Transcription factors (TFs) are core components of the signaling pathway and play an important role in transcriptional regulation of gene expression during fungal morphogenesis processes. A prevailing theory suggests an interplay between different TFs regulating microsclerotial differentiation; however, the persisting issue remains that these interplay mechanisms are not clear. Here, we analyzed two members of the APSES-type TFs in Metarhizium rileyi using a gene deletion strategy and transcriptome analysis. Mutants were significantly impaired in microsclerotium formation and dimorphic transition. Transcriptome analysis provided evidence for interacting regulatory mechanisms by the two TFs in microsclerotium formation and dimorphic transition. Furthermore, we investigated their overlapping roles in mediating the expression of genes required for different fungal morphogenesis processes. Characterization of TFs in this study will aid in dissecting the interplay between regulatory mechanisms in fungal morphogenesis processes.

KEYWORDS: Metarhizium rileyi, microsclerotium, morphogenesis, APSES-type transcriptional factors

ABSTRACT

APSES-type transcription factors (TFs) have analogous and diverse functions in the regulation of fungal morphogenesis processes. However, little is known about these functions in microsclerotium formation. In this study, we characterized two orthologous APSES genes (MrStuA and MrXbp) in the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium rileyi. Deletion of either MrStuA or MrXbp impaired dimorphic transition, conidiation, fungal virulence, and microsclerotium formation. Compared with the wild-type strain, ΔMrStuA and ΔMrXbp mutants were hypersensitive to thermal and oxidative stress. Furthermore, transcriptome sequencing analysis revealed that MrStuA and MrXbp independently regulate their own distinctive subsets of signaling pathways during dimorphic transition and microsclerotium formation, but they also show an overlapping regulation of genes during these two distinct morphogenesis processes. These results provide a global insight into vital roles of MrStuA and MrXbp in M. rileyi and aid in dissection of the interacting regulatory mechanisms of dimorphism transition and microsclerotium development.

IMPORTANCE Transcription factors (TFs) are core components of the signaling pathway and play an important role in transcriptional regulation of gene expression during fungal morphogenesis processes. A prevailing theory suggests an interplay between different TFs regulating microsclerotial differentiation; however, the persisting issue remains that these interplay mechanisms are not clear. Here, we analyzed two members of the APSES-type TFs in Metarhizium rileyi using a gene deletion strategy and transcriptome analysis. Mutants were significantly impaired in microsclerotium formation and dimorphic transition. Transcriptome analysis provided evidence for interacting regulatory mechanisms by the two TFs in microsclerotium formation and dimorphic transition. Furthermore, we investigated their overlapping roles in mediating the expression of genes required for different fungal morphogenesis processes. Characterization of TFs in this study will aid in dissecting the interplay between regulatory mechanisms in fungal morphogenesis processes.

INTRODUCTION

Entomopathogenic fungi have been developed into many mycopesticides for the biological control of insect pests (1). Metarhizium rileyi (previously named Nomuraea rileyi) is a well-known dimorphic entomopathogenic fungus possessing a special dimorphic lifestyle with yeast-like hyphal bodies (referred to as yeast-like cells here) and a true filamentous growth phase in vivo and in vitro (2). Both the production of conidia, generally responsible for initiating infection on the cuticle of insect pests, and the development of microsclerotium, an alternative fungal propagule for mycoinsectide, involve several morphological processes in M. rileyi (3, 4). Fungal morphogenesis is quite flexible in its adaptation to highly divergent metabolic and environmental changes (5, 6). A complex of signaling pathways has been confirmed, involving several transcription factors (TFs), each one acting singly or in combination to execute morphogenesis (7, 8). APSES-type TFs are fungal TFs with conserved basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) DNA-binding domains, and the first members described were Asm1p in Neurospora crassa, Phd1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Sok2p in S. cerevisiae, Efg1p in Candida albicans, and StuAp in Aspergillus nidulans (9–13), which are involved in the regulation of morphogenesis processes in fungi (14–17).

A similar set of APSES-type TFs exists in yeast and filamentous fungi, which have diverse functions. Phd1p is an activator, while Sok2p is a repressor regulating pseudohyphal growth in S. cerevisiae (18). Efg1p has dual role, whereas its homolog Efh1p is an activator in the regulation of morphogenesis and metabolism in C. albicans (19). Answi4, an APSES-type TF, plays only a weak role in the regulation of conidial color in Aspergillus nidulans; however, StuA regulates multicellular complexity during asexual reproduction (10, 11, 20). Investigations also found that the StuA homolog Mstu1 is indispensable for pathogenicity and that MoSwi6, another APSES-type TF, is required for pathogenicity in Magnaporthe oryzae (21, 22). Moreover, Mstu1 and MoSwi6 share a combining domain (22). These findings suggest that APSES members have analogous biological functions. However, the analogous and diverse roles of APSES-type TFs remain poorly understood in fungi.

Previous investigation revealed that deletion mutants of MrSwi6, an APSES-type TF gene in M. rileyi, show delayed dimorphic transition and reduced conidium and microsclerotium formation (23). Further comparative transcriptome analysis found that the StuA homolog MrStuA was upregulated and that another APSES-type DNA-binding domain gene (named MrXbp) was downregulated during M. rileyi microsclerotium formation (24). These results implied possible analogous and diverse functions of APSES-type TFs in the regulation of microsclerotium development. However, these functions have not been studied clearly.

Here, we investigated the functions of two APSES-type TFs (products of MrStuA and MrXbp) by constructing mutants for analyses of their multiple phenotypes. Different degrees of phenotypic changes highlighted their analogous and diverse roles in regulating dimorphic transition, conidial germination, multistress tolerance, fungal virulence, and conidium and microsclerotium development in M. rileyi. Furthermore, we probed the transcriptional network by which these two APSES-type TFs regulate dimorphic transition and microsclerotium development in M. rileyi.

RESULTS

Bioinformatic analysis.

Orthologs of MrStuA and MrXbp (GenBank accession no. MN180231 and MN180232, respectively) were cloned from a previously prepared comparative transcriptome library (24). Genomic DNA sequences of MrStuA and MrXbp contained 2,113 bp and 1,570 bp and had 2 and 3 introns, respectively. Both MrStuA and MrXbp shared a conserved APSES-type DNA-binding domain. Additionally, MrStuA had a PAP1 superfamily domain (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). The deduced amino acid sequence of MrStuA presented similarities with those of APSES TFs of Metarhizium guizhouense (91% identity) (25) and Metarhizium brunneum (91% identity) (26). The deduced amino acid sequence of MrXbp showed similarities to those of the APSES-type DNA-binding domain protein of Metarhizium robertsii (57.8% identity) (26) and the transcription regulator HTH (55.8% identity) of Metarhizium guizhouense (25). In the phylogeny reconstruction, the protein sequences of MrStuA and MrXbp clustered together with those of other Metarhizium species (Fig. S1B).

To characterize the physiological functions of MrStuA and MrXbp in M. rileyi, gene deletion mutants (ΔMrStuA and ΔMrXbp) and corresponding complementation strains (ΔMrStuA+StuA and ΔMrXbp+Xbp) were generated, as described in the Materials and Methods. All recombinant strains were verified by PCR and quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) screening (27) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Roles of MrStuA and MrXbp in conidial development.

M. rileyi CQNr01 (wild type [WT]) was grown on solid Sabouraud maltose agar fortified with 1% yeast extract (SMAY). Compared with expression levels at culture initiation (day 0), the expression of MrStuA and MrXbp was downregulated at the yeast-like cell period (day 2), hyphal period (day 4), and conidiation initiation (day 6) (Fig. 1A and B). Expression of MrStuA was downregulated (Fig. 1A), but expression of MrXbp was upregulated at the start of conidium maturation (day 8) (Fig. 1B). These results suggested that MrStuA and MrXbp may have analogous roles in the dimorphic transition and diverse roles in conidium maturation.

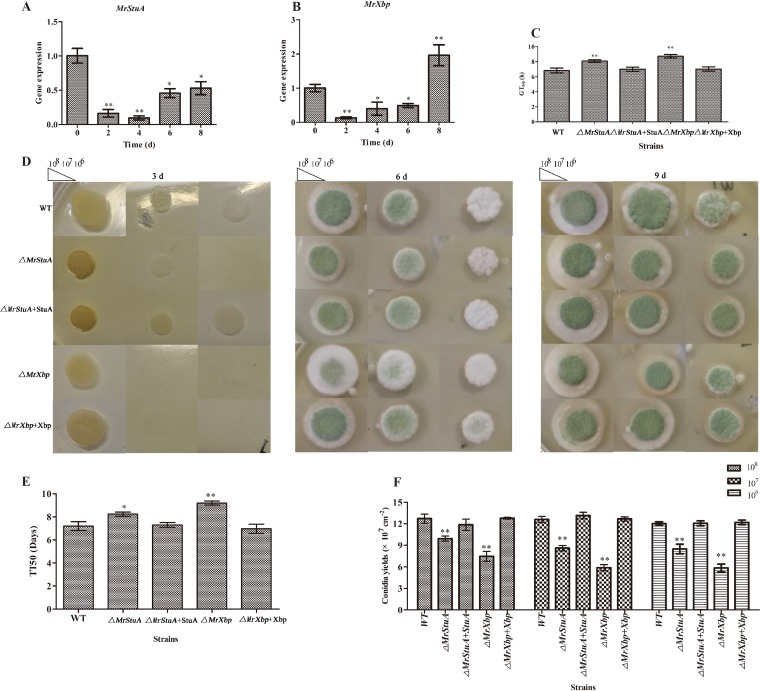

FIG 1.

Function of MrStuA and MrXbp in conidium development. Transcription of MrStuA (A) and MrXbp (B) during conidiation. Conidial suspensions (2.5 μl; 107 conidia ml−1) of the WT strain were spotted onto SMAY plates under continuous light at 25°C for 8 days. (C) GT50 as an index for conidial germination rate. (D) Images of various conidial suspensions spotted onto SMAY plates. (E) TT50 for transition of yeast-like cells to hyphae. TT50 was estimated using a Probit analysis with the SPSS software. (F) Statistical analysis of conidial yield. Error bars represent standard error. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; compared with wild-type strain.

We assessed the median germination time (GT50) for strains to reach 50% germination when incubated on SMAY at 25°C. Compared with the WT, the ΔMrStuA and ΔMrXbp mutants displayed defects in conidial germination (Fig. 1C) (P < 0.01). The GT50 of the ΔMrStuA mutant was 8.1 ± 0.3 h, whereas that of the WT was 6.8 ± 0.5 h, and that of the complementation strain was 7.0 ± 0.5 h (P < 0.01). The GT50 of the ΔMrXbp mutant was 8.7 ± 0.3 h and that of the complementation strain was 7.1 ± 0.4 h (Fig. 1C).

Further incubation on SMAY revealed that the dimorphic transition (day 3) was delayed in the ΔMrStuA and ΔMrXbp mutants, especially in suspensions at 106 conidia ml−1 (Fig. 1D). To further analyze the effect of MrStuA and MrXbp on dimorphic transition, we grew single yeast cells of WT and mutant strains on SMAY medium. These investigations showed that the median transition time required for 50% transition of yeast-like cells to hyphae (TT50) in the ΔMrStuA mutant was 8.1 ± 0.3 days, that in the WT was 7.3 ± 0.1 days, and that in the complementation strain was 7.0 ± 0.1 days (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1E). The TT50 of the ΔMrXbp mutant was 9.2 ± 0.3 days and that of the complementation strain was 7.1 ± 0.3 days (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1E). These finding suggested that deletion of either MrStuA or MrXbp delays dimorphic transition. After 12 days, conidial yield of ΔMrStuA and ΔMrXbp mutants was 26% to 40% lower than that of WT and complemented strains (Fig. 1F). These results suggested that MrStuA and MrXbp have an important role in the regulation of dimorphic transition and conidium production.

Roles of MrStuA and MrXbp in activating signaling pathways during dimorphic transition.

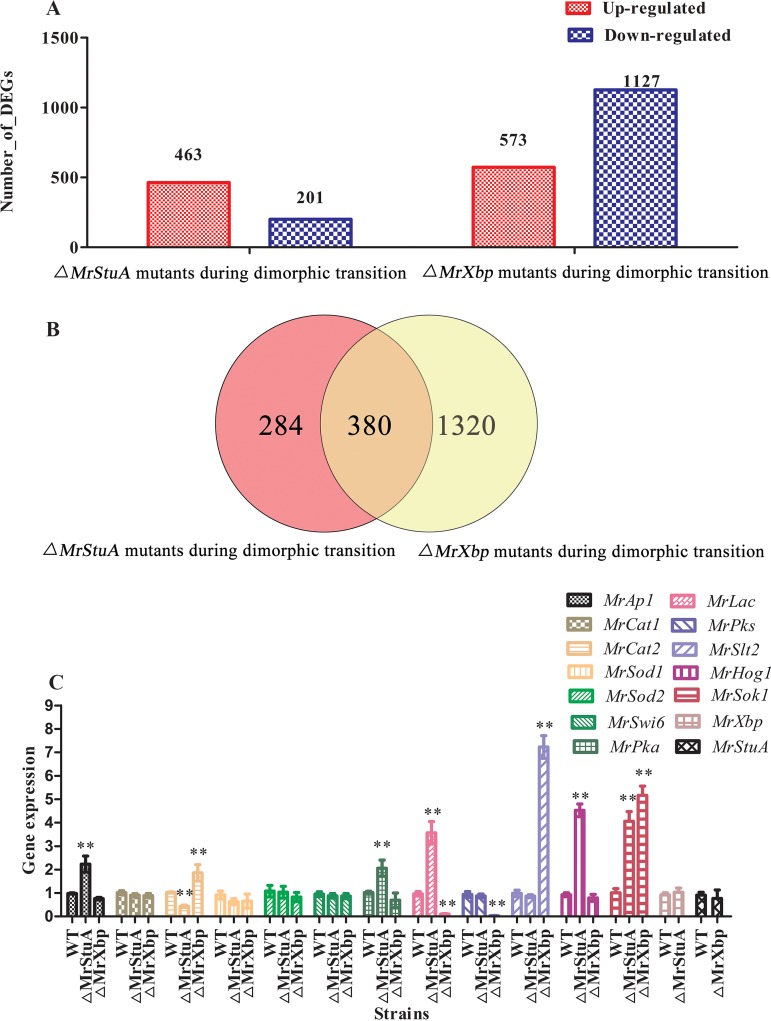

To identify the genes, signaling pathways, and metabolic pathways affected by MrStuA and MrXbp during dimorphic transition, we performed transcriptome sequencing analysis of the WT and ΔMrStuA and ΔMrXbp mutants. Results showed that 463 genes were upregulated and 201 genes were downregulated in the ΔMrStuA mutants, whereas 573 genes were upregulated and 1,127 genes were downregulated in the ΔMrXbp mutants compared with the WT (Fig. 2A). Among these differentially expressed genes (DEGs), 284 genes were regulated only by MrStuA and 1,320 genes were regulated only by MrXbp during dimorphic transition. Moreover, 380 genes were coregulated by MrStuA and MrXbp during dimorphic transition (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

Comparative transcriptomic and RT-qPCR analysis of genes related to dimorphic transition. (A) DEGs in WT versus ΔMrStuA mutants and WT versus ΔMrXbp mutants during dimorphic transition. (B) Venn diagram showing the number of shared DEGs between WT versus ΔMrStuA mutants and WT versus ΔMrXbp mutants during dimorphic transition. (C) RT-qPCR analysis of genes. Error bars represent standard error. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; compared with wild-type strain.

DEGs were functionally grouped into gene ontology (GO) classes comprising 37 functional categories in the ΔMrStuA mutants and 38 functional categories in the ΔMrXbp mutants (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Moreover, we found 20 clusters of orthologous groups (COGs) in the ΔMrStuA mutants and 20 COGs in the ΔMrXbp mutants (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). A total of 91 DEGs in the ΔMrStuA mutants were assigned to 20 Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment pathways. The top three pathways were carbon metabolism (15.3%), biosynthesis of amino acids (14.2%), and oxidative phosphorylation (10.9%) (see Fig. S5A in the supplemental material). In contrast, a total of 279 DEGs in the ΔMrXbp mutants were assigned to 20 KEGG enrichment pathways. The top three pathways were ribosome (24.7%), biosynthesis of antibiotics (16.8%), and carbon metabolism (8.6%) (Fig. S5B).

To further investigate the mechanism of dimorphic transition regulated by MrStuA and MrXbp, we selected genes potentially involved in the dimorphic transition from transcriptome libraries (24) and examined these using transcriptional analysis. The following genes were selected: antioxidant enzyme genes (MrCat1 for catalase-1 and MrCat2 for catalase-2, MrSod1 for superoxide dismutase-1, and MrSod2 for superoxide dismutase-2), a determinant TF in response to oxidative stress (MrAp1 for activator protein-1), pigment biosynthesis-related genes (MrPks for polyketide synthase and MrLac for laccase), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-related genes (MrSlt2 for Slt2-type MAPK, MrHog1 for a stress-activated MAPK, and MrSwi6 for an APSES-type TF), and cAMP signal transduction pathway-related genes (MrPka for the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A and MrSok1 for cAMP-mediated signaling protein). Compared with the WT, the MrAp1, MrPka, MrLac, MrHog1, and MrSok1 genes were upregulated in the ΔMrStuA mutants, whereas the MrCat2 gene was downregulated (Fig. 2C). The MrCat2, MrSlt2, and MrSok1 genes were upregulated in the ΔMrXbp mutants, whereas the MrLac and MrPks genes were downregulated compared with the WT (Fig. 2C).

Roles of MrStuA and MrXbp in microsclerotium development.

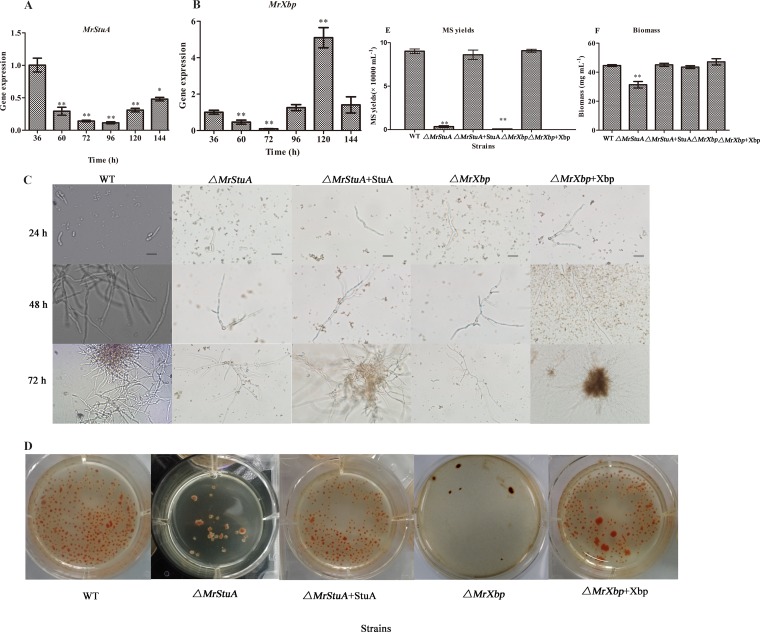

To examine the function of MrStuA and MrXbp in microsclerotium development, we investigated the relative transcriptional levels of MrStuA and MrXbp. Results showed that the expression of MrStuA was downregulated during microsclerotium development (60 to 144 h) compared with that at the germinating spore stage (36 h) (Fig. 3A). However, the expression of MrXbp was downregulated during hyphal vegetative growth (60 h) and the microsclerotium initiation and formation periods (72 h and 96 h) but was upregulated during microsclerotium maturation (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that MrStuA and MrXbp may have analogous roles in the early stage of microsclerotium development and diverse roles in microsclerotium maturation.

FIG 3.

Gene expression and phenotypic characterization of microsclerotium development in AM. Transcription of MrStuA (A) and MrXbp (B) during microsclerotium development. (C) Development of microsclerotium in AM. Scale bars: 50 μm. (D) Phenotypic characterization of microsclerotium formation. Conidial suspensions were inoculated in AM and cultured for 6 days. (E) Microsclerotium yield and (F) biomass of the tested strains. Error bars represent standard error. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; compared with WT or results at 36 h.

After 72 h of incubation in liquid amended medium (AM) (4), WT and complemented strains started to form microsclerotium, whereas minimal vegetative growth was observed in the ΔMrStuA and ΔMrXbp mutants (Fig. 3C). After incubation for 144 h, microsclerotium produced by WT strains matured and was accompanied by secondary mycelial growth, whereas the density of induced microsclerotium in the ΔMrStuA and ΔMrXbp mutants was significantly decreased (Fig. 3D) (P < 0.001). Microsclerotium yield of the ΔMrStuA mutants was reduced by approximately 95% compared with that of the WT (Fig. 3E), and biomass was decreased by 30% (Fig. 3F). Microsclerotium yield of the ΔMrXbp mutants was reduced by approximately 99% compared with that of the WT (Fig. 3E); however, there was no significant difference in biomass (Fig. 3F). Altogether, these results indicated that MrStuA and MrXbp play important roles in microsclerotium development.

Roles of MrStuA and MrXbp in activating signaling pathways during microsclerotium development.

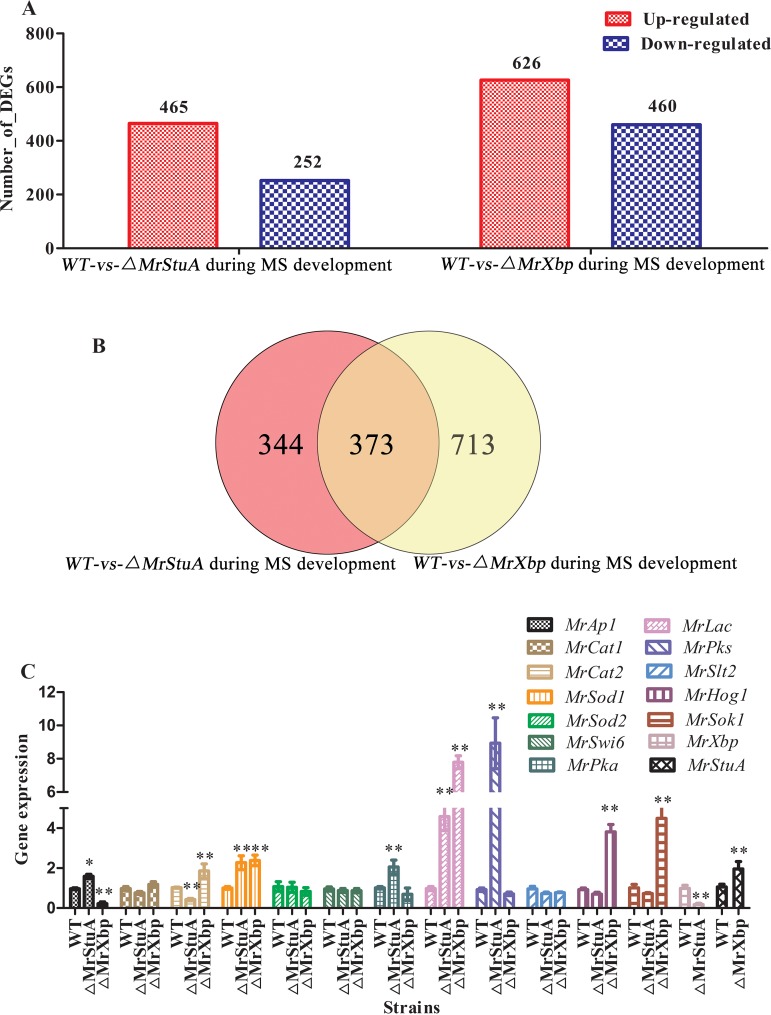

To identify the genes, signaling pathways, and metabolic pathways affected by MrStuA and MrXbp during microsclerotium development, we performed transcriptome sequencing analysis of WT and ΔMrStuA and ΔMrXbp mutants. Results showed that 465 genes were upregulated and 252 genes were downregulated in the ΔMrStuA mutants, whereas 626 genes were upregulated and 460 genes were downregulated in the ΔMrXbp mutants compared with the WT (Fig. 4A). Among these DEGs, 344 DEGs were regulated only by MrStuA and 713 DEGs were regulated only by MrXbp during microsclerotium development. Moreover, there were 373 DEGs coregulated by MrStuA and MrXbp during microsclerotium development (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Comparative transcriptomic and RT-qPCR analysis of genes related to microsclerotium (MS) development. (A) DEGs in WT versus ΔMrStuA mutants and WT versus ΔMrXbp mutants during microsclerotium development. (B) Venn diagram showing the number of shared DEGs between WT versus ΔMrStuA mutants and WT versus ΔMrXbp mutants during microsclerotium development. (C) RT-qPCR analysis of genes. Error bars represent standard error. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; compared with wild-type strain.

DEGs were functionally grouped into GO classes representing 38 functional categories in the ΔMrStuA mutants and 40 functional categories in the ΔMrXbp mutants (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Moreover, we found 20 COGs in the ΔMrStuA mutants and 21 COGs in the ΔMrXbp mutants (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). A total of 99 DEGs were assigned to 20 KEGG enrichment pathways in the ΔMrStuA mutants. The top three pathways were ribosome (21.2%), biosynthesis of amino acids (13.1%), and oxidative phosphorylation (9.1%) (see Fig. S8A in the supplemental material). A total of 129 DEGs were assigned to 20 KEGG enrichment pathways in the ΔMrXbp mutants. The top three pathways were oxidative phosphorylation (11.6%), ribosome (11.6%), and tyrosine metabolism (7.8%) (Fig. S8B).

To further investigate the genes regulated by MrStuA and MrXbp during microsclerotium development, several groups of genes were analyzed by RT-qPCR. Compared with the WT, the MrAp1, MrSod1, MrPka, MrLac, and MrPks genes were upregulated, whereas MrCat2 and MrXbp genes were downregulated in the ΔMrStuA mutants (Fig. 4C). The MrCat2, MrSod1, MrHog1, MrSok1, and MrStuA genes were upregulated, whereas the MrAp1 gene was downregulated compared with the WT in the ΔMrXbp mutants (Fig. 4C).

Overview of comparative transcriptomic data.

To confirm gene expression patterns obtained from transcriptome data, 14 genes from four sets of independent transcriptome data were analyzed by RT-qPCR (see Tables S1 to S4 in the supplemental material). Results showed that the transcriptome data and RT-qPCR were highly correlated (see Fig. S9 in the supplemental material).

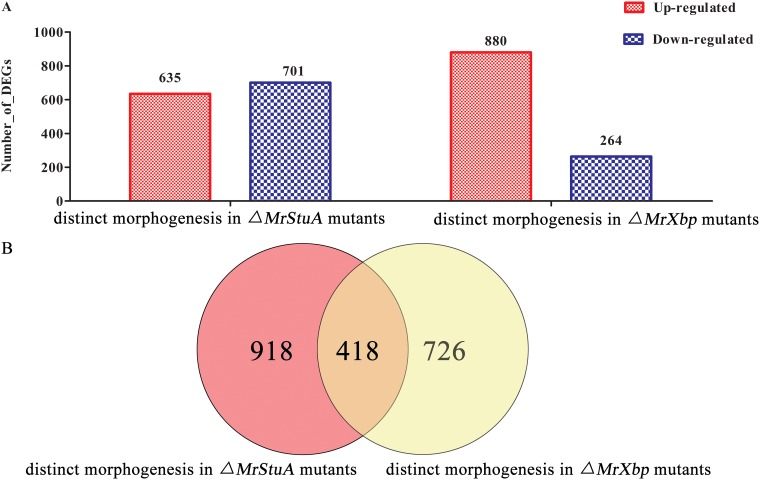

Furthermore, we established an overview of DEGs associated with the two distinct morphogenesis processes (dimorphic transition versus microsclerotium development) in ΔMrStuA and ΔMrXbp mutants. In relation to their expression levels during dimorphic transition, 635 genes were upregulated and 701 genes were downregulated during microsclerotium development in ΔMrStuA mutants, whereas 880 genes were upregulated and 264 genes were downregulated during microsclerotium development in ΔMrXbp mutants (Fig. 5A). Among these DEGs, 918 DEGs were only regulated by MrStuA and 726 DEGs were only regulated by MrXbp in the two distinct morphogenesis processes. Moreover, there were 418 DEGs coregulated by MrStuA and MrXbp in the two processes (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

Overview of comparative transcriptomic data for the two morphogenesis processes. (A) DEGs of dimorphic transition versus microsclerotium development in ΔMrStuA mutants and ΔMrXbp mutants. (B) Venn diagram showing the number of shared DEGs between dimorphic transition and microsclerotium development in ΔMrStuA mutants and ΔMrXbp mutants.

DEGs associated with the two distinct morphogenesis processes were functionally grouped into GO classes representing 39 functional categories in ΔMrStuA mutants and 36 functional categories in ΔMrXbp mutants (see Fig. S10 in the supplemental material). We found 21 COGs in the ΔMrStuA mutants and 20 COGs in the ΔMrXbp mutants (see Fig. S11 in the supplemental material). A total of 209 DEGs were assigned to 20 KEGG enrichment pathways in the ΔMrStuA mutants (see Fig. S12A in the supplemental material). The top three pathways were biosynthesis of antibiotics (19.6%), carbon metabolism (11.0%), and biosynthesis of amino acids (9.5%). A total of 181 DEGs were assigned to 20 KEGG enrichment pathways in the ΔMrXbp mutants (Fig. S12B). The top three pathways were biosynthesis of antibiotics (18.2%), carbon metabolism (9.3%), and biosynthesis of amino acids (9.3%).

Roles of MrStuA and MrXbp in stress tolerance and virulence.

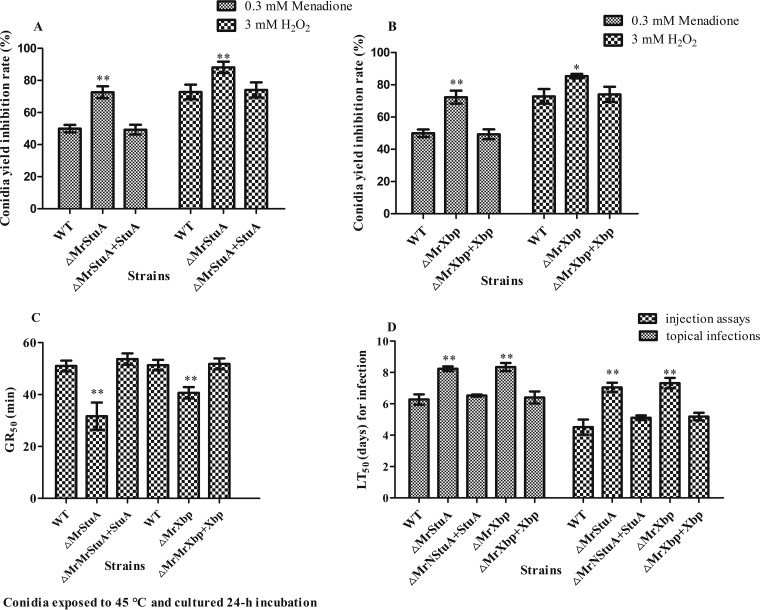

Compared to the WT strain, MrStuA and MrXbp deletion mutants were significantly more sensitive to oxidative stress. Rates of conidial yield inhibition were increased by 17.2% to 45.3% (P < 0.01) in ΔMrStuA mutants and by 14.5% to 44.1% (P < 0.05) in ΔMrXbp mutants, compared with those of WT and complementation strains, respectively (Fig. 6A and B). These results indicate that MrStuA and MrXbp contribute to tolerance of oxidative stress.

FIG 6.

Deletion of MrStuA or MrXbp altered cellular sensitivity to oxidative stress, heat stress, and virulence. Statistical analysis of conidial yield inhibition rates under oxidative stress in (A) ΔMrStuA mutants and (B) ΔMrXbp mutants. (C) GR50 for conidial tolerance to heat stress at 45°C. (D) LT50 for the virulence of each strain. Data were estimated using a Probit analysis with the SPSS software. Error bars represent standard error. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; compared with WT.

Conidial thermotolerance was quantified as the germination rate resulting in 50% germination (GR50) after exposure of conidial suspension to 45°C, as described previously (4). Compared with the WT strain, the GR50 for conidial tolerance to 45°C was shortened by 20.26% in the ΔMrStuA mutants (GR50, 40.3 ± 3.7 min) and by 37.9% in the ΔMrXbp mutants (GR50, 33.6 ± 4.4 min) (Fig. 6C). These results showed that MrStuA and MrXbp have analogous roles in response to thermal stress.

The mean lethal time (LT50) of WT strains to kill 50% of Spodoptera litura larvae was 6.2 ± 0.4 days in topical bioassays for normal cuticle infection and 4.3 ± 0.5 days following injection for cuticle-bypassing infection bioassays (Fig. 6D). Compared with data from WT and complemented strains, lethal action through normal infection was delayed by 1.96 days in the ΔMrStuA mutants and 2.07 days in the ΔMrXbp mutants. The delay of lethal action following cuticle-bypassing infection increased to 2.75 days in the ΔMrStuA mutants and 3.02 days in the ΔMrXbp mutants (Fig. 6D). These results showed that lethal action was significantly delayed in the two mutants.

DISCUSSION

Developmental processes play important roles in the life cycle of ascomycete fungi. Here, we systematically characterized MrStuA and MrXbp, encoding two members of the APSES-type TFs that have essential roles in dimorphic transition, thermotolerance, oxidative adaptation, conidium and microsclerotium development, and virulence. We additionally identified commonalities and differences in the regulation of gene expression during the developmental processes of dimorphic transition and microsclerotium formation.

The conidiation process in filamentous fungi is a precisely timed and genetically programmed event that occurs from vegetative growth to asexual development (28). Although signaling pathways regulating dimorphic transition and conidiation in Metarhizium species are well characterized (23, 27, 29–32), no member of the APSES family has been characterized in entomopathogenic fungi. Similar to Asm1p in N. crassa (9), StuA in A. nidulans (11), FgStuA in Fusarium graminearum (33), and Vst1 in Verticillium species (16), mutation of MrStuA appeared to interfere with conidiation (Fig. 1). Previous investigations also identified diverse functions of the APSES TFs in different fungal species. For instance, chlamydospore formation is dramatically promoted in Fusarium oxysporum ΔFoStuA mutants, but these phenotypes are not observed in F. graminearum ΔFgStuA mutants (33). Unlike the highly conserved DNA-binding motif of MrStuA, MrXbp homologs show low similarity among different species. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no studies on the biological functions of Xbp in fungi have been reported. Interestingly, a decrease conidial yield in ΔMrXbp mutants was observed (Fig. 1).

Meanwhile, similar to the ΔMrSwi6 mutants (23) and ΔMrStuA mutants in M. rileyi, we also observed a delay in dimorphic transition in the ΔMrXbp mutants (Fig. 1). Dimorphic transition is critical for pathogenesis, virulence, and the life cycle of dimorphic fungi (2, 4). Recent investigations confirmed that many signaling pathways, including activator protein-1 (29), cell wall integrity (23, 34), and high osmolarity glycerol (27) signaling pathways, take part in the regulation of morphology. Furthermore, various conidial suspensions of strains had different dimorphic transition rates, demonstrating again that there is quorum sensing in the dimorphic transition of M. rileyi (23). However, the molecular mechanism of quorum sensing is complex (35). To investigate the mechanisms of dimorphic transition regulated by APSES TFs, we conducted comparative transcriptomic analysis. Results revealed not only analogous but also distinct strategies in the regulation of dimorphic transition by the two APSES-type TFs in M. rileyi (Fig. 2). StuA homologs in fungi are targets of the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) signal transduction pathway (10, 16, 36, 37). The expression of cAMP signal transduction pathway-associated genes was significantly changed during dimorphic transition in ΔMrStuA mutants, adding further evidence to support this viewpoint. The oxidative stress triggers dimorphic transition in M. rileyi (27). The MrAp1 gene was significantly upregulated in ΔMrStuA mutants, indicating overlapping between MrStuA and MrAp1 with the PAP1 domain during dimorphic transition. Moreover, no significant change among the three APSES-type TFs (MrSwi6, MrStuA, and MrXbp) and different signaling pathways with different expression patterns were found in MrStuA and MrXbp single-deletion mutants during dimorphic transition (Fig. 2C).

Melanized microsclerotium formation induced in liquid culture is also a complex development process (8). Similar to Vst1 in Verticillium species (16), the APSES TFs are key regulators of microsclerotium development (Fig. 3). Our previous study demonstrated that intracellular oxidative stress can trigger microsclerotium differentiation (24, 27) and that MrAp1 plays an important role in mediating redox homeostasis during microsclerotium development (27). Our analysis found that expression of MrAp1 was upregulated in ΔMrStuA mutants; however, it was downregulated in ΔMrXbp mutants (Fig. 4C), indicating that the two fungal TFs have diverse regulatory patterns in their interactions with MrAp1 during microsclerotium development. Further investigations confirmed 57 genes coregulated by the three TFs during M. rileyi development (see Fig. S13 in the supplemental material). Moreover, investigations revealed downregulated expression of MrXbp following a single deletion of MrStuA and upregulated expression of MrStuA following a single deletion of MrXbp, indicating that these two APSES TF genes have overlapping regulatory patterns during microsclerotium development (Fig. 4C). Transcriptomic analysis identified oxidative phosphorylation as the major analogous KEGG enrichment pathway (Fig. S8).

Specialized cellular differentiation of fungal growth under different conditions requires spatial and temporal regulation of gene expression. Unlike MrStuA, which plays opposite roles to cAMP/PKA and AP-1 signaling pathways during dimorphic transition and microsclerotium development, MrXbp has varied regulatory patterns on the growth of M. rileyi in liquid and solid conditions but has overlapping regulatory patterns with MrStuA (Fig. 2, 4, and 5). Transcriptomic analysis identified 13 identical and 7 distinctive KEGG enrichment pathways regulated by the two APSES-type TFs during dimorphic transition and microsclerotium formation (Fig. S12). However, simultaneous knockout of MrStuA and MrXbp has not been successful despite many attempts. Further experiments are needed to elucidate the details of the varied regulatory patterns by the two APSES-type TFs.

Successful insect infection by entomopathogenic fungi is highly related to appressorium formation, morphological form shifting, utilization of nutrition from the host, and adaptation to stress from the host (30, 32). Similar to observations in Leptosphaeria maculans (37) and Stagonospora nodorum (38) and unlike those in Verticillium species (16), deletion of MrStuA resulted in decreased virulence (Fig. 6). Moreover, virulence assays revealed that ΔMrXbp mutants were significantly less virulent than the WT strain. Possible explanations for this are reduced dimorphic transition and hypersensitivity to oxidative stress.

In the present study, we dissected the regulatory roles of MrStuA and MrXbp in dimorphic transition, conidium and microsclerotium development, and stress tolerance in the entomopathogenic fungus M. rileyi, providing innovative information on the regulatory mechanisms of fungal morphogenesis. Such systematic and transcriptome-wide characterization can be effectively used to generate more information on the regulatory mechanisms of fungal morphogenesis processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and culture conditions.

M. rileyi strain CQNr01 was obtained from the Engineering Research Center for Fungal Insecticides, Chongqing, China. All strains used in this study were cultured on SMAY for conidiation assays or in AM culture for microsclerotium assays, according to previous methods (29). Escherichia coli DH5α (Invitrogen, Shanghai, China) was used for recombinant DNA manipulation. Agrobacterium tumefaciens AGL-1 (Invitrogen) was used for fungal transformations. These bacteria were cultured according to previously described methods (29).

Bioinformatics and phylogenetic analysis.

MrStuA and MrXbp genes were amplified using primers MrStuA-F/MrStuA-R and MrXbp-F/MrXbp-R based on sequences of a previously published transcriptome library (24) (Table 1). Protein sequences were aligned using InterProScan (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/pfa/iprscan) and DNAMAN software (Lynnon Corporation). Phylogenetic trees were generated using MEGA 6.0 (39).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Usage | Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| PCR of the genomic DNA sequences | MrXbp-F | CGACCCCTTCCAACTCAAACGCAC |

| MrXbp-R | CTCCCACCCGTGCCACTTTTCCCC | |

| MrStuA-F | AAGACCCTCCTTCCGACCTCCTCT | |

| MrStuA-R | TATAACCCACAGCAAGTCGTCAAC | |

| Used as construction of gene disruption vector | MrXbpLF | CGGAATCAGTCAGCCCTCTCGGGTCCGTCATC |

| MrXbpLR | CCGCTCGAGCTGTGGGCAGATGCTTCGTGGTTCA | |

| MrXbpRF | GCTCTAGATGGAAGCGTTATCAGAGCAGAGCGA | |

| MrXbpRR | AACTGCAGGGCAAGTCACCACGAGCCCCGAGGG | |

| MrStLF | CGGAATTCGGCATTTCAAGTGAACACCAAGTCTT | |

| MrStLR | CCGCTCGAGATCATTTGGCAGATTGGACGACGGTA | |

| MrStRF | GCTCTAGATATCTCGCCACACATCTTTCAAGCAA | |

| MrStRR | CCCAAGCTTAGGCACAGGGTGGAATGTATCGGCTA | |

| Used as construction of gene complementation plasmid | MrXbp-HF | CCGCTCGAGCTCGGGCAAGGGCAAAGGCTCACA |

| MrXbp-HR | GCTCTAGACGATGCCTGGGTGAAGCGGTTCAAG | |

| MrSt-HF | GCTCTAGAGGAGTGTCCATCAATGTTCCGTAGT | |

| MrSt-HF | AACTGCAGAACAGGCGTGCTAAGTAACATAGAA | |

| Mutants by PCR verification | MrXbpF | CTCGGGCAAGGGCAAAGGCTCACA |

| MrXbpR | GCACCTCGCTGCCAATAATGAAGA | |

| MrXbp-OF | CCAGGCAGATAATAACAGCATTCA | |

| MrXbp-OR | TCGCTTTATTCGGATTCCTACTTC | |

| MrStR | TTGGGCAGTCTGACGGTTCAAGCC | |

| MrStF | TTGACCCAGAACTCTAAACCAGCA | |

| MrSt-OF | ATGGGAGGATGAAGGCAGTCTGTG | |

| MrSt-OR | CATTACCCATACCATTGGCTTCACT | |

| hph-F | GCTCTCGCTAAACTCCCCAATGTCA | |

| hph-R | CATTGACTGGAGCGAGGCGATGTTC | |

| RT-qPCR analysis | MrXbp-qF | GCATTCAATGTCTCGCAGTT |

| MrXbp-qR | ATTCGTGGGAATCTGAAAGG | |

| MrSt-qF | TCACTACGCTGGGTTCGATA | |

| MrSt-qR | TTCGACCTGAAAGCACAGAC | |

| Mrtef-qF | GTCATCGTCCTCAACCATC | |

| Mrtef-qR | CAGTCTCAACAGCCTTACC | |

| Mrtub-qF | GGCAAGGTCGCTATGAAG | |

| Mrtub-qR | CTGGATGGAGGTAGAGTTAC | |

| MrCat1-qF | GAGCCAGCCTCGTCTGTTCT | |

| MrCat1-qR | CTGGGCGAGGACGTTCTTCT | |

| MrCat2-qF | AAGGATCCGCAGAAGCGTGA | |

| MrCat2-qR | AAGGTGTGGCCTCCAGCAAT | |

| MrSod1-qF | TGCCTGCTTTATCAATCGAC | |

| MrSod1-qR | TCAAGAATGAGTGTGCGTCA | |

| MrSod2-qF | AGGTTCTCCCAGAAGAGGGA | |

| MrSod2-qR | CGTACGTGACGAACCTCAAC | |

| MrAp1-qF | ACATACGCCCAGAAAGAACC | |

| MrAp1-qR | AGTTGGTTGCAGCTCAAATG | |

| MrH101-qF | TGGAGAAGCGTTTGGAGGAT | |

| MrH101-qR | GCCACCAGAAGCATTGAGAG | |

| MrCp450-qF | CTATATGGCACGTCCACGAC | |

| MrCp450-qR | GCTACGATTCCTTGGTTGGT | |

| MrHog1-qF | GCATCGTGACTTGAAGCCTA | |

| MrHog1-qR | GGGCTCGGTAATATCGTGTT | |

| MrSlt2-qF | TGTGCGGCCTCAAGTATATC | |

| MrSlt2-qR | CGAGGCCAAAGTCACAGAT | |

| MrHapX-qF | AGCCACAGGAACTTCTCCAA | |

| MrHapX-qR | GACGCTCATGATGCTAGCTG | |

| MrPkac-qF | AGGAGGTTGGTGATGAAGGG | |

| MrPkac-qR | CCCAAGTATACGCGCTCAAG | |

| MrCwb-qF | GGTGATTTCTCGTGGCTGTC | |

| MrCwb-qR | GGCCTCTCGTCGAAATCTTG | |

| MrCel-qF | GAAATCTCGGCCACGTTCAA | |

| MrCel-qR | GGAGAGACTTGGACGCTGTA | |

| MrH90-qF | CCCAGAGACAAGCAACGAAG | |

| MrH90-qR | TCTCGCCCAAGTCTCTCATC | |

| MrPtp -qF | GCAGTTTCCGCTTCTCGATT | |

| MrPtp -qR | CTGTGATTGTCCAGCTCACG | |

| MrNsdD-qF | CAACGGAGCATATGGTCATC | |

| MrNsdD-qR | CATGCCTAGGTGAGACTGGA | |

| Mrlac-qF | AGTGCACCGCAAACAATCAT | |

| Mrlac-qR | GCGACTGTCTGGTTGAAGAC | |

| MrCcp-qF | GTCCTTGGTAGGGTTGACGA | |

| MrCcp-qR | ATGGTACTCTGAGCCTGCTG | |

| Mrpks-qF | GCCTCCTCCATCGTCAAGGT | |

| Mrpks-qR | GCGCTCGTCTCGAGGAAGTA | |

| MrAtp10-qF | TCTTCTGTCGGCTCTGGTTT | |

| MrAtp10-qR | AAGCTTCGAGTCTCCCACAA | |

| MrWsc-qF | CGGGCGATTTGACTCTTGTT | |

| MrWsc-qR | GTTGTGTTGTCGAAGGCAGT | |

| MrMas1-qF | ACGAACAATGCACACGTTCT | |

| MrMas1-qR | CTTCACTGGCTTGTCCATCG | |

| MrClp-qF | TCACTAGAACTTGCCTGCCA | |

| MrClp-qR | TTCTGGCTCTATGGCTACGG | |

| MrRad2-qF | CTGAGTGTCAGCGACTGTTG | |

| MrRad2-qR | TCCTTCCGCTGCTCACTAAA | |

| MrEmk1-qF | CGAGAATGTTGGAGGGCTTG | |

| MrEmk1-qR | TCGAGTGTCGAGGGTATTCG | |

| MrTapt1-qF | CGAGGTAGACCAGGACCATC | |

| MrTapt1-qR | TTCCATATCGTGCCTCGTGA | |

| MrMob-qF | CCTGACGTTACACCGTTGAC | |

| MrMob-qR | TAGGATGGTGCAGTTGAGCA | |

| MrSem-qF | GACTTGTTTCTCCCGGTTCG | |

| MrSem-qR | CTGACCAGCAACGAAGAAGG | |

| MrUce-qF | CGCTTCCCTACCGAATACC | |

| MrUce-qR | TCGTCGCCTGGTCTGTGGA | |

| MrSwi6-qF | CCACCCAGATTCTCAAGGTT | |

| MrSwi6-qR | TGCTCGCCTGTTTGTATCTC | |

| MrSok1-qF | GACCAACAACAACAGCCACT | |

| MrSok1-qR | TCTTGTCCGTCCCGTAACAA |

Construction of deletion and complementation mutants.

The 5′ and 3′ flanking sequences of MrStuA and MrXbp genes were amplified from the M. rileyi genome database (NCBI accession no. AZHC00000000.1) (25) via PCR and inserted independently into Pzp-Ptrpc-Hph-Knock (resistance to hygromycin B). Disruption vectors were introduced into M. rileyi via Agrobacterium sp.-mediated transformation as described previously (29). Transformants were selected and gene mutants were verified by PCR using a combination of primers targeting flanking regions (MrStF/MrStR or MrXbpF/MrXbpR) (Table 1), primers annealing within introduced cassettes (hph-F/hph-R), and another pair of primers identifying the open reading frame (ORF) (MrSt-OF/MrSt-OR or MrXbp-OF/MrXbp-OR) (Table 1). PCR sequences were then sequenced. Complementation of ΔMrStuA mutants or of ΔMrXbp mutants was performed by introducing the complementation vector Pzp-Sur-cassette (resistance to sulfonylurea). ORFs of MrStuA and MrXbp with their promoter and terminator regions were amplified using primers MrSt-HF/MrSt-HR and MrXbp-HF/MrXbp-HR, respectively (Table 1). PCR products were digested by restriction endonucleases and inserted into the Pzp-Sur-cassette to generate complementation vectors (Pzp-Sur-MrStuA and Pzp-Sur-MrXbp). The vectors were introduced into gene mutants via Agrobacterium sp.-mediated transformation, and transformants were screened as described previously (29).

Phenotypic experiments.

To investigate the role of MrStuA and MrXbp on dimorphic transition, vegetative growth, and conidial development, conidial suspensions (106, 107, and 108 conidia ml−1) were pipetted onto SMAY plates under continuous light at 25°C for 12 days. After 6 days of incubation, three culture plugs (5 mm diameter) were removed every 3 days from each plate using a cork borer. The concentration of conidia was counted as described previously (29). Colony morphology was investigated, and images were collected using a digital camera (60-mm macro lens; Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

To evaluate the influence of ΔMrStuA and ΔMrXbp mutants on dimorphic transition, switching rates of different strains were counted as described previously (27). Briefly, approximately 100 simple yeast cells were pipetted onto SMAY medium and regularly observed for colony morphology. Switching rates at various time points were recorded, and TT50 was estimated.

Conidial germination investigations were conducted as described previously (4). Briefly, conidial suspensions (1 × 107 conidia) were spread evenly onto SMAY plates and incubated at 25°C. After inoculation for 14 h, conidial germination rates were assessed every 2 h until full germination. Conidial thermotolerance was quantified as the germination rate resulting in 50% germination after exposure at 45°C for 0 to 120 min (4). Conidial oxidative stress tolerance was assessed after incubation on SMAY plates containing 0.03 mM menadione and 3 mM H2O2. Conidial suspensions (1 × 108 conidia) were pipetted and cultured at 25°C. Conidial yields were counted at 12 days postincubation. The conidium yield inhibition rate was calculated relative to untreated controls, where inhibition rate (%) = (number of untreated colonies – number of treated colonies)/number of untreated colonies × 100.

To evaluate the roles of MrStuA and MrXbp in microsclerotium development, conidial suspensions (1 × 107 conidia) were inoculated in AM culture for 6 days as described previously (4). Biomass and microsclerotium yield were quantified as described previously (4). Microsclerotium morphologies were observed using the digital camera and a microscope.

Transcriptional analysis.

To determine time-specific expression patterns of MrStuA and MrXbp during microsclerotium development, samples of WT inoculated in AM were collected at 36 h (yeast-like cell period), 60 h (hyphal elongation and microsclerotium initiation period), 72 h (microsclerotium formation), 96 h (mass microsclerotium formation), and 120 h (microsclerotium maturation) for RNA extraction. To determine time-specific expression patterns during conidiation, samples of WT inoculated onto SMAY were collected at 0 days (the start of incubation), 2 days (yeast-like cells period), 4 days (hyphal period), 6 days (conidiation initiation), and 8 days (the start of conidium maturation) for RNA extraction. Gene expression patterns were confirmed for samples of each strain cultured in AM for 72 h or on SMAY for 3 days. Total RNA samples were collected using the RNAiso plus reagent (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using PrimeScript RT master mix (TaKaRa). RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR green detection. Transcripts of β-tubulin (Mrtub) and translation elongation factor (Mrtef) genes were used as internal standards. Transcript ratios were evaluated using the 2−ΔΔCT method (40).

Digital gene expression profiling analysis.

To further study the expression patterns of MrStuA and MrXbp prior to dimorphic transition and microsclerotium development, transcriptome sequencing analysis was performed. Total RNA extraction from three replicate samples, library construction, and sequencing were performed as described previously (29). Genes with fold change of ≥2 and false discovery rate (FDR) of <0.01 were considered significantly differentially expressed. DEGs were identified using DESeq software (41). DEGs were annotated and assigned functional categories using MapMan annotation (42).

Insect bioassays.

Bioassays were conducted against third-instar larvae according to previously described methods (27). Briefly, topical infections were performed by immersing larvae in conidial suspensions (1 × 107 conidia). For injection assays, each insect was injected with the conidial suspension (1 × 106 conidia). Three replicate groups comprising 30 larvae each were tested. The mortality rate was recorded daily, and LT50 values were determined by Probit analysis with the SPSS program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Statistical analysis.

All assays were repeated three times. Differences in the data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and significance was determined by Duncan’s multiple range tests using SPSS 17.0 software. Graphs were constructed with GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Error bars represent standard error.

Data availability.

The mRNA raw sequence data were deposited in the Beijing Institute of Genomics Genome Sequence Archive (http://gsa.big.ac.cn/) with the accession number PRJCA002177 (https://bigd.big.ac.cn/search?dbId=bioproject&q=PRJCA002177+). Orthologs of MrStuA and MrXbp were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MN180231 and MN180232, respectively.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of the China (no. 31701127), Science and Technology Project of Sichuan (no. 2019YJ0407) and Luzhou (no. 2018-JYJ-32), and Major Special Projects (no.110201601023(LS-03)).

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Faria MR, Wraight SP. 2007. Mycoinsecticides and mycoacaricides: a comprehensive list with worldwide coverage and international classification of formulation types. Biol Control 43:237–256. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2007.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pendland JC, Boucias DG. 1997. In vitro growth of the entomopathogenic hyphomycete Nomuraea rileyi. Mycologia 89:66–71. doi: 10.2307/3761173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fronza E, Specht A, Heinzen H, de Barros NM. 2017. Metarhizium (Nomuraea) rileyi as biological control agent. Biocontrol Sci Techn 27:1243–1264. doi: 10.1080/09583157.2017.1391175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song ZY, Yin YP, Jiang SS, Liu JJ, Wang ZK. 2014. Optimization of culture medium for microsclerotia production by Nomuraea rileyi and analysis of their viability for use as a mycoinsecticide. BioControl 59:597–605. doi: 10.1007/s10526-014-9589-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gauthier GM. 2015. Dimorphism in fungal pathogens of mammals, plants, and insects. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004608. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang LQ, Lin XR. 2012. Morphogenesis in fungal pathogenicity: shape, size, and surface. PLoS Pathog 8:e1003027. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shelest E. 2017. Transcription factors in fungi: TFome dynamics, three major families, and dual-specificity TFs. Front Genet 8:53. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2017.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song ZY. 2018. Fungal microsclerotia development: essential prerequisite, influence factors, and molecular mechanism. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102:9873–9880. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9400-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aramayo R, Peleg Y, Addison R, Metzenberg R. 1996. Asm-1, a Neurospora crassa gene related to transcriptional regulators of fungal development. Genetics 144:991–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bockmühl DP, Ernst JF. 2001. A potential phosphorylation site for an A-type kinase in the Efg1 regulator protein contributes to hyphal morphogenesis of Candida albicans. Genetics 157:1523–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller KY, Wu J, Miller BL. 1992. StuA is required for cell pattern formation in Aspergillus. Genes Dev 6:1770–1782. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gimeno CJ, Fink GR. 1994. Induction of pseudohyphal growth by overexpression of PHD1, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene related to transcriptional regulators of fungal development. Mol Cell Biol 14:2100–2112. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward MP, Gimeno CJ, Fink GR, Garrett S. 1995. SOK2 may regulate cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase-stimulated growth and pseudohyphal development by repressing transcription. Mol Cell Biol 15:6854–6863. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mancera E, Porman AM, Cuomo CA, Bennett RJ, Johnson AD. 2015. Finding a missing gene: EFG1 regulates morphogenesis in Candida tropicalis. G3 (Bethesda) 5:849–856. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.017566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohara T, Tsuge T. 2004. FoSTUA, encoding a basic helix-loop-helix protein, differentially regulates development of three kinds of asexual spores, macroconidia, microconidia, and chlamydospores, in the fungal plant pathogen Fusarium oxysporum. Eukaryot Cell 3:1412–1422. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.6.1412-1422.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarmiento-Villamil JL, García-Pedrajas NE, Baeza-Montañez L, García-Pedrajas MD. 2018. The APSES transcription factor Vst1 is a key regulator of development in microsclerotium- and resting mycelium-producing Verticillium species. Mol Plant Pathol 19:59–76. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Q, Szaniszlo PJ. 2007. WdStuAp, an APSES transcription factor, is a regulator of yeast-hyphal transitions in Wangiella (Exophiala) dermatitidis. Eukaryot Cell 6:1595–1605. doi: 10.1128/EC.00037-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramírez-Zavala B, Domínguez A. 2008. Evolution and phylogenetic relationships of APSES proteins from Hemiascomycetes. FEMS Yeast Res 8:511–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2008.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doedt T, Krishnamurthy S, Bockmuhl DP, Tebarth B, Stempel C, Russell CL, Brown AJP, Ernst JF. 2004. APSES proteins regulate morphogenesis and metabolism in Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell 15:3167–3180. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e03-11-0782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J-Y, Kim L-H, Kim H-E, Park J-S, Han K-H, Han D-M. 2013. A putative APSES transcription factor is necessary for normal growth and development of Aspergillus nidulans. J Microbiol 51:800–806. doi: 10.1007/s12275-013-3100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishimura M, Fukada J, Moriwaki A, Fujikawa T, Ohashi M, Hibi T, Hayashi N. 2009. Mstu1, an APSEE transcription factor, is required for appressorium-mediated infection in Magnaporthe grisea. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 73:1779–1786. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi ZQ, Wang Q, Dou XY, Wang W, Zhao Q, Lv RL, Zhang HF, Zheng XB, Wang P, Zhang ZG. 2012. MoSwi6, an APSES family transcription factor, interacts with MoMps1 and is required for hyphal and conidial morphogenesis, appressorial function, and pathogenicity of Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol Plant Pathol 13:677–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00779.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang ZK, Yang J, Xin CY, Xing XR, Yin YP, Chen L, Song ZY. 2019. Regulation of conidiation, dimorphism transition, and microsclerotia formation by MrSwi6 transcription factor in dimorphic fungus Metarhizium rileyi. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 35:46. doi: 10.1007/s11274-019-2619-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song ZY, Yin YP, Jiang SS, Liu JJ, Chen H, Wang ZK. 2013. Comparative transcriptome analysis of microsclerotia development in Nomuraea rileyi. BMC Genomics 14:411. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shang YF, Xiao GH, Zheng P, Cen K, Zhan S, Wang CS. 2016. Divergent and convergent evolution of fungal pathogenicity. Genome Biol Evol 8:1374–1387. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu X, Xiao GH, Zheng P, Shang YF, Su Y, Zhang XY, Liu XZ, Zhan S, St Leger RJ, Wang CS. 2014. Trajectory and genomic determinants of fungal-pathogen speciation and host adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:16796–16801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412662111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song ZY, Yang J, Xin CY, Xing XR, Yuan Q, Yin YP, Wang ZK. 2018. A transcription factor, MrMsn2, in the dimorphic fungus Metarhizium rileyi is essential for dimorphism transition, aggravated pigmentation, conidiation and microsclerotia formation. Microb Biotechnol 11:1157–1169. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mah J-H, Yu J-H. 2006. Upstream and downstream regulation of asexual development in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot Cell 5:1585–1595. doi: 10.1128/EC.00192-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song ZY, Yin YP, Lin YL, Du F, Ren GW, Wang ZK. 2018. The bZip transcriptional factor activator protein-1 regulates Metarhizium rileyi morphology and mediates microsclerotia formation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102:4577–4588. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-8941-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang JB, St Leger RJ, Wang CS. 2016. Advances in genomics of entomopathogenic fungi. Adv Genet 94:67–105. doi: 10.1016/bs.adgen.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao H, Lovett B, Fang W. 2016. Genetically engineering entomopathogenic fungi. Adv Genet 94:137–163. doi: 10.1016/bs.adgen.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen XX, Xu C, Qian Y, Liu R, Zhang QQ, Zeng GH, Zhang X, Zhao H, Fang WG. 2016. MAPK cascade-mediated regulation of pathogenicity, conidiation and tolerance to abiotic stresses in the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium robertsii. Environ Microbiol 18:1048–1062. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lysøe E, Pasquali M, Breakspear A, Kistler HC. 2011. The transcription factor FuStuAp influences spore development, pathogenicity, and secondary metabolism in Fusarium graminearum. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 24:54–67. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-03-10-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xin CY, Xing XR, Wang F, Liu JX, Ran ZN, Chen WB, Wang GX, Song ZY. 2020. MrMid2, encoding a cell wall stress sensor protein, is required for conidium production, stress tolerance, microsclerotium formation and virulence in the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium rileyi. Fungal Genet Biol 134:103278. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boucias D, Liu S, Meagher R, Baniszewski J. 2016. Fungal dimorphism in the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium rileyi: detection of an in vivo quorum-sensing system. J Invertebr Pathol 136:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saputo S, Kumar A, Krysan DJ. 2014. Efg1 directly regulates ACE2 expression to mediate cross talk between the cAMP/PKA and RAM pathways during Candida albicans morphogenesis. Eukaryot Cell 13:1169–1180. doi: 10.1128/EC.00148-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soyer JL, Hamiot A, Ollivier B, Balesdent MH, Rouxel T, Fudal I. 2015. The APSES transcription factor LmStuA is required for sporulation, pathogenic development and effector gene expression in Leptosphaeria maculans. Mol Plant Pathol 16:1000–1005. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.IpCho SVS, Tan K-C, Koh G, Gummer J, Oliver RP, Trengove RD, Solomon PS. 2010. The transcription factor StuA regulates central carbon metabolism, mycotoxin production, and effector gene expression in the wheat pathogen Stagonospora nodorum. Eukaryot Cell 9:1100–1108. doi: 10.1128/EC.00064-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Roy NV, Paepe AD, Speleman F. 2002. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol 3:research0034.1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Östlund G, Schmitt T, Forslund K, Kostler T, Messina DN, Roopra S, Frings O, Sonnhammer EL. 2010. InParanoid 7: new algorithms and tools for eukaryotic orthology analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 38:196–203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thimm O, Bläsing O, Gibon Y, Nagel A, Meyer S, Krüger P, Selbig J, Müller LA, Rhee SY, Stitt M. 2004. MAPMAN: a user-driven tool to display genomics data sets onto diagrams of metabolic pathways and other biological processes. Plant J 37:914–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2004.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The mRNA raw sequence data were deposited in the Beijing Institute of Genomics Genome Sequence Archive (http://gsa.big.ac.cn/) with the accession number PRJCA002177 (https://bigd.big.ac.cn/search?dbId=bioproject&q=PRJCA002177+). Orthologs of MrStuA and MrXbp were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MN180231 and MN180232, respectively.