar axon outgrowth phenotypes in sLNv neurons. On the other hand, the MB phenotype was stronger in the knockdown condition compared with the mutant. We observed that −19 transcripts persisted in the Dscam1ΔL pupae nervous system (Figure 5F), whereas −19 transcripts were reduced in the shExt condition (Figure 4B). One interpretation of these differences is that the long 3′ UTR itself is required for sLNv axon outgrowth by conferring mRNA stability, mRNA localization, or translational control, whereas the MB phenotype is primarily attributed to the loss of the protein encoded by −19. In addition, the MB phenotype observed here in the long 3′ UTR shRNA knockdown condition is stronger than that observed when Dscam1 homophilic adhesion is removed (Sawaya et al., 2008), suggesting an axon growth function might also be affected (Kim et al., 2013). Although previous studies have investigated the functional roles of retaining or skipping exons 19 and 23 (Yu et al., 2009), it is unclear how the unique protein sequence of the “−19” isoform impacts Dscam1 binding or activity.

The approaches employed here of shRNA knockdown and CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing can be readily applied to the study of the long 3′ UTR isoforms of other APA-regulated genes. Of particular interest, several genes with roles in axon growth and development such as comm and fas1 generate alternative short and long 3′ UTR isoforms (Elkins et al., 1990; Simionato et al., 2007; Smibert et al., 2012). There are hundreds of neural-specific long 3′ UTR isoforms in Drosophila alone with unknown functions that remain to be interrogated in vivo using these approaches (Hilgers et al., 2012; Smibert et al., 2012).

The specific combination of Dscam1 long3′ UTR and alternative exon selection (Dscam1-L, −19) is restricted to neurons because of the expression pattern of Elav. Are other Drosophila genes regulated in this fashion? Given evidence that Elav can bind to DNA at promoter regions and affect APA (Oktaba et al., 2015), perhaps Elav-regulated APA events are also tied to alternative promoter selection in addition to alternative exon skipping. Do other RBPs with cell-specific expression patterns promote coupling of alternative splicing and APA in other cell types? Incorporating long-read sequencing technology with single-cell RNA-seq workflows could tackle this question on a genome-wide scale. Long-read sequencing has recently revealed a coupling among transcription initiation, alternative splicing, and APA in cultured human breast cancer cells (Anvar et al., 2018). As these technologies improve, more insights will surely be gained regarding the genome-wide scope of coordinated alternative splicing and APA.

Our data suggest that a novel function for long 3′ UTRs is regulating alternative splicing of upstream protein-coding exons. Loss of the Dscam1 long 3′ UTR by deletion conditions was found to de-regulate exon 19 skipping in vivo (Figure 5F). Mini-gene reporter experiments showed that the content of exon 19 flanking introns was not sufficient for Elav to promote exon skipping; only when the long 3′ UTR is appended to the reporter can Elav-induced skipping of exon 19 occur (Figure 6F). Further work is needed to identify the precise mechanism that couples Dscam1 long 3′ UTR selection to skipping of exon 19 (Figure 6G). An intriguing possibility is that Elav binds along the long 3′ UTR while the pre-mRNA is being transcribed and then is delivered to upstream cis-elements around exon 19 to promote alternative splicing. Such a mechanism might require additional RBPs binding to the Dscam1 long 3′ UTR and could involve looping of the pre-mRNA to bring the long 3′ UTR and exon 19 into spatial proximity.

STAR★METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Pedro Miura (pmiura@unr.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Drosophila rearing

All flies were raised at 25°C, 12-hr dark/12-hr light cycles on standard food (231 g cornmeal, 96 g yeast, 54 g agar, 231 mL molasses, 36 mL Tegosept, 24 mL propionic acid for 6L of food).

Embryo Collection

Flies with the genotype of interest were placed in cages containing grape agar and thin layer of yeast paste to lay eggs. Flies were synchronized by changing the plate two times after over the course of 24 hours. Following synchronization, flies were allowed to lay eggs for 4 hours per plate. Plates were then allowed to develop to the required time points. Embryos were dechorionated with 50% bleach and rinsed with water prior to downstream RNA or protein analysis.

Drosophila strains

Elav-GAL4; UAS-Dicer2 was a gift from Eric Lai (Sloan Kettering Institute). Stocks obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) include: repo-GAL4 (BL#7415), Elav-lexA (BL#52676), 20XUAS-6XmCherry (BL#52267), 13XlexAOP-GFP (BL#32203), and UAS-shElav (BL#28371). UAS-shFne was obtained from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center (VDRC # 101508). See Key Resources Table for complete details.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Dscam IC | Schmucker Lab | N/A |

| Mouse anti-Fasciclin II | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) | DSHB Cat# 1D4; RRID: AB_528235 |

| Rat monoclonal anti-Elav | DSHB | DSHB Cat# 7E8A10; RRID: AB_528218 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Elav | DSHB | DSHB Cat# 9F8A9; RRID: AB_528217 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-alpha-tubulin | DSHB | DSHB Cat# 12G10; RRID: AB_1157911 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Actin | DSHB | DSHB Cat# JLA20; RRID: AB_528068 |

| Cy3 Sheep Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 515-165-003; RRID: AB_2340315 |

| Peroxidase AffiniPure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 111-035-003; RRID: AB_2313567 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Proteinase K | Invitrogen | Cat# 25530015 |

| RNaseOUT Recombinant Ribonuclease Inhibitor | Invitrogen | Cat# 10777–019 |

| Pierce Protease Inhibitor | Invitrogen | Cat# 88666 |

| Effectene transfection reagent | QIAGEN | Cat# 301425 |

| Maxima Reverse Transcriptase | ThermoFisher | Cat# EP0741 |

| SYBR Green PCR Master Mix | Invitrogen | Cat# 4309155 |

| Amersham Megaprime DNA Labeling System | GE Healthcare | Cat# RPN1606 |

| HiFi Assembly Cloning Kit | NEB | Cat# E2621 |

| lysozyme | Sigma | Cat# L6876 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Dynabeads Protein G Immunoprecipitation Kit | Invitrogen | Cat#1007D |

| SQK-LSK108 Ligation Sequencing Kit 1D | Oxford Nanopore Technologies | Cat# SQK-LSK108 |

| EXP-PBC001 PCR Barcoding Kit I | Oxford Nanopore Technologies | Cat# EXP-PBC001 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Nanopore Long-read sequencing raw data for Dscam1-L from exon 16 through extened 3′UTR | This paper | SAMN11457160, SAMN11457161, SAMN11457162 |

| 6–8 hr after egg laying embryos RNA-seq | Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP) | SRX246422 |

| 16–18 hr embryos RNA-seq | BDGP | SRX246418 |

| L3 CNS RNA-seq | BDGP | SRR070410 |

| 4–6 hr embryos RNA-seq | BDGP | SRX246408 |

| 8–10 hr embryos RNA-seq | BDGP | SRX246409 |

| 14–16 hr embryos RNA-seq | BDGP | SRX246412 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| D. melanogaster: Cell line S2: S2-DRSC | Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (DGRC) | Cat# 6 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| UAS-sh-Dscam1-ext | This paper | N/A |

| Dscam1 ΔL | This paper | N/A |

| UAS-sh+19 | Bing Ye Lab | N/A |

| UAS-sh-19 | Bing Ye Lab | N/A |

| Elav-GAL4; UAS-Dicer2 | Eric Lai Lab | N/A |

| UAS-shElav | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) | BL28371 |

| UAS-shFne | Vienna Drosophila Resource Center (VDRC) | VDRC-101508 |

| Pdf-GAL4; UAS-mCD8::EGFP | Yong Zhang Lab | N/A |

| repo-GAL4 | BDSC | BL#7415 |

| Elav-lexA | BDSC | BL#52676 |

| 20XUAS-6XmCherry | BDSC | BL#52267 |

| 13XlexAOP-GFP | BDSC | BL#32203 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for northern, RT-qPCR, and PCR see Table S1 | This paper | Table S1 |

| Primers to generate shRNA for Dscam1-ext | This paper | N/A |

| Forward: 5′- GATCGCTAGCAGTAGGCGTTTAGTTT | ||

| CACTTCAATAGTTATATTCAAGCAT A-3′; | ||

| Reverse: 5′-GATCGAATTCGCAGGCGTTTAGTTT | ||

| CACTTCAATATGCTTGAATATAACT A-3′. | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pWALLIUM20 | Harvard Medical School | N/A |

| Ubi-GAL4 | Eric Lai Lab | N/A |

| pUASTattB | Eric Lai Lab | N/A |

| pUASTattB_EGFP_SV40 | Jung H Kim Lab | N/A |

| pUAST-HA-elav | This paper | N/A |

| pUASTattB_EGFP_Dscam1–3′ UTR | This paper | N/A |

| pUASTattB_mini-gene_S | This paper | N/A |

| pUASTattB_mini-gene_L_only | This paper | N/A |

| pDEST60-Elav | This paper | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | Schindelin et al., 2012 | https://fiji.sc/ |

| Albacore 2.0.1 | Oxford Nanopore Technologies | https://community.nanoporetech.com/downloads |

| Isocount 1.1.0 | Matthew Bauer | https://github.com/bauersmatthew/isocount |

| Porechop version 0.2.3 | Ryan Wick | https://github.com/rrwick/Porechop |

Genotypes represented across figures

| Figure | Panel | Genotype | Gender | Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 1 | B | w1118 | mixed | embryos |

| C | Elav-lexA/UAS-mCherry;lexAOP-GFP/repo-GAL4 | mixed | adult brain | |

| D | Elav-GAL4/Y(+);UAS-Dicer2/+ | mixed | 16–20 hr embryos | |

| Elav-GAL4/Y(+);UAS- | ||||

| Dicer2/UAS-shFne;UAS-shElav/+ | ||||

| E | w1118 | mixed | 12–16 hr embryos | |

| Figure 2 | A, C | Elav-GAL4/Y;UAS-Dicer2/+ | male | adult heads |

| Elav-GAL4/Y;UAS- | ||||

| Dicer2/UAS-shExt | ||||

| B | Elav-GAL4/Y(+);UAS-Dicer2/+ | mixed | adult heads | |

| Elav-GAL4/Y(+);UAS- | ||||

| Dicer2/UAS-shExt | ||||

| Figure 3 | B | w1118 | mixed | embryos |

| D | w1118 | mixed | 12–16 hr embryos | |

| 16–20 hr embryos | ||||

| adult male heads | ||||

| Figure 4 | A, B | Elav-GAL4/Y;UAS-Dicer2/+ | male | adult heads |

| Elav-GAL4/Y;UAS-Dicer2/UAS-shExt | ||||

| Elav-GAL4/Y;UAS-Dicer2/UAS-sh+19 | ||||

| Elav-GAL4/Y;UAS-Dicer2/UAS-sh-19 | ||||

| D | Elav-GAL4/+;UAS-Dicer2/+ | female | adult brain | |

| Elav-GAL4/+;UAS-Dicer2/UAS-shExt | ||||

| Elav-GAL4/+;UAS-Dicer2/UAS-sh+19 | ||||

| Elav-GAL4/+;UAS-Dicer2/UAS-sh-19 | ||||

| E, F | Pdf-GAL4/+;UAS-GFP/+ | male | adult brain | |

| Pdf-GAL4/UAS-shExt;UAS-GFP/+ | ||||

| Pdf-GAL4/UAS-sh+19;UAS-GFP/+ | ||||

| Pdf-GAL4/UAS-sh-19;UAS-GFP/+ | ||||

| Figure 5 | B, C | w1118 | mixed | adult heads |

| Dscam1ΔL | ||||

| D | Pdf-GAL4/+;UAS-GFP/+Pdf-GAL4,Dscam1ΔL / Dscam1 ΔL;UAS-GFP/+ | male | adult brain | |

| E | w1118 | female | adult brain | |

| Dscam1ΔL | ||||

| Elav-GAL4/+;UAS-sh-19,Dscam1 ΔL/Dscam1ΔL | ||||

| F | w1118 | mixed | white prepupae +2 day brain | |

| Dscam1ΔL | ||||

| Figure 6 | A | Elav-GAL4/Y(+);UAS-Dicer2/+ | mixed | 16–20 hr embryos |

| Elav-GAL4/Y(+);UAS- | ||||

| Dicer2/UAS-shFne;UAS-shElav/+ | ||||

| Figure S1 | B, C | w1118 | mixed | embryos |

| Figure S3 | A | w1118 | male | adult heads |

| B | w1118 | mixed | 16–20 hr embryos | |

| C | w1118 | mixed | 12–16 hr embryos | |

| Video S1 | Elav-GAL4/Y;UAS-Dicer2/UAS-shExt | mixed | adult | |

| Video S2 | Elav-GAL4/Y;UAS-Dicer2/UAS-sh-19 | mixed | adult |

METHOD DETAILS

RNA-Seq track visualization

Visualization of RNA-Seq .bam files generated by the modENCODE consortium was performed using Integrated Genomics Viewer (IGV) (Thorvaldsdόttir et al., 2013). Sashimi plots were generated in IGV using minimum exon coverage “7.”

Western Analysis

Fly heads or embryos were collected and lysed with protein extraction buffer (1% Triton X-100, 100 mM pH 6.8 Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and protease inhibitor tablet (Thermofisher Scientific A32955)). Protein samples were prepared with denaturing buffer (5% β-Mercaptoethanol, 0.2 M pH 6.8 Tris-HCl, 8% SDS, 40% Glycerol, 0.1% Bromophenol blue) and boiled at 95°C for 5 mins. Fifteen μg of sample was loaded in each well of a 7% SDS-PAGE gel, and then transferred to the membrane with Turbo Mini PVDF Transfer Pack (#1704156, Bio-Rad). The blot was then blocked with 5% BSA in TBST (0.5% Tween-20 in TBS), incubated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight, washed with TBST and incubated with secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc.) at room temperature (RT) for 1 hour, and washed prior to ECL detection (20–302B, Genesee Scientific Corporation) and imaged using the ChemiDocTM Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc). Rabbit anti-DSCAM-cytoplasmic domain was used at 1:1500 (gift from Dr. Dietmar Schmucker) (Dascenco et al., 2015). Anti-alpha-tubulin was used at 1:400 (12G10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), rat anti-Elav at 1:750 (7E8A10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), and anti-actin at 1:100 (JLA20, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank).

Immunohistochemistry

Flies were collected and brains dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then fixed in 4% PFA at RT for 30 mins, blocked with 5% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBST (0.3% Trition X-100 in PBS) at RT for 1 hr. Samples were incubated with primary at 4C overnight, and washed 3 3 15 min in PBST. Secondary antibody incubation (Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc.) was performed at R.T. for 1 hour, then washed 3 3 15 min with PBST and mounted with Vectashield Mounting Medium (H-1000, Vector Laboratories). Imaging was performed using a Leica TCS SP8 microscope. Anti-Fasciclin II was used at 1:20 (1D4, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Anti-mouse Cy3 secondary antibody was used at 1:500 (Cat# 515-165-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch).

S2 Cell Transfection

Schneider 2 cells were obtained from Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (DGRC). Cells were cultured in Schneider’s Drosophila medium (ThermoFisher CAT# 21720024), with the addition of 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals CAT# S11150) at 25°C. For transient transfection, cells at 80% confluent were transfected using Effectene transfection reagent (QIAGEN CAT# 301425) according to the manufacturer’s protocol for suspension cells. For co-transfections, 600 ng of Ubiquitin-GAL4 plasmid (gift from Eric Lai), 300 ng of reporter, and 300 ng of UAS-ELAV or empty vector control was added (per 35 mm well). Cells were collected 48 hours post-transfection and pelleted in preparation for RNA extraction. UAS-Elav contained the coding region of Elav with sequence encoding for FLAG-HA tag at the N terminus (5′-GACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGTACCCTTATGACGTGCCCGATTACGCT-3′) and was cloned using pUASTattB vector (gift from Eric Lai).

RNA Extraction

RNA extracted from cell culture and Drosophila was performed using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen CAT# 15596026) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Following extraction, and prior to cDNA synthesis, RNA was DNase treated using the DNA-free DNase Treatment and Removal Reagents (Ambion CAT# 1906) following the manufacturer’s “Routine DNase treatment” protocol.

cDNA Preparation, qPCR, end-point PCR

DNase treated RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using Maxima Reverse Transcriptase (ThermoFisher CAT# EP0741) with random hexamers unless otherwise noted. cDNA was then diluted 1:5 in ddH2O prior to qPCR. Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Invitrogen CAT# 4309155). Real time PCR was performed using a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad CAT#1855195). All data was analyzed using Bio-Rad CFX software. End point PCR was performed using Taq polymerase at optimized cycle number, and products were run on 1%–2.5% Agarose gels with EtBr prior to imaging. Quantification of band intensity was performed using Image Lab version 6.0.1 (Bio-Rad). PCR Primer sequences can be found in Table S1.

Northern Analysis

Northern analysis was performed as previously described (Gruner et al., 2016) using P32 labeled DNA probes. Briefly, Glyoxal-DMSO was used to denature RNA and electrophoresis was performed using 1% BPTE agarose gels. Transfer to Nylon membrane was performed using Turboblotter (Whatman). After transfer and washing, blot was crosslinked using a UV Stratalinker 1800 (Stratagene). DNA probes were prepared using Megaprime DNA labeling system (GE Healthcare, RPN1606) labeled with α32-P dCTP (Perkin Elmer). Probing was performed in a hybridization oven overnight at 45–55°C using ULTRAhyb hybridization buffer (ThermoFisher, AM8669), followed by 3–4 washes at 50–60°C and exposure on phosphoscreen. Image acquisition was performed using a FLA7000IP Typhoon Storage Phosphorimager using Typhoon FLA 7000 control software Version 1.3 (GE Healthcare).

Reporter Plasmid Subcloning

For the Dscam1 3′ UTR Reporter, the long Dscam1 3′ UTR starting from after the stop codon until past the distal poly A site was amplified using iProof High-fidelity PCR kit (Bio-Rad Cat#1725330) and subcloned into GFP reporter constructs plasmids (Kim et al., 2013) from which the SV40 polyA site was removed to generate GFP-3′ UTR-L. For the Dscam1 Mini-gene reporter containing no Dscam1 3′ UTR, Dscam1 sequence from exon 18 to 20 was amplified using LongAmp Taq polymerase (FLAG tag was added to the 5′ end) and subcloned into the GFP reporter containing the SV40 polyA signal. Then, the GFP coding sequence was removed by restriction digest. Dscam1 short 3′ UTR or Dscam1 long-only 3′ UTR was subcloned downstream of exon 20 to generate “Short” and “Long-only” reporters used in Figure 6F. For the “Long-only” 3′ UTR reporter, a 64-nt deletion: (5′-AAATATATGATTTTGATTTTATTTTTAATTGATTACGTTCGCTTTTGTTTGATTATTGTTTTGG-3′) was made to remove the proximal polyA site using HiFi Assembly Cloning Kit (NEB CAT#E2621).

RIP RT-qPCR

Embryos (12–16hr) were collected and nuclear extraction was performed as previously described (Hilgers et al., 2012). Nuclei were sonicated for 10 cycles of 30 s on/30 s off on Branson Sonifier 450. Nuclear extracts containing fragmented RNA were subjected to immunoprecipitation following the standard protocol of Dynabeads Protein G Immunoprecipitation Kit (CAT#1007D). Samples were incubated overnight at 4°C with a mixture of 1 μg rat and 1 μg mouse anti-Elav antibodies (DSHB CAT#7E8A10 and CAT#9F8A9, respectively) or a mixture of 1 μg rat and 1 μg mouse IgG (Rockland CAT#012–0102 and CAT#010–0102, respectively). Proteinase K treatment was performed prior to reversal of cross-links performed for 1 hr × 68°C. RNA was extracted from input control immunoprecipitates using Trizol and then treated using Turbo DNA free Kit. After performing reverse transcription using random hexamers, samples were used at 1:5 dilution for qPCR.

Generation of shRNA lines

For generating the shExt shRNA construct the following primers were used: Forward: 5′-GATCGCTAGCAGTAGGCGTTTAGTTTCACTTCAATAGTTATATTCAAGCATA-3′; Reverse: 5′-GATCGAATTCGC AGGCGTTTAGTTTCACTTCAATATGCTTGAATATAACTA-3′. NheI and EcoRI were the restriction sites used to clone the short hairpin into pWALIUM20 vector (Harvard Medical School). Plasmid DNA was obtained using QIAGEN Plasmid Plus Midi Kit (QIAGEN CAT#12945) and sent for microinjection (BestGene) into the y1 w67c23;P{CaryP}attP40 strain. Other shRNA lines including sh−19, sh+19 have been previously described (Yu et al., 2009) and were gifts from Dr. Bing Ye (University of Michigan).

Generation of Dscam1ΔL flies by CRISPR/Cas9 Deletion

CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing was performed by Well Genetics. Two gRNAs were designed flanking the long 3′ UTR of Dscam1 which caused double-stranded breaks at positions chr2R:3,204,852 and chr2R:3,206,926 generating a nearly 2 kb deletion (dm3 genome coordinates). A 134 bp region between the proximal Dscam1 short 3′ UTR cleavage site and the first double-stranded break was left intact in order to not disturb any potential DSEs important to proper cleavage and polyadenylation of the short 3′ UTR isoform. Homology directed repair was used to knock-in a 1.8 kb RFP cassette containing loxP sites. RFP was used as a visible marker for screening successful mutants. Three successful Dscam1ΔL mutants were generated with the expected deletion and knock-in. Flies were balanced over CyO or GFP, CyO to create stable stocks.

Longevity Assay

Flies were collected within 24 hr after eclosion, and raised 20 flies per vial (male and female) with standard food. The number of surviving flies was recorded every day at the same time point.

Sholl Analysis

One to 3 days old male flies were collected, and kept for two days before dissection. Male brains were dissected and fixed in 4% PFA (paraformaldehyde) in PBST for 30 mins at room temperature, washed 3×15 min with PBST, and then mounted with Vectashield Mounting Medium. Samples were imaged under Leica TCS SP8 microscope, and then images were quantified using the sholl analysis plugin (Fernández et al., 2008) in the FIJI ImageJ distribution (Schindelin et al., 2012). Six concentric rings (radius step size = 10 μm) centered at the point where the first-class branches open up were drawn on each brain hemisphere. The total number of intersections of all branches crossing the six rings was counted. Data was collected from both brain hemispheres and the average of them was used as one sample for quantification. For statistical test, Mann Whitney test for non parametric samples was used.

FAC sorting of neurons and glia from adult brains

To generate a transgenic fly expressing fluorescence tags for neurons and glia, Elav-lexA (BL#52676), 20XUAS-6XmCherry (BL#52267), 13XlexAOP-GFP (BL#32203), and repo-GAL4 (BL#7415), and y1w1;CyO/Sco;MKRS/Tm6B,Tb were used to generate Elav-lexA/20XUAS-6XmCherry;13XlexAOP-GFP/repo-GAL4. All of these stocks were balanced using y1w1;CyO/Sco;MKRS/ Tm6B,Tb. Preparation of brains for FACS was performed based on a previously described protocol (Nagoshi et al., 2010). Briefly, 40 – 50 adult brains were dissected in a dissection saline (9.9 mM HEPES-KOH buffer, 137 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.17 mM NaH2PO4, 0.22 mM KH2PO4, 3.3 mM glucose, 43.8 mM sucrose, pH 7.4) containing 50 μM D(–)-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (AP5), 20 μM 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX), 0.1 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX) and then transferred to a modified SMactive medium (SMactive medium containing 5 mM Bis-Tris, 50 μM AP5, 20 μM DNQX, 0.1 μM TTX). After dissection, brains were washed again with the dissection saline and then digested with L-cysteine-activated papain (50 units/mL in dissection saline; Worthington). Reaction was then quenched with SMactive media and the brains were triturated with a flame-rounded 1000 μL pipette tip and a flame-rounded 200 μL pipette tip. Prior to FACS selections, Hoechst 33528 was added as a viability marker. Individual samples were sorted for neurons (Elav-positive cells) and glia (repo-positive cells) using the BD FACSAria II SORP with 70 μm nozzle at 70 psi. FACS was performed at the Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting/Flow Cytometry Shared Resource Laboratory at the UNR School of Medicine. RNA from isolated neurons and glia was extracted using Trizol.

Nanopore Minion sequencing

Amplification from cDNA of a region encompassing Dscam1 exon 16 until within the long 3′ UTR was performed using the following primers (forward: 5′-TTTCTGTTGGTGCTGATATTGCCGAATACGACTTTGCCACCT-3′; reverse: 5′-ACTTGCCTGTCGCTCTAT CTTCTCTGTAGCTCCATTGCATCG-3′). The PCR product was purified using AMPure XP beads (A63881, Beckman Coulter Life Science), and then used as a template for PCR amplification using nanopore barcodes primers (SQK-LSK108 Ligation Sequencing Kit 1D, and BC001, BC002, BC010 in EXP-PBC001 PCR Barcoding Kit I, from Oxford Nanopore Technologies) to obtain barcoded amplicons. PCR products (1 μg in total) extracted from magnetic beads was used for Nanopore sequencing with FLO-MIN 107 flowcell.

Analysis of Minion data

Raw data demultiplexing and basecalling were performed with Albarcore 2.0.1 provided by Oxford Nanopore. Reads were trimmed using porechop version 0.2.3 (https://github.com/rrwick/Porechop) using default settings. Reads were aligned to the full Dscam1 gene sequence from the DM6 assembly using gmap version 2018-02-12 and the ‘-f samse–sam-extended-cigar’ settings. Alignment isoforms were identified and counted using isocount 1.1.0 (https://github.com/bauersmatthew/isocount) and the ‘–antisense -c 75,15’ settings. Based on the overall coverage distributions for each feature, a > 75% coverage cutoff was used for feature inclusion and a < 15% coverage cutoff was used for feature exclusion. Dscam1 exon, intron, and 3′ UTR positions were obtained from the Ensembl Dme v89 annotation. Isoforms not conforming to all of the following requirements were excluded from further analysis: 1- Inclusion of both the long and short 3′ UTR. 2- Exclusion of all intron sequence. 3- Inclusion of the constitutive exons 16, 18, 20, 21, and 22. 4- Usage of exactly one of exon 17.1 or 17.2.

Elav Protein Expression and Purification

The coding region of Elav was PCR amplified from cDNA isolated from w1118 Drosophila using AccuPrime Pfx DNA polymerase and subcloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen CAT# K240020) donor vector. The destination vector chosen was pET-60-DEST (Novagen CAT# 71851–3). The destination vector was grown up in One Shot ccdB Survival 2T1R cells (Invitrogen CAT# A10460). Both vectors were then prepared using midi-prep (QIAGEN CAT# 12945). The final expression vector was made using LR Clonase II (Invitrogen CAT#11791–020) enzyme per the manufacturer’s protocol, which flipped the Elav coding region into the pDEST60 vector with the N- and C-terminal tags. BL21(DE3) Competent E. coli (New England Biolabs CAT# C2527l) were transformed with pDEST60-Elav construct according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were collected by centrifugation in 50 mL centrifuge tubes for 15 minutes at 3000 rpm and resuspended in 5 mL of water and centrifuged again to rinse off leftover media. The pellet was resuspended in 30 mL of a buffer containing 25 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole and 10 mM MgCl2 with the addition of a protease inhibitor tablet (Thermo Scientific CAT#88666) and 30 μg of lysozyme (Sigma CAT# L6876). The mixture was left to incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature. The cells were then sonicated (Branson Sonicator 450) on ice six times for 15 s intervals at a power level of four. The sample was then centrifuged at 28,000 rpm for 1 hour at 4°C. Following sonification, 900 mL of a buffer containing 25 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole and 10 mM MgCl2 and 290 μL of 2-mercaptoethanol was prepared. 2 mL of glutathione agarose (Thermofisher CAT# 16100) was then mixed with 48 mL of the buffer just prepared, and was allowed to sit so the beads settled. Supernatant was then removed leaving only the beads at the bottom of the tube. The supernatant from the 1 hour centrifugation step was then added to the beads and incubated for 2 hours at 4°C with rocking. The rest of the purification took place at 4°C in a cold room. A chromatography column (Bio-Rad CAT# 7374021) was rinsed with the imidazole buffer containing the 2-mercaptoethanol, and all 50 mL of the supernatant-glutathione bead mix was added to the column, allowing the beads to compact in the column. Some flow-through was kept for quality analysis. To remove any material not bound to the agarose beads, 150 mL of the buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol was added to the column to wash the beads, and the flow-through was discarded. To remove the Elav bound protein, 0.28 g of reduced L-glutathione (Sigma CAT# G4251) was added to 30mL of the buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol. Ten mL of the reduced L-glutathione solution was added to the column and left to incubate for 5 minutes. Following incubation, 8×1 mL aliquots were collected. To determine which fraction contained the highest concentration of Elav, 5 μL from each fraction (and also the flow-through samples collected) was aliquoted and added to new tubes each containing 5 μL of SDS loading buffer. The samples were heated at 95°C for 5 minutes and then all samples were ran in a tris glycine gel for 30 minutes. The gel was then stained for 30 minutes while shaking in a solution containing 3.75 mL of acetic acid, 46.25 mL of ddH2O and 10 μL of Sypro orange (ThermoFisher CAT# S6650). The gel was then scanned on a gel imager (GE Healthcare Typhoon Trio) to determine which fraction contained the most protein. The fraction with the most protein was quantified using a BSA standard curve protocol, using ImageJ to quantify pixel intensity of the Flamingo-stained (Bio-Rad CAT#161–0490) TrisGlycine Gel.

EMSA RNA Probe preparation

RNA oligo nucleotide probes was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. See Figure S2 for EBS and Mutant probe sequences. Oligos were then purified by PAGE prior to use. Each 2.5 pmol sample was 5′ labeled with γ32-P. Sample was dried by SpeedVac. A master mix containing 1ul of T4 Polynucleotide Kinase buffer, 5.6 μL Water, and 0.4 μL of T4 polynucleotide kinase was prepared. The dried RNA was resuspended with 7 μL of the master mix. Three μl of [γ32-P] ATP was added to each sample and left to incubate at 37°C for one hour. Probes were then purified using Illustra Microspin G-25, and PAGE purified.

EMSA

A 4% acrylamide:bisacrylamide 80:1 native gel was prepared (27.25 mL DEPC treated water, 1.65 mL 10xTBE, 3.3 mL 40% acrylamide, 830 μL 2% bisacrylamide, 133 μL of 10% APS, and 66.6 μL of Temed) and left to polymerize for at least 2 hours. RNA samples were resuspended in hybridization buffer (10 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM EDTA) so that the final concentration was 10 times less than the molar concentration of the ELAV protein sample. Samples were then incubated at 65°C for 5 minutes. A master mix was prepared consisting of 1 μL 10× reaction buffer (450 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM NaCl, and 400 mM KCl), 1 μL of 250 μg/mL tRNA, 1 μL 5 mM DTT, 1 μL 500 μg/mL BSA, and 1 μL of 6 units/μl RNase inhibitor. Five ml of the hybridization mix was aliquoted per sample and 4.35 μL of ELAV protein, or GST buffer without protein was added to each tube. Then 0.65 μL (154 nM) of RNA sample was added to its respective tube. Hybridization was allowed to take place for 20 minutes at room temperature, and then 3 μL of loading buffer was added to each sample. The gel was pre-run for 15 minutes at 250V, then samples were loaded and run for 140 minutes in a cold room at 4C. Gels were then dried on a gel dryer at 80°C for 1 hour with vacuum. A phosphor screen was exposed to the gel overnight and imaged the following day.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS. Details of all statistical tests used can be found in the figure legends. All p values are reported in the figures. For qPCR analysis using the ΔΔCT method and Western analysis by densitometry, two-tailed Student’s t test was used. For Sholl analysis, Mann Whitney test for non-parametric samples was used. Data is presented as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean).

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Raw sequence reads from ONT MinION runs are deposited at the sequence read archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) for 12–16 hr embryos (SAMN11457160) 16–20 hr embryos (SAMN11457161) and adult heads (SAMN11457162). Isocount 1.1.0 software is available at https://github.com/bauersmatthew/isocount. Previously deposited Long Read RNA-Seq tracks were produced from the modENCODE project and are available on Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra): L3 CNS (SRR070410), 6–8 hr after egg laying (a.e.g.) embryos (SRX246422), 16–18 hr embryos (SRX246418). RNA-Seq tracks used for sashimi-plot splicing visualization included 4–6 hr embryos (SRX246408), 8–10 hr embryos (SRX246409), and 14–16 hr embryos (SRX246412).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Elav regulates Dscam1 long 3′ UTR (Dscam1-L) biogenesis

Long-read sequencing reveals connectivity of long 3′ UTR to skipping of upstream exon 19

Loss of Dscam1-L impairs axon outgrowth

Dscam1 long 3′ UTR is required for correct splicing of exon 19

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Dr. Tzumin Lee for providing Dscam1 shRNA lines and the Dscam1 antibodies. Thanks to Dr. Kelly Phelps and Dr. Ian Wallace for guidance in preparing purified Elav protein. Thanks to Dr. Valérie Hilgers for sharing RIP qRT-PCR primer sequences. Thanks to Dr. Eric Lai for several plasmid constructs and Drosophila lines (see Key Resources Table). Thanks to members of the Miura lab for insights and discussion, and to Dr. Hannah Gruner, Dr. Daphne Cooper, and Bong Min Bae for reading and editing of the manuscript. Thanks to Dr. Lee Dyer, Dr. Thomas Kidd, and Dr. Benoit Bruneau for faculty mentorship of P.M. This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) (grant number P20 GM103650) and the National Science Foundation (grant number IOS-1656463). T.K. was also supported by NIGMS (grant number P20 GM103554). UNR Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting/Flow Cytometry Shared Resource Laboratory was supported by NIGMS (grant number P30 GM110767).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j. celrep.2019.05.083.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- An JJ, Gharami K, Liao GY, Woo NH, Lau AG, Vanevski F, Torre ER, Jones KR, Feng Y, Lu B, and Xu B (2008). Distinct role of long 3′ UTR BDNF mRNA in spine morphology and synaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Cell 134, 175–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassi C, Zimmermann C, Mitter R, Fusco S, De Vita S, Saiardi A, and Riccio A (2010). An NGF-responsive element targets myo-inositol monophosphatase-1 mRNA to sympathetic neuron axons. Nat. Neurosci 13, 291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anvar SY, Allard G, Tseng E, Sheynkman GM, de Klerk E, Vermaat M, Yin RH, Johansson HE, Ariyurek Y, den Dunnen JT, et al. (2018). Fulllength mRNA sequencing uncovers a widespread coupling between transcription initiation and mRNA processing. Genome Biol. 19, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger C, Renner S, Lüer K, and Technau GM (2007). The commonly used marker ELAV is transiently expressed in neuroblasts and glial cells in the Drosophila embryonic CNS. Dev. Dyn 236, 3562–3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair JD, Hockemeyer D, Doudna JA, Bateup HS, and Floor SN (2017). Widespread Translational Remodeling during Human Neuronal Differentiation. Cell Rep 21, 2005–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolisetty MT, Rajadinakaran G, and Graveley BR (2015). Determining exon connectivity in complex mRNAs by nanopore sequencing. Genome Biol. 16, 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JB, Boley N, Eisman R, May GE, Stoiber MH, Duff MO, Booth BW, Wen J, Park S, Suzuki AM, et al. (2014). Diversity and dynamics of the Drosophila transcriptome. Nature 512, 393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioni JM, Koppers M, and Holt CE (2018). Molecular control of local translation in axon development and maintenance. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 51, 86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascenco D, Erfurth ML, Izadifar A, Song M, Sachse S, Bortnick R, Urwyler O, Petrovic M, Ayaz D, He H, et al. (2015). Slit and Receptor Tyrosine Phosphatase 69D Confer Spatial Specificity to Axon Branching via Dscam1. Cell 162, 1140–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins T, Zinn K, McAllister L, Hoffmann FM, and Goodman CS (1990). Genetic analysis of a Drosophila neural cell adhesion molecule: interaction of fasciclin I and Abelson tyrosine kinase mutations. Cell 60, 565–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández MP, Berni J, and Ceriani MF (2008). Circadian remodeling of neuronal circuits involved in rhythmic behavior. PLoS Biol. 6, e69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawande B, Robida MD, Rahn A, and Singh R (2006). Drosophila Sex-lethal protein mediates polyadenylation switching in the female germline. EMBO J. 25, 1263–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glock C, Heumüller M, and Schuman EM (2017). mRNA transport & local translation in neurons. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 45, 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruner H, Cortés-όpez M, Cooper DA, Bauer M, and Miura P (2016). CircRNA accumulation in the aging mouse brain. Sci. Rep 6, 38907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgers V, Lemke SB, and Levine M (2012). ELAV mediates 3′ UTR extension in the Drosophila nervous system. Genes Dev. 26, 2259–2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoque M, Ji Z, Zheng D, Luo W, Li W, You B, Park JY, Yehia G, and Tian B (2013). Analysis of alternative cleavage and polyadenylation by 3′ region extraction and deep sequencing. Nat. Methods 10, 133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, Bortnick R, Tsubouchi A, Bäumer P, Kondo M, Uemura T, and Schmucker D (2007). Homophilic Dscam interactions control complex dendrite morphogenesis. Neuron 54, 417–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Wang X, Coolon R, and Ye B (2013). Dscam expression levels determine presynaptic arbor sizes in Drosophila sensory neurons. Neuron 78, 827–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocabas A, Duarte T, Kumar S, and Hynes MA (2015). Widespread Differential Expression of Coding Region and 3′ UTR Sequences in Neurons and Other Tissues. Neuron 88, 1149–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuklin EA, Alkins S, Bakthavachalu B, Genco MC, Sudhakaran I, Raghavan KV, Ramaswami M, and Griffith LC (2017). The Long 3’UTR mRNA of CaMKII Is Essential for Translation-Dependent Plasticity of Spontaneous Release in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Neurosci 37, 10554–10566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lianoglou S, Garg V, Yang JL, Leslie CS, and Mayr C (2013). Ubiquitously transcribed genes use alternative polyadenylation to achieve tissue-specific expression. Genes Dev. 27, 2380–2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao GY, An JJ, Gharami K, Waterhouse EG, Vanevski F, Jones KR, and Xu B (2012). Dendritically targeted Bdnf mRNA is essential for energy balance and response to leptin. Nat. Med 18, 564–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malka Y, Steiman-Shimony A, Rosenthal E, Argaman L, Cohen-Daniel L, Arbib E, Margalit H, Kaplan T, and Berger M (2017). Post-transcriptional 3′-UTR cleavage of mRNA transcripts generates thousands of stable uncapped autonomous RNA fragments. Nat. Commun 8, 2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield KD, and Keene JD (2012). Neuron-specific ELAV/Hu proteins suppress HuR mRNA during neuronal differentiation by alternative polyadenylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 2734–2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews BJ, Kim ME, Flanagan JJ, Hattori D, Clemens JC, Zipursky SL, and Grueber WB (2007). Dendrite self-avoidance is controlled by Dscam. Cell 129, 593–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura P, Shenker S, Andreu-Agullo C, Westholm JO, and Lai EC (2013). Widespread and extensive lengthening of 3′ UTRs in the mammalian brain. Genome Res. 23, 812–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura P, Sanfilippo P, Shenker S, and Lai EC (2014). Alternative polyadenylation in the nervous system: to what lengths will 3′ UTR extensions take us? BioEssays 36, 766–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi E, Sugino K, Kula E, Okazaki E, Tachibana T, Nelson S, and Rosbash M (2010). Dissecting differential gene expression within the circadian neuronal circuit of Drosophila. Nat. Neurosci 13, 60–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oktaba K, Zhang W, Lotz TS, Jun DJ, Lemke SB, Ng SP, Esposito E, Levine M, and Hilgers V (2015). ELAV links paused Pol II to alternative polyadenylation in the Drosophila nervous system. Mol. Cell 57, 341–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer BD, Ngo TT, Hibbard KL, Murphy C, Jenett A, Truman JW, and Rubin GM (2010). Refinement of tools for targeted gene expression in Drosophila. Genetics 186, 735–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramskӧld D, Wang ET, Burge CB, and Sandberg R (2009). An abundance of ubiquitously expressed genes revealed by tissue transcriptome sequence data. PLoS Comput. Biol 5, e1000598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanfilippo P, Wen J, and Lai EC (2017). Landscape and evolution of tissue-specific alternative polyadenylation across Drosophila species. Genome Biol. 18, 229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya MR, Wojtowicz WM, Andre I, Qian B, Wu W, Baker D, Eisenberg D, and Zipursky SL (2008). A double S shape provides the structural basis for the extraordinary binding specificity of Dscam isoforms. Cell 134, 1007–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmucker D, and Chen B (2009). Dscam and DSCAM: complex genes in simple animals, complex animals yet simple genes. Genes Dev. 23, 147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmucker D, Clemens JC, Shu H, Worby CA, Xiao J, Muda M, Dixon JE, and Zipursky SL (2000). Drosophila Dscam is an axon guidance receptor exhibiting extraordinary molecular diversity. Cell 101, 671–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simionato E, Barrios N, Duloquin L, Boissonneau E, Lecorre P, and Agnès F (2007). The Drosophila RNA-binding protein ELAV is required for commissural axon midline crossing via control of commissureless mRNA expression in neurons. Dev. Biol 301, 166–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivachenko A, Li Y, Abruzzi KC, and Rosbash M (2013). The transcription factor Mef2 links the Drosophila core clock to Fas2, neuronal morphology, and circadian behavior. Neuron 79, 281–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smibert P, Miura P, Westholm JO, Shenker S, May G, Duff MO, Zhang D, Eads BD, Carlson J, Brown JB, et al. (2012). Global patterns of tissue-specific alternative polyadenylation in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 1, 277–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soller M, and White K (2003). ELAV inhibits 3′-end processing to promote neural splicing of ewg pre-mRNA. Genes Dev. 17, 2526–2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorvaldsdόttir H, Robinson JT, and Mesirov JP (2013). Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief. Bioinform 14, 178–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian B, and Manley JL (2017). Alternative polyadenylation of mRNA precursors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 18, 18–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulitsky I, Shkumatava A, Jan CH, Subtelny AO, Koppstein D, Bell GW, Sive H, and Bartel DP (2012). Extensive alternative polyadenylation during zebrafish development. Genome Res. 22, 2054–2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zugates CT, Liang IH, Lee CH, and Lee T (2002). Drosophila Dscam is required for divergent segregation of sister branches and suppresses ectopic bifurcation of axons. Neuron 33, 559–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu HH, Yang JS, Wang J, Huang Y, and Lee T (2009). Endodomain diversity in the Drosophila Dscam and its roles in neuronal morphogenesis. J. Neurosci 29, 1904–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaharieva E, Haussmann IU, Bräuer U, and Soller M (2015). Concentration and Localization of Coexpressed ELAV/Hu Proteins Control Specificity of mRNA Processing. Mol. Cell. Biol 35, 3104–3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Zhou HL, Hasman RA, and Lou H (2007). Hu proteins regulate polyadenylation by blocking sites containing U-rich sequences. J. Biol. Chem 282, 2203–2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]