Abstract

Background

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the major cause of early morbidity and mortality in most developed countries. Secondary prevention aims to prevent repeat cardiac events and death in people with established CHD. Lifestyle modifications play an important role in secondary prevention. Yoga has been regarded as a type of physical activity as well as a stress management strategy. Growing evidence suggests the beneficial effects of yoga on various ailments.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of yoga for the secondary prevention of mortality and morbidity in, and on the health‐related quality of life of, individuals with CHD.

Search methods

This is an update of a review previously published in 2012. For this updated review, we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (Issue 1 of 12, 2014), MEDLINE (1948 to February week 1 2014), EMBASE (1980 to 2014 week 6), Web of Science (Thomson Reuters, 1970 to 12 February 2014), China Journal Net (1994 to May 2014), WanFang Data (1990 to May 2014), and Index to Chinese Periodicals of Hong Kong (HKInChiP) (from 1980). Ongoing studies were identified in the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (May 2014) and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (May 2014). We applied no language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We planned to include randomised controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the influence of yoga practice on CHD outcomes in men and women (aged 18 years and over) with a diagnosis of acute or chronic CHD. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they had a follow‐up duration of six months or more. We considered studies that compared one group practicing a type of yoga with a control group receiving either no intervention or interventions other than yoga.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected studies according to prespecified inclusion criteria. We resolved disagreements either by consensus or by discussion with a third author.

Main results

We found no eligible RCTs that met the inclusion criteria of the review and thus we were unable to perform a meta‐analysis.

Authors' conclusions

The effectiveness of yoga for secondary prevention in CHD remains uncertain. Large RCTs of high quality are needed.

Keywords: Humans, Yoga, Coronary Artery Disease, Coronary Artery Disease/prevention & control, Secondary Prevention, Secondary Prevention/methods

Plain language summary

Yoga for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a major cause of early cardiovascular‐related illness and death in most developed countries. Secondary prevention is a term used to describe interventions that aim to prevent repeat cardiac events and death in people with established CHD. Individuals with CHD are at the highest risk of coronary events and death. Lifestyle modifications play an important role in secondary prevention. Yoga has been regarded as both a type of physical activity and a stress management strategy. The physical and psychological benefits of yoga are well accepted, yet inappropriate practice of yoga may lead to musculoskeletal injuries, such as muscle soreness and strain. The aim of this systematic review was to determine the effectiveness of yoga for secondary prevention in CHD in terms of cardiac events, death, and health‐related quality of life. We found no randomised controlled trials which met the inclusion criteria for this review. Therefore, the effectiveness of yoga for secondary prevention in CHD remains uncertain. High‐quality randomised controlled trials are needed.

This is an update of a review previously published in 2012.

Background

Description of the condition

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), including coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke, remains a major cause of early morbidity and mortality in most developed countries, and is one of the major non‐communicable diseases burdening healthcare systems and causing great socioeconomic harm within all countries (Hobbs 2004; USHHS 1996; WHO 2011a). CVD is the world's largest killer; an estimated 17.3 million people died from CVD in 2008, representing 30% of all global deaths. Of these deaths, an estimated 7.3 million were due to CHD (WHO 2011b).

Numerous risk factors for CVD have been identified, including hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, hyperglycaemia, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, tobacco use, harmful use of alcohol, obesity, and psychosocial stress (Hobbs 2004; Rozanski 2005; WHO 2011b). These behavioural risk factors are responsible for about 80% of all cases of CHD and cerebrovascular disease (WHO 2011b). Moreover, psychosocial stress induces adverse changes in autonomic tone accounting for significant but modifiable cardiovascular risks (Larzelere 2008; O'Keefe 2009; WHO 2011b); it also adversely affects recovery after major CHD events (Lavie 2009; Rozanski 2005). The INTERHEART study assessed the importance of risk factors for CHD (Yusuf 2004). Psychosocial stress accounted for 28.8% (99% confidence interval (CI) 22.6 to 35.8) of the population's attributable risk for acute myocardial infarction; comparable to that for risk factors such as hypertension and smoking.

People with established CHD are at the highest risk of coronary events and death, yet effective secondary prevention can reduce their risk of repeat events or death (Hobbs 2004; Lindholm 2007; Murchie 2003). Evidence‐based guidance for the secondary prevention of CHD includes the use of pharmaceutical interventions (for example aspirin, antiplatelet agents, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, statins, and ß‐blockers), surgical revascularisation (for example coronary artery bypass grafting, percutaneous coronary intervention), and lifestyle modifications (for example dietary modification, physical activity, smoking cessation, stress management) (AHA 2011a; Hall 2010; Leon 2005; Murchie 2003; O'Keefe 2009; Schnell 2012; Smith 2011; WHO 2007; Williams 2002). Since yoga is a lifestyle modification that involves both physical activity and stress management it may have beneficial effects on CHD (Frishman 2005).

Description of the intervention

Yoga originated from India more than 5000 years ago. Its principle is to achieve the integration and balance of body, mind, and spirit (Barnes 2008; Kappmeier 2006). The three basic components, namely 'Asana' (posture), 'Pranayama' (breathing), and 'Dhyana' (meditation), are integrated with one another (Riley 2004). Practicing yoga postures improves flexibility and strength in a controlled fashion. Controlled breathing helps the mind to focus and is an important component of relaxation, a modulator of autonomic nervous system function. Meditation aims to calm the mind. Due to the long history of yoga, opinions among scholars differ as to the classification of the various systems of yoga. Hatha yoga is the most widely practiced yoga system in the West (Hewitt 2001). Hatha yoga is the physical aspect of yoga and includes the aforementioned Asana and Pranayama (Hewitt 2001; Yoga Alliance 2015). Yoga can be practiced and taught in various styles such as Ananda, Ashtanga, Bikram, Iyengar, Integral, Kripalu, Kundalini, Power, Sivananda, and Vinyasa, and each style has unique characteristics (Yoga Alliance 2015).

Yoga is increasingly popular as a form of recreation or physical activity, and the physical and psychological benefits of yoga are well accepted (Saper 2004). A growing body of evidence has demonstrated that yoga has positive influences on various conditions. For example, yoga has been found to manage and reduce the symptoms of urological disorders (Ripoll 2002), pulmonary tuberculosis (Visweswaraiah 2004), osteoarthritis (Bukowski 2007), and menopause (Booth‐LaForce 2007); and to have physical benefits, with decreased distress and relief of perceived pain, in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis (Bosch 2009), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Donesky‐Curenco 2009), and chronic back pain (Groessl 2008; Tekur 2008). Evidence also suggests that yoga has beneficial effects on various psychological states in different populations, such as the mood state in individuals undergoing inpatient psychiatric treatment (Lavey 2005); symptoms of depression, trait anxiety, negative mood, and fatigue in mildly depressed young adults (Woolery 2004); stress and psychological outcomes in women suffering from mental distress (Michalsen 2005); and sleep quality in a chronic insomnia population. Furthermore, there is increasing research interest in examining yoga interventions in healthy seniors and those with cancer. Existing findings demonstrate that yoga helps improve physical fitness and quality of life in older adults (Chen 2008; Oken 2006). Yoga may also help improve sleep quality, mood, stress, and quality of life, and reduce fatigue in individuals with cancer (Culos‐Reed 2006; DiStasio 2008; Vadiraja 2009).

How the intervention might work

A high level of physical activity plays a major role in preventing obesity, diabetes mellitus, and CVD (Mendelson 2008; Mittal 2008). Regular physical activity decreases the risk of CVD mortality in general and CHD mortality in particular (O'Keefe 2009; USHHS 1996). It is beneficial to include exercise in the treatment of individuals with CVD as exercise has favourable effects on CVD risk factors, symptoms, functional capacity, physiology, and quality of life (ACSM 2010; AHA 2011b; Leon 2005). A previous Cochrane review examined the effectiveness of exercise‐based cardiac rehabilitation in individuals with CHD; the results suggested that medium‐to‐longer‐term (that is 12 or more months of follow up) exercise‐based rehabilitation reduced overall mortality (relative risk (RR) 0.85, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.99) and cardiovascular mortality (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.87) (Heran 2011). Yoga is a relatively safe and gentle physical activity for promoting general health and a state of emotional well‐being in sedentary individuals who have special health concerns, such as established CVD, obesity, and musculoskeletal problems, that can limit their mobility and tolerance to highly demanding physical exercises. An individual may experience different kinds and degrees of physical health benefits and improvements in functional capacity depending on how they practice yoga. For example, if the individual practices a single yogic posture separately, improvements in muscular strength, flexibility, and posture may be achieved, whereas improved cardiorespiratory fitness may be found when the individual practices poses continuously and intensively. Thus, the effectiveness of yoga on health‐related physical fitness components, especially cardiorespiratory endurance, remains questionable. In an observational study involving 20 intermediate‐to‐advanced level yoga practitioners, Hagins 2007 found that the metabolic costs of Hatha yoga averaged across the entire session represented a low level of physical activity (equivalent to, for example, walking on a treadmill at 3.2 km/hour). This level does not meet the recommended physical activity level required for improving or maintaining health or cardiovascular fitness; however, incorporating sun salutation (a sequence of yogi postures) and exceeding the minimum bout of 10 minutes may contribute some portions of an adequately intense physical activity to improve cardiorespiratory fitness in unfit or sedentary individuals. Moreover, the results of a study in older men with established CHD suggested that light and moderate levels of physical activities (for example walking, gardening, and recreational activity) were associated with significant reductions in the risk of all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality rates (Wannamethee 2000). Therefore, yoga can help sedentary individuals with CHD become more physically active in a comparatively gentle and all‐round fashion.

Yoga is not only a physical activity but also a stress management strategy. Exercise training has been associated with a reduction in psychosocial stress (O'Keefe 2009), whereas stress management strategies can improve subjective and objective measures of psychosocial stress (AHA 2011b; Larzelere 2008; O'Keefe 2009). A previous Cochrane review determined the effects of psychological interventions in individuals with CHD, suggesting that psychological interventions produced a modest positive effect in the reduction of cardiac mortality (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.00) (Whalley 2011). The potential mechanisms of yoga‐induced physiopsychological changes include reducing the activation and reactivity of the sympathoadrenal system and the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis (Innes 2007), and counteracting the aroused autonomic nervous system activity, reversing it back to the relaxed state (Levine 2000; Michalsen 2005). A growing body of research has explored yoga‐induced changes, including significantly decreased cortisol levels (Bosch 2009; Michalsen 2005; Vadiraja 2009; West 2004), improved sympathetic and parasympathetic reactivity with Pranayama practice in individuals with hypertension (Mourya 2009), and reduced stress and an improved adaptive autonomic response to stress in healthy pregnant women (Satyapriya 2009). Furthermore, significant reductions in noradrenaline and self‐rated stress and stress behaviour were found in a randomised controlled study (RCT) that investigated the effects of yoga in healthy individuals (Granath 2006).

Adverse effects

Potential adverse effects have to be considered. The major adverse effects of physical activities such as yoga include musculoskeletal injuries (Jayasinghe 2004; USHHS 1996): injuries may be due to overtraining, overuse of the muscles, and incorrect movements. The most common injuries found when practicing yoga include: strains resulting from falls when executing balancing poses; muscle or tendon tears due to overstretching muscles when executing stretching poses; and muscle soreness, muscle stiffness, and even bone fractures caused by spinal misalignment when performing weight‐bearing poses repeatedly and incorrectly. Even though regular physical activity improves cardiorespiratory fitness, it can also increase the risk of serious cardiac events (e.g. sudden death) in sedentary individuals who suddenly exercise vigorously (USHHS 1996). Yoga can be considered a safe form of physical activity if practiced under the guidance and supervision of qualified instructors (Jayasinghe 2004).

Why it is important to do this review

To the best of our knowledge, few RCTs have determined the effectiveness of yoga for secondary prevention in CHD. Two existing reviews examined the efficacy and related risks of yoga in the primary and secondary prevention of CVD (Innes 2005; Jayasinghe 2004), but they included studies regardless of type. A more recent Cochrane systematic review included RCTs only, but focused on the effects of yoga for the primary prevention of CVD (Hartley 2014). An exhaustive systematic review is therefore needed to assess the randomised evidence available to determine whether yoga is an effective way of reducing mortality and morbidity and improving quality of life in individuals with CHD. This is an update of a previously published Cochrane review (Lau 2012); it is vital to ensure that evidence is regularly updated to provide the latest insights in current research and practice.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of yoga for the secondary prevention of mortality and morbidity in, and on the health‐related quality of life of, individuals with CHD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs investigating the influence of yoga in individuals with CHD. The length of follow up had to be six months or more for the trial to be eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

Men and women aged 18 years and over with a diagnosis of acute or chronic CHD (acute or previous myocardial infarction, stable or unstable angina) according to the definitions used in individual studies and irrespective of setting.

Types of interventions

Any type of yoga compared with no intervention or an intervention other than yoga. We excluded multifactorial intervention trials (including other kinds of stress management strategies and physical activities) from this review to avoid confounding.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality

Cardiovascular mortality

Composite cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, unstable angina pectoris, resuscitated cardiac arrest, stroke, and cardiac revascularisation procedures)

Cardiovascular‐related hospital admissions

Adverse effects

Secondary outcomes

Health‐related quality of life

Costs

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (Issue 1 of 12, 2014), MEDLINE (1948 to February week 1 2014), EMBASE (1980 to 2014 week 6), Web of Science (1970 to 12 February 2014), China Journal Net (CJN) (1994 to May 2014), WanFang Data (1990 to May 2014), and Index to Chinese Periodicals of Hong Kong (HKInChiP) (from 1980). We used the Cochrane sensitivity‐maximising RCT filters in our MEDLINE and EMBASE searches (Lefebvre 2011), and adapted these filters for use in other databases, where appropriate. We last searched the electronic databases on 13 February 2014, with the exception of CJN, WanFang Data, and HKInChiP, which we last searched on 19 May 2014. See Appendix 1 for details of search strategies.

We applied no language or publication status restrictions.

Searching other resources

We contacted the authors of ongoing or unpublished studies for further information. We also contacted known experts in this field for relevant data on any ongoing or unpublished study. We handsearched both the Journal of Yoga and Physical Therapy and the International Journal of Yoga Therapy for additional studies. We last searched these two sources on 19 May 2014. We searched for potentially eligible studies in the reference lists of included studies. We identified ongoing studies in the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/mrct/) (May 2014) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/) (May 2014). We last searched these two sources on 13 May 2014.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One author (HLCL) performed the initial screening of titles and abstracts generated by the electronic searches. We retrieved full‐text papers for further assessment. Two authors (HLCL, FY) independently assessed the full text of all studies identified for eligibility for inclusion in the study against the prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria. They resolved any disagreements by consensus or by discussion with a third author (JSWK).

As we did not identify any trials that met our inclusion criteria, we did not perform data collection and synthesis or an assessment of risk of bias. We will perform the following methods in subsequent updates of the review provided sufficient data are available.

Data extraction and management

In future updates, two authors (HLCL, JSWK) will independently extract data using a standardised data extraction form. All relevant data on study design and settings, types of participants, interventions, and outcome measures will be extracted and recorded in the data extraction form. We will resolve disagreements by consensus or discussion with a third author (FY).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

In future updates, two authors (HLCL, JSWK) will independently assess risk of bias in the included studies as per the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). We will assess six specific domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias.

Dealing with missing data

In future updates, we will contact the original trial investigators in the case of missing or insufficient data to obtain further information. Available data will be analysed and missing data discussed as potential limitations of our review.

Data synthesis

We will calculate dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) and continuous data as mean differences (MDs) or standardised mean differences (SMDs). We will use random‐effects and fixed‐effect models to perform meta‐analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If sufficient data are available, we will explore subgroup analyses for gender, age, types of yoga, and trial duration.

We will investigate statistical heterogeneity across the included studies using the I2 statistic. We will apply a fixed‐effect model where there is no heterogeneity. Where substantial heterogeneity is observed (I2 > 50%), we will conduct meta‐analyses using a random‐effects model (Higgins 2011).

Sensitivity analysis

We will compare trials at low risk of bias with those at high risk of bias in a sensitivity analysis in order to explore the impact of bias on the treatment effects.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies

Results of the search

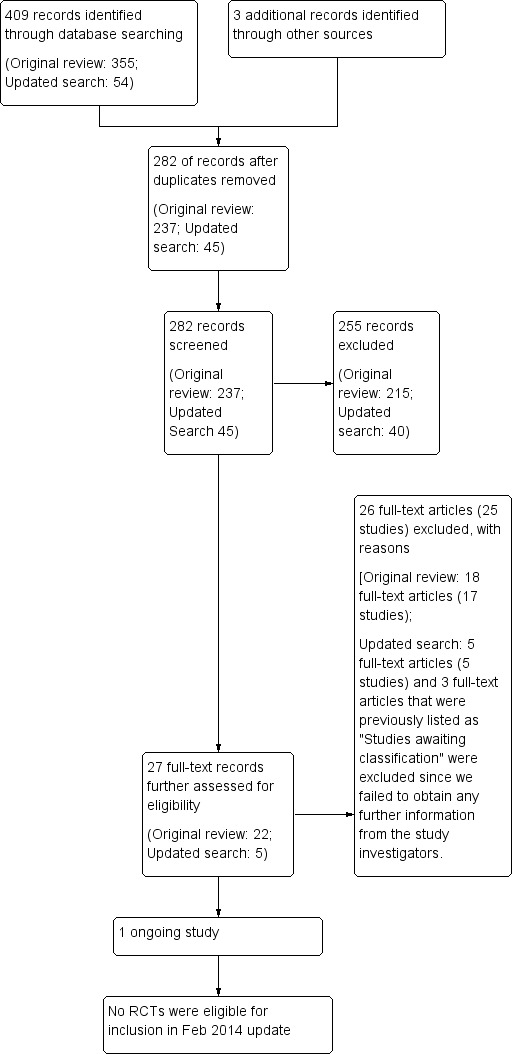

Our study selection process is illustrated as a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Figure 1) (Moher 2009). In the original review published in 2012 (Lau 2012), we identified 237 de‐duplicated citations with our search strategy, of which 54 were published in languages other than English (Chinese, German, Dutch, and Russian). Those publications written in German and Dutch were translated by native speakers, but we failed to find a Russian translator. Titles and abstracts were first screened by one author (HLCL) and then independently screened by two authors (HLCL, FY). We excluded a total of 215 irrelevant records (for example programme descriptions, review articles, case studies, or studies using a combination of treatments (such as aerobic exercise, music therapy, progressive muscular relaxation)). We obtained the full‐text articles of the remaining 22 records and of these we excluded 18 (17 studies) upon further examination (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Additionally, we identified three studies (Ma 2010a; Olivo 2009; Sheps 2007) and categorised them as "studies awaiting classification" and found one ongoing study (CTRI/2012/02/002408).

1.

Study flow diagram.

For the updated search in February 2014, we identified 45 de‐duplicated citations, of which 18 were published in Chinese. We excluded 40 irrelevant records after screening the title and abstracts. We retrieved full‐text of the remaining five records, which appeared to meet the inclusion criteria, for full assessment. However, we found that none were relevant to the scope of our review. We also excluded Ma 2010a; Olivo 2009 and Sheps 2007, which were previously categorised as "studies awaiting classification" since we failed to obtain any further information from the study investigators. We contacted the principal investigator of the ongoing study (CTRI/2012/02/002408), and the principal investigator provided some information about the study progress (see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Excluded studies

We excluded a total of 25 studies (reported in 26 articles) from the aforementioned literature searches because: they were not randomised, they investigated individuals suffering from CVD other than CHD, or data on the outcome measures included in this review were not available. Reasons for exclusion are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

None of the trials that were identified met the inclusion criteria for this review.

Effects of interventions

In the absence of any suitable RCTs, we were unable to perform any analyses.

Discussion

We identified insufficient data to determine the effectiveness of yoga for secondary prevention in CHD. This might be due to a lack of research interest in this topic and a low prevalence of the use of yoga for treating chronic health problems. Previous systematic reviews studied the efficacy of yoga in primary and secondary prevention of CVD (Innes 2005; Jayasinghe 2004). The majority of the identified studies focused on primary prevention, and only a few identified studies investigated secondary prevention. This may reflect under researching in this topic. A population‐based survey suggested a significant increase in the use of yoga as a kind of complementary and alternative medicine (Barnes 2008). However, the participants had a tendency to use complementary and alternative medicine to treat musculoskeletal problems rather than chronic diseases such as cholesterol problems. The low prevalence of the use of yoga might limit exploration of the therapeutic potential of yoga.

It is worth highlighting a recently published systematic review entitled "A systematic review of yoga for heart disease" (Cramer 2015), which included Pal 2011 and Pal 2013 in their analyses. These are two of our 25 excluded studies (Characteristics of excluded studies), and they were excluded because neither reported any of our primary outcomes (Primary outcomes). In Cramer 2015, analysis of mortality included the following numerical data from Pal 2011 and Pal 2013:

Pal 2011: one death in yoga group;

Pal 2013: five deaths (two in the yoga group, three in the control group).

However, when we looked at the data in greater depth, these were losses to follow up and fell outside the date by which follow up was completed (Pal 2011: six months; Pal 2013: 18 months). We thus did not consider these two studies for inclusion in our systematic review and remain confident that this decision, which mirrors that taken in the original review (Lau 2012), is correct.

Potential biases in the review process

Our search was comprehensive and we identified studies in languages other than English and several unpublished studies through trial registration platforms. The chief investigators of some identified studies were contacted to obtain additional methodological information to inform our decision as to whether these studies should be included; however, most investigators did not reply to our enquiry emails. We cannot, therefore, rule out the possibility that we may not have included some eligible studies.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

At present there is no randomised evidence by which to evaluate the effectiveness of yoga for secondary prevention in CHD, and hence we can draw no reliable conclusions supporting the use of yoga for secondary prevention in CHD. Increasing evidence has accumulated that yoga has therapeutic effects on various ailments and conditions, and thus studies investigating the potential effects of yoga in preventing CHD may be warranted.

Implications for research.

We identified one ongoing trial which may meet our inclusion criteria (CTRI/2012/02/002408). However, we still need a lot more high‐quality RCTs to obtain a definitive answer to the question of the effectiveness of yoga for secondary prevention in CHD. Better methodological quality should be emphasised in future studies, the design of trials, random sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding, estimating sufficient sample sizes to achieve adequate power, thus bias could be avoided and methodological quality improved. Trials should include relevant outcomes such as morbidity, composite cardiovascular events, and quality of life. Evaluations of cost, cardiovascular‐related hospital admissions, and adverse events are also needed. Participants from different ethnic groups and from different countries could be considered as part of more widespread research.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 June 2015 | Amended | Author's byline has been amended. |

| 21 July 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | An updated search on 13 February 2014 found no new studies for inclusion. The conclusions have not changed. |

| 14 July 2014 | New search has been performed | We updated our searches and excluded 45 new trials as none of them met our inclusion criteria for this review. In addition, three trials, which were awaiting for classification in the original review published in 2012, were excluded in this update as no further information was available. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editorial staff, editors and peer reviewers from the Cochrane Heart Group for their helpful advice; Professor Shah Ebrahim and the editorial team for constructive suggestions on the review development; Jo Abbott for revising and running the search strategy, providing the search results from English databases, and seeking translation services; and Nicole Martin and Haroen Shahak for translating articles written in German and Dutch, respectively.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies (original review: January 2012; update: February 2014)

CENTRAL

#1 MeSH descriptor Yoga explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Relaxation Therapy explode all trees #3 yoga #4 asana #5 pranayama #6 dhyana #7 meditat* #8 MeSH descriptor Meditation explode all trees #9 hatha #10 ananda #11 ashtanga #12 bikram #13 iyengar #14 integral near/5 yoga #15 kripalu #16 kundalini #17 power near/5 yoga #18 sivananda #19 vinyasa #20 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19) #21 MeSH descriptor Myocardial Ischemia explode all trees #22 MeSH descriptor Coronary Artery Bypass explode all trees #23 coronary near/2 disease* #24 ischemi* next heart #25 ischaemi* next heart #26 myocard* next ischemi* #27 myocard* next ischaemi* #28 myocard* next infarct* #29 heart next infarct* #30 coronary thrombo* #31 coronary near/3 angioplast* #32 angina* #33 coronary bypass* #34 CABG #35 PTCA #36 MeSH descriptor Angioplasty explode all trees #37 coronary next arteroscleros* #38 coronary next arterioscleros* #39 (#21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29 OR #30 OR #31 OR #32 OR #33 OR #34 OR #35 OR #36 OR #37 OR #38) #40 (#20 AND #39)

MEDLINE

1 Yoga/ 2 Relaxation Therapy/ 3 yoga.tw. 4 asana.tw. 5 pranayama.tw. 6 dhyana.tw. 7 meditat*.tw. 8 Meditation/ 9 hatha.tw. 10 ananda.tw. 11 ashtanga.tw. 12 bikram.tw. 13 iyengar.tw. 14 (integral adj5 yoga).tw. 15 kripalu.tw. 16 kundalini.tw. 17 (power adj5 yoga).tw. 18 sivananda.tw. 19 vinyasa.tw. 20 or/1‐19 21 exp Myocardial Ischemia/ 22 exp Coronary Artery Bypass/ 23 (coronary adj2 disease$).tw. 24 ischemi$ heart.tw. 25 ischaemi$ heart.tw. 26 myocard$ ischemi$.tw. 27 myocard$ ischaemi$.tw. 28 myocard$ infarct$.tw. 29 heart infarct$.tw. 30 coronary thrombo$.tw. 31 (coronary adj3 angioplast*).tw. 32 coronary bypass*.tw. 33 CABG.tw. 34 PTCA.tw. 35 Angioplasty, Transluminal, Percutaneous Coronary/ 36 coronary arteroscleros*.tw. 37 coronary arterioscleros*.tw. 38 angina$.tw. 39 or/21‐38 40 20 and 39 41 randomized controlled trial.pt. 42 controlled clinical trial.pt. 43 randomized.ab. 44 placebo.ab. 45 drug therapy.fs. 46 randomly.ab. 47 trial.ab. 48 groups.ab. 49 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 50 exp animals/ not humans.sh. 51 49 not 50 52 40 and 51

EMBASE

1 Yoga/ 2 Relaxation Therapy/ 3 yoga.tw. 4 asana.tw. 5 pranayama.tw. 6 dhyana.tw. 7 meditat*.tw. 8 Meditation/ 9 hatha.tw. 10 ananda.tw. 11 ashtanga.tw. 12 bikram.tw. 13 iyengar.tw. 14 (integral adj5 yoga).tw. 15 kripalu.tw. 16 kundalini.tw. 17 (power adj5 yoga).tw. 18 sivananda.tw. 19 vinyasa.tw. 20 or/1‐19 21 exp Myocardial Ischemia/ 22 exp Coronary Artery Bypas 23 (coronary adj2 disease$).tw. 24 ischemi$ heart.tw. 25 ischaemi$ heart.tw. 26 myocard$ ischemi$.tw. 27 myocard$ ischaemi$.tw. 28 myocard$ infarct$.tw. 29 heart infarct$.tw. 30 coronary thrombo$.tw. 31 (coronary adj3 angioplast*).tw. 32 coronary bypass*.tw. 33 CABG.tw. 34 PTCA.tw. 35 Angioplasty, Transluminal, Percutaneous Coronary/ 36 coronary arteroscleros*.tw. 37 coronary arterioscleros*.tw. 38 angina$.tw. 39 or/21‐38 40 20 and 39 41 random$.tw. 42 factorial$.tw. 43 crossover$.tw. 44 cross over$.tw. 45 cross‐over$.tw. 46 placebo$.tw. 47 (doubl$ adj blind$).tw. 48 (singl$ adj blind$).tw. 49 assign$.tw. 50 allocat$.tw. 51 volunteer$.tw. 52 crossover procedure/ 53 double blind procedure/ 54 randomized controlled trial/ 55 single blind procedure/ 56 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 57 (animal/ or nonhuman/) not human/ 58 56 not 57 59 40 and 58

Web of Science

# 26 #25 AND #24 # 25 TS=((random* or blind* or allocat* or assign* or trial* or placebo* or crossover* or cross‐over*)) # 24 #23 AND #7 # 23 #22 OR #21 OR #20 OR #19 OR #18 OR #17 OR #16 OR #15 OR #14 OR #13 OR #12 OR #11 OR #10 OR #9 OR #8 # 22 TS =("coronary arterioscleros*") # 21 TS =("coronary arteroscleros*") # 20 TS =(PTCA) # 19 TS =(CABG) # 18 TS =("coronary bypass*") # 17 TS =(angina*) # 16 TS =(coronary near/3 angioplast*) # 15 TS =("coronary thrombo*") # 14 TS =(heart infarct*) # 13 TS =("myocard* ischaemi*") # 12 TS =("myocard* ischemi*") # 11 TS =("myocard* infarct*") # 10 TS =("ischaemi* heart") # 9 TS =("ischemi* heart") # 8 TS =(coronary near/2 disease*) # 7 #6 OR #5 OR #4 OR #3 OR #2 OR #1 # 6 TS =(sivananda or vinyasa) # 5 TS =(kripalu or kundalini) # 4 TS =(integral near/5 yoga) # 3 TS =(hatha or ananda or ashtanga or bikram or iyengar) # 2 TS =(asana or pranayama or dhyana or meditat*) # 1 TS =(yoga)

CJN

(全文=瑜珈 OR 全文=瑜伽) AND (全文=心肌缺血 OR 全文=冠状动脉 OR 全文=缺血性心脏 OR 全文=心肌局部缺血 OR 全文=心脏梗塞 OR 全文=心绞痛 OR 全文=冠状动脉栓塞 OR 全文=冠状动脉硬化 OR 全文=冠状动脉搭桥 OR 全文=冠状动脉脉绕道手术 OR 全文=急经皮冠状动脉血管成形术 OR 全文=气球扩张) AND (全文=随机对照 OR 全文=控制临床 OR 全文=随机 OR 全文=安慰剂 OR 全文=测试) NOT (全文=动物 OR 全文=狗 OR 全文=犬 OR 全文=蛙 OR 全文=兔 OR 全文=鼠 OR 全文=猫 OR 全文=猴)

WanFang

(瑜珈+瑜伽)*(放松疗法+式子+体位法+呼吸+冥想+哈达+阿南达玛迦+八支+高温+热+艾扬格+灵量+昆达+力量+施化难陀+串连)*(心肌缺血+冠状动脉+缺血性心脏+心肌局部缺血+心脏梗塞+心绞痛+冠状动脉*(栓塞+硬化+搭桥+脉绕道手术)+急经皮冠状动脉血管成形术+气球扩张)*(随机对照+控制临床+随机+安慰剂+测试)^(动物+狗+犬+蛙+兔+鼠+猫+猴)期刊,学位,会议

HKInChiP

瑜珈

瑜伽

心肌缺血

冠狀動脈

缺血性心臟

心肌局部缺血

心臟梗塞

心絞痛

冠心病

mRCT

myocardial; angina; coronary heart; cardiovascular; each combined with the terms yoga, using the Boolean operator AND

WHO ICTRP Search Portal

myocardial; angina; coronary heart; cardiovascular; each combined with the terms yoga, using the Boolean operator AND

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Alexander 2013 | The study was not a randomised controlled trial. (Quote: "Design: This study used a constructivist‐interpretive approach to naturalistic inquiry. Setting: A total of 42 participants completed the intervention and met the inclusion criteria for the current qualitative study. Intervention: The 8‐week Iyengar yoga program included two 90‐min yoga classes and five 30‐min home sessions per week. Participants completed weekly logs and an exit questionnaire at the end of the study.") |

| Boxer 2010 | Participants were not individuals with coronary heart disease. |

| Carranque 2012 | Participants were not individuals with coronary heart disease. (Quote: "Twenty‐six healthy subjects (7 male, 19 female) aged between 30 and 50 took part in this study.") |

| Casey 2009 | The study was not a randomised controlled trial. (Quote: "This analysis did not include a control group for comparison.") |

| Cheung 2009 | This was a descriptive study. |

| Cui 2011 | The study was not a randomised controlled trial. (The subjects were randomly assigned to intervention and control groups, but the intervention consisted of various kinds of treatments, and the subjects were able to choose the treatments based on personal preference.) |

| Edelman 2006 | The study investigated participants with cardiovascular risk factors without cardiovascular disease. (Quote: "We excluded subjects with active cardiovascular disease, defined as a history of myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure, or cerebrovascular accident (CVA).") |

| Hipp 1998 | The study was not a randomised controlled trial and the outcomes we examined in this review were not reported. |

| Jatuporn 2003 | The outcomes we examined in this review were not reported. |

| Kulshreshtha 2011 | No full text could be found; also the follow‐up period and other outcome measures of the study were uncertain (we contacted the trial investigators but failed to get a reply). |

| Langosch 1982 | The study was not a randomised controlled trial. (Quote: "..... assigned to one of the treatment groups according to personal preference.") |

| Ma 2010a | The detail of the relaxation training was not described in this abstract (we are unable to contact the authors to obtains further details). |

| Ma 2010b | The follow‐up period was shorter than six months (data were reported for four periods: eight hours, one week, three weeks, and five weeks after percutaneous coronary intervention). The outcomes we examined in this review were not reported. |

| Manchanda 2000 | The intervention of the study consisted of a combination of treatments (i.e. yoga lifestyle methods, stress management, dietary control, and moderate aerobic exercise). We excluded multifactorial intervention trials from this review to avoid confounding. |

| Nandakumar 2012 | Participants were not individuals with coronary heart disease, and the intervention follow‐up period was shorter than six months. (Quote: "In this randomized waitlisted controlled clinical trial, 72 subjects with known cardiovascular risk factors were randomized to receive residential 3 week yoga and naturopathy intervention (n=37) or waitlisted (n=35) to receive the same later.") |

| Nyklicek 2008 | Participants were not individuals with coronary heart disease. |

| Olivo 2009 | The results of the trial were not available (we contacted the trial investigators but failed to get a reply). |

| Pal 2011 | The outcomes we examined in this review were not reported. |

| Pal 2013 | The outcomes we examined in this review were not reported. |

| Robert‐McComb 2004 | The follow‐up period was shorter than six months. (Confirmed by contacting the author by email. Quote: "We did not have a follow‐up period other than the pre‐post test following the intervention which was 8 weeks.") |

| Rutledge 1999 | The study was not a randomised controlled trial, no control group was included. |

| Schneider 1995 | The outcomes we examined in this review were not reported, and participants suffered from hypertension. |

| Sheps 2007 | The results of the trial were not available (we contacted the trial investigators but failed to get a reply). |

| Toise 2014 | Participants were not individuals with coronary heart disease. |

| Yogendra 2004 | The study was not a randomised controlled trial. (Confirmed by contacting the author by email. Quote: "Our original study was prospective controlled open trial and not randomized.") |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

CTRI/2012/02/002408.

| Trial name or title | A study on the effectiveness of a yoga‐based cardiac rehabilitation programme in India and the United Kingdom |

| Methods | Randomised, parallel‐group trial Method of generating random sequence: computer‐generated randomisation Method of concealment: on‐site computer system Blinding/masking: open label |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria Individuals who are not willing to consent |

| Interventions | Intervention group: yoga‐based cardiac rehabilitation programme The intervention being assessed will be Yoga‐CaRe, a yoga‐based cardiac rehabilitation programme, delivered at the hospital in 13 sessions spread over three months after enrolment, complemented by audio‐video material for self‐supervised sessions at home. All Yoga‐CaRe sessions will be provided by the Yoga‐CaRe instructor Control group: standard care The control arm will receive enhanced standard care involving a leaflet in the hospital before discharge (session one), followed by two sessions offering standard educational advice at weeks 5 and 12 (sessions two and three). The sessions will be delivered in groups (similar to the intervention). A different member of the team (i.e. not the yoga instructor) will deliver these sessions to avoid contamination Immediately after the last intervention session, an interview will be carried out in‐person to collect data on quality of life, daily activities, smoking and compliance with medications, etc. Further follow up will be carried out for hard endpoints (cardiac mortality and morbidity) through two‐monthly telephone calls. The trial will last for two years, and all participants will be followed until the end of the trial (in order to ensure an average follow up of one year duration) |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes

Secondary outcomes

|

| Starting date | September 2012 |

| Contact information | Principal Investigator: Professor Dorairaj Prabhakaran Email: dprabhakaran@ccdcindia.org |

| Notes | The above information was extracted from: www.ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/pmaindet2.php?trialid=3992 Further information was provided by the principal investigator by email on 14 May 2014 (Quote: "We have just finished with the training the signing of CTA set and other administrative issues. The first patient is likely to be recruited early June. We hope to complete recruiting 4000 patients by 18 months.") |

Contributions of authors

HLCL, JSWK developed the original concept of the review and drafted the protocol.

HLCL and FY screened studies against the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

PHC provided statistical advice.

HLCL and JSWK wrote the final review.

All authors read and approved it for publication.

Sources of support

Internal sources

The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies excluded from this review

Alexander 2013 {published data only}

- Alexandera GK, Innes KE, Selfe TK, Brown CJ. ‘‘More than I expected’’: perceived benefits of yoga practice among older adults at risk for cardiovascular disease. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2013;21(1):14‐28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boxer 2010 {published data only}

- Boxer RS, Kleppinger A, Brindisi J, Feinn R, Burleson JA, Kenny AM. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on cardiovascular risk factors in older women with frailty characteristics. Age and Ageing 2010;39(4):451‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Carranque 2012 {published data only}

- Carranque GA, Maldonado EF, Vera FM, Manzaneque JM, Blanca MJ, Soriano G, et al. Hematological and biochemical modulation in regular yoga practitioners. Biomedical Research 2012;23(2):176‐82. [Google Scholar]

Casey 2009 {published data only}

- Casey A, Chang BH, Huddleston J, Virani N, Benson H, Dusek JA. A model for integrating a mind/body approach to cardiac rehabilitation: outcomes and correlators. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention 2009;29(4):230‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cheung 2009 {published data only}

- Cheung YK. Effect of yoga practice on several common diseases [瑜伽对几种常见疾病的作用]. 中国临床保健杂志 2009;6(12):666‐8. [Google Scholar]

Cui 2011 {published data only}

- Cui QY. Impact of targeted health education on the patients with chronic stable angina [目标性健康教育对慢性稳定型心绞痛患者的影响]. Journal of Qilu Nursing 2011;17(4):11‐2. [Google Scholar]

Edelman 2006 {published data only}

- Edelman D, Oddone EZ, Liebowitz RS, Yancy WS, Olsen MK, Jeffreys AS, et al. A multidimensional integrative medicine intervention to improve cardiovascular risk. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2006;21(7):728‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hipp 1998 {published data only}

- Hipp A, Heitkamp HC, Rocker K, Schuller H, Dickhuth HH. Effects of yoga on lipid metabolism in patients with coronary artery disease. International Journal of Sports Medicine 1998;19:S7. [Google Scholar]

Jatuporn 2003 {published data only}

- Jatuporn S, Sangwatanaroj S, Saengsiri AO, Rattanapruks S, Srimahachota S, Uthayachalerm W, et al. Short‐term effects of an intensive lifestyle modification program on lipid peroxidation and antioxidant systems in patients with coronary artery disease. Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation 2003;29(3‐4):429‐36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kulshreshtha 2011 {published data only}

- Kulshreshtha A, Norton C, Veledar E, Eubanks G, Sheps D. Mindfulness based meditation results in improved subjective emotional assessment among patients with coronary artery disease: Results from the mindfulness based stress reduction study. Psychosomatic Medicine. Proceedings of the 69th Annual Meeting of the American Psychosomatic Society; 9‐12 March 2011; San Antonio (TX). 2011; Vol. 73.

Langosch 1982 {published data only}

- Langosch W, Seer P, Brodner G, Kallinke D, Kulick B, Heim F. Behavior therapy with coronary heart disease patients: results of a comparative study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 1982;26(5):475‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ma 2010a {published data only}

- Ma W, Hu D, Liu G, Jiang J, Deng B, Liu R, Liu X, Gao W. Effect of patient‐specific intervention of depression on quality of life after acute coronary syndrome. Circulation 2010;122(2):e251. [Google Scholar]

Ma 2010b {published data only}

- Ma TK, Cheung WY, Ho K, Cheung YP. Effect of the psychological intervention on coronary heart disease patients after PTCA [心理干預加文拉法星治療冠狀動脈支架植入術后患者負性情緒的臨床研究]. Shanxi Medical Journal 2010;7(39):600‐1. [Google Scholar]

Manchanda 2000 {published data only}

- Manchanda R, Narang R, Reddy KS, Sachdeva U, Prabhakaran D, Dharmanand S, et al. Retardation of coronary atherosclerosis with yoga lifestyle intervention. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 2000;48(7):687‐94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchanda R, Narang R, Reddy KS, Sachdeva U, Prabhakaran D, Dharmanand S, et al. Reveral of coronary atherosclerosis by yoga lifestyle intervention. In: Dhalla NS, Chockalingam A, Berkowitz HI, Singal PK editor(s). Frontiers in Cardiovascular Health. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003:535‐47. [Google Scholar]

Nandakumar 2012 {published data only}

- Nandakumar B, Kadam A, Srikanth H, Rao R. Naturopathy and yoga based life style intervention for cardiovascular risk reduction inpatients with cardiovascular risk factors: a pilot study. BMC Complementary & Alternative Medicine 2012;12(Suppl 1):P106. [DOI: 10.1186/1472688212S1P106] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Nyklicek 2008 {published data only}

- Nyklicek I, Kuijpers KF. Effects of mindfulness‐based stress reduction intervention on psychological well‐being and quality of life: is increased mindfulness indeed the mechanism?. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2008;35(3):331‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Olivo 2009 {unpublished data only}

- NCT01020227. Usefulness of integrative medicine tools as adjunctive care for women after coronary artery bypass grafting. clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01020227 (accessed 27 May 2015).

Pal 2011 {published data only}

- Pal A, Srivastava N, Tiwari S, Verma NS, Narain VS, Agrawal GG, et al. Effect of yogic practices on lipid profile and body fat composition in patients of coronary artery disease. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2011;19(3):122‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pal 2013 {published data only}

- Pal A, Srivastava N, Narain VS, Agrawal GG, Rani M. Effect of yogic intervention on the autonomic nervous system in the patients with coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 2013;19(5):452‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Robert‐McComb 2004 {published data only}

- Robert‐McComb JJ, Randolph P, Caldera Y. A pilot study to examine the effects of a mindfulness‐based stress‐reduction and relaxation program on levels of stress hormones, physical functioning, and submaximal exercise responses. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2004;10(5):819‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rutledge 1999 {published data only}

- Rutledge JC, Hyson DA, Garduno D, Cort DA, Paumer L, Kappagoda CT. Lifestyle modification program in management of patients with coronary artery disease: the clinical experience in a tertiary care hospital. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation 1999;19(4):226‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schneider 1995 {published data only}

- Schneider RH, Staggers F, Alexander CN, Sheppard W, Rainforth M, Kondwani K, et al. A randomized controlled trial of stress reduction for hypertension in older African‐Americans. Hypertension 1995;26(5):820‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sheps 2007 {unpublished data only}

- NCT00224835. Mindfulness‐based stress reduction and myocardial ischemia. clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00224835 (accessed 27 May 2015).

Toise 2014 {published data only}

- Toise SCF, Sears SF, Schoenfeld MH, Blitzer ML, Marieb MA, Drury JH, et al. Psychosocial and cardiac outcomes of yoga for ICD patients: a randomized clinical control trial. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology 2014;37(1):48‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yogendra 2004 {published data only}

- Yogendra J, Yogendra HJ, Ambardekar S, Lele RD, Shetty S, Dave M, et al. Beneficial effects of yoga lifestyle on reversibility of ischaemic heart disease: caring heart project of International Board of Yoga. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 2004;52:283‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

CTRI/2012/02/002408 {unpublished data only}

- CTRI/2012/02/002408. A study on effectiveness of YOGA based cardiac rehabilitation programme in India and United Kingdom. ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/pmaindet2.php?trialid=3992 (accessed 27 May 2015).

Additional references

ACSM 2010

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's Resource Manual for Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 6. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010. [Google Scholar]

AHA 2011a

- American Heart Association. How can I make my lifestyle healthier?. http://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart‐public/@wcm/@hcm/documents/image/ucm_300674.pdf (accessed 27 May 2015).

AHA 2011b

- American Heart Association. Physical activity improves quality of life. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/PhysicalActivity/StartWalking/Physical‐activity‐improves‐quality‐of‐life_UCM_307977_Article.jsp (accessed 27 May 2015).

Barnes 2008

- Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. National Health Statistics Reports 2008;12:1‐23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Booth‐LaForce 2007

- Booth‐LaForce C, Thurston RC, Taylor MR. A pilot study of a Hatha yoga treatment for menopausal symptoms. Maturitas 2007;57(3):286‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bosch 2009

- Bosch PR, Traustadottir T, Howard P, Matt KS. Functional and physiological effects of yoga in women with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 2009;15(4):24‐31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bukowski 2007

- Bukowski EL, Conway A, Glentz LA, Kurland K, Galantino ML. The effect of Iyengar yoga and strengthening exercises for people living with osteoarthritis of the knee: a case series. International Quarterly of Community Health Education 2007;26(3):287‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chen 2008

- Chen KM, Chen MH, Hong SM, Chao HC, Lin HS, Li CH. Physical fitness of older adults in senior activity centres after 24‐week silver yoga exercises. Journal of Nursing 2008;17:2634–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cramer 2015

- Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Dobos G, Michalsen A. A systematic review of yoga for heart disease. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 2015;22(3):284‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Culos‐Reed 2006

- Culos‐Reed SN, Carlson LE, Daroux LM, Hately‐Aldous S. A pilot study of yoga for breast cancer survivors: physical and psychological benefits. Psycho‐Oncology 2006;15(10):891‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DiStasio 2008

- DiStasio SA. Integrating yoga into cancer care. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing 2008;12(1):125‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Donesky‐Curenco 2009

- Donesky‐Curenco D, Nguyen HQ, Paul S, Carrier‐Kohlman V. Yoga therapy decreases dyspnea‐related distress and improves functional performance in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot study. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2009;15(3):225‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Frishman 2005

- Frishman WH, Weintraub MI, Micozzi MS. Complementary and Integrative Therapies for Cardiovascular Disease. St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier/Mosby, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Granath 2006

- Granath J, Ingvarsson S, Thiele U, Lundberg U. Stress management: a randomized study of cognitive behavioural therapy and yoga. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 2006;35(1):3‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Groessl 2008

- Groessl E J, Weingart KR, Aschbacher K, Pada L, Naxi S. Yoga for veterans with chronic low‐back pain. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2008;14(9):1123‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hagins 2007

- Hagins M, Moore W, Rundle A. Does practicing hatha yoga satisfy recommendations for intensity of physical activity which improves and maintains health and cardiovascular fitness?. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2007;7:40. [DOI: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-40] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hall 2010

- Hall SL, Lorenc T. Secondary prevention of coronary artery disease. American Family Physician 2010;81(3):289‐96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hartley 2014

- Hartley L, Dyakova M, Holmes J, Clarke A, Lee MS, Ernst E, Rees K. Yoga for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 5. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010072.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heran 2011

- Heran BS, Chen JMH, Ebrahim S, Moxham T, Oldridge N, Rees K, et al. Exercise‐based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 7. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001800.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hewitt 2001

- Hewitt J. The Complete Yoga Book. New York: Schocken Books Inc., 2001. [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hobbs 2004

- Hobbs FDR. Cardiovascular disease: different strategies for primary and secondary prevention?. Heart 2004;90(10):1217‐23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Innes 2005

- Innes KE, Bourguignon C, Taylor AG. Risk indices associated with the insulin resistance syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and possible protection with yoga: a systematic review. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice 2005;18(6):491‐519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Innes 2007

- Innes KE, Vincent HK, Taylor AG. Chronic stress and insulin resistance‐related indices of cardiovascular disease risk, part 2: a potential role for mind‐body therapies. Alternative Therapies 2007;13(5):44‐51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jayasinghe 2004

- Jayasinghe SR. Yoga in cardiac health (a review). The European Society of Cardiology 2004;11(5):369‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kappmeier 2006

- Kappmeier KL, Ambrosini DM. Instructing Hatha Yoga. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Larzelere 2008

- Larzelere MM, Jones GN. Stress and health. Primary Care 2008;35(4):839‐56. [DOI: 10.1016/j.pop.2008.07.011] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lavey 2005

- Lavey R, Sherman T, Mueser KT, Osborne DD, Currier M, Wolfe R. The effects of yoga on mood in psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 2005;28(4):399‐402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lavie 2009

- Lavie CJ, Thomas RJ, Squires RW, Allison TG, Milani RV. Exercise training and cardiac rehabilitation in primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2009;84(4):373‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lefebvre 2011

- Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J. Chapter 6: Searching for studies. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Leon 2005

- Leon AS, Franklin BA, Costa F, Balady GJ, Berra KA, Stewart KJ, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: an American Heart Association Scientific Statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology (Subcommittee on Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention) and the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (Subcommittee of Physical Activity), in collaboration with the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Circulation 2005;111(13):369‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Levine 2000

- Levine M. The Positive Psychology of Buddhism and Yoga: Paths to a Mature Happiness: with a Special Application to Handling Anger. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers, 2000. [Google Scholar]

Lindholm 2007

- Lindholm LH, Mendis S. Prevention of cardiovascular disease in developing countries. Lancet 2007;370(9589):720‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mendelson 2008

- Mendelson SD. Metabolic Syndrome and Psychiatric Illness: Interactions, Pathophysiology, Assessment and Treatment. Amsterdam; Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Michalsen 2005

- Michalsen A, Grossman P, Acil A, Langhorst J, Lüdtke R, Esch T, et al. Rapid stress reduction and anxiolysis among distressed women as a consequence of a three‐month intensive yoga program. Medical Science Monitor 2005;11(12):555‐61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mittal 2008

- Mittal S. The Metabolic Syndrome in Clinical Practice. London: Springer, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Moher 2009

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mourya 2009

- Mourya M, Mahajan AS, Singh NP, Jain AK. Effect of slow‐ and fast‐breathing exercises on autonomic functions in patients with essential hypertension. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2009;15(7):711‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Murchie 2003

- Murchie P, Campbell NC, Ritchie LD, Simpson JA, Thain J. Secondary prevention clinics for coronary heart disease: four year follow up of a randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMJ 2003;326(7380):84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O'Keefe 2009

- O'Keefe JH, Carter MD, Lavie CJ. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases: a practical evidence‐based approach. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2009;84(8):741‐57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Oken 2006

- Oken BS, Zajdel D, Kishiyama S, Flegal K, Dehen C, Haas M, et al. Randomized, controlled, six‐month trial of yoga in healthy seniors: effects on cognition and quality of life. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 2006;12(1):40‐7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Riley 2004

- Riley D. Hatha yoga and the treatment of illness. Alternative Therapies in Heath and Medicine 2004;10(2):20‐1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ripoll 2002

- Ripoll E, Mahowald D. Hatha yoga therapy management of urologic disorders. World Journal of Urology 2002;20(5):306‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rozanski 2005

- Rozanski A, Blumental JA, Davidson KW, Saab PG, Kubzansky L. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factor in cardiac practice: the emerging field of behavioral cardiology. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2005;45(5):637‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Saper 2004

- Saper RB, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Culpepper L, Phillips RS. Prevalence and patterns of adult yoga use in the United States: results of a national survey. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 2004;10(2):44‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Satyapriya 2009

- Satyapriya M, Nagendra HR, Nagarathna R, Padmalatha V. Effect of integrated yoga on stress and heart rate variability in pregnant women. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2009;104(3):218‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schnell 2012

- Schnell O, Erbach M, Hummel M. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in diabetes with aspirin. Diabetes & Vascular Disease Research 2012;9(4):245‐55. [DOI: 10.1177/1479164112441486] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Smith 2011

- Smith SC Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, Braun LT, Creager MA, Franklin BA, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation 2011;124(22):2458‐73. [DOI: 10.1161/%E2%80%8BCIR.0b013e318235eb4d] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tekur 2008

- Tekur P, Singhow C, Nagendra HR, Raghuram N. Effect of short‐term intensive yoga program on pain, functional disability, and spinal flexibility in chronic low back pain: a randomized control study. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2008;14(6):637‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

USHHS 1996

- US Department of Heath and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Vadiraja 2009

- Vadiraja HS, Raghavendra RM, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR, Rehka M, Vanitha N, et al. Effects of a yoga program on cortisol rhythm and mood states in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Integrative Cancer Therapies 2009;8(1):37‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Visweswaraiah 2004

- Visweswaraiah NK, Telles S. Randomized trial of yoga as a complementary therapy for pulmonary tuberculosis. Respirology 2004;9(1):96‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wannamethee 2000

- Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Walker M. Physical activity and mortality in older men with diagnosed coronary heart disease. Circulations 2000;102(12):1358‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

West 2004

- West J, Otte C, Geher K, Johnson J, Mohr DC. Effects of hatha yoga and African dance on perceived stress, affect, and salivary cortisol. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2004;28(2):114‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Whalley 2011

- Whalley B, Rees K, Davies P, Bennet P, Ebrahim S, Liu Z, et al. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002902.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 2007

- World Health Organization. Prevention of cardiovascular disease: pocket guidelines for assessment and management of CVD risk. http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/guidelines/Pocket_GL_information/en/index.html. WHO Press, 2007 (accessed 27 May 2015).

WHO 2011a

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular disease. http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/en/ (accessed 27 May 2015).

WHO 2011b

- World Health Organization. Media centre: Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/index.html January 2015 (accessed 27 May 2015).

Williams 2002

- Williams MA, Fleg JL, Ades PA, Chaitman BR, Miller NH, Mohiuddin SM, et al. Secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in the elderly (with emphasis on patients ≥75 years of age): an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology Subcommittee on Exercise, Cardiac rehabilitation, and Prevention. Circulation 2002;105(14):1735‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Woolery 2004

- Woolery A, Myers H, Sternlieb B, Zeltzer L. A yoga intervention for young adults with elevated symptoms of depression. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 2004;10(2):60‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yoga Alliance 2015

- Yoga Alliance. Types of Yoga. https://www.yogaalliance.org/LearnAboutYoga/AboutYoga/Typesofyoga (accessed 27 May 2015).

Yusuf 2004

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case‐control study. Lancet 2004;364(9438):937‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Lau 2012

- Lau HLC, Kwong JSW, Yeung F, Chau PH, Woo J. Yoga for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 12. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009506.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]