Abstract

Salinity is one of the most severe abiotic stress factors that limit crop productivity by affecting the growth of plants. Therefore, it is significant to know the responses of plants against salt stress. In this study, the callus formation capabilities of nodal explants of Limnophila aromatica (Lamk.) Merr. and Bacopa monnieri (L.) Wettst. incubated under different NaCl concentrations (0–100 mM) in in vitro culture conditions were investigated and also the effect of NaCl on the release of regenerated shoots from these calluses was examined. Furthermore, the plants under NaCI stress were evaluated physiologically and biochemically. Callus formation percentages and callus intensities from the nodal explants decreased with increasing NaCl concentrations. In addition, yellowing, browning and even deaths were observed in calluses under salt toxicity. The callus was taken into the subculture, and the increased NaCl concentration in both plant species adversely affected the regeneration ability of the shoots. The number of shoots per callus for L. aromatica and B. monnieri was 6.72–17.49 and 7.42–15.38, respectively. The length of shoots in L. aromatica was between 0.95 and 1.65 cm, and in B. monnieri between 1.17 and 1.81 cm. The lowest number of shoots per callus and the shoot lengths were found in medium containing 100 mM NaCl. Moreover, photosynthetic pigmentation, lipid peroxidation, protein content, and proline content was damaged with increased salinity compared to the control group. This comprehensive study in tissue culture conditions can a be potential contributor to the literature and can help other studies to be carried out in the future.

Keywords: Lipid peroxidation, Photosynthetic pigment, NaCI stress, Shoot regeneration, Toxicity

Introduction

Each factor that inhibits plant growth is defined as stress. In many parts of the world, drought, salinity, excessive watering, high and low temperature, pH and heavy metal stresses are common. These stresses cause social and economic problems, especially for developing countries. Only 10% of the agricultural land in the world is not faced with any environmental stressors. It is thought that 20% of the total agriculture and 33% of the irrigated agricultural fields are affected by high salinity. It is also estimated that by 2050, 50 per cent of arable agricultural areas will be salted (Shao et al. 2008; Shrivastava and Kumar 2015).

Apart from natural salinisation, a significant portion of the cultivated agricultural lands in recent years has been salted due to wrong irrigation methods. Forty-five million hectares of 230 million hectares of wetlands are affected by salt (Riffat and Ahmad 2016). Even though significant expenditures are being made to solve such problems worldwide, manufacturers still face these problems. Understanding the adaptation mechanisms of plants under salt stress is of great importance to benefit more from saline areas (Ashraf and Harris 2004; Munns 2005).

Salt stress is one of the major abiotic stress factors that affect crop growth and limit crop productivity. The high salinity rate prevents plant growth by changing the plant cell membrane, lipid and protein composition and causes ionic and osmotic stresses (Cominelli et al. 2013). These negative effects of salt stress vary depending on salt type, salt concentration, duration of stress, genotype of the plant. Affected by various metabolic events in plants exposed to salinity can reduce the chances of survival of plants. Some plants are sensitive to these conditions, while others are able to survive through various tolerance mechanisms. These mechanisms of tolerance to salt stress are the accumulation or excretion of ions, the control of ion uptake and exile transmission in the root, the accumulation of ions in certain parts of the plant, synthesis of osmotic regulators, activation of certain antioxidant systems and activation or inactivation of various genes (Abogadallah 2010; Nawaz et al. 2010; Cominelli et al. 2013).

Plant species show different physiological and metabolic responses to stress (Ghanbari et al. 2019; Agır et al. 2017). The degree to which the plant species are affected by salt is related to the metabolic changes developed under physiological and biochemical responses. By examining these different reactions in plants, it is possible to develop certain criteria for selecting salt-tolerant species (Le Gall et al. 2015; Kahlaoui et al. 2018). Besides, many of the researches conducted to find solutions to the nutritional problem that emerged with the rapid increase in the world population aim to identify the plant species that can be produced in adverse environmental conditions. Scientists have attached great importance to the investigation of the relationship between drought and salinity stress and the plant from different angles (Reddy et al. 2018; Wu et al. 2018; Kalaji et al. 2018).

Tissue culture is one of the best techniques to study the response of plants to stress conditions. It is a technique that allows us to obtain thousands of plants or herbal products in a short time from plant, cell and tissue parts (explant) taken into an artificial nutrient medium (Oseni et al. 2018; Dogan et al. 2018). With this technique, many valuable plants such as Ceratophyllum demersum L. (Dogan et al. 2015; Emsen and Dogan 2018), Morinda coreia Buch.-Ham (Shekhawat et al. 2015) and Rotala rotundifolia (Buch-Ham. ex Roxb) Koehne (Dogan 2017) were propagated multiple and fast, and in vitro salt stress studies were also carried out in many plants such as Capsicum annuum L. (Bulle et al. 2016), potato (Hassanein and Salem 2017), Moringa oleifera (Salem et al. 2017).

Limnophila aromatica (Lamk.) Merr. and Bacopa monnieri (L.) Wettst. are valuable aquatic medicinal plants and are widely used by humans for various purposes such as therapeutic, food and ornamental (Gorai et al. 2014; Devendra et al. 2018; Smith et al. 2018). L. aromatica has been shown to have negligible toxicity and possesses diuretic, muscle relaxant, and antispasmodic activities. It is used to treat kidney stones, painful cramps, wounds, care and ulcers (Do et al. 2014). It is antiseptic, galactagogue, aperient, appetizer, digestive, carminative, anthelmintic, anti-inflammatory, diuretic and febrifuge. The juice of the L. aromatica is used as a cooling agent in fever and pharyngitis (Brahmachari 2014). A colorless antibacterial essential oil containing limonene and perillaldehyde as the main components was detected in L. aromatica (Rao et al. 1989). Chlorogenic, caffeic acids, and uncommon 8-oxygenated flavonoids were also observed in this species (Bui et al. 2004). It was also emphasized that Limnophila has important antimicrobial activity (Dubey 2002).

Numerous in vitro studies have been conducted proving the potential medical properties of the B. monnieri. Many randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated the nootropic benefit of BM in humans (Aguiar and Borowski 2013). B. monnieri has been reported to significantly improve verbal and visual memory in children and adolescents (Kean et al. 2016). B. monnieri is also used in the treatment of diseases such as epilepsy, insomnia, asthma, rheumatism and diuretic due to their valuable active compounds such as brahmine, herpestine, alkaloids, and saponins (bacoside A, bacoside B, and betulic acid) (Uabundit et al. 2010; Jain et al. 2016). Ethanol extract of BM has been reported to have antigastric ulcer activity in normal and diabetic rats as well as in vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori activity (Jain et al. 2016).

Since the demand for these plants is increasing, production is carried out in large areas. However, these plants are exposed to salt stress in their habitat and the production areas. The salinity limits the plant growth-development and yield considerably (Ahire et al. 2014). Therefore, it is very important to know the reactions of these plants against salt stress and to develop salt-tolerant plant lines. Tissue culture-based stress studies seem to be the best methodological approach compared to breeding studies used to assess salt tolerance (Jain 2001). In this study, the callus formation capabilities of L. aromatica and B. monnieri incubated under different NaCl concentrations in in vitro culture conditions were investigated and also the effect of NaCl on the release of regenerated shoots from these calluses was examined. Moreover, changes in physiological and biochemical parameters of the regenerated shoots (colour changes, photosynthetic pigmentation, lipid peroxidation, protein content, proline content) were evaluated as a result of salt toxicity.

Many physiological and biochemical characters play a role in the reactions of plants against salt stress (Ahmad et al. 2019). Examining the responses of L. aromatica and B. monnieri against increased salt stress at callus and tissue levels will help to understand these characters correctly. The callus formation responses of explants under salt stress were another innovative aspect of this study. Callus cultures can be an essential tool in increasing plant tolerance and yield through genetic transformation. Therefore, it is crucial to develop an effective callus proliferation protocol for genetic manipulation of plants with tissue culture, including in vitro selection studies and the development of salt-tolerant plants (Pérez-Clemente and Gómez-Cadenas 2012). This study, which includes tissue culture-based salt stress, provides the necessary knowledge and system for advanced studies on the physiological and biochemical basis of salt tolerance. Thus, the effects of the action mechanisms of salt on plant metabolism can be determined, and more effective protocols can be developed on the development of salt stress-resistant plants.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and surface sterilization

L. aromatica and B. monnieri were taken from the aquarium market in Konya (Turkey). Before the surface sterilization process was applied, the plants were kept under running tap water for 15 min. The nodal explants (1st and 2nd node explants containing the meristematic region) of L. aromatica and B. monnieri were treated with 20% and 30% NaOCl respectively for 10 min. After 15 min rinsing, the nodal explants were isolated and were then transferred to the Murashige and Skoog (1962) (MS) hormone-free basic nutrient medium.

In vitro salt treatment and callus inductions

To establish callus from nodal explants, 0.25 mg/L Thidiazuron (TDZ) and 0.25 mg/L 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) were added to the MS medium. Besides, 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 mM NaCl was added to determine the effect of salt stress on callus formation. In experiments, MS basal medium with vitamins containing 3% sucrose (Duchefa) and 6.5 g/L plant agar (Duchefa) was used. The pH of the MS medium was adjusted to 5.7 ± 0.1 with 1 N NaOH and 1 N HCl and then sterilised under 1.2 barometric compression for 20 min at 120 °C. The cultures were kept at a temperature of 24 ± 1 °C and 16 h of light photoperiod under white light flouresan (1500 lx). At the end of 5 weeks, the trial was completed and callus data were obtained. Callus density were measured by comparison with NaCl-free cultures (Control group). Calluses were weighed and categorized into four groups (++++ very high density; +++ density; ++ low density; + very low density).

In vitro sub-culture establishment and shoot regeneration

In order to evaluate the effect of salt on in vitro shoot regeneration, the calli were cultured in MS medium supplemented with 0.50 mg/L Kinetin (KIN) and 0, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 mM NaCl. 3% sucrose (Duchefa) and 6.5 g/L plant agar (Duchefa) were used in the preparation of the MS nutrient medium. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 5.7 ± 0.1 and sterilised in an autoclave (under 1.2 atmospheric pressure at 120 °C for 20 min). The culture conditions were set at 24 ± 1 °C and 16 h of illumination. At the end of 5 weeks, the trial was completed, and regeneration data were obtained.

Chlorophyll and carotenoid contents

Plant samples (100 mg) were extracted by trituration with 5 mL of 80% acetone. The maximum absorption values of 663 nm, 646 nm and 460 nm were measured at the spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Multiskan Go). Photosynthetic pigmentation (chlorophyll a, b and carotenoids) was estimated based on the method determined by Lichtenthaler and Wellburn (1983).

Lipid peroxidation and protein contents

Lipid peroxidation was determined by estimating the total amount of malondialdehyde (MDA) contents, according to Heath and Packer (1968). Total protein content was measured by bovine serum albumin as the standard protein, as described by Lowry et al. (1951).

Soluble proline quantification

The method described by Bates et al. (1973) was followed to determine the content of the proline. The absorbance of the toluene fraction aspirated from the liquid phase at 520 nm was read in the spectrophotometer. Proline concentration was calculated using the calibration curve and expressed as mg/g f.w.

Statistical analysis

All assays were established in triplicate and data was recorded. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 21 for Windows (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) program via one-way ANOVA. Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) were applied as Post Hoc tests and significant differences for shoot regeneration and biochemical data of the plants under salinity stress were analysed. Differences at p < 0.05 were considered significant. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were performed after different NaCI applications. Shoot regeneration frequency data in percentages were applied to arcsine (√X) transformation before analysis and then converted back to percentages for presentation in the Table 2. This transformation is effective in stabilizing the variances (Snedecor and Cochran 1997).

Table 2.

The in vitro shoot proliferation in L. aromatica and B. monnieri under different NaCl concentrations medium

| NaCI (mM) | Shoot regeneration frequency (%) | Mean number of shoots per callus | Shoot length (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. aromatica | |||

| 0 | 100a | 17.49a | 1.65ab |

| 20 | 100a | 15.07b | 1.61ab |

| 40 | 100a | 14.16bc | 1.54b |

| 60 | 100a | 10.24ef | 1.28 cd |

| 80 | 50c | 9.00efg | 1.03ef |

| 100 | 44.44c | 6.72 h | 0.95f |

| B. monnieri | |||

| 0 | 100.00a | 14.83b | 1.81a |

| 20 | 100.00a | 15.38b | 1.58ab |

| 40 | 100.00a | 12.49 cd | 1.49bc |

| 60 | 77.77b | 11.03de | 1.41bcd |

| 80 | 61.11bc | 8.15fgh | 1.22de |

| 100 | 44.44c | 7.42gh | 1.17def |

Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (p < 0.05; DMRT)

Results

Callus induction

The nodal explants of L. aromatica and B. monnieri were incubated in MS nutrient medium including various concentrations of NaCl and callus formation processes were evaluated (Table 1). Experiments have also been established in the salt-free environment (control). The first callus was determined on day 10 in the control group explants for L. aromatica, followed by 20 mM NaCl on day 12. On the other hand, the first callus formations in B. monnieri were observed on the 8th day in the nutrient medium containing 20 mM NaCl and the control group. The latest callus formations were recorded at L. aromatica on day 18, at B. monnieri at day 17.

Table 1.

Callus inductions in L. aromatica and B. monnieri under different NaCl concentrations

| NaCI (mM) | % of callus induction | First callus formation (day) | Callus density | Callus color |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. aromatica | ||||

| 0 | 100a | 10 | ++++ | Green, light green |

| 20 | 100a | 12 | ++++ | Green, light green, yellowish |

| 40 | 100a | 13 | ++ | Green, light green, yellowish |

| 60 | 88.87b | 13 | ++ | brownish, black, green |

| 80 | 72.21c | 17 | + | Dark brown, dark green, black |

| 100 | 38.87e | 18 | + | Dark brown, black |

| B. monnieri | ||||

| 0 | 100a | 8 | ++++ | Dark green |

| 20 | 100a | 8 | ++++ | Dark green |

| 40 | 100a | 11 | +++ | Dark green, brownish |

| 60 | 100a | 14 | ++ | Dark green, brownish |

| 80 | 55.55d | 15 | ++ | Light green, brownish |

| 100 | 33.33e | 17 | + | Brownish, black, light green, yellowish |

Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (p < 0.05; DMRT)

++++ very high density; +++ density; ++ low density; + very low density

The callus forming percentages of the explants under the increased salt concentration also changed significantly. The callus formation percentages for L. aromatica were between 38.87 and 100% and for B. monnieri, 33.33–100%. 100% callus formations were observed up to 40 mM NaCl in L. aromatica, while up to 60 mM NaCl in B. monnieri. The treatment with higher NaCl concentrations resulted in a decrease in the percentage of callus formation. The lowest callus percentage was determined in explants of 100 mM NaCl for both plants.

The callus formation intensities of the explants changed in the NaCl effect. The highest callus forming densities were observed in explants exposed to low levels of salt and the control group medium. Even the use of low levels of salt adversely affected the callus density. The low-density callus was determined in the presence of 100 mM salt. In some explants, toxicity induced by high NaCl levels prevented callus formation.

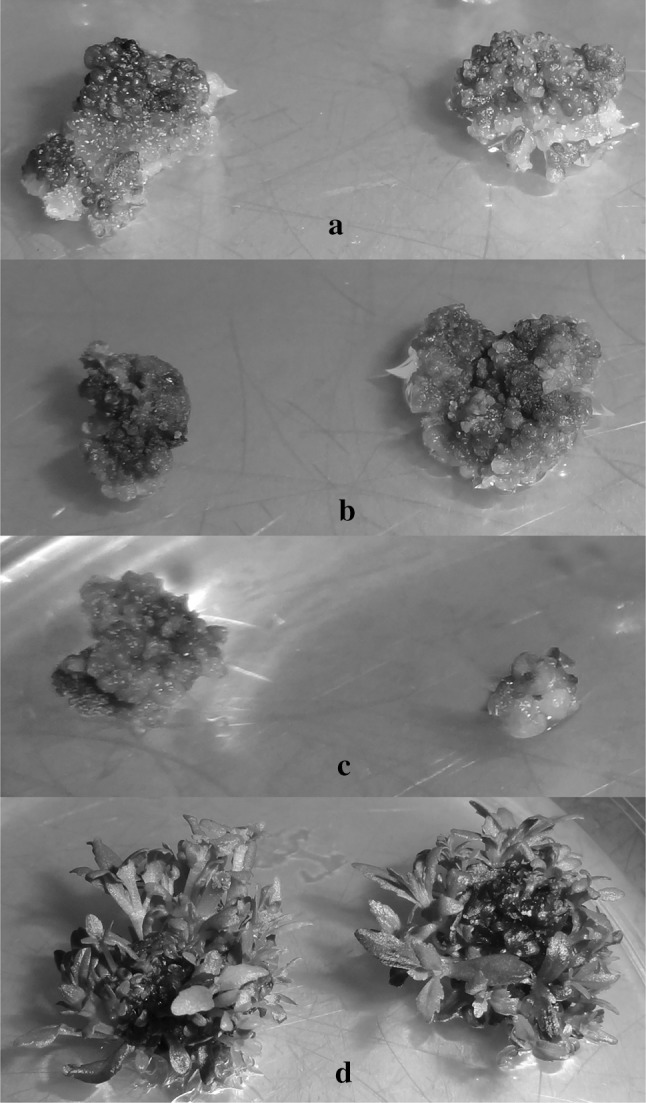

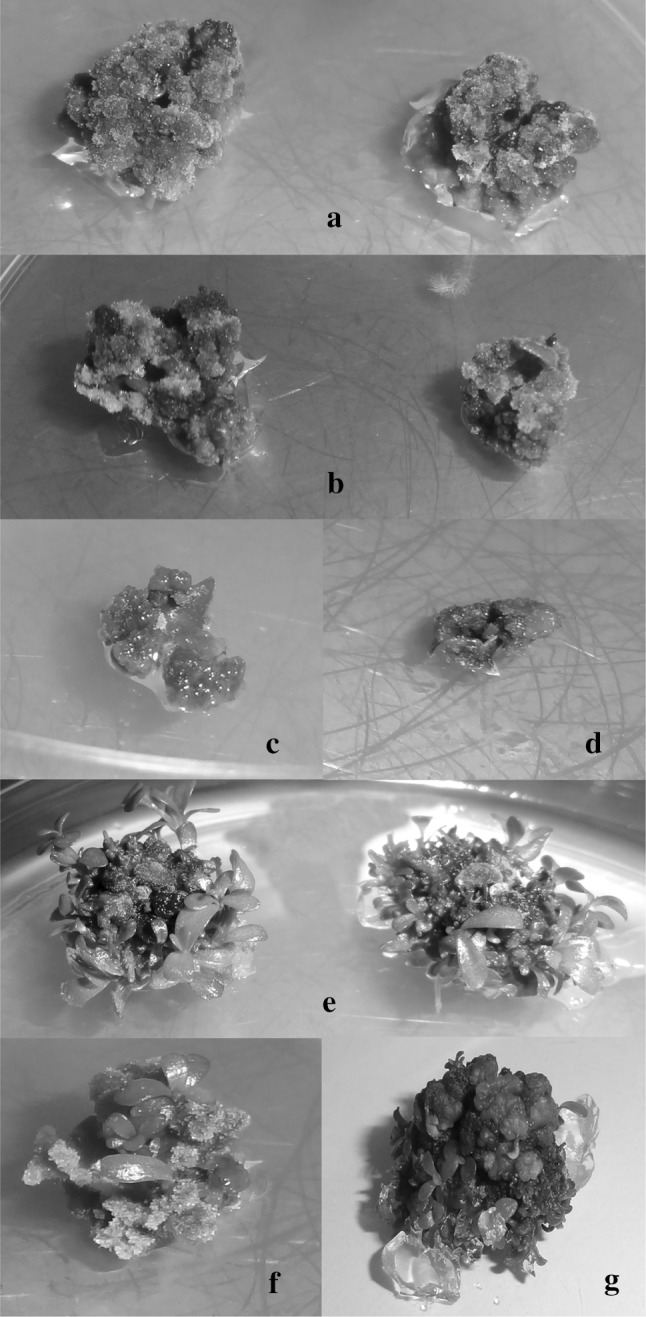

NaCl used in the nutrient environment also influenced their colors, such as the formation time and density of callus (Fig. 1, 2). In L. aromatica, the calluses in the salt-free medium and the low levels of NaCl were green, light green and yellowish, while with increasing NaCl concentration the callus became dark brown, dark green and blackish (Fig. 1b, c). The callus in B. monnieri was observed to be dark green in the control group (Fig. 2a) and in the low salt application. As a result of the increase in salt concentration, calluses such as brownish, black, light green and yellowish were observed (Fig. 2b). In addition, the death of some callus was observed in the environment with the effect of salinity (Fig. 2c, d).

Fig. 1.

Effect of NaCI stress on callus induction and shoot proliferation in L. aromatica cultured in vitro. a the calluses in the salt-free medium, and b, c yellowing, browned and small calluses with increased NaCl toxicity d the shoot proliferation from calluses with the effect of KIN (color figure online)

Fig. 2.

Effect of NaCI stress on callus induction and shoot proliferation in B. monnieri cultured in vitro. a the calluses in the salt-free medium, and b yellowing and brownish calluses and c, d callus deaths with increased NaCl toxicity f, g the shoot proliferation from calluses with the effect of KIN (color figure online)

In vitro shoot regeneration under different salt concentrations

The calli obtained in MS nutrient medium containing 0.25 mg/L TDZ + 0.25 mg/L 2,4-D for 5 weeks was then cultured in MS medium supplemented with 0.50 mg/L KIN and 0–100 mM NaCl for shoot regeneration. In this experiment, the effects of salinity on shoot regeneration percentage, number of shoots and elongation of the shoot were evaluated (Table 2). The increased NaCl concentration in both plant species adversely affected the regeneration ability of the shoots and thus decreased regeneration frequencies. Shoot regeneration frequencies were recorded between 44.44 and 100% in both plants. The regeneration frequencies of 100% were obtained at 0–60 mM salinity ratio in L. aromatica and 0–40 mM salinity in B. monnieri. The lowest shoot proliferation percentage was determined in culture medium containing 100 mM NaCl in both plants. A statistically significant positive correlation was determined between shoot regeneration frequency and the number of shoots per callus in L. aromatica (r = 0.783, p < 0.01) and B. monnieri (r = 0.818, p < 0.01) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients of L. aromatica and B. monnieri under different NaCI concentrations

| Shoot regeneration frequency | The number of shoots per callus | Shoot length | Chlorophyll a | Chlorophyll b | Total chlorophyll | Carotenoid | MDA | Protein | Proline | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters for L. aromatica | ||||||||||

| Shoot regeneration frequency | 1 | 0.783** | 0.837** | 0.785** | 0.749** | 0.782** | 0.821** | − 0.737** | 0.824** | − 0.836** |

| The number of shoots per callus | 1 | 0.845** | 0.934** | 0.892** | 0.935** | 0.917** | − 0.795** | 0.930** | − 0.895** | |

| Shoot length | 1 | 0.895** | 0.872** | 0.896** | 0.863** | − 0.913** | 0.889** | − 0.845** | ||

| Chlorophyll a | 1 | 0.947** | 0.997** | 0.932** | − 0.804** | 0.877** | − 0.880** | |||

| Chlorophyll b | 1 | 0.969** | 0.937** | − 0.800** | 0.845** | − 0.859** | ||||

| Total Chlorophyll | 1 | 0.942** | − 0.810** | 0.880** | − 0.883** | |||||

| Carotenoid | 1 | − 0.826** | 0.908** | − 0.897** | ||||||

| MDA | 1 | − 0.843** | 0.838** | |||||||

| Protein | 1 | − 0.820** | ||||||||

| Proline | 1 | |||||||||

| Parameters for B. monnieri | ||||||||||

| Shoot regeneration frequency | 1 | 0.818** | 0.697** | 0.863** | 0.775** | 0.857** | 0.779** | − 0.894** | 0.678** | − 0.840** |

| The number of shoots per callus | 1 | 0.811** | 0.870** | 0.801** | 0.868** | 0.791** | − 0.898** | 0.763** | − 0.902** | |

| Shoot length | 1 | 0.829** | 0.896** | 0.862** | 0.783** | − 0.771** | 0.811** | − 0.877** | ||

| Chlorophyll a | 1 | 0.896** | 0.993** | 0.902** | − 0.931** | 0.856** | − 0.932** | |||

| Chlorophyll b | 1 | 0.940** | 0.861** | − 0.884** | 0.839** | − 0.940** | ||||

| Total Chlorophyll | 1 | 0.910** | − 0.937** | 0.869** | − 0.952** | |||||

| Carotenoid | 1 | − 0.804** | 0.860** | − 0.910** | ||||||

| MDA | 1 | − 0.779** | 0.927** | |||||||

| Protein | 1 | − 0.901** | ||||||||

| Proline | 1 | |||||||||

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (1-tailed)

The calli in the culture environment differentiated with the effect of KIN and formed regenerated shoots (Fig. 1d, 2e). The number of these regenerated shoots changed with salinity effect and it was found statistically significant (p < 0.05). The formation of regenerated shoots from the control group callus was earlier than the browned callus with the effect of salt (Fig. 2f, g). The number of shoots per callus for L. aromatica and B. monnieri was 6.72–17.49, 7.42–15.38, respectively (Table 2). The highest number of shoots per callus in salt-containing media was obtained in the control group for L. aromatica followed by 20 mM NaCl (17.49). However, the maximum shoots per callus in B. monnieri were obtained from the callus in the medium treated with 20 mM NaCl (15.38) and then recorded from the callus in the control medium. The number of shoots decreased due to the increase in salt used. The lowest number of shoots per callus was recorded in medium containing 100 mM NaCl.

The length of the regenerated shoots from the callus under different salt concentrations decreased significantly (p < 0.05) (Table 2). The length of shoots in L. aromatica was between 0.95 and 1.65 cm, and in B. monnieri between 1.17 and 1.81 cm. The most extended shoot was obtained from the callus in the control medium for both plants. In terms of shoot lengths in L. aromatica, the control group and the medium containing 20 and 40 mM NaCI were not statistically significant. In B. monnieri, the length of shoots in the control medium and the length of shoots in the medium containing 20 mM NaCl were not statistically significant. The shoots remained stunted with a high salt concentration and the lowest shoot length was determined in the medium treated with 100 mM salt. Important relationships were obtained between shoot lengths and the number of shoots per callus in L. aromatica (r = 0.845, p < 0.01) and B. monnieri (r = 0.811, p < 0.01) (Table 3).

Chlorophyll and carotenoid contents

While the shoots first emerged from the callus were green and alive, yellowing was observed in these shoots as time passed. In addition, the color loss in shoots increased as a result of increased salt concentration. The loss of color (chlorosis) and yellowing were faster in L. aromatica. The photosynthetic pigment contents of the shoots were analysed to determine and measure this condition (Fig. 3). Increased concentrations of NaCl in both plant species reduced chlorophyll-a content and the lowest chlorophyll-a content was determined in the medium containing 100 mM NaCl. In L. aromatica, chlorophyll-a content was lower than B. monnieri. The lowest chlorophyll-a content in L. aromatica was calculated as 51.02% lower than control (Fig. 3a). The lowest chlorophyll content in B. monnieri was found to be 36.73% lower than control (Fig. 3b). In terms of chlorophyll-a content, 20 mM NaCl application and the control group of L. aromatica were not statistically significant. According to Pearson’s correlation coefficients in Table 3, significant positive relationships were found between chlorophyll-a and the number of shoots per callus in L. aromatica (r = 0.934, p < 0.01) and B. monnieri (r = 0.870, p < 0.01). In addition, there was a negative correlation between chlorophyll-a and MDA (r = − 0.804, p < 0.01 for L. aromatica; r = − 0.931, p < 0.01 for B. monnieri) and proline contents (r = − 0.880, p < 0.01 for L. aromatica; r = − 0.932, p < 0.01 for B. monnieri). However, a positive correlation was found between protein values (r = 0.877, p < 0.01 for L. aromatica; r = 0.856, p < 0.01 for B. monnieri).

Fig. 3.

The photosynthetic pigment contents in regenerated shoots with different concentrations of NaCl. Chlorophyll a (a, b) chlorophyll b (c, d) total chlorophyll (e, f) and carotenoid (g, h) contents in L. aromatica (a, c, e, g) and B. monnieri (b, d, f, h) after NaCl application. All values are the means of triplicates ± SD (n = 3). Vertical bars indicate standard error of three separate experiments. Different superscript letters indicate significantly different values (p < 0.05; DMRT)

Chlorophyll-b content of shoots diminished with increasing salinity level. The maximum chlorophyll-b levels were recorded in the control group shoots. On the other hand, the lowest chlorophyll-b contents in MS medium with 100 mM NaCl were 49.09% lower than the control for L. aromatica (Fig. 3c) and 44.24% lower than the control for B. monnieri (Fig. 3d). Total chlorophyll content in L. aromatica ranged between 0.71 and 1.43 mg/g f.w (Fig. 3e) and B. monnieri at 0.94–1.53 mg/g f.w (Fig. 3f). Similarly, total chlorophyll content decreased significantly with increasing NaCl concentration (p < 0.05). The minimum total chlorophyll content was obtained in shoots under 100 mM NaCl stress. The positive relationship was recorded between chlorophyll-b and chlorophyll-a (r = 0.947, p < 0.01 for L. aromatica; r = 0.896, p < 0.01 for B. monnieri) and the number of shoots (r = 0.892, p < 0.01 for L. aromatica; r = 0.801, p < 0.01 for B. monnieri) (Table 3).

Salinity adversely affected the carotenoid levels of the shoots. Increased salinity showed a reducing effect on carotenoid contents. The highest carotenoid content was obtained in the control medium, while the lowest carotenoid content was recorded at the highest NaCl concentration. In L. aromatica, the minimum carotenoid content was found to be 45.18% lower than the control under high salt toxicity (Fig. 3g). In B. monnieri, the minimum carotenoid content was 43.25% lower than the control (Fig. 3h).

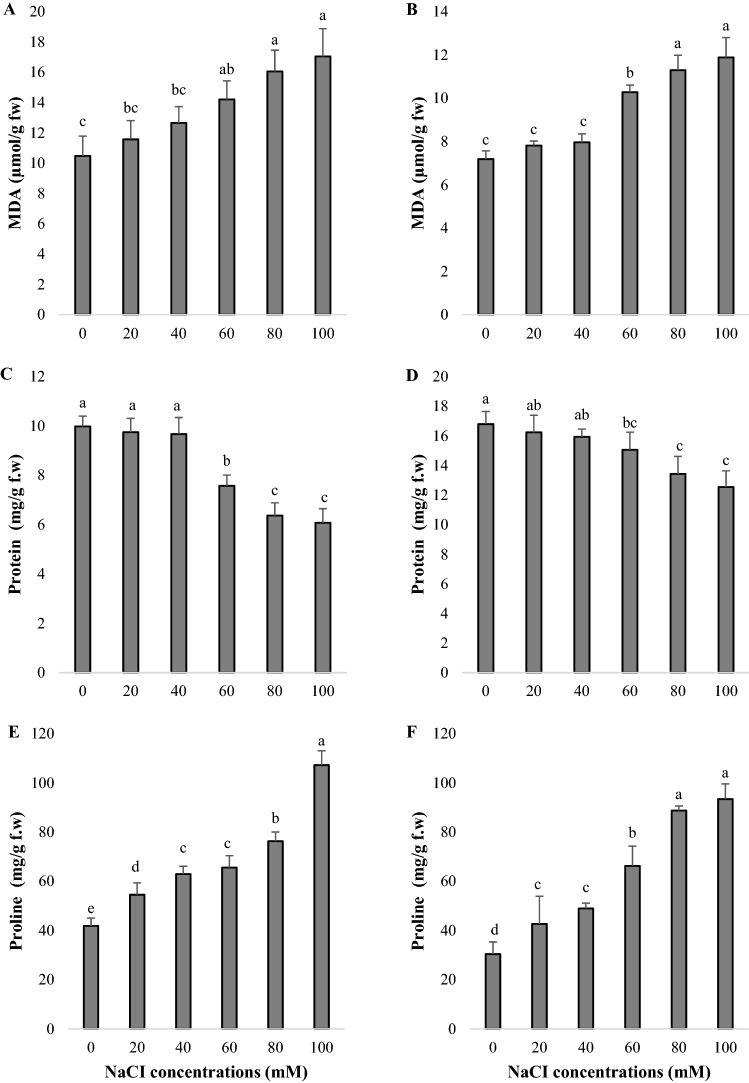

Lipid peroxidation

MDA contents were analysed to determine lipid peroxidation in shoots from callus under NaCl toxicity (Fig. 4a, b). The MDA contents of L. aromatica were between 10.47 and 17.05 µmol/g f.w (Fig. 4a) and the MDA contents of B. monnieri were listed as 7.19–11.88 µmol/g f.w (Fig. 4b). MDA contents of shoots increased with increasing NaCl concentration. Maximum increases in MDA contents of L. aromatica and B. monnieri were recorded in media containing 100 mM NaCl, 62.80% and 65.35% higher than the control, respectively. In low levels of NaCl, L. aromatica’s MDA content was higher than in B. monnieri. On the other hand, MDA levels measured in 80 and 100 mM NaCl applications were statistically insignificant in both plants (p < 0.05). A statistically significant association in the opposite direction was found between MDA contents and the number of shoots per callus in L. aromatica (r = − 0.795, p < 0.01) and B. monnieri (r = − 0.898, p < 0.01). On the other hand, a positive correlation was determined with proline level in L. aromatica (r = 0.838, p < 0.01) and B. monnieri (r = 0.927, p < 0.01) (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

The MDA, protein, and proline contents in regenerated shoots with different concentrations of NaCl. MDA (a, b) protein (c, d) and proline (d, e) contents in L. aromatica (a, c, e) and B. monnieri (b, d, f) after NaCl application. All values are the means of triplicates ± SD (n = 3). Vertical bars indicate standard error of three separate experiments. Different superscript letters indicate significantly different values (p < 0.05; DMRT)

Protein content

Changes in protein content of shoots under salt toxicity were shown in Fig. 4c, d. In both plant species, there were no statistically significant differences between the protein contents of shoots in 20 and 40 mM NaCI treated media and control group media. On the other hand, the increase in NaCl concentrations decreased the protein content significantly (p < 0.05). In L. aromatica, protein content rapidly reduced with 60 mM salt concentration, and the lowest protein content was found to be 39.11% lower than control in culture medium containing 100 mM NaCl (Fig. 4c). The minimum protein content in B. monnieri was determined in 100 mM salt application and as 25.33% lower than control (Fig. 4d). When the protein contents of the shoots were examined, the protein level of L. aromatica was lower than B. monnieri. According to Pearson’s correlation coefficients, significant positive relationships were found between protein contents and the number of shoots per callus in L. aromatica (r = 0.930, p < 0.01) and B. monnieri (r = 0.763, p < 0.01) (Table 3).

Proline content

The proline contents of the shoots were evaluated under increasing salt concentrations (Fig. 4e, f) and the obtained data were found statistically significant (p < 0.05). The lowest proline content was obtained in shoots not exposed to any salt. The proline content of shoots increased as salt concentration increased. The maximum content of proline was determined in culture medium containing 100 mM NaCl in both plant species. While a regular increase in proline content was observed in L. aromatica up to 80 mM NaCl, a significant increase in proline level was recorded with 100 mM NaCl application (Fig. 4e). The proline values obtained at 80 and 100 mM NaCl concentrations in B. monnieri were not statistically significant (Fig. 4f). A statistically significant relationship in opposite directions was determined between proline levels and the number of shoots per callus in L. aromatica (r = − 0.895, p < 0.01) and B. monnieri (r = − 0.902, p < 0.01) (Table 3).

Discussion

Salt stress has become a significant environmental problem limiting the vital activities of plants. For this reason, knowing the reactions of plants against salt toxicity is very important in terms of the selection and production of salt-resistant species. In this study, callus formation capabilities of L. aromatica and B. monnieri incubated under different salt concentrations, and the effect of salt on the emergence of regenerated shoots from these calluses were investigated. In addition, physiological and biochemical changes of salt toxicity in plants were evaluated. Salinity showed adverse effects on callus from nodal explants. The callus density decreased with increasing salt concentration, and some calluses became brown and lost the regenerative ability. Similarly, the reduction in the callus amount of plants with the salt application has previously been reported in Boswellia serrata Roxb (Ghorpade et al. 2011) and Triticum aestivum L. (Benderradji et al. 2012). In the current study, calluses were placed to the reproductive media including salt for proliferation, and the regenerated shoot numbers and shoot lengths decreased with increasing salt concentration. In parallel with these findings, Ahire et al. (2014) incubated the nodal explant of B. monnieri with increasing doses of KCl and CaCl2 (50–200 mM) and recorded significant decreases in the number of shoots, shoot extension, fresh and dry weight compared to the control. The adverse effect of salt concentration on in vitro shoot regeneration and shoot count of B. monnieri was also reported in Sable et al. (2018). These results suggest that salt stress prevents the regeneration ability of cells. This inhibitory effect was thought to originate from reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells. It is known that ROS is produced in cells under salt stress (Oukarroum et al. 2015). ROS interacts with several critical cellular molecules and metabolites such as DNA, pigments, proteins, lipids, and causes a series of destructive processes (Mittler 2002; Hong et al. 2009). In addition, increased ROS production leads to lipid and protein oxidation, nucleic acid depredation, enzyme detention, and death of cells (Büyük et al. 2012). Salt stress affects the division and prolongation of the cell and prevents the growth of plants and leads to a decrease in the number of cells, mitotic activity and cell division (Burssens et al. 2000).

Photosynthetic pigments are the most critical parameters for the growth-development of plants. Even the low negativities in their levels may adversely affect all the physiological and biochemical parameters of the plant (Gengmao et al. 2014; Esteban et al. 2015). Therefore, the effects of salt toxicity on photosynthetic pigments in the present study were investigated. In this current study, it was seen that increased NaCl concentration affected photosynthetic pigmentation. The levels of the effect of the plants showed differences in salt concentrations. The color loss (chlorosis), such as browning and yellowing, was observed in shoots. Husen et al. (2019) reported that different concentrations of NaCl (50–150 mM) stress inhibited chlorophyll synthesis, nitrate reductase activity, chlorophyll fluorescence, stoma conductivity, net photosynthesis and transpiration rates in Guizotia abyssinica. Similar to these findings, reductions in photosynthetic pigmentation as a result of salt toxicity have been previously described in Acorus calamus (Han et al. 2018), Glycine max L. (El-Esawi et al. 2018) and Medicago truncatula (Zhang et al. 2019).

The loss of colour, reductions in chlorophyll content and changes in photosynthetic activity in plants under the influence of salt have attracted the attention of many researchers. Decreases in chlorophyll content of the shoots in NaCl applications, as a result of degradation of membrane integrity with lipid peroxidation, was thought to be the disintegration of chlorophylls (Ashraf and Bhatti 2000). In another study, the decrease in chlorophyll content under salt stress was reported to be due to the degradation of chlorophylls with increased chlorophyllase enzyme activity and also due to the reduction of chlorophyll biosynthesis (Santos 2004). Also, NaCl affects electron transport activity by causing changes in the structure of proteins in chloroplast thylakoid (Sudhir et al. 2005).

One of the most important parameters examined in plant stress studies is lipid peroxidation. Lipid peroxidation is considered as a marker to determine the degree of toxicity of stress agents. For this purpose, the most known way to assess oxidative stress damage is to determine MDA content (Estévez 2015; Taïbi et al. 2013; Dogan et al. 2018). The physiological drought caused by salt stress creates an osmotic effect on a large number of metabolic activities and triggers ROS formation (Türkan and Demiral 2009). ROS may cause lipid peroxidation in the membrane and accordingly the cell permeability, composition and structure vary and membrane integrity deteriorates (Bose et al. 2014). It has been stated that the damage in the membranes is caused by overproduction of reactive oxygen species or by direct degradation of unsaturated fatty acids (Sairam et al. 2000). In the present study, MDA contents were evaluated in L. aromatica and B. monnieri to investigate the oxidative stress damage induced by salinity stress. The findings showed that MDA values increased with increasing salt dose in both plant species. In parallel with these findings, the decreases in MDA content of the plants during salt exposure were previously reported by Song et al. (2017), Moniruzzaman et al. (2018) and Gao et al. (2019). On the other hand, MDA contents of the plants in low salt applications were found to be statistically insignificant when compared to the control. These results suggest that the plants exposed to low salt concentration have parameters that can inhibit oxidative stress because phenolic compounds serve as a component of the cell wall, as a means of defence against biotic and abiotic environmental stressors during the growth-development stages (Taïbi et al. 2013).

Plants activate some internal mechanisms to prevent salt stress. Some of them are a synthesis of protective molecules such as osmolites (low molecular weight soluble substances), heat shock proteins and the synthesis of certain stress-induced proteins (Büyük et al. 2012). The osmolites was known as osmoprotectants (osmotic preservatives), both protect the cellular structure and also play a role as a free radical scavenger (Chinnusamy et al. 2005). In the present study, despite the synthesised protein-based osmolites, the total protein content of both plants decreased significantly with increasing salt toxicity. However, when the results were examined, the protein content of the shoots at low salt concentrations was found to be close to the control group. This demonstrated that the protein content of the plant was directly related to the applied salt concentration and duration. Furthermore, protein content lower than control may be an indication of catabolism higher than anabolism. Similarly, Hameed et al. (2008) recorded a decline in plant growth and protein content in wheat seedlings exposed to increasing NaCl.

While the protein content of the shoots from the callus decreased in the culture medium, proline contents increased. Several studies have shown that proline levels have been raised in plants exposed to salt stress (Calzone et al. 2019; Vanlalruati et al. 2019). Ali et al. (1999) reported that proline content in B. monnieri with NaCl toxicity under tissue culture conditions was increased six-fold higher than control. Husen et al. (2019) determined that proline production increased in G. abyssinica with increased salinity level.

Organisms accumulate various solutes in their cytosols to provide tolerance to abiotic stresses. Proline accumulates a few times more in stressed plants (Delaunay and Verma 1993). The proline accumulation in high plants is a physiological response to salt stress and accumulates more than other amino acids (Ábrahám et al. 2003; Verslues et al. 2006). Usually, proline accumulates in the cytosol and acts in the osmotic adjustment of the cytoplasm (Parvaiz and Satyawati 2008). It is thought that proline can tolerate the increase in redox potential by NADP formation and has a vital role in the defence mechanisms of stressed cells (Liang et al. 2013).

Conclusion

Tissue culture techniques help to examine plants’ multiple productions as well as their physiological and biochemical aspects. In particular, tissue culture applications are critical to monitor their response to stress conditions and to select tolerant species. In this study, the callus formation abilities of explants under different salt stress were investigated. The percentage of callus formation and callus density decreased with increasing salt concentration, and the color losses in the callus increased with salinity. Subsequently, these calluses were cultured in a nutrient medium containing increased salt concentration and increased NaCl concentration in both plant species adversely affected the regeneration ability of shoots. Based on these results, it was found that low salt stress didn’t have a significant effect on the in vitro production of the plants; however, high salinity rates were found to cause considerable destruction in physiological and biochemical parameters of the plants such as chlorosis, lipid peroxidation, and protein degradation. As a result of these destructions, the regeneration capacity of the shoots decreased, and deaths were observed in some callus and explants. This is a comprehensive study of the responses of L. aromatica and B. monnieri under in vitro salt stress. These findings can provide a better understanding of the salt stress mechanism of L. aromatica and B. monnieri and can create a basis for subsequent functional studies. The results of this study may also be a guide for L. aromatica and B. monnieri to give adaptability responses to growth in field conditions under different salt stress.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abogadallah GM. Insights into the significance of antioxidative defense under salt stress. Plant Signal Behav. 2010;5:369–374. doi: 10.4161/psb.5.4.10873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ábrahám E, Rigó G, Székely G, Nagy R, Koncz C, Szabados L. Light-dependent induction of proline biosynthesis by abscisic acid and salt stress is inhibited by brassinosteroid in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2003;51:363–372. doi: 10.1023/a:1022043000516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agır SU, Kutbay HG, Surmen B, Elmas E. The effects of erosion and accretion on plant communities in coastal dunes in north of Turkey. Rend Fis Acc Lincei. 2017;28:203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar S, Borowski T. Neuropharmacological review of the nootropic herb Bacopa monnieri. Rejuvenation Res. 2013;16(4):313–326. doi: 10.1089/rej.2013.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahire ML, Laxmi S, Walunj PR, Kavi Kishor PB, Nikam TD. Effect of potassium chloride and calcium chloride induced stress on in vitro cultures of Bacopa monnieri (L.) Pennell and accumulation of medicinally important bacoside A. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;23:366–378. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad R, Hussain S, Anjum MA, Khalid MF, Saqib M, Zakir I, Hassan A, Fahad S, Ahmad S. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense mechanisms in plants under salt stress. In: Hasanuzzaman M, Hakeem K, Nahar K, Alharby H, editors. Plant abiotic stress tolerance. Cham: Springer; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ali G, Srivastava PS, Iqbal M. Proline accumulation, protein pattern and photosynthesis in Bacopa monniera regenerants grown under NaCI stress. Biol Plant. 1999;42:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf MY, Bhatti AS. Effect of salinity on growth and chlorophyll content of rice. Pak J Sci Ind Res. 2000;43:130–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf M, Harris PJC. Potential biochemical indicators of salinity tolerance in plants. Plant Sci. 2004;166:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare ID. Rapid determination of free proline for water stres studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39:205–207. [Google Scholar]

- Benderradji L, Brini F, Kellou K, Ykhlef N, Djekoun A, Masmoudi K, Bouzerzour H (2012) Callus induction, proliferation, and plantlets regeneration of two bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes under saline and heat stress conditions. ISRN Agron. Article ID 367851

- Bose J, Rodrigo-Moreno A, Shabala S. ROS homeostasis in halophytes in the context of salinity stress tolerance. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:1241–1257. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmachari G. Limnophila (Scrophulariaceae): chemical and pharmaceutical aspects-an update. Open Nat Prod J. 2014;7:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bui ML, Grayer RJ, Veitch NC, Kite GC, Tran H, Nguyen QCK. Uncommon 8-oxygenated flavonoids from Limnophila aromatica (Scrophulariaceae) Biochem Syst Ecol. 2004;32:943–947. [Google Scholar]

- Bulle M, Yarra R, Abbagani S. Enhanced salinity stress tolerance in transgenic chilli pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) plants overexpressing the wheat antiporter (TaNHX2) gene. Mol Breed. 2016;36:36. [Google Scholar]

- Burssens S, Himanen K, Cotte BV, Beeckman T, Montagu MV, Inze D, Verbruggen N. Expression of cell cycle regulatory genes and morphological alterations in response to salt stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2000;211:632–640. doi: 10.1007/s004250000334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büyük İ, Soydam-Aydın S, Aras S. Bitkilerin stres koşullarına verdiği moleküler cevaplar. Türk Hijyen ve Deneysel Biyoloji . 2012;69:97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Calzone A, Podda A, Lorenzini G, Maserti BE, Carrari E, Deleanu E, Hoshika Y, Haworth M, Nali C, Badea O, Pellegrini E, Fares S, Paoletti E. Cross-talk between physiological and biochemical adjustments by Punica granatum cv. Dente di cavallo mitigates the effects of salinity and ozone stress. Sci Total Environ. 2019;656:589–597. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy V, Jagendorf A, Zhu JK. Understanding and improving salt tolerance in plants. Crop Sci. 2005;45:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Cominelli E, Conti L, Tonelli C, Galbiati M. Challenges and perspectives to improve crop drought and salinity tolerance. New Biotechnol. 2013;30:355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaunay AJ, Verma DPS. Proline biosynthesis and osmoregulation in plants. Plant J. 1993;4:215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Devendra SP, Preeti B, Santanu B, Gajanan D, Rupesh D. Brahmi (Bacopa monnieri) as functional food ingredient in food processing industry. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2018;7:189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Do QD, Angkawijaya AE, Tran-Nguyen PL, Huynh LH, Soetaredjo FE, Ismadji S, Ju YH. Effect of extraction solvent on total phenol content, total flavonoid content, and antioxidant activity of Limnophila aromatica. J Food Drug Anal. 2014;22:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan M. Multiple shoot regeneration from shoot tip and nodal explants of Rotala rotundifolia (Buch-Ham. ex Roxb) Koehne. Ant J Bot. 2017;1:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dogan M, Karatas M, Aasim M. An efficient in vitro plantlet regeneration of Ceratophyllum demersum L., an important medicinal aquatic plant. Fresenius Environ Bull. 2015;24:3499–3504. [Google Scholar]

- Dogan M, Karatas M, Aasim M. Cadmium and lead bioaccumulation potentials of an aquatic macrophyte Ceratophyllum demersum L.: a laboratory study. Ecotoxicol Environ Safe. 2018;148:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey V. Screening of some extracts of medicinal plants for antimicrobial activity. J Mycol Plant Pathol. 2002;32:266–267. [Google Scholar]

- El-Esawi MA, Alaraidh IA, Alsahli AA, Alamri SA, Ali HM, Alayafi AA. Bacillus firmus (SW5) augments salt tolerance in soybean (Glycine max L.) by modulating root system architecture, antioxidant defense systems and stress-responsive genes expression. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2018;132:375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsen B, Dogan M. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of in vitro propagated medicinal Ceratophyllum demersum L. extracts. Acta Sci Pol-Hortorum. 2018;17:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban R, Barrutia O, Artetxe U, Fernández-Marín B, Hernández A, García-Plazaola JI. Internal and external factors affecting photosynthetic pigment composition in plants: a meta-analytical approach. New Phytol. 2015;206:268–280. doi: 10.1111/nph.13186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estévez M. Oxidative damage to poultry: from farm to fork. Poult Sci. 2015;94:1368–1378. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao YL, Cui YJ, Long RC, Sun Y, Zhang TJ, Yang QC, Kang JM. Salt-stress induced proteomic changes of two contrasting alfalfa cultivars during germination stage. J Sci Food Agric. 2019;99:1384–1396. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.9331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gengmao Z, Quanmei S, Yu H, Shihui L, Changhai W. The physiological and biochemical responses of a medicinal plant (Salvia miltiorrhiza L.) to stress caused by various concentrations of NaCl. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e89624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbari M, Modarres-Sanavy SAM, Mokhtassi-Bidgoli A. Is time important in response of morpho-physiological parameters in Withania coagulans L. landraces to water deficit stress? Ind Crops Prod. 2019;128:18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorpade RP, Chopra A, Nikam TD. Influence of biotic and abiotic elicitors on four major isomers of boswellic acid in callus culture of Boswellia serrata Roxb. Plant Omics J. 2011;4:169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Gorai D, Jash SK, Singh RK, Gangopadhyay A. Chemical and pharmacological aspects of Limnophila aromatica (Scrophulariaceae): an overview. Am J Phytomed Clin Ther. 2014;2:348–356. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed A, Naseer S, Iqbal T, Syed H, Haq MA. Effects of NaCI salinity on seedling growth, senescence, catalese and protease activities in two wheat genotipes differing in salt tolerance. Pak J Bot. 2008;40:1043–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Han JQ, Zhou YM, Li DD, Zhai GQ. Effects of short-term high-salt stresses on photosynthetic characteristics, activities of protecive enzyme and copper uptake of Acorus calamus in microcosm submerged wetlands. Fresenius Environ Bull. 2018;27:982–988. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanein AM, Salem JM. Rise potassium content of the medium improved survival, multiplication, growth and scavenging system of in vitro grown potato under salt stress. Egypt J Bot. 2017;57:259–275. [Google Scholar]

- Heath RL, Packer L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts. I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968;125:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong CY, Chao YY, Yang MY, Cho SC, Kao CH. Na+ but not Cl− or osmotic stress is involved in NaCl induced expression of glutathione reductase in roots of rice seedlings. J Plant Physiol. 2009;166:1598–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husen A, Iqbal M, Khanam N, Aref IM, Sohrab SS, Masresha G. Modulation of salt-stress tolerance of niger (Guizotia abyssinica), an oilseed plant, by application of salicylic acid. J Environ Biol. 2019;40:96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jain SM. Tissue culture-derived variation in crop improvement. Euphytica. 2001;118:153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Jain PK, Das D, Jain P, Jain P. Pharmacognostic and pharmacological aspect of Bacopa monnieri: a review. Innov J Ayurvedic Sci. 2016;4:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kahlaoui B, Hachicha M, Misle E, Fidalgo F, Teixeira J. Physiological and biochemical responses to the exogenous application of proline of tomato plants irrigated with saline water. J Saudi Soc Agric Sci. 2018;17:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaji HM, Račková L, Paganová V, Swoczyna T, Rusinowski S, Sitko K. Can chlorophyll-a fluorescence parameters be used as bio-indicators to distinguish between drought and salinity stress in Tilia cordata Mill? Environ Exp Bot. 2018;152:149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Kean JD, Downey LA, Stough C. A systematic review of the Ayurvedic medicinal herb Bacopa monnieri in child and adolescent populations. Complement Ther Med. 2016;29:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gall H, Philippe F, Domon JM, Gillet F, Pelloux J, Rayon C. Cell wall metabolism in response to abiotic stress. Plants. 2015;4:112–166. doi: 10.3390/plants4010112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X, Zhang L, Natarajan SK, Becker DF. Proline mechanisms of stress survival. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:998–1011. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler H, Wellburn A. Determinations of total carotenoids and chlorophylls b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem Soc Trans. 1983;11:591–592. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin-phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. Oxidative stress, antioksidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:405–410. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moniruzzaman M, Mukherjee J, Jacquin L, Mukherjee D, Mitra P, Ray S, Chakraborty SB. Physiological and behavioural responses to acid and osmotic stress and effects of Mucuna extract in Guppies. Ecotoxicol Environ Safe. 2018;163:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns R. Genes and salt tolerance: bringing them together. New Phytol. 2005;167:645–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz K, Hussain K, Majeed A, Khan F, Afghan S, Ali K. Fatality of salt stress to plants: morphological, physiological and biochemical aspects. Afr J Biotechnol. 2010;9:5475–5480. [Google Scholar]

- Oseni OM, Pande V, Nailwal TK. A review on plant tissue culture, a technique for propagation and conservation of endangered plant species. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2018;7:3778–3786. [Google Scholar]

- Oukarroum A, Bussotti F, Goltsev V, Kalaji HM. Correlation between reactive oxygen species production and photochemistry of photosystems I and II in Lemna gibba L. plants under salt stress. Environ Exp Bot. 2015;109:80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Parvaiz A, Satyawati S. Salt stress and phyto-biochemical responses of plant—a review. Plant Soil Environ. 2008;54:89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Clemente RM, Gómez-Cadenas A. In vitro tissue culture, a tool for the study and breeding of plants subjected to abiotic stress conditions. In: Leva A, editor. Recent advances in plant in vitro. London: InTech; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rao JV, Aithal KS, Srinivasan KK. Antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Limnophila gratissima. Fitoterapia. 1989;60:376–377. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy SSS, Singh B, Peter AJ, Rao TV. Production of transgenic local rice cultivars (Oryza sativa L.) for improved drought tolerance using Agrobacterium mediated transformation. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2018;25:1535–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Riffat A, Ahmad MSA. Amelioration of adverse effects of salt stress on maize (Zea mays L.) cultivars by exogenous application of sulfur at seedling stage. Pak J Bot. 2016;48:1323–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Sable AD, Kardile PB, Sable AD, Kharde AV. Studies on effect of different concentration of NaCI on bacoside production from brahmi (Bacopa monnieri) under in vitro condition. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2018;7:1386–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Sairam RK, Srivastava GC, Saxena DC. Increased antioxidant activity under elevated temperature: a mechanism of heat stress tolerance in wheat genotypes. Biol Plant. 2000;43:245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Salem JM, Hassanein AM, Faheed FA, El-Nagish AA. Shoot regeneration and isoenzyme expression of Moringa oleifera under the influence of salt stress. Phyton-Ann Rei Bot A. 2017;57:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Santos CV. Regulation of chlorophyll biosynthesis and degradation by salt stress in sunflower leaves. Sci Hortic. 2004;103:93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Shao HB, Chu LY, AbdulJaleel C, Zhao CX. Water-deficit stress-induced anatomical changes in higher plants. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2008;331:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekhawat MS, Kannan N, Manokari M. In vitro propagation of traditional medicinal and dye yielding plant Morinda coreia Buch.–Ham. South Afr J Bot. 2015;100:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava P, Kumar R. Soil salinity: a serious environmental issue and plant growth promoting bacteria as one of the tools for its alleviation. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2015;22:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Palethorpe HM, Tomita Y, Pei JV, Townsend AR, Price TJ, Young JP, Yool AJ, Hardingham JE. The purified extract from the medicinal plant Bacopa monnieri, bacopaside II, inhibits growth of colon cancer cells in vitro by inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Cells. 2018;7:81. doi: 10.3390/cells7070081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical methods. Iowa: The Iowa State University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Song TT, Xu HH, Sun N, Jiang L, Tian P, Yong YY, Yang WW, Cai H, Cui GW. Metabolomic analysis of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) root-symbiotic rhizobia responses under alkali stress. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1208. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhir P, Pogoryelov D, Kovács L, Garab G, Murthy SDS. The effects of salt stress on photosynthetic electron transport and thylakoid membrane proteins in the cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;38:481–485. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2005.38.4.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taïbi K, Taïbi F, Abderrahim LA, Ennajah A, Belkhodja M, Mulet JM. Effect of salt stress on growth, chlorophyll content, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant defence systems in Phaseolus vulgaris L. South Afr J Bot. 2013;105:306–312. [Google Scholar]

- Türkan I, Demiral T. Recent developments in understanding salinity tolerance. Environ Exp Bot. 2009;67:2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Uabundit N, Wattanathorn J, Mucimapura S, Ingkaninan K. Cognitive enhancement and neuroprotective effects of Bacopa monnieri in Alzheimer’s disease model. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanlalruati AP, Kumar G, Tiwari AK. Effect of saline stress on growth and biochemical indices of chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium) germplasm. Indian J Agric Sci. 2019;89:41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Verslues PE, Agarwal M, Katiyar-Agarwal S, Zhu JH, Zhu JK. Methods and concepts in quantifying resistance to drought, salt and freezing, abiotic stresses that affect plant water status. Plant J. 2006;45:523–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Ma BL, Whalen JK. Enhancing rapeseed tolerance to heat and drought stresses in a changing climate: perspectives for stress adaptation from root system architecture. Adv Agron. 2018;151:87–157. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XX, Wang TZ, Liu M, Sun W, Zhang WH. Calmodulin-like gene MtCML40 is involved in salt tolerance by regulating MtHKTs transporters in Medicago truncatula. Environ Exp Bot. 2019;157:79–90. [Google Scholar]