Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is recognized as a major health hazard that mostly affects people older than 60 years. AD is one of the biggest medical, economic, and social concerns to patients and their caregivers. AD was ranked as the 5th leading cause of global deaths in 2016 by the World Health Organization (WHO). Many drugs targeting the production, aggregation, and clearance of Aβ plaques failed to give any conclusive clinical outcomes. This mainly stems from the fact that AD is not a disease attributed to a single-gene mutation. Two hallmarks of AD, Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), can simultaneously induce other AD etiologies where every pathway is a loop of consequential events. Therefore, the focus of recent AD research has shifted to exploring other etiologies, such as neuroinflammation and central hyperexcitability. Neuroinflammation results from the hyperactivation of microglia and astrocytes that release pro-inflammatory cytokines due to the neurological insults caused by Aβ plaques and NFTs, eventually leading to synaptic dysfunction and neuronal death. This review will report the failures and side effects of many anti-Aβ drugs. In addition, emerging treatments targeting neuroinflammation in AD, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), that restore calcium dyshomeostasis and microglia physiological function in clearing Aβ plaques, respectively, will be deliberately discussed. Other novel pharmacotherapy strategies in treating AD, including disease-modifying agents (DMTs), repurposing of medications used to treat non-AD illnesses, and multi target-directed ligands (MTDLs) are also reviewed. These approaches open new doors to the development of AD therapy, especially combination therapy that can cater for several targets simultaneously, hence effectively slowing or stopping AD.

Keywords: pharmacotherapy, Alzheimer’s disease, Alzheimer, neuroinflammation, amyloid, tau protein, glutamate

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disease that usually affects people older than 60 years. The etiologies of many neurodegenerative diseases are not limited to a single gene or pathway, but are rather an intricate network of causatives, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, protein misfolding, and aggregation that can lead to cell death (Wu et al., 2018; Kamil et al., 2019). Various mechanisms were associated with the sporadic form of AD, which accounts for most AD cases, whereas mutations of three genes, including amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1 (PS1), and presenilin 2 (PS2) are heavily linked with familial AD cases (Newman et al., 2017). The irreversible symptoms of AD, such as progressive deterioration of intellect, memory, and attentiveness, are noticeable when both NFTs and Aβ plaques have disseminated through the limbic system (Canter et al., 2016).

Aβ plaques-induced brain atrophy begins with the loss of synapses and enlargement of the ventricles (Ramos-Rodriguez et al., 2017), whereas NFTs are often associated with grey matter loss (Bejanin et al., 2017). Progressive loss of cortical interneurons and specific neurotransmitter pathways such as acetylcholine (ACh), noradrenaline (NA), and serotonin (5-HT) are also reported in AD (Ribeiro et al., 2017). In the early stages of AD, typically around age 70, cells in the hippocampus start to degenerate, causing mild forgetfulness of recent events and familiar names, and also difficulty in solving simple mathematical problems (Selkoe, 2011; Bie et al., 2018). After 10 years, atrophy of the cerebral cortex occurs in moderate AD stage, resulting in a decline in language, emotional outbursts, impaired ability in conducting simple tasks such as combing hair and buttoning shirts, and an inability to think clearly. In advanced stages of AD, where more nerve cells have undergone degeneration, patients are often agitated, wandering, and unable to recognize faces and communicate (Braak and Tredici, 2018).

AD-related deaths have markedly increased over the past two decades, but a cure remains elusive (Alzheimer's Association, 2019). Treatment options for AD that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) do not have a curative effect or are able to slow down the progression of the disease (Folch et al., 2018a). The most commonly prescribed drugs are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs), such as tacrine, donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine, and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAr) antagonists, such as memantine (Morsy and Trippier, 2018; Table 1). Tacrine was eventually discontinued due to its hepatotoxicity, and tacrine hybrids are now being studied (Sameem et al., 2017). AChEIs delay the metabolism of ACh by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase (AChE) as AD patients have a deficiency of ACh (Kumar et al., 2015). Meanwhile, memantine prevents excitotoxicity by blocking NMDAr's activation (Marttinen et al., 2018).

Table 1.

Conventional available pharmacotherapy for Alzheimer's disease.

| Drug Name | Mechanism | Dosage | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tacrine | AChE inhibitor |

|

(Sameem et al., 2017) (Lopes et al., 2018) |

| Donepezil | AChE inhibitor | Mild-to-moderate AD:

|

(Masters et al., 2015) (Foster et al., 2016) (Zhang and Gordon, 2018) (Birks and Harvey, 2018) (Lee et al., 2015) |

| Rivastigmine | AChE inhibitor | Mild-to-moderate AD:

|

(Birks and Evans, 2015) (Chang et al., 2019) |

| Galantamine | AChE inhibitor | Mild-to-moderate AD:

|

(Wake et al., 2016) (Nakayama et al., 2017) (Ohta et al., 2017) (Blautzik et al., 2016) (Oka et al., 2016) |

| Memantine | N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist | Moderate-to-severe AD:

|

(Wong et al., 2016) (Schmitt et al., 2018) (Deardorff and Grossberg, 2016) (Folch et al., 2018b) (Knight et al., 2018) (Kanasty et al., 2019) |

q.i.d., four times a day; q.d., once a day; b.i.d., twice a day.

Heterogeneity in AD pathogenesis impedes the development of curative strategies. Three neuropathological mechanisms postulated in AD are: i) formation of extracellular Aβ plaques by insoluble amyloid proteins' aggregate, ii) formation of NFTs (disorganized bundles of filaments in the neuronal cytoplasm) by hyperphosphorylated tau proteins, and iii) neuronal loss as the aftermath of the Aβ plaques and NFTs (Revett et al., 2013). Thus, many drugs failed to improve cognition in mild-to-moderate AD patients as the drugs target a single pathology without acknowledging other neurological insults (Jobke et al., 2018). Hence, a multi-target approach is being highly investigated in clinical trials to synergistically target distinct pathways and ameliorate AD (Cummings et al., 2019).

Amyloid Plaques

Overproduction and reduced clearance of Aβ42 monomers cause the deposition of Aβ plaques that eventually leads to alteration in downstream neurobiological events (Takahashi et al., 2017). Aβ plaques cause catastrophic damage to cellular membranes' integrity through the formation of the membrane's pore and the reduction of the membrane's fluidity, hence, leading to neuronal death (Yasumoto et al., 2019). Aβ plaques also trigger the activation of microglia and astrocyte as an inflammatory response, alter the neuronal calcium homeostasis causing oxidative injury, and disrupt the protein kinase and phosphatase-related pathways, resulting in hyperphosphorylation of tau and formation of NFTs (Reiman, 2016). Furthermore, self-propagation of Aβ42 plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau, via a prion-like mechanism, may exaggerate the synaptic dysfunction, neurotransmitter deficits, and neuronal loss in the brain (Goedert, 2015).

Although Aβ plaques alone may not be adequate in causing the transmission of pathological tau, amyloid cascade hypothesis suggests that deposition Aβ plaques is the triggering factor for the cognitive deteriorations in AD (Blennow et al., 2015). Hence, future drug development should seek to determine whether a single-target therapy targeting Aβ is sufficient to treat AD or whether a combination therapy between anti-Aβ and anti-tau is needed (He et al., 2018).

Neurofibrillary Tangles

Intracellular NFTs are the deposits of insoluble proteins in neuronal cell bodies (Vanden Dries et al., 2017). Tau is a cytoskeletal microtubule-associated protein (MAP) that is phosphorylated at three sites - serine (S), threonine (T), and at residues adjacent to proline - and binds at the microtubules (MTs) to sustain the MTs' stability and integrity (Pradeepkiran et al., 2019). The toxicity of tau can impair neuronal function depending on its post-translational modifications. The most potent phosphorylations of tau take place at T231, S235, and S262, which results in the loss of tau's ability to bind to MTs, leading to tau self-assembly into paired helical filaments (PHF) (Iqbal et al., 2018).

Phosphorylation of tau detaches it from MTs to allow the intracellular transportation of subcellular organelles such as mitochondria and lysosomes from the nerve terminals to the cells' soma through secretory vesicles (Pradeepkiran et al., 2019). Hyperphosphorylation of tau sequesters the normal tau in which it may excessively impair tau binding and destabilize MTs, thus, impairing the axonal transport causing neurodegeneration through synaptic starvation, neurite outgrowth, and neuronal death (Minjarez et al., 2013). Hyperphosphorylated tau tends to misfold and forms PHF which eventually aggregates to form NFTs as a defense mechanism in the cell soma (Gandini et al., 2018).

In contrast to Aβ pathology, which causes hyperactivity of neurons, tau silences the neurons (Busche et al., 2019). This provokes the question on how the coexistence of Aβ and tau pathologies causes neurodegeneration in AD. From the fully eradicated neuronal hyperactivity and drastic decline of cortical activity in rats with both Aβ and tau pathologies, it can be concluded that deposition of Aβ plaques may be the triggering factor that sparks other AD etiologies, but tau pathology is the one dominating the aftermath effects of this dual proteinopathies in AD. It is tau pathology that determines the cognitive status in AD compared to Aβ pathology, which is another solid reason for the constant failures of Aβ drugs. The combination of anti-amyloid and anti-tau is crucial, as suppressing gene expression of tau is less effective in restoring the neuronal impairments in the presence of Aβ plaques (DeVos et al., 2018).

Current Drugs Targeting Aβ - Failures

According to the updated AD drug development pipeline in 2018, although more than 50% of drugs in Phase III trials are targeting Aβ, there is still a steep 40% decline from year 2017 to 2018 in anti-Aβ drugs in Phase I and II trials, which manifests the shift in AD research following the repetitive failures of anti-Aβ drugs (Mullane and Williams, 2018) (Table 2). Reducing the generation of Aβ42, inhibiting the aggregation of Aβ plaques, or increasing the rate of Aβ clearance from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and brain are the common approaches of anti-Aβ drugs (Scheltens et al., 2016). At present, the complexity of AD's pathogenesis is vaguely understood, which may involve numerous other proteins beside Aβ and various biological pathways (Doig et al., 2017). This multifactorial AD pathogenesis is most probably the main reason for the repetitive failures of anti-amyloid drugs because a single target treatment may not be able to cater for all the altered pathways involved in the neurodegenerative events (Selkoe, 2019).

Table 2.

Failed clinical trials of anti-Aβ drugs for the treatments of Alzheimer's disease.

| Name | Therapy Type | Clinical Trials | Cohort | Reason of failure | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solanezumab | IgG1 humanized anti-Aβ mAbs | III | Mild-to-moderate AD | Lack of efficacy | (Honig et al., 2018) |

| Bapineurumab | IgG1 humanized anti-Aβ mAbs | III | Mild-to-moderate AD | Lack of efficacy | (Salloway et al., 2018) (Ketter et al., 2017) |

| Crenezumab | IgG1 humanized anti-Aβ mAbs | II | Mild-to-moderate AD | Lack of efficacy, Did not meet primary and secondary endpoint. |

(Cummings et al., 2018) |

| Gantenerumab | IgG1 humanized anti-Aβ mAbs | III | Prodromal AD | Halted due to futility, no significant differences observed in primary and secondary endpoint. | (Ostrowitzki et al., 2017) |

| Aducanumab | IgG1 humanized anti-Aβ mAbs | III | Mild-to-moderate AD | Lack of efficacy | (Selkoe, 2019) (Haeberlein et al., 2018) (Sevigny et al., 2016) |

| Tramiprosate | Aβ aggregation inhibitor | II | Lack of efficacy | (Selkoe, 2011) (Sabbagh, 2017) (Kocis et al., 2017) (Malouf and Collins, 2018) |

|

| Semagacestat | γ-secretase inhibitor | III | Lack of efficacy, Worsens cognition function at higher doses, High incidence of skin cancer and infections |

(Doody et al., 2013) (Henley et al., 2014) |

|

| Verubecestat | BACE1 inhibitor | III | Mild-to-moderate AD Prodormal AD |

Lack of efficacy, Adverse events: Occurrence of rash Changes in hair color Tend to have more falls and injuries Weight loss Sleep disturbance Suicidal ideation |

(Egan et al., 2018) (Kennedy et al., 2016) |

| Lanabecestat | BACE1 inhibitor | III | Early AD Mild-to-moderate AD |

Unlikely to meet primary endpoint, stopped for futility | (Eli Lilly and Company, 2018) (Cebers et al., 2017) (Eketjall et al., 2016) |

| Atabecestat | BACE1 inhibitor | II/III | Early AD | Adverse events: Elevation of liver enzymes |

(Timmers et al., 2018) (Taylor, 2018) (Janssen, 2018) |

| Avagacestat | γ-secretase inhibitor | II | Prodromal AD | Lack of efficacy Adverse events: Weight loss Glycosuria |

(Coric et al., 2015) |

Initially, these anti-Aβ agents show potential curative effects through effective Aβ clearance in CSF and the brain during the early stage of drug development. However, the Aβ level in mild-to-moderate AD patients or even prodromal AD patients may have reached the threshold of irreversible neurotoxicity, which is the main reason for the failure of many anti-Aβ drugs once proceeded to phase III trials (Dobrowolska Zakaria and Vassar, 2018). This is probably due to lack of AD biomarkers in the past to ensure early detection and recruitment of potential AD patients for clinical trials (Folch et al., 2018b). Plus, Aβ plaques accumulate at a slow rate which may provide a large time window for a potential intervention that could either enhance the clearance or hinder the accumulation of Aβ insoluble proteins before brain atrophy and memory impairment commences (Villemagne et al., 2013). According to PET images taken by Vlassenko and colleagues, significant changes in CSF Aβ level and Aβ deposition in the brain of AD patients were reported, respectively 25 and 15 years prior to the clinical representation of AD symptoms (Vlassenko et al., 2012). This finding suggested an optimal time for early intervention of AD; hence, early treatment can be given to the presymptomatic AD patients who should have been recruited for clinical trials rather than symptomatic AD patients. This is mainly because symptomatic AD patients usually have irreversible synaptic loss and neuronal deaths. Therefore, better recruitment of patients with earlier stage of neurodegeneration and more consistent pathology underlying their AD to participate in clinical trials may generate more beneficial clinical outcomes (Briggs et al., 2016).

The targeted protein to minimize the generation of Aβ42 is β-secretase 1 (BACE1), which is involved in the first proteolytic cleavage of the APP protein and also γ-secretase which plays a role in the second cleavage in order to produce the Aβ42 protein.Verubecestat, a BACE1 inhibitor, was discontinued from the phase III trial due to its lack of efficacy and inability to establish a positive risk/benefit ratio towards mild-to-moderate and prodromal AD patients, although significant reduction of Aβ in the patients' CSF and brains were achieved during the trial (Egan et al., 2018). This finding emphasized that solely targeting amyloid may not be an appropriate strategy in treating AD. Lanabecestat is a selective BACE1 inhibitor with satisfying blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration, high potency and permeability, and slow off-rate that is critical for its efficacy (Eketjall et al., 2016). However, lanabecestat was discontinued from the trials due to its unlikeliness to meet the primary end points in mild-to-moderate and prodromal AD patients based on a recommendation from the data monitoring committee (Panza et al., 2019). Meanwhile, a phase II/III trial of a non-selective BACE1, atabecestat, was halted as the benefit/risk ratio was no longer favorable due to chronic elevations of liver enzymes observed during the trial (Taylor, 2018).

The clinical trial of semagacestat was rushed without a strong foundation of knowledge on the compound's physiological, structural, and functional properties (De Strooper, 2014). It was even more perplexing when the trial of semagacestat continued to the next phase without any significant results from the previous trial and was terminated before the completion of phase III trial. The drug was not even as effective as the placebo, aggravated cognitive deterioration at higher doses, and demonstrated high incidence of skin cancer and infections in the study group (Doody et al., 2013). The drug's adverse effects may potentially be linked to the altered Notch signaling pathway, where Notch was one of the alternate substrates for γ-secretase, important for cell differentiation. Blocking γ-secretase through semagacestat may have blocked the differentiation of cells vital for the immune system, pigmentation, and gastrointestinal functions such as B and T lymphocytes, melanocyte stem cells, and gastrointestinal epithelial cells (Henley et al., 2014). The loss of Notch signaling by semagacestat may trigger mutations responsible for the development of skin cancer in patients' groups receiving semagacestat (Nowell and Radtke, 2017).

Apart from that, tramiprosate was an anti-glycosaminoglycan compound that targeted the inhibition of Aβ aggregation studied until the phase II trial (Folch et al., 2018b). Aβ binds with glycosaminoglycan on the cell surface for cellular uptake and internalization depending on the electrostatic interaction between the positively charged Aβ and negatively charged sulfate residue on the glycoaminoglycan (Stopschinski et al., 2018). Tramiprosate was also withdrawn from the trial due to a lack of consistent cognitive improvement as measured in Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) (Aisen et al., 2011). Nevertheless, tramiprosate was found to have higher efficacy to apolipoprotein E4 homozygotes in AD patients. Therefore, a thorough molecular analysis elucidated the mechanism of action of tramiprosate in aggregate Aβ42 that may be advantageous for further development of tramiprosate as an AD therapeutic regimen (Sabbagh, 2017). Concisely, tramiprosate prevents the misfolding of self-assembled Aβ42 monomers by enveloping them, thereby hindering the aggregation of neurotoxic Aβ42 plaques (Kocis et al., 2017).

Besides, extensive development of Aβ humanized IgGI monoclonal antibodies agents, such as solanezumab and bapineuzumab, that targeted the central epitopes of soluble Aβ monomers and the N-terminus of Aβ42 were also halted due to a lack of efficacy in mild-to-moderate AD patients (Honig et al., 2018; Castellani et al., 2019). After repetitive failures in phase III clinical trials in mild-to-moderate AD patients, EXPEDITION 1, EXPEDITION 2 and EXPEDITION 3, solanezumab are currently being tested in asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic patients with biomarker evidence of Aβ plaques deposition in brains as a preventive strategy towards AD (Willis et al., 2018). A combined therapy of solanezumab and gantenerumab was also terminated due to their lack of clinical advantages and apparent side effects when combined with BACE1 inhibitor (Cummings et al., 2019). The combination therapy was initiated to enhance the immune response towards Aβ plaques, hence, promoting Aβ clearance while BACE1 inhibits the generation of new Aβ (Folch et al., 2018b). Nonetheless, there are two emerging anti-Aβ oligomers monoclonal antibodies with promising efficacy, aducanumab and BAN2401, that bind to insoluble fibrils and soluble Aβ protofibrils, thus, relieving the brains' Aβ burden with positive impact on cognition (Panza et al., 2019). Aducanumab is an Aβ-targeting monoclonal antibody that is currently showing significant dose-dependent reduction of Aβ plaques' size (Haeberlein et al., 2018). Besides binding to both forms of Aβ, soluble oligomers and insoluble fibrils, aducanumab also alleviates calcium dyshomeostasis in affected neurons, since neuronal calcium was found altered in AD brains (Gamage and Kumar, 2017). Further studies should investigate whether the alleviation of elevated intracellular calcium by aducanumab plays a role in restoring the cognitive functions in AD. In a phase III trial, aducanumab failed to slow down cognitive deterioration in mild-to-moderate patients due to reasons such as the patients were irreversibly symptomatic, targeting Aβ was not sufficient as it may have already caused irreversible synapse and microglia toxicity, and multifactorial AD may require combination therapy (Selkoe, 2019).

BAN2401 is a humanized monoclonal antibody with encouraging therapeutic effects in treating AD. The drug is highly selective to Aβ protofibrils and recedes the formation of Aβ plaques, causing a 30% delay to cognitive impairment in mild-to-moderate AD patients within 18 months and a 47% delay by the highest dose in a phase II trial (Swanson et al., 2018). However, future studies should explore the potential of this drug in a larger group (Mendes and Palmer, 2018; Panza et al., 2019).

Passive immunization is the most predominant therapeutic approach in targeting Aβ where exogenous monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are administered to the patients. However, this approach has been weighted with repetitive failures that subsequently theorized several augmentations for the anti-Aβ mAbs development (Piton et al., 2018). Firstly, mAbs targeting the N-terminus of Aβ are highly potent in suppressing the aggregation of Aβ and disaggregating the pre-existing Aβ fibrils (van Dyck, 2018). Next, better penetration through the BBB and higher doses of mAbs may be tested in the future since mAbs have astonishing safety profiles. Finally, recruiting preclinical AD patients for the prevention of AD clinical trials is one of the initiatives taken to maximize the benefits of anti-Aβ mAbs in treating AD at an early stage (Hampel et al., 2010).

Emerging Treatments: Neuroinflammation

Recently, the drive for new therapeutic strategies has focused on neuroinflammation interceded by microglia and astrocytes in AD pathogenesis, rather than the accustomed AD hypotheses such as Aβ and tau pathologies. This has resulted in extensive investigations of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agents (Heneka et al., 2015). In a healthy brain, microglia provide protection against exogenous insult, while astrocytes furnish nutritional and structural support for neurons (Van Eldik et al., 2016). At the early stages of AD, excessive deposition of extracellular Aβ plaques and continuous activation of glial cells cause the release of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1α (IL-1α), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and complement protein (C1q) (Figure 1). The cytokines also increase astrocytes' expression of insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) for Aβ degradation and signal for neuronal apoptosis (Son et al., 2016). NFκB signaling cascades enhanced in glial cells of AD brain to produce various inflammatory and immune proteins, including compliment component 3 (C3) that initiates neural destruction through complement-mediated synapse pruning when it binds to C3a receptors on a neuron (Benarroch, 2018).

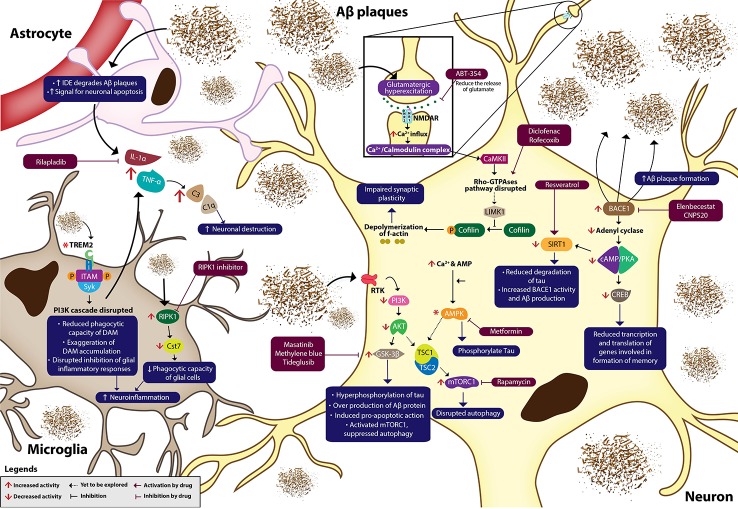

Figure 1.

Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Aβ plaques, NFTs and oxidative stress dysregulate various signaling cascades, causing neuroinflammation, and eventually neurodegeneration. Multiple novel pharmacotherapies ameliorate AD by normalizing the dysregulated signaling pathways in AD. IDE, insulin-degrading enzyme; Aβ, amyloid βeta; IL-1α, interleukin 1α; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-α; C3, complement component 3; C1q, complement protein 1q; TREM2, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2; ITAM, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase; P, phosphate; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; NFκB, nuclear factor kappa β; RIPK1, receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1; Cst7, cystatin F gene; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; PDK1, phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1; mTOR, mammalian Target of Rapamycin; Akt, protein kinase B; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; SIRT1, silent information regulator type 1; BACE1, β-secretase 1; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; PKA, protein kinase A; CREB, cAMP response element binding protein; NMDAR, NMDA receptor; Ca²⁺/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMKII); LIMK1, LIM kinase 1; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Asterisk (*) in the diagram indicates uncertain changes of activity in AD.

Constant production of inflammatory cytokines by microglia leads to neuroinflammation and synaptic loss. Neuroinflammation suppresses the phagocytosis of Aβ plaques which may aggravate neurodegeneration (Cianciulli et al., 2020). Despite the undefined mechanism of rilapladib, it is presumed that rilapladib reduces neuroinflammation through the reduction of proinflammatory cytokines and restoration of BBB integrity (Maher-Edwards et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2020).

Microglia are activated into disease-associated microglia (DAM) through triggering receptors expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) independent and dependent pathways during the microglia-Aβ plaques interaction, which facilitate Aβ plaques phagocytosis and suppresses overproduction of inflammatory cytokines (Keren-Shaul et al., 2017). Activation of TREM2 leads to the phosphorylation of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) that causes the spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) to dock within the receptor complex and activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) cascades (Zheng et al., 2018). The initial response following the activation of PI3K pathway was to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines as a neuroprotective feedback (Cianciulli et al., 2016). Several studies reported that mutations of TREM2 in AD reduced the phagocytic capacity of DAM, disrupted the downstream PI3K pathway, and impaired suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines released by the glial cells (Jay et al., 2017; Achebe et al., 2018). Meanwhile, overexpression of TREM2 ameliorated neuroinflammation by inhibiting the pro-inflammatory responses initiated by microglia (Ren et al., 2018).

In addition, restoring the microglia function in Aβ clearance may open new doors for the development of AD treatments through inhibiting receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) that are highly expressed in microglia of AD brains (Mullard, 2018). Inhibition of RIPK1 reduces the overexpression of Cst7 that encodes for cystatin F, an endosomal/lysosomal cathepsin inhibitor, which reduces the phagocytic capacity of primary immune cells (Ofengeim et al., 2017). Therefore, RIPK1 inhibitor is suggested to encounter neuroinflammation caused by inflamed microglia that disrupts the phagocytosis of toxic dead cells by reducing the expression of Cst 7 and escalating Aβ plaques clearance.

Overstimulation of glutamate receptors leads to the progression of many CNS-related complications (Kumar et al., 2018a; Kumar et al., 2018b). Aβ plaques cause glutamatergic hyperexcitation through continuous stimulation of NMDAr that results in its desensitization and an increase in Ca2+ influx (Wang X. P. et al., 2019). NSAIDs such as diclofenac and rofecoxib were said to be a potential strategy in combating neuroinflammation by regulating Ca2+ homeostasis, tau phosphorylation, axonal growth, and astrocyte motility through Rho-GTPases pathway (Kumar et al., 2015). The binding of Ca2+ with calmodulin forms Ca2+/Calmodulin complex, which subsequently activates Ca²⁺/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMKII) and Rho-GTPases pathway, which is important for in spine morphogenesis during the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) (Luo et al., 2016). LIM kinase 1 (LIMK1), a downstream kinase in Rho-GTPases pathway, phosphorylates and inhibits cofilin, a protein involved in the depolymerization of f-actin (Fan et al., 2018). Aβ was reported to disrupt the Rho-GTPases pathway, which regulates the dynamic of polymerization and depolymerization of f-actin to maintain the neurons' morphology (Ferrera et al., 2017). Meanwhile, ibuprofen was shown to phosphorylate cofilin at S3 to inhibit cofilin, thus, preventing the depolymerization of f-actin and impairment of synaptic plasticity. Besides, NSAIDs also suppress the microglial activation and lessen the accumulation of activated microglia (O'Bryant et al., 2018). But, NSAIDs tend to cause toxicity due to its non-selective activity. In addition, rofecoxib, a specific cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor was studied in AD as COX-2 mRNAs were upregulated in AD brains (Wang et al., 2015). Inhibiting COX-2 may also hinder the decline of LTP provoked by the deposition of Aβ in the hippocampus (Deardorff and Grossberg, 2017).

Besides, phenolic compounds with antioxidant properties such as oleuropein and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) are also of interest for early intervention in AD management (Kamil et al., 2018). This is mainly because a significant deficiency in brain antioxidant levels was identified as the oxidative stress marker in AD (Sharman et al., 2019). For instance, EGCG was said to suppress the Aβ plaque-induced upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines in microglia, and also upregulate the expression of endogenous antioxidants such as nuclear arythroid-2 related factor 2 (Nrf2) and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1). Hence, EGCG elicits a protective effect against oxidative stress and neuroinflammation (Cheng-Chung Wei et al., 2016).

Novel Pharmacology: Molecular Targets

Development of novel AD pharmacotherapy is becoming profoundly important as the complexity of AD pathogenesis becomes better understood in recent times, resulting in the exploration of multitude targets in AD therapeutic strategies (Table 3). The pipeline of AD treatments is augmented with compounds that either modify the underlying AD pathophysiology, target several molecular targets synergistically, or repurposed as an anti-Alzheimer's drug (Bachurin etal., 2017).

Table 3.

Novel clinical trials for Alzheimer's disease.

| Name | Mechanism | Clinical trials | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Masatinib (AB1010) |

GSK-3β Inhibitor Tyrosine kinase inhibitor target mast cells and macrophages. |

Phase II/III trial on mild-to-moderate AD patients Escalated dose: 4.5 mg/kg/day b.i.d., escalate to 6 mg/kg/day after 3 months' treatment Fixed dose: 4.5 mg/kg/day b.i.d. and 3.0 mg/kg/day b.i.d. Primary endpoint:

|

(Palomo et al., 2017) (AB Science SA, 2019) (Folch et al., 2015) |

| Methylene blue (MB) NCT02380573 |

Inhibit the formation of tau oligomers | Phase II clinical trial on healthy aging, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and mild AD patients Primary endpoint:

|

(Cummings et al., 2019) (Soeda et al., 2019) (Gauthier et al., 2016) |

| Metformin NCT01965756 |

Biguanide class medication Decrease insulin level that affect the clearance of Aβ in brain Decrease advanced glycation end products and inflammation in AD |

Phase II clinical trial on MCI and early AD patients Metformin > Placebo oral metformin for 8 weeks (500 mg q.d. for 1 week, increased dose by 500 mg per week until a maximum dose of 2000 mg per day), followed by 8 weeks of placebo Placebo > Metformin After 8 weeks of placebo, oral metformin for 8 weeks (500 mg q.d. for 1 week, increased dose by 500 mg per week until a maximum dose of 2000 mg per day) Primary endpoint:

|

(Ou et al., 2018) (Luchsinger et al., 2016) (Campbell et al., 2017) (Weinstein et al., 2019) |

| RPEL | Improve inhibition of AChE, reduce Aβ aggregation and reduce phosphorylation of tau | In vivo and in vitro studies | (Sergeant et al., 2019) |

| Tideglusib NCT01350362 |

Thiadiazolidinone acts as an GSK-3β inhibitor, reduce tau phosphorylation and prevent neurons apoptosis. Anti-inflammatory |

Phase II clinical trial on mild-to-moderate AD patients for 26 weeks Oral tideglusib 1000 mg q.d. Oral tideglusib 1000 mg.q.o.d. once every other day Oral tideglusib 500 mg q.d. Placebo q.d. Primary endpoint: ADAS-Cog+ |

(Del Ser et al., 2013) (Wang and Mandelkow, 2016) |

| Elenbecestat NCT03036280 |

BACE1 inhibitor that inhibit BACE1 involved in amyloid precursor protein (APP) proteolytic cleavage during the formation of Aβ | Phase II clinical trial on prodromal AD and mild-to-moderate AD patients Phase III clinical trial on early AD patients Dosage: 50 mg q.d in the morning MissionAD1 and MissionAD2 - Phase III trial on early AD with positive biomarkers for brain amyloid pathology. Primary endpoint: CDR-SB Contact dermatitis, upper respiratory infection, headache, diarrhea, fall and dermatitis. |

(Folch et al., 2018b) (Panza et al., 2018) |

| BAN2401 NCT03887455 |

IgG1 humanized anti-Aβ mAbs that binds selectively to Aβ protofibrils. | Phase III clinical trial on early AD patients Dosage: 10 mg/kg i.v. BAN2401 biweekly Primary endpoint:

|

(BioArctic AB and Eisai Co., 2019) (Swanson et al., 2018) (Logovinsky et al., 2016) |

| CT1812 NCT03522129 |

Lipophilic isoindoline that bind allosterically to sigma-2 receptor complex and destabilize the Aβ oligomers binding at synapses' neuronal receptors. | Phase I clinical trial on mild-to-moderate AD patients Dosage: 90 mg, 280 mg, 560 mg CT1812 Primary endpoint:

|

(Grundman et al., 2019) (Catalano et al., 2017) |

| Nilotinib NCT02947893 |

Inhibit brain Aβ, Decrease Aβ and pTau Modulate brain and peripheral immune profiles Reverse cognitive decline in AD |

Phase II clinical trial on mild-to-moderate AD patients Dosage: oral 150 mg/capsule nilotinib q.d, 2 capsules after 6 months of 1 capsule Primary endpoint:

|

(Weinstein, 2018) (Pagan et al., 2016) (Nishioka et al., 2016) |

| Acitretin NCT01078168 |

α-secretase enhancer/amyloid aggregation inhibitor, Retinoic acid receptor agonist | Phase II clinical trial on mild-to-moderate AD patients Dosage: oral 30 mg q.d. Primary endpoint:

|

(dos Santos Guilherme et al., 2019) (Freese et al., 2014) |

| Pinitol(NIC5-15) NCT00470418 |

α-secretase inhibitor that is Notch sparing | Phase II clinical trial on AD patients Primary endpoint:

|

(Anandakumar et al., 2018) (López-Sánchez et al, 2018) |

| Bryostatin NCT02431468 |

α-secretase enhancer, PKC modulator – immunomodulatory effect, increase cognitive ability | Phase II clinical trial on moderately severe-to-severe AD patients Dosage: 20 & 40 μg Bryostatin, i.v. Primary endpoint:

|

(Farlow et al., 2019) |

| Bexarotene NCT01782742 |

Retinoid X receptors (RXR) agonist to reduce Aβ in the brain | Phase II clinical trial on mild-to-moderate AD patients Dosage: 75 mg of bexarotene b.i.d., 150 mg after 1 week Primary endpoint:

|

(Cummings et al., 2016) |

| ELND005 (formerly known as AZD-103), scyllo-inositol NCT01735630 |

Inhibit the build-up of amyloid protein in AD brains | Phase II clinical trial on moderate-to-severe AD patients Dosage: ELND005 tablets, b.i.d. for 12 weeks Primary endpoint:

|

(Lee et al., 2017) |

| ABT-354 NCT01908010 |

5-HT6 antagonist regulate the release of acetylcholine, glutamate and noradrenaline in the forebrain region. | Phase I clinical trial on mild-to-moderate AD patients Primary endpoint:

|

(Ferrera et al., 2017) (Lalut et al., 2017) |

| CNP520 NCT03131453 |

BACE1 Inhibitor | Generation Study 2 – Phase II/III trial on homozygotes APOE ϵ4 and heterozygotes APOE ϵ4 carriers with elevated brain amyloid. Dosage: p.o. 15 mg/day or 50 mg/day CNP520 Primary endpoint:

|

(Lopez et al., 2019) (Panza et al., 2018) (Borowsky et al., 2019) |

| Crenezumab NCT02670083 |

Amyloid monoclonal antibodies | Phase III clinical trial on prodromal to lid AD patients Dosage: i.v. crenezumab q4w for 100 weeks Primary endpoint:

|

(Cummings et al., 2018) |

| Rilapladib NCT01428453 |

Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2) inhibitor that suppress neuroinflammation | Phase IIa clinical trial on AD patients Dosage: 250 mg rilapladib Primary endpoint: Change in

|

(Maher-Edwards et al., 2015) |

| Edonerpic Maleate (T-817MA) NCT02079909 |

Activate sigma-1 receptor and regulate the microglial function. | Phase II clinical trial on mild-to-moderate AD patients Dosage: 224 mg of T-817MA q.d., 448 mg after 4 weeks Primary endpoint: Change in

|

(Schneider et al., 2019) |

| Carvedilol NCT01354444 |

Non-selective B-adrenergic receptor blocker that indirectly reduce neurons' apoptosis. | Phase IV clinical trial on AD patients Dosage: 25 mg of carvediol daily Primary endpoint:

|

(Liu and Wang, 2018) |

| Intepirdine (RVT-101) NCT02585934 |

5-HT6 antagonist | Phase III clinical trial on AD patients Dosage: 35 mg of oral RVT-101 q.d. Primary endpoint: Change in

|

(Lombardo et al., 2017a) (Lombardo et al., 2017b) (Zhu et al., 2017) |

| Vanutide Cridificar (ACC-001) NCT00479557 |

Vaccine that produce Aβ-directed B-cell response. | Phase II clinical trial on mild-to-moderate AD patients Dosage: 3, 10, 30 μg IM on day 1, month 1, 3,6, and 12 Primary endpoint:

|

(Pasquier et al., 2016) |

| Resveratrol NCT01504854 |

SIRT1 potent activator acts as anti-inflammatory | Phase II clinical trial on mild-to-moderate AD patients Dosage: 500 mg oral resveratrol q.d. Primary endpoint:

|

(Drygalski et al., 2018) (Moussa et al., 2017) (Turner et al., 2015) |

Other potential treatments for AD include those based on the inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) to attenuate neuroinflammation by increasing Aβ clearance and decreasing tau phosphorylation (Modrego and Lobo, 2019). Normally, extracellular ligands bind to a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTKs), which activate PI3K signaling cascades and lead to the activation of PDK-1 and Akt. PDK1 also indirectly activates the mTORC2 complex which activates Akt through the phosphorylation of the kinase at S473 and S450. Active Akt phosphorylates and activates tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) 1 and 2, a negative regulator of mTORC1 (Hermida et al., 2017). mTOR inhibition activates the ubiquitin proteasome system and autophagy. In AD brain, where PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is downregulated due to Aβ plaques-induced neurotoxicity, Akt is suppressed and mTORC1 activity is increased, which disrupts cell autophagy, leading to neuroinflammation (Shal et al., 2018). Wang and colleagues reported rapamycin's (mTORC1 inhibitor) ability to inhibit elevated activation of mTORC1 and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the hippocampus of AD rats (Wang et al., 2016). Suppressed Akt also promotes activation of GSK-3β to cause hyperphosphorylation of tau that aggregates to form NFTs once detached from the microtubules. The loss of microtubules' integrity induces neuroinflammation and increases the risk of neuronal death (Mancinelli et al., 2017).

Methylene blue (MB) is one of the anti-tau disease modifying agents (DMTs) that combats tau pathology through two molecular targets: GSK-3β and tau aggregation (Gandini et al., 2018). Hyperphosphorylation of tau is associated with the loss of counterbalance between the kinases and phosphatases involved in tau phosphorylation, especially if the phosphorylation takes place at the sites of kinases as this family of enzymes regulate most of the protein function (Pradeepkiran et al., 2019). Kinases involved in tau phosphorylation are mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks), GSK-3β, and protein kinase A (PKA) (Kheiri et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018).

Initially, MB was well-known for its inhibiting activity on tau aggregation in AD clinical trials (Gureev et al., 2019). In spite of the advance in knowledge on tau pathology, partial inhibition on tau aggregation by MB is not adequate to halt AD as the underlying event that causes tau-mediated neurotoxicity is the binding of granular tau oligomers during NFT formation (Soeda et al., 2019).

Binding of Aβ plaques or glutamate to synaptic receptors can initiate the production of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) from adenylyl cyclase, activating the cAMP/PKA pathway. Under normal conditions, downstream cAMP/PKA pathway results in phosphorylation of transcription factors such as cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) at S133, which stimulates transcription and translation of genes involved in the formation of memory (Bartolotti et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2018). However, the level of p-PKA was significantly decreased in the hippocampus of AD mice while neuroinflammation was found to be increased (Cai et al., 2018). Decreased PKA subsequently decreased the phosphorylated CREB in the rats' hippocampus (Huang et al., 2019). High levels of BACE1 in AD brain inhibits adenylyl cyclase and impairs cAMP/PKA pathway, which interrupts the phosphorylation and eventually disrupts the transcription and translation of CREB-induced genes, leading to memory impairment in AD (Chen et al., 2012). CREB activation can restore memory impairment in AD as the CREB-induced genes, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and insulin-like growth factor 1, can enhance neuron morphological outgrowth and formation of long-term and short-term memories (Kubota et al., 2017).

Metformin is a first-line medication for type 2 diabetes, which was repurposed for AD treatment as it exhibits anti-inflammatory properties and neuroprotective features against cognitive deterioration in AD (Ou et al., 2018). Metformin hinders the neuronal apoptosis and promotes neurogenesis in the hippocampus through the activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathways, which leads to the improvement of memory formation. AMPK can be phosphorylated by 3 key kinases, such as the liver kinase B1 (LKB1) complex at T172, due to increased cytoplasmic level of AMP, increased cytosolic Ca2+, and mitogen-activated protein kinase 7 (MAP3K7), also known as transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) (Wang X. et al., 2019). AMPK also activates TSC1/2 complex that inhibits mTOR (Wang X. et al., 2019). Activity of AMPK was decreased in the hippocampus of AD rats at age 4-5 months, while the activity of mTOR increased, causing disrupted cell autophagy and exacerbated AD (Du et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2019). Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin restores normal cell autophagy and protein synthesis (Sun et al., 2018).

PKA was found to activate silent information regulator type 1 (SIRT1), a neuroprotective protein deacetylase that reduces tau acetylation and downregulates BACE1, hence, increasing degradation of tau and reducing Aβ production (Zhang et al., 2019; Wang X. et al., 2019). Resveratrol, through activation of SIRT1, reverses the drastic decrease in hippocampal expression of SIRT1 in AD (Turner et al., 2015; Hou et al., 2017). Resveratrol was also found to reduce neuronal apoptosis and eventually restore cognitive impairment in AD (Tian et al., 2016).

Current DMTs target either Aβ pathology or tau pathology, which may be the reason for their lack of efficacy since both pathologies synergistically cause cognitive degeneration with the cholinergic deficit as a constant concern in AD. Multi target-directed ligand (MTDLs) is a novel approach to surmount the multifactorial AD pathogenesis (Geldenhuys and Darvesh, 2015). RPEL was synthesized through the combination of N, N'-disubstituted piperazine anti-amyloid scaffold and tacrine, into one compound (Sergeant et al., 2019). It was found effective in preventing cognitive impairment as it minimizes the Aβ plaques formation and tau phosphorylation in AD mice without any adverse effect besides maintaining the inhibitory activity on AChE. This approach accelerates the development of potential treatment for AD by minimizing the cost and time since the individual therapeutic effects of each compound is generally known (Hassan et al., 2019).

Conclusion

Despite decades of research, we are still encountering a lack of success in pharmacotherapy of AD, mostly due to the multifactorial etiologies of the disorder that can initiate neurodegeneration interdependently. At present, combination therapy targeting several factors simultaneously appears to be promising. Additionally, an increasing number of studies are also focusing on neuroprotection against neuroinflammation. The impact of neuroinflammation interceded by microglia and astrocytes in AD pathogenesis is of great interest as it opens new doors for novel therapeutic targets. In addition to pharmacotherapy, better prognosis through early detection of AD biomarkers or brain imaging will enable early intervention that could potentially prevent the deposition of Aβ plaques and manifestations of various irreversible symptoms of AD.

Author Contributions

NI and JK performed the literature search and drafted the manuscript. MY, WM, ST, and CH reviewed and finalized the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the GUP-2018-055. Fund provided by the National University of Malaysia (UKM).

Conflict of Interest

CH was employed by Glyco Food Sdn Bhd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Ernie for critically reviewing the manuscript and Dr Khidir Kamil for designing the figure.

References

- AB Science SA (2019). The masitinib phase 3 study in Alzheimer's disease has completed patient recruitment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1–2

- Achebe N., Puntambekar S. S., Lamb B. T. (2018). A TREM2 dependent control of Microglial and Astrocytic responses in a mouse model of Alzheimer's Disease. Proc. IMPRS, 1 (1). 10.18060/22648 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aisen P. S., Gauthier S., Ferris S. H., Saumier D., Haine D., Garceau D., et al. (2011). Tramiprosate in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease - A randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled, multi-centre study (the Alphase study). Arch. Med. Sci. 7 (1), 102–111. 10.5114/aoms.2011.20612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer's Association (2019). Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures: 2019. Alzheimer ‘s Dementia 15 (3), 321–387. 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anandakumar P., Vanitha M. K., Gizaw M., Dereje G. (2018). A review on the diverse effects of D-Pinitol. Adv. J. Pharm. Life Sci. Res. 6 (1), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bachurin S. O., Bovina E. V., Ustyugov A. A. (2017). Drugs in clinical trials for Alzheimer's disease: The major trends. Med. Res. Rev. 37 (5), 1186–1225. 10.1002/med.21434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolotti N., Bennett D. A., Lazarov O. (2016). Reduced pCREB in Alzheimer's disease prefrontal cortex is reflected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Mol. Psychiatry 21 (9), 1158–1166. 10.1038/mp.2016.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejanin A., Schonhaut D. R., La Joie R., Kramer J. H., Baker S. L., Sosa N., et al. (2017). Tau pathology and neurodegeneration contribute to cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease. Brain 140 (12), 3286–3300. 10.1093/brain/awx243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benarroch E. E. (2018). Glutamatergic synaptic plasticity and dysfunction in Alzheimer disease: Emerging mechanisms. Neurology 91 (3), 125–132. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bie B., Wu J., Foss J. F., Naguib M. (2018). Amyloid fibrils induce dysfunction of hippocampal glutamatergic silent synapses. Hippocampus 28 (8), 549–556. 10.1002/hipo.22955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BioArctic AB. Eisai Co., L (2019). Press release: BioArctic and Eisai present new data regarding BAN2401 at the Alzheimer's Association International Conference 2019. Stockholm: BioAcrtic. [Google Scholar]

- Birks J. S., Evans J. G. (2015). Rivastigmine for Alzheimer's disease (Review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (Online) 2015 (4), 1–198. 10.1002/14651858.CD001191.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birks J. S., Harvey R. (2018). Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer's disease (Review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018 (6), 1–338. 10.1002/14651858.CD001190.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blautzik J., Keeser D., Paolini M., Kirsch V., Berman A., Coates U., et al. (2016). Functional connectivity increase in the default-mode network of patients with Alzheimer's disease after long-term treatment with Galantamine. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 26 (3), 602–613. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K., Mattsson N., Schöll M., Hansson O., Zetterberg H. (2015). Amyloid biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 36 (5), 297–309. 10.1016/j.tips.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky B., Lopez C. L., Tariot P., Caputo A., Liu F., Riviere M.-E., et al. (2019). The Alzheimer Prevention Initiative Generation Program: Evaluation of CNP520 in Preclinical Alzheimer's Disease (4.1-005). Neurology 92 (15 Supplement). 4.1-005. [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Tredici ,. K. D. (2018). Spreading of Tau Pathology in Sporadic Alzheimer's Disease Along Cortico-cortical Top-Down Connections. Cereb. Cortex 28 (9), 3372–3384. 10.1093/cercor/bhy152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs R., Kennelly S. P., Neill D. O. (2016). Drug Treatments Alzheimer ‘s Disease. Clin. Med. 16 (3), 247–253. 10.7861/clinmedicine.16-3-247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busche M. A., Wegmann S., Dujardin S., Commins C., Schiantarelli J., Klickstein N., et al. (2019). Tau impairs neural circuits, dominating amyloid-β effects, in Alzheimer models in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 22 (1), 57–64. 10.1038/s41593-018-0289-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H. Y., Yang J. T., Wang Z. J., Zhang J., Yang W., Wu M. N., et al. (2018). Lixisenatide reduces amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles and neuroinflammation in an APP/PS1/tau mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 495 (1), 1034–1040. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.11.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. M., Stephenson M. D., de Courten B., Chapman I., Bellman S. M., Aromataris E. (2017). Metformin and Alzheimer's disease, dementia and cognitive impairment: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 15 (8), 2055–2059. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canter R. G., Penney J., Tsai L. H. (2016). The road to restoring neural circuits for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Nature 539 (7628), 187–196. 10.1038/nature20412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani R. J., Plascencia-Villa G., Perry G. (2019). The amyloid cascade and Alzheimer's disease therapeutics: theory versus observation. Lab. Invest. 99 (7), 958–970. 10.1038/s41374-019-0231-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S., Grundman M., Schneider L. S., Higgin M., Pribyl J., Mozzoni K. (2017). A phase 1 safety trial of the ab oligomer receptor antagonist CT1812. Alzheimer's & Dementia. J. Alzheimer's Assoc. 13 (7), P1570. 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.07.730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebers G., Alexander R. C., Haeberlein S. B., Han D., Goldwater R., Ereshefsky L., et al. (2017). AZD3293: Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamix effects in healthy subjects and patients with Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 55 (3), 1039–1053. 10.3233/JAD-160701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.-C., Peng G.-S., Lai T.-J., Li C.-H., Liu C.-K. (2019). A 48-Week, Multicenter, Open-Label, Observational Study Evaluating Oral Rivastigmine in Patients with Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer's Disease in Taiwan. Adv. Ther. 36 (6), 1455–1464. 10.1007/s12325-019-00939-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Huang X., Zhang Y. W., Rockenstein E., Bu G., Golde T. E., et al. (2012). Alzheimer's β-secretase (BACE1) regulates the cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway independently of β-amyloid. J. Neurosci. 32 (33), 11390–11395. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0757-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng-Chung Wei J., Huang H. C., Chen W. J., Huang C. N., Peng C. H., Lin C. L. (2016). Epigallocatechin gallate attenuates amyloid β-induced inflammation and neurotoxicity in EOC 13.31 microglia. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 770, 16–24. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.11.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianciulli A., Calvello R., Porro C., Trotta T., Salvatore R., Panaro M. A. (2016). PI3k/Akt signalling pathway plays a crucial role in the anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin in LPS-activated microglia. Int. Immunopharmacol. 36, 282–290. 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianciulli A., Porro C., Calvello R., Trotta T., Lofrumento D. D., Panaro M. A. (2020). Microglia Mediated Neuroinflammation: Focus on PI3K Modulation. Biomolecules 10 (1), 137. 10.3390/biom10010137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coric V., Salloway S., Van Dyck C. H., Dubois B., Andreasen N., Brody M., et al. (2015). Targeting prodromal Alzheimer disease with avagacestat: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 72 (11), 1324–1333. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. L., Zhong K., Kinney J. W., Heaney C., Moll-Tudla J., Joshi A., et al. (2016). Double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept trial of bexarotene Xin moderate Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 8 (4), 1–9. 10.1186/s13195-016-0173-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. L., Cohen S., van Dyck C. H., Brody M., Curtis C., Cho W., et al. (2018). A phase II randomized trial of crenezumab in mild to moderate Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology 90 (21), e1889–e1897. 10.1212/wnl.0000000000005550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. L., Tong G., Ballard C. (2019). Treatment combinations for Alzheimer's disease: current and future pharmacotherapy options. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 67 (3), 779–794. 10.3233/JAD-180766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B. (2014). Lessons from a failed γ-secretase Alzheimer trial. Cell 159 (4), 721–726. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff W. J., Grossberg G. T. (2016). A fixed-dose combination of memantine extended-release and donepezil in the treatment of moderate-to-severe Alzheimer ‘s disease. Drug Design Dev. Ther. 10, 3267–3279. 10.2147/DDDT.S86463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff W. J., Grossberg G. T. (2017). Targeting neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for NSAIDs and novel therapeutics. Expert Rev. Neurother. 17 (1), 17–32. 10.1080/14737175.2016.1200972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Ser T., Steinwachs K. C., Gertz H. J., Andrés M. V., Gómez-Carrillo B., Medina M., et al. (2013). Treatment of Alzheimer's disease with the GSK-3 inhibitor tideglusib: A pilot study. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 33 (1), 205–215. 10.3233/JAD-2012-120805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVos S. L., Corjuc B. T., Commins C., Dujardin S., Bannon R. N., Corjuc D., et al. (2018). Tau reduction in the presence of amyloid-β prevents tau pathology and neuronal death in vivo. Brain 141 (7), 2194–2212. 10.1093/brain/awy117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrowolska Zakaria J. A., Vassar R. J. (2018). A promising, novel, and unique BACE1 inhibitor emerges in the quest to prevent Alzheimer's disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 10 (11), e9717. 10.15252/emmm.201809717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doig A. J., Del Castillo-Frias M. P., Berthoumieu O., Tarus B., Nasica-Labouze J., Sterpone F., et al. (2017). Why Is Research on Amyloid-β Failing to Give New Drugs for Alzheimer's Disease? ACS Chem. Neurosci. 8 (7), 1435–1437. 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody R. S., Raman R., Farlow M., Iwatsubo T., Vellas B., Joffe S., et al. (2013). A Phase 3 Trial of Semagacestat for Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 369 (4), 341–350. 10.1056/NEJMoa1210951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos Guilherme M., Stoye N. M., Rose-John S., Garbers C., Fellgiebel A., Endres K. (2019). The Synthetic Retinoid Acitretin Increases IL-6 in the Central Nervous System of Alzheimer Disease Model Mice and Human Patients. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11, 1–7. 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drygalski K., Fereniec E., Koryciński K., Chomentowski A., Kiełczewska A., Odrzygóźdź C., et al. (2018). Resveratrol and Alzheimer's disease. From molecular pathophysiology to clinical trials. Exp. Gerontol. 113, 36–47. 10.1016/j.exger.2018.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L. L., Chai D. M., Zhao L. N., Li X. H., Zhang F. C., Zhang H. B., et al. (2015). AMPK activation ameliorates Alzheimer's disease-like pathology and spatial memory impairment in a streptozotocin-induced Alzheimer's disease model in rats. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 43 (3), 775–784. 10.3233/JAD-140564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan M. F., Kost J., Tariot P. N., Aisen P. S., Cummings J. L., Vellas B., et al. (2018). Randomized Trial of Verubecestat for Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer's Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 378 (18), 1691–1703. 10.1056/NEJMoa1706441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eketjall S., Janson J., Kaspersson K., Bogstedt A., Kugler A. R., Alexander ,. R. C., et al. (2016). AZD3293: A Novel, Orally Active BACE1 Inhibitor with High Potency and Permeability and Markedly Slow Off-Rate Kinetics. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 50 (4), 1109–1123. 10.3233/JAD-150834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eli Lilly and Company (2018). A randomized, double-blind, delayed-start study of LY3314814 (AZD3293) in early Alzheimer's disease dementia (Extension of study AZES, the AMARANTH study). In Statistical Analysis Plan Version 3 (Vol. 18D-MC-AZF). Indianapolis, Indiana USA.

- Fan C., Zhu X., Song Q., Wang P., Liu Z., Yu S. Y. (2018). MiR-134 modulates chronic stress-induced structural plasticity and depression-like behaviors via downregulation of Limk1/cofilin signaling in rats. Neuropharmacology 131, 364–376. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farlow M. R., Thompson R. E., Wei L. J., Tuchman A. J., Grenier E., Crockford D., et al. (2019). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II study assessing safety, tolerability, and efficacy of bryostatin in the treatment of moderately severe to severe Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 67 (2), 555–570. 10.3233/JAD-180759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera P., Zepeda A., Arias C. (2017). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs attenuate amyloid-β protein-induced actin cytoskeletal reorganization through Rho signaling modulation. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 37 (7), 1311–1318. 10.1007/s10571-017-0467-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J., Petrov D., Ettcheto M., Pedrós I., Abad S., Beas-Zarate C., et al. (2015). Masitinib for the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 15 (6), 587–596. 10.1586/14737175.2015.1045419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J., Busquets O., Ettcheto M., Sanchez-Lopez E., Castro-torres R. D., Verdaguer E., et al. (2018. a). Memantine for the treatment of dementia: a review on its current and future applications. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 62 (3), 1223–1240. 10.3233/JAD-170672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J., Ettcheto M., Petrov D., Abad S., Pedrós I., Marin M., et al. (2018. b). Review of the advances in treatment for Alzheimer disease: strategies for combating β-amyloid protein. Neurología (English Edition) 33 (1), 47–58. 10.1016/j.nrleng.2015.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster P. S., Drago V., Roosa K. M., Campbell R. W., Witt J. C., Heilman K. M. (2016). Donepezil Versus Rivastigmine in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease: Attention and Working Memory. Alzheimer's Neurodegenerative Dis. 2 (1), 1–5. 10.24966/and-9608/100002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freese C., Reinhardt S., Hefner G., Unger R. E., Kirkpatrick C. J., Endres K. (2014). A novel blood-brain barrier co-culture system for drug targeting of Alzheimer's disease: Establishment by using acitretin as a model drug. PloS One 9 (3), 1–11. 10.1371/journal.pone.0091003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamage K. K., Kumar S. (2017). Aducanumab Therapy Ameliorates Calcium Overload in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease. J. Neurosci. 37 (17), 4430–4432. 10.1523/jneurosci.0420-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandini A., Bartolini M., Tedesco D., Martinez-Gonzalez L., Roca C., Campillo N. E., et al. (2018). Tau-Centric Multitarget Approach for Alzheimer's Disease: Development of First-in-Class Dual Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β and Tau-Aggregation Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 61 (17), 7640–7656. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Liu E. J., Wang W. J., Wang Y. L., Li X. G., Wang X., et al. (2018). Microglia CREB-Phosphorylation Mediates Amyloid-β-Induced Neuronal Toxicity. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 66 (1), 333–345. 10.3233/JAD-180286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier S., Feldman H. H., Schneider L. S., Wilcock G. K., Frisoni G. B., Hardlund J. H., et al. (2016). Efficacy and safety of tau-aggregation inhibitor therapy in patients with mild or moderate Alzheimer's disease: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, parallel-arm, phase 3 trial. Lancet 388 (10062), 2873–2884. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31275-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldenhuys W. J., Darvesh A. S. (2015). Pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer ‘s disease: current and future trends. Expert Rev. Neurother. 15 (1), 3–5. 10.1586/14737175.2015.990884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M. (2015). Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases: The prion concept in relation to assembled Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein. Science 349 (6248), 61–69. 10.1126/science.1255555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundman M., Morgan R., Lickliter J. D., Schneider L. S., Dekosky S., Izzo N. J., et al. (2019). A phase 1 clinical trial of the sigma-2 receptor complex allosteric antagonist CT1812, a novel therapeutic candidate for Alzheimer ‘s disease. Alzheimer's Dementia: Trans. Res. Clin. Interventions 5 (1), 20–26. 10.1016/j.trci.2018.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureev A. P., Shaforostova E. A., Popov V. N., Starkov A. A. (2019). Methylene blue does not bypass Complex III antimycin block in mouse brain mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 593 (5), 499–503. 10.1002/1873-3468.13332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeberlein S. B., Gheuens S., Chen T., O'Gorman J., von Rosenstiel P., Chiao P., et al. (2018). Aducanumab 36-month data from PRIME: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 1b study in patients with prodromal or mild Alzheimer's disease (S2.004). Neurology 90 (15 Supplement), S2.004. [Google Scholar]

- Hampel H., Frank R., Broich K., Teipel S. J., Katz R. G., Hardy J., et al. (2010). Biomarkers for alzheimer's disease: Academic, industry and regulatory perspectives. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 9 (7), 560–574. 10.1038/nrd3115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M., Raza H., Abbasi M. A., Moustafa A. A., Seo S. Y. (2019). The exploration of novel Alzheimer's therapeutic agents from the pool of FDA approved medicines using drug repositioning, enzyme inhibition and kinetic mechanism approaches. Biomed. Pharmacother. 109(September 2018, 2513–2526. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z., Guo J. L., Mcbride J. D., Narasimhan S., Kim H., Changolkar L., et al. (2018). Amyloid- β plaques enhance Alzheimer ‘s brain tau-seeded pathologies by facilitating neuritic plaque tau aggregation. Nat. Med. 24 (1), 29–38. 10.1038/nm.4443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka M. T., Carson M. J., El Khoury J., Landreth G. E., Brosseron F., Feinstein D. L., et al. (2015). Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 14 (4), 388–405. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henley D. B., Sundell K. L., Sethuraman G., Dowsett S. A., May P. C. (2014). Safety profile of semagacestat, a gamma-secretase inhibitor: IDENTITY trial findings. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 30 (10), 2021–2032. 10.1185/03007995.2014.939167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermida M. A., Kumar J. D., Leslie N. R. (2017). GSK3 and its interactions with the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling network. Adv. Biol. Regul. 65, 5–15. 10.1016/j.jbior.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honig L. S., Vellas B., Woodward M., Boada M., Bullock R., Borrie M., et al. (2018). Trial of Solanezumab for Mild Dementia Due to Alzheimer's Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 378 (4), 321–330. 10.1056/nejmoa1705971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z., He P., Imam M. U., Qi J., Tang S., Song C., et al. (2017). Edible Bird's Nest prevents menopause-related memory and cognitive decline in rats via increased hippocampal Sirtuin-1 expression. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity. 2017, 1–8. 10.1155/2017/7205082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Hu L., Li H., Huang Y., Li Y., Yang J., et al. (2019). PKA-mediated phosphorylation of CREB and NMDA receptor 2B in the hippocampus of offspring rats is involved in transmission of mental disorders across a generation. Psychiatry Res. 280, 112497. 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F., Wang K., Shen J. (2020). Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2: The story continues. Med. Res. Rev. 40 (1), 79–134. 10.1002/med.21597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal K., Liu F., Gong C. X. (2018). Recent developments with tau-based drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 13 (5), 399–410. 10.1080/17460441.2018.1445084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen (2018). Update on Janssen's BACE Inhibitor Program Regarding the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer's Network Trial (United States: DIAN-TU; ). [Google Scholar]

- Jay T. R., Hirsch A. M., Broihier M. L., Miller C. M., Neilson L. E., Ransohoff R. M., et al. (2017). Disease progression-dependent effects of TREM2 deficiency in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 37 (3), 637–647. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2110-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobke B., McBride T., Nevin L., Peiperl L., Ross A., Stone C., et al. (2018). Setbacks in Alzheimer research demand new strategies, not surrender. PloS Med. 15 (2), e1002518. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamil K., Kumar J., Yazid M. D., Idrus R. B. H. (2018). Olive and its phenolic compound as the promising neuroprotective agent. Sains Malaysiana 47 (11), 2811–2820. 10.17576/jsm-2018-4711-24 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamil K., Yazid M. D., Idrus R. B. H., Das S., Kumar J. (2019). Peripheral Demyelinating Diseases: From Biology to Translational Medicine. Front. Neurol. 10, 1–12. 10.3389/fneur.2019.00087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanasty R., Low S., Bhise N., Yang J., Peeke E., Schwarz M., et al. (2019). A pharmaceutical answer to nonadherence: Once weekly oral memantine for Alzheimer ’ s disease. J. Controll. Release 303, 34–41. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M. E., Chen X., Hodgson R. A., Hyde L. A., Kuvelkar R., Parker E. M., et al. (2016). The BACE1 inhibitor verubecestat (MK-8931) reduces CNS b-Amyloid in animal models and in Alzheimer's disease patients. Sci. Trans. Med. 8 (363), 1–14. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad9704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keren-Shaul H., Spinrad A., Weiner A., Matcovitch-Natan O., Dvir-Szternfeld R., Ulland T. K., et al. (2017). A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer's disease. Cell 169 (7), 1276–1290. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketter N., Brashear H. R., Bogert J., Di J., Miaux Y., Gass A., et al. (2017). Central Review of Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities in Two Phase III Clinical Trials of Bapineuzumab in Mild-To-Moderate Alzheimer's Disease Patients. J. Alzheimer's Dis.: JAD 57 (2), 557–573. 10.3233/JAD-160216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheiri G., Dolatshahi M., Rahmani F., Rezaei N. (2018). Role of p38/MAPKs in Alzheimer's disease: implications for amyloid beta toxicity targeted therapy. Rev. Neurosci. 30 (1), 9–30. 10.1515/revneuro-2018-0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight R., Khondoker M., Magill N., Stewart R., Landau S. (2018). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors and Memantine in Treating the Cognitive Symptoms of Dementia. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 45, 131–151. 10.1159/000486546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocis P., Tolar M., Yu J., Sinko W., Ray S., Blennow K., et al. (2017). Elucidating the Aβ42 Anti-Aggregation Mechanism of Action of Tramiprosate in Alzheimer's Disease: Integrating Molecular Analytical Methods, Pharmacokinetic and Clinical Data. CNS Drugs 31 (6), 495–509. 10.1007/s40263-017-0434-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota K., Fukue H., Sato H., Hashimoto K., Fujikane A., Moriyama H., et al. (2017). The traditional Japanese herbal medicine Hachimijiogan elicits neurite outgrowth effects in PC12 cells and improves cognitive in AD model rats via phosphorylation of CREB. Front. Pharmacol. 8, 850. 10.3389/fphar.2017.00850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Singh A., Ekavali (2015). A review on Alzheimer's disease pathophysiology and its management: An update. Pharmacol. Rep. 67 (2), 195–203. 10.1016/j.pharep.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J., Ismail Z., Hatta N. H., Baharuddin N., Hapidin H., Get Bee Y. T., et al. (2018. a). Alcohol Addiction-Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor Subtype 5 and its Ligands: How They All Come Together? Curr. Drug Targets 19 (8), 907–915. 10.2174/1389450118666170511144302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J., Solaiman A., Mahakkanukrauh P., Mohamed R., Das S. (2018. b). Sleep related epilepsy and pharmacotherapy: An insight. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 1–17. 10.3389/fphar.2018.01088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Sánchez J. I., Moreno D. A., García-Viguera C. (2018). D-pinitol, a highly valuable product from carob pods: Health-promoting effects and metabolic pathways of this natural super-food ingredient and its derivatives. AIMS Agric. Food 3 (1), 41–63. 10.3934/agrfood.2018.1.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lalut J., Karila D., Dallemagne P., Rochais C. (2017). Modulating 5-HT4 and 5-HT6 receptors in Alzheimer's disease treatment. Future Med. Chem. 9 (8), 781–795. 10.4155/fmc-2017-0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Jeong S., Kim B., Park K., Dash A. (2015). Donepezil across the spectrum of Alzheimer's disease: dose optimization and clinical relevance. Acta Neurol. Scand. 131 (3), 259–267. 10.1111/ane.12386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D., Lee W. S., Lim S., Kim Y. K., Jung H. Y., Das S., et al. (2017). A guanidine-appended scyllo-inositol derivative AAD-66 enhances brain delivery and ameliorates Alzheimer's phenotypes. Sci. Rep. 7 (14125), 1–9. 10.1038/s41598-017-14559-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Shi H., Zhao Y. (2018). “Phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau by mitogen-activated protein kinase in Alzheimer's disease,” in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 394 (England: IOP Publishing; ), 022023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Wang M. (2018). Carvedilol protection against endogenous Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in N2a cells. Cell Stress Chaperones 23 (4), 695–702. 10.1007/s12192-018-0881-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Logovinsky V., Satlin A., Lai R., Swanson C., Kaplow J., Osswald G., et al. (2016). Safety and tolerability of BAN2401-a clinical study in Alzheimer's disease with a protofibril selective A β antibody. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 8 (14), 1–10. 10.1186/s13195-016-0181-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo I., Ramaswamy G., Fogel I., Mo Y., Friedhoff L., Bruinsma B. (2017. a). A summary of baseline efficacy characteristics from the mindset study: a global phase 3 study of Intepirdine (RVT-101) in subjects with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dementia 13 (7), P936. 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.06.1831 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo I., Ramaswamy G., Friedhoff L., Asare E. (2017. b). Intepirdine (RVT-101), a 5-HT6 receptor antagonist, as an adjunct to Donepezil in mild-to-mModerate Alzheimer's disease: efficacy on activities of daily living domains. Am. J. Geriatric Psychiatry 25 (3), S120–S121. 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.01.139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes J. P. B., Silva L., da Costa Franarin G., Antonio Ceschi M., Seibert Lüdtke D., Ferreira Dantas R., et al. (2018). Design, synthesis, cholinesterase inhibition and molecular modelling study of novel tacrine hybrids with carbohydrate derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 26 (20), 5566–5577. 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez C., Tariot P. N., Caputo A., Langbaum J. B., Liu F., Riviere M., et al. (2019). The Alzheimer ‘s Prevention Initiative Generation Program: Study design of two randomized controlled trials for individuals at risk for clinical onset of Alzheimer ‘s disease. Alzheimer's Dementia: Trans. Res. Clin. Interventions 5 (1), 216–227. 10.1016/j.trci.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchsinger J. A., Perez T., Chang H., Mehta P., Steffener J., Pradabhan G., et al. (2016). Metformin in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: Results of a pilot randomized placebo controlled clinical trial. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 51 (2), 501–514. 10.3233/JAD-150493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo F., Zhang J., Burke K., Miller R. H., Yang Y. (2016). The activators of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 p35 and p39 are essential for oligodendrocyte maturation, process formation, and myelination. J. Neurosci. 36 (10), 3024–3037. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2250-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher-Edwards G., De'Ath J., Barnett C., Lavrov A., Lockhart A. (2015). A 24-week study to evaluate the effect of rilapladib on cognition and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dementia: Trans. Res. Clin. Interventions 1 (2), 131–140. 10.1016/j.trci.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouf R., Collins H. (2018). Tramiprosate (Alzhemed) for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 1–4. 10.1002/14651858.CD007549.pub2.www.cochranelibrary.com [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mancinelli R., Carpino G., Petrungaro S., Mammola C. L., Tomaipitinca L., Filippini A., et al. (2017). Multifaceted roles of GSK-3 in cancer and autophagy-related diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity. 2017, 1–15. 10.1155/2017/4629495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marttinen M., Takalo M., Natunen T., Wittrahm R., Gabbouj S., Kemppainen S., et al. (2018). Molecular Mechanisms of Synaptotoxicity and Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's Disease. Front. Neurosci. 12, 1–9. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters C. L., Bateman R., Blennow K., Rowe C. C., Sperling R. A., Cummings J. L. (2015). Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 1, 1–18. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes A., Palmer S. (2018). Dementia-slowing medication: latest developments. Nurs. Residential Care 20 (9), 442–444. 10.12968/nrec.2018.20.9.442 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minjarez B., Rustarazo M. L. V., Sanchez Del Pino M. M., González-Robles A., Sosa- Melgarejo J. A., Luna-Muñoz J., et al. (2013). Identification of polypeptides in neurofibrillary tangles and total homogenates of brains with Alzheimer's disease by tandem mass spectrometry. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 34 (1), 239–262. 10.3233/JAD-121480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrego P., Lobo A. (2019). A good marker does not mean a good target for clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid hypothesis questioned. Neurodegenerative Dis. Manage. 9 (3), 119–121. 10.2217/nmt-2019-0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsy A., Trippier P. C. (2018). Amyloid-Binding Alcohol Dehydrogenase (ABAD) Inhibitors for the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. J. Med. Chem. 62 (9), 4252–4264. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussa C., Hebron M., Huang X., Ahn J., Rissman R. A., Aisen P. S., et al. (2017). Resveratrol regulates neuro-inflammation and induces adaptive immunity in Alzheimer ‘s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 14 (1), 1–10. 10.1186/s12974-016-0779-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullane K., Williams M. (2018). Alzheimer ‘s disease (AD) therapeutics – 1: Repeated clinical failures continue to question the amyloid hypothesis of AD and the current understanding of AD causality. Biochem. Pharmacol. 158, 359–375. 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullard A. (2018). Microglia-targeted candidates push the Alzheimer drug envelope. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 17 (5), 303–305. 10.1038/nrd.2018.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]