Abstract

Bacteria move by a variety of mechanisms, but the best understood types of motility are powered by flagella (70). Flagella are complex machines embedded in the cell envelope that rotate a long extracellular helical filament like a propeller to push cells through the environment. The flagellum is one of relatively few biological machines that experience continuous 360° rotation, and it is driven by one of the most powerful motors, relative to its size, on earth. The rotational force (torque) generated at the base of the flagellum is essential for motility, niche colonization and pathogenesis. This review describes regulatory proteins that control motility at the level of torque generation.

Keywords: EpsE, YcgR, MotA, FliG, biofilm, swarming

INTRODUCTION

Flagellar-mediated motility is a conditionally advantageous phenotype, and the cost of flagellar assembly is substantial. Each flagellum is assembled from over twenty structural proteins that range from under ten to over ten thousand copies per cell. The number of flagella per cell can range from one to dozens, depending on the species. To minimize excess consumption, flagellar gene expression is tightly regulated (36,110), and the most abundant proteins appear to have evolved to avoid energetically costly amino acids (144).

Another significant cost of flagellar assembly is time. It takes about an hour to assemble a functional flagellum, and if motility is needed for nutrient acquisition and growth, the time delay an aflagellate population would suffer between induction and active motility could be disastrous (61,75). To eliminate the time delay and sequester nutrient cost, some bacteria pre-differentiate a motile subpopulation using so-called “bet-hedging” strategies of bistable/bimodal gene expression (40,58,78,113,147). Moreover, once individual cells have made the investment and become motile, there are advantages to rapidly increasing and decreasing flagellar power. Two contexts for flagellar power modulation are the multicellular behaviors of biofilm formation and swarming motility.

Biofilms are multicellular aggregates of bacteria held together by an extracellular matrix, and the cells within the biofilms are non-motile (47,88). Thus, if motile cells initiate biofilm formation, it is inferred that there must be a motility-to-biofilm transition during which motility is inhibited. Consistent with the motility-to-biofilm transition being a regulatory event, mutations that de-repress expression of biofilm-related genes also inhibit motility (60). Overproduction of extracellular matrix components, polysaccharide in particular, can impair motile dispersal simply by matrix-mediated cell cohesion. However, beyond that, flagellar rotation is also inhibited (8,19, 59, 92,139,170). Swarming motility is a hyper-motile state in which flagella propel groups of bacteria atop solid surfaces in a thin layer of liquid (79). Swarming requires an increase in flagellar thrust, which is often achieved by increasing flagellar density, but beyond that, the power output of each flagellar motor is enhanced. Thus, the direct modulation of flagellar power is necessary for both biofilm formation and swarming motility and is mediated, at least in part, by functional regulators.

Here we define “functional regulators” as proteins that directly regulate the function of the flagellum at the level of torque generation. Functional regulators are thought to have the advantages of working in a simple and rapid manner, and they operate directly on the phenotype of motility while preserving the investment in flagellar structure. Some such regulators have been interpreted using mechanical or automotive analogies (e.g., brakes and clutches), whereas others are not sufficiently understood to draw an appropriate comparison. Each functional regulator however, directly binds to and modifies parts of the flagellar motor and thus should be considered as conditional components belonging to the “mot” genetic class. To understand the mechanism behind these functional regulators, we will discuss the mechanism by which flagella rotate. We begin with a brief history of early genetic studies that led to the designations of fla, che, and mot.

Fla-che-mot and early genetic analysis.

Bacterial motility is a powerful system for genetic analysis; the phenotype is dramatic, easily assayed, and involves a large number of genes. The genetic underpinning of motility was identified as early as the 1930s by selecting for suppressor mutations that restored motility to non-motile isolates (39). Later, genetic loss of motility was found to be correlated with resistance to certain phages (106,136). One class of motility mutants was found to be defective in producing the immunological “H-antigen” associated with motility, suggesting that they lacked a structure on the cell surface (66,73,148). Another class of mutants were unable to spread through soft agar but were nonetheless visibly motile in liquid suspensions (1,6). Finally, a third class of mutants were non-motile in both soft agar and liquid but retained the H-antigen (45,48,76). Thus, the combined genetic and physiological approaches identified mutants with motility defects into three separate phenotypic classes called fla, che and mot.

The genetic designation fla was used for mutants that were aflagellate. Mapping and subsequent study of the fla mutants identified the structural components of the flagellum (102). Flagellar structure, deduced by a combination of mutant analysis, biochemistry and electron microscopy, was divided into general architectural domains: the basal body, the C-ring, the rod-hook, and the filament (Fig 1A). The basal body forms a platform in the plasma membrane and has a gear-like structure called the “C-ring” attached to its cytoplasmic facing. The rod extends from the basal body and transits the cell envelope like an axle, while the hook is a curved extracellular structure that functions as a universal joint. Finally, the filament is the most massive piece of the structure; it forms a long helical polymer that acts like a propeller. More than 20 structural proteins contribute to the assembly of the flagellum, and a loss-of-function mutation arising in any one of them is sufficient to abolish motility. Moreover, regulatory mutants that abolish expression of flagellar structural components are also members of the fla genetic class (102).

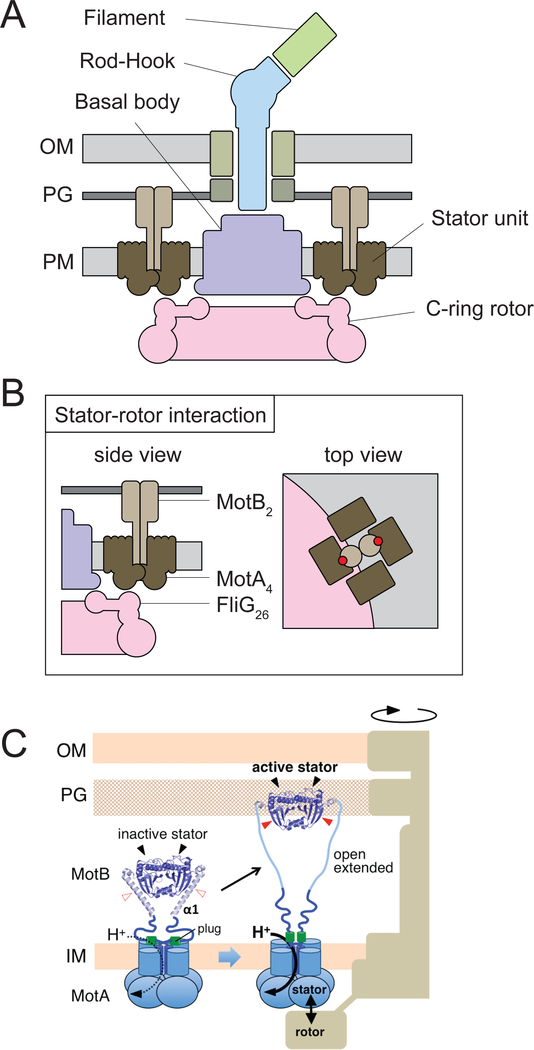

Figure legend 1: Models of flagellar structure and torque generation.

Panel A) Cross-section cartoon of the Gram-negative flagellum that highlights major architectural domains. OM – outer membrane, PG – peptidoglycan, PM – plasma membrane. The flagellar filament (colored green) is truncated as drawn; the entire filament is helical in structure and can extend for multiple cell lengths. The stator units (colored brown) are discrete complexes separate from the flagellar structure. They can range in number up to 11 surrounding an E. coli flagellum. Panel B) Stator-rotor interaction provides torque for rotation. The relative location of the protonatable Asp32 residue that serves as the conduit for proton motive force consumption is indicated in red based on reference 26. The stator complex sits atop the gear-like rotor made of FliG and likely generates force when MotA makes a piston-like conformational change. Panel C) Stator complexes change conformation upon interaction with the flagellum. Panel reprinted with permission from reference 71.

The genetic designation che was used for mutants that were motile in liquid but were defective in colonizing in soft agar plates (1,6). As a bacterial colony grows in soft agar, local nutrient consumption generates a chemical gradient, and chemotactic bacteria direct movement radially outward to create a large zone of colonization. Bacteria preferentially migrate up an attractant gradient by increasing the amount of time they spend “running” in straight lines relative to the time they spend reorienting by Brownian motion, or “tumbling” (14,101). Characterization of the che mutants lead to the discovery of molecule-specific chemoreceptors (MCPs) that are subject to sensory adaptation and a shared signal transduction system that interacts with the flagellum (15,38,57,63,116). The chemotaxis system works by regulating the time the flagellum rotates clockwise or counterclockwise, which in turn governs the duration of the running and tumbling behaviors, respectively (24,90,135,161).

The genetic designation mot was used for mutants that were proficient for flagellar synthesis but were apparently unable to generate force. Flagella generate force by rotation, a fact first demonstrated when cells were tethered by individual filaments; the cell body was observed to counter-rotate about the tether point (13,141). The torque that drives rotation is generated by consumption of the proton motive force (PMF), and flagellar rotation stops when the proton motive force collapses (16,91,103,129). Individual flagella may rotate at speeds of several hundred to over a thousand revolutions per second, and rotational speed can be tuned by varying the PMF voltage differential over the membrane (15,50,51,81,137). While the mechanism that generates rotation was unknown, mutants of the mot class abolished rotation, and it was concluded that the wild-type proteins were likely responsible for energy conversion. Cloning, complementation and sequencing indicated that the mot mutations map to two adjacent genes encoding the transmembrane proteins MotA and MotB (43,140,146).

The flagellar motor.

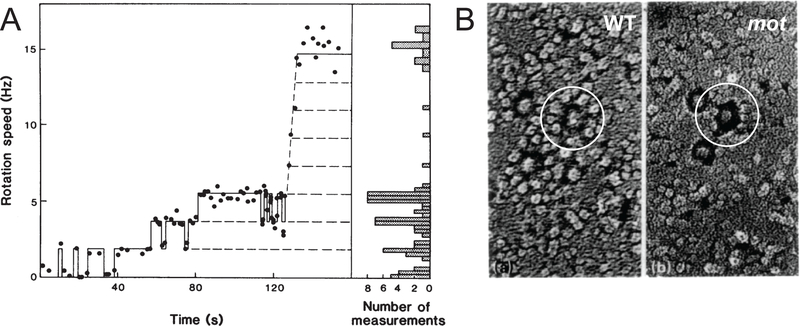

The central role of MotA and MotB in energy transduction was supported by a critical set of experiments called “motor resurrection” (18,20). In the resurrection experiment, cells were tethered by a single flagellum, and expression of the stator proteins was artificially induced. In the absence of inducer, cell bodies turned passively by Brownian motion, and active rotation of individual motors was restored following addition of inducer. Remarkably, the speed of flagellar rotation increased in a series of precise increments after induction (18,20) (Fig 2). Thus, it appeared that each complex of MotA and MotB provided a fixed amount of torque to the flagellum, that more than one complex could associate with the flagellum, and the total torque was dependent on the sum total of complexes associated (18,20). By dividing the maximum rotation rate by the interval size, as many as 11 torque generating units were predicted to provide power to the motor simultaneously (18,131). Individual MotA/MotB torque generating units were directly observed as particles by freeze fracture electron microscopy, and approximately 11 particles appeared to surround each flagellum (80) (Fig 2b).

Figure legend 2: Motor resurrection.

Panel A) A motor resurrection experiment reprinted with permission from reference 18. The X-axis is time following stator gene induction, the Y-axis is the rotation speed of a tethered cell, and the dots are instantaneous rotation speeds. Panel B) Freeze-fracture electron microscopy of membranes containing flagellar basal bodies and stator units, reprinted and modified with permission from reference 80. The left panel is a membrane from wild-type cells, and the right panel is a membrane from a mot mutant. Annotation and white circle added to figure. The circles surround a single flagellar basal body and either include the densities attributed to stator units (left) or emphasize their absence (right).

The mechanism of flagellar torque generation was modeled based on an electric motor. Electric motors have two components: a stator that remains stationary (the magnetic housing) and a rotor that spins within the magnetic field. Of the two motor components, MotA and MotB likely represent the stator because the flagellum itself was the part that rotated, and MotA and MotB (by mot definition) were not required for flagellar structure. Moreover, the ring of MotA/MotB particles that formed around the outside of the rotating flagellum was reminiscent of a stator housing (80). Finally, sequence analysis of MotB suggested it was probably immobilized as it contains a large extracellular domain for binding peptidoglycan (37). Peptidoglycan forms the wall around the bacterial cell, and binding of MotB would provide a stable anchor point from which force can be exerted (16). Thus, the complexes formed by MotA and MotB were considered to form the stator units of the motor.

MotA and MotB form membrane-associated complexes in a MotA4:MotB2 stoichiometric ratio (Fig 1b) (84). Each MotB is a single-pass transmembrane protein with a large extracellular domain, and the transmembrane helices pack together in the center of the stator complex as a dimer (27,37). MotA has four transmembrane segments, and a tetramer of MotA surrounds MotB (26,164). Complexes of the stator subunits likely form soon after they are inserted into the membrane, and they appear to be highly mobile until they interact with the flagellum (18, 160). When stators dock with the flagellum, a change in stator conformation occurs such that the C-terminal domain of MotB extends, binds to peptidoglycan, and locks the complex in place (Fig 1c) (85,86,108,160,169). The MotB conformational change has a second effect in that it also displaces an extracellular plug domain that prevents proton conductance (65). Once plug inhibition is relieved, protons flow through the stator units by way of a titratable aspartate residue (Asp32) within the transmembrane helix of each MotB subunit (166).

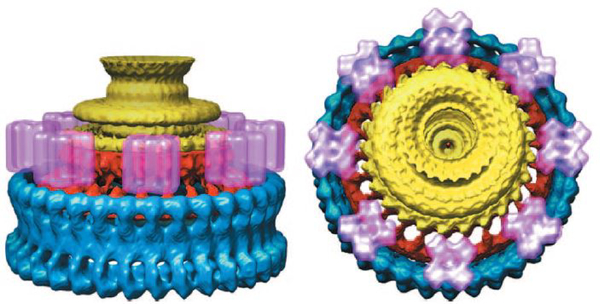

Proton flow through a stator unit creates torque by a causing a change in stator conformation. Limited proteolysis experiments indicated that a large cytoplasmic domain of MotA, called the “power loop,” changed conformation in a manner that was dependent on proton flow (83,164,152). The “power loop” contains charged residues that make electrostatic contacts with the flagellar C-ring protein FliG (99,107,163,165). Several dozen subunits, with a number that may vary among species, of FliG polymerize into a gear-like disk called the rotor that sits below the flagellar basal body and is necessary for rotation (Fig 3) (94,100,154). The number of subunits of FliG matches the number of steps in flagellar rotation, or the angle through which the flagellum turns with each power stroke (16, 145). Thus, as protons pass through the complex, MotA changes conformation and pushes on FliG to create torque in increments determined by the number of FliG subunits in the gear (28,111). Contact between the stators and the rotor has been recently observed by electron cryotomography, and the interaction is crucial for motility (10,168). Stator units that utilize sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium or rubidium can also power bacterial flagella, and their mechanism of force generation and regulation are beyond the scope of this review (67,68,119,153).

Figure legend 3: Ultrastructure of the flagellar basal body and C-ring.

A three-dimensional reconstruction of an electron micrograph of purified flagella. Densities attributed to the flagellar basal body (yellow), rotor (red), and the rest of the C-ring (blue) are indicated. Stator complexes (purple) were added to show their likely position, even though they were not included in the actual data set. Reprinted with permission from reference 154.

Contrary to the metaphor of a “stator”, stator units are not stationary; their interaction with the flagellum is dynamic. Stator dynamism was first observed in the original motor resurrection experiments in which rotation speed increased in increments but also decreased in the same increments (Fig 2a) (18,20). Thus, stators units were not only added to, but were also periodically lost from, flagellar rotors. Later, MotB fused to fluorescent reporters were seen to form foci at the center of rotation in tethered cells, and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments indicated that the turnover time of stator units was approximately 30 sec (or roughly 3000 revolutions) (93,132). Recruitment and retention of stators requires interaction with the rotor, and the number of stators associated with each rotor increases with the load applied (107,108, 97, 155, 156); the more stator units that associate with the motor, the more power that is imparted to the flagellum (32,97,112,155). Thus, an interaction between the stators and the rotor is essential for torque generation, and that interaction is inherently dynamic.

The mechanism of torque generation, including stator dynamism, sets the stage for understanding functional regulatory proteins. First, functional regulators should be considered conditional members of the mot genetic class, as they control rotation but not assembly of the flagellum. Second, functional regulators regulate torque at the flagellum by increasing, or decreasing, the interaction between the stators and the rotor; control of stator dynamism is only one potential mechanism. Just as the flagellar motor has been modeled according to an electric motor, functional regulators have been described using automotive analogies such as molecular clutches and brakes. Thus far, relatively few examples of such regulators have been reported, at least in part because of challenges in their identification.

Identifying and characterizing functional regulators of the flagellum.

One approach that has been successful in identifying functional inhibitors of the flagellum is to study biofilm formation. Mutations in regulatory proteins that constitutively de-repress expression of genes involved in biofilm formation also tend to render cells non-motile, and forward genetic approaches have identified functional inhibitors as disruptions in genes that restore motility (19,82). Alternatively, reverse genetic approaches have targeted proteins containing the “PilZ” domain that binds c-di-GMP, a secondary metabolite that accumulates during biofilm formation (3, 8, 35,126,131). Often, the motility phenotype of PilZ-domain proteins can only be observed under conditions under which the c-di-GMP levels are artificially elevated and the PilZ-domain containing protein is simultaneously overexpressed (8, 35, 82, 52, 126, 127). Thus, artificial conditions must be used for both forward and reverse genetic identification of functional regulators, consistent with their conditional regulation of motility.

Functional regulators, in their absence or upon their overproduction, confer a mot phenotype, and flagella remain present under conditions in which motility is impaired. Impaired motility may manifest itself as a reduced or abolished zone of colonization in motility plate assays. If active motility is inhibited, cells will jiggle erratically by Brownian motion in wet mount microscopy, and reductions in swimming speed can be measured with the help of image tracking software. The performance of individual motors can be measured by tethering cells to a surface by a single flagellum to generate counter-rotation of the cell body. Cells will only rotate if tethered by a single flagellum, however, and filaments of polyflagellate cells are often mechanically sheared to stubs to discourage immobilization due to multi-point tethering. Motion-tracking software may be used to measure the rate of rotation, and the torque produced by a single flagellar motor can be calculated by measuring the cell length, the cell width, and the radius of rotation (105,138). The behavior of tethered cells can distinguish whether a functional inhibitor behaves as a molecular clutch or brake.

Molecular clutch proteins decrease interaction between the stator and the rotor such that, when flagella are fully inhibited, cells rotate freely about the tether point by Brownian motion. Free rotation driven by Brownian motion can be identified by the mean squared angular displacement being consistent with rotational diffusion. It can be experimentally simulated by tethering cells mutated for the stator proteins (20). While random motion can cause cell bodies to turn clockwise and counterclockwise, tracking on the order of minutes should reveal instances of cells that make a full revolution. Evidence of full revolution is important to rule out the possibility that the motors are locked and that passive rotation is simply due to elastic compliance, or twist, of a locked flagellum (21, 22). Moreover, the rate of cell displacement should be constant over the period of revolution, suggesting a lack of torsion.

Molecular brake proteins increase interaction between the stator and the rotor such that, when flagella are fully inhibited, flagellar rotation is immobilized or locked. Demonstrating resistance to rotation is more challenging than demonstrating its absence. A locked flagellar state has been simulated in Gram-negative cells by treatment with the crosslinking agent glutaraldehyde, and under these conditions a cell will still rotate 3° over 90 sec around the tether point due to elastic compliance of the flagellum (22). A particularly elegant approach to demonstrate that flagella are locked involved observing tethered cells in a microfluidic device (121). When flow was introduced, cells that were “out-of-gear” and freely rotating aligned along their long axis with the direction of flow, whereas cells that were locked for rotation resisted conformity (121). Resistance to rotation can also be determined by attaching polystyrene beads to the flagellum and determining the force it takes to rotate the beads using an optical trap (17,121). Inhibition of motility by increased resistance might as also be indicated by a reduction in stator dynamism.

MOLECULAR CLUTCHES

EpsE in B. subtilis.

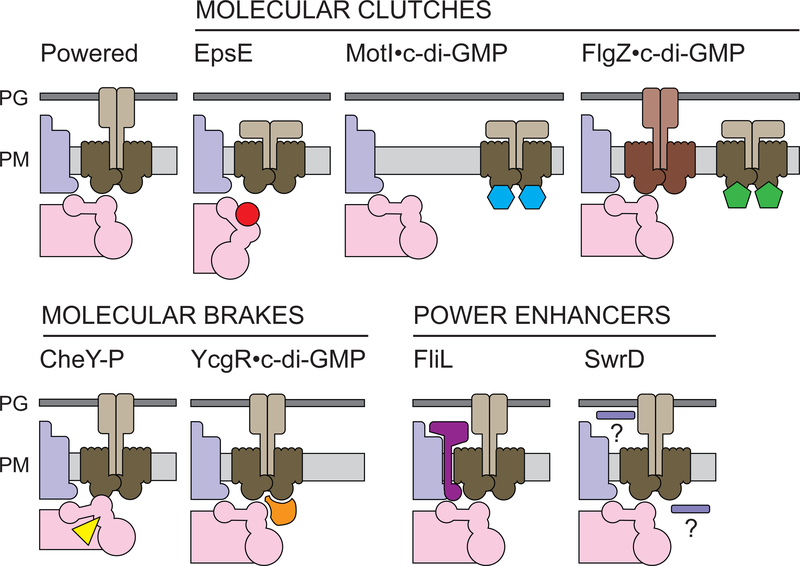

EpsE is a protein in Bacillus subtilis that inhibits flagellar rotation like a molecular clutch. Overexpression of EpsE is sufficient to inhibit motility, and spontaneous suppressor mutations that restore motility are rare missense mutations in the rotor protein, FliG (19). Fluorescent fusions of EpsE localize as multiple puncta that are stationary on the cell surface, and the puncta co-localize with flagellar basal bodies (19, 53, 61). Moreover, punctate localization of EpsE is abolished in strains carrying EpsE-resistant alleles of FliG, suggesting that the two proteins interact directly in vivo (19). Finally, flagellar tethering assays indicate that flagella inhibited by EpsE are not locked, and that such cells rotate by Brownian motion similar to mutants deleted for MotA and MotB (19, 29, 150). Thus, EpsE binds to FliG and disengages the rotor from the stators (Fig 4).

Figure legend 4:

Models for functional regulators of the bacterial flagellum. PG – peptidoglycan. PM – plasma membrane. Basal body (purple), rotor/C-ring (pink), stator units (brown), functional regulator (unique color). EpsE (B. subtilis, red) binds to the rotor and disconnects it from the stators. MotI bound to c-di-GMP (B. subtilis, blue) binds to the stator units and disconnects them from the rotor. FlgZ bound to c-di-GMP (P. aeruginosa, green) binds to one set of stators (MotCD) and disconnects them from the rotor while permitting another set (MotAB) to associate. Phosphorylated CheY (R. sphaeroides, yellow) interacts with the C-ring and increases rotor interaction with the stator units. YcgR bound to c-di-GMP (E. coli, orange) binds to stators units and the rotor simultaneously to reduce rotation speeds and bias rotation in the counterclockwise direction. FliL (magenta) increases torque likely by relieving inhibition of proton flow through the stator by the MotB plug domain. SwrD (B. subtilis, lavender) increases torque, perhaps by stabilizing stators at the rotor, but the mechanism and the location of SwrD are unknown.

EpsE is encoded by the fifth gene in a fifteen-gene operon dedicated to the synthesis of an extracellular polysaccharide necessary for formation of the biofilm matrix (25, 77). EpsE is homologous to the glycosyltransferase family of enzymes, and mutation of the active site abolishes EPS synthesis but not flagellar inhibition, suggesting that the latter is an alternative function (59). Consistent with bifunctionality, the activity as a flagellar clutch requires a group of residues outside of the glycosyltransferase active site, and the clutch and EPS-synthesis functions are genetically separable (59). While the mechanisms underpinning the motility-to-biofilm transition are poorly understood, the discovery of EpsE suggested that this seemingly complex change in physiology might, in some cases, be explained by a single bifunctional gene product. Evolutionarily, the contact residues on the flagellar rotor are less conserved than the contact residues on EpsE, suggesting that the flagellar rotor may have evolved to interact with a protein that was present during biofilm formation (59). If true, bioinformatic discovery of other clutch proteins may be difficult; the regulators may not resemble EpsE or any other protein associated with the flagellum.

Inhibition of flagellar rotation may be a common theme in the regulation of motility during biofilm formation, but if and why flagella would need to be inhibited during biofilm formation is unclear (59). Mutants defective in EpsE clutch activity, but not glycosyltransferase activity, form multicellular aggregates like the wild type, but cells writhe within the confines of the extracellular matrix (19). Thus, inhibition of motility may help stabilize early aggregate formation, and clutch defects when combined with extracellular matrix mutants may act synergistically to impair biofilm formation (59). Alternatively, inhibition of motility may be a mechanism to conserve energy once the biofilm has formed. Consistent with a long term benefit to inhibition of motility, a high frequency of cells isolated from biofilms of clutch-defective mutants were genetically non-motile, suggesting that there is strong selective pressure for loss of motility (59). It appears that clutch activity reduces selection pressure for mutations that eliminate motility in niches where there are regular transitions between motility and biofilm formation.

Questions remain about the mechanical properties of EpsE. If EpsE functions in a manner analogous to the clutch in a car, do protons still flow when the clutch is out (i.e., does the engine idle)? Unrestricted proton flow through flagellar stators has been shown to be detrimental to E. coli growth, a problem normally prevented by the plug domain of MotB (65). EpsE expression does not impair growth, perhaps indicating that proton flow stops, but if so, the mechanism is unknown; B. subtilis MotB does not appear to contain a “plug” domain homologous to that of E. coli. Furthermore, do stators dissociate when EpsE disengages the rotor? Stator dynamics have not yet been explored in B. subtilis as fusions of fluorescent proteins to MotA and MotB have been reported to be non-functional (150). Perhaps, consistent with stator dissociation and/or inhibition of proton flow, induction of EpsE phenocopies the pleiotropic effects associated with deletion of stator subunits (29,33). Finally, how many EpsE molecules are required to disengage a rotor, and what is the structure of the rotor when it is disengaged?

MotI in B. subtilis.

B. subtilis encodes a second molecular clutch protein called MotI. MotI (formerly YpfA, DgrA) is a PilZ-domain protein, and tethered cells inhibited by MotI rotate freely by Brownian motion without evidence of resistance (150). Spontaneous suppressor mutations that restore motility in the presence of inhibitory levels of MotI were very rare and found to target a single residue of MotA, two residues downstream of a critical force-generating residue in the MotA “power loop” (150, 33). Thus, MotI likely interacts with MotA at the mutated residue. The two proteins have also been shown to interact directly in bacterial two-hybrid assays (35). Moreover, fluorescent fusions indicated that MotI localizes as puncta at the membrane. The puncta were abolished in strains expressing mutations in the putative contact residue in MotA (150). Thus, MotI acts as a molecular clutch by interacting with stator units and separating them from the rotor (Fig 4).

In order to observe MotI-dependent inhibition of motility in B. subtilis, two levels of regulation must be bypassed. The first is production of c-di-GMP. MotI is only functional for motility inhibition when bound to c-di-GMP, and c-di-GMP levels are below the limit of detection during growth (52,150). Artificially high cellular levels of c-di-GMP occur when the major hydrolyzing phosphodiesterase PdeH is mutated, but motility is only slightly inhibited, albeit in a MotI-dependent manner (35,52). The second level of regulation is expression of the MotI protein. MotI only exhibits strong inhibition of motility when c-di-GMP levels are high and MotI is artificially over-expressed (35,52). The conditions under which MotI and c-di-GMP are both naturally elevated are unknown. While high levels of c-di-GMP are often correlated with the onset of biofilm formation in many bacteria, the correlation between the two in B. subtilis is unclear (35,52,9). Moreover, flagellar rotation in biofilms is already inhibited by EpsE, and whether c-di-GMP levels actually increase during B. subtilis biofilm formation is unknown. Thus, MotI acts as a molecular clutch on the flagellar stators, but how, when and why it does so is poorly understood.

The mechanism of MotI inhibition has been inferred from artificial over-expression and microscopy. When MotI is fully induced, flagellar rotation and motility is abolished, but reductions in the level of inducer result in an increase in swimming speeds (150). Gradual restoration of torque is somewhat reminiscent of the stator resurrection experiments, and thus MotI may interfere with stator dynamism. Consistent with an effect on dynamism, fluorescent MotI puncta appear and disappear in time when MotI was expressed at sub-inhibitory levels (150). It was inferred that puncta appear when MotI interacts with stators that are docked at the flagellum and disappear when MotI triggers dissociation of stators back into a membrane-bound pool. Moreover, fluorescent puncta of MotI were abolished at levels of induction that fully inhibit motility, suggesting that MotI also prevents association of MotA with the rotors. Thus, MotI appears to inhibit motility by separating stators from the rotor in a manner that depends on stator dynamism, resembling a model previously proposed for FlgZ in Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

FlgZ in Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

FlgZ is a PilZ-domain-containing protein in P. aeruginosa that inhibits swarming motility on solid surfaces but not swimming motility in liquid. P. aeruginosa flagella are powered by a dual stator system in which torque-generating complexes comprised of either MotA/MotB or MotC/MotD compete for interaction with the flagellum. Both types of stators are sufficient to power rotation for swimming in liquid environments, but only MotCD is sufficient for swarming (44,89,158). FlgZ antagonizes swarming by binding to MotC, and studies with MotC fluorescent fusions indicated that FlgZ localizes as puncta at the flagellar cell pole in a MotC-dependent manner (8,104,162). Moreover, inhibition of motility requires high levels of c-di-GMP, and under these conditions, formation of polar puncta by MotD was abolished (89). Thus, FlgZ inhibits swarming motility, but not swimming motility, by disengaging one set of stators (MotCD) in favor of another (MotAB) that provides less torque (Fig 4) (89).

The two stators not only compete to control flagellar rotation; they also have a complex effect on biofilm formation. For example, mutation of either motAB or motCD reduces or abolishes biofilm formation, respectively (89,104,158,157). Typically, motility and biofilm formation behave as opposite phenotypes, but, in this case, the stators are involved in promoting both processes in a complex manner. As an added complexity in the system, inhibition of swarming motility by FlgZ can be relieved by elimination of MotAB, but how and why swarming is restored when MotAB is absent and MotCD is inhibited by FlgZ remains to be determined (89).

Like B. subtilis, P. aeruginosa appears to encode multiple functional regulators of the flagellum. The GTPase FlhF promotes flagellar assembly but has a second, genetically separable function in promoting flagellar rotation (133). The mechanism by which FlhF controls flagellar rotation, and whether it is related to FlgZ or the control of the two stator system, is unknown.

FLAGELLAR BRAKES

CheY in Rhodobacter sphaeroides.

CheY is a protein in Rhodobacter sphaeroides that acts as a molecular brake to control chemotaxis. As most bacteria, R. sphaeroides biases a random walk up a chemical gradient by prolonging the duration of smooth swimming in response to increasing concentrations of attractant (69,122). Unlike E. coli, however, the single flagellum of R. sphaeroides rotates in only one direction (4). Thus, the flagellum rotates to propel bacteria forward in a “run” and stops rotating to allow Brownian motion to produce a “tumble” that changes cell orientation (5). Similarly, whereas phosphorylation of CheY regulates the frequency of clockwise rotation in E. coli, phosphorylation of CheY regulates the frequency of rotation arrest in R. sphaeroides (124). While the chemotaxis system of R. sphaeroides is also considerably more complex than that of E. coli, CheY-P still governs behavior by interacting directly with the flagellar rotor (123).

To determine how CheY-P causes the flagellum to stop rotating, cells were tethered by their flagella in a flow cell. Wild-type cells rotate and periodically stop, even in the presence of attractant (121). When attractant is flushed out of the flow cell, cells stop rotating for a prolonged period of time, and the cell bodies appear to be locked, as they do not conform to the direction of fluid flow (36, 70, 75, 110, 114, 144). Moreover, when an optical trap was used to impart force on the locked cell bodies, it was demonstrated that resistance was being applied flagellum to arrest rotation (121). Thus, CheY of R. sphaeroides acts a molecular brake that binds to the flagellar rotor, changes its conformation, and increases resistance with the stators to the point of locking flagellar rotation (Fig 4). Moreover, chemotaxis is mediated by rapid changes in motor behavior, CheY illustrates the near-instantaneous speed at which functional regulators can operate, and further demonstrates that inhibition can be rapidly reversible as cells punctuate running with tumbling.

YcgR in E. coli.

YcgR is a PilZ-domain-containing protein that was first identified as a motility inhibitor in a forward genetic suppressor screen. Cells mutated for the hns gene encoding the nucleoid structure protein H-NS were proficient for flagellar synthesis but exhibited a severe defect in motility (82). Genetic disruption of YcgR restored wild-type motile behavior to mutants lacking H-NS, suggesting that YcgR is an inhibitor of motility (82). Genetic analysis provided two other clues to YcgR function. First, overexpression of YhjH, a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase, restored motility to the hns mutant, suggesting that inhibition by YcgR requires c-di-GMP (82,142). YcgR was later shown to require binding to c-di-GMP to inhibit motility (3,131), and cells that accumulate c-di-GMP exhibit a YcgR-dependent reduction in swimming speed (23,118). Second, overexpression of MotA restored motility to the hns mutant despite the fact that the hns defect did not reduce MotA levels (82). Thus, YcgR inhibits flagellar function in a manner that depends on c-di-GMP and can be titrated by MotA.

YcgR has been proposed to inhibit motility by acting as a molecular brake that interacts with both the flagellar stator and the rotor. Stator contacts were implicated when forward genetic suppressor analysis isolated YcgR-resistant mutants in which residues in the cytoplasmic power loop of MotA were altered (23). Interactions between YcgR and the stators was further supported by Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements between fluorescent fusions to the two proteins (23). Rotor contacts were implicated by reverse genetic suppressor analysis, showing that some mutations in fliG could also increase motility in cells inhibited by YcgR (118). Interaction between YcgR and the rotor was further supported by pull-down and bacterial two-hybrid assays (130,131). Finally, YcgR fused to a fluorescent protein localizes as puncta at the membrane. These puncta co-localize with flagellar basal bodies, and formation of the puncta is at least partially dependent on the presence of both stator and rotor components (23,118). Thus, YcgR appears to bind flagellar rotors and stators simultaneously, perhaps bridging the two components to increase rotational resistance (Fig 4).

Whether or not YcgR increases rotational resistance is unclear. Its categorization as a brake depends primarily on the observations that YcgR-inhibition reduces swimming speed in liquid culture and increases the fraction of immobilized cells in tethering assays (23, 82,118). Reduction in swimming speed is not determinative, however, as reductions in speed have also been reported for clutch-like mechanisms (150). Moreover, if YcgR works by increasing resistance, an impaired flagellum might be excluded from the flagellar bundle and produce drag; even a single non-conforming flagellar filament has been shown to cause tumbling rather than simply reducing speed (159). Finally, most of the flagellar motors that are inhibited by YcgR exhibit powered rotation with a strong counterclockwise bias and a reduced frequency of switching (46, 56, 118). Thus, YcgR may primarily regulate the direction of flagellar rotation, and thus chemotaxis, reminiscent of the situation with CheY of R. sphaeroides, albeit by a different mechanism. If YcgR only regulates chemotaxis, however, it becomes difficult to explain how inhibition by YcgR can be suppressed by motA mutations or overexpression of MotA (23, 82). The true biological function of YcgR is unknown, but it is presumed to be related to biofilm formation, as c-di-GMP promotes cellulose synthesis (92, 142, 170). Correspondingly, YcgR has been reported to increase the frequency of cell attachment to surfaces (46).

POWER ENHANCERS

FliL.

FliL is a single-pass transmembrane protein that increases flagellar power. It is co-expressed with other flagellar components in a wide variety of bacteria (72, 128, 134). FliL was first characterized in C. crescentus as a protein of unknown function that, when mutated, abolished flagellar rotation (72). Subsequent mutation of fliL in other organisms indicated only modest reductions in swimming motility that nonetheless supported a role of FliL in flagellar rotation. For example, mutation of FliL in Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, Vibrio alginolyticus and Borrelia burgdorferi reduced the size of swim-zone colonization and decreased the flagellar rotation rate and torque (7, 109, 128, 117, 167). Thus, FliL increases flagellar power, but the degree to which it does so appears to be species and/or condition- specific. Perhaps supporting conditionality, a recent publication in E. coli disputes whether FliL is required for swarming motility, or indeed whether it affects power generation at all (34).

FliL appears to increase flagellar power by directly interacting with the flagellar basal body and stators. FliL transits the plasma membrane and co-purifies with the flagellar basal body (7,117,134). Cytologically, FliL-GFP fusions form discrete membrane-associated puncta and localize in a distribution reminiscent of flagellar basal bodies (98, 149, 167). Comparison of wild type and fliL mutants with electron cryotomography indicates that a FliL forms a density that sits between the flagellar stator complexes and the basal body (109). It is consistent with this location that bacterial two-hybrid analysis indicates that FliL contacts both stator and rotor components (117). Thus, while FliL is not required for flagellar assembly, it is nonetheless an integral part of the flagellar machinery, and its location supports its function as a power enhancer (Fig 4).

FliL appears to enhance flagellar power by controlling proton flux through the flagellar stators. Mutation of FliL in R. sphaeroides results in flagella that are unable to rotate, and spontaneous suppressor mutants that restore motility were found to be missense mutations that affect the “plug” region of MotB that restricts proton flow (149). Missense mutations in the MotB plug domain were later also found to improve the motility of fliL mutants in S. enterica and Vibrio alginolyticus (98, 117). As a further connection to ion flux, FliL localization depends on the plug domain of the stator and the presence of the corresponding ion motive force (98,167). Alternatively, FliL might control stator dynamism, but this seems unlikely, as mutation of FliL resulted in only a slight increase in stator dynamism, and FliL localization was approximately as dynamic as the stators themselves (98,117). Finally, overexpression of stator components failed to suppress motility defects of fliL mutants, indicating that FliL does not increase the probability of stator-rotor interaction (62, 117). The mechanism of FliL function is still being unraveled, but it appears to enhance ion flux once stator complexes have associated with the flagellum, perhaps like a throttle.

FliL is often related to swarming motility, and mutation of FliL has been reported to abolish swarming, but not swimming, in a number of organisms (7, 11, 12, 96). While the reduction in flagellar power likely contributes to the swarming defect, disruption of FliL has additional consequences. For example, flagella appeared to detach at high frequency from of a fliL mutant of S. enterica, and flagellar release was reduced in cells mutated for stator components (7). Flagellar filaments, however, were not found to be mechanically more susceptible to breakage in the absence of FliL (42), and thus filament release may be regulatory, as it is C. crescentus (2, 71). In Proteus mirabilis, fliL mutants have additional pleiotropic developmental defects; they appear to adopt a physiological state similar to swarming cells but nonetheless cannot move over surfaces (12, 41, 95). Thus, FliL likely promotes swarming by enhancing stator power generation, but this role is difficult to isolate from pleiotropic effects, which may or may not be dependent on the stator.

SwrD.

SwrD is a small, highly conserved protein that increases flagellar power. The gene that encodes it is linked to flagellar genes in the Gram-positive bacteria and spirochetes. Thus far, SwrD has only been studied in Bacillus subtilis, in which loss of SwrD abolishes swarming but not swimming (30). The swarming defect of a swrD mutant was not correlated with defects in flagellar assembly or a reduction in flagellar number. Analysis of tethered cells indicated that the flagellar motors of swrD mutants produce 6-fold less torque, an effect that is also reflected in a reduction in swimming speed (62). In B. subitilis, the swrD gene is located immediately upstream of, and co-expressed with, fliL. Complementation analysis indicated the swrD phenotype is not due to polarity, and fliL mutants exhibited only minor reductions in swarm expansion rate (62). Thus SwrD enhances flagellar power output in Gram-positive bacteria. Also, as seen with the effects of fliL mutations in Gram-negative bacteria, swarming motility requires high torque.

SwrD appears to enhance flagellar power by stabilizing MotA and MotB at the flagellum, such that, in its absence, MotA and MotB dissociate more frequently. The model is supported primarily by the fact that overexpression of MotA and MotB restored wild-type torque and swarming motility to the swrD mutant. It may be that higher numbers of stators per motor compensate for the decreased duration of interaction (62). If true, SwrD may function as a stator bracket or scaffold (10,32). However, whether SwrD increases motor power by associating with the rotor or the stators, and whether the presence of SwrD alters the dynamics of stator association, needs to be determined (Fig 4). Whatever the mechanism, the effect of SwrD seems distinct from that of FliL. Why SwrD and FliL are often encoded together, whether the two proteins synergize to enhance power, and how some bacteria function without SwrD remain unknown. Because the genes encoding SwrD and FliL are often adjacent to, and co-transcribed with, the genes encoding MotA and MotB, it may be that the four proteins constitute a larger module of torque generation (62).

Concluding remarks.

Functional regulators provide a mechanism to control motility without compromising the integrity of, or investment in, in flagellar assembly. At present, relatively few functional regulators have been identified, most likely because of the prevalent assumption that regulation of motility occurs primarily at the transcriptional level. There was no precedent or language that permitted people to deal with the concept of torque-level control. Thus, automotive terminology (clutch, brake, etc.) has been applied to describe molecular models of regulation and propose future experiments. The terminology, while useful and expedient, is ultimately likely to be inaccurate in detail and prone to misconception and misinterpretation when taken at face value. Nonetheless, the advantages of engine metaphors will likely out outweigh the disadvantages over time. The analogy of an electric motor to guide our understanding of the mechanics of flagellar rotation, and the use of the terms axle, universal joint, and propeller to describe the rod, hook and flagellar filaments, respectively, has a long and honorable tradition.

Functional regulators are advantageous in that they are simple, often operate on the basis of single protein-protein interaction, and act directly on a phenotype while preserving nanomachine investment. The strategy of controlling the molecular interaction between power systems and mechanical output may be a broad concept in bacterial regulation. Within flagellar motility, some bacteria are propelled by sodium-consuming stator units, while others exchange multiple kinds of stators within the same flagellum to provide differential amounts, or even different kinds, of power (44, 64 89, 119, 151, 158). Similar strategies may regulate nanomachines besides flagella that are powered by homologs of the flagellar stator proteins, including TonB-dependent siderophore transport (125,143), Tol-Pal-dependent outer-membrane synthesis (31, 54, 55), and gliding motility in Myxobacteria (49). Regulatory proteins have been suggested to operate directly on the competence apparatus for DNA uptake (87) and in a Type III secretion system (120). Molecular complexity, assembly investment, and trans-envelope integration may make motility machinery and uptake/export systems particularly susceptible to rapid control by functional regulators.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler J. 1966. Chemotaxis in bacteria. Science 153:708–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldridge P, Jenal U. 1999. Cell cycle-dependent degradation of a flagellar motor component requires a novel-type response regulator. Mol Microbiol 32:379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amikam D, Galperin MY. 2005. PilZ domain is part of the bacterial c-di-GMP binding protein. Bioinformatics 22:3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armitage JP, Macnab RM. 1987. Unidirectional, intermittent rotation of the flagellum of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol 169:514–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armitage JP, Pitta TP, Vigeant MAS, Packer HL, Ford RM. 1999. Transformations in flagellar structure of Rhodobacter sphaeroides and possible relationship to changes in swimming speed. J Bacteriol 181:4825–4833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong JB, Adler J, Dahl MM. 1967. Nonchemotactic mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 93:390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attmannspacher U, Scharf BE, Harshey RM. 2008. FliL is essential for swarming: motor rotation in absence of FliL fractures the flagellar rod in swarmer cells of Salmonella enterica. Mol Microbiol 68:328–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker AE, Diepold A, Kuchma SL, Scott JE, Ha DG, Orazi G, Armitage JP, O’Toole GA. 2016. PilZ domain protein FlgZ mediates cyclic di-GMP-dependent swarming motility control in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 198:1837–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bedrunka P, Graumann PL. 2017. Subcellular clustering of a putative c-di-GMP-dependent exopolysaccharide machinery affecting macro colony architecture in Bacillus subtilis. Environ Microbiol Rep 9:211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beeby M, Ribardo DA, Brennan CA, Ruby EG, Jensen GJ, Hendrixson DR. 2016. Diverse high-torque bacterial flagellar motors assemble wider stator rings using a conserved protein scaffold. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:E1917–1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belas R, Goldman M, Ashliman K. 1995. Genetic analysis of Proteus mirabilis mutants defective in swarmer cell elongation. J Bacteriol 177:823–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belas R, Suvanasuthi R. 2005. The ability of Proteus mirabilis to sense surfaces and regulate virulence gene expression involves FliL, a flagellar basal body protein. J Bacteriol 187:6789–6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berg HC, Anderson RA. 1973. Bacteria swim by rotating their flagellar filaments. Nature 245:380–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg HC, Brown DA. 1972. Chemotaxis in Escherichia coli analysed by three-dimensional tracking. Nature 239:500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg HC, Turner L. 1993. Torque generated by the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli. Biophys J 65:2201–2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berg HC. 1974. Dynamic properties of bacterial flagellar motors. Nature 249:77–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berry RM, Berg HC 1997. Absence of a barrier to backwards rotation of the bacterial flagellar motor demonstrated with optical tweezers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:14433–14437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blair DF, Berg HC. 1988. Restoration of torque in defective flagellar motors. Science 242:1678–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blair KM, Turner L, Winkelman JT, Berg HC, Kearns DB. 2008. A molecular clutch disables flagella in the Bacillus subtilis biofilm. Science 320:1636–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Block SM, Berg HC. 1984. Successive incorporation of force-generating units in the bacterial rotary motor. Nature 309:470–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Block SM, Blair DF, Berg HC. 1989. Compliance of bacterial flagella measured with optical tweezers. Nature 338:514–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Block SM, Blair DF, Berg HC. 1991. Compliance of bacterial polyhooks measured with optical tweezers. Cytometry 12:492–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boehm A, Kaiser M, Li H, Spangler C, Kasper CA, Ackermann M, Kaever V, Sourjik V, Roth V, Jenal U. 2010. Second messenger-mediated adjustment of bacterial swimming velocity. Cell 141:107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borkovich KA, Simon MI. 1990. The dynamics of protein phosphorylation in bacterial chemotaxis. Cell 63:1339–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Branda SS, González-Pastor JE, Ben-Yehuda S, Losick R, Kolter R. 2001. Fruiting body formation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:11621–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun TF, Al-Mawsawi LQ, Kojima S, Blair DF. 2004. Arrangement of core membrane segments in the MotA/MotB proton-channel complex of Escherichia coli. Biochem 43:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braun TF, Blair DF. 2001. Targeted disulfide cross-linking of the MotB protein of Escherichia coli: evidence for two H+ channels in the stator complex. Biochem 40:13051–13059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun TF, Poulson S, Gully JB, Empey JC, Van Way S, Putnam A, Blair DF. 1999. Function of proline residues of MotA in torque generation by the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 181:3542–3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cairns LS, Marlow VL, Bissett E, Ostrowski A, Stanley-Wall NR. 2013. A mechanical signal transmitted by the flagellum controls signaling in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 90:6–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calvo RA, Kearns DB. 2015. FlgM is secreted by the flagellar export apparatus in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 197:81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cascales E, Lloubès R, Sturgis JN. 2001. The TolQ-TolR proteins energize TolA and share homologies with the flagellar motor proteins MotA-MotB. Mol Microbiol 42:795–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaban B, Coleman I, Beeby M. 2018. Evolution of higher torque in Campylobacter-type bacterial flagellar motors. Sci Rep 8:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan JM, Guttenplan SB, Kearns DB. 2014. Defects in the flagellar motor increase synthesis of poly-γ-glutamate in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 196:740–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chawla R, Ford KM, Lele PP. 2017. Torque, but not FliL, regulates mechanosensitive flagellar motor function. Sci Rep 7:5565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y, Chai Y, Guo JH, Losick R. 2012. Evidence for cyclic di-GMP-mediated signaling in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 194:5080–5090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chevance FFV, Hughes KT. 2008. Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:455–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chun SY, Parkinson JS. 1988. Bacterial motility: membrane topology of the Escherichia coli MotB protein. Science 239:276–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collins ALT, Stocker BAD. 1976. Salmonella typhimurium mutants generally defective in chemotaxis. J Bacteriol 128:754–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colquhoun DB, Kirkpartrick J. 1932. The isolation of motile organisms from apparently non-motile cultures of B. typhosus, B. proteus, B. pestis, B. melitensis, etc et al. J Pathol Bacteriol 35:367–371. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cummings LA, Wilkerson WD, Bergsbaken T, Cookson BT. 2006. In vivo, fliC expression by Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium is heterogeneous, regulated by ClpX, and anatomically restricted. Mol Microbiol 61:795–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cusick K, Lee Y-Y, Youchak B, Belas R. 2012. Perturbation of FliL interferes with Proteus mirabilis swarmer cell gene expression and differentiation. J Bacteriol 194:437–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Darnton NC, Berg HC. 2008. Bacterial flagella are firmly anchored. J Bacteriol 190:8223–8224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dean GE, Macnab RM, Stader J, Matsumura P, Burks C. 1984. Gene sequence and predicted amino acid sequence of the MotA protein, a membrane-associated protein required for flagellar rotation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 159:991–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doyle TB, Hawkins AC, McCarter LL. 2004. The complex flagellar torque generator of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 186:6341–6350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Enomoto M. 1966. Genetic studies of paralyzed in Salmonella. I. Genetic fine structure of the mot loci in Salmonella typhimurium. Genetics 54:715–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fang X, Gomelsky M. 2010. A post-translational, c-di-GMP-dependent mechanism regulating flagellar motility. Mol Microbiol 76:1295–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flemming H-C, Wingender J, Szewzyk U, Steinberg P, Rice SA, Kjelleber S. 2016. Biofilms: an emergent form of bacterial life. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:563–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friewer FI, Leifson E. 1952. Non-motile flagellated variants of Salmonella typhimurium. J Pathol Bacteriol 64:223–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fu G, Bandaria JN, Le Gall AV, Fan X, Yildiz A, Mignot T, Zusman DR, Nan B. 2018. MotAB-like machinery drives the movement of MreB filaments during bacterial gliding motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:2484–2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fung DC, Berg HC. 1995. Powering the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli with an external voltage source. Nature 375:809–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gabel CV, Berg HC. 2003. The speed of the flagellar rotary motor of Escherichia coli varies linearly with proton motive force. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:8748–8751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao X, Mukherjee S, Matthews PM, Hammad LA, Kearns DB, Dann CE 3rd. 2013. Functional characterization of core components of the Bacillus subtilis cyclic-di-GMP signaling pathway. J Bacteriol 195:4782–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garner EC, Bernard R, Wang W, Zhuang X, Rudner DZ, Mitchison T. 2011. Coupled circumferential motions of the cell wall synthesis machinery and MreB filaments in B. subtilis. Science 333:222–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gerding MA, Ogata Y, Pecora ND, Niki H, de Boer PAJ. 2007. The trans-envelope Tol-Pal complex is part of the cell division machinery and required for proper outer-membrane invagination during cell constriction in E. coli. Mol Microbiol 63:1008–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Germon P, Ray M-C, Vianney A, Lazzaroni JC. 2001. Energy-dependent conformational change in the TolA protein of Escherichia coli involves its N-terminal domain, TolQ, and TolR. J Bacteriol 183:4110–4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Girgis HS, Liu Y, Ryu WS, Tavazoie S. 2007. A comprehensive genetic characterization of bacterial motility. PLoS Genet 3:e514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goy MF, Springer MS, Adler J. 1978. Failure of sensory adaptation in bacterial mutants that are defective in a protein methylation reaction. Cell 15:1231–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grimbergen AJ, Siebring J, Solopova A, Kuipers OP. 2015. Microbial bet-hedging: the power of being different. Curr Opin Microbiol 25:67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guttenplan SB, Blair KM, Kearns DB. 2010. The EpsE flagellar clutch is bifunctional and synergizes with EPS biosynthesis to promote Bacillus subtilis biofilm formation. PLoS Genet 6:e1001243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guttenplan SB, Kearns DB. 2013. Regulation of flagellar motility during biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol Rev 37:849–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guttenplan SB, Shaw S, Kearns DB. 2013. The cell biology of peritrichous flagella in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 87:211–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hall AN, Subramanian S, Oshiro RT, Canzoneri AK, Kearns DB. 2018. SwrD (YlzI) promotes swarming in Bacillus subtilis by increasing power to the flagellar motor. J Bacteriol 200:e00529–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hazelbauer GL, Mesibov RE, Adler J. 1969. Escherichia coli mutants defective in chemotaxis toward specific chemicals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 64:1300–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hirota N, Imae Y. 1983. Na+-driven flagellar motors of an alkalophilic Bacillus strain. J Biol Chem 258:10577–10581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hosking ER, Vogt C, Bakker EP, Manson MD. 2006. The Escherichia coli MotAB proton channel unplugged. J Mol Biol 364:921–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iino T, Enomoto M. 1966. Genetical studies of non-flagellate mutants of Salmonella. J Gen Microbiol 43:315–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ito M, Hicks DB, Henkin TM, Guffanti AA, Powers BD, Zvi L, Uematsu K, Krulwich TA. 2004. MotPS is the stator-force generator for motility of alkaliphilic Bacillus, and its homologue is a second functional Mot in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 53:1035–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Imazawa R, Takahashi Y, Aoki W, Sano M, Ito M. 2016. A novel type bacterial flagellar motor that can use divalent cations as a coupling ion. Sci Rep 6:19773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ingham CJ, Armitage JP. 1987. Involvement of transport in Rhodobacter sphaeroides chemotaxis. J Bacteriol 169:5801–5807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jarrell KF, McBride MJ. 2008. The surprisingly diverse was that prokaryotes move. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:466–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jenal U, Shapiro L. 1996. Cell cycle-controlled proteolysis of a flagellar motor protein that is asymmetrically distributed in the Caulobacter predivisional cell. EMBO J 15:2393–2406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jenal U, White J, Shapiro L. 1994. Caulobacter flagellar function, but not assembly, requires FliL, a non-polarly localized membrane protein present in all cell types. J Mol Biol 243:227–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Joys TM, Frankel RW. 1967. Genetic control of flagellation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 94:32–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kanbe M, Shibata S, Umino Y, Jenal U, Aizawa S-I. 2005. Protease susceptibility of the Caulobacter crescentus flagellar hook-basal body: a possible mechanism of flagellar ejection during cell differentiation. Microbiol 151:433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karlinsey JE, Tanaka S, Bettenworth V, Yamaguchi S, Boos W, Aizawa S-I, Hughes KT. 2000. Completion of the hook-basal body complex of the Salmonella typhimurium flagellum is coupled to FlgM secretion and fliC transcription. Mol Microbiol 37:1220–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaufmann F. 1939. Die serologische Salmonella-diagnose. Acta Path Microbiol Scand 16:278–302. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kearns DB, Chu F, Branda SS, Kolter R, Losick R. 2005. A master regulator for biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 55:739–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kearns DB, Losick R. 2005. Cell population heterogeneity during growth of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev 19:3083–3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kearns DB. 2010. A field guide to bacterial swarming motility. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:634–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Khan S, Dapice M, Reese TS. 1988. Effects of mot gene expression on the structure of the flagellar motor. J Mol Biol 202:575–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Khan S, Macnab RM. 1980. Proton chemical potential, proton electrical potential and bacterial motility. J Mol Biol 138:599–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ko M, Park C. 2000. Two novel flagellar components and H-NS are involved in the motor function of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 303:371–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kojima S, Blair DF. 2001. Conformational change in the stator of the bacterial flagellar motor. Biochem 40:13041–13050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kojima S, Blair DF. 2004. Solubilization and purification of the MotA/MotB complex of Escherichia coli. Biochem 43:26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kojima S, Imada K, Sakuma M, Sudo Y, Kojima C, Minamino T, Homma M, Namba K. 2009. Stator assembly and activation mechanism of the flagellar motor by the periplasmic region of MotB. Mol Microbiol 73:710–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kojima S, Takao M, Almira G, Kawahara I, Sakuma M, Homma M, Kojima C, Imada K. 2018. The helix rearrangement in the periplasmic domain of the flagellar stator B subunit activates peptidoglycan binding and ion influx. Structure 26:590–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Konkol MA, Blair KM, Kearns DB. 2013. Plasmid-encoded ComI inhibits competence in the ancestral 3610 strain of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 195:4085–4093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Koo H, Allan RN, Howlin RP, Stoodley P, Hall-Stoodley L. 2017. Targeting microbial biofilms: current and prospective therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol 15:740–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kuchma SL, Delalez NJ, Filkins LM, Snavely EA, Armitage JP, O’Toole GA. 2015. Cyclic di-GMP-mediated repression of swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 requires the MotAB stator. J Bacteriol 197:420–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Larsen SH, Adler J, Gargus J, Hogg RW. 1974. Chemomechanical coupling without ATP: the source of energy for motility and chemotaxis in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 71:1239–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Larsen SH, Reader RW, Kort EN Tso W-W, Adler J. 1974. Change in direction of flagellar rotation is the basis of the chemotactic response in Escherichia coli. Nature 249:74–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Le Guyon S, Simm R, Rehn M, Römling U. 2015. Dissecting the cyclic diguanylate monophosphate signaling network regulating motility in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Environ Microbiol 17:1310–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Leake MC, Chandler JH, Wadhams GH, Bai F, Berry RM, Armitage JP. 2006. Stoichiometry and turnover in single, functioning membrane protein complexes. Nature 443:355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lee KL, Ginsberg MA, Crovace C, Donohoe M, Stock D. 2010. Structure of the torque ring of the flagellar motor and the molecular basis for rotational switching. Nature 466:996–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lee Y-Y, Belas R. 2015. Loss of FliL alters Proteus mirabilis surface sensing and temperature-dependent swarming. J Bacteriol 197:159–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lee Y-Y, Patellis J, Belas R. 2013. Activity of Proteus mirabilis FliL is viscosity dependent and requires extragenic DNA. J Bacteriol 195:823–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lele PP, Hosu BG, Berg HC. 2013. Dynamics of mechanosensing in the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:11839–11844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lin T-S, Zhu S, Kojima S, Homma M, Lo C-J. 2018. FliL association with flagella stator in the sodium-driven Vibrio motor characterized by the fluorescent microscopy. Sci Rep 8:11172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lloyd SA, Blair DF. 1997. Charged residues of the rotor protein FliG essential for torque generation in the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 266:733–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lowder BJ, Duyvesteyn MD, Blair DF. 2005. FliG subunit arrangement in the flagellar rotor probed by targeted cross-linking. J Bacteriol 187:5640–5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Macnab RM, Koshland DE Jr. 1972. The gradient-sensing mechanism in bacterial chemotaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 69:2509–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Macnab RM. 1992. Genetics and biogenesis of bacterial flagella. Annu Rev Genet 26:131–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Manson MD, Tedesco P, Berg HC, Harold FM, van der Drift C. 1977. A protonmotive force drives bacterial flagella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 74:3060–3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Martínez-Granero F, Navazo A, Barahona E, Redondo-Nieto M, González de Heredia E, Baena I, Martín-Martín I, Rivilla R, Martín M. 2014. Identification of flgZ as a flagellar gene encoding a PilZ domain protein that regulates swimming motility and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas. PLoS One 9:e87608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Meister M, Berg HC. 1987. The stall torque of the bacterial flagellar motor. Biophys J 52:413–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Meynell EW. 1961. A phage, ϕχ, which attacks motile bacteria. J Gen Microbiol 25:253–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Morimoto YV, Nakamura S, Hiraoka KD, Namba K, Minamino T. 2013. Distinct roles of highly conserved charged residues at the MotA-FliG interface in bacterial flagellar motor rotation. J Bacteriol 195:474–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Morimoto YV, Nakamura S, Kami-ike N, Namba K, Minamino T. 2010. Charged residues in the cytoplasmic loop of MotA are required for stator assembly into the bacterial flagellar motor. Mol Microbiol 78:1117–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Motaleb MA, Pitzer JE, Sultan SZ, Liu J. 2011. A novel gene inactivation system reveals altered periplasmic flagellar orientation in a Borrelia burgdorferi fliL mutant. J Bacteriol 193:3324–3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mukherjee S, Kearns DB. 2014. The structure and regulation of flagella in Bacillus subtilis. Ann Rev Genet 48:319–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nishihara Y, Kitao A. 2015. Gate-controlled proton diffusion and protonation-induced ratchet motion in the stator of the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:7737–7742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nord AL, Sowa Y, Steel BC, L C-J, Berry RM. 2017. Speed of the bacterial flagellar motor near zero load depends on the number of stator units. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:11603–11608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Norman TM, Lord ND, Paulsson J, Losick R. 2013. Memory and modularity in cell-fate decision making. Nature 503:481–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Packer HL, Armitage JP. 1994. The chemokinetic and chemotactic behavior of Rhodobacter sphaeroides: two independent responses. J Bacteriol 176:206–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Parkinson JS, Revello PT. 1978. Sensory adaptation mutants of E. coli. Cell 15:1221–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Parkinson JS. 1974. Data processing by the chemotaxis machinery of Escherichia coli. Nature 252:317–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Patridge JD, Nieto V, Harshey RM. 2015. A new player at the flagellar motor: FliL controls both motor output and bias. mBio 6:e02367–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Paul K, Nieto V, Carlquist WC, Blair DF, Harshey RM. 2010. The c-di-GMP binding protein YcgR controls flagellar motor direction and speed to affect chemotaxis by a “backstop brake” mechanism. Mol Cell 38:128–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Paulick A, Koerdt A, Lassak J, Huntley S, Wilms I, Narberhaus F, Thormann KM. 2009. Two different stator systems drive a single polar flagellum in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Mol Microbiol 71:836–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Phillips AM, Calvo RA, Kearns DB. 2015. Functional activation of the flagellar type III secretion apparatus. PLoS Genet 11:e1005443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pilizota T, Brown MT, Leake MC, Branch RW, Berry RM, Armitage JP. 2009. A molecular brake, not a clutch, stops the Rhodobacter sphaeroides flagellar motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 106:11582–11587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Poole PS, Armitage JP. 1988. Motility response of Rhodobacter sphaeroides to chemotactic stimulation. J Bacteriol 170:5673–5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Porter SL, Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. 2011. Signal processing in complex chemotaxis pathways. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:153–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Porter SL, Wadhams GH, Martin AC, Byles ED, Lancaster DE, Armitage JP. 2006. The CheYs of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Biol Chem 281:32694–32704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Postle K, Larsen RA. 2007. TonB-dependent energy transduction between outer and cytoplasmic membranes. Biometals 20:453–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Pratt JT, Tamayo R, Tischler AD, Camilli A. 2007. PilZ domain proteins bind cyclic diguanylate and regulate diverse processes in Vibrio cholerae. J Biol Chem 282:12860–12870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pultz IS, Christen M, Kulasekara HD, Kennard A, Kulasekara B, Miller SI. 2012. The response threshold of Salmonella PilZ domain proteins is determined by their binding affinities for c-di-GMP. Mol Microbiol 86:1424–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Raha M, Sockett H, Macnab RM. 1994. Characterization of the fliL gene in the flagellar regulon of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol 176:2308–2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ravid S, Eisenbach M. 1984. Minimal requirements for rotation of bacterial flagella. J Bacteriol 158:1208–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Reid SW, Leake MC, Chandler JH, Lo C-J, Armitage JP, Berry RM. 2006. The maximum number of torque-generating units in the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli is at least 11. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:8066–8071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ryjenkov DA, Simm R, Römling U, Gomelsky M. 2006. The PilZ domain is a receptor for the second messenger c-di-GMP: the PilZ domain protein YcgR controls motility in enterobacteria. J Biol Chem 281:30310–30314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ryu WS, Berry RM, Berg HC. 2000. Torque-generating units of the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli have a high duty ratio. Nature 403:444–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Schneiderberend M, Abdurachim K, Murray TS, Kazmierczak BI. 2013. The GTPase activity of FlhF is dispensible for flagellar localization but not motility, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 195:1051–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Schoenhals GJ, Macnab RM. 1999. FliL is a membrane-associated component of the flagellar basal body of Salmonella. Microbiol 145:1769–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Segall JE, Ishihara A, Berg HC. 1985. Chemotactic signaling in filamentous cells of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 161:51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sertic V, Goulgakov NA. 1936. Bactériophages specifique pour des varietes bactériennes flagellées. C R Soc Biol Paris 123:887–888. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Shioi J-I, Matsuura S, Imae Y. 1980. Quantitative measurements of proton motive force and motility in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 144:891–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Shrivastava A, Lele PP, Berg HC. 2015. A rotary motor drives Flavobacterium gliding. Curr Biol 25:338–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Shrivastava D, Hsieh M-L, Khataokar A, Neidtich MB, Waters CM. 2013. Cylcic di-GMP inhibits Vibrio cholerae motility by repressing induction of transcription and inducing extracellular polysaccharide production. Mol Microbiol 90:1262–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Silverman M, Matsumura P, Simon M. 1976. The identification of the mot gene product with Escherichia coli-lambda hybrids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 73:3126–3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Silverman M, Simon M. 1974. Flagellar rotation and the mechanism of bacterial motility. Nature 249:73–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Simm R, Morr M, Kader A, Nimtz M, Römling U. 2004. GGDEF and EAL domains inversely regulate cyclic di-GMP levels and transition from sessility to motility. Mol Microbiol 53:1123–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Skare JT, Postle K. 1991. Evidence for a TonB-dependent energy transduction complex in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 5:2883–2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Smith DR, Chapman MR. 2010. Economical evolution: microbes reduce the synthetic cost of extracellular proteins. mBio 3:e00131–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Sowa Y, Rowe AD, Leake MC, Yakushi T, Homma M, Ishijima A, Berry RM. 2005. Direct observation of steps in rotation of the bacterial flagellar motor. Nature 437:916–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Stader J, Matsumura P, Vacante D, Dean GE, Macnab RM. 1986. Nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli motB gene and site-limited incorporation of its product into the cytoplasmic membrane. J Bacteriol 166:244–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Stewart MK, Cookson BT. 2014. Mutually repressing repressor functions and multi-layered cellular heterogeneity regulate bistable Salmonella fliC census. Mol Microbiol 94:1272–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Stocker BAD, Zinder ND, Lederberg J. 1953. Transduction of flagellar characters in Salmonella. J Gen Microbiol 9:410–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Suatse-Olmos F, Domenzain C, Mireles-Rodríguez JC, Poggio S, Osorio A, Dreyfus, Camarena L. 2010. The flagellar protein FliL is essential for swimming in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol 192:6230–6239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Subramanian S, Gao X, Dann CE III, Kearns DB. 2018. MotI (DgrA) acts as a molecular clutch on the flagellar stator protein MotA in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:13537–13542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Takekawa N, Nishiyama M, Kaneseki T, Kanai T, Atomi H, Kojima S, Homma M. 2015. Sodium-driven energy conversion for flagellar rotation of the earliest divergent hyperthermophilic bacterium. Sci Rep 5:12711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Takekawa N, Terahara N, Kato T, Gohara M, Mayanagi K, Hijikata A, Onoue Y, Kojima S, Shirai T, Namba K, Homma M. 2016. The tetrameric MotA complex as the core of the flagellar motor stator from hyperthermophilic bacterium. Sci Rep 6:31526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]