Abstract

In this study, two stereocomplementary ω-transaminases from Arthrobacter sp. (AsR-ωTA) and Chromobacterium violaceum (Cv-ωTA) were immobilized via iron cation affinity binding onto polymer-coated controlled porosity glass beads (EziG™). The immobilization procedure was studied with different types of carrier materials and immobilization buffers of varying compositions, concentrations, pHs and cofactor (PLP) concentrations. Notably, concentrations of PLP above 0.1 mM were correlated with a dramatic decrease of the immobilization yield. The highest catalytic activity, along with quantitative immobilization, was obtained in MOPS buffer (100mM, pH 8.0, PLP 0.1 mM, incubation time 2 h). Leaching of the immobilized enzyme was not observed within 3 days of incubation. EziG-immobilized AsR-ωTA and Cv-ωTA retained elevated activity when tested for the kinetic resolution of rac-α-methylbenzylamine (rac-α-MBA) in single batch experiments. Recycling studies demonstrated that immobilized EziG3-AsR-ωTA could be recycled for at least 16 consecutive cycles (15min per cycle) and always affording quantitative conversion (TON ca. 14,400). Finally, the kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA with EziG3-AsR-ωTA was tested in a continuous flow packed-bed reactor (157 µL reactor volume), which produced more than 5g of (S)-α-MBA (> 49% conversion, > 99% ee) in 96 h with no detectable loss of catalytic activity. The calculated TON was more than 110,000 along with a space-time yield of 335 g L−1h−1.

Keywords: Metal-ion affinity enzyme immobilization, EziG, Kinetic resolution, ω-transaminase, Flow chemistry, α-chiral amines, Biocatalysis

1. Introduction

Industrial application of biocatalysts has been expanding, particularly in the pharmaceutical and fine chemical industries (Choi et al., 2015; Madhavan et al., 2017; Prasad and Roy, 2018; Schmid et al., 2001). Because of their low environmental impact, elevated catalytic efficiency and exquisite selectivity, enzymes are an appealing option for the synthesis of many high value compounds in batch-as well as continuous flow reactors (Sheldon and Woodley, 2018). However, the majority of biocatalytic processes are still based on the less costly and time-consuming use of whole cell systems (fermenting, resting or lyophilized cells) or crude cell extracts, which do not require steps for enzyme purification. (Choi et al., 2015; Madhavan et al., 2017). An often-common disadvantage of these types of applications is the biocatalysts’ lack of reusability, which reduces chemical turnover numbers (TONs) and increases the environmental impact. Additionally, other proteins present as impurities can catalyze possible side-reactions, thereby negatively affecting the selectivity of the process. Other disadvantages of biocatalytic processes using whole cells include the lower volumetric productivities and the frequent occurrence of cell breakage; the latter process generates debris that can contaminate the reaction medium.

Enzyme immobilization is gaining importance for continuous flow biocatalysis using isolated enzymes (Britton et al., 2018). Recyclability of enzymes, along with increased stability, chemical selectivity as well as operational window can effectively be enabled by immobilization onto a support material, thereby making the enzyme perform as a heterogeneous catalyst (Sheldon, 2007; Sheldon and van Pelt, 2013). Although stabilization is the most common objective for enzyme immobilization, enzyme hyper-activation (Fernandez-Lafuente et al., 1998; López-Serrano et al., 2002; Mingarro et al., 1995; Reetz, 1997), modulation of catalytic selectivity (Palomo et al., 2002a, b; Palomo et al., 2004) and decrease of inhibition of catalytic activity can be also pursued (Fernandez-Lafuente et al., 1999; Mateo et al., 2004; Wilson et al., 2004a, b). Enzyme stabilization is mainly achieved by rigidification of the protein structure by multi-point covalent attachment or multi-subunit immobilization (Mateo et al., 2007; Santos et al., 2015).

Existing techniques of enzyme immobilization are generally categorized as either: (1) encapsulation or entrapment of the enzyme in permeable materials; (2) crosslinking of the enzyme via short molecular linkers; or (3) binding of the enzyme to a carrier material. An example of the first category includes LentiKat’s (lentil-shaped particles) for encapsulation of enzymes (Bajić et al., 2017; Cardenas-Fernandez et al., 2012), whereas cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) are representative of the second category (Liao et al., 2018; Sheldon et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2017). The third and most common method entails the tethering of enzymes on a support material by affinity adsorption, ionic interactions, or covalent binding. Examples of support materials for enzyme immobilization are numerous and provide many advantages in terms of biocatalyst reuse, easier downstream processing and enzyme stabilization (Mateo et al., 2007; Santos et al., 2015; Silva et al., 2018; Zdarta et al., 2018). Support materials are often coated with polymeric structures that bear specific functionalities (such as epoxides or amines) enabling facile enzyme binding. Covalent interactions have been most commonly preferred because they minimize enzyme leaching; however, both the type of carrier material and the method for binding the enzyme are very important for retaining enzyme activity (Rodrigues et al., 2013).

Immobilized metal-ion affinity binding is used in many applications, such as for protein or peptide purification (Ho et al., 2004; Pessela et al., 2007; Porath, 1992) and immobilization (Cao et al., 2017). This technique involves the use of metal ions as chelating agents (e.g. Ni2+, Co2+/3+, Fe2+/3+), onto which specific amino acid residues of the enzyme’s polypeptide chain are coordinated. The chelating metal ions are chemically connected to the support matrix by spacer molecules. The interaction between the enzyme and the chelating metal ion center commonly involves a terminal poly-histidine chain (Hisx-tag), which is genetically attached to the enzyme prior its recombinant expression in a microbial host. Although the use of Hisx-tags very often assures a specific binding between enzyme and metal center, other amino acid residues can also potentially act as chelators. For instance, a multi-point attachment of the enzyme to the support can occur if the support material contains an elevated number of active groups per surface unit. This effect is more pronounced if a support with a flat surface area is used, whereas the incidence is lower if the support is formed by thin fibers (Santos et al., 2015). The physical properties of the surface of the support material as well as the number and chemical strength of enzyme-support interactions are crucial because a single-point and weak binding will likely lead to enzyme leaching during the reaction, whereas an excessive number of strong interactions may result in reduced catalytic activity because of considerable distortion of the enzyme structure (Mateo et al., 2007). However, immobilized metal-ion affinity binding through enzyme’s Hisx-tag normally guarantees high retained catalytic activity and stability since a main (desired) orientation of the enzyme is obtained in most cases, although multi-point attachments could be formed dependent on physical properties and degree of activation of the support material (Santos et al., 2015). Additionally, these latter non-covalent interactions between the enzyme and the surface of the carrier material can contribute to stabilize enzyme regions whose dynamics are important during the catalytic cycle (Cassimjee and Federsel, 2018). Moreover, increased apparent catalytic activity upon immobilization is possible because of the multi-point binding of pre-formed and catalytically active oligomeric structures. This feature is particularly important and can be exploited for hyper-activation of immobilized ω-transaminases (ωTAs), since these enzymes generally form homodimeric structures in which the active site consists of shared amino acid residues coming from the two monomeric units (i.e., the monomeric units are catalytically inactive; Lyskowski et al., 2014; Malik et al., 2012). It is known that the association between the two monomeric units of ωTAs can become labile in solution, particularly in the absence of the pyridoxal-5’-phosphate (PLP) cofactor (Shin et al., 2003). A useful property of metal-ion affinity binding is the potential to detach the enzyme from the support material once its activity has ceased by using chelating reagents, such as imidazole or EDTA. Polymeric materials are generally inexpensive; however, high enzyme loading (> 5% w w−1, enzyme/carrier) on this type of carrier is usually unfeasible due to the limited surface area. In this context, controlled-pore glass (CPG) carriers serve as a better alternative because of their porous skeleton, which provides a larger surface area for immobilization and efficient mass transfer through interconnecting pores.

Recently, a hybrid CPG immobilization material (EziG) was developed whereby the surface of the CPG is coated with a functionalized polymer and the resulting polymeric surface bears chelating groups that are suitable for selective binding of metal ions (Cassimjee and Federsel, 2018; Engelmark Cassimjee and Bäckvall, 2015; Engelmark Cassimjee et al., 2014). Fe3+ was selected as preferred metal ion for EziG immobilization material due to its low environmental impact, virtually absent toxicity and increased binding stability (Cassimjee and Federsel, 2018). The CPG-polymeric functionalized hybrid material creates a highly porous network for selective binding of enzymes with loadings up to 30% (w w−1). Moreover, the selectivity of the binding enables immobilization directly from the cell lysate, thereby precluding the need for enzyme pre-purification (Engelmark Cassimjee et al., 2014). Immobilization carriers with high enzyme loadings might cause enzyme crowding, which can lead to lower enzyme stability (Fernandez-Lopez et al., 2017); however, such behavior was not observed in any study conducted with EziG carrier materials. Immobilization on EziG carrier materials has been reported to significantly improve the stability and operational window of an arylmalonate decarboxylase (Assmann et al., 2017), Candida antarctica lipase (Cassimjee et al., 2017), and a norco-claurine synthase (Lechner et al., 2018). Our group previously reported the co-immobilization of two dehydrogenases on EziG support material and the employment of the co-immobilized system in hydrogen-borrowing amination of alcohols to obtain α-chiral amines with improved efficiency compared to analogous non-immobilized systems (Böhmer et al., 2018; Knaus and Mutti, 2017; Mutti et al., 2015; Thompson and Turner, 2017).

ω-Transaminases (ωTAs) are PLP dependent enzymes that produce α-chiral amines by transferring an amino group from the donor molecule to the carbonyl moiety of the acceptor molecule (Slabu et al. (2017). Application of ωTAs in large scale processes has been demonstrated (Savile et al., 2010); however, the moderate operational stability upon immobilization hampers the full exploitation of the otherwise tremendous potential of this class of enzymes in organic synthesis. Immobilization of ω-transaminases has been reported in a number of recent studies aimed at improving the overall performance of biocatalysts (Abaházi et al., 2018; Alami et al., 2018; Basso et al., 2018; de Souza et al., 2016d; Jia et al., 2016; Mallin et al., 2014; Neto et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2017; Truppo et al., 2012). Current limitations appear to be the relatively low enzyme loading (per mass unit of carrier material), as well as the moderate operational stability upon immobilization. Co-immobilization of transaminase and PLP cofactor via metal-ion affinity binding has been recently reported; however, pre-functionalization of the immobilization carrier was required (Benítez-Mateos et al., 2018).

In this study, we studied the conditions for the optimal immobilization of two stereocomplementary ω-transaminases on EziG carrier materials based on the use of different types of immobilization buffers (i.e., composition, concentration, pH) at varied concentrations of PLP cofactor. The performance of the resulting immobilized biocatalysts was then evaluated for the kinetic resolution of rac-α-methylbenzylamine (rac-MBA) as a test reaction in both batch- and flow systems.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Chemicals and carrier materials

Acetophenone, rac-α-methylbenzylamine (rac-α-MBA), (S)-α-methylbenzylamine ((S)-α-MBA), (R)-α-methylbenzylamine ((R)-α-MBA), and pyridoxal-5’-phosphate (PLP) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and sodium pyruvate were purchased from TCI Europe (Zwijndrecht, Belgium). The following EziG enzyme carrier materials were provided by EnginZyme AB (Stockholm, Sweden): EziG1 (Fe-Opal); EziG2 (Fe-Coral) and EziG3 (Fe-Amber). Further details for equipment and analytical determination are available in SI, section 2.

2.2. Expression and purification of ω-transaminases

C-terminal His-tagged (R)-selective ω-transaminase from Arthrobacter sp. (AsR-ωTA, pET21a) (Iwasaki et al., 2012; Mutti et al., 2011) and N-terminal His-tagged (S)-selective ω-transaminase from Chromobacterium violaceum (Cv-ωTA, pET28b) (Kaulmann et al., 2007; Koszelewski et al., 2010, 2009) were expressed using Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) as a host organism: 800 mL of LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg mL−1 for pET21a) or kanamycin (50 µg mL−1 for pET28b) were inoculated with 15 mL of an overnight culture. Cells were grown at 37 °C until an OD600 of 0.6 – 0.9 was reached, and the expression of the proteins was induced by the addition of IPTG (0.5 mM final concentration). Protein expression was conducted overnight at 25 °C, and after harvesting of the cells (4 °C, 4500 rpm, 15 min), the remaining cell pellet was re-suspended in Lysis buffer (50 mM KH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). Cells were disrupted by sonication and PLP (0.5 mM final concentration) was added to the cell lysate. After centrifugation (4 °C, 14,000 rpm, 45 min.), the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 µm filter and protein purification was performed by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA HisTrap FF columns (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After loading of the filtered lysate, the column was washed with sufficient amounts of washing buffer (50 mM KH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 25 mM imidazole, pH 8.0), and the target enzyme was recovered with elution buffer (50 mM KH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 200 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). The process of purification was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Figure S1). Fractions containing sufficiently pure protein were pooled and dialyzed overnight against potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 8). Protein solutions were concentrated and their concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically using a Bradford assay (see SI section 6.2 for details). Protein yields were 285 mg L−1 of cell culture (36 mg g−1 cell pellet) for AsR-ωTA and 100 mg L−1 of cell culture (30 mg g−1 cell pellet) for Cv-ωTA. Enzymes were shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C.

2.3. Optimized conditions for immobilization on EziG carrier materials (analytical scale)

A vial containing 10 ± 0.2 mg of EziG carrier material was cooled down in an ice bath and suspended in the immobilization buffer (MOPS, 1 mL, 100 mM, pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.1 mM PLP. Purified ω-TA (1 or 2 mg, equal to 10–20% w w−1, enzyme loading to support material) was added to the suspension, and the mixture was shaken with an orbital shaker (120 rpm) for 2h at 4 °C. Small aliquots from the aqueous phase (20 µL) were sampled before and after the immobilization procedure, their concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay (see SI section 6.2 for details), and the immobilization yield was calculated (see SI section 3 for details). The immobilized enzyme was left to sediment, the buffer was removed by pipetting, and the immobilized enzyme was used directly in biotransformations.

The same procedure was followed for immobilization at a larger scale, typically using 15 mg of purified ωTA and 100 mg of EziG carrier material. Full immobilization was obtained after 1.5 h (final enzyme loading per carrier material 15%, w w−1).

2.4. Optimized conditions for kinetic resolution with EziG-immobilized ω-transaminases

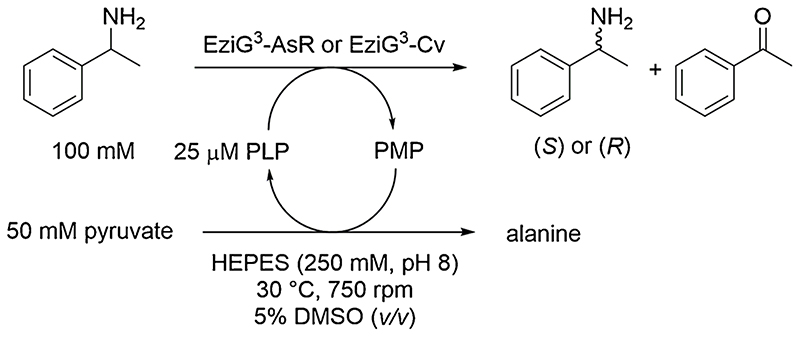

EziG-immobilized ω-transaminases (EziG3-AsR or EziG3-Cv, 10 or 20%, w w−1, enzyme loading per unit carrier material) were employed for the kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA with pyruvate as the aminogroup acceptor (Scheme 1). Batch reactions were performed on analytical scale (0.5 mL) at 30 °C from 15 min or up to 3 h, depending on the type of experiment.

Scheme 1.

Immobilized ω-transaminases in kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA (100 mM) with sodium pyruvate (50 mM).

All stock aqueous solutions were prepared in HEPES buffer (250 mM, pH 7). EziG-immobilized ω-transaminase (10 ± 0.2 mg, 10 or 20%, w w−1, enzyme loading to support material) was suspended in HEPES buffer (112.5 µL, 250 mM, pH 7), to which 12.5 µL of a 1 mM PLP stock solution (final concentration in solution 25 µM) was added, along with 125 µL of a 200 mM sodium pyruvate stock solution (final concentration in solution 50 mM) and 250 µL of a 200 mM rac-α-MBA stock solution in DMSO/HEPES buffer (final concentration rac-α-MBA 100 mM and DMSO 5%, v v−1). The reactions were shaken at 30 °C in an Eppendorf thermomixer (750 rpm). The immobilized enzyme was left to sediment and the reaction mixture was separated from the biocatalyst by pipetting. The reaction mixture was basified with KOH (100 µL, 5 M) and extracted with EtOAc (2 x 500 µL), and the combined organic phase was dried over MgSO4. Analysis of the samples for conversion determination was conducted using GC-FID equipped with an achiral column (see SI section 2 for analytical details). For the determination of the enantiomeric excess, derivatization of the samples was performed with 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, 50 mg mL−1) in acetic anhydride (100 µL per sample) shaken with an orbital shaker (170 rpm) for 30 min at 25 °C. The samples were quenched by adding water (300 µL) and shaken again (170 rpm) for 30 min at 25 °C. The organic layer was collected, dried over MgSO4, and enantiomeric excess was measured on GC equipped with a chiral column (see SI section 2 for analytical details).

2.5. In-flow immobilization from purified enzyme solution

AsR-ωTA (15 mg, 403 nmol of purified enzyme) was diluted in MOPS buffer (10 mL, 100 mM, pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.1 mM PLP in an ice bath at 4 °C. A stainless steel column (50 mm length x 2 mm diameter) was filled with EziG material (100 mg) and hydrated by flowing MOPS buffer into the column (50 mL, 100 mM, pH 7.5, flow 0.5 mL min−1). Then, the diluted stock solution of AsR-ωTA was loaded onto the column using a peristaltic pump (flow rate = 300 µL min−1). MOPS buffer (30 mL, 100 mM, pH 7.5) was flowed through the column to wash out any possibly unbound protein. Buffer samples (20 µL) of the loading enzyme solution and of the flow-through obtained during washing were taken and the enzyme concentration was measured in both samples using the Bradford assay (see SI section 6.2 for details) in order to calculate the immobilization yield (see SI section 3 for details). Immobilization was quantitative; thus, the final enzyme loading per unit of carrier material was 15% enzyme loading, w w-1. The column containing EziG-AsR was conditioned by flowing HEPES buffer (30 mL, 250 mM, pH 7, 25 µM PLP, flow 0.5 mL min−1) and subsequently mounted on a Dionex P680 HPLC pump unit equipped with flow controller. This set-up was used for continuous flow kinetic resolution experiments.

2.6. In-flow immobilization from crude cell extract (i.e.,cell lysate)

Immobilization directly from cell lysate of ωTA is of particular interest for large scale application and was performed as follows. While cooling at 4 °C on an ice bath, an E. coli pellet containing overexpressed AsR-ωTA (0.62 g of cells, 36 mg g−1 cells) was suspended in MOPS buffer (6 mL, 100 mM, pH 7.5) and disrupted by sonication. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation (4 °C, 14,000 rpm, 45 min), and the soluble fraction containing the enzyme (23% w w−1 to carrier material) was filtered (0.45 µm filter pores). A stainless-steel column (50 mm length x 2 mm diameter) was filled with EziG3 Fe-Amber (100 mg) and hydrated with MOPS buffer (50 mL, 100 mM, pH 7.5, flow 0.5 mL min−1). The soluble protein fraction was loaded onto the column using a peristaltic pump (flow rate = 150 µL min−1, residence time 63 s). After complete loading (6 mL), the flow was stopped, and the cell lysate was left to incubate in the column for 45 min at 20 °C. We noticed that this incubation time somehow resulted in the avoidance of even minor enzyme leaching during the subsequent washing steps and reaction. Then, MOPS buffer (50 mL, 100 mM, pH 7.5, flow 0.5 mL min-1) was flowed through the column to wash out any possibly unbound component (e.g. endogenous E. coli proteins). The column containing the immobilized AsR-ωTA was conditioned by flowing further with HEPES buffer (30 mL, 250 mM, pH 7, 25 µM PLP) and subsequently mounted on a Dionex P680 HPLC pump unit equipped with flow controller. The amount of immobilized AsR-ωTA per unit of carrier EziG material was calculated to be 19%, w w−1 based on the difference between protein content in the loading fraction and protein content in the washing fractions (via Bradford assay). The determination through quantitative analysis of protein fractions on SDS PAGE yielded the same result.

2.7. Continuous flow kinetic resolution with EziG-immobilized ω-transaminases

ω-Transaminase was immobilized on EziG carrier material (100 mg carrier plus enzyme, 15% loading w w-1) in a stainless-steel column (50 mm length x 2 mm diameter). A Dionex P680 HPLC pump unit was flushed with HEPES buffer (250 mM, pH 7, 25 µM PLP). The column containing EziG-ωTA was connected to the flow system and heated up to 30 °C in a water bath.

The reaction mixture was prepared as follows. Sodium pyruvate (5.4 g, 49.5 mmol, 55 mM final concentration) was dissolved in HEPES buffer (900 mL final volume, 250 mM, pH 7), and rac-α-MBA (11.6 mL, 10.9 g, 90 mmol, 100 mM final concentration) was pre-dissolved in DMSO (final cosolvents concentration 10% v v−1) prior to addition to the HEPES buffer containing the sodium pyruvate. Then, the pH was adjusted to pH 7 and PLP (25 µM final concentration) was added. The solution was stirred for 1 h at RT in the dark. The reaction mixture was pumped through the column (average flow rate: 0.175 mL min−1), and the product mixture was collected in fractions (ca. 8 mL each hour during the first day of operation, and then 200 mL during nighttime and 100 mL during the daytime). The column was operated for 96 consecutive hours without any detectable decrease of catalytic performance. A small aliquot of each fraction (0.5 mL) was basified with KOH (100 µL, 5M) and extracted with EtOAc (2 x 500 µL). The organic layers were combined, dried over MgSO4 and analyzed with GC equipped with an achiral column (see SI section 2 for analytical details). GC-analysis showed that the kinetic resolution proceeded quantitatively (> 49% conversion). The final work-up was performed by initial acidification of the combined collected product fractions to pH 2 with HCl (37%), followed by extraction of the acetophenone byproduct with MTBE (3x300mL). Then, the aqueous phase was basified to pH 14 with KOH (5 M), and the product was extracted with MTBE (3 x 300 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over MgSO4 and the solvent was removed by reduced pressure to obtain 5.05 g of pure (S)-α-MBA (42 mmol, 93% isolated yield) in perfect optical purity (> 99% ee).

2.8. SEM analysis

Scanning electron micrographs (SEM) of EziG material with immobilized AsR-ωTA were obtained with a FEI Verios 460 scanning electron microscope in secondary-electron mode. An acceleration voltage of 2-5 kV was used with a beam current of 100 pA at a working distance of 4 mm, and the field immersion mode was applied for an optimized resolution. Samples were placed onto an aluminum stub with carbon film and dried for several hours at 40 °C under vacuum before measurement. Selected samples were also sputter-coated with a layer of Cr (20 nm).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Enzyme expression and purification

Among the pool of available ω-transaminases, we chose two stereocomplementary enzymes for the immobilization studies: 1) the (R)-selective ω-transaminase from Arthrobacter species (AsR-ωTA) (Iwasaki et al., 2012; Mutti et al., 2011); and 2) the (S)-selective ω-transaminase from Chromobacterium violaceum (Cv-ωTA) (Kaulmann et al., 2007; Koszelewski et al., 2010, 2009). Both enzymes have been extensively studied in the past decade and display perfect stereoselectivities for the amination of a large number of structurally diverse prochiral ketones. Although not technically required and actually inconvenient for an applied industrial process, we decided to use purified enzymes for this study due to the high accuracy and precision in quantifying the resulting actual amount of immobilized enzyme on the carrier material. In this manner, an exact evaluation of the catalytic performance (e.g., TON or initial activity) was possible. Nonetheless, the efficiency for the selective immobilization of ωTA from crude lysate on EziG3 was demonstrated as described in “Material and methods” (Section 2.6). Specifically, the final enzyme loading on carrier material was 19% w w−1, which correlates to an estimated yield of immobilization from cell lysate of ca. 90% (without optimization). In a previous study, enzyme loading up to 29% (w w−1) was achieved for Cv-ωTA onto EziG carrier (Engelmark Cassimjee et al., 2014). For our experiments with purified ω-transaminases, we typically applied an enzyme loading of 10% w w−1 for batch reactions and 15% w w−1 for flow reactions, respectively

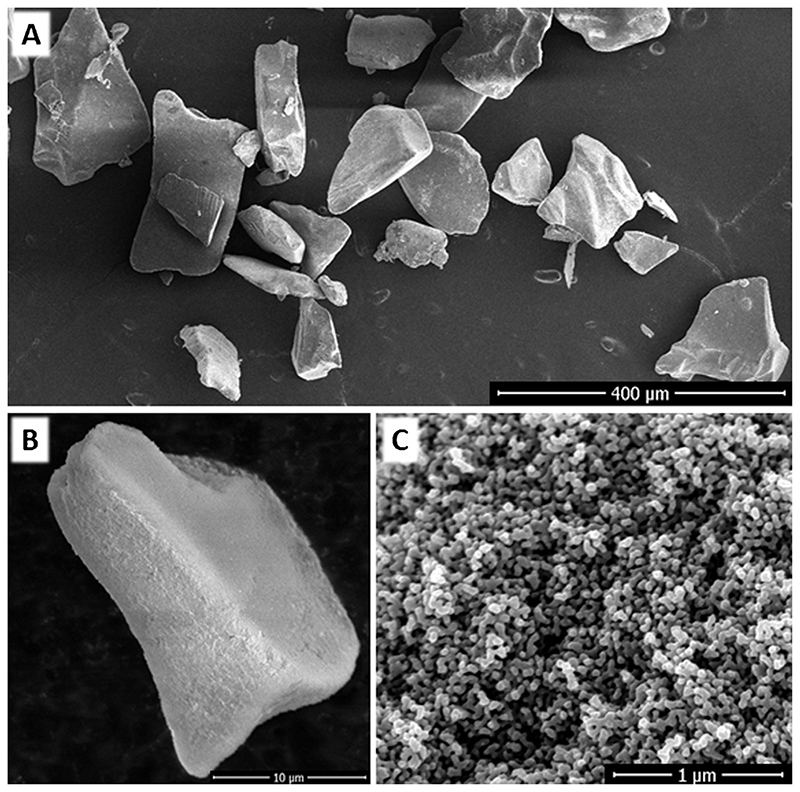

3.2. EziG carrier materials

Three types of EziG enzyme carrier material possessing distinct surface properties were tested for initial experiments: EziG1 (Fe-Opal), has a hydrophilic derivatized silica surface; EziG2 (Fe-Coral) has a hydrophobic surface polymer; and EziG3 (Fe-Amber) is covered with a semi-hydrophobic polymer surface (see SI, Table S2 for EziG product specifications). Fig. 1 displays scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of EziG3 Fe-Amber material, which show the presence of a highly porous network with a large surface area. Bead size distribution and shapes are in accordance with the product specifications (see SI).

Fig. 1.

SEM analysis of EziG3 (Fe-Amber) with immobilized AsR-ωTA: A) bead distribution at 150 x magnification; B) single bead at 5000 x magnification; C) surface morphology at 35 000 x magnification.

3.3. Immobilization of ω-transaminases

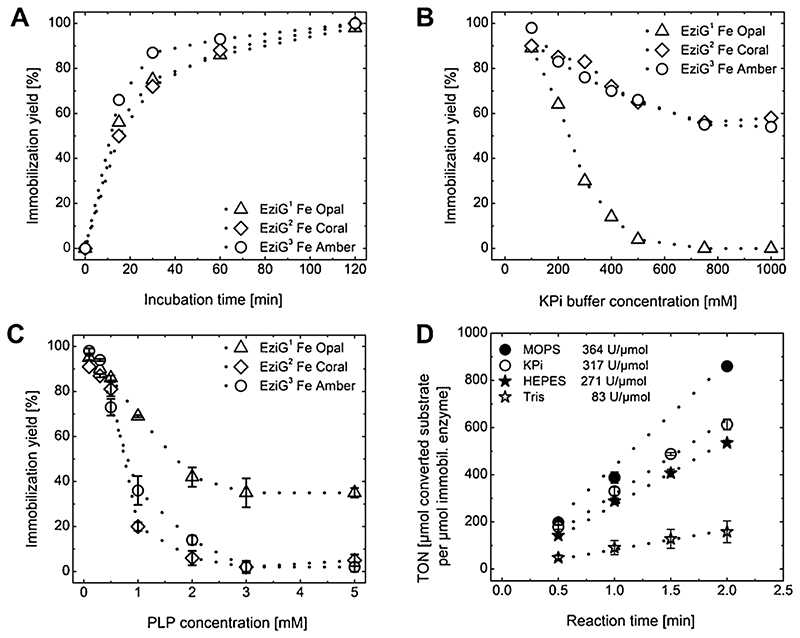

Immobilization of ω-transaminases AsR-ωTA and Cv-ωTA was performed by incubating the desired amount of enzyme in buffer supplied with EziG carrier material. The progress of immobilization was monitored in time by using a Bradford assay to measure the amount of enzyme remaining in the immobilization buffer (see SI, section 6 for details). The progress of the immobilization was evinced visually in that the EziG carrier material turned increasingly yellow during incubation due to the presence of the (yellow) PLP cofactor bound in the active site of the enzyme. AsR-ωTA was immobilized under standard immobilization conditions on EziG carrier materials within 2 h of incubation (Fig. 2A and Table S3). Affinity binding of AsR-ωTA on the three EziG carrier materials, namely EziG1-AsR, EziG2-AsR, and EziG3-AsR depending on the carrier type, proved to be strong, as there was no detectable loss of enzyme from the carrier material even after incubating the immobilized enzyme in buffer up to 3 days. Longer incubation times were not tested.

Fig. 2.

Immobilization studies of AsR-ωTA on EziG carrier materials (EziG1-AsR = triangle, EziG2-AsR = diamond, EziG3-AsR = circle). (A) Immobilization on EziG carrier materials monitored in time. Immobilization yield (in %) was determined using Bradford assay (see SI section 6.2). (B) Immobilization of AsR-ωTA on EziG carrier materials in KPi buffer with increasing KPi buffer concentration. Immobilization conditions: EziG carrier material (10 mg, 10% enzyme loading, w w-1); KPi (100-1000 mM, pH 8, 1 mL); PLP (0.1 mM); AsR-ωTA (1 mg, 27 nmol); 4 °C, 120 rpm (orbital shaker); 2 h. (C) Immobilization of AsR-ωTA on EziG carrier materials with additional PLP. Error bars display absolute difference between two individual experiments. Immobilization conditions: EziG carrier material (10 mg, 10% enzyme loading, w w-1), KPi (100 mM, pH 8, 1 mL), PLP (0.1-5 mM), AsR-ωTA (1 mg, 27 nmol), 4 °C, 120 rpm (orbital shaker), 2 h. (D) Immobilization of AsR-ωTA on EziG3 Fe-Amber (10% enzyme loading, w w-1) using different immobilization buffers (100 mM MOPS pH 8 = black circle; 100 mM KPi pH 8 = white circle; 100 mM HEPES pH 8 = black star; 100 mM Tris pH 8 = white star). Activity testing in kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA. Error bars display standard deviation over three experiments. Reaction conditions: Immobilized EziG3-AsR (10 mg, 10% enzyme loading, w w-1); rac-α-MBA (100 mM); sodium pyruvate (50 mM); DMSO (5%, v v-1); PLP (25 pM); HEPES buffer (0.5 mL reaction volume, 250 mM, pH 7); 30 °C, thermomixer (750 rpm).

3.4. Influence of buffer concentration (i.e., related ionic strength) and PLP concentration on the immobilization process

The ionic strength of the immobilization buffer greatly influences the immobilization efficiency of many carrier materials. For example, researchers have reported improvements in covalent coupling of enzymes to epoxy-activated carriers by using high ionic buffer strength. In a first step, a salt-induced association takes place between the macromolecule and the support surface (Mateo et al., 2002; Wheatley and Schmidt, 1999), which increases the effective concentration of nucleophilic groups on the protein close to the epoxide reactive sites. However, the salt concentration needed to immobilize an enzyme was reported to be highly protein-dependent (Wheatley and Schmidt, 1999). Hence, we wondered about the influence of buffer concentration in the case of metal-ion affinity immobilization with EziG carriers. Immobilization tests of ωTAs on EziG carriers were performed in KPi buffer (pH 8) with a buffer concentration ranging from 100 mM to 1 M. Fig. 2B shows that buffer concentrations above 100 mM had a negative influence on the immobilization process; however, the behavior of the immobilization yield of AsR-ωTA versus the buffer concentration depended on the type of EziG carrier. The effect on EziG1 (Fe-Opal) was dramatic, with virtual no immobilization above a concentration of 600 mM KPi. Conversely, EziG2 (Fe-Coral) and EziG3 (Fe-Amber) behaved similarly to each other, resulting in a residual 60% immobilization yield at 1 M KPi (Fig. 2B and Table S4). Thus, the immobilization process is somewhat dependent on the physico-chemical properties of the surface of the carrier material, albeit the type of immobilization is the same (i.e., Fe-cation affinity to enzyme His6-tag). We also speculated that phosphate ions might compete with the enzyme for the binding to the Fe-cations that are chelated to the EziG carrier material. Interestingly, although the stability of free AsR-ωTA in solution at high ionic strength was not tested in a specifically designed experiment, no precipitation of enzyme was observed during the immobilization procedure even at 1 M KPi buffer.

PLP plays an important role not only as a cofactor, but also in contributing to the stabilization of the catalytically active dimeric form of the enzyme, whereas the monomeric form is inactive (Chen et al., 2016; Lyskowski et al., 2014; Malik et al., 2012). In order to maintain the dimeric active form of the enzyme, an excess of PLP is commonly supplied during biotransformations with non-immobilized ωTA (5–10 eq. of PLP to the enzyme) (Slabu et al., 2017). During our preliminary experiments, AsR-ωTA and Cv-ωTA were immobilized in solution, as active biocatalysts in the presence of externally added PLP. However, we hypothesized that the concentration of PLP could have a dual impact, such that although adding a surplus of PLP during the immobilization procedure might be beneficial for retaining the activity of ωTAs, high concentrations of PLP might also hamper the immobilization process, as the PLP could also interact with the metal cationic centers of the EziG carrier. Accordingly, EziG carrier materials were separately incubated in 100 mM KPi buffers at varied concentrations of PLP (0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7,1, 2, 3, and 5 mM) for 30 min prior to addition of the enzyme. Fig. 2C shows the dramatic negative effect related to the use of an excess of PLP. Among the three tested EziG carriers, EziG1 was the most affected by higher buffer concentration (Fig. 2B) and the least affected by higher PLP concentration (Fig. 2C). As a general conclusion, for obtaining high immobilization yields, the PLP had to be kept below 0.1 mM (Fig. 2C and Table S5). Precipitation of enzyme was not observed in any of the experiments. Among the three tested EziG carriers, EziG3 (Fe-Amber) provided the optimal immobilization yield when using 100 mM KPi buffer supplemented with 0.1 mM PLP. Therefore, EziG3 was selected for the biocatalytic studies.

3.5. Influence of type of buffer and pH on the immobilization process

Both the buffer type and its pH value determine the nature of the ionogenic environment around the enzyme. Consequently, the immobilization buffer can significantly influence the stability and activity of the immobilized enzyme. EziG3-AsR was immobilized as previously described in four different types of buffers at 100 mM concentration (MOPS pH 8.0, KPi pH 8.0, HEPES pH 8.0 and Tris pH 8.0), and the resulting biocatalyst activity was determined for the kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA with 0.5 equiv. of pyruvate (Scheme 1). Immobilization in MOPS buffer resulted in the highest observed activity of 365 U (Fig. 2D and Table S6). Conversely, a more than four-fold decrease in activity was observed using EziG3-AsR originated from the immobilization in Tris buffer (83 U ). Interestingly, immobilizations in MOPS buffer at pH 6.5, 7 or 7.5 did not significantly affect the initial catalytic activity (379 U , 323 U and 365 U , respectively; for details; see Table S7). However, immobilization in MOPS buffer at pH 6 showed a significant drop in activity to 192 U . Lower pH values were not tested due to the reported instability of AsR-ωTA below pH 6 (Iwasaki et al., 2012).

3.6. Studies on single batch kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA catalyzed by ωTAs immobilized on EziG3

3.6.1. Preliminary considerations on immobilization and reaction temperatures

A preliminary study using AsR-ωTA as free enzyme in solution displayed slightly lower enzyme activity at 40 °C and significantly decreased enzyme activity at 50 °C (Figure S2 and Table S11). On the other hand, both EziG3-AsR (i.e., immobilized enzyme) and AsR-ωTA (i.e., isolated enzyme) evinced no detectable loss of activity upon incubation for 3 days at RT. Accordingly, we decided to perform all of the biotransformations at 30 °C.

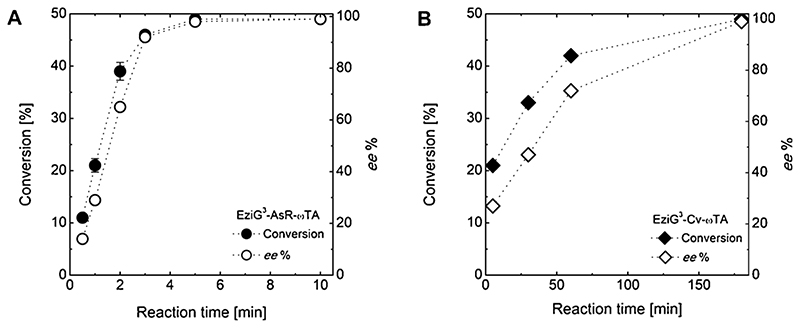

3.6.2. Initial tests for activity of immobilized aTAs

AsR-ωTA and Cv-ωTA immobilized on EziG3 Fe-Amber, namely EziG3-AsR and EziG3-Cv, respectively, were employed in preliminary experiments for the kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA (100 mM) with 0.5 eq. of pyruvate (Scheme 1). EziG3-AsR (10 mg, 10% enzyme loading, w w−1) showed high activity for the substrate, and perfect kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA was reached within 5 min (> 49% conversion and > 99% ee of unreacted (S)-α-MBA; Fig. 3 A and Table S7) with a calculated TON above 900 for this single batch reaction (see SI section 3 for details on calculations and terminology). A similar reaction conducted with the same amount of purified AsR-ωTA in solution required 2 min in order to reach full kinetic resolution (Table S8). EziG3-Cv (10 mg, 10% enzyme loading, w w−1) catalyzed perfect resolution of rac-α-MBA (> 49% conversion and > 99% ee of unreacted (R)-α-MBA; Fig. 3 B and Table S9) within 3 h reaction time with a TON above 1300. We attribute the lower reaction rate of EziG3-Cv compared with EziG3-AsR to a lower intrinsic catalytic activity of Cv-ωTA for (S)-α-MBA and the lower molar loading of the enzyme (i.e., MW AsR-ωTA = 37.2 KDa; MW Cv-ωTA = 53.6 KDa). In fact, the similar reaction with the same amount of purified Cv-ωTA in solution also required at least 2 h for complete kinetic resolution of rac-α0-MBA (Table S10). Comparing the preliminary experiments of kinetic resolution using either free enzyme in solution or immobilized enzyme, we noticed that the apparent rate of the reaction is moderately higher when using the former. This phenomenon must not be attributed to a lower intrinsic catalytic activity of the immobilized biocatalysts. In fact, when operating with immobilized enzymes in an aqueous environment, reagents and biocatalyst are in different phases (i.e., heterogeneous catalysis), and therefore mass transfer (i.e., external as well as inside the pores of the carrier) influences the overall kinetics of the process. This is particularly valid for the kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA, which has an elevated reaction rate in homogeneous aqueous systems (Shin and Kim, 1998). Accordingly, the preliminary experiments must be simply interpreted as a proof of highly retained catalytic activity of the ω-transaminases upon immobilization. These conclusions correlate with the experiments at high substrate loading reported in the next section.

Fig. 3.

(A) Time study of EziG3-AsR (left graph, circles) and B) EziG3-Cv (right graph, diamonds) in kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA. Primary axis displays conversion to acetophenone (black shapes) and secondary axis displays ee% of remaining (S)-α-MBA (white shapes). Error bars indicate standard deviation over three experiments. Reaction conditions: EziG3-AsR or EziG3-Cv (10 mg, 10% enzyme loading, w w-1); rac-α-MBA (100 mM); sodium pyruvate (50 mM); DMSO (5%, v v-1); PLP (25 pM); HEPES buffer (0.5 mL reaction volume, 250 mM, pH 7); 30 °C, thermomixer (750 rpm).

3.6.3. High substrate loading performance of EziG3-AsR

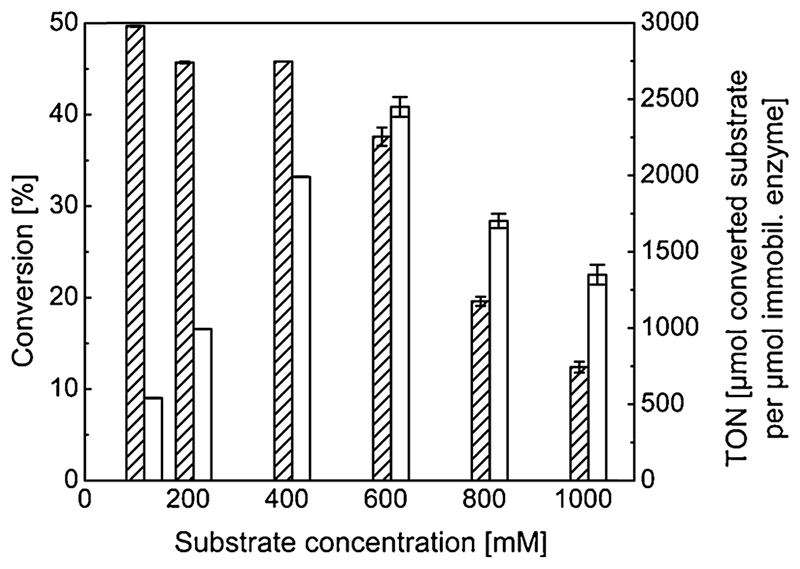

Substrate feed is often a limiting factor for implementation of biocatalysts in large scale processes. As immobilized EziG3-AsR biocatalyst proved to be highly active in preliminary experiments, we performed kinetic resolution at higher concentrations of substrate (Fig. 4 and Table S13; see SI for experimental details). The resolution of rac-α-MBA was observed with increasing productivity up to 600 mM substrate concentration (TON = 2450 for a single batch reaction). Substrate and co-product inhibition are common limitations in ω-transaminase-cata-lyzed reactions, which explains the observed drop in conversion at substrate concentration values above 600 mM (Gomm and O’Reilly, 2018).

Fig. 4.

Activity of EziG3-AsR in kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA when applying higher substrate loadings. Conversion to acetophenone (striped bars) and TON (white bars) for the reaction catalyzed by the immobilized enzyme. Error bars display standard deviation over three experiments. Reaction conditions: EziG3-AsR (10mg, 17% enzyme loading, w w-1); rac-α-MBA (concentration varied); sodium pyruvate (0.5 equiv.); DMSO (10%, v v-1); PLP (25 pM); HEPES buffer (0.5 mL reaction volume, 250mM, pH 7); 30 °C, thermomixer (750 rpm); 15 min.

3.7. Biocatalyst recycling

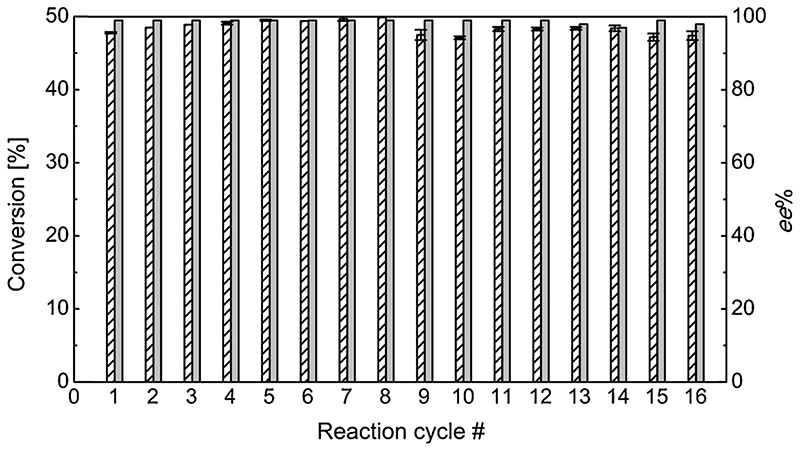

The main advantage related to enzyme immobilization is the potential for recycling the biocatalysts for subsequent batch reactions. An amount of EziG3-AsR (10 mg, 10% enzyme loading, w w−1) was repeatedly employed for the kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA (initial concentration per cycle 100 mM) with sodium pyruvate (50 mM). Each cycle of batch reaction was run for 15 min. At the end of each cycle, the reaction buffer was separated from the biocatalyst and worked-up. Then, the same batch of EziG3-AsR biocatalyst was re-suspended in fresh buffer containing the reagents and additional PLP (25 µM), and another reaction cycle was initiated. This procedure was repeated for 16 reaction cycles, maintaining quantitative conversion in the kinetic resolution using the immobilized enzyme (Fig. 5 and Table S14). Considering the short reaction time per cycle employed (15 min), this experiment demonstrated the robustness of the reaction system. In total, 388 µM (S)-α-MBA (> 99% ee) was produced with a total TON of 14,400. Interestingly, when no additional PLP (25 µM) was supplied in each cycle, conversions dropped slightly (approximately 3% per cycle), thus indicating that the specific minimal addition of PLP is beneficial for retaining long-term catalytic activity (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Recycling EziG3-AsR in kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA. Conversion to acetophenone (striped bars) and ee % (grey bars) of the remaining (S)-α-MBA. Error bars display standard deviation over three experiments. Reaction conditions: EziG3-AsR (10 mg, 10% enzyme loading, w w-1); HEPES buffer (0.5 mL reaction volume, 250 mM, pH 7); PLP (25 µM); sodium pyruvate (50 mM), rac-α-MBA (100 mM); DMSO (10%, v v-1); 30 °C; thermomixer (750 rpm); 15 min per reaction cycle (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

3.8. In-flow immobilization and continuous flow kinetic resolution

Chemical synthesis using immobilized biocatalysts in continuous flow systems is particularly attractive in terms of practicality, reproducibility and improved productivity compared to batch reaction systems. In this context, in-flow immobilization of AsR-ωTA (15 mg) was performed in a stainless-steel column (50 mm length x 2 mm diameter) filled with EziG3 Fe-Amber beads (100 mg; see “Material and methods” (Section 2.6) for details). The flow reactor (total volume 157 µL) was then applied in continuous flow for the kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA (10.9 g, 100 mM) with sodium pyruvate (0.55 equiv.; Scheme 2). The reaction buffer mixture was pumped through the column at an average rate of 0.175 mL min-1 (average space time = 54 s) using a Dionex P680 HPLC pump unit. The flow-through was collected in separate 100-200 mL fractions and analytical samples were analyzed by GC. The packed-bed flow reactor was operated for 96 consecutive hours without any detectable loss of catalytic performance, and the kinetic resolution proceeded with perfect enantioselectivity (> 49% conversion, > 99% ee of unreacted (S)-α-MBE). The calculated TON was above 110,000 and the space-time yield was 335 g L-1 h-1. After work-up, 5.05 g (42 mmol) of (S)-α-MBA were obtained in high chemical and optical purity (93% isolated yield, > 99% ee; see SI).

Scheme 2.

Flow reactor set-up in application of EziG3-AsR for kinetic resolution of rac-α-MBA.

4. Conclusion

In this study, we implemented ω-transaminases as highly active heterogeneous biocatalysts in the production of an α-chiral amine by kinetic resolution. Our investigation into the immobilization conditions proved critical for obtaining highly active biocatalysts. The optimal conditions for immobilization on EziG carrier were found to be the use of 100 mM MOPS buffer supplemented with 0.1 mM PLP. The fundamental design of EziG allowed us to reach high loading of enzyme per mass unit of carrier material (20%, w w−1). Under the optimized conditions, the immobilized enzyme was recycled for 16 consecutive batch reactions (15 min reaction time per batch), always affording quantitative conversion. Finally, multi-gram scale continuous flow production of (S)-α-MBA was performed in a packed-bed flow reactor for 96 consecutive hours without any detectable loss of enzymatic activity. Within the short timeframe of our experiment, the chemical turnover number reached a value higher than 110,000 and a space-time yield of 335 g L-1 h-1. It is noteworthy that erosion of the exquisite enantioselectivity of the immobilized ωTA was never observed during operation in either batch- or continuous flow biocatalysis. This research highlights the potential of continuous flow biocatalysis, by selective immobilization of enzymes onto functionalized controlled-pore glass beads through reversible metal-cation affinity binding, for industrial manufacturing of high value chemicals.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2018.12.001.

Acknowledgements

This project received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (Grant Agreement No. 638271, BioSusAmin). Dutch funding from the NWO Sector Plan for Physics and Chemistry is also acknowledged.

Footnotes

Competing interest

A.V. and K.E.C. are affiliated to EnginZyme AB, the company that manufactures and commercializes the immobilization carrier material used in this study. The other authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Declaration of interests

None.

References

- Abaházi E, Sátorhelyi P, Erdélyi B, Vértessy BG, Land H, Paizs C, Berglund P, Poppe L. Covalently immobilized Trp60Cys mutant of ω-transaminase from Chromobacterium violaceum for kinetic resolution of racemic amines in batch and continuous-flow modes. Biochem Eng J. 2018;132:270–278. [Google Scholar]

- Alami AT, Richina F, Correro MR, Dudal Y, Shahgaldian P. Surface im-mobilization and shielding of a transaminase enzyme for the stereoselective synthesis of pharmaceutically relevant building blocks. Chimia (Aarau) 2018;72:345–346. doi: 10.2533/chimia.2017.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann M, Mugge C, Gassmeyer SK, Enoki J, Hilterhaus L, Kourist R, Liese A, Kara S. Improvement of the process stability of arylmalonate decarboxylase by immobilization for biocatalytic profen synthesis. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:448. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajić M, Plazl I, Stloukal R, Znidarsic-Plazl P. Development of a miniaturized packed bed reactor with ω -transaminase immobilized in LentiKats ®. Process Biochem. 2017;52:63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Basso A, Neto W, Serban S, Summers BD. How to optimise the immobilization of amino transaminases on synthetic enzyme carriers, to achieve up to a 13-fold increase in performances. Chim Oggi-Chem Today. 2018;36:40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Benitez-Mateos AI, Contente ML, Velasco-Lozano S, Paradisi F, Lopez-Gallego F. Self-sufficient flow-biocatalysis by coimmobilization of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate and ω-transaminases onto porous carriers. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2018;6:13151–13159. [Google Scholar]

- Böhmer W, Knaus T, Mutti FG. Hydrogen-borrowing alcohol bioamination with coimmobilized dehydrogenases. ChemCatChem. 2018;10:731–735. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201701366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton J, Majumdar S, Weiss GA. Continuous flow biocatalysis. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47:5891–5918. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00906b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G, Gao J, Zhou L, Huang Z, He Y, Zhu M, Jiang Y. Fabrication of Ni 2+ -nitrilotriacetic acid functionalized magnetic mesoporous silica nanoflowers for one pot purification and immobilization of His-tagged ω-transaminase. Biochem Eng J. 2017;128:116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas-Fernandez M, Neto W, Lopez C, Alvaro G, Tufvesson P, Woodley JM. Immobilization of Escherichia coli containing omega-transaminase activity in LentiKats(R) Biotechnol Prog. 2012;28:693–698. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassimjee KE, Federsel HJ. CHAPTER 13: EziG: a universal platform for enzyme immobilisation. RSC Catalysis Series. 2018:345–362. [Google Scholar]

- Cassimjee KE, Hendil-Forssell P, Volkov A, Krog A, Malmo J, Aune TEV, Knecht W, Miskelly IR, Moody TS, Svedendahl Humble M. Streamlined preparation of immobilized Candida aniarciica lipase B. ACS Omega. 2017;2:8674–8677. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.7b01510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Land H, Berglund P, Humble MS. Stabilization of an amine transaminase for biocatalysis. J Mol Catal B: Enzym. 2016;124:20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Choi JM, Han SS, Kim HS. Industrial applications of enzyme biocatalysis: current status and future aspects. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33:1443–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza SP, Junior II, Silva GMA, Miranda LSM, Santiago MF, Leung-Yuk Lam F, Dawood F, Bornscheuer A, de Souza UT, de Souza ROMA. Cellulose as an efficient matrix for lipase and transaminase immobilization. RSC Adv. 2016d;6:6665–6671. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmark Cassimjee K, Kadow M, Wikmark Y, Svedendahl Humble M, Rothstein ML, Rothstein DM, Backvall JE. A general protein purification and immobilization method on controlled porosity glass: biocatalytic applications. Chem Commun. 2014;50:9134–9137. doi: 10.1039/c4cc02605e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmark Cassimjee K, Bäckvall JE. Immobilized Proteins and Use Thereof. EnginZyme AB. 2015 WO2015/115993. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lafuente R, Armisén P, Sabuquillo P, Fernández-Lorente G, Guisán JM. Immobilization of lipases by selective adsorption on hydrophobic supports. Chem Phys Lipids. 1998;93:185–197. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(98)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lafuente R, Rosell CM, Caanan-Haden L, Rodes L, Guisan JM. Facile synthesis of artificial enzyme nano-environments via solid-phase chemistry of immobilized derivatives: dramatic stabilization of penicillin acylase versus organic solvents. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1999;24:96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lopez L, Pedrero SG, Lopez-Carrobles N, Gorines BC, Virgen-Ortiz JJ, Fernandez-Lafuente R. Effect of protein load on stability of immobilized enzymes. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2017;98:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomm A, O’Reilly E. Transaminases for chiral amine synthesis. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2018;43:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho LF, Li SY, Lin SC, Wen-Hwei H. Integrated enzyme purification and immobilization processes with immobilized metal affinity adsorbents. Process Biochem. 2004;39:1573–1581. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki A, Matsumoto K, Hasegawa J, Yasohara Y. Anovel transaminase, (R)-amine:pyruvate aminotransferase, from Arthrobacter sp. KNK168 (FERM BP-5228): purification, characterization, and gene cloning Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93:1563–1573. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3580-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H, Huang F, Gao Z, Zhong C, Zhou H, Jiang M, Wei P. Immobilization of omega-transaminase by magnetic PVA-Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Biotechnol Rep. 2016;10:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaulmann U, Smithies K, Smith MEB, Hailes HC, Ward JM. Substrate spectrum of ω-transaminase from Chromobacterium violaceum DSM30191 and its potential for biocatalysis. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2007;41:628–637. [Google Scholar]

- Knaus T, Mutti FG. Biocatalytic hydrogen-borrowing cascades. Chim Oggi-Chem Today. 2017;35:34–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koszelewski D, Pressnitz D, Clay D, Kroutil W. Deracemization of mexiletine biocatalyzed by omega-transaminases. Org Lett. 2009;11:4810–4812. doi: 10.1021/ol901834x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koszelewski D, Goritzer M, Clay D, Seisser B, Kroutil W. Synthesis of optically active amines employing recombinant omega-transaminases in E. coli cells ChemCatChem. 2010;2:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lechner H, Soriano P, Poschner R, Hailes HC, Ward JM, Kroutil W. Library of norcoclaurine synthases and their immobilization for biocatalytic transformations. Biotechnol J. 2018;13 doi: 10.1002/biot.201700542. 1700542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Q, Du X, Jiang W, Tong Y, Zhao Z, Fang R, Feng J, Tang L. Cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) of halohydrin dehalogenase from Agrobacterium radiobacter AD1: preparation, characterization and application as a biocatalyst. J Biotechnol. 2018;272-273:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Serrano P, Cao L, van Rantwijk F, Sheldon RA. Cross-linked enzyme aggregates with enhanced activity: application to lipases. Biotechnol Lett. 2002;24:1379–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Lyskowski A, Gruber C, Steinkellner G, Schurmann M, Schwab H, Gruber K, Steiner K. Crystal structure of an (R)-selective omega-transaminase from Aspergillus terreus. PloS One. 2014;9:e87350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan A, Sindhu R, Binod P, Sukumaran RK, Pandey A. Strategies for design of improved biocatalysts for industrial applications. Bioresour Technol. 2017;245(Part B):1304–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik MS, Park ES, Shin JS. Features and technical applications of omega-transaminases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;94:1163–1171. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallin H, Hohne M, Bornscheuer UT. Immobilization of (R)- and (S)-amine transaminases on chitosan support and their application for amine synthesis using isopropylamine as donor. J Biotechnol. 2014;191:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo C, Abian O, Fernandez-Lorente G, Pedroche J, Fernandez-Lafuente R, Guisan JM, Tam A, Daminati M. Epoxy sepabeads: a novel epoxy support for stabilization of industrial enzymes via very intense multipoint covalent attachment. Biotechnol Prog. 2002;18:629–634. doi: 10.1021/bp010171n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo C, Monti R, Pessela BC, Fuentes M, Torres R, Guisan JM, Fernandez-Lafuente R. Immobilization of lactase from Kluyveromyces lactis greatly reduces the inhibition promoted by glucose full hydrolysis of lactose in milk. Biotechnol Prog. 2004;20:1259–1262. doi: 10.1021/bp049957m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo C, Palomo JM, Fernandez-Lorente G, Guisan JM, Fernandez-Lafuente R. Improvement of enzyme activity, stability and selectivity via immobilization techniques. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2007;40:1451–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Mingarro I, Abad C, Braco L. Interfacial activation-based molecular bioimprinting of lipolytic enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3308–3312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutti FG, Fuchs CS, Pressnitz D, Sattler JH, Kroutil W. Stereoselectivity of four (R)-selective transaminases for the asymmetric amination of ketones. Adv Synth Catal. 2011;353:3227–3233. [Google Scholar]

- Mutti FG, Knaus T, Scrutton NS, Breuer M, Turner NJ. Conversion of alcohols to enantiopure amines through dual-enzyme hydrogen-borrowing cascades. Science. 2015;349:1525–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto W, Schurmann M, Panella L, Vogel A, Woodley JM. Immobilisation of ω-transaminase for industrial application: screening and characterisation of com-mercial ready to use enzyme carriers. J Mol Catal B: Enzym. 2015;117:54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo JM, Fernandez-Lorente G, Mateo C, Fuentes M, Fernandez-Lafuente R, Guisan JM. Modulation of the enantioselectivity of Candida antarctica B lipase via conformational engineering. Kinetic resolution of (±)-α-hydroxy-pheny-lacetic acid derivatives Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2002a;13:1337–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo JM, Fernandez-Lorente G, Mateo C, Ortiz C, Fernandez-Lafuente R, Guisan JM. Modulation of the enantioselectivity of lipases via controlled immobilization and medium engineering: hydrolytic resolution of mandelic acid esters. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2002b;31:775–783. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo JM, Segura RL, Fernandez-Lorente G, Guisán JM, Fernandez-Lafuente R. Enzymatic resolution of (±)-glycidyl butyrate in aqueous media. Strong modulation of the properties of the lipase from Rhizopus oryzae via immobilization techniques Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2004;15:1157–1161. [Google Scholar]

- Pessela BCC, Mateo C, Filho M, Carrascosa A, Fernández-Lafuente R, Guisan JM. Selective adsorption of large proteins on highly activated IMAC supports in the presence of high imidazole concentrations: purification, reversible immobilization and stabilization of thermophilic α- and β-galactosidases. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2007;40:242–248. [Google Scholar]

- Porath J. Immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography. Protein Expres Purif. 1992;3:263–281. doi: 10.1016/1046-5928(92)90001-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad S, Roy I. Converting enzymes into tools of industrial importance. Recent Pat Biotechnol. 2018;12:33–56. doi: 10.2174/1872208311666170612113303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reetz MT. Entrapment of biocatalysts in hydrophobic sol-gel materials for use in organic chemistry. Adv Mater. 1997;9:943–954. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues RC, Ortiz C, Berenguer-Murcia A, Torres R, Fernandez-Lafuente R. Modifying enzyme activity and selectivity by immobilization. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:6290–6307. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35231a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos JCS, Barbosa O, Ortiz C, Berenguer-Murcia A, Rodrigues RC, Fernandez-Lafuente R. Importance of the support properties for immobilization or purification of enzymes. ChemCatChem. 2015;7:2413–2432. [Google Scholar]

- Savile CK, Janey JM, Mundorff EC, Moore JC, Tam S, Jarvis WR, Colbeck JC, Krebber A, Fleitz FJ, Brands J, Devine PN, Huisman GW, Hughes GJ. Biocatalytic asymmetric synthesis of chiral amines from ketones applied to sitagliptin manufacture. Science. 2010;329:305–309. doi: 10.1126/science.1188934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid A, Dordick JS, Hauer B, Kiener A, Wubbolts M, Witholt B. Industrial biocatalysis today and tomorrow. Nature. 2001;409:258–268. doi: 10.1038/35051736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon RA. Enzyme immobilization: the quest for optimum performance. Adv Synth Catal. 2007;349:1289–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon RA, van Pelt S. Enzyme immobilisation in biocatalysis: why, what and how. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:6223–6235. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60075k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon RA, Woodley JM. Role of biocatalysis in sustainable chemistry. Chem Rev. 2018;118:801–838. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon RA, van Pelt S, Kanbak-Aksu S, Rasmussen JA, Janssen MHA. Cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) in organic synthesis. Aldrichimica Acta. 2013;46:81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Shin JS, Kim BG. Kinetic modeling of omega-transamination for enzymatic kinetic resolution of alpha-methylbenzylamine. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1998;60:534–540. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19981205)60:5<534::aid-bit3>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JS, Yun H, Jang JW, Park I, Kim BG. Purification, characterization, and molecular cloning of a novel amine:pyruvate transaminase from Vibrio fluvialis JS17. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;61:463–471. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva C, Martins M, Jing S, Fu J, Cavaco-Paulo A. Practical insights on enzyme stabilization. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2018;38:335–350. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2017.1355294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slabu I, Galman JL, Lloyd RC, Turner NJ. Discovery, engineering, and synthetic application of transaminase biocatalysts. ACS Catal. 2017;7:8263–8284. [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Cui WH, Du K, Gao Q, Du M, Ji P, Feng W. Immobilization of R-omega-transaminase on MnO2 nanorods for catalyzing the conversion of (R)-1-phenylethylamine. J Biotechnol. 2017;245:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Turner NJ. Two-enzyme hydrogen-borrowing amination of alcohols enabled by a cofactor-switched alcohol dehydrogenase. ChemCatChem. 2017;9:3833–3836. [Google Scholar]

- Truppo MD, Strotman H, Hughes G. Development of an immobilized transaminase capable of operating in organic solvent. ChemCatChem. 2012;4:1071–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Zheng D, Yin L, Wang F. Preparation, activity and structure of cross¬linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) with nanoparticle. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2017;107:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley JB, Schmidt DE., Jr Salt-induced immobilization of affinity ligands onto epoxide-activated supports. J Chromatogr A. 1999;849:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(99)00484-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson L, Illanes A, Abian O, Pessela BC, Fernandez-Lafuente R, Guisan JM. Co-aggregation of penicillin g acylase and polyionic polymers: an easy methodology to prepare enzyme biocatalysts stable in organic media. Biomacromolecules. 2004a;5:852–857. doi: 10.1021/bm0343895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson L, Illanes A, Pessela BC, Abian O, Fernandez-Lafuente R, Guisan JM. Encapsulation of crosslinked penicillin G acylase aggregates in lentikats: evaluation of a novel biocatalyst in organic media. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004b;86:558–562. doi: 10.1002/bit.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdarta J, Meyer A, Jesionowski T, Pinelo M. A General overview of support materials for enzyme immobilization: characteristics, properties, practical utility. Catalysts. 2018;8:92. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.