Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to evaluate the risk of acute respiratory failure in all hospitalised patients based on admission serum ionised calcium.

Design

A retrospective cohort study.

Setting

A tertiary referral hospital in Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

Participants

All hospitalised patients who had serum ionised calcium measurement within 24 hours of hospital admission from January 2009 to December 2013. Patients who were mechanically ventilated at admission were excluded.

Predictors

Admission serum ionised calcium levels was stratified into six groups: ≤4.39, 4.40–4.59, 4.60–4.79, 4.80–4.99, 5.00–5.19 and ≥5.20 mg/dL.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was the development of acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation during hospitalisation. Logistic regression analysis was fit to assess the independent risk of acute respiratory failure based on various admission serum ionised calcium, using serum ionised calcium of 5.00–5.19 mg/dL as the reference group.

Results

Of 25 709 eligible patients, with the mean serum ionised calcium of 4.8±0.4 mg/dL, acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation occurred in 2563 patients (10%). The incidence of acute respiratory failure was lowest when admission serum ionised calcium was 5.00–5.19 mg/dL, with the progressively increased risk of acute respiratory failure with decreased serum ionised calcium. In multivariate analysis with adjustment for potential confounders, the increased risk of acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation was significantly associated with admission serum ionised calcium of ≤4.39 (OR 2.52; 95% CI 2.12 to 3.00), 4.40–4.59 (OR 1.76; 95% CI 1.49 to 2.07) and 4.60–4.79 mg/dL (OR 1.48; 95% CI 1.27 to 1.72), compared with serum ionised calcium of 5.00–5.19 mg/dL. The risk of acute respiratory failure was not significantly increased when serum ionised calcium was at least 4.80 mg/dL.

Conclusion

The increased risk of acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation was observed when admission serum ionised calcium was lower than 4.80 mg/dL in hospitalised patients.

Keywords: ionised calcium, respiratory failure, mechanical ventilation, hospitalisation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is a large cohort study that investigates the association between serum ionised calcium and the risk of respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation in all hospitalised patients

This study extensively adjusted for several potential confounders to assess the independent association

Due to retrospective observational study design, the causal relationship between admission serum ionised calcium cannot be firmly established.

Introduction

Calcium has many essential functions including intracellular signalling, muscle function, nerve transmission and mediating vascular contraction and vasodilatation.1 Serum calcium consists of three portions.1 Approximately 15% is bound to organic and inorganic anions, 40% is bound to proteins, particularly albumin, and 45% circulates as active ionised calcium.2 This last portion is strictly controlled by parathyroid hormone and vitamin D.3 Total serum calcium concentration substantially varies on the serum concentration of albumin and hydration status without any alteration in the concentration of ionised calcium.4–7 Hence, measuring only total serum calcium might be misleading. The gold standard for assessing calcium status is to measure ionised calcium.8–10

Recently, we demonstrated that both decreased and elevated serum calcium levels were related to higher short-term and long-term mortality in hospitalised patients.11 12 However, the cause of death was not investigated in the previous study. Acute respiratory failure (ARF) is a common and life-threatening condition among hospitalised patients13–15 and is associated with high morbidity and mortality worldwide.16–22 Previously, we identified several electrolyte derangements at the time of hospital admission as risk factors for ARF in hospitalised patients. These risk factors included hypophosphataemia or hyperphosphataemia,20 low serum creatinine,21 hypoalbuminaemia,23 hypokalaemia or hyperkalaemia24 and hypomagnesaemia or hypermagnesaemia.25 Alterations of serum calcium have been linked to the development of ARF in several case reports.26–30 While hypocalcaemia can lead to ARF due to muscle weakness, tetany, laryngeal and bronchospasm, patients with severe hypercalcaemia can present with lethargy, confusion and coma, resulting in ARF.26–30 However, previously described cases focused on the total serum calcium concentration, and the risk of in-hospital ARF among patients with various serum ionised calcium levels is not elucidated in a large clinical study.

Our study aimed to assess the association between serum ionised calcium level, measured at the admission, and the risk of ARF requiring mechanical ventilation during hospitalisation as we hypothesised that serum ionised calcium is an early predictor of ARF requiring mechanical ventilation.

Materials and methods

Study population

This is a single-centre cohort study. We used our previous cohort of all adult hospitalised patients with available admission serum ionised calcium from years 2009 to 2013 in the analysis. Because we aimed to assess the risk of ARF as the primary outcome measure, we further excluded mechanically ventilated patients at the time of admission. The need for informed consent was exempted due to the minimal risk nature of the study, but all included patients provided authorisation of their data use for research purpose.

Data collection and outcomes

Automated retrieval from the institutional electronic medical record system was used to obtain clinical characteristics and laboratory data of patients in this study. The primary predictor was the admission serum ionised calcium, defined as the initial serum ionised calcium value measured within 24 hours of hospital admission. Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation was used to estimate glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).31 Comorbidity burden of an individual patient was assessed using Charlson Comorbidity Index.32 Acute kidney injury was defined based on Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria. The primary outcome measure was in-hospital ARF requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, as previously described in our published studies.20 21 23–25 The use of invasive mechanical ventilation was abstracted from our intensive care unit (ICU) DataMart, which documented all mechanical ventilation use in the ICU, including the start and end time of mechanical ventilation. The use of mechanical ventilation during the procedure and non-invasive ventilation support were not considered as the outcome. ARF was considered hypercapnic if partial pressure of carbon dioxide from arterial blood gas before mechanical ventilation was at least 50 mm Hg.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination of this study.

Statistical analysis

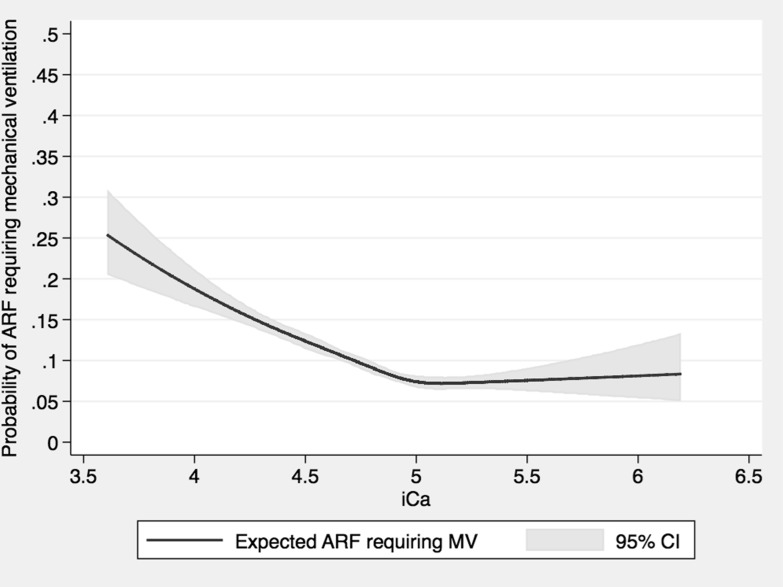

The difference in continuous and categorical variables among admission serum ionised calcium group was tested, using analysis of variance and the χ2 test, respectively. The restricted cubic spline with five knots was constructed to depict the potential non-linear association between admission serum ionised calcium and the risk of ARF requiring mechanical ventilation. Admission serum ionised calcium was categorised into six groups based on the percentile distribution (10% | 25% | 50% | 75% | 90%): ≤4.39, 4.40–4.59, 4.60–4.79, 4.80–4.99, 5.00–5.19 and ≥5.20 mg/dL. The admission serum ionised calcium level of 5.00–5.19 mg/dL was the reference group, because it was considered within normal reference range of 4.57–5.43 mg/dL, based on our institutional laboratory test, and it had the lowest incidence of ARF requiring mechanical ventilation. Multivariable logistic regression was conducted to evaluate admission serum ionised calcium level that was independently associated with the risk of ARF requiring mechanical ventilation. The OR was adjusted for a prespecified variables reported in table 1. Two sensitivity analyses was performed to: (1) assess the association between admission serum ionised calcium and the risk of hypercapnic ARF requiring mechanical ventilation and (2) assess the association between albumin-corrected total serum calcium and the risk of ARF requiring mechanical ventilation. Missing data were not imputed. All analyses were two tailed. Statistical significance was achieved when p value less than 0.05. JMP statistical software (V.10) was used for all analyses.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics

| Variables | All | Serum ionised calcium level at hospital admission (mg/dL) | ||||||

| ≤4.39 | 4.40–4.59 | 4.60–4.79 | 4.80–4.99 | 5.00–5.19 | ≥5.20 | P | ||

| N | 25 709 | 2336 | 3539 | 7108 | 7137 | 3589 | 2000 | |

| Age (year) | 63±17 | 60±17 | 63±17 | 64±17 | 64±17 | 63±18 | 65±17 | <0.001 |

| Male | 13 829 (54) | 1207 (52) | 1977 (56) | 3974 (56) | 3888 (54) | 1853 (52) | 930 (47) | <0.001 |

| Caucasian | 23 712 (92) | 2096 (90) | 3269 (92) | 6598 (93) | 6596 (92) | 3311 (92) | 1842 (92) | <0.001 |

| GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 73±32 | 62±39 | 73±33 | 76±29 | 76±29 | 75±31 | 63±33 | <0.001 |

| Charlson score | 2.3±2.6 | 2.4±2.7 | 2.4±2.7 | 2.2±2.6 | 2.1±2.5 | 2.1±2.5 | 2.6±2.8 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 5516 (21) | 410 (18) | 678 (19) | 1498 (21) | 1614 (23) | 839 (23) | 477 (24) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 14 439 (56) | 1266 (54) | 1906 (54) | 3906 (55) | 4039 (57) | 2069 (58) | 1253 (63) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5884 (23) | 545 (23) | 787 (22) | 1492 (21) | 1649 (23) | 894 (25) | 517 (26) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2051 (8) | 170 (7) | 319 (9) | 547 (8) | 538 (8) | 289 (8) | 188 (9) | 0.01 |

| COPD | 2663 (10) | 209 (9) | 353 (10) | 728 (10) | 764 (11) | 396 (11) | 213 (11) | 0.13 |

| Asthma | 2047 (8) | 174 (7) | 275 (8) | 558 (8) | 592 (8) | 312 (9) | 136 (7) | 0.13 |

| Dementia | 491 (2) | 20 (0.8) | 43 (1) | 131 (2) | 154 (2) | 84 (2) | 59 (3) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 2326 (9) | 165 (7) | 264 (7) | 579 (8) | 679 (10) | 403 (11) | 236 (12) | <0.001 |

| Cirrhosis | 759 (3) | 121 (5) | 145 (4) | 208 (3) | 156 (2) | 73 (2) | 56 (3) | <0.001 |

| End-stage renal disease | 1261 (5) | 345 (15) | 227 (6) | 260 (4) | 209 (3) | 116 (3) | 104 (5) | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 8962 (35) | 786 (34) | 1289 (36) | 2531 (36) | 2574 (36) | 1138 (32) | 644 (32) | <0.001 |

| Principal diagnosis | ||||||||

| Cardiovascular | 5554 (22) | 295 (13) | 566 (16) | 1549 (22) | 1832 (26) | 908 (25) | 404 (20) | <0.001 |

| Haematology/oncology | 5526 (21) | 415 (18) | 932 (26) | 1804 (25) | 1402 (20) | 599 (17) | 374 (19) | |

| Infectious disease | 1044 (4) | 236 (10) | 204 (6) | 248 (3) | 180 (3) | 97 (3) | 79 (4) | |

| Endocrine/metabolic | 1078 (4) | 136 (6) | 149 (4) | 252 (4) | 253 (4) | 128 (4) | 160 (8) | |

| Respiratory | 1104 (4) | 94 (4) | 144 (4) | 294 (4) | 346 (5) | 140 (4) | 86 (4) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 2774 (11) | 336 (14) | 436 (12) | 739 (10) | 720 (10) | 381 (11) | 162 (8) | |

| Genitourinary | 1104 (4) | 223 (10) | 165 (5) | 228 (3) | 210 (3) | 117 (3) | 161 (8) | |

| Injury and poisoning | 3419 (13) | 330 (14) | 490 (14) | 957 (13) | 937 (13) | 487 (14) | 218 (11) | |

| Other | 4106 (16) | 271 (12) | 453 (13) | 1037 (15) | 1257 (18) | 732 (20) | 356 (18) | |

| Acute kidney injury at admission | 5671 (22) | 869 (37) | 850 (24) | 1287 (18) | 1255 (18) | 707 (20) | 703 (35) | <0.001 |

| Vasopressor use at admission | 1306 (5) | 183 (8) | 211 (6) | 392 (6) | 345 (5) | 109 (3) | 66 (3) | <0.001 |

Continuous data are presented as mean±SD; categorical data are presented as count (percentage).

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

Results

Clinical characteristics

We screened 288 120 hospital admissions during the study period. We excluded patients with no research authorisation (n=1701), paediatric patients (n=32 139), those with no admission serum ionised calcium measurement (n=184 241), those on mechanical ventilation at hospital admission (n=7546) and readmission (n=36 784) were excluded. A total of 25 709 eligible patients with available admission serum ionised calcium were analysed (online supplementary figure S1). Fifty-four per cent of enrolled patients were male. The mean age was 63±17 years. The mean admission serum ionised calcium was 4.8±0.4 mg/dL. Nine per cent, 14%, 28%, 28%, 14% and 8% had admission serum ionised calcium of ≤4.39, 4.40–4.59, 4.60–4.79, 4.80–4.99, 5.00–5.19 and ≥5.20 mg/dL. Table 1 showed the clinical characteristics of patients based on admission serum ionised calcium levels.

bmjopen-2019-034325supp001.pdf (317.6KB, pdf)

Admission serum ionised calcium and the risk of in-hospital ARF

Of 25 709 patients, 2563 (10.0%) had in-hospital ARF requiring mechanical ventilation. Patients with admission serum ionised calcium of 5.00–5.19 mg/dL had the lowest incidence of in-hospital ARF, whereas patients with admission serum ionised calcium of ≤4.39 mg/dL had the highest incidence (table 2). Higher incidence of in-hospital ARF was noted with decreased admission serum ionised calcium (figure 1) below 5.00 mg/dL. In multivariable analysis with adjustment for potential confounders, the higher risk of in-hospital ARF was significantly associated with admission serum ionised calcium of ≤4.39 (OR 2.52; 95% CI 2.12 to 3.00), 4.40–4.59 (OR 1.76; 95% CI 1.49 to 2.07) and 4.60–4.79 mg/dL (OR 1.48; 95% CI 1.27 to 1.72), compared with admission serum ionised calcium of 5.00–5.19 mg/dL. There was no significant difference in the risk of in-hospital ARF when admission serum ionised calcium was at least 4.8 mg/dL. There was a higher risk of in-hospital ARF with an adjusted OR of 1.85 (95% CI 1.66 to 2.09) when admission serum ionised decreased by 1 mg/dL.

Table 2.

The association between admission serum ionised calcium levels and in-hospital acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation

| Serum ionised calcium level at hospital admission (mg/dL) | Mechanical ventilator in hospital | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| OR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted OR (95 % CI) | P | ||

| ≤4.39 | 388 (16.6) | 2.53 (2.14 to 2.99) | <0.001 | 2.52 (2.12 to 3.00) | <0.001 |

| 4.40–4.59 | 429 (12.1) | 1.75 (1.49 to 2.06) | <0.001 | 1.76 (1.49 to 2.07) | <0.001 |

| 4.60–4.79 | 742 (10.4) | 1.48 (1.28 to 1.71) | <0.001 | 1.48 (1.27 to 1.72) | <0.001 |

| 4.80–4.99 | 590 (8.3) | 1.14 (0.98 to 1.33) | 0.08 | 1.13 (0.97 to 1.32) | 0.11 |

| 5.00–5.19 | 262 (7.3) | 1 (ref) | – | 1 (ref) | – |

| ≥5.20 | 152 (7.6) | 1.04 (0.85 to 1.29) | 0.68 | 1.14 (0.93 to 1.41) | 0.22 |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, estimated glomerular filtration rate, Charlson Comorbidity Score, history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, dementia, stroke, cirrhosis, end-stage renal failure, obesity, principal diagnosis, acute kidney injury and vasopressor use at hospital admission.

Figure 1.

The rate of mechanical ventilation (MV) use in hospital based on admission serum ionised calcium level. ARF, acute respiratory failure.

In a sensitivity analysis, admission serum ionised calcium level of ≤4.79 mg/dL was significantly associated with the higher risk of in-hospital hypercapnic ARF requiring mechanical ventilation (online supplementary table S1). In addition, the analysis in 8534 patients with available admission albumin-corrected total serum calcium showed that admission serum calcium of ≤8.5 mg/dL was significantly associated with the higher risk of in-hospital ARF (OR 1.45; 95% CI 1.28 to 1.63), compared with admission serum calcium of 8.6–10.0 mg/dL (the normal reference range in our hospital). In contrast, admission serum calcium of ≥10.1 mg/dL was not significantly associated with the higher risk of in-hospital ARF (OR 1.08; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.37). There was a higher risk of in-hospital ARF with an adjusted OR of 1.10 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.17) when admission serum ionised calcium decreased by 1 mg/dL.

Discussion

This study demonstrated a statistically significant inverse relationship between admission serum ionised calcium and the subsequent risk of in-hospital ARF requiring mechanical ventilation in hospitalised patients. Lower admission serum ionised calcium was progressively associated with the higher risk of in-hospital ARF when admission serum calcium was below 4.8 mg/dL. There was no difference in the risk of in-hospital ARF when admission serum ionised calcium was at least 4.8 mg/dL.

Our study is the first observational study that assessed the serum ionised calcium level as a predictor of in-hospital ARF requiring mechanical ventilation among hospitalised patients. Calcium is known to inhibit sodium channels and represses depolarisation of nerve and muscle fibres. Hence, hypocalcaemia decreases the threshold for depolarisation to fire an action potential.33 Patients with hypocalcaemia may present with various clinical signs and symptoms that correlate with neuromuscular irritability, such as neurological, cardiovascular, psychiatric and respiratory manifestations.27 34 35 In addition to muscle weakness and tetany causing ARF,26–28 diaphragmatic weakness, laryngeal spasm and bronchospasm leading to ARF have also been reported in patients with severe hypocalcaemia.29 Low serum ionised calcium may also cause cardiac dysfunction including QTc interval prolongation and reduced left ventricular systolic function, resulting in acute pulmonary oedema.36 In addition, lower serum ionised calcium may also reflect the severity of respiratory alkalosis, which eventually leads to diaphragm fatigue and weakness due to hypocalcaemia as well as the heavy workload of the diaphragm from principal disease per se.37 38 The data on the simultaneous assessment of partial pressure of oxygen and fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) was limited by inaccuracies of FiO2 documentation. Therefore, the assessment of the correlation between ionised serum calcium level and hypoxaemic respiratory failure was challenging. Meanwhile, we were able to assess the association between admission serum ionised calcium and the risk of in-hospital hypercapnic ARF. We demonstrated that low admission serum ionised calcium of ≤4.79 mg/dL was significantly associated with the higher risk of in-hospital hypercapnic ARF. In addition, we demonstrated that hypocalcaemia based on total serum calcium level, which is not altered by acid/base status, was also associated with the higher risk of in-hospital ARF. Our findings suggested a role of ionised serum calcium level as an early predictor of in-hospital ARF.

Our study had several strengths. We included a large cohort of 25 709 patients. Hence, we could use multiple logistic regressions to comprehensively adjust for a number of potential confounders without causing any overfitting problems. Moreover, we categorised serum ionised calcium based on percentile to explore the possibility of non-linear association, which might not be seen if we modelled serum ionised calcium as a continuous variable.

There are some limitations in our study. Due to the retrospective nature of our observational study design, causality would not be established. It is possible that lower ionised calcium is a marker of the initial severity of ARF, which predicted the requirement for mechanical ventilation or the lower ionised calcium plays a pivotal role in diaphragm weakness, which leads to ARF. However, regardless of which mechanistic pathway, we were able to highlight the significance of serum ionised calcium as a predictor of in-hospital ARF. Although we extensively adjusted for potential confounders, the association between admission serum ionised calcium and the risk of in-hospital ARF might remain confounded by unmeasured or unknown factors. The data from this study were retrieved from the institutional electronic database. Unfortunately, some important clinical information such as the causes of serum ionised calcium derangements, vitamin D levels, the causes and types of in-hospital ARF, underlying neuromuscular disease and chronic respiratory failure was not available or incomplete in our database, and therefore, we were not able to report them. There is a large and growing literature implicating inadequate vitamin D status as a risk factor for adverse outcomes including bronchospasm, acute respiratory infections and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations.39–41 Thus, future studies are required to assess whether low vitamin D levels modify the effect of decreased admission serum ionised calcium and the increased risk of ARF. Also, serum ionised calcium is often not measured in hospitalised patients when they were initially admitted to the hospital. A selection bias should be considered when we limited the analysis in patients with available admission serum ionised calcium. Included patients who had available admission serum ionised calcium were older, lower eGFR, had more comorbidity conditions, were more primarily admitted for haematology/oncology or gastrointestinal disease than those who did not have available admission serum ionised calcium and were excluded from the analysis (online supplementary table S2). Finally, our study was a single-centre study, and most of the included individuals were from the Caucasian race. This might limit the generalisability of the study.

In summary, there is an association between admission serum ionised calcium lower than 4.80 mg/dL and higher risk of in-hospital ARF requiring mechanical ventilation. Hence, a serum ionised calcium level might potentially be a good predictor of ARF requiring mechanical ventilation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CT, WC and KK originated the idea and designed study. CT, AC, WC and MAM collected data. CT analysed the data. CT and AC were responsible for writing the manuscript. WC, MAM, KK supported the editing of the manuscript and added important comments to the manuscript. KK supervised the study. All authors had access to the data, read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Beto JA. The role of calcium in human aging. Clin Nutr Res 2015;4:1–8. 10.7762/cnr.2015.4.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pekar JD, Grzych G, Durand G, et al. . Calcium state estimation by total calcium: the evidence to end the never-ending story. Clin Chem Lab Med 2019. (published Online First: 2019/09/02). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bushinsky DA, Monk RD. Electrolyte quintet: calcium. Lancet 1998;352:306–11. 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)12331-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michaëlsson K, Melhus H, Warensjö Lemming E, et al. . Long term calcium intake and rates of all cause and cardiovascular mortality: community based prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ 2013;346:f228 10.1136/bmj.f228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collage RD, Howell GM, Zhang X, et al. . Calcium supplementation during sepsis exacerbates organ failure and mortality via calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase signaling. Crit Care Med 2013;41:e352–60. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828cf436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan S-di, Liu X-J, Peng Y, et al. . Admission serum calcium levels improve the grace risk score prediction of hospital mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Clin Cardiol 2016;39:516–23. 10.1002/clc.22557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miura S, Yoshihisa A, Takiguchi M, et al. . Association of hypocalcemia with mortality in hospitalized patients with heart failure and chronic kidney disease. J Card Fail 2015;21:621–7. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ladenson JH, Lewis JW, Boyd JC. Failure of total calcium corrected for protein, albumin, and pH to correctly assess free calcium status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1978;46:986–93. 10.1210/jcem-46-6-986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gauci C, Moranne O, Fouqueray B, et al. . Pitfalls of measuring total blood calcium in patients with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;19:1592–8. 10.1681/ASN.2007040449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oberleithner H, Greger R, Lang F. The effect of respiratory and metabolic acid-base changes on ionized calcium concentration: in vivo and in vitro experiments in man and rat. Eur J Clin Invest 1982;12:451–5. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1982.tb02223.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Chewcharat A, et al. . Hospital mortality and long-term mortality among hospitalized patients with various admission serum ionized calcium levels. Postgrad Med 2020:1–6. 10.1080/00325481.2020.1728980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, Mao MA, et al. . Impact of admission serum calcium levels on mortality in hospitalized patients. Endocr Res 2018;43:116–23. 10.1080/07435800.2018.1433200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakrabarti B, Calverley PMA. Management of acute ventilatory failure. Postgrad Med J 2006;82:438–45. 10.1136/pgmj.2005.043208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rochwerg B, Brochard L, Elliott MW, et al. . Official ERS/ATS clinical practice guidelines: noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J 2017;50:1602426 10.1183/13993003.02426-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Afshar M, Joyce C, Oakey A, et al. . A Computable phenotype for acute respiratory distress syndrome using natural language processing and machine learning. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2018;2018:157–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behrendt CE. Acute respiratory failure in the United States: incidence and 31-day survival. Chest 2000;118:1100–5. 10.1378/chest.118.4.1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stefan MS, Shieh M-S, Pekow PS, et al. . Epidemiology and outcomes of acute respiratory failure in the United States, 2001 to 2009: a national survey. J Hosp Med 2013;8:76–82. 10.1002/jhm.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes M, Grant IS, MacKirdy FN. Incidence and mortality after acute respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome in Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:332–3. 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.16213b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vincent J-L, Akça S, De Mendonça A, et al. . The epidemiology of acute respiratory failure in critically ill patients(*). Chest 2002;121:1602–9. 10.1378/chest.121.5.1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Chewcharat A, et al. . Admission serum phosphate levels and the risk of respiratory failure. Int J Clin Pract 2019:e13461 (published Online First: 2019/12/13). 10.1111/ijcp.13461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Chewcharat A, et al. . The association of low admission serum creatinine with the risk of respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 2019;9:18743 10.1038/s41598-019-55362-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang P, Formanek P, Scaglione S, et al. . Risk factors and outcomes of acute respiratory distress syndrome in critically ill patients with cirrhosis. Hepatol Res 2019;49:335–43. 10.1111/hepr.13240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Chewcharat A, et al. . Risk of acute respiratory failure among hospitalized patients with various admission serum albumin levels: a cohort study. Medicine 2020;99:e19352 10.1097/MD.0000000000019352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Chewcharat A, et al. . Risk of respiratory failure among hospitalized patients with various admission serum potassium levels. Hosp Pract 2020;1995:1–5. 10.1080/21548331.2020.1729621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Srivali N, et al. . Admission serum magnesium levels and the risk of acute respiratory failure. Int J Clin Pract 2015;69:1303–8. 10.1111/ijcp.12696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chernow B, Zaloga G, McFadden E, et al. . Hypocalcemia in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 1982;10:848–51. 10.1097/00003246-198212000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaloga GP. Hypocalcemia in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 1992;20:251–62. 10.1097/00003246-199202000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaloga GP, Chernow B. Hypocalcemia in critical illness. JAMA 1986;256:1924–9. 10.1001/jama.1986.03380140094029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aguilera IM, Vaughan RS. Calcium and the anaesthetist. Anaesthesia 2000;55:779–90. 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01540.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo Y, He L, Liu Y, et al. . A rare case report of multiple myeloma presenting with paralytic ileus and type II respiratory failure due to hypercalcemic crisis. Medicine 2017;96:e9215–e15. 10.1097/MD.0000000000009215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. . A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, et al. . Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1245–51. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armstrong CM, Cota G. Calcium block of Na+ channels and its effect on closing rate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:4154–7. 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Mao MA, et al. . Admission calcium levels and risk of acute kidney injury in hospitalised patients. Int J Clin Pract 2018;72:e13057 10.1111/ijcp.13057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Hansrivijit P, et al. . Impact of changes in serum calcium levels on in-hospital mortality. Medicina 2020;56:E106 10.3390/medicina56030106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newman DB, Fidahussein SS, Kashiwagi DT, et al. . Reversible cardiac dysfunction associated with hypocalcemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Heart Fail Rev 2014;19:199–205. 10.1007/s10741-013-9371-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moe SM. Disorders involving calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium. Prim Care 2008;35:215–37. 10.1016/j.pop.2008.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baird GS. Ionized calcium. Clinica Chimica Acta 2011;412:696–701. 10.1016/j.cca.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stefanidis C, Martineau AR, Nwokoro C, et al. . Vitamin D for secondary prevention of acute wheeze attacks in preschool and school-age children. Thorax 2019;74:977–85. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-213278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martineau AR, Jolliffe DA, Greenberg L, et al. . Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory infections: individual participant data meta-analysis. Health Technol Assess 2019;23:1–44. 10.3310/hta23020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jolliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, et al. . Vitamin D to prevent exacerbations of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised controlled trials. Thorax 2019;74:337–45. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-034325supp001.pdf (317.6KB, pdf)