Abstract

Introduction: Chemokines play important roles in inflammation and in immune responses. This article will discuss the current literature on the C–C chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5), and whether it is a therapeutic target in the context of various allergic, autoimmune or infectious diseases.

Areas covered: Small-molecule inhibitors, chemokine and chemokine receptor-deficient mice, antibodies and modified chemokines are the current tools available for CCL5 research, and there are several ongoing clinical trials targeting the CCL5 receptors, CCR1, CCR3 and CCR5. There are fewer studies specifically targeting the chemokine itself and clinical studies with anti-CCL5 antibodies are still to be carried out.

Expert opinion: Although clinical trials are strongly biased toward HIV treatment and prevention with blockers of CCR5, the therapeutic potential for CCL5 and its receptors in other diseases is relevant. Overall, it is not likely that specific targeting of CCL5 will result in new adjunct strategies for the treatment of infectious diseases with a major inflammatory component. However, targeting CCL5 could result in novel therapies for chronic inflammatory diseases, where it may decrease inflammatory responses and fibrosis, and certain solid tumors, where it may have a role in angiogenesis.

Keywords: CCL5, disease pathogenesis, infection, inflammation, RANTES

1. Introduction

Inflammation is the reaction of vascularized tissue to local injury. The causes of inflammation are many and varied. Inflammation may occur in response to trauma, chemical or physical injury, autoimmune responses and infectious agents, but also in response to physiological conditions, such as diet and exercise [1,2]. Inflammation is an important component of innate immunity and necessary for priming adaptive immunity, but is also crucial for the effector phase of the immune response. Soluble mediators, such as chemokines, are shown to play an important role in driving the various components of inflammation, especially leukocyte influx. They may originate from plasma-derived systems, such as complement and kinins, from recruited or tissue-resident cells or released as a direct consequence of tissue damage [3,4].

The chemokine system in mammals is complex and comprises around 50 ligands, which are constitutively expressed or induced by inflammatory stimuli, and 20 G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) or seven transmembrane receptors [5,6]. In this article, the properties of C–C chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5), also known as regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), one of the members of the mammalian chemokine system will be explored. Chemokines bind to their receptors which are expressed on many cell types, including leukocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, epithelial, smooth muscle and parenchymal cells. The interaction between chemokines and their receptors is said to be promiscuous in the sense that several receptors interact with multiple ligands and several ligands interact with more than one receptor. It has been previously argued that this complexity of the system is important for the many actions of chemokine system but is not absolute. Some chemokine–chemokine receptor interactions are not functionally redundant and can potentially be targeted by drugs that block the receptor or interfere with the function of the ligand [5]. Chemokines play an important role in leukocyte biology, by controlling cell recruitment and activation in basal and in inflammatory circumstances. In addition, because chemokine receptors are expressed on other cell types, chemokines have multiple other roles, including angiogenesis, tissue and vascular remodeling, pathogen elimination, antigen presentation, leukocyte activation and survival, chronic inflammation, tissue repair/healing, fibrosis, embryogenesis and tumorigenesis [5,7].

1.1. CCL5/RANTES

The ccl5 gene was discovered in 1988 [8], and this was followed by the isolation and first characterization of the protein in 1990 [9]. Chemokines are structurally related and grouped according to the relative position of conserved cysteine residues, along with the respective receptors. CCL5/RANTES belong to the C–C chemokine subfamily, whose chemokines present adjacent cysteines, and comprises the majority of the chemokines [6,10]. To facilitate reading, the chemokine will be referred to as CCL5 from now on.

CCL5 has been shown to induce the in vitro migration and recruitment of T cells, dendritic cells, eosinophils, NK cells, mast cells and basophils. Although initially considered to be a T cell-specific cytokine (hence the original name, RANTES) [8], CCL5 is produced by platelets, macrophages, eosinophils, fibroblasts, endothelium, epithelial and endometrial cells. The variety of cells that express and mediate CCL5 effects implicates this chemokine in multiple biological processes, from pathogen control to enhancement of inflammation in several ‘sterile' disorders, such as cancer and atherosclerosis [11]. The current tools available for the study of CCL5 are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Tools to study CCL5.

| Tool (Developing company) | Definition and first description | Diseases studied |

|---|---|---|

| Deficient mice | ||

| CCL5-/- | Disruption of CCL5 expression, Makino et al.[12] | SLE, ischemic stroke, influenza inf., autoimmune nephritis, atherosclerosis, liver fibrosis, neuropathic pain, breast cancer |

| CCR1-/- | Disruption of CCR1 expression, Gao et al.[13] | Paramixovirus inf., RSV inf., leishmaniosis, MS, renal fibrosis, wound repair, cutaneous Arthus reaction, sepsis, hepatocellular carcinoma, neurological disease, RA, GVHD, myocardial infarction, Coronavirus inf. , renal ischemia-reperfusion injury, graft arterial disease |

| CCR3-/- | Disruption of CCR3 expression, Humbles et al.[14] | Allergic airway disease, asthma, lung remodeling and fibrosis, lung injury, allergic conjunctivitis, neuronal injury |

| CCR5-/- | Disruption of CCR5 expression, Zhou et al.[15] | HIV, EAE, colitis, transplant rejection and GVHD, cerebral malaria, hepatitis and hepatic fibrosis, C. Trachomatis inf., LCMV inf., RA, liver failure, Chagas disease, tuberculosis, arteriosclerosis, Y. pestis inf., autoimmune neuritis and gastritis, renal fibrosis, L. monocytogenes inf., CNS and neuronal injury, toxoplasmosis, alzheimer disease, ischemia-reperfusion injury, influenza inf., herpetic keratitis, COPD, genital herpes, pancreatitis, HSV inf., autoimmune uveoretinitis, cancer, japanese encephalitis, pain, nephritis, hypertension, allergic airway disease, encephalomyocarditis virus inf., S. mansoni inf., stroke. |

| Modified chemokines | ||

| Recombinant CCL5/RANTES (different suppliers) | Human, mouse and rat CCL5, expressed in bacteria | Viral infections, angiogenesis, cancer, allergic airway inflammation, arteriosclerosis, RA, EAE, and several other disease models. |

| Aminooxypentane (AOP)-RANTES (Merck Serono) (also PSC- and NNY-RANTES) | N-terminal chemically modified CCL5 with antagonistic activity, Simmons et al.[16] | HIV/SIV, RA, glomerulonephritis, tuberculosis, airway inflammation |

| Methionine (Met)-RANTES (Merck Serono) | CCL5 with retention of N-terminal methionine gained antagonistic activity, Proudfoot et al.[17] | HIV, RA, enteritis, transplant rejection, allergic pleurisy, airway inflammation, arteriosclerosis, colitis, RSV and pneumovirus inf., myocardial inflammation, Chagas disease, HSV inf., autoimmune gastritis and uveitis, EAE, wound healing, pancreatitis, angiogenesis, cancer, fever, bronchiolitis obliterans, neuropathic pain, periodontitis, |

| [44AANA47]-RANTES | CCL5 mutated at GAG binding site, impairs CCL5 oligomerization and function in vivo, Johnson et al.[18] | Peritonitis, airway inflammation, EAE, arteriosclerosis, RA, angiogenesis |

| [E66A]-RANTES | CCL5 mutated in oligomerization site, impairs CCL5 function in vivo, Baltus et al.[19] | Angiogenesis/arteriosclerosis |

| MKEY | Peptide inhibitor of CCL5/CXCL4 hetero dimerization, Iida et al.[20] | Aortic aneurism |

| Small-molecule inhibitors | ||

| TAK 220/779 (Takeda Chemical Industries) | CCR5 antagonists, Imamura et al.[21] and Baba et al.[22] | HIV |

| Maraviroc (Pfizer, Inc) | CCR5 antagonist, Fätkenheuer et al.[23] | HIV, RA , GVHD |

| SCH-C (Schering Plough) | CCR5 antagonist, Strizki et al.[24] | HIV |

| Vicriviroc (Schering Plough) | CCR5 antagonist, Strizki et al.[25] | HIV |

| YM-344031 (Astellas) | CCR3 antagonist, Suzuki et al.[26] | Skin allergy, Choroidal neovascularization |

| UCB 35625 (Banyu Pharmaceutical) | CCR1/CCR3 antagonist, Sabroe et al.[27] | HIV |

| CCX721/ CCX354 (Chemo Centryx) | CCR1 antagonists, Dairaghi et al.[28,29] | Myeloma bone disease, RA |

| BX471 (Berlex Biosciences) | CCR1 antagonist, Horuk et al.[30] | RA, MS, Lung injury, Kidney injury, heart transplant |

| MLN3897 (Millennium) | CCR1 antagonist, Vallet et al.[31] | RA, osteolytic bone disease |

| AZD4818 | CCR1 antagonist, Kerstjens et al.[32] | COPD |

| CP-481715 | CCR1 antagonist, Gladue et al.[33] | RA |

| Neutralizing antibodies | ||

| Anti-CCL5 (different companies) | Rat, mouse and human monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies | Viral infections, angiogenesis, cancer, allergic airway inflammation, atherosclerosis, RA, EAE, and several other disease models. |

| MAb d5d7 (VLST corporation) | Targets human CCL3, CCL4 and CCL5, Scalley-Kim et al.[34] | Skin inflammation |

| Nanobodies | Single domain camelid antibody fragment against CCL5, Blanchetot et al.[35] | Chemokine binding, chemokine receptor activation and chemotaxis |

| CCL5-binding proteins | ||

| Evasin 4 | CCL5/CCL11-binding protein, Déruaz et al.[36] | Colitis |

| M3 – Murine γ herpesvirus chemokine binding protein | Soluble, promiscuous binding protein, Parry et al.[37] | Murine γ herpesvirus-68 inf. |

| vCCI, 35K – viral CC chemokine inhibitor | Poxvirus-encoded soluble receptors, Smith et al.[38] | Allergic airway disease, RA, vaccinia virus inf., atherosclerosis, vein graft stenosis, peritonitis, hepatitis |

| M-T7 – mixoma virus T7 protein | IFN-γ/chemokine-binding protein, Lalani et al.[39] | Vascular injury, transplant rejection and angiogenesis |

| Miscelaneous | ||

| Immunization | Naked DNA vaccination inducing anti-CCL5 antibodies in rodents, Youssef et al.[40] | RA, EAE, T. cruzi infection |

Abbreviations: Inf: infection; SLE: Systemic lupus erythematosus; RA: Rheumatoid arthritis; RSV: Respiratory syncytial virus; MS: Multiple sclerosis; GVHD: Graft versus host disease; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; LCMV: lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HSV: Herpes simplex virus; EAE: Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; SIV: Simian immunodeficiency vírus.

Description of the tools (animals, antibodies, modified chemokines, small molecules and chemokine-binding proteins) used for the study of CCL5 and its receptors in different experimental settings.

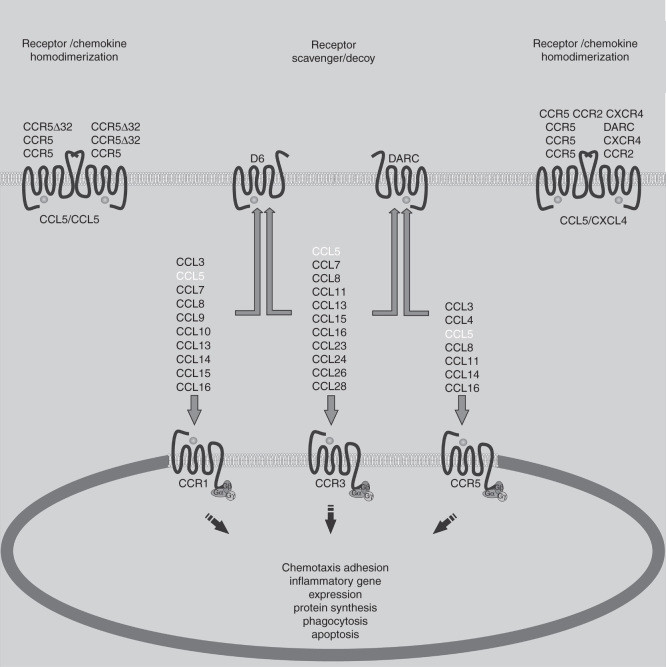

The many biologic effects of chemokines are mediated by their interaction with chemokine receptors on the cell surface. The most relevant known receptors for CCL5 are CCR1, CCR3 and CCR5 [6]. Figure 1 depicts the interactions of CCL5 with its receptors and also the other known chemokine ligands that bind to CCR1, CCR3 and CCR5. The affinity of CCL5 binding to its receptors is variable, with greater affinity for CCR5 and CCR1, and binding CCR3 with less affinity [41]. For the process of cell recruitment in vivo, CCL5 oligomers are immobilized on endothelial glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and interact with the receptors expressed by incoming leukocytes in the blood vessels. Oligomerization is not essential for CCL5 activity in vitro, but has been demonstrated to be crucial for in vivo activity, as well as GAG binding [42]. CCL5 heterodimerization with CXCL4 enhances CCL5 biological functions [43]. For example, CXCL4 may amplify CCL5-dependent monocyte arrest on the endothelium [44]. In their turn, chemokine receptors are fully functional as monomers but also form homo or heterodimers, which allow for new properties such as receptor cointernalization, cross-desensitization and differential signaling [45] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CCL5 biology. The chemokine receptors for CCL5 and common shared agonists for these receptors are illustrated. Chemokine receptor activation has major effects on leukocyte and nonleukocyte populations. Such biological effects may be modulated by the action of nonfunctional (CCR5Δ32) or decoy receptors (D6 and DARC), by chemokine receptor homo- and heterodimerization, or by a combination of both.

CCL5 oligomers interact with the receptors at the three extracellular loops and the aminoterminal portion [10]. The formation of the ligand–receptor complex causes a conformational change in the receptor that activates the subunits Gαi and Gβγ of the G-protein, leading to an increase in levels of cyclic AMP, inositol triphosphate and intracellular calcium [7]. These signaling events cause cell polarization and translocation of NF-κB, which results in the increase of phagocytic ability, cell survival and transcription of proinflammatory genes, many of which are chemokines and chemokine receptors [10,46]. CCL5 is also able to induce G protein-independent signaling. Once G protein-dependent signaling occurs, the CCL5-receptor complex is internalized via chlatrin-mediated endocytosis associated to the adapter molecules Adaptin-2 and β-arrestin. Cytoplasmic organelles and vacuoles are recruited to perform the recycling of receptors, and/or degradation of active chemokine–receptor complexes. These effects are important to regulate receptor levels at the external membrane, allowing for regulation of the cellular activity and reduction of extracellular levels of CCL5 and other chemokines, important to maintain homeostasis [47,48].

The chemokine system also features a group of atypical receptors, which binds CCL5 and does not trigger usual signaling events after interaction, due to uncoupling of the signaling machinery. Unlike other chemokine receptors, the main role of these decoy receptors appears to be the sequestering of ligands, therefore functioning as chemokine scavengers. The best known examples of decoy-receptors that bind CCL5 are DARC [49] and D6 (Figure 1) [49,50].

In the following topics, experimental studies that have investigated the role of CCL5 in various diseases will be described.

2. CCL5 in viral infections

The recognition of pathogenic viruses by the immune system, mostly through engagement of pattern recognition receptors, leads to early production of cytokines. Those include interferons (IFNs), essential for the antiviral response, and proinflammatory mediators, most notably CC chemokines. CCL5 is an early expressed chemokine that can also be induced by TNF-α and IFN-γ at later stages of infection [51]. Among all chemokines, CCL5 and CCL3 are particularly associated with viral infections [52]. CCL5 is released by degranulation from activated virus-specific CD8+ T cells in parallel with granzyme A and perforin [53]. CCL5 is also produced by CD4+ T lymphocytes, epithelial cells, fibroblasts and platelets [54]. Several cell types activated by CCL5 are directly involved in antiviral response, including NK cells, T CD4+ lymphocytes, monocytes, mast cells and dendritic cells [55].

Separately, and certainly a hallmark on the studies of chemokines in viral infections, is the discovery that CCL5 and other chemokines were natural inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. A few months after this discovery, in 1995, it was found that CCR5 was a coreceptor for HIV [56]. Interestingly, human subjects carrying a CCR5 gene variant with a 32 bp deletion in the coding region, named the CCR5Δ32 allele, are resistant to HIV infection and progression of disease. The deletion renders CCR5 defective, and results in impaired viral entry in macrophages, one of the target cells for HIV [57]. Thus, pharmacological blockade of CCR5 was employed as a strategy to treat and prevent HIV infections, resulting in a research boost on the chemokine system and in the development of several inhibitors and antagonists for CCR5 and its ligands [58]. The roles of CCL5 in the context of HIV infection include boosting of T cell responses [55], and direct inhibition [59] or enhancement of infection [54]. Effects of CCL5 in HIV infection vary due to the concentration of CCL5 in situ, as low concentrations activate GPCR-dependent pathways and high concentrations triggers CCL5 aggregation and subsequent G-protein-independent signaling events. GPCR activation by CCL5 inhibits HIV/CCR5 interaction and suppresses HIV infection. Conversely, G protein-independent pathways do not involve CCL5 and HIV competing for the receptor, causes excessive activation of signaling effectors that culminates in cell activation and enhancement of HIV infection [54]. The variety of host tissues affected by viruses, added to different contexts of chronic or acute infection, makes it difficult to define a role for CCL5 in viral infections. Instead, the effects of CCL5 are categorized according to the site of infection/disease and viral tropism.

2.1. Respiratory tract infections

The production of CCL5 has been observed in most viral infections of the respiratory tract. These include infections by hantavirus, reovirus, adenovirus, coxsackie virus, rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and the well-known coronavirus and influenza virus. A unifying feature of pathogenic respiratory tract viruses is that many possess an RNA genome. Some studies have pointed that double-stranded RNA, an intermediate form in viral genome replication, activates TLR3 [60] and contributes to eosinophilic inflammation in the airways, mediated by CCL5 and CCL11, which may aggravate chronic diseases such as asthma. For example, it has been shown that hantaviruses, which may cause life-threatening hemorrhagic or cardiopulmonary syndromes, induce CCL5 in vitro in several cell types and in infected patients [61]. Early CCL5 expression is commonly triggered by nonpathogenic hantaviruses, such as Prospect Hill virus, while pathogenic viruses evade immune detection and delay CCL5 production, which is the case for Hantaan virus. CCL5 is believed to play a role in the initial control of viral replication, which would prevent prolonged proinflammatory responses that likely contribute to disease pathogenesis [61].

RSV is a common etiologic agent of lower respiratory tract infection in infants, inducing obstructive lung diseases and bronchial asthma [62]. Children with RSV infections have increased CCL5 levels in airway secretions and CCL5 expression at the upper airway correlates positively with disease severity. Using a murine model of RSV infection, Culley et al. found that CCL5 expression occurs in two phases: the first as a consequence of the innate response by resident lung cells, and the second derived from CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Treatment with Met-RANTES, a functional inhibitor of CCL5, at the second phase of CCL5 production reduced immunopathology, suggesting that CCL5 receptors play a central role in driving inflammation in RSV lung disease. However, chemokine blockade during the first phase showed opposite effects, which makes it difficult to anticipate what would be the effects of targeting this pathway in clinical studies [63].

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is an acute life-threatening respiratory illness that differs in severity from other coronavirus infections. Elevated serum levels of chemokines in SARS patients suggest that SARS pathogenesis may be due to immune dysregulation. Law et al. found that the nsp1 protein of SARS coronavirus was a strong inducer of CCL5 in human lung epithelial cells, in contrast to nsp1 proteins from nonpathogenic coronaviruses. In another study of acute respiratory infection, combined treatment with antivirals and CCR1 blockade resulted in increased survival in pneumovirus-infected mice [64]. These findings corroborate the idea that (SARS) pathogenesis, and similar respiratory syndromes, have a strong immune/inflammatory component that can be targeted through CCL5 intervention [52,65].

Finally, CCL5 was shown to be involved in influenza virus infections. In vitro infection of human alveolar macrophages with the H1N1 PR/8 strain showed a 234-fold increase in CCL5 mRNA expression [66]. Also, studies demonstrated that CCL5 is elevated in the lungs of H5N1-infected patients [67]. Interestingly, a comparative analysis of a seasonal Influenza strain and the H1N1 pandemic strain revealed that the pandemic strain induced greater levels of CCL3 and CCL5 in human macrophages. This was related to the ability of the pandemic strain to suppress SOCS-1 and RIG-I expression, which resulted in elevated chemokine levels that could contribute to the cytokine storm presented by severe flu patients [68]. To evaluate the role of CCL5 in influenza and paramyxovirus infections, Tyner et al. infected CCL5- and CCR5-deficient mice and demonstrated that the CCL5-CCR5 axis provided antiapoptotic signals to virus-infected macrophages. Usually, apoptosis of infected cells would be helpful for the host, but the enhanced apoptosis of infected macrophages deprived of CCL5-CCR5 signaling reduced the clearance of viruses and infected cell debris, which contributed to tissue damage. Thus, activation of CCR5 by CCL5 is important to extend macrophage survival and control infection [69].

2.2. Neurotropic infections

Neuroinflammation, or inflammation in the central nervous system (CNS), must be carefully regulated to avoid immune-mediated neuronal death. CCL5 is induced in several models of viral CNS infection [70,71], and participates in the activation of microglia and in the recruitment of T lymphocytes and NK cells, that could either result in pathogenesis or viral clearance [72]. Astrocytes are able to secrete CCL5 when exposed to the dsRNA analogue poly I:C, but not when exposed to other PRR ligands [73]. CCL5 production by astrocytes was shown to contribute to pathogenesis in the infection by Borna disease virus, which does not cause neuronal death directly. In fact, neuronal degeneration was mediated by microglia, when activated by astrocyte-derived CCL5 [74]. In a murine model of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, it is known that IFN-γ-producing T CD4+ cells mediate pathogenesis in the CNS. Further investigation by Lin et al. demonstrated that IFN-γ induced the production of CCL5 (and other proinflammatory chemokines) by microglia/macrophages, which enhances neuroinflammation and culminates in mice weight loss [75]. Rabies virus (RV) induces CCL5 production by microglia during replication, through p38-NFκB activation [76]. This induction is controlled by the protein N of RV pathogenic strains, which prevents RIG-I activation and further CCL5 production, leading to disease and lethality in infected mice [77]. In contrast, Zhao et al. infected mice with a genetically modified RV strain that overexpresses CCL5, for the purpose of vaccination, and found that this strain caused extensive neuroinflammation, culminating in neurological disease and mice death, thus confirming the major role that CCL5 play in leukocyte recruitment to the CNS [78].

Besides a deleterious proinflammatory role that CCL5 could play in CNS, this chemokine is protective against RV and against other viruses. A well-studied example involves acute infection by West Nile virus (WNV) in mice, in which the lack of CCR5 leads to decreased leukocyte recruitment, increased viral load in the CNS and enhanced mortality. WNV infection induces high and continuous levels of CCL5, which is required for the local accumulation of NK cells, macrophages and T lymphocytes to control infection [79]. In agreement with these findings, epidemiological studies found that humans possessing the CCR532 allele are more prone to symptomatic infection by WNV, due to a defective CCR5/CCL5-axis. Similar observations were made for Tick-borne encephalitis virus, which indicates that CCL5-mediated cell recruitment could be a common mechanism of resistance to neurotropic flaviviruses [80,81].

Among herpes viruses, herpes simplex viruses (HSV-1, -2) are neurotropic viruses that cause encephalitis in newborns and immunocompromised humans. CCL5 was shown to be produced during herpetic encephalitis in mice and mediate T cell recruitment to the CNS [82]. Other reports demonstrate that CCL5 is upregulated in latently infected trigeminal ganglia, a major feature of HSV-1 infection, which results in the retention of T lymphocytes in neurons of both mice and humans and prevents viral reactivation [83].

Large DNA viruses, such as herpes viruses, present a high level of adaptation to the human host and are known to cause latent infections. Under immune suppressive conditions, herpes viruses may reactivate and cause neurological disease. Latency is possible due to the ability of the virus to evade immune surveillance, commonly blocking the effect of CCL5 and other proinflammatory chemokines [84]. Human herpes virus (HHV)-8 blocking strategies for chemokines are many and includes a viral chemokine that antagonizes CCR3 and CCR5 [85], the viral chemokine-binding protein M3 that binds to all chemokines at nanomolar affinities, and a HHV-8-encoded GPCR that induces cell proliferation [86]. The human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is particularly dedicated to control CCL5 biologic functions, as it encodes a micro-RNA that downregulates CCL5 expression [87] and a chemokine-binding protein that binds to CCL5 at picomolar rates and prevent interactions with host chemokine receptors [88]. This indicates that CCL5 is an important mediator for the control of HCMV infections.

2.3. Liver infections

Infectious liver diseases are a major threat to human health. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection causes chronic hepatic inflammation with risk of developing cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Polymorphisms in ccl5 gene showed that CCL5 is protective in hepatitis C, since a mutation in the -403 position that increases CCL5 expression resulted in reduced portal inflammation and milder fibrosis. Conversely, patients that carry the CCR532 allele also have reduced inflammation and fibrosis, which indicates that the CCL5-CCR5 pathway could play a role in disease pathogenesis [89]. Another study with hepatitis B virus (HBV) found similar results, where the combination of the -403 CCL5 and CCR532 polymorphisms was associated with recovery from HBV infection [90].

The yellow fever virus (YFV) is the causative agent of a hemorrhagic fever with characteristic clinical presentations due to severe liver injury, hence the name ‘yellow fever' [91]. YFV infections have been successfully controlled through vaccination with an attenuated live strain, though a small percentage of vaccinees develop yellow fever. A study by Pulendran et al. described a unique YFV vaccine-associated viscerotropic disease patient, which presented persistent viremia; robust activation of T and B lymphocytes; and a 200-fold increase in the number of CD14+CD16+ circulating monocytes. Those observations were associated to the genetic background of the patient, who was heterozygous for the -403 CCL5 and CCR532 gene variants, leading to the aberrant immune response to YFV vaccination [92]. Dengue virus (DENV) is closely related to YFV and causes a similar hemorrhagic fever, which emerged as a major world health problem in the past decades. Recent findings on dengue confirmed that DENV infection damages the liver, due to the elevation of serum transaminase levels in severe disease patients [93]. Histological analysis of liver sections from dengue fatal cases show lymphocytes, Kupfer cells and sinusoidal endothelium positively stained for CCL5, which correlates with increased hepatic CCL5 levels observed in acute dengue patients [94]. This increase in hepatic CCL5 due to DENV infection could mediate leukocyte recruitment to the organ and contribute to the systemic inflammation that culminates in the hemorrhagic phenomena. CCL5 production was also described in a dengue model in mice, where CCL5 levels were concomitant with liver injury. However, it is not known if CCL5 contributes to injury or is produced as a consequence of tissue damage in dengue [95].

In conclusion, in the context of respiratory and neurotropic viral infections, it seems that CCL5 production presents a dual role. CCL5 is necessary to control certain viral infection, including influenza, RSV, RV, HSV and WNV. The antiviral role of CCL5 is evident in HHV-8 and HCMV infections, where immune evasion mechanisms targeting CCL5 are essential and actively employed by these viruses. However, CCL5 seems to be deleterious in later phases of infection, where it contributes to excessive inflammation and tissue damage in all the diseases addressed in this section. Thus, conceptually, it would be ideal to block CCL5 in later phases of infection, where immunopathology is the main component of respiratory or neurotropic diseases, rather than the virus itself. The role of CCL5 in liver infections is not as clear, especially because beneficial or detrimental effects of CCL5 are dependent on the chemokine receptor engaged and whether the infection is chronic (viral hepatitis) or acute (YFV and DENV). However, CCL5-mediated inflammation is a common feature of these infections in later phases, which contributes to fibrosis or to hemorrhagic manifestations depending on the infection. Therefore, any potential blockade of CCL5 or its receptors in the context of viral infections could only be employed at the later stages of disease in order to prevent immunopathology. Earlier treatment could have deleterious effects on the capacity of the host to deal with the viral infection. As separating early (viral-mediated) and late (immune-mediated) phases of disease after viral infection may be very problematic in the clinical context, it is not likely that strategies aimed at blocking CCL5 or its receptors may be useful in patients. The clear exception is HIV as in this case blockade of CCR5 is associated with decreased viral entry. Blocking CCL5 in the context of HIV is unlikely to achieve similar benefits.

3. Helminth infection

Infections by S. mansoni may evolve to chronic illness with fibrotic liver injury, characterized by the formation of granulomas around parasite eggs. In a study by Souza et al., liver granulomas of chronically infected CCR5–/– mice showed more cells and greater collagen deposition in comparison with WT mice, which was associated with higher levels of IL-5, IL-13, CCL3 and CCL5. Therefore, CCR5 abrogation was deleterious during experimental S. mansoni infection, due to enhanced fibrosis and granulomatous inflammation [96]. Among different consequences of S. mansoni infection, periportal fibrosis of the liver is a serious event that involves remodeling of the extracellular matrix and excessive deposition of collagen, primarily by hepatic stellate cells. Booth et al. demonstrated that a high TNF-α concentration in adult men was the single risk factor for S. mansoni-induced node size, but low TNF-α levels were not protective if the patient also expressed low CCL5 levels [97]. A comprehensive analysis of chemokine expression in a mouse model of S. mansoni infection showed that CCL5 levels were higher where the Th1 response was enhanced, for example by administration of IL-12 in combination with egg antigen [98]. This study was in accordance with other reports stating that CCL5 was protective in S. mansoni infection, and suggested that high levels of CCL5 resulted in reduced granulomas. In addition, Chensue et al.'s study on pulmonary granulomas elicited with antigens of S. mansoni showed that CCL5 played different roles on granuloma formation. Specifically, CCL5 contributed to a Th1-biased inflammation and limited the Th2 response, analogous to the effect of IFN-γ in the polarization of immune responses. These findings suggest that CCL5 is an important regulatory molecule that plays distinct roles in Th1- and Th2-driven inflammatory responses in schistosomiasis [99].

However, in different contexts, after genetic ablation of CCR5, CCL5 has been shown to efficiently bind to CCR1 and promote NK cell recruitment and activation in a T cell mediated hepatitis model [100]. Thus, the increased binding of CCL5 to CCR1 upon blockade or deletion of CCR5 would be an additional aspect to explain the discrepancy between CCL5 and CCR5 neutralizing strategies in different disease contexts. This aspect should therefore be taken into account when designing therapeutic strategies and assigning specific roles to CCL5.

Overall, it appears that infected mice or patients with schistosomiasis, which present a mild form of disease, develop an adaptive immune response with greater activation of CCR5 over CCR1. Conversely, severe forms of disease associate with increased activation of CCR1 over CCR5. CCR1 activation would be predominantly mediated by CCL3, while CCR5 activation would be predominantly mediated by CCL5 [96]. Despite sharing nearly identical receptor affinities, the specificity of CCL3 and CCL5 are well defined, and result in opposing activities regarding the clinical presentation of disease. CCL5 is evidently protective in schistosomiasis. The Th2-biased immune response developed against helminthes is pathogenic, contributing to the generation and maintenance of granulomas. Thus, any potential pharmacological drug development should prioritize CCL5 activity through CCR5 in order to prevent immunopathology. As CCL5 administration to patients is likely to cause unwanted effects, blockade of CCR1 in addition to antischistosomal drugs could be of potential value in patients with the most severe diseases.

4. Asthma

Allergic inflammatory diseases usually develop in tissues that present large epithelial surface areas, such as the lung, skin and gut. To understand how tissue-specific memory and inflammation-specific T cell trafficking facilitates the development of allergic disease would be of great therapeutic interest [101]. In animal models of acute allergic inflammation, cytokines and chemokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-13, CCL5 and CCL11 have been shown to induce eosinophilic airway inflammation, antigen-specific IgE production, and airway hyperresponsiveness [102]. CCL5 has been identified in the airways of asthmatic patients, where it induces eosinophil recruitment through the CCR3 receptor [103]. Airway inflammation and cytokines/chemokines production are important markers of asthma, but the asthmatic response is complex and difficult to transpose to experimental models [104].

CCL5 mediates eosinophil, neutrophil and monocyte recruitment to the airways [9,105] and initiates important events in the inflammatory response such as integrin activation, lipid mediator biosynthesis and degranulation [106]. CCL5 is constitutively expressed in the lungs and in the bronchoalveolar fluid of patients with asthma [107]. Several in vivo studies have described the CCL5-dependent recruitment of eosinophils during allergic airway inflammation, where treatment with met-RANTES decreased eosinophilia after antigen challenge [108]. Regarding the contribution of CCL5 to the development of airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), Koya et al. reported that after repeated allergen challenge in sensitized mice, CCL5 is upregulated and disease is reduced [104]. Similar to schistosomiasis, in AHR, CCL5 has been shown to modulate cytokine production, inducing a shift from Th2- to Th1-response [99]. This mechanism was exploited by Kline et al., where administration of CpG with the allergen reduced AHR and airway eosinophilia, due to an increase in CCL5 expression that suppressed eotaxin production [109].

The deleterious influence of RSV infection on airway allergy was confirmed by John and colleagues [110] and linked to the production of CCL5, which exacerbates AHR during RSV infection per se. The adoptive transfer of CD8+ T cells from RSV-infected mice into allergen-sensitized mice induced AHR in the sensitized mice, which suggests that CD8+ T lymphocytes could be the source of CCL5 in this context [111]. These observations are supported by previous reports on the release of CCL5 by cytotoxic T lymphocytes during viral infection [53], bringing mitigating evidence that RSV infection, through the release of chemokines (i.e., CCL5), may play a significant role in enhancing lung inflammation after allergic challenge.

Asthma is a complex condition, and there is much evidence suggesting that CCL5 is expressed in patients with disease and it correlates with disease severity [112]. Moreover, preclinical studies suggest that CCL5 and its receptors may contribute to disease pathogenesis [104]. Certain viruses, such as RSV, may worsen experimental allergic airway inflammation and blockade of CCL5 may also prevent exacerbation under these conditions. Therefore, targeting CCL5 in the context of human asthma could be of potential therapeutic interest. Nevertheless, there are some reports suggesting that CCL5 may drive immunoregulatory mechanisms which decrease airway hyperreactivity [110].

5. Atherosclerosis

The role of CCL5 in atherosclerosis has been extensively addressed in several studies in the past 15 years [113]. The expression of CCL5 is detected in atherosclerotic plaques and in monocyte/macrophages, and is regulated by the Rel proteins p50 and p65. Moreover, the Kruppel-like factor 13 (KLF13), originally designated RANTES factor of late activated T lymphocytes-1, has been recently identified as a new transcription factor that regulates the expression of CCL5 in CD4+ T cells [114]. In smooth muscle cells (SMCs), the expression of CCL5 is controlled by the transcriptional regulator Y-box binding protein-1 (YB-1) [115]. It has been shown that the overexpression of YB-1 in arterial SMCs greatly increased CCL5 transcriptional activity, eventually leading to CCL5-mediated monocyte recruitment. CCR1 and CCR5 are expressed on cell types that participate in atherosclerosis (i.e., monocytes/macrophages, T lymphocytes), and mediate CCL5-dependent arrest and transendothelial diapedesis, resulting in full transmigration into the inflamed tissue. These receptors have also been implicated in the detrimental effects caused by emigrated cells at atherosclerotic lesion sites [116].

The blockade of CCL5 receptors has distinct roles on atherosclerosis. Genetic ablation of ccr5 reduced the extent of atherosclerotic lesions induced by diet, and the late response, leading to a more stable plaque, reduced mononuclear infiltration and inducing a Th1-biased immune response. In contrast, the lack of CCR1 enhanced atherosclerotic plaque development and exacerbated local accumulation of T cells [117]. In a model of arterial wire injury in ApoE–/– mice, CCR5 deficiency protected against neointima formation, which was attributed to an upregulation of IL-10 in neointimal SMCs. In this model, CCR1 deficiency did not affect neointimal area or cell accumulation, but led to an increase in IFN-γ [113,118]. Separately, knock-down of YB-1, which reduces CCL5 expression in carotid arteries, led to a significant reduction in neointima formation and macrophage accumulation after injury. The protection induced by YB-1 knockdown was not observed in Apoe–/–, CCR5–/– or after treatment with Met-RANTES, indicating that the effects of CCL5 are dependent from CCR5 and CCR1 activation [115]. CCL5 is not only expressed within the atherosclerotic plaque, but platelets also represent an important source of CCL5 under pathological and nonpathological vascular conditions [119]. In mice, platelets have been shown to exacerbate atherogenesis through deposition of CCL5/CXCL4 heterodimers, triggering monocyte arrest on inflamed endothelium. Treatment with specific inhibitors of CCL5/CXCL4 interaction attenuates monocyte recruitment and reduces atherosclerosis without compromising other aspects of the immune response [120]. In accordance, curative treatment with [44AANA47]-RANTES, which disrupts CCL5 interactions with GAGs, limited atherosclerotic plaque formation and increased plaque stability in LDLr–/– mice, indicating the protective effect of CCL5 blockade in atherosclerosis [121].

Akin to asthma, there is good evidence that CCL5 is expressed and may play a role in human atherosclerosis. Experimental studies have mostly focused on the CCL5 receptors and their role in driving disease is not straight forward and may be opposite. Studies targeting CCL5 with modified proteins (e.g., [44AANA47]-RANTES) do suggest that CCL5 plays a deleterious role in experimental atherosclerosis. Whether this will translate into clinical benefits in humans is not known at present.

6. Angiogenesis and cancer

CCL5 is associated with chronic inflammation and may play a direct role in angiogenesis and in other angiogenesis-dependent processes, such as the progression of some tumors. The latter effects could be due to CCL5-mediated leukocyte and nonleukocyte recruitment and activation. Angiogenesis is characterized by the sprouting of new vessels from preexisting activated endothelial cells, which migrates and proliferates to form new vessels. These events will help to form anastomic connections between newly formed vessels, finally splitting into arterioles and capillaries [122]. In homeostasis, angiogenesis participates in embryogenesis and organ development, as well as in tissue remodeling under pathological conditions [122].

Chemokines have been shown to contribute to angiogenesis by balancing the stimulation or inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation and branching. The main chemokines studied in angiogenesis are the CXC chemokines, but CC chemokines have also been described to contribute to this process. The involvement of CCL5 in the context of inflammatory angiogenesis has been previously shown. For example, in a model of sponge-induced inflammatory angiogenesis CCL5 had antiangiogenic activity [123]. CCL5 expression was detected early after sponge implantation, but levels significantly increased thereafter. Exogenous administration of CCL5 reduced angiogenesis in WT mice via CCR5, as CCL5 had no effect in CCR5−/− mice. In accordance with these observations, treatment of WT mice with Met-RANTES prevented neutrophil and macrophage accumulation and enhanced sponge vascularization [123].

In contrast, several studies suggest that CCL5 may be considered as a proangiogenic factor. CCL5 oligomerization and binding to GAGs are essential to induce angiogenic effects through CCR1 and CCR5 [124]. Indeed, CCR5−/− mice had reduced corneal neovascularization, which correlated with reduced expression of VEGF, suggesting that CCR5 is a key player in the process of corneal neovascularization [125]. Thus, CCL5 could be associated to VEGF in the context of angiogenesis, and this is supported by in vitro studies showing the promotion of endothelial cell migration, spreading and neo-vessel formation by CCL5 [124]. Moreover, Met-RANTES reduced endothelial progenitor cell homing to activated (glomerular) endothelium in vitro and in vivo [126] in a rat model of glomerulonephritis.

Tumors are known to recruit blood vessels to continue growth and to promote potential routes for metastasis [122]. CCL5 is expressed in a variety of cancer and metastatic processes, such as breast carcinoma [127], melanoma [128] and papillary thyroid carcinoma [129]. For instance, chemokines expressed by malignant and stromal cells contribute to the extent and phenotype of the tumor-associated leukocytes, to angiogenesis and to the generation of the fibroblast stroma. In fact, CCL5 recruits monocyte and macrophage precursors to the tumor microenvironment and positively correlates with the extent of myeloid cell infiltrate and tumor progression [130]. Tumors that expressed low levels of CCL5 exhibited a decrease in growth rate in vivo, which is associated to a greater tumor-specific T cell response. Conversely, tumors expressing high levels of CCL5 induce a reduced T cell response and upregulates matrix metalloproteinase-9 transcripts, which contributes to angiogenesis. These observations indicate that tumor-derived CCL5 facilitate tumor growth by inhibiting T cell responses and enhancing angiogenesis [131]. Chemokines may also provide survival signals for malignant cells, since these cells gain functional chemokine receptors that may contribute to metastatic activity. Malignant cells acquire leukocyte-like properties and are able to respond to chemokine gradients at sites of metastasis [132]. CCL5 is secreted by senescent aged fibroblasts, induces proliferation of prostate epithelial cells and induces expression of genes related to angiogenesis [133]. The interaction between cancer and its local microenvironment can determine properties of growth and metastasis. Osteopontin promotes CCL5-mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-mediated breast cancer metastasis, by increasing MSC migration to metastatic sites in lung and liver, promoting tumor progression via the transformation of MSC into cancer-associated fibroblasts [134]. Collectively, these data suggested that CCL5 plays a central role in cancer progression, by affecting tumor directly and by controlling leukocyte recruitment and angiogenesis. Thus, therapies that block CCL5 or its receptors could potentially help the treatment of cancer and metastasis, given that its blockade reduces tumor angiogenesis and not the opposite.

7. Fibrosis and transplant rejection

Fibrosis is commonly a result of chronic inflammation. Fibrosis is defined by the excessive collagen accumulation in and around inflamed or damaged tissue, which can lead to permanent scarring and organ malfunction, and ultimately death. It is related to major pathological features of different chronic autoimmune diseases [135]. In fact, some fibrogenic diseases are associated to CCL5 expression or CCR5 activation. In patients with localized scleroderma, a significant increase in mRNA for CCL5 was found in the lesions [136]. CCL5 was localized in the cytoplasm in CD68+ alveolar macrophages in sarcoidosis, and in both alveolar macrophages and eosinophils in fibrosing alveolitis [137]. Also, CCL5 expression was associated with increasing numbers of CD45RO+ lymphocytes in the bronchoalveolar lavage, indicating that CCL5 may mediate T-lymphocyte influx. Collectively, CCL5 is important for fibrosis in diffuse lung disease and the cell sources of CCL5 are alveolar macrophages, macrophages and eosinophils [137]. Separately, in a mouse model of lung fibrosis induced by bleomycin, the CCL3-CCR5 axis, but not CCL5-CCR5 axis, was associated to the presence of intrapulmonary fibrocytes and collagen accumulation, which is also linked to high numbers of TGFβ+ macrophages and myofibroblasts [138].

The antagonist Met-RANTES was used to evaluate the role of CCL5 in hepatic fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride. Met-RANTES blocked the effects of hematopoietic cells-derived CCL5 on cultured stellate cell, inhibiting migration, proliferation, chemokine secretion and collagen deposition. Importantly, in vivo administration of Met-RANTES ameliorated liver fibrosis in mice and was able to accelerate fibrosis regression, suggesting that CCL5-receptors blockade reduce inflammation and may be used to treat liver fibrosis [139]. Met-RANTES also diminished early infiltration and activation of mononuclear cells in kidney fibrosis and chronic allograft nephropathy, with an important reduction in the expression of TGFβ and PDGF-B [140]. The sole blockade of CCR1, instead of CCR1/CCR5 blockade caused by Met-RANTES treatment, can also be employed to prevent chronic inflammation and tissue remodeling. CCR1−/− mice are more resistant to myocardial infarction, presenting reduced recruitment of proinflammatory cells early after the infarction, associated with increased tissue healing [141].

CCL5 has also been implicated in organ transplant rejection, in which CCL5 would mediate the recruitment of mononuclear cells that destroy the transplanted tissue and contributes to transplant dysfunction or loss. Treatment with BX471, a small-molecule antagonist of CCR1, prolonged allograft rejection in a heart transplant model in rats. This improvement in heart transplant survival was attributed to reduced endothelial damage, as CCR1 blockade reduced CCL5-mediated monocyte arrest on the transplanted heart endothelium [30]. In another study, BX 471 reduced the progression of chronic renal allograft damage, also through reduction of mononuclear cell recruitment to the renal tissue. Decreased numbers of mononuclear cells led to reductions in collagen deposition, TGFβ1 levels and α-SMA+ interstitial myofibroblasts accumulation in the renal allograft [142].

These data suggest that blockade of CCL5 receptors may represent a therapeutic opportunity in fibrosis and transplant rejection, since CCR5/CCR1 blockade effectively reduces leukocyte recruitment and prevents tissue damage and remodeling. Whether blockade of CCL5 would achieve similar results needs to be determined.

8. Expert opinion

There are many epidemiological and clinical studies in several human diseases demonstrating the expression of CCL5 and correlation with indices of disease activity. These data are compounded by many preclinical studies showing the functional role of CCL5 and its receptors. Overall, there is good evidence that CCL5 has unique roles in driving recruitment of leukocytes, angiogenesis and fibrosis in various models of chronic inflammation. Therefore, blockade of CCL5 and its receptors may be useful in decreasing inflammatory cell influx and fibrosis in chronic diseases. Possible targets for CCL5-based drugs include chronic lung diseases, such as asthma and pulmonary fibrosis, liver fibrosis and atherosclerosis. There is also good evidence that CCL5 may play a role in driving angiogenesis and tumor growth, suggesting CCL5-based therapies may be useful as adjunct therapy of certain solid tumors. Moreover, there are good data suggesting that CCL5 plays relevant role in the immune response against certain infections, especially viral infections. This is against the notion that the chemokine system is redundant or promiscuous. There are clearly distinct roles played by chemokines and their receptors which could eventually be translated into novel therapies.

Genetic functional deficiency of CCR5 and blockade of CCR5 with antagonists are clearly beneficial in the context of HIV infection. The role of CCL5 and its receptors in the context of other viral diseases is much less clear. Whereas CCL5 may have host-protective effects in the early phases of viral infections, it may also contribute to disease pathogenesis by driving influx of cells which may damage tissues. This dual effect of CCL5 makes it difficult to target this chemokine in human diseases, as it is difficult to make clear distinction between phases where there is only viral replication or immunopathology. It may be argued that targeting CCL5 could be added to available antiviral drugs. This is indeed a possibility for drug development but faces the issue of timely recognition of the etiology of viral infections in the clinical setting. We are particularly interested in the role played by CCL5 in diseases caused by flaviviruses, the viruses that compose the Flavivirus genre. Infection with these pathogens can cause an intense inflammatory response, which may manifest as encephalitis or as a hemorrhagic fever, depending on viral tropism. CCL5 is a component of this intense inflammatory response and is likely to contribute to disease in later phases of infection. St. Louis encephalitis and dengue are examples of flaviviral infections in which the precise role of CCL5 still needs to be determined.

Table 2 lists clinical trials which target CCL5 and its receptors in human diseases [143]. As can be seen, the majority of ongoing clinical trials involves antagonism of CCL5 receptors and not targeting of CCL5 itself. Therefore, the exact function of this chemokine in the context of human disease still remains to be determined. This is not a minor point as CCL5 may bind to multiple receptors and the targeted receptors may be activated by multiple chemokines (Figure 1). Clearly, nonredundant functions of any chemokine or receptor will be only uncovered when a particular molecule is targeted in humans. Antagonists, such as [44ANAA47]-RANTES, [E66A]-RANTES and MKEY (Table 1), prevent binding of CCL5 to GAGs or its oligomerization. As these molecules compete directly with CCL5 for its functions and have a mechanism of action distinct from receptor antagonism, they may provide further insight into the biology of CCL5 in human diseases. However, to the best of our knowledge, these modified molecules have not been taken into humans yet. Only recently, an antibody which targets CCL5 (NovImmune SA, NI-0701, Table 2) has passed Phase I clinical studies and have become available for further human experimentation. It will be instrumental in determining the exact role of CCL5 in human diseases.

Table 2.

Clinical trials targeting CCL5/RANTES and receptors in human disease.

| Compound name | Strategy | Company/Sponsor | Disease of interest | Official title of clinical studies | Phase and status | Trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cenicriviroc | CCR2 and CCR5 Antagonist | Tobira Therapeutics, Inc. | HIV/AIDS | A Phase IIb randomized, double-blind, double-dummy trial of 100 or 200 mg once-daily doses of cenicriviroc (CVC, TBR 652) or once-daily EFV, each with Open-Label FTC/TDF, in HIV 1-Infected, antiretroviral treatment-Naïve, adult patients with only CCR5-Tropic virus | Phase II: ongoing | NCT01338883 |

| GW873140 | CCR5 Antagonist | GlaxoSmithKline | HIV/AIDS | A Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, parallel group study to compare the efficacy and safety of GW873140 400 mg BID in combination with a ritonavir-containing optimized background therapy regimen versus placebo plus OBT over 48 weeks. | Phase III: terminated | NCT00297076 |

| INCB009471 | CCR5 Antagonist | Incyte Corp. | HIV/AIDS | A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study exploring the safety, tolerability, PK & virological effect of once daily Oral dosing of INCB009471 as monotherapy for 14 days in ARV-naïve/Limited ARV-experienced, HIV-1 infected patients | Phase II: completed | NCT00393120 |

| TBR 652 | CCR5 Antagonist | Tobira Therapeutics, Inc. | HIV/AIDS | A proof of concept, multiple dose-escalating study to evaluate the antiviral activity, safety, and pharmacokinetics of the CCR5 antagonist TBR 652 in HIV 1-infected, antiretroviral treatment-experienced, CCR5 antagonist-naïve patients | Phase I and II: completed | NCT01092104 |

| Maraviroc | CCR5 Antagonist | ViiV Healthcare/Pfizer | HIV/AIDS | Drug use investigation for HIV infection patients of maraviroc (regulatory post marketing commitment plan) | Phase IV: Ongoing | NCT00864474 |

| Maraviroc | CCR5 Antagonist | University of California, San Francisco/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)/Pfizer | HIV/AIDS | Effect of maraviroc on endothelial function in HIV-infected patients | Phase III: Ongoing | NCT00844519 |

| Maraviroc | CCR5 Antagonist | Fundacion para la Investigacion Biomedica del Hospital Universitario Ramon y Cajal/Pfizer | HIV/AIDS | Pilot study of the effect of a CCR5 coreceptor antagonist on the latency and reservoir of HIV-1 in patients taking highly active antiretroviral therapy | Phase II: ongoing | NCT00795444 |

| Maraviroc | CCR5 Antagonist | ViiV Healthcare/Pfizer | HIV/AIDS | A multicenter, randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the safety of maraviroc in combination with other antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected subjects co-infected with Hepatitis C and/or Hepatitis B virus | Phase IV: ongoing | NCT01327547 |

| Maraviroc | CCR5 Antagonist | University of California, San Francisco/Pfizer/ViiV Healthcare | HIV/AIDS Kaposi Sarcoma | effects of maraviroc on HIV-related kaposi's sarcoma | Phase III: study recruiting | NCT01276236 |

| Maraviroc | CCR5 Antagonist | University of Pennsylvania/Pfizer | GVHD\⊂ Transplantation | Safety and efficacy of maraviroc, a CCR5-inhibitor in prophylaxis of graft-Versus-host disease in patients undergoing non-myeloablative allogeneic stem-cell transplantation | Phase I and II: completed | NCT00948753 |

| Maraviroc | CCR5 Antagonist | National Center for Tumor Diseases, Heidelberg/University Hospital Heidelberg/Pfizer | Colorectal cancer/Liver metastasis | Treatment of advanced colorectal cancer patients with hepatic liver metastases using the CCR5-antagonist maraviroc (phase I maracon trial) | Phase I: recruiting | NCT01736813 |

| Maraviroc | CCR5 Antagonist | Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania/Pfizer | GVHD/Cancer | A phase II study to assess the efficacy of maraviroc, a CCR5-antagonist in prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease in patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing reduced-intensity allogeneic stem-cell transplantation from unrelated donors | Phase II: recruiting | NCT01785810 |

| Maraviroc | CCR5 Antagonist | S.F.L. van Lelyveld, UMC Utrecht/Pfizer | HIV/Cardiovascular disease | Maraviroc abacavir study - effect on endothelial recovery | Phase IV: recruiting | NCT01389063 |

| GSK706769 | CCR5 Antagonist | GlaxoSmithKline | Rheumatoid arthritis | A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group study to investigate the ability of GSK706769 to maintain clinical remission after withdrawal of enbrel in patients with rheumatoid arthritis | Phase II: | NCT00979771 |

| Vicriviroc, SCH 417690 | CCR5 Antagonist | Schering-Plough | HIV/AIDS | Vicriviroc in combination treatment with an optimized ART regimen in treatment-experienced subjects with R5/X4 HIV infection (VICTOR-E2; protocol no. P05057) | Phase II: completed | NCT00551330 |

| NI-0701 | Antibody against CCL5 | NovImmune SA | Chemokine blockade | A first in man randomized placebo controlled study of single ascending intravenous doses of NI-0701 in healthy volunteers | Phase I: completed | NCT01255501 |

| PRO 140 | Antibody against CCR5 | Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | HIV/AIDS | A Phase IIa, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study of PRO 140 by subcutaneous administration in adult subjects with Human Immunodeficiency virus Type 1 Infection | Phase II: Completed | NCT00642707 |

| CCR5mAb004 | Antibody against CCR5 | Human Genome Sciences, Inc./GlaxoSmithKline | HIV/AIDS | A Phase I, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-injection, dose-escalation study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of Ccr5mab004 (human monoclonal Igg4 antibody to Ccr5) in HIV-1 seropositive individuals who are not receiving concurrent antiretroviral therapy | Phase I: Completed | NCT00114699 |

| HGS1025 | Antibody against CCR5 | Human Genome Sciences, Inc./GlaxoSmithKline | Ulcerative Colitis | A Phase Ib, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study to Evaluate the Pharmacodynamics and Safety of HGS1025, a Human Monoclonal Anti-CCR5 Antibody, in Subjects With Ulcerative Colitis | Phase I: | NCT01434576 |

| CCX 354-C | CCR1 Antagonist | ChemoCentryx | Rheumatoid arthritis | A Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase I/II study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of CCX354-C in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis | Phase I and II: completed | NCT01027728 |

| BAY86-5047, ZK811752, SH T 04268H | CCR1 Antagonist | Bayer | Endometriosis | A Multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study to evaluate the safety, tolerability and efficacy of the CCR1 antagonist ZK 811752, given orally in a dose of 600 mg three times daily, for the treatment of endometriosis over 12 weeks | Phase II: Completed | NCT00185341 |

| AZD4818 | CCR1 Antagonist | AstraZeneca | COPD | A 4-week double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, parallel group phase IIa study to assess the tolerability/safety and efficacy of inhaled AZD4818 in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Phase II: Completed | NCT00629239 |

| CP-481,715 | CCR1 Antagonist | Pfizer | Skin allergy | Placebo-controlled, randomized, parallel group, multiple-dose study to evaluate the effects of CP-481,715 on clinical response and cellular infiltration following contact allergen challenge to the skin of nickel allergic subjects. | Phase I: Completed | NCT00141180 |

| GW766944 | CCR3 Antagonist | GlaxoSmithKline | Asthma/Sputum eosinophilia | A Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group study to compare GW766944 (an oral CCR3 receptor antagonist) versus placebo in patients with asthma and sputum eosinophilia | Phase II: Completed | NCT01160224 |

| SB-728 | Zinc Finger Nuclease modified T cells | University of Pennsylvania/Sangamo Biosciences | HIV/AIDS | A Phase I study of autologous T-cells genetically modified at the CCR5 gene by zinc finger nucleases SB-728 in HIV-infected patients | Phase I: completed | NCT00842634 |

| Lentivirus vector rHIV7-shI-TAR-CCR5RZ | Lentivirus vector rHIV7-shI-TAR-CCR5RZ-transduced hematopoietic progenitor cells | City of Hope Medical Center/National Cancer Institute (NCI) | HIV/Cancer | A pilot study of safety and feasibility of stem cell therapy for aids lymphoma using stem cells rreated with a lentivirus vector-encoding multiple anti-HIV RNAs | Phase I: ongoing | NCT00569985 |

| CCR5delta32 hematopoietic stem cell | HLA-compatible hematopoietic stem cell from CCR5delta32homozygotes donors | Medical College of Wisconsin/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)/National Cancer Institute (NCI)/Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network | HIV/Cancer | Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant for hematological cancers and myelodysplastic syndromes in HIV-infected individuals | Phase II: recruiting | NCT01410344 |

Description of the clinical trials targeting CCL5/RANTES and its receptors in human disease [139].

AIDS: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GVHD: Graft versus host disease; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus.

Article highlights.

CCL5 is a key proinflammatory chemokine.

CCL5 can contribute to protection in certain infectious diseases.

Strong experimental evidence suggests that CCL5 blockade can prevent immunopathology.

Current experimental tools and clinical trials have focused on chemokine receptor antagonism.

New tools to block CCL5 directly must be developed in order to precisely assess CCL5 biologic functions.

This box summarizes key points contained in the article.

Declaration of interest

RE Marques received a sponsorship from the Brazilian funding agency CNPq. MM Teixeira and RC Russo receive funding from various Brazilian support agencies (CNPq, FAPEMIG, FINEP) and grants from the European community. R Guabiraba receives sponsorship from the Wellcome Trust, UK. The authors state no conflict of interest.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 2008;454:428-35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• A modern and consistent approach on inflammation and its underlying mechanisms.

- 2.Alessandri AL, Sousa LP, Lucas CD, et al.. Resolution of inflammation: mechanisms and opportunity for drug development. Pharmacol Ther 2013;139(2):189-212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll MC. The role of complement and complement receptors in induction and regulation of immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 1998;16:545-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nathan C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature 2002;420:846-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russo RC, Garcia CC, Teixeira MM. Anti-inflammatory drug development: broad or specific chemokine receptor antagonists? Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel 2010;13:414-27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy PM. International union of pharmacology. XXX. Update on chemokine receptor nomenclature. Pharmacol Rev 2002;54:227-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • The latest update on the chemokine system nomenclature.

- 7.Murphy PM. The molecular biology of leukocyte chemoattractant receptors. Annu Rev Immunol 1994;12:593-633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schall TJ, Jongstra J, Dyer BJ, et al.. A human T cell-specific molecule is a member of a new gene family. J Immunol 1988;141:1018-25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This article describes the discovery of the ccl5 gene.

- 9.Schall TJ, Bacon K, Toy KJ, et al.. Selective attraction of monocytes and T lymphocytes of the memory phenotype by cytokine RANTES. Nature 1990;347:669-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Following the previous reference, the same group first describes the chemotactic properties of CCL5.

- 10.Allen SJ, Crown SE, Handel TM. Chemokine: receptor structure, interactions, and antagonism. Annu Rev Immunol 2007;25:787-820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy JA. The unexpected pleiotropic activities of RANTES. J Immunol 2009;182:3945-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makino Y, Cook DN, Smithies O, et al.. Impaired T cell function in RANTES-deficient mice. Clin Immunol 2002;102:302-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao JL, Wynn TA, Chang Y, et al.. Impaired host defense, hematopoiesis, granulomatous inflammation and type 1-type 2 cytokine balance in mice lacking CC chemokine receptor 1. J Exp Med 1959;185:1959-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humbles AA, Lu B, Friend DS, et al.. The murine CCR3 receptor regulates both the role of eosinophils and mast cells in allergen-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:1479-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Y, Kurihara T, Ryseck RP, et al.. Impaired macrophage function and enhanced T cell-dependent immune response in mice lacking CCR5, the mouse homologue of the major HIV-1 coreceptor. J Immunol 1998;160:4018-25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simmons G, Clapham PR, Picard L, et al.. Potent inhibition of HIV-1 infectivity in macrophages and lymphocytes by a novel CCR5 antagonist. Science 1997;276:276-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proudfoot AE, Power CA, Hoogewerf AJ, et al.. Extension of recombinant human RANTES by the retention of the initiating methionine produces a potent antagonist. J Biol Chem 1996;271:2599-603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw JP, Johnson Z, Borlat F, et al.. The X-ray structure of RANTES: heparin-derived disaccharides allows the rational design of chemokine inhibitors. Structure 2004;12:2081-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baltus T, Weber KS, Johnson Z, et al.. Oligomerization of RANTES is required for CCR1-mediated arrest but not CCR5-mediated transmigration of leukocytes on inflamed endothelium. Blood 2003;102:1985-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iida Y, Xu B, Xuan H, et al.. Peptide inhibitor of CXCL4-CCL5 heterodimer formation, MKEY, inhibits experimental aortic aneurysm initiation and progression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013;33:718-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imamura S, Ichikawa T, Nishikawa Y, et al.. Discovery of a piperidine-4-carboxamide CCR5 antagonist (TAK-220) with highly potent Anti-HIV-1 activity. J Med Chem 2006;49:2784-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baba A, Oda T, Taketomi S, et al.. Studies on disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. III. Bone resorption inhibitory effects of ethyl 4-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-6,7-dimethoxy-2-(1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethyl) quinoline-3-carboxylate (TAK-603) and related compounds. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1999;47:369-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fatkenheuer G, Pozniak AL, Johnson MA, et al.. Efficacy of short-term monotherapy with maraviroc, a new CCR5 antagonist, in patients infected with HIV-1. Nat Med 2005;11:1170-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strizki JM, Xu S, Wagner NE, et al.. SCH-C (SCH 351125), an orally bioavailable, small molecule antagonist of the chemokine receptor CCR5, is a potent inhibitor of HIV-1 infection in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:12718-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strizki JM, Tremblay C, Xu S, et al.. Discovery and characterization of vicriviroc (SCH 417690), a CCR5 antagonist with potent activity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005;49:4911-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki K, Morokata T, Morihira K, et al.. In vitro and in vivo characterization of a novel CCR3 antagonist, YM-344031. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006;339:1217-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabroe I, Peck M.J, Van Keulen B.J., et al.. A small molecule antagonist of chemokine receptors CCR1 and CCR3. Potent inhibition of eosinophil function and CCR3-mediated HIV-1 entry. J Biol Chem 2000;275:25985-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dairaghi D.J, Zhang P, Wang Y, et al.. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of the novel CCR1 antagonist CCX354 in healthy human subjects: implications for selection of clinical dose. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;89:726-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dairaghi DJ, Oyajobi BO, Gupta A, et al.. CCR1 blockade reduces tumor burden and osteolysis in vivo in a mouse model of myeloma bone disease. Blood 2012;120:1449-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horuk R, Clayberger C, Krensky AM, et al.. A non-peptide functional antagonist of the CCR1 chemokine receptor is effective in rat heart transplant rejection. J Biol Chem 2001;276:4199-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vallet S, Raje N, Ishitsuka K, et al.. MLN3897, a novel CCR1 inhibitor, impairs osteoclastogenesis and inhibits the interaction of multiple myeloma cells and osteoclasts. Blood 2007;110:3744-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerstjens HA, Bjermer L, Eriksson L, et al.. Tolerability and efficacy of inhaled AZD4818, a CCR1 antagonist, in moderate to severe COPD patients. Respir Med 2010;104:1297-303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gladue RP, Tylaska LA, Brissette WH, et al.. CP-481,715, a potent and selective CCR1 antagonist with potential therapeutic implications for inflammatory diseases. J Biol Chem 2003;278:40473-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scalley-Kim ML, Hess BW, Kelly RL, et al.. A novel highly potent therapeutic antibody neutralizes multiple human chemokines and mimics viral immune modulation. PLoS One 2012;7:e43332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blanchetot C, Verzijl D, Mujic-Delic A, et al.. Neutralizing Nanobodies targeting diverse chemokines effectively inhibit chemokine function. J Biol Chem 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deruaz M, Frauenschuh A, Alessandri AL, et al.. Ticks produce highly selective chemokine binding proteins with antiinflammatory activity. J Exp Med 2008 205: p. 2019;31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parry CM, Simas JP, Smith VP, et al.. A broad spectrum secreted chemokine binding protein encoded by a herpesvirus. J Exp Med 2000;191:573-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith CA, Smith TD, Smolak PJ, et al.. Poxvirus genomes encode a secreted, soluble protein that preferentially inhibits beta chemokine activity yet lacks sequence homology to known chemokine receptors. Virology 1997;236:316-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lalani AS, Graham K, Mossman K, et al.. The purified myxoma virus gamma interferon receptor homolog M-T7 interacts with the heparin-binding domains of chemokines. J Virol 1997;71:4356-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Youssef S, Maor G, Wildbaum G, et al.. C-C chemokine-encoding DNA vaccines enhance breakdown of tolerance to their gene products and treat ongoing adjuvant arthritis. J Clin Invest 2000;106:361-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blanpain C, Buser R, Power CA, et al.. A chimeric MIP-1alpha/RANTES protein demonstrates the use of different regions of the RANTES protein to bind and activate its receptors. J Leukoc Biol 2001;69:977-85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Proudfoot AE, Handel TM, Johnson Z, et al.. Glycosaminoglycan binding and oligomerization are essential for the in vivo activity of certain chemokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:1885-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This article demonstrates that chemokine oligomerization and interaction with GAGs are crucial for CCL5 function in vivo.

- 43.Nesmelova IV, Sham Y, Gao J, et al.. CXC and CC chemokines form mixed heterodimers: association free energies from molecular dynamics simulations and experimental correlations. J Biol Chem 2008;283:24155-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Hundelshausen P, Koenen RR, Sack M, et al.. Heterophilic interactions of platelet factor 4 and RANTES promote monocyte arrest on endothelium. Blood 2005;105:924-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thelen M, Muñoz LM, Rodríguez-Frade JM, Mellado M. Chemokine receptor oligomerization: functional considerations. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2010;10(1):38-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thelen M, Stein JV. How chemokines invite leukocytes to dance. Nat Immunol 2008;9:953-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cardona AE, Sasse ME, Liu L, et al.. Scavenging roles of chemokine receptors: chemokine receptor deficiency is associated with increased levels of ligand in circulation and tissues. Blood 2008;112:256-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mantovani A, Locati M. Housekeeping by chemokine scavenging. Blood 2008;112:215-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mantovani A, Locati M, Vecchi A, et al.. Decoy receptors: a strategy to regulate inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Trends Immunol 2001;22:328-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jamieson T, Cook DN, Nibbs RJ, et al.. The chemokine receptor D6 limits the inflammatory response in vivo. Nat Immunol 2005;6:403-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grandvaux N, Servant MJ, tenOever B, et al.. Transcriptional profiling of interferon regulatory factor 3 target genes: direct involvement in the regulation of interferon-stimulated genes. J Virol 2002;76:5532-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glass WG, Rosenberg HF, Murphy PM. Chemokine regulation of inflammation during acute viral infection. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;3:467-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A comprehensive review adressing the solid asssociation between CC chemokines and viral infections.

- 53.Catalfamo M, Karpova T, McNally J, et al.. Human CD8+ T cells store RANTES in a unique secretory compartment and release it rapidly after TcR stimulation. Immunity 2004;20:219-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Appay V, Rowland-Jones SL. RANTES: a versatile and controversial chemokine. Trends Immunol 2001;22:83-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tedla N, Palladinetti P, Kelly M, et al.. Chemokines and T lymphocyte recruitment to lymph nodes in HIV infection. Am J Pathol 1996;148:1367-73 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder CC, et al.. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science 1996;272:1955-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This article describes the discovery of CCR5 as a co-receptor for HIV. This discovery is a hallmark in the fields of chemokine and viral research.

- 57.Liu R, Paxton WA, Choe S, et al.. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell 1996;86:367-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• The discovery that CCR5 deficiency was protective in HIV infection encouraged the development of most chemokine inhibitors and antagonists existing today.

- 58.Fatkenheuer G, Pozniak AL, Johnson MA, et al.. Efficacy of short-term monotherapy with maraviroc, a new CCR5 antagonist, in patients infected with HIV-1. Nat Med 2005;11:1170-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • The first demonstration that a small-molecule antagonist of CCR5, which concluded clinical testing, could be employed to treat HIV infections in patients.

- 59.Kinter AL, Ostrowski M, Goletti D, et al.. HIV replication in CD4+ T cells of HIV-infected individuals is regulated by a balance between the viral suppressive effects of endogenous beta-chemokines and the viral inductive effects of other endogenous cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:14076-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niimi K, Asano K, Shiraishi Y, et al.. TLR3-mediated synthesis and release of eotaxin-1/CCL11 from human bronchial smooth muscle cells stimulated with double-stranded RNA. J Immunol 2007;178:489-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Handke W, Oelschlegel R, Franke R, et al.. Hantaan virus triggers TLR3-dependent innate immune responses. J Immunol 2009;182:2849-58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoon JS, Kim HH, Lee Y, et al.. Cytokine induction by respiratory syncytial virus and adenovirus in bronchial epithelial cells. Pediatr Pulmonol 2007;42:277-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Culley FJ, Pennycook AM, Tregoning JS, et al.. Role of CCL5 (RANTES) in viral lung disease. J Virol 2006;80:8151-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bonville CA, Lau VK, DeLeon JM, et al.. Functional antagonism of chemokine receptor CCR1 reduces mortality in acute pneumovirus infection in vivo. J Virol 2004;78:7984-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Law AH, Lee DC, Cheung BK, et al.. Role for nonstructural protein 1 of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in chemokine dysregulation. J Virol 2007;81:416-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang J, Nikrad MP, Travanty EA, et al.. Innate immune response of human alveolar macrophages during influenza A infection. PLoS One 2012;7:e29879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Korteweg C, Gu J. Pathology, molecular biology, and pathogenesis of avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in humans. Am J Pathol 2008;172:1155-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]