Abstract

Aims

To compare the benefits and harms of naltrexone–bupropion using evidence from clinical study reports.

Methods

We searched Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency websites, PubMed, and Clinicaltrials.gov (May 2016) to identify pivotal trials; we then sent a freedom of information request to the European Medicines Agency (July 2016). We included pivotal, phase III placebo‐controlled trials. We assessed the risks of bias using the Cochrane criteria, and the quality of the evidence using GRADE. We used a random‐effects model for meta‐analyses.

Results

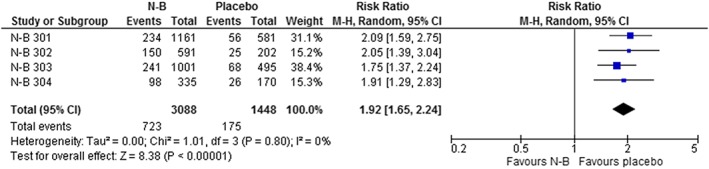

Over a 27‐month period (July 2016 to August 2018), we received 31 batches of clinical study report documents containing over 65 000 pages of data from 4 pivotal trials (n = 4536). Significantly more participants who took naltrexone–bupropion achieved ≥5% reduction in body weight: risk ratio (RR) = 2.1 (95% confidence interval 1.35–3.28), P = .001, GRADE = low, number needed to treat (NNT) to benefit = 5 (3–17); this represents a 2.53 kg (1.85–3.21) reduction in baseline body weight compared with placebo. Naltrexone–bupropion had significantly beneficial effects on other cardiovascular risk factors; however, the true effect sizes for these are uncertain because of incomplete outcome data. Naltrexone–bupropion significantly increased the risk of adverse events: RR = 1.11 (1.05–1.18, P = .0004, GRADE = low, NNT to harm = 12 7–27); serious adverse events: RR = 1.70 (1.38–2.1, P < .00001, GRADE = moderate, NNT to harm = 21 13–38); and discontinuation because of adverse events: RR = 1.92 (1.65–2.24, P < .00001, GRADE = moderate, NNT to discontinue treatment = 9 8–13).

Conclusions

Naltrexone–bupropion significantly reduces body weight by a small amount but significantly increases the risk of adverse events. A rigorous process of postmarketing surveillance is required.

Keywords: clinical study report, meta‐analysis, naltrexone–bupropion, obesity, systematic review

1. INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of overweight and obesity continues to increase, and they have become major public health challenges.1 In 2016, there were over 1.9 billion overweight adults globally, of whom 650 million were obese.2 Cost‐effective strategies to tackle this are urgently needed.3

Several drugs have been licensed for the management of overweight and obesity over the last 70 years. Most of them have central mechanisms of action and many have been withdrawn from the market because of unfavourable benefit–harm profiles.4 More recently, combination therapies that act via central pathways have been developed; these are now being licensed by drug regulatory authorities for clinical use.

Naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) is a combination formulation used as treatment option for long‐term management of overweight and obesity, in addition to exercise and a reduced‐calorie diet. Naltrexone acts by autoinhibition of pro‐opiomelanocortin neurons in the hypothalamus, while bupropion is thought to increase the actions of dopamine at specific sites in the brain.5 The combined effects of naltrexone and bupropion are thought to reduce food craving.

N‐B was licensed for obesity management by the European Medicines Agency (EMA; Mysimba) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA; Contrave) in September and December 2014 respectively. However, in July 2017, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence did not recommend N‐B for use in the UK, because of uncertainties over its clinical and cost effectiveness6; a reappraisal of the evidence for its effectiveness is expected to be conducted in 2020.

Clinical study reports (CSRs) are unabridged documents that provide detailed information on the methods and results of clinical trials.7 They contain, among other things, core reports, study protocols (including amendments), statistical analysis plans, randomization codes, case report and patient consent forms, patients' listings, results listings, case narratives, and approval documents. CSRs are used by drug regulators to assess the benefits and harms of new medicines before they grant marketing licences, and they provide more comprehensive data on trial methods and results than journal publications.8, 9

There has been no previous assessment of the benefit–harm profile of N‐B based on evidence from unpublished CSRs. Our objective was therefore to assess the benefits and harms of N‐B in the management of overweight and obesity, using the evidence from unpublished CSRs of pivotal clinical trials.

2. METHODS

We searched the EMA and FDA websites (May 2016) to identify pivotal phase III trials used by the drug manufacturer to gain marketing authorization for N‐B in both Europe and the USA (see Appendix 1). Using the approval documents from both regulatory websites, we searched for pivotal trials used to gain marketing approval. We mapped the IDs of pivotal trials in the regulatory documents to their corresponding journal publications by conducting searches on PubMed and http://clinicaltrials.gov (May 2016; see Appendix 2). We then contacted the EMA to request the CSRs of these trials. The review protocol was registered at PROSPERO (ID: CRD42018086618).

We included pivotal, placebo‐controlled, phase III trials on which marketing authorizations were based. If the pivotal trials contained other active comparator arms, such arms were excluded from the review.

Our primary outcomes were body weight (dichotomous outcome; proportion of participants who lost at least 5% body weight from baseline), adverse events and discontinuations due to adverse events. Secondary outcomes were body weight (continuous outcome), proportion of participants who lost at least 10% body weight from baseline, serious adverse events, waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, triglycerides, total cholesterol, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood glucose, and impact of weight on quality of life. We checked the retrieved CSRs using the following 2 criteria: (i) completeness; and (ii) internal consistency (see protocol for full description of terms). We extracted data on study ID, study design and setting, participant characteristics, description of interventions and placebos, study duration, lifestyle adjustments, and primary and secondary outcomes. We also extracted data on adverse events reported by trial investigators as possibly related or related to the intervention. Data were extracted by 1 reviewer (I.J.O.) and were independently cross‐checked by a second reviewer (J.J.L.). We assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane criteria.10 Two reviewers (I.J.O. and J.J.L.) independently assessed the risk of bias in the included CSRs. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

We used an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis (all randomized participants) to compare outcomes between N‐B and placebo. When there were 2 or more active treatment arms, they were combined to create single pair‐wise comparisons.11 Using the random‐effects model of RevMan 5.3 software,12 we computed risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes, and mean differences (MD) with 95% CIs for continuous outcomes. One reviewer (I.J.O.) entered the data for meta‐analysis, and these were independently cross‐checked by the second reviewer (J.J.L.). Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Using the control group event rates, we computed the number needed to treat (NNT) to benefit, the NNT to harm (NNTH) and the NNT to discontinue treatment, with their respective 95% CIs. We analysed the data on adverse events for all participants, and for participants whose adverse events were reported by the investigators as possibly related or related to the intervention. We assessed the quality of the evidence for each outcome using the Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria,13 which examine the following domains: (i) study design; (ii) risk of bias; (iii) inconsistency; (iv) indirectness; and (v) imprecision. Using the GRADEpro software (version 3.6),14 we rated evidence from high to very low. Because there were <10 pivotal trials, the publication bias domain was not used in rating the quality of the evidence. The quality of the evidence is upgraded when the overall effect estimate is dramatic: i.e. large (RR > 2 or < 0.5) or very large (RR > 5 or < 0.2) for dichotomous outcomes; or large (MD > 0.8) for continuous outcomes. We used GRADE evidence profiles to present the results.

3. RESULTS

Over a 27‐month period (between July 2016 and August 2018), we received 31 batches of CSR documents from the EMA, containing over 65 000 pages of relevant data for 4 pivotal trials (Figure S1; see Appendix 3 for a list of the component items in the CSRs). The 4 pivotal trials and their corresponding journal publications were NB‐301,15 NB‐302,16 NB‐303,17 and NB‐30418 (see Appendix Table 1 for regulatory, http://clinicaltrials.gov, and PubMed matching IDs); all were conducted in the USA, comprised 4536 participants in total, and lasted 6–12 months (see Appendix Table 2). The baseline body weight was 99.6–104.5 kg across the 4 studies. Active interventions were naltrexone sustained‐release 16 or 32 mg plus bupropion sustained‐release 360 mg. The composition of the placebo was not reported.

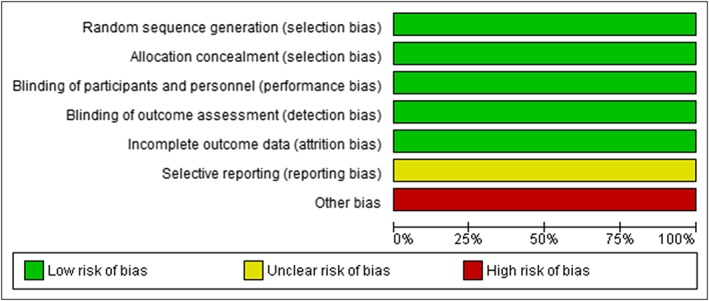

The risk of bias in 5 domains was low (Figure 1). We judged the incomplete outcome reporting domain as unclear, because full datasets were only reported for weight loss outcomes. We judged the other bias domain as high, because (i) most of the investigators had financial ties to the drug sponsor—industry affiliation is associated with poor adherence to clinical trial practices19; and (ii) there were high discontinuation rates across the trials. Overall, we rated the risk of bias as moderate.

Figure 1.

Risk of bias in pivotal clinical trials of naltrexone–bupropion (Mysimba)

3.1. Effect on body weight and other cardiovascular risk profiles

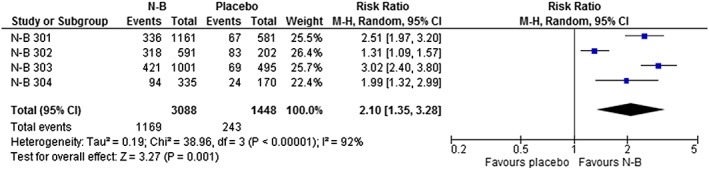

Significantly more participants in the N‐B group achieved at least a 5% reduction in body weight compared with placebo: RR = 2.1 (1.35 to 3.28); P = .001; I 2 = 92%; GRADE = low; NNT to benefit = 5 (3 to 17; Table 1; Figure 2). We observed similar findings when we compared participants who achieved at least a 10% reduction in body weight: RR = 2.58 (1.84 to 3.61); P < .00001; I 2 = 68%; GRADE = moderate (Appendix Figure 2). Participants in the N‐B group lost significantly more body weight from baseline: MD = –2.53 kg (–3.21 to –1.85); P < .00001; I 2 = 92%; GRADE = low (Table 1; Appendix Figure 3).

Table 1.

GRADE evidence profile question 1: what is the effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on body weight in overweight and obese subjects?

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Comments | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | N‐B | Placebo | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Proportion of participants who achieved at least 5% weight loss | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | Very seriousb | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationc | 1169/3088 (37.9%) | 243/1448 (16.8%) | RR 2.1 (1.35 to 3.28) | 185 more per 1000 (from 59more to 383 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ΟΟ LOW | NNTB 5 (3 to 17) |

| Proportion of participants who achieved at least 10% weight loss | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | seriousd | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationc | 685/3088 (22.2%) | 118/1448 (8.1%) | RR 2.58 (1.84 to 3.61) | 129 more per 1000 (from 68 more to 213 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTB 8 (5 to 15) |

| Change in body weight from baseline (kg; better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | Very seriousb | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associatione | 3088 | 1448 | ‐ | MD 2.53 lower (3.21 to 1.85 lower) | ⊕ ⊕ ΟΟ LOW | |

Settings: Academic and primary care centres; academic medical centres; private or institutional practices; research centres

High drop‐out rates; several investigators have financial ties to the study sponsor;

substantial heterogeneity;

RR > 2;

Moderate to severe heterogeneity;

MD > 0.8;

wide confidence interval.

CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; NNTB: number needed to treat to benefit; RR: risk ratio

Figure 2.

Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the proportion of participants who achieved ≥5% weight loss

The effects of N‐B on other cardiovascular risk profiles are shown in Appendix Figures 4–12. Compared with placebo, participants in the N‐B group had significant reductions in waist circumference (MD = −3.14 cm [−3.69 to −2.59], P < .0001, I2 = 0%); fasting triglycerides (MD = −0.05 mg/dL [−0.09 to −0.01], P = .03, I 2 = 80%); fasting low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (MD = −2.92 mg/dL [−5.16 to −0.69], P = .01, I 2 = 22%); and fasting blood glucose (MD = −1.19 mg/dL [−2.15 to −0.23], P = .02, I 2 = 1%); with significant increases in high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (MD = 3.04 mg/dL [2.40 to 3.68], P < .00001, I2 = 0%); systolic blood pressure (MD = 1.47 mmHg [0.48 to 2.47], P = .004, I 2 = 51%); and diastolic blood pressure (MD = 0.98 mmHg [0.50 to 1.45], P < .0001, I 2 = 0%). There were no significant differences in total cholesterol concentrations or quality‐of‐life scores. These results were not based on all randomized participants; we were unable to impute data to account for missing values, because of incomplete outcome data20, 21 (see Appendix Table 3 for the proportions of participants for whom outcome data were reported for cardiovascular risk profiles).

3.2. Adverse events

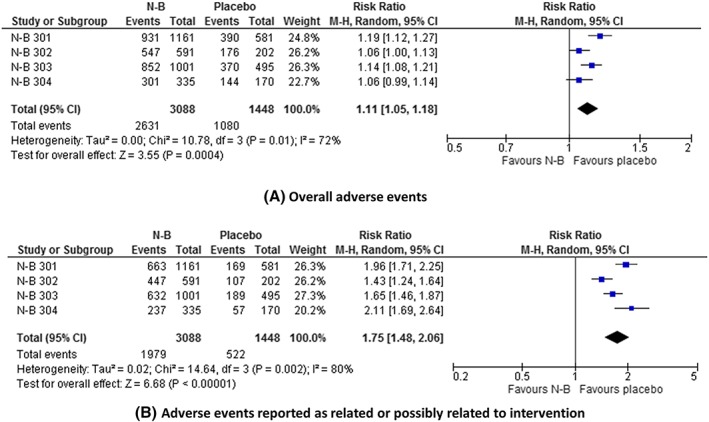

The data on adverse events are summarized in Table 2, Figure 3, and Appendix Figures 13–41. Overall, there was a significantly increased risk of adverse events with N‐B: RR = 1.11 (1.05 to 1.18); I2 = 72%; P < .00001 GRADE = low; NNTH = 12 (7 to 27). The risk of adverse events reported by investigators as related or possibly related to the intervention was also significantly greater with N‐B: RR = 1.75 (1.48 to 2.06); I 2 = 80% P < .00001; GRADE = very low; NNTH = 4 (3 to 6). Nervous system, psychiatric, vascular, gastrointestinal, and ear and labyrinth adverse events were significantly more common with N‐B.

Table 2.

GRADE evidence profile question 2: what is the effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of adverse events in overweight and obese subjects?

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Comments | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | N‐B | Placebo | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Overall adverse events | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | seriousb | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 2631/3088 (85.2%) | 1080/1448 (74.6%) | RR 1.11 (1.05 to 1.18) | 82 more per 1000 (from 37 more to 134 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ΟΟ LOW | NNTH 12 (7 to 27) |

| Adverse events reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | Very seriousc | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 1979/3088 (64.1%) | 522/1448 (36%) | RR 1.75 (1.48 to 2.06) | 270 more per 1000 (from 173 more to 382 more) | ⊕ΟΟΟ VERY LOW | NNTH 4 (3 to 6) |

| Nervous | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 1061/3088 (34.4%) | 269/1448 (18.6%) | RR 1.79 (1.57 to 2.05) | 147 more per 1000 (from 106 more to 195 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 7 (5 to 9) |

| Nervous events reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 777/3088 (25.2%) | 166/1448 (11.5%) | RR 2.15 (1.84 to 2.51) | 132 more per 1000 (from 96 more to 173 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTH 8 (6 to 10) |

| Headache—nervous | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 529/3088 (17.1%) | 146/1448 (10.1%) | RR 1.63 (1.38 to 1.94) | 64 more per 1000 (from 38 more to 95 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 16 (11 to 26) |

| Headaches reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 373/3088 (12.1%) | 99/1448 (6.8%) | RR 1.71 (1.38 to 2.12) | 49 more per 1000 (from 26 more to 77 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ΟMODERATE | NNTH 21 (13 to 39) |

| Dizziness—nervous | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 290/3088 (9.4%) | 51/1448 (3.5%) | RR 2.53 (1.89 to 3.39) | 54 more per 1000 (from 31 more to 84 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTH 19 (12 to 32) |

| Dizziness reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 236/3088 (7.6%) | 38/1448 (2.6%) | RR 2.76 (1.98 to 3.84) | 46 more per 1000 (from 26 more to 75 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTH 22 (13 to 39) |

| Dysgeusia | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | seriouse | Strong associationd | 72/3088 (2.3%) | 8/1448 (0.6%) | RR 3.77 (1.85 to 7.68) | 15 more per 1000 (from 5 more to 37 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ΟMODERATE | NNTH 65 (27 to 213) |

| Dysgeusia reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | seriouse | Strong associationd | 55/3088 (1.8%) | 5/1448 (0.3%) | RR 3.65 (1.48 to 9.01) | 9 more per 1000 (from 2 more to 28 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE |

NNTH 109 (36 to 603) |

| Lethargy | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 30/3088 (1%) | 4/1448 (0.3%) | RR 2.98 (1.1 to 8.06) | 5 more per 1000 (from 0 more to 20 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH |

NNTH 183 (51 to 3620) |

| Lethargy reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 23/3088 (0.7%) | 3/1448 (0.2%) | RR 2.70 (0.93 to 7.86) | 4 more per 1000 (from 0 fewer to 14 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH |

NNTH 284 (70 to 6895) |

| Parasthesia/hypoaesthesia—nervous | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 40/3088 (1.3%) | 20/1448 (1.4%) | RR 0.93 (0.54 to 1.59) | 1 fewer per 1000 (from 6 fewer to 8 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 1034 (−123 to 157) |

| Parasthesia/hypoesthesia reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 19/3088 (0.6%) | 5/1448 (0.3%) | RR 1.49 (0.55 to 4.02) | 2 more per 1000 (from 2 fewer to 10 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE |

NNTH 591 (−96 to 644) |

| Tremors—nervous | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | seriouse | Strong associationd | 125/3088 (4%) | 10/1448 (0.7%) | RR 4.92 (2.57 to 9.39) | 27 more per 1000 (from 11 more to 58 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 37 (17 to 92) |

| Tremors reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Very seriousf | Very strong associationg | 87/3088 (2.8%) | 5/1448 (0.3%) | RR 6.67 (2.82 to 15.76) | 20 more per 1000 (from 6 more to 51 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 51 (20 to 159) |

| Psychiatric | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 586/3088 (19%) | 202/1448 (14%) | RR 1.32 (1.11 to 1.57) | 45 more per 1000 (from 15 more to 80 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 22 (13 to 65) |

| Psychiatric events reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 481/2779 (17.3%) | 129/1448 (8.9%) | RR 1.95 (1.49 to 2.56) | 85 more per 1000 (from 44 more to 139 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 12 (7 to 23) |

| Insomnia—psychiatric | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | seriousb | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 383/3088 (12.4%) | 96/1448 (6.6%) | RR 1.80 (1.23 to 2.64) | 53 more per 1000 (from 15 more to 109 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ΟΟLOW | NNTH 19 (9 to 66) |

| Insomnia reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 281/3088 (9.1%) | 74/1448 (5.1%) | RR 1.78 (1.28 to 2.47) | 40 more per 1000 (from 14 more to 75 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 25 (13 to 70) |

| Depression—psychiatric | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | seriouse | None | 57/3088 (1.8%) | 41/1448 (2.8%) | RR 0.62 (0.4 to 0.96) | 11 fewer per 1000 (from 1 fewer to 17 fewer) | ⊕ ⊕ ΟΟ LOW | NNTB 93 (59 to 883) |

| Depression reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 29/3088 (0.9%) | 20/1448 (1.4%) | RR 0.68 (0.38 to 1.2) | 4 fewer per 1000 (from 9 fewer to 3 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTB 93 (−362 to 117) |

| Cardiac | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 121/3088 (3.9%) | 36/1448 (2.5%) | RR 1.52 (0.88 to 2.62) | 13 more per 1000 (from 3 fewer to 40 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 77 (−25 to 335) |

| Cardiac defined as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 74/3088 (2.4%) | 15/1448 (1%) | RR 2.02 (1.12 to 3.63) | 11 more per 1000 (from 1 more to 27 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTH 95 (37 to 804) |

| Palpitation—cardiac | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 82/3088 (2.7%) | 15/1448 (1%) | RR 2.17 (1.2 to 3.94) | 12 more per 1000 (from 2 more to 30 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTH 83 (33 to 483) |

| Palpitation reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 37/3088 (1.2%) | 6/1448 (0.4%) | RR 2.41 (1.03 to 5.63) | 6 more per 1000 (from 0 more to 19 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH |

NNTH 171 (52 to 8044) |

| Vascular | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 277/3088 (9%) | 74/1448 (5.1%) | RR 1.77 (1.38 to 2.27) | 39 more per 1000 (from 19 more to 65 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 25 (15 to 52) |

| Vascular events reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 123/3088 (4%) | 20/1448 (1.4%) | RR 2.82 (1.77 to 4.51) | 25 more per 1000 (from 11 more to 48 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTH 40 (21 to 94) |

| Hypertension | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 72/3088 (2.3%) | 19/1448 (1.3%) | RR 1.64 (1 to 2.7) | 8 more per 1000 (from 0 more to 22 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE |

NNTH 120 (45 to 76211) |

| Hypertension reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 45/3088 (1.5%) | 12/1448 (0.8%) | RR 1.63 (0.86 to 3.09) | 5 more per 1000 (from 1 fewer to 17 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ΟMODERATE |

NNTH 192 (−58 to 862) |

| Hot flushes | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | seriouse | Strong associationd | 84/3088 (2.7%) | 10/1448 (0.7%) | RR 3.28 (1.01 to 10.61) | 16 more per 1000 (from 0 more to 66 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ΟMODERATE | NNTH 64 (15 to 14480) |

| Hot flushes reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Very seriousf | Very strong associationg | 73/3088 (2.4%) | 3/1448 (0.2%) | RR 6.70 (1.93 to 23.26) | 12 more per 1000 (from 2 more to 46 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ΟMODERATE | NNTH 85 (22 to 519) |

| Musculoskeletal | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 384/3088 (12.4%) | 211/1448 (14.6%) | RR 0.83 (0.71 to 0.96) | 25 fewer per 1000 (from 6 fewer to 42 fewer) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTB 40 (24 to 172) |

| Musculoskeletal events reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 42/3088 (1.4%) | 12/1448 (0.8%) | RR 1.38 (0.72 to 2.66) | 3 more per 1000 (from 2 fewer to 14 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ΟMODERATE |

NNTH 318 (−73 to 431) |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 1699/3088 (55%) | 398/1448 (27.5%) | RR 1.95 (1.76 to 2.17) | 261 more per 1000 (from 209 more to 322 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 4 (3 to 5) |

| Gastrointestinal events reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | seriousb | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 1405/3088 (45.5%) | 245/1448 (16.9%) | RR 2.59 (2.05 to 3.26) | 269 more per 1000 (from 178 more to 382 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 4 (3 to 6) |

| Abdominal pain | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 226/3088 (7.3%) | 55/1448 (3.8%) | RR 1.91 (1.26 to 2.91) | 35 more per 1000 (from 10 more to 73 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE |

NNTH 72 (35 to 253) |

| Abdominal pain reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 62/3088 (2%) | 10/1448 (0.7%) | RR 2.63 (1.36 to 5.06) | 11 more per 1000 (from 2 more to 28 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH |

NNTH 89 (36 to 402) |

| Dry mouth—gastrointestinal | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 249/3088 (8.1%) | 36/1448 (2.5%) | RR 3.20 (2.27 to 4.52) | 55 more per 1000 (from 32 more to 88 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH |

NNTH 18 (11 to 32) |

| Dry mouth reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 243/3088 (7.9%) | 35/1448 (2.4%) | RR 3.20 (2.26 to 4.54) | 53 more per 1000 (from 30 more to 86 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH |

NNTH 19 (12 to 33) |

| Constipation | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 569/3088 (18.4%) | 107/1448 (7.4%) | RR 2.38 (1.88 to 3.02) | 102 more per 1000 (from 65 more to 149 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH |

NNTH 10 (7 to 15) |

| Constipation reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 453/3088 (14.7%) | 78/1448 (5.4%) | RR 2.58 (1.95 to 3.41) | 85 more per 1000 (from 51 more to 130 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTH 12 (8 to 20) |

| Nausea | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 956/3088 (31%) | 97/1448 (6.7%) | RR 4.50 (3.51 to 5.78) | 234 more per 1000 (from 168 more to 320 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTH 4 (3 to 6) |

| Nausea reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Very strong associationg | 838/3088 (27.1%) | 74/1448 (5.1%) | RR 5.14 (3.84 to 6.86) | 212 more per 1000 (from 145 more to 299 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTH 5 (3 to 7) |

| Vomiting | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 301/3088 (9.7%) | 43/1448 (3%) | RR 3.17 (1.96 to 5.11) | 64 more per 1000 (from 29 more to 122 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTH 16 (8 to 35) |

| Vomiting reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Very seriousf | Very strong associationg | 199/3088 (6.4%) | 10/1448 (0.7%) | RR 7.69 (3.2 to 18.49) | 46 more per 1000 (from 15 more to 121 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 22 (8 to 66) |

| Ear and labyrinth | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 145/3088 (4.7%) | 15/1448 (1%) | RR 4.20 (2.47 to 7.13) | 33 more per 1000 (from 15 more to 64 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTH 30 (16 to 66) |

| Ear and labyrinth reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Very seriousf | Very strong associationg | 109/3088 (3.5%) | 6/1448 (0.4%) | RR 6.12 (2.75 to 13.62) | 21 more per 1000 (from 7 more to 52 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 47 (19 to 138) |

| Tinnitus | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Very seriousf | Very strong associationg | 88/3088 (2.8%) | 6/1448 (0.4%) | RR 5.48 (2.37 to 12.68) | 19 more per 1000 (from 6 more to 48 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 54 (21 to 176) |

| Tinnitus reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Very seriousf | Strong associationd | 83/3088 (2.7%) | 5/1448 (0.3%) | RR 4.86 (1.96 to 12.04) | 13 more per 1000 (from 3 more to 38 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ΟΟ LOW | NNTH 75 (25 to 302) |

| Vertigo | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associationd | 27/3088 (0.9%) | 3/1448 (0.2%) | RR 3.05 (1.07 to 8.73) | 4 more per 1000 (from 0 more to 16 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTH 235 (62 to 6895) |

| Vertigo reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Very seriousf | None | 22/3088 (0.7%) | 1/1448 (0.1%) | RR 3.45 (0.91 to 13.14) | 2 more per 1000 (from 0 fewer to 8 more) | ⊕ΟΟΟ VERY LOW | NNTH 591 (−119 to 16089) |

| General disorders | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 378/3088 (12.2%) | 139/1448 (9.6%) | RR 1.21 (0.96 to 1.53) | 20 more per 1000 (from 4 fewer to 51 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 50 (−20 to 260) |

| General disorders reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 243/3088 (7.9%) | 67/1448 (4.6%) | RR 1.64 (1.26 to 2.13) | 30 more per 1000 (from 12 more to 52 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 34 (19 to 83) |

| Fatigue | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 126/3088 (4.1%) | 39/1448 (2.7%) | RR 1.51 (0.89 to 2.54) | 14 more per 1000 (from 3 fewer to 41 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 73 (−24 to 338) |

| Fatigue reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 94/3088 (3%) | 22/1448 (1.5%) | RR 1.89 (1.19 to 3) | 14 more per 1000 (from 3 more to 30 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 74 (33 to 346) |

| Jitteryness | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousg | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | seriouse | Strong associationd | 39/3088 (1.3%) | 4/1448 (0.3%) | RR 2.87 (1.11 to 7.42) | 5 more per 1000 (from 0 more to 18 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 194 (56 to 3291) |

| Jitteryness reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | seriouse | Strong associationd | 37/3088 (1.2%) | 4/1448 (0.3%) | RR 2.67 (1.02 to 6.98) | 5 more per 1000 (from 0 more to 17 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 217 (61 to 18100) |

| Skin and subcut | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | seriousb | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 307/3088 (9.9%) | 109/1448 (7.5%) | RR 1.39 (0.88 to 2.19) | 29 more per 1000 (from 9 fewer to 90 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ΟΟ LOW | NNTH 34 (−11 to 111) |

| Skin and subcut reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 194/3088 (6.3%) | 47/1448 (3.2%) | RR 1.78 (1.21 to 2.63) | 25 more per 1000 (from 7 more to 53 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 40 (19 to 147) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 311/3088 (10.1%) | 191/1448 (13.2%) | RR 0.75 (0.63 to 0.88) | 33 fewer per 1000 (from 16 fewer to 49 fewer) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTB 30 (21 to 63) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 24/3088 (0.8%) | 8/1448 (0.6%) | RR 1.33 (0.59 to 2.99) | 2 more per 1000 (from 2 fewer to 11 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 549 (−91 to 442) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 126/3088 (4.1%) | 80/1448 (5.5%) | RR 0.75 (0.58 to 0.98) | 14 fewer per 1000 (from 1 fewer to 23 fewer) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTB 72 (43 to 905) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 50/3088 (1.6%) | 18/1448 (1.2%) | RR 1.21 (0.7 to 2.09) | 3 more per 1000 (from 4 fewer to 14 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 383 (−74 to 268) |

| Reproductive and breast disorders | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 163/3088 (5.3%) | 41/1448 (2.8%) | RR 1.69 (1.05 to 2.72) | 20 more per 1000 (from 1 more to 49 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 51 (21 to 706) |

| Reproductive and breast disorders reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 19/3088 (0.6%) | 4/1448 (0.3%) | RR 1.56 (0.56 to 4.35) | 2 more per 1000 (from 1 fewer to 9 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 646 (−108 to 823) |

Settings: Academic and primary care centres; academic medical centres; private or institutional practices; research centres

High drop‐out rates; several investigators have financial ties to the study sponsor;

moderate to severe heterogeneity;

substantial heterogeneity;

RR > 2;

wide confidence interval;

very wide confidence interval;

RR > 5.

CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat to benefit; NNTH: number needed to treat to harm; RR: risk ratio.

Figure 3.

Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of adverse events

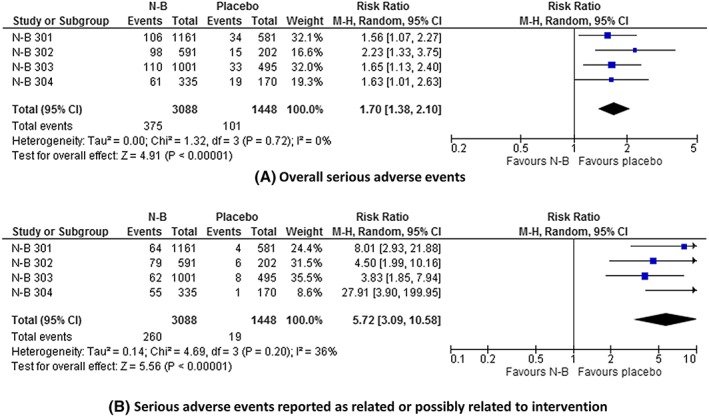

The data on serious adverse events are summarized in Table 3 and Figure 4. Serious adverse events were significantly more common with N‐B than placebo: RR = 1.70 (1.38 to 2.10); P < .00001; I 2 = 0%; GRADE = moderate; NNTH = 21 (13 to 38). The risk of serious adverse events reported by investigators as related or possibly related to intervention was significantly greater with N‐B: RR = 5.72 (3.09 to 10.58); P < .00001; I 2 = 36%; GRADE = high; NNTH = 16 (8 to 37).

Table 3.

GRADE evidence profile question 3: what is the effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of serious adverse events in overweight and obese subjects?

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Comments | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | N‐B | Placebo | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Overall rates of serious adverse events | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 375/3088 (12.1%) | 101/1448 (7%) | RR 1.70 (1.38 to 2.1) | 49 more per 1000 (from 27 more to 77 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTH 21 (13 to 38) |

| Serious (severe) adverse events reported as related or possibly related to intervention | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | seriousb | No serious imprecision | Very strong associationc | 260/3088 (8.4%) | 19/1448 (1.3%) | RR 5.72 (3.09 to 10.58) | 62 more per 1000 (from 27 more to 126 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTH 16 (8 to 37) |

Settings: Academic and primary care centres; academic medical centres; private or institutional practices; research centres

High drop‐out rates; several investigators have financial ties to the study sponsor;

wide confidence interval;

RR >5.

CI: confidence interval; NNTH: number needed to treat to harm; RR: risk ratio

Figure 4.

Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of serious adverse events

3.3. Discontinuations

Discontinuation rates were 42–47% across the 4 studies (Appendix Table 2). Overall, there were no significant differences in discontinuation rates between the N‐B and placebo groups. The data on discontinuations due to adverse events are summarized in Table 4, Figure 5 and Appendix Figures 42–47. The risk of discontinuation because of adverse events was significantly higher with N‐B: RR = 1.92 (1.65 to 2.24); P < .00001; GRADE = moderate; NNT to discontinue treatment = 9 (8 to 13). Discontinuations due to gastrointestinal adverse events, including nausea, vomiting and constipation, were significantly more common with N‐B, as were discontinuations due to nervous system events, including headaches and dizziness.

Table 4.

GRADE evidence profile question 4: what is the effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to adverse events in overweight and obese subjects?

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Comments | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | N‐B | Placebo | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Overall discontinuation | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 723/3088 (23.4%) | 175/1448 (12.1%) | RR 1.92 (1.65 to 2.24) |

111 more per 1000 (from 79 more to 150 more) |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTD 9 (8 to 13) |

| Gastrointestinal system | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | seriousb | Very strong associationc | 308/3088 (10%) |

19/1448 (1.3%) |

RR 6.11 (3.87 to 9.65) | 71 more per 1000 (from 37 more to 131 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH |

NNTD 15 (9 to 27) |

| Nausea | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Very seriousd | Very strong associationc | 181/3088 (5.9%) |

3/1448 (0.2%) |

RR 20.59 (7.65 to 55.41) | 41 more per 1000 (from 14 more to 113 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE |

NNTD 25 (9 to 73) |

| Vomiting | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Very seriousd | Very strong associationc | 31/3088 (1%) | 1/1448 (0.1%) | RR 5.69 (1.57 to 20.69) | 3 more per 1000 (from 0 more to 14 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTD 309 (74 to 2540) |

| Nervous system | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associatione | 148/3088 (4.8%) | 28/1448 (1.9%) | RR 2.47 (1.56 to 3.91) | 28 more per 1000 (from 11 more to 56 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH |

NNTD 35 (18 to 92) |

| 1.7% | 25 more per 1000 (from 10 more to 49 more) | |||||||||||

| Headache—nervous system | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong associatione | 51/3088 (1.7%) | 9/1448 (0.6%) | RR 2.47 (1.23 to 4.95) | 9 more per 1000 (from 1 more to 25 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ HIGH | NNTD 109 (41 to 700) |

| 0.6% | 9 more per 1000 (from 1 more to 24 more) | |||||||||||

| Dizziness | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | seriousb | Strong associatione | 36/3088 (1.2%) | 5/1448 (0.3%) | RR 3.01 (1.22 to 7.47) | 7 more per 1000 (from 1 more to 22 more) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕Ο MODERATE | NNTD 144 (45 to 1316) |

| 0.4% | 8 more per 1000 (from 1 more to 26 more) | |||||||||||

Settings: Academic and primary care centres; academic medical centres; private or institutional practices; research centres

High drop‐out rates; several investigators have financial ties to the study sponsor;

wide confidence interval;

RR > 5;

very wide confidence interval;

RR > 2.

CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio

Figure 5.

Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to adverse events

Among participants in whom adverse events were reported as related or possibly related to the intervention (n = 1979), the frequency of investigator‐initiated drug withdrawals was significantly higher with N‐B: RR = 1.79 (1.53 to 2.11, I2 = 0%, P < .00001), NNT for drug withdrawal = 5 (4 to 8; Appendix Figure 48).

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Summary of main findings

N‐B caused a significantly greater reduction in weight than placebo when estimated by the number of participants who lost at least 5% of their body weight. Overall, this translates to 2.5 kg more weight loss than with placebo over a 12‐month period. A significantly greater proportion of participants who took N‐B also achieved at least 10% weight loss in body weight from baseline compared with placebo. N‐B had significantly beneficial effects on other markers of cardiovascular risk; however, the true extent of the effects is unclear because of incomplete outcomes data. N‐B significantly increased the risk of adverse events, including abdominal pain, vomiting, constipation, dry mouth, headaches, tinnitus, vertigo, dysgeusia, insomnia, tremors, palpitations and hot flushes. N‐B significantly increased the risk of serious adverse events and discontinuation due to adverse events. N‐B also significantly increased the risk of investigator‐initiated drug withdrawals because of adverse events. That the overall discontinuations rates were similar between N‐B and placebo despite significantly greater withdrawals with N‐B could be due to more withdrawals in placebo group because of failure to lose weight. The meta‐analysis results (along with the associated NNTs) should be interpreted with caution because of heterogeneity in some of the analyses. The substantial heterogeneity observed with body weight outcomes is probably due to variation in baseline demographics across the 4 trials.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of the benefits and harms of N‐B using evidence from CSRs. For the first time, we have also reported data on harms adjudged by trial investigators to be related or possibly related to the intervention.

4.2. Comparison with existing literature

Our results are partly consistent with those of 3 previous reviews that assessed the benefits and harms of N‐B using data from journal publications of clinical trials22, 23, 24; all 3 reviews concluded that N‐B has significant beneficial effects on body weight but also significantly increases the risk of harms.

However, the availability of CSRs enabled us to access and analyse data that were not accounted for in those reviews and makes our review the most comprehensive to date. We assessed the protocol and trials for internal consistency in the trial regimen by evaluating data on protocol amendments and changes to statistical analysis plans. We computed the data on weight loss outcomes using the ITT analysis comprising the most complete sets of randomized subjects, i.e. including all randomized participants. For example, the effect size for the proportion of participants who lost >5% in body weight in our review was smaller than those reported in the 3 previous reviews.

Although the aggregated data on other cardiovascular risk outcomes were incomplete, we were able to report the data based on the proportion of randomized participants for whom outcomes were reported across the trials. We reported data on adverse events by system and reported data on individual adverse events. We also extracted and analysed data on harms outcomes classified by trial investigators as related or possibly related to interventions. Furthermore, we evaluated data on investigator‐initiated drug withdrawals because of adverse events.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

We obtained data on full unabridged CSRs from the EMA. We assessed the consistency of reporting between the protocols and the core reports. We rated the quality of the evidence of each outcome. We reported body weight outcome in both binary and continuous data. We also reported outcomes on other cardiovascular parameters. For the first time, we have reported data and rated the quality of the evidence for harms outcomes reported by investigators as related or possibly related to the interventions; this included investigator‐initiated drug withdrawals because of adverse events.

However, we recognize some limitations. The high degree of heterogeneity observed for body weight outcomes limits the accuracy of our effect estimates. We were unable to conduct sensitivity or subgroup analyses because of the small number of included studies; however, the studies had large sample sizes and heterogeneity was low in most of the harms outcomes. Despite obtaining unabridged CSRs, we are limited by incomplete data, especially for cardiovascular outcomes. We did not have access to patient‐level data, including individual case report forms, which would have allowed better evaluation of harms. The extent to which the protocol amendments influenced the reported effect sizes is unclear25; in all cases, the trial protocols were amended—these involved changes in inclusion/exclusion criteria in 3 trials (see Appendix 4). The extensive exclusion criteria used in all 4 studies limit the applicability of review findings (see Appendix 5)—many patients in clinical practice would not be eligible for treatment given the extensive categories of exclusions. Our definitions for ITT analysis differed from the definitions used in the CSRs; however, we used data from the CSRs that corresponded to our a priori definitions: i.e. ITT corresponding to baseline‐observation‐carried‐forward populations in the CSRs.

4.4. Implications for research

Sustained weight losses of 5–10% can produce cardiovascular benefits26; however, the evidence from the included CSRs was insufficient to demonstrate such benefits. Although we found significant beneficial effects for some cardiovascular profiles, these were based on incomplete outcomes data. In the protocols, the investigators specified that they would measure these outcomes at baseline and at endpoint. While body weight outcomes were fully reported, the data on other cardiovascular measures were incomplete. Future trials could incorporate targeted study designs aimed at identifying what groups of overweight or obese subjects will benefit the most from N‐B; for example, those with low risks of cardiovascular or psychiatric adverse events who are struggling to lose weight through dietary or lifestyle modifications.

Improved precision in harms reporting could be achieved if researchers compared the rates of harms for both the overall data and data reported as related or possibly related to the new medicine, as we have done in this review. Such methods could increase the certainty with which we predict the risks of harms from new medicines, especially when integrated with data from real‐life practice. Although the current package insert for N‐B recommends discontinuation of therapy after 12 weeks of maintenance27 if there is no reduction of at least 5% in body weight, discontinuation also ought to be considered in the context of any harms experienced.

Postmarketing studies of N‐B have not provided robust evidence about its benefit–harm profile, because of premature termination28, 29 and a failure of scheduled trials to start owing to disputes between drug sponsors.30, 31 More recently (April 2018), the original sponsor announced that they have entered into an agreement to sell the company, and they have also reached an agreement with the FDA to conduct a new cardiovascular outcomes trial.32 That there are no completed postmarketing trials 4 years after initial granting of marketing licences for N‐B indicates failure on the part of drug regulators to robustly enforce guidelines on postmarketing drug assessment, a lack of commitment by the drug sponsors to conduct (and transparently report) postauthorization studies, or a combination of the 2. Positive collaborations across stakeholders aimed at removing the uncertainties around the clinical effectiveness of N‐B should be encouraged.

4.5. Implications for practice and policy

Physicians should weigh the potential benefits and harms when prescribing N‐B, especially in patients with a history of (or risk factors for) nervous or psychiatric disorders. Caution should also be exercised when considering prescriptions in patients with a history of insomnia, hypertension, or hot flushes. The intensity of the adverse events associated with the use of N‐B could result in premature discontinuation of the drug. The long‐term benefits and harms of N‐B are unknown; it is unclear whether any weight reductions generated through use of N‐B is sustained over longer periods. Because of the low proportion of participants with BMI <30 kg/m2 across the trials (<3%), N‐B should not be prescribed as first‐line weight loss agent to overweight individuals. Regulators should be aware that they did not have access to full ITT analyses when considering N‐B for licensing. In addition, it is unclear whether N‐B will be cost‐effective compared with alternatives. According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence,6 the economic model presented by the drug manufacturer did not take into account episodes of retreatment, which are likely with use of the drug. A more recent evaluation in 2018 by the Irish National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics did not recommend N‐B for reimbursement, because of uncertainties around its cardiovascular safety and cost‐effectiveness.33 Until there is sufficient evidence of the clinical and cost‐effectiveness of N‐B (including cardiovascular benefits), regulators should be circumspect about approving its use in the general population.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The evidence from CSRs of pivotal trials shows that N‐B causes significant but small reductions in body weight compared with placebo. N‐B also appears to have small beneficial effects on other markers of cardiovascular risk; however, the extent is unclear because of incomplete outcome data. N‐B significantly increases the risk of adverse events, serious adverse events, and discontinuations due to adverse events. Postmarketing studies assessing its benefits and harms are urgently required.

COMPETING INTERESTS

I.J.O., J.JL., K.R.M. and C.J.H. report funding from the National Institute of Health Research, School for Primary Care Research (NIHR‐SPCR) as part of the Evidence Synthesis Working Group (ESWG Project No: 390) to conduct independent research, including systematic reviews. C.J.H. has received expenses from the World Health Organization, FDA, and holds grant funding from the NIHR, the NIHR School of Primary Care Research, The Wellcome Trust and the World Health Organization. He has received financial remuneration from an asbestos case. He has also received income from the publication of a series of toolkit books published by Blackwells. On occasion, he receives expenses for teaching evidence‐based medicine and is also paid for his GP work in NHS out of hours. The Centre for Evidence‐Based Medicine jointly runs the EvidenceLive Conference with the BMJ and the Overdiagnosis Conference with some international partners which are based on a non‐profit making model. J.K.A. has written and edited articles and textbooks on adverse drug reactions, including Meyler's Side Effects of Drugs (16th edition, 2016), its companion volumes the Side Effects of Drugs Annuals, and Stephens' Detection and Evaluation of Adverse Drug Reactions (6th edition, 2011). He is an Associate Editor of BMJ Evidence‐Based Medicine and a member of the Centre for Evidence‐Based Medicine (see above). J.J.L. has no interests to disclose.

CONTRIBUTORS

I.J.O. was involved in protocol development, electronic searches, requesting and obtaining of clinical study reports, quality assessment, data extraction, data analysis and interpretation, and co‐drafting of the review. J.J.L. was involved in quality assessment, data extraction, data analysis and interpretation, and co‐drafting of the review. K.R.M. was involved in protocol development, data interpretation and co‐drafting of the review. J.K.A. was involved in protocol development, data analysis and interpretation, and co‐drafting of the review. C.J.H. was involved in protocol development, data analysis and interpretation, and co‐drafting of the review.

Supporting information

FIGURE S1 Timeline showing process for obtaining full clinical study reports of Mysimba from the European Medicines Agency

FIGURE S2 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the proportion of participants who achieved ≥10% weight loss

FIGURE S3 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on body weight (kg)

FIGURE S4 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on waist circumference (cm)*

FIGURE S5 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on systolic blood pressure (mmHg)*

FIGURE S6 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on diastolic blood pressure (mmHg)*

FIGURE S7 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on fasting triglycerides (mg/dL)*

FIGURE S8 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on fasting total cholesterol (mg/dL)*

FIGURE S9 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on fasting high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL)*

FIGURE S10 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on fasting low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL)*

FIGURE S11 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on fasting blood glucose (mg/dL)*

FIGURE S12 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on Impact of Weight on Quality of Life* total score**

FIGURE S13 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of nervous system adverse events

FIGURE S13 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of nervous system adverse events

FIGURE S14 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of headaches

FIGURE S15 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of dizziness

FIGURE S16 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of dysgeusia

FIGURE S17 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of lethargy

FIGURE S18 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of tremors

FIGURE S19 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of psychiatric system adverse events

FIGURE S20 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of insomnia

FIGURE S21 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of depression

FIGURE S22 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of cardiac system adverse events

FIGURE S23 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of palpitations

FIGURE S24 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of vascular system adverse events

FIGURE S25 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of hypertension

FIGURE S26 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of hot flushes

FIGURE S27 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of gastrointestinal system adverse events

FIGURE S28 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of abdominal pain

FIGURE S29 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of dry mouth

FIGURE S30 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of diarrhoea

FIGURE S31 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of constipation

FIGURE S32 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of nausea

FIGURE S33 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of vomiting

FIGURE S34 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of ear and labyrinth system adverse events

FIGURE S35 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of tinnitus

FIGURE S36 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of vertigo

FIGURE S37 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of general disorders

FIGURE S38 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of fatigue

FIGURE S39 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of jitteriness

FIGURE S40 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of skin and subcutaneous tissue adverse events

FIGURE S41 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of reproductive and breast disorders

FIGURE S42 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to gastrointestinal adverse events

FIGURE S43 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to nausea

FIGURE S44 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to vomiting

FIGURE S45 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to nervous system adverse events

FIGURE S46 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to headaches

FIGURE S47 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to dizziness

FIGURE S48 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of investigator‐initiated drug withdrawals in participants with adverse events reported as related or possibly related to intervention

E‐APPENDIX 1 Links to regulatory documents used for assessing information on pivotal trials of naltrexone–bupropion

E‐APPENDIX 2 Flow chart showing the process for identification of pivotal clinical trials naltrexone–bupropion (Mysimba).

E‐APPENDIX 3 List of component items of clinical study reports in pivotal trials of Mysimba received from the European Medicines Agency

E‐APPENDIX 4 Notable protocol amendments and changes to planned statistical analyses

E‐APPENDIX 5 Summary of list of exclusion criteria in pivotal trials assessing the benefit and harms in pivotal trials of Mysimba

E‐APPENDIX TABLE 1 Identification matching for pivotal clinical trials of Mysimba.

E‐APPENDIX TABLE 2 Key characteristics of pivotal clinical trials of Mysimba

E‐APPENDIX TABLE 3 Data on continuous outcomes on cardiovascular risk for which there was incomplete reporting of aggregated data for randomized subjects in clinical study reports of pivotal clinical trials of Mysimba (full analysis set*)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Professor Rafael Perera, University of Oxford, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences for statistical advice. This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research (NIHR‐SPCR; Project No: 390) as part of the Evidence Synthesis Working Group (ESWG) collaboration. The views expressed in this review represent the views of the authors and not necessarily those of the host institution, the NHS, the NIHR or the UK Department of Health.

Onakpoya IJ, Lee JJ, Mahtani KR, Aronson JK, Heneghan CJ. Naltrexone–bupropion (Mysimba) in management of obesity: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of unpublished clinical study reports. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86:646–667. 10.1111/bcp.14210

REFERENCES

- 1. Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980‐2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2014. Aug 30;384(9945):766‐781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . Obesity and overweight. Key facts. 16 February 2018. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight [Accessed 12 February 2019]

- 3. Moodie M, Sheppard L, Sacks G, Keating C, Flego A. Cost‐effectiveness of fiscal policies to prevent obesity. Curr Obes Rep. 2013. Jun 28;2:211‐224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Onakpoya IJ, Heneghan CJ, Aronson JK. Post‐marketing withdrawal of anti‐obesity medicinal products because of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang GJ, Tomasi D, Volkow ND, et al. Effect of combined naltrexone and bupropion therapy on the brain's reactivity to food cues. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38(5):682‐688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Final appraisal determination. Naltrexone–bupropion for managing overweight and obesity. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-tag486/documents/final-appraisal-determination-document [Accessed 3 October 2017]

- 7. International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human use . ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports E3. Current Step 4 version. 30 November 1995. Available at: http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E3/E3_Guideline.pdf [Accessed 3 October 2017]

- 8. Golder S, Loke YK, Wright K, Norman G. Reporting of adverse events in published and unpublished studies of health care interventions: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2016;13(9):e1002127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hodkinson A, Gamble C, Smith CT. Reporting of harms outcomes: a comparison of journal publications with unpublished clinical study reports of orlistat trials. Trials. 2016;17(1):207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011. Oct 18;343(oct18 2):d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews . How to include multiple groups from one study. Chapter 16 (Section 5.4). http://handbook.cochrane.org/chapter_16/16_5_4_how_to_include_multiple_groups_from_one_study.htm [Accessed 20 June 2017]

- 12. Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program] . Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

- 13. GRADE Working Group . Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. GRADEpro . Computer program on www.gradepro.org. Version 3.6. McMaster University, 2014.

- 15. Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Plodkowski RA, et al. Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR‐I): a multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010. Aug 21;376(9741):595‐605. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60888-4 Epub 2010 Jul 29. Erratum in: Lancet 2010 Aug 21;376(9741):594. Lancet. 2010 Oct 23;376(9750):1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wadden TA, Foreyt JP, Foster GD, et al. Weight loss with naltrexone SR/bupropion SR combination therapy as an adjunct to behavior modification: the COR‐BMOD trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011. Jan;19(1):110‐120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Apovian CM, Aronne L, Rubino D, et al. A randomized, phase 3 trial of naltrexone SR/bupropion SR on weight and obesity‐related risk factors (COR‐II). Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013. May;21(5):935‐943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hollander P, Gupta AK, Plodkowski R, et al. Effects of naltrexone sustained‐release/bupropion sustained‐release combination therapy on body weight and glycemic parameters in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013. Dec;36(12):4022‐4029. Epub 2013 Oct 21. Erratum in: Diabetes Care 2014 Feb;37(2):587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rochon PA, Sekeres M, Hoey J, et al. Investigator experiences with financial conflicts of interest in clinical trials. Trials. 2011. Jan 12;12:9 10.1186/1745-6215-12-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, Wetterslev J, Winkel P. When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials – a practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. White IR, Carpenter J, Horton NJ. Including all individuals is not enough: lessons for intention‐to‐treat analysis. Clin Trials. 2012;9(4):396‐407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khera R, Murad MH, Chandar AK, et al. Association of pharmacological treatments for obesity with weight loss and adverse events: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2424‐2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Onakpoya IJ, Collins DRJ, Bobrovitz NJH, Aronson JK, Heneghan CJ. Benefits and harms in pivotal trials of oral centrally acting antiobesity medicines: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018. Mar;26(3):513‐521. Epub 2018 Feb 5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. LeBlanc EL, Patnode CD, Webber EM, Redmond N, Rushkin M, O'Connor EA. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2018 Sep. Report No.: 18‐05239‐EF‐1. Behavioral and Pharmacotherapy Weight Loss Interventions to Prevent Obesity‐Related Morbidity and Mortality in Adults: An Updated Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532379/ [Accessed 29 November 2019] [PubMed]

- 25. Lösch C, Neuhäuser M. The statistical analysis of a clinical trial when a protocol amendment changed the inclusion criteria. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):16 10.1186/1471-2288-8-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brown JD, Buscemi J, Milsom V, Malcolm R, O'Neil PM. Effects on cardiovascular risk factors of weight losses limited to 5–10%. Transl Behav Med. 2016. Sep;6(3):339‐346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Contrave® . Full Prescribing Information. Available at: https://contravehcp.com/wp-content/uploads/member-content/Contrave_PI_MedGuide.pdf [Accessed 8 September 2019]

- 28. Nissen SE, Wolski KE, Prcela L, et al. Effect of naltrexone–bupropion on major adverse cardiovascular events in overweight and obese patients with cardiovascular risk factors: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016. Mar 8;315(10):990‐1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Naltrexone/Bupropion Cardiovascular Outcomes Study . http://ClinicalTrials.gov website. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT02638129?term=NCT02638129&rank=1. Updated 27 February 2017. 20 November 2018.

- 30. Sherman MM, Ungureanu S, Rey JA. Naltrexone/bupropion ER (Contrave): newly approved treatment option for chronic weight management in obese adults. P t. 2016. Mar;41(3):164‐172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. US Securities and Exchange Commission . Form 8K [filed by Orexigen Therapeutics Inc]. March 3, 2015. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1382911/000119312515074251/d882841d8k.htm. [Accessed 20 November 2018]

- 32. Orexigen . Press Release. Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc. Enters Agreement for Sale of Company. http://ir.orexigen.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=207034&p=irol-newsArticle [Accessed 23 November 2018]

- 33. National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics NCPE Ireland . Naltrexone/bupropion (Mysimba®). http://www.ncpe.ie/drugs/naltrexone-bupropion-mysimba/ [Accessed 20 November 2019]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIGURE S1 Timeline showing process for obtaining full clinical study reports of Mysimba from the European Medicines Agency

FIGURE S2 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the proportion of participants who achieved ≥10% weight loss

FIGURE S3 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on body weight (kg)

FIGURE S4 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on waist circumference (cm)*

FIGURE S5 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on systolic blood pressure (mmHg)*

FIGURE S6 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on diastolic blood pressure (mmHg)*

FIGURE S7 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on fasting triglycerides (mg/dL)*

FIGURE S8 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on fasting total cholesterol (mg/dL)*

FIGURE S9 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on fasting high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL)*

FIGURE S10 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on fasting low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL)*

FIGURE S11 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on fasting blood glucose (mg/dL)*

FIGURE S12 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on Impact of Weight on Quality of Life* total score**

FIGURE S13 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of nervous system adverse events

FIGURE S13 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of nervous system adverse events

FIGURE S14 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of headaches

FIGURE S15 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of dizziness

FIGURE S16 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of dysgeusia

FIGURE S17 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of lethargy

FIGURE S18 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of tremors

FIGURE S19 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of psychiatric system adverse events

FIGURE S20 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of insomnia

FIGURE S21 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of depression

FIGURE S22 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of cardiac system adverse events

FIGURE S23 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of palpitations

FIGURE S24 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of vascular system adverse events

FIGURE S25 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of hypertension

FIGURE S26 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of hot flushes

FIGURE S27 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of gastrointestinal system adverse events

FIGURE S28 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of abdominal pain

FIGURE S29 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of dry mouth

FIGURE S30 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of diarrhoea

FIGURE S31 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of constipation

FIGURE S32 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of nausea

FIGURE S33 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of vomiting

FIGURE S34 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of ear and labyrinth system adverse events

FIGURE S35 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of tinnitus

FIGURE S36 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of vertigo

FIGURE S37 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of general disorders

FIGURE S38 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of fatigue

FIGURE S39 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of jitteriness

FIGURE S40 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of skin and subcutaneous tissue adverse events

FIGURE S41 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of reproductive and breast disorders

FIGURE S42 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to gastrointestinal adverse events

FIGURE S43 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to nausea

FIGURE S44 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to vomiting

FIGURE S45 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to nervous system adverse events

FIGURE S46 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to headaches

FIGURE S47 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of discontinuation due to dizziness

FIGURE S48 Effect of naltrexone–bupropion (N‐B) on the frequency of investigator‐initiated drug withdrawals in participants with adverse events reported as related or possibly related to intervention

E‐APPENDIX 1 Links to regulatory documents used for assessing information on pivotal trials of naltrexone–bupropion

E‐APPENDIX 2 Flow chart showing the process for identification of pivotal clinical trials naltrexone–bupropion (Mysimba).

E‐APPENDIX 3 List of component items of clinical study reports in pivotal trials of Mysimba received from the European Medicines Agency

E‐APPENDIX 4 Notable protocol amendments and changes to planned statistical analyses

E‐APPENDIX 5 Summary of list of exclusion criteria in pivotal trials assessing the benefit and harms in pivotal trials of Mysimba

E‐APPENDIX TABLE 1 Identification matching for pivotal clinical trials of Mysimba.

E‐APPENDIX TABLE 2 Key characteristics of pivotal clinical trials of Mysimba

E‐APPENDIX TABLE 3 Data on continuous outcomes on cardiovascular risk for which there was incomplete reporting of aggregated data for randomized subjects in clinical study reports of pivotal clinical trials of Mysimba (full analysis set*)