Abstract

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus emerged in the US is known to suppress the type I interferons response during infection. In the present study using porcine epithelial cells, we showed that PEDV inhibited both NF-κB and proinflammatory cytokines. PEDV blocked the p65 activation in infected cells and suppressed the PRD II-mediated NF-κB activity. Of the total of 22 viral proteins, nine proteins were identified as NF-κB antagonists, and nsp1 was the most potent suppressor of proinflammatory cytokines. Nsp1 interfered the phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα, and thus blocked the p65 activation. Mutational studies demonstrated the essential requirements of the conserved residues of nsp1 for NF-κB suppression. Our study showed that PEDV inhibited NF-κB activity and nsp1 was a potent NF-κB antagonist for suppression of both IFN and early production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Keywords: PEDV, Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, Coronavirus, Immune evasion, Interferon suppression, NF-κB, Nsp1, Interferon signaling, Proinflammatory cytokines

Highlights

-

•

PEDV inhibits type I IFNs and NF-κB-mediated pro-inflammatory cytokines.

-

•

PEDV blocks p65 nuclear translocation in virus-infected cells.

-

•

Among 22 viral proteins, nsp1, nsp3, nsp5, nsp7, nsp14, nsp15, nsp16, ORF3, and E are NF-κB antagonists.

-

•

Nsp1 suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines and p65 activation by blocking IκBα phosphorylation.

-

•

The conserved residues of nsp1 are crucial for NF-κB suppression.

1. Introduction

Porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) is an acute and highly contagious enteric disease characterized by severe enteritis, vomiting, watery diarrhea and a high mortality rate in neonatal piglets (Debouck and Pensaert, 1980, Junwei et al., 2006, Song and Park, 2012, Sun et al., 2012). The current virulent PED outbreaks started in China in the late 2010 and quickly spread to other countries in Asia, causing significant economic losses in the swine industry (Sun et al., 2015, Sun et al., 2012). PED emerged in the US for the first time in April 2013 and resulted in more than 8 million deaths of pig in less than 8 months of the first outbreak. (Chen et al., 2014, Marthaler et al., 2013, Mole, 2013, Stevenson et al., 2013).

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) is a coronavirus belonging to the genus Alphacoronavirus of the Coronaviridae family (http://ictvonline.org/virustaxonomy.asp). The PEDV genome is a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA of ∼28 kb in length with a 5’-cap and a 3’-polyadenylated tail. It encodes two polyproteins (pp1a and pp1a/b), an accessory protein (ORF3), and four structural proteins (spike S, envelope E, membrane M, and nucleocapsid N, envelope E, membrane M, and nucleocapsid N) (Duarte et al., 1993, Kocherhans et al., 2001). Pp1a and pp1a/b are processed to 16 nonstructural proteins (nsps) by the proteinase activity of nsp3 and nsp5. Among nsps, nsp1 is the most N-terminal and first cleavage product (Ziebuhr, 2005).

Virus-infected cells react quickly to invading viruses by producing type I interferons (IFN-α/β) and establish an antiviral state, which provides a first line of defense against viral infection. The viral nucleic acids are sensed by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) such as transmembrane toll-like receptors (TLRs) and cytoplasmic RNA/DNA sensors (Kawai and Akira, 2011). This recognition leads to the activation of cytosolic kinases which promotes the activation of IFN regulator factor 3 (IRF3), IRF7, and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), and their subsequent translocation to the nucleus allows them to bind to their respective positive regulatory domain (PRD) for production of type I IFNs (Honda et al., 2006). The activated IRF3/IRF7 bind to the PRD I/III sequences and induces the expression of type I IFN genes (Hermant and Michiels, 2014). For NF-κB, the activated form is translocated to the nucleus and triggers IFN-β expression by binding to the PRD II element (Escalante et al., 2002). Type I IFNs are then secreted and bind to their receptors on virus-infected cells as well as uninfected neighbor cells, and activate the JAK/STAT pathway to produce hundreds of interferon-stimulating genes (ISGs) to establish an antiviral state (Stark and Darnell, 2012).

In unstimulated cells, NF-κB (p50/p65 heterocomplex) remains associated with the inhibitory protein IκBα masking the nuclear localization signal (NLS) of NF-κB and sequesters the NF-κB·IκBα complex in the cytoplasm. The NF-κB signaling pathway may be activated by intracellular products such as IL-1 and TNFα that are induced by viral infections or extracellular stress such as phorbol esters and UV (Campbell and Perkins, 2006, Ghosh et al., 1998). Activated NF-κB then induces the production of proinflammatory cytokines and regulates a variety of gene expressions, which affects cell survival, differentiation, immunity, and proliferation (Hayden and Ghosh, 2012). TNFα binds to its receptor and initiates a signaling cascade culminating the activation of IκB kinase complex (IKKα/β). The IKK complex then phosphorylates IκBα to mediate ubiquitination and degradation and releases NF-κB. Released NF-κB is transported to the nucleus, where it binds to target sequences and initiates transcriptions (Hayden and Ghosh, 2012, Napetschnig and Wu, 2013, Verstrepen et al., 2008).

To circumvent such responses of the cell, many viruses have developed various strategies to evade the host innate immunity. We have previously reported that PEDV suppresses the type I interferon and ISGs productions and have identified nsp1 as the potent viral IFN antagonist (Zhang et al., 2016). PEDV nsp1 causes the CREB-binding protein (CBP) degradation in the nucleus and antagonizes the IFN production and signaling (Zhang et al., 2016). Despite the importance of NF-κB during infection, regulation of NF-κB by PEDV is poorly understood. The PEDV N protein blocks the NF-κB activity and inhibits the IFN-β production and IFN stimulating genes (ISGs) expression (Ding et al., 2014). PEDV nsp5 is a 3C-like proteinase and cleaves the NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO) (Wang et al., 2015), suggesting that PEDV has the ability for NF-κB suppression. Although PEDV has been shown to activate NF-κB at a late stage of infection (Cao et al., 2015b, Xing et al., 2013), it is unclear whether it is time-dependent and TNFα-mediated. In the present study, we show the inhibition of NF-κB, and temporal regulation of type I IFNs and pro-inflammatory cytokines by PEDV. Among PEDV proteins, nsp1, nsp3, nsp5, nsp7, nsp14, nsp15, nsp16, ORF3, and E were identified as NF-κB antagonists with nsp1 being the most potent. We also showed that the conserved residues of nsp1 were crucial for NF-κB suppression. The nsp1-mediated NF-κB modulation may facilitate the replication and pathogenesis of PEDV.

2. Results

2.1. Inhibition of type I IFNs production by PEDV in LLC-PK1 cells

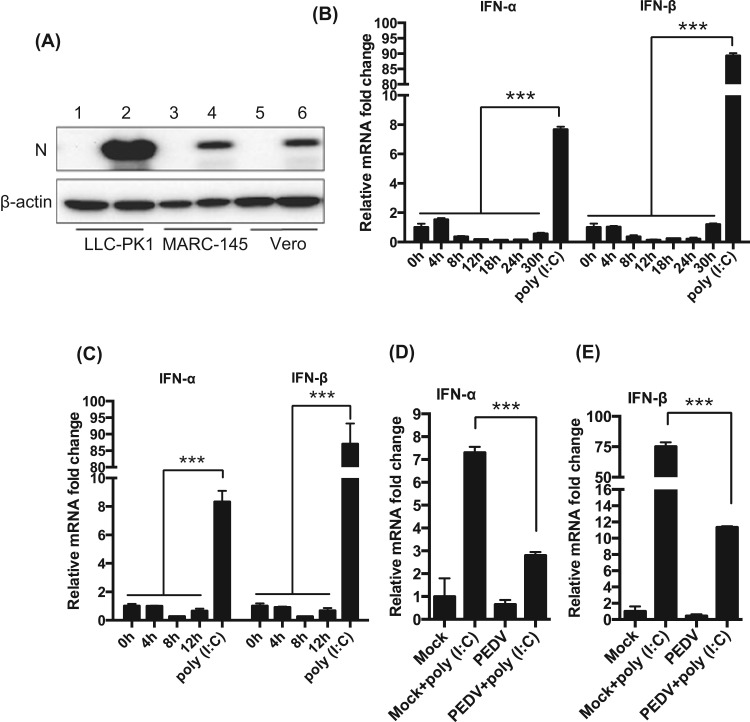

The primary target cells for PEDV in pigs are villous epithelial cells of the intestinal tract (Debouck and Pensaert, 1980, Lee et al., 2000, Sueyoshi et al., 1995). Vero cells are commonly used for the study of PEDV, but these cells are deficient for type I IFN genes, and we have previously identified MARC-145 as an additional cell line permissive for PEDV. In these cells, PEDV has been shown to inhibit type I IFN production (Zhang et al., 2016). However, MARC-145 cells are originated from monkey kidney epithelium, and porcine epithelial cells will serve a better model to study the innate immune regulation for PEDV. To this aim, we identified LLC-PK1 as a permissive cell line for PEDV. LLC-PK1 is of porcine kidney epithelial cells, and we found that these cells efficiently supported PEDV infection. Even at an MOI of 0.01, almost 100% of LLC-PK1 cells became infected by 24 h of infection (data not shown). Western blot analysis of PEDV N protein confirmed the productive infection in LLC-PK1 cells ( Fig. 1A). To examine the growth of PEDV, LLC-PK1, MARC-145, and Vero cells were infected with the virus at a low MOI (0.01), and the culture supernatants were collected to determine the titers at different times of infection. The growth curves show the productive infection of PEDV in these cells (Sup Fig. 1A). Similar growth kinetics was observed for Vero and MARC-145 cells. PEDV induced extensive cell fusion in Vero cells and these cells died by 24 h post-infection (hpi). LLC-PK1 cells supported PEDV growth most efficiently, and the peak viral titer was as high as 107.5 TCID50/ml at 48 hpi (Sup Fig. 1A), compared to 105 TCID50/ml in MARC-145 cells. The one-step growth curve for PEDV was determined by infecting with a high MOI of 5. Syncytia formation characteristic for PEDV was evident as early as 9 hpi in PEDV-infected cells (Sup Fig. 1B, arrows). The one step growth curve showed that PEDV replicated in LLC-PK1 cells most effectively compared to MARC-145 and Vero cells (Sup Fig. 1C). To examine the type I IFN regulation in LLC-PK1 by PEDV, cells were infected with the virus, and RT-qPCR was conducted for both IFN-α and IFN-β mRNAs. While poly(I:C) induced the production of IFN-α and INF-β in uninfected LLC-PK1 cells as anticipated, hardly any IFN-α/β were produced in PEDV-infected LLC-PK1 cells especially at 8–24 hpi (Fig. 1B). Even at 5 MOI, PEDV infection did not induce type I IFNs (Fig. 1C) and also inhibited the production of type I IFNs even when stimulated with poly(I:C) (Fig. 1D, E), further confirming the suppression of type I IFN production by PEDV.

Fig. 1.

Suppression of type I IFN production in LLC-PK cells by PEDV. (A), Expression of N protein in PEDV-infected cells. Cells were infected with PEDV at an MOI of 0.01 for 24 h, and Western blot was conducted using anti-N mAb. (B) and (C), Suppression of type I IFN production by PEDV. LLC-PK1 cells were grown in 12-well plates and infected with PEDV either at a low MOI (0.01 MOI, panel B) or a high MOI (5 MOI, panel C). Cells were harvested at indicated times, and expressions of IFN-α and IFN-β were determined by RT-qPCR. Cells stimulated with poly(I:C) for 12 h were used as positive controls. (D) and (E), Stimulation for type I IFN production by poly(I:C) and suppression by PEDV. LLC-PK1 cells were infected with PEDV at an MOI of 0.01 for 12 h, and stimulated with poly(I:C) for 12 h. Cells were harvested and expression of IFN-α (D) and IFN-β (E) were determined by RT-qPCR. Asterisks indicate statistical significance calculated by the Student's t-test. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

2.2. Inhibition of early production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by PEDV

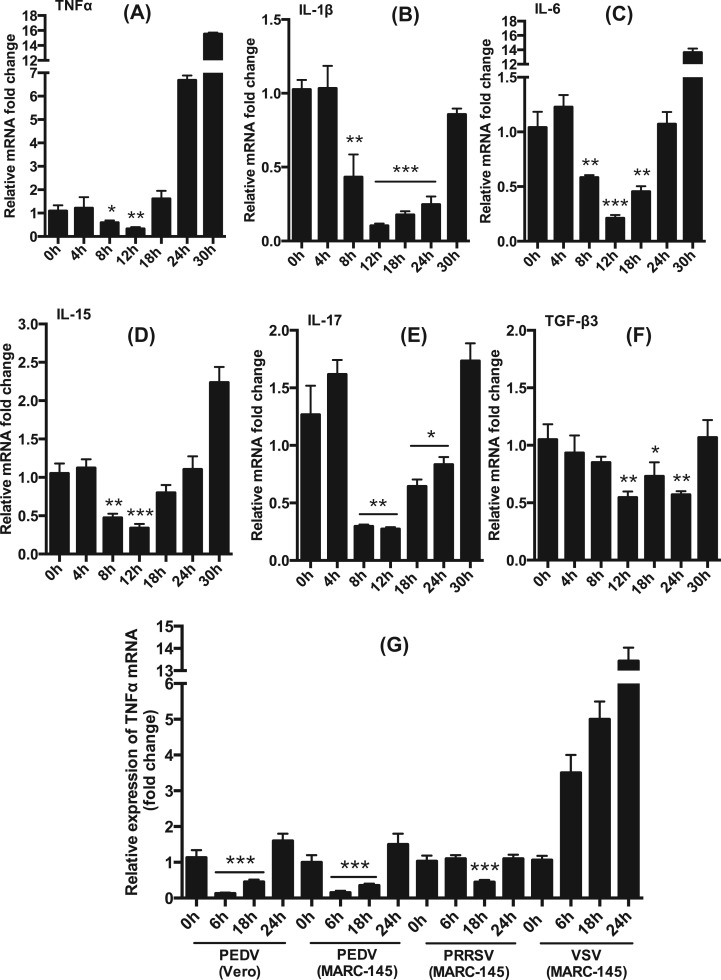

Evidence suggests that PEDV modulates innate immune response for optimal viral replication (Annamalai et al., 2015, Zhang et al., 2016, Zhang and Yoo, 2016). PEDV may also have the ability to modulate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines for viral pathogenesis and virulence. To determine this possibility, we assessed the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in virus-infected cells. LLC-PK1 cells were infected with PEDV, and total RNA was prepared at different times to determine different cytokine gene expressions by RT-qPCR using specific primers (Table 2). PEDV infection caused down-regulation of TNFα during 8–12 hpi, but later times of 24–30 hpi, its expression was upregulated ( Fig. 2A). The IL-1β mRNA levels were significantly downregulated at early times (8–24 hpi) and returned to the basal level by 30 hpi (Fig. 2B). The IL-6 mRNA expression was also suppressed at 8–18 hpi but became activated at 30 hpi (Fig. 2C). Similarly, the IL-15 expression was inhibited at early times (8–18 hpi) but activated later times of infection (24–30 hpi) (Fig. 2D). The IL-17 expression was also suppressed at 8–24 hpi but upregulated at 30 hpi (Fig. 2E), and the TGF-β3 expression was inhibited at 12 and 24 hpi (Fig. 2F). These results demonstrate that PEDV regulated the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in a time-dependent manner. This was confirmed in two other cell types, MARC-145 and Vero, using TNFα mRNA. PRRSV is known to suppress TNFα production (Subramaniam et al., 2010) and VSV is known to activate TNFα production (Garcia et al., 2009), and thus both viruses were included as controls. As anticipated, PRRSV inhibited the expression of TNFα at 18 hpi, whereas VSV activated the TNFα expression continuously over time (Fig. 2G). In both PEDV-infected MARC-145 cells and Vero cells, the TNFα expression was suppressed at early times (6–18 hpi) and became activated later (24 hpi), confirming the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines by PEDV at early times.

Table 2.

Real-time PCR primer sets for cytokine genes used in this study.

| Genes | Forward primer (5'−3') | Reverse primer (5'−3') | Accession no./references |

|---|---|---|---|

| sIFN-α* | GCCTCCTGCACCAGTTCTACA | TGCATGACACAGGCTTCCA | (Loving et al., 2006) |

| sIFN-β | AGTGCATCCTCCAAATCGCT | GCTCATGGAAAGAGCTGTGGT | (de Los Santos et al., 2006) |

| sTNFα | AACCTCAGATAAGCCCGTCG | ACCACCAGCTGGTTGTCTTT | (Gudmundsdottir and Risatti, 2009) |

| sIL−1β | ACCTGGACCTTGGTTCTCTG | CATCTGCCTGATGCTCTTGT | NM_214055.1 |

| sIL−6 | CTGGCAGAAAACAACCTGAACC | TGATTCTCATCAAGCAGGTCTCC | (Duvigneau et al., 2005) |

| sIL−8 | CCGTGTCAACATGACTTCCAA | GCCTCACAGAGAGCTGCAGAA | (Royaee et al., 2004) |

| sIL−15 | GCTGTATCAGTGCAGGTCTTCCT | TTTCAGTATACAATGTGGCATCCA | (Gudmundsdottir and Risatti, 2009) |

| sIL−17 | AATGCTGAAGGGAAGGAAGA | CCCACTGTCACCATCACTTT | NM_001005729.1 |

| sCXCL10 | CTGCATCAAGATCAGTGACAGAC | TTGTGGCAATGATCTCAACAT | NM_001008691.1 |

| sMCP−1 | GCAGCAAGTGTCCTAAAGAAGCA | GCTTGGGTTCTGCACAGATCT | (Gudmundsdottir and Risatti, 2009) |

| sRANTES | AGCATCAGCCTCCCCATATG | TTGCTGCTGGTGTAGAAATATTCC | (Gudmundsdottir and Risatti, 2009) |

| sTGFβ3 | CCTTCGACGTCACAGACACT | TGTGACACGGACAATGAATG | XM_005666355.2 |

| mTNFα | CCTCTTCAAGGGCCAAGGCT | TGGGCTCATACCAGGGCTTG | U19850.1 |

| β-actin | ATCGTGCGTGACATTAAG | ATTGCCAATGGTGATGAC | (Zhang et al., 2016) |

Note: ‘s’ in the front of each gene denotes swine specific primers; ‘m’ for TNFα indicates monkey specific primers; β-actin primers were universal for swine, monkey, and human.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of early production of proinflammatory cytokines by PEDV. (A) through (F), Inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines at early times of infection. LLC-PK1 cells were infected with PEDV at an MOI of 0.01 and cells were harvested at indicated times for expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines by RT-qPCR. (G), Inhibition of the induction of TNFα by PEDV in Vero and MARC-145 cells. Cells were infected with PEDV at an MOI of 1 for indicated times and the production of TNFα was determined by RT-qPCR. PRRSV as a known inhibitor of TNFα and VSV as a known stimulator were included as controls. Asterisks indicate statistical significance calculated by the Student's t-test. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

2.3. Temporal regulation of TNFα-induced NF-κB activation by PEDV

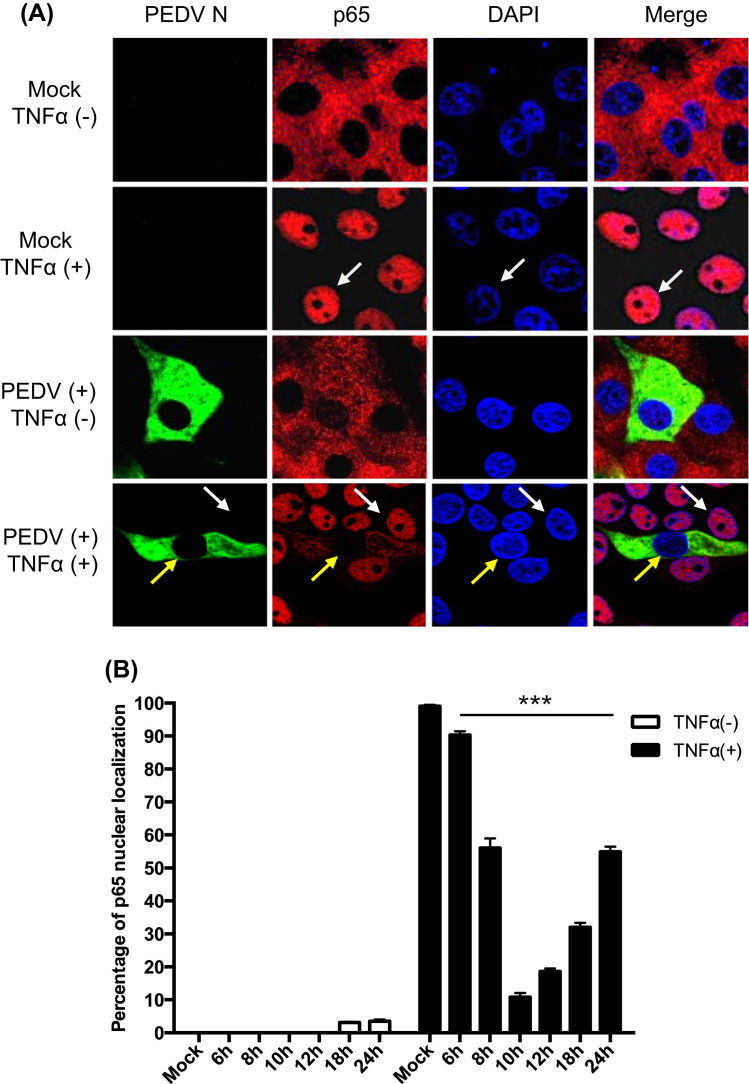

The NF-κB signaling is a central pathway regulating the production of proinflammatory cytokines (Blackwell and Christman, 1997). Viral infections can trigger NF-κB activation and produce TNFα and IL-1, which in turn may activate NF-κB in a positive regulatory loop (Barnes and Karin, 1997). This positive feedback mechanism may amplify and perpetuate local inflammatory reactions. To understand the basis for PEDV suppression of early proinflammatory cytokines, we first examined whether PEDV induced the NF-κB nuclear translocation. LLC-PK1 cells were infected with PEDV and treated with TNFα, followed by co-staining with anti-p65 mAb and anti-PEDV N mAb. Without TNFα treatment, p65 remained in the cytoplasm as anticipated. When stimulated with TNFα, however, p65 was translocated to the nucleus in uninfected cells ( Fig. 3A, white arrows). Interestingly in PEDV-infected cells, p65 remained in the cytoplasm, and even after stimulation with TNFα, p65 was not translocated to the nucleus and remained in the cytoplasm in virus-infected cells (Fig. 3A, yellow arrows), indicating that NF-κB activation by TNFα was inhibited by PEDV. Only a minimal fraction of PEDV-infected cells showed p65 in the nucleus at late infection. The ratios for p65 nuclear translocation were quantified in PEDV-infected cells (Fig. 3B). PEDV did not induce p65 nuclear translocation through 12 hpi, and only approximately 4% of PEDV-infected cells showed p65 in the nucleus at 18–24 hpi in the absence of TNFα stimulation. The suppression of p65 in PEDV-infected cells after TNFα stimulation was proportional to viral replication with the peak at 10 hpi followed by a gradual decrease. This result indicates that PEDV suppresses early NF-κB activation. Two other cell types permissive for PEDV were examined for p65 nuclear translocation. Similar to LLC-PK1, both MARC-145 and ST cells showed the lack of p65 nuclear translocation when infected with PEDV and stimulated with TNFα (data not shown), indicating that the PEDV-mediated NF-κB suppression was cell type-independent. The p65 phosphorylation remained unchanged at the basal level in PEDV-infected cells throughout the infection (data not shown), which further confirms the cell-type independent suppression of NF-κB by PEDV.

Fig. 3.

PEDV-mediated inhibition of TNFα-stimulated p65 nuclear translocation. (A), Inhibition of TNFα-stimulated p65 nuclear localization by PEDV. LLC-PK1 cells were infected with PEDV for 12 h and stimulated with TNFα as the concentration of 15 ng/ml for 20 min. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-N antibody and anti-p65 antibody. White arrows indicates the non-infected cells, yellow arrows indicates the PEDV-infected cells. (B), LLC-PK1 cells were infected with PEDV and stimulated with TNFα at different times. Percentages of cells showing p65 nuclear localization were quantified by randomly counting 200 PEDV-infected cells. The data were obtained from three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance calculated by the Student's t-test. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

2.4. Identification of PRD II and NF-κB antagonists for PEDV

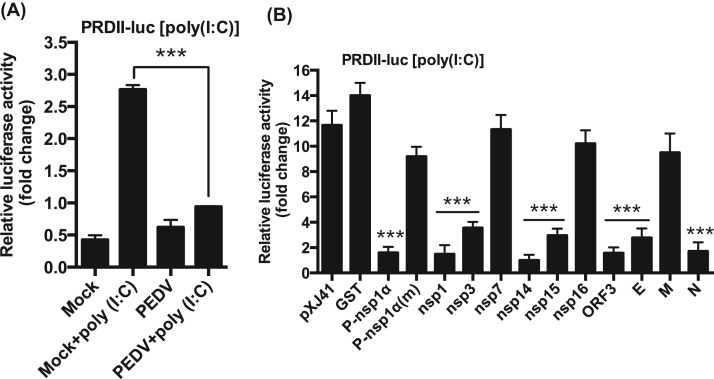

Once IRF3/7 and NF-κB translocate to the nucleus, they bind to their respective PRD domains for expression of type I IFNs. Activated IRF3/7 binds to PRD I/III element in the nucleus, whereas NF-κB binds to the PRD II element for IFN gene expression. Evidence shows that type I IFN suppression by PEDV is mediated through the IRF3/7 singling pathways (Cao et al., 2015a, Xing et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2016). To examine whether PEDV inhibited PRD II, luciferase assays were performed. It was apparent that the PRD II activity was suppressed even when stimulated with poly(I:C) in PEDV-infected cells ( Fig. 4A), demonstrating the significant inhibition of NF-κB-mediated IFN production by PEDV. We previously identified ten different PEDV proteins as IFN antagonists (Zhang et al., 2016), and these proteins suppressed the PRD I/III activity. Thus to identify PRD II antagonists among the ten viral protein, PRD II luciferase assays were conducted for these proteins. PRRSV nsp1α (P-nsp1α) is known to inhibit PRD II and included as a positive control, and its cysteine mutant P-nsp1α(m) (C28S) was included as a negative control (Han et al., 2013, Song et al., 2010). Upon stimulation, PRD II-dependent luciferase activities were reduced in cells expressing nsp1, nsp3, nsp14, nsp15, ORF3, E, and N protein, compared to those of pXJ41 empty vector- and GST gene-transfected cells (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that NF-κB-mediated type I IFNs suppression also participate in type I IFN suppression by these viral proteins.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of NF-κB-mediated IFN production by PEDV. (A), Inhibition of PRD II promoter by PEDV. MARC-145 cells were co-transfected with the pPRD II-Luc reporter plasmid along with the pRL-TK internal control for 6 h followed by PEDV infection at an MOI of 1 for 12 h. Cells were then stimulated with poly(I:C) for 12 h, and cell lysates were subjected to dual-luciferase reporter assays. Results from three independent experiments were presented as the mean relative luciferase values. Asterisks indicate statistical significance calculated by the Student's t-test. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. (B), Inhibition of PRD II promoter by PEDV proteins. HeLa cells were co-transfected with the pPRD II-Luc reporter along with individual type I IFN antagonist for PEDV followed by stimulation with poly(I:C). Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to luciferase assays. PRRSV nsp1α (P-nsp1α) is known to inhibit the PRD II promoter and was included as a positive control. Its mutant P-nsp1α(m) (C28S) was included as a negative control (Han et al., 2013, Song et al., 2010). Results from three independent experiments were presented as the mean relative luciferase values with standard deviation. Asterisks indicate statistical significance calculated by the Student's t-test. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

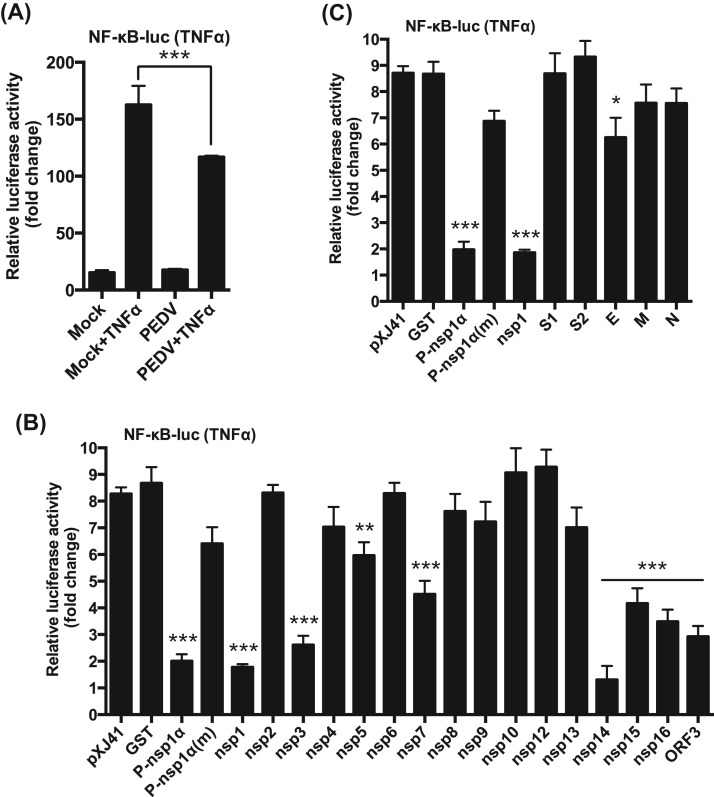

In uninfected cells, NF-κB was activated up to 150 folds by TNFα stimulation ( Fig. 5A). In PEDV-infected cells, however, NF-κB activation was blocked even after TNFα stimulation (Fig. 5A), suggesting a possible suppression of proinflammatory cytokines, in addition to the suppression of type I IFNs, by PEDV at early time of infection. It was of interest to first identify viral proteins inhibiting NF-κB, and therefore individual PEDV genes were examined. As anticipated, TNFα upregulated NF-κB in cells expressing GST and P-nsp1α (m), whereas P-nsp1α suppressed the NF-κB activity (Fig. 5B). Of nsps of PEDV, nsp1, nsp3, nsp5, nsp7, nsp14, nsp15 and nsp16 appeared to downregulate the NF-κB activity, and similarly, the ORF3 protein also downregulated NF-κB (Fig. 5B). Of structural proteins, only E protein was found to suppress the NF-κB activity (Fig. 5C). Among all NF-κB antagonists, nsp1 and nsp14 appeared to be the most potent inhibitors.

Fig. 5.

Identification of NF-κB antagonists of PEDV. (A), Suppression of TNFα-stimulated NF-κB activity by PEDV. MARC-145 cells were co-transfected with pNF-κB-Luc along with pRL-TK in 12-well plates for 6 h followed by PEDV infection at an MOI of 1 for 12 h. Cells were then stimulated with TNFα at the concentration of 15 ng/ml for 9 h, and cell lysates were prepared for dual-luciferase reporter assays. Results from three independent experiments were presented as the mean relative luciferase values with standard deviation. Asterisks indicate statistical significance calculated by the Student's t-test. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. (B) and (C), Regulation of TNFα-induced NF-κB activity by individual PEDV proteins. HeLa cells were grown in 48-well plates and co-transfected with pNF-κB-Luc along with individual PEDV genes and pRL-TK at a ratio of 10:10:1. For nsp3, nsp5, and nsp16, transfection was conducted as described previously (Zhang et al., 2016). PRRSV nsp1α (P-nsp1α) is a known NF-κB promoter suppressor, and its mutant P-nsp1α(m) reverts its suppressive function. Both constructs were included as controls. Cells were stimulated with poly(I:C) (0.5 μg/ml) at 12 h post-transfection for 12 h and dual luciferase activities were determined. Results from three independent experiments were presented as the mean relative luciferase values with standard deviation. Asterisks indicate statistical significance calculated by the Student's t-test using GST as a control. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

2.5. Suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines of PEDV nsp1

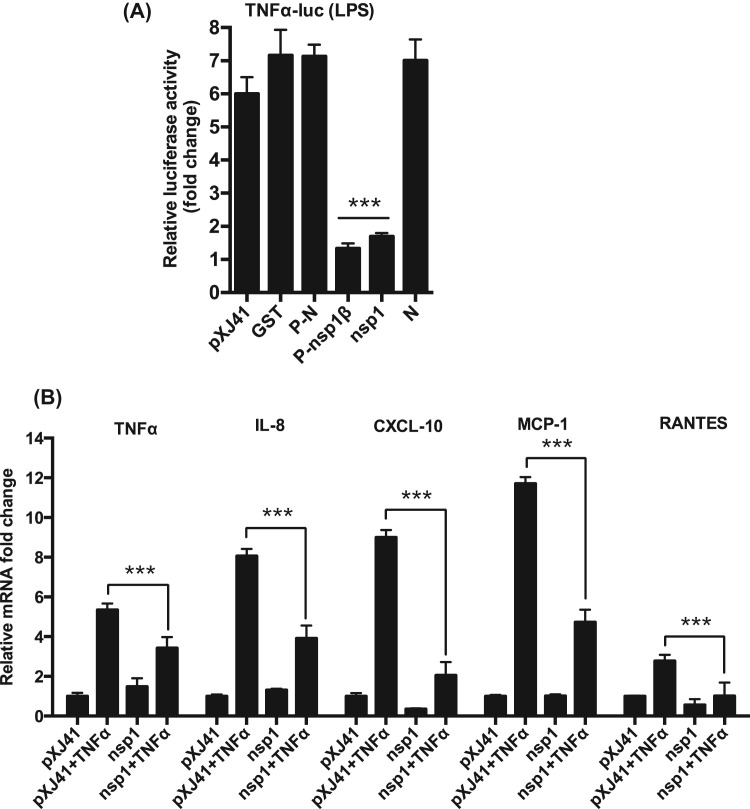

PEDV nsp1 is a nuclear-cytoplasmic protein and antagonizes type I IFN production by degrading the CREB-binding protein in the nucleus (Zhang et al., 2016). In the present study, PEDV nsp1 also appeared to inhibit the activation of PRD II and NF-κB (Fig. 4B and Fig. 5B). It seems that nsp1 blocks NF-κB so as to inhibit the production of IFNs and proinflammatory cytokines. Thus, it was of interest to examine whether nsp1 suppressed TNFα expression. PRRSV nsp1β (P-nsp1β) has been shown to suppress TNFα activation by inhibiting NF-κB and Sp1, and PRRSV N (P-N) does not interfere with TNFα activation (Subramaniam et al., 2010), and thus both constructs were included as controls. Similar to P-nsp1β, PEDV nsp1 appeared to suppress the TNFα activation when stimulated with LPS ( Fig. 6A). Suppression of proinflammatory cytokines by nsp1 was examined by RT-qPCR in nsp1-gene transfected cells, and the results showed that nsp1 significantly suppressed TNFα mRNA transcription (Fig. 6B), validating the nsp1 antagonism against TNFα expression. PEDV nsp1 also suppressed the expression of IL-8, CXCL10, MCP-1, and RANTES (Fig. 6B), indicating that PEDV nsp1 was able to antagonize TNFα-mediated NF-κB activation and suppressed the proinflammatory cytokines.

Fig. 6.

Suppression of proinflammatory cytokines by PEDV nsp1. (A), Suppression of TNFα promoter by nsp1. RAW cells were co-transfected with pswTNFα-Luc and individual viral genes along with pRL-TK for 24 h followed by stimulation with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 6 h. Firefly luciferase activities were determined and normalized using the Renilla luciferase internal control. PRRSV nsp1β (P-nsp1β) is known to suppress TNFα promoter and was included as a control (Subramaniam et al., 2010). Results from three independent experiments were presented as the mean relative luciferase values. Asterisks indicate statistical significance calculated by the Student's t-test. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. (B), Inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines by nsp1. LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with PEDV nsp1 gene for 12 h and stimulated with TNFα (15 ng/ml) and for 12 h. Expressions of proinflammatory cytokines were determined by RT-qPCR. Asterisks indicate statistical significance calculated by the Student's t-test. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

2.6. Inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation and degradation by PEDV nsp1 and blockage of p65 nuclear transport

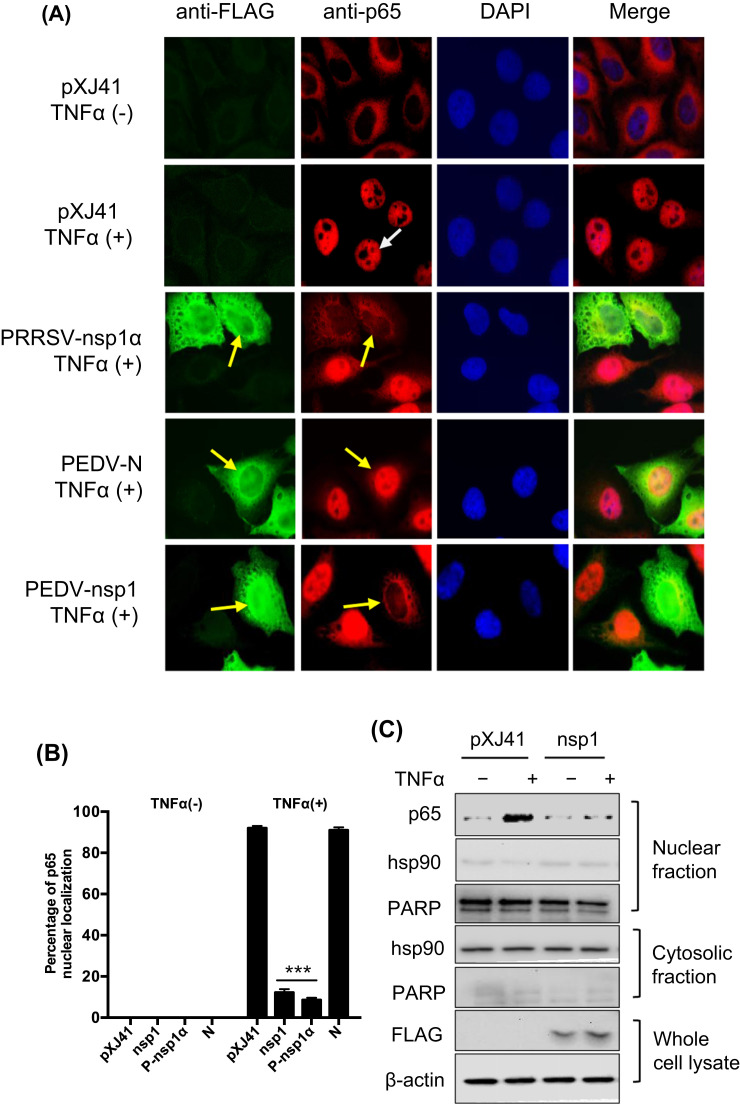

Stimulation of cytokine receptors such as those in the TNF receptor superfamily by TNFα or IL-1 leads to activation of the IKK complex (IKKα/β). Activated IKK induces IκBα phosphorylation, resulting in its proteasomal degradation and release of NF-κB for nuclear translocation and subsequent activation of target gene expressions (Napetschnig and Wu, 2013). The p65 subunit of NF-κB is a key transcription factor for downstream signaling, and in the present study, PEDV appears to inhibit p65 nuclear translocation (Fig. 3). To investigate the mechanism of NF-κB suppression by nsp1, nuclear translocation of p65 was first examined in nsp1-expressing cells. Without TNFα stimulation, nsp1, PEDV N, and PRRSV nsp1α did not activate p65, and it remained in the cytoplasm. When the N-expressing cells were stimulated with TNFα, p65 was activated and normally translocated to the nucleus as anticipated ( Fig. 7A). In contrast, p65 was remained in the cytoplasm in PRRSV nsp1α-expressing control cells and PEDV nsp1-expressing cells after TNFα stimulation, indicating that PEDV nsp1 suppressed the p65 nuclear translocation. Only 10–13% of nsp1-expressing cells showed the p65 in the nucleus, whereas more than 90% of control cells showed p65 in the nucleus after TNFα stimulation (Fig. 7B), confirming that PEDV nsp1 blocked p65 nuclear translocation. The cell fractionation study also confirmed the blockage of p65 nuclear translocation in nsp1-expressing cells (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of p65 nuclear translocation by nsp1 and inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation. (A) and (B), PEDV nsp1 blocks p65 nuclear translocation. HeLa cells were co-transfected with pXJ41 (empty plasmid), nsp1, N, and PRRSV nsp1α for 24 h followed by stimulation with TNFα (15 ng/ml) for 20 min. Cells were then subjected to immunostaining. PRRSV nsp1α is known to inhibit p65 nuclear translocation and was included as a positive control. White arrows indicates p65 in mock-transfected cells, and yellow arrows indicate p65 in gene-transfected cells (panel A). The percentages of cells showing p65 activation were calculated by examining 200 gene-transfected cells in three independent experiments (panel B). Asterisks indicate statistical significance calculated by the Student's t-test. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. (C), Cell fractionation and Western blot. HeLa cells were transfected with PEDV nsp1 gene for 24 h and then stimulated with TNFα for 12 h. Cells were subjected to nuclear-cytoplasmic fractionation to determine subcellular distribution of p65. Hsp90 is a cytosolic protein and was included as the cytosolic marker and PARP was included as a nuclear protein marker. (D), PEDV nsp1 inhibits IκBα phosphorylation and subsequent degradation. HeLa cells were transfected with PEDV nsp1 gene or PRRSV nsp1α (P-nsp1α) for 24 h and then stimulated with TNFα for indicated times. Cells were lysed and subjected to Western blot using IκBα antibody and phophso-IκBα antibody. P-nsp1α is known to inhibit IκBα phosphorylation and was included as a control. (E) and (I), Inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation by nsp1 by the densitometric analysis using the β-actin as an internal control. 7E corresponds to 7D, and 7I corresponds to 7 H. Results from three independent experiments were presented as the mean values with standard deviation. Asterisks indicate statistical significance calculated by the Student's t-test comparing to the pXJ41 empty-vector-transfected cells. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. (F) Inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation by nsp1 is dose-dependent. HeLa cells were transfected with an increasing amount of nsp1 and treated with TNFα for 5 min. Cells were lysed and subjected to Western blot using anti-IκBα and anti-phospho-IκBα antibodies. (G) Inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation by nsp1. LLC-PK1 cells were infected with PEDV at an MOI of 5 and cells were lysed at indicated times, followed by Western blot using anti-IκBα and anti-phospho-IκBα antibodies. Mock-infected cells with the treatment of TNFα for 5 min were used as a control. (H), PEDV nsp1 does not interfere phosphorylation of IKKα/IKKβ. HeLa cells were transfected with PEDV nsp1 gene for 24 h and then stimulated with TNFα for indicated times. Cells were lysed and subjected to Western blot using antibodies for p-IKKα/IKKβ, IKKα, IKKβ, IκBα, and p-IκBα.

Activated IKKβ phosphorylates IκBα for its degradation via ubiquitination. To examine whether nsp1-mediated NF-κB suppression was due to the prevention of IκBα phosphorylation and subsequent degradation, IκBα phosphorylation was examined by Western blot. In contrast to cells transfected with the empty vector, phosphorylation of IκBα was reduced, and the amount of IκBα was stable in nsp1-expressing cells as well as in PRRSV nsp1α-expressing control cells when treated with TNFα (Fig. 7D). This result demonstrates that nsp1 inhibited the IκBα phosphorylation. Similar to PRRSV nsp1α, the densitometric analysis for p-IkBα showed the significant inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation by nsp1 after TNFα treatment for 5 min (Fig. 7E). The level of IκBα phosphorylation was further decreased by the increasing amount of nsp1 (Fig. 7F), suggesting that the suppression of IκBα phosphorylation by nsp1 was dose-dependent. TNFα caused the IκBα phosphorylation, but no phosphorylation of IκBα was observed in PEDV-infected cells (Fig. 7G), which confirmed that nsp1 suppressed IκBα phosphorylation. To examine whether nsp1 interferes with IKK activation, nsp1-expressing cells were stimulated with TNFα, and the IKKα/β phosphorylation was examined. The expression of IKKα/β was stable, and the phosphorylation of IKKα/β normally occurred in nsp1-expressing cells (Fig. 7H). The inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation and degradation was also observed (Fig. 7H) and the densitometric analysis also showed this inhibition (Fig. 7I). This indicates that the inhibition by nsp1 takes place between steps of IKK and IκBα in the NF-κB signaling. Together, our data demonstrate that PEDV nsp1 interferes with the IκBα phosphorylation and degradation, resulting in the inhibition of p65 nuclear translocation.

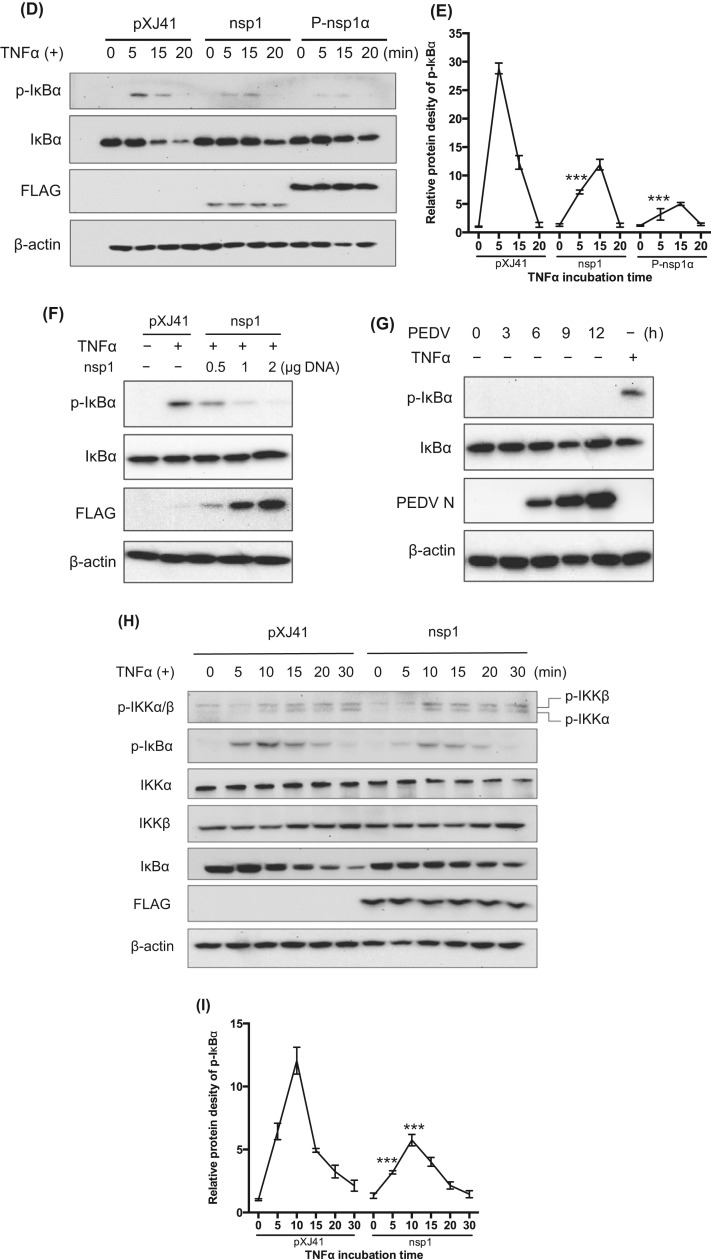

2.7. The highly conserved residues of nsp1 are crucial for NF-κB suppression

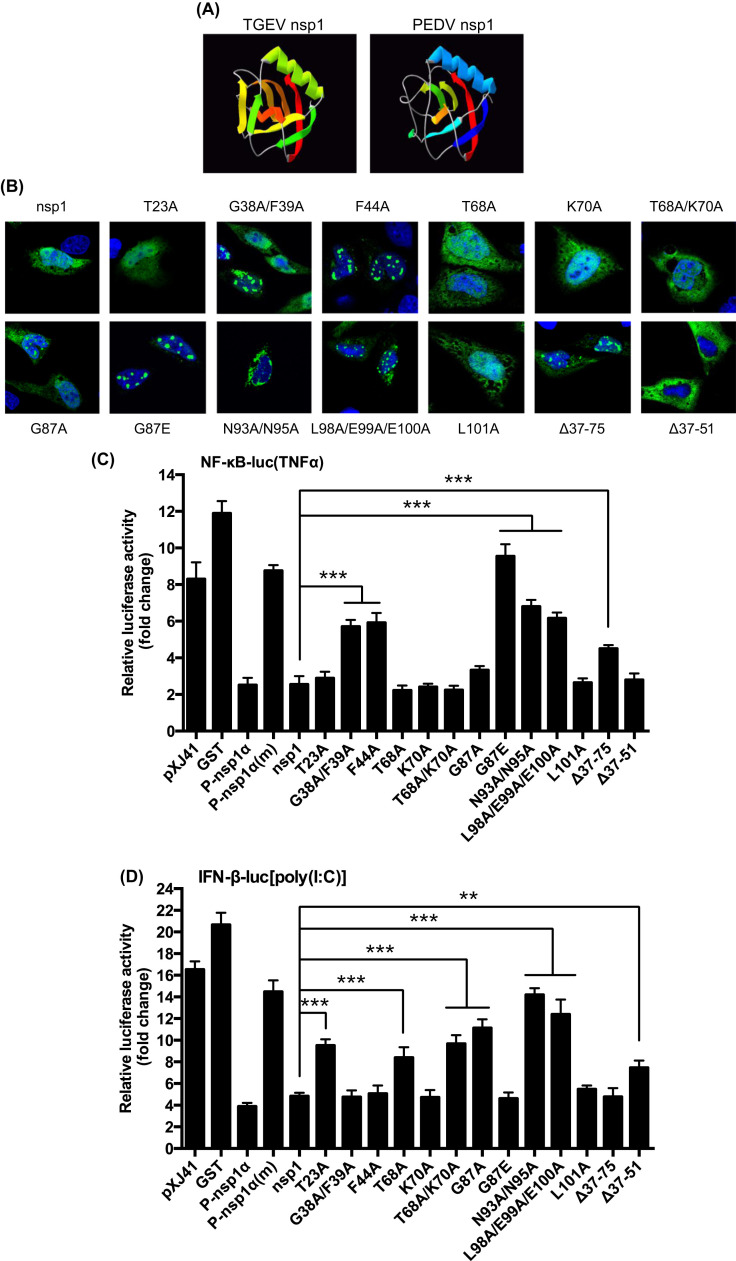

Coronavirus nsp1 is the N-terminal cleavage product of the polyproteins pp1a and pp1ab and is one of the most divergent proteins among the four different genera in the Coronaviridae family (Ziebuhr, 2005). Nsp1 proteins of α-CoV are similar in their lengths and thus may share some functions (Narayanan et al., 2015). Similar to PEDV nsp1, transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) nsp1 also inhibits the IFN-β production (Zhang and Yoo, 2016). Thus, we made structural comparisons of PEDV nsp1 and TGEV nsp1. TGEV nsp1 displayed a six-stranded β-barrel fold with a long α-helix on the rim of the barrel ( Fig. 8A, left panel; Jansson, 2013), and PEDV nsp1 showed a similar structure, except two missing β-sheets (Fig. 8A, right panel), suggesting that PEDV nsp1 may have a unique mechanism for immune modulation. As with TGEV nsp1, the surface of PEDV nsp1 displayed two highly conserved areas. The first area was consisted of four conserved residues D13/E15/N93/N95, and the second area was consisted of three conserved residues L98/E99/E100. These two areas made up two conserved circles placed on a protruding ridge and were potential surfaces for interaction with a partner molecule. Besides, two highly conserved residues (G38/F39) were connected to the hydrophobic core of PEDV nsp1, whereas G87 was highly conserved. We hypothesized that the change of the conserved residues might revert the IFN suppression function of nsp1. To examine this hypothesis, 13 nsp1 mutants were made based on the structural prediction. The mutated genes were individually expressed in cells and examined for their cellular distributions by confocal microscopy. Consistent with the previous report (Zhang et al., 2016), PEDV nsp1 appeared as a nuclear-cytoplasmic protein (Fig. 8B). Among the nsp1 mutants, T23A, T68A, K70A, T68A/K70A, and L101A remained nuclear-cytoplasmic. G38A/F39A, F44A, G87A, G87E, L98A/E99A/E100A, and the deletion mutant Δ37-75 exhibited nuclear punctate patterns. N93A/N95A was perinuclear whereas Δ37-51 became cytoplasmic, suggesting the deletion region was crucial for nuclear localization of nsp1. The results indicated that the highly conserved residues are crucial to maintain the higher order structure of nsp1. To determine the crucial residues for nsp1-mediated IFN suppression, luciferase assays for NF-κB and IFN-β were performed for individual mutants. While T23A, T68A, G87A, K70A, T68A/K70A, and L101A still retained the function of NF-κB suppression (Fig. 8C), G38A/F39A, F44A, G87E, N93A/N95A, L98A/E99A/E100A, and Δ37-75 lost the NF-κB suppression, indicating that the conserved residues in nsp1 are crucial for NF-κB suppression. The deletion mutant Δ37-51 retained NF-κB inhibition, further confirming that the suppression of NF-κB is a cytoplasmic event. N93A/N95A and L98A/E99A/E100A did not suppress the IFN-β production (Fig. 8D), indicating that the conserved residues are also crucial for type I IFN suppression. Unlike the NF-κB suppression, T23A, T68A, T68A/K70A, and G87A lost the IFN suppression function. Additionally, Δ37-51 was cytoplasmic and lost the IFN suppression function, confirming that the IFN suppression by nsp1 is a nuclear event (Zhang et al., 2016). Our study indicates that the suppression of innate immune responses by PEDV nsp1 relies on its highly conserved residues.

Fig. 8.

Highly conserved residues of nsp1 are crucial for NF-κB suppression. (A), Predication of higher order structure of PEDV nsp1 based on the TGEV nsp1 structure. (B), Cellular distribution of nsp1 mutants. Nsp1 mutants were expressed individually in HeLa cells followed by immunostaining. Confocal images showed their cellular distributions. (C) through (D), Conserved residues are crucial for nsp1-mediated NF-κB/IFN-β suppression. HeLa cells were grown in 48-well plates and co-transfected with pNF-κB-Luc (panel C) or pIFN-β-Luc (panel D) along with individual PEDV nsp1 mutants and pRL-TK at a ratio of 10:10:1. Cells were stimulated with TNFα (panel C) or poly(I:C) (panel D) at 12 h post-transfection for 12 h, and cell lysates were subjected to dual-luciferase reporter assays. Results from three independent experiments are presented as the mean relative luciferase values with standard deviation. Asterisks indicate statistical significance calculated by the Student's t-test using nsp1 as a control. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

3. Discussion

The innate immune system forms the first line of antiviral defense of a host. It activates the production of type I IFNs and proinflammatory cytokines controlled by IRF3/IRF7 and NF-κB. Many viruses have evolved to counteract the host innate immunity for optimal viral adaptation and replication. Studies have shown that PEDV inhibits type I IFN production in virus-infected cells. Of 22 PEDV proteins, ten proteins appear to suppress the IFN production. The nsp1 protein antagonizes the IRF3 signaling by degrading CBP in the nucleus via the proteasome-dependent pathway (Zhang et al., 2016), and the nsp5 protein antagonizes NF-κB to suppress type I IFN production by cleaving NEMO (Wang et al., 2015). The N protein suppresses IRF3 and NF-κB and inhibits IFN-β production (Ding et al., 2014). PEDV infection leads to activation of NF-κB at later times post-infection (Cao et al., 2015b, Xing et al., 2013). However, the basis for temporal regulation of NF-κB for the production of type I IFNs and proinflammatory cytokines is unknown. In the present study, we show that PEDV blocks TNFα-mediated p65 nuclear translocation and have subsequently identified nine NF-κB antagonists. Among these, nsp1 is the most potent NF-κB inhibitor, which blocks the p65 nuclear translocation by inhibiting the phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα.

Both coronaviruses and arteriviruses in the order Nidovirales are sensitive to type I IFNs and modulate the IFN response. Equine arteritis virus (EAV) inhibits type I IFN production in virus-infected equine endothelial cells (Go et al., 2014). Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) is also sensitive to type I IFNs and modulate the IFN production in cells and pigs (Albina et al., 1998, Lee et al., 2004, Overend et al., 2007). Mouse hepatitis coronavirus (MHV) induces extremely low levels of type I IFNs in macrophages, microglia, and oligodendrocytes of infected mice (Li et al., 2010, Roth-Cross et al., 2008, Zhou and Perlman, 2007). SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV also do not induce type I IFN responses in virus-infected cells (Cinatl et al., 2004, Lau et al., 2013, Zhou et al., 2014). TGEV can induce a high level of IFN-α in newborn pigs (La Bonnardiere and Laude, 1981). However, the IFN expression is delayed and the IFN response inhibits TGEV replication in the early stage of infection (Zhu et al., 2017). Protein 7 and nsp1 of TGEV have been shown to counteract the host antiviral response (Cruz et al., 2013, Cruz et al., 2011, Zhang and Yoo, 2016). Viruses often code for multiple IFN antagonists, and PEDV also encodes at least 10 IFN antagonists (Cao et al., 2015a, Xing et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2016). Activated NF-κB binds to PRD II in the nucleus, which is essential for NF-κB-mediated IFN-β production. The p65 subunit of NF-κB specifically functions as a key element for early phase IFN production after infection. The PEDV N protein inhibits NF-κB (Ding et al., 2014), suggesting that the NF-κB inhibition may lead to the suppression of type I IFNs. In the present study, we have shown that PEDV blocks NF-κB activation and suppresses NF-κB-mediated type I IFN production. Of the ten IFN suppressors, nsp7, nsp16, and M do not interfere with PRD II, suggesting the specific target of IRF3/7. Thus, targeting PRD II via NF-κB and PRD I/III via IRF3/7 results in synergistic effects on the viral IFN antagonism to allow efficient replication of the invading virus.

The p65 subunit of NF-κB undergoes various post-translational modifications for activation. Not only for type I IFN induction, but NF-κB is also a key regulator for proinflammatory cytokines including TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 (Lappas et al., 2002). Proinflammatory cytokines initiate inflammation and disease progression during viral infection. IL-12 plays a critical role in the early inflammatory response and the generation of Th1 cells leading to cell-mediated immunity (Hsieh et al., 1993). Activation of NF-κB is critical for host defense and thus occurs rapidly after stimulation without additional protein translation. In turn, NF-κB is an attractive viral target for optimal replication during infection. For SARS-CoV, N protein activates NF-κB (Liao et al., 2005), whereas M protein suppresses NF-κB probably through a direct interaction with IKKβ (Fang et al., 2007). PEDV has also been shown to activate NF-κB later time post-infection (Cao et al., 2015b, Xing et al., 2013), and the N protein is the NF-κB activator for up-regulation of IL-8 and Bcl-2 (Xu et al., 2013). The basis for PEDV-mediated NF-κB modulation remains uncharacterized. We show in the present study that PEDV blocks the NF-κB activation and suppresses the production of early proinflammatory cytokines. The PEDV replication cycle is less than 12 h (Sup Fig. 1), and the inhibition of NF-κB during the early stage of infection may play a role to help viral replication. Nine viral proteins have been identified to regulate NF-κB, and it is of interest to study their individual mode of action for NF-κB.

For activation of NF-κB, the release of IκBα from NF-κB is crucial. In the latent state, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytosol by IκBα. In response to stimulation by TNFα or IL-1, a series of membrane-proximal events lead to activation of the IKK complex (IKKα/β/γ). The IKK complex is responsible for the phosphorylation of two serine residues in IκBα, which in turn leads to Lys48-linked polyubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome. Proteasomal degradation of IκBα frees and translocates NF-κB to the nucleus for binding to the κB DNA element in the specific promoters and enhancers of target genes (Napetschnig and Wu, 2013). Viruses have evolved to develop sophisticated strategies to modulate NF-κB signaling, and ample examples are available. PRRSV nsp1α inhibits IκBα phosphorylation and degradation for suppression of type I IFNs (Song et al., 2010). Bocavirus NS1 and NS1-70 protein blocks the binding of p65 to the κB DNA element and inhibits TNFα-mediated activation of NF-κB (Liu et al., 2016). Molluscum contagiosum poxvirus (MCV) MC160 protein degrades IKKα and prevents TNFα-induced NF-κB activation (Le Negrate, 2012). Influenza virus NS1 protein specifically interacts with IKKα and IKKβ for inhibition of IKKβ-mediated phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα (Gao et al., 2012).

PEDV nsp1 inhibits the phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκBα and blocks p65 from nuclear translocation. PEDV nsp1 does not interfere the phosphorylation of IKKα/β complex (Fig. 7H) nor interact with IκBα or IKKα/β (data not shown), suggesting a possible modulation of posttranslational modifications of IκBα such as SUMOylation. Unlike ubiquitination and degradation of IκBα, SUMOylation of IκBα inhibits NF-κB activation (Desterro et al., 1998). Breast cancer-associated gene 2 (BCA2) functions as an E3 SUMO-ligase and enhances the SUMOylation of IκBα, leading to improved sequestration of NF-κB in the cytoplasm, thereby preventing the expression of NF-κB-responsive genes (Colomer-Lluch and Serra-Moreno, 2017). It is of interest to examine whether PEDV nsp1 recruits an E3 SUMO-ligase and enhances SUMOylation of IκBα.

In coronaviruses, nsp1 proteins of α-CoV and β-CoV are potent IFN antagonists. The β-CoV nsp1 protein regulates cellular and viral gene expressions. SARS-CoV nsp1 is consisted of 180 amino acids and inhibits the translation of capped cellular mRNAs by blocking the formation of the 80 S complex. It also recruits a cellular endonuclease to induce an endonucleolytic cleavage of host mRNAs (Narayanan et al., 2015). Unlike SARS-CoV nsp1, MERS-CoV nsp1 selectively targets host mRNAs for translation inhibition and mRNA degradation but spares mRNAs of cytoplasmic origin (Lokugamage et al., 2015). The α-CoV nsp1 protein also inhibits the expression of reporter genes. The C-terminal portion of β-CoV nsp1 is crucial for host mRNA cleavage, and this region is lost in α-CoV nsp1, suggesting that α-CoV nsp1 may have evolved a distinct mechanism for immune evasion. Unlike SARS-CoV nsp1, TGEV nsp1 does not bind to the 40 S ribosomal subunit for suppression of host gene expression (Huang et al., 2011). Surface electrostatics, shapes, and amino acid conservations between α-CoV nsp1 and β-CoV nsp1 may contribute to different mechanisms for nsp1-induced suppression of host gene expression (Jansson, 2013). The structure of TGEV nsp1 is characterized by an irregular six-stranded β-barrel flanked by a α-helix. Most conserved residues are centered on the highly conserved β7 strand, which is likely involved in its structural stability. Two highly conserved patches on the surface of TGEV nsp1 are placed on a producing ridge formation, which forms potential sites for interaction with cellular proteins (Jansson, 2013). PEDV nsp1 also shows two highly conserved surface patches, and mutations of these regions alter their cellular distributions and functions for IFN and NF-κB suppressions. It is of interest to identify the cellular proteins that may interact with PEDV nsp1. The PEDV full-length infectious clone is available (Beall et al., 2016, Jengarn et al., 2015) and it will be useful to study nsp1 function in pigs using replicating mutant viruses.

In conclusion, we have shown that PEDV inhibits NF-κB activity and early production of proinflammatory cytokines. PEDV modulates TNFα-mediated p65 nuclear localization, and we have identified nine viral NF-κB antagonists. PEDV nsp1 interferes the phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα and blocks NF-κB activation. The conserved residues of nsp1 are crucial for nsp1-mediated NF-κB activity. Our study provides a better understanding for PEDV-mediated innate immune modulation and the basis for PEDV pathogenesis.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Cell culture, viral infection, and titration

Two different lines of African green monkey kidney cells, MARC-145 (Kim et al., 1993) and Vero (ATCC® CCL-81™), were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Corning™ Cellgro™) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco®) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. HeLa cells (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Germantown, MD) were maintained in minimum essential medium (MEM) (Corning™ Cellgro™) with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. LLC-PK1 (Perantoni and Berman, 1979) is a porcine kidney epithelial cell line derived from the kidney of a normal healthy male pig of three weeks of age and was obtained from Dr. K. Chang (Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS). LLC-PK1 cells were maintained in MEM with 5% FBS. RAW264.7 cells were obtained from Dr. G. Lau (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) and maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS.

The recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus expressing green fluorescent protein (VSV-GFP) was kindly provided by Dr. A. Garcia-Sastre (Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY). PEDV (USA/Colorado/2013; GenBank: KF272920) was obtained from Agricultural Research Service US Department of Agriculture (Ames, IA). PEDV was propagated in FBS-free DMEM (or MEM) supplemented with 0.3% tryptose phosphate broth (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 0.02% yeast extract (Teknova, Hollister, CA) containing varying concentrations of trypsin 250 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The optimal trypsin concentration for Vero, MARC-145, and LLC-PK1 cells was 5 μg/ml, 2 μg/ml, and 1 μg/ml, respectively. For PEDV growth curve, cells were infected at either low MOI (0.01 MOI) or high MOI (5 MOI) for 1 h and incubated further. Culture supernatants were collected at indicated times post-infection and titrated using the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) protocol. The viral titers were calculated using the Spearman-Karber equation (Mahy and Kangro, 1996) and presented as the viral growth curve.

4.2. Antibodies and chemicals

Following antibodies were used for immunofluorescence assay (IFA) and Western blot (WB) analysis: mouse anti-PEDV N mAb (Medgene, Brookings, no. SD-1–5, 1:1000 dilution for WB, 1:200 dilution for IFA); rabbit anti-p65 mAb (Cell Signaling Technology, no. 8242, 1:1000 dilution for WB, 1:200 for IFA); mouse anti-hsp90 mAb (Santa Cruz, no. sc-69703, 1:1000 for WB); rabbit anti-PARP pAb (Santa Cruz, no. sc-7150, 1:1000 for WB); mouse anti-IκBα mAb (Thermo Scientific, no. MA5-15132, 1:1000 for WB); mouse anti-p-IκBα mAb (Cell Signaling Technology, no. 9246, 1:1000 dilution for WB); rabbit anti-IKKα pAb (Santa Cruz no. sc-7218, 1:200 for WB); mouse anti-IKKβ mAb (Santa Cruz no. sc-56918, 1:200 for WB); rabbit anti-p-IKKα (Ser180)/IKKβ (Ser181) Ab (Cell Signaling Technology, no. 2681, 1:1000 dilution for WB); mouse anti-β-actin mAb (Santa Cruz no. sc-47778, 1:2000 for WB); rat anti-FLAG Ab (Agilent Technologies, no. 200474, 1:2000 for WB, 1:200 for IFA).

Human TNFα was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (no. 8902) and used at 15 ng/ml or 20 ng/ml. Polyinosinic: polycytidylic acid (polyI:C) and DAPI (4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). QIAamp Viral RNA mini kit and RNeasy mini kit were purchased from QIAGEN (Venlo, Limburg). Power SYBR Green PCR master mix was purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated (goat anti-rabbit, red) and 488-conjugated (goat anti-mouse, green) secondary antibodies and Pierce™ ECL Western blotting substrate were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA).

4.3. Plasmid constructs

The firefly luciferase gene was under the control of the respective promoter as described below and used as a reporter. The plasmid pIFN-β-Luc contains the entire IFN-β enhancer-promoter sequence and was obtained from Dr. S. Ludwig at Heinrich-Heine-Universität, Düsseldorf, Germany (Ehrhardt et al., 2004). The plasmid pNF-κB-Luc (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) contains the NF-κB enhancer, which is responsive to the stimulation of TNFα. The plasmid pPRD II-Luc contains two copies of the NF-κB binding region PRD II of the IFN-β promoter and was kindly provided by Dr. S. Perlman at University of Iowa, IA (Zhou and Perlman, 2007). The plasmid pswTNFα-Luc contains swine TNFα promoter sequences and was obtained from Dr. F. A. Osorio at University of Nebraska-Lincoln, NE (Subramaniam et al., 2010). The Renilla luciferase plasmid pRL-TK (Promega) contains the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-tk) promoter and was included as an internal control. Constructs expressing individual proteins of PEDV are described elsewhere (Zhang et al., 2016). PRRSV N (P-N), PRRSV nsp1β (P-nsp1β), PRRSV nsp1α (P-nsp1α), and PRRSV nsp1α cystine mutant P-nsp1α(m) (C28S) are described elsewhere (Han et al., 2013, Song et al., 2010). The higher order structure of PEDV nsp1 was predicted using DNASTAR (https://www.dnastar.com; Madison, WI) based on the X-ray crystallographic structure of TGEV nsp1. PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis was performed to mutate amino acids of PEDV nsp1 and a series of nsp1 mutants were generated. The primers and the position of mutations for each mutant are shown in Table 1. Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing, and mutant protein expressions were examined by immunofluorescence assay and Western blot.

Table 1.

Primers used for the PEDV nsp1 mutants by PCR site-directed mutagenesis.

| Nsp1 mutants | Primer sequence (5'–3') |

|---|---|

| T23A-F | GACGGCTTCACTAGCAGCGCAAAAGCCAAAAGCTG |

| T23A-R | CAGCTTTTGGCTTTTGCGCTGCTAGTGAAGCCGTC |

| G38A/F39A-F | GAAACGGCAGTGCATAGCTGCACTAGCGGCGGCCTC |

| G38A/F39A-R | GAGGCCGCCGCTAGTGCAGCTATGCACTGCCGTTTC |

| F44A-F | CGAGATCGAAGGACACGGCACGGCAGTGCATAAATCCA |

| F44A-R | TGGATTTATGCACTGCCGTGCCGTGTCCTTCGATCTCG |

| T68A-F | CACTAAGCTTGGTAGCGCCGACCACCACCAT |

| T68A-R | ATGGTGGTGGTCGGCGCTACCAAGCTTAGTG |

| K70A-F | CACATACGCACTAAGCGCGGTAGTGCCGACCACC |

| K70A-R | GGTGGTCGGCACTACCGCGCTTAGTGCGTATGTG |

| T68A/K70A-F | CACATACGCACTAAGCGCGGTAGCGCCGACCACCACCATG |

| T68A/K70A-R | CATGGTGGTGGTCGGCGCTACCGCGCTTAGTGCGTATGTG |

| G87A-F | GTTAGAAAATAACAGCCAAGCACAAATGTTTTTGGGGCG |

| G87A-R | CGCCCCAAAAACATTTGTGCTTGGCTGTTATTTTCTAAC |

| G87E-F | AGTTAGAAAATAACAGCCACTCACAAATGTTTTTGGGGCGGCTAC |

| G87E-R | GTAGCCGCCCCAAAAACATTTGTGAGTGGCTGTTATTTTCTAACT |

| N93A/N95A-F | TAAGCTCTAACTCTTCGAGGAAGTAAGCACAGGCAGAAAATAACAGCCAACCACAAATGT |

| N93A/N95A-R | ACATTTGTGGTTGGCTGTTATTTTCTGCCTGTGCTTACTTCCTCGAAGAGTTAGAGCTTA |

| L98A-F | ACCAAAAGTAAGCTCTAACTCTTCGGCGAAGTAATTACAGTTAGAAAATAAC |

| L98A-R | GTTATTTTCTAACTGTAATTACTTCGCCGAAGAGTTAGAGCTTACTTTTGGT |

| E99A/E100A-F | CGACCAAAAGTAAGCTCTAACGCTGCGAGGAAGTAATTACAGTTAG |

| E99A/E100A-R | CTAACTGTAATTACTTCCTCGCAGCGTTAGAGCTTACTTTTGGTCG |

| L101A-F | CGACGACCAAAAGTAAGCTCTGCCTCTTCGAGGAAGTAATTACA |

| L101A-R | TGTAATTACTTCCTCGAAGAGGCAGAGCTTACTTTTGGTCGTCG |

| Δ37-75F | CCATGTTACATTGGCTTTTGCCAATGAAGCCGTCTCATA |

| Δ37–75R | TATGAGACGGCTTCATTGGCAAAAGCCAATGTAACATGG |

| Δ37-51F | CATGTTACATTGGCTTTTGCCAATGCTTTTGGCTTTTGCACTG |

| Δ37–51R | CAGTGCAAAAGCCAAAAGCATTGGCAAAAGCCAATGTAACATG |

4.4. RNA extraction and quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Cells were washed with PBS and lysed with RLT lysis buffer (QIAGEN). Total cellular RNA was extracted using RNeasy mini kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (QIAGEN). Genomic DNA contaminants were removed by treatment with DNase I (Promega). One µg of RNA was used for reverse transcription using random primers and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega). Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using cDNA and SYBR Green PCR mix in the ABI 7500 real-time PCR system according to the manufacturer's instruction (Life Technologies). The swine-specific real-time qPCR primers for IFN-α, IFN-β, TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-15, IL-17, CXCL10, TGF-β3, MCP-1, RANTES, and β-actin are listed in Table 2. The β-actin gene was used as an internal control for each sample. Specific amplification was confirmed by the sequencing of PCR products and the melting curve analysis of qPCR. Threshold cycles for target genes and differences between Ct values (ΔCt) were determined. Relative levels of transcripts of target genes were shown as fold changes relative to respective controls by the 2−ΔΔCt threshold method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

4.5. Dual luciferase reporter assay

To identify the viral antagonists for NF-κB/PRD II promoter, dual luciferase reporter assays were conducted. HeLa cells were grown in 48-well plates to 80% confluency, and transfected with luciferase reporters, individual viral genes, and pRL-TK at a ratio of 10:10:1 using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instruction (Invitrogen). Cells were stimulated with 0.5 μg/ml of poly(I:C) or 15 ng/ml of TNFα at 12 h post-transfection for 12 h, and then lysed in 60 μl 1X Passive lysis buffer for 20 min at room temperature (RT) with constant shaking. To examine the NF-κB/PRD II promoter activity during PEDV infection, MARC-145 cells were grown in 12-well plates to 80% confluency, and transfected with luciferase reporters and pRL-TK at a ratio of 10:1 using Lipofectamine 2000. Cells were infected with PEDV at 1 MOI at 6 h post-transfection for 12 h, and stimulated with poly(I:C) for 12 h or TNFα for 9 h. Cells were then lysed in 100 μl 1X Passive lysis buffer for 20 min at RT. Supernatants of the cell lysates were subjected to dual Luciferase assays according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). All the values were normalized using the Renilla luciferase activity as the internal control and presented in fold changes. The data are represented as the mean value with a standard deviation from three independent experiments.

4.6. Indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) and confocal microscopy

Cells were grown on coverslips placed in 12-well plates to 80% confluency for transfection or infection. For transfection, HeLa cells were transfected with individual plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). For infection, LLC-PK1 cells were infected with PEDV at 0.01 MOI. At indicated times post-treatment with poly(I:C) or TNFα, cells were washed once and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight at 4 °C followed by permeabilization using 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min at RT. Cells were incubated in the blocking buffer (1% BSA in PBS) for 30 min at RT and then incubated with primary antibody diluted in 1% BSA for 1–3 h. After three washes, cells were incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Scientific) in the dark for 1 h at RT, followed by treatment with DAPI for 10 min to stain the nuclei. After washing with PBS, cover slips were mounted on microscope slides using Fluoromount-G mounting medium (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) and examined for fluorescence using the Nikon A1R confocal fluorescence microscope. The confocal microscopy images were processed using NIS-Elements analysis software.

4.7. Cell fractionation, Co-immunoprecipitation, and western blot analysis

For cell fractionation, HeLa cells were grown in 6-well plates to 80% confluency for gene transfection. Cells were then stimulated with 15 ng/ml TNFα for 12 h and lysed and fractionated using the Nuclear/Cytosol Fractionation kit (BioVision, Milpitas, CA). Briefly, cells were washed once with cold PBS and collected with cell scrapers. Cell pellets were then resuspended in CEB-A buffer on ice for 10 min and after addition of CEB-B further incubated on ice for 1 min. The lysates were centrifuged at 4 °C for 5 min at 16,000 × g, and the supernatants were collected as the cytosolic fraction. Cell pellets were resuspended in NEB buffer and vortexed for 30 s, which was repeated 5 times every 10 min. Cell pellets were centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C at 16,000 × g, and the supernatants were kept as the nuclear fraction.

For co-immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, 100 mg/ml leupetin, 1% NP-40, 10% glycerol] supplemented with the proteinase inhibitors cocktail (Promega), followed by immunoprecipitation as described previously (Zhang et al., 2016). For Western blot, cells were harvested in RIPA buffer [20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40] containing the proteinase inhibitors cocktail (Promega). Cells were lysed on ice for 30 min, sonicated, and centrifuged to remove insoluble components. For Western blot, proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk or 5% BSA in TBST (0.05% Tween-20) for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. After three washes, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at RT. The antibody-antigen complex was visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (Thermo). Images were taken by the FluorChem™ R System according to the manufacturer's instructions (ProteinSimple).

4.8. Statistical analysis

The student's t-test was used for statistical analyses using GraphPad Prism 6. Asterisks indicate the statistical significance as follow: *, P<0.05, **, P<0.01 and ***, P<0.001.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive (AFRI) Grants no. 2013-67015-21243 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)-National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), and the USDA HATCH project no. ILLU-888-363.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.virol.2017.07.009.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- Albina E., Carrat C., Charley B. Interferon-alpha response to swine arterivirus (PoAV), the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 1998;18:485–490. doi: 10.1089/jir.1998.18.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annamalai T., Saif L.J., Lu Z., Jung K. Age-dependent variation in innate immune responses to porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection in suckling versus weaned pigs. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2015;168:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes P.J., Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;336:1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall A., Yount B., Lin C.M., Hou Y., Wang Q., Saif L., Baric R. Characterization of a pathogenic full-length cDNA clone and transmission model for porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain PC22A. MBio. 2016;7 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01451-15. (e01451-15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell T.S., Christman J.W. The role of nuclear factor-kappa B in cytokine gene regulation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1997;17:3–9. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.1.f132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K.J., Perkins N.D. Regulation of NF-kappaB function. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 2006;73:165–180. doi: 10.1042/bss0730165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L., Ge X., Gao Y., Herrler G., Ren Y., Ren X., Li G. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus inhibits dsRNA-induced interferon-beta production in porcine intestinal epithelial cells by blockade of the RIG-I-mediated pathway. Virol. J. 2015;12:127. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0345-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L., Ge X., Gao Y., Ren Y., Ren X., Li G. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection induces NF-kappaB activation through the TLR2, TLR3, and TLR9 pathways in porcine intestinal epithelial cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2015;96:1757–1767. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Li G., Stasko J., Thomas J.T., Stensland W.R., Pillatzki A.E., Gauger P.C., Schwartz K.J., Madson D., Yoon K.J., Stevenson G.W., Burrough E.R., Harmon K.M., Main R.G., Zhang J. Isolation and characterization of porcine epidemic diarrhea viruses associated with the 2013 disease outbreak among swine in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52:234–243. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02820-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinatl J., Jr., Michaelis M., Scholz M., Doerr H.W. Role of interferons in the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2004;4:827–836. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.6.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomer-Lluch M., Serra-Moreno R. BCA2/RABRING7 interferes with HIV-1 proviral transcription by enhancing the SUMOylation of IkappaBalpha. J. Virol. 2017;91:e02098–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02098-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz J.L., Sola I., Becares M., Alberca B., Plana J., Enjuanes L., Zuniga S. Coronavirus gene 7 counteracts host defenses and modulates virus virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002090. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz J.L., Becares M., Sola I., Oliveros J.C., Enjuanes L., Zuniga S. Alphacoronavirus protein 7 modulates host innate immune response. J. Virol. 2013;87:9754–9767. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01032-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debouck P., Pensaert M. Experimental infection of pigs with a new porcine enteric coronavirus, CV 777. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1980;41:219–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desterro J.M., Rodriguez M.S., Hay R.T. SUMO-1 modification of IkappaBalpha inhibits NF-kappaB activation. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:233–239. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z., Fang L., Jing H., Zeng S., Wang D., Liu L., Zhang H., Luo R., Chen H., Xiao S. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus nucleocapsid protein antagonizes beta interferon production by sequestering the interaction between IRF3 and TBK1. J. Virol. 2014;88:8936–8945. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00700-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte M., Gelfi J., Lambert P., Rasschaert D., Laude H. Genome organization of porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1993;342:55–60. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2996-5_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvigneau J.C., Hartl R.T., Groiss S., Gemeiner M. Quantitative simultaneous multiplex real-time PCR for the detection of porcine cytokines. J. Immunol. Methods. 2005;306:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt C., Kardinal C., Wurzer W.J., Wolff T., von Eichel-Streiber C., Pleschka S., Planz O., Ludwig S. Rac1 and PAK1 are upstream of IKK-epsilon and TBK-1 in the viral activation of interferon regulatory factor-3. FEBS Lett. 2004;567:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalante C.R., Shen L., Thanos D., Aggarwal A.K. Structure of NF-kappaB p50/p65 heterodimer bound to the PRDII DNA element from the interferon-beta promoter. Structure. 2002;10:383–391. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00723-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X., Gao J., Zheng H., Li B., Kong L., Zhang Y., Wang W., Zeng Y., Ye L. The membrane protein of SARS-CoV suppresses NF-kappaB activation. J. Med. Virol. 2007;79:1431–1439. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S., Song L., Li J., Zhang Z., Peng H., Jiang W., Wang Q., Kang T., Chen S., Huang W. Influenza A virus-encoded NS1 virulence factor protein inhibits innate immune response by targeting IKK. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:1849–1866. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M.A., Gallego P., Campagna M., Gonzalez-Santamaria J., Martinez G., Marcos-Villar L., Vidal A., Esteban M., Rivas C. Activation of NF-kB pathway by virus infection requires Rb expression. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., May M.J., Kopp E.B. NF-kappa B and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1998;16:225–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go Y.Y., Li Y., Chen Z., Han M., Yoo D., Fang Y., Balasuriya U.B. Equine arteritis virus does not induce interferon production in equine endothelial cells: identification of nonstructural protein 1 as a main interferon antagonist. BioMed. Res. Int. 2014;2014:420658. doi: 10.1155/2014/420658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsdottir I., Risatti G.R. Infection of porcine alveolar macrophages with recombinant chimeric porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: effects on cellular gene transcription and virus growth. Virus Res. 2009;145:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M., Du Y., Song C., Yoo D. Degradation of CREB-binding protein and modulation of type I interferon induction by the zinc finger motif of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nsp1alpha subunit. Virus Res. 2013;172:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden M.S., Ghosh S. NF-kappaB, the first quarter-century: remarkable progress and outstanding questions. Genes Dev. 2012;26:203–234. doi: 10.1101/gad.183434.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermant P., Michiels T. Interferon-lambda in the context of viral infections: production, response and therapeutic implications. J. Innate Immun. 2014;6:563–574. doi: 10.1159/000360084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K., Takaoka A., Taniguchi T. Type I interferon [corrected] gene induction by the interferon regulatory factor family of transcription factors. Immunity. 2006;25:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C.S., Macatonia S.E., Tripp C.S., Wolf S.F., O'Garra A., Murphy K.M. Development of TH1 CD4+ T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science. 1993;260:547–549. doi: 10.1126/science.8097338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Lokugamage K.G., Rozovics J.M., Narayanan K., Semler B.L., Makino S. Alphacoronavirus transmissible gastroenteritis virus nsp1 protein suppresses protein translation in mammalian cells and in cell-free HeLa cell extracts but not in rabbit reticulocyte lysate. J. Virol. 2011;85:638–643. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01806-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson A.M. Structure of alphacoronavirus transmissible gastroenteritis virus nsp1 has implications for coronavirus nsp1 function and evolution. J. Virol. 2013;87:2949–2955. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03163-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jengarn J., Wongthida P., Wanasen N., Frantz P.N., Wanitchang A., Jongkaewwattana A. Genetic manipulation of porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus recovered from a full-length infectious cDNA clone. J. Gen. Virol. 2015;96:2206–2218. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junwei G., Baoxian L., Lijie T., Yijing L. Cloning and sequence analysis of the N gene of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus LJB/03. Virus Genes. 2006;33:215–219. doi: 10.1007/s11262-005-0059-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T., Akira S. Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with other innate receptors in infection and immunity. Immunity. 2011;34:637–650. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.S., Kwang J., Yoon I.J., Joo H.S., Frey M.L. Enhanced replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus in a homogeneous subpopulation of MA-104 cell line. Arch. Virol. 1993;133:477–483. doi: 10.1007/BF01313785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocherhans R., Bridgen A., Ackermann M., Tobler K. Completion of the porcine epidemic diarrhoea coronavirus (PEDV) genome sequence. Virus Genes. 2001;23:137–144. doi: 10.1023/A:1011831902219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Bonnardiere C., Laude H. High interferon titer in newborn pig intestine during experimentally induced viral enteritis. Infect. Immun. 1981;32:28–31. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.1.28-31.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappas M., Permezel M., Georgiou H.M., Rice G.E. Nuclear factor kappa B regulation of proinflammatory cytokines in human gestational tissues in vitro. Biol. Reprod. 2002;67:668–673. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod67.2.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S.K., Lau C.C., Chan K.H., Li C.P., Chen H., Jin D.Y., Chan J.F., Woo P.C., Yuen K.Y. Delayed induction of proinflammatory cytokines and suppression of innate antiviral response by the novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: implications for pathogenesis and treatment. J. Gen. Virol. 2013;94:2679–2690. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.055533-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Negrate G. Viral interference with innate immunity by preventing NF-kappaB activity. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:168–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.M., Lee B.J., Tae J.H., Kweon C.H., Lee Y.S., Park J.H. Detection of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus by immunohistochemistry with recombinant antibody produced in phages. J. Vet. Med. Sci. / Jpn. Soc. Vet. Sci. 2000;62:333–337. doi: 10.1292/jvms.62.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.M., Schommer S.K., Kleiboeker S.B. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus field isolates differ in in vitro interferon phenotypes. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2004;102:217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Liu Y., Zhang X. Murine coronavirus induces type I interferon in oligodendrocytes through recognition by RIG-I and MDA5. J. Virol. 2010;84:6472–6482. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00016-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Q.J., Ye L.B., Timani K.A., Zeng Y.C., She Y.L., Ye L., Wu Z.H. Activation of NF-kappaB by the full-length nucleocapsid protein of the SARS coronavirus. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 2005;37:607–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2005.00082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Zhang Z., Zheng Z., Zheng C., Liu Y., Hu Q., Ke X., Wang H. Human Bocavirus NS1 and NS1-70 Proteins Inhibit TNF-alpha-Mediated Activation of NF-kappaB by targeting p65. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:28481. doi: 10.1038/srep28481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokugamage K.G., Narayanan K., Nakagawa K., Terasaki K., Ramirez S.I., Tseng C.T., Makino S. Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus nsp1 inhibits host gene expression by selectively targeting mRNAs transcribed in the nucleus while sparing mRNAs of cytoplasmic origin. J. Virol. 2015;89:10970–10981. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01352-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Los Santos T., de Avila Botton S., Weiblen R., Grubman M.J. The leader proteinase of foot-and-mouth disease virus inhibits the induction of beta interferon mRNA and blocks the host innate immune response. J. Virol. 2006;80:1906–1914. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1906-1914.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loving C.L., Brockmeier S.L., Ma W., Richt J.A., Sacco R.E. Innate cytokine responses in porcine macrophage populations: evidence for differential recognition of double-stranded RNA. J. Immunol. 2006;177:8432–8439. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahy B.W., Kangro H.O. Harcourt Brace; New York, NY: 1996. Virology Methods Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Marthaler D., Jiang Y., Otterson T., Goyal S., Rossow K., Collins J. Complete Genome Sequence of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Strain USA/Colorado/2013 from the United States. Genome Announc. 2013;1 doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00555-13. (e00555-13) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mole B. Deadly pig virus slips through US borders. Nature. 2013;499:388. doi: 10.1038/499388a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napetschnig J., Wu H. Molecular basis of NF-kappaB signaling. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013;42:443–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan K., Ramirez S.I., Lokugamage K.G., Makino S. Coronavirus nonstructural protein 1: common and distinct functions in the regulation of host and viral gene expression. Virus Res. 2015;202:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overend C., Mitchell R., He D., Rompato G., Grubman M.J., Garmendia A.E. Recombinant swine beta interferon protects swine alveolar macrophages and MARC-145 cells from infection with Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2007;88:925–931. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82585-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perantoni A., Berman J.J. Properties of Wilms' tumor line (TuWi) and pig kidney line (LLC-PK1) typical of normal kidney tubular epithelium. Vitro. 1979;15:446–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02618414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth-Cross J.K., Bender S.J., Weiss S.R. Murine coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus is recognized by MDA5 and induces type I interferon in brain macrophages/microglia. J. Virol. 2008;82:9829–9838. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01199-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royaee A.R., Husmann R.J., Dawson H.D., Calzada-Nova G., Schnitzlein W.M., Zuckermann F.A., Lunney J.K. Deciphering the involvement of innate immune factors in the development of the host response to PRRSV vaccination. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2004;102:199–216. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C., Krell P., Yoo D. Nonstructural protein 1alpha subunit-based inhibition of NF-kappaB activation and suppression of interferon-beta production by porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virology. 2010;407:268–280. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D., Park B. Porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus: a comprehensive review of molecular epidemiology, diagnosis, and vaccines. Virus Genes. 2012;44:167–175. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0713-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark G.R., Darnell J.E., Jr. The JAK-STAT pathway at twenty. Immunity. 2012;36:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson G.W., Hoang H., Schwartz K.J., Burrough E.R., Sun D., Madson D., Cooper V.L., Pillatzki A., Gauger P., Schmitt B.J., Koster L.G., Killian M.L., Yoon K.J. Emergence of Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in the United States: clinical signs, lesions, and viral genomic sequences. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2013;25:649–654. doi: 10.1177/1040638713501675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam S., Kwon B., Beura L.K., Kuszynski C.A., Pattnaik A.K., Osorio F.A. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus non-structural protein 1 suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter activation by inhibiting NF-kappaB and Sp1. Virology. 2010;406:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sueyoshi M., Tsuda T., Yamazaki K., Yoshida K., Nakazawa M., Sato K., Minami T., Iwashita K., Watanabe M., Suzuki Y. An immunohistochemical investigation of porcine epidemic diarrhoea. J. Comp. Pathol. 1995;113:59–67. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9975(05)80069-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M., Ma J., Wang Y., Wang M., Song W., Zhang W., Lu C., Yao H. Genomic and epidemiological characteristics provide new insights into the phylogeographical and spatiotemporal spread of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in Asia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:1484–1492. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02898-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun R.Q., Cai R.J., Chen Y.Q., Liang P.S., Chen D.K., Song C.X. Outbreak of porcine epidemic diarrhea in suckling piglets, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18:161–163. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.111259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstrepen L., Bekaert T., Chau T.L., Tavernier J., Chariot A., Beyaert R. TLR-4, IL-1R and TNF-R signaling to NF-kappaB: variations on a common theme. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:2964–2978. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8064-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]