Key Points

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved cellular process that is initiated by starvation and other developmental and environmental cues. The formation and maturation of autophagosomes involves the sequestration of cytoplasm within double-membrane-bound vesicles and leads to proteasome-independent degradation of the cytosolic contents.

Many genes that are required for autophagy have been identified, first in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and then in other organisms by homology.

Numerous microscopical, pharmacological and biochemical assays for autophagy have been developed. The identification of genes that are required for autophagy now allows genetic tests for the involvement of autophagy in a process of interest.

Several invasive bacterial species are vulnerable to destruction by autophagy. However, it has been argued that Legionella pneumophila and several other bacterial species can subvert autophagic components to enhance their growth.

One of the consequences of the activation of the antiviral protein PKR is an increase in cellular autophagy, which makes it likely that autophagy is a component of the cellular antiviral response. However, several positive-strand RNA viruses replicate their genomes on double-membrane-bound vesicles that are thought to be derived from autophagic structures.

As for other cellular defences against microorganisms, some bacteria and viruses seem to have evolved mechanisms to inhibit or subvert autophagy.

Abstract

Intracellular bacteria and viruses must survive the vigorous antimicrobial responses of their hosts to replicate successfully. The cellular process of autophagy — in which compartments bound by double membranes engulf portions of the cytosol and then mature to degrade their cytoplasmic contents — is likely to be one such host-cell response. Several lines of evidence show that both bacteria and viruses are vulnerable to autophagic destruction and that successful pathogens have evolved strategies to avoid autophagy, or to actively subvert its components, to promote their own replication. The molecular mechanisms of the avoidance and subversion of autophagy by microorganisms will be the subject of much future research, not only to study their roles in the replication of these microorganisms, but also because they will provide — as bacteria and viruses so often have — unique tools to study the cellular process itself.

Main

Cellular autophagy involves the sequestration of regions of the cytosol within double-membrane-bound compartments that then mature and degrade their cytoplasmic contents. It is a highly regulated process, the components of which have only recently been identified by extensive studies using yeast genetics. Owing to groundbreaking work in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a host of autophagy genes have now been described, the mechanisms of action of many of their products determined and their mammalian and other homologues identified1. In this review, we will use the notation ATG, the newly adopted nomenclature, for the genes that function in autophagy2. There is a substantial body of literature describing studies in which new genetic tools have been used to show that autophagy, its machinery or both are required for many aspects of cellular function and organismal development. For example, human beclin1, a homologue of yeast ATG6, has been shown to be a tumour-suppressor gene3. Starvation responses also require autophagy: DAUER formation in Caenorhabditis elegans requires functional beclin1 (Ref. 4) and the survival of Dictyostelium discoideum during nitrogen starvation requires functional homologues of yeast ATG5 and ATG7 (Ref. 5). Furthermore, in both Arabidopsis thaliana6,7 and C. elegans4, wild-type autophagy genes are required to prevent premature senescence.

One attractive hypothesis is that the degradation of cytosolic structures by autophagy might have a general role in 'clearing away' intracellular pathogens. Observations of intracellular viruses and bacteria within multivesicular bodies have often been reported from electron-microscopy (EM) studies8. In addition, an unexplained phenomenon known as hepatic 'purging' is seen in hepatitis-B-infected chimpanzees. As many as 75% of the hepatic cells in these infected animals were shown to contain viral proteins at 10 weeks post-infection, but proved to be virus-free, in the absence of extensive cell death, by 20 weeks9. There must, therefore, be extremely efficient antimicrobial mechanisms that do not involve apoptosis or the destruction of infected hepatic cells by the immune system. In this review, we will discuss the accumulated functional evidence that autophagy is a component of the innate immune response that has both antiviral and antibacterial functions. Although this review will focus on viruses and intracellular bacteria, several reports have also indicated interactions between eukaryotic parasites and components of the autophagic pathway10,11.

Autophagic structures

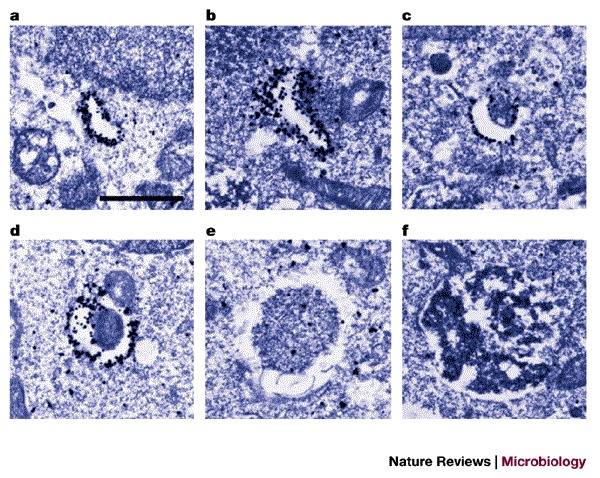

Studies of cells undergoing autophagy using EM show structures surrounded by two distinct lipid bilayers; these structures are known as autophagosomes (Fig. 1). The inner membranes of these structures surround material that has an electron density equivalent to that of the cytoplasm, whereas the lumenal area between the two delimiting membranes is electron-transparent. Autophagosomes are large — with diameters of 400–900 nm in yeast and 500–1,500 nm in mammalian cells12 — and contain cytoplasm and cytoplasmic organelles, such as fractured endoplasmic reticulum (ER), mitochondria and PEROXISOMES. Autophagosomes also contain a mixture of protein markers from the ER, endosomes and lysosomes, as well as bulk-cytosolic contents13,14,15. A list of the markers that are used to identify autophagosomes is provided in Table 1.

Figure 1. Immunoelectron microscopy of GFP–Atg5-expressing human cells undergoing autophagy.

Atg5−/− mouse embryonic stem cells were stably transfected with yeast Atg5 tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP–Atg5) and cultured in Hanks' solution for 2 h to induce autophagy. The localization of GFP–Atg5 was examined by silver-enhanced immuno-gold electron microscopy using an anti-GFP antibody. a–d | A series of images showing the presumed progression of membrane extension and cytosolic sequestration during autophagosome formation. e | An example of an autophagosome. f | An example of an autolysosome. Scale bar, 1 μm. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 17 © (2001) Rockerfeller University Press.

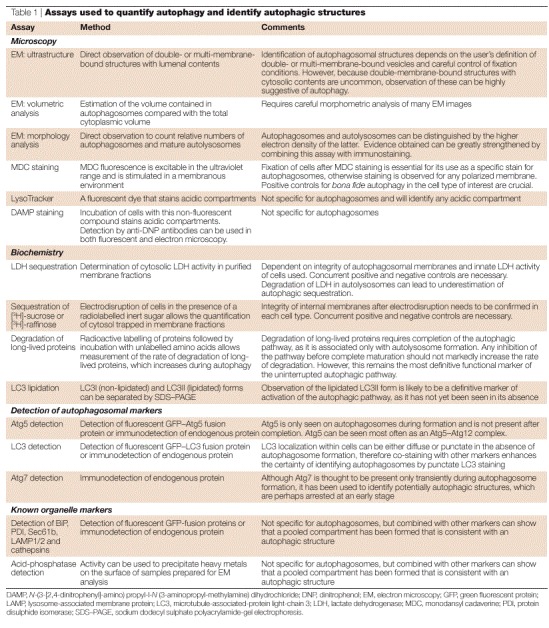

Table 1.

Assays used to quantify autophagy and identify autophagic structures

The presence of markers from a variety of cellular sources makes it difficult to determine the origins of autophagosomal membranes. On the basis of ultrastructural observations and the recognition of autophagosomes by antiserum against proteins of the rough ER, the ER has been suggested as the source of these membranes16. An alternative hypothesis is that the fusion of small, lipid-containing vesicles forms a unique C-shaped structure, which is known as the 'sequestration crescent'. This is supported by the observation of small, membranous structures that are labelled by the Atg5 protein, which could be structural precursors of the mature autophagosome17. The presumed progression of this structure from initiation to the closure of the sequestering membranes into an autophagosome is shown in Fig. 1. The final resolution of these hypotheses might have to await the development of cell-free systems to study autophagosome formation. Although autophagy takes its name from the destruction of cellular constituents, it is clear that several processes constitute the autophagic pathway, including cell signalling, membrane rearrangements and compartmental mixing, in addition to the ultimate degradation of sequestered cytosol.

The autophagic pathway and its mechanisms

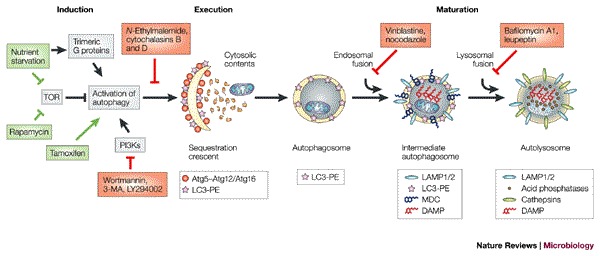

Autophagy can be divided into three stages: initiation, execution and maturation (Fig. 2). The initiation of autophagy can be triggered by a variety of extracellular signals, including nutrient starvation and treatment with hormones. One target of these signals is TOR (target of RAPAMYCIN), a kinase that inhibits the autophagic pathway until this protein is inactivated by dephosphorylation. TOR is a global cell regulator that also controls protein translation and amino-acid synthesis18. Rapamycin and nutrient starvation cause the dephosphorylation of TOR, which, in turn, activates the autophagic pathway. A third compound, TAMOXIFEN, is known to induce autophagy, but it is not known whether this is mediated through TOR or a different pathway19.

Figure 2. The autophagic pathway.

The known steps of induction, execution and maturation of autophagosomes and autolysosomes. Green lines and arrows indicate activation or inhibition events, respectively, that induce autophagy; red lines indicate events that inhibit autophagy. The markers that are present at each morphological step are indicated in the key, as are several known inhibitors and the steps at which they are thought to act (red boxes). Caution must be used in interpreting the results obtained using all of these inhibitors, due to their pleiotropic effects. 3-MA, 3-methyladenine; DAMP, N-(3-[2,4-dinitrophenyl]-amino) propyl-l-N-(3-aminopropyl-methylamine) dihydrochloride); LAMP, lysosome-associated membrane protein; LC3, microtubule-associated-protein light-chain 3; MDC, monodansylcadaverine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; TOR, target of rapamycin.

Studies in cancer cell lines have shown that trimeric Gi3 proteins and class I and II phosphatidylinositol-3-kinases (PI3Ks) function in a step that takes place before autophagic sequestration20,21. In fact, high concentrations of amino acids have recently been shown to result in the inactivation of trimeric G proteins, indicating the existence of another mechanism, in addition to the inhibition of the TOR pathway, by which amino-acid depletion might activate autophagy22. Many commonly used inhibitors of autophagy, including 3-methyladenine (3-MA), wortmannin and LY294002, target all cellular PI3Ks. However, it has been shown that it is the class III PI3Ks — and the phosphotidylinositol-3-phosphate that they produce — that are essential for starvation-induced autophagic signalling and autophagosome formation21. The autophagic sequestration of cytosol was also shown to be inhibited by OKADAIC ACID, indicating a role for protein phosphatase 2A in starvation-induced autophagosome formation23. In summary, the signals that induce autophagy are mediated by TOR, PI3Ks, protein phosphatases and trimeric G proteins through pathways that are, so far, incompletely understood.

The key stages of autophagosomal execution are mediated by two very interesting covalent-conjugation pathways: the covalent linkage of Atg5 and Atg12, and the covalent lipidation of Atg8 by phosphatidylethanolamine. The enzymes that mediate these conjugations — Atg3, Atg7 and Atg10 — are homologues of enzymes that are involved in protein UBIQUITYLATION24,25. Unlike ubiquitylation, however, protein conjugation in autophagy is used to modify pathway components and not to label substrates for degradation.

The covalent linkage of Atg5 and Atg12 is accomplished in several steps: the carboxy-terminal glycine of the 187-amino-acid Atg12 protein is activated by transient covalent linkage first to Atg7 and then to Atg10, before becoming covalently attached to Lys130 of Atg5 (Refs 26–28). Mutant forms of the Atg5 protein that lack the lysine residue that is necessary for conjugation do not form Atg5–Atg12–Atg16 complexes or autophagosomes, but still associate with membranes. This indicates that Atg5 itself contains a membrane-targeting domain, and is perhaps responsible for the targeting of the entire complex17. As shown in Figs 1 and 2, the Atg5–Atg12–Atg16 complex is present only on the sequestration crescent, a double-membrane-bound structure that engulfs cytosolic constituents to become the apparently closed, double-membrane-bound autophagosome.

The second conjugation pathway results in the covalent addition of the lipid phosphatidylethanolamine to the newly generated carboxyl terminus of microtubule-associated-protein light-chain 3 (LC3), the human homologue of S. cerevisiae Atg8. The carboxy-terminal amino acids of LC3 are cleaved by the cysteine protease Atg4 to leave a conserved glycine residue. Cleaved LC3 is then transiently linked to the Atg7 protein, then to Atg3, and finally to phosphatidylethanolamine29. Lipidation of LC3 is necessary and sufficient for membrane association and, as shown in Fig. 2, modified LC3 remains associated with autophagosomes until destruction at the autolysosomal stage.

After formation, autophagosomes fuse with endosomal vesicles and acquire lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) and LAMP2, and gain the ability to accumulate DAMP (N-(3-[2,4-dinitrophenyl]-amino) propyl-l-N (3-aminopropyl-methylamine) dihydrochloride), thus becoming intermediate autophagosomes30 (Fig. 2). These structures fuse with lysosomes and acquire CATHEPSINS and acid phosphatases to become mature autolysosomes (Fig. 2). Vesicle fusion is often mediated by small GTPases, such as the RAB proteins31. Recently, Rab24, an orphan small GTPase, was shown to associate specifically with autophagosomes and, although its roles in autophagosome trafficking, fusion and maturation are not yet known, this might provide an important clue to the late events of autophagosome formation, as well as providing an additional marker for autophagic structures32.

Assays for the autophagic pathway

There are many methods for identifying and quantifying autophagosome formation and function (Table 1). The analysis of cells by EM as they undergo autophagy is a classic and important method. Autophagy can be quantified from electron micrographs, and this often involves estimating the volume that is contained within the autophagosomal structures compared with that in the remainder of the cytoplasm. Furthermore, autophagosomes can be divided into two classes on the basis of their morphology, as shown by EM: immature (or early) autophagosomes (Fig. 1d,e) contain two or more bilayers surrounding cytoplasmic material, whereas mature autolysosomes (Fig. 1f) have a more homogeneous density and lose the distinctive inner membrane of early autophagosomes.

Unfortunately, very few proteins are specifically retained in autophagosomes. Whereas Atg5 only labels the earlier autophagosomal structures (Fig. 1), both S. cerevisiae Atg8 and its human homologue LC3 are retained in autophagosomal membranes until maturation is complete29. The use of these markers in immunoelectron and fluorescence microscopy greatly facilitates the identification of autophagosomal structures33.

Some methods of autophagosome identification use compounds that accumulate in and label the various cellular compartments and organelles that participate in autophagosome formation. One such compound is LysoTracker (Molecular Probes, USA), which normally stains lysosomes34. DAMP is a non-fluorescent molecule that, similarly to LysoTracker, accumulates in acidic compartments30. Individually, these compounds do not uniquely stain autophagosomes; however, when used in conjunction with the detection of proteins in the autophagic pathway, they can help researchers to distinguish autophagosomes from other structures in the cell.

Monodansylcadaverine (MDC), a fluorescent compound, has also been shown to stain autophagosomes35. MDC can be incorporated into living cells, where it stains polarized membranes and becomes fluorescent on excitation with ultraviolet light. Specificity for autophagosomes is achieved after detergent-free fixation, presumably after polarity is lost across single membranes but is maintained by the double membranes of autophagosomes. However, there is confusion in the literature as to the importance of fixation in the use of MDC. In the absence of fixation, this stain is probably no more a specific autophagosome stain than are LysoTracker or DAMP.

The quantification of autophagosome formation has relied primarily on biochemical assays for cytosolic sequestration. Sequestration assays for lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and [3H]-labelled inert sugars can be used to measure the amount of sequestered cytosolic material that is trapped within autophagic structures after separation of membranes from the cytosol14,36. The quantification of sequestered LDH is an excellent assay, but it is predicted to underestimate the amount of cytoplasm trapped by autophagosome formation because any LDH that has progressed to autolysosomes will be degraded.

To monitor the end-point of the autophagic pathway — the degradation of engulfed cytosolic constituents — the destruction of long-lived proteins can be measured. Cells are usually metabolically labelled with [3H]-leucine or [14C]-valine and are then incubated in the absence of labelled amino acids for 48 h to allow short-lived proteins to be degraded. The rate of loss of the remaining labelled protein is then determined; autophagy is associated with an increase in this rate36. The analysis of changes in the degradation rate of long-lived proteins has long been considered to be the best method to diagnose autophagy. However, as many microorganisms themselves encode proteases, potentially causing the overestimation of autophagic processes, and can inhibit autophagosomal maturation, potentially causing the underestimation of autophagosome formation, this method should used in combination with other assays.

The discovery of the ATG genes and other genes that are required for autophagy in yeast and mammalian cells provides an outstanding method to diagnose whether a process of interest, such as a bacterial or viral infection, requires the wild-type function of these genes. Investigators are now beginning to use the genetics of mice, plants, nematodes and Drosophila, and RNA interference in human cells, to test the effect of eliminating or reducing the expression of these genes on processes of interest, such as development, transformation and microbial infection. The attribution of any effect of reduced gene function to the effect of that gene on autophagy clearly relies on the assumption that the only function of that gene is in autophagy. Nevertheless, the newly identified homologues of the yeast ATG genes provide powerful new tools to dissect the mechanism of autophagy and its role in many cellular processes of interest.

Bacterial susceptibility to autophagy

A relationship between autophagy and bacterial infection has been postulated in the infection of the plant Astragalus sinicus by Mesorhizobium huakuii37. The bacteria differentiate within membrane-bound compartments, showing an altered morphology, until they can fix nitrogen and enter into a symbiotic relationship with the plant. Evidence of bacterial degradation has been seen in conditions of nutrient starvation in infected plant nodules. This has led to the hypothesis that autophagy, which is potentially induced by nutrient depletion in the soil, causes the plant to destroy infecting bacteria before their differentiation into a nitrogen-fixing form, as there would be no advantage to the plant to support the symbiont under these conditions.

One of the first examples of bacteria being found within potentially autophagic structures was the observation of Rickettsiae species in double-membrane-bound vesicles that contained acid phosphatases38. Subsequently, correlations between the presence of double-membrane-bound structures and bacterial destruction were shown. The growth of Rickettsia conorii was found to be sensitive to interferon (IFN) or tumour-necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) treatment of host mice or mouse-derived cells, and these cytokine treatments correlated with increases in cellular nitric oxide (NO) production39,40,41. In the presence of these cytokines, EM imaging of infected mouse endothelial cells clearly showed bacteria surrounded by double membranes, and in some cases the bacteria seemed to be damaged, perhaps due to degradation42. It was also shown that providing an intracellular NO donor could partially mimic the anti-rickettsial effects of cytokines and that a competitive inhibitor of NO synthesis could abrogate these effects42. NO is known to play an important antimicrobial role in innate immunity, which suggests the possibility that NO production directly activates autophagy as a mechanism for killing invading bacteria. Alternatively, it is possible that bacteria are killed by reactive oxygen species and are subsequently taken up by autophagosomes for degradation. It would be interesting to determine whether treatment with NO donors has a direct effect on autophagy and to look for potential correlations between NO production, autophagy and bacterial survival.

A recent report indicates that Listeria monocytogenes can be targeted by autophagosomes43. L. monocytogenes normally enters host cells by phagocytosis, after which the bacteria escape from the phagosome and multiply within the host-cell cytoplasm. Mutant ΔactA bacteria, which are incapable of polymerizing actin, can escape from the entry phagosomes but are defective in the ability to spread intracellularly and intercellularly and become engulfed by double-membrane-bound vesicles. Treatment with wortmannin, which is known to inhibit autophagy, reduces bacterial entry into these putative autophagosomes, whereas serum starvation of infected cells was found to increase bacterial uptake into the membranous vacuoles. Furthermore, bacteria-filled autophagosomes have been identified by EM imaging and by the colocalization of LAMP1 and bacterial antigens43.

Infection by the intracellular bacterium Salmonella typhimurium is known to kill human macrophages by two different routes: a rapid, apoptotic route that is mediated by the binding of the secreted bacterial protein SipB to host caspase 1 (Ref. 44) and a slower, caspase-1-independent mechanism. The ultrastructure of caspase 1−/− macrophages that are infected with wild-type S. typhimurium, but not those that are infected with type-III-secretion-defective SipD mutant bacteria, shows characteristics of autophagy, such as post-fixation staining with MDC and increased numbers of multilamellar vesicles45. However, as for all the examples in this section, it is not yet known if the apparently autophagic structures that are induced during S. typhimurium infection of macrophages have any role in restricting bacterial growth.

Bacterial subversion of the autophagic pathway

In contrast to those described above, several types of bacteria can subvert the autophagic pathway and replicate inside compartments that are decorated with characteristic components of autophagosomes. For example, Porphyromonas gingivalis, which can infect human coronary-artery endothelial cells, has been shown to localize to membranous compartments that are suspected to be autophagosomes because of the presence of ER markers early in the bacterial replication cycle and the later addition of lysosomal markers46,47. When wortmannin was added to the host cells, which presumably prevents the initial formation of autophagosome-like structures, a qualitative change in the bacterial vacuole was seen: the vesicles resembled lysosomes rather than autophagosomes and acquired cathepsin L earlier in their formation and before ER markers were acquired. In terms of function, the survival of intracellular P. gingivalis was greatly reduced in the presence of either 3-MA or wortmannin, which indicates that the lysosomal fate that was apparently caused by these treatments was detrimental to the bacteria.

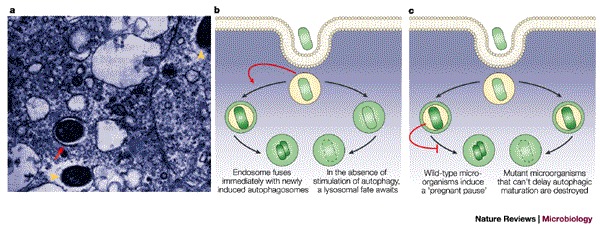

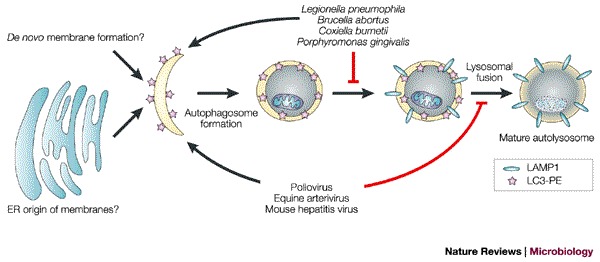

Most examples of potential autophagic subversion by bacteria require the function of bacterial type IV secretion pathways, which are homologous to conjugal plasmid-transfer systems and bring about the uptake of bacterial proteins into infected cells. For example, after endosomal uptake into mammalian cells, Brucella abortus localizes to structures that resemble autophagosomes as they have double membranes and display markers from the ER and late endosomes48,49. Consistent with a positive role for autophagy or autophagic components in bacterial replication, both 3-MA and wortmannin were found to reduce Brucella growth, whereas host-cell starvation slightly increased bacterial yield. The Brucella virB operon encodes members of a type IV secretion pathway, virB mutants are defective in normal intracellular transport and growth50,51, and the compartments they localize to acquire cathepsin D almost immediately. For both P. gingivalis and B. abortus, it has been proposed that, on entry into cells, the bacteria immediately enter newly induced autophagosomes. Failure to enter autophagosomes, due to wortmannin treatment or virB mutations, results in the bacteria being taken up by lysosomes and degraded, as shown in Fig. 3b47,48,52.

Figure 3. Autophagic sequestration of bacteria.

a | Electron micrograph of Rickettsia conorii infecting mouse endothelial cells 36 h after inoculation and addition of cytokines. The arrow indicates a rickettsial cell that is contained within a double-membrane-bound compartment. Arrowheads indicate intact R. conorii in the cytosol. b | A situation in which bacterial infection stimulates autophagosome function (red arrow) and the bacteria avoid a phagosomal fate, as has been proposed for Porphyromonas and Brucella infection. c | A situation in which bacterial infection delays autophagosome formation (red blunt-ended arrow), as has been proposed for Legionella and Rickettsia infection. a reproduced with permission from Ref. 42 © (1997) Nature Publishing Group.

One well-studied example of a bacterium that relies on a type IV secretion pathway to avoid a lysosomal fate is Legionella pneumophila, which is a Gram-negative pathogen that can replicate within human macrophages. In experiments that have implicated the autophagic machinery in the formation of the membranous vacuoles inside which Legionella replicates, these compartments have been shown by EM to be surrounded by double membranes and to contain markers such as the ER-resident protein BiP, the lysosomal/endosomal marker LAMP1 and, in a smaller percentage of vesicles, the lysosomal protein cathepsin D53,54,55,56. Genes for which mutations cause defects in organelle trafficking or intracellular multiplication — known as the dot or icm genes — are required for Legionella replication in human macrophages, but not in bacterial growth medium. Legionella bacteria in which the dot/icm genes are mutated were shown to be mistargeted early in infection and did not localize to double-membrane-bound vesicles, but to vesicles with late endosomal or lysosomal characteristics55,57,58,59. Further work showed that the dot/icm genes encode the proteins of a type IV secretion system60,61,62. In the 'pregnant pause' model11, Legionella and other vacuole-associated pathogens enter the cell and localize to autophagosomes. Then, through the action of bacterial proteins that require the type IV secretion apparatus to enter the host cytoplasm, the maturation of these autophagosome-like structures into autolysosomes is delayed. It has been proposed that this delay gives the microorganisms time to develop into replicative forms that can withstand the environment of the autolysosome (Fig. 3c).

However, the autophagosomal origin of the Legionella replication compartments has been disputed. Some ultrastructural EM analyses have shown structures that seem to be rough ER surrounding the bacteria63. In addition, formation of the compartment was shown to be sensitive to dominant-negative alleles of SAR1 and ARF1, genes that encode small GTP-binding proteins that are classically involved in traffic between the ER and the Golgi apparatus64. In D. discoideum, which is a natural host for Legionella, loss-of-function alleles of the atg1, atg5, atg6, atg7 and atg8 genes showed the expected defects in autophagy, but there was no effect either on the growth of L. pneumophila or on the morphology of its replication compartments65. It is, of course, possible that the bacterium uses different replication strategies in these different hosts. Now that analogous genetic approaches can be used in mammalian cells, it will be possible to test whether loss-of-function alleles of genes that are required for autophagy affect the function, composition or ultrastructure of the Legionella replication compartments in human macrophages.

A bacterium that is closely related to Legionella, Coxiella burnetii, is the causative agent of Q fever. Like Legionella, C. burnetii has been shown to replicate within acidic vesicles66,67. These Coxiella replication compartments also show some autophagic characteristics, such as labelling with the autophagy-specific marker LC3, as well as lysosomal and late endosomal markers34,66,68,69,70,71. Expression of a dominant-negative form of Rab7 altered the size and number of these Coxiella-containing compartments, consistent with a role for lysosomal fusion in their maturation34. If the autophagic pathway is involved in the formation of these compartments, lysosomal fusion ability could affect either the autophagic induction or pregnant pause models for the bacterial use of autophagic constituents, and these ideas are clearly not mutually exclusive. The isolation of effector molecules that induce autophagosome formation, delay autophagosome maturation, or both, would strengthen the case for a role for autophagy in the formation of replication vacuoles and would allow the autophagy induction and pregnant pause models to be tested further. It may be found that there are common mechanisms by which bacteria subvert cellular autophagy. Consistent with this view, the dot/icm homologues that are found in Coxiella were shown to rescue the growth defects of Legionella bacteria with dot/icm mutations72. Whether the molecules that are transported by these interchangeable type IV secretion machines have similar functions, however, remains to be tested.

Are there likely candidates for type-IV-secretion-dependent factors that delay autophagosome maturation? The leading candidates are factors that are expressed in both Legionella and Rickettsia and that display homology to the eukaryotic SEC7 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor, which is known to be involved in membrane fusion and transport60. The Legionella SEC7 homologue, RalF, has been shown to be secreted in a type-IV-dependent manner, and recruits the cellular ADP ribosylation factor ARF1 to the membrane of the Legionella phagosome. It is possible, therefore, that RalF might play a role in altering the trafficking of that vacuole62. Although mutations in ralF did not affect the yield of intracellular bacteria62, it is possible that its function in the intracellular growth of Legionella, if any, is redundant in human macrophages.

With regard to possible inducers of autophagy that are secreted by bacteria, one candidate is the Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin VacA, which has multiple effects, including induction of apoptosis, cytochrome c release and inhibition of T-cell activation, depending on the cell type73. Among its many effects, VacA has been shown to induce the proliferation of acidic vacuoles that bear late endosomal and lysosomal markers and might, on further investigation, show other hallmarks of autophagosomes73,74,75.

Autophagy and viruses: avoidance and surrender

A direct role for autophagy in the clearance of herpesvirus from infected cells has been indicated by studies of the course of viral infection in cells that differ in their expression of the double-stranded-RNA-activated protein kinase PKR, a crucial component of the cellular antiviral response (Box 1). One of the functions of activated PKR is to phosphorylate the eukaryotic translation-initiation factor eIF2α and thereby inhibit and deregulate cellular translation. Herpes simplex virus 1 encodes a protein, ICP34.5, that antagonizes this function by redirecting a cellular phosphatase to dephosphorylate eIF2α. The reduction in herpesvirus growth that is caused by the deletion of the gene encoding ICP34.5 was shown to be completely reversed in mice that lack PKR76. Therefore, the sole purpose of the herpesvirus ICP34.5 gene is likely to be to counteract the effects of PKR activation.

What are the antiviral effects of PKR? PKR activation is known to alter cellular translation, induce apoptosis and activate nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), as well as having other, less well-characterized effects (Box 1)77. As shown by Tallozcy et al.78, one of the downstream consequences of PKR activation is the activation of autophagy. The infection of wild-type mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) with wild-type herpesvirus did not cause a significant increase in the amount of degradation of long-lived proteins or an increase in the total volume of autophagic vacuoles78. However, similar infections with herpesviruses in which the ICP34.5 gene has been deleted showed an increase in both of these indicators of autophagy, whereas no increased autophagy was seen when either mutant or wild-type herpesvirus-infected PKR−/− MEFs78. Therefore, PKR activation is necessary for the increased autophagy that is seen during infection with ΔICP34.5 herpesviruses.

What is the signalling pathway that leads from activated PKR to increased autophagy? MEFs that express only a mutant version of eIF2αthat cannot be phosphorylated showed no increase in autophagy when they were infected with a ΔICP34.5 herpesvirus78. Therefore, both PKR and a phosphorylatable version of eIF2α are necessary for the induction of autophagy by herpesvirus; whether they are sufficient is not yet known.

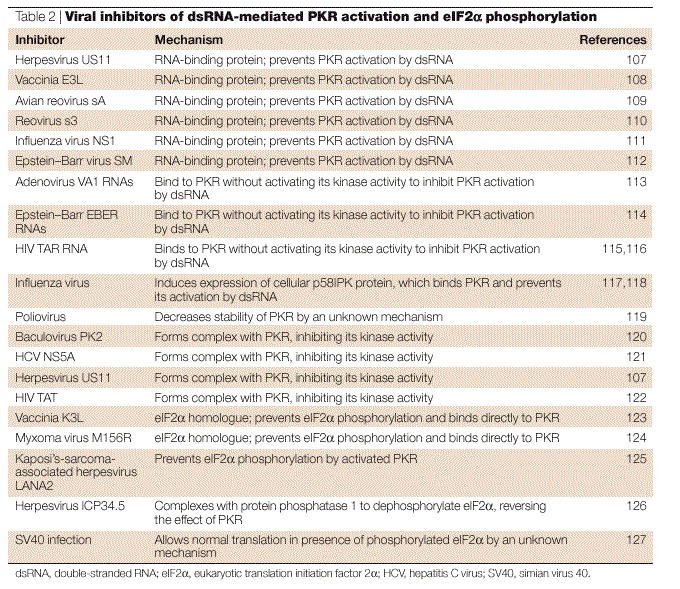

Is autophagy the specific PKR-induced antiviral response that reduces the yield of ΔICP34.5 herpesviruses relative to that seen with wild-type viruses, thus indicating that one of the functions of ICP34.5 is to prevent autophagy? By stimulating the dephosphorylation of eIF2α, ICP34.5 should antagonize any downstream effects of eIF2α phosphorylation by PKR (Box 1), of which autophagy is as likely a candidate as any other. Indeed, one of the effects of blocking eIF2α phosphorylation using the inhibitors shown in Table 2 might be to inhibit the induction of autophagy.

Table 2.

Viral inhibitors of dsRNA-mediated PKR activation and eIF2α phosphorylation

Autophagy and viruses: subversion

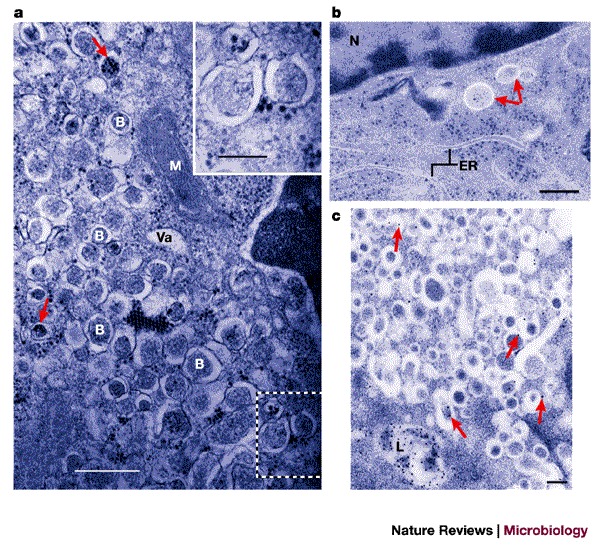

Some of the first EM analyses of virus-infected cells were performed in the laboratory of George Palade. Studies of cells that were infected with poliovirus (Fig. 4a) showed the presence of large numbers of membranous vesicles with diameters of 200–400 nm, which — due to the 'cytoplasmic matrix' present in the lumen of the vesicles — were postulated to “develop by a mechanism comparable to that of the formation of autolytic vesicles”79.

Figure 4. Formation of double-membrane-bound vesicles during poliovirus infection.

| a | Electron micrograph of a chemically fixed, poliovirus-infected HeLa cell 7 h post-infection. 'B' indicates the apparently cytosolic lumens of double-membrane-bound vesicular bodies. 'Va' indicates a vacuole that does not seem to be multilamellar. 'M' indicates a mitochondrion. Poliovirus particles, either single or in groups, can be seen in the cytoplasm and, occasionally, within the lumen of the double-membrane-bound vesicles (arrows). The inset shows the region outlined by dashed white lines in the main image at a higher magnification. Scale bar in main image, 0.6 μm; scale bar in inset, 0.25 μm. b | Electron micrograph of poliovirus-infected HeLa cells 2.5 h post-infection preserved by high-pressure cryopreservation and freeze substitution. Arrows indicate double-membrane-bound structures with apparently cytosolic lumens that are similar to those seen at later times after infection. Membranes that have distributions and morphologies that are characteristic of the endoplasmic reticulum are indicated (ER). 'N' indicates the nucleus. Scale bar, 0.2 μm. c | Immunolocalization of the late endosomal/lysosomal protein LAMP1 in poliovirus-infected HeLa cells 4.5 h post-infection. Arrows indicate selected gold particles coupled to a secondary antibody. 'L' indicates a lysosome. Scale bar, 0.2 μm. a reproduced with permission from Ref. 79 © (1965) Elsevier Science; b and c reproduced with permission from Ref. 85 © (1996) ASM.

Positive-strand RNA viruses all require membrane surfaces on which to assemble their RNA-replication complexes80,81. Several hypotheses have been proposed for the origin of these membranes, which include the ER for hepatitis C virus82, the outer mitochondrial membrane for flock-house virus83 and autophagic membranes for poliovirus (Refs 79,84,85; W. T. J. et al., unpublished observations). Our laboratory has hypothesized that one of the functions of the membrane localization of poliovirus RNA replication complexes is — as has also been suggested for the DNA phage Φ29 (Refs 86,87) — that intracellular membranes provide a two-dimensional surface on which to assemble the regular oligomeric lattices of viral proteins that are required for cooperative binding to the substrate RNA88.

For a handful of positive-strand viruses, specifically poliovirus, equine arterivirus (EAV) and murine hepatitis virus (MHV), evidence has accumulated that the membranes on which RNA replication complexes form resemble autophagosomes, contain known components of the autophagic pathway, or both. For poliovirus, our laboratory has pursued the original observations of Palade and co-workers to show that the membranes that are induced during poliovirus infection resemble autophagosomes due to the double-membrane-bound morphology that is present even early in infection (Fig. 4b), their labelling with anti-LAMP1 (Fig. 4c) and their low buoyant densities84. Recently, proteins of the poliovirus RNA-replication complex were shown to colocalize with a cotransfected green fluorescent protein (GFP)–LC3 fusion protein, which is a known marker of autophagosomes (Table 1). Within 3 hours of poliovirus infection, GFP–LC3 and LAMP1 were shown to colocalize, whereas in uninfected cells no colocalization was seen (W. T. J. et al., unpublished observations). An alternative source for the poliovirus-induced vesicles, however, has been indicated by the presence of the human homologues of the yeast Sec31 and Sec13 proteins, both of which are components of the COPII coat of anterograde transport vesicles that bud from the ER89. One possible explanation for this observation might be provided by the finding that, in yeast, mutations in the genes that encode COPII coat proteins lead to defects in autophagy90,91. It is therefore possible, although it has not yet been tested, that the COPII proteins are normal components of the autophagic machinery or that they can, under some circumstances, associate with them.

Colocalization of poliovirus RNA-replication complexes with autophagosomes or autophagosomal components might result either from the use of these components by the viral replication complex or the destruction of the viral structures by the autophagic machinery. If the latter scenario were correct, one would expect the pre-induction of autophagy by rapamycin or tamoxifen treatment to reduce viral yield. However, the opposite effect was produced: treatment with either rapamycin or tamoxifen increased poliovirus yield 3–5-fold (W. T. J. et al., unpublished observations). It is therefore likely that the autophagic machinery does not have a destructive role during poliovirus infection and instead contributes to the formation of viral RNA-replication complexes. If the poliovirus-induced membranes are derived from the autophagic pathway, it is probably because of the preponderance of double-membrane-bound structures that viral products delay the maturation of the autophagosome-like structures into degradative compartments, as has been proposed for Legionella (Fig. 3).

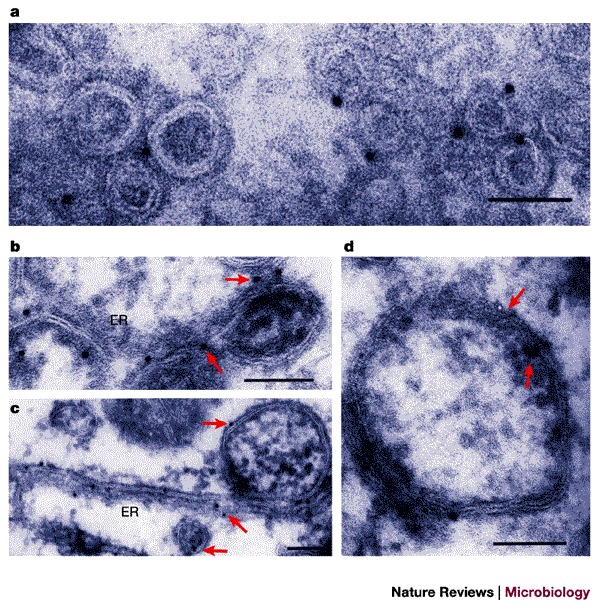

EAV and MHV are both members of the Nidovirales, the order of RNA viruses that includes the recently identified human coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). During infection with EAV, MHV or the SARS coronavirus, membranous vesicles that are bounded by double lipid bilayers accumulate92,93,94,95. In EAV-infected cells (Fig. 5a), these vesicles were found to be 80–100 nm in diameter94, whereas MHV-infected cells contained double-membrane-bound vesicles that were closer in size to those seen in poliovirus-infected cells, with a diameter of 200–350 nm (Ref. 93). Immunoelectron microscopy showed that proteins of the RNA-replication complexes and newly synthesized, bromouridine-labelled RNA were found in direct association with the double-membrane-bound vesicles93,94,96,97.

Figure 5. Formation of double-membrane-bound vesicles during EAV infection and on expression of EAV proteins nsp2 and nsp3.

a | RK-13 cells were infected with equine arterivirus (EAV) for 8 h and cryosections were labelled with anti-nsp2 followed by protein-A–gold detection. Scale bar, 0.1 μm. b–d | Cryoimmunoelecron microscopy of RK-13 cells in which EAV proteins nsp2 and nsp3 were expressed in precursor forms using a Sindbis virus vector. Gold labelling detects nsp2 (a,c) and nsp3 (d); arrows indicate selected gold particles. Cells were harvested 8–12 h after infection. Scale bars, 0.1 μm. ER, endoplasmic reticulum. a Reproduced with permission from Ref. 94 © (1999) ASM. b–d Reproduced with permission from Ref. 100 © (2001) Society for General Microbiology.

In the case of MHV, the presence of cellular markers on the virally induced membranes is consistent with their derivation from the autophagic pathway: late endosomal proteins and LC3 were both found to co-localize with viral RNA-replication proteins on these membranes98,99. In addition, the degradation of long-lived proteins increased from 1.3% to 2% in infected cells98. Importantly, the yield of extracellular virus was diminished 1000-fold in clonal isolates of Atg5−/− mouse embryonic stem cells and the wild-type yield was restored by plasmids that express Atg5 (Ref. 98). The reduction in viral yield in the absence of a crucial component of the autophagic machinery clearly indicates that this pathway does not function primarily to degrade this virus. Instead, this strongly indicates that wild-type Atg5 is required for the formation of infectious MHV virions, either as a host factor that is directly involved in this process or, assuming that its only function in mammalian cells is in the autophagy pathway, by allowing the formation of autophagic membranes, presumably to function as a platform for RNA replication. Such a spectacular reduction in yield as a result of eliminating the presence of a certain type of membrane within an infected cell is, perhaps, surprising. When the RNA-replication complex of flock-house virus, a positive-strand RNA virus that can replicate its genome in S. cerevisiae, was re-directed from its normal mitochondrial location to the ER, the efficiency of RNA replication, instead of being reduced, was increased sixfold84. It will be of great interest to determine the reason for the strong requirement for Atg5 in the production of extracellular MHV. This might be because Atg5 has a direct role in this process, because it helps to induce autophagic membranes, or because of some other function of Atg5.

The systematic expression of viral proteins individually and in combination has identified the first virally encoded molecular inducers of the formation of double-membrane-bound vesicles: the poliovirus proteins 2BC and 3A and the EAV proteins nsp2 and nsp3. Figure 5 compares the ultrastructure and immunostaining of membranes that are induced during EAV infection (Fig. 5a) and in the presence of the EAV proteins nsp2 and nsp3 (Fig. 5b–d)100. Similarly, poliovirus-infected cells were found to have morphologies similar to those of cells that express only the viral proteins 2BC and 3A84. Membranes that are formed in the presence of 2BC and 3A also resemble those that are formed in poliovirus-infected cells in terms of their low buoyant density and their staining with both LC3 and LAMP1, as visualized by immunofluorescence (W. T. J. et al., unpublished observations).

The mechanism by which RNA-virus proteins induce double-membrane-bound vesicles using components of the autophagic pathway is not yet known. An understanding of the disparate sizes of the vesicles that are induced by different viruses, and by the autophagic pathway itself, will await the identification of the proteins that confer membrane curvature. Both EAV proteins, as well as poliovirus 2C, contain nucleoside 5′-triphosphate (NTP)-binding motifs101. Curiously, the ultrastructure of cells that express both poliovirus 3A and 2C, but not the precursor 2BC, strongly resembles that of MHV-infected Atg5−/− cells, with apparently ER-derived membranes that contain cytoplasmic invaginations84,98. It is tempting to speculate that these structures represent intermediates in membranous-vesicle formation, in which membranes have invaginated but have not resolved into autonomous vesicles.

Summary

As shown schematically in Fig. 6, several different intracellular bacteria and positive-strand RNA viruses have been suggested to both stimulate the accumulation of membranes that bear autophagic markers and to inhibit their maturation. Why do certain viruses and intracellular bacteria use proteins, and possibly membranes, that are derived from the autophagic pathway? In the case of bacteria that replicate within compartments that bear features of autophagosomes, this might provide an environment that is cytoplasmic but protected, which shields the bacteria from host responses. It is possible that the viruses and bacteria discussed here use the highly inducible cellular autophagy pathway to proliferate required membranes without triggering cellular defences. The stepwise maturation of the resulting compartments (Fig. 2) might allow the fine-tuning of the pH, or the protein or lipid composition, depending on which steps are induced or inhibited (Fig. 6). Finally, the cytoplasmic lumens of double-membrane-bound vesicles that are formed during poliovirus infection, for example, sometimes contain progeny virions (Fig. 4a). These vesicles are likely to be those that are formed late in infection, so that the engulfed cytoplasm already contains mature viral particles. These virions may be destined for destruction by bona fide autophagy. However, it is also possible that the unique topology of double-membrane-bound vesicles allows a certain amount of extracellular delivery of obligate intracellular microorganisms without cell lysis. Infectious poliovirus is known to be able to exit from the apical surface of polarized cell monolayers without a breach in the integrity of the epithelial sheet102; the mechanism of such documented examples of non-lytic cell exit by this and other 'lytic' viruses is not yet known.

Figure 6. Potential subversion of the autophagic pathway or its components by bacteria and viruses.

Proposed stages at which intracellular bacteria and viruses might induce or interfere with autophagosome development. The viruses and bacteria listed induce the formation of double-membrane-bound compartments that bear markers from the autophagic pathway. The persistence of the double-membrane-bound morphology of these structures indicates that, if they are similar to autophagosomes, their maturation into autolysosomes is arrested. In Legionella, membranes show delayed acquisition of lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1), whereas the poliovirus-induced membranes contain LAMP1; therefore, Legionella and poliovirus are proposed to block autophagic maturation at different steps. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; LC3, microtubule-associated-protein light-chain 3; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine.

The interactions between the autophagic pathway and the infectious cycles of intracellular bacteria and viruses are complex. Many microorganisms are undoubtedly engulfed during the destructive process of autophagosome formation and maturation into autolysosomes. It is also likely that successful microorganisms, such as the viruses that have evolved to inhibit eIF2α phosphorylation by PKR, can at least partially avoid this destruction. Several bacteria and viruses seem to use components of the autophagic pathway to facilitate their replication. Understanding the mechanisms by which autophagic components are usurped by microorganisms and the molecules that are involved in this might be instrumental in dissecting the process of cellular autophagy, as well as in its subversion.

Note added in proof

Recently, a genetic screen has identified multiple novel protein substrates of the Legionella pneumophila dot/icm translocation apparatus, all of which are potential candidates for the molecular effectors of the host-membrane rearrangements that accompany Legionella infection. See Ref. 128 for details.

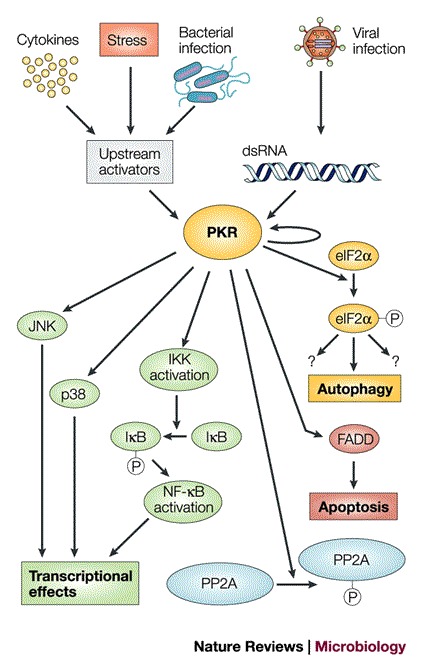

Box 1 | Signalling pathways involving PKR.

What is perhaps the most convincing evidence that the activation of PKR is strongly antiviral comes from the fantastic lengths that viruses take to avoid PKR activation and its consequences (Table 2). PKR was originally discovered because of its antiviral role during infection103. Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is often present during viral infections, either as a byproduct of the replication of RNA viruses or as a product of overlapping transcription from the compact genomes of DNA viruses. dsRNA is a known allosteric effector of PKR and causes a conformational change in PKR, which is followed by its dimerization and activation of its kinase activity. On activation, PKR phosphorylates several substrates, including other PKR monomers, the regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), and the eukaryotic translation initation factor eIF2α. Phosphorylation is known to increase the activity of the PP2A complex, which has many targets. Phosphorylation of eIF2α prevents the recycling of the eIF2–GDP complex, which drastically inhibits most translational initiation — both host and viral — which requires the initiator transfer RNA, tRNAmet. Some messenger RNAs, however, are selectively translated under conditions of eIF2α phosphorylation. These include those that require the use of an alternative AUG codon. Reducing the frequency of productive initiation can allow scanning through upstream AUGs104,105. Therefore, PKR activation by dsRNA, which is usually described as inhibiting translation, is likely to have more subtle effects on translation than simple inhibition and might actually activate the translation of some mRNAs, especially those with upstream open reading frames.

PKR activation also activates nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)77 — a known participant in host antiviral responses — but this occurs through a mechanism that is not thought to require the phosphorylation of eIF2α or PP2A. Other genes and gene products whose expression is affected by PKR stimulation are shown in the figure. Most of the signal transduction pathways in which PKR is activated do not use the dsRNA activation mechanism, but instead use various upstream effectors, some of which are themselves kinases and can phosphorylate PKR directly.

The mechanisms of action of viral factors that are known to avoid inhibition by PKR (Table 2) include RNAs that bind to PKR without activating it, proteins that titrate dsRNA, and eIF2α decoys that serve as targets for activated PKR and so protect the real translational machinery. Another viral PKR inhibitor, the ICP34.5 gene product that is encoded by herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV1), binds to protein phosphatase 1a, causing it to dephosphorylate eIF2α and so reverse the effects of phosphorylation of eIF2α by PKR106. Presumably, the expression of ICP34.5 — or any other viral product that neutralizes the effect of eIF2α phosphorylation by PKR — would also reverse PKR phosphorylation by any of the three other cellular eIF2α kinases in mammalian cells. These are GCN2, which is activated during amino-acid starvation; pancreatic ER kinase (PERK), which is activated during endoplasmic reticulum stress; and haem-regulated eIF2α kinase (HRI), which is activated during haem depletion77. FADD, FAS-associated death domain; IκB, inhibitor of NF-κB; IKK, IκB kinase; JNK, c-JUN amino-terminal kinase.

Acknowledgements

We thank P. Sarnow and M. Brahic for critical comments on the text, and R. Kopito, T. H. Giddings Jr, P. Codogno, E. Baehrecke and M. Swanson for helpful discussions. The Kirkegaard laboratory is supported by the NIH and the Ellison Foundation.

Glossary

- DAUER

An arrested stage in Caenorhabditis elegans development that can be formed in conditions of starvation or overcrowding.

- PEROXISOME

A single-membrane-bound organelle that performs many metabolic functions.

- RAPAMYCIN

An immunosuppressive macrolide that inhibits the proliferation of T and B cells and was originally isolated from Streptomyces hygroscopicus.

- TAMOXIFEN

An antagonist of oestrogen that is used in the treatment of breast cancer.

- OKADAIC ACID

A specific inhibitor of protein phosphatases that acts as a tumour promoter. Okadaic acid is the toxin responsible for diarrhaetic shellfish poisoning.

- UBIQUITYLATION

Proteins tagged with ubiquitin can be recognized by the proteasome and degraded.

- CATHEPSIN

A lysosomal protease that functions optimally within an acidic pH range.

- COPII

Newly synthesized proteins that are destined for secretion are sorted into vesicles coated with COPII components at endoplasmic-reticulum exit sites.

Biographies

Karla Kirkegaard is a Professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at Stanford University School of Medicine and an Ellison Senior Scholar in Global Infectious Disease.

Matthew P. Taylor is a Ph.D. student and William T. Jackson a postdoctoral fellow, both in the Kirkegaard laboratory. They investigate the mechanisms of membrane rearrangements in human and yeast cells induced by poliovirus- and rhinovirus-encoded proteins.

Related links

DATABASES

Entrez

LocusLink

Infectious Disease Information

FURTHER INFORMATION

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Stromhaug PE, Klionsky DJ. Approaching the molecular mechanism of autophagy. Traffic. 2001;2:524–531. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.20802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klionsky DJ, et al. A unified nomenclature for yeast autophagy-related genes. Dev. Cell. 2003;5:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00296-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang XH, et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–676. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melendez A, et al. Autophagy genes are essential for dauer development and life-span extension in C. elegans. Science. 2003;301:1387–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.1087782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otto GP, Wu MY, Kazgan N, Anderson OR, Kessin RH. Macroautophagy is required for multicellular development of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:17636–17645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doelling JH, Walker JM, Friedman EM, Thompson AR, Vierstra RD. The APG8/12-activating enzyme APG7 is required for proper nutrient recycling and senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:33105–33114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanaoka H, et al. Leaf senescence and starvation-induced chlorosis are accelerated by the disruption of an Arabidopsis autophagy gene. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:1181–1193. doi: 10.1104/pp.011024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith JD, de Harven E. Herpes simplex virus and human cytomegalovirus replication in WI-38 cells. J. Virol. 1978;26:102–109. doi: 10.1128/jvi.26.1.102-109.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guidotti LG, et al. Viral clearance without destruction of infected cells during acute HBV infection. Science. 1999;284:825–829. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaible UE, et al. Parasitophorous vacuoles of Leishmania mexicana acquire macromolecules from the host cell cytosol via two independent routes. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:681–693. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.5.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swanson MS, Fernandez–Moreia E. A microbial strategy to multiply in macrophages: the pregnant pause. Traffic. 2002;3:170–177. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.030302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuma A, Mizushima N, Ishihara N, Ohsumi Y. Formation of the approximately 350-kDa Apg12–Apg5–Apg16 multimeric complex, mediated by Apg16 oligomerization, is essential for autophagy in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:18619–18625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111889200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stromhaug PE, Berg TO, Fengsrud M, Seglen PO. Purification and characterization of autophagosomes from rat hepatocytes. Biochem. J. 1998;335:217–224. doi: 10.1042/bj3350217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kopitz J, Kisen GO, Gordon PB, Bohley P, Seglen PO. Nonselective autophagy of cytosolic enzymes by isolated rat hepatocytes. J. Cell Biol. 1990;111:941–953. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchener JS, Shelburne JD, Bradford WD, Hawkins HK. Cellular autophagocytosis induced by deprivation of serum and amino acids in HeLa cells. Am. J. Pathol. 1976;83:485–491. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn WAJr. Studies on the mechanisms of autophagy: formation of the autophagic vacuole. J. Cell Biol. 1990;110:1923–1933. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.6.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizushima N, et al. Dissection of autophagosome formation using Apg5-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells. J. Cell Biol. 2001;152:657–668. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cutler NS, Heitman J, Cardenas ME. TOR kinase homologs function in a signal transduction pathway that is conserved from yeast to mammals. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1999;155:135–142. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(99)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bursch W, et al. Autophagic and apoptotic types of programmed cell death exhibit different fates of cytoskeletal filaments. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113:1189–1198. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.7.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogier-Denis E, Bauvy C, Houri J, Codogno P. Evidence for a dual control of macroautophagic sequestration and intracellular trafficking of N-linked glycoproteins by the trimeric Gi3 protein in HT-29 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;235:166–170. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petiot A, Ogier-Denis E, Blommaart EF, Meijer AJ, Codogno P. Distinct classes of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases are involved in signaling pathways that control macroautophagy in HT-29 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:992–998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pattingre S, Bauvy C, Codogno P. Amino acids interfere with the ERK1/2-dependent control of macroautophagy by controlling the activation of Raf-1 in human colon cancer HT-29 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;276:16667–16674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210998200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holen I, Gordon PB, Seglen PO. Inhibition of hepatocytic autophagy by okadaic acid and other protein phosphatase inhibitors. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;215:113–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizushima N, Sugita H, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. A new protein conjugation system in human. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:33889–33892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.33889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohsumi Y. Molecular dissection of autophagy: two ubiquitin-like systems. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:211–216. doi: 10.1038/35056522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizushima N, et al. A protein conjugation system essential for autophagy. Nature. 1998;395:395–398. doi: 10.1038/26506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. Mouse Apg10 as an Apg12 conjugating enzyme: analysis by the conjugation-mediated yeast two-hybrid method. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:450–454. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03739-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanida I, Tanika-Miyaki E, Komatsu M, Ueno T, Kominami E. The human homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Apg7p is a protein-activating enzyme for multiple substrates including human Apg12p, GATE-16, GABARAP, and MAP-LC3. J. Biol Chem. 2002;276:1701–1706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000752200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kabeya Y, et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19:5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Punnonen EL, Autio S, Marjomaki VS, Reunanen H. Autophagy, cathepsin L transport, and acidification in cultured rat fibroblasts. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1992;40:1579–1587. doi: 10.1177/40.10.1326577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nuoffer C, Balch WE. GTPases: multifunctional molecular switches regulating vesicular traffic. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1994;63:949–990. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.004505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munafo DB, Colombo MI. Induction of autophagy causes dramatic changes in the subcellular distribution of GFP–Rab24. Traffic. 2002;3:472–482. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munafo DB, Colombo MI. A novel assay to study autophagy: regulation of autophagosome vacuole size by amino acid deprivation. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:3619–3629. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beron W, Gutierrez MG, Rabinovitch M, Colombo MI. Coxiella burnetii localizes in a Rab7-labeled compartment with autophagic characteristics. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:5816–5821. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5816-5821.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biederbick A, Kern HF, Elsasser HP. Monodansylcadaverine (MDC) is a specific in vivo marker for autophagic vacuoles. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1995;66:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seglen PO, Gordon PB. Amino acid control of autophagic sequestration and protein degradation in isolated rat hepatocytes. J. Cell Biol. 1984;99:435–444. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobayashi H, Sunako M, Hayashi M, Murooka Y. DNA synthesis and fragmentation in bacteroids during Astragalus sinicus root nodule development. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001;65:510–515. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rikihisa Y. Glycogen autophagosomes in polymorphonuclear leukocytes induced by rickettsiae. Anat. Rec. 1984;208:319–327. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092080302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turco J, Winkler HH. Role of the nitric oxide synthase pathway in inhibition of growth of interferon-sensitive and interferon-resistant Rickettsia prowazekii strains in L929 cells treated with tumor necrosis factor-α and γ-interferon. Infect. Immun. 1993;61:4317–4325. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4317-4325.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turco J, Liu H, Gottlieb SF, Winkler HH. Nitric oxide-mediated inhibition of the ability of Rickettsia prowazekii to infect mouse fibroblasts and mouse macrophage-like cells. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:558–566. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.558-566.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng HM, Wen J, Walker DH. Rickettsia australis infection: a murine model of a highly invasive vasculopathic rickettsiosis. Am. J. Pathol. 1993;142:1471–1482. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walker DH, Popov VL, Crocquet-Valdes PA, Welsh CJ, Feng HM. Cytokine-induced, nitric oxide-dependent, intracellular antirickettsial activity of mouse endothelial cells. Lab. Invest. 1997;76:129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rich KA, Burkett C, Webster P. Cytoplasmic bacteria can be targets for autophagy. Cell. Microbiol. 2003;5:455–468. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hersh D, et al. The Salmonella invasin SipB induces macrophage apoptosis by binding to caspase-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:2396–2401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hernandez LD, Pypaert M, Flavell RA, Galan JE. A Salmonella protein causes macrophage cell death by inducing autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 2003;163:1123–1131. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Progulske-Fox A, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis virulence factors and invasion of cells of the cardiovascular system. J. Periodontal. Res. 1999;34:393–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1999.tb02272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorn BR, Dunn WA, Jr, Progulske-Fox A. Porphyromonas gingivalis traffics to autophagosomes in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:5698–5708. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5698-5708.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pizarro-Cerda J, et al. Brucella abortus transits through the autophagic pathway and replicates in the endoplasmic reticulum of nonprofessional phagocytes. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:5711–5724. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5711-5724.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Sanguedolce V, Mege JL, Gorvel JP. Virulent Brucella abortus prevents lysosome fusion and is distributed within autophagosome-like compartments. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:2387–2392. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2387-2392.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Comerci DJ, Martinez-Lorenzo MJ, Sieira R, Gorvel JP, Ugalde RA. Essential role of the VirB machinery in the maturation of the Brucella abortus-containing vacuole. Cell. Microbiol. 2001;3:159–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delrue RM, et al. Identification of Brucella spp. genes involved in intracellular trafficking. Cell. Microbiol. 2001;3:487–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dorn BR, Dunn WA, Jr, Progulske-Fox A. Bacterial interactions with the autophagic pathway. Cell. Microbiol. 2002;4:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Swanson MS. Legionella pneumophila replication vacuoles mature into acidic, endocytic organelles. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:1261–1272. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swanson MS, Isberg RR. Association of Legionella pneumophila with the macrophage endoplasmic reticulum. Infect. Immun. 1995;63:3609–3620. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3609-3620.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joshi AD, Sturgill-Koszycki S, Swanson MS. Evidence that Dot-dependent and -independent factors isolate the Legionella pneumophila phagosome from the endocytic network in mouse macrophages. Cell. Microbiol. 2001;3:99–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coers J, et al. Identification of Icm protein complexes that play distinct roles in the biogenesis of an organelle permissive for Legionella pneumophila intracellular growth. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;38:719–736. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berger KH, Isberg RR. Two distinct defects in intracellular growth complemented by a single genetic locus in Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 1993;7:7–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berger KH, Merriam JJ, Isberg RR. Altered intracellular targeting properties associated with mutations in the Legionella pneumophila dotA gene. Mol. Microbiol. 1994;14:809–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marra A, Blander SJ, Horwitz MA, Shuman HA. Identification of a Legionella pneumophila locus required for intracellular multiplication in human macrophages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:9607–9611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sexton JA, Vogel JP. Type IVB secretion by intracellular pathogens. Traffic. 2002;3:178–185. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.030303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vogel JP, Andrews HL, Wong SK, Isberg RR. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science. 1998;279:873–876. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nagai H, Kagan JC, Zhu X, Kahn RA, Roy CR. A bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factor activates ARF on Legionella phagosomes. Science. 2002;295:679–682. doi: 10.1126/science.1067025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tilney LG, Harb OS, Connely PS, Robinson CG, Roy CR. How the parasitic bacterium Legionella pneumophila modifies its phagosome and transforms it into rough ER: implications for conversion of plasma membrane to the ER membrane. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:4637–4650. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kagan JC, Roy CR. Legionella phagosomes intercept vesicular traffic from endoplasmic reticulum exit sites. Nature Cell Biol. 2002;4:945–954. doi: 10.1038/ncb883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Otto GP, et al. Macroautophagy is dispensable for intracellular replication of Legionella pneumophila in Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:63–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Akporiaye ET, Rowatt JD, Aragon AA, Baca OG. Lysosomal response of a murine macrophage-like cell line persistently infected with Coxiella burnetii. Infect. Immun. 1983;40:1155–1162. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.3.1155-1162.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen SY, Vodkin M, Thompson HA, Williams JC. Isolated Coxiella burnetii synthesizes DNA during acid activation in the absence of host cells. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1990;136:89–96. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-1-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Burton PR, Stueckemann J, Welsh RM, Paretsky D. Some ultrastructural effects of persistent infections by the rickettsia Coxiella burnetii in mouse L cells and green monkey kidney (Vero) cells. Infect. Immun. 1978;21:556–566. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.2.556-566.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hackstadt T, Williams JC. Biochemical stratagem for obligate parasitism of eukaryotic cells by Coxiella burnetii. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:3240–3244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heinzen RA, Hackstadt T, Samuel JE. Developmental biology of Coxiella burnetii. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:149–154. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(99)01475-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heinzen RA, Scidmore MA, Rockey DD, Hackstadt T. Differential interaction with endocytic and exocytic pathways distinguish parasitophorous vacuoles of Coxiella burnetii and Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:796–809. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.796-809.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zamboni DS, McGrath S, Rabinovitch M, Roy CR. Coxiella burnetii express type IV secretion system proteins that function similarly to components of the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:965–976. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Papini E, Zoratti M, Cover TL. In search of the Helicobacter pylori VacA mechanism of action. Toxicon. 2001;39:1757–1767. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(01)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Molinari M, et al. Vacuoles induced by Helicobacter pylori toxin contain both late endosomal and lysosomal markers. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25339–25344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Catrenich CE, Chestnut MH. Character and origin of vacuoles induced in mammalian cells by the cytotoxin of Helicobacter pylori. J. Med. Microbiol. 1992;37:389–395. doi: 10.1099/00222615-37-6-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leib DA, Machalek MA, Williams BR, Silverman RH, Virgin HW. Specific phenotypic restoration of an attenuated virus by knockout of a host resistance gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6097–6101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100415697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Williams, B. R. Signal integration via PKR. Sci. STKE 2001 <http://stke.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/OC_sigtrans;2001/89/re2> (2001). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Talloczy Z, et al. Regulation of starvation- and virus-induced autophagy by the eIF2α kinase signaling pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:190–195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012485299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dales S, Eggers HJ, Tamm I, Palade GE. Electron microscopic study of the formation of poliovirus. Virology. 1965;26:379–389. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(65)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bienz K, Egger D, Pfjister T, Troxler M. Structural and functional characterization of the poliovirus replication complex. J. Virol. 1992;66:2740–2747. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2740-2747.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bolton R, et al. Intracellular localization of poliovirus plus- and minus-strand RNA visualized by strand-specific fluorescent in situ hybridization. J. Virol. 1998;72:8578–8585. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8578-8585.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dubuisson J, Penin R, Moradpour D. Interactions of hepatitis C virus proteins with host cell membranes and lipids. Trends Cell. Biol. 2002;12:517–523. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(02)02383-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miller DJ, Schwartz MD, Dye BT, Ahlquist P. Engineered retargeting of viral RNA replication complexes to an alternative intracellular membrane. J. Virol. 2003;77:12193–12202. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.22.12193-12202.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Suhy DA, Giddings THJr, Kirkegaard K. Remodeling the endoplasmic reticulum by poliovirus infection and by individual viral proteins: an autophagy-like origin for virus-induced vesicles. J. Virol. 2000;74:8953–8965. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.19.8953-8965.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schlegel A, Giddings TH, Ladinsky MS, Kirkegaard K. Cellular origin and ultrastructure of membranes induced during poliovirus infection. J. Virol. 1996;70:6576–6588. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6576-6588.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bravo A, Salas M. Polymerization of bacteriophage F29 replication protein p1 into protofilament sheets. EMBO J. 1998;17:6096–6105. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.20.6096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Serrano-Heras G, Salas M, Bravo A. In vivo assembly of phage F29 replication protein p1 into membrane-associated multimeric structures. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:40771–40777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lyle JM, Bullitt E, Bienz K, Kirkegaard K. Visualization and functional analysis of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase lattices. Science. 2002;296:2218–2222. doi: 10.1126/science.1070585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rust RC, et al. Cellular COPII proteins are involved in production of the vesicles that form the poliovirus replication complex. J. Virol. 2001;75:9808–9818. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9808-9818.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hamasaki M, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. The early secretory pathway contributes to autophagy in yeast. Cell Struct. Funct. 2003;28:49–54. doi: 10.1247/csf.28.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ishihara N, et al. Autophagosome requires specific early Sec proteins for its formation and NSF/SNARE for vacuolar fusion. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:3690–3702. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dubois-Dalcq M, Holmes KV, Rentier B. Assembly of Enveloped RNA Viruses. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gosert R, Kanjanahaluethai A, Egger D, Bienz K, Baker SC. RNA replication of mouse hepatitis virus takes place at double-membrane vesicles. J. Virol. 2002;76:3697–3708. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.3697-3708.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pederson KW, van der Meer Y, Roos N, Snijder EJ. Open reading frame 1a-encoded subunits of the arterivirus replicase induce endoplasmic reticulum-derived double-membrane vesicles which carry the viral replication complex. J. Virol. 1999;73:2016–2026. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2016-2026.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Goldsmith CS, et al. Ultrastructural characterization of SARS coronavirus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004;10:320–326. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shi ST, et al. Colocalization and membrane assocation of murine hepatitis virus gene 1 products and de novo-synthesized viral RNA in infected cells. J. Virol. 1999;73:5957–5969. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5957-5969.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.van der Meer Y, van Tol H, Locker JK, Snijder EJ. ORF1a-encoded replicase subunits are involved in the membrane association of the arterivirus replication complex. J. Virol. 1998;72:6689–6698. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6689-6698.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Prentice, E., Jerome, W. G., Yoshimori, T., Mizushima, N. & Denison, M. R. Coronavirus replication complex formation utilizes components of cellular autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2003 Dec 29 [Epub ahead of print]. Demonstrates the first use of mammalian-host genetics to investigate the role of a gene required for autophagy, APG5, in RNA-virus replication; in the absence of the gene, a 1000-fold decrease in the yield of extracellular virus was found.

- 99.van der Meer Y, et al. Localization of mouse hepatitis virus nonstructural proteins and RNA synthesis indicate a role for late endosomes in viral replication. J. Virol. 1999;73:7641–7657. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7641-7657.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Snijder EJ, van Tol H, Roos N, Pedersen KW. Non-structural proteins 2 and 3 interact to modify host cell membranes during the formation of the arterivirus replication complex. J. Gen. Virol. 2001;82:985–994. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-5-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]