Abstract

Background

Hajj is the world’s largest annual mass gathering that attracts two to three million Muslims from around the globe to a religious assemblage in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. The risk of acquisition and transmission of influenza among Hajj pilgrims is high. Therefore, influenza vaccination is recommended, and was monitored frequently among pilgrims from different countries. However, the vaccination uptake among Saudi pilgrims has not been assessed in recent years.

Objective

This analysis aims to evaluate influenza vaccine uptake among Saudi Hajj pilgrims, and identify the key barriers to vaccination.

Method

Data on influenza vaccination were obtained from Saudi pilgrims who took part in a large trial during the Hajj of 2013, 2014 and 2015. Pilgrims were met and recruited in Mina, Makkah during the peak period of Hajj and were asked to complete a baseline questionnaire that recorded their influenza vaccination history, including reason(s) for non-receipt of vaccine.

Results

A total of 6974 Saudi pilgrims aged between 18 and 95 (median 34) years were recruited; male to female ratio was 1:1.2. Of the total, 90.8% declared their influenza vaccination history, 51.3% of them reported receiving influenza vaccine before travel to Hajj. The vaccination rates for the years 2013, 2014 and 2015 were 21.4%, 48.2% and 58.1%, respectively (P < 0.001). Of 1,269 pilgrims who were at higher risk of severe disease, 54.5% received the vaccine. Lack of awareness (47.5%), reliance on natural immunity (15.8%) and being busy (15.5%) were the main reasons for non-receipt.

Conclusion

These data from a convenience sample indicate that influenza vaccine uptake among Saudi Hajj pilgrims is increasing over years but still needs further improvement. Lack of awareness and misperceptions are the main barriers. Education of Saudi pilgrims and health professionals is required to raise awareness about influenza vaccination. Further studies are needed to understand pilgrims’ misperceptions.

Keywords: Hajj, Influenza, Vaccine, Influenza vaccine, Vaccine uptake, Saudi Arabia

1. Introduction

Hajj is the largest annual mass gathering event in the world. It attracts two to three million Muslims from around the globe to Makkah, Saudi Arabia. A high proportion of Hajj attendees are from Saudi Arabia [1]. The main health hazards for pilgrims at Hajj are respiratory infections, including influenza [2], [3], [4]. It has been reported that over 90% of pilgrims develop at least one respiratory symptom before they return to their home countries [5]. In particular, the rate of laboratory-confirmed influenza among symptomatic pilgrims was observed to range between 4% and 15% [6], [7]. Moreover, the risk of acquiring respiratory viral infections, including influenza, increased significantly after Hajj [6], the risk estimated to be eight times higher than that in community settings [8]. Besides, influenza poses substantial public health risk to the host country [9]. Therefore, the Saudi Ministry of Health has been recommending influenza vaccination for all Hajj pilgrims since 2005, particularly those at higher risk from influenza [10], [11].

Several studies have estimated the uptake of influenza vaccine among Hajj pilgrims. These studies show that, since 2005, the vaccination rate has fluctuated widely over years [12]. Studies reported seasonal influenza vaccination rate to range from 0.7% to 100% among pilgrims, with the highest coverage in 2009, the pandemic year, when the Saudi Arabian authorities stridently stressed on vaccine receipt [13].

Studies have also shown substantial variation in vaccination rates among pilgrims from different countries. Iranian pilgrims reported satisfactory influenza vaccine uptake that generally ranged between 76% and 88% in the years between 2004 and 2010, reaching up to 100% in 2009 [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Similarly, Australian pilgrims had an acceptable vaccine uptake ranging between 65% and 89% in the years 2011 to 2013, even though pilgrims from Australia comprise less than 1% of the total Hajj pilgrims in a given year [19], [20]. The vaccination rate among Malaysian pilgrims in 2013 was reported as 65%, and the uptake among Indian pilgrims reached up to 72% in 2014 [21], [22]. On the other hand, the uptake in 2005 and 2006 ranged between 27% and 37% among French and UK pilgrims [23], [24], [25], [26]. Several studies measuring influenza vaccination rate among French pilgrims revealed vaccine uptake that fluctuated generally between 26% and 46% over the years 2006 to 2013, with extremes of up to 97% in 2009 and zero in 2013 (due to unavailability of vaccine before Hajj) [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. A large study among Egyptian pilgrims (who represent about 4% of the total pilgrims) revealed low influenza vaccination rates of between 9% and 30% in the years 2012 to 2015 [32].

However, there are limited data on influenza vaccine uptake among Saudi Hajj pilgrims. Two studies assessed vaccine uptake before 2005, reporting rates of 1% and 11% in 2003 [33], [34]. Two further studies examined the uptake in 2006 and 2009, reporting rates of 4% and 13.7%, respectively [25], [35]. Thus, the available data from studies conducted before or around the pandemic year reveal that influenza vaccine uptake among Saudi pilgrims in the past has been lower than the average of other countries. In addition, the rate has not been assessed since the pandemic, while the need for influenza vaccination for Hajj pilgrims has been discussed recently [36], [37], [38], [39]. Considering that between 26% and 45% of pilgrims in the last 10 years have been from Saudi Arabia [1], it is crucial to evaluate influenza vaccine uptake among these domestic pilgrims. Therefore, this analysis is aimed to assess influenza vaccine uptake among Saudi Hajj pilgrims over three consecutive years and to identify the key factors affecting vaccine uptake.

2. Method

Data for this study derived from a large cluster-randomised controlled trial involving Hajj pilgrims from Saudi Arabia and Australia that aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of facemasks against viral respiratory infections during Hajj. The detailed methodology has already been published elsewhere [40]. The study was conducted over three consecutive Hajj years, from 2013 to 2015. The Hajj tour group leaders, who were responsible for catering Saudi or Australian pilgrims were approached and invited to take part in the study. In the consenting groups pilgrims were met by the research team members in their tents on the first day of Hajj in respective years (October 13th in 2013, October 2nd in 2014 and September 22nd in 2015) in Mina tent city, Greater Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Only data from domestic Hajj pilgrims, who performed Hajj from Saudi Arabia, regardless of their nationalities, were included in this analysis. All participating pilgrims who gave consent were asked to complete a baseline questionnaire on the first day of Hajj. The questionnaire included participants’ demographic data such as gender, age, address and occupation; their medical histories including pre-existing medical conditions and pregnancy status; and their vaccination history including the receipt of influenza, and the reason(s) for non-receipt of the vaccine if unvaccinated.

Participants who were aged 65 years or above, and/or had pre-existing medical conditions such as chronic pulmonary, cardiovascular, neurological, hepatic or renal disease, or those who were pregnant or immunocompromised were categorised as ‘at increased risk’ pilgrims (for whom annual influenza vaccination is recommended [11], [41]). Otherwise healthy pilgrims and those younger than 65 years of age were categorised as ‘not at increased risk’.

Data were analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS® 24, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate the association of different variables on vaccine uptake. Only variables with a P value of ≤0.05 in univariable analysis were included in the multivariable model. A P value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant for this report.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained in Saudi Arabia from King Abdullah Medical City (KAMC), Institutional Review Board (IRB Ref. No.: 15-205); and in Australia from the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (HNEHREC Reference No: 13/07/17/3.04).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Saudi Hajj pilgrims

There were 6974 Saudi pilgrims recruited over the three Hajj years of 2013–2015, with a male to female ratio of 1:1.2. Age or date of birth was reported by 6785 (97.3%) pilgrims; they were aged between 18 and 95 (median 34; mean 36.4) years. Among pilgrims who declared their age and underlying medical conditions, the proportion of ‘at increased risk’ pilgrims was 1,316/6365 (20.7%). The characteristics of the participants over the three study years are listed in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Characteristics of Saudi Hajj pilgrims over the three years 2013–2015.

| Hajj Year |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total | |

| First day of Hajj | 13 October | 2 October | 22 September | – |

| Sample size | 916 | 1959 | 4099 | 6974 |

| Male:Female | 1:1.6 | 1:1.4 | 1:1 | 1:1.2 |

| Median (range) age in years | 32 (18–95) | 33 (18–95) | 35 (18–88) | 34 (18–95) |

| At increased risk | 130/730 (17.8%) | 312/1651 (18.9%) | 874/3984 (21.9%) | 1,316/6365 (20.7%) |

| Pregnant | 10/472 (2.1%) | 12/937 (1.3%) | 38/2124 (1.8%) | 60/3533 (1.7%) |

| Smoker | 56/733 (7.6%) | 147/1626 (9.0%) | 513/4034 (12.7%) | 716/6393 (11.2%) |

3.2. Influenza vaccine uptake

There were 6334 (90.8%) respondents who declared their influenza vaccination history. Over the three years, 3247 of 6334 (51.3%) participants reported receiving the influenza vaccine. Vaccination rates increased significantly from 21.4% in 2013 to 48.2% in 2014 and 58.1% in 2015 (P < 0.001).

Influenza vaccination rate was similar across the genders (50.6% in male vs 51.8% in female, P = 0.33). The uptake among 'at increased risk' pilgrims was significantly higher than among 'not at increased risk' pilgrims (54.5% vs 50.5%, P = 0.01). However, pregnant pilgrims had lower vaccination uptake compared to non-pregnant women (39.0% vs 52.0%, P = 0.05).

The participants hailed from all regions of Saudi Arabia, with a proportionate representation of the population across the regions. The vaccine uptake among pilgrims from different regions varied from 46.4% in Central region to 59.8% in Northern and Southern regions. However, it was significantly lower in pilgrims from Makkah city (28.0%) compared to pilgrims from other Saudi cities (52.2%) (P < 0.001). Healthcare workers (HCWs) comprised 8.2% of the participants, their vaccination rate was 52.7%. Influenza vaccine uptake rates in different groups of pilgrims are presented in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Influenza vaccination uptake among Saudi Hajj pilgrims, 2013–2015.

| Group | Influenza vaccination uptake n (%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hajj year | 2013 | 161 (21.4) | 1.00 (ref) | <0.001 |

| 2014 | 771 (48.2) | 3.40 (2.79–4.16) | <0.001 | |

| 2015 | 2315 (58.1) | 5.09 (4.23–6.13) | <0.001 | |

| Gender | Male | 1468 (50.6) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Female | 1779 (51.8) | 1.05 (0.95–1.16) | 0.33 | |

| Age | Less than 65 years | 3077 (51.1) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 65 years or more | 80 (55.6) | 1.20 (0.86–1.67) | 0.29 | |

| At increased risk | No | 2445 (50.5) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Yes | 692 (54.5) | 1.18 (1.04–1.33) | 0.01 | |

| Smoker | No | 2807 (51.1) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Yes | 366 (53.4) | 1.20 (0.94–1.29) | 0.26 | |

| Pregnant | No | 1762 (52.0) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Yes | 23 (39.0) | 0.59 (0.35–1.00) | 0.05 | |

| Region/city | Makkah City | 56 (28.0) | 1.00 (ref) | <0.001 |

| Northern region | 351 (59.8) | 3.83 (2.70–5.43) | <0.001 | |

| Southern region | 534 (59.8) | 3.83 (2.73–5.36) | <0.001 | |

| Western region | 910 (52.0) | 2.79 (2.02–3.85) | <0.001 | |

| Eastern region | 397 (49.8) | 2.55 (1.82–3.58) | <0.001 | |

| Central region | 699 (46.4) | 2.23 (1.61–3.08) | <0.001 | |

| Employment status | Healthcare workers | 89 (52.7) | 1.00 (ref) | 0.002 |

| Retired | 136 (64.2) | 1.61 (1.07–2.43) | 0.02 | |

| Unemployed | 237 (52.7) | 1.00 (0.70–1.43) | 0.99 | |

| Employed | 2044 (50.7) | 0.93 (0.68–1.26) | 0.62 | |

| Students | 289 (49.8) | 0.89 (0.63–1.26) | 0.52 | |

| Self employed | 37 (41.6) | 0.64 (0.38–1.07) | 0.09 | |

In multivariable logistic regression, odds ratio (OR) was adjusted for predictors with a significant P value in the univariable analysis which were: Hajj year, participants ‘at increased risk’, region, and occupation. Pilgrims who performed Hajj in 2014 and 2015 were found to have higher vaccination rate than those who performed Hajj in 2013; adjusted ORs for the respective years were 3.28 (95% CI = 2.68–4.01, P < 0.001) and 4.85 (95% CI = 4.03–5.85, P < 0.001). Pilgrims from Makkah city had lower vaccination rate than pilgrims from other regions (adjusted OR = 0.52, 95% CI = 0.37–0.72, P < 0.001).

3.3. Barriers to vaccine uptake

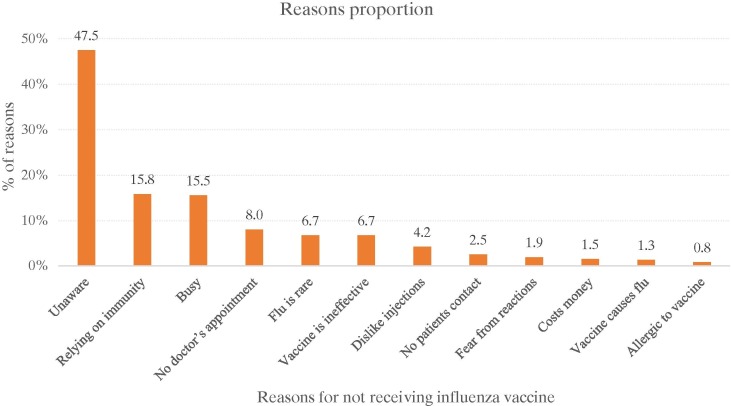

The main reasons for non-receipt of influenza vaccine were: lack of awareness (47.5%), reliance on natural immunity (15.8%) and being too busy (15.5%) (Fig. 1 ). Pilgrims from Makkah city who did not receive the vaccine were significantly more likely to state disliking for injections (9.8%) than pilgrims from other regions (3.9%) (adjusted OR = 2.94, 95% CI = 1.45–5.96, P = 0.003).

Fig. 1.

Reasons for non-receipt of influenza vaccine among unvaccinated Saudi Hajj pilgrims.

Fear of allergy to vaccine components (1.8%) was significantly more frequent reason for vaccine non-receipt among ‘at increased risk’ participants compared to the other participants (0.6%) (adjusted OR = 3.37, 95% CI = 1.38–8.26, P = 0.01). Males were significantly more likely than females to rely on natural immunity (18.1% vs 13.7%; respectively) (adjusted OR = 1.46, 95% CI = 1.14–1.87, P < 0.01) and say they were too busy to get the vaccine (17.4% vs 13.8%; respectively) (adjusted OR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.11–1.85, P = 0.01).

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to assess influenza vaccine uptake among Saudi Hajj pilgrims and to identify the key barriers to vaccine uptake. These data show that influenza vaccine uptake among Hajj pilgrims from Saudi Arabia who took part in the study has been increasing over years but is still suboptimal. The main barriers to vaccination uptake were lack of awareness and misperceptions about the vaccine.

In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) set a goal in the Fifty-Sixth World Health Assembly to achieve influenza vaccination coverage of 75% or higher by 2010 among elderly people aged 65 years or more [42]. Later, the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion at the US Department of Health and Human Services set a target of 70% for influenza vaccination coverage among the healthy population by 2020 [43], [44]. Against these international standards, a maximum influenza vaccination rate of 58.1% reported among participants in 2015, or an overall uptake of 55.6% among elderly pilgrims (aged ≥65 y) suggest there is substantial room for improvement.

As already mentioned, the influenza vaccination rate among Saudi Hajj pilgrims in this study is also lower than vaccination rates in most other countries for the corresponding years. However, the vaccination uptake was better than that of some other Arab countries. For instance, pilgrims from Egypt had a vaccination coverage of 9%, 30% and 19% during 2013-2015 respectively [32]. These findings concur with data from a recent vaccine coverage survey in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GGC) countries, showing an influenza vaccination rate of 15% to 24% [45], indicating the need for enhancing vaccination uptake among pilgrims from Arab countries.

Variation in vaccination coverage across countries and years may be partially explained by the influence of pandemics and other outbreaks on vaccination uptake. Notable non-Hajj outbreaks such as SARS in 2003-04 and avian influenza (H5N1) in 2005-06 contributed to a relative increase in influenza vaccination uptake in several settings [46], [47], [48], [49]. Similarly, the highest influenza vaccine uptake among Hajj pilgrims from different countries was observed in 2009 during the global outbreak of influenza A(H1N1)pdm 2009 strain [14], [15], [27]. This might be influenced by a heightened awareness and prolific publicity in the media, and its resultant change in policy which made the vaccine as one of the visa requirements for Hajj attendance. The surges of the MERS-CoV epidemic in Saudi Arabia in 2013 and 2014 were followed by enhanced recommendations by Saudi health authorities for influenza vaccination [50]. These policies could have played a role in the improving influenza vaccination rate among Saudi pilgrims seen in this study. However, precise data to explore the motivators of influenza vaccination in the current analysis are insufficient. Additionally, the lower number of participants in 2013 compared to the subsequent two years might have skewed the data bringing the representativeness of data into question.

Pilgrims with chronic medical conditions or those aged 65 years or above are at increased risk of severe influenza disease. Individuals with these high-risk conditions, including Hajj pilgrims before their travel, are recommended to receive seasonal influenza vaccine annually [10], [11], [41]. The current study shows that the pilgrims ‘at increased risk’ had slightly higher vaccination rate than the other pilgrims. This has also been observed in several other studies. For example, Australian pilgrims and GCC residents who were ‘at increased risk’ had higher vaccination uptake than ‘not at increased risk’ participants [19], [26], [51]. Even though vaccination uptake among ‘at increased risk’ pilgrims is relatively higher than among other pilgrims, vaccination rate has not reached the benchmark set by the WHO. Moreover, in this study, pregnant pilgrims, who are particularly encouraged to receive influenza vaccine before Hajj, had an overall vaccination uptake of just 39%. Similarly, low uptake among non-pilgrim Saudi pregnant women was attributed to misunderstanding about the safety of influenza vaccine for pregnant women [52]. Furthermore, in a hospital based study in Saudi Arabia, it was observed that only 8.8% of HCWs knew that influenza vaccine is recommended for pregnant women [53]. Thus, efforts should be inspired to promote influenza vaccination among both Saudi pilgrims and HCWs to enhance vaccine coverage among pregnant and ‘not at increased risk’.

The main reason given by Saudi pilgrims for non-receipt of influenza vaccine before Hajj was lack of awareness. This is consistent with other studies among Hajj pilgrims and the Saudi population [45], [54], [55]. Poor awareness may be due to a number of factors, including ignorance about the availability of the vaccine, who should receive it, or from where someone can receive it. All these have been previously reported by pilgrims as reasons for not receiving influenza vaccine before Hajj [54]. Hajj has taken place in recent years during autumn i.e., ahead of influenza season, that may have contributed to low level of awareness in the community regarding the need for the vaccine even though the Saudi Ministry of Health (MoH) attempt to promote the vaccine before Hajj particularly for individuals ‘at increased risk’.

Another barrier to influenza vaccination is misperception about influenza and influenza vaccine. Believing that one can rely on natural immunity was a common misperception about influenza among the Hajj pilgrims in this study. This was also the main reason for not receiving the vaccine among Australian pilgrims in 2011 and 2012 [19]. Furthermore, some pilgrims claimed that they rarely get influenza or underestimated the seriousness of influenza. Likewise, in another study, up to 14% of pilgrims who did not receive the vaccine claimed that they were not worried about getting influenza during Hajj [54]. Concerns about vaccine effectiveness or fear of vaccine side effects were stated by Saudi Hajj pilgrims as reasons for non-vaccination before Hajj. HCWs in Saudi Arabia (in non-Hajj settings) stated that they did not receive the vaccine because they believed the vaccine was not effective (51%) [53]. Other studies show that general Hajj pilgrims had similar misperceptions [45], [54], [55].

Effective health education and advice are believed to improve the attitude of Hajj pilgrims towards preventive measures including vaccination. For example, the uptake of influenza vaccine increased twice among pilgrims who received health education before Hajj compared to those who did not [55]. Overcoming the lack of awareness and misperceptions about the influenza vaccine among pilgrims, dissemination of accurate information is needed through communication channels that pilgrims use and trust. For instance, the recommendation of Hajj tour group leaders was the main positive influence on pilgrims’ attitudes towards preventive measures and vaccination among Australian pilgrims [19]. Data from a large survey on vaccination uptake among residents of GCC countries including Saudi Arabia (though not necessarily Hajj pilgrims) revealed that doctor’s advice was the leading motivator for receipt of influenza vaccine [45]. Vaccine advocacy through doctors, health authorities, and Hajj tour group leaders could enhance pilgrims’ vaccine uptake.

It is worth noting that, discussions about making influenza vaccine mandatory for Hajj pilgrims has been raised recently [36], [37], [38], [39], [56]. Apart from the apparent obstacles that challenge such policy, such as vaccine availability before Hajj and strain mismatch, other measures to prevent respiratory infections, such as pneumococcal vaccination, handwashing and facemask use, should be considered together with the influenza vaccination. Further studies are required to monitor vaccine uptake among Saudi pilgrims and advocate an optimal policy to improve vaccine uptake.

Certainly, there are some limitations in this study that can be overcome in future surveys. Firstly, the collected data on influenza vaccination were anecdotal which might introduce a recall bias. Nevertheless, while Hajj assembly in study years has occurred in September and October, most pilgrims had the influenza vaccine immediately before Hajj as the vaccine was just introduced in the Northern hemisphere, and was offered by the Saudi MoH to domestic Hajj pilgrims. Secondly, detailed data on motivators and reasons for receiving the influenza vaccine were not obtained from the study participants. Such information would enable investigators to understand pilgrims’ behaviours and enhance influenza vaccination uptake in the future. Thirdly, the study was based on a convenience sample not a probability based sample from a larger, defined population so the findings are not generalisable to the entire Saudi population.

5. Conclusion

This study indicates that influenza vaccine uptake among Saudi Hajj pilgrims who took part in the trial is increasing year by year but is still suboptimal. Lack of awareness and misperceptions about influenza and influenza vaccine are the main barriers to receive the vaccine. Education of Saudi pilgrims and health professionals is required to raise awareness of the need for vaccination and maximise uptake of influenza vaccine among pilgrims. Further studies are needed to understand pilgrims’ misperceptions about influenza vaccination so that educational strategies can appropriately address them.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The study was conducted by a National Priorities Research Program grant (NPRP 6-1505-3-358) from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation). The authors acknowledge the help and support of: The Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, Canberra; Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission, Canberra; King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah; King Abdullah Medical City, Makkah; Ministry of Health (Professor Tariq A Madani), Riyadh; Ministry of Hajj (Mr Hatim Qadi), Makkah; The Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques Institute for Hajj and Umrah Research (Professor Abdulaziz Seroji), Makkah; and volunteers in the Hajj Research Team.

Conflicts of interest

Professor Robert Booy has received funding from Baxter, CSL, GSK, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Romark and Sanofi Pasteur for the conduct of sponsored research, travel to present at conferences or consultancy work; all funding received is directed to research accounts at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead. The other authors have declared no conflict of interest in relation to this work.

References

- 1.General Authority for Statistics. Hajj Statistics 2017. https://www.stats.gov.sa/ar/28; [accessed 5 October 2017].

- 2.Memish Z.A. The Hajj: communicable and non-communicable health hazards and current guidance for pilgrims. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Ghamdi S.M., Akbar H.O., Qari Y.A., Fathaldin O.A., Al-Rashed R.S. Pattern of admission to hospitals during muslim pilgrimage (Hajj) Saudi Med J. 2003;24:1073–1076. 20030089’ [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madani T.A., Ghabrah T.M., Al-Hedaithy M.A., Alhazmi M.A., Alazraqi T.A., Albarrak A.M., et al. Causes of hospitalization of pilgrims during the Hajj period of the Islamic year 1423 (2003) Ann Saudi Med. 2006;26(5):346–351. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2006.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deris Z.Z., Hasan H., Sulaiman S.A., Wahab M.S.A., Naing N.N., Othman N.H. The prevalence of acute respiratory symptoms and role of protective measures among Malaysian Hajj pilgrims. J Travel Med. 2010;17:82–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gautret P., Benkouiten S., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish Z.A. Hajj-associated viral respiratory infections: A systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alfelali M., Rashid H. Prevalence of influenza at hajj: is it correlated with vaccine uptake? Infect Disord - Drug Targets. 2015;14:213–218. doi: 10.2174/1871526515999150320160055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benkouiten S., Charrel R., Belhouchat K., Drali T., Nougairede A., Salez N., et al. Respiratory viruses and bacteria among pilgrims during the 2013 Hajj. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1821–1827. doi: 10.3201/eid2011.140600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Memish ZA, Zumla A, Alhakeem RF, Assiri A, Turkestani A, Harby KD Al, et al. Hajj: infectious disease surveillance and control 2014;383:2073–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60381-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Algarni H., Memish Z.A., Assiri A.M. Health conditions for travellers to Saudi Arabia for the pilgrimage to Mecca (Hajj) - 2015. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2016;6:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization Weekly Epidemiological Record. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;80:425–432. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alfelali M., Barasheed O., Tashani M., Azeem M.I., El Bashir H, Memish Z.A., et al. Changes in the prevalence of influenza-like illness and influenza vaccine uptake among Hajj pilgrims: A 10-year retrospective analysis of data. Vaccine. 2015;33:2562–2569. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alqahtani A.S., Rashid H., Heywood A.E. Vaccinations against respiratory tract infections at Hajj. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moattari A., Emami A., Moghadami M., Honarvar B. Influenza viral infections among the Iranian Hajj pilgrims returning to Shiraz, Fars province Iran. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2012;6:77–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziyaeyan M., Alborzi A., Jamalidoust M., Moeini M., Pouladfar G.R., Pourabbas B., et al. Pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection among 2009 Hajj Pilgrims from Southern Iran: a real-time RT-PCR-based study. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2012;6:e80–e84. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alborzi A., Aelami M.H., Ziyaeyan M., Jamalidoust M., Moeini M., Pourabbas B., et al. Viral etiology of acute respiratory infections among Iranian Hajj pilgrims, 2006. J Travel Med. 2009;16:239–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emamian M.H., Hassani A.M., Fateh M. Respiratory tract infections and its preventive measures among Hajj pilgrims, 2010: A nested case control study. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:1030–1035. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meysamie A., Ardakani H.Z., Razavi S.M., Doroodi T. Comparison of mortality and morbidity rates among Iranian pilgrims in Hajj 2004 and 2005. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:1049–1053. 2006;27(7):447-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barasheed O., Rashid H., Heron L., Ridda I., Haworth E., Nguyen-Van-Tam J., et al. Influenza vaccination among Australian Hajj pilgrims: uptake, attitudes, and barriers. J Travel Med. 2014;21:384–390. doi: 10.1111/jtm.12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azeem M., Tashani M., Barasheed O., Heron L., Hill-Cawthorne G.A., Haworth E., et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) survey concerning antimicrobial use among Australian Hajj pilgrims. Infect Disord - Drug Targets. 2014;14:125–132. doi: 10.2174/1871526514666140713161757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hashim S., Ayub Z.N., Mohamed Z., Hasan H., Harun A., Ismail N., et al. The prevalence and preventive measures of the respiratory illness among Malaysian pilgrims in 2013 hajj season. J Travel Med. 2016;23:1–7. doi: 10.1093/jtm/tav019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koul P.A., Mir H., Saha S., Chadha M.S., Potdar V., Widdowson M.A., et al. Influenza not MERS CoV among returning Hajj and Umrah pilgrims with respiratory illness, Kashmir, north India, 2014–15. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2017;15:45–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gautret P., Gaillard C., Soula G., Delmont J., Brouqui P., Parola P. Pilgrims from Marseille, France, to Mecca: Demographics and vaccination status. J Travel Med. 2007;14:132–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rashid H., Shafi S., Booy R., El Bashir H, Ali K., Zambon M.C., et al. Influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infections in British Hajj pilgrims. Emerg Health Threats J. 2008;1:e2. doi: 10.3134/ehtj.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rashid H., Shafi S., Haworth E., El Bashir H., Memish Z.A., Sudhanva M., et al. Viral respiratory infections at the Hajj: Comparison between UK and Saudi pilgrims. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:569–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.01987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rashid H., Shafi S., Haworth E., Memish Z.A., El H., Ali K.A., et al. Influenza vaccine in Hajj pilgrims: Policy issues from field studies. Vaccine. 2008;26:4809–4812. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gautret P., Vu Hai V., Sani S., Doutchi M., Parola P., Brouqui P. Protective measures against acute respiratory symptoms in French pilgrims participating in the Hajj of 2009. J Travel Med. 2011;18:53–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gautret P., Soula G., Delmont J., Parola P., Brouqui P. Common health hazards in french pilgrims during the hajj of 2007: A prospective cohort study. J Travel Med. 2009;16:377–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gautret P., Yong W., Soula G., Gaudart J., Delmont J., Dia A., et al. Incidence of Hajj-associated febrile cough episodes among French pilgrims: A prospective cohort study on the influence of statin use and risk factors. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:335–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02816.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benkouiten S., Charrel R., Belhouchat K., Drali T., Salez N., Nougairede A., et al. Circulation of respiratory viruses among pilgrims during the 2012 Hajj pilgrimage. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:992–1000. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gautret P., Charrel R., Benkouiten S., Belhouchat K., Nougairede A., Drali T., et al. Lack of MERS coronavirus but prevalence of influenza virus in French pilgrims after 2013 Hajj. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:728–730. doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Refaey S., Amin M.M., Roguski K., Azziz-Baumgartner E., Uyeki T.M., Labib M., et al. Cross-sectional survey and surveillance for influenza viruses and MERS-CoV among Egyptian pilgrims returning from Hajj during 2012–2015. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2017;11:57–60. doi: 10.1111/irv.12429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.AlMudmeigh K., AlNaji A., AlEnezi M. Incidence of Hajj related acute respiratory infection among pilgrims from Riyadh, 1423 H (2003 G) Saudi Epidemiol Bull. 2003;10:25–26. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nooh R., Jamil A. Effect of health education advice on Saudi Hajjis, Hajj 1423 H (2003 G) Saudi Epidemiol Bull. 2004;11:11–12. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Jasser F.S., Kabbash I.A., AlMazroa M.A., Memish Z.A. Patterns of diseases and preventive measures among domestic hajjis from central. Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2012;33:879–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeitouni M.O., Al Barrak A.M., Al-Moamary M.S., Alharbi N.S., Idrees M.M., Al Shimemeri A.A., et al. The Saudi Thoracic Society guidelines for influenza vaccinations. Ann Thorac Med. 2015;10:223–230. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.167065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alfelali M., Alqahtani A.S., Barasheed O., Booy R., Rashid H. Mandating influenza vaccine for Hajj pilgrims. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:1–2. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hashem A. Influenza immunization and surveillance in Saudi Arabia. Ann Thorac Med. 2016;11:161. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.180022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stiver H.G. Influenza vaccination guidelines: A special case for Saudi Arabia. Ann Thorac Med. 2015;10:221–222. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.167063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang M., Barasheed O., Rashid H., Booy R., El Bashir H., Haworth E., et al. A cluster-randomised controlled trial to test the efficacy of facemasks in preventing respiratory viral infection among Hajj pilgrims. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2015;5:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI). The Australian immunisation handbook 10th ed (2017 update). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health; http://www.immunise.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/Handbook10-home; 2017 [accessed 5 October 2017].

- 42.WHO. Prevention and control of influenza pandemics and annual epidemics, http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/1_WHA56_19_Prevention_and_control_of_influenza_pandemics.pdf; 2003 [accessed 5 October 2017].

- 43.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP). 2020 Topics & Objectives. US Dep Heal Hum Serv 2017. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives; [accessed 20 September 2017].

- 44.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Flu vaccine coverage remains low this year. US Dep Heal Hum Serv 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p1207-flu-vaccine-coverage.html; [accessed 20 September 2017].

- 45.Alqahtani Amani S., Bondagji Daniah M., Alshehari Abdullah A., Basyouni Mada H., Alhawassi Tariq M., BinDhim Nasser F., Rashid Harunor. Vaccinations against respiratory infections in Arabian Gulf countries: barriers and motivators. World J Clin Cases. 2017;5:212–221. doi: 10.20959/wjpr2016-6447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brien S., Kwong J.C., Buckeridge D.L. The determinants of 2009 pandemic A/H1N1 influenza vaccination: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;30:1255–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holm M.V., Blank P.R., Szucs T.D. Trends in influenza vaccination coverage rates in Germany over five seasons from 2001 to 2006. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:144. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pinto C.S., Nunes B., Branco M.J., Falcão J.M. Trends in influenza vaccination coverage in Portugal from 1998 to 2010: effect of major pandemic threats. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arda B., Durusoy R., Yamazhan T., Sipahi O.R., Taşbakan M., Pullukçu H., et al. Did the pandemic have an impact on influenza vaccination attitude? a survey among health care workers. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:87. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Zumla A., Memish Z.A. Travel implications of emerging coronaviruses: SARS and MERS-CoV. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014;12:422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haridi H.K., Salman K.A., Basaif E.A., Al-Skaibi D.K. Influenza vaccine uptake, determinants, motivators, and barriers of the vaccine receipt among healthcare workers in a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. J Hosp Infect. 2017;96:268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mayet A.Y., Al-Shaikh G.K., Al-Mandeel H.M., Alsaleh N.A., Hamad A.F. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and barriers associated with the uptake of influenza vaccine among pregnant women. Saudi Pharm J. 2017;25:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rehmani R., Memon J.I. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in a Saudi hospital. Vaccine. 2010;28:4283–4287. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Memish Z.A., Assiri A.M., Hussain R., Alomar I., Stephens G. Detection of respiratory viruses among pilgrims in Saudi Arabia during the time of a declared influenza A(H1N1) pandemic. J Travel Med. 2012;19:15–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alqahtani A.S., Wiley K.E., Tashani M., Willaby H.W., Heywood A.E., BinDhim N.F., et al. Exploring barriers to and facilitators of preventive measures against infectious diseases among Australian Hajj pilgrims: Cross-sectional studies before and after Hajj. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;47:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Gautret P., Memish Z.A. Expected immunizations and health protection for Hajj and Umrah 2018 -An overview. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2017;19:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]