Abstract

China successfully achieved universal health insurance coverage in 2011, representing the largest expansion of insurance coverage in human history. While the achievement is widely recognized, it is still largely unexplored why China was able to attain it within a short period. This study aims to fill the gap. Through a systematic political and socio-economic analysis, it identifies seven major drivers for China's success, including (1) the SARS outbreak as a wake-up call, (2) strong public support for government intervention in health care, (3) renewed political commitment from top leaders, (4) heavy government subsidies, (5) fiscal capacity backed by China's economic power, (6) financial and political responsibilities delegated to local governments and (7) programmatic implementation strategy. Three of the factors seem to be unique to China (i.e., the SARS outbreak, the delegation, and the programmatic strategy.) while the other factors are commonly found in other countries’ insurance expansion experiences. This study also discusses challenges and recommendations for China's health financing, such as reducing financial risk as an immediate task, equalizing benefit across insurance programs as a long-term goal, improving quality by tying provider payment to performance, and controlling costs through coordinated reform initiatives. Finally, it draws lessons for other developing countries.

Keywords: Health insurance, Universal coverage, Health care reform, China

1. Introduction

Universal health insurance coverage is rarely found in developing countries. That is why international experts are greatly impressed by the universal coverage recently achieved by China, the world's largest developing country with 1.3 billion population. For example, a World Bank report praised China's achievement as “unparalleled,” [1] representing the largest expansion of insurance coverage in human history. One study concluded that China's experience is “exemplary for other nations that pursue universal health coverage” [2]. The achievement also drew attention of the mass media [3]. While China's success in coverage expansion is widely recognized, few studies have systematically examined reasons for the success. This study aims to fill the gap. The study findings will help answer three questions that are of interest to policymakers and researchers both within and without China:

-

1.

What are the major drivers for China's achievement of universal health insurance coverage?

-

2.

What are the policy challenges for sustaining the achievement in the next decade?

-

3.

What lessons can be learned from China's experience?

To analyze these questions, this study drew data from public sources. It searched the PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) for journal articles published in English language, the China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database (http://www.cnki.net/) for journal articles published in Chinese language, and the Internet for mass media reports and government documents. Using the data, this paper first briefly summarizes China's achievement. Then it analyzes major drivers for the achievement before discussing policy challenges and recommendations. Finally it summarizes the lessons from China's experience.

2. China's achievement of universal health insurance coverage

China's achievement is impressive for both the scale of coverage expansion, which is the largest expansion in human history, and the speed of expansion—by 2011, 95% of Chinese population was insured, compared with less than 50% in 2005 (for a brief summary of the evolution of China's health care financing systems, see Table 1 ) [1]. The coverage is offered through three public insurance programs. Table 2 summarizes key features of the three programs.

-

1.

New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NRCMS), launched in 2003 in rural areas. Its enrollment rose to 97% of rural population in 2011 [4].

-

2.

Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URBMI), launched in 2007 to target the unemployed, children, students, and the disabled in urban areas. It covered 93% of the target population in 2010 [2].

-

3.

Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI), launched in 1998 as an employment-based insurance program. Its coverage reached 92% in 2010 [2].

Table 1.

Milestones in the evolution of China's Health Care Financing Systems, 1949–2011.

| Year(s) | Key events |

|---|---|

| 1949 | Founding of the People's Republic of China. |

| 1951 | Labor Insurance Scheme launched as an employment based health insurance program, targeting urban employers with 100 or more employees. |

| 1952 | Government Insurance System launched as a public insurance program for government employees, their dependents, and college students. |

| Late-1950s | Cooperative Medical Scheme appearing in rural areas as a prepayment health plan organized at the village level, and financed jointly by village collective fund, upper level government subsidies, and premium paid by farmers. |

| Mid-1970s | Cooperative Medical Scheme implemented in over 90% of villages, covering the vast majority of rural population. |

| 1978 | Economic reform initiated in rural areas with the agricultural collectives replaced by a new household-responsibility system. |

| 1980s | Cooperative Medical Scheme collapsed. |

| 1990s | Labor Insurance System crippled by rising health costs and inefficiency of state-owned enterprises. |

| 1998 | Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance launched in urban areas to replace both Labor Insurance Scheme and Government Insurance Scheme. |

| 2003 | New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme implemented nation-wide with heavy government subsidies to rebuild the health insurance system in rural areas. |

| 2007 | Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance launched with heavy government subsidies, targeting the unemployed, children, and the disabled in urban areas. |

| 2011 | Universal coverage achieved in China with more than 95% of its population insured. |

Table 2.

Summary of China's Three Public Insurance Programs, 2011.

| UEBMI | URBMI | NCMS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target population | Urban employees | Urban children, students, unemployed, disabled | Rural residents |

| Enrollment rate (%) | 92 | 93 | 97 |

| Number of enrollees (million) | 252 | 221 | 832 |

| As % of China's 1.3 billion population | 19 | 16 | 62 |

| Unit of enrollment | Individuals | Individuals | Households |

| Risk-pooling unit | City | City | County |

| Premium per person per year (US$) | 240 | 21 | 24 |

| Including government subsidy (US$) | 0 | 18 | 18 |

| Benefit coverage | |||

| Inpatient reimbursement rate (%) | 68 | 48 | 44 |

| % of counties or cities covering general outpatient care | 100 | 58 | 79 |

| % of counties or cities covering outpatient care for major and chronic diseases | 100 | 83 | 89 |

| Annual Reimbursement Ceiling | Six-times average wage of employee in the city | Six-times disposable income of local residents | Six-times income of local farmers |

| Overseeing government department | MOHRSS | MOHRSS | NHFP |

3. Significant factors for China's universal health insurance coverage

3.1. SARS outbreak as a wake-up call

To a large extent, China's recent coverage expansion represents a long-overdue government investment in the country's health care system. While the past three decades have witnessed China's economic take-off, the country's health care system has not kept pace with the economic development [5], [6]. As government officials became increasingly occupied by economic development, government health expenditures dropped from 37% of total health expenditures in 1980 to 18% in 2004 [7]. The economic reform also unexpectedly led to serious deterioration in insurance coverage [8], [9], with insurance rate falling to 5% and 38% in rural and urban areas respectively in 1998 [4], [10]. Many researchers were alarmed by the falling coverage, and some researchers started experimental studies in the 1990s in an effort to rebuild the health insurance system, especially in rural China [11], [12], [13]. While the studies produced a wealth of experience that was eventually drawn on by Chinese policymakers, the studies did not lead to immediate policy actions, especially at the national level. At the turn of the 21st century, deteriorating insurance coverage coupled with a rapid increase in health care costs pushed health care affordability to the top of the list of public's concerns [14].

However, Chinese leaders did not pay close attention to the concern until the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which spread from China to 37 countries with 775 deaths reported world-wide [15], [16]. The SARS also incurred huge economic losses [17]. Consequently, it served as a wake-up call to Chinese leaders, who recognized how underinvestment in the 1980s–1990s had led the health care system to be unprepared for an emergency [18]. Within several months of the SARS outbreak, Chinese leaders decided on massive investment in the public health system [12], including heavy subsidies for the nation-wide implementation of NRCMS, which marked a new era of health care financing in China.

3.2. Strong public support for government intervention in health care

Whereas the NRCMS implementation represented China's efforts to rebuild rural health insurance system, there were no similar efforts in urban areas in the three years after the SARS outbreak, resulting in dissatisfaction among urban residents as they had difficulty paying medical bills, or had to go without care [6]. Summarizing the wide-spread discontent, a report by a high profile think tank that is affiliated with the State Council, China's Cabinet, concluded that the health care reform before 2005 “was basically not successful” [19]. The report raised the political stake to a higher level because of its immediate popularity, and more importantly, its high profile authors, who rarely publicly criticize government policies. Therefore, it sparked a national debate about health care reform in 2005.

One unique feature of the debate is strong public support for government intervention in health care, making China differ greatly from many countries [20], [21]. Historically, both the famous “barefoot doctors” and the cooperative medical scheme, the predecessor of NRCMS, were keenly promoted by the governments in the 1960s–1970s [22]. Given the governments’ past success in the health sector, it is not surprising that Chinese people expected for renewed government role in the 2000s.

Another reason for the public support for government intervention is the problems caused by privatization of China's health care system. While China's governments never formally published any privatization policies, they reduced political and/or public funding support substantially and forced doctors and health care facilities to function much like for-profit entities [23], resulting in the phenomenon of de facto privatization as concluded by researchers of the Chinese health care system [24]. For example, the barefoot doctor system in rural China, which was once praised by WHO as a successful example of providing health care services in developing countries [25], [26], declined rapidly after China's economic reform started in 1978 because it no longer enjoyed political backing from the central government and financial support from local governments and communities [27]. By the late 1980s, barefoot doctors either became private practitioners or were lost to other professions [22]. As another example, although 95% of hospital are owned by the governments, public funding is approximately 10% of hospital revenue [28]. To make a profit, hospitals heavily relied on over-prescribing drugs and diagnostic tests [29], [30], [31]. As a result, drug spending was about half of China's health expenditures, one of the highest shares in the world [32]. The privatization-induced overuse exacerbated the problem of health care affordability [33].

The public's concern with health care privatization is also due to a serious side-effect of China's market-oriented economic reform, which caused millions of employees to lose their jobs in the 1990s [34]. For the unemployed, the terms of market-orientation and privatization inflict painful memories, including their losing health insurance coverage [34], [35]. To correct the so-called “market failures”, many researchers proposed for stronger government intervention in the health sector [36]. As a counterargument, several researchers who noted that the limited market mechanism ambiguously defined by the governments has distorted the health care system called for market-oriented reform [21], [37]. Because it was not well received by government officials [38], the counterargument was barely discussed in the 2009 national health care reform plan [39].

3.3. Renewed political commitment from top leaders

In response to the public's concerns and expectations, Chinese leaders held a high profile workshop in 2006, at which President Hu Jintao committed to health care reform by stressing that “The goal of reform is for everyone to enjoy basic health care services” [40]. After releasing the reform plan in 2009, the central government formally reasserted its role in health care with unprecedented funding of 850 billion Chinese Yuan (about US$124 billion) for five reform programs—expanding coverage, establishing a national essential drug list, improving primary care, promoting equal access to public health services and piloting public hospital reform programs [41], [42].

There are two political reasons behind the renewed government support. First, contrary to a misunderstanding by many observers [43], socialism remains China's official ideology, obligating its governments to improve its people's social well-being, including health care. The obligation may not be fulfilled for some time (e.g., in the 1980s–1990s when the governments focused on improving economic indicators), but it cannot be completely ignored by the governments as long as the state ideology remains unchanged [43]. The historical success in the 1960s–1970s when China was praised as an innovator in health care by the World Health Organization [20], [44], also reinforced the obligation in the 2000s after the 30-year economic growth. Thus, in 2004, Chinese leaders announced NRCMS as an integral part of their efforts to build the “new socialist countryside”, an initiative to boost rural development [33]. The fact that NRCMS, a health insurance program, carries the socialist label illustrates the impact of state ideology on contemporary Chinese society [40], [45].

Second, the reinstated government role in health care is consistent with China's new development strategy, which shifted from prioritizing economic development (so-called GDP-ism) to an emphasis on building a harmonious society to promote equity and improve social stability [41], [43]. The new strategy reflected the leadership's recognition that economic growth does not necessarily lead to better health care [43]. The recent government support for health care is an important part of China's efforts to balance social development against economic growth.

3.4. Heavy government subsidies for health insurance

By 2011, government subsidies accounted for 75 and 85% of the premiums of NRCMS and URBMI respectively [2], making these insurance programs very attractive investment options. The heavy subsidies are critical for coverage expansion. For example, although Chinese governments attempted to establish NRCMS in 1996, the NRCMS coverage stayed at very low level until the subsidies were announced in 2003 [46]. Within five years of the announcement, the subsidies increased fourfold [21], and along with the increased subsidies, the NRCMS enrollment rose to 800 million people [4].

3.5. Fiscal capacity backed by China's economic power

With its fiscal capacity significantly strengthened by the double-digit economic growth in the past 30 years, Chinese governments can afford to subsidize one billion people's health insurance. Despite the large scale investment, government health expenditures are still a small proportion of total government expenditures (at 12.5% in 2011).

3.6. Engagement with local governments through delegating financial and political responsibilities

As a unique feature of China's health care reform, the central government required local governments not only to share the premium subsidies, but also to take political responsibilities for expanding coverage. The State Council's Health Reform Office signed “responsibility forms” – effective political contracts – with provincial governments, which further delegated tasks through contracts with municipal or county governments. The contract required that performance evaluation criteria for provincial and local officials include specific targets, such as 90% coverage by NRCMS or URBMI. Not achieving these targets would lead to poor scores for the performance evaluation of local officials, and have negative impacts on their future promotion. With the delegated political responsibilities, local officials took considerable time and efforts to intensify outreach and enrollment activities.

3.7. Programmatic strategy of health care reform

Last but not least, China's universal health insurance coverage is attributed to its programmatic strategy of first achieving wide but shallow coverage before expanding benefits. According to the strategy, both NRCMS and URBMI covered inpatient services only when they were launched. Then, the two programs started to cover outpatient services in 2010. The governments also added to these programs a list of priority diseases for enhanced benefit coverage [47]. After the reform's first stage of implementation in 2009–2011, the central government decided in 2012 on further reforms to expand insurance benefits, improve coverage portability, and encourage complementary coverage by private insurance. Such a programmatic strategy through multi-stage implementations ensures China to proceed steadily towards better access for its citizens.

4. Policy challenges and recommendations

While it is remarkable that China achieved universal health insurance coverage within a short period, the country is still facing daunting challenges in health care financing, some of which are highlighted below.

4.1. Reducing financial risk as an immediate task

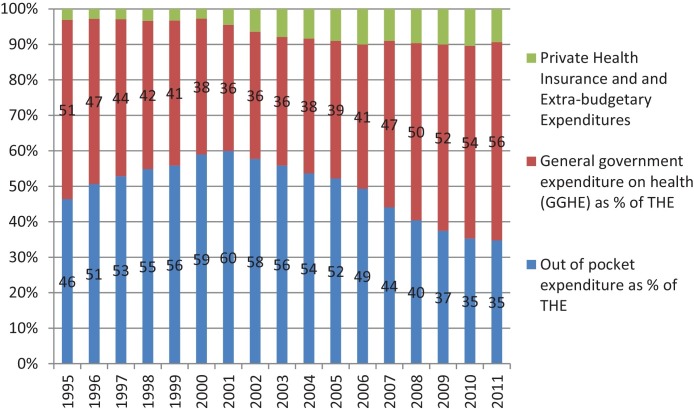

The level of benefit coverage is modest, as indicated in Table 2. For example, the reimbursement rate of inpatient care was relatively low in 2011, ranging from 44 to 68% among the three public insurance programs, all of which left the insured to bear a relatively large share of the burden of inpatient care. The low benefit level was a direct result of the modest premiums. Table 2 shows that the annual premium was only US$24 and US$21 for NRCMS and URBMI, respectively, both of which were too low to offer any generous benefit coverage. Not surprisingly, the published evidence is equivocal about whether China's coverage expansion reduced patients’ financial risk [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53]. At the national level, the proportion of out-of-pocket expenditures to total national health expenditures was significantly reduced from 60% in 2001 to 35% in 2011 (Fig. 1 ). However, the proportion was still higher than the average level of 33% among the group of upper-middle-income countries, to which China belongs [1].

Fig. 1.

Health expenditures by sources, 1995–2011.

Source: World Health Organization (see http://apps.who.int/nha/database).

China's Minister of Health publicly acknowledged that the financial risk remained high in the context of universal health insurance coverage [54]. To address the issue, the government has raised the ceiling of public insurance reimbursement with the goal of reducing out-of-pocket payment to 30% of total health expenditures by 2018. China's efforts of financial risk reduction can be more effective through reinsurance plans as discussed below.

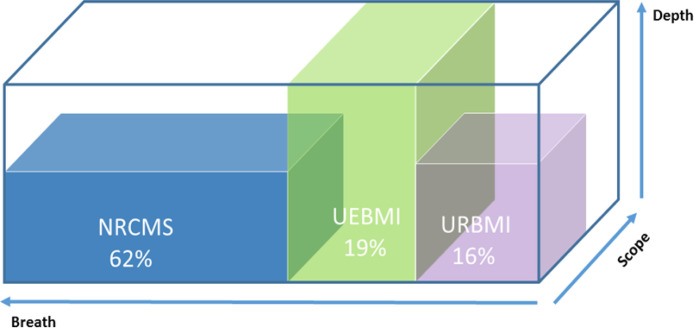

4.2. Equalizing benefit coverage across insurance programs as a long-term goal

There is a wide gap in premiums across insurance programs with UEBI having premiums 10 times higher than either URBMI or NRCMS [2]. The gap in premiums leads to substantial benefit variations across insurance programs as indicated in Table 2. For example, the reimbursement rate for inpatient care was only 44% for NRCMS in 2011, much lower than the rate of 68% for UEBMI [52]. As illustrated in Fig. 2 , the three major insurance programs differed greatly from each other in the coverage dimensions defined by the World Health Organization, including breath (% of population covered), depth (% of health costs covered) and scope (type of health services covered) [55]. Whereas the breath of NRCMS is the largest, covering 62% of population in 2011, it lagged behind other two insurance programs in terms of either depth or scope. Such disparities exist despite of the governments’ efforts to promote equitable health care [56].

Fig. 2.

Variation in coverage dimensions across the three insurance programs.

The persistent disparities impose one of the most challenging issues on China, which is still in the process of rapid industrialization and urbanization. In particular, eliminating the rural–urban disparities in insurance benefit requires reform measures that go beyond the health sector because the disparities are closely related to China's household registration system maintained by Ministry of Public Security (MOPH), which separates rural residents from their urban counterparts with favorable social programs provided for the latter. MOPH planned to set up a new registration system by 2020 to eliminate the discrimination again rural residents [57]. It might not be possible to equalize the benefit coverage across insurance programs until the new registration system is established. The governments may want to gradually reduce the rural–urban disparities in insurance benefit before running the new registration system.

4.3. Targeting specific populations, such as migrant workers, as a priority

China had approximately 236 million migrant workers in 2012 [58], who are farmers seeking employment in cities. Although they work and live in cities, the migrant workers are still listed as rural population in the current household registration system, and consequently they are enrolled in their hometowns’ NRCMS. Such arrangements caused two problems. (1) Most migrant workers cannot afford for health care in cities since the NRCMS benefit coverage is lower than the URBMI or UEBMI. (2) Those workers who seek health care in cities have to go back to their hometowns to get reimbursement. Several cities have piloted programs to allow migrant workers to enroll in URBMI or UEBMI. Policymakers need to evaluate the pilot programs, and to scale up those programs that are determined successful.

4.4. Improving quality by tying provider payment to performance

Given the unprecedented government investment in health care, policymakers are keenly interested in knowing whether the investment leads to higher value for patients. The rising income also enables Chinese people to demand higher quality of care. To satisfy the demand, policymakers need to push for quality improvement, especially by tying provider payment by the three public insurance programs to provider performance.

4.5. Controlling costs through coordination between insurance reform and other reforms

To address the public's concern about the rapid growth of health care costs [6], China's policymakers have launched several initiatives, such as the zero-profit drug policy, which aims to diminish profit-making activities by eliminating mark-ups on drugs dispensed by hospitals. They need to do more to control health care costs, especially through coordination between the insurance reform and other reform initiatives. For example, after China's success in insurance expansion, a large share of hospital revenues came from user charges that the three public insurance programs reimbursed. The policymakers may want to use the large amounts of insurance reimbursement as a useful tool for the ongoing hospital reform initiative to push hospitals for improving quality of care, reducing waste and inefficiency, and controlling growth of health expenditures. One option is to tie the insurance programs’ reimbursement to hospital performance in improving quality and reducing waste and inefficiency as discussed above. Another option is to reform the insurance programs’ provider reimbursement systems by replacing the fee-for-service payment method with prospective methods, such as capitation payment to primary care physicians, diagnosis-group-adjusted payment to hospitals, and bundled payment. As indicated by prior research [2], the policymakers may want to ensure that all the three insurance programs use the same payment method and that providers do not compromise quality of care to reduce costs under the new method.

4.6. Defining clearly the role for private insurance

Private health insurance is relatively new to China, covering 3.8% of national health spending in 2010 [59]. Demand for private insurance will increase substantially as more Chinese people join the middle class and look for better health care [60]. The central government, which intends the three public insurance programs to cover only basic health care, has decided to actively develop private insurance market to meet the additional needs of the publicly insured. However, the central government has not yet defined clearly the role for private insurance to play in China's health financing system. Without a clearly defined role, developing private insurance in China might raise concerns about inequality given prior study findings of negative impacts of supplemental private insurance on health care outcomes in countries with universal health insurance coverage [61], [62]. China's efforts to develop private insurance can be strengthened by (1) requiring the three public insurance programs to work with private insurance companies on reinsurance plans to mitigate the financial risk of the publicly insured and (2) investing in the country's health information system and training of health insurance experts, both of which will enable private insurers to differentiate their products to meet the consumers’ diverse needs, rather than to engage in the current price competition on similar portfolios [63].

4.7. Conducting rigorous evaluations

Given its huge size and unbalanced socio-economic development across regions, China needs to conduct rigorous evaluations of its insurance programs to determine whether the programs meet its citizens’ diverse and growing needs of health care. Some experts suggested that China should establish an “independent commission” for monitoring and evaluation [64]. Chinese officials also promised to support independent evaluations [65]. But they have not made concrete efforts to facilitate such evaluations, e.g., by making many government-maintained datasets “more open, transparent, and accessible to academics and the general public” [64]. It remains to be seen whether China can keep the promise of independent evaluations.

5. Conclusion and discussion

This paper identifies seven factors for China's universal health insurance coverage. Three of the factors seem to be unique to China, including (1) the SARS outbreak, a public health crisis that increased sharply political pressure for coverage expansion, (2) the financial and political responsibilities delegated to local governments, which mobilized local officials to intensify outreach and enrollment campaigns and (3) the programmatic strategy, which led quickly to wide but shallow coverage.

Other factors identified in this paper can also be found in other countries’ experiences. As noted by prior research, “universal health coverage is everywhere accompanied by a large role for government” [66]. In China's experience, the government role includes (1) the top leaders’ commitment that was decisive for China's embarking on a path towards universal coverage, (2) the heavy government subsidies that facilitated insurance enrollment and (3) the fiscal capacity that contributes to both China's decision on and its implementation of coverage expansion.

Pursuing universal coverage is an ongoing “global health transition” [67], for which China's experience offers several lessons. First, China joined a group of countries (e.g., Japan and Korea) that achieved universal health insurance coverage before becoming high-income countries [68]. The significance of China's experience is that it reached universal coverage during its process of industrialization and urbanization, setting an encouraging example for other countries involved in similar processes.

Second, China's programmatic strategy of providing wide but shallow coverage before expanding benefits offers a practical lesson for other developing countries to target large rural populations with relatively low income and high uninsurance rate.

Third, a crucial factor that underlies the large government role in China's universal coverage is the strong public support for government intervention in health care. Without the strong public support, it could be difficult to reach universal coverage.

Forth, the study found that China's universal coverage was driven by a combination of some factors unique to China and the factors commonly found in other countries’ coverage expansion experiences. One lesson that other developing countries can derive from this finding is that, to find their own path to universal coverage, they may want to adopt a combination strategy by taking advantage of both the unique characteristics of their own health care systems and some common factors that are shared with other countries’ coverage expansion experiences. Such a combination strategy can be helpful for them to design coverage expansion options that are socio-politically feasible in their national contexts.

Finally, in its new stage of health care reform, China now shares some common challenges with other countries with universal health insurance coverage, such as quality improvement and cost control. How China is going to address those challenges will be of international interest. We hope to report back in several years on China's progress in addressing the challenges.

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by the RAND Center for Asia Pacific Policy. The funder has not been involved in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The author participated in China's health care reform in the 1990s as an academic researcher and through his involvement with the Shanghai Municipal Government. The author certifies that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript. The author is grateful to Shanwen Yu for her efficient assistance with Fig. 2, and the two anonymous referees and the editors of Health Policy for their comments.

Footnotes

Open Access for this article is made possible by a collaboration between Health Policy and The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

References

- 1.Liang L., Langenbrunner J.C. Vol. 9. World Bank; Washington DC: 2013. (The long march to universal coverage: Lessons from China. Universal Health Coverage (UNICO) studies series). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yip W.C.-M., Hsiao W.C., Chen W., Hu S., Ma J., Maynard A. Early appraisal of China's huge and complex health-care reforms. The Lancet. 2012;379(9818):833–842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61880-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan N, Loo D. China-Style Obamacare for 1 Billion People Saves Toddler, Bloomberg News; September 10, 2013.

- 4.Meng Q., Tang S. Universal health care coverage in China: Challenges and opportunities. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2013;77(0):330–340. [22.04.2013] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang S., Meng Q., Chen L., Bekedam H., Evans T., Whitehead M. Tackling the challenges to health equity in China. The Lancet. 2008;372(9648):1493–1501. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61364-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu S., Tang S., Liu Y., Zhao Y., Escobar M.-L., de Ferranti D. Reform of how health care is paid for in China: Challenges and opportunities. The Lancet. 2008;372(9652):1846–1853. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L. China Healthcare Reform, A presentation at China Center for Economic Research, Peking University, Beijing, China; July 20, 2007.

- 8.Xueshan F., Shenglan T., Bloom G., Segall M., Xingyuan G. Cooperative medical schemes in contemporary rural China. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;41(8):1111–1118. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00417-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y. Reforming China's urban health insurance system. Health Policy. 2002;60(2):133–150. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(01)00207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang N., Gericke C., Sun H. Comparison of health care financing schemes before and after market reforms in China's urban areas. Frontiers of Economics in China. 2009;4(2):173–191. [01.06.2009] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrin G., Ron A., Hui Y., Hong W., Tuohong Z., Licheng Z. The reform of the rural cooperative medical system in the People's Republic of China: Interim experience in 14 pilot counties. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;48(7):961–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagstaff A., Lindelow M., Wang S., Zhang S. The World Bank; Washington DC: 2009. Reforming China's rural health system. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu H, Lucas L. Financing health care in poor rural counties in China: Experiences from a township-based co-operative medical scheme. IDS Working Paper 66, the Institute of Development Studies, at the University of Sussex, Brighton, BN1 9RE, UK; 1998.

- 14.Fan M. Health care tops list of concerns in China. Washington Post; January 10, 2008. p. 7.

- 15.World Health Organization . 2004. Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003. Available from: 〈http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2004_04_21/en/index.html〉 [accessed on 08.08.13] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith R.D. Responding to global infectious disease outbreaks: Lessons from SARS on the role of risk perception, communication and management. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(12):3113–3123. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J, McKibbin W. Estimating the global economic costs of SARS. In: Knobler S, Mahmoud A, Lemon S, et al., editors. Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats. Learning from SARS. Preparing for the Next Disease Outbreak. Workshop Summary. Washington DC: National Academies Press, US; 2004. [PubMed]

- 18.Dong Z, Phillips MR. Evolution of China's health-care system. The Lancet.372(9651):1715-1716. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Ge Y., Gong S. China Development Press; Beijing: 2007. China's health care reform: Problems, causes, and solutions. [June] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Bank Office in Beijing. Quarterly Update, November 2005. Washington DC: The World Bank; 2005.

- 21.Wang H. A dilemma of Chinese healthcare reform: How to re-define government roles? China Economic Review. 2009;20(4):598–604. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang D., Unschuld P.U. China's barefoot doctor: Past, present, and future. The Lancet. 2008;372(9653):1865–1867. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blumenthal D., Hsiao W. Privatization and its discontents—The evolving Chinese health care system. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(11):1165–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr051133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Geyndt W, Zhao X, Liu S. From barefoot doctor to village doctor in rural China. World Bank Technical Paper No. 187. Asia Technical Department Series, Washington DC: World Bank; 1992.

- 25.Cui W. China's village doctors take great strides. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86(12):909. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.021208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Z. A retrospective study on Chinese rural cooperative medical system. Chinese Rural Health Care Management. 1994;14:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu N.S., Ling Z.H., Shen J., Lane J.M., Hu S.L. Factors associated with the decline of the cooperative medical system and barefoot doctors in rural China. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1989;67(4):431–441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tao D., Hawkins L., Wang H., Langenbrunner J., Zhang S., Dredge R. The World Bank; Washington DC: 2010. Fixing the public hospital system in China. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma J., Lu M., Quan H. From a national, centrally planned health system to a system based on the market: Lessons from China. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2008;27(4 [July–Aug]):937–948. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsiao W.C.L. The Chinese health care system: Lessons for other nations. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;41(8):1047–1055. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00421-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martineau T., Gong Y., Tang S. Changing medical doctor productivity and its aff ecting factors in rural China. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2004;19(2):101–111. doi: 10.1002/hpm.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.OECD Library. Health at a glance: Europe. Available from: 〈http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-europe-2010_health_glance-2010-en〉; 2010 [accessed 08.06. 13].

- 33.Watts J. China's rural health reforms tackle entrenched inequalities. The Lancet. 2006;367(9522):1564–1565. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68675-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Economist. Privatisation with Chinese characteristics: The hidden costs of state capitalism; September 3, 2011. Available from: 〈http://www.economist.com/node/21528264〉 [accessed on 08.10.13].

- 35.Du J. Economic reforms and health insurance in China. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;69:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu L. Health care reform: A different viewpoint—An inclusive interview with professor Ling Li, Southern Weekend; October 10, 2007. Available from: 〈http://www.infzm.com/content/7768/2〉 [accessed 08.08.13].

- 37.Zhang Y, Li L. Directions of future health care reform: To be dominated by the government or by the market? Daily News of Law; January 1, 2007.

- 38.Shou P. Gao Qiang (The Minister of Health): Health care reform can never follow the route of marketization. Southern Weekend; March 15, 2007.

- 39.Yang Y. New plan for health care reform: Abandoning the path to be dominated by the market and responding to the public's demand (Editorial). China Net; April 8, 2009.

- 40.Xinhua News Agency. Hu Jintao: Building up a basic health care system to cover both urban and rural residents–A speech at the 35th study session of the 16th Central Committee's Political Bureau; October 24, 2005. Available from: 〈http://politics.people.com.cn/GB/1024/4954631.html〉 [accessed 18.06.10].

- 41.Central Committee of the Communist Party, State Council of People's Republic of China. The standing conference of State Council of China adopted guidelines for furthering the reform of health-care system in principle. Available from: 〈http://news.xinhuanet.com/newscenter/2009-04/06/content_11138803.htm〉 (in Chinese), [accessed 05.07.11].

- 42.China SCoPsRo. Current major tasks on health care system reform (2009–2011). Available from: 〈http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2009-04/07/content_1279256.htm〉 (in Chinese) [accessed 18.07.2010].

- 43.Breslin S. Why growth equals power—And why it shouldn’t: Constructing visions of China. Journal of Asian Public Policy. 2008;1(1):3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cueto M. The ORIGINS of primary health care and SELECTIVE primary health care. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(11):1864–1874. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.11.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng C. President Hu promises bigger government role in public health. China Daily; October 24, 2006. Available from: 〈http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2006-10/24/content_715952.htm〉 [accessed 10.03.10].

- 46.Bloom G. Building institutions for an effective health system: Lessons from China's experience with rural health reform. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(8):1302–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China. Report on women and children's health development in China. Beijing, China: Ministry of Health; 2011.

- 48.Lei X., Lin W. The new cooperative medical scheme in rural China: Does more coverage mean more service and better health? Health Economics. 2009;18(S2):S25–S46. doi: 10.1002/hec.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagstaff A., Lindelow M. Can insurance increase financial risk?: The curious case of health insurance in China. Journal of Health Economics. 2008;27(4):990–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun Q., Liu X., Meng Q., Tang S., Yu B., Tolhurst R. Evaluating the financial protection of patients with chronic disease by health insurance in rural China. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2009;8(1):42. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun X., Jackson S., Carmichael G., Sleigh A.C. Catastrophic medical payment and financial protection in rural China: Evidence from the new cooperative medical scheme in Shandong province. Health Economics. 2009;18(1):103–119. doi: 10.1002/hec.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meng Q., Xu L., Zhang Y., Qian J., Cai M., Xin Y. Trends in access to health services and financial protection in China between 2003 and 2011: A cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2012;379(9818):805–814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Babiarz K.S., Miller G., Yi H., Zhang L., Rozelle S. New evidence on the impact of China's New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme and its implications for rural primary healthcare: Multivariate difference-in-difference analysis. British Medical Journal. 2010;341:c5617–c5626. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Han Y. China's Minister of Health Publicly Acknowledges That Out-of-Pocket Medical Expenditures Are Still High. United Daily News (Lian He Zao Bao); January 7, 2011.

- 55.WHO. Sustainable health financing, universal coverage and social health Insurance. Ninth plenary meeting; 2005. Eighth report.

- 56.Brixi H, Mu Y, Targa B, Hipgrave D. Equity and public governance in health system reform challenges and opportunities for China. Policy Research Working Paper 5530, Washington DC: The World Bank; 2011.

- 57.Huang M. Vice Minister of Public Security: Setting up New Household Registration System by 2020. CCTV News Channel; December 17, 2013. Available from: 〈http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2013-12-17/062329002775.shtml〉 [accessed 20.12.13].

- 58.Gan B. China's 2013 Report on the development of migrant Populations released. Health Daily; September 11, 2013.

- 59.Barber SL, Yao L. Health insurance systems in China: A briefing note. World Health Report (2010). Background Paper 37. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- 60.Pressly L. Middle class China turns to private health insurance. BBC News; 18 July 2011. Available from: 〈http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-14141740〉 [accessed 08.10.13].

- 61.Renahy E, Quesnel-Vallée A. Private health insurance and health inequalities in a national health system. Available from: 〈http://paa2014.princeton.edu/papers/140623〉 [accessed 18.06.14].

- 62.Carme B., Fernandez E., Schiaffino A., Benach J., Rajmil L., Villalbí J. Social class inequalities in the use of and access to health services in Catalonia, Spain: What is the influence of supplemental private health insurance? International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2001;13(2):117–125. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/13.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ng A., Dyckerhoff C.S., Then F. Private health insurance in China: Finding the winning formula. Health International. 2012;12:75–82. [Published by McKinsey & Company, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen L., Xu D. Trends in China's reforms: The Rashomon effect. The Lancet. 2012;379(9818):782–783. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60285-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chou Y. Minister of Health, Chen Zhu: China will evaluate the implementation of health care reform. Xinhua News Agency; June 4, 2010. Available from: 〈http://news.sohu.com/20100614/n272803746.shtml〉 [accessed 08.10.13].

- 66.Savedoff W.D., de Ferranti D., Smith A.L., Fan V. Political and economic aspects of the transition to universal health coverage. The Lancet. 2012;380:332–924. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rodin J., de Ferranti D. Universal health coverage: the third global health transition? The Lancet. 2012;380:861–862. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wagstaff A. Health systems in East Asia: What can developing countries learn from Japan and the Asian Tigers? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3790, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433, USA; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Xing-Yuan G., Sheng-Lan T. Reform of the Chinese health care financing system. Health Policy. 1995;32(1–3):181–191. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(95)00735-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]