Influenza is an infectious respiratory disease that, in humans, is caused by influenza A and influenza B viruses. Typically characterized by annual seasonal epidemics, sporadic pandemic outbreaks involve influenza A virus strains of zoonotic origin. The WHO estimates that annual epidemics of influenza result in ~1 billion infections, 3–5 million cases of severe illness and 300,000–500,000 deaths. The severity of pandemic influenza depends on multiple factors, including the virulence of the pandemic virus strain and the level of pre-existing immunity. The most severe influenza pandemic, in 1918, resulted in >40 million deaths worldwide. Influenza vaccines are formulated every year to match the circulating strains, as they evolve antigenically owing to antigenic drift. Nevertheless, vaccine efficacy is not optimal and is dramatically low in the case of an antigenic mismatch between the vaccine and the circulating virus strain. Antiviral agents that target the influenza virus enzyme neuraminidase have been developed for prophylaxis and therapy. However, the use of these antivirals is still limited. Emerging approaches to combat influenza include the development of universal influenza virus vaccines that provide protection against antigenically distant influenza viruses, but these vaccines need to be tested in clinical trials to ascertain their effectiveness.

Subject terms: Influenza virus, Vaccines, Respiratory tract diseases, Viral pathogenesis

Influenza is an infectious respiratory disease that, in humans, is caused by influenza A and influenza B viruses. This Primer discusses the biological features of influenza viruses, their effects on human and animal health and the mitigation strategies to reduce the burden of this disease.

Introduction

Influenza is an infectious respiratory disease; in humans, it is caused by influenza A (genus influenzavirus A) and influenza B (genus influenzavirus B) viruses (influenzavirus C and influenzavirus D genera are also known). Symptoms associated with influenza virus infection vary from a mild respiratory disease confined to the upper respiratory tract and characterized by fever, sore throat, runny nose, cough, headache, muscle pain and fatigue to severe and in some cases lethal pneumonia owing to influenza virus or to secondary bacterial infection of the lower respiratory tract. Influenza virus infection can also lead to a wide range of non-respiratory complications in some cases — affecting the heart, central nervous system and other organ systems1,2. Although characterized by annual seasonal epidemics, sporadic and unpredictable global pandemic outbreaks also occur that involve influenza A virus strains of zoonotic origin. Pandemic influenza occurs every 10–50 years and is characterized by the introduction of a new influenza A virus strain that is antigenically very different from previously circulating strains; the lack of pre-existing immunity in humans is often associated with the severity of the infection and an increase in mortality.

All influenza viruses are enveloped negative-sense single-strand RNA viruses with a segmented genome. Influenza A and influenza B viruses contain eight RNA segments, which encode RNA polymerase subunits, viral glycoproteins (namely, haemagglutinin (HA), with its distinct globular ‘head’ and ‘stalk’ structures, which facilitate viral entry, and neuraminidase (NA), which facilitates viral release), viral nucleoprotein (NP), matrix protein (M1) and membrane protein (M2), the nonstructural protein NS1 and nuclear export protein (NEP) (Fig. 1). The HA and NA viral proteins are the most antigenically variable, and in the case of influenza A virus, they are classified into antigenically diverse subtypes. These two viral glycoproteins are located at the surface of the virus particle and are the main targets for protective antibodies induced by influenza virus infection and vaccination. Each influenza virus isolate is named according to its type or genus, host and place of isolation, isolate number and year of isolation (Box 1). Influenza C and influenza D viruses have only seven RNA segments and do not seem to cause substantial disease in humans. However, influenza C virus infections can cause influenza-like illness and hospitalizations in some instances, especially in children3.

Fig. 1. Influenza A and influenza B.

The figure represents an influenza A virus particle or virion. Both influenza A and influenza B viruses are enveloped negative-sense RNA viruses with genomes comprising eight single-stranded RNA segments located inside the virus particle. Although antigenically different, the viral proteins encoded by the viral genome of influenza A and influenza B viruses have similar functions: the three largest RNA segments encode the three subunits of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (PB1, PB2 and PA) that are responsible for RNA synthesis and replication in infected cells; two RNA segments encode the viral glycoproteins haemagglutinin (HA, which has a ‘stalk’ domain and a ‘head’ domain), which mediates binding to sialic acid-containing receptors and viral entry, and neuraminidase (NA), which is responsible for releasing viruses bound to non-functional receptors and helping viral spread. The RNA genome is bound by the viral nucleoprotein (NP), which is encoded by RNA segment 5. RNA segments 6 and 8 encode more than one protein, namely, the matrix protein (M1) and membrane protein (M2) — BM2 in the case of influenza B — and the nonstructural protein NS1 (not shown) and nuclear export protein (NEP). The M1 protein is thought to provide a scaffold that helps the structure of the virion and that, together with NEP, regulates the trafficking of the viral RNA segments in the cell; the M2 protein is a proton ion channel that is required for viral entry and exit and that, together with the HA and NA glycoproteins, is located on the surface of the virus anchored in a lipid membrane derived from the infected cell. Finally, the NS1 protein is a virulence factor that inhibits host antiviral responses in infected cells. The influenza viruses can also express additional accessory viral proteins in infected cells, such as PB1–F2 and PA-x (influenza A), that participate in preventing host innate antiviral responses together with the NS1 protein or NB (influenza B), the function of which is unknown. NS1, NEP, PB1–F2 and PA-x are not present in the virus particle or are present in only very small amounts. NB is a unique influenza B virus surface protein anchored in the lipid membrane of the virus particles.

The segmented nature of the influenza viral genome enables reassortment, that is, interchange, of genomic RNA segments when two viruses of the same type (that is, two influenza A viruses or two influenza B viruses) infect the same cell. A unique characteristic of influenza A viruses is that they circulate not only in humans but also in domestic animals, pigs, horses and poultry and in wild migratory birds (>100 species of ducks, geese, swans, gulls, waders and wild aquatic birds are considered natural reservoirs4,5). A total of 16 antigenically different HA and 9 antigenically different NA serotypes or subtypes (18 HA and 11 NA, if including bat influenza A-like viruses, which are phylogenetically close to influenza A virus but unable to reassort with influenza A viruses6,7) have been identified among the different avian strains of influenza A virus8. These animal reservoirs provide a source of antigenically diverse HA and NA genes that can be exchanged between viral strains by reassortment after co-infection of the same host, increasing virus diversity and in some instances leading to the generation of human pandemic influenza virus strains with HA and/or NA derived from animal strains. The HA subtypes can be grouped into two groups on the basis of the phylogeny of the HA molecule. Within each group, the domain encoding the HA stalk is antigenically similar. By contrast, influenza B and influenza C viruses are not divided into different subtypes and are restricted to humans, with no known animal reservoirs, although limited spillover to seals and pigs has occurred, respectively9,10. However, influenza B viruses have recently diverged into two antigenically different lineages (B/Victoria/2/1987-like and B/Yamagata/16/1988-like) that are currently co-circulating in humans, which prompted the inclusion of these two lineages, in addition to the influenza A H1N1 and H3N2 viruses, in many of the seasonal human influenza vaccines. Influenza C viruses are usually associated with very mild or asymptomatic infections in humans. In addition, influenza D virus is distantly related to influenza C virus, and it has been isolated from pigs and cows11,12.

In 2009, the first influenza virus pandemic of this century was caused by a novel H1N1 influenza A virus reassortant that was previously circulating in pigs13,14. Vaccines were not available on time to contain the first waves of infection. Current influenza antiviral adamantane drugs that target the viral M2 ion channel and inhibitors of NA enzymes have limitations, as viral resistance against M2 inhibitors is prevalent in the currently circulating human influenza A H1N1 and H3N2 strains; viruses resistant to the NA inhibitor oseltamivir have been prevalent among influenza A H1N1 strains since just before the 2009 pandemic15. Intriguingly, the adamantane-resistant, oseltamivir-sensitive 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 viruses replaced the previously circulating oseltamivir-resistant, adamantane-sensitive seasonal influenza A H1N1 virus that circulated globally in 2008–2009. Although detection of the currently circulating influenza A H1N1 viruses harbouring the NA-H275Y mutation, which imparts oseltamivir resistance, has been noted, emergence of resistance to NA inhibitors is not a major public health problem today16. Current seasonal influenza vaccines have only suboptimal effectiveness across all age groups, particularly in elderly individuals (a high-risk group for severe influenza virus infection). Thus, there is a major need to better understand the biology of influenza virus infections to develop new and more-effective antiviral agents and vaccines.

In this Primer, we discuss the biological features of influenza viruses and their effects on human and animal health, as well as the mitigation strategies to reduce the burden of influenza. We focus more on influenza A viruses because of their unique pandemic potential compared with other influenza viruses.

Box 1 Influenza virus nomenclature.

Each influenza virus isolate receives a unique name according to a set of rules. First, the name denotes the type of influenza virus (A, B, C or D), followed by the host species from which the virus was isolated (if not specified, the isolate is considered human), the geographical location at which the virus was isolated, the isolate number and the year of isolation. In the case of influenza A viruses, the haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) subtype is also usually indicated after the viral isolate name. For example, influenza A/Turkey/Ontario/6118/1968 (H8N4) virus is an influenza A virus isolated from a turkey in Ontario in 1968, isolate number 6118; the virus isolate has an HA from the HA antigenic subtype 8 and an NA from the NA antigenic subtype 4.

Epidemiology

Influenza in humans

The major burden of disease in humans is caused by seasonal epidemics of influenza A and influenza B viruses, with most of the infections occurring in children, although most of the severe cases involve very young or elderly individuals. Seasonal influenza A H1N1 and H3N2 currently circulate in humans, but influenza A H2N2 viruses were the only human circulating influenza A viruses from 1957 to 1968. Before 1918, conclusive evidence of the circulating subtypes is not available. In addition to seasonal epidemics, the introduction of influenza A viruses from either avian or swine populations has led to four pandemics since 1918, with those viruses subsequently becoming seasonal epidemic strains in subsequent years (Fig. 2). During pandemics, influenza viruses spread very quickly from the point of origin to the rest of the world in several waves during the year (Fig. 2) owing to the lack of pre-existing immunity, which could also contribute to increased virulence. Studies on the transmission of seasonal influenza A virus in humans have proposed that populations in southeast Asia, eastern Asia and/or the tropics act as permanent sources for seeding seasonal epidemics17,18, whereas other studies indicate that multiple geographical regions might act as seed populations for virus migration19. However, a lack of sufficient sequence data from areas such as Africa, India and South America currently prevents a complete understanding, as viral sequences, which are not routinely obtained during diagnosis, are required to ascertain the relationships between viruses spreading in different areas of the world. Seasonal influenza virus outbreaks typically occur in the winter months, when low humidity and low temperatures favour transmission; two ‘influenza seasons’ occur per year: one in the Northern Hemisphere and one in the Southern Hemisphere. However, unlike temperate regions, seasonal influenza patterns are very diverse in tropical countries. Climate factors, including minimum temperature, hours of sunshine and maximum rainfall, seem to be the strongest predictors of influenza seasonality20. Seasonal influenza B viruses co-circulate in humans with influenza A viruses and follow the same patterns of transmission.

Fig. 2. Influenza pandemics.

In the past 100 years, four pandemics of human influenza have occurred, with the 1918 pandemic caused by an influenza A H1N1 virus being the most devastating, as it was associated with >40 million deaths236. Influenza A H2N2, H3N2 and H1N1 viruses caused the 1957, 1968 and 2009 pandemics, respectively. In 1977, influenza A H1N1 restarted circulation in humans without causing a pandemic, as the strain was similar to that which preceded the 1957 influenza A H2N2 pandemic. By contrast, the 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus was antigenically very different to the previous seasonal influenza A H1N1 viruses and replaced them as the circulating influenza A H1N1 strain. Examples of the spreading of human influenza A viruses in the world are shown for pandemic 1918 and 1957 viruses and for seasonal H3N2 viruses18. For pandemic virus outbreaks, the arrows indicate the first and second waves of transmission. For seasonal influenza A H3N2 spread, the arrows indicate the seeding hierarchy of seasonal influenza A (H3N2) viruses over a 5-year period, starting from a network of major cities in east and southeast Asia; the hierarchy within the city network is unknown. Seasonal influenza B viruses (not shown) are co-circulating in humans with influenza A viruses.

Incidence

In the United States and from 2010 to 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has estimated that influenza virus infection has resulted in between 9.2 million and 35.6 million illnesses and between 140,000 and 710,000 hospitalizations21. In a typical year, 3–5 million cases of severe illness are caused by seasonal influenza virus infection in the world. Children seem to be the main human transmitters of influenza viruses, as illustrated by studies showing that vaccination of children reduces the incidence of severe influenza virus infections in elderly individuals22. Incidence of influenza virus infections increases during pandemic years owing to the lack of pre-existing immunity against the new virus, but severity varies depending on the pandemic virus itself, with the 1918 influenza A H1N1 pandemic being the most severe of the past 100 years.

Zoonotic human infections with influenza A virus strains of swine and avian origins are rare, with specific strains, such as the avian H5N1 and H7N9 and the so-called swine H3N2 variant viruses, being the most prevalent but confined to a limited number of human cases in specific geographical areas, with only limited human-to-human transmission. Prior age-related immunological imprinting in specific age groups acquired by exposure to viruses of the same or related subtype is associated with reduced incidence of disease with novel subtype influenza viruses23.

Mortality

Influenza A and influenza B viruses cause epidemic seasonal infections, resulting in ~500,000 deaths annually worldwide24, with the most recently calculated estimates being 291,243–645,832 deaths per year during the 1999–2015 period25. Seasonal influenza virus-associated deaths in the United States range from 5,000 to 52,000 people per year, depending on the year26. Several comorbidities are known to increase the risk of lethal influenza virus infection. In addition, pregnancy and age are known risk factors, with very young (<1 year of age) and elderly (>65 years of age) individuals being the most vulnerable populations. Although mortality is low in children >2 years of age and young adults, a substantial number of deaths owing to influenza virus infection have been recorded in young individuals with no known predisposition factors. Approximately 100 children die each year from influenza in the United States; this number has been stable since 2010 (ref.27). Severe disease and/or mortality in patients with influenza virus infection are in general due to either virus-induced pneumonia or secondary bacterial superinfection. Primary viral pneumonia is characterized by high levels of viral replication in the lower respiratory tract accompanied by strong pro-inflammatory responses, also referred to as cytokine storm.

Risk factors

Young children who have not had multiple previous exposures to influenza viruses are fairly susceptible to infection and typically have higher fever and more-severe symptoms and shed larger number of virus particles for longer periods of time. Older adults, either because of immunosenescence, concurrent chronic illnesses or both, are also at risk of more-severe illness, hospitalization and infectious complications28. In addition to the extremes of age, other groups at risk of severe disease, hospitalization or death include those with chronic pulmonary or cardiac conditions, diabetes mellitus or immunocompromising conditions29,30. Possibly because of difficulty handling respiratory secretions, individuals with neuromuscular disorders are also recognized as being at increased risk31. Pregnancy has long been recognized as a risk factor for severe influenza disease, possibly because of the increased cardiopulmonary demands of pregnancy or the effects of pregnancy on the immune system; the risk increases by trimester and persists into the post-partum period32. During the 2009 pandemic with influenza A H1N1, morbid obesity with body mass index >35–40 kg per m2 was also recognized as an important risk factor33. Obesity is associated with excessive influenza virus replication, increased severity of secondary bacterial infections and reduced vaccination efficacy34. Finally, the role of host genetic factors in disease remains poorly studied, but polymorphisms and nonsense mutations in several host genes (such as IFITM3 and IRF7, which encode genes involved in the interferon pathway) have been shown to predispose to severe disease35–37.

Influenza in animals

Infection of waterfowl with low pathogenic avian influenza A (LPAI) viruses, called as such owing to their lack of lethality in poultry, produces little or no clinical symptoms38. However, upon transmission to poultry, LPAI can cause substantial disease symptoms; in addition, viruses with H5 and H7 subtypes can become highly pathogenic (that is, lethal) in poultry. Outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza A (HPAI) throughout Eurasia and northern Africa are the major influenza disease burden in animals, with >400 million birds killed and economic losses totalling US$20 billion in the first 10 years of the 21st century39. Outbreaks of HPAI in poultry have also caused considerable problems in the United States, with the HPAI H5Nx (where x = 1–9) viruses, derived by reassortment of the Asian HPAI H5N1 viruses, being a recent example40. Recently, LPAI H7N9 viruses circulating in China have become HPAI through the acquisition of a multibasic cleavage site in their HAs and have also caused some self-limiting infections in humans41. Influenza A viruses can also cause mild to severe respiratory infection in a variety of mammals, including swine, horses and dogs; additionally, an outbreak of an influenza A virus of avian origin was detected in cats in New York, as first reported in December 2016. From its first report until February 2017, the influenza A H7N2 feline influenza A virus infected ~500 shelter cats and a veterinarian who treated one of the infected cats42.

Mechanisms/pathophysiology

Human influenza viruses are transmitted through the respiratory route, whereas avian influenza viruses in wild birds are transmitted through the faecal–faecal, faecal–oral or faecal–respiratory routes. Depending on the route of transmission, the virus targets epithelial cells of the respiratory or intestinal tract for infection and productive replication. In addition, some avian influenza A viruses, especially those of the H7 subtype, have been associated with human infections of the eye and conjunctivitis (inflammation of the conjunctiva)43. Severity of infection in humans is associated with replication of the virus in the lower respiratory tract, which is accompanied by severe inflammation owing to immune cell infiltration.

Transmission in animals

The main reservoir of diverse strains and subtypes of influenza A virus is wild birds, especially migratory ducks and geese. Indeed, domestic ducks raised on open ponds are the logical intermediaries between the reservoirs of influenza viruses in wild aquatic birds and other domestic poultry (Fig. 3). Transmission between birds can occur directly from contaminated water. Although most of the 16 HA and 9 NA influenza A subtypes cause asymptomatic infections in avian species, H5Nx and H7Nx subtypes can evolve into HPAI strains through the acquisition of a novel cleavage site in HA (which enables HA maturation by ubiquitous host proteases and spread of the virus outside the respiratory and intestinal epithelia to multiple organs, including the brain) and can cause lethal infections in chicken, turkey and some breeds of domestic duck44,45. Transmission of influenza viruses to multiple domestic poultry species occurs through so-called backyard farming, whereby species are raised together and in live poultry markets; subsequent transmission to commercial avian farms can occur through the lack of biosecurity (that is, procedures or measures designed to isolate and protect animals and humans from contact with infectious viruses) and because of viral spread through live markets46 (Box 2).

Fig. 3. Emergence of influenza A virus from aquatic wild bird reservoirs.

Influenza A viruses have been found in multiple species all seemingly derived from viral ancestors in wild birds, with the possible exception of bat influenza-like virus, which is of still uncertain origin. Influenza viruses from wild birds can spill over through water or fomites to marine mammals and to domestic free-range ducks. Transmissions to other avian species (for example, poultry) from domestic ducks or directly from wild birds can also occur from contaminated water. Transmission from ducks to other species occurs through ‘backyard’ farming, whereby the animals are raised together, and in live poultry and/or animal markets. Transmission from backyard to commercial farms can occur via lack of biosecurity and via spread through live markets46. Humans can be infected with poultry and swine influenza viruses through aerosols, fomites or contaminated water. However, in most instances these infections do not result in subsequent human-to-human transmission. Human-to-human transmission of seasonal or pandemic human viruses can be mediated by respiratory droplets, aerosols or self-inoculation after touching of fomites. Additional virus adaptations would be required for sustainable human-to-human transmission of animal influenza viruses. Other domestic animals known to be susceptible to influenza virus infections are dogs and cats. Dashed lines represent transmission that bypasses a domestic duck intermediate.

Influenza in pigs is a respiratory disease akin to influenza in humans, with high fever and pneumonia caused by influenza A H1N1, H3N2 and H1N2 subtypes47. Some strains of influenza A virus have been known to be transmitted by aerosol spread from humans to pigs and vice versa, including the pandemic 2009 influenza A H1N1 strain48 and the influenza A H3N2 variant that transmits from pigs to children49. In horses, infection causes respiratory disease and is spread by aerosol; two lineages of influenza A H3N8 are primarily responsible. In 2004, the equine influenza A H3N8 strain spread to dogs42,50. In 2006 in Asia, an avian H3N2 influenza A virus was also detected as being transmitted to dogs51.

Box 2 Avian (poultry) influenza.

The influenza viruses causing disease outbreaks in domestic poultry are the highly pathogenic avian influenza A (HPAI) H5Nx and H7Nx (where x = 1–9) and the low pathogenicity avian influenza A (LPAI) H6N1, H7N9 and H9N2 strains228. The major global problem for farmers of gallinaceous poultry (for example, chicken, quail and turkey) is the emergence of H5 and H7 HPAI viruses from LPAI precursors that must be reported to the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and can result in trade embargoes. In poultry, the HPAI strains are transmitted both by aerosol and faecal contamination and cause systemic haemorrhagic disease and death229. Between 2003 and 2017, the HPAI H5N1 strain infected 860 humans and caused 545 deaths230. The LPAI H7N9 strain that emerged in China in 2013 causes asymptomatic infections of quail and chicken231, but from 2013 to 2017, a total of 1,564 laboratory-confirmed human infections with this virus were reported in China232. To complicate matters, some LPAI H7N9 viruses have recently become HPAI233. But perhaps the most insidious influenza virus in domestic poultry on the basis of its prevalence and ability to reassort is H9N2, which emerged in Asia in the early 1990s; this virus causes asymptomatic infection in poultry, was the donor of six internal RNA segments to both HPAI H5N1 and LPAI H7N9 and was occasionally transferred to pigs and humans234,235.

Cell entry and viral replication

At the cellular level, influenza virus replication (Fig. 4) mainly takes place in epithelial cells of the respiratory tract in humans and other mammals and in epithelial cells of the intestinal tract in birds. The cellular cycle of the virus starts with binding to the target cell. This binding is mediated by the viral HA (which binds to sialic acids present in the oligosaccharides of the glycoproteins at the cellular surface) and is also responsible for the haemagglutination caused by virus particles when incubated with red blood cells. HAs from human influenza viruses bind preferentially to sialic acids linked by an α2,6 linkage to the rest of the oligosaccharide, whereas those from most of the avian influenza viruses favour binding to α2,3-linked sialic acids, as these bonds are the most abundant sialic linkages in the epithelial cells of the human upper respiratory tract and of the avian intestinal tract, respectively52,53. After binding, the virus is internalized in an endosome, and the endosome is trafficked and acidified, which triggers a conformational change in the viral HA that induces the fusion of the viral envelope with that of the endosome. As the endosomal pH varies between host species, the pH stability of HA is one of the determinants of viral tropism.

Fig. 4. Influenza virus life cycle.

Influenza virus enters the cell by endosomal uptake and release, and its negative-sense genetic material in the form of viral ribonucleoproteins (vRNPs) is imported to the nucleus for transcription of mRNA and replication through a positive-sense complementary ribonucleoprotein (cRNP) intermediate. Viral mRNA is translated into viral proteins in the cytoplasm, and these are assembled into new virions together with the newly synthesized vRNPs. PB1–F2 is shown here as a dimer, but can also be multimeric. HA, haemagglutinin; M1, matrix protein; M2, membrane protein; NA, neuraminidase; NEP, nuclear export protein; NP, nucleoprotein; NS1, nonstructural protein; PB1, PB2 and PA, viral RNA polymerases.

Fusion results in the release of virus contents, namely, its genetic material in the form of eight viral ribonucleoproteins (vRNPs), into the cytoplasm. vRNPs are subsequently imported into the nucleus of the infected cells, where transcription and replication of the viral RNA takes place through the enzymatic activities of the viral polymerase complex attached to the vRNPs. Viral RNA replication occurs through a positive-sense intermediate, known as the complementary ribonucleoprotein (cRNP) complex. Viral RNA transcription results in positive-strand mRNAs that are capped and polyadenylated and exported into the cytoplasm for translation into viral proteins. Newly synthesized viral polymerases (PB1, PB2 and PA) and viral NP are imported to the nucleus to further increase the rate of viral RNA synthesis, whereas virus membrane proteins HA, NA and M2 traffic to and get inserted into the plasma membrane. Newly synthesized HA needs to be cleaved into HA1 and HA2 polypeptides by cellular proteases to be functional. The cleavage site of HA is responsible for the tissue tropism of the virus, with all influenza viruses having a cleavage site recognized by extracellular proteases present in respiratory and intestinal epithelial cells, except for the HPAI viruses, which contain a multibasic cleavage site in HA that is recognized by ubiquitous proteases. Viral nonstructural proteins NS1, PB1–F2 (which can be dimeric or multimeric) and PA-x regulate cellular processes to disarm host antiviral responses. Viral M1 and NEP localize to the nucleus at late stages of viral infection, bind to vRNPs and mediate their export to the cytoplasm, where, through interactions with the recycling endosome, they migrate to the plasma membrane and are bundled into the eight vRNPs. Budding of new virions takes place, resulting in the incorporation of the vRNPs into new virus particles with a membrane derived from the host plasma membrane and containing the viral transmembrane proteins. NA activity prevents non-productive binding of HA of new virions to receptors bearing sialic acid present in the viral glycoproteins and in the membrane of the infected cells, facilitating viral spread. Viral replication results in cell death with pathological implications. In addition, viral products induce a pro-inflammatory response that is responsible for the recruitment of innate and adaptive immune cells, which clear and eliminate the virus, but that in excess induces immunopathology and pneumonia.

Antigenic drift

Influenza viruses are capable of evading the antibody-mediated immunity induced during previous infections or vaccinations by gradually accumulating mutations in HA and NA5 (Fig. 5). This process, known as antigenic drift, necessitates frequent updates of influenza vaccines to ensure sufficient antigenic relatedness between the vaccine and emerging virus variants. Because HA is currently the main component of the inactivated influenza vaccines, human and animal influenza virus surveillance programmes are in place to monitor antigenic changes of the virus, primarily using the haemagglutination inhibition assay (a surrogate assay to measure the inhibition of the interaction between HA and host cell receptors) and viral RNA sequence analyses54,55. Increased attention to antigenic drift of NA, measured using neuraminidase inhibition assays, could further increase the antigenic match between vaccines and circulating viruses56–58. In addition, antigenic drift of T cell epitopes has been observed but not as frequently as antibody-mediated drift59. Computational methods, so-called antigenic cartography, enable quantitative analyses and visualizations of haemagglutination inhibition assay data and neuraminidase inhibition assay data60.

Fig. 5. Influenza antigenic shift and antigenic drift.

In 1968, co-infections between an avian influenza A H3Nx (where x = 1–9) virus and the seasonal human influenza A H2N2 viruses resulted in the exchange of viral segments (reassortment) and the selection of the pandemic human influenza A H3N2 virus, with the RNA polymerase PB1 and haemagglutinin (HA) RNA segments derived from the avian virus and the rest of the segments derived from the human virus. The lack of pre-existing immunity to the antigenically novel H3 HA in humans facilitated human transmission. Similar reassortment processes have taken place during other influenza A virus pandemics. Once H3N2 became established in humans, the virus began to drift, as is the case with all other human seasonal influenza viruses. During drift, small antigenic changes in the HA protein generated by mutation are selected to increase immune evasion, although not as dramatically as during shift. M, RNA encoding M1, matrix protein, and M2, membrane protein; NA, RNA encoding neuraminidase; NP, RNA encoding nucleoprotein; NS1, RNA encoding nonstructural protein; PB2 and PA, RNA encoding RNA polymerases.

These methods to quantify antigenic drift of influenza virus strains, along with site-directed mutagenesis studies, have revealed that substantial antigenic drift can be caused by one or very few amino acid substitutions adjacent to the functional sites in the head (but not the stalk) of the HA protein61–63. The antigenic evolution of influenza viruses was shown to be more rapid in human influenza viruses than in swine and equine viruses, which is presumably related to the size, mixing and age-structure (that is, humans have a longer lifespan than swine and horses) of the host populations60,63,64. In wild birds, in which numerous avian influenza A virus HA and NA subtypes are circulating, within-subtype antigenic variation seems to be limited. However, upon introduction in poultry, antigenic variation within avian virus subtypes — perhaps related to a selective antibody pressure imposed by vaccine use — has been noted62.

Antigenic shift

In contrast to antigenic drift, antigenic shift refers to drastic changes in the antigenicity of the HA of circulating influenza A viruses; antigenic shift is associated with influenza A pandemics. The HA — and sometimes the NA — molecules of pandemic viruses are derived from antigenically diverse animal strains of influenza virus, which can be acquired by human influenza strains through reassortment (Fig. 5). Pandemic outbreaks are usually associated with the extinction of the previous circulating strains. However, in 1977, influenza A H1N1 viruses, not seen in humans since the 1957 influenza A H2N2 pandemic, started to co-circulate with influenza A H3N2 viruses65. The 2009 influenza A H1N1 pandemic was caused by an influenza A H1N1 virus that was antigenically very different from the seasonal influenza A H1N1 virus circulating at the time and resulted in the extinction of the previous influenza A H1N1 human lineage, but it did not result in the extinction of the influenza A H3N2 viruses. Since 2009, influenza A H3N2 and influenza A H1N1 viruses derived from the 2009 pandemic virus and two lineages of influenza B virus are co-circulating in humans.

The limited number of pandemic events that have happened makes it very difficult to predict the next pandemic. Human influenza A virus infections with antigenically diverse avian H5N1, avian H7N9, swine H3N2 and other animal influenza viruses are constantly detected in geographical regions where these strains are prevalent owing to the contact of infected poultry or swine with humans. However, no cases of sustained human-to-human transmission have been associated with these viruses, indicating that further adaptations need to take place for these viruses to become transmissible in humans. How feasible it is for these viruses to become adapted to human transmission and retain virulence is unclear. Only a few changes are needed for influenza A H5N1 viruses to become transmissible in ferrets, a host that is often used as an animal model of human influenza virus infection66–68.

Adaptations to new hosts

Aquatic waterfowl (for example, orders Anseriformes and Charadriiformes) host influenza A viruses of all the HA (H1–H16) and NA (N1–N9) subtypes and are believed to be the natural reservoirs of influenza viruses69. Some viruses, presumably from waterfowl, have adapted to other birds (Galliformes, such as chicken, quail and turkeys) and mammals (such as humans, swine, equine, dogs, mink and marine mammals)70. Such inter-species transmission and adaptation often involve viral genetic adaptations to the new host and can be attributed to viral RNA polymerases, which are error prone and have higher mutations rates than cellular DNA polymerases. The ensuing intra-host viral genetic diversity (sometimes referred to as viral quasi-species) results in a ‘swarm’ of viral mutants that facilitate adaptation to new selection pressures. Multiple genetic variants are transmitted between animals, and low-fitness variants can be maintained during transmission, presumably helped by the fitter variants within a host71. Maintenance of such genetic diversity in the virus population within one host would be potentially advantageous in adaptation following inter-species transmission events. In addition, the segmented RNA genome of the influenza virus enables viral genetic reassortment, providing an additional mechanism for genetic adaptation.

Adaptation to transmission in new hosts is usually multifactorial and could involve amino acid substitutions in the viral HA to optimize receptor binding72, to optimize HA and NA balance between their receptor binding and their receptor destroying activities, respectively73, and to enable HA to become activated at different pH values74. Additionally, changes in the viral RNA polymerase protein subunits can affect its activity in different hosts and affect the temperature sensitivity of the virus75,76 (the temperature of the human upper respiratory tract is ~33 °C, which is lower than that of birds and swine); changes in NP can affect susceptibility to the host antiviral protein interferon-induced GTP-binding protein Mx1 (ref.77), and changes in M1 and M2 proteins could alter viral morphology and facilitate respiratory transmission in new hosts78. Such functional changes that affect transmission could also be acquired through viral genetic reassortment, as occurred with the emergence of the human pandemics of 1957, 1968 and 2009 (ref.79).

Genetic adaptations can occur at the interface between wild aquatic birds and domestic ducks or geese, between aquatic and terrestrial poultry (as occurred with the emergence of avian influenza A viruses H5N1, H7N9 and H10N8) or within swine (as occurred with the emergence of the North American triple reassortant influenza A viruses and of the 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus). Of the influenza A H3N8 and H7N7 viruses endemic in equine for many decades, the H7N7 viruses seem to have become extinct, whereas the H3N8 viruses have persisted and have been transmitted to dogs in the United States50, increasing the host range of H3N8 viruses. In another example, avian influenza A H3N2 viruses have adapted to dogs in Asia51. Recently, species of bat from Guatemala and Peru have been found to carry influenza A-like viruses with new subtypes of HA and NA (namely, H17, H18, N10 and N11), and further influenza virus diversity can be detected in bats6,80. Although bat influenza A-like H17N10 and H18N11 viruses are unable to reassort with conventional influenza A viruses, they can replicate in mammalian species other than bats, raising the possibility that they could become adapted to other mammals81.

Innate immune responses

Host innate immunity represents a crucial barrier that viruses need to overcome to replicate and propagate in new hosts, and influenza viruses dedicate several viral proteins to overcome these responses. For example, the NS1 protein of the virus is an RNA-binding protein that prevents the activation of cytoplasmic viral RNA sensors, such as retinoic acid-inducible gene I protein (RIG-I; also known as DDX58)82. RIG-I recognizes the influenza viral RNAs on the basis of the presence of a terminal 5′-triphosphate moiety and an adjacent double-stranded RNA structure formed by the 5′ and 3′ ends of the viral RNAs that is required for viral RNA replication and transcription83. NS1 binds to the host factors E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase TRIM21 and E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RNF135 (also known as Riplet), which are required for RIG-I activation after viral RNA recognition, preventing a signalling cascade that otherwise leads to induction of interferon and interferon-inducible antiviral genes with antiviral activity, such as MX1, EIF2AK2 (more commonly known as PKR), OAS1, IFITM family members and IFIT family members, among others84. Moreover, influenza A virus NS1 can also prevent host mRNA synthesis, processing and trafficking events, inhibiting host responses to viral infection85–87. Interferon signalling events mediated by the Janus kinase (JAK)–signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway as well as the antiviral functions of several interferon-stimulated genes might also be targeted by NS1 to prevent the host antiviral response88–90.

In addition to NS1, several other influenza virus proteins can dampen the interferon-mediated antiviral response. PB1–F2, a viral nonstructural protein generated from an alternative open reading frame present in the PB1 RNA, suppresses the activation of mitochondrial antiviral-signalling protein (MAVS), an adaptor molecule located downstream of RIG-I and required for interferon induction91. PB2, a component of the viral polymerase, also seems to target MAVS activation92. PA-x, a recently discovered viral protein resulting from ribosomal frameshift of the viral RNA polymerase PA mRNA, suppresses host gene expression by virtue of its RNA endonuclease activity93. The multiple ways in which influenza virus counteracts the interferon-mediated antiviral response illustrate the importance of this host pathway.

Both type I interferons (namely, interferon-α (IFNα) and IFNβ) and type III interferons (namely, IFNλ) can inhibit viral replication in epithelial cells94. Tissue-resident macrophages and dendritic cells can also be infected by the virus, but viral production seems to be limited in these innate immune cells95. Nevertheless, exposure of these cells to viral infection results in their activation and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to the recruitment of additional innate cells, such as natural killer cells and pro-inflammatory monocytes, to the lungs, where they can control viral infection by killing infected cells. Although these host responses to infection are crucial for final viral clearance and induction of adaptive immune responses, an exacerbated response can lead to immunopathology and severe disease. For instance, high levels of neutrophil extracellular traps (chromatin-based structures released from neutrophils) can lead to lung damage and severe influenza virus infection96. Therapies aimed to reduce this so-called cytokine storm might be beneficial for patients with severe influenza97.

Adaptive immune responses

T cell immunity

Although mouse models are not considered optimal for analysing the pathogenesis of viral pneumonia, much of the research into how influenza virus-specific T cells work has used such systems. However, as the technology for monitoring T cell-mediated immunity in humans has improved, these basic insights have been validated98–102. In influenza virus infection, CD4+ T cell help is required for class-switching of antibodies and for optimal CD8+ T cell memory responses103,104. CD4+ T cell help is also required for peptide-based (and other) vaccines to promote optimal humoral and cellular immunity105,106. It is less clear whether CD4+ T cells are important effectors of direct influenza virus clearance that work via IFNγ production99,104, as occurs in infections with large DNA viruses such as herpesviruses.

With respect to CD8+ T cells, cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) effectors are required for optimal influenza virus clearance107,108. In their absence, antibody-mediated mechanisms might also work, though less rapidly. Prominent antigenic components are the NP, matrix protein M1 and the viral polymerases109. Of particular interest is the fact that infected cells display viral peptides 8–12 amino acids in length that bind major histocompatibility complex (MHC; encoded by the HLA genes) class I glycoproteins to form the antigenic complex (epitope) recognized by T cell receptors on influenza virus-specific CTLs. These peptides are generally derived from components inside the virus that are less subject to antibody-selected antigenic drift and, therefore, are more conserved across distinct influenza virus strains and subtypes. Strong evidence supports the idea that established CTL memory directed towards conserved viral peptides presented by widely prevalent human MHC glycoproteins (for example, that are encoded by HLA-A2) can provide a measure of protection against a novel influenza A virus that crosses over from an avian reservoir to humans101 (for example, the recent H7N9 cases101) (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the increased influenza virus susceptibility of some indigenous populations (in Australia and Alaska) correlates with the relatively low frequency of such ‘protective’ HLA types within these populations100.

Fig. 6. Rapid recovery from avian influenza A H7N9 virus infection is associated with early CD8+ T cell responses.

a | Patients who recovered early from severe influenza A H7N9 disease had rapid and prominent CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) recall responses. These early interferon-γ (IFNγ)-producing CTLs were most likely derived from pre-existing memory pools established after seasonal human influenza A virus infection, which then cross-reacted with H7N9. CTL responses were followed by antibody (Abs) responses 2–3 days later and by CD4+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cell responses101. b | By contrast, individuals who succumbed to severe influenza disease had minimal cellular or antibody immunity.

Given the unpredictability of influenza A virus pandemics and the inevitable lag phase in the production of vaccines (which are typically inactivated influenza virus vaccines), there is, of course, broad interest in possible strategies for cross-protective immunization. Live attenuated vaccines certainly have the potential to induce CD8+ T cell responses, but evidence to date suggests that they do not promote strong CTL memory110. Strategies aimed at maintaining large numbers of influenza virus-specific CTLs in the normal lung may both be impractical and have physiological consequences; instead, effector CTLs will likely need to be recalled from the recirculating ‘resting’ CTL memory pool. This approach can give more rapid virus clearance than is the case in a CTL-naive individual, resulting in milder disease outcomes.

Major questions are what constitutes optimal CTL memory, and how is this established. At a basic level, epigenetic profiles of the various CTL differentiation states (naive, effector and memory) are being defined to better understand the processes involved111. Also, as naive CTL sets are lost with age, priming influenza virus-specific CTLs early is important112. As for many other questions with CTLs, analysis of influenza virus infections will continue to inform the overall understanding of protective viral immunity.

B cell immunity

B cell responses are an integral part of the immune response to both influenza virus infection and influenza virus vaccines. Antibodies contribute substantially to the protection from infection, as shown by early experiments in which sera from an influenza virus-immune ferret could protect a naive ferret from influenza disease after challenge113. B cell responses mainly target viral HA and NA and, to a lesser degree, other viral proteins, including the NP and the matrix proteins114. Of note, discrete antigenic sites on the head domain of HA seem to be the preferential target of the antibody response115; these sites are immunodominant over most other B cell epitopes of the virus116,117. However, the molecular and immunological reasons for antigenic immunodominance remain obscure. Antibodies that target the head domain of HA are typically neutralizing (via blockade of receptor binding) and show inhibitory activity in the haemagglutination inhibition assay. Importantly, the haemagglutination inhibition titre correlates (imperfectly) with protection and is a surrogate marker for vaccine efficacy that is globally accepted by regulatory agencies118.

Antibody responses to influenza virus infection in naive humans are typically robust and long lasting. For example, antibodies raised to strains encountered in childhood can usually be detected at reasonable levels in elderly individuals and might protect from virus variants with similar antigenicity encountered later in life119–122. However, antigenic drift particularly affects the HA head domain, which has high plasticity123,124. Over the course of a lifetime, individuals might be exposed to or infected by influenza viruses several times. Interestingly, the first infection in life and its immune imprinting might skew antibody responses to subsequent exposures. This phenomenon was originally described as the original antigenic sin125, but different aspects of it have been called antigenic seniority, antigenic imprinting and back-boosting126. Typically, exposure to a new virus variant (or subtype) might also induce antibodies to viruses encountered earlier in life, depending on the relatedness of the two antigens. An antibody response against a novel virus variant in adults might, therefore, be heavily influenced by the individual’s exposure history117,127,128, which is an issue for vaccine development.

In addition to neutralizing strain-specific antibodies, viral infection can also induce low-level humoral immune responses against conserved epitopes of viral proteins126. Among these epitopes are the membrane proximal stalk domain of HA129,130, the extracellular domain of the M2 protein131 and conserved epitopes of NA132–135. The broad antibody responses against these epitopes might contribute to protection, and they often work through mechanisms that rely on crystallizable fragment (Fc)–Fc receptor (FcR) interactions (effector functions) or — in the case of anti-NA antibodies — NA inhibition136–138. However, the antibody responses induced by such conserved epitopes through infection or immunization (with current vaccines) are weak and reduce their potential contributions to protection in the general population.

As the mucosal surfaces of the respiratory tract are the main entry pathway for influenza viruses in humans, secreted antibodies play a major part in the prevention of infection. Key experiments in the guinea pig model of influenza have shown that only mucosal immune responses (including immunoglobulin A (IgA)) but not systemic immune responses can efficiently inhibit virus transmission139,140, which is important considering that influenza virus vaccines should prevent both disease in the host and transmission.

Diagnosis, prevention and screening

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of influenza is made mostly on the basis of clinical presentation and epidemiological likelihood of infection. Initially, nonspecific symptoms predominate, including fever, chills or frank shaking, headaches, myalgia (muscle pain), malaise (discomfort) and anorexia. The onset of these symptoms is sudden, and respiratory symptoms, particularly a dry cough, sore or dry throat (possibly with hoarseness) and nasal obstruction and discharge, are usually also present. Cough is the most frequent respiratory symptom and can be accompanied by substernal discomfort or burning. Presentation in older adults and in individuals with compromised immune systems can initially be less dramatic, possibly because of a diminished cytokine response, but initial mild symptoms can progress to severe lower respiratory disease in these patients. The presentation can include fever, lassitude (lack of energy) and confusion without the characteristic respiratory complaints, which may not occur at all. Presentation in children can include febrile seizures but other prominent systemic complaints may not be present.

During seasonal influenza epidemics, diagnosis on the basis of clinical presentation has reasonable accuracy in previously healthy young and middle-aged adults, in whom the presence of fever with either cough or sore throat is associated with influenza virus infection in ~80% of patients141. However, as these symptoms are similar to those caused by other respiratory pathogens, which include parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus, adenoviruses, rhinoviruses and coronaviruses, specific diagnostic tests are required to confirm infection by an influenza virus. Confirmation is important for reasons that include management of individual patients, public health responses and surveillance efforts142–144, but as patients do not always present to health-care facilities, the number of confirmed diagnoses is under-reported. The type of sample submitted for testing is usually a nasopharyngeal swab, a nasal wash or a combined throat and nasal swab; because the sensitivity correlates with viral load, samples obtained within 3 days of symptom onset are preferable.

As influenza-like illness can be caused by many viruses, the gold standard laboratory tests used for influenza are viral culture and reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) (Table 1). Virus culture is critical for detailed characterization of novel viruses, surveillance of sensitivity to antiviral drugs and monitoring of antigenic drift; it is time consuming, but the length of the test can be reduced if shell-vial co-cultures are used, which detect virus-positive cells by immunostaining before the presence of cytopathic effect145. By contrast, RT-PCR, which is a highly sensitive and specific molecular test, is quick, can be incorporated into multiplex assays and can be used to subtype viruses. The nucleic acid amplification tests are clearly superior to virus culture in both sensitivity and speed in the context of clinical management. For both viral culture and RT-PCR, the quality of the sample is important, as irregularities in handling can lead to degradation and false-negative results. The site sampled can also affect the sensitivity of the assay; nasopharyngeal swabs are preferred to throat swabs for detection of the virus during upper respiratory infection. As neither of these assays provides a point-of-care diagnosis, rapid antigen tests have been developed that are fast, can be run in a physician’s office and are less expensive, although low and variable sensitivity is a limitation. To overcome this limitation, a rapid molecular assay has been developed and approved by the US FDA, with results comparable to those of RT-PCR except in samples with low viral loads146. New point-of-care digital immunoassays also have superior sensitivity in detecting influenza A and influenza B virus infections compared with traditional rapid antigen tests147. Several recent point-of-care nucleic acid amplification tests with even higher sensitivities147 are now approved in United States. Future developments might include the use of transcriptomic approaches to diagnose both the cause and the severity of respiratory illnesses, for example, the presence of secondary bacterial infections and/or inflammatory markers148.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of influenza diagnostic tests

| Diagnostic assay | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virus culture | Virus detected by the appearance of cytopathic effect, HA assay or direct fluorescence antibody staining |

• High specificity ( >95%)237 • Enables characterization of novel viruses • Enables surveillance of antiviral sensitivity and antigenic drift |

• Slow ( >3 days) • Requires specialized skills and equipment • Lower sensitivity than RT-PCR |

| RT-PCR | Primers to conserved genes can be used in combination with those for HA |

• High specificity ( >99%)238 • High sensitivity ( >99%)238 • Can be multiplexed238 • Can be automated in relatively high throughput • Moderately fast (hours) • Can be used to simultaneously type and subtype viruses239 |

• Expensive • More prone to false positive results (by nucleic acid contamination) than virus culture238 |

| Rapid antigen test | Immunoassay detection of the presence of viral antigen in the sample |

• Fast (15 min) • Low cost • Point of care • Can detect both influenza A and influenza B |

• Low sensitivity (70–50%)240,241 • Prone to false negative results241 (96% negative predictive value) • Cannot provide subtype information |

| Rapid molecular assay | Based on isothermal nucleic acid amplification; requires simple heat source and fluorescence detection |

• Fast (15 min) • High specificity ( >99%)240 • Good sensitivity (66–100%)240 • Point of care |

Expensive |

HA, haemagglutinin; RT-PCR, reverse transcription PCR.

Vaccines

After the causative agent of influenza was identified to be a virus in the 1930s, attempts were made during World War II to develop inactivated virus as a vaccine, which culminated in the licensing of the first influenza virus vaccine for the civilian population in 1945 in the United States. Unfortunately, it soon became clear that the vaccine did not protect well against new influenza virus strains. Specifically, the 1947 seasonal epidemic strain had changed sufficiently that the vaccines made with earlier circulating strains had lost their effectiveness149. All currently available influenza virus vaccines are injected intramuscularly, with the exception of the live attenuated influenza virus vaccines, which are administered intranasally.

Design and manufacture

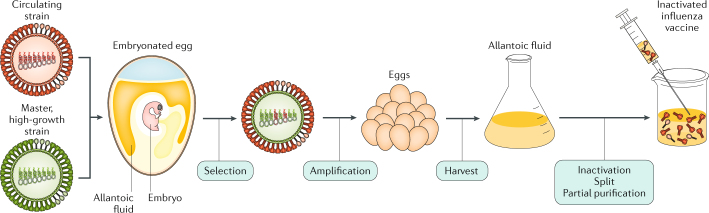

Although antigenic shift and antigenic drift in influenza viruses are recognized problems, the procedure to manufacture influenza virus vaccines has remained largely unchanged for many decades. The manufacture of influenza virus vaccines involves growing the virus in embryonated chicken eggs and inactivation using formalin (or another alkylating reagent). In the 1970s, two changes were introduced. First, reassortment of up to six internal RNA segments of the high-yielding influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 strain with RNA segments encoding HA and NA of the seasonal vaccine candidates improved the growth characteristics of the virus in embryonated eggs with obvious advantages for vaccine production (Fig. 7). Second, the whole virus is now subjected to treatment with ether or detergent to make subvirion (or split) preparations, which are much less reactogenic and are more tolerable for the patient (reviewed in ref.150).

Fig. 7. Inactivated influenza A virus vaccine manufacture.

An antigenically representative circulating strain is reassorted with the high-growth influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (PR8) virus strain by co-infection in eggs, and a vaccine virus is selected with the high-growth properties of PR8 (conferred by its RNA segments encoding internal viral proteins) and the haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) derived from the circulating strain. The vaccine virus is amplified in eggs, and the allantoic fluid from the infected eggs containing high titres of the virus is harvested; the virus is inactivated, treated for splitting of individual viral components and subjected to partial purification to enrich for the HA (and NA) viral components in the final injectable vaccine.

In 2003, MedImmune (Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA) introduced the first live attenuated influenza virus vaccine (LAIV) licensed in the United States. This vaccine is based on the backbones of the influenza A/Ann Arbor/6/1960 and influenza B/Ann Arbor/1/1966 strains, through the passaging of the viruses at low temperature (25 °C). Cold-adapted influenza virus vaccines based on the same principle and developed by the Institute of Experimental Medicine (IEM, Saint Petersburg, Russia) have been successfully used in Russia since 1987 (ref.151). Seasonal vaccines are made by reassortment of the six internal RNA segments of the cold-adapted strain with the HA and NA RNA segments of the influenza virus strains specified by the health authorities for inclusion in the seasonal vaccines. Vaccine strain selection for both inactivated vaccines and LAIVs is based on the determination of the prevalence of recent human circulating strains by multiple laboratories engaged in a WHO-sponsored influenza surveillance programme (Box 3). LAIVs seem to have advantages in inducing mucosal and more broadly protective immune responses in infants and children than inactivated influenza virus preparations (reviewed in ref.150). However, studies with LAIVs in the United States have shown poor efficacy against the influenza A H1N1 component152.

Tissue culture cell-based substrates other than embryonated eggs have the advantage of not becoming limiting in cases when vaccine production needs to increase, such as during pandemic outbreaks. Cell-grown influenza virus vaccines based on Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) and Vero cells (from kidney epithelial cells of monkeys) were licensed in Europe in 2007 and 2009, respectively. However, production of the Vero-cell vaccine has been stopped, as the company that developed them ceased its vaccine production portfolio, and the FDA only approved the first MDCK-grown influenza virus vaccine in 2012 (ref.153). This approval was a major accomplishment after exhaustive studies to demonstrate that the cells did not contain adventitious viruses that were due to known naturally occurring dog viruses, such as oncogenic papilloma and retroviruses.

Another breakthrough for influenza vaccines came in 2013, when the FDA licensed Flublok (Protein Sciences Corporation, Meriden, Connecticut, USA), which is a product made exclusively using recombinant DNA technologies. For the quadrivalent product, four different baculoviruses expressing the HA of two influenza A viruses and the HA of two influenza B viruses are used to infect continuous insect cell lines; the HA proteins are then extracted and purified from the infected cells — a process that completely avoids the use of influenza viruses and of embryonated eggs. Thus, there is now a faster start-up possible for vaccine manufacturing in cases of vaccine shortages or the emergence of novel pandemic strains. Also, there is no need for time-consuming adaptations of the vaccine strains to increase yields in embryonated eggs or in tissue culture, as the recombinant baculoviruses express different HAs at comparable levels in insect cells154.

Addition of adjuvants to inactivated influenza vaccines can improve vaccine efficacy and the breadth and duration of protection and can have dose-sparing benefits in case of years with vaccine shortages. Indeed, in November 2009, German regulatory authorities approved an MF59-adjuvanted, MDCK-grown influenza A H1N1 pandemic vaccine155. MF59 is a squalene-based adjuvant that increases the immunogenicity of protein-based vaccines, and MF59-adjuvanted inactivated influenza vaccines are now approved for use in people >65 years of age, in whom unadjuvanted inactivated influenza vaccines perform poorly. In 2013, the FDA approved an adjuvant influenza vaccine for the prevention of pandemic influenza A H5N1. This vaccine is for use in people >18 years of age who are at increased risk of infection with avian influenza A H5N1 viruses. The adjuvant used, AS03, similar to MF59, is a squalene-based oil-in-water emulsion that is combined with the H5N1 component before intramuscular injection. AS03-adjuvanted pandemic influenza virus vaccines have previously been used in Europe during the 2009 influenza A H1N1 pandemic, where they received close attention owing to several reported cases of vaccine-associated narcolepsy156, a chronic neurological disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness. Contributory roles of the pandemic virus or the vaccine antigens in these adverse events could not be excluded.

To increase the poor immunogenicity of inactivated influenza vaccines in elderly individuals, an unadjuvanted high-dose vaccine has also been developed and is proven to decrease severe influenza virus infection outcomes compared with standard-dose vaccines157. In addition, some available influenza vaccines are now tetravalent, incorporating both influenza B virus lineages. Thus, the variety of approved influenza virus vaccines has been dramatically increased in recent decades globally. However, all these available seasonal influenza virus vaccines still necessitate annual reformulations to match antigenically circulating vaccines (Box 3). In addition, the short duration of immunity is another major shortcoming of the current vaccines.

Reverse genetics technologies to generate recombinant influenza viruses with defined genetic sequences from plasmid DNA were introduced in 1990 (ref.158). These techniques should improve both live and inactivated influenza virus vaccine manufacturing by creating vaccine backbones with increased replication properties and stability for use in embryonated eggs or in tissue culture. Other approaches are aimed at inducing protective immune responses against the aforementioned conserved epitopes of various viral proteins. Novel and safe adjuvants based on Toll-like receptor-mediated immune stimulation and novel modes of delivery may dramatically change the vaccine field in the future. The ultimate goal of these approaches is to make an influenza virus vaccine that provides lifetime (or at least multi-year) protection, protects against all influenza antigenic variants and establishes a degree of herd immunity. Indeed, consensus is that influenza virus vaccines could and should be improved and that efforts to design a long-lasting universal influenza virus vaccine effective against different antigenic variants are worthwhile159,160.

Box 3 Seasonal influenza vaccine strain identification.

Year-round surveillance for human influenza is conducted by >100 designated national influenza centres around the world. The laboratories send isolated viruses for genetic and antigenic characterization to five WHO Collaborating Centres for Reference and Research on Influenza, which are located in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Japan and China. A WHO committee reviews the results of surveillance and laboratory studies twice per year and makes recommendations on the composition of the influenza vaccine on the basis of the use of antigenically matched viruses with those that are expected to be highly prevalent in the next season. Each country then makes their own decision about which viruses should be included in influenza vaccines licensed in their country.

Schedules and vaccination programmes

Vaccine recommendations vary from country to country, with some recommending vaccination in only the high-risk groups and contacts. Currently, the public health authorities in the United States and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend yearly vaccination with seasonal influenza virus vaccine to all people >6 months of age161. Stronger recommendations are given to individuals in high-risk groups for severe influenza and to caregivers and contacts of those at high risk. The WHO recommends seasonal influenza vaccination to pregnant women (highest priority) and, in no particular order of priority, to children 6 months to 5 years of age, elderly individuals (>65 years old), individuals with specific chronic medical conditions and health-care workers.

In the absence of a universal vaccine that covers all possible strains and subtypes of influenza virus, many countries have implemented stockpiling vaccine programmes to store vaccines against influenza virus strains with pandemic potential for emergency first responders to alleviate the problem imposed by the rapid spread of pandemic influenza. Although preparing for potential pandemic threats is sound public health policy, it is not compelling to assume that the influenza A H5N1 viruses (or the more recently detected H7N9 virus (March 2013)) are pandemic precursor strains because they are associated with the largest numbers of human infections among animal influenza A virus strains. First, over the past 130 years, only viruses expressing an H1, H2 or H3 HA have been responsible for seasonal or pandemic strains. Avian H5N1 and H7N9 viruses have most likely circulated for at least as long without spilling over into humans and starting a new pandemic162. Accordingly, these ‘avian’ HA influenza viruses are unlikely to easily transmit from person to person. Second, the high case fatality rates cited by the WHO for H5N1 and H7N9 viruses in humans seem to be an artefact of the way they were calculated (that is, counting only patients who were hospitalized as having been infected by these viruses); many more people seem to have been infected by these viruses without severe outcomes163,164. Additionally, severe disease only results from exposure to large quantities of the virus, which can occur when people are in direct contact with diseased poultry. However, transmission of seasonal or pandemic influenza viruses requires only small quantities of virus (estimates vary between 2–25 virions165 and 50–400 virions166) to cause severe disease and transmission.

Efficacy and effectiveness

Despite the availability of seasonal and pandemic influenza vaccines, debate is ongoing as to the efficacy (as measured by randomized controlled trials) and effectiveness (as measured by observational studies involving vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals) of these vaccines167. Although different methodologies, the variability of the virulence of different seasonal strains, the fit or matching of the vaccine with the circulating strains and age differences of different cohorts can make interpretation of results between studies difficult, most studies find a positive effect of vaccination on the overall health of vaccinated individuals168,169. Nevertheless, many challenges still remain, such as the documented lack of efficacy of LAIVs in the United States in the past years170, the possible reduced vaccine efficacy with repeated annual immunizations171 and the problems associated with vaccine mismatches172. Assays to monitor antigenicity with respect to prior viruses are performed on a regular basis, generally by government laboratories. Antigenicity of a virus is characterized by infecting naive ferrets with the cultured virus and collecting the sera 2–3 weeks later; the ability of the sera to inhibit haemagglutination compared against the current vaccine is monitored. Sera from an antigenically novel virus will show reduced haemagglutination inhibitory activity compared with previous virus strains, indicating antigenic drift and a potential vaccine mismatch.

Antivirals

Together with vaccines, antiviral drugs play a vital part in the prevention and treatment of influenza virus infection and disease. In a normal influenza season, antiviral drugs are primarily used for treating patients who are severely ill, particularly those who have a compromised immune system. In a pandemic setting, especially in the period before a vaccine is available, antiviral drugs are essential for both treating patients who have been infected and preventing infection in individuals who have been exposed. Two classes of drugs are currently approved for influenza, namely, the adamantanes and the NA inhibitors.

Amantadine and rimantadine are both orally administered drugs that target the M2 ion channel of influenza A viruses. However, these drugs are globally no longer recommended for clinical use because of widespread resistance among circulating influenza A viruses (see below). By contrast, NA inhibitors target the enzymatic activity of the viral NA protein. Oseltamivir is delivered orally as the prodrug oseltamivir phosphate, which is converted to its active carboxylate form in the liver; zanamivir is inhaled as a powder (limiting its use in those with underlying respiratory problems); and peramivir is administered intravenously, which is important for patients who have been hospitalized173. All three drugs have received approval in the United States, Europe, Canada, Australia, Japan, Taiwan and Korea and act by mimicking the binding of sialic acid in the active site of NA on influenza A and influenza B viruses174.

Oseltamivir and zanamivir are effective for prophylaxis and post-exposure prophylaxis in individuals175. However, the randomized controlled trials of these drugs were conducted in patients with uncomplicated influenza; accordingly, observational data must be used to assess effectiveness in patients who are severely ill and have been hospitalized, in whom the need is arguably greater. Despite this limitation, study results consistently report improved outcomes associated with NA inhibitor use, including reduced risk of pneumonia and hospitalization, and reduced risk of mortality in patients who have been hospitalized176–178. Another consistent finding is that better results are obtained with early administration of NA inhibitors (within 2 days of symptom onset), although later administration can still be beneficial in severe cases.

Resistance

The emergence of drug-resistant viruses is a major challenge for the antiviral field. Adamantane resistance (conferred by an S31N mutation in the RNA segment encoding M2) first emerged in influenza A H3N2 viruses in 2003 and became prevalent worldwide by 2008 (ref.179). The pandemic 2009 influenza A H1N1 virus, which is presently circulating as a seasonal H1N1 virus, is also resistant to the adamantanes, as its M RNA segment (Fig. 1) was inherited from a virus that carried the S31N mutation180. Thus, since 2009, only the NA inhibitors have been able to provide protection, with the currently circulating human influenza A and influenza B viruses being generally sensitive to oseltamivir and zanamivir (Table 2). However, emergence of oseltamivir resistance is of particular concern for influenza A H1N1 viruses because it has happened in the past; in 2007, resistant influenza A H1N1 viruses began to circulate and quickly became dominant by the 2008–2009 season181. The resistant phenotype is associated with an H275Y mutation in the RNA segment encoding NA, and studies have shown that, in the background of other permissive mutations, H275Y-mutant viruses do not display any fitness deficits, which explains their ability to circulate so readily182,183. Of note, these viruses remain sensitive to zanamivir. Perhaps fortuitously, the oseltamivir-resistant seasonal influenza A H1N1 virus was displaced by the introduction of the oseltamivir-sensitive pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus in 2009. Since then, surveillance efforts have monitored NA inhibitor sensitivity closely and, although oseltamivir-resistant isolates of the 2009 influenza A H1N1 virus have been detected, these are primarily (but not exclusively) from patients undergoing therapy184. Susceptibility to NA inhibitor is assessed by measuring NA enzyme inhibition in a functional assay using cultured virus. Alternatively, RT-PCR capable of detecting single nucleotide polymorphisms (or RT-PCR followed by sequencing) is used to detect known resistance mutations in NA185, but the functional assay may be required if novel mutations are present.

Table 2.

Antiviral resistance of circulating influenza viruses

| Influenza virus (strain) | Resistance (% of isolates tested) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adamantanes | Oseltamivir | Zanamivir | |

| Pre-2009 pandemic | |||

| Influenza A (seasonal H1N1) | 0.6 | 98.8a | 0 |

| Influenza A (H3N2) | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Influenza B | N/A | 0 | 0 |

| 2015–2016 season | |||

| Influenza A (2009 H1N1) | 100 | 0.8 | 0 |

| Influenza A (H3N2) | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Influenza B | N/A | 0 | 0 |

Data are from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance for the 2008–2009 and 2015–2016 seasons in the United States. N/A, not applicable. aMost seasonal influenza A H1N1 viruses were sensitive to oseltamivir until late 2007.

There is a higher prevalence of resistant virus in children and individuals who are immunocompromised, which is believed to be related to higher viral loads and prolonged virus shedding in these individuals186,187. Also, patients who have been hospitalized are more likely to be treated for longer periods, which will increase pressure on the virus and the likelihood that a resistant strain will emerge. Although this outcome may be predictable, oseltamivir resistance arose in 2007 seemingly in the absence of drug pressure; given the correct background of secondary mutations, the same outcome is a possibility for the current influenza A H1N1 virus188. Oseltamivir resistance among influenza A H3N2 viruses and influenza B viruses has also been reported, albeit at a much lower frequency than for influenza A H1N1 (ref.189).