Abstract

Objective.

Although opioid maintenance is a first-line approach for treating opioid use disorder (OUD), suboptimal treatment outcomes have been reported among emerging adults (EAs; 18–25 years of age). In this secondary analysis, we compared treatment outcomes between EAs and older adults (OAs; ≥ 26 years of age) receiving low-barrier, technology-assisted Interim Buprenorphine Treatment (IBT) during waitlist delays to comprehensive opioid maintenance treatment.

Method.

Participants were 35 individuals with OUD who received IBT consisting of 12-weeks of buprenorphine maintenance with bi-monthly clinic visits and technology-assisted monitoring. At monthly follow-up assessments, participants completed staff-observed urinalysis, the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), and Addiction Severity Index (ASI).

Results.

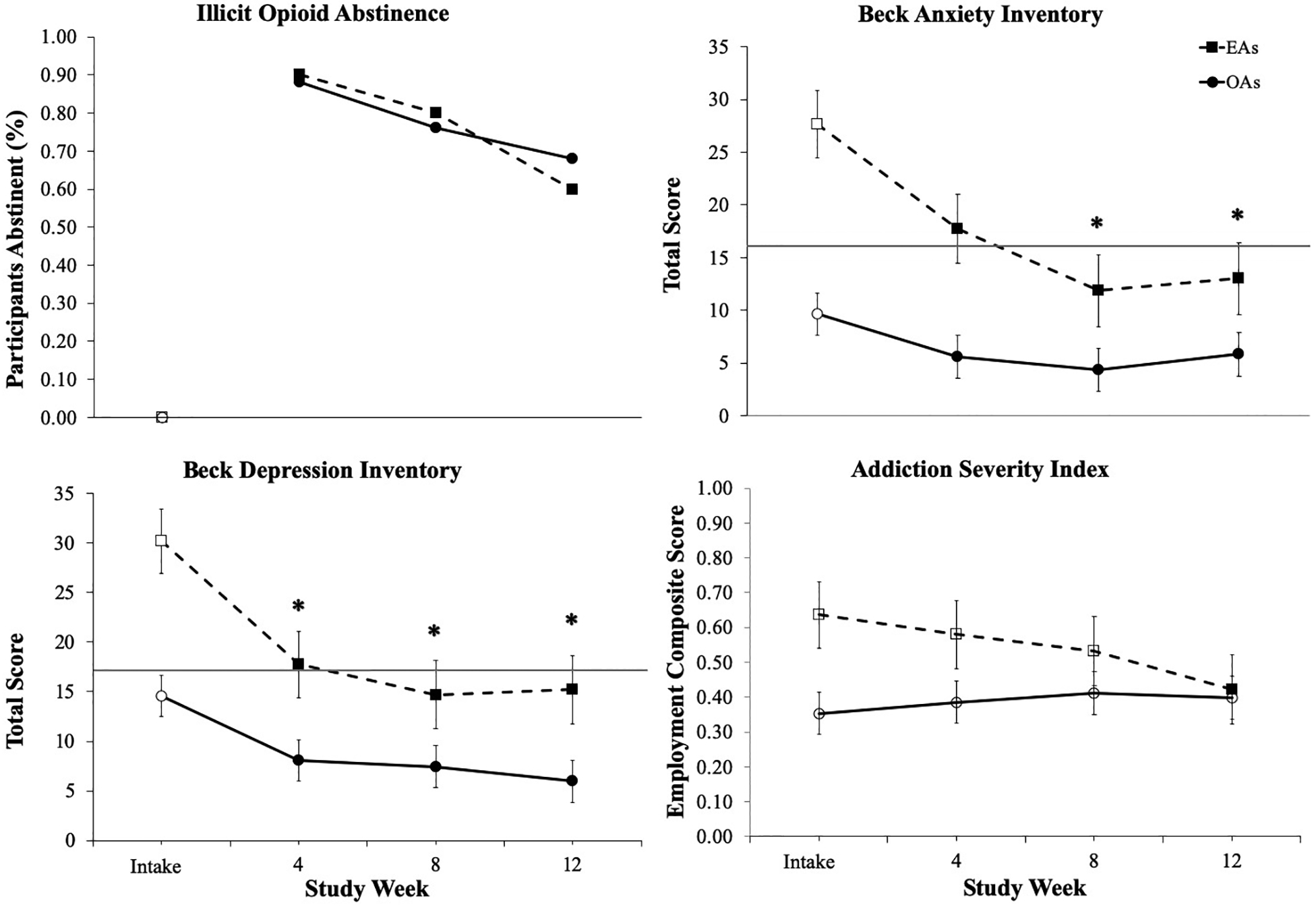

At study intake, EAs (n = 10) reported greater past-year intravenous drug use and greater employment, legal, and psychiatric severity (p’s < .05) compared to OAs (n = 25). Despite these initial differences, there were no significant differences in the percentages of urine specimens testing negative for illicit opioids between EA and OA participants at Study Week 4 (90% vs. 88%, p = .99), Week 8 (80% vs. 76%, p = .99) or Week 12 (60% vs. 68%, p = .71). Relative to their older peers, EAs also demonstrated significantly greater improvements on the BAI, BDI-II, and ASI Employment and Legal subscales (p’s < .05).

Conclusions.

Despite presenting with greater past-year intravenous drug use and psychosocial severity relative to OAs, EAs responded favorably to the IBT intervention.

Keywords: emerging adults, opioid use disorder, buprenorphine, interim treatment

1. Introduction

Opioid misuse continues to exact a staggering toll, with nearly 12 million Americans reporting opioid misuse (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2017). As a result, opioid-related overdoses, emergency department visits, and deaths are highly prevalent in the United States and contribute to economic costs estimated at over $78 billion annually (Florence et al., 2016; Rudd et al., 2016; Geller et al., 2019). Opioid misuse is disproportionately elevated among emerging adults (EAs) aged 18–25 years. Rates of past-year non-medical prescription opioid use, for example, are higher among EAs (7.6%) compared to individuals aged 12–17 (4.8%) and 26–34 (6.0%; Hu et al., 2017). Compared to other age groups, EAs have also experienced steeper increases in heroin use and overdoses (Hedegaard et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2015).

Buprenorphine and methadone maintenance are widely-used, effective approaches for treating opioid use disorder (OUD; Mattick et al., 2014; Gowing et al., 2017). However, younger age has been associated with poorer opioid treatment outcomes (Dreifuss et al., 2013; Marcovitz et al., 2016; Proctor et al., 2015). Although buprenorphine is generally effective for treatment of OUD among EAs (Woody et al., 2008), some recent studies indicate that EAs are more likely than older adults (OAs) to use illicit opioids and drop out of treatment (Schuman-Olivier et al., 2014). Conversely, other studies have found no association between age and buprenorphine treatment outcomes (Gerra et al., 2004; Stein et al., 2005). Although the reasons underlying the potentially poorer treatment response among EAs are not well understood, emerging adulthood is a distinct developmental period associated with increased risk behaviors and substance use (Arnett, 2000; Arnett, 2005; Bachman et al., 1997; Kirst et al., 2014). Given the deleterious consequences associated with opioid misuse among EAs, efforts to understand the treatment needs of this vulnerable group are critical.

We have developed a low-barrier, technology-assisted Interim Buprenorphine Treatment (IBT) regimen for reducing illicit opioid use during waitlist delays for more comprehensive opioid agonist treatment (OAT; Sigmon et al., 2015, 2016). The IBT intervention consists of buprenorphine maintenance without formal counseling. Between bi-monthly dosing visits, medications are administered at-home using technology-assisted dispensing to support compliance and prevent diversion. Individuals who received IBT achieved significant reductions in illicit opioid and intravenous (IV) drug use compared to those who remained waitlisted for treatment (Sigmon et al., 2016).

Low-barrier treatment options such as IBT may hold particular promise for EAs who may be less likely to enter and remain in treatment (Hadland et al., 2017; Marcovitz et al., 2016; Proctor et al., 2015). However, given that young people may fare poorly in outpatient buprenorphine treatment, it is important to understand whether therapeutic response to IBT varies as a function of patient age. Accordingly, this secondary analysis was conducted to examine whether baseline characteristics and treatment response differed among EA (18–25 years of age) and OA (≥ 26 years of age) participants who received the IBT intervention.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were 35 adults with OUD who received IBT in one of two recent studies (Sigmon et al., 2015, 2016). Inclusion criteria were identical for both studies and eligible participants were ≥ 18 years old, met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) criteria for OUD, provided an opioid-positive urine specimen at intake, and were waitlisted for an opioid treatment program in the community. Participants who were pregnant or nursing, individuals who had significant psychiatric or medical conditions that could interfere with consent or participation, and those who were physically dependent on sedative-hypnotics or alcohol were excluded.

2.2. Procedure

The IBT intervention involved buprenorphine maintenance for 12 weeks. At scheduled bi-monthly clinic visits, participants ingested their medication under nurse observation, provided a staff-observed urine sample, and completed questionnaires. Remaining doses for each two-week interval were ingested at home and administered via a computerized medication dispenser (Med-O-Wheel Secure; Addoz, Finland). Participants received daily calls from an automated Interactive Voice Response (IVR) system that assessed opioid use, craving, and withdrawal as well as other illicit drug or alcohol use. The IVR system also contacted participants twice monthly for random call-back visits at which participants returned to the clinic to ingest that day’s dose under nurse observation, complete a pill count, and provide a urine specimen. Participants also completed follow-up assessments (described below) and urinalysis at Study Weeks 4, 8, and 12. Both studies on which these secondary analyses are based were approved by the University of Vermont Institutional Review Board, and participants provided written informed consent prior to participation (Sigmon et al., 2015, 2016).

2.3. Measures

Demographic characteristics and use of opioids and other drugs were assessed using a Drug History Questionnaire and Time-Line Followback interview (Sobell et al., 1988). The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck and Steer, 1993), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996) and the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1992) were administered at study intake and at Study Weeks 4, 8, and 12 to evaluate psychiatric and psychosocial functioning.

2.4. Statistical Methods

EAs (n = 10) and OAs (n = 25) were compared on baseline characteristics using t-tests for continuous measures and chi square or Fisher’s Exact tests for categorical measures. Outcome measures consisted of illicit opioid abstinence and scores on the BAI, BDI-II, and ASI subscales. Urine specimens were submitted at each assessment and missing urine samples were considered opioid-positive. Chi square tests were used to compare EA and OA groups on illicit opioid abstinence at Weeks 4, 8, and 12 and treatment retention at Week 12. Mixed model repeated measures analyses were used to compare temporal changes between EA and OA groups on continuous outcomes assessed at intake, and Weeks 4, 8, and 12. All means derived from mixed model repeated measures analyses are presented as least square means which account for missing data due to incomplete follow-up. Linear contrasts were used to compare time specific changes between and within EA and OA groups. Analyses were conducted SAS Statistical Software, V9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) with statistical significance based on p < .05.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Although baseline demographic characteristics were generally similar between EAs and OAs, a larger percentage of EAs endorsed the IV route as their primary route of opioid administration than OAs (80% vs. 32%, respectively; p = .01; Table 1). The EA group presented with greater psychiatric severity and problems in several areas of psychosocial functioning compared to OAs, including higher baseline scores on the BAI (27.70 vs. 9.64, p < .001) and BDI-II (30.22 vs. 14.57, p < .001). Furthermore, EAs reported greater baseline severity on the ASI Employment (0.64 vs. 0.35, p = .019), Legal (0.33 vs. 0.03, p < .001) and Psychiatric (0.44 vs. 0.22, p = .01) subscales.

Table 1-.

Participant characteristics

| Measure | Emerging Adults (n = 10) | Older Adults (n = 25) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 23.6 (2.1) | 38.5 (8.2) | < .001 |

| Male, N (%) | 6 (60.0) | 14 (56.0) | .99 |

| White, N (%) | 10 (100.0) | 24 (96.0) | .99 |

| Employed full-time, N (%) | 4 (40.0) | 15 (60.0) | .45 |

| Education, years | 11.6 (2.1) | 12.6 (2.0) | .18 |

| Duration of regular opioid use, years | 4.6 (2.6) | 7.7 (6.2) | .14 |

| Past-month opioid use, days | 25.8 (6.0) | 28.4 (3.6) | .12 |

| Ever used IV, N (%) | 8 (80.0) | 16 (64.0) | .45 |

| Ever used heroin, N (%) | 10 (100.0) | 20 (80.0) | .29 |

| Buprenorphine stabilization dose, mg | 10.4 (3.1) | 11.6 (3.6) | .39 |

| Primary route of administration | .01 | ||

| Oral/sublingual, N (%) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (44.0) | |

| Intranasal, N (%) | 2 (20.0) | 6 (24.0) | |

| Intravenous, N (%) | 8 (80.0) | 8 (32.0) | |

| Past year primary opioid of abusea | .06 | ||

| Prescription opioid, N (%) | 2 (20.0) | 15 (60.0) | |

| Buprenorphine, N (%)b | 1 (10.0) | 11 (44.0) | |

| Mean daily dose, mg | 8 | 9.8 (5.1) | |

| Oxycodone, N (%)b | 1 (10.0) | 4 (16.0) | |

| Mean daily dose, mg | 100 | 120 (54.2) | |

| Heroin | 8 (80.0) | 10 (40.0) | |

| Mean daily amount, bags | 18.9 (24.9) | 8.1 (4.8) | |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) | 27.7 (17.7) | 9.6 (11.2) | < .001 |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | 30.2 (13.3) | 14.6 (10.9) | < .001 |

| Addiction Severity Index (ASI)c | |||

| Medical | .49 (.37) | .42 (.39) | .64 |

| Employment | .64 (.32) | .34 (.32) | .02 |

| Alcohol | .02 (.03) | .07 (.11) | .12 |

| Drug | .36 (.06) | .35 (.17) | .94 |

| Legal | .33 (.24) | .04 (.07) | < .001 |

| Family/social | .19 (.22) | .17 (.22) | .77 |

| Psychiatric | .44 (.22) | .22 (.23) | .01 |

Note. Values represent mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. Bold type indicates significant difference between groups.

Between groups comparison of individuals who reported prescription opioids versus heroin as primary opioid of abuse.

The percentage of participants endorsing each opioid prescription subtype are based on the total number of individuals who reported primary prescription opioid use within each group.

ASI composite subscale scores range from 0–1.

3.2. Illicit Opioid Abstinence and Study Retention

The EA and OA groups achieved comparable rates of biochemically-verified illicit opioid abstinence during the IBT intervention, with no significant differences in the percentages of EA and OA participants who provided negative specimens at Weeks 4 (90% vs. 88%, p = .99), 8 (80% vs. 76%, p = .99) or 12 (60% vs. 68%, p = .71)(Figure 1, upper left panel). Retention rates were also similar, with 80% and 88% of EA and OA participants completing the 12-week study, respectively (p = .61; not shown).

Figure 1.

Changes over time in illicit opioid abstinence, Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Addiction Severity Index (ASI) Psychiatric, and Beck Depression Inventory scores for emerging adult (EA) and older adult (OA) participants. The horizontal lines represent the cut-off score for moderate anxiety on the BAI (total score ≥ 16; Beck and Steer, 1993 and the commonly-used cut-off indicating clinically significant depression on the BDI-II (total score ≥ 17; Beck et al., 1996). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Solid symbols indicate a significant within-group change from intake; asterisks indicate that the change from intake to assessment timepoint significantly differed between EA and OA groups (p < .05).

3.3. Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms

Significant group x time interactions on measures of anxiety and depressive symptoms indicated that EAs demonstrated greater decreases in BAI (F(3, 89) = 4.10, p = .006; Figure 1, upper right panel) and BDI-II (F(3, 89) = 3.02, p = .028; lower left panel) scores compared to OAs, respectively. Though both groups reported decreases in symptoms of anxiety and depression at 4-, 8-, and 12-week follow-up assessments relative to intake (p’s < .05), the EA group reported greater reductions than OAs.

3.4. Addiction Severity Index

Significant group x time interactions were observed for the ASI Employment (F(3, 85) = 4.33, p = .007), Legal (F(3, 89) = 4.13, p = .009) and Alcohol (F(3, 89) = 2.76, p = .047) subscales (Supplemental Table). Generally, EAs reported improvements over time in these problem areas; whereas, OAs reported no change. Scores on the Employment subscale are presented in Figure 1 (lower right panel) as a representative example.

Both EA and OA groups demonstrated significant improvements over time on the ASI Medical, Drug, and Psychiatric subscales, (p’s < .01 for main effects of time), with no differences in these changes between groups (Supplemental Table). However, EAs reported baseline scores on the Psychiatric subscale that were significantly higher than OAs and remained higher at 4-,8- and 12-week follow-ups (p’s < .05). Finally, there were no significant group differences or changes over time on the ASI Family/Social subscale (p’s > .05).

4. Discussion

As young adults experience increases in opioid misuse and related morbidity and mortality, ongoing efforts to better understand the potentially-unique treatment needs of this vulnerable group are critical. In the present study, EAs presented for treatment with a higher prevalence of IV opioid use and more severe employment, legal and psychiatric problems than OAs. These findings are consistent with national-level data that show that IV opioid use is most prevalent among young adults (SAMHSA, 2014), as well as existing literature that conceptualizes emerging adulthood as a critical period for onset and exacerbation of substance abuse and mental health issues more generally (Arnett, 2005; Kirst et al., 2014). Although OAs reported psychiatric and psychosocial problems that were comparable to community norms, mean scores on measures of psychiatric and psychosocial problems for EAs were substantially greater than normative values reported by healthy adults and college students as well as patients receiving substance use treatment (Denis et al., 2013; Gillis et al., 1995; Nuevo et al., 2009; Whisman and Richardson, 2015).

Despite greater past-year intravenous drug use and drug-related psychosocial consequences, EAs demonstrated positive therapeutic response to IBT, including high rates of illicit opioid abstinence, favorable study retention and significant improvements in multiple areas of psychosocial functioning. These data stand in contrast to some recent findings showing poorer treatment outcomes among younger patients (Marcovitz et al., 2016; Schuman-Olivier et al., 2014) and supports prior studies that found no effect of age on buprenorphine treatment dropout or illicit opioid use during OAT (Gerra et al., 2004; Stein et al., 2005). Despite the promising nature of these data, the present findings are limited by the small racially homogenous study sample and relatively brief treatment duration of the parent studies. In order to address these limitations, a larger-scale, longer-duration randomized clinical trial is currently underway. Future research should also examine the effects of low-barrier buprenorphine treatment for OUD among more diverse samples of EAs.

The EA group also experienced significant improvements in psychiatric and psychosocial functioning during IBT treatment such that these individuals reported fewer employment, legal and psychiatric problems at the end of the 12-week study relative to baseline. Similar improvements have been consistently demonstrated following entry into other forms of OAT (Dean et al., 2004; Fingleton et al., 2015). However, unlike previous treatments, the IBT intervention did not include any formal psychosocial counseling. Additional studies with larger samples should seek to replicate these initial promising findings with low-barrier treatment that capitalizes on EAs pervasive use of technology. It also should be noted that EAs presented with more severe psychiatric symptoms at study intake and thus had greater opportunities for improvement compared to OAs. Further, EAs still had higher scores on the BDI-II and ASI Legal and Psychiatric subscales at the end of the 12-week study relative to OAs, suggesting that additional support may be warranted to help some EAs achieve even better psychosocial outcomes.

In summary, despite presenting with greater past-year intravenous drug use and psychosocial severity relative to OAs, EAs receiving low-barrier buprenorphine treatment achieved dramatic improvements in illicit opioid use and psychological and psychosocial problems. These findings suggest that low-burden interventions such as IBT may hold promise for reducing opioid-related morbidity and mortality among EAs, though further investigation with larger samples and longer treatment durations is indicated.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Opioid misuse is disproportionately elevated among 18–25 year old emerging adults.

Emerging adults may also have worse opioid treatment response than older adults.

We compared emerging and older adults on Interim Buprenorphine Treatment outcomes.

Emerging adults presented with more past-year IV drug use relative to older adults.

Emerging adults exhibited a favorable response to interim buprenorphine treatment.

Low-barrier buprenorphine treatment may hold promise for emerging adults.

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA042790, R34DA037385), the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM103644-07).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Clinical Trial Number: NCT02360007

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this report were entirely responsible for the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, the preparation of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the work for publication. KRP, TAO, GJB, and SCS have no interests that may be perceived as conflicting with the research.

References

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, 2000. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through early twenties. Am. Psychol 55, 469–480. https://doi:10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, 2005. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. J. Drug Issues 35, 235–254. doi: https://doi:10.1177/002204260503500202 [Google Scholar]

- Bachman J, Wadsworth K, O’Malley P, Johnston L, Schulenberg J, 1997. Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: the impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, 1993. Beck Anxiety Inventory manual. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK, 1996. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Dean AJ, Bell J, Christie MJ, & Mattick RP, 2004. Depressive symptoms during buprenorphine vs. methadone maintenance: findings from a randomised, controlled trial in opioid dependence. Eur. Psychiatry 19, 510–513. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis CM, Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, 2013. Addiction Severity Index (ASI) summary scores: comparison of the recent status scores of the ASI-6 and the composite scores of the ASI-5. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 45, 444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreifuss JA, Griffin ML, Frost K, Fitzmaurice GM, Potter JS, Fielllin DA, Selzer J, Hatch-Maillette M, Sonne SC, Weiss RD, 2013. Patient characteristics associated with buprenorphine/naloxone treatment outcome for prescription opioid dependence: results from a multisite study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 131, 112–118. https://doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingleton N, Matheson C, Jaffray M, 2015. Changes in mental health during opiate replacement therapy: a systematic review. Drugs (Abingdon Engl). 22, 1–18. 10.3109/09687637.2014.899986 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Florence CS, Zhou C, Luo F, Xu L, 2016. The economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence in the United States, 2013. Med. Care 54, 901–906. https://doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller AI, Dowell D, Lovegrove MC, McAninch JK, Goring SK, Rose KO, Weidle NJ, Budnitz DS, 2019. U.S. emergency department visits resulting from nonmedical use of pharmaceuticals, 2016. Am. J. Prev. Med 56, 639–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerra G, Borella F, Zaimovic A, Moi G, Bussandri M, Bubici C, Bertacca S, 2004. Buprenorphine versus methadone for opioid dependence: predictor variables for treatment outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 75, 37–45. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis MM, Haaga DAF, Ford GT, 1995. Normative values for the Beck Anxiety Inventory, Fear Questionnaire, Penn State Worry Questionnaire, and Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory. Psychol. Assess 7, 450–455. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.450 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gowing L, Ali R, White J, Mbewe D, 2017. Buprenorphine for managing opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 2 https://doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002025.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadland SE, Wharam JF, Schuster MA, Zhang F, Samet JH, Larochelle MR, 2017. Trends in receipt of buprenorphine and naltrexone for opioid use disorder among adolescents and young adults, 2001–2014. JAMA Pediatr. 171, 747–755. https://doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, Chen L, Warner M, 2015. Drug-poisoning deaths involving heroin: United States, 2000–2013. NCHS Data Brief 190, 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M-C, Griesler P, Wall M, Kandel DB, 2017. Age-related patterns in non-medical prescription opioid use and disorder in the US population at ages 13–34 from 2002 to 2014. Drug Alcohol Depend. 177, 237–243. https://doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Logan J, Gladden M, Bohm MK, 2015. Vital signs: demographic and substance use trends among heroin users – United States, 2002–2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 64, 719–725. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirst M, Mecredy G, Borland T, Chaiton M, 2014. Predictors of substance use among young adults transitioning away from high school: a narrative review. Subst. Use Misuse 49, 1795–1807. https://doi:10.3109/10826084.2014.933240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcovitz DE, McHugh RK, Volpe J, Votaw V, Connery HS, 2016. Predictors of early dropout in outpatient buprenorphine/naloxone treatment. Am. J. Addict 25, 472–477. https://doi:10.1111/ajad.12414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M, 2014. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence (review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 2 https://doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M, 1992. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst. Abuse Treat. 9, 199–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuevo R, Lehtinen V, Reyna-Liberato PM, Ayuso-Mateos JL, 2009. Usefulness of the Beck Depression Inventory as a screening method for depression among the general population of Finland. Scand. J. Public Health 37, 28–34. doi: 10.1177/1403494808097169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor SL, Copeland AL, Kopak AM, Hoffmann NG, Herschman PL, Polukhina N, 2015. Predictors of patient retention in methadone maintenance treatment. Psychol. Addict. Behav 29, 906–917. https://doi:10.1037/adb0000090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM, 2016. Increases in drug use and opioid overdose deaths – United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 64, 1378–1382. https://doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman-Olivier Z, Weiss RD, Hoeppner BB, Borodovsky J Albanese MJ, 2014. Emerging adult age status predicts poor buprenorphine treatment retention. J Subst. Abuse Treat 47, 202–212. https://doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmon SC, Meyer AC, Hruska B, Ochalek T, Rose G, Badger GJ, Brooklyn JR, Heil SH, Higgins ST, Moore BA, Schwartz RP, 2015. Bridging waitlist delays with interim buprenorphine treatment: initial feasibility. Addict. Behav 51, 136–142. https://doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmon SC, Ochalek TA, Meyer AC, Hruska B, Heil SH, Badger GJ, Rose G, Brooklyn JR, Schwartz JR, Moore BA, Higgins ST, 2016. Interim buprenorphine vs. waiting list for opioid dependence. N. Engl. J. Med 375, 2504–2505. https://doi:10.1056/NEJMc1610047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A, 1988. Reliability of a timeline method: assessing normal drinkers’ reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. Br. J. Addict 83, 393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD, Cioe P, & Friedmann PD 2005. Buprenorphine retention in primary care. J Gen Intern Med, 20, 1038–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0228.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2002–2012 National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services, Rockville, MD: (BHSIS Series S-71, HHS Publication No. SMA 14–4850; ). [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Rockville, MD: (HHS Publication No. SMA 17–5044, NSDUH Series H-52). [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Richardson ED, 2015. Normative data on the Beck Depression Inventory – Second Edition (BDI-II) in college students. J. Clin. Psychol 71, 898–907. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody GE, Poole SA, Subramaniam G, Dugosh K, Bogenschutz M, Abbott P, Patkar A, Publicker M, McCain K, Potter JS, Forman R, Vetter V, McNicholas L, Blaine J, Lynch KG, Fudala P, 2008. Extended vs short-term buprenorphine-naloxone for treatment of opioid-addicted youth. JAMA 300, 2003–2011. https://doi:10.1001/jama.2008.574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.