Abstract

Otitis media (OM) is a common illness in young children. OM has historically been associated with frequent and severe complications. Nowadays it is usually a mild condition that often resolves without treatment. For most children, progression to tympanic membrane perforation and chronic suppurative OM is unusual (low-risk populations); this has led to reevaluation of many interventions that were used routinely in the past. Evidence from a large number of randomized controlled trials can help when discussing treatment options with families. Indigenous children in the United States, Canada, Northern Europe, Australia, and New Zealand experience more OM than other children. In some places, Indigenous children continue to suffer from the most severe forms of the disease. Communities with more than 4% of the children affected by chronic tympanic membrane perforation have a major public health problem (high-risk populations). Higher rates of invasive pneumococcal disease, pneumonia, and chronic suppurative lung disease (including bronchiectasis) are also seen. These children will often benefit from effective treatment of persistent (or recurrent) bacterial infection.

Keywords: Upper respiratory tract infection, Chronic otitis media, Randomized controlled trials, Acute otitis media

Upper respiratory tract infections (including otitis media) are the most common illnesses affecting children.1 The term “otitis media” (OM) covers a wide spectrum of disease, and is used to describe illnesses with predominantly middle ear symptoms (including acute otitis media, otitis media with effusion, and chronic suppurative otitis media). Children can expect to experience around 6 to 8 upper respiratory infections (URTIs) each year.2 Nearly all children will experience at least one episode of OM during childhood. On average, they experience around one episode of acute otitis media (AOM) per year in the first 3 years of life.3

The initial cause of respiratory mucosal infections (including OM) is most commonly a viral infection but can be bacterial (Table 1 ).4 Of importance is that many infections involve both viruses and bacteria.5 Most commonly, an initial viral infection is complicated by a secondary bacterial infection. In developed countries, both viral and bacterial infections are likely to be self-limited. Persistent symptomatic disease is an indication that the child has an ongoing bacterial infection.

Table 1.

Spectrum of disease, accepted terminology, and etiology of the common upper respiratory tract infections in children

| Condition | Related Diagnoses | Etiology |

|---|---|---|

| Otitis media | Otitis media with effusion, acute otitis media without perforation, acute otitis media with perforation, chronic suppurative otitis media | Viral: respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, adenovirus, rhinovirus, coronavirus, enterovirus, parainfluenza, metapneumovirusBacterial: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Streptococcus pyogenes |

By understanding the evidence available from high quality studies, the clinician is in a position to advise the families on appropriate action.6 Well designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide the most reliable evidence of effect (Table 2 ).7 The aim of this article is to support clinicians in answering the following questions:

-

(i)

What happens to children with these conditions when no additional treatment is provided?

-

(ii)

Which interventions have been assessed in well-designed studies?

-

(iii)

Which interventions have been shown to improve outcomes?

-

(iv)

If an intervention is considered appropriate, how large is the overall benefit?

Table 2.

Typical clinical features of the common upper respiratory infections in children that have been assessed in randomized controlled trials

| Condition | Typical Clinical Features |

|---|---|

| Otitis media with effusion | Asymptomatic persistent middle ear effusion confirmed by tympanometry |

| Acute otitis media | Recurrent clinical diagnosis of AOM (≥3 in 6 mo) with red tympanic membrane and ear pain |

| Recurrent acute otitis media | Clinical diagnosis of AOM with red tympanic membrane and ear pain |

| Chronic suppurative otitis media | Discharge through a perforated tympanic membrane for 2–6 wk |

The approach to evidence used in this article

There is a long list of potential interventions for the different forms of OM. Many families have strong personal preferences about their treatment options. The challenge for the clinician is to make an accurate diagnosis and then to match the effective treatment options to the preferences of the family.

In this article, the authors have initially considered the effects of an intervention compared with no intervention. Their focus on trial evidence means that the authors may not review all the relevant information to an individual decision. The overall effects of an intervention may need to be adjusted with this in mind. It is hoped that clinicians using this article should be able to determine which interventions have been rigorously assessed and the overall findings of these assessments.

The GRADE Working Group has described the steps required to review evidence.8, 9, 10 The GRADE Working Group proposes that a recommendation should indicate a decision that the majority of well-informed individuals would make. For self-limited conditions with low risk of complications, even well-informed individuals may reach different conclusions. Therefore, the authors have tried to provide an evidence summary that will assist discussions with families (Table 3 ). The authors' own approach (informed by the best available evidence) is described in Box 1 .

Table 3.

Treatment effects of interventions for otitis media in children who have been assessed in randomized controlled trials

| Intervention | Evidence | Effect (no Intervention vs Intervention) |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention | ||

| Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine11 | 3 studies (39,749 participants) |

Acute otitis media episodes reduced by 6% (eg, 1.0 vs 0.94 episodes per year). Insertion of tympanostomy tubes reduced (3.8% vs 2.9%) |

| Influenza vaccine12, 13 | 11 studies (11,349 participants) |

Inconsistent results. Modest protection against otitis media during influenza season in some studies |

| Treatment of persistent otitis media with effusion | ||

| Antibiotics14, 15 | 9 studies (1534 participants) |

Persistent OME at around 4 weeks reduced (81% vs 68%) |

| Tympanostomy tubes16, 17 | 11 studies (∼1300 participants) |

Modest improvement in hearing: 9dB at 6 mo and 6dB at 12 mo. No improvement in language or cognitive assessment |

| Antihistamines and decongestants18 | 7 studies (1177 participants) |

No difference in persistent OME at 4 wk (75%) |

| Autoinflation19 | 6 studies (602 participants) |

Inconsistent results. Modest improvement in tympanometry at 4 wk in some studies |

| Antibiotics plus steroids20 |

5 studies (418 participants) |

Persistent OME at 2 wk reduced (75% vs 52%) |

| Treatment of initial acute otitis media | ||

| Antihistamines and decongestants21 | 12 studies (2300 participants) |

No significant difference in persistent AOM at 2 wk |

| Antibiotics22, 23 | 8 studies (2287 participants) 6 studies (1643 participants) |

Persistent pain on day 2–7 reduced (22% vs 16%) Persistent AOM reduced in children <2 y old with bilateral AOM (55% vs 30%) and in children with AOM with perforation (53% vs 19%) |

| Myringotomy24 | 3 studies (812 participants) |

Early treatment failure increased (5% vs 20%). |

| Analgesics25 | 1 study (219 participants) |

Persistent pain reduced on day 2 (25% vs 9%). |

| Treatment of recurrent acute otitis media | ||

| Antibiotics26 | 16 studies (1483 participants) |

Acute otitis media episodes reduced (3.0 vs 1.5 episodes per year) |

| Adenoidectomy27, 28, 29 | 6 studies (1060 participants) |

No significant reduction in rates of AOM |

| Tympanostomy tubes27, 30 | 5 studies (424 participants) |

Acute otitis media episodes reduced (2.0 vs 1.0 episodes per year) |

| Treatment of chronic suppurative otitis media | ||

| Topical antibiotics31, 32, 33 | 7 studies (1074 participants) |

Persistent CSOM at 2–16 wk reduced (around 75% vs 20%–50% |

| Ear cleaning31, 34 | 2 studies (658 participants) |

Inconsistent results. No reduction in persistent CSOM at 12–16 wk (78%) in large African study |

Box 1. Suggested approach when assessing and managing a child with OM.

-

1.

Take a history of the presenting complaint to elicit the primary symptoms: nasal discharge or sore throat (nonspecific URTI), ear pain, ear discharge, or hearing loss (OM). Ask about frequency and severity of previous episodes. Clarify duration of illness and presence of any associated features including cough (bronchitis), fever, respiratory distress, cyanosis, poor feeding, or lethargy. Determine the concerns, expectations, and preferences of the child and their carer. (Grade: very low; Level of evidence: cohort studies and other evidence.)

-

2.

Examine the child to confirm whether investigation and management strategy should include OM. Assess temperature, pulse, and respiratory rate, presence and color of nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, facial tenderness, tonsillar enlargement, tonsillar exudate, cervical lymphadenopathy, presence of cough, presence of middle ear effusion (using pneumatic otoscopy or tympanometry), and position and integrity of tympanic membrane. Ensure normal hydration, perfusion, conscious state, and no meningism, periorbital swelling, proptosis, limitation of eye movements, upper airway obstruction, respiratory distress, or mastoid tenderness. (Grade: very low; Level of evidence: cohort studies and other evidence.)

-

3.Investigations:

-

•Otitis media with effusion (OME): None required for most children. If effusions are bilateral and persistent for >3 months, then organize a hearing test. (Grade: low; Level of evidence: cohort studies.)

-

•AOM: None required unless febrile and <3 months of age, or danger signs present (respiratory distress, cyanosis, poor feeding, or lethargy). (Grade: low; Level of evidence: cohort studies.)

-

•Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM): Organize a hearing test. Imaging (computed tomography scan) is appropriate if CSOM is persistent despite treatment and the tympanic membrane cannot be visualized. (Grade: low; Level of evidence: cohort studies)

-

•

-

4.Management:

-

•OME: No immediate treatment required. Review at 3 months is appropriate if bilateral effusions are present and child is from a high-risk population. (Grade: low; Level of evidence: cohort studies.)

-

•AOM: Symptomatic pain relief if indicated, watchful waiting with advice to parents on likely course and possible complications. For low-risk populations, antibiotics are most likely to benefit those who have AOM with perforation, <2 years and bilateral AOM, already had 48 hours of watchful waiting and no improvement, or are at high risk of suppurative complications (especially perforation of the tympanic membrane). For high-risk populations, antibiotics are recommended. (Grade: high; Level of evidence: RCTs.)

-

•CSOM: Cleaning ear discharge from external canal and topical antibiotics are recommended. (Grade: high; Level of evidence: RCTs.)

-

•

Important health outcomes and treatment effects

The self-limiting nature of modern OM in developed countries is of the utmost importance in determining which treatments are indicated. In this article, groups of children with low rates of suppurative complications of OM are categorized as low-risk populations. Communities where more than 4% of children experience chronic tympanic membrane perforation secondary to suppurative infection are high-risk populations.35

In low-risk populations, OM is generally a condition that resolves without treatment or complications. Unfortunately, tympanic membrane perforation remains a common occurrence for many Indigenous groups.

The outcomes considered important in this article are: (i) persistent disease (short term ≤14 days, medium term >2 weeks to 6 months, long term >6 months); (ii) time to cure; and (iii) complications arising from progressive disease. The authors considered interventions to have very large effects if they were associated with a relative reduction in the outcome of interest of more than 80%; large effects were associated with a reduction in outcome of at least 50%.36 Reductions of between 20% and 50% were considered modest and reductions less than 20% were considered slight (or small). Because only a proportion of children with OM experience bad outcomes, even large relative effects may have modest absolute benefits.

Search strategy

The search targeted evidence-based guidelines, evidence-based summaries, systematic reviews, and RCTs of interventions for otitis media (see Box 2 ). This simple strategy identified over 1600 hits using PubMed alone. To be included as an evidence-based guideline, summary, or systematic review, one needed to provide an explicit search strategy and criteria for study inclusion. To be included as a clinical trial, randomization needed to be used. Four primary sources to identify relevant information were used: Clinical Evidence (Issue 1 2009),36 the Cochrane Library (Issue 2 2009),37 Evidence-Based Otitis Media27 and Medline (last accessed via PubMed on 26 June, 2009). The evidence-based summaries in Clinical Evidence have links to major guidelines and use the GRADE Working Group approach to assess quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.36 PubMed was also searched to identify publications specifically addressing OM in Indigenous populations.

Box 2. A simple PubMed search strategy to identify evidence-based guidelines, evidence-based summaries, systematic reviews, and RCTs on otitis media and additional studies involving Indigenous children.

-

1.

“otitis”[MeSH Terms] AND (practice guideline[pt] OR systematic[sb] OR clinical evidence[jour] OR clinical trial[pt]) = 1625 hits

-

2.

“otitis”[MeSH Terms] AND (“American Native Continental Ancestry Group”[MeSH Terms] OR “Oceanic Ancestry Group”[MeSH Terms] OR “ethnic groups”[MeSH Terms] OR Inuit OR “Native American” OR Indian OR “First Nation” OR Maori OR Indig∗ OR Aborig∗) = 291 hits

-

3.

1 AND 2 = 17 hits

Results of search

The search identified over 50 evidence-based guidelines, evidence summaries, and systematic reviews (and many more additional RCTs) published since 2000. In this article, the authors have not considered interventions that have been assessed in nonrandomized studies, interventions that have been assessed in studies with less than 200 participants (sparse data),36 or studies of interventions that are only available experimentally. The simple search strategy for Indigenous studies identified 291 hits. Of these, 17 hits were also identified by the strategy to identify high-quality intervention studies. These hits included 1 systematic review and 5 RCTs. The systematic review described clinical research studies of OM in Australian Aboriginal children.38 Two RCTs addressed the effect of antibiotic prophylaxis in Alaskan Inuit children and Australian Aboriginal children.39, 40 Two of the RCTs addressed the effect of topical antibiotics for CSOM in Australian Aboriginal children.41, 42 One RCT assessed the impact of the conjugate pneumococcal vaccine on OM in Navajo and Apache children.43 Although they were not identified by a search strategy, the authors were also aware of an additional systematic review and evidence-based clinical guidelines developed specifically to assist in the care of Australian Aboriginal children with OM.44, 45

Burden of otitis media

Otitis media (OM) is an acute upper respiratory tract infection that affects the respiratory mucosa of the middle ear cleft. OM is a common illness in young children (and occurs much less frequently in children >6 years).24, 46 In developed countries, OM is the commonest indication for antibiotic prescribing and surgery in young children. In the United States, annual costs were estimated to be $3 to $5 billion in the 1990s.46 The costs per capita are likely to be considerably greater in high-risk populations.

Common types of otitis media

Otitis media is best regarded as a spectrum of disease. The most important conditions are OME, acute otitis media without perforation (AOMwoP), acute otitis media with perforation (AOMwiP), and CSOM. OME is usually the mildest form of the disease and CSOM the most severe. Children who end up with CSOM usually progress through the stages of OME, AOM without perforation, AOM with perforation, and finally to CSOM. Unfortunately, there is currently a lack of consistency in definitions of different forms of OM (especially AOM).47 This can lead to confusion when you need to describe the progress of a child over time.

OME is usually defined as the presence of a middle ear effusion without symptoms or signs of an acute infection. OME is by far the most common form of OM in all populations. Brief periods of OME (often in association with upper respiratory tract infections) should be regarded as a normal phenomenon in early childhood.

AOM is usually defined as the presence of a middle ear effusion plus the presence of the symptoms (especially pain) or signs (especially bulging of the tympanic membrane or fresh discharge). The diagnostic criteria used in studies of AOM vary. Some use symptomatic criteria, some use otoscopic criteria, and some require both symptomatic and otoscopic criteria to be met.

CSOM is usually defined as discharge through a perforated tympanic membrane for greater than 2 to 6 weeks. If the duration of the discharge is uncertain, perforations that are easily visible (covering >2% of the tympanic membrane) are more likely to be associated with CSOM.

Children with immunodeficiency or craniofacial abnormalities (cleft palate, Down syndrome, and so forth) are at increased risk of OM. Other risk factors that have been identified in epidemiologic studies include recent respiratory infection, family history, siblings, child care attendance, lack of breast feeding, passive smoke exposure, and use of a pacifier.48

Features of otitis media in indigenous populations

High rates of severe otitis media have been described in Indigenous children for over 40 years. The first publication identified by the authors' search was published in 1960,49 and publications have appeared regularly from 1965 on.50 In the recent past, Indigenous children from the United States, Canada, Northern Europe, Australia, and New Zealand have all been affected.51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60 The rates of tympanic membrane perforation in these populations remain among the highest ever described in the medical literature.61 Many investigators have puzzled over the high rates of severe disease and wondered whether ear discharge was a new illness that occurred during the transition from a nomadic lifestyle typical of many of these Indigenous groups. The search reported here did not identify any studies that were able to answer this question.

The rates of tympanic membrane perforation vary enormously, even with Indigenous groups within the same region. Furthermore, discharging ears as described in Indigenous children (“the running ear are the heritage of the poor”)62 were common in disadvantaged children living in developed countries in the pre-antibiotic era.63 For these reasons, the authors believe the most important underlying causes of severe ear infections are likely to be environmental. Indigenous populations at high risk of severe OM also have high rates of rhinosinusitis, bronchitis, pneumonia, invasive pneumococcal disease, and chronic suppurative lung disease (including bronchiectasis).64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71 It is likely that the same risk factors contribute to the excessive frequency of all of these conditions.

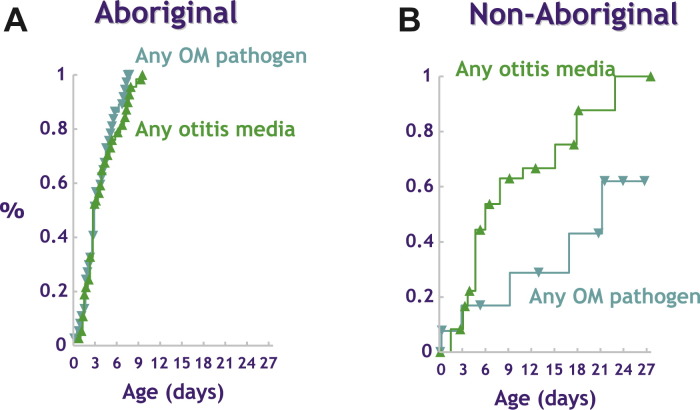

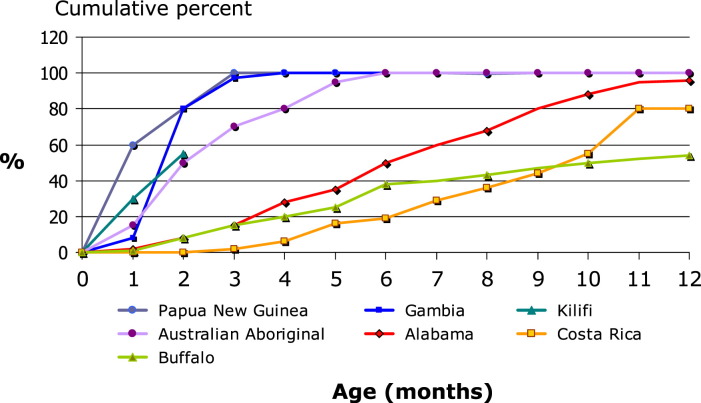

Early exposure to otitis media pathogens has been demonstrated in Australian Aboriginal infants, and this is the most important determinant of subsequent OM (Fig. 1 ).72, 73, 74 Of importance is that in this high-risk population, children usually have multiple pathogens (and often multiple types of each pathogen) and their total bacterial load is high. International comparisons show that a similar early onset of carriage of the pneumococcus is seen in other populations with high rates of invasive pneumococcal disease (Fig. 2 ).75

Fig. 1.

Bacterial colonization of the nasopharynx with pneumococcus, nontypable Haemophilus influenzae, or Moraxella catarrhalis predicts early onset of persistent otitis media in Aboriginal infants. (From Leach AJ, Boswell JB, Asche V, et al. Bacterial colonization of the nasopharynx predicts very early onset and persistence of otitis media in Australian aboriginal infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1994;13(11):983–9; with permission.)

Fig. 2.

Time to acquisition of pneumococcus in the nasopharynx of infants enrolled in birth cohort studies. (Adapted from O'Brien KL, Nohynek H. Report from a WHO Working Group: standard method for detecting upper respiratory carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003;22(2):e1–11; with permission.)

Although genetic factors are known to contribute to the risk of OM, their importance in high-risk populations has not been determined. Some investigators have proposed that genetic susceptibility is linked to poor Eustachian tube function.52 However, this does not explain the associated high rates of other bacterial respiratory infection.

Diagnosis of otitis media

Children with OM will usually present with features related to either: (i) pain and fever (AOM); (ii) hearing loss (OME); or (iii) ear discharge (AOM with perforation or CSOM). In some children, OM will be detected as part of a routine examination. Making an accurate diagnosis is not easy. In general it requires a good view of the whole tympanic membrane, and the use of either pneumatic otoscopy or tympanometry (to confirm the presence of a middle ear effusion).47, 76 Studies of diagnostic accuracy in AOM have found ear pain to be the most useful symptom (but not very reliable on it is own). Presence of bulging, opacity, and immobility of the tympanic membrane are all highly predictive of AOM. Normal (pearly gray) color of the tympanic membrane makes AOM unlikely.77

Otitis media with effusion

The commonest form of OM is OME. The point prevalence in screening studies is around 20% in young children.46 OME can occur spontaneously, as part of rhinosinusitis, or following an episode of AOM. The same respiratory bacterial pathogens associated with AOM have been implicated in the pathogenesis. Most children with OME will improve spontaneously within 3 months, and complications from this illness are uncommon.46 The average hearing loss associated with OME is around 25 dB.46 Despite large numbers of studies, a causal relationship between OME and speech and language delay has not been proven.27, 78

Acute otitis media

Most children will experience at least one episode of AOM.46 The peak incidence of infection occurs between 6 and 12 months. Although the pathogenesis of AOM is multifactorial, both viruses and bacteria are implicated.46 Bacterial infection with the common respiratory pathogens (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis) is often preceded by a viral infection. Viruses (especially respiratory syncytial virus and influenza) can cause AOM without coinfection with bacteria.46 The pain associated with AOM resolves within 24 hours in around 60% and within 3 days in around 80%.24 Young children with AOM (<2 years) are less likely to experience spontaneous resolution.22 Complications of AOM include CSOM, mastoiditis, labyrinthitis, facial palsy, meningitis, intracranial abscess, and lateral sinus thrombosis.27 Mastoiditis was the most common life-threatening complication in the pre-antibiotic era. Mastoiditis occurred in 18% of children admitted to hospital with AOM in one study.23 Mastoiditis (and all other complications) is now rare in developed countries.

Chronic suppurative otitis media

CSOM is the most severe form of OM.79 Although there is a lack of well-designed longitudinal studies, CSOM is the type of OM most likely to persist without treatment. In developing countries, CSOM occurs as a complication of AOM with perforation and can be a major health issue. The range of bacterial pathogens associated with CSOM is considerably broader than those seen in AOM. Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, Proteus, and Klebsiella species are most commonly isolated, and mixed infections are common.79 Multidrug antibiotic resistance is often seen in Pseudomonas infections. The associated hearing loss is usually more than that seen in OME (and CSOM represents the most important cause of moderate conductive hearing loss [>40dB] in many developing countries).31

In developed countries, CSOM is now very uncommon. A recent risk factor study in the Netherlands found that most cases of CSOM are now occurring as a complication of tympanostomy tubes insertion.80 Children with immunodeficiency and some Indigenous populations are also at greatly increased risk. In rural and remote communities in northern Australia, more than 20% of young children are affected.71

Options for interventions: otitis media with effusion

OME affects all children but is usually asymptomatic.46 A small proportion of children have persistent OME with associated hearing loss. There is evidence on the effects of screening to identify young children with OME (or hearing loss associated with OME), and this is not effective in developed countries.81 There is also evidence on treatment effects of antibiotics, insertion of tympanostomy tubes, autoinflation devices, antihistamines and decongestants, and antibiotics plus steroids (see Table 3).14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 82 Of these interventions, early insertion of tympanostomy tubes (compared with watchful waiting and option of insertion later) is proven to improve hearing at 6 and 12 months, but the beneficial effect is modest.14, 15, 16 This improvement in hearing has not been associated with improvement in language development or cognitive assessment scores.16 Tympanostomy tubes usually last 6 to 12 months, and there is no evidence that there is any ongoing benefit after they have been extruded. Antibiotics have also been shown to be an effective treatment, but the beneficial effects are slight and do not seem to persist over the long term.14, 15, 27 There seem to be additional short-term benefits when antibiotics are combined with steroids, but again the beneficial effect is modest.14, 20 There is some evidence that autoinflation devices are effective.14, 19 The benefits are modest and have only been documented to be short term. Antihistamines and decongestants provide no benefit (see Table 3).14, 15, 18

Given the available evidence from RCTs on OME, most well-informed individuals in low-risk populations would choose a course of watchful waiting initially. For those children with persistent OME in both ears associated with hearing loss despite watching and waiting for 6 to 12 months, a trial of antibiotics is reasonable. Insertion of tympanostomy tubes is most appropriate in children for whom the primary concern is the conductive hearing loss and communication difficulties. Children with the most severe conductive hearing loss are most likely to benefit. Families should be informed that a small proportion of children will suffer recurrent persistent OME when the tympanostomy tubes are extruded, and may need a second operation. In these children, tympanostomy tubes plus adenoidectomy is a reasonable option.14, 82

Children who experience frequent suppurative infections (including those with immunodeficiency or persistent bacterial rhinosinusitis) are at greatest risk of developing CSOM as a complication of tympanostomy tubes. Indigenous children in high-risk populations would fall into this group.

None of the RCTs assessing interventions for OME were conducted with Indigenous children. However, one RCT of prophylactic antibiotics in Australian Aboriginal children enrolled only infants with OME. None of the children in the placebo group had resolution of their OME within 6 months. Around 10% of children in the antibiotic group had resolution of their OME.40 This result suggests that OME is a persistent condition that does not respond well to established treatment options. Although no reliable evidence from RCTs was found, strategies that aim to improve hearing and communication in those with moderate hearing loss might provide most benefit in high-risk populations.

Although not a primary outcome measure, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine reduced the number of children who received tympanostomy tube insertion by around 20%. It is possible that some of this effect was mediated through a reduction in chronic bilateral OME with hearing loss. Consistent with this, substantial declines in this procedure have been described in the United States in recent years, but not amongst Alaskan Native children.83

Options for interventions: acute otitis media

Most children with AOM will improve spontaneously within 14 days, and complications from this illness are uncommon. When considering the onset of the illness, there is evidence on the preventive effects of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and influenza vaccine (see Table 3).11, 12, 13, 24 Both of these vaccines have been shown to be effective, but the beneficial effects in terms of overall rates of infection are slight. The beneficial effects of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine are modest in terms of reductions in the insertion of tympanostomy tubes.84 Most children in low-risk populations will not meet the criteria for tympanostomy tube insertion. There is also evidence on the treatment effects of antihistamines and decongestants, antibiotics, myringotomy, and analgesics (see Table 3).21, 23, 24, 25, 27 Regular analgesics (paracetamol or ibuprofen) provide a benefit (assessment on day 2), and the beneficial effects were large.24 Antibiotics are also proven to be effective.22, 23 The short-term beneficial effects are slight in most children. The beneficial effects are modest in children younger than 2 years with bilateral AOM, and large in those with AOM with perforation. Studies of initial treatment with antibiotics have not documented a long-term effect. If antibiotics are to be used, there is evidence that a longer course of treatment (≥7 days) is more effective but the beneficial effects are modest (persistent AOM reduced from 22% to 15%).85 There is no evidence to support the belief that any one of the commonly used antibiotics is more effective than the others. The use of antihistamines and decongestants has not been shown to be beneficial, and myringotomy seems to be harmful compared with no treatment or antibiotics (see Table 3).21, 24, 27

Given the available evidence from RCTs on AOM, most well-informed individuals in low-risk populations would choose symptomatic relief with analgesics and either watchful waiting or antibiotics. Antibiotics would be most appropriate in children younger than 2 years with bilateral AOM, those with AOM with perforation, children with high risk of complications, and those who have already had 48 hours of watchful waiting.

If the child is not in a high-risk group but the family prefers antibiotic treatment, the clinician should discuss “wait and see prescribing.” Provision of a script for antibiotic along with advice only to use it if the pain persists 48 hours will reduce antibiotic use by two-thirds (with no negative impact on family satisfaction).86, 87, 88

A small proportion of children with AOM will experience recurrent AOM (3 episodes in 6 months or 4 episodes within 12 months).46 There is evidence on the treatment effects of prophylactic antibiotics, adenoidectomy, and tympanostomy tube insertion.24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 Antibiotics are proven to be effective but the beneficial effects are modest. The rates of AOM also reduce spontaneously without treatment so that absolute benefits are less impressive than anticipated. Two of the RCTs assessing prophylactic antibiotics have been conducted in Indigenous children.39, 40 These studies demonstrate that prophylactic antibiotics will prevent perforation of the tympanic membrane. The size of the benefit is similar to prevention of any AOM. Insertion of tympanostomy tubes also seems to reduce rates of AOM, and the effect is similar to antibiotics. Either of these options could be considered in those children from low-risk populations with very frequent infections (especially if occurring before the peak of respiratory illness in winter). However, children with tympanostomy tubes may develop a discharging ear, so this is not a good option in children at increased risk of suppurative infections (including those with immunodeficiency or persistent bacterial rhinosinusitis). For Indigenous children in high-risk populations, prophylactic antibiotics or prompt antibiotic treatment of infections are probably the more appropriate treatment options. Adenoidectomy does not seem to be an effective treatment.27, 28, 29

Because Indigenous children in high-risk populations are known to have high rates of pneumococcal diseases, there was hope that introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine would have a greater impact on OM in these populations. One RCT in Navajo and Apache children assessed the impact on OM and could not demonstrate substantially improved outcomes.43 Of note, comparison of longitudinal cohorts before and after the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine found a reduction in OM visits for American Indian children but not for Alaskan Native children.83 In Australia, comparison of longitudinal cohorts of Aboriginal infants before and after the introduction of the vaccine did not document substantial reductions in severe OM.43, 89

Options for interventions: chronic suppurative otitis media

A small proportion of children with AOM with perforation go on to develop CSOM. In developed countries, CSOM most commonly occurs as a complication of tympanostomy tube placement. There is evidence on the treatment effects of topical antibiotics, topical antiseptics, systemic antibiotics, and ear cleaning.31, 32, 33, 34, 79 Interpretation of a large number of small studies is challenging, but topical antibiotics are proven to be effective and the beneficial effects vary from large to modest. Most studies have not documented a long-term effect. Topical antibiotics also seem to be more effective than antiseptics and systemic antibiotics.31 The role of topical antibiotics plus systematic antibiotics is unclear.90 Cleaning the middle ear discharge has not been proven to be effective in RCTs but is generally regarded as necessary before insertion of topical antibiotics (at least in children with profuse discharge). Although not seen in RCTs, there is also a very small risk of ototoxicity associated with most topical antibiotics (except topical quinolones) and topical antiseptics.27 For children who fail to respond to prolonged courses of topical antibiotics, 2 small studies (85 participants) have documented high cure rates and large beneficial effects associated with 2 to 3 weeks of intravenous antipseudomonal antibiotics (such as ceftazidime).91, 92

Given the available evidence from RCTs on CSOM, most well-informed individuals would choose topical antibiotic treatment. However, even though this is an effective treatment, prolonged or repeated courses of treatment are often required. If this is the case, topical quinolones will provide a slight benefit in terms of risk of ototoxicity. Even in high-risk Indigenous populations there is a considerable difference in the likely response to treatment. Two RCTs comparing ciprofloxacin drops with framycetin-gramycidin-dexamethasone drops in Australian Aboriginal children with CSOM have been conducted. One trial found most children could be effectively treated within 9 days, whereas the other reported most children with persistent CSOM despite 6 weeks of treatment.41, 42

Although not the subject of RCTs, the outcomes of tympanoplasty in Indigenous children and adults have been described. These studies usually report effective surgical repair of the tympanic membrane in around 50% to 70% and a modest improvement in hearing.57, 93, 94 These results are not as good as those seen in other populations, where effective repair is usually achieved in 80% to 90%. This operation is probably most appropriate for Indigenous children with bilateral large, dry tympanic membrane perforations associated with a moderate hearing loss or frequent episodes of discharge.

Summary

OM is one of the most common illnesses affecting children. In low-risk populations, most illnesses are mild and will resolve completely without specific treatment. Unfortunately, this is not always the case for Indigenous children in high-risk populations. Multiple interventions have been assessed in the treatment of OM. None of the interventions have had substantial absolute benefits for the populations studied. Therefore, for low-risk children symptomatic relief and watchful waiting (including education of the parents about important danger signs) is the most appropriate treatment option. Antibiotics have a role in children with persistent bacterial infection, or those at risk of complications. Even today, many Indigenous children will often fall into these high-risk groups.

References

- 1.Monto A.S. Epidemiology of viral respiratory infections. Am J Med. 2002;112(Suppl 6A):4S–12S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heikkinen T., Jarvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12162-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bluestone C.D., Klein J.O. 4th edition. W.B. Saunders Company; Philadelphia: 2007. Otitis media in infants and children. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson W.E. In: Textbook of pediatrics. 15th edition. Nelson W.E., Behman R.E., Kliegman R.M., editors. W.B. Saunders Company; Philadelphia: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Revai K., Dobbs L.A., Nair S. Incidence of acute otitis media and sinusitis complicating upper respiratory tract infection: the effect of age. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):e1408–e1412. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irwig L., Irwig J., Sweet M. Hammersmith Press; Sydney: 2007. Smart health choices: making sense of health advice. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altman D.G., Bland J.M. Statistics notes. Treatment allocation in controlled trials: why randomise? BMJ. 1999;318(7192):1209. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7192.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atkins D., Best D., Briss P.A. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guyatt G.H., Oxman A.D., Vist G.E. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atkins D., Briss P.A., Eccles M. Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations II: pilot study of a new system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;51:25. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Straetemans M., Sanders E.A., Veenhoven R.H. Pneumococcal vaccines for preventing otitis media. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001480.pub2. CD001480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jefferson T., Rivetti A., Harnden A. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004879.pub3. CD004879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manzoli L., Schioppa F., Boccia A. The efficacy of influenza vaccine for healthy children: a meta-analysis evaluating potential sources of variation in efficacy estimates including study quality. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(2):97–106. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000253053.01151.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williamson I. Otitis media with effusion. Clin Evid. 2006;15:814–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Otitis Media With Effusion Otitis media with effusion. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1412–1429. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lous J., Burton M.J., Felding J.U. Grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001801.pub2. CD001801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rovers M.M., Black N., Browning G.G. Grommets in otitis media with effusion: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(5):480–485. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.059444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin G.H., Flynn C., Bailey R.E. Antihistamines and/or decongestants for otitis media with effusion (OME) in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003423.pub2. CD003423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perera R., Haynes J., Glasziou P. Autoinflation for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006285. CD006285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas C.L., Simpson S., Butler C.C. Oral or topical nasal steroids for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001935.pub2. CD001935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flynn C.A., Griffin G.H., Schultz J.K. Decongestants and antihistamines for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001727.pub2. CD001727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rovers M.M., Glasziou P., Appelman C.L. Antibiotics for acute otitis media: a meta-analysis with individual patient data. Lancet. 2006;368(9545):1429–1435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasziou P.P., Del Mar C.B., Sanders S.L. Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000219.pub2. CD000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Neill P., Roberts T., Bradley S.C. Otitis media in children (acute) Clin Evid. 2006;15:500–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertin L., Pons G., d'Athis P. A randomized, double-blind, multicentre controlled trial of ibuprofen versus acetaminophen and placebo for symptoms of acute otitis media in children. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1996;10(4):387–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1996.tb00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leach A.J., Morris P.S. Antibiotics for the prevention of acute and chronic suppurative otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004401.pub2. CD004401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenfeld R.M., Bluestone C.D. B.C. Decker Inc; Hamilton: 2003. Evidence-based otitis media. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mattila P.S., Joki-Erkkila V.P., Kilpi T. Prevention of otitis media by adenoidectomy in children younger than 2 years. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(2):163–168. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammaren-Malmi S., Saxen H., Tarkkanen J. Adenoidectomy does not significantly reduce the incidence of otitis media in conjunction with the insertion of tympanostomy tubes in children who are younger than 4 years: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):185–189. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonald S., Langton Hewer C.D., Nunez D.A. Grommets (ventilation tubes) for recurrent acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004741.pub2. CD004741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acuin J. Chronic suppurative otitis media. Clin Evid. 2006;15:772–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macfadyen C.A., Acuin J.M., Gamble C. Topical antibiotics without steroids for chronically discharging ears with underlying eardrum perforations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004618.pub2. CD004618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macfadyen C.A., Acuin J.M., Gamble C. Systemic antibiotics versus topical treatments for chronically discharging ears with underlying eardrum perforations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005608. CD005608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Acuin J., Smith A., Mackenzie I. Interventions for chronic suppurative otitis media. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000473. CD000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Report of a WHO/CIBA Foundation Workshop . World Health Organisation; Geneva: 1996. Prevention of hearing impairment from chronic otitis media. [Google Scholar]

- 36.BMJ Publishing Group; London: 2009. Clinical evidence. Issue 1. [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Cochrane Library . Wiley interScience; Oxford: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris P.S. A systematic review of clinical research addressing the prevalence, aetiology, diagnosis, prognosis and therapy of otitis media in Australian Aboriginal children. J Paediatr Child Health. 1998;34(6):487–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1998.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maynard J.E., Fleshman J.K., Tschopp C.F. Otitis media in Alaskan Eskimo children. Prospective evaluation of chemoprophylaxis. JAMA. 1972;219(5):597–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leach A.J., Morris P.S., Mathews J.D. Compared to placebo, long-term antibiotics resolve otitis media with effusion (OME) and prevent acute otitis media with perforation (AOMwiP) in a high-risk population: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2008;8(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Couzos S., Lea T., Mueller R. Effectiveness of ototopical antibiotics for chronic suppurative otitis media in Aboriginal children: a community-based, multicentre, double-blind randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2003;179(4):185–190. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leach A., Wood Y., Gadil E. Topical ciprofloxin versus topical framycetin-gramicidin-dexamethasone in Australian aboriginal children with recently treated chronic suppurative otitis media: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(8):692–698. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31816fca9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Brien K.L., David A.B., Chandran A. Randomized, controlled trial efficacy of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against otitis media among Navajo and White Mountain Apache infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(1):71–73. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318159228f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Couzos S., Metcalf S., Murray R. Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health; Canberra: 2001. Systematic review of existing evidence and primary care guidelines on the management of otitis media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morris P., Ballinger D., Leach A. Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health; Canberra: 2001. Recommendations for clinical care guidelines on the management of otitis media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rovers M.M., Schilder A.G., Zielhuis G.A. Otitis media. Lancet. 2004;363(9407):465–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis Media Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1451–1465. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uhari M., Mantysaari K., Niemela M. A meta-analytic review of the risk factors for acute otitis media. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22(6):1079–1083. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.1079. [see comments] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ensign P.R., Urbanich E.M., Moran M. Prophylaxis for otitis media in an Indian population. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1960;50:195–199. doi: 10.2105/ajph.50.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brody A. Draining ears and deafness among Alaskan Eskimos. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1965;81:29–33. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1965.00750050034009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiet R.J. Patterns of ear disease in the southwestern American Indian. Arch Otolaryngol. 1979;105(7):381–385. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1979.00790190007002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beery Q.C., Doyle W.J., Cantekin E.I. Eustachian tube function in an American Indian population. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1980;89(3 Pt 2):28–33. doi: 10.1177/00034894800890s310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Daly K.A., Pirie P.L., Rhodes K.L. Early otitis media among Minnesota American Indians: the little ears study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(2):317–322. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.052837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baxter J.D. An overview of twenty years of observation concerning etiology, prevalence, and evolution of otitis media and hearing loss among the Inuit in the eastern Canadian Arctic. Arctic Med Res. 1991;(Suppl):616–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Homoe P., Prag J., Farholt S. High rate of nasopharyngeal carriage of potential pathogens among children in Greenland: results of a clinical survey of middle-ear disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(5):1081–1090. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.5.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Homoe P., Christensen R.B., Bretlau P. Prevalence of otitis media in a survey of 591 unselected Greenlandic children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;36(3):215–230. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(96)01351-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Homoe P., Siim C., Bretlau P. Outcome of mobile ear surgery for chronic otitis media in remote areas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(1):55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leach A.J. Otitis media in Australian Aboriginal children: an overview. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1999;49(Suppl 1):S173–S178. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(99)00156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giles M., O'Brien P. The prevalence of hearing impairment amongst Maori schoolchildren. Clin Otolaryngol. 1991;16(2):174–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1991.tb01971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Giles M., Asher I. Prevalence and natural history of otitis media with perforation in Maori school children. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105(4):257–260. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100115555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bluestone C.D. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of chronic suppurative otitis media: implications for prevention and treatment. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1998;42(3):207–223. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(97)00147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cambon K., Galbraith J.D., Kong G. Middle-ear disease in Indians of the Mount Currie Reservation, British Columbia. Can Med Assoc J. 1965;93(25):1301–1305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miller F.J. Childhood morbidity and mortality in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne. Further report on the thousand family study. N Engl J Med. 1966;275(13):683–690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196609292751301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fleshman J.K., Wilson J.F., Cohen J.J. Bronchiectasis in Alaska Native children. Arch Environ Health. 1968;17(4):517–523. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1968.10665274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baxter J.D. Otitis media in Inuit children in the Eastern Canadian Arctic—an overview 1968 to date. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1999;49(Suppl 1):S165–S168. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(99)00154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Singleton R., Morris A., Redding G. Bronchiectasis in Alaska Native children: causes and clinical courses. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;29(3):182–187. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(200003)29:3<182::aid-ppul5>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Peck A.J., Holman R.C., Curns A.T. Lower respiratory tract infections among American Indian and Alaska Native children and the general population of U.S. children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(4):342–351. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000157250.95880.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singleton R.J., Hennessy T.W., Bulkow L.R. Invasive pneumococcal disease caused by nonvaccine serotypes among Alaska native children with high levels of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine coverage. JAMA. 2007;297(16):1784–1792. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.16.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Torzillo P.J., Hanna J.N., Morey F. Invasive pneumococcal disease in central Australia. Med J Aust. 1995;162(4):182–186. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb126016a.x. [see comments] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chang A.B., Grimwood K., Mulholland E.K. Bronchiectasis in indigenous children in remote Australian communities. Med J Aust. 2002;177(4):200–204. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leach A.J., Morris P.S. The burden and outcome of respiratory tract infection in Australian and aboriginal children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(10 suppl):S4–S7. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318154b238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leach A.J., Boswell J.B., Asche V. Bacterial colonization of the nasopharynx predicts very early onset and persistence of otitis media in Australian aboriginal infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13(11):983–989. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199411000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith-Vaughan H.C., Leach A.J., Shelby J.T. Carriage of multiple ribotypes of nonencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae in aboriginal infants with otitis media. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;116(2):177–183. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800052419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith-Vaughan H., Byun R., Nadkarni M. Measuring nasal bacterial load and its association with otitis media. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2006;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6815-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.O'Brien K.L., Nohynek H. Report from a WHO working group: standard method for detecting upper respiratory carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(2):e1–e11. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000049347.42983.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Takata G.S., Chan L.S., Morphew T. Evidence assessment of the accuracy of methods of diagnosing middle ear effusion in children with otitis media with effusion. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6 Pt 1):1379–1387. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rothman R., Owens T., Simel D.L. Does this child have acute otitis media? JAMA. 2003;290(12):1633–1640. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roberts J.E., Rosenfeld R.M., Zeisel S.A. Otitis media and speech and language: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):e238–e248. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.e238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Verhoeff M., van der Veen E.L., Rovers M.M. Chronic suppurative otitis media: a review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van der Veen E.L., Schilder A.G., van Heerbeek N. Predictors of chronic suppurative otitis media in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(10):1115–1118. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.10.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Simpson S.A., Thomas C.L., van der Linden M.K. Identification of children in the first four years of life for early treatment for otitis media with effusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004163.pub2. CD004163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rosenfeld R.M. Surgical prevention of otitis media. Vaccine. 2000;19(Suppl 1):S134–S139. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Singleton R.J., Holman R.C., Plant R. Trends in otitis media and myringtomy with tube placement among American Indian/Alaska native children and the US general population of children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(2):102–107. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318188d079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fireman B., Black S.B., Shinefield H.R. Impact of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(1):10–16. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kozyrskyj A.L., Hildes-Ripstein G.E., Longstaffe S.E. Short course antibiotics for acute otitis media. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001095. CD001095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Spurling G.K., Del Mar C.B., Dooley L. Delayed antibiotics for respiratory infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004417.pub3. CD004417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spiro D.M., Tay K.Y., Arnold D.H. Wait-and-see prescription for the treatment of acute otitis media: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296(10):1235–1241. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.10.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Little P., Gould C., Williamson I. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of two prescribing strategies for childhood acute otitis media. BMJ. 2001;322(7282):336–342. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7282.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mackenzie G.A., Carapetis J.R., Leach A.J. Pneumococcal vaccination and otitis media in Australian Aboriginal infants: comparison of two birth cohorts before and after introduction of vaccination. BMC Pediatr. 2009;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.van der Veen E.L., Rovers M.M., Albers F.W. Effectiveness of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for children with chronic active otitis media: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):897–904. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leiberman A., Fliss D.M., Dagan R. Medical treatment of chronic suppurative otitis media without cholesteatoma in children—a two-year follow-up. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1992;24(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(92)90063-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dagan R., Fliss D.M., Einhorn M. Outpatient management of chronic suppurative otitis media without cholesteatoma in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11(7):542–546. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mak D., MacKendrick A., Bulsara M. Outcomes of myringoplasty in Australian Aboriginal children and factors associated with success: a prospective case series. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004;29(6):606–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Guerin N., McConnell F. Myringoplasty: a post-operative survey of 90 aborigine patients. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 1988;109(2):123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]