Abstract

Background:

Characteristics of neonatal tracheal intubations (TI) may vary between the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and delivery room (DR). The impact of setting on TI outcomes is not well characterized.

Objective:

To define variation in neonatal TI practice between settings, and identify the association between setting and TI success and safety outcomes.

Design:

Retrospective cohort study of TIs in the National Emergency Airway Registry for Neonates from 10/2014–9/2017. Setting (NICU vs. DR) was the exposure of interest. Outcomes were first attempt success, course success, success within four attempts, adverse TI associated events (TIAEs), severe desaturation, and bradycardia. We compared TI characteristics and outcomes between settings in univariable analysis. Factors significant in univariable analysis (p <0.1) were included in a logistic regression model, with adjustment for clustering by center, to identify the independent impact of setting on TI outcomes.

Results:

There were 3145 TI encounters (2279 NICU, 866 DR) in 9 centers. Almost all baseline characteristics significantly varied between settings. First attempt success rates were 48% (NICU) and 46% (DR). In multivariable analysis, setting was not associated with first attempt success. DR was associated with a higher adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of success within four attempts (1.48, 95% CI 1.06–2.08) and a lower aOR of bradycardia (0.43, 95% CI 0.26–0.71).

Conclusion(s):

Significant differences in patient, provider, and practice characteristics exist between NICU and DR TIs. There is substantial room for improvement in first attempt success rates. These results suggest interventions to improve safety and success need to be targeted to the distinct setting.

Keywords: Delivery Room, Intubation, Neonate, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Newborn Resuscitation

Introduction:

Neonatal tracheal intubation (TI) is a high-risk, life-saving procedure performed in both neonatal intensive care units (NICU) and delivery rooms (DR). While the DR and the NICU are both designed for neonatal care, they are distinct environments that serve complimentary but distinct purposes. DR care focuses on supporting the immediate transition of neonates from fetal life to extrauterine life. It is an environment where acute resuscitation and intubation are anticipated and expected. In contrast, NICU care goals extend beyond stabilization to include growth and development. In this environment, acute resuscitative intubations are less expected. Additionally, these environments often differ in terms of available personnel and equipment. Despite these differences, previous studies have not distinguished TIs in the NICU from TIs in the DR in analysis,(1–3) or have examined TIs in only one setting.(4–6)

Prior studies have shown training level of airway provider, premedication, and video laryngoscopes (VL) are associated with improved safety and success in neonatal TIs.(3,6–9) However, characteristics associated with success and safety may vary between the NICU and DR, and the impact of setting on neonatal TI practice and outcomes is not well characterized. Our study objectives were to define variation in neonatal TI practice between the DR and NICU settings and to identify any association between setting and neonatal TI success and safety outcomes.

Methods:

Setting and Design:

This was a retrospective cohort study using prospectively collected data in the international multi-center NEAR4NEOs registry. NEAR4NEOs is an airway registry that includes academic centers in North America, Asia, Australia, and Europe. We included sites that contributed ≥20 intubations in both the NICU and DR from the registry inception in October 2014 through December 2017. NEAR4NEOs database was granted institutional review board approval or was deemed quality improvement exempt from institutional review board oversight at all centers.

We included all TI encounters performed by NICU providers via oral or nasal approach. NICU providers included neonatal attendings, neonatal fellows, pediatric residents, nurse practitioners (NP), physician’s assistant (PA), hospitalists, and respiratory therapists. Exclusion criteria included intubations performed by non-NICU providers (surgeons, otolaryngologists, and anesthesiologists), change of tube intubations, noninvasive surfactant administration via catheter, intubations using a device other than a conventional laryngoscope or VL, tracheostomy placement, and laryngeal mask airway placement. Change of tube intubations were excluded as the procedure is inherently different from primary intubations. Only the first course (defined below) of each encounter was analyzed.

Exposure:

TI setting, NICU versus DR, was the exposure of interest.

Outcomes:

The primary outcome was first attempt success. Secondary outcomes were course success, success by four attempts, number of attempts, adverse tracheal intubation-associated events (TIAEs), severe oxygen desaturation, and bradycardia.

NEAR4NEOs Definitions:

Operational definitions were consistent with NEAR4NEOs as previously described.(7) A course refers to one method or approach to airway management, including premedication. An attempt is defined as a single advanced airway maneuver beginning with insertion of a device (i.e. laryngoscope) and ending when the laryngoscope is removed or advanced airway is placed. Multiple attempts can be made by different providers within the same course. However, if device, approach (oral vs. nasal), or premedication regimen is changed, this signifies a new course. Device was documented as VL if a VL was used regardless of indirect or direct view. Premedications were classified as sedatives and paralytics.

Successful airway management was defined as endotracheal tube placement in the trachea confirmed by chest rise, auscultation, supervising provider’s indirect confirmation on video screen (if using VL), second independent laryngoscopy, carbon dioxide detection, and/or chest radiograph. First attempt success was defined as successful intubation on the first attempt by the first provider. Course success was defined as successful intubation by any provider on any attempt within the first course. We also analyzed success within four attempts within the first course. Number of attempts was defined as the number of attempts for the entire course regardless of course success.

Safety outcomes included adverse TIAEs, severe desaturation, and bradycardia. TIAEs were categorized as severe and non-severe as previously described.(7) Per NEAR4NEOs definitions, physiologic measures are reported separately from TIAEs. Severe desaturations were defined as ≥20% decrease in oxygen saturation from the highest level immediately before the first attempt of the course and the lowest measured SpO2 during the course. Severe oxygen desaturation was only reported for TIs with available SpO2. Bradycardia was defined as lowest heart rate (HR) <100 beats per minute (bpm) if the highest HR immediately before the first intubation attempt of the course was ≥120 bpm. Bradycardia was only reported for TIs with available HR data and initial HR ≥120 bpm.

Statistical Analysis:

All analyses were conducted using Stata 15.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). We used univariable analysis to compare patient, provider, practice characteristics, and outcomes between settings using a χ2 test or Fischer’s exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for nonparametric variables. To identify the independent effect of setting on primary and secondary outcomes, we developed a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model with adjustment to the standard errors for clustering by center. Characteristics that differed between settings in univariable analysis with p<0.1 were included as covariates in the model. Given the extent of overlap between patient diagnosis and indication for intubation, only indication was included in the multivariable analysis, consistent with prior publications.(7,8) We only adjusted for current patient weight given the anticipated collinearity between gestational age at birth and weight. We also only adjusted for first airway provider in our analysis.

We preformed two post hoc sensitivity analyses. The first sensitivity analysis excluded TIs from one large quaternary referral center with a specialized delivery service for neonates with congenital anomalies, as this setting may not be representative of a traditional perinatal delivery hospital. The second sensitivity analysis examined only NICU TIs for neonates ≤1 day old in order to create a NICU cohort that was more similar in terms of postnatal age to the DR cohort.

Results:

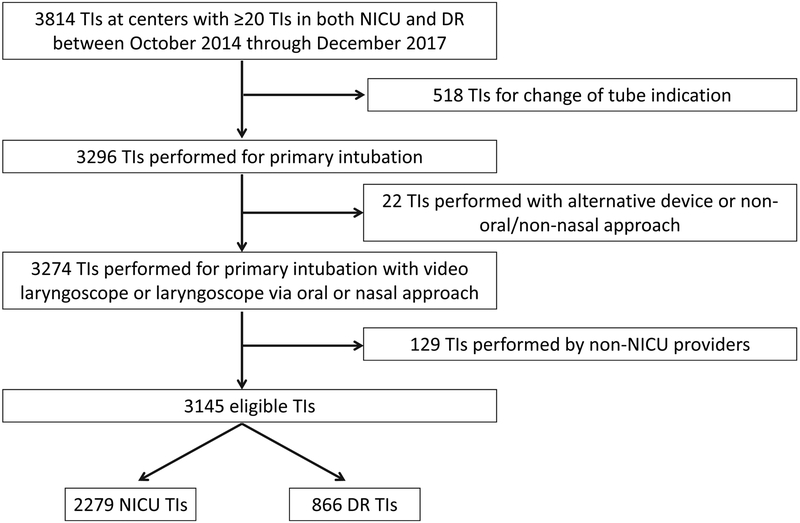

There were 9 centers that contributed ≥20 TI in both the NICU and the DR during the study period with a total of 3145 eligible TIs; 2279 in the NICU and 866 in the DR (Figure 1). Most patient characteristics were significantly different between settings (Table 1). Acute respiratory failure was the most common diagnosis in both the NICU and DR.

Figure 1:

Flow Diagram

Table 1:

Patient Characteristics of Neonatal Intubations, by Setting

| NICU n=2279 |

Delivery Room n=866 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight at intubation, grams; median (IQR) | 1650 (950, 2947) | 1244 (770, 2700) | <0.001 |

| GA at birth, weeks; median (IQR) | 28 (25, 34) | 29 (26, 36) | <0.001 |

| Postnatal age, days; median (IQR) | 10 (1, 47) | N/A | N/A |

| Diagnosis:* n (%) | |||

| Acute Respiratory Failure | 1415 (62.1%) | 647 (74.7%) | <0.001 |

| Congenital Anomaly Requiring Surgery | 146 (6.4%) | 149 (17.2%) | <0.001 |

| Congenital Heart Disease | 136 (6.0%) | 83 (9.6%) | <0.001 |

| Neurologic Impairment | 149 (6.5%) | 21 (2.4%) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 144 (6.3%) | 14 (1.6%) | <0.001 |

| Airway and/or Craniofacial Anomaly | 114 (5.0%) | 21 (2.4%) | 0.001 |

| Chronic Respiratory Failure | 516 (22.6%) | 2 (0.2%) | <0.001 |

| Indication;* n (%) | |||

| Ventilation Failure | 811 (35.6%) | 109 (12.6%) | <0.001 |

| Oxygen Failure | 692 (30.4%) | 180 (20.8%) | <0.001 |

| Surfactant administration | 508 (22.3%) | 291 (33.6%) | <0.001 |

| Frequent Apnea and Bradycardia Events | 450 (19.7%) | 41 (4.7%) | <0.001 |

| Reintubation after Unplanned Extubation | 283 (12.4%) | 5 (0.6%) | <0.001 |

| Procedure | 232 (10.2%) | 2 (0.2%) | <0.001 |

| Other | 106 (4.7%) | 6 (0.7%) | <0.001 |

| Upper Airway Obstruction | 92 (4.0%) | 4 (0.5%) | <0.001 |

| Unstable Hemodynamics | 49 (2.2%) | 21 (2.4%) | 0.64 |

| DR, Clinical Indication | N/A | 601 (69.4%) | N/A |

| DR, Routine Practice for Diagnosis** | N/A | 123 (14.2%) | N/A |

NICU= neonatal intensive care unit, DR= delivery room, GA= gestation age, IQR= interquartile range, N/A= not applicable

More than one indication can be selected for a given encounter. Diagnosis and indications occurring in <1% of the population not reported

DR- Routine Practice for Diagnosis= TI based on a specific diagnosis, i.e. certain hospitals may intubate all neonates below a certain GA or all neonates with a certain diagnosis such as congenital diaphragmatic hernia

Almost all provider and practice characteristics were significantly different between settings (Table 2). NP/PA/Hospitalist providers were the most frequent first airway providers in the NICU (45%), while fellows were the most frequent first airway provider in the DR (50%). Supplemental Figure 1 demonstrates airway providers for each of the first four attempts. Most intubations were performed with a conventional laryngoscope, but VL was used more frequently in the NICU than DR (23% vs. 12%, P<0.001). The use of sedatives and paralytics was more common in the NICU than DR.

Table 2:

Provider and Practice Characteristics of Neonatal Intubations, by Setting

| NICU n=2279 |

Delivery Room n=866 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Airway Provider; n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| NP/PA/Hospitalist | 1026 (45.0%) | 350 (40.4%) | |

| Neonatal Fellow | 724 (31.8%) | 431 (49.8%) | |

| Pediatric Resident | 321 (14.1%) | 25 (2.9%) | |

| Neonatal Attending | 120 (5.3%) | 41 (4.7%) | |

| RRT | 63 (2.8%) | 11 (1.3%) | |

| Other | 25 (1.1%) | 8 (0.9%) | |

| Device used; n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Laryngoscope | 1750 (76.8%) | 760 (87.8%) | |

| Video Laryngoscope | 529 (23.2%) | 106 (12.2%) | |

| Approach; n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Oral | 2205 (96.8%) | 861 (99.4%) | |

| Nasal | 74 (3.2%) | 5 (0.6%) | |

| Stylet; n (%) | 1449 (63.7%) | 626 (72.5%) | <0.001 |

| Premedication;* n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| No sedation or Paralytic | 866 (38.0%) | 774 (89.4%) | |

| Sedation plus Paralytic | 1026 (45.0%) | 71 (8.2%) | |

| Sedation only | 382 (16.8%) | 20 (2.3%) |

NP= nurse practitioner, PA= physician assistant, RRT= registered respiratory therapist

Paralysis alone in <1%

The first attempt was successful in <50% of intubations in both the NICU and DR, and this did not differ between settings in univariable analysis (Table 3). Course success did not differ between settings, however success within four attempts was less common in the NICU than DR (90% vs. 93%, P=0.01). There was no difference in median number of attempts or rates of TIAEs between settings. TIAEs occurred in 20% of NICU TIs and 19% of DR TIs, and severe TIAEs occurred in 5% of TIs in both settings. Types of TIAEs were similar between settings (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 3:

Univariable Analysis of Intubation Outcomes, by Setting

| NICU n=2279 |

Delivery Room n=866 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Attempt Success; n (%) | 1091 (47.9%) | 402 (46.4%) | 0.47 |

| Course Success; n (%) | 2183 (95.8%) | 826 (95.4%) | 0.62 |

| Success within 4 attempts; n (%) | 2045 (89.7%) | 805 (93.0%) | 0.01 |

| Number of attempts; median (IQR) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 2) | 0.46 |

| Any TIAE; n (%) | 449 (19.7%) | 165 (19.1%) | 0.68 |

| Severe TIAE;* n (%) | 114 (5.0%) | 40 (4.6%) | 0.66 |

| Severe desaturation;** n (%) | 1154 (52.5%) n=2197 | 222 (34.4%) n=645 | <0.001 |

| Bradycardia;*** n (%) | 601 (29.1%) n=2063 | 94 (20.2%) n=465 | <0.001 |

TIAE= tracheal intubation adverse event

Cardiac arrest, cardiac compressions <1 minute, esophageal intubation with delayed recognition, emesis with aspiration, hypotension requiring treatment, laryngospasm, pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum, airway injury

Defined as ≥20% decrease, reported only for patients with SpO2 data available

Defined as HR<100 beat per minute (bpm) if starting HR≥120 bpm, reported only for patients with HR data available and initial HR≥120

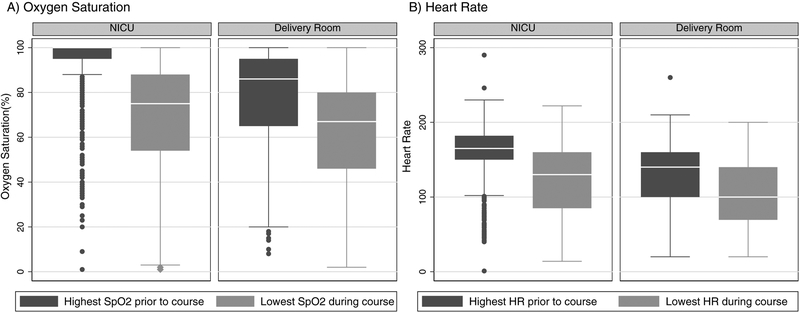

Oxygen saturation data was missing for 82 (4%) of NICU TIs and 221 (26%) of DR TIs. HR data was missing for 102 (4%) of NICU TIs and 186 (21%) of DR TIs. In univariable analysis, severe oxygen desaturation and bradycardia were more common during NICU TIs than DR TIs (53% vs. 34%, P<0.001 and 29% vs. 20%, P<0.001 respectively). However, the median pre-intubation oxygen saturation was higher in the NICU than the DR (100% SpO2, IQR 95%−100% vs. 86% SpO2, IQR 65%−95%, P<0.001; Figure 2a). Median pre-intubation HR was also higher in the NICU than the DR (165 bpm, IQR 150–182 vs. 140 bpm, IQR 100–160, P<0.001; Figure 2b).

Figure 2:

Box plot (median, IQR, and range) A) demonstrating highest percent oxygen saturation (SpO2) prior to course and lowest documented level during course* B) demonstrating highest heart rate (HR) prior to course and lowest HR during intubation course**

* Reported only for patients with SpO2 data available: NICU: n=2197, DR: n=645

** Reported only for patients with HR data available: NICU: n=2177, DR: n=680

***Median difference in highest pre-intubation SpO2 and lowest SpO2 was larger in the NICU than the DR (20%, IQR 8%−40% versus 12%, IQR 5%−23%, P<0.001). Median difference in highest pre-intubation HR and lowest HR was larger in the NICU than the DR (26 bpm, IQR 10–70 versus 20 bpm, IQR 5–40, P<0.001).

In multivariable analysis (Table 4), there was no difference in first attempt success or course success between settings. DR setting was associated with a higher adjusted odds (aOR) of success within four attempts (1.48, 95% CI 1.06–2.08) and a lower aOR of bradycardia (0.43, 95% CI 0.26–0.71). Setting was not associated with a difference in the odds of severe desaturation or TIAEs.

Table 4:

Multivariable Analysis of Intubation Outcomes, by Setting*

| aOR (95% CI) DR, compared to NICU |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| First Attempt Success | 1.01 (0.79 to 1.28) | 0.94 |

| Course Success | 0.75 (0.34 to 1.63) | 0.47 |

| Success within 4 attempts | 1.48 (1.06 to 2.08) | 0.02 |

| Any TIAE | 0.77 (0.59 to 1.00) | 0.05 |

| Severe TIAE | 0.72 (0.49 to 1.05) | 0.08 |

| Severe desaturation | 0.60 (0.35 to 1.03) | 0.06 |

| Bradycardia | 0.43 (0.26 to 0.71) | 0.001 |

aOR= adjusted odds ratio, CI= confidence interval

After adjustment for weight at intubation, stylet, approach, device, pre-medication, indication, provider, and clustering by center

Our first sensitivity analysis excluding 940 TIs (712 NICU and 228 DR) from a large quaternary referral center showed no change in associations in univariable analysis. In multivariable analysis, while the DR remained associated with increased aOR of success within four attempts and decreased aOR of bradycardia, it was also associated with a decreased aOR of course success (0.44, 95% CI 0.26–0.74, Supplemental Table 2). Our second sensitivity analysis examining only TIs performed in neonates ≤1 day old included 1555 TIs (689 NICU and 866 DR). In multivariable analysis, DR remained associated with higher aOR of success within four attempts (1.60, 95% CI 1.12–2.30) but setting was no longer associated with a difference in bradycardia (Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion:

This retrospective cohort study examined neonatal TI practice variation between the NICU and the DR, and the effect of setting on TI success and safety. Significant differences were identified in almost all patient, provider, and practice characteristics of TIs between the NICU and DR. There was no difference in the primary outcome of first attempt success between settings. However, the DR setting was independently associated with increased odds of success within four attempts and lower odds of bradycardia during intubation.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to directly compare differences between neonatal TIs in the NICU and DR and to examine the impact of setting on neonatal TIs. We found significant differences in almost all characteristics between settings, and these results were not attenuated in sensitivity analyses. Some of the provider variation may be explained by differences in staffing models between settings. Provider variation may also be explained by patient acuity as patients in the DR were smaller and had lower pre-intubation median HR and SpO2 (140 bpm vs 165 bpm and 86% vs 100%). Prior studies have shown increased TI success rates with increased level of provider training,(3,7,8) which may explain why residents were less frequently first airway providers in the DR for these higher acuity patients.

The reduced rates of video laryngoscopy and pre-medication in the DR may partly be explained by feasibility. Patient size and availability of equipment may have been limiting factors in usage of video laryngoscopy in the DR. Similarly, need for emergent intubations and lack of IV access may limit use of pre-medication in DR setting. Further, pre-medication is not recommended for depressed neonates who require intubation for resuscitation. Despite these constraints, there may be opportunities to increase use of these two practices in the DR as appropriate, as they have been shown to improve safety and success.(3,6–9)

We were unable to find comparable neonatal data describing the impact of setting on neonatal TI. There are however limited studies examining the impact of setting on pediatric TI practice and outcomes. Similar to our findings, authors have reported significant variation in patient, practice, and provider characteristics of pediatric intubations by setting.(10,11) Gradidge et al examined the impact of type of ICU (cardiac versus non-cardiac) on safety of pediatric TIs in children with cardiac disease. They found significant differences in patient, provider, and practice characteristics between settings with similar safety outcomes. Langhan et al found significant difference in waveform capnography use between pediatric ICUs and emergency departments.

Despite differences in almost all TI characteristics, there was no significant difference in first attempt success or overall course success between the NICU and DR. However, the DR was associated with higher aOR of success within four attempts. We hypothesize that this may in part be due to the fact that airway management was escalated more frequently to an attending provider by the fourth attempt in the DR, likely because patients in the DR tended to have less stable physiology with lower median starting oxygen saturations and HR. In our sensitivity analysis excluding a large quaternary referral center, DR was associated with a lower aOR of course success but continued to be associated with an increased aOR of success within four attempts. Given that the absolute rates of course success were high in both settings (95–96%), this may represent a statistically significant difference that is not clinically relevant.

We found that the DR setting was associated with lower aOR of bradycardia. We speculate this may have been influenced by both the missingness of data and the study definition: HR<100 bpm if pre-intubation HR was ≥120 bpm. Relatively more neonates in the DR were missing HR data (21% versus 4%) or had pre-intubation HR<120 (25% versus 5%), resulting in the exclusion of significantly more TIs in the DR (46% versus 9.5%) for bradycardia analysis. It is possible we may not have seen this difference had these infants been included. Additionally, in the sensitivity analysis restricted to neonates ≤1 day old, setting was no longer independently associated with bradycardia.

Success and safety outcomes remain suboptimal in both settings with first attempt success rates <50% and TIAE rates of 19–20%. Our first attempt and overall success rates are similar to those reported in smaller studies.(4,12–14) However, comprehensive data about TIAEs are relatively underreported outside of the NEAR4NEOs registry.(13,14) The rate of adverse events in this study was lower than the rate reported by Hatch et al, 39% for 273 TIs.(13) This is likely do to a difference in definitions of adverse events, as they include physiologic outcomes (bradycardia (<60 bpm) and hypoxemia (<60%)) as adverse events, while NEAR4NEOs reports these separately. Our results emphasize the continued need for improvement with this high-risk procedure. Additionally, the significant differences in almost all characteristics between settings suggest interventions to improve safety and success need to be targeted to the distinct setting.

We acknowledge study limitations. NEAR4NEOs data is collected via self-report. Each site underwent extensive training prior to initiation of data collection, but the possibility of reporting bias remains. Compared to the NICU, the DR was missing large amounts of physiologic data, which could have biased our results as it likely excluded the most physiologically unstable patients from analysis. NEAR4NEOs data also does not capture timing of intubation related interventions, which may impact neonatal outcomes. Additionally, NEAR4NEOs safety outcomes are proximal, and the data set does not include long-term outcome data. Lastly, the centers in this study are academic centers, and these patients and results may not be representative of community level NICUs.

Conclusion:

Significant differences in patient, provider, and practice characteristics exist between TI performed in the NICU and DR, suggesting that TIs performed in these two settings should be considered as two separate entities. These results suggest interventions to improve safety and success need to be targeted to the distinct setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Funding:

This project is supported by the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (R21HD089151–01A1).

A.N. is supported by the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (R21HD089151–01A1). E.F. is supported by a NICHD Career Development Award (K23HD084727). H.H. is supported by a NICHD Training Grant (T32HD060550–09). V.N. is supported by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Pediatric Critical Care Endowed Chair.

Footnotes

Statement of Ethics:

The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia served as the reviewing IRB for the multi-center study granted institutional review board approval or was deemed quality improvement (IRB number is 09–007253). Additionally, NEAR4NEOs database was exempt from institutional review board oversight at each individual center. All sites granted a wavier of informed parental consent for data collection and analysis.

Disclosure Statement:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Falck AJ, Escobedo MB, Baillargeon JG, Villard LG, Gunkel JH, Objective A. Proficiency of Pediatric Residents in Performing Neonatal. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leone TA, Rich W, Finer NN. Neonatal intubation: Success of pediatric trainees. J Pediatr. 2005;146(5):638–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Shea JE, Thio M, Kamlin CO, McGrory L, Wong C, John J, et al. Videolaryngoscopy to Teach Neonatal Intubation: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2015;136(5):912–9. Available from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2015-1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lane B, Finer N, Rich W. Duration of Intubation Attempts During. Pediatrics. 2004;67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Donnell CPF. Endotracheal Intubation Attempts During Neonatal Resuscitation: Success Rates, Duration, and Adverse Effects. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2006;117(1):e16–21. Available from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2005-0901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moussa A, Luangxay Y, Tremblay S, Lavoie J, Aube G, Savoie E, et al. Videolaryngoscope for Teaching Neonatal Endotracheal Intubation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2016;137(3):e20152156–e20152156. Available from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2015-2156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foglia EE, Ades A, Sawyer T, Glass KM, Singh N, Jung P, et al. Neonatal Intubation Practice and Outcomes: An International Registry Study. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2018;143(1):e20180902 Available from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/lookup/doi/10.1542/peds.2018-0902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foglia EE, Ades A, Napolitano N, Leffelman J, Nadkarni V, Nishisaki A. Factors Associated with Adverse Events during Tracheal Intubation in the NICU. Neonatology. 2015;108(1):23–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pouppirt NR, Nassar R, Napolitano N, Nawab U, Nishisaki A, Nadkarni V, et al. Association Between Video Laryngoscopy and Adverse Tracheal Intubation-Associated Events in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J Pediatr [Internet]. 2018;201:281–284.e1. Available from: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langhan ML, Emerson BL, Nett S, Pinto M, Harwayne-Gidansky I, Rehder KJ, et al. End-Tidal Carbon Dioxide Use for Tracheal Intubation: Analysis from the National Emergency Airway Registry for Children (NEAR4KIDS) Registry. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(2):98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gradidge EA, Bakar A, Tellez D, Ruppe M, Tallent S, Bird G, et al. Effect of location on tracheal intubation safety in cardiac disease-are cardiac ICUs safer? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(3):218–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haubner LY, Barry JS, Johnston LC, Soghier L, Tatum PM, Kessler D, et al. Neonatal intubation performance: Room for improvement in tertiary neonatal intensive care units. Resuscitation [Internet]. 2013;84(10):1359–64. Available from: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatch LD, Grubb PH, Lea AS, Walsh WF, Markham MH, Whitney GM, et al. Endotracheal Intubation in Neonates: A Prospective Study of Adverse Safety Events in 162 Infants. J Pediatr [Internet]. 2016;168:62–6. Available from: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.09.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaudhary R, Arasu A, Clarke P, Malviya M, Ponnusamy V, Anandaraj J, et al. Endotracheal intubation in a neonatal population remains associated with a high risk of adverse events. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;170(2):223–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.