Key Points

Translational regulation can be global or mRNA specific, and most examples of translational regulation that have been described so far affect the rate-limiting initiation step.

Global control of translation is frequently exerted by regulating the phosphorylation or availability of initiation factors. Two of the most well-known examples are the regulation of eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF)4E availability by 4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs), and the modulation of the levels of active ternary complex by eIF2α phosphorylation.

mRNA-specific translational control is driven by RNA sequences and/or structures that are commonly located in the untranslated regions of the transcript. These features are usually recognized by regulatory proteins or micro RNAs (miRNAs).

Quasi-circularization of mRNAs can be mediated by the cap structure and the poly(A) tail via the eIF4E–eIF4G–polyA-binding-protein (PABP) interaction. Such interactions between the 5′ and the 3′ ends of mRNAs could provide a spatial framework for the action of regulatory factors that bind to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR). However, other forms of 5′–3′-end interactions are likely to occur as well.

Many regulatory proteins target the stable association of the small ribosomal subunit with the mRNA. These factors function by steric hindrance (for example, iron-regulatory protein; IRP), by interfering with the eIF4F complex (for example, Maskin, Bicoid, Cup) or by as-yet-unknown, distinct mechanisms to control translation initiation (sex-lethal; SXL).

Other regulatory molecules modulate the joining of the large ribosomal subunit (hnRNP K and E1) or, potentially, post-initiation translation steps (miRNAs).

General translation factors can regulate the expression of specific mRNAs. An illustrative example is the stimulation of translation of the mRNA that encodes the GCN4 transcriptional activator by eIF2α phosphorylation.

Abstract

Translational control is widely used to regulate gene expression. This mode of regulation is especially relevant in situations where transcription is silent or when local control over protein accumulation is required. Although many examples of translational regulation have been described, only a few are beginning to be mechanistically understood. Instead of providing a comprehensive account of the examples that are known at present, we discuss instructive cases that serve as paradigms for different modes of translational control.

Main

Translation of mRNA into protein represents the final step in the gene-expression pathway, which mediates the formation of the proteome from genomic information. The regulation of translation is a mechanism that is used to modulate gene expression in a wide range of biological situations. From early embryonic development to cell differentiation and metabolism, translation is used to fine-tune protein levels in both time and space1,2. However, although many examples have been described, much remains to be learned about the molecular mechanisms of translational control. Two general modes of control can be envisaged — global control, in which the translation of most mRNAs in the cell is regulated; and mRNA-specific control, whereby the translation of a defined group of mRNAs is modulated without affecting general protein biosynthesis or the translational status of the cellular transcriptome as a whole. Global regulation mainly occurs by the modification of translation-initiation factors, whereas mRNA-specific regulation is driven by regulatory protein complexes that recognize particular elements that are usually present in the 5′ and/or 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of the target mRNA. Recently, it has been found that mRNA translation can also be regulated by small MICRO RNAS (miRNAs) that hybridize to mRNA sequences that are frequently located in the 3′ UTR.

A special, and extremely interesting, case of mRNA-specific regulation is the local regulation of translation that occurs in a polarized cell. The translation of specific mRNAs is restricted to defined locations, such as the anterior or posterior pole of an oocyte, or a specific neuronal synapse. The purpose of this regulation is to generate protein gradients that emanate from a particular position in the cell, or to restrict protein expression to a small, defined region — for example, to a synapse. Although such local translational control almost invariably involves regulatory complexes that associate with the target transcripts, it might also use local changes in the activity of general translation factors3.

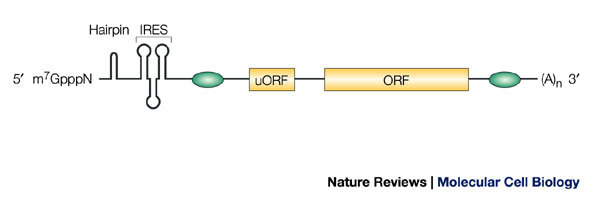

Structural features and regulatory sequences within the mRNA are responsible for its translational fate (Fig. 1). These include: the canonical end modifications of mRNA molecules — the CAP STRUCTURE and the POLY(A) TAIL — which are strong promoters of translation initiation; INTERNAL RIBOSOME-ENTRY SEQUENCES (IRESs), which mediate cap-independent translation initiation; UPSTREAM OPEN READING FRAMES (uORFs), which normally reduce translation from the main ORF; secondary or tertiary RNA structures, such as hairpins and PSEUDOKNOTS, which commonly block initiation, but can also be part of IRES elements and therefore promote cap-independent translation; and, specific binding sites for regulatory complexes, which are crucial determinants of mRNA translation. Although, in principle, regulation could activate or repress translation, most of the regulatory mechanisms that have been discovered so far are inhibitory, which implies that, unless a regulatory mechanism is imposed, the mRNAs are translationally active by default. However, this does not mean that all non-repressed mRNAs are actively engaged with ribosomes, because the activity of translation-initiation factors, particularly those that support the recruitment of ribosomal complexes that initiate translation, is frequently limiting. As a consequence, most mRNAs are distributed between an actively translated and a non-translated pool in the cytoplasm of cells, and changes in the activity of these limiting translation factors elicits changes in global protein synthesis.

Figure 1. Elements that influence translation of mRNA.

The m7GpppN cap structure at the 5′ end of the mRNA, and the poly(A) tail ((A)n in the figure) at the 3′ end, are canonical motifs that strongly promote translation initiation. Secondary structures, such as hairpins, block translation. Internal ribosome entry sequences (IRESs) mediate cap-independent translation. Upstream open reading frames (uORFs) normally function as negative regulators by reducing translation from the main ORF. Green ovals symbolize binding sites for proteins and/or RNA regulators, which usually inhibit, but occasionally promote, translation.

In this review we will discuss the detailed molecular mechanisms of translational regulation, by focusing on examples of both global and mRNA-specific translational control.

Translation initiation

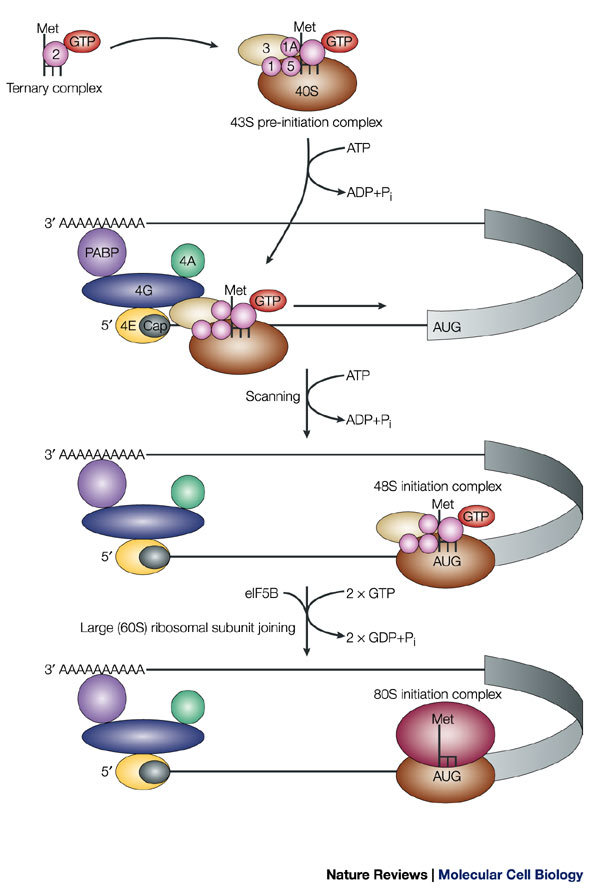

The translation process can be divided into three phases — initiation, elongation and termination. Whereas the elongation and termination phases are assisted by a limited set of dedicated factors, translation initiation in eukaryotes is a complex event that is assisted by more than 25 polypeptides4,5,6. Translation initiation involves the positioning of an elongation-competent 80S ribosome at the initiation codon (AUG). The small (40S) ribosomal subunit initially binds to the 5′ end of the mRNA and scans it in a 5′→3′ direction until the initiation codon is identified. The large (60S) ribosomal subunit then joins the 40S subunit at this position to form the catalytically competent 80S ribosome (Fig. 2). Here we provide a succinct overview of the process of translation initiation as far as it is directly relevant for the examples of translational regulation that are discussed below. For a more detailed description of the translation-initiation process, see Refs 4–6.

Figure 2. Cap-mediated translation initiation.

Only the translation-initiation factors that are discussed in the main text are depicted; others have been omitted for simplicity. Eukaryotic initiation factors (eIFs) are depicted as coloured, numbered shapes in the figure. For a complete account of translation-initiation factors, see Refs 4,6. The methionine-loaded initiator tRNA (L-shaped symbol) binds to GTP-coupled eIF2, to yield the ternary complex. This complex then binds to the small (40S) ribosomal subunit, eIF3 and other initiation factors to form the 43S pre-initiation complex. The pre-initiation complex recognizes the mRNA by the binding of eIF3 to the eIF4G subunit of the cap-binding complex. In addition to eIF4G, the cap-binding complex contains eIF4E, which directly binds to the cap, and eIF4A, an RNA helicase that unwinds secondary structure during the subsequent step of scanning. eIF4G also contacts the poly(A)-binding protein (PABP) and this interaction is thought to circularize the mRNA. The 43S pre-initiation complex scans the mRNA in a 5′→3′ direction until it identifies the initiator codon AUG. Scanning is assisted by the factors eIF1 and eIF1A. Stable binding of the 43S pre-initiation complex to the AUG codon yields the 48S initiation complex. Subsequent joining of the large (60S) ribosomal subunit results in the formation of the 80S initiation complex. Both AUG recognition and joining of the large ribosomal subunit trigger GTP hydrolysis on eIF2 and eIF5B, respectively. Subsequently, the 80S complex is competent to catalyze the formation of the first peptide bond. Pi, inorganic phosphate.

The small ribosomal subunit, together with other factors, forms a 43S pre-initiation complex that binds to the mRNA. This 43S assembly contains the EUKARYOTIC INITIATION FACTORS (eIFs) 3, 1, 1A and 5, and a ternary complex, which comprises the methionine-loaded initiator tRNA that will recognize the AUG codon during initiation and eIF2 that is coupled to GTP (Fig. 2). At least in mammals, binding of the 43S pre-initiation complex to the mRNA is thought to involve bridging interactions between eIF3 and the eIF4F protein complex, which associates with the 5′ cap structure of the mRNA7. The eIF4F complex contains several proteins, which include: eIF4E, which physically binds to the m7GpppN cap structure; eIF4A, a DEAD-BOX RNA HELICASE that is believed to unwind secondary structures in the 5′ UTR so that the 43S complex can bind and scan the mRNA; and eIF4G, which functions as a SCAFFOLD PROTEIN by interacting with eIF4E, eIF4A and eIF3 (Fig. 2). In yeast, the interaction between eIF4G and eIF3 has not been detected, and it is thought that recruitment of the 43S pre-initiation complex to the mRNA is assisted by other interactions, such as those between eIF4G and eIF5 (Ref. 8). eIF4G also interacts with the poly(A)-binding protein (PABP), and the simultaneous interaction of eIF4E and PABP with eIF4G is believed to circularize the mRNA, which brings the 3′ UTR in close proximity to the 5′ end of the mRNA9. This provides (at least conceptually) a spatial framework in which the 3′-UTR-binding factors can regulate translation initiation. In fact, most known regulatory sequences are found within the 3′ UTR, even though translation begins at the 5′ end of the mRNA, which highlights the functional connection between the mRNA ends during translation.

Several studies imply that the 43S pre-initiation complex scans along the 5′ UTR until it reaches and identifies the initiation codon10. However, as direct physical evidence for scanning intermediates remains to be found, scanning is probably a rapid process that involves unstable intermediates. Translation initiation requires energy in the form of ATP. It is unknown whether this energy is used to unwind secondary structures in the 5′ UTR to allow binding of the 43S complex, and/or to directly promote movement of the 43S complex. However, scanning of unstructured leaders can occur in the absence of ATP in vitro, which indicates that the movement of a 43S complex along the mRNA might not require energy unless the ribosome encounters a stable structure in the mRNA11. eIF1 and eIF1A contribute to the processivity of scanning11,12. Although it is unclear at present whether the 43S complex remains physically associated with the cap structure during scanning, the eIF4F complex has been shown to support scanning11. Binding of the 43S complex to the initiator codon AUG results in the formation of a stable complex, which is referred to as the 48S initiation complex. Selection of the correct initiation codon critically depends on eIF1 (Refs 11,12). There is also an alternative mode of translation initiation that is independent of the cap structure and is mediated by IRESs, which are RNA structures that help to recruit ribosomal complexes to internal sites of the 5′ UTR, sometimes directly at, or near, the initiation codon5 (Fig. 1).

The 43S complex recognizes the initiation codon through the formation of base pairs between the initiator tRNA and the start codon. Subsequently, eIF2-bound GTP undergoes hydrolysis that is catalyzed by eIF5 — a reaction that is necessary, but not sufficient, for the 60S ribosomal subunit to join the initiation complex. This is thought to release most of the initiation factors including eIF2-GDP from the small ribosomal subunit, leaving the initiator tRNA base-paired with AUG in the ribosomal P-site. A second step of GTP hydrolysis on eIF5B is then stimulated by the ribosome, and is required to release eIF5B to render it competent for polypeptide synthesis13,14 (Fig. 2).

Global control: eIF4E–4E-BPs and eIF2α kinases

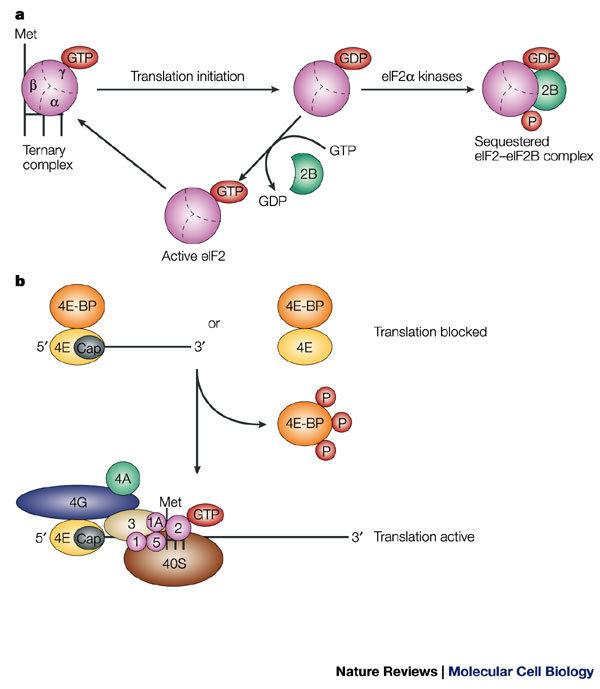

Global control of protein synthesis is generally achieved by changes in the phosphorylation state of initiation factors or the regulators that interact with them. Two well-characterized examples are discussed here.

As mentioned above, eIF2 is part of the ternary complex and associates with the small ribosomal subunit in its GTP-bound form. This GTP is hydrolyzed when the initiator AUG is recognized during translation initiation, producing eIF2 in the GDP-bound state. Exchange of GDP for GTP on eIF2 is catalyzed by eIF2B and is required to reconstitute a functional ternary complex for a new round of translation initiation15 (Fig. 3a). eIF2 consists of three subunits — α, β and γ — and phosphorylation of the α subunit at residue Ser51 blocks the GTP-exchange reaction by reducing the dissociation rate of eIF2 from eIF2B. In effect, this sequesters eIF2B16 and, as a consequence, GDP–GTP exchange no longer occurs and global mRNA translation is inhibited.

Figure 3. Global control of protein synthesis.

a | GTP hydrolysis and eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF)2 recycling in translation initiation, and the effect of phosphorylation of eIF2α on eIF2 activity. eIF2 consists of three subunits — α, β and γ — and is a component of the ternary complex, which also contains the methionine-loaded initiator tRNA (L-shaped symbol). In an active ternary complex, the eIF2-γ subunit is bound to GTP, and during translation initiation, this GTP molecule is hydrolyzed. GDP–GTP exchange on eIF2 is necessary to re-generate active eIF2 and is catalyzed by eIF2B. Phosphorylation of eIF2 on the α subunit reduces the dissociation rate of eIF2B, thereby sequestering the cellular complement of eIF2B and blocking the GDP–GTP exchange reaction. b | Function of eIF4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs). 4E-BPs bind to eIF4E, thereby preventing its interaction with eIF4G and so inhibiting translation. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP molecules releases the 4E-BPs from eIF4E, which allows their interaction with eIF4G, and thereby allows translation to proceed.

A number of kinases that are activated under different conditions can phosphorylate eIF2α at Ser51 (Refs 17,18). These include: the haem-regulated inhibitor (HRI), which is stimulated by haem depletion; GCN2 (general control non-derepressible-2), which is activated by amino-acid starvation; PKR (protein kinase activated by double-stranded RNA), which is stimulated by viral infection; and PERK, which is activated under circumstances of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Although phosphorylation of eIF2α by these kinases decreases global translation, this modification can also result in the translational activation of specific mRNAs (see below).

The availability of the cap-binding protein eIF4E is also used to regulate general translation rates. eIF4E interacts with the scaffold protein eIF4G and is required for cap-mediated recruitment of the 43S ribosomal complex to the mRNA during translation initiation (Fig. 2). Association between eIF4E and eIF4G requires a small domain in eIF4G that is shared by a family of proteins that are known as the 4E-BINDING PROTEINS (4E-BPs). Hypophosphorylated 4E-BPs bind to eIF4E and competitively displace eIF4G, which results in the inhibition of the association of the 43S complex with the mRNA and, consequently, in translational repression (Fig. 3b). Extracellular cues, such as insulin, activate a signalling cascade that triggers 4E-BP hyperphosphorylation and release from eIF4E19,20. As a result, eIF4E is free to bind to eIF4G and promote translation initiation.

In addition to the phosphorylation-mediated changes that regulate global translation, proteolytic cleavage of translation factors can inhibit cellular protein synthesis. For example, the apoptotic protein caspase-3 cleaves eIF4G and PABP21,22, and cleavage of these factors by viral proteases serves as a common and successful mechanism to interfere with the translation of cellular mRNAs23. As a consequence, some viral RNAs that do not require intact eIF4G and PABP are preferentially translated, as well as some cellular mRNAs that share such independence from intact eIF4G and PABP (C. Thoma and colleagues, unpublished results).

mRNA-specific regulation of 43S recruitment

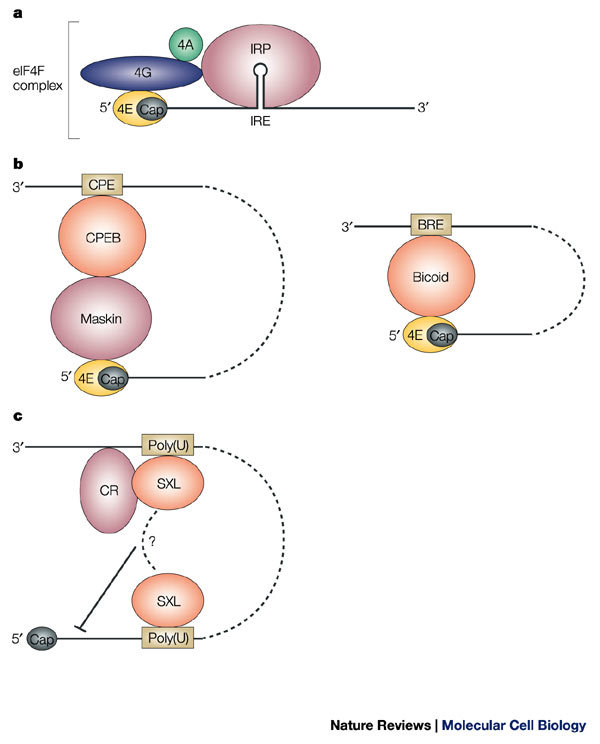

The association of the 43S ribosomal complex with an mRNA is targeted not only by regulators of global translation, but also by RNA-binding proteins that modulate the translation of specific mRNAs. Here we discuss three different mechanisms by which RNA-binding proteins achieve this goal.

Steric blockage. The iron regulatory proteins (IRP)1 and 2 control iron homeostasis, in part, by regulating the translation of the ferritin heavy- and light-chain mRNAs, which encode the two subunits of this iron storage protein. In iron-deficient cells, IRP1 and IRP2 bind to an iron-responsive element (IRE), which is a stem–loop motif in the 5′ UTR of the ferritin mRNAs. The IRE is located within 40 nucleotides of the cap structure, and IRP binding blocks the recruitment of the 43S complex to ferritin mRNA that is engaged with the eIF4F complex24,25 (Fig. 4a). Translational repression is ineffective when the IRE is moved to a more distal position from the cap, presumably because this manipulation provides sufficient space in the cap-proximal region for binding of the 43S complex26,27. This mechanism seems to operate by steric hindrance, because replacing the IRE–IRP interaction by an RNA-binding interaction that involves other proteins with no physiological function in eukaryotic translation — such as the spliceosomal protein U1A with its corresponding RNA-binding sequence — can fully recapitulate translational repression28.

Figure 4. Mechanisms of mRNA-specific regulation of 40S ribosomal subunit association.

a | Steric blockage. The iron regulatory proteins (IRPs) 1 or 2 bind to the iron-responsive element (IRE) and prevent the recruitment of the 43S pre-initiation complex to the mRNA-bound eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF)4F complex by steric hindrance. b | Interference with the eIF4F complex. The mRNA-specific eIF4E-binding proteins Maskin and Bicoid interact with eIF4E, thereby preventing its interaction with eIF4G. Maskin is targeted to the mRNA through the cytoplasmic-polyadenylation-element-binding protein (CPEB) that recognizes the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE) that is located at the 3′ untranslated region (UTR), whereas Bicoid directly binds to the mRNA at the Bicoid response element (BRE). c | Cap-independent inhibition. Binding of Sex-lethal (SXL) to uridine-rich sequences (Poly(U) in the figure) at both the 5′ and 3′ UTRs assists the recruitment of a co-repressor complex (CR) to inhibit translation, possibly by interference with ribosome scanning from the cap structure.

Interfering with the eIF4F complex. Whereas IRPs allow the cap-binding complex eIF4F to bind the mRNA25, some translational regulators that function during embryonic development target the formation of the eIF4F complex. The cytoplasmic-polyadenylation-element-binding protein (CPEB) regulates the translation of maternal mRNA during vertebrate oocyte maturation and early development. This protein binds to a uridine-rich sequence — the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE) — that is located in the 3′ UTR of target mRNAs and promotes both silencing of the mRNA before oocyte maturation as well as subsequent cytoplasmic polyadenylation and translational activation29. To repress translation, CPEB binds a protein known as Maskin that contains an eIF4E-binding domain, which resembles the one in eIF4G30. As such, the CPEB–Maskin complex can be considered to be an 'mRNA-specific 4E-BP' (Fig. 4b). The affinity of isolated Maskin for eIF4E is apparently lower than that of eIF4G, but a Maskin peptide that includes the eIF4E-binding domain can inhibit translation in vivo, which suggests that Maskin indeed competes with eIF4G for binding to eIF4E30.

Other regulators have also been found to function as message-specific 4E-BPs. During anteroposterior axis formation in the early Drosophila melanogaster embryo, the mRNA that encodes the posterior determinant Nanos becomes concentrated — and is specifically translated — at the posterior pole of the D. melanogaster oocyte. The protein Smaug binds to the 3′ UTR of unlocalized nanos mRNA and represses its translation by recruiting the eIF4E-binding, repressor protein Cup31. Cup is also recruited to the mRNA that encodes the posterior determinant Oskar by the RNA-binding protein Bruno, thereby preventing Oskar synthesis during the transit of oskar mRNA from the anterior to the posterior pole of the D. melanogaster oocyte32,33. So, Maskin and Cup represent regulatory proteins that associate indirectly with specific mRNAs by interacting with specific RNA-binding proteins, and seem to block eIF4E recognition by eIF4G. It is noteworthy that neither Maskin nor Cup were shown to directly prevent the recruitment of the 43S pre-initiation complex. Indeed, in the case of Cup, conflicting evidence indicates that the repressed nanos mRNA is associated with POLYSOMES, a finding that is more consistent with translational inhibition that occurs at a post-initiation step34. A variation on the theme of mRNA-specific 4E-BPs is provided by the anterior determinant Bicoid, which inhibits the translation of caudal mRNA at the anterior pole, in this case by directly binding to eIF4E35 (Fig. 4b).

Cap-independent inhibition of early initiation steps. Translation inhibition by IRP and message-specific 4E-BPs target steps of the translation-initiation pathway that are mediated by the cap structure. A recent example describes a regulator that inhibits the stable association of the 43S ribosomal complex with mRNA in a cap-independent manner. Sex-lethal (Sxl) prevents X-CHROMOSOME DOSAGE COMPENSATION in D. melanogaster females by repressing the translation of msl-2 mRNA, which encodes a crucial component of the dosage-compensation complex. To carry out this function, Sxl binds to specific sites in both the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of msl-2 mRNA and recruits co-repressors to the 3′ UTR36,37 (Fig. 4c). Although both the cap structure and the poly(A) tail contribute to the translation of msl-2 mRNA, regulation occurs independently of either of these structures36,38. Translational repression by Sxl affects the stable association of the small ribosomal subunit with the mRNA, because the formation of 48S complexes is inhibited in the presence of Sxl. Taken together, these data indicate the interesting possibility that the repressor complex that is assembled around Sxl on msl-2 mRNA arrests the scanning 43S pre-initation complex.

Other mechanisms. An intriguing example of translational control that involves the LARGE RIBOSOMAL SUBUNIT PROTEIN L13A has been described recently. CERULOPLASMIN (CP) synthesis is inhibited 24 hours after treatment with interferon-γ by the action of a cellular factor that binds to a stem–loop structure in the 3′ UTR of Cp mRNA39,40. This factor has been identified as the ribosomal protein L13a41. Phosphorylation of L13a after interferon-γ treatment causes its release from the 60S ribosomal subunit and promotes binding to the 3′ UTR of Cp mRNA. Curiously, dissociation of L13a from ribosomes after phosphorylation does not seem to affect global ribosome function41. Although the precise translational step that is affected by phosphorylated L13a has not been determined, repressed Cp mRNA is not found in association with polysomes, and translation inhibition requires the poly(A) tail as well as eIF4G and PABP39,42. These results implicate L13a in the regulation of translation initiation. The authors propose that circularization of the mRNA by the eIF4G–PABP interaction is necessary to bring L13a into close proximity with the 5′ UTR and thereby repress translation42.

Regulation at post-recruitment steps

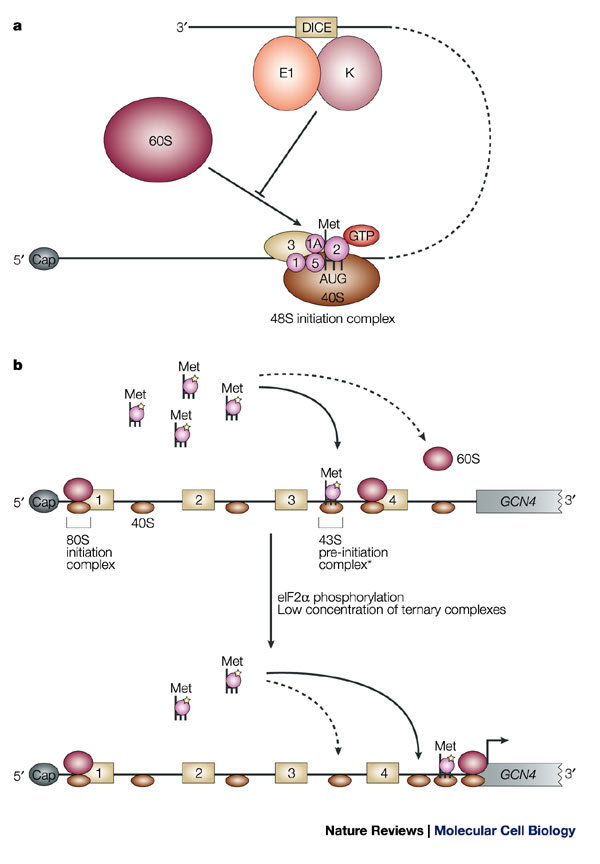

Translation can also be controlled at late-initiation and post-initiation steps. The RNA-binding proteins hnRNP K (heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K) and hnRNP E1 inhibit the translation of 15-lipoxygenase (LOX) mRNA during early erythroid differentiation. They bind to a repeated CU-rich element, which is known as the differentiation-control element (DICE) that is located in the LOX 3′ UTR. Translational repression of LOX is independent of the poly(A) tail and also occurs when translation is driven in a cap-independent manner by the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) or the classical swine fever virus (CSVF) IRESs, which indicates that this type of regulation targets a late step in initiation43,44. Sucrose-gradient analysis showed that 48S-complex formation occurred, but formation of the 80S ribosome was inhibited by the hnRNP-K–hnRNP-E1 complex. Furthermore, toe-printing analysis revealed that the 43S complex was placed at the initiator AUG codon on the silenced mRNA. So, these regulators seem to prevent the binding of the 60S ribosomal subunit to the 40S subunit at the initiation codon44 (Fig. 5a). In principle, hnRNP-K–hnRNP-E1 could achieve this either by interfering with a translation-initiation factor that is involved in this step, or by directly inhibiting the interaction between the two ribosomal subunits. However, hnRNP-K–hnRNP-E1 regulation is bypassed when the translation of a DICE-containing RNA is driven by the cricket paralysis virus (CrPV) IRES. As this IRES does not require any of the known translation-initiation factors, this finding suggests that hnRNP-K–hnRNP-E1 targets the initiation factors rather than the ribosomal subunits themselves44. However, it is not clear at present which initiation factor (or factors) represents the primary target of regulation.

Figure 5. Mechanisms of regulation at post-recruitment steps.

a | Regulation of the association of the 60S ribosomal subunit. Binding of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (hnRNP K) and hnRNP E1 to the differentiation-control element (DICE) in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of LOX mRNA prevents the 60S subunit from joining the 48S initiation complex at the initiator AUG codon. b | Mechanism of regulation of GCN4 mRNA translation. GCN4 mRNA contains four upstream open reading frames (uORF1–4). Under conditions of amino-acid sufficiency (upper panel), reinitiation occurs more frequently after each uORF (continuous arrow), because of an increased probability of recharging the scanning 40S subunits that traverse the regions between the uORFs with active ternary complexes. As a result, reinitiation at the GCN4 ORF becomes infrequent (dashed arrow). Under conditions of amino-acid scarcity, which induces eIF2α phosphorylation, and low levels of ternary complex (lower panel), reinitiation is unlikely to occur at the uORFs. This increases the probability of scanning 40S subunits reaching the region downstream of uORF4 and, subsequently, the GCN4 AUG initiation codon. The asterisk indicates that the exact composition of the 43S pre-initiation complex, in the context of reinitiation, is not known.

Amino-acid deprivation reduces global protein synthesis by phosphorylation of eIF2α by the kinase GCN2. Paradoxically, this same modification increases the translation of yeast GCN4 mRNA, thereby providing an example of how general translation factors can regulate the expression of specific mRNAs18. GCN4 mRNA encodes a protein that functions as a transcriptional activator of genes that regulate amino-acid biosynthesis, and contains four short ORFs upstream of the GCN4 initiation codon (Fig. 5b). Translation of the first uORF promotes efficient translation of GCN4, which indicates that GCN4 translation occurs by 'reinitiation', which is a relatively rare event — at least in eukaryotes — whereby a ribosome that has already translated an ORF resumes translation of a downstream ORF within the same mRNA molecule.

It is assumed that during translation termination the 60S ribosomal subunit dissociates at the stop codon of the first uORF, whereas the 40S subunit remains associated with the mRNA and can resume scanning. The model predicts that the 40S subunit acquires a ternary complex, and probably other initiation factors, during scanning, so that it can initiate translation at the downstream GCN4 ORF. The probability with which the 40S subunit acquires a ternary complex increases as it moves further away from the uORF. So, the longer it takes to scan the 5′ UTR, the more likely translation of GCN4 is to occur.

Regulation of GCN4 translation results from an interplay between the availability of active ternary complexes, the presence of the inhibitory uORF4 and the distance between uORF1 and both uORF4 and the GCN4 ORF. These elements and their relative position to each other determine how often a 'recharged' small ribosomal subunit reaches the GCN4 AUG45. When sufficient amino acids are available, the small ribosomal subunit can be more readily recharged with an active ternary complex after translation of uORF1 as it scans the segment between uORF2 and uORF4. As a consequence, translation resumes with a higher frequency at uORF4. Translation of uORF4 strongly inhibits translation of the GCN4 ORF, because the GC-rich sequence that surrounds the uORF4 stop codon promotes ribosome dissociation and release. For this reason, few recharged 40S subunits reach the GCN4 initiation codon, and only basal levels of GCN4 are produced (Fig. 5b).

Under conditions of amino-acid deprivation, however, the kinase GCN2 phosphorylates eIF2α, which reduces the amount of active ternary complexes in the cell (Fig. 3a). As a consequence, recharging of small ribosomal subunits that scan the segment between uORF2 and uORF4 is inefficient, and translation of uORF4 is unlikely. This increases the number of small ribosomal subunits that continue to scan to the initiation codon of GCN4, and provides an opportunity to bind an active ternary complex on the way. Therefore, an increased number of recharged ribosomal subunits reaches the GCN4 initiation codon, which explains the paradoxical increase in GCN4 translation when eIF2α is phosphorylated (Fig. 5b). A related mechanism is used to upregulate ATF4 mRNA translation in mammals. ATF4 is a transcriptional activator the expression of which is induced by several stress signals, including amino-acid starvation. Phosphorylation of eIF2α induces the translation of ATF4 mRNA by a mechanism that depends on the uORFs that are contained within its 5′ UTR, which indicates that this mode of translational control is evolutionarily conserved46.

Translational control by miRNAs

Studies that were carried out more than a decade ago implicated small regulatory RNAs in the control of mRNA translation47,48. It is now becoming clear that this early work represents the tip of the iceberg of what is emerging as a new field in translational control: the regulation of translation not only by protein factors, but also by small RNA molecules of ∼22 nucleotides in length that are known as micro RNAs (miRNAs). The first miRNAs to be discovered were lin-4 and let-7, which are crucial for regulating the developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans49. So far, several hundred miRNAs have been described in plants and animals that regulate a broad spectrum of biological processes, which range from cell metabolism to cell differentiation, cell growth and apoptosis50,51,52.

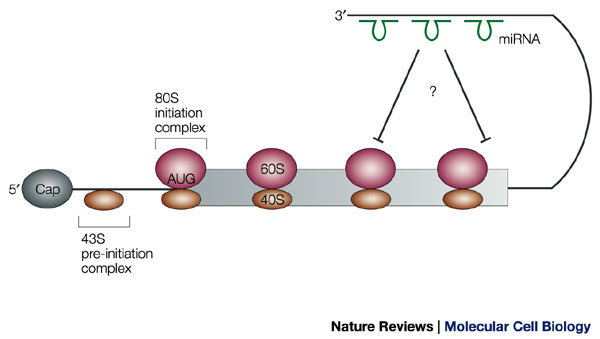

miRNAs hybridize by incomplete base-pairing, usually to several sites in the 3′ UTR of target mRNAs. Because the target mRNA remains intact after miRNA binding, the miRNAs are believed to repress translation, rather than prevent translation by degrading the mRNA. miRNA is biochemically indistinguishable from another small RNA species that is known as small interfering RNA (siRNA). siRNAs are double-stranded RNA molecules of 21–23 nucleotides in length, and they mediate the degradation of mRNAs that show perfect complementarity to either of the siRNA strands53. Indeed, the functional difference between miRNAs and siRNAs — translational repression versus mRNA degradation — is based on the degree of complementarity between the small mRNA molecule and the mRNA target, as target mRNA that was modified to base pair perfectly with an authentic miRNA was degraded54,55. Even though miRNAs and siRNAs arise from different precursors, they share common processing steps (Box 1). The miRNA-containing ribonucleoprotein (miRNP) particle contains proteins of the Argonaute family, which are also found in the siRNP56. However, it is unclear at present whether the molecular entities that catalyse mRNA degradation and translational repression are the same and, if not, to what extent they differ.

The mechanism of translational repression by miRNAs is largely unknown. Translational repression of lin-14 mRNA by lin-4 miRNA did not alter its association with polysomes, which indicates that lin-4 inhibits the elongation and/or termination of translation57 (Fig. 6). Furthermore, C. elegans ribosomes that are associated with a repressed lin-14 mRNA were able to continue translation when incubated in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate, which indicates that ribosomes are not permanently stalled on the repressed MESSENGER RIBONUCLEOPROTEIN (mRNP)58. More definitive mechanistic insights are likely to require the establishment of in vitro translation systems that completely recapitulate the translational block that is imposed by miRNAs. It also remains to be determined whether translational repression by miRNAs requires proteins that recognize the mRNA–miRNA hybrid.

Figure 6. Translational control by micro RNAs.

Micro RNAs (miRNAs; shown in green) engage in imperfect base-pairing interactions with the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) and cause translational arrest. At present, evidence indicates that this occurs in polysomal complexes after the initiation of polypeptide synthesis.

Conclusions and perspectives

Both the global control of protein synthesis and mRNA-specific translational regulation represent key mechanisms of gene modulation. Although the mechanisms of global control have been studied in considerable detail, the mechanisms of mRNA-specific translational regulation are being uncovered more gradually, and the diversity of mechanisms continues to increase. mRNA-specific regulation by single proteins (for example, IRP) might well be an exception, as most cases seem to involve multiprotein (and, perhaps, miRNA) regulatory assemblies. Although the steps at which these assemblies control translation initiation have now been identified for a few examples, understanding their interplay with the translation-initiation factors and ribosomal subunits represents one of the problems that remains to be solved. How regulators can interfere with translation elongation and/or termination also remains to be determined. Of special interest is the translational regulation by miRNAs. Understanding the role of partial complementarity between the miRNA and the target mRNA, the function of putative protein factors and the detailed modes of action of these regulators are among the challenges for the future.

Box 1 | Micro RNA and small-interfering RNA biosynthesis and function.

Micro RNAs (miRNAs) are transcribed as primary transcripts that are processed in the nucleus by Drosha, a member of the RNase III superfamily59, to yield precursors of ∼70 nucleotides (pre-miRNAs) that have the capacity to form stem–loop structures. The pre-miRNAs are further processed into mature miRNAs in the cytoplasm by another RNase-III-like enzyme that is known as Dicer60,61,62.

Dicer is also involved in the generation of small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) from precursors of long, double-stranded RNAs63. The mature siRNAs then form an RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) that mediates the degradation of mRNAs that have perfect complementarity to the siRNA64. Although the exact composition of RISC and the miRNA-containing ribonucleoprotein particles (miRNPs) is unknown, both contain proteins of the Argonaute family56,65. This observation, together with the fact that miRNAs can behave as siRNAs, has led some to speculate that RISC might direct both mRNA degradation and translational silencing54.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank J. Valcárcel and R. Cuesta for carefully reading this manuscript. F.G. is supported by grants from La Caixa Foundation and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology. M.W.H. gratefully acknowledges support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the European Union and the Human Frontiers in Science Program.

Glossary

- MICRO RNA

A non-coding RNA molecule of ∼21–23 nucleotides that inhibits mRNA expression.

- CAP STRUCTURE

A structure, which consists of m7GpppN (where m7G represents 7-methylguanylate, p represents a phosphate group and N represents any base), that is located at the 5′ end of eukaryotic mRNAs.

- POLY(A) TAIL

A homopolymeric stretch of usually 25–200 adenine nucleotides that is present at the 3′ end of most eukaryotic mRNAs.

- INTERNAL RIBOSOME–ENTRY SEQUENCE

(IRES). A structure that is located in the 5′ UTR or open reading frame of some mRNAs of cellular or viral origin. It mediates translation initiation independently of the cap structure by recruiting the ribosome directly to an internal position of the mRNA.

- UPSTREAM OPEN READING FRAME

(uORF). A small open reading frame that is located in the 5′ UTR of some mRNAs.

- PSEUDOKNOT

A RNA tertiary structure that is formed when the single-stranded loop in a hairpin structure base pairs with a complementary sequence outside of the hairpin.

- EUKARYOTIC INITIATION FACTOR

(eIF). A protein that mediates translation initiation on bulk mRNA.

- DEAD-BOX RNA HELICASE

An enzyme that unwinds RNA duplexes and contains the evolutionarily conserved motif DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) in the helicase core region.

- SCAFFOLD PROTEIN

A protein that serves as a platform for the assembly of other proteins.

- 4E-BINDING PROTEIN

(4E-BP). A protein that interacts with the cap-binding protein eIF4E and inhibits its association with eIF4G.

- POLYSOME

A string of multiple 80S ribosomes bound to an mRNA molecule.

- X-CHROMOSOME DOSAGE COMPENSATION

A process that balances the expression levels of X-linked genes in those organisms in which males and females contain a different number of X chromosomes.

- LARGE RIBOSOMAL SUBUNIT PROTEIN L13A

A structural protein that binds to the outer surface of the large (60S) ribosomal subunit.

- CERULOPLASMIN

A glycoprotein secreted by the liver that oxidizes Fe2+ to Fe3+.

- RNase III

A family of endoribonucleases that cleave double-stranded RNA and have an important role in the maturation of ribosomal RNA, among other processes.

- MESSENGER RIBONUCLEOPROTEIN

(mRNP). A messenger RNA that is associated with proteins and that often represents translationally inactive (non-polysomal) mRNA.

Biographies

Fátima Gebauer obtained her Ph.D. from the Autónoma University in Madrid, Spain, where she studied several aspects of coronavirus biology with Luis Enjuanes. She then moved to the Worcester Foundation, Massachussetts, USA, to work with Joel Richter on translational control by cytoplasmic polyadenylation during early vertebrate development. In 1996, she joined Matthias Hentze's group at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg, Germany, where she studied the translational regulation by RNA-binding proteins during Drosophila development. In 2000, she obtained a staff scientist position at EMBL and since 2002 she has been working as a group leader at the Center for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona, Spain.

Matthias W. Hentze obtained his M.D. from Münster University, Germany. His postdoctoral work at the National Institutes of Health, Betheda, USA, in Richard D. Klausner's group focused on the discovery and characterization of the iron-responsive element (IRE)/iron-regulatory protein (IRP) regulatory system. In 1989, he joined the EMBL in Heidelberg, where he now serves as a Programme Coordinator, Senior Scientist and Dean of Graduate Studies. His scientific interests include protein synthesis and its regulation, nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and its role in human disease, iron metabolism and associated diseases, as well as molecular medicine in general.

Related links

DATABASES

Entrez

Flybase

Swiss-Prot

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contributor Information

Fátima Gebauer, Email: fatima.gebauer@crg.es.

Matthias W. Hentze, Email: hentze@embl.de

References

- 1.Kuersten S, Goodwin EB. The power of the 3′ UTR: translational control and development. Nature Rev. Genet. 2003;4:626–637. doi: 10.1038/nrg1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wickens M, Goodwin E, Kimble. J, Strickland S, Hentze M. Translational control of gene expression. 2000. p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnstone O, Lasko P. Translational regulation and RNA localization in Drosophila oocytes and embryos. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2001;35:365–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hershey JWB, Merrick WC. Translational control of gene expression. 2000. p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pestova TV, et al. Molecular mechanisms of translation initiation in eukaryotes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:7029–7036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111145798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preiss T, Hentze MW. Starting the protein synthesis machine: eukaryotic translation initiation. Bioessays. 2003;25:1201–1211. doi: 10.1002/bies.10362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamphear BJ, Kirchweger R, Skern T, Rhoads RE. Mapping of functional domains in eukaryotic protein synthesis initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) with picornaviral proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:21975–21983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asano K, et al. Multiple roles for the C-terminal domain of eIF5 in translation initiation complex assembly and GTPase activation. EMBO J. 2001;20:2326–2337. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells SE, Hillner PE, Vale RD, Sachs AB. Circularisation of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:135–140. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozak M. Pushing the limits of the scanning mechanism for initiation of translation. Gene. 2002;299:1–34. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)01056-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pestova TV, Kolupaeva VG. The roles of individual eukaryotic translation initiation factors in ribosomal scanning and initiation codon selection. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2906–2922. doi: 10.1101/gad.1020902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pestova TV, Borukhov SI, Hellen CU. T. Eukaryotic ribosomes require initiation factors 1 and 1A to locate initiation codons. Nature. 1998;394:854–859. doi: 10.1038/29703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pestova TV, et al. The joining of ribosomal subunits in eukaryotes requires eIF5B. Nature. 2000;403:332–335. doi: 10.1038/35002118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin BS, et al. Uncoupling of initiation factor eIF5B/ IF2 GTPase and translational activities by mutations that lower ribosome affinity. Cell. 2002;111:1015–1025. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinnebusch AG. Translational control of gene expression. 2000. p. 185. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowlands AG, Panniers R, Henshaw EC. The catalytic mechanism of guanine nucleotide exchange factor action and competitive inhibition by phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:5526–5533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Haro C, Mendez R, Santoyo J. The eIF-2α kinases and the control of protein synthesis. FASEB J. 1996;10:1378–1387. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.12.8903508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dever TE. Gene-specific regulation by general translation factors. Cell. 2002;108:545–556. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N. eIF4 initiation factors: effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:913–963. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pause A, et al. Insulin-dependent stimulation of protein synthesis by phosphorylation of 5′ cap function. Nature. 1994;371:762–767. doi: 10.1038/371762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bushell M, et al. Cleavage of polypeptide chain initiation factor eIF4GI during apoptosis in lymphoma cells: characterisation of an internal fragment generated by caspase-3-mediated cleavage. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:628–636. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marissen WE, Triyoso D, Younan P, Lloyd RE. Degradation of poly(A)-binding protein in apoptotic cells and linkage to translation regulation. Apoptosis. 2004;9:67–75. doi: 10.1023/B:APPT.0000012123.62856.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider RJ, Mohr I. Translation initiation and viral tricks. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:130–136. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00029-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray NK, Hentze MW. Iron regulatory protein prevents binding of the 43S translation pre-initiation complex to ferritin and eALAS mRNAs. EMBO J. 1994;13:3882–3891. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muckenthaler M, Gray NK, Hentze MW. IRP-1 binding to ferritin mRNA prevents the recruitment of the small ribosomal subunit by the cap-binding complex eIF4F. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:383–388. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goossen B, Caughman SW, Harford JB, Klausner RD, Hentze MW. Translational repression by a complex between the iron-responsive element of ferritin mRNA and its specific cytoplasmic binding protein is position-dependent in vivo. EMBO J. 1990;9:4127–4133. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paraskeva E, Gray NK, Schlager B, Wehr K, Hentze MW. Ribosomal pausing and scanning arrest as mechanisms of translational regulation from cap-distal iron-responsive elements. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:807–816. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.1.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stripecke R, Oliveira CC, McCarthy JE, Hentze MW. Proteins binding to 5′ untranslated region sites: a general mechanism for translational regulation of mRNAs in human and yeast cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:5898–5909. doi: 10.1128/MCB.14.9.5898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendez R, Richter JD. Translational control by CPEB: a means to the end. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:521–529. doi: 10.1038/35080081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stebbins-Boaz B, Cao Q, de Moor CH, Mendez R, Richter JD. Maskin is a CPEB-associated factor that transiently interacts with elF-4E. Mol. Cell. 1999;4:1017–1027. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson MR, Leidal AM, Smibert CA. Drosophila Cup is an eIF4E binding protein that functions in Smaug-mediated translational repression. EMBO J. 2004;23:150–159. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilhelm JE, Hilton M, Amos Q, Henzel WJ. Cup is an eIF4E binding protein required for both the translational repression of oskar and the recruitment of Barentsz. J. Cell Biol. 2003;163:1197–1204. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakamura A, Sato K, Hanyu-Nakamura K. Drosophila Cup is an eIF4E binding protein that associates with Bruno and regulates oskar mRNA translation in oogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:69–78. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00400-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clark IE, Wyckoff D, Gavis ER. Synthesis of the posterior determinant Nanos is spatially restricted by a novel cotranslational regulatory mechanism. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:1311–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00754-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niessing D, Blanke S, Jackle H. Bicoid associates with the 5′-cap-bound complex of caudal mRNA and represses translation. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2576–2582. doi: 10.1101/gad.240002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gebauer F, Grskovic M, Hentze MW. Drosophila sex-lethal inhibits the stable association of the 40S ribosomal subunit with msl-2 mRNA. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1397–1404. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00176-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grskovic M, Hentze MW, Gebauer F. A co-repressor assembly nucleated by Sex-lethal in the 3′ UTR mediates translational control of Drosophila msl-2mRNA. EMBO J. 2003;22:5571–5581. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gebauer F, Corona DF, Preiss T, Becker PB, Hentze MW. Translational control of dosage compensation in Drosophila by Sex-lethal: cooperative silencing via the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of msl-2 mRNA is independent of the poly(A) tail. EMBO J. 1999;18:6146–6154. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazumder B, Fox PL. Delayed translational silencing of ceruloplasmin transcript in γ-interferon-activated U937 monocytic cells: role of the 3′ untranslated region. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:6898–6905. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.10.6898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sampath P, Mazumder B, Seshadri V, Fox PL. Transcript-selective translational silencing by γ-interferon is directed by a novel structural element in the ceruloplasmin mRNA 3′ untranslated region. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:1509–1519. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1509-1519.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazumder B, et al. Regulated release of L13a from the 60S ribosomal subunit as a mechanism of transcript-specific translational control. Cell. 2003;115:187–198. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mazumder B, Seshadri V, Imataka H, Sonenberg N, Fox PL. Translational silencing of ceruloplasmin requires the essential elements of mRNA circularization: poly(A) tail, poly(A)-binding protein, and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:6440–6449. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.19.6440-6449.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ostareck DH, et al. mRNA silencing in erythroid differentiation: hnRNP K and hnRNP E1 regulate 15-lipoxygenase translation from the 3′ end. Cell. 1997;89:597–606. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80241-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ostareck DH, Ostareck-Lederer A, Shatsky IN, Hentze MW. Lipoxygenase mRNA silencing in erythroid differentiation: the 3′ UTR regulatory complex controls 60S ribosomal subunit joining. Cell. 2001;104:281–290. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hinnebusch AG. Translational regulation of yeast GCN4. A window on factors that control initiator-tRNA binding to the ribosome. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:21661–21664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harding HP, et al. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros VThe. C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;75:855–862. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carrington JC, Ambros V. Role of microRNAs in plant and animal development. Science. 2003;301:336–338. doi: 10.1126/science.1085242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ambros V. MicroRNA pathways in flies and worms: growth, death, fat, stress, and timing. Cell. 2003;113:673–676. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00428-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stark A, Brennecke J, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Identification of Drosophila microRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:397–409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Enright AJ, et al. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2003;5:R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zamore PD. Ancient pathways programmed by small RNAs. Science. 2002;296:1265–1269. doi: 10.1126/science.1072457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hutvagner G, Zamore PD. A microRNA in a multiple-turnover RNAi enzyme complex. Science. 2002;297:2056–2060. doi: 10.1126/science.1073827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zeng Y, Yi R, Cullen BR. MicroRNAs and small interfering RNAs can inhibit mRNA expression by similar mechanisms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;19:9779–9784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1630797100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mourelatos Z, et al. miRNPs: a novel class of ribonucleoproteins containing numerous microRNAs. Genes Dev. 2002;16:720–728. doi: 10.1101/gad.974702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olsen PH, Ambros V. The lin-4 regulatory RNA controls developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans by blocking LIN-14 protein synthesis after the initiation of translation. Dev. Biol. 1999;216:671–680. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seggerson K, Tang L, Moss EG. Two genetic circuits repress the Caenorhabditis elegans heterochronic gene lin-28 after translation initiation. Dev. Biol. 2002;243:215–225. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee Y, et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hutvagner G, et al. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science. 2001;293:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1062961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ketting RF, et al. Dicer functions in RNA interference and in synthesis of small RNA involved in developmental timing in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2654–2659. doi: 10.1101/gad.927801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grishok A, et al. Genes and mechanisms related to RNA interference regulate expression of the small temporal RNAs that control C. elegans developmental timing. Cell. 2001;106:23–34. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00431-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363–366. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hammond SM, Bernstein E, Beach D, Hannon GJ. An RNA-directed nuclease mediates post-transcriptional gene silencing in Drosophila cells. Nature. 2000;404:293–296. doi: 10.1038/35005107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hammond SM, Boettcher S, Caudy AA, Kobayashi R, Hannon GJ. Argonaute2, a link between genetic and biochemical analyses of RNAi. Science. 2001;293:1146–1150. doi: 10.1126/science.1064023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]