Abstract

Background

The United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include reducing the global maternal mortality rate to less than 70 per 100,000 live births and ending preventable deaths of newborns and children under five years of age, in every country, by 2030. Maternal and perinatal death audit and review is widely recommended as an intervention to reduce maternal and perinatal mortality, and to improve quality of care, and could be key to attaining the SDGs. However, there is uncertainty over the most cost‐effective way of auditing and reviewing deaths: community‐based audit (verbal and social autopsy), facility‐based audits (significant event analysis (SEA)) or a combination of both (confidential enquiry).

Objectives

To assess the impact and cost‐effectiveness of different types of death audits and reviews in reducing maternal, perinatal and child mortality.

Search methods

We searched the following from inception to 16 January 2019: CENTRAL, Ovid MEDLINE, Embase OvidSP, and five other databases. We identified ongoing studies using ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and searched reference lists of included articles.

Selection criteria

Cluster‐randomised trials, cluster non‐randomised trials, controlled before‐and‐after studies and interrupted time series studies of any form of death audit or review that involved reviewing individual cases of maternal, perinatal or child deaths, identifying avoidable factors, and making recommendations. To be included in the review, a study needed to report at least one of the following outcomes: perinatal mortality rate; stillbirth rate; neonatal mortality rate; mortality rate in children under five years of age or maternal mortality rate.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) group methodological procedures. Two review authors independently extracted data, assessed risk of bias and assessed the certainty of the evidence using GRADE. We planned to perform a meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model but included studies were not homogeneous enough to make pooling their results meaningful.

Main results

We included two cluster‐randomised trials. Both introduced death review and audit as part of a multicomponent intervention, and compared this to current care. The QUARITE study (QUAlity of care, RIsk management, and TEchnology) concerned maternal death reviews in hospitals in West Africa, which had very high maternal and perinatal mortality rates. In contrast, the OPERA trial studied perinatal morbidity/mortality conferences (MMCs) in maternity units in France, which already had very low perinatal mortality rates at baseline.

The OPERA intervention in France started with an outreach visit to brief obstetricians, midwives and anaesthetists on the national guidelines on morbidity/mortality case management, and was followed by a series of perinatal MMCs. Half of the intervention units were randomised to receive additional support from a clinical psychologist during these meetings. The OPERA intervention may make little or no difference to overall perinatal mortality (low certainty evidence), however we are uncertain about the effect of the intervention on perinatal mortality related to suboptimal care (very low certainty evidence).The intervention probably reduces perinatal morbidity related to suboptimal care (unadjusted odds ratio (OR) 0.62, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.40 to 0.95; 165,353 births; moderate‐certainty evidence). The effect of the intervention on stillbirth rate, neonatal mortality, mortality rate in children under five years of age, maternal mortality or adverse effects was not reported.

The QUARITE intervention in West Africa focused on training leaders of hospital obstetric teams using the ALARM (Advances in Labour And Risk Management) course, which included one day of training about conducting maternal death reviews. The leaders returned to their hospitals, established a multidisciplinary committee and started auditing maternal deaths, with the support of external facilitators. The intervention probably reduces inpatient maternal deaths (adjusted OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.98; 191,167 deliveries; moderate certainty evidence) and probably also reduces inpatient neonatal mortality within 24 hours following birth (adjusted OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.90; moderate certainty evidence). However, QUARITE probably makes little or no difference to the inpatient stillbirth rate (moderate certainty evidence) and may make little or no difference to the inpatient neonatal mortality rate after 24 hours, although the 95% confidence interval includes both benefit and harm (low certainty evidence). The QUARITE intervention probably increases the percent of women receiving high quality of care (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.35 ‐ 2.57, moderate‐certainty evidence). The effect of the intervention on perinatal mortality, mortality rate in children under five years of age, or adverse effects was not reported.

We did not find any studies that evaluated child death audit and review or community‐based death reviews or costs.

Authors' conclusions

A complex intervention including maternal death audit and review, as well as development of local leadership and training, probably reduces inpatient maternal mortality in low‐income country district hospitals, and probably slightly improves quality of care. Perinatal death audit and review, as part of a complex intervention with training, probably improves quality of care, as measured by perinatal morbidity related to suboptimal care, in a high‐income setting where mortality was already very low.

The WHO recommends that maternal and perinatal death reviews should be conducted in all hospitals globally. However, conducting death reviews in isolation may not be sufficient to achieve the reductions in mortality observed in the QUARITE trial. This review suggests that maternal death audit and review may need to be implemented as part of an intervention package which also includes elements such as training of a leading doctor and midwife in each hospital, annual recertification, and quarterly outreach visits by external facilitators to provide supervision and mentorship. The same may also apply to perinatal and child death reviews. More operational research is needed on the most cost‐effective ways of implementing maternal, perinatal and paediatric death reviews in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Plain language summary

Reviewing deaths to prevent mothers and children from dying in the future

What was the aim of this review?

This Cochrane Review aimed to assess if 'death audits and reviews' (exploring why people have died and what could have been done to prevent these deaths) can prevent mothers and children from dying. The review authors collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question and found two studies.

Key messages

In a study from West African hospitals, where death rates among women and babies were high, reviewing deaths probably led to fewer deaths among pregnant women, new mothers and newborn babies. In French hospitals, where death rates among babies were low, it may have made little or no difference to death rates among newborn babies .

What did the review study?

Every year, millions of babies and children die. Many women also die while they are pregnant or giving birth, or shortly afterwards. More than half of these deaths happen in sub‐Saharan Africa.

In many settings, health facilities or communities carry out 'death audits and reviews'. Here, people explore why a person died, what could have been done to avoid this death and what could be done better in the future.

Death audits and reviews could potentially help improve the quality of care and prevent new deaths among mothers and children. But they could also cost money, be based on wrong information and take health workers away from other important tasks. If they are done badly, they could also make health workers feel blamed and humiliated, which could lead to poorer care. We need to find out if audits and reviews work and which approach works best.

The review authors searched for studies where people from health facilities or the community carried out audits or reviews of deaths of pregnant women, women who had recently given birth, newborn babies or children under five years of age. The studies had to compare places or times where death audits and reviews were used to places or times where they were not.

What were the main results of the review?

The review authors found two relevant studies. Both studies assessed death audits at health facilities.

The first study took place in West African hospitals with high death rates among women and babies. In this study, doctors and midwives were given extra training in pregnancy and childbirth care. This included one day of training in how to carry out death audits of women who had died during pregnancy or childbirth. They then returned to their hospitals and held audits at monthly meetings, with support from an expert from a different hospital. These hospitals were compared to hospitals without the training and audit meetings. For mothers and babies who were in hospital, this approach:

‐ probably led to fewer pregnant women and new mothers dying, and probably led to slightly better care for mothers;

‐ probably led to fewer babies dying during the first 24 hours. However, it may have made no difference to the number of babies who died after their first 24 hours, although the range where the actual effect may be (the "margin of error") includes both an increase and a decrease in the number of babies who died.

‐ probably made no difference to the number of stillbirths.

The second study took place in French hospitals that already had very few deaths among newborns. In this study, doctors and midwives were given information about pregnancy and childbirth guidelines. They then held audit meetings in their hospitals where they discussed stillbirths and newborn babies who had become sick or died. These hospitals were compared to hospitals without the information and the meetings. This approach:

‐ may have made little or no difference to the number of babies who died during their first week

‐ probably reduced the number of babies who were sick because they received poor quality care.

We don't know what the effect was on stillbirths or on the number of mothers or older babies and children who died because the study did not measure this.

How up‐to‐date was this review?

The review authors searched for studies that had been published up to 16 January 2019.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

The United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals include reducing the global maternal mortality rate to fewer than 70 per 100,000 live births and ending preventable deaths of newborns and children under five years of age. All countries aim to reduce neonatal mortality to at least 12 per 1000 live births and mortality in children aged less than five years to at least 25 per 1000 live births, by 2030 (UN 2017). Although progress is being made towards achieving these goals, it is not fast enough, especially in low‐income countries (Wang 2014; WHO 2014). The absolute numbers and rates of maternal, child and perinatal deaths are higher in Africa than in any other region. In 2015, there were an estimated 303,000 maternal deaths globally, 99% of which were in low‐ and middle‐income countries, and 66% in sub‐Saharan Africa alone (WHO 2015). In 2016, there were an estimated 5,642,000 child deaths globally, more than half of which occurred in sub‐Saharan Africa (UNICEF 2017).

For this review, we used the following definitions.

'Maternal mortality': death of a woman during pregnancy or within 42 days of delivery or termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes (WHO 2004).

'Perinatal mortality': stillbirth or death of a newborn baby within the first seven days of life (WHO 2006).

'Neonatal mortality': death of a newborn baby at any time from birth to 28 days (WHO 2006).

'Child mortality': death of a child under the age of five years (UNICEF 2015).

Maternal mortality ratio: number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births (UNICEF 2015; WHO 2014).

Perinatal mortality rate: number of stillbirths and deaths in the first week of life per 1000 total births (WHO 2006).

Neonatal mortality rate: number of babies who die from 0 to 28 days per 1000 live births (WHO 2006).

Child mortality rate: number of deaths in children under age five years per 1000 live births (WHO 2006).

There is some overlap between the 'perinatal' and 'neonatal' categories, which both include babies aged zero to seven days, and between the 'neonatal' and 'child' categories, which both include babies aged zero to 28 days.

Description of the intervention

'Death audit and review' is a broad term intended to include every different method of reviewing deaths, that not only identifies the medical cause of death, but also attempts to identify avoidable factors that contributed to the death and make recommendations for avoiding such deaths in the future. The principal methods used are community‐based audit (verbal and social autopsy), facility‐based audits such as significant event analysis (SEA) or morbidity and mortality conferences (MMCs), and a combination of both (e.g. through a 'confidential enquiry').

In low‐income countries without comprehensive death registration, deaths in the community are often investigated using verbal autopsy. The family of the deceased is interviewed according to a standard questionnaire (developed by WHO 2007), and the information is then interpreted by physicians or by a computer to ascertain the most likely medical cause of death (Waiswa 2010). However, there is usually no attempt to identify avoidable factors as it is assumed that it is already known which interventions are needed to tackle each disease. Verbal autopsy has been incorporated into wider health and demographic surveillance strategies (Adazu 2005), although its accuracy has been questioned due to the non‐specific nature of signs and symptoms that may not be easily observed or remembered at interview (Butler 2010; Sloan 2001; Waiswa 2010). Social autopsy was designed as an add‐on to verbal autopsy, and indeed the two are sometimes combined as a 'verbal and social autopsy' (VASA) (Kalter 2011). The aim is to make a 'social diagnosis', identifying avoidable factors prior to death in the home, community and within health facilities at different stages of the patient pathway (e.g. parents do not recognise the severity of the illness; parents delay seeking care or seek care from an inappropriate provider; there are delays in reaching the health facility because of transport problems; after arriving at the facility the patient does not receive adequate treatment or has to wait excessively). In India, this has been used in a participatory manner, which has been termed social audit for community action (SACA) (Nandan 2005). In this method, the community is asked to identify causes of death and avoidable factors. In this review, we included combined VASA studies, but not stand‐alone verbal autopsy (whether conducted by a physician or a computer) with the intention of only identifying the medical cause of death.

Death audits in health facilities are usually based on MMCs or SEA. Cases are usually discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting (Hussein 2007). After discussing the details of the case, health workers identify avoidable factors and learning needs, and propose actions to be taken and changes to be made. The process does not intend to place blame, but the names of staff involved are not kept confidential. Indeed it is argued that "non‐confidential straightforwardness and open‐mindedness" are vital for a successful strategy (Supratikto 2002). A similar process occurs in 'mortality meetings', 'root cause analysis' meetings and, indeed, 'serious case reviews' (in child protection cases). Most mortality meetings take place at secondary healthcare facilities, drawing upon medical records to identify the diagnosis and key management interventions. Severe morbidity or near‐miss reviews are similarly used to learn lessons; these examine cases in which an individual almost died. In the UK, participation in SEAs are an important part of revalidation for doctors, and the Royal College of General Practitioners recommends that "SEA team discussions should be a routine part of your practice's quality improvement and clinical governance" (RCGP 2014).

Confidential enquiry is the most comprehensive method by which to investigate deaths. It considers the diagnosis and treatment in health facilities, and the entire course of an illness and treatment‐seeking pathway, identifying avoidable factors and recommending changes at every level of the health and social care system and beyond, in order to prevent future deaths. This is particularly important in low‐income countries where the majority of child deaths occur outside of health facilities (Breman 2001). A key feature of such enquiries is that the names of the individuals and any health workers involved are kept confidential, so that blame is avoided. These enquiries were pioneered in high‐income countries, based entirely on written (usually medical) records examined by a multidisciplinary panel of experts, which includes health workers and other professionals such as social services and the police (Lewis 2011; Pearson 2008a). Such confidential enquiries have been useful for evaluating gaps in health care in the UK (Pearson 2008a; WHO 2004), but are not yet widely used in low‐income countries (Hussein 2007). The expert analysis involves both quantitative and qualitative elements. In the UK, all the included deaths are analysed quantitatively for basic information such as age, sex, socioeconomic status, location of death, time (seasonality) of death and cause of death. Further detailed investigations are carried out on all maternal deaths and a subset of child deaths. A multidisciplinary panel reviews each of these cases and identifies avoidable factors. These are analysed thematically, illustrated by cases, and were used to generate recommendations as to how deaths might be avoided in the future (Pearson 2008b; Knight 2019).

How the intervention might work

Participation by communities in death audits is a strong basis for collective action to reduce mortality. In health facilities, significant event audit is a potentially powerful intervention to enable staff to learn from their mistakes and to institute important changes to procedures within their institution; the key mechanism is believed to be recommendation, followed by implementation of the proposed solutions (Pattinson 2009). The confidential enquiry approach is designed to identify avoidable factors at every step of the treatment‐seeking pathway, and to make recommendations to improve the health system and to address avoidable factors outside of health facilities. Case review meetings, followed by the dissemination of recommendations to health workers, communities, or both, are essentially aiming to change clinician and patient behaviour.

Although there are many frameworks for classifying behaviour change interventions, the only comprehensive and conceptually coherent one is the 'theoretical domains framework', which consists of 14 domains (Cane 2012; Michie 2014). Many of these domains are addressed by death audit and review. Those participating in the death review meetings gain knowledge about avoidable factors. The recommendations often set goals, and progress towards these can be audited. Repetition of similar recommendations may help clinicians to recall guidelines, whereas social pressure may encourage better adherence. Death review meetings may also change health workers' beliefs about the consequences of their actions: the knowledge that deaths will be investigated and reviewed may motivate them to avoid poor practice. Discussing deaths, especially of mothers and children, often evokes an emotional response, which usually motivates health workers and parents to do all they can to prevent such deaths.

Death reviews may conceivably have some adverse effects. First, there is a cost (time and financial) to conducting death reviews. In the community, field workers need to be employed to investigate cases. In health facilities, staff are taken away from frontline duties to review cases, which may have an adverse impact on the delivery of care. It has been argued that these resources should instead be spent directly on implementing interventions that are known to be effective (Koblinsky 2017). Second, if death reviews are not handled sensitively, they may lead to blaming, humiliation and demotivation of staff, which may in turn lead to poorer quality of care. Third, focus on only one level of care (such as a district hospital) may lead to the diversion of resources away from other levels of care (such as primary care facilities). Fourth, there is the potential for errors – reviews based on indirect information (especially at the community level) may be incomplete or inadequate at diagnosing the likely cause of death, because the information available may be insufficient or inaccurate (or both), or the people discussing the cases may be inexperienced, or a combination of these.

Why it is important to do this review

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that health facilities should conduct maternal and perinatal death reviews (MPDRs) (WHO 2013; WHO 2016). In general, there is an underlying assumption that death reviews are useful and will impact on mortality but there is little robust evidence to support this (Pattinson 2005). It would be useful for policy‐makers to understand which type of death review has the greatest impact on maternal, perinatal and child death rates, and what the essential features of an effective death review process are. Although confidential enquiry seems to be the most comprehensive method for addressing a wide range of avoidable factors, and hence has the potential for the greatest impact, it is unclear whether it could be adapted, whether it would be feasible or whether it would be effective in reducing mortality in low‐income countries. There is no comprehensive systematic review in the literature examining the impact of these methods of investigating deaths.

Objectives

To assess the impact and cost‐effectiveness of different types of death audits and reviews in reducing maternal, perinatal and child mortality.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included cluster randomised trials. However, as these are expensive and difficult to conduct, and large sample sizes are needed to measure impact on mortality, we anticipated that we would find very few. Therefore, we also included cluster non‐randomised trials, studies with a step‐wedge design, controlled before‐and‐after studies and interrupted time series studies.

For cluster randomised trials, cluster non‐randomised trials and controlled before‐and‐after studies, we used the EPOC criteria (EPOC 2017a), and excluded studies with only one intervention or control site. For interrupted time series studies, we excluded studies that did not have a clearly defined point in time when the intervention occurred and at least three data points before and three after the intervention.

Types of participants

Participants receiving the intervention (audits and reviews of maternal, perinatal or child deaths) could be involved with health facilities of any level or the wider community, such as subdistricts or districts, or both. Participants who should benefit from the intervention were pregnant women giving birth, their neonates and their children under five years old at the study sites during the study period in which the outcomes are measured.

Types of interventions

We included any form of death audit or review that involved studying individual cases of maternal, perinatal or child deaths, identifying avoidable factors and making recommendations. We classified the interventions as verbal and social autopsy, facility‐based death audit and SEA, or confidential enquiry. We excluded verbal autopsy studies that evaluated only causes of death and not avoidable factors. We included studies of maternal, perinatal, newborn and child deaths, alone or in combination. We excluded severe morbidity or near‐miss reviews. We included comparisons of the same population before introduction of the death review, or other comparable communities in which the death review was not implemented.

Types of outcome measures

We planned to include studies in the review irrespective of whether measured outcome data were reported in a 'usable' way.

Main outcomes

To be included in the review, a study needed to report at least one of the following outcomes:

perinatal mortality rate;

stillbirth rate;

neonatal mortality rate;

mortality rate in children under five years of age;

maternal mortality rate.

Secondary outcomes

For included studies, we also considered other outcomes:

outcomes relating to maternal severe morbidity, such as maternal near miss or as defined by study authors;

outcomes relating to quality of care in participating facilities;

perinatal morbidity related to suboptimal care;

cost per death averted.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases from database inception to 16 January 2019:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; in the Cochrane Library; 2019, Issue 1 of 12);

Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily, Ovid MEDLINE and Versions(R) (OvidSP; from 1946);

Embase (OvidSP; from 1974);

Global Health (OvidSP; from 1973);

Global Health Library – Regional Indexes, WHO; (www.globalhealthlibrary.net/php/index.php);

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED; in the Cochrane Library; 2015, Issue 2 of 4);

Popline, K4Health (www.popline.org/advancedsearch);

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature Host (CINAHL EBSCOHost; from 1982);

Science Citation Index & Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (Web of Science Core Collection, Thomson Reuters; from 1945).

There were no language or publication date limits. See Appendix 1 for search strategies.

Searching other resources

We identified ongoing studies through searches of ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/en/). We screened the reference lists of relevant articles found in these searches. We contacted experts in the field to advise us of unpublished or grey literature.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

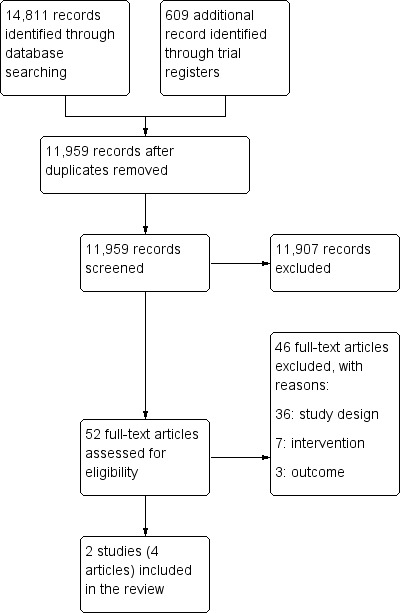

We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching to a reference management database and removed duplicates. Two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts for inclusion. We retrieved the full‐text study reports/publications and two review authors independently screened the full text, identified studies for inclusion and recorded the reasons for exclusion of ineligible studies. We resolved any disagreements through discussion and when required, we consulted a third review author. We listed studies that initially appeared to meet the inclusion criteria but were later excluded, together with reasons for exclusion, in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. We intended to provide any information we could obtain about ongoing studies. We recorded the selection process in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) (Liberati 2009) and the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

We used a standard data collection form, adapted from the Cochrane good practice data collection form, for study characteristics and outcome data. We piloted this on one study in the review.

Two review authors (MW, JP) independently extracted the following study characteristics from the included studies.

Methods: study design, number of study centres and location, study setting, withdrawals, date of study, follow‐up.

Participating health facilities: number, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, other relevant characteristics.

Interventions: intervention components, comparison, fidelity assessment.

Outcomes: main and other outcomes specified and collected, time points reported.

Notes: funding for trial, notable conflicts of interest of trial authors, ethical approval.

Two review authors (MW and JP) independently extracted outcome data from included studies. We noted in the Characteristics of included studies table whether outcome data were reported in an unusable way. We resolved disagreements by consensus.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (MW and JP) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), and the guidance from the EPOC group (EPOC 2017b). We contacted the authors of each study for clarification when the publication lacked clarity on whether a criterion was met. We resolved any disagreements by discussion. We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains.

Cluster randomised trial/cluster non‐randomised trial/controlled before‐and‐after study criteria:

random sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of participants and personnel;

blinding of outcome assessment;

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting;

baseline outcomes measurement;

baseline characteristics;

other bias.

We judged each potential source of bias as high, low or unclear, and provided a quote from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the 'Risk of bias' table. We summarised our 'Risk of bias' judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed. We considered blinding separately for different key outcomes where necessary (e.g. for unblinded outcome assessments, risk of bias for all‐cause mortality may be very different from a participant‐reported pain scale). Where information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with a trialist, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table. We did not exclude studies on the grounds of their risk of bias, but clearly reported the risk of bias when presenting the results of the studies.

When considering treatment effects, we took into account the risk of bias for the studies that contributed to that outcome.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted the review according to the published protocol (Willcox 2018), and reported any deviations from it in the Differences between protocol and review section.

Measures of treatment effect

We estimated the effect of the intervention using odds ratios (OR) for dichotomous data, together with the appropriate associated 95% confidence intervals (CI). For the Summary of Findings Tables, illustrative comparative risks were calculated using GRADEPro software.

We planned to estimate mean differences (for studies using the same scale) or standardised mean differences (for studies using different scales) for continuous data, together with the 95% appropriate associated CIs, but we found no studies reporting continuous data. For interrupted time series studies, we planned to estimate a standardised effect size for each study by dividing the level by the slope and the standard error by the standard deviation of the preintervention slope, but we found no interrupted time series studies.

Unit of analysis issues

For cluster randomised trials, we conducted the analysis at the same level as the allocation using a summary measure from each cluster.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to request missing data. We used intention‐to‐treat analyses by including all participants who were supposed to have received a particular intervention. We planned to perform sensitivity analyses by excluding studies with high rates of loss to follow‐up.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to assess statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis visually and using the I² and Chi² statistics, regarding heterogeneity as substantial if the I² statistic was greater than 60% or if there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. However, we performed no meta‐analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there were 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we planned to investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. However, only found two studies. We contacted authors to clarify points which were not explicit in their publications.

Data synthesis

While we planned to perform meta‐analysis following Cochrane and EPOC guidance (see the protocol for this review for full details; Willcox 2018), we judged that this was not possible and did not perform meta‐analyses. Therefore, we summarised results extracted from the included studies narratively.

Summary of findings

We summarised the findings of the main intervention comparison for the most important outcomes:

perinatal mortality rate;

stillbirth rate;

neonatal mortality rate;

mortality rate in children under five years of age;

maternal mortality rate;

outcomes relating to quality of care in participating facilities;

perinatal morbidity related to suboptimal care.

We present these in 'Summary of findings' tables to draw conclusions about the certainty of the evidence within the text of the review. Where a study presented a change in rates over time, we calculated the illustrative effect of the intervention by applying the adjusted odds ratio for the intervention to the rates observed in the control group at follow‐up, using GRADEpro software.

Two review authors independently assessed the certainty of the evidence (high, moderate, low or very low) using the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias). We used the methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and the EPOC worksheets (EPOC 2017c), and using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT). We resolved disagreements on certainty ratings by discussion, providing justification for decisions to downgrade or upgrade the ratings using footnotes in the table, and made comments to aid readers' understanding of the review where necessary. We used plain language statements to report these findings in the review.

As it was not possible to meta‐analyse the data, we summarised the results in the text.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses:

type of country (low‐ versus middle‐ versus high‐income, according to World Bank classification at the time of the study);

type of death review (verbal and social autopsy versus SEA versus confidential enquiry);

setting: facility‐based versus community‐based.

The following outcomes would be used in subgroup analysis:

perinatal mortality rate;

stillbirth rate;

neonatal mortality rate;

mortality rate in children under five years of age;

maternal mortality rate.

It was not possible to undertake these analyses due to the decision not to pool data across the included studies.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analysis defined a priori to assess the robustness of our conclusions and explore its impact on effect sizes. This was to involve:

restricting the analysis to published studies;

restricting the analysis to studies with a low risk of bias (i.e. high‐quality randomised trials).

It was not possible to undertake these analyses due to the decision not to pool data across the included studies.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We identified 11,959 articles from electronic and supplementary searches, after removing duplicates. We excluded 11,907 articles following a review of titles and abstracts and retrieved and assessed the full text of 52 articles (Figure 1). We excluded 46 full‐text articles; 36 of these did not meet our criteria for study design (most were uncontrolled before‐and‐after studies, see Table 4); seven did not include death review or audit as part of the intervention; and three did not measure impact on maternal, perinatal or child mortality. Two cluster‐randomised trials (one of them reported in three separate articles) met the inclusion criteria. We have presented the study flow diagram in Figure 1.

2. Uncontrolled before‐and‐after studies of death reviews.

| Study ID | Intervention description | Outcomes assessed | Country | Setting/s where implemented |

| Allanson 2015 | Perinatal Problem Identification Programme | Hospital‐based perinatal mortality | South Africa | 163 health facilities (29 community health centres, 105 district hospitals, 4 national central hospitals, 22 regional hospitals and 3 provincial tertiary hospitals) |

| Bugalho 1993 | In‐facility case review of perinatal deaths and maternal deaths | Hospital‐based perinatal mortality | Mozambique | 1 national referral hospital |

| Dumont 2006 | In‐facility case review of maternal deaths | Hospital‐based maternal mortality | Senegal | 1 district hospital |

| Eskes 2014 | In‐facility case review of term perinatal deaths | Perinatal mortality | Netherlands | 90 Dutch hospitals with obstetric/ paediatric departments |

| Gaunt 2010 | In‐facility case review of perinatal deaths | Hospital‐based perinatal mortality | South Africa | 1 district hospital |

| Kongnyuy 2008 | In‐facility case review of maternal deaths and criterion‐based clinical audit | Hospital‐based maternal mortality | Malawi | 13 hospitals and 60 health centres |

| Mbaruku 1995 | Retrospective case review of in‐facility maternal deaths 1984–1986, followed by prospective case reviews 1987–1991 | Hospital‐based maternal mortality | Tanzania | 1 regional referral hospital |

| Moodley 2014 | Confidential enquiry into maternal deaths | Maternal mortality | South Africa | National level |

| Mussell et al (unpublished ‐ reference in Pattinson 2009) | Perinatal Problem Identification Programme | Hospital‐based perinatal mortality | Bangladesh | 1 hospital |

| Nakibuuka 2012 | In‐facility case review of perinatal deaths | Hospital‐based perinatal mortality | Uganda | 1 private referral hospital |

| Okonofua 2017 | In‐facility case review of maternal deaths | Hospital‐based maternal mortality | Nigeria | 3 referral hospitals in Lagos |

| Papiernik 2000, Papiernik 2005 | In‐facility case review of perinatal deaths | Perinatal mortality | France | 17 private maternity units, 5 secondary care hospitals, 4 referral hospitals |

| Patrick 2007 | In‐facility case review of perinatal deaths: retrospective 1995–1996 and prospective 1996–2000 | Hospital‐based perinatal mortality | South Africa | 1 referral hospital |

| Pattinson 1995 | Perinatal Problem Identification Programme | Perinatal mortality | South Africa | 1 hospital |

| Pattinson 2006 | In‐facility case review of maternal deaths and severe acute maternal morbidity | Hospital‐based maternal mortality | South Africa | 2 district and 2 academic hospitals |

| Pattinson 2011 | Audit of perinatal deaths | Facility‐based perinatal mortality | South Africa | 6 midwife obstetric units, 24 district hospitals, 5 regional hospitals |

| Shrestha 2006 | Audit of perinatal deaths | Hospital‐based perinatal mortality | Nepal | 1 tertiary hospital |

| Stratulat 2012 | Confidential enquiry into perinatal deaths | Perinatal deaths among term newborns | Moldova | National level |

| Thomas 1985 | Confidential enquiry into perinatal deaths | Perinatal mortality | Wales | 1 county |

| van den Akker 2011 | In‐facility case review of maternal deaths and severe acute maternal morbidity | Maternal mortality | Malawi | 1 district hospital and 28 smaller health facilities |

| van Roosmalen 1989 | In‐facility case review of perinatal deaths and retrospective audit of stillbirths | Hospital‐based perinatal mortality | Tanzania | 1 district hospital |

| Ward 1995 | In‐facility case review and audit of perinatal deaths | Hospital‐based perinatal mortality | South Africa | 1 referral hospital |

| Wilkinson 1991 | In‐facility case review of perinatal deaths | Facility‐based perinatal mortality | South Africa | 1 district hospital + surrounding clinics |

| Wilkinson 1997 | Audit of perinatal deaths | Facility‐based perinatal mortality | South Africa | 1 district |

| Willcox 2018 | Community‐based confidential enquiry into child deaths | Under‐5 mortality | Uganda and Mali | 5 subdistricts/subcounties in each country |

Included studies

Only two studies (four articles) met all the inclusion criteria and are described in the Characteristics of included studies table (Dumont 2013; Dupont 2017). Both introduced death review and audit as part of a complex intervention, which had different components. The QUARITE study (QUAlity of care, RIsk management, and TEchnology) was conducted in hospitals in Mali and Senegal (Dumont 2013), which had very high maternal and perinatal mortality rates. The intervention focused on training leaders of obstetric teams in capital, regional and district hospitals using the ALARM (Advances in Labour And Risk Management) international course, which included one day about conducting maternal death reviews. The leaders then returned to their hospitals where they established a multidisciplinary committee and started auditing maternal deaths, with the support of external facilitators every quarter. In contrast, the OPERA trial was conducted in maternity units in France, which already had very low perinatal mortality rates at baseline (Dupont 2017). The intervention started with an outreach visit to brief obstetricians, midwives and anaesthetists on the national guidelines on morbidity/mortality case management, and was followed by a series of morbidity/mortality conferences (MMCs). Half of the intervention units were randomised to receive additional support from a clinical psychologist during these meetings.

Excluded studies

Twenty‐six of the excluded full‐text articles were uncontrolled before‐and‐after studies. Eight were excluded because they did not include participatory death review meetings.

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias of both trials (Dumont 2013; Dupont 2017). Because of the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind the participating health facilities or their staff, but patients were blinded to the allocation of the hospital they were attending in the QUARITE study (Dumont 2013). In both cases, the outcome assessors were blinded. Overall, the QUARITE trial had a low risk of bias whereas the OPERA trial had a moderate risk of bias.

Allocation

There was a low risk of selection bias in both studies because both used stratified randomisation to allocate health facilities to intervention or control groups. In the OPERA trial, the intervention and control groups had similar characteristics at baseline (Dupont 2017). In the QUARITE trial, there were some important differences between intervention and control groups at baseline, but these were accounted for in the analysis, which measured change in mortality rates from baseline (Dumont 2013).

Blinding

Blinding of health facilities and their staff was not possible due to the nature of the intervention. In the QUARITE trial, it is stated that patients were blinded to allocation of the facility (Dumont 2013). In both trials, the outcome assessors were blinded. In the OPERA trial, the outcome assessors had previously been involved in the mortality meetings, but because the outcomes were assessed from anonymised medical records one year after the meetings, and only a sample of cases were discussed at meetings, it is unlikely that the assessors would remember whether cases came from intervention or control hospitals, so we judged this at low risk of bias (Dupont 2017).

Incomplete outcome data

There was low risk of attrition bias in the QUARITE trial because no hospitals were lost to follow‐up (Dumont 2013). In the OPERA trial, 2/97 private hospitals withdrew, but this was prior to randomisation (low risk of attrition bias; Dupont 2017).

Selective reporting

The protocol of the QUARITE trial was published and the trial reported the outcomes specified in the protocol, so there was no selective reporting (Dumont 2013). The authors of the OPERA confirmed that there were no outcomes in the protocol which were not reported in the final trial report (Dupont 2017).

Other potential sources of bias

In the OPERA trial, six units randomised to the intervention group did not implement the intervention and were transferred to the control group. Therefore, the analysis was per protocol rather than intention to treat (Dupont 2017).

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Perinatal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including an educational outreach visit and morbidity/mortality conferences compared with no intervention.

| Perinatal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including an educational outreach visit and morbidity/mortality conferences compared with no intervention | ||||||

|

Patient or population: births Settings: maternity units in France Intervention: perinatal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including an educational outreach visit and morbidity/mortality conferences (OPERA trial) Comparison: no intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Results in words | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Comparison | With death reviews | |||||

|

Perinatal mortality rate (overall) (at month 12–26) |

4.7 stillbirths or deaths per 1000 total births | 4.9 stillbirths or deaths per 1000 total births (from 4 to 6 stillbirths or deaths per 1000) |

OR 1.05 (0.91 to 1.21) |

95 maternity units, 165353 births (1 studya) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | The intervention may make little or no difference to perinatal mortality. |

|

Proportion of perinatal deaths related to suboptimal carec (at months 12–26) |

85 per 1000 stillbirths or deaths whose quality of care could be scored | 90 per 1000 stillbirths or deaths whose quality of care could be scored (from 49 to 181 stillbirths or deaths per 1000) |

OR 1.14 (0.55 to 2.37) |

95 maternity units, 759 stillbirths or deaths whose quality of care could be scored (1 studya) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ Very Low | We are uncertain about the effect of the intervention on perinatal mortality related to suboptimal care |

| Stillbirth rate | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Neonatal mortality rate | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Mortality rate in children < 5 years of age | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Maternal mortality rate | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

|

Proportion of perinatal morbidity cases related to suboptimal carec (at months 12–26) |

115 per 1000 morbidity cases whose quality of care could be scored | 76 per 1000 morbidity cases whose quality of care could be scored (from 49 to 110 per 1000 morbidity cases) |

OR 0.62 (0.40 to 0.95) |

95 maternity units, 1640 cases of morbidity whose quality of care could be scored (1 studya) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatee | The intervention probably reduces perinatal morbidity related to suboptimal care. |

| Adverse effects | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDupont 2017 (cluster randomised trial). bDowngraded two levels due to limitations in study design and execution and imprecise estimate. The 95% CI included both slight harm and appreciable benefit. c The proportion here refers to the proportion of cases related to suboptimal care.

dDowngraded three levels due to limitations in study design and very imprecise estimate. The 95% CI included both appreciable harm and appreciable benefit. eDowngraded one level due to limitations in study design and execution.

Summary of findings 2. Maternal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including the ALARM course and training audit committees compared with no intervention.

| Maternal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including the ALARM course and training audit committees compared with no intervention | ||||||

|

Patient or population: mothers delivering in the hospitals Settings: district and regional referral hospitals in West Africa Intervention: complex intervention to develop local leadership and empower obstetric teams to conduct maternal death audits (QUARITE trial) Comparison: no intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects*f | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Results in words | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| With no intervention | With death reviews | |||||

| Perinatal mortality rate | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Inpatient stillbirth rate | 94 stillbirths per 1000 total births | 98 stillbirths per 1000 total births (from 86 to 112 stillbirths per 1000) |

AORa 1.05 (0.91 to 1.22) |

46 hospitals, 197,336 participants (1 studyb) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | The intervention probably makes little or no difference to inpatient stillbirth rate. |

| Inpatient neonatal mortality rate – before 24 hours | 11 neonatal deaths per 1000 live births | 8 neonatal deaths per 1000 live births (from 7 to 10 deaths per 1000) |

AORa 0.74 (0.61 to 0.90) |

46 hospitals, 197,336 participants (1 studyb) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | The intervention probably reduces inpatient neonatal mortality rate before 24 hours. |

| Inpatient neonatal mortality rate – after 24 hours | 2 neonatal deaths per 1000 live births | 2 neonatal deaths per 1000 live births (from 1 to 3 deaths per 1000) |

AORa 0.88 (0.62 to 1.24) |

46 hospitals, 197,336 participants (1 studyb) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd | The intervention may make little or no difference to inpatient neonatal mortality rate after 24 hours. However, the 95% confidence interval indicates that the intervention may reduce or increase inpatient neonatal mortality rate after 24 hours. |

| Mortality rate in children < 5 years of age | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Inpatient maternal mortality rate | 711 maternal deaths per 100000 pregnant women | 605 maternal deaths per 100000 pregnant women (from 520 to 697 deaths per 100000)g |

AORa 0.85 (0.73 to 0.98) |

46 hospitals, 197,336 participants (1 studyb) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | The intervention probably reduces inpatient maternal mortality. |

|

Quality of care (Proportion of women receiving high quality cared) |

298 women per 1000 pregnant women received high quality care | 442 women per 1000 pregnant women received high quality care (from 364 to 522 women per 1000) | OR 1.87 (1.35 ‐ 2.57) | 32 hospitals, 658 consecutive participants (1 studyb) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | The intervention probably increases the proportion of women receiving high quality of care. |

|

Quality of care for women with complications (Proportion of women with eclampsia or postpartum haemorrhage receiving high quality cared) |

377 women per 1000 pregnant women with complications received high quality care | 503 women per 1000 pregnant women with complications received high quality care (from 368 to 638 women per 1000) | OR 1.67 (0.96 ‐ 2.91) | 32 hospitals, 209 complicated participants (1 studyb) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowe | The intervention may increase the proportion of women with complications who receive high quality of care. However, the 95% confidence interval includes no effect. |

| Adverse effects | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AOR: adjusted odds ratio; CBCA: criterion‐based clinical audit; CI: confidence interval. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a Adjusted for the two stratification variables: hospital type and country, as well as for variables selected a priori as potential risk factors for hospital‐based mortality, including both (a) baseline (year 1) characteristics of hospitals (availability of adult intensive care unit, blood bank, anaesthetist, and gynaecologist‐obstetrician) and (b) characteristics of individual women (residence, age, parity, previous caesarean delivery, any pathology during pregnancy, prenatal visit attendance, multiple pregnancy, referral from another health facility, antepartum or postpartum haemorrhage, pre‐eclampsia or eclampsia, prolonged or obstructed labour, uterine rupture, and puerperal infection or sepsis).

bDumont 2013 (cluster randomised trial). Perinatal outcomes were assessed for singletons only, excluding multiple pregnancies from the analyses. cDowngraded one level for indirectness because this is based on a single study with a relatively small number of events. For a complex intervention such as this, the effect of the intervention may be modified by setting, or may work differently in a different setting.

dDefined as CBCA score of >70% eDowngraded two levels due to imprecision of the estimate, and for indirectness because this is based on a single study with a small number of events.

fThese anticipated absolute effects are based on the numbers of events and participants in the year 4 outcome assessment for the trial (see Table 3).

gNote that the denominator here is pregnant women and not the number of live births.

Comparison 1: Perinatal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including an educational outreach visit and morbidity/mortality conferences compared with no intervention

One included study (the OPERA trial) assessed a complex intervention to promote guidelines and MMCs compared with no intervention and reported perinatal mortality and quality of care (Dupont 2017). There were no data on stillbirth rate, neonatal mortality, mortality rate in children under five years of age, maternal mortality, maternal morbidity or cost effectiveness. No undesirable effects of the intervention were reported. (Table 1; Table 5).

3. Numbers of events and participants in the OPERA trial (Dupont 2017).

| Outcome | Comparison group | Intervention group | ||

| Number of events | Number of participants | Number of events | Number of participants | |

| Perinatal mortality rate (overall) | 448 | 95975 | 340 | 69378 |

| % of perinatal deaths related to suboptimal care | 37 | 435 | 29 | 324 |

| % of perinatal morbidity cases related to suboptimal care | 116 | 1007 | 48 | 633 |

Primary outcomes

Perinatal mortality

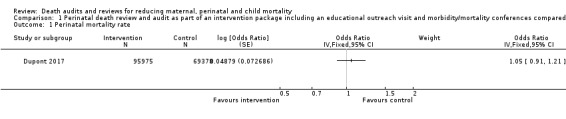

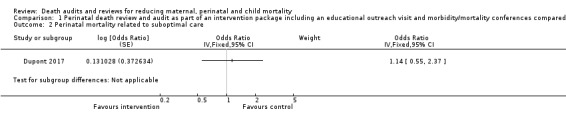

The intervention may have made little or no difference to overall perinatal mortality in this setting (OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.21; low certainty evidence). We are uncertain of the effect of the intervention on perinatal mortality specifically related to suboptimal care as the certainty of the evidence is very low (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.55 to 2.37; very low‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2) (Dupont 2017).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perinatal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including an educational outreach visit and morbidity/mortality conferences compared with no intervention, Outcome 1 Perinatal mortality rate.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perinatal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including an educational outreach visit and morbidity/mortality conferences compared with no intervention, Outcome 2 Perinatal mortality related to suboptimal care.

Secondary outcomes

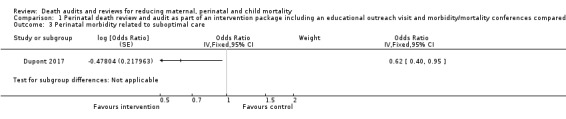

Perinatal morbidity related to suboptimal care

The OPERA intervention probably reduced perinatal morbidity which is specifically related to suboptimal care (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.95; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perinatal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including an educational outreach visit and morbidity/mortality conferences compared with no intervention, Outcome 3 Perinatal morbidity related to suboptimal care.

Comparison 2: Maternal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including the ALARM course and training audit committees compared with no intervention

One included study (the QUARITE trial) assessed a complex intervention to develop local leadership and empower obstetric teams to conduct maternal death reviews compared with no intervention. It reported maternal mortality, neonatal mortality, perinatal morbidity, stillbirths and quality of care (Dumont 2013). There were no data on perinatal mortality, mortality rate in children under five years of age, maternal morbidity or cost‐effectiveness. No undesirable effects of the intervention were reported. (Table 2; Table 3).

1. Number of events and participants in the QUARITE trial (Dumont 2013).

| Outcome | Comparison group | Intervention group | ||||||||||

| Baseline | Year 4 | Baseline | Year 4 | |||||||||

| Number of events | Number of participants | Rate | Number of events | Number of participants | Rate | Number of events | Number of participants | Rate | Number of events | Number of participants | Rate | |

| Inpatient stillbirth rate (per 1000 total births) | 3441 | 39992 | 86.0 | 4270 | 51324 | 83.2 (decreased by 2.8 stillbirths from baseline to year 4) |

3883 | 41368 | 93.9 | 4238 | 50426 | 84.0 (decreased by 9.9 stillbirths from baseline to year 4) |

| Inpatient neonatal mortality rate ‐ before 24 hours (per 1000 live births) | 332 | 36551 | 9.0 | 505 | 47054 | 10.7 (increased by 1.7 neonatal deaths from baseline to year 4) | 434 | 37485 | 11.6 | 446 | 46188 | 9.7 (decreased by 1.9 neonatal deaths from baseline to year 4) |

| Inpatient neonatal mortality rate ‐ after 24 hours (per 1000 live births) | 99 | 36551 | 2.7 | 99 | 47054 | 2.1 (decreased by 0.6 neonatal deaths from baseline to year 4) | 232 | 37485 | 6.2 | 185 | 46188 | 4.0 (decreased by 2.2 neonatal deaths from baseline to year 4) |

| Inpatient maternal mortality rate (per 100,000 pregnant women) | 337 | 41655 | 809 | 381 | 53581 | 711 (decreased by 98 maternal deaths from baseline to year 4) | 445 | 43269 | 1028 | 356 | 52662 | 676 (decreased by 352 maternal deaths from baseline to year 4) |

| Quality of care: Proportion of women receiving high quality care (per 1000 pregnant women) | ‐ | ‐ | 101 | 339 | 298 | ‐ | ‐ | 141 | 319 | 442 | ||

| Quality of care: Proportion of women with eclampsia or postpartum haemorrhage receiving high quality care (per 1000 pregnant women with complications) | ‐ | ‐ | 43 | 114 | 377 | ‐ | ‐ | 48 | 95 | 505 | ||

Primary outcomes

Stillbirths

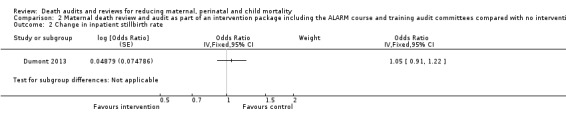

The QUARITE intervention probably made little or no difference to the inpatient stillbirth rate (adjusted OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.22; moderate certainty evidence; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Maternal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including the ALARM course and training audit committees compared with no intervention, Outcome 2 Change in inpatient stillbirth rate.

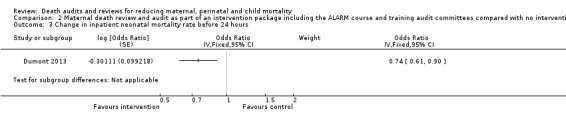

Neonatal mortality

The QUARITE intervention probably reduced inpatient neonatal mortality within 24 hours of birth (adjusted OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.90; moderate certainty evidence; Analysis 2.3). Neonatal mortality within 24 hours dropped in the study from 11.6 to 9.7 deaths per 1000 births in hospitals receiving the QUARITE intervention, compared to an increase from 9.0 to 10.7 deaths per 1000 births in the comparison hospitals (overall unadjusted reduction of 3.6 deaths per 1000 live births).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Maternal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including the ALARM course and training audit committees compared with no intervention, Outcome 3 Change in inpatient neonatal mortality rate before 24 hours.

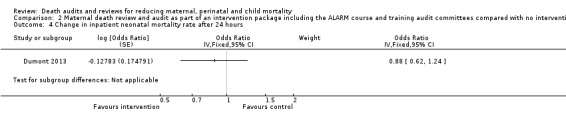

The intervention may have made little or no difference to inpatient neonatal mortality after 24 hours up to discharge. However, the 95% confidence interval indicates that the intervention may reduce or increase inpatient neonatal mortality rate after 24 hours (adjusted OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.24; low certainty evidence; Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Maternal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including the ALARM course and training audit committees compared with no intervention, Outcome 4 Change in inpatient neonatal mortality rate after 24 hours.

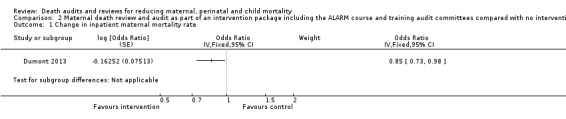

Maternal mortality

The QUARITE intervention probably reduced inpatient maternal mortality (adjusted OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.98; moderate certainty evidence; Analysis 2.1). The number of maternal deaths per 1000 women in the study went from 10.3 to 6.8 in hospitals receiving the QUARITE intervention, compared with a reduction from 8.1 to 7.1 per 1000 women in the comparison hospitals (overall reduction of 2.5 maternal deaths per 1000 women, 95% CI 0.9 to 4.2 deaths).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Maternal death review and audit as part of an intervention package including the ALARM course and training audit committees compared with no intervention, Outcome 1 Change in inpatient maternal mortality rate.

In subgroup analyses, the effect was larger in district hospitals (adjusted OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.77), but the intervention appeared to have had little or no effect in regional referral hospitals (adjusted OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.31). This may have been because of other interventions introduced during the study period in the regional referral hospitals in both the intervention and control sites (Dumont 2013). A further analysis showed that the effect of the intervention was larger for women delivering by caesarean section (adjusted OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.82) compared to women delivering vaginally (adjusted OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.11). The authors suggested this was because intrapartum caesarean delivery is associated with two‐ to six‐fold higher risks of hospital‐based maternal and neonatal mortality compared to spontaneous vaginal delivery, related to delays in seeking and receiving care, and so there is a greater potential to reduce mortality.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of care

The QUARITE intervention probably increases the proportion of women receiving high quality of care (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.35 ‐ 2.57; moderate‐certainty evidence). For women with eclampsia or postpartum haemorrhage the intervention may increase the proportion of women with complications who receive high quality of care. However, the 95% confidence interval includes no effect (OR 1.67, 95% CI 0.96 ‐ 2.91; low certainty evidence).

Quality of care was measured from medical records using criterion‐based clinical audit (CBCA), The audit tool included 26 unweighted criteria that measured 5 dimensions of care: patient history, clinical examination, laboratory examinations, labour management (partograph), delivery care and postpartum monitoring. These criteria were applied for all women. An additional 7 items were scored only for women with severe pre‐eclampsia/eclampsia and another 7 items only for women with postpartum haemorrhage. Each criterion was given one point and the overall score was calculated as a proportion of the relevant denominator (26 for women without severe complications, 33 for women with severe pre‐eclampsia / eclampsia or postpartum haemorrhage). "Good quality care" was defined as a score of 70% or higher. Further analyses of the CBCA tool showed that low scores (less than 70%) predict perinatal mortality, which indicates construct validity (Pirkle 2012). Therefore we chose to present this binary outcome.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review only identified two cluster‐randomised trials examining the effectiveness of death audit and review for reduction of maternal and perinatal mortality. There were many other studies of death audits and reviews, but none met the methodological criteria for inclusion in this review; almost all were uncontrolled before‐and‐after studies.

Both studies included death audits as the central component of a complex intervention, and these interventions were sufficiently different that we considered meta‐analysis not to be useful. Furthermore, the settings were very different: QUARITE was conducted in countries with very high levels of maternal and perinatal mortality, whereas OPERA was conducted in France, which has very low levels of maternal and perinatal mortality. This may explain why there was no reduction in overall mortality in the OPERA trial (low certainty evidence), since it was very low in both control and intervention groups. However, the intervention probably reduced perinatal morbidity related to suboptimal care (moderate certainty evidence). The QUARITE intervention probably reduced inpatient maternal mortality, especially in women delivering by caesarean section, and in district hospitals (moderate certainty evidence), and probably also increased the proportion of women receiving high quality of care (moderate certainty evidence).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Evidence from the QUARITE trial is likely applicable to maternal death audit and review in other low‐income countries, as the intervention is well described in the protocol and could be replicated elsewhere. Senegal and Mali are among the world's poorest countries, so if it was possible to achieve a reduction in maternal mortality there within three years of intervention, it should be possible in most similar countries (although some contextual differences may affect the impact – for example the financial and legal). However, it is hard to assess the applicability of this evidence in middle‐ and high‐income countries, where differences in the settings could modify the effect of the intervention.

The lack of impact on perinatal mortality in the OPERA trial can be explained by the already very low perinatal mortality rates in France. However, it did show that even in this relatively well‐resourced setting, quality of perinatal care can be improved. This evidence may be applicable to other high‐income countries with similar health system arrangements. We did not find any evidence on the effectiveness of perinatal death audit in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Although the QUARITE intervention may have made little or no difference to inpatient stillbirth rates or neonatal mortality rates after 24 hours, the intervention involved audit and review of only maternal deaths (not perinatal deaths). Therefore, one cannot draw any conclusions from the QUARITE trial about the effectiveness of reviewing perinatal, neonatal or child deaths. Furthermore, the review process for perinatal and child deaths is different to that for maternal deaths.

Both of the included studies evaluated complex interventions, including death reviews as the main component and also training. The effects shown may be partly due to these training components of the interventions. Another review has shown that continuing education meetings and workshops in general lead to a mean improvement in compliance with desired practice of 6% (interquartile range 1.8% to 15.9%) (Forsetlund 2009). However, there are almost no high‐quality randomised controlled trials evaluating the impact on maternal or perinatal mortality of continuing education or training courses in emergency obstetric care (Ameh 2019). While it is impossible to ascertain separately the effects of the training and death review components of the intervention in the included studies, the effect observed in West Africa could be considered to be larger than might have been expected from training alone. The training component may also have indirect positive effects – for example, training may facilitate the implementation of audit and feedback, which may be resisted by clinicians in settings where this is a novel practice. However, in order to confirm these ideas, it would be necessary to conduct a randomised controlled trial comparing training alone, versus training plus death reviews.

There are important gaps in the evidence. We found no studies of death audits or reviews in isolation, or of late neonatal or child deaths. We also found no studies of death audit or review outside of hospitals (e.g. investigating deaths in the community). In addition, we identified no eligible studies conducted in middle‐income countries or studies measuring cost‐effectiveness. Neither of the included studies reported measures of maternal severe morbidity or cost per death averted. Because of the very limited number of included studies, we were unable to conduct any of the subgroup analyses that we had planned.

It is likely that few comparative studies have been conducted because showing an impact on maternal mortality (or even perinatal mortality) requires a large number of hospitals and women to take part, which is difficult and expensive to run. It can also be challenging to find study sites where no other interventions are being implemented that could also have an impact on maternal and perinatal mortality. In addition, many funders assume that research on MPDR is not a priority because in many countries there already a government policy that MPDR should be conducted, and it is already recommended by WHO (WHO 2013; WHO 2016). This makes it difficult to find control areas where MPDR is not being conducted in some form. A survey in 2015 found that 56/62 (90%) of countries had a policy on maternal death review (Bandali 2016). Therefore we are in the process of conducting a systematic review of uncontrolled before‐and‐after studies.

Quality of the evidence

The certainty of the evidence ranged from very low to moderate for the outcomes considered in this review. For both studies, there were issues with blinding because it is not possible to blind hospitals to whether or not they received the intervention. However, it was possible to blind those analysing the outcomes and both trials did this. Although we assessed the QUARITE study to be at low risk of bias overall, the certainty of evidence for the second comparison was downgraded due to indirectness. This was because the results from the QUARITE study included in this comparison are from a limited range of settings with very high maternal and perinatal mortality rates. The effects of this complex intervention may be modified by setting, or may work differently in a different setting. The OPERA trial had only one other shortcoming, namely that it did not use intention‐to‐treat analysis. In a future update, we may attempt to apply an 'intention to treat' analysis to these data. Some of the results had wide CIs and it is therefore likely that further research would have an important impact on our confidence in the estimates of effect and may change the estimates, so the overall certainty of evidence was downgraded for this reason.

Potential biases in the review process

Our search strategy was designed to maximise sensitivity (detecting relevant research) at the expense of specificity (excluding irrelevant research). It is possible that some studies may have been missed if they were in the grey literature but we did consult widely with experts and all reports we found in the grey literature did not meet our methodological inclusion criteria. We conducted this review according to Cochrane standards.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Several other reviews have studied the effect of audit and feedback. One Cochrane Review found that audit and feedback was associated with a mean 4.3% improvement in health professionals' compliance with guidelines (Ivers 2012). The effect is small overall, but it appeared to be greater when baseline performance was low, when feedback came from a supervisor or colleague and was provided more than once, and when it included both explicit targets and an action plan. These circumstances were all present in the QUARITE trial, which showed a similar level of improvement in the quality of care measure (5.2%). In the OPERA trial, baseline performance was already good so there was probably little room for improvement. Interventions specifically tailored to overcome identified barriers to change led on average to an absolute 9.5% improvement (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.27 to 1.82) in desired professional practice (Baker 2010). Death review should also incorporate a discussion of barriers to change, which is taken into consideration when making and implementing recommendations. One frequent recommendation is training of health professionals, and both studies in our review included an element of training on guidelines and best practice. Another Cochrane Review has shown that in‐service training can improve performance of appropriate neonatal resuscitation, although impact on mortality was inconclusive (Opiyo 2015). Pattinson 2005 specifically aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of critical incident audit and feedback on maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity, but found no trials meeting the inclusion criteria – this concurs with our search which only found two studies, both published after the last update for this review. The same author led a non‐Cochrane review of perinatal mortality audits in low‐ and middle‐income countries, which found that there was a mean reduction in perinatal mortality of 30% (95% CI 21% to 38%), but this is based on uncontrolled before‐and‐after studies which did not meet the inclusion criteria for this review (Pattinson 2009).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Maternal, perinatal and child mortality are a priority globally, especially in low‐income countries, where much progress is needed to reach the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 (UN 2017). This review provides evidence that a complex intervention including maternal death audit and review, as well as development of local leadership and training, led to a 35% reduction in inpatient maternal mortality in district hospitals of low‐income countries, and probably slightly improved quality of care. There is also some evidence to support a complex intervention including perinatal death audit and review as well as training: the only cluster‐randomised trial was conducted in a high‐income country where mortality was already very low, but it still showed that the intervention probably improved quality of care, as measured by perinatal morbidity related to suboptimal care. However, there is currently no high‐quality evidence on the effects of paediatric death audit and review as neither of the included studies investigated this. Neither did we find any high‐quality evidence on the impact of community‐based death reviews, or any evaluation of cost‐effectiveness. Although other reviews have shown the general impacts of interventions such as audit and feedback and educational meetings (Ivers 2012; Forsetlund 2009), implementation of paediatric death audit and review and community‐based death reviews should probably be done in the context of rigorous evaluation to allow evidence on their impacts to be collected.