Abstract

Macrophages have been linked to tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and treatment resistance. However, the transcriptional regulation of macrophages driving the protumor function remains elusive. Here, we demonstrate that the transcription factor c-Maf is a critical controller for immunosuppressive macrophage polarization and function in cancer. c-Maf controls many M2-related genes and has direct binding sites within a conserved noncoding sequence of the Csf-1r gene and promotes M2-like macrophage–mediated T cell suppression and tumor progression. c-Maf also serves as a metabolic checkpoint regulating the TCA cycle and UDP-GlcNAc biosynthesis, thus promoting M2-like macrophage polarization and activation. Additionally, c-Maf is highly expressed in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and regulates TAM immunosuppressive function. Deletion of c-Maf specifically in myeloid cells results in reduced tumor burden with enhanced antitumor T cell immunity. Inhibition of c-Maf partly overcomes resistance to anti–PD-1 therapy in a subcutaneous LLC tumor model. Similarly, c-Maf is expressed in human M2 and tumor-infiltrating macrophages/monocytes as well as circulating monocytes of human non–small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) patients and critically regulates their immunosuppressive activity. The natural compound β-glucan downregulates c-Maf expression on macrophages, leading to enhanced antitumor immunity in mice. These findings establish a paradigm for immunosuppressive macrophage polarization and transcriptional regulation by c-Maf and suggest that c-Maf is a potential target for effective tumor immunotherapy.

Keywords: Immunology

Keywords: Cancer, Immunotherapy, Macrophages

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, accounting for approximate 2.1 million new cases and 1.7 million deaths annually (1). Although cancer immunotherapy has been proclaimed a breakthrough, a significant proportion of cancer patients do not show clinical benefit. In patients with advanced non–small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), therapies with immunocheckpoint inhibitor anti–program death 1 (anti–PD-1) demonstrated response rates of 17% to 21% (2, 3). Previous studies have shown that lung cancer cell–intrinsic effects such as the mutational load determines responsiveness to PD-1 blockade therapy (4). In addition, many cancer cell–extrinsic factors contribute to this resistance (5). The tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) consists of many suppressive immune cells such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), thus establishing a local immunosuppressive environment that dampens T cell effector function (6, 7). Macrophages are the major tumor-infiltrating leukocytes in nearly all cancers and play a critical role in cancer-related inflammation, immunosuppression, and treatment resistance (8–12). There is growing interest in developing novel strategies to overcome/reprogram immunosuppressive macrophage function for effective cancer immunotherapy (13, 14).

Macrophages can undergo polarized activation depending on the different environmental cues. Although binary M1/M2 macrophages may not accurately describe the complexity and heterogeneity of macrophages associated with tumor growth and progression, it is clear that most cancers are populated by M2-like macrophages with potent effector T cell inhibitory activity (15). In addition, there is a strong association between poor survival and increased macrophage infiltration within the TIME of human NSCLC patients (16, 17). Previous studies have shown that transcription factors interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5), IRF8, and Notch-Rbpj have been linked to M1-like macrophage polarization (18–20). In contrast, IRF-4, STAT6, c-Myc, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) are involved in M2-like macrophage polarization (21–23). Transcriptome-based network analysis has also identified several transcription regulators associated with macrophage polarization under different stimulation conditions (24). However, controversial data exist regarding these transcription factors, particularly the differences between mice and humans. In addition, it remains to be determined whether transcription factors for M2-like macrophage polarization are also essential for immunosuppressive TAM differentiation because TAMs are usually heterogeneous populations.

c-Maf is a member of the basic leucine zipper transcription factors belonging to the AP-1 family (25). It has been shown that c-Maf is overexpressed in multiple myeloma, enhancing tumor-stroma interactions (26). c-Maf is also expressed in T cells including Th2, Th17, and innate IL-17–producing γδ T cells (27–29). In the monocyte/macrophage lineage, c-Maf has been shown to be essential for macrophage self-renewal (30). In addition, c-Maf promotes IL-10 production while it inhibits IL-12 in macrophages (31, 32). Thus, c-Maf expression in macrophages is thought to drive antiinflammatory responses. On the other hand, c-Maf has been shown to be highly expressed in colonic CD169+ macrophages and is essential for the expression of acute inflammatory genes such as CCL8 (33). Therefore, it is unclear how c-Maf regulates macrophage polarization and function. In addition, it is unknown whether c-Maf is expressed in immunosuppressive TAMs and regulates antitumor immunity. In the current study, we demonstrate that the transcription factor c-Maf is a crucial molecular checkpoint that controls immune suppression in cancer through regulating macrophage metabolic reprogramming and effector function.

Results

Transcription factor c-Maf is highly expressed in M2-like macrophages and controls many M2-related genes.

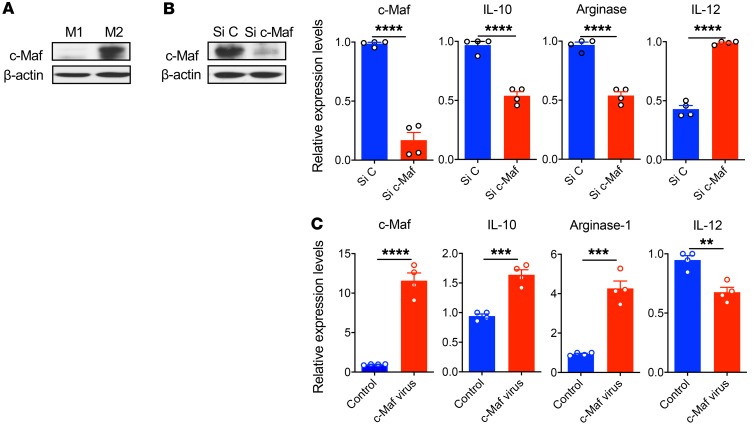

In our previous microarray analysis, we found that c-Maf was associated with M2/M1 macrophage conversion (34). We found that c-Maf was highly expressed in polarized M2-like bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) but not in M1 BMDMs (Figure 1A). This was regardless of different polarization protocols (data not shown). To investigate c-Maf–controlled gene expression, M2-like BMDMs were transfected with c-Maf or control siRNA. Knockdown of c-Maf significantly decreased c-Maf protein and mRNA expression levels (Figure 1B). In addition, Il10 and Arg1 mRNA levels were significantly decreased, while Il12 was increased (Figure 1B). In contrast, ectopic expression of c-Maf in the M1-like BMDMs significantly upregulated Il10 and Arg1 mRNA expression levels, whereas it downregulated Il12 expression (Figure 1C), suggesting an M2-like phenotype. These data indicate that c-Maf may be a critical controller in regulating M2-related gene expression.

Figure 1. c-Maf is predominantly expressed in M2 BMDMs.

(A) c-Maf expression in mouse M1 or M2 BMDMs assessed by WB. (B) M2 BMDMs were transfected with control (Si C) or c-Maf siRNA (Si c-Maf). c-Maf protein and mRNA expression was determined by WB and qPCR. The mRNA expression levels of Il10, Arg1, and Il12 were also determined by qPCR. (C) M1 BMDMs were infected with control or c-Maf lentivirus at a final concentration of 10 MOI. The mRNA expression levels of c-Maf, Il10, Arg1, and Il12 were determined by qPCR. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. The data are representative of at least 2 independent experiments with similar results. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001 by 2-tailed, unpaired t test.

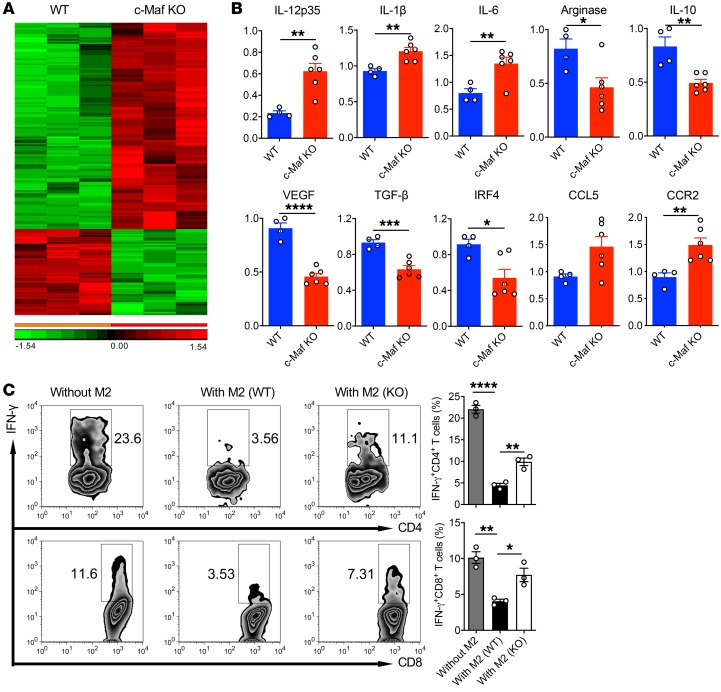

To further determine which part of the M2 macrophage transcriptomic profile is controlled by c-Maf, we performed microarray analysis using polarized M2-like BMDMs from WT or c-Maf–knockout (c-Maf–KO) fetal liver–chimeric mice. Notably, many M2 genes were differentially regulated by c-Maf (Figure 2A). Further quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis confirmed that the mRNA expression levels of Il12, Il1b, Il6, Arg1, Il10, Vegf, Tgfb, Irf4, and Ccr2 were significantly altered in c-Maf–deficient M2 BMDMs (Figure 2B). Because M2-like macrophages have a potent immunosuppressive effect on T cell activation, we next determined whether deficiency of c-Maf in M2 BMDMs would reverse this effect. As shown in Figure 2C, M2 BMDMs from WT mice exhibited potent immunosuppressive activity, as IFN-γ production from antigen-specific (Ag-specific) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was significantly diminished. In contrast, c-Maf deficiency in M2 BMDMs significantly increased IFN-γ production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells compared with WT M2 BMDMs. These data suggest that c-Maf not only controls the expression of many M2-related genes but also is critical in regulating M2-like macrophage–mediated T cell immunosuppression.

Figure 2. c-Maf is an essential controller for M2 marker gene expression and function.

(A) RNA microarray analysis of polarized M2 BMDMs from c-Maf WT and KO chimeric mice (n = 3). Heatmap shows differentially expressed genes. (B) The mRNA expression levels of indicated genes were validated by qPCR analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by 2-tailed, unpaired t test. (C) Polarized M2 BMDMs from WT or c-Maf–KO chimeric mice were cocultured with splenocytes from OT-1 or OT-II mice in the presence of OVA. IFN-γ–producing T cells were analyzed. Representative dot plots and summarized data are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001 by 1-way ANOVA with post hoc t test and Bonferroni’s correction.

c-Maf directly regulates the Csf-1r locus in M2 BMDMs and subsequent immunosuppressive function.

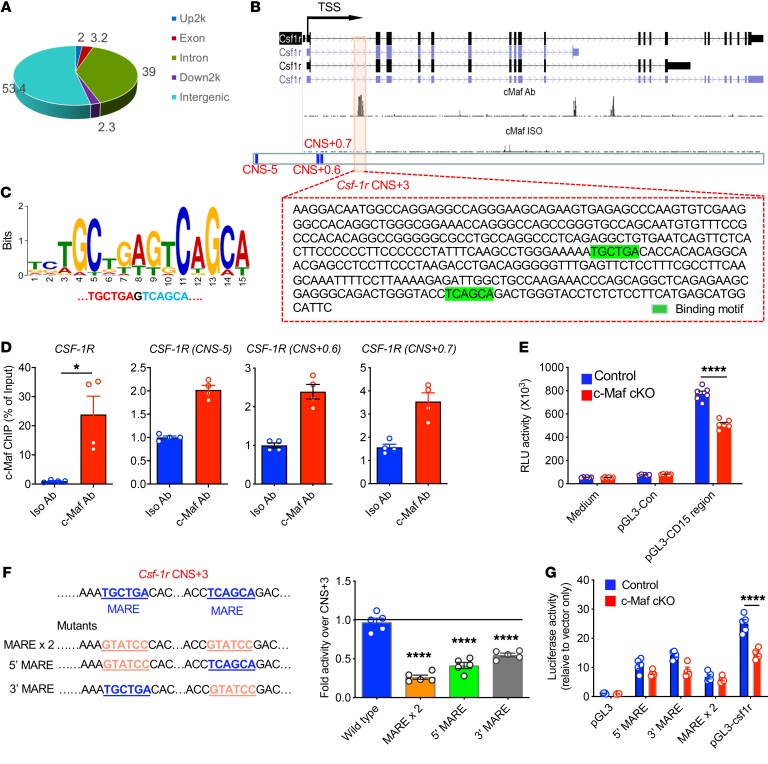

To identify genes directly regulated by c-Maf in M2-like macrophages, c-Maf chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) was performed. Notably, most of the c-Maf binding sites were located in introns or intergenic regions (Figure 3A), suggesting that c-Maf may regulate gene expression through binding to distant regulatory elements. We found that c-Maf had direct binding sites within a conserved noncoding sequence (CNS) located 3 kb downstream from the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (Csf-1r) transcription start site (TSS) (CNS + 3) (Figure 3B). A de novo c-Maf binding motif was discovered (Figure 3C) and further motif analysis identified 2 c-Maf recognition elements (MAREs) in the Csf-1r CNS + 3 region (Figure 3B). Consistent with ChIP-seq data, ChIP-qPCR analysis revealed that c-Maf bound predominately CNS + 3 and to a lesser degree at CNS-5, CNS + 0.6, and CNS + 0.7 as controls in in vitro M-CSF–polarized M2 BMDMs (Figure 3D). These data suggest that c-Maf may occupy distinct cis regions in the Csf-1r locus in M2 BMDMs. To test whether CNS + 3 functions as a c-Maf–dependent Csf-1r promoter in M2 BMDMs, we cloned Csf-1r CNS + 3 driving a luciferase reporter and assayed activity in M2 BMDMs from control and c-Maf conditional KO (c-Maf–cKO) mice. The Csf-1r CNS + 3 induced a 10-fold increase in activity over that of control plasmid that was significantly attenuated in c-Maf–cKO M2 BMDMs (Figure 3E). Further, reporter mutations of the MAREs significantly diminished c-Maf’s activity (Figure 3F), implicating this binding region as a c-Maf–dependent promoter for Csf-1r expression. In addition, WT but not reporter mutations of the MAREs showed differences in c-Maf control and cKO macrophages (Figure 3G). Thus, c-Maf is required for establishing an active regulatory status at the Csf-1r locus in M2 BMDMs.

Figure 3. c-Maf binds a Csf-1r conserved noncoding region and controls its expression in M2 BMDMs.

(A) In vitro–polarized M2 BMDMs were used for ChIP-seq study. The genomic distribution (%) of the identified c-Maf binding sites is shown in a pie chart. Up2k, 2000-bp sequence upstream of the Csf-1r locus; Down2k, 2000-bp sequence downstream of the Csf-1r locus. (B) Quantitative correlation of c-Maf at the Csf-1r locus. Motif analysis indicates that c-Maf has 2 binding sites (highlighted in green) in the Csf-1r conserved noncoding sequence (CNS + 3). (C) De novo–derived c-Maf chromatin binding motif. (D) Chromatin from M2 BMDMs precipitated with c-Maf Ab or isotype control Ab was analyzed by ChIP-qPCR for Csf-1r CNS + 3. Primers for Csf-1r nonbinding regions CNS-5, CNS + 0.6, and CNS + 0.7 were used as negative controls. Percentage of input was calculated using corresponding input as baseline. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 by 2-tailed, unpaired t test. (E) Luciferase reporter assay of promoter activity for Csf-1r CNS + 3 in M2 BMDMs from c-Maf control and cKO mice (n = 6). ****P < 0.0001 by 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple-comparisons test. (F) Luciferase reporter assay of promoter activity for Csf-1r CNS + 3 and mutated MAREs in M2 BMDMs. Mutations in sequences are underlined. ****P < 0.0001 by 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparisons test. (G) Luciferase reporter assay of promoter activity for Csf-1r CNS + 3 and mutated MAREs in M2 BMDMs from c-Maf control (n = 5) and cKO mice (n = 4). ****P < 0.0001 by 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple-comparisons test.

To further confirm that CSF-1R (CD115) expression was regulated by c-Maf, we treated M2 BMDMs with a c-Maf inhibitor or vehicle control. Nivalenol, a small-molecule inhibitor of c-Maf, reduced c-Maf expression assessed by flow cytometry (Supplemental Figure 1A; supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI131335DS1). CSF-1R (CD115) expression was almost completely abrogated on M2 BMDMs when c-Maf expression was inhibited. CSF-1R expression on macrophages has been shown to induce immunosuppression (35). Inhibition of CSF-1R by antibody or small-molecule inhibitors reduce tumor growth in murine tumor models (36, 37). Indeed, in vitro inhibition of c-Maf with a small-molecule inhibitor significantly diminished M2 BMM T cell–suppressive activity, as revealed by increased IFN-γ–producing Ag-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Supplemental Figure 1B). Taken together, these data suggest that c-Maf regulates M2-like macrophage gene expression and immunosuppressive activity, at least in part through control of CSF-1R expression.

c-Maf serves as a metabolic switch for M2-like macrophage polarization and activation.

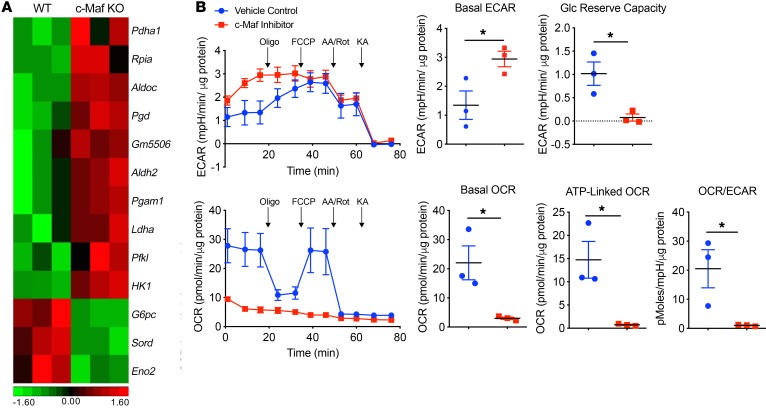

Macrophage activation and function are controlled by cellular metabolism (38). Previous studies have shown that M1-like macrophages predominately use aerobic glycolysis as an energy source (39). Interestingly, several key enzyme genes that are related to glycolysis were significantly upregulated in c-Maf–deficient M2 BMDMs, including hexokinase 1 (HK1), aldehyde dehydrogenase family 2 (Aldh2), and lactate dehydrogenase A (Ldha) (Figure 4A). To further examine whether c-Maf regulates the M2-like macrophage metabolic pathways, we measured the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) using Seahorse assay, which quantifies proton production as a surrogate for lactate production, and thus reflects overall glycolytic flux, and the oxygen consumption rate (OCR), a measure of mitochondrial respiration. Inhibition of c-Maf in M2 BMDMs significantly increased the basal ECAR level and decreased glycolytic reserve capacity while decreasing the basal OCR and ATP-linked OCR, resulting in an overall significantly decreased OCR/ECAR ratio (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Inhibition of c-Maf promotes glycolysis pathway in M2 BMDMs.

(A) Heatmap of glycolysis-related gene expression in the M2 BMDMs from c-Maf WT and KO chimeric mice (n = 3). (B) M2 BMDMs were treated with c-Maf inhibitor (100 ng/mL) or vehicle control for 24 hours and then collected and seeded in a Seahorse XF24 analyzer. Real-time ECAR and OCR were determined during sequential treatments with oligomycin (oligo), FCCP, antimycin A and rotenone (AA/Rot), and koningic acid (KA). Basal levels of ECAR and OCR were measured and the OCR/ECAR ratios are shown. Glycolytic reserve capacity and the ATP-linked OCR were calculated. Each symbol represents 1 independent experiment with 5 wells per group in each experiment. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 by 2-tailed, unpaired t test. mpH, milli-pH units.

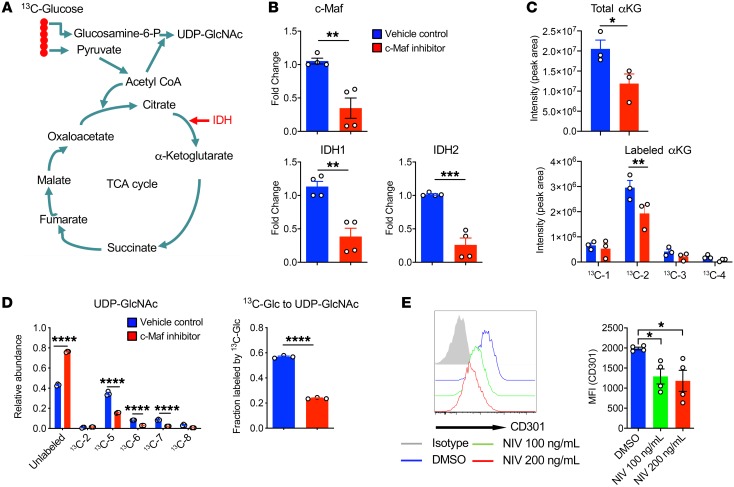

Previous studies have shown that M1 macrophages have 2 breaks in the Krebs cycle (40). One metabolic break that occurred in M1 is at isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH), the enzyme that converts citrate to α-ketoglutarate (αKG) (Figure 5A). Inhibition of c-Maf in M2 BMDMs significantly decreased the mRNA expression levels of Idh1 and Idh2 (Figure 5B). To further determine which metabolic pathway is regulated by c-Maf, we employed the stable isotope–resolved metabolomics (SIRM) approach by using 13C-labeled glucose as a tracer, followed by mass spectrometry (MS) analysis (Figure 5C). M2 BMDMs treated with vehicle control or c-Maf inhibitor were labeled with 13C-glucose to trace the fate of 13C-labeled carbons. Carbon flow from (iso)citrate to αKG was detected in both conditions. Of note, reduced overall αKG abundance and partial labeled forms (13C-2) in the αKG pool present in c-Maf inhibitor–treated M2 BMDMs (Figure 5C) suggest partially interrupted TCA cycle activity.

Figure 5. Inhibition of c-Maf in M2 BMDMs partially interrupts TCA cycle and UDP-GlcNAc activity.

(A) Schema of TCA cycle and UDP-GlcNAc pathway. (B) M2 BMDMs were treated with c-Maf inhibitor or vehicle control and the mRNA levels of c-Maf, IDH1, and IDH2 are shown. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by 2-tailed, unpaired t test. (C) M2 BMDMs (n = 3) treated with vehicle or c-Maf inhibitor were labeled with 13C-labeled glucose for 24 hours. Cell extracts were analyzed by mass spectrometry. The data show that the abundance of total αKG and carbon labeling is reduced in M2 BMDMs treated with c-Maf inhibitor. *P < 0.05 by 2-tailed, unpaired t test (top); **P < 0.01 by 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple-comparisons test (bottom). (D) Inhibition of c-Maf significantly decreases UDP-GlcNAc labeling from 13C-glucose. ****P < 0.0001 by 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple-comparisons test (left) or by 2-tailed, unpaired t test (right). (E) CD301 expression on M2 BMDMs treated with vehicle or the c-Maf inhibitor Nivalenol (NIV) for 24 hours determined by flow cytometry. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 by 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparisons test.

We also found glucose as the major source of carbon in uridine diphosphate–N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc), an important intermediate that links signaling to metabolism (Figure 5, A and D). Previous studies have shown the critical role of the N-glycan pathway in M2 macrophages (41). Inhibition of c-Maf significantly reduced UDP-GlcNAc labeling (Figure 5D), indicative of decreased N-glycosylation in macrophages. To functionally validate this finding, we examined the expression of CD301 (CLEC10A), a macrophage lectin specific for galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) and canonical M2 activation marker. Inhibition of c-Maf significantly downregulated CD301 expression on macrophages (Figure 5E), consistent with SIRM profiling results (Figure 5D). Taken together, these data suggest that c-Maf may control a metabolic switch from glycolysis to mitochondrial oxidation in M2-like macrophages as well as the UDP-GlcNAc biosynthesis pathway.

c-Maf is highly expressed in immunosuppressive TAMs and is critical in TAM-mediated T cell suppression and tumor promotion.

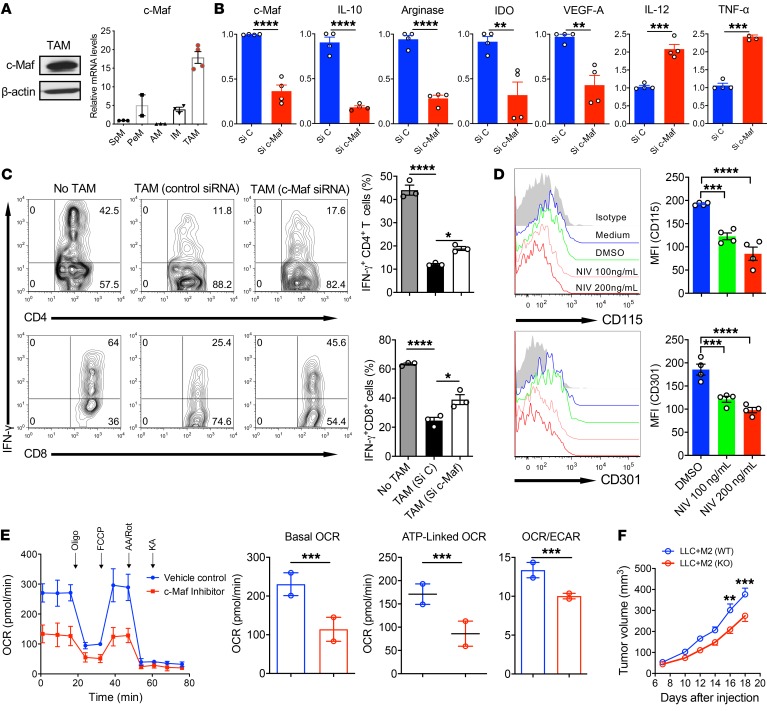

We next determined c-Maf expression in TAMs. TAMs were sorted from subcutaneous (s.c.) LLC tumors and were CD11b+Gr-1–F4/80+MHCIIlo. As TAMs are of the M2-like phenotype, particularly in the late stage of tumor progression, it was not surprising that c-Maf was highly expressed in TAMs (Figure 6A). Compared with macrophages from different tissues of naive mice including the peritoneal cavity, spleen, and lung (alveolar and interstitial macrophages), TAMs expressed the highest c-Maf mRNA level (Figure 6A). c-Maf was not obviously expressed in myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) from the spleen and tumors (data not shown). Knockdown of c-Maf significantly decreased the mRNA expression levels of Il10, Arg1, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (Ido), and Vegfa, while Il12 and Tnfa mRNA expression levels were increased (Figure 6B). Because TAMs have a potent immunosuppressive effect on T cell activation, we next determined whether knockdown of c-Maf would reverse this effect. TAMs with control siRNA exhibited potent immunosuppressive activity, as IFN-γ production from CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was significantly decreased (Figure 6C). TAMs with c-Maf knockdown significantly increased IFN-γ production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Inhibition of c-Maf on TAMs also significantly downregulated CSF-1R (CD115) and CD301 expression (Figure 6D). In addition, inhibition of c-Maf in TAMs significantly decreased basal and ATP-linked OCRs and the overall OCR/ECAR ratio was also significantly decreased (Figure 6E), indicating similar metabolic reprograming controlled by c-Maf in immunosuppressive TAMs. Finally, we investigated whether c-Maf deficiency in the M2-like macrophages decreases their tumor-promoting activity. Tumor cells coinjected with c-Maf–KO M2 BMDMs had significantly delayed progression compared with those injected with WT M2 BMDMs (Figure 6F). Taken together, these data suggest that c-Maf is highly expressed in TAMs and is critical in controlling TAM-induced effector T cell suppression and subsequent tumor promotion.

Figure 6. c-Maf is highly expressed in TAMs and knockdown or deficiency of c-Maf reduces TAM immunosuppressive function and tumor-promoting activity.

(A) c-Maf expression in TAMs was determined by WB (left). Macrophages from different tissues of naive mice and TAMs were assayed for c-Maf mRNA expression by qPCR analysis (right). SpM, Splenic macrophages; PeM, Peritoneal macrophages; AM, alveolar macrophages; IM, Interstitial macrophages. (B) TAMs transfected with c-Maf siRNA (Si c-Maf) or control siRNA (Si C) were assayed for the specific gene mRNA expression. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by 2-tailed, unpaired t test. (C) c-Maf– or control siRNA–transfected TAMs were cocultured with splenocytes from OVA-Tg OT-I or OT-II mice in the presence of OVA. IFN-γ–producing T cells were analyzed. Cells were gated on CD4+ or CD8+ cells. Representative dot plots and summarized data are shown (n = 3). *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001 by 1-way ANOVA with post hoc t test and Bonferroni’s correction. (D) TAMs were treated with the c-Maf inhibitor Nivalenol (NIV) or vehicle control for 24 hours and the expression of CD115 and CD301 was determined by flow cytometry. Representative histograms and summarized data are shown. ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001 by 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparisons test. (E) TAMs were treated with c-Maf inhibitor (100 ng/mL) or vehicle control for 24 hours and then collected and seeded in a Seahorse XF24 analyzer. Real-time OCR, basal and ATP-linked OCR, as well as the OCR/ECAR ratio were determined as described above. Each symbol represents 1 independent experiment with 5 replicates per group in each experiment. Data shown are combined from 2 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 by 2-tailed, unpaired t test. (F) LLC cells mixed with M2 BMDMs from WT or c-Maf–KO chimeric mice in Matrigel were injected into mice (n = 8) and tumor progression was monitored. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple-comparisons test.

Deletion of c-Maf in myeloid cells suppresses tumor growth with enhanced antitumor immunity.

Because global deletion of c-Maf in mice is embryonic lethal (42), we generated c-Maf–floxed (c-Maffl/fl) mice using CRISPR/Cas9 technology and then bred with LysM-cre mice to specifically delete c-Maf from myeloid cells. The protein expression level of c-Maf was significantly reduced in M2 BMDMs from LysM-cre c-Maffl/fl mice compared with control c-Maffl/fl mice, as determined by Western blot (WB) (Supplemental Figure 2A) and flow cytometry (Supplemental Figure 2B) analyses. Specific deletion of c-Maf from myeloid cells did not significantly affect steady-state myeloid cell lineage distribution (Supplemental Figure 2C). However, examination of in vitro–polarized M2 BMDMs showed that macrophages from LysM-cre c-Maffl/fl mice exhibited significantly reduced CD115, CD206, and CD301 expression (Supplemental Figure 2, D–F) compared with those from control mice. In addition, polarized M2 BMDMs from c-Maf–cKO mice contained a relatively high proportion of MHC IIhi macrophages (Supplemental Figure 2G), which are considered M1-like macrophages (43).

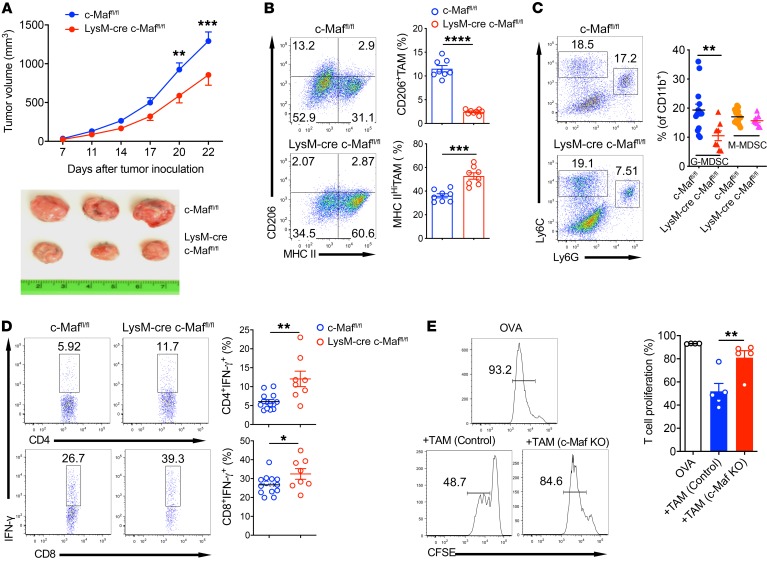

We next asked whether myeloid-specific deletion of c-Maf affected tumor growth. We injected LLC tumor cells into control and LysM-cre c-Maffl/fl mice. LysM-cre c-Maffl/fl mice exhibited significantly reduced tumor burden and bore substantially smaller tumors than control c-Maffl/fl mice (Figure 7A). In addition, TAMs from LysM-cre c-Maffl/fl mice had significantly decreased CD206 expression but upregulated MHC II expression (Figure 7B), suggesting an M1-like macrophage phenotype upon c-Maf deletion. In addition, the frequency of granulocytic MDSCs (G-MDSCs) within the tumor microenvironment (TME) was significantly reduced in LysM-cre c-Maffl/fl mice, while monocytic MDSCs (M-MDSCs) remained unchanged (Figure 7C). We also examined tumor-infiltrating T cell function. Deletion of c-Maf in myeloid cells led to significantly increased IFN-γ production in tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Figure 7D). Additionally, TAMs from LysM-cre c-Maffl/fl mice exhibited significantly reduced suppressive effects on effector CD8+ T cell proliferation (Figure 7E). These data suggest that deletion of c-Maf from myeloid cells reduces tumor progression and immunosuppression and enhances antitumor T cell immunity.

Figure 7. Deletion of c-Maf in myeloid cells suppresses tumor growth with enhanced antitumor T cell responses.

(A) c-Maffl/fl control (n = 14) and LysM-cre c-Maffl/fl mice (n = 8) were inoculated with LLC cells s.c., and tumor growth was monitored (upper). Representative tumor pictures are shown (lower). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple-comparisons test. (B) TAMs were stained for CD206 and MHC II expression. Cells were gated on CD11b+Gr-1–F4/80+ viable cells. Representative dot plots and summarized percentages of cells are shown. (C) Representative MDSC populations by flow cytometry and summarized frequencies are shown. Cells were gated on CD11b+ viable cells. (D) Single-cell suspensions from tumors were stimulated with PMA plus ionomycin and intracellular IFN-γ staining was performed. Representative dot plots and summarized data are shown. Cells were gated on CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. (E) TAMs from control and c-Maf–KO mice were cocultured with CFSE-labeled splenocytes from OVA-Tg OT-I mice in the presence of OVA. T cell proliferation was analyzed. Cells were gated on CD8+ cells. Representative histograms and percentage of proliferated cells are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001 by 2-tailed, unpaired t test (B–D); **P < 0.01 by 1-way ANOVA with post hoc t test and Bonferroni’s correction (E).

Inhibition of c-Maf with a small-molecule inhibitor overcomes resistance to anti–PD-1 in LLC s.c. tumor model. The s.c. LLC tumor model has been shown to be resistant to anti–PD-1 therapy (44). To determine whether inhibition of c-Maf would overcome this resistance, s.c. LLC tumors were established and then treated with a c-Maf small-molecule inhibitor alone or combined with anti–PD-1. Consistent with previous studies, LLC s.c. tumors were completely resistant to anti–PD-1 treatment (Supplemental Figure 3A). Inhibition of c-Maf alone showed reduced tumor burden, although the difference was not statistically significant. Combined anti–PD-1 and c-Maf inhibitor resulted in an attenuation of tumor growth that became significant by day 20 (Supplemental Figure 3A). In addition, IFN-γ–producing and TNF-α–producing CD8+ T cells were significantly increased in the tumors (Supplemental Figure 3B) and draining lymph nodes (Supplemental Figure 3C) from LLC-bearing mice treated with combined anti–PD-1 and c-Maf inhibitor. These data suggest that inhibition of c-Maf may be used as a novel approach to overcome immunocheckpoint-blockade resistance.

c-Maf is constitutively expressed in human M2 macrophages, TAMs/monocytes, and peripheral blood monocytes of NSCLC patients.

To ascertain the relevance of our findings in humans, we first examined c-Maf expression in polarized human macrophages. c-Maf was highly expressed in human M2-like but almost absent in M1-like macrophages (Supplemental Figure 4A). This was shown by flow cytometric analysis and WB. Knockdown of c-Maf in human M2-like macrophages significantly decreased the mRNA levels of IL10 and IL23p19, while it increased IL12p35 and IL6 mRNA expression levels (Supplemental Figure 4B). Similarly to murine M2-like macrophages, inhibition of c-Maf in human M2-polarized macrophages significantly decreased CSF-1R (CD115) and CD301 expression (Supplemental Figure 4C), suggesting that c-Maf has a similar regulatory effect on human M2 macrophage polarization. We next examined whether inhibition of c-Maf expression in human M2 macrophages affected their immunosuppression of effector T cells. Indeed, inhibition of c-Maf in human M2 macrophages abrogated M2-mediated suppressive effects on effector T cell proliferation and IFN-γ production (Supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that c-Maf is also critical in controlling human macrophage immunosuppressive function.

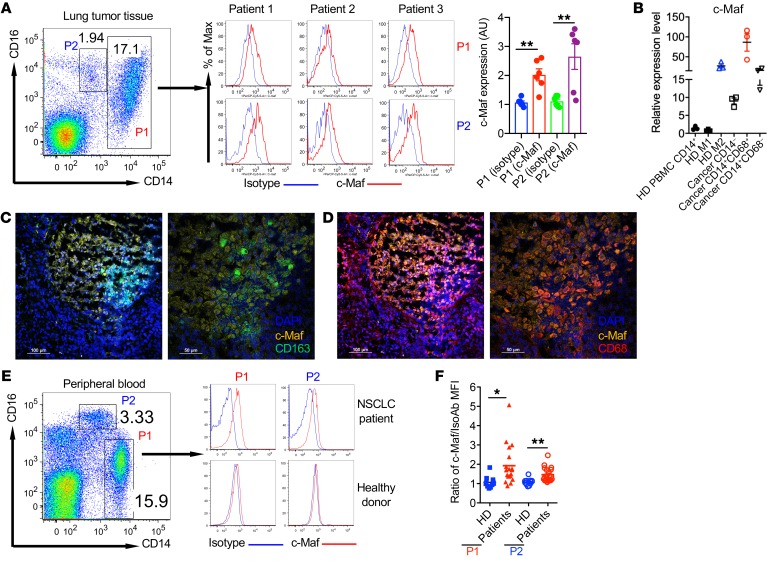

Next, we examined whether c-Maf is also expressed in human tumor-infiltrating macrophages. Freshly excised lung tumor tissues were collected from NSCLC patients who underwent surgery without any prior treatment including chemo- or radiotherapy. In the human NSCLC microenvironment, 2 main subsets of macrophages/monocytes were observed, CD14hiCD16+/lo (P1) and CD14dimCD16+ (P2) populations. c-Maf expression was readily seen in both populations from lung cancer tissues (Figure 8A). Compared with isotype control, both subsets exhibited varying but increased c-Maf expression levels. We also sorted CD14+ monocytes/macrophages from healthy donor peripheral blood and lung cancer tissues. Polarized M1 and M2 macrophages were used as control. As shown in Figure 8B, M2 macrophages expressed high levels of c-Maf compared with M1. CD14+CD68+ macrophages from lung cancer tissue expressed the highest c-Maf mRNA level, while CD14+CD68– monocytes and M2 macrophages expressed similar levels. CD14+ monocytes and M1 macrophages from healthy donor peripheral blood expressed similarly low levels of c-Maf. Histological review of lung tumors stained for the commonly used macrophage marker CD68 and M2-like marker CD163 showed that the majority of CD163+ macrophages colocalized with c-Maf (Figure 8C), while CD68+ cells were scattered throughout lung tumors and a subset of them were also colocalized with c-Maf expression (Figure 8D).

Figure 8. c-Maf is expressed in tumor-infiltrating monocytes/macrophages and circulating monocytes of NSCLC patients.

(A) c-Maf expression in human NSCLC monocytes/macrophages. Single-cell suspensions from lung tumor tissues of NSCLC patients (n = 6) were stained for CD45, CD3, CD19, CD14, CD16, and c-Maf. Histograms from 3 patients are shown. Cells were gated on CD45+CD19–CD3–CD14hiCD16+/lo (P1) or CD45+CD19–CD3–CD14dimCD16+ (P2). c-Maf expression is shown as arbitrary units (AU), calculated using MFI from 1 patient sample stained with isotype control as the denominator. **P < 0.01 by 2-tailed, unpaired t test. (B) CD14+ cells were sorted from healthy donor peripheral blood and CD14+CD68+, CD14+CD68–, or CD14–CD45+ cells were sorted from human NSCLC tissues. The c-Maf mRNA expression levels were measured by qPCR analysis. (C and D) Immunofluorescent staining of cryostat slides from NSCLC with anti-CD163 (C) or anti-CD68 (D), c-Maf, and DAPI. (E and F) c-Maf expression in peripheral blood monocytes from NSCLC patients (n = 16) and healthy donors (n = 11). Representative histograms (E) and summarized data (F) are shown. HD, healthy donors. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by 2-tailed, unpaired t test.

Human TAMs are thought to arise from circulating peripheral blood monocytes, at least in part (45). We therefore examined c-Maf expression levels in peripheral blood monocytes from NSCLC patients. c-Maf was significantly upregulated in both monocyte populations of NSCLC patients, particularly for patients with high c-Maf expression level, but not in those of healthy donors (Figure 8, E and F). To examine whether c-Maf expression is correlated with human cancer patient survival, human protein atlas data sets with a pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome were used to examine correlations between c-Maf mRNA expression levels and patient survival in different cancer types (46). Significantly worse survival was correlated with high c-Maf expression in many human cancers including renal carcinoma, hepatic cancer, ovarian cancer, glioma, and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) (Supplemental Figure 6). Taken together, these data suggest that the transcription factor c-Maf may play a critical role in human M2 macrophage and TAM polarization in human lung cancer and high expression of c-Maf correlates with poor survival in many human cancers.

Treatment with the natural product β-glucan downregulates c-Maf in murine and human M2-like macrophages and promotes antitumor immunity in mice.

Because c-Maf is highly expressed in immunosuppressive TAMs, it is desirable to find compounds that can reduce or inhibit c-Maf expression in macrophages, leading to an effective cancer immunotherapy. Fungal β-glucans are natural compounds that have been shown to trigger phagocytosis, generation of superoxide by NADPH oxidase, and inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages (47–50). Yeast-derived whole β-glucan particle (WGP) treatment converted M2-like macrophages to an M1-like phenotype (Supplemental Figure 7A). Similar results were shown with TAMs (data not shown). We found that c-Maf expression in M2 BMDMs was drastically downregulated upon WGP treatment in a dectin-1–dependent manner (Supplemental Figure 8A). β-Glucan treatment also significantly downregulated c-Maf expression in TAMs, as revealed by WB and qPCR analysis (Supplemental Figure 8B). Downregulation of Arg1 and Il10 mRNA expression by WGP was completely abrogated when c-Maf was knocked down, while enhanced mRNA expression levels of Inos, Il12, Tnfa, Il6, and Il1b in WGP-stimulated M2 BMDMs were partly dependent on c-Maf (Supplemental Figure 8C). Consistent with previous studies (34, 51, 52), tumor-bearing mice treated with WGP exhibited significantly reduced tumor burden (Supplemental Figure 7B) and the efficacy was, in part, dependent on macrophages, as depletion of macrophages reduced WGP’s therapeutic efficacy (Supplemental Figure 7C). Accordingly, TAMs from WGP-treated mice had increased mRNA expression levels of Il12 and Tnfa, while Arg1 and Il10 were decreased (Supplemental Figure 7D). Antitumor T cell responses were also enhanced upon in vivo WGP treatment. CD8+ T cells were significantly increased in spleen and draining lymph nodes from WGP-treated mice (Supplemental Figure 7E). In addition, IFN-γ–producing CD8+ T cells were increased in tumors from WGP-treated mice. Taken together, these findings suggest that WGP-mediated c-Maf downregulation in macrophages induces enhanced antitumor immunity in vivo, leading to decreased tumor progression.

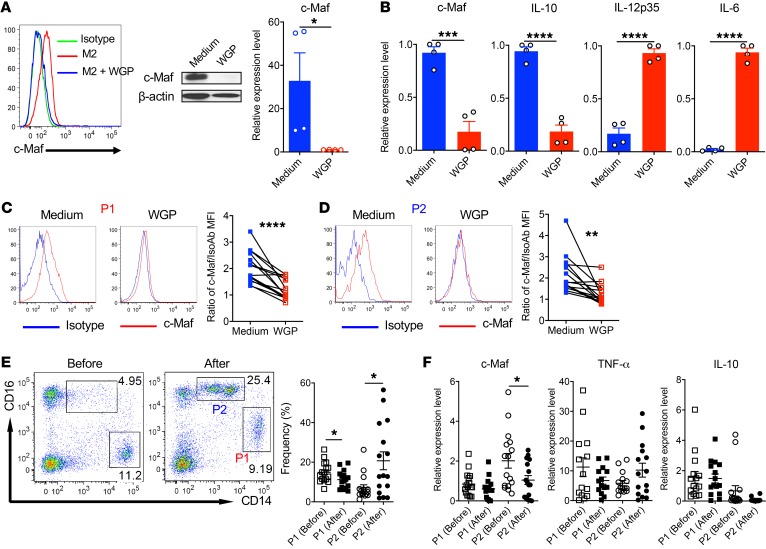

We next determined whether β-glucan downregulates c-Maf in human M2-like macrophages. WGP in vitro treatment completely abrogated c-Maf expression in polarized human M2-like macrophages from different donors, as revealed by flow cytometric analysis, WB, and qPCR analysis (Figure 9A). In addition, WGP treatment downregulated IL10 mRNA expression but increased IL12p35 and IL6 expression (Figure 9B). As shown above, c-Maf was expressed in circulating CD14hiCD16+/lo (P1) and CD14dimCD16+ (P2) monocytes in peripheral blood of NSCLC patients compared with that in healthy donors (Figure 8E). In vitro WGP treatment significantly downregulated c-Maf expression in both populations (Figure 9, C and D). To further examine β-glucan’s effect in vivo, a clinical trial was conducted at our center (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00682032). We recruited newly diagnosed NSCLC patients who had not received any other treatment to participate in the β-glucan clinical trial. WGP was given orally for 10 to 14 days at a daily 750-mg dose. Peripheral blood was drawn before and after WGP treatment. The frequency of circulating CD14hiCD16+/lo (P1) monocytes was significantly decreased, while that of CD14dimCD16+ (P2) monocytes was significantly increased upon WGP treatment (Figure 9E). In addition, c-Maf mRNA expression was significantly decreased in circulating CD14dimCD16+ (P2) monocytes, corresponding with increased TNFA mRNA expression and decreased IL10 expression (Figure 9F). These results suggest that in vivo treatment with the natural compound β-glucan alters peripheral monocyte composition and reduces c-Maf expression in CD14dimCD16+ monocytes from NSCLC patients.

Figure 9. WGP treatment downregulates c-Maf expression in human M2-like macrophages and circulating monocytes from NSCLC patients.

(A) Polarized human M2-like macrophages from heathy donor monocytes were treated with yeast whole β-glucan particles (WGP, 150 μg/mL) for 24 hours and c-Maf expression was determined by flow cytometry and WB analysis. The c-Maf mRNA expression levels in polarized M2-like macrophages (n = 4 donors) treated with WGP for 24 hours were also determined by qPCR analysis. *P < 0.05 by 2-tailed, unpaired t test. (B) Polarized human M2-like macrophages were treated with WGP (150 μg/mL) for 24 hours and the mRNA expression levels of indicated genes were determined by qPCR analysis. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by 2-tailed, unpaired t test. (C and D) PBMCs from NSCLC patients (n = 15) were treated with WGP in vitro for 24 hours. Representative histogram of c-Maf expression and summarized data for both CD14hiCD16+/lo (P1, C) and CD14dimCD16+ (P2, D) populations are shown. **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001 by 2-tailed, paired t test. IsoAb, isotype antibody. (E) PBMCs from NSCLC patients (n = 16) before or after oral WGP administration were stained for CD14 and CD16. Representative dot plots and summarized frequencies of CD14hiCD16+/lo (P1) and CD14dimCD16+ (P2) populations are shown. *P < 0.05 by 2-tailed, paired t test. (F) CD14hiCD16+/lo (P1) and CD14dimCD16+ (P2) populations from PBMCs of NSCLC patients treated before and after WGP were sorted. The mRNA expression levels of c-MAF, TNFA, and IL10 were determined by qPCR analysis. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 by 2-tailed, paired t test.

Discussion

Here, we identified c-Maf as an essential regulator for immunosuppressive macrophage polarization and effector function. c-Maf is predominantly expressed in M2-like macrophages and TAMs in both mouse and human. c-Maf directly activates Csf-1r and controls key genes critical for M2-like macrophages and TAM differentiation and function. c-Maf is also a critical metabolic switch that controls oxidative phosphorylation and the N-glycan synthesis pathway, thus reprogramming macrophages toward the M2-like phenotype. Inhibition or abrogation of c-Maf in macrophages results in an M1-like phenotype with diminished immunosuppressive function and promotes antitumor T cell immunity, leading to significantly reduced tumor progression. Taken together, our findings define c-Maf as a core node in immunosuppressive macrophage polarization and function and suggest that c-Maf is a potential target for an effective tumor immunotherapy.

c-Maf is expressed in polarized M2-like macrophages and controls many M2-related genes far beyond IL-10 and IL-12, as previously reported (31, 32). Ectopic expression of c-Maf in polarized M1-like macrophages drives them into an M2-like phenotype, suggesting that c-Maf is an essential controller for M2-like macrophage polarization. ChIP-seq data suggest that c-Maf has direct binding sites in the Csf-1r gene and regulates CSF-1R expression on macrophages. It appears that c-Maf and CSF-1R collaboratively govern macrophage polarization and function. It will be interesting to further examine whether c-Maf directly or indirectly regulates other M2-related transcription factors such as c-Myc, IRF-4, and PPARγ, thus establishing a regulatory network that controls M2-like macrophage polarization. Indeed, Irf4 mRNA expression is reduced in c-Maf–deficient M2 BMDMs (Figure 2B). CSF-1R expression on macrophages has been shown to induce immunosuppression, thus promoting tumor progression (35). CSF-1R+ TAMs are associated with worse prognosis and drive resistance to tumor immunotherapy (53, 54). Our study reveals that inhibition or deletion of c-Maf in macrophages diminishes CSF-1R expression on M2 BMDMs and TAMs. This is shown in both murine and human M2 macrophages. A previous study showed that CSF-1R signaling promotes MHC IIlo TAM differentiation (55). Indeed, TAMs or M2 BMDMs from c-Maf–cKO mice have a significantly decreased MHC IIlo population. These findings suggest that c-Maf regulates macrophage immunosuppressive function, at least in part through control of CSF-1R expression and activity.

Our data suggest that c-Maf controls macrophage phenotype also through metabolic reprogramming, as c-Maf regulates several key enzymes such as IDH in the TCA cycle and the UDP-GlcNAc biosynthesis pathway. Inhibition of c-Maf in M2-like macrophages suppresses IDH1/IDH2 expression at both the transcriptional level and the steady-state metabolic level. The partial discontinuity of the TCA cycle at IDH is further confirmed by the systems metabolomics pathway flow studies, as αKG abundance is reduced upon inhibition of c-Maf expression. This is reminiscent of M1-like macrophages, as they bear a metabolic break at IDH (40). Interestingly, αKG is also critical for M2-like macrophage activation through fatty acid oxidation and epigenetic reprogramming (56), although the main source of αKG production is thought to be via glutaminolysis. The metabolic change upon c-Maf inhibition is also consistent with the overall macrophage phenotype change, as macrophages from c-Maf–KO mice display increased Il12, Tnfa, and Il1b but decreased Il10, Arg1, Tgfb, and Vegf, resembling an M1-like phenotype. In addition, we demonstrate that c-Maf controls the UDP-GlcNAc biosynthesis pathway. Inhibition of c-Maf leads to reduced N-glycosylation, a pathway critical for M2 macrophage polarization and one that requires UDP-GlcNAc as a sugar donor that affects M2 macrophage activation as measured by CD301 expression. CD301 is a member of the C-type lectin superfamily and is expressed on M2-like macrophages and immature dendritic cells in both mouse and human.

Macrophages within the TME have a heterogenic phenotype (11). We found that c-Maf is highly expressed in CD11b+Gr-1–F4/80+MHCIIlo TAMs from LLC-bearing mice, which exhibit potent immunosuppressive effects on effector T cells. We show that c-Maf controls several key regulatory genes in immunosuppressive TAMs including those encoding IDO, IL-10, arginase, and VEGF, which are associated with TAM-mediated immunosuppression and angiogenesis. In addition, knockdown of c-Maf in TAMs significantly enhances effector T cell function, leading to reduced tumor burden and progression. Similarly to polarized M2 BMDMs, inhibition of c-Maf in TAMs also represses CSF-1R and CD301 expression, with decreased oxidative pathway activity, indicating similar regulatory effects of c-Maf in immunosuppressive TAMs. LysM-cre c-Maffl/fl mice exhibit significantly reduced tumor burden, further suggesting the critical role that c-Maf plays in regulating antitumor immune responses. It is worth noting that c-Maf deficiency did not significantly alter the overall number of macrophages. However, c-Maf expression in myeloid cells shifts the MHC IIlo/MHC IIhi TAM balance. MHC IIhi TAMs are considered to be of the M1 phenotype, while MHC IIlo have M2 features (57). Although the regulation of c-Maf itself in TAMs is not well understood, previous studies have shown that IL-10 promotes c-Maf expression in macrophages (58). IL-10 is abundant in the TME and can be secreted by cancer cells and immune cells.

We also found that c-Maf is expressed in 2 subsets of monocytes/macrophages within human NSCLC. This is revealed by both flow cytometry and immunofluorescent staining. In contrast, CD14+ monocytes from healthy donors express negligible levels of c-Maf. CD163+c-Maf+ TAMs have been shown to be associated with worse progression-free survival in pediatric classical Hodgkin lymphoma (59), and intratumoral IL-17+CD163+c-Maf+ macrophages are associated with NSCLC progression (60). Human protein atlas analysis shows that high expression of c-Maf in tumors correlates with poor survival in many human cancers. In human NSCLC, tumor-infiltrating CD14+ cells exhibited a heterogeneous morphology, with cells resembling both monocytes and macrophages (61) and they may be derived from both the periphery and yolk sac. Previous studies have shown that there are at least 2 circulating monocytes in the peripheral blood: classical inflammatory monocytes (CCR2hiCD14hiCD16–), which are associated with tumor early growth and metastasis, and nonclassical patrolling monocytes (CX3CR1hiCD14dimCD16+), which are considered to have antitumor effects (62). c-Maf is significantly expressed in circulating CD14hiCD16+/lo and CD14dimCD16+ monocytes in peripheral blood of NSCLC patients, but not in healthy donors, suggesting that c-Maf may be used as a biomarker for cancer diagnosis and treatment responses. It will be interesting to further examine whether c-Maf expression levels in circulating monocytes are correlated with immunotherapy response.

Cancer immunotherapy such as anti–PD-1 immunocheckpoint blockade has been widely used in NSCLC patients. However, many patients are resistant to such treatment. We sought to determine whether inhibition of c-Maf may overcome such resistance. Indeed, anti–PD-1 combined with a c-Maf small-molecule inhibitor significantly reduced tumor progression. Because c-Maf is the critical transcription factor for many subsets of immune cells, we thus explored immunomodulators that can specifically target c-Maf in macrophages. Yeast-derived β-glucans have been shown to have potent antitumor effects through activating macrophages, dendritic cells, and reprogramming immunosuppressive myeloid cells (34, 51, 52, 63, 64). Here, we showed that yeast-derived particulate–β-glucan treatment abrogates c-Maf expression in polarized mouse M2-like macrophages and immunosuppressive TAMs. We also showed that β-glucan in vitro treatment significantly downregulates c-Maf expression in human polarized M2 macrophages as well as circulating CD14hiCD16+/lo and CD14dimCD16+ monocytes from NSCLC patients. To translate these findings into potential clinical utilization, we conducted a clinical trial to examine β-glucan’s in vivo effect on monocytic c-Maf expression in NSCLC patients. In this trial, patients took particulate β-glucan capsules daily for 10 to 14 days. Unexpectedly, we found that β-glucan treatment significantly alters the frequencies of 2 monocyte subsets, with increased CD14dimCD16+ monocytes and decreased CD14hiCD16+/lo monocytes. Although we did not examine CCR2 or CX3CR1 expression on these monocytes, it is possible that β-glucan treatment significantly increases nonclassical patrolling monocytes and decreases classical inflammatory monocytes. Because nonclassical patrolling monocytes have the ability to control tumor metastasis (62, 65), it will be interesting to investigate whether β-glucan treatment provides long-term survival benefit for NSCLC patients. It is worth noting that although oral administration of β-glucan downregulates c-Maf expression in patrolling monocytes, it remains to be seen whether c-Maf is diminished in TAMs, owing to its heterogeneity. Nevertheless, targeting immunosuppressive macrophages by β-glucan via inhibition of c-Maf may offer a novel strategy to enhance current cancer immunotherapies such as immunocheckpoint-inhibitor therapy.

Methods

Human subjects.

Newly diagnosed, treatment-naive NSCLC patients and sex- and age range–matched healthy donors were recruited at the James Graham Brown Cancer Center, University of Louisville. The clinical pathological features of NSCLC patients are summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Mice and in vivo tumor models.

OT-I and OT-II mice were purchased from Taconic. Dectin-1–KO mice were described previously (51). To generate c-Maf–KO and WT chimeric mice, the donor cells were prepared from E14.5 fetal livers of WT and c-Maf–KO (C57BL/6J-Ly5.1) mice. Suspensions of single fetal liver cells were prepared and adoptively transferred into lethally irradiated C57BL/6J-Ly5.2 mice. The mice with greater than 95% reconstitution were used for analysis (42). To generate myeloid cell–specific c-Maf–deleted mice, c-Maffl/fl mice were first generated using CRISPR/Cas9 technology by Biocytogen and then bred with LysM-cre mice (Jackson Laboratory) to generate control c-Maffl/fl mice and LysM-cre c-Maffl/fl cKO mice.

For tumor protocols, LLC cells were mixed with IL-4/IL-13–polarized M2 BMDMs (2.5:1) from WT or c-Maf–KO chimeric mice in Matrigel (Corning) and then injected s.c. into C57BL/6 mice. In other protocols, LLC cells (5 × 105) were inoculated s.c. into control and LysM-cre c-Maffl/fl mice. For the macrophage depletion protocol, mice were injected i.v. with 100 μL clodronate (5 mg/mL, Clodrosome; Encapsula NanoSciences) 1 day before LLC s.c. inoculation. Mice were then injected with clodronate weekly during the experiment. For anti–PD-1 treatment, mice were inoculated s.c. with LLC cells (5 × 105/mouse). On day 8 after palpable tumors formed, mice were treated with c-Maf inhibitor Nivalenol (1 mg/kg, daily; Cayman Chemical) with or without anti–PD-1 (100 μg/mouse, 4 times; BioXCell, BE0146, clone RMP1-14). For the WGP (Biothera) treatment protocol, mice were inoculated with LLC cells (5 × 105/mouse). On day 8 after palpable tumors formed, mice were treated with WGP orally (800 μg/mouse) or 100 μL PBS every day using an intragastric gavage needle. Tumor diameters were measured every third day. Tumor volume was calculated by the following formula: length × width2/2.

Macrophage polarization and TAM purification.

For mouse macrophage polarization, BM cells isolated from the femurs and tibias were cultured in complete DMEM containing 10 ng/mL M-CSF. The medium was changed on day 3 and cells were cultured for an additional 3 days to generate M0 macrophages. For M2 polarization, cells were stimulated with IL-4 and IL-13 (20 ng/mL) for 2 days. For M1 macrophage polarization, cells were cultured in the presence of LPS (100 ng/mL) and IFN-γ (20 ng/mL) for 2 days. In some experiments, GM-CSF (50 ng/mL, BD) or M-CSF (100 ng/mL, Peprotech) was added to polarize the M1 or M2 macrophages, respectively.

For human macrophage polarization, PBMCs from healthy donors were isolated and CD14+ monocytes were sorted by BD FACSAria III. CD14+ monocytes were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 containing 100 ng/mL M-CSF. The medium was replaced with fresh medium on day 4 and cells were cultured for an additional 3 days to differentiate into M0 macrophages. On day 7, M1 macrophages were induced after 2 days of culture in the presence of LPS (100 ng/mL) and IFN-γ (20 ng/mL). M2 polarization was induced by IL-4 and IL-13 (20 ng/mL). In some experiments, GM-CSF (50 ng/mL, Berlex) or M-CSF (100 ng/mL, Peprotech) was added to polarize the M1 or the M2 macrophages, respectively.

For TAM purification, LLC tumors (12–15 mm) were minced and then digested with buffer containing collagenase IV, hyaluronidase, and DNase I at 37°C for 30 minutes. Single-cell suspensions were separated using 60% and 30% Percoll and the middle layer of cells was collected, washed, and resuspended in MACS running buffer. Cells were stained with biotin-labeled anti–mouse F4/80 antibody and then washed and incubated with streptavidin microbeads on ice for 15 minutes. TAMs were purified by AutoMACS separator (Miltenyi Biotec). These cells were CD11b+F4/80hi.

Lentivirus infection.

Polarized M1 BMDMs were plated in a 12-well plate 24 hours before infection. On the day of infection, the lentivirus-containing supernatants were thawed in a 37°C water bath. Each well of M1 BMDMs was infected with 25 μL control or c-Maf lentivirus (1 × 108 IU/mL, Applied Biological Materials [abm]) at a final concentration of 10 MOI in the presence of polybrene at a final concentration of 8 μg/mL. The plate was incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. On the following day, the viral supernatant was removed and complete medium was added to the plate. On day 5, cells were harvested for subsequent experiments.

c-Maf siRNA knockdown.

M2 BMDMs or TAMs were transfected with c-Maf siRNA or control siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) using HiPerFect transfection reagent (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After incubation with transfection complexes for 6 hours, cells were cultured in regular medium overnight.

c-Maf ChIP-seq and ChIP-qPCR.

In vitro–polarized M2 BMDMs were used for ChIP studies as described previously (66). In brief, cells were subjected to sonication using a sonicator (AFA Focused-ultrasonicator S220) to obtain chromatin fragments of 100 to 500 bp. Fragmented chromatin was incubated with c-Maf antibody (LifeSpan BioSciences, Inc., LS-C287488) or control normal rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology) and incubated for cross-linking with beads (Dynabeads Protein G, Invitrogen). Crosslinks were reversed (65°C for 12–16 hours), and precipitated DNA was treated with Proteinase K and then purified (QIAquick PCR purification kit, QIAGEN). The DNA libraries were prepared and sequencing was performed by BGI (Beijing Genomics Institute). The number of clean reads is approximately 24 million. The ChIP-seq data have been deposited into NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with the accession number GSE139039. The primer sequences of Csf-1r CNS + 3 and controls for ChIP-qPCR analysis are listed in Supplemental Table 2. ChIP-seq peaks were detected using MACS version 1.4.2 callpeak (67), with the broad peaks flag removed and a P-value cutoff of 0.01 (command line options –B –p 0.01). Differential peaks were detected using the MACS2 bdgdiff command with command line options –d1 21370300 –d2 21370300 –c 2 –g 60 –l 120. For c-Maf binding motif analysis, the overlapping regions between the 2 differential peak lists were ranked by the differences between isotype mAb and c-Maf mAb reads, and peaks that had fewer than 10 more reads were removed. The sequences were used as input into the MEME motif discovery software, using the OOPS model (1 occurrence per sequence) (68).

Luciferase assay.

To construct the luciferase reporter plasmid for mouse c-Maf binding to the Csf-1r region (pGL3-csf1r), a 391-bp DNA fragment (chr18: 61108579–61108969) of the mouse Csf-1r gene promoter including the c-Maf binding motif (MARE) was amplified by PCR using mouse genomic DNA as template and primers 5′-GGGATCCAAGGACAATGGCCAGGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGAAGCTTGAATGCCATGCTCATGAAG-3′ (reverse). The amplified DNA fragment was digested with KpnI and HindIII and then subcloned into the pGL3 vector. The c-Maf binding motif mutant reporter plasmids (csf1r mut1 [5′MARE], mut2 [3′ MARE], and mut3 [5′ and 3′ MARE]) were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the following mutation primer pairs: mut1 forward, 5′-GTATCCCACCACACAGGCA-3′; mut1 reverse, 5′-GGATACTTTTTCCCAGGCT-3′; mut2 forward, 5′-GTATCCGACTGGGTACCTC-3′; mut2 reverse, 5′-GGATACGGTACCCAGTCTG-3′; for mut3 we used the mut1 and mut2 primer pairs. The motif mutations were amplified by PCR using pGL3-csf1r as template together with c-Maf binding motif primers and mutation primers, respectively. The amplified mutant motif fragments were digested with KpnI and HindIII and then subcloned into the pGL3 vector.

M2 BMDMs from c-Maf control and cKO mice were transfected with pGL3, pGL3-csf1r, pGL3-mut1, pGL3-mut2, and pGL3-mut3 plasmids, respectively. Luciferase assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, M2 BMDMs transfected with different plasmids were washed with PBS and 50 μL of lysis buffer was added to the wells. The cells were scraped from the wells and then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 2 minutes at 4°C to collect supernatants. Luciferase activity was measured by mixing 20 μL of cell lysate with 100 μL of Luciferase Assay Reagent (E4030, Promega). Luciferase activity was read with a luminometer (Femtomaster FB12). Luciferase values and data are presented as relative light units (RLU) or fold-change relative to WT Csf-1r CNS + 3, as appropriate.

Extracellular flux analysis of cellular energetics and tracer and SIRM analyses.

Cellular energetics in macrophages was measured by extracellular flux (XF) analysis (69). Sixty thousand M2 BMDMs or TAMs pretreated with c-Maf inhibitor Nivalenol (100 ng/mL) or vehicle were plated into each well of an XF24 culture plate and placed in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 16 hours. The following morning the medium was changed to unbuffered DMEM containing 25 mM glucose and 4 mM glutamine (pH 7.4), and the cells were then placed in a non-CO2 incubator at 37°C for 1 hour. Basal OCR and ECAR were measured using a Seahorse XF24 analyzer. Mitochondrial and glycolytic activities were further interrogated by exposing cells sequentially to the following compounds: port A, oligomycin (1 μM); port B, carbonyl cyanide-p-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 1 μM); port C, antimycin A and rotenone (10 μM and 1 μM); and port D, koningic acid (50 μM). Oligomycin, FCCP, antimycin A, and rotenone were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich, while koningic acid was purchased from TMS Co., Ltd. At completion of the programmed protocol, OCR and ECAR values were normalized to the total amount of protein per well.

For tracer and SIRM analyses, M2 BMDMs treated with c-Maf inhibitor (100 ng/mL) or vehicle control for 24 hours in glucose-free DMEM supplemented with 10 mM [U-13C]-glucose and 10% dialyzed FBS. The cells were rinsed in cold PBS and quenched using a mixture containing 2 mL acetonitrile and 1.5 mL H2O. After adding 1 mL chloroform, the sample was homogenized and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm, 4°C for 20 minutes. The top layer was transferred to a new tube and lyophilized. The dried sample was then dissolved in 100 μL 20% acetonitrile and vigorously vortex-mixed for 3 minutes. After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm, 4°C for 20 minutes, the supernatant was collected for 2-dimensional liquid chromatography–tandem MS (2DLC-MS/MS) analysis. All samples were analyzed on a Thermo Q Exactive HF Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer coupled with a Thermo DIONEX UltiMate 3000 HPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The UltiMate 3000 HPLC system was equipped with a reverse-phase chromatography (RPC) column and a hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) column. The 2 columns were configured in parallel 2DLC mode.

For 2DLC separation, H2O with 0.1% formic acid was used as the mobile phase A for RPC and 10 mM ammonium acetate (pH 3.25) was used as the mobile phase A for HILIC. Acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid was used as mobile phase B for both RPC and HILIC. To avoid systemic bias, the samples were analyzed by 2DLC-MS in random order. All samples were first analyzed by 2DLC-MS positive mode followed by 2DLC-MS negative mode, to obtain the full MS data of each metabolite. For quality control purposes, a group-based pooled sample was prepared by mixing a small portion of the supernatant from all unlabeled samples in 1 group. One pooled sample was analyzed by 2DLC-MS after injection of every 5 biological samples. All pooled samples were also analyzed by 2DLC-MS/MS in positive and negative mode respectively to acquire MS/MS spectra of each metabolite at 3 collision energies (20 eV, 40 eV, and 60 eV).

MetSign software was used for spectrum deconvolution, metabolite identification, cross-sample peak list alignment, normalization, and statistical analysis (70, 71). For a metabolite of interest with poor chromatographic peak shape, its peak area was further validated using Xcalibur software (v2.2 SP1, Thermo Fisher Scientific). To identify metabolites, the 2DLC-MS/MS data of the pooled samples were first matched to an in-house MS/MS database that contains the parent ion m/z, MS/MS spectra, and retention time of 205 metabolite standards. The thresholds used for metabolite identification were MS/MS spectral similarity equal to or greater than 0.4, retention time difference of 0.15 minutes or less, and m/z difference of 4 ppm or less. The 2DLC-MS/MS data without a match in the in-house database were then analyzed using Compound Discoverer software (v2.0, Thermo Fisher Scientific), where the threshold of the MS/MS spectrum similarity score was set as 40 or greater with a maximum score of 100. The remaining peaks that did not have a match were then matched to the metabolites in the in-house MS/MS database using the parent ion m/z and retention time to identify metabolites that do not have MS/MS spectra. The thresholds for assignment were parent ion m/z equal to or less than 4 ppm and retention time difference of 0.15 minutes or less.

In vitro M2 BMM– or TAM–T cell coculture assay.

Polarized M2 BMDMs or TAMs from LLC-bearing mice were cocultured with CFSE-labeled splenocytes from OT-I or OT-II mice in the presence of OVA for 3 days. In some experiments, control or c-Maf siRNA–transfected TAMs or M2 BMDMs from WT or c-Maf–KO chimeric mice were cocultured with OT-I or OT-II splenocytes in the presence of OVA. Cells were restimulated with PMA plus ionomycin for 6 hours and then stained with anti-CD8 or -CD4 mAbs, fixed, and permeabilized for intracellular cytokine staining. Data were acquired on a FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD Immunocytometry Systems) and analyzed by FlowJo software (Tree Star).

RNA microarray analysis and qPCR.

RNAs were extracted with a QIAGEN RNeasy kit and Agilent oligonucleotide arrays were processed and analyzed. The array data have been deposited into NCBI’s GEO with the accession number GSE139541. For qPCR analysis, RNA samples were transcribed into cDNA with a Reverse Transcription Kit (Bio-Rad). qPCR was then performed on a MyiQ RT-PCR detection system with SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences for each gene are summarized in Supplemental Table 2.

Single-cell suspensions prepared from human lung cancer tissues.

Fresh lung cancer tissues were obtained from patients with NSCLC who underwent surgical resection at the JG Brown Cancer Center, University of Louisville. None of the patients had received radiotherapy or chemotherapy before surgery. All samples were anonymously coded in accordance with local ethical guidelines (as stipulated by the Declaration of Helsinki), and written informed consent was obtained. Freshly excised tissues were cut into small pieces and then digested in RPMI 1640 medium containing 2% FBS, type IV collagenase (1 μg/mL), and hyaluronidase (10 ng/mL) for 20–40 minutes at 37°C. Single-cell suspensions were stained with fluorescent dye–labeled mAbs including anti-CD45 (Biolegend, clone 2D1), -CD3 (Biolegend, clone OKT3), -CD19 (Biolegend, clone 4G7), -CD14 (Biolegend, clone 63D3), -CD16 (Biolegend, clone 3G8), and –c-Maf (Invitrogen, clone sym0F1). c-Maf staining was performed intracellularly. Cells were analyzed in a FACSCanto II flow cytometer.

Statistics.

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The 2-tailed unpaired Student t test was used to determine the significance of differences between 2 groups. The 2-tailed paired t test was used to compare the before-after measurements. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparisons test was used to make comparisons with the control group, and 1-way ANOVA with post hoc t test and Bonferroni’s correction was used to make planned comparisons. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple-comparisons test was used to make within-group comparisons. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare tumor growth curves between different groups. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software).

Study approval.

The human subject study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Board at the University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA. All tissue and blood samples were obtained upon written informed consent. All mouse studies were performed in compliance with all relevant laws and institutional guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Louisville.

Author contributions

ML initiated this project and performed in vitro and in vivo WGP treatment experiments. ZT performed all metabolism-related experiments and human subject studies. CD performed all experiments related to c-Maf chimeric mice and cKO mice and participated in human subject studies. FL performed all c-Maf knockdown experiments and participated in human subject studies. SW, SA, LH, CW, and XH performed supporting experiments. DT and ECR performed bioinformatics analysis. MH and ST performed c-Maf chimeric mouse studies and processed and analyzed the Agilent oligonucleotide arrays. AAG, HZ, BGH, and XZ provided critical resources. GK and MB supervised human subject studies. JY provided overall supervision and wrote the manuscript. ML, ZT, CD, and FL share co–first author position. The method used in assigning the authorship order among these authors are based on the time order in which they worked on this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01CA213990 and P01CA163223, and the Kentucky Lung Cancer Research Program (to JY). This work was also supported by NIH Instrument grant 1S10OD20106. Sequencing and bioinformatics support was provided by NIH grants P20GM103436 and P30GM106396. The authors also thank M. Hall and A. Harper for recruiting NSCLC patients and thank Douglas Dean for critical reading of this manuscript and Maiying Kong for consultation of statistical analyses.

Version 1. 01/16/2020

In-Press Preview

Version 2. 03/16/2020

Electronic publication

Version 3. 04/01/2020

Print issue publication

Footnotes

ML, ZT, and FL’s present address is: Department of Immunology, Wuhan University School of Basic Medical Science, Wuhan, China.

Conflict of interest: JY owns shares in Biothera.

Copyright: © 2020, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2020;130(4):2081–2096.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI131335.

See the related Commentary at c-Maf: A bad influence in the education of macrophages.

Contributor Information

Min Liu, Email: lliumin2002@163.com.

Zan Tong, Email: tongzanbio@gmail.com.

Chuanlin Ding, Email: c0ding01@louisville.edu.

Fengling Luo, Email: luofengling@whu.edu.cn.

Shouzhen Wu, Email: wushouzhen@qq.com.

Caijun Wu, Email: caijun.wu@louisville.edu.

Sabrin Albeituni, Email: Sabrin.Albeituni@STJUDE.ORG.

Liqing He, Email: liqing.he@louisville.edu.

Xiaoling Hu, Email: x0hu0007@louisville.edu.

David Tieri, Email: david.tieri@louisville.edu.

Eric C. Rouchka, Email: eric.rouchka@louisville.edu.

Michito Hamada, Email: hamamicchi@gmail.com.

Satoru Takahashi, Email: satoruta@md.tsukuba.ac.jp.

Andrew A. Gibb, Email: aagibb03@louisville.edu.

Goetz Kloecker, Email: goetz.kloecker@louisville.edu.

Huang-ge Zhang, Email: h0zhan17@louisville.edu.

Bradford G. Hill, Email: bghill01@louisville.edu.

Xiang Zhang, Email: xiang.zhang@louisville.edu.

Jun Yan, Email: jun.yan@louisville.edu.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garon EB, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2018–2028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gettinger SN, et al. Overall survival and long-term safety of Nivolumab (anti-programmed death 1 antibody, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(18):2004–2012. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rizvi NA, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348(6230):124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neubert NJ, et al. T cell-induced CSF1 promotes melanoma resistance to PD1 blockade. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(436):eaan3311. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Henau O, et al. Overcoming resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy by targeting PI3Kγ in myeloid cells. Nature. 2016;539(7629):443–447. doi: 10.1038/nature20554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binnewies M, et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med. 2018;24(5):541–550. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0014-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mantovani A. Cancer: Inflaming metastasis. Nature. 2009;457(7225):36–37. doi: 10.1038/457036b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollard JW. Trophic macrophages in development and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(4):259–270. doi: 10.1038/nri2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colegio OR, et al. Functional polarization of tumour-associated macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature. 2014;513(7519):559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature13490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruffell B, Coussens LM. Macrophages and therapeutic resistance in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(4):462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin H, et al. Host expression of PD-L1 determines efficacy of PD-L1 pathway blockade-mediated tumor regression. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(2):805–815. doi: 10.1172/JCI96113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poh AR, Ernst M. Targeting macrophages in cancer: from bench to bedside. Front Oncol. 2018;8:49. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu M, O’Connor RS, Trefely S, Graham K, Snyder NW, Beatty GL. Metabolic rewiring of macrophages by CpG potentiates clearance of cancer cells and overcomes tumor-expressed CD47-mediated ‘don’t-eat-me’ signal. Nat Immunol. 2019;20(3):265–275. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0292-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mills CD, Lenz LL, Harris RA. A breakthrough: macrophage-directed cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2016;76(3):513–516. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung FT, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages correlate with response to epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(3):E227–E235. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang R, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages provide a suitable microenvironment for non-small lung cancer invasion and progression. Lung Cancer. 2011;74(2):188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krausgruber T, et al. IRF5 promotes inflammatory macrophage polarization and TH1-TH17 responses. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(3):231–238. doi: 10.1038/ni.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu H, et al. Notch-RBP-J signaling regulates the transcription factor IRF8 to promote inflammatory macrophage polarization. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(7):642–650. doi: 10.1038/ni.2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang YC, et al. Notch signaling determines the M1 versus M2 polarization of macrophages in antitumor immune responses. Cancer Res. 2010;70(12):4840–4849. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satoh T, et al. The Jmjd3-Irf4 axis regulates M2 macrophage polarization and host responses against helminth infection. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(10):936–944. doi: 10.1038/ni.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(1):23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pello OM, et al. Role of c-MYC in alternative activation of human macrophages and tumor-associated macrophage biology. Blood. 2012;119(2):411–421. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-339911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue J, et al. Transcriptome-based network analysis reveals a spectrum model of human macrophage activation. Immunity. 2014;40(2):274–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishizawa M, Kataoka K, Goto N, Fujiwara KT, Kawai S. v-maf, a viral oncogene that encodes a “leucine zipper” motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(20):7711–7715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurt EM, et al. Overexpression of c-maf is a frequent oncogenic event in multiple myeloma that promotes proliferation and pathological interactions with bone marrow stroma. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(2):191–199. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(04)00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho IC, Hodge MR, Rooney JW, Glimcher LH. The proto-oncogene c-maf is responsible for tissue-specific expression of interleukin-4. Cell. 1996;85(7):973–983. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bauquet AT, et al. The costimulatory molecule ICOS regulates the expression of c-Maf and IL-21 in the development of follicular T helper cells and TH-17 cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(2):167–175. doi: 10.1038/ni.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zuberbuehler MK, et al. The transcription factor c-Maf is essential for the commitment of IL-17-producing γδ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2019;20(1):73–85. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0274-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soucie EL, et al. Lineage-specific enhancers activate self-renewal genes in macrophages and embryonic stem cells. Science. 2016;351(6274):aad5510. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao S, et al. Differential regulation of IL-12 and IL-10 gene expression in macrophages by the basic leucine zipper transcription factor c-Maf fibrosarcoma. J Immunol. 2002;169(10):5715–5725. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao S, Liu J, Song L, Ma X. The protooncogene c-Maf is an essential transcription factor for IL-10 gene expression in macrophages. J Immunol. 2005;174(6):3484–3492. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kikuchi K, et al. Macrophages switch their phenotype by regulating Maf expression during different phases of inflammation. J Immunol. 2018;201(2):635–651. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu M, et al. Dectin-1 activation by a natural product β-glucan converts immunosuppressive macrophages into an M1-like phenotype. J Immunol. 2015;195(10):5055–5065. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Candido JB, et al. CSF1R+ macrophages sustain pancreatic tumor growth through T cell suppression and maintenance of key gene programs that define the squamous subtype. Cell Rep. 2018;23(5):1448–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pyonteck SM, et al. CSF-1R inhibition alters macrophage polarization and blocks glioma progression. Nat Med. 2013;19(10):1264–1272. doi: 10.1038/nm.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ries CH, et al. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages with anti-CSF-1R antibody reveals a strategy for cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(6):846–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Través PG, et al. Relevance of the MEK/ERK signaling pathway in the metabolism of activated macrophages: a metabolomic approach. J Immunol. 2012;188(3):1402–1410. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodríguez-Prados JC, et al. Substrate fate in activated macrophages: a comparison between innate, classic, and alternative activation. J Immunol. 2010;185(1):605–614. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jha AK, et al. Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity. 2015;42(3):419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martinez P, et al. Macrophage polarization alters the expression and sulfation pattern of glycosaminoglycans. Glycobiology. 2015;25(5):502–513. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwu137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kusakabe M, et al. c-Maf plays a crucial role for the definitive erythropoiesis that accompanies erythroblastic island formation in the fetal liver. Blood. 2011;118(5):1374–1385. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-300400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tcyganov E, Mastio J, Chen E, Gabrilovich DI. Plasticity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2018;51:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ajona D, et al. A combined PD-1/C5a blockade synergistically protects against lung cancer growth and metastasis. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(7):694–703. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qian BZ, et al. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature. 2011;475(7355):222–225. doi: 10.1038/nature10138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uhlen M, et al. A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Science. 2017;357(6352):eaan2507. doi: 10.1126/science.aan2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown GD, Herre J, Williams DL, Willment JA, Marshall AS, Gordon S. Dectin-1 mediates the biological effects of beta-glucans. J Exp Med. 2003;197(9):1119–1124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steele C, et al. Alveolar macrophage-mediated killing of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. muris involves molecular recognition by the Dectin-1 beta-glucan receptor. J Exp Med. 2003;198(11):1677–1688. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]