Abstract

Background

Male breast cancer (MBC) is rare, and most previous studies limited their focus on clinical aspects of the disease. Psychosocial implications and care needs of MBC patients are poorly understood.

Objectives

The aim of this study is to explore the experiences of men living with breast cancer and to identify supportive care needs.

Methods

Eighteen men were interviewed using qualitative, semi-structured telephone interviews. Qualitative content analysis was used to analyze the data.

Results

The majority of men did not have negative feelings about having a “women's disease,” although some felt that stigmatization threatened their masculinity. Male sex was perceived as hindering access to adequate care. Patients identified key barriers including (1) a lack of awareness and experience of treating males among health professionals; (2) treatment and available information were based on evidence for females; and (3) lacking support services.

Conclusion

To improve MBC care, it is important to raise awareness of the disease and to adapt treatment strategies, patient information, and support services to meet the needs of men.

Keywords: Qualitative research, Male breast cancer, Psycho-oncology, Men's health

Introduction

Male breast cancer (MBC) is a rare condition that accounts for <1% of all breast cancer diagnoses in Germany. Its incidence rate has risen by almost 50% in the last 2 decades [1], and findings show that men are still diagnosed at later stages and have worse prognoses than women [2, 3]. Because of its rarity, MBC is almost unknown in both the general population and among healthcare professionals (HCP) [3, 4]. Men have received little attention in breast cancer research [5], and their treatment is largely based on available evidence for women [6, 7]. Researchers have therefore called for investigations to examine the appropriateness of female-based therapies for male patients [8].

Studies exploring MBC have generally used quantitative designs and focused on the disease's clinical aspects such as risk factors, pathology, and treatment. As patients face not only physical but also emotional challenges, it is not sufficient to take only a medical approach. However, little attention has been paid to a detailed understanding of the experiences, psychosocial implications, and supportive care needs of men with breast cancer [9, 10]. The small number of qualitative studies that have examined men's experiences and the psychosocial impact of living with breast cancer have shown that men experience the disease in many different ways. Researchers have found that low awareness among men is common and causes delays in diagnosis [4, 11, 12, 13]. Furthermore, studies consistently report on men's dissatisfaction with patient information provided by HCP as well as with leaflets on treatment and side effects, whereas their accounts of experiences surrounding stigma, role strain, and body image vary greatly [9, 12, 14, 15].

When it comes to coping with breast cancer, women often report that social support from family members and close friends is pivotal [16]. In contrast, it has been shown that male patients rely mostly on their wives' support [9, 12]. Support groups have been found to have positive effects on disease management and patient empowerment, and to improve health-related quality of life [17, 18]. The study by Coreil et al. [19] revealed that women viewed breast cancer support groups positively, with the benefits of attending such groups including, e.g., bonding with other members and sharing information. However, information on men's experiences with breast cancer support groups is scarce.

MBC is under-researched in Germany. We aimed to address this gap by investigating how men experience breast cancer, their supportive care needs, and their experiences of attending MBC support groups. Our results are expected to contribute to MBC care by helping clinicians treat men appropriately and fulfill their specific needs. Our findings may be of interest beyond Germany.

Methods

Participants

We recruited study participants from two settings: (1) a MBC patient support group and (2) a university hospital. We chose this recruitment strategy to gain greater insight into men's accounts of living with MBC by including participants from different settings. Patients attending support groups were expected to cope with the disease differently [20].

We contacted members of the support group and asked their chair for distribution of our study materials via the support group's mailing list. Potentially eligible patients from the hospital were selected when their electronic medical record contained written consent to be contacted for research purposes.

All eligible patients from both settings received an invitation to participate in a semi-structured interview and a data protection declaration. An expense allowance (EUR 30) was offered to participating patients. Patients were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) breast cancer diagnosis; (2) male sex; and (3) written consent to participate in the study.

Data Collection

Since this is an under-researched topic, a qualitative approach was chosen, and semi-structured interviews were used to investigate men's views [21]. Patients had the option to be interviewed either face-to-face or by telephone. All participants preferred to be interviewed by telephone. Telephone interviews have been reported to be appropriate and suitable for investigating sensitive issues, as the anonymity of the interviewer and participant encourages participants to express themselves more openly [22, 23].

The interview guideline used during the interviews was developed by T.S.N. and H.K. according to the “Manual for conducting qualitative research” by Helfferich [24] based on the existing body of literature described above. It consisted of an open introductory question: “Please tell me everything you feel is important with respect to your breast cancer.” Further questions depended on the patient narratives. If not already discussed exhaustively, the interviews concluded with questions on experiences, gender issues, coping strategies, and needs.

Data Analysis

Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim using “f4transkript” [25]. To ensure anonymity and confidentiality, patients' names were replaced by a code (P for “patient” and an individual number). Transcripts were not returned to participants for comments or corrections. One researcher (T.S.N.) initially coded interviews using MAXQDA 12 software [26] and developed a working analytical framework. T.S.N. and H.K. discussed and analyzed the codes using qualitative content analysis according to Mayring [27], resulting in overarching categories. T.S.N. is a female researcher (Health Scientist, MA, and a research assistant at the time of the interviews), and H.K. is a female Professor of Primary Care, MD, and researcher with longstanding experiences. She instructed T.S.N. carefully prior to data collection and analysis. M.B. is a female Gynecologist (PhD), and N.M. is a male Professor of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. Interviews and analyses were conducted in German, and a native speaker translated patients' quotes into English for publication.

This study adhered to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research [28].

Results

Eighteen patients agreed to participate in a telephone interview. Sociodemographic data are presented in Table 1. Patients were between 53 and 83 years old, with a mean age of 68.5 years. Average time since diagnosis was 4.5 years (range: 2–8). Thirteen patients were retired, mostly due to age, and 5 were still working. Interviews lasted 18–85 min (on average: 41).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n = 18)

| Study participants, n | |

| Support group | 10 |

| Hospital | 8 |

| Age, years | |

| Mean | 64 |

| Range | 53–83 |

| Relationship status, n | |

| Married | 14 |

| Single | 1 |

| Divorced | 1 |

| Widowed | 2 |

| Employment status, n | |

| Employed | 3 |

| Self-employed | 2 |

| Retired | 13 |

| Time since diagnosis, years | |

| Mean | 4.5 |

| Range | 2–8 |

| Interview duration, min | |

| Mean | 41 |

| Range | 18–85 |

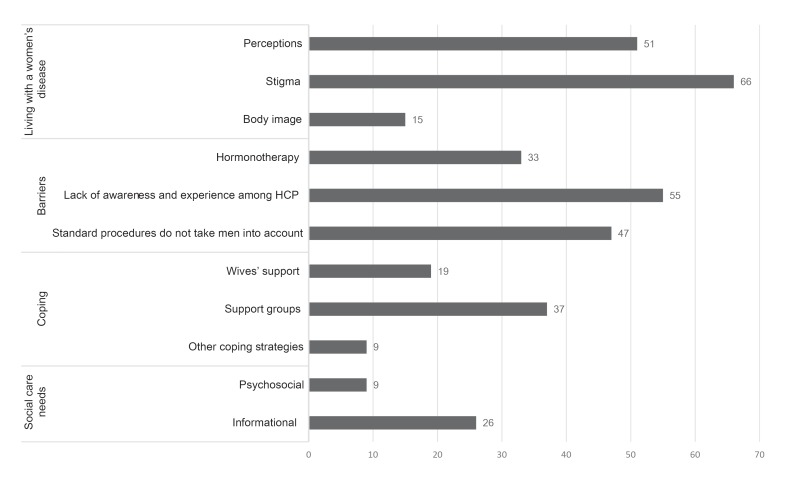

Figure 1 describes the categories raised by participants during the interviews, including the number of codes assigned to them in MAXQDA.

Fig. 1.

Categories and frequencies of issues raised in the interviews. HCP, Health Care Professionals.

Category 1: Living with a “Women's Disease”

Men reported a wide range of personal thoughts with regard to their diagnoses.

Perceptions

Patients had differing views on being diagnosed with a “women's disease.” Whereas some patients considered MBC rather exotic and a threat to their masculinity, others compared it to “any other disease” (P10) or even expressed positive feelings.

“My biggest problem was how to tell my wife that I have a woman's disease? Because I thought maybe you're not a real man, perhaps half woman?” (P7)

“I (am) actually happy that it was breast cancer as it makes me feel l have something special.” (P4)

Stigma

Men often addressed stigma by reporting on the way others reacted to their disease. They indicated that general perceptions of breast cancer as a women's disease prevented them from talking to others about it.

“When I spoke to people about it, they thought I was telling fairy tales … that was really the worst thing about it.” (P5)

“From others at work, I always (hear) ‘admit it, you're just trying to find excuses. You're not a real man, or you wouldn't have such an illness’.” (P7)

Some felt stigmatized when they were the only male patient, e.g., in hospitals or gynecological practices.

“There are only women in the hospital ward where you lie (…) I can tell you, they were not especially cooperative. I really felt like an outsider.” (P2)

Body Image

In general, the mastectomy scar was not a problem to patients, although some men admit they hid it at first. However, hair loss resulting from chemotherapy was a major concern to some. Men assumed they would have suffered more from their mastectomy if they had been female because it would have been “more life-changing” (P14).

“It's a different situation for women; in your mind it's then more about losing your femininity and who knows what else. But that's not the case for us, you see? I've only got one nipple left, right? That doesn't bother me” (P1)

Category 2: Barriers

Men identified key barriers and concerns with respect to MBC care. As treatment and procedures were developed with women in mind, they felt that male sex prevented them from receiving adequate care.

Hormonotherapy

Almost all patients received hormonotherapy, and generally Tamoxifen. Many men found this frustrating, as they doubted whether they should take the same medication as females. Men strongly expressed the wish to explore the effectiveness and side effects of hormonotherapy on men.

“The worst thing is everyone tells me the same thing: ‘Yes, but your treatment is in line with guidelines.’ I'm being treated as though I were a woman, right? I am definitely not a woman. (…) This is specifically about me.” (P3)

“I would have quite liked the anti-hormone therapy to include a medication that had been tested on men, so that I could be confident that it's suitable for me, as a man.” (P7)

Some patients reported side effects, e.g., hot flashes or sweating; 3 men considered themselves to be “menopausal women.” Furthermore, decreased libido was an issue:

“We're candid and honest with one another … male sexual potency has gone.” (P5)

Lack of Awareness and Experience among HCP

Men felt HCP knew little about their disease, both in terms of the diagnosis and treatment, and some of them wrongly referred to plastic surgeons. Men also reported a lack of sensitivity and that they were not taken seriously.

“Well it would be helpful if it was more widely known that men can get it. (…) Gynaecologists that deal with breast cancer in women should be more aware that it can happen to men.” (P4)

“The only thing that has really stuck in my mind is that my GP basically said the whole time: ‘That's great and I'm pleased that you have come to me. I have never had a man with breast cancer before (…) at last we've got one here’.”. (P18)

On the other hand, men had the impression that professionals were unsure, which specialist was responsible for MBC care and whether they would be reimbursed for treating males. Consequently, some said doctors had refused to treat them and described difficulties finding a doctor for their aftercare. They therefore felt HCP should be instructed in MBC care and its reimbursement.

“My GP said: ‘I don't know what to do any more, it's not my specialty area. I'll have to refer you to someone else’. And the other doctor said, ‘This is a women's practice (…) and we can't get reimbursed for men, we don't want men here.’” (P7)

Standard Procedures Do Not Take Men into Account

In general, men were satisfied with their medical care. Nonetheless, some felt that MBC patients are “irrelevant to the system” (P1). Besides, they had the impression that guidelines, breast cancer research, and standard procedures in hospitals and practices, failed to consider the needs of male patients. Men were annoyed at being called “Mrs.”, e.g., in discharge letters and waiting rooms.

“It recently happened again that I received a bill from the accounting centre addressed to ‘Mrs. XY’, right? I didn't really care at first, but it gets on my nerves now.” (P6)

Category 3: Coping

Men reflected upon several strategies that helped them to cope with their disease.

Wives' Support

All married patients said it was mainly social and emotional support from their wives that helped them cope. In addition, some stated that their breast cancer was only discovered because their wives encouraged them to seek medical advice.

“I'm glad I have my wife (…) I don't know how it would have ended.” (P7)

Support Groups

Members of the MBC support group reported that attending the group had improved their quality of life. In this context, they appreciated informational support and sharing experiences (e.g., regarding side effects). They also welcomed group efforts to increase public awareness of MBC by giving interviews, distributing brochures, and attending congresses.

“To be honest, I don't know how I would be managing if I had never had (the support group). They gave me back the will to live and I will always be grateful for that.” (P5)

Two of these men even joined mixed-sex support groups and reported positive effects, while others were critical of mixed groups because of the different needs of men and women.

In contrast, patients from the hospital had no experiences of support groups and were rather skeptical about them.

“It might not have helped at all. I imagine that if men had come along who were in a worse state than me, it wouldn't have encouraged me and might have depressed me.” (P16)

Other Coping Strategies

Few stated that they relied on additional coping strategies such as physical activity and acupuncture, but some considered psychosocial services such as group or individual therapy and hospital social services helpful.

Category 4: Supportive Care Needs

Participants expressed wishes for future MBC care.

Psychosocial

Patients stated their need for male-specific psychosocial support. One patient felt “left in the cold” (P2) after receiving his diagnosis. Another man said he was “desperately looking for a psycho-oncologist” (P18) who was familiar with MBC, but without success.

“Social and psychological support could be strengthened right at the beginning, when you get the diagnosis.” (P5)

Some patients would welcome more opportunities to share their experiences with other affected men.

Informational

Another criticism focused on a lack of patient information. Information on the internet or in leaflets was often reported to focus only on women and to be poorly adapted to meet the needs of men. They would have been interested in receiving information on side effects and treatment options. Breast care centers for men were considered unrealistic, but one patient suggested that “MBC consultation hours every couple of weeks” (P6) might be enough.

Discussion

The current study sought to understand the perspectives and needs of men with breast cancer in Germany. Despite the small and distinct population, we were able to capture a wide range of experiences, coping strategies and to identify barriers as well as supportive care needs.

In general, patients did not feel embarrassed about having a “women's disease.” In fact, men were more bothered by reactions from others, especially when they responded with disbelief. Patients felt they had to justify themselves for having been diagnosed with a “women's disease.”

Although some reported role strain, stigmatization and doubts related their masculinity, the overall perception of having breast cancer was one of being exotic. Previous qualitative [3, 9, 12, 29] as well as quantitative studies [30] support these findings. Our results also confirm the already described great variability with respect to patients' body image [9, 12, 14], but moreover, we found that patients generally had few concerns with regard to their mastectomy. Considering our participants' mean age of 68.5 years, this may confirm the results of a qualitative study indicating that changes in body image affect younger men more [11].

Our findings show that patients coped well with the disease and support results of a quantitative study showing significantly higher scores among males than females with breast cancer regarding their health-related quality of life [30]. This is, however, not surprising, as it has been shown in our and as well in other studies that men consider their disease less life changing than women [13, 14]. Other authors expressed the general view that men are not interested in attending support groups or talking to other men [9, 11, 12, 13]. Our results only confirm this for patients who have never participated in such groups. On the contrary, more than half of our study population actively took part in a MBC support group and considered the opportunity to share experiences with other men important and valuable. As it has been demonstrated for women, our results indicate that attending support groups and public engagement generally helps raising the quality of life and improve disease management [17, 18].

With regard to the inappropriate reactions of HCP observed in our study, previous findings indicate that gender seems to have an impact on breast cancer treatment and that some HCP appear to be discomfited by males with breast cancer [13]. In a focus group study, HCP explained that men tend to react stoically on receiving their breast cancer diagnosis, whilst women are likely to react emotionally. Influenced by their patients' reactions, HCP therefore dealt differently with men (being more objective) and women (being more sensitive) [14]. Nevertheless, HCP, and in particular GPs, should adopt a sensitive approach with all their patients [3, 12], as they have a major influence on health outcomes and patient satisfaction [15, 31]. Overall, raising awareness of MBC among HCP is key to an early diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

However, our participants not only described personal experiences but also addressed structural barriers that are rarely mentioned in the literature. This particularly includes patients' impressions that standard procedures are not geared to treating male patients with breast cancer, and that HCP need instruction in their responsibilities and reimbursement for MBC treatment. Confirming previous research, we found that patient information does not address patients' information needs [9, 11, 12, 14]. Additionally, our participants criticized breast cancer care and research for not adequately considering men. Our study results support previous findings underlining the importance of implementing male-specific guidelines and confirm that psychosocial services for men with breast cancer are rare and urgently needed [3, 5].

Strengths and Limitations

One strength of our study is the qualitative study design. This approach enabled us to gain diverse and new insights into a sensitive topic, which had not yet been covered by the literature. Telephone interviews proved themselves to be appropriate means of investigating this issue.

The homogeneity of our sample may reduce general applicability to men with breast cancer. As participants in this study were already receiving aftercare, and patients who have only recently been diagnosed or those whose health status is worse may have differing views, further studies should include populations at different stages of the disease. Some findings may not be applicable to other countries because of differences between healthcare systems. A potential interviewer effect due to T.S.N.s female sex cannot be determined.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study on the experiences and care needs of men with breast cancer in Germany. Breast cancer is still generally regarded as a ‘women's disease’, and male sex seems to hinder access to adequate care and medical services. Raising awareness in both the general population and among HCP is therefore essential. HCP should appreciate the seriousness of the disease among men and women alike and offer male-specific information and support. The study also shows that affected men see a need to generate study evidence on the effects and side effects of therapeutic regimens in men, especially hormonotherapy. They not only wish to be addressed as males in written information materials but also throughout the process of care. Furthermore, specialized consultation hours for men with breast cancer would be welcomed, and training for HCP should include information on reimbursement. Professionals should consider the psychological and social implications of the disease in men the same way as they do in women, and offer psychosocial support and encouragement to take part in support groups.

Statement of Ethics

This qualitative study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Christian Albrecht University Kiel, Germany, in July 2015 (reference No. D 502/15).

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions

T.S.N. contributed to the study design, recruitment of study participants, data collection and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. H.K. supervised the study, contributed to the study design, data analysis, and commented on successive drafts. M.B. and N.M. contributed to the recruitment of study participants and commented on successive drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all interview partners for participating in the study. We thank Petra Richter for reviewing the interview guideline and Martin Williamson for commenting on a former version of the manuscript. We thank Phillip Elliott for the language review and Beate Müller for her support during the process of writing this paper.

References

- 1.Zentrum für Krebsregisterdaten Datenbankabfrage. Diagnose: Brustdrüse (C50), 2017 https://www.krebsdaten.de/Krebs/SiteGlobals/Forms/Datenbankabfrage/datenbankabfrage_stufe2_form.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudlowski C. Male Breast Cancer. Breast Care (Basel) 2008;3((3)):183–9. doi: 10.1159/000136825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson JD, Metoyer KP, Jr, Bhayani N. Breast cancer in men: a need for psychological intervention. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2008 Jun;15((2)):134–9. doi: 10.1007/s10880-008-9106-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas E. Original Research: men's awareness and knowledge of male breast cancer. Am J Nurs. 2010 Oct;110((10)):32–7. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000389672.93605.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.da Silva TL. Male breast cancer: medical and psychological management in comparison to female breast cancer. A review. Cancer Treat Commun. 2016;7:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sousa B, Moser E, Cardoso F. An update on male breast cancer and future directions for research and treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013 Oct;717((1-3)):71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krebsgesellschaft D, Krebshilfe D. AWMF: S3-Leitlinie Früherkennung, Diagnose, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms, Version 4. 1, 2018 AMWF Registernummer: 032-045OL, 2018 http://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/mammakarzinom/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bateni SB, Davidson AJ, Arora M, Daly ME, Stewart SL, Bold RJ, et al. Is Breast-Conserving Therapy Appropriate for Male Breast Cancer Patients? A National Cancer Database Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019 Jul;26((7)):2144–53. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07159-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.France L, Michie S, Barrett-Lee P, Brain K, Harper P, Gray J. Male cancer: a qualitative study of male breast cancer. Breast. 2000 Dec;9((6)):343–8. doi: 10.1054/brst.2000.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quincey K, Williamson I, Winstanley S. ‘Marginalised malignancies’: A qualitative synthesis of men's accounts of living with breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2016 Jan;149:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iredale R, Brain K, Williams B, France E, Gray J. The experiences of men with breast cancer in the United Kingdom. Eur J Cancer. 2006 Feb;42((3)):334–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pituskin E, Williams B, Au HJ, Martin-McDonald K. Experiences of men with breast cancer: A qualitative study. J Mens Health Gend. 2007;4((1)):44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naymark P. Male breast cancer: incompatible and incomparable. J Mens Health Gend. 2006;3((2)):160–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams BG, Iredale R, Brain K, France E, Barrett-Lee P, Gray J. Experiences of men with breast cancer: an exploratory focus group study. Br J Cancer. 2003 Nov;89((10)):1834–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kipling M, Ralph JE, Callanan K. Psychological impact of male breast disorders: literature review and survey results. Breast Care (Basel) 2014 Feb;9((1)):29–33. doi: 10.1159/000358751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis S, Willis K, Yee J, Kilbreath S. Living Well? Strategies Used by Women Living With Metastatic Breast Cancer. Qual Health Res. 2016 Jul;26((9)):1167–79. doi: 10.1177/1049732315591787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matzat J. Selbsthilfegruppen und Gruppenpsychotherapie. In: Strauß B, Mattke D, editors. Gruppenpsychotherapie. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2012. pp. pp. 477–91. [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CH, Taal E, Shaw BR, Seydel ER, van de Laar MA. Empowering processes and outcomes of participation in online support groups for patients with breast cancer, arthritis, or fibromyalgia. Qual Health Res. 2008 Mar;18((3)):405–17. doi: 10.1177/1049732307313429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coreil J, Wilke J, Pintado I. Cultural models of illness and recovery in breast cancer support groups. Qual Health Res. 2004 Sep;14((7)):905–23. doi: 10.1177/1049732304266656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robert-Koch-Institut . Brustkrebs. Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. Volume 25. Berlin: Oktoberdruck; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McIntosh MJ, Morse JM. Situating and Constructing Diversity in Semi-Structured Interviews. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2015 Aug;2:2333393615597674. doi: 10.1177/2333393615597674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulz M, Ruddat M. Let's talk about sex! Über die Eignung von Telefoninterviews in der qualitativen Sozialforschung. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2012;13:2. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carr EC, Worth A. The use of telephone interview for research. NT Research. 2001;6((1)):511–24. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helfferich C. Die Qualität qualitativer Daten. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.audiotranskription: f4transkript, dr. dresing & pehl GmbH.

- 26.VERBI Software Consult. Sozialforschung. GmbH: MAXQDA. The art of data analysis: https://www.maxqda.de/produkte. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayring P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken, 11. aktualisierte und. überarbeitete Auflage. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz-Verlag; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007 Dec;19((6)):349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brain K, Williams B, Iredale R, France L, Gray J. Psychological distress in men with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Jan;24((1)):95–101. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kowalski C, Steffen P, Ernstmann N, Wuerstlein R, Harbeck N, Pfaff H. Health-related quality of life in male breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012 Jun;133((2)):753–7. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-1970-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenfield G, Foley K, Majeed A. Rethinking primary care's gatekeeper role. BMJ. 2016 Sep;354:i4803. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]