Abstract

One of the most fundamental challenges in developing treatments for autism-spectrum disorders is the heterogeneity of the condition. More than one hundred genetic mutations confer high risk for autism, with each individual mutation accounting for only a small fraction of autism cases1–3. Subsets of risk genes can be grouped into functionally-related pathways, most prominently synaptic proteins, translational regulation, and chromatin modifications. To possibly circumvent this genetic complexity, recent therapeutic strategies have focused on the neuropeptides oxytocin and vasopressin4–6 which regulate aspects of social behavior in mammals7. However, whether genetic risk factors might predispose to autism due to modification of oxytocinergic signaling remains largely unknown. Here, we report that an autism-associated mutation in the synaptic adhesion molecule neuroligin-3 (Nlgn3) results in impaired oxytocin signaling in dopaminergic neurons and in altered social novelty responses in mice. Surprisingly, loss of Nlgn3 is accompanied by a disruption of translation homeostasis in the ventral tegmental area. Treatment of Nlgn3KO mice with a novel, highly specific, brain-penetrant inhibitor of MAP-kinase interacting kinases resets mRNA translation and restores oxytocin and social novelty responses. Thus, this work identifies an unexpected convergence between the genetic autism risk factor Nlgn3, translational regulation, and oxytocinergic signaling. Focus on such common core plasticity elements might provide a pragmatic approach to reduce the heterogeneity of autism. Ultimately, this would allow for mechanism-based stratification of patient populations to increase the success of therapeutic interventions.

Social recognition and communication are critical elements in the establishment and maintenance of social relationships. Oxytocin and vasopressin are two evolutionarily conserved neuropeptides with important functions in the control of social behaviors, in particular pair-bonding and social recognition7,8. In humans, genetic variation of the oxytocin receptor gene (Oxtr) is linked to individual differences in social behavior9. Consequently, signaling modulators and biomarkers for the oxytocin/vasopressin system are being explored for conditions with altered social interactions such as autism spectrum disorders (ASD)5,6. In mice, mutation of the genes encoding oxytocin or its receptor results in a loss of social recognition and social reward signaling10–14. Mutation of Cntnap2, a gene linked to ASD in humans, results in reduced oxytocin levels in mice, and elevation of oxytocin rescues altered social behavior in this model15. However, the vast majority of genetic autism risk factors have no known links to oxytocinergic signaling1–3,16.

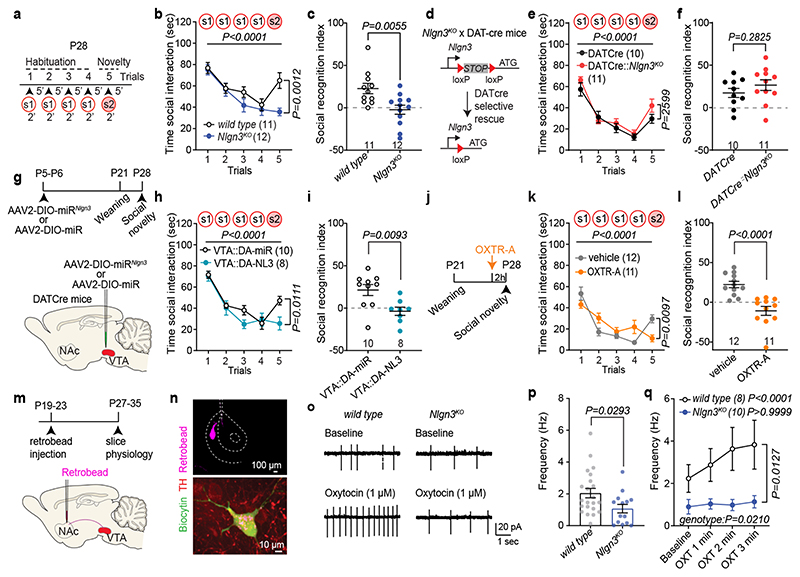

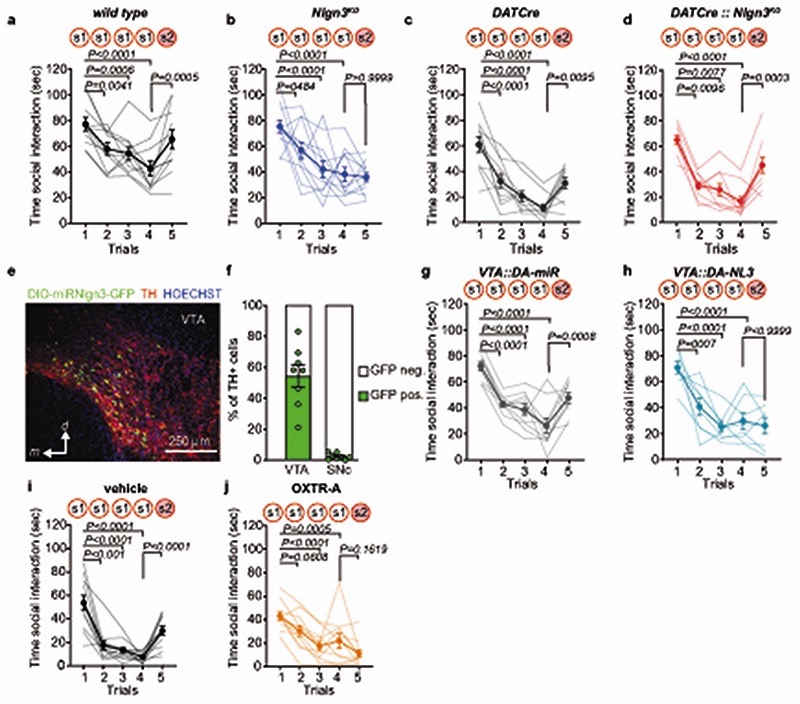

Here we explored oxytocin responses in mice which recapitulate a loss of function in the autism risk gene Nlgn3 17–19 . Nlgn3 encodes a synaptic adhesion molecule20–23 and Nlgn3 mutant mice exhibit a range of behavioral alterations, including motor stereotypies23,24, alterations in social novelty preference25–28 (but see29,30), social reward31, and social novelty responses31. Despite these alterations in social behaviors, adult Nlgn3KO mice exhibit normal responses to inanimate objects26,31. In a five-trial social habituation/recognition task we observed that the social novelty response phenotype is established already in juvenile Nlgn3KO mice (Fig.1a–c, Extended Data Fig. 1a–b, see methods for details on the task). The recognition and response to unfamiliar conspecifics depends on multiple neural circuit elements, including dopaminergic cells in the ventral tegmental area (VTA DA neurons)7,31–33. Re-expression of Nlgn3 selectively in dopaminergic cells restored social novelty responses in juvenile Nlgn3KO mice (Fig.1d–f, Extended Data Fig.1c,d). Conversely, selective inactivation of Nlgn3 in VTA DA neurons was sufficient to affect social novelty responses (Fig. 1g–i, Extended Data Fig.1 e–h). Social recognition in this assay depends on oxytocin receptor function, as treatment of wild type mice with the oxytocin receptor antagonist L-368,899 impaired recognition (Fig.1j–l, Extended Data Fig. 1.i,j).

Fig. 1. Oxytocin response is altered in VTA DA neurons lacking Nlgn3.

a, 5-trial social habituation/recognition task. s1=first, s2=second social stimulus. b,c, Mean social interaction time (b) and social recognition index (c) in wild type and Nlgn3KO mice. Numbers on graphs represent mice. d, Nlgn3KO mutation containing a loxP-flanked transcriptional stop cassette. In DATCre mice Nlgn3 is selectively re-expressed in dopaminergic neurons. e,f, Mean social interaction time (e) and social recognition index (f) in DATCre and DATCre::Nlgn3KO mice. g, VTA AAV-injection in DAT-Cre mice for microRNA-mediated knockdown of Nlgn3 in VTA-DA neurons (VTA::DA-NL3). h,i, Mean social interaction (h) and social recognition index (i) for VTA::DA-NL3 or control (VTA::DA-miR) mice. j, Oxytocin receptor antagonist treatment (OXTR-A, L-368,899 10 mg/kg i.p. in saline). k,l Mean social interaction (k) and social recognition index (l) for OXTR-A and vehicle treated mice. m, Retrobeads were injected in the NAc medial shell and tissues prepared for slice physiology. n, Retrobead injection site in the NAc (top) and TH immunoreactivity and retrobead labeling in biocytin-filled VTA neurons (bottom) after recording. o, Example traces of spontaneous firing at baseline (top) and after bath application of 1 μM OXT (bottom) in VTA DA neurons from wild type (left) and Nlgn3 KO (right). p, Frequency at baseline in TH-positive wild type and Nlgn3 KO VTA DA neurons. n: wild type=22 cells from 12 animals; Nlgn3 KO=14 neurons from 8 animals. q, Average firing frequency (Hz) after bath application with OXT in retrobead-labeled TH-positive cells in VTA of wild type and Nlgn3KO mice. P-value on graph: Within group comparison of baseline vs. OXT 3rd min. n: wild type= 8 cells from 7 animals; Nlgn3 KO=10 neurons from 7 animals. Error bars are s.e.m. RM two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for b, e, h, k, q; unpaired two-sided t-test for c, f, i, p; two-sided Mann-Whitney test for l. Additional statistics in Supplementary Information.

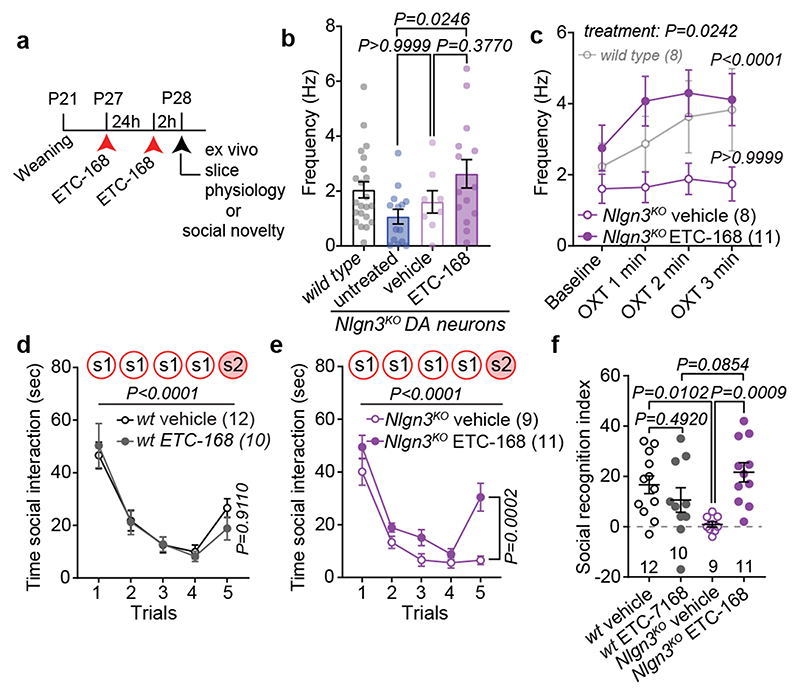

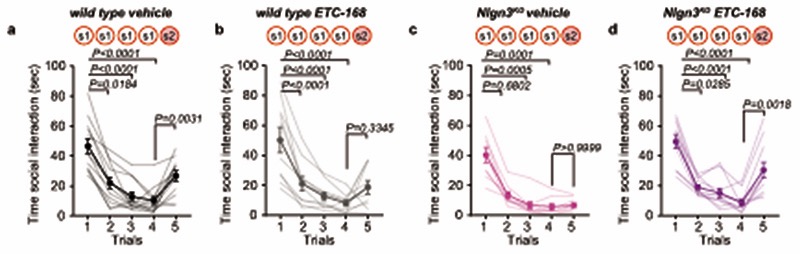

Fig. 4. MNK inhibition restores social novelty responses in Nlgn3 KO mice.

a, Scheme for drug treatment and analysis. b, Firing frequency at baseline in VTA DA neurons from Nlgn3 KO animals untreated, treated with vehicle, or 5 mg/kg ETC-168. n: untreated=14 neurons from 8 mice; vehicle=8 neurons from 4 mice; ETC-168=14 neurons from 8 mice. The wild type mouse data from Fig. 1c is presented for comparison (n=22). c, OXT-induced frequency changes over time in VTA DA neurons from Nlgn3 KO animals treated with vehicle or 5 mg/kg ETC-168. Wild type mice from Fig. 1e are presented for comparison. P-values on graph: Baseline vs. OXT 3rd min. n: vehicle treated=8 cells from 4 mice; ETC-168 treated=11 neurons from 6 mice. d, e, Mean social interaction time in (d) wild type and (e) Nlgn3KO mice treated with vehicle or 5 mg/kg ETC-168. f, Social recognition index for wild type and Nlgn3KO mice treated with vehicle or 5 mg/kg ETC-168. Numbers in brackets indicate mice. All error bars are s.e.m. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for b; RM two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for c; RM two-way ANOVA between all genotype and treatment groups followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for d, e; RM two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for treatment and genotype for f. Additional statistics Supplementary Information.

The function of VTA DA neurons in social novelty responses and reinforcement is in part dependent on an oxytocin-induced elevation of neuronal firing. Specifically, oxytocin released from axons that arise from hypothalamic nuclei increases the firing of VTA DA neurons projecting to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) 12,13. Thus, we examined whether loss of Nlgn3 might impact the response of this population of neurons to oxytocin. We marked VTA DA neurons projecting to the NAc medial shell and performed electrophysiological recordings from back-labeled neurons in acute slices of the VTA (Fig. 1m,n). Consistent with previous reports, back-labeled neurons showed low Ih currents, and there was no significant difference between genotypes in Ih and other basic biophysical properties (Extended Data Fig. 2). In cell attached recordings, baseline firing frequency of VTA DA neurons from Nlgn3KO mice was slightly reduced as compared to wild type mice (Fig. 1p). Notably, bath application of 1 μM oxytocin significantly increased firing frequency in cells from wild type but had no effect in Nlgn3KO slices (Fig. 1o,q). These findings uncover a requirement for the autism risk factor Nlgn3 for oxytocin responses in the VTA.

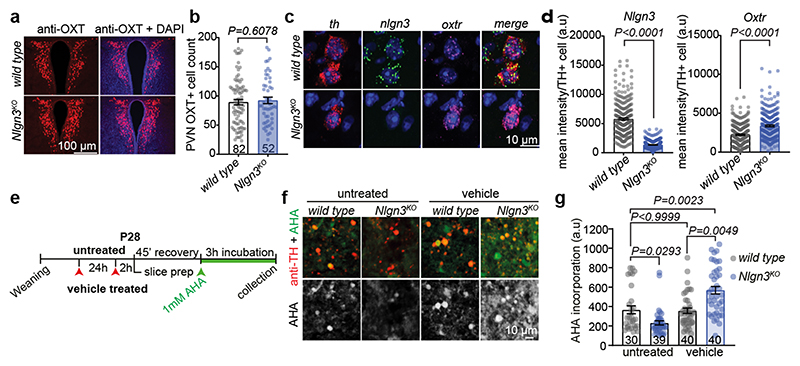

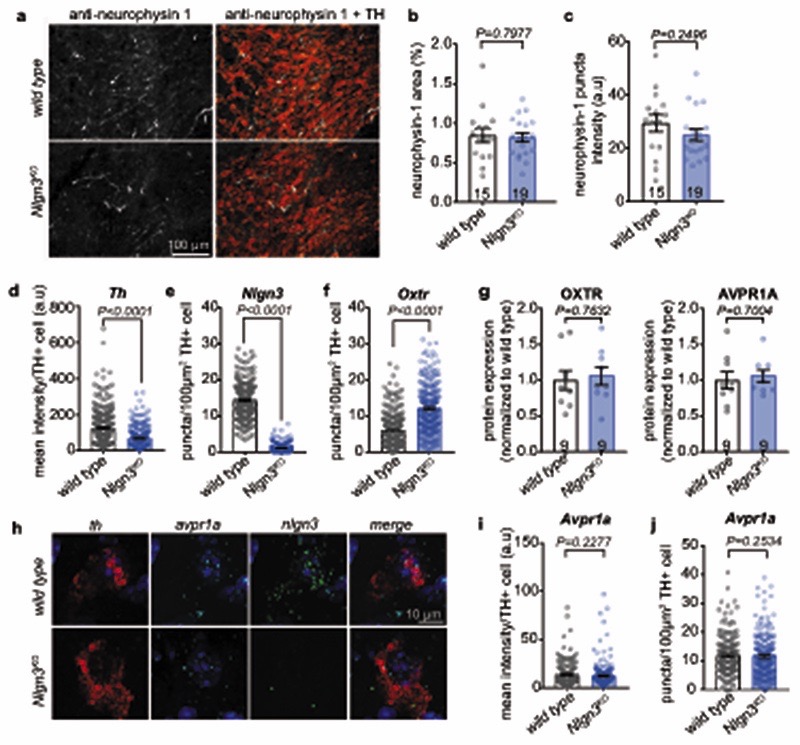

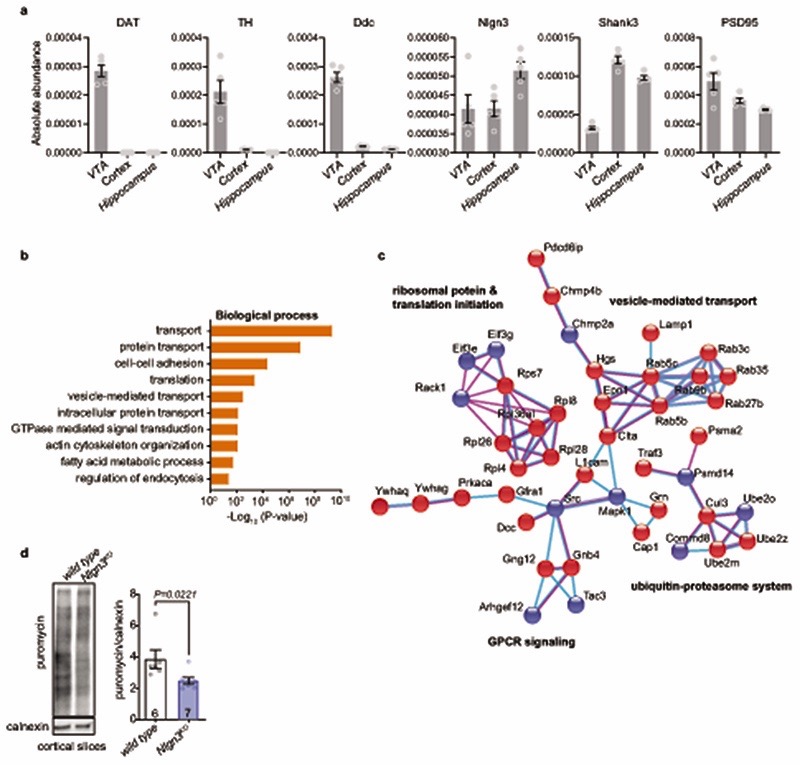

A loss of oxytocinergic neurons has been reported in knock-out mice for the autism risk factors Cntnap2 and Shank3b 14,15. In Nlgn3KO mice we did not detect any alteration in the density of oxytocinergic neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (one of the major oxytocinergic nuclei) or in the density of oxytocinergic fibers in the VTA (Fig. 2a,b, Extended Data Fig. 3a–c). Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) revealed a slight increase in Oxtr mRNA in VTA DA neurons from Nlgn3KO mice compared to wild type animals (Fig. 2c–d, Extended Data Fig. 3d–f). However, targeted proteomics (parallel reaction monitoring) on microdissected VTA tissue did not detect significant alterations in total oxytocin receptor protein (Extended Data Fig. 3g, vasopressin 1a receptor mRNA and protein were unaltered, Extended Data Fig. 3 g–j and Table S1). Thus, we performed shot-gun proteomics for an unbiased identification of molecular alterations in the VTA of Nlgn3KO mice (Extended data Fig.4a–c, Table S2). Gene ontology (GO) and network-based functional classification analysis for proteins altered in Nlgn3KO VTA identified protein transport, cell adhesion, and mRNA translation as main categories (Extended Data Fig.4b,c). Dysregulation of membrane trafficking and GPCR signaling components is consistent with the previously discovered roles for Nlgn3 in synapse organization and GPCR signaling22,23,34. However, the alterations in regulators of translation were surprising. Alterations in mRNA translation have been linked to neuronal plasticity deficits. We previously observed that behaviorally-induced plasticity is altered in VTA DA neurons of Nlgn3KO mice31. Thus, we compared translation in VTA DA neurons of naïve and behaviorally exposed wild type and Nlgn3KO mice. Incorporation of the methionine analogue azidohomoalanine (AHA)35 in VTA DA neurons (marked by tyrosine hydroxylase) of acute mouse brain slices from naive Nlgn3KO mice was reduced as compared to wild type (Fig. 2e–g. and see Extended Data Fig. 4d for data from cortical slice preparations). Interestingly, AHA incorporation was elevated in VTA DA neurons from Nlgn3KO mice exposed to handling (Fig.2e–g). This suggests a signaling-dependent disruption of translation homeostasis in the mutant mice.

Fig. 2. Disruption of translational regulation in VTA of Nlgn3KO mice.

a, Representative image of OXT (red) and DAPI (blue) immunofluorescence in the PVN of wild type and Nlgn3KO mice. b, Mean OXT positive cells per section in the PVN in wild type and Nlgn3KO mice. n= 3 mice per genotype, numbers on bar indicate sections analyzed. c, Representative fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) images in the VTA from wild type (top) and Nlgn3KO (bottom) using probes for th (red), nlgn3 (green) and oxtr (magenta). d, Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity per th+ cell from wild type and Nlgn3 KO VTA for nlgn3 (left) and oxtr (right). n: wild type= 280 cells from 4 animals; Nlgn3 KO=265 cells from 3 animals. e, Scheme for AHA incorporation on slice preparations from untreated and vehicle treated mice. f, Representative images of acute slice measurements of protein synthesis in VTA visualized by AHA incorporation (green) with marking of TH-positive cells (red). g, quantitative assessment of AHA incorporation in naïve mice versus mice treated by oral gavage with vehicle. n: wild type untreated= 3 animals; Nlgn3KO untreated, Nlgn3KO vehicle and wild type vehicle = 4 animals. Numbers on graph refer to the number of images analyzed (8-20 VTA DA cells per image, approximately 10 images per animal). All error bars are s.e.m. Two-sided Mann-Whitney test for b, d; Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test for g. See Supplementary information for additional statistics.

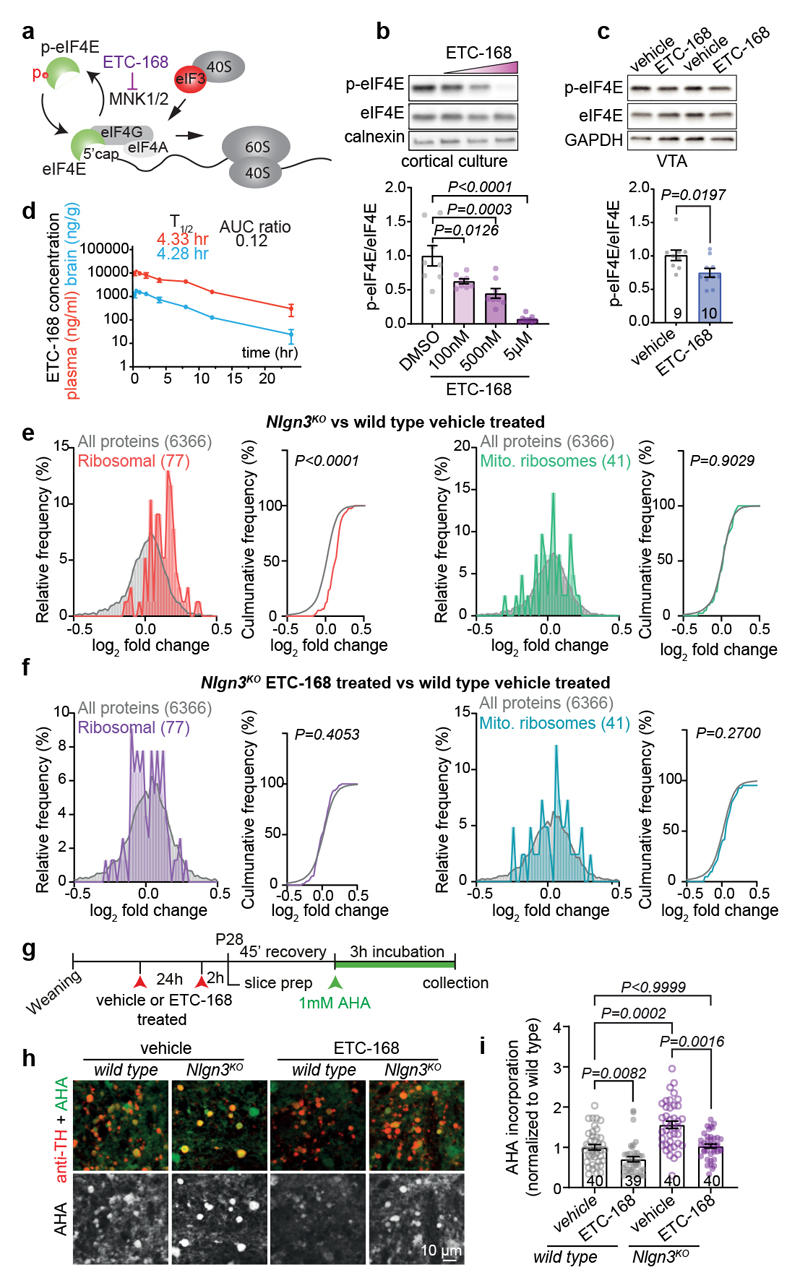

Disruption of translation homeostasis is thought to broadly modify neuronal proteins resulting in impaired plasticity and neurodevelopmental conditions36–40. Thus, we sought to normalize translation in Nlgn3KO mice and to test whether this would restore oxytocin responses in VTA DA neurons. We focused on MAP-kinase interacting kinases (MNKs) which are critical regulators of signaling-dependent modification of mRNA translation (Fig. 3a). MNK inhibition was reported to modify ribosomal protein levels and to ameliorate behavioral and plasticity alterations in Fmr1 knock-out mice (Fmr1KO)41–43. We tested efficacy and brain penetrance of a novel series of highly specific MNK inhibitors originally developed for oncology applications44. One of these compounds, ETC-168 resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in phosphorylation of the MNK target eIF4E in cultured cortical mouse neurons without affecting eIF4E, eIF4G protein levels or ERK1/2 activity (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 5a–e). In wild type mice, orally administered ETC-168 had significant brain penetration (brain to plasma ratio 0.12) with a half-life of 4.3 hrs (Fig. 3d), and resulted in a reduction in eIF4E phosphorylation in the VTA and other brain areas (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Fig. 5f and l). Of note, phospho- or protein levels of Eif4E or MNK1 are unaltered in the VTA of Nlgn3KO mice (Extended Data Fig. 5g–k). As a proof of concept, we probed the effectiveness of ETC-168 treatment in modifying a behavioral phenotype in Fmr1KO mice. In a place-independent discrimination task, Fmr1KO and wild type mice learned a cue-reward contingency rule equally well, but Fmr1KO mice were impaired upon contingency reversal (Extended Data Fig. 6a, b). ETC-168 treatment during the reversal phase of the task significantly improved their performance (Extended Data Fig. 6c, d). Thus, ETC-168 is a novel, highly selective, brain-penetrant inhibitor of MNK1/2 activity, which modifies cognitive behavior in mice.

Fig. 3. The novel MNK1/2 inhibitor ETC-168 rescues translation in Nlgn3KO VTA.

a, ETC-168 targets MNK1/2. Note that eIF4E phosphorylation decreases affinity of eIF4E for the mRNA 5’cap structure b, eIF4E phosphorylation in day in vitro 14 cortical neurons treated with ETC-168 for 3 hours. n=8 replicates, 3 independent experiments. c, Representative western blot and quantification of VTA lysate from wild type mice treated with vehicle or 5 mg/kg ETC-168. Numbers on graphs represent mice. d, Pharmacokinetic analysis of ETC-168 in male mice (n=27) after single oral dose of 10 mg/kg. Plasma levels in red, brain levels in blue. Half life (T1/2), maximal concentration (Cmax), and brain to plasma exposure (AUCratio) are displayed on the graph. e, Tandem mass tag (TMT) proteomic comparison of VTA from vehicle-treated mice (n=4 mice per genotype and treatment). Relative frequency of log2 fold change in either all detected proteins, cytosolic, or mitochondrial ribosomal protein abundance is plotted (Nlgn3KO/wild type). f, Comparison as in e for log2 fold change in protein abundance in ETC-168 treated Nlgn3KO versus wild type. g, FUNCAT assay in acute slices from vehicle or ETC-168 treated mice (5mg/kg or vehicle by oral gavage). h, Representative examples of AHA incorporation (green) in TH-positive cells (red). i, Quantitative assessment of AHA incorporation in vehicle (as in Fig. 2h for comparison to untreated mice) versus ETC-168 treated wild type and Nlgn3KO mice. n=4 mice per genotype and treatment. Numbers on graphs refer are number of images analyzed. Error bars are s.e.m. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for b; two-sided unpaired t-test for c; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for e, f; Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test for i. Additional statistics in Supplementary Information.

We then asked whether ETC-168 treatment would modify the translational machinery in the VTA of Nlgn3KO mice. Using tandem mass tag (TMT)-based isobaric labeling we verified the de-regulation of translational machinery in VTA tissue from vehicle-treated Nlgn3KO versus vehicle treated wild type mice (Extended Data Fig. 7a–d). Gene set enrichment analysis45 uncovered an elevation in core proteins of cytoplasmic but not mitochondrial ribosomes (Fig. 3e, Extended Data Fig. 7e, g). MNK-inhibition with ETC-168 abolished the increase in core ribosomal proteins in Nlgn3KO VTA (Fig.3f, Extended Data Fig.7f, h). In acute slices from ETC-168-treated Nlgn3KO mice, AHA incorporation was significantly reduced as compared to vehicle treated Nlgn3KO mice, resulting in AHA incorporation levels similar to slices from vehicle treated wild-type mice (Fig.3g–i).

We then tested whether ETC-168 treatment restored oxytocin responses and social novelty responses in Nlgn3KO mice (Fig. 4a). Notably, short-term oral treatment (2 applications of 5mg/kg ETC-168 over 26 hrs) of Nlgn3KO mice recovered the oxytocin-induced elevation of firing frequency seen in wild type mice (Fig. 4b, c). This treatment also fully restored social novelty responses, with no detectable effect on wild type mice (Fig. 4a, d–f, Extended Data Fig. 8). This pharmacologically recovered social recognition behavior was dependent on oxytocin receptor function (Extended Data Fig. 9). Importantly, ETC-168 treatment was well tolerated and remained effective in a long-term treatment regime (Extended Data Fig. 7a–c, and Extended Data Fig. 10). Thus, modification of translation homeostasis in Nlgn3KO mice by MNK inhibition restores oxytocin responses and social novelty responses.

This work uncovers an unexpected convergence between the genetic autism risk factor Nlgn3, translational regulation, oxytocinergic signaling, and social novelty responses. While loss of Nlgn3 impairs oxytocin responses in VTA DA neurons, the behavioral phenotype does not fully phenocopy genetic loss of oxytocin. Oxytocin KO mice exhibit impaired habituation in the social recognition task10 whereas Nlgn3KO mice habituate normally but exhibit a selective deficit in the response to a novel conspecific. This is likely due to differential roles of Nlgn3 and oxytocin across multiple neural circuits and over development. Moreover, Nlgn3 loss-of-function also impacts signaling through additional G-protein coupled receptors23.

We propose that pharmacological inhibition of MNKs may provide a novel therapeutic strategy for neurodevelopmental conditions with altered translation homeostasis. Importantly, MNK loss-of-function appears to be overall well tolerated. MNK1/2 double-knock-out mice are viable46 and several novel MNK inhibitors are entering clinical trials for cancer therapy47. Previously available MNK-inhibitors were greatly limited by specificity and brain penetrance. Our work not only highlights a new class of highly-specific, brain-penetrant MNK inhibitors but also expands their application from Fragile X41 to a non-syndromic model of ASD. The common disruption in translational machinery and phenotypic rescue in two very different genetic models highlights that genetic heterogeneity of ASD might be reduced to a smaller number of cellular core processes. This raises the possibility that pharmacological interventions targeting such core processes may benefit broader subsets of patient populations.

Methods

Mice

Male wild type, Nlgn3KO 19 and Fmr1KO mice48 were used for this study. Note that this strain of Nlgn3KO mice contains a transcriptional stop cassette19 preventing genetic compensation events that might be triggered in mutants expressing truncated mRNAs49. For dopamine neuron-specific manipulations DAT-Cre BAC transgenic mice were employed50. Mice were kept on a C57BL/6j background. All animals were group housed (weaning at P21 – P23) under a 12h light – dark cycle (6:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m.) with food and water ad libitum. All physiology and behavior experiments were performed during the light cycle. Embryos for cortical cultures were obtained from NMRI mice (Janvier). All the procedures performed at University of Lausanne and Biozentrum complied with the Swiss National Institutional Guidelines on Animal Experimentation and were approved by the respective Swiss Cantonal Veterinary Office Committees for Animal Experimentation.

Pharmacokinetics of ETC-168

A group of twenty-seven male C57BL/6 mice were administered with ETC-168 solution formulation in 7.5% NMP, 5% Solutol HS, 10% PG, 30% PEG-400, 47.5% Normal Saline at a dose of 10 mg/kg. Blood samples (approximately 60μl) were collected under light isoflurane anesthesia from retro orbital plexus at PD, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 hr. Plasma samples were separated by centrifugation of whole blood and stored below −70°C until analysis. Immediately after collection of blood, brain samples were collected from each mouse at PD, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 hr. Brain samples were homogenized using ice-cold phosphate buffer saline (pH 7.4) and homogenates were stored below −70°C until analysis. Total homogenate volume was three times the tissue weight. All samples were processed for analysis by protein precipitation using acetonitrile and analyzed with fit-for-purpose LC/MS/MS method (LLOQ – 2.00 ng/mL in plasma and 1.00 ng/mL in brain). Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using the non-compartmental analysis tool of Phoenix WinNonlin® (Version 6.3).

Pharmacological treatment

For in vitro experiments, ETC-168 was dissolved in DMSO. For in vivo treatment, ETC-168 was dissolved in 0.5% Methylcellulose (Sigma, M7140) and 0.1% Tween-80 (Sigma, P5188) in MilliQ water to 1.25 mg/ml, and sonicated for 30 min. Animals were gavaged 24h and 2h before behavioral assessment or tissue collection for acute treatment. In the chronic treatment regime, animals were treated every 24 h and two hours before start of the evaluation. The OXTR antagonist L-368,899 (Tocris, #2641) was dissolved in saline and 10 mg/kg was applied via i.p. injection 2h before the start of behavioural assessments, or 15 min before the final dose of ETC-168.

Stereotaxic injection

Injections of diluted (1:4) Red Retrobead™ were done at P19-P23 and performed under isoflurane anesthesia (Baxter AG, Vienna, Austria). The animals were placed in a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instrument) and a single craniotomy was made over the NAc medial shell at the following stereotaxic coordinates: ML 0.55 mm, AP 1.5 mm, DV −4.05 mm from bregma. Injections were made with a 30-G Hamilton needle (Hamilton, 7762-03) for a total volume of 300 nL. Injection sites were confirmed post-hoc by immunostaining. For electrophysiological experiments, the animals were left 5-8 days after injection before the start of experiment.

For Nlgn3 conditional knock-down experiments, injections of purified AAV2-DIO-miRNlgn3-GFP and AAV2-DIO-miR-GFP were performed as described previously31. Briefly, DAT-cre transgenic mice were injected at postnatal day 5 – 6 and a single craniotomy was made over the VTA at following stereotaxic coordinates: ML +0.15 mm, AP +0.2 mm, DV −4.2 mm from lambda for P5-P6. Injections were made with a 33-G Hamilton needle (Hamilton, 65460-02) for a total volume of 200 nL. Behavioral testing was performed at postnatal day 28 and injections sites were confirmed post-hoc by immunostaining as described previously31. Briefly, VTA::DANL3KD mice were included if a minimum of 20% of TH-positive cells in the VTA were GFP-positive. Mice were excluded from the analysis if their body weight was less than 75% of the body weight at the start of behavioral trials or in case post-hoc analysis revealed inefficient or off-target viral infection.

Habituation/novelty recognition task

Social recognition is considered to be commonly affected in individuals on the autism spectrum. Autistic individuals perform poorly on face identity recognition tasks, especially when a medium to high time delay (seconds to several minutes) between face presentation is applied51,52. To model social recognition in juvenile male mice we adopted previous protocols that had been developed for adult rodents10,53. In this test, recognition between juvenile male mice (postnatal day 26 – 32) was tested with 5 minute inter-trial intervals that mimic the timescales of recognition tasks from patient studies. An experimental cage similar to the animal’s home cage was used with grid, food, and water removed. The experimental animals were acclimated in the cage for 30 min before the start of the test. At the start of the first trial, a novel same-sex mouse (stimulus mouse: C57BL/6J juvenile male mice, P21-P28) or an object (Lego block) was introduced into the cage for 2 min and mice were left to freely interact. This was repeated for 4 consecutive trials with 5 min in-between trial intervals to allow habituation to the stimulus mouse or object. On the 5th trial, a novel mouse (littermate to the stimulus mouse) or a novel object (dice) was introduced. For the social stimulus, interaction was scored when the experimental mouse initiated the action and when the nose of the animal was oriented toward the social stimulus mouse only. For the object stimulus, interaction was scored when nose of the mouse was oriented 1 cm or less towards the object. The interaction time was used to calculate the recognition index as: (Interaction trial 5) - (Interaction trial 4). Social recognition in rodents has been reported to depend on oxytocin signaling11,54. To pharmacologically validate the recognition task, we treated mice with the oxytocin receptor antagonist (L-368,899 10 mg/kg injected intraperitoneally 2 hrs before testing). This treatment significantly suppressed recognition of novel conspecifics in this task (see Fig.1k,l).

Place-independent cue discrimination and reversal task

Adult male mice were used for this test. The test box (25 × 35 cm) was divided in a waiting and a reward zone by a gated plexiglass wall. Reward (condensed milk) was associated to one of the two lining patterns of a double tray (white tape vs brown sandpaper). The tray was turned in a pseudorandom fashion between trials in order to present the rewarded pattern on the right and the left 8 times within a daily session of 16 trials. Sliding lids were used to prevent nosepoke in the correct target after the mouse made a wrong choice, and to signal end of a trial and return to the waiting zone after the bait has been consumed. Before the start of the trial, mice were food deprived overnight and the reward was presented in the home cage to habituate to the reward. For the duration of the test, mice were food restricted overnight and receive food ad libitum after completion of the discrimination task. After the first night of food deprivation, mice were brought to the testing arena where they find condensed milk droplets (15 μl) in falcon lids similar to those used for the test. First day of habituation takes place in groups of cage mates, second day in individual session. Mice were shaped to shuttle to the waiting compartment of the arena after having consumed the reward. On day 1, mice were trained to find the reward only in one of two adjacent falcon lids that have been lined and mounted on little stages with a different pattern (brown sandpaper vs white tape). Each mouse undergoes 16 daily trials, with a cutoff of 20 minutes. Mice not completing 16 trials by the third testing day were excluded from further testing. Mice not attaining learning criterion for the first contingency (8 consecutive correct responses over two days), after 6 days of training did not go to the reversal learning step (nor received any treatment). Mice were trained for 6 consecutive days/week. Feeding was restricted to 1 g/mouse overnight. On day 7 (day 1 of reversal learning training), mice received ETC-168 5 mg/kg or vehicle by gavage 120 min before starting the tests for the duration of the reversal task. For the contingency reversal learning, mice were trained to nosepoke in the previously non-baited pattern in order to find reward. The training schedule was the same as before: 16 trials / day, until attainment of learning criterion (second day when 8 consecutive correct responses have been performed).

Open field and marble burying

Male mice were placed individually in the center of a square open field arena (50 × 50 × 30 cm) made of grey plastic for 7 minutes. Velocity (cm/sec) was analyzed using EthoVision10 system (Noldus). The arena was cleaned with 70% ethanol between trials. For the marble burying test, animals were placed in a standard Type II cage with 5 cm bedding containing 20 identical black marbles distributed equally for 30 minutes. A marble was considered buried if at least 2/3 of the marble was covered.

Electrophysiology

Male mice (P28-P34) were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane (4% in O2, Vapor, Draeger) prior decapitation and brain isolation. Acute horizontal brain slices (250 μm thick) from the midbrain were cut with a vibrating microslicer (Leica VT1200S) in ice-cold oxygenated sucrose-based cutting solution containing: NaCl (87 mM), NaHCO3 (25 mM), KCl (2.5 mM), NaH2PO4 (1.25 mM) sucrose (75 mM), CaCl2 (0.5), MgCl2 (7mM) and glucose (10 mM) (equilibrated with 95% O2/ 5% CO2). Slices were immediately transferred to a storage chamber containing artificial cerebral spinal fluid (ACSF) containing: NaCl (125 mM), NaHCO3 (25 mM), KCl (2.5 mM), NaH2PO4 (1.25 mM), MgCl2 (2 mM), CaCl2 (2.5 mM) and glucose (11 mM), pH 7.4, constantly bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2; 315-320 mOsm. Slices were maintained at 35°C in ACSF for 60 min and then kept at room temperature before their transfer to the recording chamber. During the recordings, the slices were continuously perfused with ACSF at 35.0 ± 2.0°C throughout the experiments. Neurons were visualized with a LNScope (Luigs & Neumann, Germany) equipped with an oblique illumination condenser, a 60× objective (LUMPplanFI, NA 0.9) and a reflected illuminator (Olympus). Slices were illuminated with a collimated LED infrared light source (Thorlabs) and wLS LED illumination unit (Q-imaging). The recorded neurons in the VTA were identified by their anatomical localization and recorded if they were labeled with red retrobeads (or by morphology for recording from non-retrobead labelled cells). Their dopaminergic identity was subsequently confirmed by immunohistochemistry. Neuronal activity was recorded at the somata with borosilicate glass pipettes (4-6 MΩ) filled with an intracellular solution containing: K-gluconate (125 mM), KCl (20 mM), HEPES (10 mM), EGTA (10 mM), MgCl2 (2 mM), Na2ATP (2 mM), Na2-phosphocreatine (1 mM), Na3GTP (0.3 mM), 0.2% biocytin, pH 7.2 (with KOH); 312.3 mOsm. Electrophysiological recordings were obtained using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier and digitized at 10 kHz. Recording of spontaneous firing activity in VTA in dopaminergic neurons was achieved in voltage clamp cell-attached configuration after formation of a gigaseal.

Baseline activity was recorded during 2 or 3 minutes (sweeps of 5 second duration were acquired every 10 seconds) before Oxytocin (1 μM; TOCRIS, # 1910) applied to the perfusion reached the recording chamber. Recordings in the presence of Oxytocin were continued for 3 minutes. At the end of these recordings, a whole-cell configuration in voltage clamp (holding potential: −55 mV) was achieved by disruption of the gigaseal with gentle negative pressure applied through the recording pipette. A period of 5 minutes was then allowed for loading the neurons with biocytin. Finally, the recording pipette was carefully removed and the slice transferred to paraformaldehyde (4 % in PBS) for subsequent anatomical analysis. All TH+ cells, including cells negative for retrobeads, were used to analyze frequency. Only TH+ and retrobead positive cells recorded for a minimum of 3 min after OXT application were used to analyze OXT response, and all data points represent an average per minute.

Ih recordings were performed in whole-cell voltage-clamp configuration after compensating the pipette capacitance and the series resistance (Rs) (15-20 MΩ; 40-50%, bandwidth 3.5 kHz). Rs was monitored on-line and the experiments were discarded if the Rs changed >20%.

Neuronal input resistances (Ri) and membrane capacitances were evaluated for each neuron by injecting a voltage command of −5 mV for 200 ms duration, from a holding potential (HP) of −50 mV. The electrical capacitance of the neurons was determined by fitting a bi-exponential function to the capacitive current at the beginning of a −50 mV pulse from a holding potential of −55 mV (pipette capaciantce was previously compensated during the cell-attached configuration prior whole-cell formation). The amplitude-weighted time constant (□vc) and measured current peak (Ipeak) amplitude was inserted into the following formula to calculate the electrical capacitance.

Weighted t_vc was calculated from the the bi-exponential fitting as:

Ih was evoked by injecting a series of 1.5 sec duration hyperpolarizing voltage commands (Vcomm) from a HP of −50 mV to −130 mV, in consecutive steps of 10 mV. Ih-tail currents were evoked at 130 mV at the end of each Vcomm before returning the HP to −50 mV. Ih-tail voltage dependency was calculated by plotting their normalized amplitudes. Maximal Ih-tail currents (Imax) as defined as recorded after the Vcomm to −130 mV, was set to 1; Minimal Ih-tail currents (Imin) as recorded after the HP of −50 mV, was set to 0. A Boltzmann function was fitted: I = Imin + (Imax − Imin) / 1 + exp [(V50 − Vcomm)/s]; where V50 is the half-activation potential and s is the slope factor. After recording the Ih, each cell was switched to current clamp mode to record the resting membrane potential. The experimenter was blinded to the genotype and treatment condition.

Analysis of mRNA translation

Translational in the VTA was analyzed using FUNCAT55,56, where AHA is incorporated into cells and then detected using an alkyne tagged to Alexa 488. Mice were anesthetized at P28 and 250 μm thick coronal slices were cut on a vibratome and placed in ACSF for 45 min at 35°C to recover. The same cutting solution and ACSF as described for electrophysiology was used. Slices were moved to an incubation chamber and incubated for an additional 3h with 1mM AHA (Jena Bioscience, CLK-AA005). At the end of incubation, slices were transferred to ice-cold 4% PFA and left overnight at 4°C. Next day, slices were incubated for 1.5h in a blocking solution containing 5% BSA (Sigma), 5% normal donkey serum and 0.3% Trition X-100 in 1× PBS at agitation at RT. Slices were then washed 3× 5 min followed by incubation over night with gentle agitation with 500 μl Click-iT reaction cocktail according to the manual instructions (Click-iT Cell Reaction Buffer Kit, Invirogen, C10269). Slices were then washed 3× 10 min with 1xPBS followed by incubation with anti-TH (Millipor, AB1542, 1:1000) primary antibody at RT for 2h, washed three times in 1× PBS, followed by incubation for 2h at room temperature with a secondary antibody. The sections were then washed three times in 1× PBS before mounted onto microscope slides with ProLong Gold antifade (Invitrogen, p36930). Images were taken on an Olympus SpinSR spinning disk with a UPL S APO 30× objective (NA 1.5). All images were taken with the same laser power, gain and exposure settings, and analyzed using ImageJ. For analysis of AHA incorporation, 10 images were taken of the VTA and the Alexa-488 mean fluorescent intensity of 9-20 regions of interest (ROI) corresponding to TH+ somas were measured. The mean fluorescent intensity of cells per image was used for analysis, and the experimenter was blinded to genotype and treatment. All images within each experiment were processed in parallel using identical settings in ImageJ (NIH) and Adobe Photoshop CS 8.0 (Adobe systems).

For puromycin incorporation, 400 μm thick coronal slices were cut on a vibratome and placed in ACSF (in mM: 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 20 Glucose, 26 NaHCO3, 95% O2/5% CO2) for 30 min at RT followed by 2h at 32°C. 5 μg/ul puromycin (Sigma) was added for 45 min to label newly synthesized proteins. Sections were snap frozen and subsequently lysed in 10mM Hepes, 1% SDS, 1mM NaF, 1mM NaVO4 containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science), sonicated and incubated for 10min at 95°C. Puromycin incorporation was measured by western blot (see ‘Western blot’ for detailed methods) using mouse anti-puromycin antibody (EQ0001, Kerafast). The results were normalized to signal obtained with anti-calnexin antibodies run at the same time on a different blot.

Western blot and AlphaLISA immunoassay

Cortical neurons and brain tissue were homogenized in lysis buffer containing NaCl 137 mM, KCl, 2.7 mM, Na2HPO4 10 mM, KH2PO4, 1.8 mM, EDTA 5 mM, Triton 1%, and complete protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). Immunoblotting was done with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate. The following primary antibody was used in this study: p-eIF4E (Abcam, ab76256 1:1000), eIF4E (Abcam, ab47482 1:1000), p-ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling, 4370S 1:1000), ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling, 4695S 1:1000), p-eIF4G (Cell Signaling, 2441S 1:1000), eIF4G (Cell Signaling, 2498 1:1000), p-MNK1 (Cell Signaling, 2111, 1:1000), MNK1 (Cell Signaling, 2195S, 1:1000), GAPDH (Cell Signaling, 5174 1:2000) and calnexin (Stressgen, SPA-865 1:2000). Loading controls were run on the same gel, and for some experiments Mini PROTEAN® TGX Stain-Free™ Gels (Bio-Rad) were used as loading controls. Signals were acquired using an image analyzer (Bio-Rad, ChemiDoc MP Imaging System) and images were analyzed and prepared using ImageJ.

For additional measurements of eIF4E phosphorylation state, the AlphaLISA SureFire Ultra p-eIF4E (Ser209) Assay Kits (PerkinElmer) were used according to the manufactures protocol. AlphaLISA signals were measured using a Tecan SPARK plate reader on recommended settings.

Immunohistochemistry and imaging

Animals were transcardially perfused with fixative (4% paraformaldehyde in 100mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) at P26-P32. Brains were post-fixed overnight at 4°C, incubated in 30% sucrose in 1xPBS for 48h, and snap frozen on dry ice. Tissues were sectioned at 35 μm on a cryostat (Microm HM650, Thermo Scientific). Floating sections were kept in 1×PBS before incubation with blocking solution containing 0.5% Triton X-100 in 1× TBS and 10% normal donkey serum. The slices were incubated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight and washed three times in 1× TBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100, followed by incubation for 2 hours at room temperature with a secondary antibody. The sections were washed three times in 1× TBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 before mounted onto microscope slides with ProLong Gold antifade (Invitrogen, p36930). For post-hoc confirmation of TH positive cells after electrophysiology, the sections were fixed in the same fixative as described above, washed 3× with 1× PBS before blocking and incubation with anti-TH antibody using same method as above. The following primary antibodies were used for this study: sheep anti-TH (Millipor, AB1542, 1:1000) and mouse-anti neurophysin-1 (Millipore, MABN844, 1:2000). Secondary antibodies used were: donkey anti-sheep IgG-Cy3 (713-165-147), donkey anti-sheep Cy5 (713-175-147), donkey anti-rabbit IgG Cy3 (711-165-152), goat anti-mouse Cy2 (714-225-150) all from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Streptavidin DyLight 488 (Thermo Scientific #21832, 1mg/ml), was used to visualize biocytin. Hoechst dye was co-applied with the secondary antibody at a final concentration of 0.5 μg/ml. Images were acquired on a custom-made dual spinning disk microscope (Life Imaging Services GmbH, Basel Switzerland) using 10× and 40× objectives. Images were taken bilaterally along the whole VTA and PVN dorso-ventral axis and images from at least 4 (VTA) or 5 (PVN) planes were analyzed. OXT+ cells in the PVN were counted manually. Neurophysin-1 area coverage and puncta intensity was measured using the particle measurement tool in ImageJ on sum projections. All images within each experiment were processed in parallel with identical settings using ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop CS 8.0 (Adobe systems).

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

Mice were deeply anesthetized using isoflurane inhalation. Brains were quickly removed and snap frozen on dry ice prior to storage at −80°C. Brains were cut on a cryostat into 10 μm sections, adhered to Superfrost ultra plus slides (Thermo Scientific) and stored at −80°C. Sections were fixed for 30 min in 4% PFA before being processed using the RNAscope® Fluorescent Multiplex Kit (ACD) according to the manufacturers instruction. The following probes were used: oxtr (C3 #412171), v1ar (C3 # 418061), th (Slc6a3-C2, #315441) and nlgn3 (C1 #497661). Probes were combined as oxtr/th/nlgn3 or v1ar/th/nlgn3. Amp-4-Alt B were used for all combinations. Sections were imaged on a custom-made dual spinning disk microscope (Life Imaging Services GmbH, Basel Switzerland) using 40× objective, with 12 section z-stacks with 0.2 um in-between z sections. Images were processed in ImageJ by doing sum projection of the z-stacks, followed by analysis of fluorescent intensity and number of puncta. Cell types were identified based on the presence of th and DAPI. A region of interest (ROI) was drawn around the cell to define the area using DAPI, and only cells with no adjacent DAPI staining was used to avoid false positives from signals from a second cell. Dots in the ROI were manually counted and fluorescent intensity was analyzed using ImageJ. Images were assembled with identical settings using ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop CS 8.0 (Adobe systems).

Cell culture

Cortical cultures were prepared from E16.5 mouse embryos. Neocortices were dissociated by addition of papain (130 units, Worthington Biochemical LK003176) for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were maintained in neurobasal medium (Gibco 21103-049) containing 2% B27 supplement (Gibco 17504-044), 1% Glutamax (Gibco 35050-038), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma P4333). At DIV14, the cells were treated with either vehicle (DMSO) or different doses of ETC-168 for 3 hours before harvesting for western blot.

Proteomic analysis

VTA tissue was microdissected from coronal sections using anatomical landmarks. Dissected tissue was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Successful recovery of proteins from dopaminergic neurons was confirmed by quantitative assessment of enrichment of dopaminergic markers (dopamine transporter, tyrosine hydroxylase, dopamine decarboxylase) as compared to other brain regions (Extended data Fig.4a).

Sample preparation for LC-MS analysis

Tissue was washed twice with PBS and dissolved in 50 μl lysis buffer (1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1M ammoniumbicarbonate), reduced with 5mM TCEP for 15 min at 95°C and alkylated with 10mM chloroacetamide for 30min at 37°C. Samples were digested with trypsin (Promega) at 37°C overnight (protein to trypsin ratio: 50:1). To each peptide samples an aliquot of a heavy reference peptide mix containing 10 chemically synthesized proteotypic peptides (Spike-Tides, JPT, Berlin, Germany) was spiked into each sample at a concentration of 5 fmol of heavy reference peptides per 1μg of total endogenous protein mass. Then, the peptides were cleaned up using iST cartridges (PreOmics, Munich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were dried under vacuum and stored at −80 °C until further use.

Targeted PRM-LC-MS analysis of protein isoforms

In a first step, parallel reaction-monitoring (PRM) assays57 were generated from a mixture containing 100 fmol of each heavy reference peptide and shotgun data-dependent acquisition (DDA) LC-MS/MS analysis on a Thermo Orbitrap Fusion Lumos platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The setup of the μRPLC-MS system was as described previously (Pubmed-ID: 27345528). Chromatographic separation of peptides was carried out using an EASY nano-LC 1200 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific), equipped with a heated RP-HPLC column (75 μm × 30 cm) packed in-house with 1.9 μm C18 resin (Reprosil-AQ Pur, Dr. Maisch). Peptides were analyzed per LC-MS/MS run using a linear gradient ranging from 95% solvent A (0.15% formic acid, 2% acetonitrile) and 5% solvent B (98% acetonitrile, 2% water, 0.15% formic acid) to 45% solvent B over 60 minutes at a flow rate of 200 nl/min. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed on Thermo Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer equipped with a nanoelectrospray ion source (both Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each MS1 scan was followed by high-collision-dissociation (HCD) of the 10 most abundant precursor ions with dynamic exclusion for 20 seconds. Total cycle time was approximately 1 s. For MS1, 1e6 ions were accumulated in the Orbitrap cell over a maximum time of 100 ms and scanned at a resolution of 120,000 FWHM (at 200 m/z). MS2 scans were acquired at a target setting of 1e5 ions, accumulation time of 50 ms and a resolution of 30,000 FWHM (at 200 m/z). Singly charged ions and ions with unassigned charge state were excluded from triggering MS2 events. The normalized collision energy was set to 30%, the mass isolation window was set to 1.4 m/z and one microscan was acquired for each spectrum.

The acquired raw-files were database searched against a mouse database (Uniprot, download date: 2017/04/18, total of 34,490 entries) by the MaxQuant software (Version 1.0.13.13). The search criteria were set as following: full tryptic specificity was required (cleavage after lysine or arginine residues); 3 missed cleavages were allowed; carbamidomethylation (C) was set as fixed modification; Arg10 (R), Lys8 (K) and oxidation (M) as variable modification. The mass tolerance was set to 10 ppm for precursor ions and 0.02 Da for fragment ions. The best 6 transitions for each peptide were selected automatically using an in-house software tool and imported to Skyline (version 4.1 (https://brendanx-uw1.gs.washington.edu/labkey/project/home/software/Skyline/begin.view). A mass isolation lists containing all selected peptide ion masses were exported form Skyline, split into 8 mass lists by charge, c-terminal amino acid and transition and precursor ions. The mass lists were then imported into the Lumos operating software for SureQuant analysis using the following settings: The resolution of the orbitrap was set to 30k (120k) FWHM (at 200 m/z) for heavy (light) peptide ions and the fill time was set to 54 (246) ms, respectively, to reach a target value of 1e6 ions. Ion isolation window was set to 0.4 Th and the scan range was set to 150-1500 Th. The mass window for triggering heavy PRM scans was set to 10 ppm and the depended PRM triggering threshold for the light channel was set to a minimum of 2 detected transitions. A MS1 scan using the same conditions are for DDA was included in each MS cycle. Each condition was analyzed in biological quadruplicates or quintuplicates. All raw-files were imported into Skyline for protein / peptide quantification. To control for variation in sample amounts, the total ion chromatogram (only comprising peptide ions with two or more charges) of each sample was determined by Progenesis QI (version 2.0, Waters) and used for normalization. A summary of the peptides used is displayed in Supplementary Table 1.

Global Proteome analysis using shotgun proteomics

1 μg of peptides of each sample were subjected to LC–MS analysis using a using a Q-Exactive HF mass spectrometer connected to an electrospray ion source (both Thermo Fisher Scientific) as recently specified58 and a custom-made column heater set to 60°C. In brief, peptide separation was carried out using an EASY nLC-1000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a RP-HPLC column (75μm × 30cm) packed in-house with C18 resin (ReproSil-Pur C18–AQ, 1.9μm resin; Dr. Maisch GmbH, Ammerbuch-Entringen, Germany) using a linear gradient from 95% solvent A (0.1% formic acid, 2% acetonitrile) and 5% solvent B (98% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) to 45% solvent B over 60 min at a flow rate of 0.2μl/min. 3x106 and 105 ions were accumulated for MS1 and MS2, respectively, and scanned at a resolution of 60,000 and 15,000 FWHM (at 200 m/z). Fill time was set to 110 ms for MS1 and 50 ms for MS2 scans. For MS2, a normalized collision energy of 28% was employed, the ion isolation window was set to 1.4 Th and the first mass was fixed to 100 Th. To determine changes in protein expressions across samples, a MS1 based label-free quantification was carried out. Therefore, the generated raw files were imported into the Progenesis QI software (Nonlinear Dynamics, Version 2.0) and analyzed using the default parameter settings. MS/MS-data were exported directly from Progenesis QI in mgf format and searched against a decoy database of the forward and reverse sequences of the predicted proteome from mus musculus (Uniprot, download date: 2017/04/18, total of 34,490 entries) using MASCOT (version 2.4.1). The search criteria were set as following: full tryptic specificity was required (cleavage after lysine or arginine residues); 3 missed cleavages were allowed; carbamidomethylation (C) was set as fixed modification; oxidation (M) as variable modification. The mass tolerance was set to 10 ppm for precursor ions and 0.02 Da for fragment ions. Results from the database search were imported into Progenesis QI and the final peptide measurement list containing the peak areas of all identified peptides, respectively, was exported. This list was further processed and statically analyzed using our in-house developed SafeQuant R script (SafeQuant, https://github.com/eahrne/SafeQuant 58). The peptide and protein false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 1% using the number of reverse hits in the dataset. All quantitative analyses were performed in biological quintuplicates. Proteins with less than 1 peptide were excluded from the analysis.

The results details of the proteomics experiments carried out including identification scores, number of peptides quantified, normalized (by sum of all peak intensities) peak intensities, log2 ratios, coefficients of variations and p-values for each quantified protein. A summary is displayed in Supplementary table 2.

Global Proteome analysis using tandem mass tags

Sample aliquots (prepared as described above) containing 10 μg of peptides were dried and labeled with tandem mass isobaric tags (TMTpro 16-plex, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To control for ratio distortion during quantification, a peptide calibration mixture consisting of six digested standard proteins mixed in different amounts were added to each sample before TMT labeling as recently described58. After pooling the differentially TMT labeled peptide samples, peptides were again desalted on C18 reversed-phase spin columns according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Macrospin, Harvard Apparatus) and dried under vacuum. TMT-labeled peptides were fractionated by high-pH reversed phase separation using a XBridge Peptide BEH C18 column (3,5 μm, 130 Å, 1 mm × 150 mm, Waters) on an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC system. Peptides were loaded on column in buffer A (ammonium formate (20 mM, pH 10) in water) and eluted using a two-step linear gradient starting from 2% to 10% in 5 minutes and then to 50% (v/v) buffer B (90% acetonitrile / 10% ammonium formate (20 mM, pH 10) over 55 minutes at a flow rate of 42 μl/min. Elution of peptides was monitored with a UV detector (215 nm, 254 nm). A total of 36 fractions were collected, pooled into 12 fractions using a post-concatenation strategy as previously described59, dried under vacuum.

1μg of peptides were LC-MS analyzed as described previously58. Chromatographic separation of peptides was carried out using an EASY nano-LC 1000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific), equipped with a heated RP-HPLC column (75 μm × 37 cm) packed in-house with 1.9 μm C18 resin (Reprosil-AQ Pur, Dr. Maisch). Aliquots of 1 μg total peptides were analyzed per LC-MS/MS run using a linear gradient ranging from 95% solvent A (0.15% formic acid, 2% acetonitrile) and 5% solvent B (98% acetonitrile, 2% water, 0.15% formic acid) to 30% solvent B over 90 minutes at a flow rate of 200 nl/min. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed on Q-Exactive HF mass spectrometer equipped with a nanoelectrospray ion source (both Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each MS1 scan was followed by high-collision-dissociation (HCD) of the 10 most abundant precursor ions with dynamic exclusion for 20 seconds. Total cycle time was approximately 1 s. For MS1, 3e6 ions were accumulated in the Orbitrap cell over a maximum time of 100 ms and scanned at a resolution of 120,000 FWHM (at 200 m/z). MS2 scans were acquired at a target setting of 1e5 ions, accumulation time of 100 ms and a resolution of 30,000 FWHM (at 200 m/z). Singly charged ions and ions with unassigned charge state were excluded from triggering MS2 events. The normalized collision energy was set to 35%, the mass isolation window was set to 1.1 m/z and one microscan was acquired for each spectrum.

The acquired raw-files were searched against a protein database containing sequences of the predicted SwissProt entries of mus musculus (www.ebi.ac.uk, release date 2019/03/27), the six calibration mix proteins58 and commonly observed contaminants (in total 17,412 sequences) using the SpectroMine software (Biognosys, version 1.0.20235.13.16424) and the TMT 16-plex default settings. In brief, the precursor ion tolerance was set to 10 ppm and fragment ion tolerance was set to 0.02 Da. The search criteria were set as follows: full tryptic specificity was required (cleavage after lysine or arginine residues unless followed by proline), 3 missed cleavages were allowed, carbamidomethylation (C), TMTpro (K and peptide n-terminus) were set as fixed modification and oxidation (M) as a variable modification. The false identification rate was set to 1% by the software based on the number of decoy hits. Proteins that contained similar peptides and could not be differentiated based on MS/MS analysis alone were grouped to satisfy the principles of parsimony. Proteins sharing significant peptide evidence were grouped into clusters. Acquired reporter ion intensities in the experiments were employed for automated quantification and statically analysis using a modified version of our in-house developed SafeQuant R script (v2.3, ref.58). This analysis included adjustment of reporter ion intensities, global data normalization by equalizing the total reporter ion intensity across all channels, summation of reporter ion intensities per protein and channel, calculation of protein abundance ratios and testing for differential abundance using empirical Bayes moderated t-statistics. Finally, the calculated p-values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini−Hochberg method. A summary is displayed in Supplementary Table 3.

Raw MS data associated with the manuscript have been deposited in to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE60 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD018808 and 10.6019/PXD018808.

Gene ontology, network and gene set enrichment analysis

Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed using DAVID classification system (https://david.ncifcrf.gov). Proteins significantly different between vehicle treated wild type and Nlgn3 KO (P<0.05) were compared to all proteins detected in the proteomic screen using the GO GOTERM_BP_DIRECT annotation data set with minimum number of hits set to 5 and maximum P-value threshold to 0.05 with Benjamini correction (P<0.05). Network analysis was obtained using String v11 database61. Each node represents a protein altered in Nlgn3KO VTA compared to wild type VTA in vehicle treated conditions, and each edge show protein-protein interaction as determined by experiments and databases. The highest confidence (0.900) was used for interaction scores. Disconnected nodes and networks containing >6 proteins were removed. Gene set enrichment analysis for TMT proteomic data was performed using all proteins detected with at least 2 peptides with PSEA-Quant45. The list of GO terms with a Q-value of Q<0.01 were summarized using REVIGO62 with small (0.5) allowed similarity, and displayed using Cytoscape.

Statistical analysis

The animals were randomly assigned to each group the moment of drug treatment, and minimum 3 independent cohorts were used for behavioral experiments. Statistical analysis was conducted with GraphPad Prism 8 (San Diego, CA, USA). The normality of sample distributions was assessed and when violated non-parametrical tests were used. When normally distributed, the data were analyzed with unpaired t-test for comparison between two groups, while for multiple comparisons one-way ANOVA and repeated measures (RM) ANOVA were used. For the analysis of variance with 2 factors (two-way ANOVA, RM two-way ANOVA and RM two-way ANOVA by both factors), normality of sample distribution was assumed, and followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. Differences in frequency distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. All the statistical tests adopted were two-sided. When comparing two samples distributions similarity of variances was assumed, therefore no corrections were adopted. Outliers were identified using ROUTS test on the most stringent setting (Q=0.1%). Data are represented as the mean ± s.e.m. and the significance was set at P<0.05.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Loss of social recognition in Nlgn3KO mice.

a-b, Mean social interaction time and data for individual mice in the social habituation/recognition test plotted for (a) wild type (n=11) and (b) Nlgn3KO mice (n=12). c,d, Mean social interaction time and data for individual mice plotted for (c) DATCre control mice (n=10) and (d) DATCre::Nlgn3KO mice (n=11). e, Example for validation of targeted gene knockdown (n=8 mice) from AAV2-DIO-miRNL3-GFP viruses (green) in TH-positive cells (red) in the VTA of DATCre mice. f, Quantification of percentage of TH-positive cells in VTA and SNc of DATCre mice that express GFP from the AAV2-DIO-miR-GFP vector (n=8). g, h, Mean social interaction time and data for individual mice plotted for control mice (g, VTA::DA-miR, n=10) and VTA DA-specific Nlgn3 loss-of-function (h, VTA::DA-NL3, n=8) in the social habituation/recognition test. g, Mean social interaction time and data for individual mice plotted for (i) vehicle (n=12) and (j) OXTR-A treated mice (n=11). All error bars are s.e.m. RM one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for planned multiple comparison for a, b, c, g, h, i, j; Friedman test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test for planned multiple comparison for d. See Supplementary information for additional statistics.

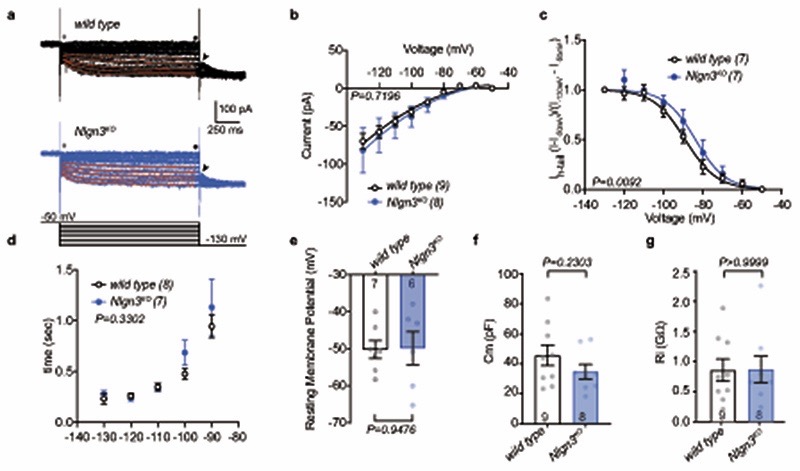

Extended Data Fig. 2. Properties of NAc projecting VTA DA neurons in wild type and Nlgn3KO mice.

(a) Representative Ih currents recorded from wild type (black) and Nlgn3KO (blue) neurons evoked by consecutive hyperpolarizing voltage steps of −10 mV from −50 to −130 mV (bottom panel). At the end of each voltage step the voltage command was returned to −130 mV to evoke tail currents (Ih-tail, depicted with an arrowhead). Red lines show fit of a single exponential function used to assess the Ih activation kinetics. (b) Averaged Ih amplitudes were plotted against the voltage step. Ih current amplitudes were measured at the steady state (indicated with • in a) and the leak current values, as defined as the amplitude of the instantaneous currents at the onset of voltage steps (indicated with an * in a), subtracted. (c) Voltage-dependency of Ih-tail currents. Ih-tail amplitudes were normalized relative to Ih-tail at – 50 mV and −130 mV. Solid lines show fits with a Boltzmann function for least square fit. P-value on graph show difference in V50 between datasets. (d) Activation kinetics of the Ih as determined by the τ values obtained from the exponential fitting, as a function of the voltage commands voltage. Only the values obtained from commands between −130 mV to −90 mV were evaluated. (e) Comparison between groups of the resting membrane potential as assessed with current clamp recordings. (f) Membrane capacitance (Cm) of wild type and Nlgn3KO DA neurons. (g) Input resistant values (Rin) for wild type and Nlgn3KO.Cm and Ri values were obtained in voltage clamp mode by applying a −5 mV (200 ms) voltage command from a holding potential set at −50 mV. All error bars are s.e.m. P-value on graph represent genotype difference. n=5 mice per genotype, numbers on graphs represent cells. RM two-way ANOVA for b; Boltzmann sigmoidal for c; Mixed-effects model for d; unpaired two-sided t-test for e, f; two-sided Mann-Whitney test for g. See Supplementary information for additional statistics.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Oxytocinergic innervation to VTA and vasopressin receptor 1a mRNA levels are not affected in Nlgn3KO mice.

a, Representative images from 3 mice per genotype of neurophysin 1 (green), a cleavage product of the oxytocin neuropeptide precursor that is transported in vesicles together with oxytocin63, and TH (red) immunofluorescence in the VTA of wild type and Nlgn3KO mice. Note that oxytocinergic axons arise from multiple hypothalamic nuclei, including the paraventricular nucleus. b, Mean VTA area coverage and c, puncta fluorescence in the VTA from wild type and Nlgn3KO mice. n= 3 mice per genotype. Number in brackets represent sections. d, Quantification of mean th intensity per TH+ cell. e, Quantification of Nlgn3 puncta per 100um2 TH+ cell. f, Quantification of Oxtr puncta per 100um2 TH+ cell. n=WT: 280 cells from 4 mice; Nlgn3KO: 265 cells from 3 mice for d, e, f. g, targeted proteomic (PRM) measurements for oxytocin receptor (left) and vasopressin receptor 1A (right) proteins in VTA. Number on bars indicate mice. h, Representative images of FISH labeling of avrp1a (cyan), th (red) and Nlgn3 (green) in the VTA from wild type and Nlgn3KO mice. Experiment was repeated independently twice. i, Quantification of mean avpr1a intensity per TH+ cell. j, Quantification of avpr1a puncta per 100um2 TH+ cell from wild type and Nlgn3KO VTA. n: wild type=169 cells from 4 animals; Nlgn3 KO=200 cells from 3 animals for i and j. All error bars are s.e.m. Unpaired two-sided t-test for b, c, g; two-sided Mann-Whitney U test for d, e, f, i, j. See Supplementary information for additional statistics.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Ribosomal proteins and translation processes are altered in Nlgn3KO mice.

a, TMT proteomics: graphs plotting abundance of dopamine markers and synaptic proteins from VTA, cortex and hippocampus. Dopaminergic markers are strongly enriched in VTA samples. n= 5 animals per brain region. b, c, Proteomic analysis of wild type and Nlgn3KO VTA, n=5 mice per genotype. b, Enrichment of GO terms for biological processes for proteins significantly altered (P<0.05) in Nlgn3KO mice compared to wild type. c, Network-based analysis of proteins altered in Nlgn3KO VTA (P<0.01). Blue nodes indicate downregulated proteins, red nodes upregulated proteins, light blue lines indicate interactions known from database and purple lines interactions experimentally determined. Disconnected nodes and nodes containing less than 6 proteins are not shown. See methods for additional information of statistics and analysis parameters. d, Mean puromycin incorporation in acute cortical slices from adult wild type and Nlgn3KO mice. All error bars are s.e.m. Two-sided Mann-Whitney U test for d. See Supplementary information for additional statistics.

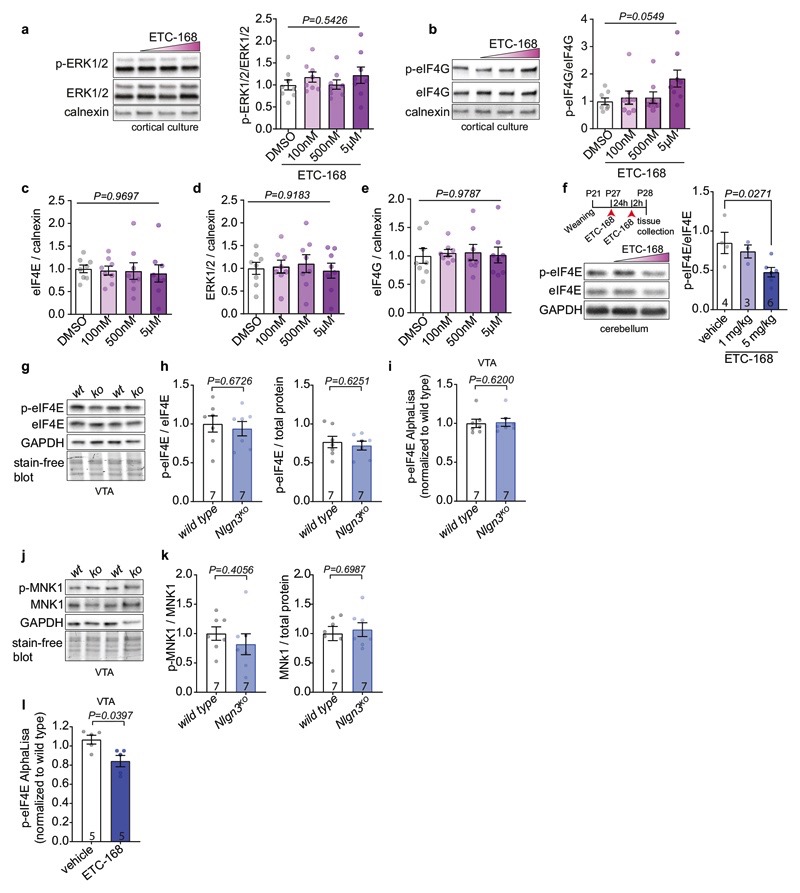

Extended Data Fig. 5. Pharmacological profile of novel MNK1/2 inhibitor ETC-168.

a, b, Quantification of (a) p-ERK1/2 and (b) p-eIF4G levels compared to non-phosphorylated protein in cortical neurons at DIV14 treated with ETC-168. n=8 replicates from 3 independent experiments. c-d, Quantification of (c) eIF4E (d) ERK1/2 and (e) eIF4G levels normalized to calnexin in cortical neurons at DIV14 treated with ETC-168. One-way ANOVA. n=8 replicates from 3 independent experiments. f, Representative western blot of cerebellar lysate from wild type mice treated with vehicle or ETC-168 and quantification of p-eIF4E levels compared to eIF4E. n: vehicle=4; 1 mg/kg=3; 5 mg/kg=6. g, Representative western blot of VTA lysate from wild type mice and Nlgn3KO mice (n=7 mice per genotype). h, Quantification of p-eIF4E compared to eIF4E and eIF4E levels in VTA of wild type mice and Nlgn3KO mice. n= 7 mice per genotype. i, Normalized p-eIF4E AlphaLisa counts from wild type and Nlgn3KO VTA lysate. n= 7 mice per genotype. j, k, Representative western blot (j) and quantification (k) of p-MNK1 and MNK1 levels in VTA lysate from wild type mice and Nlgn3KO mice. n= 7 mice per genotype. l, Normalized p-eIF4E AlphaLisa counts from VTA from wild type treated with 5mg/kg ETC-168 for 24h +2h. n= 5 mice per genotype. All error bars are s.e.m. One-way ANOVA for a, c, d, e, f; Kruskal-Wallis test for b; Unpaired two-sided t-test for h, k; two-sided Mann-Whitney test for i, l. See Supplementary information for additional statistics.

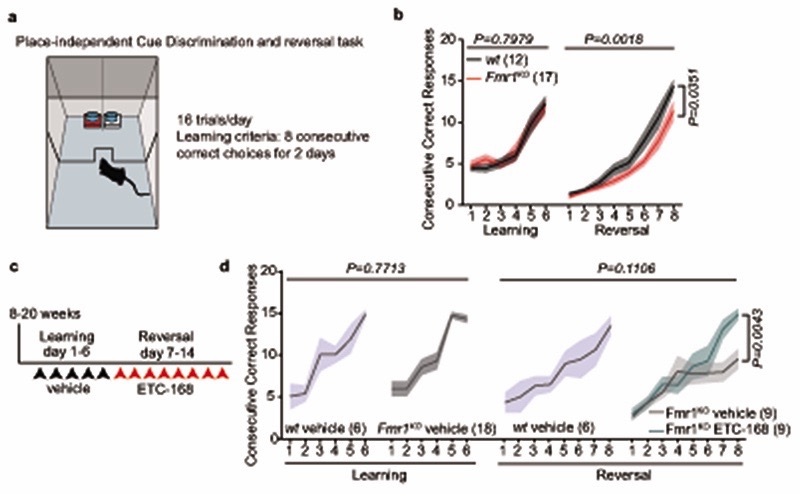

Extended Data Fig. 6. ETC-168 treatment restores cognitive rigidity in Fmr1KO mice.

a, Schematics of the Place-independent cue discrimination and reversal task. This task was chosen given that phenotypes in cognitive rigidity tasks have been replicated in multiple studies on this model. b, Mean consecutive correct responses plotted for Fmr1WT/y and Fmr1KO/y mice. c, Treatment schedule of Fmr1WT/y and Fmr1KO /y mice. Animals were treated daily with vehicle during the learning phase and with 5 mg/kg ETC-168 during the reversal phase 2 hours before the start of the test. d, Mean consecutive correct responses plotted for vehicle treated Fmr1WT /y and vehicle or ETC-168 Fmr1KO/y mice. Numbers in brackets indicate mice. Error bars report s.e.m. RM two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferrroni’s post-hoc test for b, d. See Supplementary information for additional statistics.

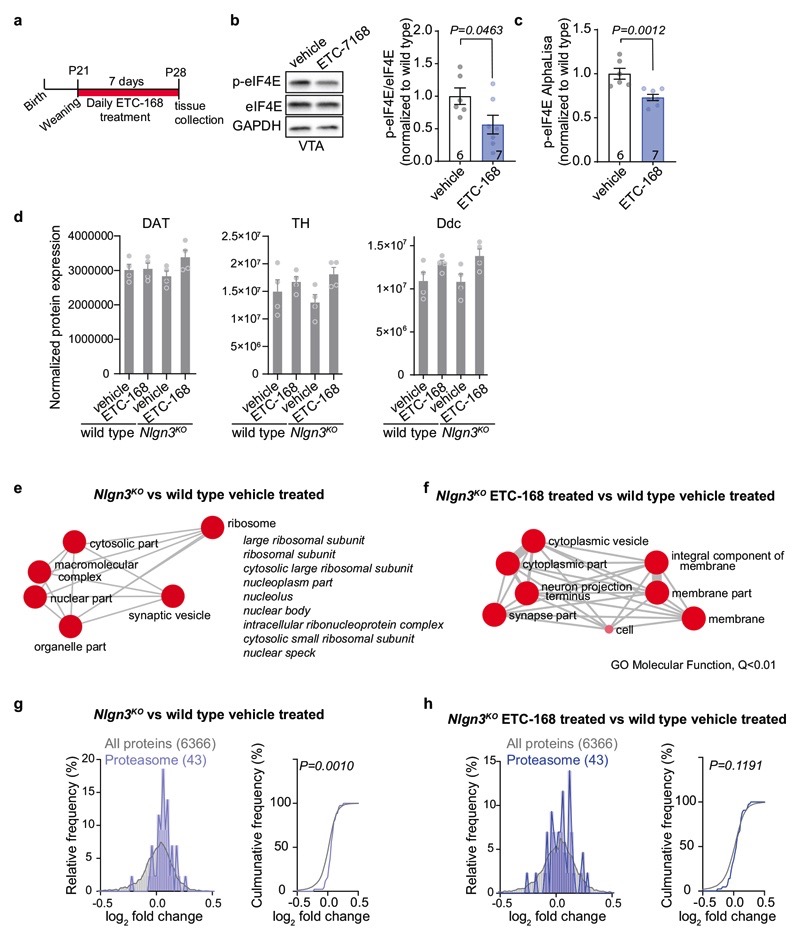

Extended Data Fig. 7. Effect of ETC-168 treatment on protein abundance in wild type and Nlgn3KO mice.

a, Experimental outline. b, Representative western blot and quantification of p-eIF4E compared to eIF4E levels in VTA lysate from wild type mice treated with vehicle or 5mg/kg ETC-168 for 7 consecutive days. n: vehicle=6; ETC-168: 7. c, Normalized p-eIF4E AlphaLisa counts from wild type mice VTA treated with vehicle or 5mg/kg ETC-168 for 7 consecutive days. n: vehicle=6; ETC-168: 7. d, Graphs plotting TMT proteomic normalized protein expression of dopaminergic markers in VTA from vehicle or ETC-168 treated wild type and Nlgn3KO mice. Animals were treated for 7 days. n=4 mice per genotype and treatment. e,f, Graphical representation of Molecular function GO terms enriched in (e) Nlgn3KO versus wild type vehicle treated and (f) Nlgn3KO ETC-168 versus wild type vehicle treated VTA. GO terms were summarized using REVIGO and only terms with Q<0.01 are represented. g,h, TMT proteomic comparison of VTA from (g) vehicle-treated mice and (h) ETC-168 treated Nlgn3KO versus wild type. Relative frequency of log2 fold change in core proteasome n abundance (Nlgn3KO/wild type) is plotted. n= 4 mice per genotype and treatment. All error bars are s.e.m. Unpaired two-sided t-test for b; two-sided Mann-Whitney U test for c. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for g, h. See methods and Supplementary information for additional statistics.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Effect of short-term ETC-168 treatment on social recognition in wild type and Nlgn3KO mice.

a-d, Time course of time interacting in the social habituation/recognition test for mice after short-term treatment with ETC-168. (a) Wild type vehicle (n=12), (b) wild type ETC-168 (n=10), (c) Nlgn3KO vehicle (n=9), and (d) Nlgn3KO ETC-168 (n=11). Error bars report s.e.m. Friedmans test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test for planned multiple comparison for a, c, d, RM one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for planned multiple comparison for b. See Supplementary information for additional statistics.

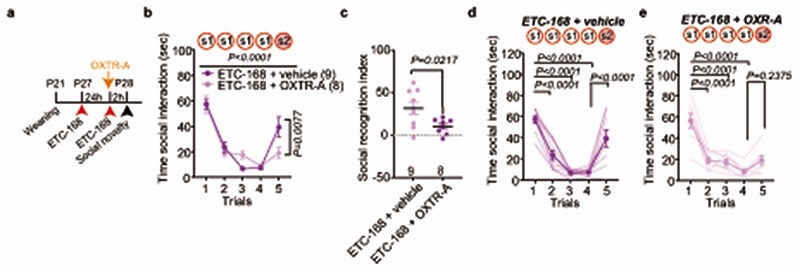

Extended Data Fig. 9. Effect of ETC-168 treatment is dependent on the oxytocin receptor.

a, Experimental outline. b, Mean social interaction time in Nlgn3KO mice treated with 5 mg/kg ETC-168 and either vehicle or 10 mg/kg OXTR-A. Number in brackets indicate mice. c, Social recognition index for Nlgn3KO mice treated with ETC-168 and vehicle, or ETC-168 and OXTR-A. Number on graph indicate mice. d-e, Individual values and mean of time interacting in the social habituation/recognition test after treatment with (d) ETC-168 + vehicle (n=9), or (e) ETC-168 + OXTR-A (n=8). Error bars report s.e.m. RM two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for b; unpaired two-sided t-test for c; RM one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for planned multiple comparison for d, e. See Supplementary information for additional statistics.

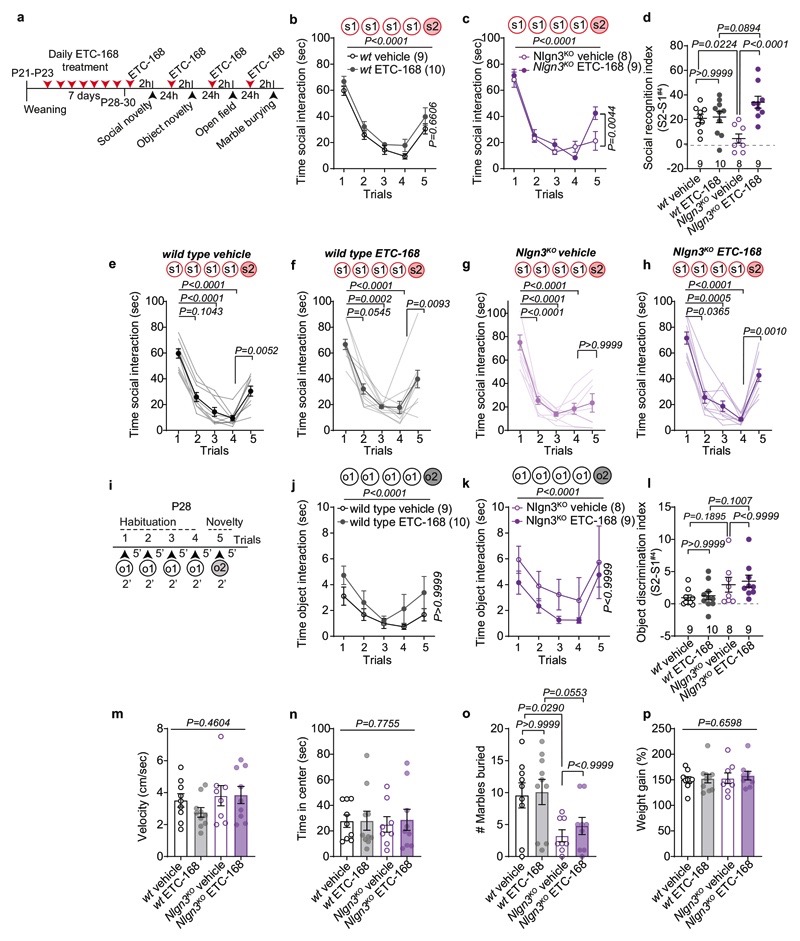

Extended Data Fig. 10. Effect of long-term ETC-168 treatment on behavior in wild type and Nlgn3KO mice.

a, Experimental schematics of chronic ETC-168 treatment and behavior schedule. Number of animals per treatment conditions for all behaviors in b-p: wild type vehicle=9, wild type ETC-168=10, Nlgn3KO vehicle=8, Nlgn3KO ETC-168=9. b, c, Mean social interaction time in (b) wild type and (c) Nlgn3KO mice treated for 8 days with vehicle or 5 mg/kg ETC-168. d, Social recognition index for wild type and Nlgn3KO mice treated with vehicle or 5 mg/kg ETC-168. Numbers in brackets indicate mice. e-f, Individual values and mean time interacting in the social habituation/recognition test after chronic treatment with ETC-168 for (e) wild type vehicle (n=9), (f) wild type ETC-168 (n=10), (g) Nlgn3KO vehicle (n=8), and (h) Nlgn3KO ETC-168 (n=9). i, Experimental schematics of object habituation/recognition test in juvenile mice. j-l, Mean object interaction time plotted for (j) wild type and (k) Nlgn3KO mice. P-value above graphs report Trial. l, Object recognition index. m, Mean velocity (cm/sec) in an open field arena during 7 min. n, Time spend in center of the open field arena. o, Number of marbles buried during a 30 minutes marble burying test. p, Percentage weight gain in wild type and Nlgn3KO mice treated with ETC-168 or vehicle. P-value for treatment is displayed on graphs. Error bars report s.e.m. RM two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for genotype and treatment for b, c, j, k; RM two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for genotype and treatment for d, l, o; Friedman test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test for planned multiple comparison for e, f, h; One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for planned multiple comparison for g; RM two-way ANOVA for m, n, p. See Supplementary information for additional statistics.

Supplementary Material

The file contains a table of detailed description of statistical analyses used in this study and uncropped gel images corresponding to Figure 3, Extended data Figure 4, 5 and 7.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Andrea Gomez, Kelly Tan, Lisa Traunmüller, and Federica Filice for comments on the manuscript and to members of the Scheiffele Lab for discussions. We thank Dr. Benjamin Boury Jamot for performing tests on Fmr1KO mice, Federica Filice for experimental support, and Dr. Alex Schmidt and the Biozentrum Proteomics Core Facility for conducting proteomics analysis.

Funding

H.H. was supported by a Long-term Fellowship from the Human Frontiers Science Program. This work was supported by funds to P.S. from the Swiss National Science Foundation, a European Research Council Advanced Grant (SPLICECODE), EU-AIMS and AIMS-2-TRIALS which are supported by the Innovative Medicines Initiatives from the European Commission. The results leading to this publication has received funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking under grant agreement No 777394. This Joint Undertaking receives support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and EFPIA and AUTISM SPEAKS, Autistica, SFARI. The Scheiffele Laboratory is an associate member of the Swiss National Science Foundation’s National Competence Centre for Research (NCCR) RNA & Disease. F.M. was supported by NCCR SYNAPSY. Discovery of ETC-168 was financially supported by Biomedical Sciences Institutes (BMSI) and Joint Council Office (JCO Project 11 03 FG 07 05), Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), Singapore.

Footnotes

Author contributions

This work was jointly conceived by H.H. and P.S. and built on initial findings and S.B. and P.S. MNK inhibitors were developed by A.M. and K.N., behavioral assays were developed by H.H. and F.M., experimental procedures were performed by H.H., D.S., F.M., L.H.-B., C.B., E.P.-G., data analysis was conducted by H.H., D.S., E.P-G., F.M., P.S., E.P.-V. The manuscript was jointly written by H.H. and P.S., with editing provided by E.G.-P., E.P.-V., S.B. and K.N.

Data deposit statement

Proteomic data was deposited at PRIDE (PXD018808 and 10.6019/PXD01880). All renewable reagents and detailed protocols will be made available on request.

Competing interests

S.B. P.S. A.M. and K.N. have filed patents on the use of MNK inhibitors for treatment of neurodevelopmental disorders. A.M. and K.N. are current or former employees of the Experimental Therapeutics Centre Singapore which has a commercial interest in the development of MNK1/2 inhibitors.

References

- 1.de la Torre-Ubieta L, Won H, Stein JL, Geschwind DH. Advancing the understanding of autism disease mechanisms through genetics. Nature medicine. 2016;22:345–361. doi: 10.1038/nm.4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Roak BJ, et al. Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature. 2012;485:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature10989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iossifov I, et al. De novo gene disruptions in children on the autistic spectrum. Neuron. 2012;74:285–299. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamasue H, Aran A, Berry-Kravis E. Emerging pharmacological therapies in fragile X syndrome and autism. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019 doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolognani F, et al. A phase 2 clinical trial of a vasopressin V1a receptor antagonist shows improved adaptive behaviors in men with autism spectrum disorder. Science translational medicine. 2019;11 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat7838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker KJ, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled pilot trial shows that intranasal vasopressin improves social deficits in children with autism. Science translational medicine. 2019;11 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau7356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walum H, Young LJ. The neural mechanisms and circuitry of the pair bond. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19:643–654. doi: 10.1038/s41583-018-0072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolen G, Darvishzadeh A, Huang KW, Malenka RC. Social reward requires coordinated activity of nucleus accumbens oxytocin and serotonin. Nature. 2013;501:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cataldo I, Azhari A, Esposito G. A Review of Oxytocin and Arginine-Vasopressin Receptors and Their Modulation of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2018;11:27. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson JN, et al. Social amnesia in mice lacking the oxytocin gene. Nat Genet. 2000;25:284–288. doi: 10.1038/77040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oettl LL, et al. Oxytocin Enhances Social Recognition by Modulating Cortical Control of Early Olfactory Processing. Neuron. 2016;90:609–621. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung LW, et al. Gating of social reward by oxytocin in the ventral tegmental area. Science (New York, NY. 2017;357:1406–1411. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao L, Priest MF, Nasenbeny J, Lu T, Kozorovitskiy Y. Biased Oxytocinergic Modulation of Midbrain Dopamine Systems. Neuron. 2017;95:368–384 e365. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sgritta M, et al. Mechanisms Underlying Microbial-Mediated Changes in Social Behavior in Mouse Models of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuron. 2019;101:246–259 e246. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penagarikano O, et al. Exogenous and evoked oxytocin restores social behavior in the Cntnap2 mouse model of autism. Science translational medicine. 2015;7:271ra278. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ebert DH, Greenberg ME. Activity-dependent neuronal signalling and autism spectrum disorder. Nature. 2013;493:327–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanders SJ, et al. Multiple recurrent de novo CNVs, including duplications of the 7q11.23 Williams syndrome region, are strongly associated with autism. Neuron. 2011;70:863–885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilman SR, et al. Rare de novo variants associated with autism implicate a large functional network of genes involved in formation and function of synapses. Neuron. 2011;70:898–907. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka KF, et al. Flexible Accelerated STOP Tetracycline Operator-knockin (FAST): a versatile and efficient new gene modulating system. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:770–773. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichtchenko K, Nguyen T, Sudhof TC. Structures, alternative splicing, and neurexin binding of multiple neuroligins. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2676–2682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Budreck EC, Scheiffele P. Neuroligin-3 is a neuronal adhesion protein at GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:1738–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chih B, Afridi SK, Clark L, Scheiffele P. Disorder-associated mutations lead to functional inactivation of neuroligins. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1471–1477. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]