Abstract

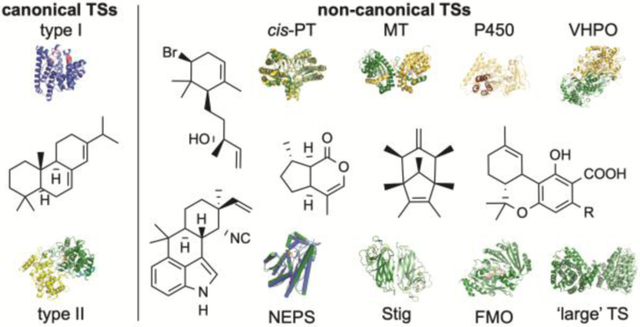

Terpene synthases (TSs) are responsible for generating much of the structural diversity found in the superfamily of terpenoid natural products. These elegant enzymes mediate complex carbocation-based cyclization and rearrangement cascades with a variety of electron-rich linear and cyclic substrates. For decades, two main classes of TSs, divided by how they generate the reaction-triggering initial carbocation, have dominated the field of terpene enzymology. Recently, several novel and unconventional TSs that perform TS-like reactions but do not resemble canonical TSs in sequence or structure have been discovered. In this review, we identify 12 families of non-canonical TSs and examine their sequences, structures, functions, and proposed mechanisms. Nature provides a wide diversity of enzymes, including prenyltransferases, methyltransferaes, P450s, and NAD+-dependent dehydrogenases, as well as completely new enzymes, that utilize distinctive reaction mechansims for TS chemistry. These unique non-canonical TSs provide immense opportunities to understand how nature evolved different tools for terpene biosynthesis by structural and mechanistic characterization while affording new probes for the discovery of novel terpenoid natural products and gene clusters via genome mining. With every new discovery, the dualistic paraidgm of TSs is contradicted and the field of terpene chemistry and enzymology continues to expand.

Graphical Abstract

Twelve families of enzymes that perform terpene synthase-like reactions but do not resemble canonical terpene synthases in sequence, structure, or function are reviewed.

1. Introduction

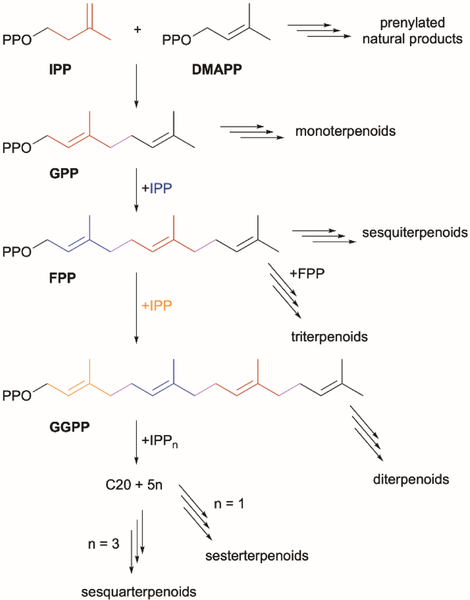

With over 76,000 characterized members, terpenoids are the largest and most structurally diverse family of natural products and are found in all domains of life (http://dnp.chemnetbase.com). All terpenoids are constructed from the same two C5 activated isoprene units (Fig. 1): the allylic dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) and the homoallylic isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP). These fundamental building blocks are either directly used to alkylate other natural product scaffolds or are combined in successive fashion to generate linear chains with lengths varying by multiples of five (i.e., prenylation). The C10, C15, and C20 linear allylic diphosphates are geranyl diphosphate (GPP), farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) and subfamilies of terpenoids are classified based on carbon numbers with monoterpenoids (C10), sesquiterpenoids (C15), diterpenoids (C20), and triterpenoids (C30) the largest and most well-studied subfamilies (Fig. 1). Other families including the sesterterpenoids (C25) and sesquarterpenoids (C35) are less common. The longer terpene diphosphates (C15–C35) can be used for direct prenylation reactions but are most commonly used as substrates for complex regio- and stereoselective cyclization reactions. In fact, the vast structural diversity of terpenoids arises from these cyclization, and other skeletal rearrangement, reactions.

Fig. 1.

The biosynthesis of terpenoids via chain elongation of IPP and DMAPP.

The “biogenetic isoprene rule,” proposed by Nobel laureate Leopold Ruzicka and based on the original “isoprene rule” coined by the earlier Nobel laureate Otto Wallach,1 stated that all terpenoids are derived from chains of assembled isoprene units in carbocation reactions.2 The chemical nature of carbocations and the reactivity of the electron-rich linear terpenes not only assembles a library of C5n terpene precursors (Fig. 1), but also provides access to a myriad of mono- and polycyclic carbon skeletons. The enzymes that mediate these reactions, through a combination of substrate preference and folding, transient carbocation stabilization, and controlled carbocation quenching, are known as terpene synthases (TS). For decades, there have been two canonical types or classes of TSs that have been separated according to their sequences, structures, functions, and associated mechanisms.

Although these classical TSs continue to dominate the field of terpene enzymology, there is a growing number of novel, unconventional TSs that perform TS-like reactions (mainly cyclizations).3 The majority of these enzymes do not resemble canonical TSs in sequence or structure and while some of these enzymes generate carbocations, others forego carbocation chemistry altogether. Here, we aim to address the growing field of non-canonical TSs by reviewing how these enzymes were discovered, assessing their broad biochemical and mechanistic attributes, and providing a perspective on how these enzymes are changing the field of terpene chemistry and enzymology. We organized the non-canonical TSs in this review into two groups (Table 1): TSs that were predicted as other types of enzymes and TSs that could not be bioinformatically predicted (i.e., completely novel).

Table 1.

Biochemically characterized non-canonical terpene synthases

| Enzyme Family (PFAM/IPR)a | Member(s)b | UniProt ID | Biosynthetic Pathway | Mechanism (proposed) | Asp-Rich Motif(s) | PDB ID(s) | Ref.b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other Families | |||||||

| cis-PT (PF01255/IPR036424) | CLDS | X5IYJ5 | Lavanducyanin | Type I | - | 5GUK, 5GUL, 5YGJ, 5YGK | 44,46 |

| UbiA-type cyclase (PF01040/IPR000537) | PtnT1 | E2CYS2 | Platencin | Type I | DxxxD and NxxxDxxxD | - | 53 |

| fma-TC | M4VQY9 | Fumagillin | Type I | DxxxD and NxxxGxxxD | - | 63 | |

| EriG | A0A1V0QSF1 | Erinacin | Type I | DxxxD and NxxxGxxxD | - | 50 | |

| Methyltransferase (PF08241/IPR029063) | TleD | A0A077K7L1 | Teleocidin | Type I (methylation) | - | 5GM1, 5GM2 | 90,91 |

| SodC | A0A318P5Q0 | Sodorifen | Type I (methylation) | - | - | 94,97 | |

| Vanadium haloperoxidase (PF01569/IPR036938) | CVBPO | Q8LLW7 | Snyderols | Type II (bromonium) | - | 1QHB | 113,114,116 |

| NapH1 | A7KH27 | Napyradiomycins | Type II (chloronium) | - | 3W35, 3W36 | 125 | |

| NapH4 | A7KH33 | Napyradiomycins | Type II (chloronium) | - | - | 109 | |

| Mcl24 | M4TL26 | Merochlorins | Type II (chloronium) | - | - | 45,129 | |

| Mcl40 | M4T7F4 | Merochlorins | Type II (chloronium) | - | Unpublished | 127 | |

| Cytochrome P450 (PF00067/IPR001128) | PntM | E3VWI3 | Pentalenolactone | One-electron transfer | - | 5L1O–5L1T | 143 |

| VrtK | D7PHY9 | Viridcatumtoxin | One-electron transfer | - | - | 160 | |

| CYP170A1 | Q9K498 | Farnesene | Type I | DDxxD and DTE | 3DBG, 3EL3 | 168 | |

| Flavin-dependent oxidocyclase (PF08031/IPR036318) | Δ9-THCA synthase | Q8GTB6 | Δ9-Tetrahydrocanna-binolic acid | FAD-dependent two-electron transferase | - | 3VTE | 174–176 |

| (PF08028/IPR036250) | XiaF | I7IIA9 | Xiamycin | FAD-dependent hydroxylation | - | 5LVU, 5LVW, 5MR6 | 184–186 |

| Non-oxidative NAD+-dependent cyclase (no PFAM/IPR036291) | NEPS3 | A0A4P1LYE8 | Iridoids | NAD+-dependent non-oxidative | - | 6F9Q | 201 |

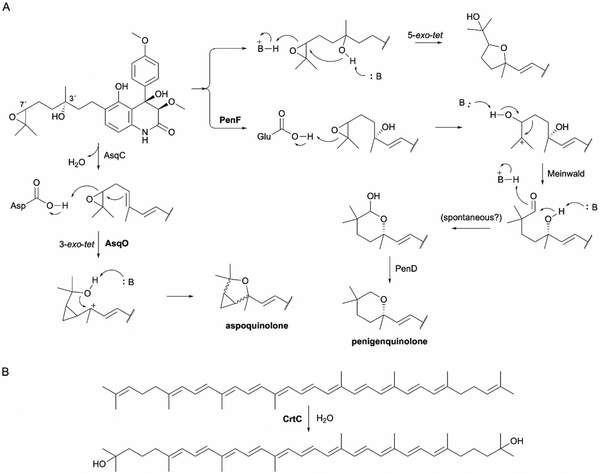

| CrtC-like cyclase (no PFAM/no IPR) | PenF | A0A1B2CTB3 | Penigequinolone | Epoxide rearrangement | - | - | 205 |

| AsqO | C8VJQ2c | Aspoquinolone | Epoxide rearrangement | - | - | 205 | |

| New Families | |||||||

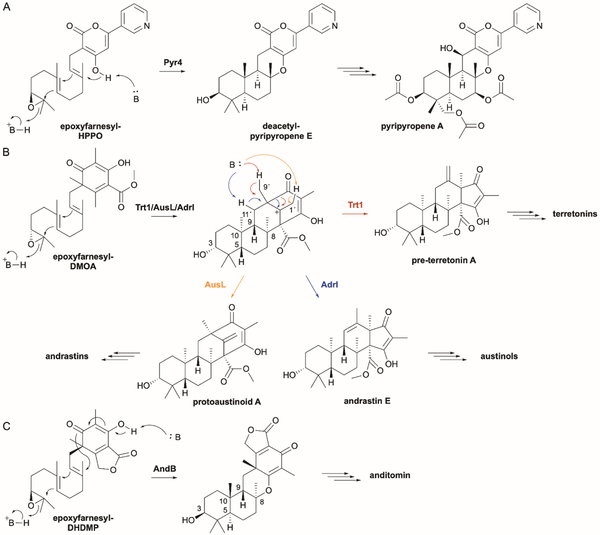

| Integral membrane cyclase (no PFAM/IPR039020) | Pyr4 | Q4WLD2 | Pyripyropene A | Type II | - | - | 218 |

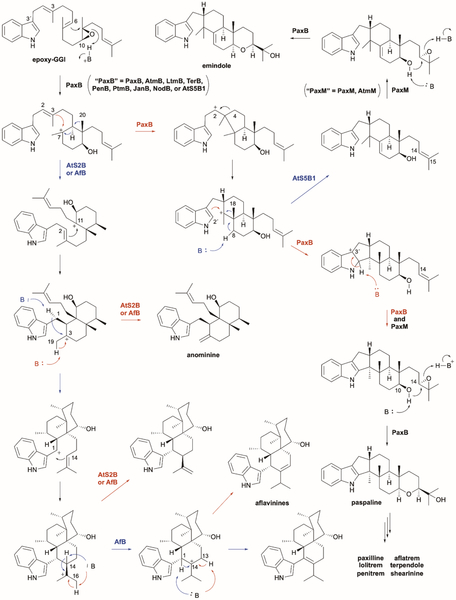

| PaxB | E3UBL6 | Paxilline | Type II | - | - | 227 | |

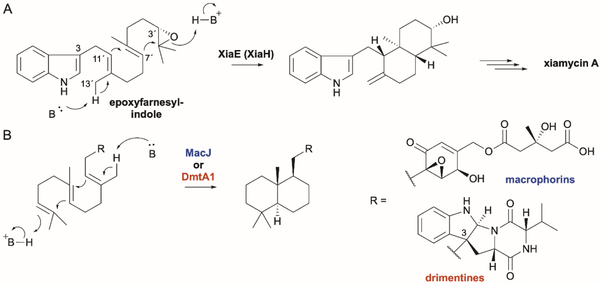

| XiaE | I7KIT8 | Xiamycin | Type II | - | - | 184,185 | |

| DmtA1 | A0A343VTS1 | Drimentines | Type II | - | - | 238 | |

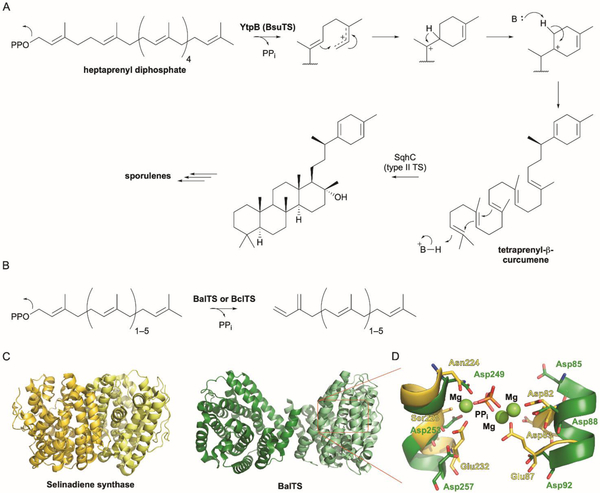

| Large terpene synthase (PF010776/IPR019712) | YtpB (BsuTS) | O34707 | Sporulenes | Type I | DxxDxxxD and DxxxDxxED | - | 242 |

| BalTS | A0A094YZ24 | Large β-prenes | Type I | DxxDxxxD and DxxxDxxED | 5YO8 | 243 | |

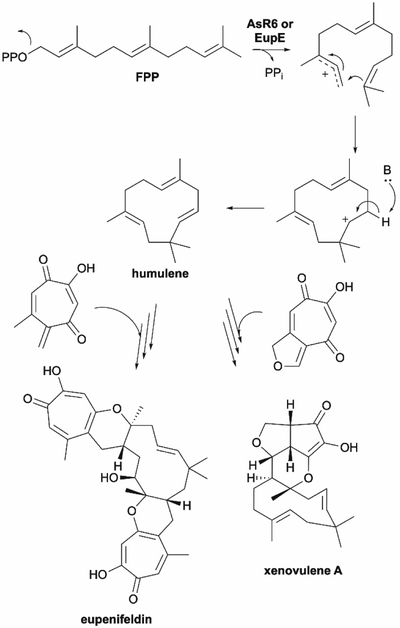

| Non-canonical humulene synthase (no PFAM/no IPR) | AsR6 | A0A2U8U2L5 | Xenovulene | Type I | - | - | 250 |

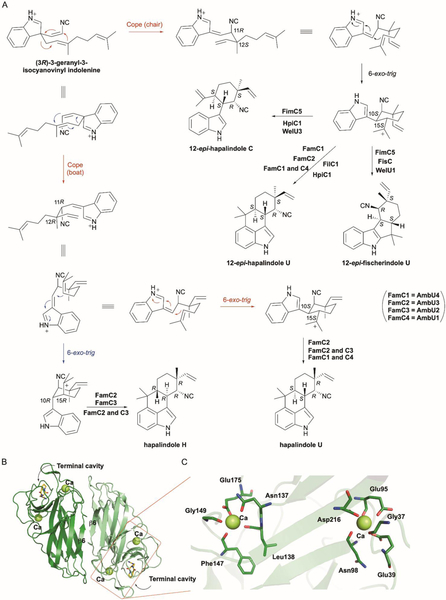

| Stig cyclase (no PFAM/IPR008979) | FamC1 (AmbU4) | A0A076N4W8 (V5TER4) | Hapalindoles | Cope rearrangement | - | 5YVK | 260,261 |

| HpiC1 | A0A76NBW8 | Hapalindoles | Cope rearrangement | - | 5WPP, 5WPR, 5WPS, 5WPU, 5YVL, 5Z54 | 265 | |

| WelU1 | A0A067YVF6 | Welwitindolinones | Cope rearrangement | - | - | 264 |

PFAM and IPR designations assigned from the UniProt database. For simplicity, only one representative PFAM and IPR is given for enzymes with more than one PFAM or IPR designation.

Authors selection of representative members and most relevant references.

2. Canonical terpene synthases

To obtain a complete picture of non-canonical TSs, how they are similar to or distinct from canonical TSs in sequence, structure, function, and mechanism, we will first introduce the two classical families of TSs. As canonical TSs have been extensively reviewed, this section will only briefly cover the basics, focusing on how these elegant enzymes create carbocations, what chemical and structural properties help to stabilize these inherently reactive species, and how regio- and stereoselective cyclization is controlled. For a deeper dive into canonical TSs, we direct readers to the exceptional reviews cited here.4–12

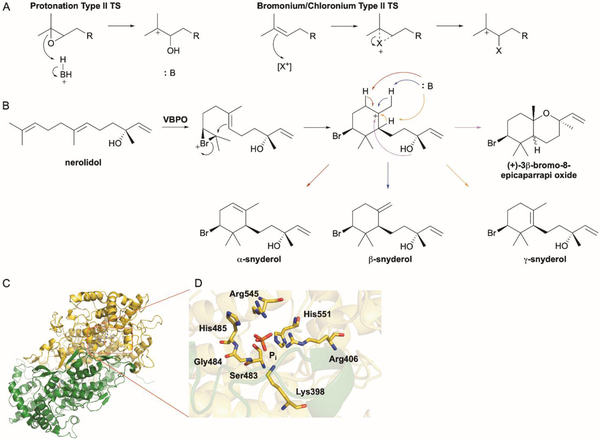

2.1. Mechanisms

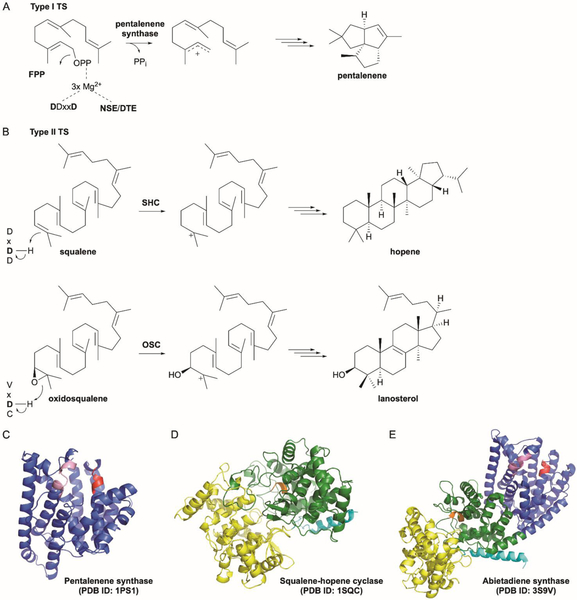

TSs are traditionally divided into two categories depending on how the initial carbocation is generated, i.e., how catalysis is triggered.4,5 TSs are also commonly referred to as terpene cyclases (TCs); however, we prefer to use the term synthases as not all TSs catalyze cyclization reactions. In type I TSs, a diphosphate group is abstracted leaving behind an allylic carbocation on the terpene moiety (Fig. 2A). In type II TSs, a tertiary carbocation is formed through protonation of an alkene or epoxide functional group (Fig. 2B). Since type II TSs do not utilize a diphosphate moiety for activation, their substrates do not need to have diphosphates; alternatively, type II TSs can act on prenyl diphosphates, leaving the diphosphate group intact for an additional reaction with a type I TS. Both types of TSs usually require divalent metal ions, typically Mg2+. Type I enzymes form a trinuclear Mg2+ cluster that binds to the diphosphate and provides the electrophilic driving force for ionization (Fig. 2A).13 Type II enzymes commonly bind one Mg2+ ion to presumably facilitate substrate binding through Coulomb interaction with the negatively charged diphosphate, if one is present.14

Fig. 2.

Canonical terpene synthases. (A) Type I TSs generate allylic carbocations by the ionization of a diphosphate moiety. They commonly possess DDxxD and NSE/DTE motifs that coordinate a trinuclear Mg2+ cluster that binds to the diphosphate and provides the electrophilic driving force for ionization. (B) Type II TSs generate carbocations through protonation of alkene or epoxide functional groups. They commonly possess a DxDD motif with the central Asp acting as the catalytic Brønsted acid. (C) Canonical type I TSs such as pentalenene synthase consist of an α domain (blue). The two Mg2+-binding Asp rich motifs DDxxD and NSE/DTE are colored in red and pink, respectively. (D) Canonical type II TSs such as SHC consist of β (green) and γ (yellow) domains. The Asp rich motif DxDD is colored in orange. The γ domain is an insertion domain between the first and second helices of the β domain. The N-terminal helix of the β domain is colored in cyan. (E) TSs can be present in a variety of domain combinations; bifunctional TSs such as abietadiene synthase possess αβγ structures.

After the carbocation is generated, both type I and type II TSs utilize similar chemical strategies to create extraordinary structural diversity. The overarching mechanistic theme is carbocation stabilization, rearrangement, and quench.4,5 Due to the intrinsic reactivity of the carbocation intermediate, it must first, in most cases, be protected from solvent. The nature of the hydrophobic terpenoid substrate requires most of the active site cavity to be lined with the side chains of hydrophobic amino acids, which also aids to prevent bulk solvent from reaching the carbocation.

Carbocation rearrangements, often occurring in cascading fashion, is a hallmark of most TSs and occur through cation-alkene cyclizations, hydride shifts, and a variety of alkyl shifts including methyl shifts, ring contractions, and ring expansions.4,5 Proton transfers are also proposed to occur in certain cases.15,16 The carbocations, which are most commonly found in their low energy tertiary form,17 are stabilized through various means of charge delocalization including charge-charge, charge-dipole, and charge-quadruple interactions. In many TS active sites, the aromatic side chains of Phe, Tyr, and Trp use π-cation interactions to stabilize the transient cations.5 It is still not entirely clear how TSs precisely control these complex cyclization reactions, but mechanisms including inherent reactivity of the terpenoid substrate,18 active site contour templating (i.e., substrate folding),19 and enzyme induced fits20 are all important factors contributing to the enormous structural and stereochemical diversity of terpenoids.

Completion of the TS reaction requires quenching of the final carbocation. Deprotonation of a neighboring carbon atom affords an alkene while solvent or intramolecular hydroxyl capture gives an alcohol or ether, respectively. If water quenching does occur, the enzyme must carefully control the location and orientation of both the intermediates and water molecule.21 In type II cyclizations, these newly formed alkenes and hydroxyl groups may be used in subsequent type I cyclizations.

2.2. Sequence and structure

Canonical TSs are typified by the presence of highly conserved Asp-rich motifs.5 This fact has been used extensively to identify and confirm the functions of putative TSs from genomes, gene clusters, and sequence databases.22,23 These signature sequence motifs have distinct functions depending on their presence in type I or II TSs.

Type I TSs use two different Asp-rich motifs to bind the trinuclear Mg2+ cluster for diphosphate ionization. Similar to the two metal-binding DDxxD motifs first found in the archetypal trans-prenyltransferase (PT) FPP synthase,24 TSs have DDxxD and (N,D)D(L,I,V)x(S,T)xxxE motifs (bold residues indicate metal ligands) (Fig. 2A and 2C).5 The second motif is commonly referred to as the NSE or DTE motif. While some characterized TSs have slightly modified Asp-rich motifs, type I TSs and the DDxxD and NSE/DTE motifs are typically considered inseparable.

The Asp-rich motifs in type II TSs play an entirely different mechanistic role. The protonation of an alkene or oxirane requires a Brønsted acid and the central Asp in a characteriztic DxDD motif fills that need (Fig. 2B).5,25 The functional requirement of this motif was first identified in the type II tri-TS (TTS) squalene-hopene cyclase (SHC), which initiates cyclization by protonation of a double bond in squalene (Fig. 2B).26,27 Eukaryotic oxidosqualene cyclase (OSC), which protonates a terminal epoxide, carries a less acidic VxDC motif with the central Asp retaining the necessary functionality (Fig. 2B).28 It should be stated that many type II TSs also bind Mg2+ due to their substrates frequently possessing diphosphate moieties;14 however, the Mg2+ ion binds to the diphosphate moiety and not to the Asp-rich motif as in type I TS. Diverging from most type II TSs, the TTSs SHC and OSC do not require a divalent metal ion for activity.27,28

The structures of over 30 TSs from plants, fungi, and bacteria are known.5 Type I TSs adopt an α domain fold, an all α-helical bundle consisting of 10–12 mostly anti-parallel α-helices also known as the “isoprenoid” fold first identified in FPP synthase (FPPS) (Fig. 2C).5,24 It is logical that both PTs and type I TSs adopt the same fold considering that the ionization mechanism is conserved between these two types of isoprenoid enzymes. The hydrophobic active site containing the trinuclear Mg2+ cluster and the conserved DDxxD and NSE/DTE motifs are located in the middle of the α-helical bundle. Type II TSs assume a bi-modal fold consisting of β and γ domains. First seen in SHC and later in human OSC (hOSC), the tertiary structure of βγ is an overall dumbbell shape built with double α-barrels (Fig. 2D).27,29 The type II active site, with its acidic DxDD motif and mostly hydrophobic cavity, sits at the interface of the β and γ domains. Both the α and βγ folds appear to be the result of gene duplication and fusion events as the α domain consists of two ancient 4-helix bundles and the β and γ domains share significant sequence and structural homology with each other, but not with the α domain.30,31

Structurally, both type I and II TSs can be present in a variety of domain combinations consisting of α, β, and γ domains.5,31,32 Consequently, their sequence lengths vary from ~300–900 amino acids. The modularity of type I α and type II βγ folds presented an opportunity for nature to evolve bifunctional TSs consisting of αβγ folds (Fig. 2E). This indeed has been seen and characterized both functionally and structurally.32 It is therefore easy to envisage monofunctional type I and II TSs that adopt mono-, di-, and tri-domain tertiary structures. In fact, type I TSs have been seen to adopt α, αα, αβ, and αβγ folds; type II TSs adopt βγ or αβγ folds.5 As one would expect, the catalytically active domains have the canonical Asp-rich motifs and the non-functional vestigial domains either have mutated active site residues, Mg2+-binding motifs, or collapsed active site cavities.33,34

3. cis-PT-type cyclases

PTs catalyze the attachment of allylic prenyl groups to a variety of acceptors including other prenyl chains, aromatic moieties, amino acids, tRNAs, and proteins. Mechanistically, PTs are very similar to type I TSs and create the electrophilic donor by diphosphate abstraction. Therefore, it should not be surprising that enzymes annotated as PTs based on their primary sequences can perform cyclization reactions after the allylic carbocation is generated.

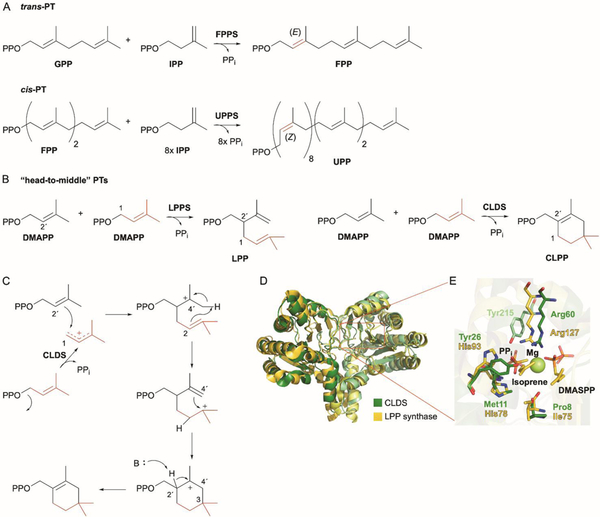

The PTs that catalyze sequential condensations between IPP and allylic diphosphates (e.g., DMAPP, GPP, FPP, GGPP) come in two categories. The trans-prenyl chain elongases, or trans- or (E)-PTs, such as FPPS, produce all-E terpenoid chains; the cis-prenyl chain elongases, or cis- or (Z)-PTs, generate products with one or more Z configured alkenes (Fig. 3A).35 The prototypical cis-PT is undecaprenyl diphosphate (UPP) synthase, an essential enzyme in bacterial peptidoglycan biosynthesis that accepts FPP and uses eight IPPs to biosynthesize the C55 UPP.36

Fig. 3.

CLDS is a cis-prenyltransferase that catalyzes sequential condensation and cyclization reactions. (A) Chain elongation PTs, which use diphosphate ionization to condense two prenyl diphosphates into longer chains, are categorised into trans- or cis-PTs depending on their formation of E or Z double bonds, respectively. The canonical cis-PT UPPS attaches eight molecules of IPP to FPP to yield UPP. (B) LPPSs from plants catalyze “head-to-middle” prenyltransfer using two molecules of DMAPP. CLDS from Streptomyces sp. CL190 catalyzes both “head-to-middle” condensation and cyclization to yield CLPP. (C) The proposed mechanism of CLDS involves C-1–C-2´ bond formation, proton transfer from C-4´ to C-2, cyclization via a C-3–C-4´ bond formation, and deprotonation at C-2´. (D) Superposition of dimeric structures of CLDS (green; PDB ID: 5GUL) and LPPS (yellow; PDB ID: 5HC8). Deep and light colors represent two subunits. (E) Active site comparison of CLDS and LPPS. PPi, isoprene, and DMASPP are shown as sticks; Mg2+ is shown as a limon sphere..

When UPP synthase (UPPS) was discovered and structurally characterized, the lack of sequence and structural similarity to known trans-PTs was a surprise. While UPPS, and cis-PTs in general, all require divalent cations as their trans-PT cousins do, they do not possess the canonical Asp-rich motifs.37 Structurally, UPPS had a completely different fold than the α-domain fold of FPPS and type I TSs.38 UPPS is a homodimer with a central β-sheet core surrounded by five α-helices that forms two binding pockets. In the allylic binding site S1, which consists of a large hydrophobic cleft to house the growing hydrophobic chain, the diphosphate of FPP (or the growing allylic diphosphate) is bound to an Arg residue and a single Mg2+ ion that is coordinated to a highly conserved Asp.35,38 In the nearby homoallylic binding site S2, two additional Arg residues form a positively charged cluster. Additional structure, mutagenesis, and mechanistic studies suggested that FPP first binds to the S1 site through various non-metal-dependent interactions, a Mg∙IPP complex then binds to the S2 site, and the conserved Asp aids in the migration of Mg2+ from IPP to FPP.35,39,40 The presence of Mg2+ then facilitates the ionization of FPP and subsequent C–C bond formation and deprotonation complete one condensation reaction.

In hindsight, the discovery of completely distinct sequences and structures for the nearly identical chemical reactions performed by trans- and cis-PTs, foreshadowed the topic of this review. Nature has evolved an assortment of enzymes, varied in sequence, structure, and mechanism, to create the structural diversity that is known in terpenoid natural products. The first example of a non-canonical TS described in this review is related to the cis-PTs family. In fact, it catalyzes both a PT reaction and a TS-like cyclization.

3.1. Lavanducyanin

Lavanducyanin is a unique phenazine antitumor antibiotic with an N-linked cyclolavandulyl monoterpenoid moiety.41 Although lavanducyanin, which was isolated from Streptomyces sp. CL190, is a member of a small family of other cyclolavandulyl-containing natural products, the biosynthesis of this cyclic monoterpenoid was only recently revealed. Based on known examples of lavandulyl diphosphate (LPP) synthases in plants (Fig. 3B),42,43 the original biosynthetic prediction for cyclolavandulyl diphosphate (CLPP) was two discrete enzymes individually catalyzing “head-to-middle” prenylation (i.e., forming a C-1–C-2´ bond) and cyclization.44

Genome mining within Streptomyces sp. CL190 for any proteins with similarity to either trans- or cis-PTs resulted in ten candidates.44 Seven of the hits showed high homologies to GPP synthase, FPPS, or GGPP synthase, and two of the hits were highly homologous to UPPS. Only one of the cis-PTs, initially named cis-IDS3 and later CLPP synthase (CLDS), showed less than 30% identity to UPPS. It did, however, show 67% identity to a cis-PT responsible for generating the related acyclic C15 sesquilavandulyl skeleton.45 Deletion of the gene encoding cis-IDS3 initially confirmed its essentiality for lavanducyanin biosynthesis, but it was its in vitro characterization that was truly enlightening.44 Incubation of CLDS with DMAPP and Mg2+, along with post-reaction diphosphate cleavage, afforded cyclolavandulol. Thus, CLDS must catalyze both ionization-induced C–C bond formation and cyclization (Fig. 3B).

The mechanism of cyclization was investigated through isotope labeling, mutagenesis, and structural studies.46 Incubation of (C2H3)2-DMAPP with CLDS revealed the migration of one 2H to a methylene in the final product. This isotopic pattern supports that two molecules of DMAPP form CLPP and that an intramolecular proton transfer from C-4´ of one DMAPP to C-2 of the other occurs during cyclization (Fig. 3C). CLDS exhibited the typical homodimeric fold for cis-PTs and showed significant homology to LPP synthase (LPPS) from Lavandula x intermedia with a root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) of 1.53 Å for Cα atom superposition (Fig. 3D).46,47 Most of the active site residues in CLDS and LPPS are identical; however, there are a few key differences in the S1 site (Fig. 3E). The His78 and Arg127 residues proposed to trigger diphosphate ionization in LPPS47 are Met11 and Arg60 in CLDS; only Arg60 is proposed to contact the diphosphate moiety.46 Instead, Tyr26 and Tyr215 from the other subunit appear to form H-bonds with phosphate oxygens and Y26F and Y215F mutants significantly decreased enzyme activity. Docking studies with CLDS and DMAPP, in comparison to the structure of LPPS in complex with a thiolo analogue of DMAPP (DMASPP) suggested that variations in the active site, specifically a bulky Ile residue in LPPS prevents cyclization (Fig. 3E).46 The corresponding residue in CLDS, Pro8, keeps the active site wide enough to permit intramolecular proton transfer and therefore carbocation rearrangement to occur, allowing intermolecular cyclization between the two C5 units. The P8I mutant in CLDS produced both CLPP and LPP. As with other canonical TSs, mutagenesis of other active site residues affected the product profiles.46 Overall, CLDS catalyzes the ionization of one DMAPP molecule for a “head-to-middle” prenylation by simultaneous attack of the C-1 carbocation by the olefin of the other DMAPP molecule. An intermolecular proton transfer from C-4´ to C-2 creates a tertiary-stabilized carbocation on C-3 that is closed by a C-4´-C-3 bond formation, with final deprotonation at C-2´ yielding CLPP (Fig. 3C).46

4. UbiA-type cyclases

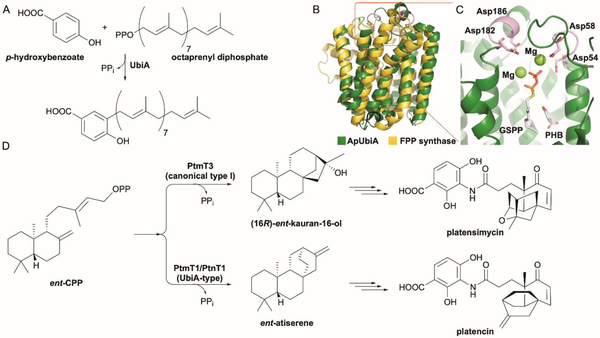

The UbiA superfamily of PTs are a well-known class of membrane-bound enzymes that are involved in a wide variety of cellular processes and diseases.48 The namesake member, UbiA from Escherichia coli, catalyzes the key step of transferring an octaprenyl group to p-hydroxybenzoate in ubiquinone biosynthesis; COQ2 is the eukaryotic counterpart to UbiA (Fig. 4A). These enzymes are also involved in the biosynthesis of menaquinones, hemes, chlorophylls, and other structural lipids.48 Due to prenylation being triggered by diphosphate ionization, UbiA PTs require divalent cations for activity. Although their primary sequences are distinct from canonical type I TSs, most members of the UbiA family have Asp-rich metal-binding motifs (NDxxDxxxD and DxxxD) that are reminiscent of, but not identical to, those found in type I TSs (NSE/DTE and DDxxD). Structurally, in spite of their sequence differences, UbiA PTs are also highly homologous to type I TSs.5 Crystal structures of the archaeal homologues ApUbiA and AfUbiA from Aeropyrum pernix and Achaeoglobus fulgidus, respectively,30,49 unveiled a similar all α-helical fold to that of soluble type I TSs and trans-PTs such as FPPS (Fig. 4B).5,24 The domain containing the Asp-rich motifs implicated in Mg2+-binding forms an extramembrane cap, enclosing the active site and protecting the reactive carbocations from premature water quench (Fig. 4C).30,49

Fig. 4.

UbiA-type cyclases are membrane-bound type I TSs. (A) UbiA is an aromatic PT that catalyzes the attachment of an octaprenyl group to p-hydroxybenzoate. (B) Superposition of ApUbiA (green; PDB ID: 4OD5) and FPPS (yellow; PDB ID: 1RQI). (C) Local view of the active site of ApUbiA. The two Asp-rich motifs, NDxxDxxxD and DxxxD, are shown in pink; geranyl S-thiolodiphosphate (GSPP) and p-hydroxybenzoic acid (PHB) are shown as gray sticks; two Mg2+ ions are shown as limon spheres. (D) The biosynthesis of PTM and PTN diverge at their associated type I TS reactions. In PTM biosynthesis, CPP is converted into (16R)-ent-kauran-16-ol by the canonical type I TS PtmT3. In PTN biosynthesis, a UbiA-like type I TS specifically converts CPP into ent-atiserene.

Through traditional natural products discovery efforts, there were a subset of bacterial and fungal diterpenoids with known structures, but no associated TSs.7,50 A new family of UbiA-type di-TSs (DTSs) were identified as the enzymes capable of constructing a few of these, and other, terpenoid scaffolds. Although a structure of a UbiA-type DTS has not been reported yet, a similar polytopic membrane-embedded α-helical structure with an Asp-rich cap is highly plausible, although the active site contours and residues that control carbocation stabilization, cyclization, and cation quench are likely vastly different. It should be noted that the bacterial DTSs, including the UbiA-type, were recently reviewed.4

4.1. Platencin

Platensimycin (PTM) and platencin (PTN) are antibacterial natural products composed of a diterpene-derived aliphatic cage moiety and a highly functionalized benzoate connected by a flexible amide linker.51,52 The terpenoid moieties are degradation products of ent-kauranol and ent-atiserene, both of which stem from alternative cyclization pathways of the final shared intermediate ent-copalyl diphosphate (ent-CPP).53–56 Initially, ent-CPP was proposed to diverge into ent-kaurene and ent-atiserene by a single DTS,53 as ent-atiserene had been detected as a minor metabolite in a plant ent-kaurene synthase.57 Surprisingly, while the canonical type I DTS PtmT3 was identified and shown to generate (16R)-ent-kauran-16-ol,53,56 a dedicated TS, PtmT1/PtnT1 was responsible for ent-atiserene production (Fig. 4D).53

PtmT1 and PtnT1, nearly identical (96% ID) enzymes from the ptm and ptn gene clusters from Streptomyces platensis spp., respectively, were chosen as candidates for terpene cyclization based on necessity rather than prediction.53 PtmT1/PtnT1 were clearly UbiA-like proteins but did not have the canonical type I TS Asp-rich motifs; the NxxxDxxxD and DxxxD motifs mirrored the Mg2+-binding motifs of the UbiA family. Gene deletion and complementation experiments confirmed that PtmT1/PtnT1 was involved in platencin biosynthesis and this UbiA-type enzyme was proposed to be an ent-atiserene synthase.53 Although PtmT1/PtnT1 has not been biochemically confirmed as an ent-atiserene synthase through in vitro experiments, this initial discovery of a UbiA-type TS expanded the diverse functional capabilities of UbiA PTs and led to additional discoveries of noncanonical TSs.

4.2. Fumagillin

Fumagillin, a meroterpenoid isolated from Aspergillus fumigatus, is an amebicide and anti-infective probably most well-known for its anti-angiogenic activity through covalent inhibition of human methionine aminopeptidase.58,59 Fumagillin is a hybrid natural product consisting of a highly oxygenated sesquiterpenoid moiety and a polyketide-derived decatetraenedioic acid, and an early biosynthetic proposal suggested the terpenoid moiety stems from β-trans-bergamotene (Fig. 5A).60 Although canonical TSs from plants, namely LaBERS and SBS,61,62 make various bergamotene isomers including β-trans-bergamotene, a comparable TS was not recognized in the genome of A. fumigatus.63 The fumagillin biosynthetic gene cluster was finally identified by searching for a highly reducing polyketide synthase (PKS). Inspection of the genetic neighborhood surrounding the pks revealed a UbiA-type TS, named fma-TC, with only 14–19% sequence ID to UbiA, COQ2, and other fungal membrane-bound PTs. A heterologous expression system of fma-TC in yeast and preparation of microsomal fractions confirmed that fma-TC cyclizes FPP into β-trans-bergamotene.63 Like UbiA and other canonical TSs and PTs, fma-TC required Mg2+ for its activity. The revelation of two distinct types of bergamotene synthases from two different kingdoms demonstrates how nature uses convergent evolution of function for TSs.63

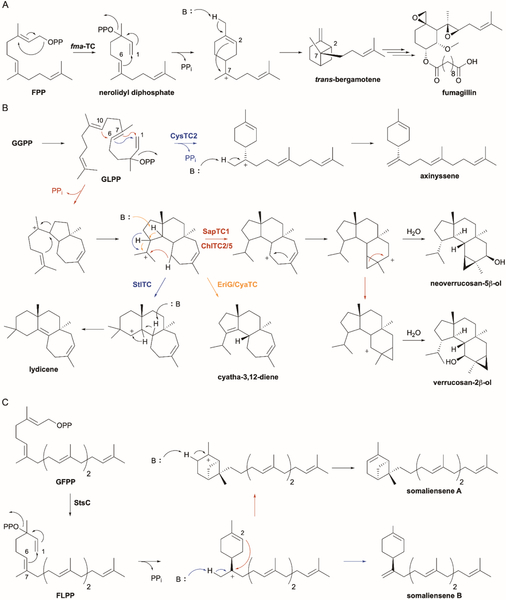

Fig. 5.

UbiA-type cyclases form sesquiterpenoids, diterpenoids, and sesterterpenoids. (A) fma-TC initially isomerises FPP into nerolidyl diphosphate then catalyzes two cyclizations to yield trans-bergamotene, a precursor in fumagillin biosynthesis. (B) The proposed mechanisms of seven new UbiA-type DTSs recently identified in fungi and bacteria. CysTC2 cyclizes GLPP into axinyssene. The other six DTSs, SapTC1, ChlTC2, ChlTC5, EriG, CyaTC, and StlTC all create a common 7-6-5 intermediate through two sequential cyclizations of GLPP followed by a ring expansion and another cyclization. StlTC forms lydicene, EriG/CyaTC give cyatha-3,12-diene, and SapTC1/ChlTC2/ChlTC5 produce two verruconsanols via cyclopropylcarbinyl cation rearrangements. (C) StsC, a UbiA-type sester-TS, catalyzes the formation of the bicyclic somaliensene A and the monocyclic somaliensene B via FLPP and cyclohexenylmethyl carbocationic intermediates.

4.3. Other diterpenoids

Once it was evident that UbiA-type TSs could functionally replace canonical TSs, a larger search within bacteria and fungi was performed to identify new DTSs.50 Genome mining, sequence similarity network, and phylogenetics analysis revealed several subfamilies of potential UbiA-type TSs. The membrane fractions of E. coli expressing representative members were tested for activity using GGPP and Mg2+ and resulted in the identification of seven new cyclases (Fig. 5B). (i) EriG from Hericium erinaceum and CyaTC from Cyathus africanus (68% ID to EriG) are (−)-cyatha-3,12-diene synthases responsible for the first step in erinacine A biosynthesis, a neurite outgrowth promoting agent effective against Alzheimer’s disease;64 (ii) SapTC1, ChlTC2 and ChlTC5 (all ~26% ID to EriG) from the gliding bacteria Saprospira grandis and Chloroflexus aurantiacus, respectively, all produce verrucosan-2β-ol as well as the minor product neoverrucosan-5β-ol; (iii) CysTC2 from Cystobacter violaceus constructs the monocyclic axinyssene, which was previously isolated from a Japanese marine sponge;65 and (iv) StlTC from Streptomyces lydicus converted GGPP into the new diterpene lydicene, which possess an unprecedented carbon skeleton.50 Sequence alignment of the Asp-rich motifs revealed that these seven enzymes have conserved Nxxx(G/A)xxxD and DxxxD motifs. Since the central Asp of the NDxxDxxxD motif of UbiA PTs is missing in these DTSs, its role in Mg2+-binding may not be necessary or is supplemented by another functional group.

Based on previous isotope labeling experiments for cyathane, verrucosane, and neoverrucosane diterpenoids,66–68 a 7-6-5 tricyclic cation was proposed to be a common intermediate in (−)-cyatha-3,12-diene, verrucosan-2β-ol, neoverrucosan-5β-ol, and lydicene cyclization (Fig 5B).50 To account for the Z-configured heptaene in lydicene, isomerization of GGPP to geranyllinalyl diphosphate (GLPP) followed by C-1–C-7 bond formation likely begins the enzymatic cascade. Ring expansion and cyclization gives the common 7-6-5 cationic intermediate. To complete lydicene formation, another ring expansion precedes a sequential 1,2-hydride shift and deprotonation. Verrucosanol would develop via a 1,5-hydride shift and cyclization to form a cyclopropylcarbinyl cation, which would diverge to verrucosan-2β-ol and neoverrucosan-5β-ol by either direct water quench or cyclopropylcarbinyl cation rearrangement followed by water quench, respectively. Simple deprotonation of a bridgehead carbon in the 7-6-5 intermediate would yield (−)-cyatha-3,12-diene. Axinyssene can be simply formed from GGPP by a 1,6-cyclization and methyl deprotonation.50

4.4. Somaliensenes

Recently, a UbiA-type TS found in Streptomyces somaliensis was identified as a membrane-bound sester-TS.69 After several new UbiA-type DTSs were characterized,50 new clusters containing genes encoding for members of the UbiA superfamily were sought after. One such gene cluster, sts, contained a putative TS named StsC that showed moderate (27–42%) identities to bacterial UbiA-type DTSs and possessed the conserved NxxxGxxxD and DxxxD motifs.69 Heterologous expression of stsC in E. coli resulted in the detection and isolation of two sesterterpenoids, somaliensenes A and B, that had structures similar to those of bergamotene and axinyssene (Fig. 5C). When a membrane fraction containing StsC was assayed with FPP, IPP, and a geranylfarnesyl diphosphate (GFPP) synthase, both products were observed; StsC, however, did not utilize GPP, FPP, or GGPP as substrates.69 In analogy to the mechanisms of fma-TC and CysTC2, StsC presumably isomerizes GFPP into farnesyllinalyl diphosphate (FLPP) and catalyzes a 1,6-cyclization to yield a conserved cyclohexenylmethyl carbocation intermediate (Fig. 5C). This intermediate can then undergo sequential 2,7-cyclization and C-6 deprotonation to yield somaliensene A or direct methyl deprotonation to yield somaliensene B. It is unclear whether somaliensenes A and B are the final natural products of the sts gene cluster, although the genetic proximity of a putative SHC homologue suggests the mono- and bicyclic products of StsC are substrates for the biosynthesis of more complex sesterterpenoids.69

5. Methyltransferases

Chemically, the addition of an electron-deficient methyl group to an electron-rich acceptor is equivalent to protonation, where an electron-deficient hydrogen (i.e., proton) is transferred to an acceptor (Fig. 6A). Thus, it is reasonable to consider that methylation can functionally replace protonation-initiated carbocation formation in type II TSs. If the resulting methylated cationic intermediate is favorably folded in a specific and catalytically competent conformation, with an electron-rich double bond in proximity to the carbocation, then cyclization may occur. Methylation-dependent terpene cyclization was proposed over 30 years ago after the structures of the C31 cycloiridials and the C31, C32, and C34 cyclic botryococcenes were discovered;70–73 however, such an enzyme was not identified until 2014.

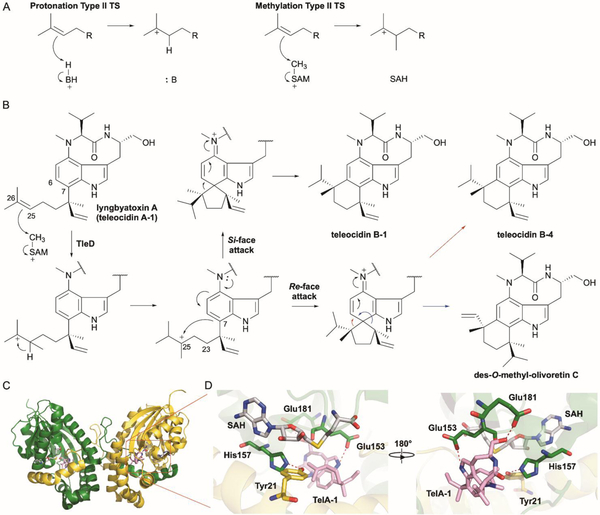

Fig. 6.

Methyltransferases initiate terpene cyclization via a type I-like methylation reaction. (A) SAM-dependent methylation of an alkene is a functional replacement of a type II TS protonation mechanism. (B) Teleocidin biosynthesis requires the bifunctional SAM-dependent MT and TS TleD. Methylation-induced cyclization is completed via either Re- or Si- face attack of the C-25 carbocation by C-7 of indole followed by C–C bond migration to C-6. (C) Overall structure of the TleD dimer (PDB ID: 5GM2). The two subunits are colored in green and yellow; SAH and teleocidin A-1 (TelA-1) are shown as gray and pink sticks, respectively. (D) Local views of the active site and dimer domain-swapped interactions. H-bonds are shown as red dashes.

Methylation, a ubiquitous transformation in nature, is commonly catalyzed by S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferases (MTs).74 These enzymes, which all utilize SAM as the methyl donor and release S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (SAH) as a by-product, direct nucleophilic O, N, C, S, and even halide atoms on acceptor molecules to the electron-deficient methyl group. The electron-rich nature of isoprenoid diphosphates does not require acid/base- or metal-dependent activation to initiate catalysis, and thus fits the recognized ‘proximity and desolvation’ MT mechanism.74 The methyl acceptor, one of the isoprenyl double bonds, is the strongest, most proximal nucleophile to SAM and there is no water present at the donor-acceptor interface. Exclusion, or at least controlled localization, of water in the active sites of canonical TSs is common and prevents premature quenching of the carbocation by water.

The following section describes the two known MTs, TleD and SodC, that catalyze TS reactions. MT-catalyzed cyclizations are, however, not limited to terpenes. SpnF and SpnL, from the biosynthetic pathway of the polyketide spinosyn, resemble SAM-dependent MTs both in sequence and structure, but are proposed to catalyze [4+2] cycloaddition reactions; it is still unknown whether SAM or SAH is required for enzyme activity.75–77 LepI, a SAM-dependent MT-like enzyme, requires SAM, or more specifically its positive charge, to catalyze stereoselective dehydration and three distinct pericyclic reactions in leporin biosynthesis.77,78

It should be noted that SAM-dependent MTs are also capable of methylating linear isoprenoid diphosphates without catalyzing subsequent cyclization as evidenced by the GPP MTs in 2-methylisoborneol (e.g., SCO7701) and benzastatin (BezA) biosynthesis,79–81 the IPP MT Lon23 in longestin biosynthesis,82 and a recently characterized IPP MT from an unknown gene cluster in Streptomyces monomycini.83

5.1. Teleocidins

The discovery of the first cation-induced terpene cyclization reaction catalyzed by a MT was a serendipitous one.84,85 Teleocidins are unique indolactam meroterpenoids isolated from various Streptomyces spp.86,87 These potent protein kinase C activators88 possess a six-membered monoterpenoid moiety fused at both the C-6 and C-7 positions of the indole ring (Fig. 6B). The gene cluster of the structurally related lyngbyatoxins from the cyanobacterium Moorea producens,89 which includes genes encoding an NRPS (ltxA), P450 (ltxB), and an aromatic prenyltransferase (ltxC), suggested enzymatic homologues within the teleocidin gene cluster. The biosynthesis of teleocidin also appeared to require both MT and TS enzymes to fashion the indole-fused methylated terpenoid ring.90 Genome mining of Streptomyces blastmyceticus NBRC 12747 revealed the expected tleABC operon, but no neighboring genes related to a MT or TS.90

In an effort to locate putative MTs in the genome, nine MTs were identified. Six of the nine MTs were found to be co-transcribed with tleC during teleocidin production. Surprisingly, heterologous expression of these individual MTs with the tleABC operon revealed that inclusion of the subsequently named tleD transformed lyngbyatoxin A (teleocidin A-1) into teleocidin B-1, teleocidin B-4, and des-O-methyl-olivoretin C (Fig. 6B); there was no TS needed for cyclization.90 The TleD-dependent TS activity was further confirmed by in vitro enzyme reactions.

The mechanism proposed for cyclization consists of methylation at C-25 (originally C-6 of GPP) resulting in a tertiary-stabilized carbocation at C-26, 1,2-hydride shift producing a C-25 tertiary cation, and electrophilic attack by the carbocation at C-7 on either the Re or Si faces resulting in spiro-fused intermediates. Final C–C bond migration, of either C-19 or C-25 to C-6, results in three distinct products, two of which arise from the Re-face attack (Fig. 6B).84,85,90 Deuterium labeling studies using [6-2H]-GPP confirmed the 1,2-hydride shift while no observed deprotonated or hydroxylated by-products suggested that the hydride shift and cyclizations work in a concerted manner;90 however, the possibility that TleD only catalyzes methylation and the triggered cyclization cascade is non-templated and non-enzymatic cannot be excluded.84

The complex crystal structures of SAH-bound TleD with or without lyngbyatoxin A were determined giving insight into a TS-catalyzing MT.91 TleD shows a typical class I SAM-MTase fold and has the conserved GxGxG SAM-binding motif found in SAM-dependent MTs, but a domain-swapped pattern is observed in its hexameric form via crossover of an additional N-terminal α-helix (Fig. 6C). Tyr21, which forms an H-bond with the imidazole of His157 from the other polypeptide chain, anchors this α-helix to the ‘core SAM-MT fold’ (Fig. 6C). Disruption of this H-bond by Y21F mutation dramatically reduced enzyme activity.91 Lyngbyatoxin A was found buried in a hydrophobic cavity and anchored by H-bonds formed with the side chains of two Glu residues (Fig. 6C). Molecular dynamic simulations suggested that a dihedral angle of 60–90° is preferred for the geranyl chain of C-23–C-24–C-25–C-26, which creates a re-face stereocenter at C-25 and supports the dominant nature of the re-face attack.90,91

TleD shows high structural similarity to the MT-like polyketide cyclase SpnF. They share 33% sequence identities, similar three-dimensional structures with an rmsd of 1.44 Å for Cα atom superposition, and both structures contain the additional N-terminal α-helix anchor.76,91 TleD is also highly homologous (35% sequence identity and 1.31 Å rmsd for Cα) to RebM, a glucosyl O-MT in rebeccamycin biosynthesis; however, RebM does not have known cyclase activity and electron density for its N-terminal region is missing from the crystal structure concealing whether RebM has the additional N-terminal α-helix.91,92

5.2. Sodorifen

Similar to the teleocidins, the biosynthesis of the structurally unique sodorifen was initially puzzling. Sodorifen, a volatile organic compound emitted by the rhizobacterium Serratia plymuthica, exhibits an unusual symmetric bicyclic structure where every carbon has a methylidene or methyl substituent (Fig. 7A).93 This unique structure, as well as inconclusive 13C-labeled precursor feeding results,93 made prediction of the biosynthetic pathway for sodorifen impossible. Subsequent genome and transcriptome analysis of a sodorifen producer and non-producer identified 20 genes that were upregulated in the producer compared with the non-producer.94 Genetic knockout of only one of these genes, SOD_c20750, which encodes a putative TS, abolished sodorifen production.94 This unique sesquiterpene TS (later named SodD95) which has a modified DDxxxDE Asp-rich motif and no NSE/DTE motif,94 is found within a small four-gene operon also comprised of an IPP isomerase (SOD_c20780/sodA), deoxy-xylulose-5-phosphate (DXP) synthase (SOD_c20770/sodB), and a methyltransferase (SOD_c20760/sodC).95,96 The simplicity of the gene cluster, along with the complicated structure of sodorifen, suggested that additional genes elsewhere in the genome were likely required to complete biosynthesis of sodorifen.96 Surprisingly, only the MT SodC/SpFFPMT and TS SodD were necessary to synthesize sodorifen from FPP and SAM.97

Fig. 7.

A bifunctional MT-TS in sodorifen biosynthesis. (A) Sodorifen is biosynthesized by the MT-like TS SodC and the canonical type I TS SodD. Colored dots on atoms represent the biosynthetic origin of the sodorifen scaffold. (B) The proposed mechanism of pre-sodorifen formation by SodC involves methylation at C-10 followed by cyclization, a series of 1,2-hydride and alkyls shifts, and a cyclpropyl-mediated ring contraction.

The identification of pre-sodorifen and pre-sodorifen diphosphate, monocyclic terpenoids that retained the allyl moiety of FPP, from the ΔsodD mutant and in vitro SodC reaction, respectively, revealed that SodC catalyzes both methylation and terpene cyclization.97 SodC did not cyclize FPP in the absence of SAM supporting that methylation precedes and potentially initiates cyclization.

Comprehensive 13C-labeling studies revealed a SAM-derived methyl group at C-10 of FPP and a complicated two-phase cyclization cascade, catalyzed by SodC and SodD, to construct sodorifen from FPP (Fig. 7A).97 Mechanistically, C-10 of FPP is initially methylated by SodC producing a C-11 tertiary carbocation; C-6 then attacks C-11 forming a C–C bond and a C-7 cation. Ring contraction via a cyclopropyl intermediate and ring opening upon re-protonation affords a C-7 cyclopentyl cation, which undergoes sequential 1,2-hydride and 1,2-methyl shifts and deprotonation at C-10 to afford pre-sodorifen diphosphate.97 SodD, the bioinformatically identified TS, completes sodorifen biosynthesis via a type I TS mechanism consisting of a series of 1,2-hydride shifts, C–C bond cleavages, cyclization steps and a final deprotonation step (Fig. 7B). As alternative cyclization pathways cannot be excluded for both SodC and SodD, additional labeling studies are required to support this complex mechanism.97

Using SodC and SodD as queries, at least 28 sod-like gene clusters were identified in other bacteria including Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, and Streptomyces.95,96 There is variation among these 28 gene clusters, including clusters with additional TSs, MTs, and other associated proteins (e.g., Rieske protein), suggesting that sodorifen or related terpenoid scaffolds are modified and will afford novel bacterial terpenoids.95

6. Vanadium haloperoxidases

Halogenated natural products are widely distributed in nature and are especially prevalent in marine eukaryotic organizms.98–100 Most of these natural organohalogens are important signaling or chemical defense molecules and have shown a wide range of biological activities including antibacterial, antifungal, anticancer, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory properties.98–100 Nature has evolved a variety of chemical strategies to install chlorines, bromines, iodines, and fluorines onto natural product scaffolds including hemoenzymes, metalloenzymes, flavoenzymes, SAM-dependent enzymes, and methyl halide transferases.101,102

Vanadium-dependent haloperoxidases (VHPOs), first isolated and characterized in the brown alga Ascophyllum nodosum103 but are now known to be present in all major classes of marine algae, lichen, fungi, bacteria, and cyanobacteria, contain a vanadate prosthetic group and catalyze the oxidation of halides with hydrogen peroxide. VHPOs have been extensively reviewed over the last 15 years.104–108 VHPOs, which are classified according to the most electronegative halogen oxidized, create the chemical equivalent of an electrophilic halide (X+) by performing a two-electron oxidation of a halide ion (X−). In a second step, an electrophilic attack of the X+-like intermediate on an electron-rich molecule results in halogenation. The vanadate-binding site is conserved in all known VHPOs and is composed of a trigonal bipyramidal V(V) ion ligated to an axial His with the three equatorial vanadate oxygens H-bonded to conserved residues; the other axial position is occupied by a water molecule until hydrogen peroxide binds. The vanadium center does not undergo changes in its oxidation state and therefore does not need to be reduced for activity or suffer from oxidative inactivation. The overall stoichiometry of VHPOs requires one halogenated product per one equivalent of hydrogen peroxide consumed. There are two major categories of VHPOs: VHPOs that generate diffusible hypohalous acid, which perform non-stereoselective halogenations outside of the VHPO active site, and VHPOs that perform enzyme-directed regio- and stereoselective halogenations via halonium ions.109–111

A subfamily of VHPOs was found to not only introduce halides into terpenoid substrates, but to use this mechanism to initiate regio- and stereoselective cyclization reactions. In a manner similar to type II TSs like OSC, chlorination or bromination of terpenoid alkenes produce halocarbenium ions that resemble oxirane moieties (Fig. 8A). The following section describes these VHPO cyclases, chronologically the first identified family of non-canonical TSs.

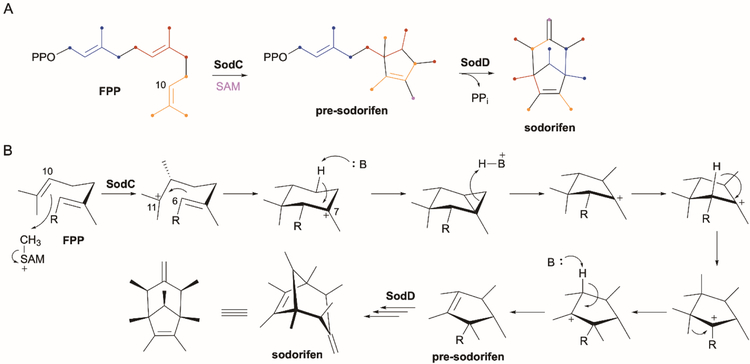

Fig. 8.

Vanadium haloperoxidases initiate terpene cyclization via a type II-like epoxide protonation reaction. (A) Halogenation and formation of an electrophilic bromonium or chloronium ion is a functional replacement of a type II TS protonation mechanism. (B) VBPOs from marine red algae brominate the terminal olefin of nerolidol and facilitate cyclization to form the snyderols and related compounds. (C) Overall structure of the CVBPO dimer (PDB ID: 1QHB). The two subunits are colored in green and yellow; active site residues and phosphate are shown as sticks. (D) Local view of the active site.

6.1. Snyderols

Marine red algae produce a variety of halogenated natural products including brominated cyclic terpenoids.112 The position of the bromine on the sesquiterpenoid snyderols and (+)-3β-bromo-8-epicaparrapi oxides, on a carbon adjacent to a gem dimethyl substituted carbon, suggested that intramolecular cyclization may occur after halogenation of the terminal alkene.108 Vanadium-dependent bromoperoxidases (VBPOs) isolated from Corallina officinalis, Plocamium cartilagineum, and Laurencia pacifica were shown to catalyze bromonium ion-induced cyclization of both acyclic mono- and sesquiterpenes.113,114 Asymmetric bromination and cyclization of (E)-(+)-nerolidol afforded the α-, β-, and γ-snyderols, as well as diastereomers of the bicyclic (+)-3β-bromo-8-epicaparrapi oxide (Fig. 8B).114 The proposed mechanism follows a type II-like TS mechanism. Bromination of the terminal olefin produces a bromonium-nerolidol adduct that is subsequently attacked by the neighboring internal olefin and results in a tertiary stabilized cyclohexyl carbocation. Three different elimination reactions give the three snyderols whereas intramolecular nucleophilic attack of the hydroxyl group would give the bicyclic products. The exact form of the oxidized bromine intermediate is unknown but hypobromous acid is one possibility.115

A look at the crystal structure of the VBPO from C. officinalis (CVBPO), which was determined before the biochemical characterization of the cyclization activity, gives insight into the metal-binding site, active site cavity, and overall structure of this unique TS.116 The overall structure and dimer organization of CVBPO are similar (1.25 Å rmsd for Cα) to those of VBPO from A. nodosum (Fig. 8C).117 Reminiscent of an Asp-rich motif sitting at the bottom of the active site cavity in certain type II TSs,55 the vanadium-binding site of CVBPO is located on the bottom of a deep interfacial cavity (Fig. 8D).116 Several hydrophobic patches and charged residues line the active site cleft, providing an ideal environment for electrophilic attack of the Br+ ion and its imminent cyclization. The active site residues and contour of CVBPO is different than other structurally characterized, cyclization-inept algal VBPOs reflecting the differences in substrate recognition.

6.2. Napyradiomycins

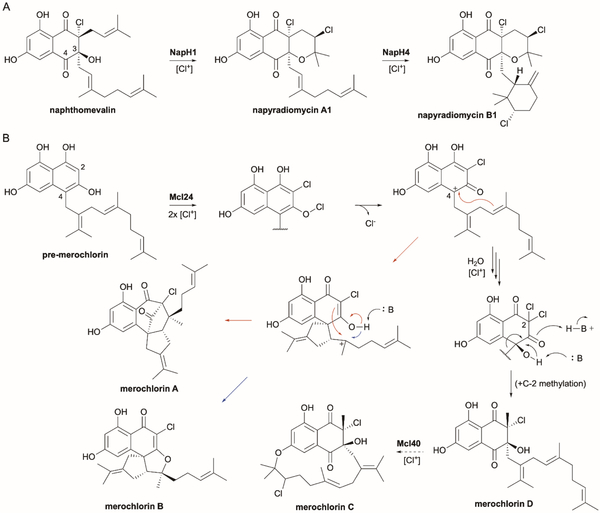

Napyradiomycins are natural products of mixed polyketide and terpenoid origin. These naphthoquinone-based meroterpenoids were first isolated in the mid 1980s118,119 and are known for their broad-spectrum antimicrobial, anticancer, and antiogenic activities.120–122 The identification of the napyradiomycin biosynthetic gene cluster in Streptomyces aculeolatus NRRL 18422 and Streptomyces sp. CNQ-525 and its heterologous expression in Streptomyces albus clearly indicated that three vanadium-dependent chloroperoxidases (VCPOs) were essential for biosynthesis.123 Over the last eight years, in vitro characterizations of NapH1, NapH3, and NapH4 have revealed that (i) NapH3 mediates a C-4-to-C-3 α-hydroxyketone rearrangement (vida infra) of the geranyl moiety on a diprenylated 1,3,6,8-tetrahydroxynaphthalene (THN) to afford naphthomevalin;110,124 (ii) NapH1 facilitates chloronium-induced cyclization of the dimethylallyl moiety on naphthomevalin to form napyradiomycin A1 (Fig. 9A);110,125 (iii) NapH4 facilitates a similar chloronium-induced cyclization of the geranyl moiety on napyradiomycin A1 to yield napyradiomycin B1 (Fig. 9A);109 and (iv) both NapH1 and NapH4, homologues with 72% sequence identity, also simply catalyze monochlorination on 4-geranyl-THN.109 Both NapH1 and NapH4 are VCPOs that must selectively bind their substrates to ensure regio- and enantioselective halogenations that facilitate intramolecular cyclization. While strategic site-directed mutagenesis has revealed catalytically important residues and a crystal structure of NapH1 with and without vanadate was determined,108,125 it is still unclear how this VCPO binds its substrate, directs halogen delivery to the alkene, and supports cyclization.

Fig. 9.

Vanadium haloperoxidases in napyradiomycin and merochlorin biosynthesis. (A) NapH1 and NapH4 are VCPOs that form chloronium ions to initiate terpene cyclization in the biosynthesis of napyradiomycins. (B) In merochlorin biosynthesis, the VCPO Mcl24 forms a hypochlorite intermediate that is transformed into a benzylic cation by loss of Cl−. Mcl24 then catalyzes two sequential cyclizations with distinct second steps to yield merochlorins A or B. In basic conditions, Mcl24 catalyzes α-hydroxyketone rearrangement to give merochlorin D, which is further cyclized by the VCPO Mcl40 to afford merochlorin C.

6.3. Merochlorins

The merochlorins, first isolated from the marine sedimental Streptomyces sp. CNH-189 and another family of antibiotic meroterpenoids with unusual structures, also require VHPO-catalyzed cyclization mechanisms.126–128 The associated biosynthetic gene cluster for merochlorins A–D revealed two putative VCPOs, Mcl24 and Mcl40, that are highly homologous to NapH1 and NapH4.127 Initial heterologous expression studies confirmed that both Mcl24 and Mcl40 were required for general merochlorin biosynthesis with Mcl40 specifically responsible for generating the 15-membered cyclic ether ring in merochlorin C.127 Mcl40 is proposed to perform a chloronium-assisted macrocyclization of merochlorin D to merochlorin C (Fig. 9B); unfortunately, Mcl40 has not yet been further characterized as soluble protein has been unobtainable.108

Preliminary investigation of Mcl24 led to the proposal of an elegant enzymatic cascade for the formation of merochlorins A and B (Fig. 9B).45,129 Incubation of pre-merochlorin with Mcl24 gave both merochlorins A and B.129 The mechanistic rationale for the generation of two distinct dearomatized and cyclization products was proposed as (i) selective chlorination at C-2 of pre-merochlorin by the activated chloronium species, (ii) a second chlorination event to produce an aromatic hypochlorite, which upon loss of chloride would give the benzylic C-4 carbocation, and (iii) cation-induced terpene cyclizations. Interestingly, Mcl24 was also found to have an alternative reaction pathway when incubated at a higher pH (8.0 compared to 6.5).124 If the benzylic cation is trapped by water to give an α-hydroxyketone, a second chlorination at C-2 creates a gem-dichloride that could undergo C-4-to-C-3 α-hydroxyketone rearrangement to afford the 2,2-dichloro-3-prenyl-THN product. The addition of water was confirmed by H218O labeling. This novel activity was the first halogen-mediated α-hydroxyketone rearrangement in nature and parallel experiments with NapH3, a VCPO that appears to have lost its haloperoxidase activity, revealed a requirement for di-substitution at C-2.124 Although much remains to be clarified regarding the structure and mechanism of the VCPOs in merochlorin biosynthesis, the revelation that VCPOs can catalyze such diverse terpene cyclization and rearrangement reactions has led to similar mechanistic proposals for other meroterpenoids. Recently, VCPOs MarH1 and MarH3 were shown to catalyze α-hydroxyketone rearrangements in the biosynthesis of naphterpins and marinones.130

7. Cytochromes P450

As described throughout this review, carbocations are typically formed by one of two simple mechanisms, ionization of a leaving group or electrophilic addition to a π-bond. Cytochromes P450 (P450s) are not only capable of generating possible precursors for type II (via epoxidation of a double bond) mechanisms, they provide an alternative one-electron process for carbocation formation.

P450s are a superfamily of heme- and oxygen-dependent enzymes that utilize a complex catalytic mechanism to catalyze C–H activation reactions.131–134 Although hydroxylations are the prototypical transformations of P450s, their ability to create and control radical species on small molecule substrates provides a plethora of enzymatic functionalities that are particularly evident in natural products biosynthesis.135–138 In the currently accepted P450 catalytic cycle, a highly reactive oxo-ferryl (FeIV=O) π-cation porphyrin radical, commonly called Compound I, is initially generated. During hydroxylation, Compound I abstracts a hydrogen from the substrate and the resultant hydroxyl radical species rapidly rebounds to the newly formed substrate radical. If the rate of oxygen rebound can be diminished enough, a kinetically competitive electron transfer to the radical center would yield a carbocation.139–141 Thus, enzymatic carbocation formation via a sequential radical generation–electron transfer reaction is feasible.

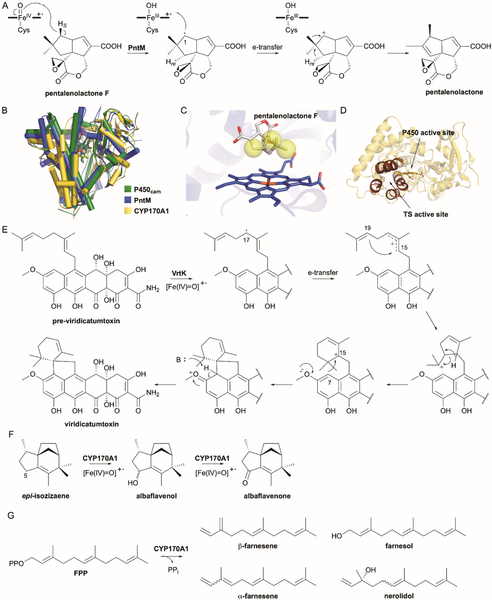

The following section describes the three known P450s that catalyze TS-like reactions. Two of these P450s, PntM and VrtK, are proposed to form carbocations after substrate radical formation. The third, CYP170A1, is a unique P450 that has two distinct and functional active sites.

7.1. Pentalenolactone

During biosynthetic studies of pentalenolactone (PNT), a common sesquiterpenoid antibiotic found in Streptomyces spp., a P450 was found to catalyze the oxidative rearrangement of PNT F to PNT.142 In vivo and in vitro experiments revealed that PntM and PenM, two homologous P450s from different Streptomyces spp., were shown to be responsible for this transformation.142 This realization presented an intriguing mechanistic puzzle:143 neopentyl radicals, such as the one predicted to be generated at C-1 by PntM/PenM, do not undergo skeletal rearrangement,144 whereas neopentyl cations do.145 Therefore, PntM/PenM appeared to exclusively catalyze a carbocation-based oxidative rearrangement, a previously unprecedented biochemical reaction for a P450 (Fig. 10A).142

Fig. 10.

Cytochromes P450 generate carbocations via one-electron transfers or type I ionization. (A) PntM catalyzes a TS-like rearrangement of PNT F to yield PNT by generating a carbocation from a radical via a one-electron transfer. (B) Superposition of the overall structures of P450cam (green; CYP101A1; PDB ID: 2CPP), PntM (blue; PDB ID: 5L1O), and CYP170A1 (yellow; PDB ID: 3EL3). The heme groups are shown as sticks. (C) Local view of the PntM active site. PNT F is shown as gray sticks; yellow spheres depict steric hindrance. (D) Overall structure of CYP170A1 showing the TS active site location in comparison to the P450 active site. The four helices that form the TS active site are colored in brown. (E) A similar one-electron transfer is proposed for the cyclization of pre-viridicatumtoxin by VrtK in viridcatumtoxin biosynthesis. The proposed mechanism includes ring expansion and electrophilic substitution after initial cyclization. (F) The primary activity of CYP170A1 is C-5 oxidation in albaflavenone biosynthesis. (G) CYP170A1 shows moonlighting activity in a second TS-like active site. Farnesol, nerolidol, and farnesene isomers are generated via a type I TS reaction when CYP170A1 is incubated with FPP.

A detailed mechanistic and structural study of PntM concluded that carbocation formation by PntM arises through electron transfer from the transient C-1 radical to the heme Fe3+–OH radical cation (Fig. 10A).143 Several pieces of experimental evidence support this hypothesis. (i) Crystal structures of substrate-free PntM and several complexed structures ruled out any unusual features of the P450 overall structure, active site, heme cofactor, or substrate binding and revealed protein-ligand interactions with P450-unique residues Phe232, Met77, and Met81 (Fig. 10B); however, mutagenesis and kinetics experiments established that these residues do not provide special orbital stabilization of the cationic intermediates.143 (ii) Although it was speculated that the conjugated alkene of PNT F may provide stabilization of the C-1 carbocation, and therefore a reduced substrate analogue may simply be hydroxylated by PntM, 6,7-dihydro-PNT F was not hydroxylated or rearranged by PntM, suggesting that the C-1 cation may not be anchimerically stabilized by the 6,7-double bond of PNT F.143 Recent quantum mechanical/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) studies suggested that 6,7-dihydro-PNT had a similar reaction energy profile to that of PNT F and is likely not a productive substrate due to inherent substrate binding or binding-induced conformational changes.146 (iii) Previously isolated congeners and isotope labeling experiments147–149 suggested that a transient neopentyl cation is formed. While PNT formation could be achieved through a TS-like successive syn 1,2-methyl migration and anti deprotonation of H-3re, competing deprotonation of the neopentyl carbocation or other derived cationic intermediates would give PNT A, B, or P.142 (iv) The rate constant for oxygen rebound is ~1010–1011 s−1;150,151 electron transfer from alkyl carbon radicals to the radical heme species has been assigned a second order rate constant of ~108 M−1 s−1.139,152 Significantly, oxygen rebound is extremely sensitive to steric hindrance whereas electron transfer is unaffected by neighboring sterics.152 The si face of C-1 in PNT F is buttressed on both sides by neighboring methyl and vinylidene groups (Fig. 10C). This natural steric hindrance likely causes extreme suppression of oxygen rebound (at least >104) and allows the typically kinetically silent electron transfer to occur, affording the C-1 carbocation.143 QM/MM calculations supported electron transfer due to unfavorable geometry, although the timing of electron transfer remains unclear.146 (v) Finally, supporting the steric hindrance model, a common shunt metabolite from PNT biosynthesis, pentalenic acid, is the result of CYP105D7 hydrogen abstraction and oxygen rebound at C-1.153 Oxygen rebound is possible for CYP105D7 due to the reduced degree of steric hindrance (Fig. 10C), i.e., neighboring methyl and hydrogen, by its abstraction of H-1re of 1-deoxypentalenic acid.143

7.2. Viridicatumtoxin

Viridicatumtoxin (VRT) is a tetracycline-like meroterpenoid antibiotic produced by Penicillium aethiopicum.154 Its unique, fused spirobicyclic ring system has inspired both enzymologists and synthetic chemists.155,156 After the vrt gene cluster was identified157 and the aromatic prenyltransferase VrtC was found to attach GPP to the naphthacene core to afford pre-VRT,158 the enzymatic cyclization of the geranyl moiety was a mystery. In the absence of any identifiable TS-encoding genes within the gene cluster, two P450s were selected as candidates for geranyl cyclization. P450-mediated carbocation formation had previously been proposed to occur in lovastatin biosynthesis via a type I-like hydroxylation, protonation, and dehydration sequence.159

VrtK was identified as the sole enzyme that catalyzes both cyclization of the geranyl moiety and Friedel-Crafts alkylation on the naphthacene core.160 Deletion of vrtK in P. aethiopicum accumulated pre-VRT while heterologous biotransformation of VrtK with pre-VRT afforded VRT.160 Following the prototypical hydroxylation mechanism of P450s, terpene cyclization may be initiated through hydroxylation of C-17 (originally C-4 of GPP); however, since no C-17 hydroxylated intermediates were seen during biotransformation, a different mechanism was proposed. Similar to the PntM/PenM mechanism, hydrogen abstraction and electron transfer may form the allylic-stabilized carbocation (Fig. 10E). While a [13C,2H]-mevalonate labeling study revealed the existence of a 1,3-hydride shift and led to a carbocation mechanistic proposal,161 recent QM modeling revised the cyclization mechanism to avoid a secondary carbocation intermediate.160 The spirobicyclic product is formed via C–C bond formation between C-15 and C-19 resulting in a tertiary carbocation at C-20, concerted 1,2-alkyl and 1,3-hydride shifts moving the cation to C-15, and Friedel-Crafts alkylation at C-7 of the VRT core.160 Since the proposed pathway does not require any conformational changes of the intermediates, VrtK may simply act as a molecular chaperone to structurally pre-organize pre-VRT to allow its inherent reactivity to catalyze cyclization and alkylation after the C-17 carbocation is formed (Fig. 10E).160

Both PntM/PenM and VrtK may be classified as type II-like TSs since the enzymes act on diphosphate-free substrates without the use of ionization to initiate the reaction. However, type II TSs typically generate their carbocation through protonation of a double bond or incipient double bond (i.e., epoxide). These two enzymes are unique P450s that generate a carbocation by a third mechanism, hydrogen abstraction and subsequent electron transfer, thereby initiating rearrangement and/or cyclization reactions. Once again, nature proves its extraordinary capacity to evolve a system beyond its canonical reactivity to produce a single biosynthetic product. Even with the ingenious use of radical clocks to probe the presence of cationic intermediates in P450 reactions, only 2–15% of total enzymatic products were found to be cationic-derived.140

7.3. Farnesene

Albaflavenone, a volatile sesquiterpenoid antibiotic partially responsible for the earthy odour of soil, is produced by the many Streptomyces spp.162–165 Its short biosynthesis consists of cyclization of FPP by the type I TS epi-isozizaene synthase (EIZS, SCO5222) and two sequential, and seemingly non-stereospecific, allylic oxidations by CYP170A1 (SCO5223) to yield albaflavenone (Fig. 10F).166,167 A one-pot enzymatic reaction of FPP, EIZS, and CYP170A1 afforded not only the expected albaflavenone product and albaflavenol intermediates, but also three farnesene isomers.168 Production of these farnesene isomers were found to be independent of EIZS activity and NADPH, suggesting that CYP170A1 had intrinsic TS activity that was distinct from its heme- and O2-dependent monooxygenase activity. In fact, incubation of FPP with CYP170A1 alone yielded at least five sesquiterpene products: (E)-β-farnesene, (3E,6E)-α-farnesene, (3Z,6E)-α-farnesene, nerolidol, and farnesol (Fig. 10G); farnesene was not further transformed by CYP170A1, even in the presence of NADPH and its electron partners.168

The bifunctional nature of CYP170A1 implicated that CYP170A1 possesses a second active site for TS activity, which is distinct from the normal P450 active site. The crystal structure of CYP170A1, which displayed a typical prism-like P450 structure consistent with its monooxygenation activity, also revealed a novel TS-like active site (Fig 10B).168 The TS active site of CYP170A1 shares a common α-helical barrel with other known type I TSs except that it only contains four α-helices rather than the typical six (Fig. 10D).5 It also possesses the canonical type I Mg2+-binding DDxxD and DTE motifs, although the distance between these motifs in the primary sequence is understandably very short. Mutagenesis of the DDxxD motif resulted in loss of farnesene activity but did not affect monooxygenation,168 confirming the distinct, moonlighting activity of CYP170A1.

CYP170A1 is an unusual bifunctional enzyme, capable of catalyzing two very distinct reactions with two distinct substrates in different active sites. Moonlighting activity is rare, known only in select enzyme families including a few human CYPs.169,170 The secondary activity of CYP170A1 clearly mimics a type I TS mechanism, utilizing a similar local α-helical structure with canonical Asp-rich motifs to bind Mg2+ and facilitate ionization of the diphosphate. Although it is unclear if the TS activity of CYP170A1 is biologically relevant, or how and when the albaflavenone producer would regulate farnesene production, the sequence and structure of CYP170A1 evidently evolved in this fashion for a purpose. Homologues of CYP170A1, such as CYP170B1 from Streptomyces albus, that are able to convert epi-isozizaene into albaflavenone do not have any TS activity with FPP.163 Analysis of the NSE/DTE and DDxxD motifs from 215 of the closest homologues of CYP170A1 (collected from first neighbor nodes in a P450 sequence similarity network135) show that the majority of CYP170 members retain the DTE and D(D/E)xx(D/E) motif required for farnesene production; CYP170B1 has a DST and DGxxR motif.

8. Flavin-dependent oxidocyclases

Flavoproteins are widely distributed in nature and are involved in a myriad of biological processes and natural product biosynthetic pathways. The tricyclic isoalloxazine ring system of flavins provide redox versatility; both one-electron and two-electron oxidative reactions are kinetically and thermodynamically accessible.171 While flavin-dependent monooxygenases (FMOs) are widespread and well-known for their numerous oxidative capabilities,171 a subset of flavoproteins covalently bind oxidized flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and utilize it as an electron sink to capture hydrides ejected by substrates.77 In most instances of the latter case, hydride addition occurs at N-5 of the isoalloxazine ring with concomitant protonation at N-1 yielding FADH2. To resume catalysis, FADH2 is regenerated to FAD by transfer of its newly acquired hydride to another co-substrate, typically molecular oxygen.77 The oxidation of the substrate, by ejection of a hydride, provides access to a new electrophilic carbon that is subject to nucleophilic attack.

The following section details two flavin-dependent oxidocyclases responsible for triggering the cyclization of meroterpenoids. In xiamycin biosynthesis, flavin activates molecular oxygen; in the cannabinoid system, flavin acts as a hydride acceptor.

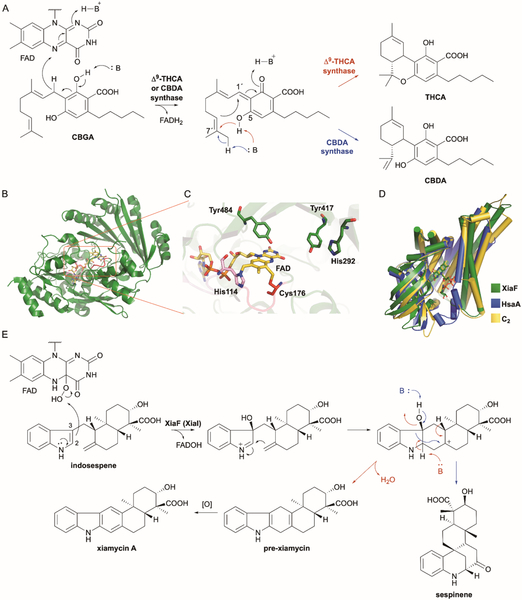

8.1. Cannabinoids

Cannabinoids are hybrid natural products consisting of alkylresorcinol and monoterpene moieties. Traditionally associated with Cannabis sativa due to their overwhelming presence in the flowering plants, there are ~150 known phytocannabinoids.172 Although best known for the psychotropic effects of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), several other less or non-psychoactive cannabinoids including cannabidiol (CBD), the carboxylated analogue cannabidiolic acid (CBDA, or pre-CBD), and cannabichromene (CBC) retain pharmacological effects and are drug leads for a variety of ailments including anxiety, pain, epilepsy, diabetes, inflammation, and cancer.173 THC, which only accumulates at low levels in cannabis, is derived from Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) via a non-enzymatic decarboxylation reaction either in the plant or when heated.172 Although cannabinoids have been long known and studied, the terpene cyclization biosynthetic step was only recently revealed to be an FAD-dependent oxidative cyclization.

Prior to the discovery of Δ9-THCA synthase (previously named Δ1-THCA synthase), it was commonly proposed that THCA was a product of isomerization of CBDA.174 However, THCA was found to be directly formed from cannbigerolic acid (CBGA) by a unique TS-like enzyme that did not require a divalent metal ion to mediate oxidative cyclization (Fig. 11A).174 After the gene encoding Δ9-THCA synthase was cloned from C. sativa, it was clear that Δ9-THCA synthase had no sequence homology to TSs and did not possess the canonical Asp-rich motifs; it was, however homologous to berberine bridge enzyme (BBE, 40% identity) and was covalently bound to a stoichiometric amount of FAD.175 Mutagenesis of His114 in the R/KxxGH motif found in other FAD-binding proteins resulted in loss of bound FAD and its oxygen-dependent activity.175 After the crystal structure of Δ9-THCA synthase was determined, FAD was also found to not only covalently bind to His114, but also to Cys176 in a CxxV/L/IG motif (Fig. 11B),176 as in the BBE family of flavoproteins.177

Fig. 11.

FAD oxidocyclases cyclize terpenoids using two different mechanisms. (A) The cannabinoids Δ9-THCA and CBDA are formed by FAD-dependent oxidative cyclization of CBGA. A hydride from C-1´ of CBGA is ejected onto FAD setting up C-6´–C-1´ cyclization. The isomerization of the C-2´–C-3´ E-alkene in CBGA to a Z-alkene in THCA and CBDA is still mechanistically unknown. (B) Overall structure of Δ9-THCA synthase (PDB ID: 3VTE). Two conserved sequence motifs R/KxxGH and CxxV/L/IG are colored in pink and red, respectively. (C) Local view of the Δ9-THCA synthase active site. FAD, shown as yellow sticks, is covalently bound to His114 and Cys176. Residues Tyr484, Tyr417, and His292 are all implicated in the reaction mechanism. (D) Superposition of the overall structures of XiaF (green; PDB ID: 5MR6), HsaA (blue; PDB ID: 3AFF), and C2 (yellow; PDB ID: 2JBS). FAD in XiaF and FMN in C2 are shown as sticks. (E) In xiamycin A biosynthesis, the FMO XiaF (XiaI) activates molecular oxygen with FAD and cryptically hydroxylates the C-3 of indole, facilitating exo-methylene attack of the resulting iminium cation. Dehydration and deprotonation can either yield pre-xiamycin or sespinene.

The titular member of the BBE family, BBE or (S)-reticuline oxidase, is responsible for catalyzing the conversion of the alkaloid (S)-reticuline into (S)-scoulerine via an oxidative ring closure in the California poppy (Eschscholzia californica).177 In a concerted fashion, FAD accepts a hydride from the N-methyl group of (S)-reticuline while Glu417 presumably deprotonates the phenolic OH and triggers a Friedel-Crafts-like alkylation reaction.178 Although there are sequence and structural differences distinguishing members of the BBE family from other flavoproteins, the key structural feature of the BBE family is an unusual bi-covalent attachment of FAD. Two sequence motifs, R/KxxGH and CxxV/L/IG, provide the His and Cys residues that link to the 8α and 6 positions, respectively, of the isoalloxazine ring.177 Due to their unique FAD-binding mode and their unprecedented reaction mechanism, interest in the family of BBE-like flavoproteins continues to grow.177

Based on a combination of evidence including the structure of Δ9-THCA synthase and mutational analysis, a mechanism was proposed (Fig. 11A). A hydride is ejected from the benzylic position of CBGA, which may be assisted by deprotonation of a phenolic OH, to form the strongly electrophilic conjugated dienone. The hydride is transferred to the N-5 position of the isoalloxazine ring of FAD. Cyclization, in perhaps a single transition state, then occurs between the deprotonated hydroxyl of the phenolic C-5 and C-7´ and between C-6´ and C-1´ to yield the fused tricyclic core of THCA.77,176 Due to the absolute necessity of the hydroxyl group of Tyr484 for cyclization, Tyr484 likely acts as a general base for phenolic deprotonation (Fig. 11C).176 Also, based on decreased activity in the corresponding mutants, His292 and Tyr417 appear to play a role in the reaction mechanism (Fig. 11C); although it is unclear whether they are involved in substrate binding, catalysis, or both.176 Finally, FAD would be regenerated through hydride transfer from FADH2 to molecular oxygen, resulting in hydrogen peroxide formation. The mechanism is not fully understood, however, as the Z-configured alkene in THCA originates from the E-configured C-2´–C-3´ alkene in CBGA.

Similarly, CBDA synthase converts CBGA into CBDA (Fig. 11A). CBDA synthase has 84% sequence identity to Δ9-THCA synthase, possesses both the His (R/KxxGH) and Cys (CxVS) residues for bi-covalently binding FAD, and was shown to absolutely require His114 for FAD binding and activity.179,180 Mechanistically, CBDA synthase would follow the same oxidative activation and hydride transfer of Δ9-THCA synthase, but deprotonation from the terminal methyl group of C-8´, rather than the hydroxyl on C-5, would divert product formation to CBDA (Fig. 11A).

8.2. Xiamycin

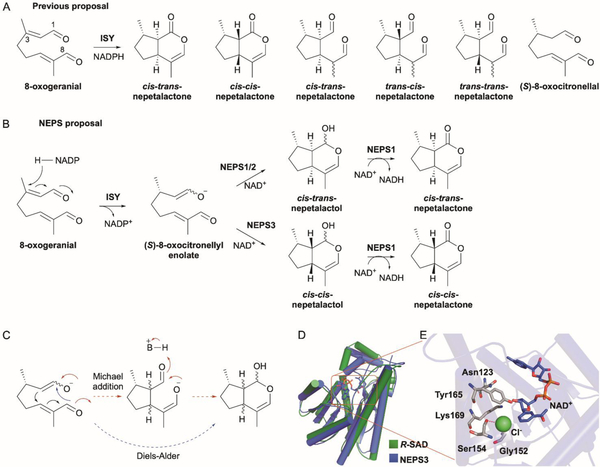

Although indole terpene alkaloids are very common in plants and fungi, they are rare bacterial natural products. The xiamycin family of indolosesquiterpenoids is an example of plant-like terpenoids produced in bacteria and exhibit a wide range of biological activities.181–184 Xiamycins, initially isolated from the mangrove endophyte Streptomyces sp. GT2002/1503,182 are pentacyclic alkaloids that were proposed to be biosynthesized through 3-farnesylindole and the seco intermediate indosespene.184,185 When two xiamycin gene clusters were simultaneously identified, they were both found to encode enzymes that were responsible for two distinct cyclization reactions.184,185 An integral membrane protein was found to first form the decalin system of indosespene (vide infra); after an unrelated six-electron oxidation of a methyl group to a carboxylic acid, the indosespene skeleton is further cyclized by an FMO into the carbazole ring system of xiamycin.184,185