Abstract

The present “obesogenic’ environment has favored excessive energy intake resulting in the current obesity epidemic and its associated diseases. The epidemic has incentivized scientists to develop novel behavioral and pharmacological strategies that enhance energy expenditure to compensate for excessive energy intake. Although physical activity is effective to increase total energy expenditure, it is insufficient to induce negative energy balance and weight loss. With the discovery of brown adipose tissue (BAT) in adult humans, BAT activation soon emerged as a potential strategy for elevating energy expenditure. BAT is the only tissue that expresses uncoupling protein 1, conferring on this tissue high thermogenic capacity due to a low efficiency for mitochondrial ATP generation. Potential manipulation of BAT mass and activity has fueled the interest in altering whole-body energy balance through increased energy expenditure. Remarkable advances have been made in quantifying the amount and activity of BAT in humans. Many studies have concluded that the amount of active BAT appears insufficient to induce meaningful increases in energy expenditure. Thus, the majority of studies report that BAT activation does not influence body weight and metabolic control in humans. Strategies to increase BAT mass and/or to potentiate BAT activity seem necessary.

Keywords: Thermogenesis, Obesity, Cold exposure, Glucose homeostasis, Lipid homeostasis

1. Introduction

Affluent societies have been exposed to an excess of palatable, cheap and energy-dense foods. Evidence suggests that this surplus of food mostly explains the positive energy balance that leads to excess body weight (Swinburn et al., 2011). This idea is supported by the association between the increased energy supply and the rise of average body weight worldwide (Vandevijvere et al., 2015). Mathematical modeling shows that the excessive energy supply suffices to explain the rising obesity levels, even without needing to consider lower energy expenditure (Vandevijvere et al., 2015). Indeed, physical activity levels of the population have remained stable in face of the obesity epidemic (Westerterp and Speakman, 2008).

The excessive energy intake has been hypothesized to result from the macronutrient composition of modern energy-dense food. For instance, the proportion of dietary protein has been shown to associate inversely with total energy intake (Gosby et al., 2014). As lipid and carbohydrates dilute proteins in energy-dense food, additional energy intake is required to reach satiation (the “protein leverage” hypothesis) (Simpson and Raubenheimer, 2005). Consumption of high-glycemic carbohydrates has also been hypothesized to increase energy intake by promoting increased hunger (the “carbohydrate-insulin model” hypothesis) (Ludwig and Ebbeling, 2018). Independently of the mechanism, elevated energy intake seems to be the main trigger of the obesity epidemic.

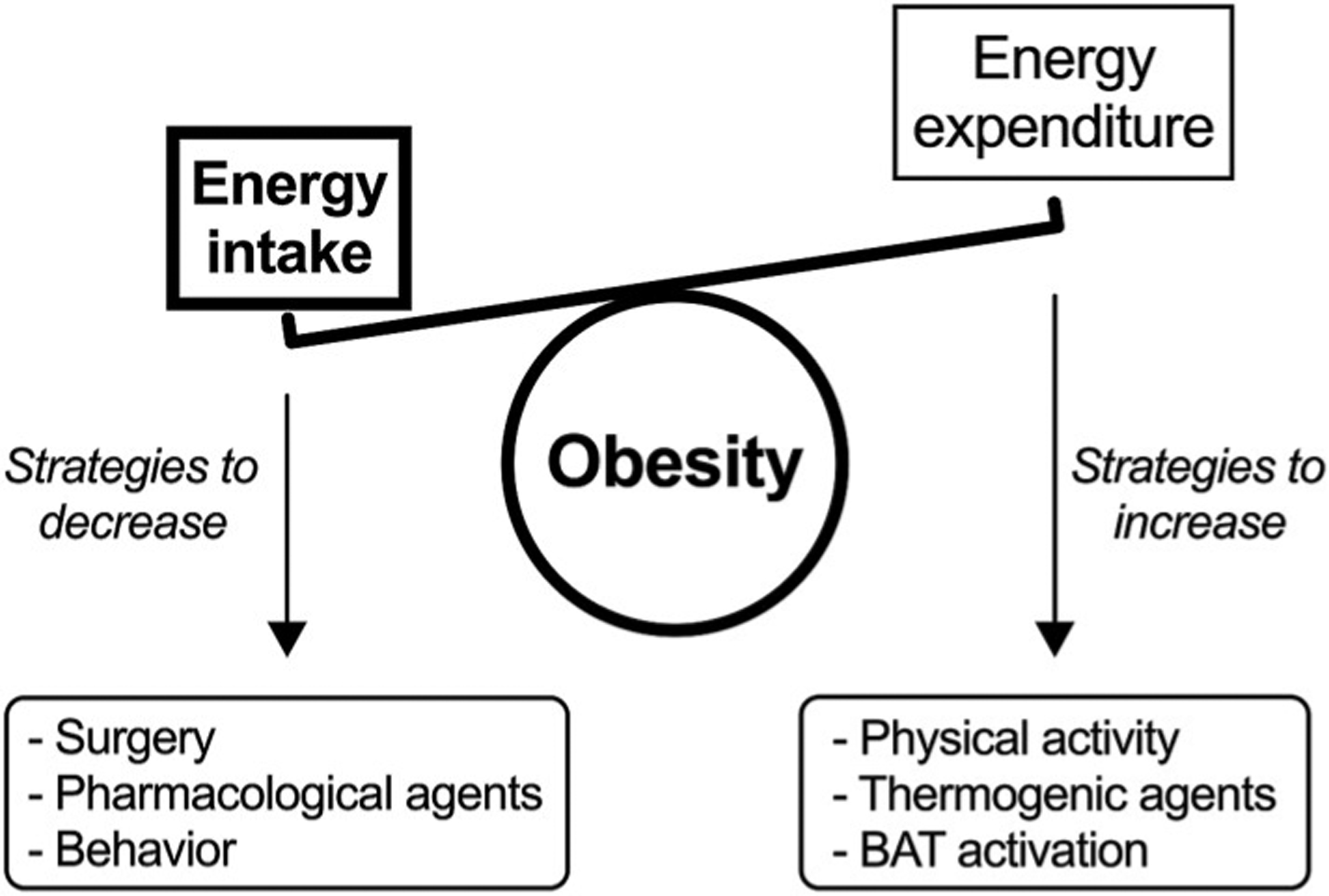

As a result, most lifestyle interventions targeting a reduction in body weight often focus on decreasing energy intake (Fig. 1). The extreme approach is the surgical intervention of the digestive tract (i.e. bariatric surgery), which has proven very efficacious especially when coupled with lifestyle interventions (Schauer et al., 2017). Despite these efforts, individuals regularly resume their previous feeding behaviors and therefore fail to successfully control body weight. Another strategy to reduce body weight is to increase energy expenditure through physical activity and/or by using thermogenic compounds (e.g. pharmacologic agents, food ingredients) (Fig. 1). Unfortunately, these strategies are often plagued by poor adherence to exercise, compensatory increases in energy intake, and/or increases in sedentary behavior following exercise (Burgess et al., 2017; Melanson et al., 2013). Moreover, most pharmacological agents used to increase energy expenditure are associated with unwanted side effects. Common side effects are of cardio-vascular nature, including tachycardia and increases in blood pressure. In addition, compound-specific side effects include rhabdomyolysis (phendimetrazine), diarrhea (phenmetrazine), addiction (diethylpro-pion), psychiatric symptoms (ephedra and ephedrine), and even death (2,4-dinitrophenol) (Colman, 2007; Müller et al., 2018; Shekelle et al., 2003).

Fig. 1.

Strategies used to control body weight.

In the absence of effective therapies to decrease energy intake or increase energy expenditure, brown adipose tissue (BAT) became a novel target in the treatment of human obesity (Fig. 1). The primary role of BAT is to preserve body temperature in mammals with high body surface area-to-volume ratios, including newborn infants (Silva, 2006). Specifically, BAT is characterized by high mitochondrial content and expression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). UCP1 uncouples mitochondrial ATP synthesis from fuel oxidation, resulting in most of the energy dissipated as heat (Nicholls et al., 1978). As a result, targeting the thermogenic capacity of BAT has become another avenue to enhance energy expenditure and potentially improve weight management in humans. Here, we review the evidence about the role of BAT in body weight control and obesity-related metabolic disturbances in adult humans.

2. Estimation of BAT mass

A quantitatively relevant contribution of BAT to whole-body energy expenditure and energy balance depends on the amount of BAT in the body. Consequently, accurate and precise measurement of BAT mass is critical. The gold standard technique for measuring BAT mass combines the identification of adipose tissue through X-ray computed tomography (CT) with the uptake of [18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-2-D-glucose (FDG) by positron emission tomography (PET) (Chen et al., 2016). Using this approach, adipose tissue is specifically labeled as BAT when FDG uptake is greater than the upper range observed for white adipose tissue. Although this definition seems straightforward, thresholds for both radio-density in the CT and standardized uptake value in the PET are somewhat arbitrary. Indeed, the use of different thresholds partly explains the variability in BAT mass values among studies (Blondin et al., 2015c; Martinez-Tellez et al., 2018). Increasing efforts have thus been made to standardize FDG-PET/CT BAT quantification in terms of accuracy and comparability among studies (Chen et al., 2016).

From retrospective analyses of large datasets (> 1500 patients), only ~6% of individuals are reported to have detectable BAT under the standard temperature used at medical institutions, likely around 21–24 °C (Cypess et al., 2009; Gerngroβ et al., 2017; Ouellet et al., 2011). Among individuals with detectable BAT, the amount of BAT ranged between 1 and 170 g when the cervical, supraclavicular, and superior mediastinal depots were evaluated (Cypess et al., 2009). Such inter-individual variability was partially accounted for by sex (females > males) and age (young > old). Indeed, the odds [95% confidence interval] of having detectable BAT were 3.07 [1.72–5.48] for women compared to men, and 0.32 [0.15–0.67] for the older (> 64 y-old) compared to the younger (< 50 y-old) subjects (Cypess et al., 2009). It is remarkable that reported BAT mass displayed a highly asymmetric distribution, with 75% of individuals having < 30 g of BAT (Cypess et al., 2009). If representative BAT mass values are to be reported, it is important to express them as percentiles, not as mean values.

Using this approach, Cypess et al. (2009) reported a median BAT mass of 11.6 g for men and 12.3 g for women. Retrospective studies thus suggest most individuals lack detectable levels of BAT, and when detected, BAT mass appears small. However, additional evidence indicates these BAT mass values were underestimated due to methodological issues discussed in the following paragraphs.

First, the small percentage of BAT-positive individuals is likely a consequence of the thermoneutral conditions of the measurement. Indeed, lower outdoor temperatures the day of the measurement are associated with a higher probability of BAT detection (Cypess et al., 2009; Gerngroβ et al., 2017; Ouellet et al., 2011). Current evidence suggests that BAT is detected in most, if not all, individuals after cold exposure (Blondin et al., 2015c; Leitner et al., 2017). Thus, the standard protocol for BAT determination now includes acute cold exposure, either to a fixed temperature (usually between 16 and 19 °C) or to a personalized cooling protocol that does not induce shivering (Chen et al., 2016). Secondly, each BAT-containing depot has inactive brown and beige/brite cells that may potentially become active (“brownable”) (Leitner et al., 2017). If the active and brownable tissues are considered, total BAT volume was estimated to range between 510 and 2358 ml, i.e. 459–2122 g assuming a density of 0.90 g/ml (Leitner et al., 2017). But activating brownable cells may be difficult. Indeed, brownable tissue remained inactive even after 5 h of cold exposure at a personalized lowest tolerable non-shivering temperature (~21 °C on average) (Leitner et al., 2017). While long-term cold exposure may be needed to fully activate brown and beige/brite adipocytes, administering longer cold exposure in humans may not be clinically feasible.

Another reason of BAT mass underestimation is because not all BAT depots are often quantified. In humans, BAT is found in cervical, supraclavicular, axillary, perispinal, mediastinal, and suprarenal depots. While the supraclavicular depot accounts for most detectable BAT, the addition of the cervical and axillary depots is thought to represent around two-thirds of active BAT mass (Leitner et al., 2017). Lastly, BAT mass may be underestimated in the presence of insulin resistance and aging. Insulin resistance was found to be positively associated with BAT triglyceride content (Raiko et al., 2015), while BAT triglyceride content was found to be inversely associated with FDG uptake (Baba et al., 2010). Low BAT mass detection in individuals with insulin resistance may thus be partly explained by reduced FDG uptake in BAT (Chondronikola et al., 2014; Orava et al., 2013). Older individuals also have lower cold-induced FDG uptake per volume of BAT compared to younger individuals (Blondin et al., 2015a). Then, BAT mass estimation through FDG uptake may result in underestimation of BAT mass in older individuals. The fact that cold-induced oxidative metabolism in BAT is independent of age (Blondin et al., 2015a) indicates that FDG uptake does not reflect BAT metabolic activity, at least when old vs. young individuals are compared (Blondin et al., 2015a). Indeed, BAT thermogenesis is mainly driven by intracellular triglyceride utilization (Blondin et al., 2017b, 2014), which is not associated with age (Blondin et al., 2015a).

Therefore, a bulk of evidence suggests that all humans have BAT mass, and at higher levels than initially presumed. Efforts to manipulate BAT mass/activity to influence body weight and metabolic control have therefore persisted. Thus, several markers for estimating BAT activity have been used, which are discussed in section 3. However, whether BAT activation influences body weight and metabolic control will depend on how strong the activation is, and on how long the activation is maintained. Sections 4 and 5 present the evidence regarding the effects of BAT activation on body weight and metabolic control.

3. Estimation of BAT activity

Several protocols of acute cold exposure aimed at activating BAT have been used, such as staying at cold room temperatures, wearing suits perfused with cold water, placing feet intermittently into cold water or on ice, and using blankets perfused with cold water (Table 1). In response to these protocols, studies have demonstrated that BAT increases its blood flow (Blondin et al., 2017b; Muzik et al., 2013; Orava et al., 2013; U Din et al., 2018, 2016; Weir et al., 2018), glucose uptake (Cypess et al., 2012; Orava et al., 2013; Virtanen et al., 2009; Weir et al., 2018), non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) uptake (U Din et al., 2018, 2016), metabolic rate (Blondin et al., 2017b, 2015b; Ouellet et al., 2012), oxygen consumption (Muzik et al., 2013; U Din et al., 2018, 2016) and heat production (Koskensalo et al., 2017). As a result, all these markers have been used to quantify BAT metabolic activity. Whether all of them are equally effective at accurately measuring BAT metabolic activity is debatable. For instance, cold exposure through wearing a suit perfused with cold water for 90–120 min increased BAT metabolic rate by ~4.4 fold, whereas blood flow only increased by 1.6 fold (Blondin et al., 2017b). Administration of nicotinic acid (which inhibits triglyceride lipolysis) blunted this cold-induced increase in BAT metabolic rate, yet blood flow appeared to be unaffected (Blondin et al., 2017b). Using the same cold exposure protocol, FDG uptake in BAT was observed to be lower in old versus young individuals, while NEFA uptake was similar (Blondin et al., 2015a). Collectively, these data suggest that estimates of BAT activity may sometimes dissociate (Table 1), indicating that different conclusions could be obtained depending on the specific metabolic marker used.

Table 1.

Protocols for acute cold-induced activation of brown adipose tissue (BAT) in humans.

| Protocol | Control for shivering | Subjects | Whole-body energy expenditure | Marker of BAT activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT 17 °C for 120 min before the scan, and for 180 min during blood flow measurement | Subjective | 6M, 21 [2] yr, 23 [2] kg/m2 | ↑ 1.1-fold | Glucose uptake ↑ 3.1-fold Blood flow ↑ 1.5-fold |

Weir et al. (2018) |

| RT 15.5 °C for 30 min before and also during the scan, plus airflow | Subjective | Low BAT: 7F/9M, 31 [10] yr, 25 [4] kg/m2 | NS | O2 consumption, NS Blood flow ↑ 1.2-fold |

Muzik et al. (2013) |

| High BAT: 8F/1M, 30 [6] yr, 22 [3] kg/m2 | ↑ 1.2-fold | O2 consumption ↑ 1.5-fold Blood flow ↑ 1.5-fold |

|||

| RT 17–19 °C for 120 min before the scan. During the scan, one foot in 5–9 °C water 5 min every | Not reported | 5 subjects 20–50 yr | Not measured | Glucose uptake ↑ 15-fold | Virtanen et al. (2009) |

| 5 min | Lean: 20F/7M, 40 [10] yr, 23 [2] kg/m2 | ↑ 1.2-fold | Glucose uptake ↑ 7.8-fold Blood flow ↑ 2.2-fold |

Orava et al. (2013) | |

| Obese: 25F/11M, 38 [9] yr, 34 [4] kg/m2 | ↑ 1.2-fold | Glucose uptake ↑ 3.1-fold Blood flow ↑ 1.1-fold |

|||

| RT 20 °C plus cooling vest at 14 °C for 120 min before the scan | Subjective | 6F/4M, 27 [5] yr, 24 [4] kg/m2 | ↑ 1.1-fold | Glucose uptake ↑ 4.2-fold | Cypess et al. (2012) |

| Suit at 18 °C for 90–120 min before and also during the scan | EMG | 6M, 23–42 yr, 24–31 kg/m2 | ↑ 1.8-fold | Metabolic rate ↑ 1.8-fold | Ouellet et al. (2012) |

| 12M, 24 [4] yr, 26 [3] kg/m2 | ↑ 1.8-fold | Metabolic rate ↑ 2.3-fold | Blondin et al. (2015b) | ||

| 8M, 30 (25–35) yr, 25 (22–27) kg/m2 | ↑ 1.7-fold | Metabolic rate ↑ 4.4-fold Blood flow ↑ 1.6-fold (P = 0.06) |

Blondin et al. (2017b) | ||

| Blankets at ≥6 °C for 120 min before and also during the scan | Subjective | 2F/5M, 36 [11] yr, 26 [3] kg/m2 | ↑ 1.2-fold | O2 consumption ↑ 1.7-fold NEFA uptake ↑ 1.6-fold (P = 0.09) |

U Din et al. (2016) |

| Blood flow ↑ 1.8-fold | |||||

| 4F/5M, 36 [9] yr, 26 [3] kg/m2 | ↑ 1.2-fold | O2 consumption ↑ 2.3-fold NEFA uptake ↑ 1.8-fold Blood flow ↑ 2.5-fold |

U Din et al. (2018) | ||

| Blankets at 4–18 °C for 120 min before the scan. During the scan, feet in contact with iced bags | ECG and subjective | 4F/6M, 25–45 yr, 21–29 kg/m2 | Not measured | Low BAT group: BAT temperature, NS | Koskensalo et al. (2017) |

| High BAT group: BAT temperature ↑ 1.1-fold (P = 0.06) |

Values are means [standard deviation] or means (95% confidence interval). ECG, electrocardiogram; EMG, electromyography; RT, room temperature; NEFA, nonesterifed fatty acids; NS, non-significant. M, males; F, females.

In turn, BAT oxygen consumption measured by 15O2 PET represents an actual thermogenic marker of BAT activity (Muzik et al., 2013; U Din et al., 2018, 2016). Estimation of BAT thermogenic potential and its contribution to whole-body energy expenditure should thus consider oxygen consumption rather than other surrogate markers (Jensen, 2015).

4. Influence of activated BAT on whole-body energy expenditure and body weight

One of the best known mitochondrial uncouplers used in humans is 2,4-dinitrophenol. This compound increased basal metabolic rate up to 50%, which was followed by a weight loss of ~900 g per week (Cutting et al., 1933). However, high doses caused deaths, leading to the banning of 2,4-dinitrophenol commercialization in many countries (Harper et al., 2008). The later identification of UCP1 provided the molecular basis for understanding energy dissipation by BAT (Nicholls et al., 1978). Because UCP1 is only expressed in BAT, and BAT was supposedly only present in newborns, manipulating UCP1 to increase energy expenditure in adults was discouraged. Three decades later, demonstration of the presence of active BAT in adult humans (Cypess et al., 2009; van Marken Lichtenbelt et al., 2009; Virtanen et al., 2009) revitalized the interest for manipulation of energy efficiency to control body weight.

High BAT activity is associated with high resting metabolic rate under thermoneutral conditions in some (Bakker et al., 2014; van Marken Lichtenbelt et al., 2009) but not all studies (Vijgen et al., 2011; Yoneshiro et al., 2011a). In turn, BAT activity is consistently related to resting metabolic rate upon cold stimulation (Chen et al., 2013; van Marken Lichtenbelt et al., 2009; Vijgen et al., 2011; Yoneshiro et al., 2011a). Other studies have reported that high BAT activity is associated with low body mass index (Cypess et al., 2009; Saito et al., 2009; van Marken Lichtenbelt et al., 2009; Vijgen et al., 2011; Yoneshiro et al., 2011b) and low fat mass (Saito et al., 2009; Vijgen et al., 2011; Yoneshiro et al., 2011b). This indirect evidence has stimulated the idea of treating obesity by increasing BAT mass/activity.

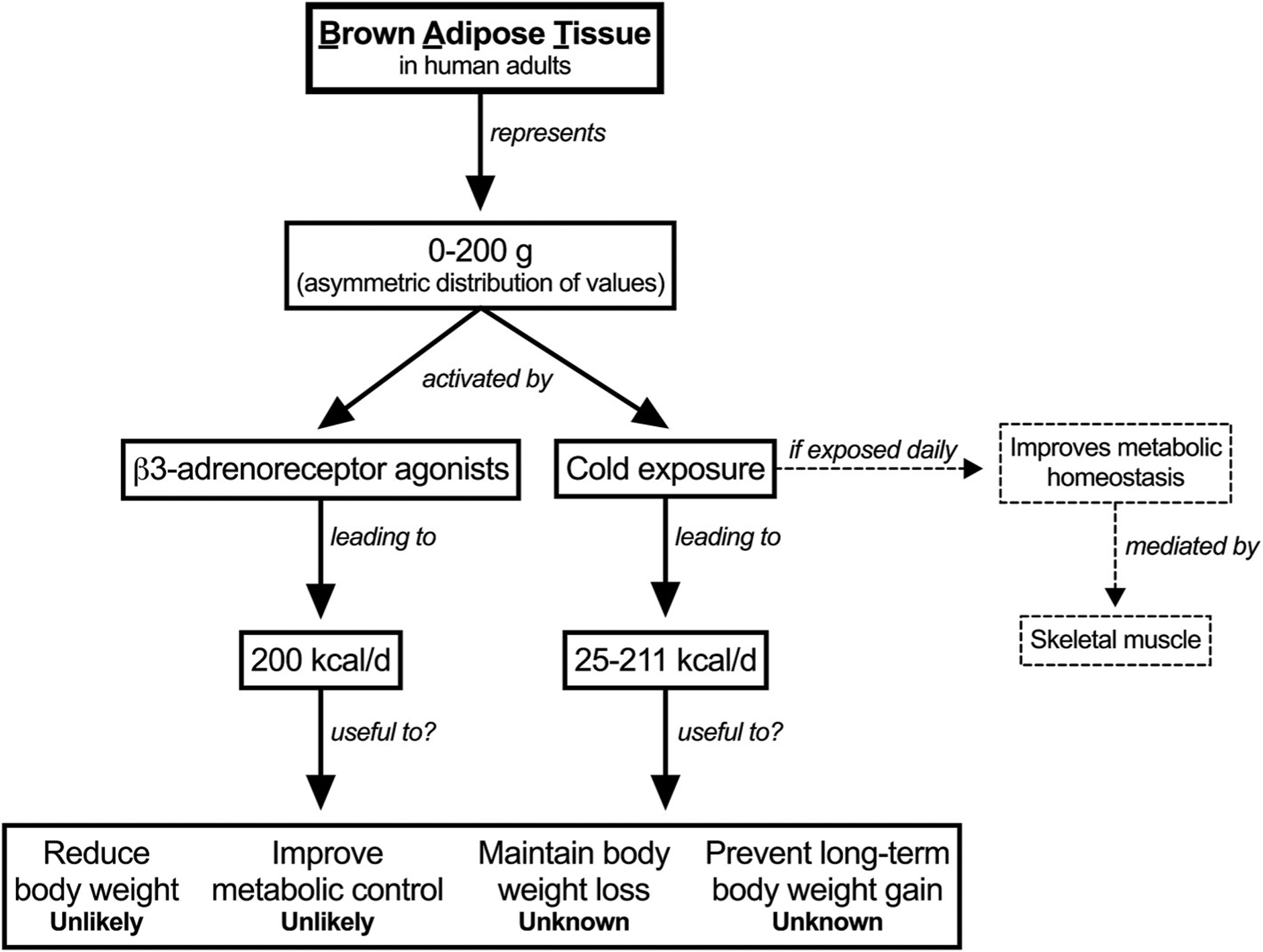

The contribution of BAT activation to whole-body energy expenditure has been under debate. Studies measuring BAT oxygen consumption following acute cold exposure have calculated that BAT-induced energy expenditure increases up to 25 kcal/d (Muzik et al., 2013; U Din et al., 2016). Recent calculations considering FDG uptake as a marker of BAT activity led to a value of 193 kcal/d (Marlatt et al., 2018). BAT-related energy expenditure has also been calculated using BAT mass from radiological 3D mapping (Leitner et al., 2017) combined with BAT oxygen consumption (U Din et al., 2016). From those techniques, BAT-related energy expenditure upon cold exposure was estimated to reach up to 211 kcal/d (Carpentier et al., 2018). An alternative approach led to 80 kcal/d (Tapia et al., 2018) after considering BAT as metabolically active as heart or kidneys (the organs with the highest specific resting metabolic rate in humans [Wang et al., 2010]) and a BAT mass of 200 g (the upper value in most individuals [Ouellet et al., 2012]). Importantly, all these theoretical calculations assume a maximally activated BAT across an entire day, which is unlikely to ever occur.

In conclusion, enhanced thermogenesis due to activated BAT seems small and unlikely to lead to clinically meaningful reductions in body weight, even in the absence of compensatory increases in energy intake. In support of this, no change in body weight has been found after exposure to 19 °C for 10 h/d during 4 weeks (Lee et al., 2014), or after exposure to 17 °C for 2 h/d during 6 weeks (Yoneshiro et al., 2013). Additionally, although BAT is more active upon low outdoor temperatures (Cypess et al., 2009; Gerngroβ et al., 2017; Ouellet et al., 2011; Saito et al., 2009), obesity prevalence is not associated with outdoor temperature once poverty, race, and education are considered (Speakman and Heidari-Bakavoli, 2016). Activation of BAT and its resulting increase in energy expenditure thus appears ineffective as a potential strategy for obesity treatment. Therefore, association of high body mass index with low BAT activity may simply result from individuals with greater fat mass having less need for thermogenic tissue (Nahon et al., 2017; Speakman, 2018). Despite this, the role of activating BAT to prevent long-term weight gain (Dutton et al., 2016; Hill, 2006) and help in weight maintenance after weight loss (Marlatt et al., 2018) still deserves further investigation.

5. Influence of activated BAT on metabolic control

Enhancing BAT activity may play a role in the metabolic control of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Theoretically, the high metabolic activity of BAT could be useful for increasing the clearance and utilization of circulating glucose and lipid, thus improving metabolic homeostasis. Indirect evidence supports this hypothesis. Low outdoor temperature is associated with high BAT activity (Ouellet et al., 2011; Saito et al., 2009), and is also associated with lower prevalence of glucose intolerance and lower prevalence and incidence of type 2 diabetes, independent of age and obesity (Blauw et al., 2017; Speakman and Heidari-Bakavoli, 2016). Finally, presence of BAT determined lower circulating glucose and HbA1c concentrations after controlling for age, sex and body fat mass (Matsushita et al., 2014).

As a result, several studies have analyzed the effect of cold exposure (to activate BAT) on glucose homeostasis. Acute cold exposure (5–8 h) was reported to increase basal and insulin-stimulated whole-body glucose disposal in individuals with high, but not low, BAT mass and activity (Chondronikola et al., 2014). Similarly, 10 days of daily cold exposure increased insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in individuals with type 2 diabetes (Hanssen et al., 2015). Although these studies did not detect changes in glycemia, the overall findings suggest cold-induced BAT activation improves glycemic control. These observed beneficial effects, however, seem mostly due to a metabolic effect in skeletal muscle rather than in BAT. Recent calculations show that BAT glucose uptake reaches at most only 5 g per day (Carpentier et al., 2018), representing < 2% of whole-body glucose turnover in humans. Indeed, 10 days of daily cold exposure increased cold-induced glucose uptake by skeletal muscle, thus partly explaining the effect of long-term cold exposure on glucose homeostasis (Hanssen et al., 2016).

Concerning lipid metabolism, acute cold exposure has been shown to increase BAT NEFA uptake and NEFA appearance into circulation (Ouellet et al., 2012; U Din et al., 2018, 2016). Because BAT NEFA uptake increased to a smaller extent than NEFA appearance, this resulted in elevated blood NEFA concentration (Ouellet et al., 2012). A separate study reported a reduction in total blood cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol concentrations among individuals with hypercholesterolemia following chronic cold exposure for 90 days (De Lorenzo et al., 1998). As previously discussed, however, the effects of cold exposure do not necessarily depend on BAT activity. In fact, BAT explains at most 0.5% of plasma NEFA turnover following acute cold exposure (Ouellet et al., 2012).

Catecholamines are physiological humoral factors that activate BAT through β3-adrenoreceptors. The acute and chronic effects of β3-adrenoreceptor agonists on glucose and lipid homeostasis have therefore been studied. Acute administration of mirabegron (Myrbetriq® a high-affinity β3-adrenoreceptor [Takasu et al., 2007] developed for treatment of overactive bladder) (Baskin et al., 2018; Cypess et al., 2015) or TAK-677 (another β3-adrenoreceptor agonist) (Redman et al., 2007) showed no effect on glycemia. Moreover, blood NEFA concentration was not modified by acute administration of mirabegron, but increased after TAK-677 (Redman et al., 2007). Chronic administration of TAK-677 (29 days [Redman et al., 2007]) or CL316,243 (8 weeks [Weyer et al., 1998]) showed no effect on glycemia, but CL316,243 did increase insulin-mediated glucose disposal. These compounds had divergent effects on blood NEFA concentration, with TAK-677 showing no effect (Redman et al., 2007), whereas increased concentration was noted after CL316,243 administration (Weyer et al., 1998). Thus, treatment with β3-adrenoreceptor agonists appears insufficient to reduce blood glucose and lipid concentrations, despite the evidence showing enhancement in insulin-mediated glucose disposal (Weyer et al., 1998).

6. Efforts to potentiate BAT thermogenesis

BAT activation induces a rather small increase in energy expenditure that appears insufficient to influence body weight or metabolic control. This may result from an insufficient amount of BAT mass or an ineffective BAT activation. Therefore, efforts are being made to identify acceptable and clinically relevant stimuli to increase BAT mass or to potentiate BAT activity. If effective, these stimuli could boost energy expenditure. Herein, we present the effectiveness of chronic cold exposure and of some pharmacological agents.

6.1. Chronic cold exposure

Known influence of different cooling protocols on BAT activation triggered interest for longer application of these protocols in humans (Table 2). Studies in healthy individuals reported increases in BAT mass, glucose uptake and metabolic rate after one month of daily cold exposure through either cooling suits (10 °C; 2 h/d) or exposure to a room at 19 °C (10 h/d) (Blondin et al., 2017a, 2014; Lee et al., 2014). Similar findings were observed after 10 days of exposure to 15–16 °C for 6 h/d (van der Lans et al., 2013). These data indicate that chronic cold exposure induces BAT acclimation that may potentiate BAT activation.

Table 2.

Protocols for chronic cold-induced activation of brown adipose tissue (BAT) in humans.

| Protocol | Subjects | Response in BAT | Whole-body energy expenditure (EE) | Body weight and metabolic control | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT 17 °C for 2h/d, 6wk | 12M, 24 [4] yr, 22 [3] kg/m2 | Cold-induced glucose uptake ↑ 1.6-fold | RMR, NS Cold-induced EE ↑ 1.2-fold |

Body weight, NS | Yoneshiro et al. (2013) |

| RT 19 °C for ≥10 h/d, 4wk | 5M, 21 [2] yr, 22 [1] kg/m2 | Volume ↑ 1.4-fold Cold-induced glucose uptake ↑ 1.5-fold |

24-h EE at 24 °C, NS 24-h EE at 19 °C, NS |

Body weight, NS Glucose, NEFA and TG, NS |

Lee et al. (2014) |

| RT 14–16 °C for 6 h/d, 10 d | 9F/8M, 23 [3] yr, 22 [2] kg/m2 | Volume ↑ 1.4-fold Cold-induced glucose uptake ↑ 1.2-fold |

RMR, NS Cold-induced EE ↑ 1.04-fold |

Glucose, NEFA and TG, NS | van der Lans et al. (2013) |

| 8 subjects with type-2 diabetes, 59 [6] yr, 30 [3] kg/m2 | Glucose uptake ↑ 1.6-fold | Cold-induced EE ↑ 1.1-fold | Body weight, NS Glucose, NEFA and TG, NS |

Hanssen et al. (2015) | |

| Insulin sensitivity ↑ 1.4-fold | |||||

| 10M, 36 [13] yr, 33 [4] kg/m2 | Glucose uptake ↑ 1.3-fold | RMR ↓ 16% (P = 0.06) Cold-induced EE, NS |

Glucose, NEFA and TG, NS | Hanssen et al. (2016) | |

| Suit at 10 °C for 2 h/d, 5 d/wk, 4 wk | 6M, 23 [2] yr, 25 [3] kg/m2 | Volume ↑ 1.4-fold | RMR, NS | Glucose ↓ 4% | Blondin et al. (2014) |

| Cold-induced glucose uptake ↑ 1.3-fold (P = 0.08) | NEFA and TG, NS | ||||

| Cold-induced metabolic rate ↑ 2.2-fold | |||||

| 9M, 23 [3] yr, 24 [3] kg/m2 | Volume ↑ 1.4-fold Cold-induced metabolic rate ↑ 2.8-fold |

RMR, NS Cold-induced EE, NS |

Body weight, NS Glucose, NEFA and TG, NS |

Blondin et al. (2017a) |

Values are means [standard deviation]. RMR, resting metabolic rate; RT, room temperature; NEFA, non-esterified fatty acids; TG, triglycerides; NS, non-significant. M, males; F, females.

However, daily cold exposure for 10–42 days did not change (Blondin et al., 2017a, 2014; van der Lans et al., 2013; Yoneshiro et al., 2013), or even decreased (Hanssen et al., 2016) resting energy expenditure measured under thermoneutral conditions. Besides, some (Hanssen et al., 2015; van der Lans et al., 2013; Yoneshiro et al., 2013), but not all (Blondin et al., 2017a; Hanssen et al., 2016) studies show an increase in cold-induced resting energy expenditure after chronic cold exposure. Chronic cold exposure neither affected 24-h energy expenditure measured in a whole-room calorimeter at 24 °C or 19 °C (Lee et al., 2014) (Table 2). Therefore, although BAT responds to chronic cold exposure, the response does not seem to translate into enhanced whole-body energy expenditure.

The fact that the activation of BAT by cold exposure is mediated by the sympathetic nervous system is indeed noteworthy (Carpentier et al., 2018; Lowell and Spiegelman, 2000). In fact, circulating norepinephrine increases in response to individualized cooling protocols using cooling suits (van der Lans et al., 2013). Furthermore, sympathetic nervous stimulation to BAT relates directly with BAT glucose uptake upon exposure to 16–17 °C for 2 h (Bahler et al., 2016). Additional evidence shows that individuals with catecholamine-secreting tumors have elevated BAT mass and whole-body energy expenditure, along with browning of white adipose tissue (Iyer et al., 2009; Lean et al., 1986; Søndergaard et al., 2015). These findings suggest stimulants of sympathetic activity as potential BAT activators, thus paving the way for the development of pharmacological agents.

6.2. Pharmacological agents

Activation of BAT by use of specific pharmacologic agonists has been explored (Arch, 2011; Cypess et al., 2012; Malik et al., 2012). Unfortunately, heart rate and systolic blood pressure have been reported to increase following the use of such pharmacologic agents, mostly due to non-selective β3-adrenoreceptors activation (Baskin et al., 2018; Cypess et al., 2015; Redman et al., 2007). Mirabegron (200 mg) has been reported to acutely increase BAT activity in individuals known to display BAT activation upon cold exposure (Cypess et al., 2015). Mirabegron also increased resting metabolic rate by ~200 kcal/d, a phenomenon directly related to BAT activation measured by FDG uptake (Cypess et al., 2015). A subsequent study confirmed the effect of 200 mg mirabegron on BAT activity (measured by FDG uptake) and resting metabolic rate (Baskin et al., 2018). Despite these findings, a 200-mg dose of mirabegron also produced clinically meaningful elevations in heart rate and systolic blood pressure (Baskin et al., 2018; Cypess et al., 2015). A smaller dose of mirabegron (50 mg; approved for treatment of overactive bladder), however, barely increased BAT activity, and did not increase resting metabolic rate (Baskin et al., 2018).

7. Concluding remarks

Detection of BAT in adult humans has provided a potential alternative to stimulate energy expenditure, which might eventually result in some health benefits (Fig. 2). Despite these observations, three major challenges remain. First, the amount of detectable BAT mass appears insufficient to support any major effect on whole-body energy balance. Although the amount of potentially active BAT appears several folds greater than the amount of active BAT, potentially active BAT seems strongly resilient to activation (Leitner et al., 2017). Second, BAT activation, even if activated the entire day, may increase energy expenditure to a level that is unlikely to reduce body weight. Still, further studies are required to determine the effect of longer periods of cold exposure on body weight. Finally, BAT activity likely evolved as a cold-induced mechanism to preserve core temperature, and not to burn off calorie excess. Putative BAT activators (e.g. drugs, food ingredients, etc.) thus face the challenge of being effective under conditions other than cold exposure.

Fig. 2.

Contribution of brown adipose tissue to human energy metabolism.

Funding

This work was supported by FONDECYT-Chile [#11180361 to RFV; #1170117 to JEG].

References

- Arch JRS, 2011. Challenges in β(3)-adrenoceptor agonist drug development. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab 2, 59–64. 10.1177/2042018811398517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba S, Jacene HA, Engles JM, Honda H, Wahl RL, 2010. CT Hounsfield units of brown adipose tissue increase with activation: preclinical and clinical studies. J. Nucl. Med 51, 246–250. 10.2967/jnumed.109.068775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahler L, Verberne HJ, Admiraal WM, Stok WJ, Soeters MR, Hoekstra JB, Holleman F, 2016. Differences in sympathetic nervous stimulation of Brown adipose tissue between the young and old, and the lean and obese. J. Nucl. Med 57, 372–377. 10.2967/jnumed.115.165829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker LEH, Boon MR, van der Linden RAD, Arias-Bouda LP, van Klinken JB, Smit F, Verberne HJ, Jukema JW, Tamsma JT, Havekes LM, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Jazet IM, Rensen PCN, 2014. Brown adipose tissue volume in healthy lean south Asian adults compared with white Caucasians: a prospective, case-controlled observational study. Lancet. Diabetes. Endocrinol 2, 210–217. 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin AS, Linderman JD, Brychta RJ, McGehee S, Anflick-Chames E, Cero C, Johnson JW, O’Mara AE, Fletcher LA, Leitner BP, Duckworth CJ, Huang S, Cai H, Garraffo HM, Millo CM, Dieckmann W, Tolstikov V, Chen EY, Gao F, Narain NR, Kiebish MA, Walter PJ, Herscovitch P, Chen KY, Cypess AM, 2018. Regulation of human adipose tissue activation, gallbladder size, and bile acid metabolism by a β3-adrenergic receptor agonist. Diabetes 67, 2113–2125. 10.2337/db18-0462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauw LL, Aziz NA, Tannemaat MR, Blauw CA, de Craen AJ, Pijl H, Rensen PCN, 2017. Diabetes incidence and glucose intolerance prevalence increase with higher outdoor temperature. BMJ Open. Diabetes. Res. Care 5, e000317 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondin DP, Daoud A, Taylor T, Tingelstad HC, Bézaire V, Richard D, Carpentier AC, Taylor AW, Harper M-E, Aguer C, Haman F, 2017a. Four-week cold acclimation in adult humans shifts uncoupling thermogenesis from skeletal muscles to brown adipose tissue. J. Physiol 595, 2099–2113. 10.1113/JP273395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondin DP, Frisch F, Phoenix S, Guérin B, Turcotte ÉE, Haman F, Richard D, Carpentier AC, 2017b. Inhibition of intracellular triglyceride lipolysis suppresses cold-induced Brown adipose tissue metabolism and increases shivering in humans. Cell Metabol. 25, 438–447. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondin DP, Labbé SM, Noll C, Kunach M, Phoenix S, Guérin B, Turcotte ÉE, Haman F, Richard D, Carpentier AC, 2015a. Selective impairment of glucose but not fatty acid or oxidative metabolism in Brown adipose tissue of subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 64, 2388–2397. 10.2337/db14-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondin DP, Labbé SM, Phoenix S, Guérin B, Turcotte ÉE, Richard D, Carpentier AC, Haman F, 2015b. Contributions of white and brown adipose tissues and skeletal muscles to acute cold-induced metabolic responses in healthy men. J. Physiol 593, 701–714. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.283598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondin DP, Labbé SM, Tingelstad HC, Noll C, Kunach M, Phoenix S, Guérin B, Turcotte EE, Carpentier AC, Richard D, Haman F, 2014. Increased brown adipose tissue oxidative capacity in cold-acclimated humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 99, E438–E446. 10.1210/jc.2013-3901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondin DP, Labbé SM, Turcotte EE, Haman F, Richard D, Carpentier AC, 2015c. A critical appraisal of brown adipose tissue metabolism in humans. Clin. Lipidol 10, 259–280. 10.2217/clp.15.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess E, Hassmén P, Welvaert M, Pumpa KL, 2017. Behavioural treatment strategies improve adherence to lifestyle intervention programmes in adults with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Obes 7, 105–114. 10.1111/cob.12180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier AC, Blondin DP, Virtanen KA, Richard D, Haman F, Turcotte ÉE, 2018. Brown adipose tissue energy metabolism in humans. Front. Endocrinol 9, 447 10.3389/fendo.2018.00447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KY, Brychta RJ, Linderman JD, Smith S, Courville A, Dieckmann W, Herscovitch P, Millo CM, Remaley A, Lee P, Celi FS, 2013. Brown fat activation mediates cold-induced thermogenesis in adult humans in response to a mild decrease in ambient temperature. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 98, E1218–E1223. 10.1210/jc.2012-4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KY, Cypess AM, Laughlin MR, Haft CR, Hu HH, Bredella MA, Enerbäck S, Kinahan PE, van M. Lichtenbelt W, Lin FI, Sunderland JJ, Virtanen KA, Wahl RL, 2016. Brown adipose reporting criteria in imaging STudies (BARCIST 1.0): recommendations for standardized FDG-PET/CT experiments in humans. Cell Metabol. 24, 210–222. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chondronikola M, Volpi E, Børsheim E, Porter C, Annamalai P, Enerbäck S, Lidell ME, Saraf MK, Labbe SM, Hurren NM, Yfanti C, Chao T, Andersen CR, Cesani F, Hawkins H, Sidossis LS, 2014. Brown adipose tissue improves whole-body glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes 63, 4089–4099. 10.2337/db14-0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman E, 2007. Dinitrophenol and obesity: an early twentieth-century regulatory dilemma. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 48, 115–117. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutting WC, Mehrtens HG, Tainter ML, 1933. Actions and uses of dinitrophenol. J. Am. Med. Assoc 101, 193 10.1001/jama.1933.02740280013006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cypess AM, Chen Y-C, Sze C, Wang K, English J, Chan O, Holman AR, Tal I, Palmer MR, Kolodny GM, Kahn CR, 2012. Cold but not sympathomimetics activates human brown adipose tissue in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 10001–10005. 10.1073/pnas.1207911109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, Kuo FC, Palmer EL, Tseng Y-H, Doria A, Kolodny GM, Kahn CR, 2009. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N. Engl. J. Med 360, 1509–1517. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypess AM, Weiner LS, Roberts-Toler C, Franquet Elía E, Kessler SH, Kahn PA, English J, Chatman K, Trauger SA, Doria A, Kolodny GM, 2015. Activation of human brown adipose tissue by a β3-adrenergic receptor agonist. Cell Metabol. 21, 33–38. 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lorenzo F, Mukherjee M, Kadziola Z, Sherwood R, Kakkar VV, 1998. Central cooling effects in patients with hypercholesterolaemia. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 95, 213–217. 10.1042/CS19980091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton GR, Kim Y, Jacobs DR, Li X, Loria CM, Reis JP, Carnethon M, Durant NH, Gordon-Larsen P, Shikany JM, Sidney S, Lewis CE, 2016. 25-year weight gain in a racially balanced sample of U.S. adults: the CARDIA study. Obesity 24 1962–8. 10.1002/oby.21573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerngroß C, Schretter J, Klingenspor M, Schwaiger M, Fromme T, 2017. Active Brown fat during 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging defines a patient group with characteristic traits and an increased probability of Brown fat redetection. J. Nucl. Med 58, 1104–1110. 10.2967/jnumed.116.183988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosby AK, Conigrave AD, Raubenheimer D, Simpson SJ, 2014. Protein leverage and energy intake. Obes. Rev 15, 183–191. 10.1111/obr.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen MJW, Hoeks J, Brans B, van der Lans AAJJ, Schaart G, van den Driessche JJ, Jörgensen JA, Boekschoten MV, Hesselink MKC, Havekes B, Kersten S, Mottaghy FM, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Schrauwen P, 2015. Short-term cold acclimation improves insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Med 21, 863–865. 10.1038/nm.3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen MJW, van der Lans AAJJ, Brans B, Hoeks J, Jardon KMC, Schaart G, Mottaghy FM, Schrauwen P, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, 2016. Short-term cold acclimation recruits Brown adipose tissue in obese humans. Diabetes 65, 1179–1189. 10.2337/db15-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper M-E, Green K, Brand MD, 2008. The efficiency of cellular energy transduction and its implications for obesity. Annu. Rev. Nutr 28, 13–33. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JO, 2006. Understanding and addressing the epidemic of obesity: an energy balance perspective. Endocr. Rev 27, 750–761. 10.1210/er.2006-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer RB, Guo CC, Perrier N, 2009. Adrenal pheochromocytoma with surrounding brown fat stimulation. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol 192, 300–301. 10.2214/AJR.08.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MD, 2015. Brown adipose tissue–not as hot as we thought. J. Physiol 593, 489 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.287979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskensalo K, Raiko J, Saari T, Saunavaara V, Eskola O, Nuutila P, Saunavaara J, Parkkola R, Virtanen KA, 2017. Human Brown adipose tissue temperature and fat fraction are related to its metabolic activity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 102, 1200–1207. 10.1210/jc.2016-3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lean ME, James WP, Jennings G, Trayhurn P, 1986. Brown adipose tissue in patients with phaeochromocytoma. Int. J. Obes 10, 219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P, Smith S, Linderman J, Courville AB, Brychta RJ, Dieckmann W, Werner CD, Chen KY, Celi FS, 2014. Temperature-acclimated brown adipose tissue modulates insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes 63, 3686–3698. 10.2337/db14-0513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner BP, Huang S, Brychta RJ, Duckworth CJ, Baskin AS, McGehee S, Tal I, Dieckmann W, Gupta G, Kolodny GM, Pacak K, Herscovitch P, Cypess AM, Chen KY, 2017. Mapping of human brown adipose tissue in lean and obese young men. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 114, 8649–8654. 10.1073/pnas.1705287114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell BB, Spiegelman BM, 2000. Towards a molecular understanding of adaptive thermogenesis. Nature 404, 652–660. 10.1038/35007527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig DS, Ebbeling CB, 2018. The carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity: beyond “calories in, calories out”. JAMA Intern Med 178, 1098–1103. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik M, van Gelderen EM, Lee JH, Kowalski DL, Yen M, Goldwater R, Mujais SK, Schaddelee MP, de Koning P, Kaibara A, Moy SS, Keirns JJ, 2012. Proarrhythmic safety of repeat doses of mirabegron in healthy subjects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-, and active-controlled thorough QT study. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 92, 696–706. 10.1038/clpt.2012.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt KL, Chen KY, Ravussin E, 2018. Is activation of human brown adipose tissue a viable target for weight management? Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 315, R479–R483. 10.1152/ajpregu.00443.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Tellez B, Nahon KJ, Sanchez-Delgado G, Abreu-Vieira G, Llamas-Elvira JM, van Velden FHP, Pereira Arias-Bouda LM, Rensen PCN, Boon MR, Ruiz JR, 2018. The impact of using BARCIST 1.0 criteria on quantification of BAT volume and activity in three independent cohorts of adults. Sci. Rep 8, 8567 10.1038/s41598-018-26878-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita M, Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Kameya T, Sugie H, Saito M, 2014. Impact of brown adipose tissue on body fatness and glucose metabolism in healthy humans. Int. J. Obes 38, 812–817. 10.1038/ijo.2013.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melanson EL, Keadle SK, Donnelly JE, Braun B, King NA, 2013. Resistance to exercise-induced weight loss: compensatory behavioral adaptations. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc 45, 1600–1609. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31828ba942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller TD, Clemmensen C, Finan B, DiMarchi RD, Tschöp MH, 2018. Anti-obesity therapy: from rainbow pills to polyagonists. Pharmacol. Rev 70, 712–746. 10.1124/pr.117.014803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzik O, Mangner TJ, Leonard WR, Kumar A, Janisse J, Granneman JG, 2013. 15O PET measurement of blood flow and oxygen consumption in cold-activated human brown fat. J. Nucl. Med 54, 523–531. 10.2967/jnumed.112.111336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahon KJ, Boon MR, Doornink F, Jazet IM, Rensen PCN, Abreu-Vieira G, 2017. Lower critical temperature and cold-induced thermogenesis of lean and overweight humans are inversely related to body mass and basal metabolic rate. J. Therm. Biol 69, 238–248. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls DG, Bernson VS, Heaton GM, 1978. The identification of the component in the inner membrane of brown adipose tissue mitochondria responsible for regulating energy dissipation. Exper. Suppl 32, 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orava J, Nuutila P, Noponen T, Parkkola R, Viljanen T, Enerbäck S, Rissanen A, Pietiläinen KH, Virtanen KA, 2013. Blunted metabolic responses to cold and insulin stimulation in brown adipose tissue of obese humans. Obesity 21, 2279–2287. 10.1002/oby.20456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet V, Labbé SM, Blondin DP, Phoenix S, Guérin B, Haman F, Turcotte EE, Richard D, Carpentier AC, 2012. Brown adipose tissue oxidative metabolism contributes to energy expenditure during acute cold exposure in humans. J. Clin. Investig 122, 545–552. 10.1172/JCI60433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet V, Routhier-Labadie A, Bellemare W, Lakhal-Chaieb L, Turcotte E, Carpentier AC, Richard D, 2011. Outdoor temperature, age, sex, body mass index, and diabetic status determine the prevalence, mass, and glucose-uptake activity of 18F-FDG-detected BAT in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 96, 192–199. 10.1210/jc.2010-0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiko J, Holstila M, Virtanen KA, Orava J, Saunavaara V, Niemi T, Laine J, Taittonen M, Borra RJH, Nuutila P, Parkkola R, 2015. Brown adipose tissue triglyceride content is associated with decreased insulin sensitivity, independently of age and obesity. Diabetes Obes. Metab 17, 516–519. 10.1111/dom.12433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman LM, de Jonge L, Fang X, Gamlin B, Recker D, Greenway FL, Smith SR, Ravussin E, 2007. Lack of an effect of a novel beta3-adrenoceptor agonist, TAK-677, on energy metabolism in obese individuals: a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 92, 527–531. 10.1210/jc.2006-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Matsushita M, Watanabe K, Yoneshiro T, Nio-Kobayashi J, Iwanaga T, Miyagawa M, Kameya T, Nakada K, Kawai Y, Tsujisaki M, 2009. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes 58, 1526–1531. 10.2337/db09-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Navaneethan SD, Singh RP, Pothier CE, Nissen SE, Kashyap SR STAMPEDE investigators, 2017. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes, N. Engl. J. Med 376, 641–651. 10.1056/NEJMoa1600869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekelle PG, Hardy ML, Morton SC, Maglione M, Mojica WA, Suttorp MJ, Rhodes SL, Jungvig L, Gagné J, 2003. Efficacy and safety of ephedra and ephedrine for weight loss and athletic performance: a meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assoc 289, 1537–1545. 10.1001/jama.289.12.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JE, 2006. Thermogenic mechanisms and their hormonal regulation. Physiol. Rev 86, 435–464. 10.1152/physrev.00009.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D, 2005. Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis. Obes. Rev 6, 133–142. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søndergaard E, Gormsen LC, Christensen MH, Pedersen SB, Christiansen P, Nielsen S, Poulsen PL, Jessen N, 2015. Chronic adrenergic stimulation induces brown adipose tissue differentiation in visceral adipose tissue. Diabet. Med 32, e4–8. 10.1111/dme.12595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speakman JR, 2018. Obesity and thermoregulation. Handb. Clin. Neurol 156, 431–443. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63912-7.00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speakman JR, Heidari-Bakavoli S, 2016. Type 2 diabetes, but not obesity, prevalence is positively associated with ambient temperature. Sci. Rep 6, 30409 10.1038/srep30409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, McPherson K, Finegood DT, Moodie ML, Gortmaker SL, 2011. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet (London, Engl) 378, 804–814. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasu T, Ukai M, Sato S, Matsui T, Nagase I, Maruyama T, Sasamata M, Miyata K, Uchida H, Yamaguchi O, 2007. Effect of (R)-2-(2-aminothiazol-4-yl)-4’-{2-[(2-hydroxy-2-phenylethyl)amino]ethyl} acetanilide (YM178), a novel selective beta3-adrenoceptor agonist, on bladder function. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 321, 642–647. 10.1124/jpet.106.115840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia P, Fernández-Galilea M, Robledo F, Mardones P, Galgani JE, Cortés VA, 2018. Biology and pathological implications of brown adipose tissue: promises and caveats for the control of obesity and its associated complications. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc 93, 1145–1164. 10.1111/brv.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U Din M, Raiko J, Saari T, Kudomi N, Tolvanen T, Oikonen V, Teuho J, Sipilä HT, Savisto N, Parkkola R, Nuutila P, Virtanen KA, 2016. Human brown adipose tissue [(15)O]O2 PET imaging in the presence and absence of cold stimulus. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 43, 1878–1886. 10.1007/s00259-016-3364-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U Din M, Saari T, Raiko J, Kudomi N, Maurer SF, Lahesmaa M, Fromme T, Amri E-Z, Klingenspor M, Solin O, Nuutila P, Virtanen KA, 2018. Postprandial oxidative metabolism of human Brown fat indicates thermogenesis. Cell Metabol. 28, 207–216. e3. 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Lans AAJJ, Hoeks J, Brans B, Vijgen GHEJ, Visser MGW, Vosselman MJ, Hansen J, Jörgensen JA, Wu J, Mottaghy FM, Schrauwen P, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, 2013. Cold acclimation recruits human brown fat and increases nonshivering thermogenesis. J. Clin. Investig 123, 3395–3403. 10.1172/JCI68993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Vanhommerig JW, Smulders NM, Drossaerts JMAFL, Kemerink GJ, Bouvy ND, Schrauwen P, Teule GJJ, 2009. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N. Engl. J. Med 360, 1500–1508. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandevijvere S, Chow CC, Hall KD, Umali E, Swinburn BA, 2015. Increased food energy supply as a major driver of the obesity epidemic: a global analysis. Bull. World Health Organ 93, 446–456. 10.2471/BLT.14.150565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijgen GHEJ, Bouvy ND, Teule GJJ, Brans B, Schrauwen P, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, 2011. Brown adipose tissue in morbidly obese subjects. PLoS One 6, e17247 10.1371/journal.pone.0017247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen KA, Lidell ME, Orava J, Heglind M, Westergren R, Niemi T, Taittonen M, Laine J, Savisto N, Enerbäck S, Nuutila P, 2009. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N. Engl. J. Med 360, 1518–1525. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Ying Z, Bosy-Westphal A, Zhang J, Schautz B, Later W, Heymsfield SB, Müller MJ, 2010. Specific metabolic rates of major organs and tissues across adulthood: evaluation by mechanistic model of resting energy expenditure. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 92, 1369–1377. 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir G, Ramage LE, Akyol M, Rhodes JK, Kyle CJ, Fletcher AM, Craven TH, Wakelin SJ, Drake AJ, Gregoriades M-L, Ashton C, Weir N, van Beek EJR, Karpe F, Walker BR, Stimson RH, 2018. Substantial metabolic activity of human Brown adipose tissue during warm conditions and cold-induced lipolysis of local triglycerides. Cell Metabol. 27, 1348–1355. e4. 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerterp KR, Speakman JR, 2008. Physical activity energy expenditure has not declined since the 1980s and matches energy expenditures of wild mammals. Int. J. Obes 32, 1256–1263. 10.1038/ijo.2008.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyer C, Tataranni PA, Snitker S, Danforth E, Ravussin E, 1998. Increase in insulin action and fat oxidation after treatment with CL 316,243, a highly selective beta3-adrenoceptor agonist in humans. Diabetes 47, 1555–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, Kameya T, Nakada K, Kawai Y, Saito M, 2011a. Brown adipose tissue, whole-body energy expenditure, and thermogenesis in healthy adult men. Obesity 19, 13–16. 10.1038/oby.2010.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, Kayahara T, Kameya T, Kawai Y, Iwanaga T, Saito M, 2013. Recruited brown adipose tissue as an antiobesity agent in humans. J. Clin. Investig 123, 3404–3408. 10.1172/JCI67803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Kameya T, Kawai Y, Miyagawa M, Tsujisaki M, Saito M, 2011b. Age-related decrease in cold-activated brown adipose tissue and accumulation of body fat in healthy humans. Obesity 19, 1755–1760. 10.1038/oby.2011.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]