In early December 2019, a series of pneumonia cases was reported in Wuhan, China resulting from a novel coronavirus infection designated as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses as of January 7, 2020, and named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the World Health Organization (WHO) as of February 11, 2020.1 SARS-CoV-2 is a novel enveloped RNA betacoronavirus, that represents the seventh member of the coronavirus family, which includes 4 common human coronaviruses (229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1) and 2 other strains, including SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (MERS-CoV).2 , 3 SARS-CoV-2 has approximately 79% and 50% phylogenetic similarity to SARS-Co-V and MERS-CoV, respectively.2

This virus is suspected to have a zoonotic origin and is estimated to have resulted in 591,802 cases in 176 countries with 26,996 deaths as of March 27, 2020.4 COVID-19 was first reported in the United States on January 20, 2020 and accounted for a total number of 100,717 cases and 1544 deaths as of March 27, 2020.4 The morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19 exceeds previous coronavirus infection outbreaks, including SARS (8098 infections, 774 deaths) and MERS (2458 infections, 848 deaths).5 , 6 An initial analysis of 72,314 cases from China revealed that an estimated 81% of infections are characterized as mild, 14% are severe, and 5% are critical (defined as respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction or failure), with an overall fatality rate of 2.3%.7 In the United States, an analysis of 4226 cases from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as of March 16, 2020 reported estimated rates of hospitalization of 20.7%–31.4%, intensive care unit admission rates of 4.9%–11.5%, and case fatality rates 1.8%–3.4%.8 The WHO declared a global health emergency on January 30, 20209 and pandemic status on March 11, 2020.10

The most common presenting symptoms for COVID-19 include fever, cough, and shortness of breath, although other frequently observed symptoms include fatigue, headache, and muscle soreness. Extrapulmonary symptoms may occur early in the disease course. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and/or diarrhea can occur early, but are rarely the sole presenting feature11; GI symptoms may be associated with poor clinical outcomes, including higher risk of mortality.11 Of note, the first reported case of COVID-19 in the United States presented with a 2-day history of dry cough, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, followed by diarrhea on hospital day 2, with subsequent confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 in a stool specimen.12 Subsequent studies have confirmed positive SARS-CoV-2 cases using real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction in stool specimens of patients with COVID-19 infection,13 , 14 with immunofluorescence data demonstrating that angiotensin converting enzyme II is abundantly expressed in gastric, duodenal, and rectal epithelia, thereby implicating angiotensin converting enzyme II as a potential viral receptor for entry to uninfected host cells, and raising the possibility for fecal–oral transmission, although it is unclear whether the viral concentration in the stool is sufficient for transmission.14 Furthermore, angiotensin converting enzyme II receptors may additionally be expressed in hepatic cholangiocytes, potentially permitting direct infection of hepatic cells, and early cohort studies of COVID-19 have revealed that abnormal liver enzymes are commonly observed.15

Scope and Purpose

Multiple questions have been raised regarding the GI and liver manifestations of COVID-19 infection and the implications of SARS-CoV-2 infection on GI endoscopy. A joint society statement by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy on March 15, 2020 highlighted the potential for SARS-CoV-2 transmission through droplets, an established mode of transmission, and possibly fecal shedding, and the associated risk for transmission to endoscopy personnel during GI endoscopy procedures.16

In this document, we seek to summarize the data and provide evidence-based recommendation and clinical guidance. This rapid recommendation document was commissioned and approved by the AGA Governing Board to provide timely, methodologically rigorous guidance on a topic of high clinical importance to AGA members in the context of an emerging pandemic. It was published online on April 1st, 2020 and has an expiration date of six months.

Panel Composition and Conflict of Interest Management

This rapid guideline was developed by gastroenterologists and guideline methodologists from the AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee and Clinical Practice Updates Committee, who were assembled on March 15, 2020, in collaboration with the AGA Governing Board, to define time-urgent clinical questions, perform systematic reviews, develop summary evidence profiles, and formulate rapid recommendations. Additionally, to ensure representation of the public/consumer, this guideline was reviewed by 2 COVID-19–positive patients. Panel members disclosed all potential conflicts of interest according to the AGA Institute policy.

Target Audience

The target audience of these guidelines includes gastroenterologists, hepatologists, advanced practice providers, nurses, and other health care professionals involved in GI endoscopy. Patients, the public, as well as policy-makers may also benefit from these guidelines. These guidelines are not intended to impose a standard of care for individual institutions, health care systems, or countries. They provide the basis for rational informed decisions for patients, parents, clinicians, and other health care professionals in the setting of a pandemic.

Methods

This rapid review and guideline was developed using a process described elsewhere.17 Briefly, the AGA process for developing clinical practice guidelines uses the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework and best practices as outlined by the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) and Guidelines International Network.18

Information Sources and Literature Search

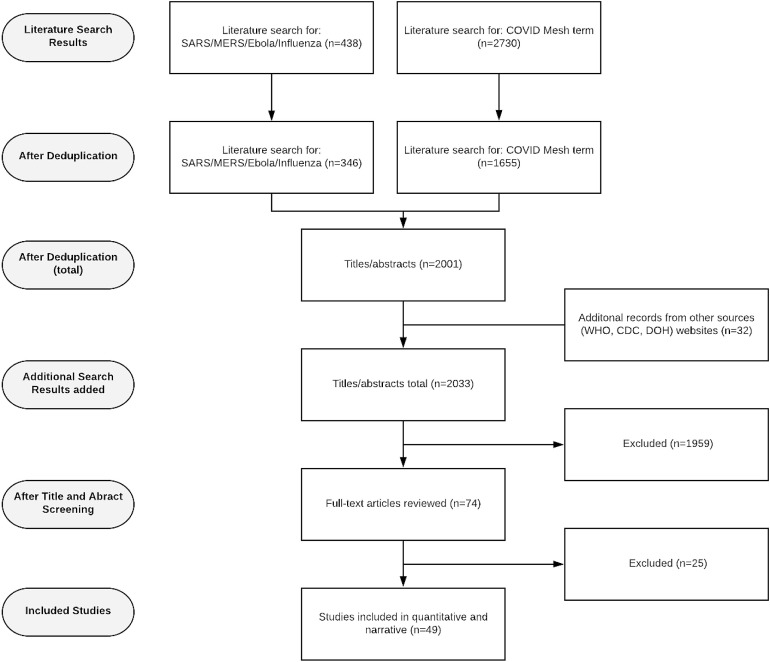

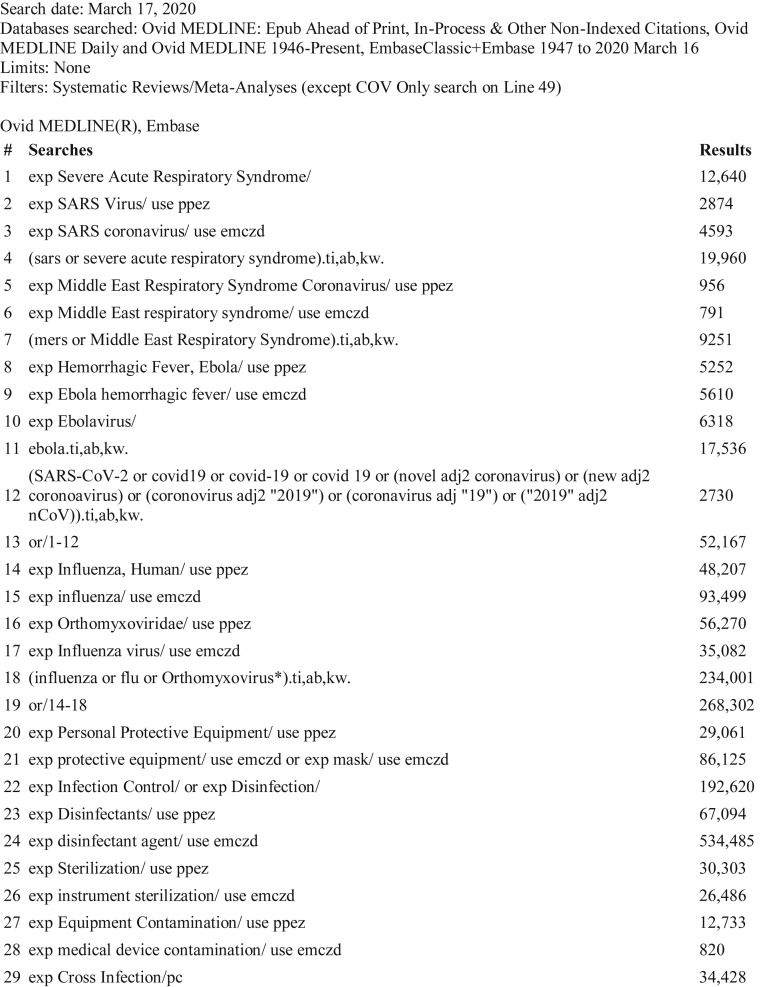

With the help of an information specialist, we electronically searched OVID Medline to identify all relevant English studies from inception to March 23, 2020 (including randomized controlled trials, observational studies, and cases series) related to COVID-19 using the newly developed Medical Subject Headings term. Additionally, we looked for indirect evidence related to SARS, MERS, Ebola, and influenza using the systematic review filter. The reference lists of relevant articles were scanned for additional studies. See Supplementary Figure 1 for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram and Supplementary Figure 2 for the search strategy.

Supplementary Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of included studies. DOH, Department of Health.

Supplementary Figure 2.

Search strategy.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

One reviewer (S.S.) screened titles and abstracts and retrieved relevant articles for each question. A second reviewer (O.A., P.D., J.F., or S.M.S.) confirmed the selected studies and, in certain circumstances, conducted additional Google scholar searches to identify relevant articles. The WHO and CDC websites were also reviewed for relevant articles. Pairs of reviewers extracted the data from the primary studies identified from existing systematic review documents, reviewed the judgments for risk of bias, and conducted specific subgroup analyses using Review Manager software, version 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, 2014).

Certainty in the Evidence

Evidence profiles were used to display the summary estimates as well as the judgments about the overall certainty of the body of evidence for each clinical question across outcomes. Within the GRADE framework, evidence from randomized controlled trials starts as high-certainty evidence and observational studies start as low-certainty evidence, but can be rated down for the following reasons: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. Additionally, evidence from well-conducted observational studies starts as low-certainty evidence but can be rated up for large effects or dose-response. Judgments about the certainty were determined via videoconference discussion to achieve consensus. The certainty of evidence was categorized into 4 levels ranging from very low to high (Table 1 ). For each question, an overall judgment of certainty of evidence was made based on critical outcomes.

Table 1.

Interpretation of the Certainty in Evidence of Effects Using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Framework

| Certainty level | Description |

|---|---|

| High | We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. |

| Moderate | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. |

| Low | Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. |

| Very Low | We have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect |

Evidence to Decision Considerations

During online communications and conference calls, the Guideline Panel developed several recommendations based on the following elements of the GRADE evidence to decision framework: certainty of the evidence, balance of benefits and harms, assumptions about values and preferences, and resource implications. For each guideline statement, the strength of the recommendation and the certainty of evidence to support the recommendation are provided. The phrase “the AGA recommends” is used for strong recommendations, and “the AGA suggests” is used for conditional recommendations (Table 2 ). The Panel deliberated about the impact of resource limitations on the feasibility and implementation of these recommendations. Therefore, the panel’s main recommendations assume an ideal scenario where there are no resource constraints. However, for settings in which resources require rationing, additional guidance is also provided.

Table 2.

Interpretation of Strong and Conditional Recommendationsa Using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Framework

| Implications | Strong recommendation | Conditional recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| For patients | Most individuals in this situation would want the recommended course of action and only a small proportion would not. | The majority of individuals in this situation would want the suggested course of action, but many would not. |

| For clinicians | Most individuals should receive the intervention. Formal decision aids are not likely to be needed to help individuals make decisions consistent with their values and preferences. | Different choices will be appropriate for individual patients consistent with his or her values and preferences. Use shared decision-making. Decision aids may be useful in helping patients make decisions consistent with their individual risks, values, and preferences. |

| For policy-makers | The recommendation can be adapted as policy or performance measure in most situations | Policy-making will require substantial debate and involvement of various stakeholders. Performance measures should assess whether decision-making is appropriate. |

Strong recommendations are indicated by statements that lead with “we recommend” and conditional recommendations are indicated by statements that lead with “we suggest.”

Low confidence in effect estimates can rarely be tied to strong recommendations. Within the GRADE framework, there are 5 paradigmatic situations in which strong recommendations may be warranted despite low or very low certainty of evidence.19 These situations can be conceptualized as those in which there are clear benefits in the setting of a life-threatening situation, clear catastrophic harms, or equivalence between 2 interventions with clear harms for 1 of the alternatives. The Panel invoked these paradigmatic situations in developing these recommendations.

Update

Recommendations in this document may not be valid in the near or immediate future. We will conduct periodic reviews of the literature and monitor the evidence to determine whether recommendations require modification. Based on the rapidly evolving nature of this pandemic, this guideline will likely need to be updated within the next few months.

Results

What Are the Gastrointestinal Manifestations of COVID-19?

Guan et al20 published the largest cohort study to date, which included 1099 hospitalized patients from China with confirmed COVID-19 infection. They reported that 5.0% of COVID-19–infected patients had nausea or vomiting and 3.8% had diarrhea. Across the different published cohort studies, 2.0%–13.8% of patients had diarrhea, 1.0%–10.1% had nausea or vomiting, and 1 study reported the presence of abdominal pain in 2.2% of patients. The cohorts ranged in size from 13 to 191 patients, primarily from Hubei Province, China.1 , 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 Most recently, Pan et al11 reported in a cross-sectional study of 204 COVID-19–positive patients from 3 hospitals in Hubei Province, that 29 patients (14.3%) developed diarrhea, 8 patients (3.9%) experienced vomiting, and 4 patients (2.0%) had abdominal pain. A recent meta-analysis of 4243 patients from China suggested that approximately 17.6% of patients had any GI symptom, including 9.2% with pain, 12.5% with diarrhea, and 10.2% with nausea/vomiting.28 A concern with many of the published studies is the possible duplicate inclusion of the patients across reports, thereby limiting valid performance of pooled estimates in a meta-analysis.29

There is evidence for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in stool specimens independent of the presence of diarrhea. Some studies showed that stool continued to be positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA even after respiratory samples became negative.12 , 15 , 21 , 30, 31, 32, 33 Chen et al32 reported a case of COVID-19 based on compatible symptoms and lung imaging in a patient with positive stool real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction for SARS-CoV-2 RNA, but negative pharyngeal swabs and sputum samples. Furthermore, Wang et al30 reported confirmation of SARS-CoV-2–positive fecal samples in 2 patients without diarrhea.

What Are the Liver Manifestations of COVID-19?

Liver injury is estimated to occur in up to 20%–30% of patients at the time of diagnosis with SARS-CoV-2 infection.14 Severe hepatitis has been reported but liver failure appears to be rare.21 The pattern of liver injury appears to be predominantly hepatocellular, and the etiology remains uncertain but may represent a secondary effect of the systemic inflammatory response observed with COVID-19, although direct viral infection and drug-induced liver injury cannot be excluded. One study of liver biopsy specimens obtained from a patient with COVID-19 revealed microvesicular steatosis and mild lobular and portal activity suggestive of either SARS-CoV-2 infection or drug-induced liver injury.34 Abnormal liver enzymes may be observed in both adults and children with COVID-19,35 and do not appear to be a major predictor of clinical outcomes.15 Early studies have multiple methodologic limitations, with variable laboratory thresholds, limited longitudinal assessment of liver enzymes, heterogeneous evaluation for alternative etiologies, and limited information regarding baseline liver diseases and confounding variables. Additional studies are needed to further characterize the unique clinical considerations for SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with chronic liver disease and/or cirrhosis,36 although preliminary guidance was provided by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases on March 23, 2020.37

What Are the Potential Risks to Health Care Workers Performing Endoscopy?

SARS-CoV-2 is presumed to spread primarily via respiratory droplets from talking, coughing, sneezing, and close contact with symptomatic individuals. However human-to-human transmission can occur from unknown infected persons (eg, asymptomatic carriers or individuals with mild symptoms), as well as individuals with virus shedding during the pre-incubation period before symptoms develop.38

Data related to the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the early phase of the pandemic have confirmed that health care professionals are at higher risk of infection than the general population. The WHO and Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported infection of 2055 health care workers as of February 20, 2020 during the index outbreak in Hubei Province, with health care workers facing a rate of infection approximately 3 times that of the general population.39 This prompted the Chinese Department of Health Reform to deploy more than 40,000 additional health care workers to the region, preserve personal protective equipment (PPE), and implement surveillance measures and quarantine protocols.39 Such measures appear to have slowed the spread to health care workers, with recent cases primarily attributable to household contacts rather than occupational exposure. Similar trends have been observed in Europe, with an estimated 20% of COVID-19 infections in Italy occurring in health care workers.40 Preliminary reports in the United States also suggest that health care workers are at risk of nosocomial infections, including infection of 20 health care workers among the first 67 COVID-19–positive individuals in Philadelphia, PA, and additional health care workers cases in Washington, New York, and Massachusetts.41, 42, 43

The spread of disease via health care workers is concerning for the following reasons: appropriate PPE may not be utilized effectively, especially when COVID-19 patients cannot be identified quickly; shortage of health care workers due to infection and/or quarantine; and the concern of the role of infected health care workers to act as a vector for transmission to patients.

While COVID-19 is spread primarily through droplet transmission, endoscopic procedures can lead to aerosolization and subsequent airborne transmission. Currently, there is significant debate about the type of PPE that should be worn by health care workers involved with endoscopy.

What Kinds of Personal Protective Equipment Are Needed During Endoscopy?

This section outlines a series of recommendations addressing PPE recommendations for GI endoscopy personnel in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. We review the evidence on masks (surgical masks, N95s, or respirator masks), gloves (single vs double), and type of rooms (eg, negative pressure) that should be utilized when performing endoscopy. All recommendations are included in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Executive Summary of Recommendations

| Variable | Recommendation statements | Strength of recommendation and certainty of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Masks | In health care workers performing upper GI procedures, regardless of COVID-19 status,a the AGA recommends use of N95 (or N99, or PAPR) instead of surgical masks, as part of appropriate PPE. | Strong recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence |

| In health care workers performing lower GI procedures regardless of COVID-19 status,a the AGA recommends the use of N95 (or N99 or PAPR) masks instead of surgical masks as part of appropriate PPE. | Strong recommendation, low certainty of evidence | |

| In health care workers performing upper GI procedures, in known or presumptive COVID-19 patients, the AGA recommends against the use of surgical masks only, as part of adequate PPE. | Strong recommendation, low certainty of evidence | |

| Gloves | In health care workers performing any GI procedure, regardless of COVID-19 status, the AGA recommends the use of double gloves compared with single gloves as part of appropriate PPE. | Strong recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence |

| Negative-pressure rooms | In health care workers performing any GI procedures with known or presumptive COVID-19, the AGA suggests the use of negative-pressure rooms over regular endoscopy rooms when available. | Conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence |

| Endoscopic disinfection | For endoscopes utilized on patients regardless of COVID status, the AGA recommends continuing standard cleaning endoscopic disinfection and reprocessing protocols. | Good practice statement |

| Triage | All procedures should be reviewed by trained medical personnel and categorized as time-sensitive or not time-sensitive as a framework for triaging procedures. | Good practice statement |

| In an open access endoscopy system where the listed indication alone may provide insufficient information to make a determination about the time-sensitive nature of the procedure, consideration should be given for the following options: a telephone consultation with the referring provider or a telehealth visit with the patient or a multidisciplinary team approach to facilitate decision-making for complicated patients. | Good practice statement |

These recommendations assume the absence of widespread reliable rapid testing for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection or immunity.

Aerosol-generating procedures

Aerosol-generating procedures—procedures that generate small droplet nuclei in high concentrations and permit airborne transmission—include upper GI endoscopic procedures, such as esophagogastroduodenoscopy, small bowel enteroscopy, endoscopic ultrasound, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, breath tests, and esophageal manometry. Aerosolization of viral particles may occur during insertion of the scope into the pharynx during intubation, as well as during insertion and removal of instruments through the endoscope channel.44, 45, 46, 47 The risk of aerosolization of viral particles during lower GI procedures, such as colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and anorectal manometry, has been less well studied.

COVID-19 status of patients during community spread

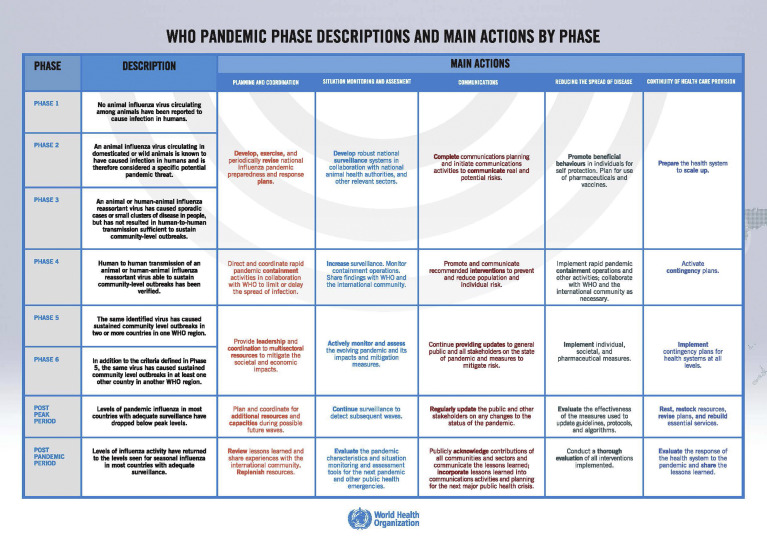

As outlined by the WHO, phases 5 and 6 of a pandemic refer to sustained community outbreaks at a global level with human-to-human transmission.48 Once community spread has been established in these pandemic phases and there is documentation of spread via asymptomatic individuals, prescreening checklists have limited utility. Additionally, given the currently limited COVID-19 testing in the United States, individuals at risk of spreading disease cannot be easily identified.38 Our panel acknowledges that recommendations may change if rapid testing is available, and GI patients can be tested before undergoing procedures. However, all patients undergoing endoscopy should be considered potentially infected or capable of infecting others.

Description of masks

Surgical masks (also known as medical masks) are used often for droplet precautions, as they are designed to block large particles, but are less effective in blocking smaller particle aerosols (<5 μm). Unlike surgical masks, respirator masks are designed to block aerosols. Respiratory protection in health care for airborne precautions commonly follows 2 filtering device paths, N95 mask respirators and powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs). The N95 masks filter at least 95% of aerosols (<5 μm) and droplet-size (5–50 μm) particles and are not resistant to oil. Lightweight, no-hose, PAPRs are a highly effective alternative to face masks. Air is forced through a large, multilayer filter housed in the helmet and provide positive pressure within the face-shield compartment. These devices are approved by US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Hazard and can provide high-level protection from common airborne viruses that exceed N95 face masks without the need for “fit-testing” and have been used in a variety of settings.49 PAPR also has the advantage of providing head and neck protection (Figures 1 and 2 ).

Figure 1.

Surgical masks and N95 masks.

Figure 2.

PAPR mask.

Description of negative pressure rooms

Airborne isolation rooms utilize negative-pressure ventilation to create inward directional airflow to prevent generated aerosols from diffusing outside the room. The door of the room should remain closed except when entering and leaving. An anteroom that contains another sink separates the isolation room and the hallways. The anteroom is utilized to transition patients and health care workers in and out of the room, for storage of PPE and for donning and doffing of PPE. The negative pressure rooms are designed to maintain a pressure differential and airflow differential between the isolation room and the anteroom, in addition to a minimum number of air changes per hour.50

Masks for Health Care Workers During Endoscopy

Recommendation 1: In health care workers performing upper GI procedures, regardless of COVID-19 status,∗ the AGA recommends use of N95 (or N99 or PAPR) masks instead of surgical masks as part of appropriate PPE (Strong recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence)

Recommendation 2: In health care workers performing lower GI procedures, regardless of COVID-19 status,∗ the AGA recommends the use of N95 (or N99 or PAPR) masks instead of surgical masks as part of appropriate PPE. (Strong recommendation, low certainty of evidence)

Recommendation 3: In health care workers performing any GI procedure in known or presumptive COVID-19 patients, the AGA recommends against the use of surgical masks only as part of adequate PPE. (Strong recommendation, low certainty of evidence)

∗These recommendations assume the absence of widespread reliable and accurate rapid testing for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection or immunity.

Summary of the Evidence

Our systematic literature search did not identify any studies that provided direct evidence to inform our clinical questions for PPE in COVID-19. However, several studies from the SARS outbreak were identified that provide indirect evidence. The SARS outbreak reinforced the vital role of PPE in protecting health care workers from occupationally acquired infection. We used data from 2 existing systematic reviews by Offeddu et al51 and Tran et al52 to inform our recommendations. First, the systematic review by Offeddu et al included a meta-analysis of 3 observational studies that showed a benefit in using N95 respirators over standard masks in protecting health care workers from SARS (odds ratio [OR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.22–3.33), with corresponding risk ratios (RRs) of 0.88 (95% CI, 0.26–2.27) and 0.94 (95% CI, 0.41–1.34) under baseline risks of 20% and 60%, respectively (although the results were imprecise).

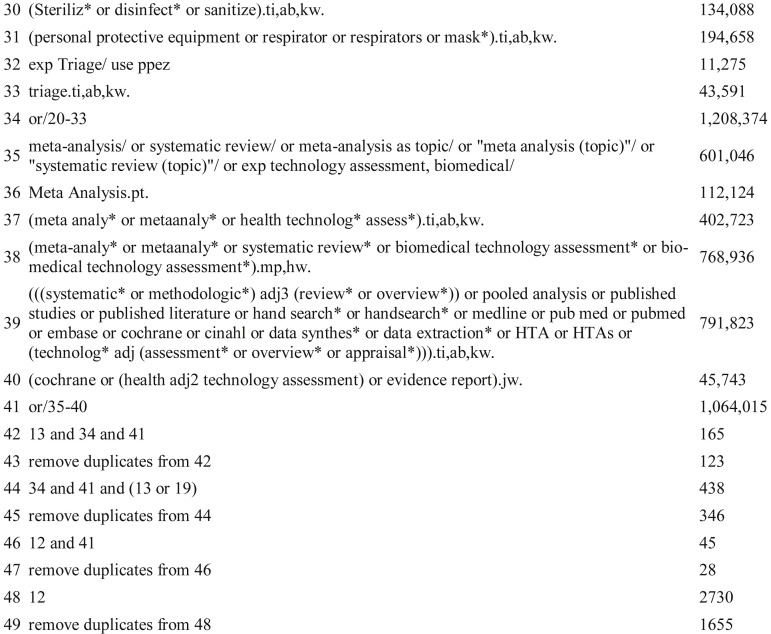

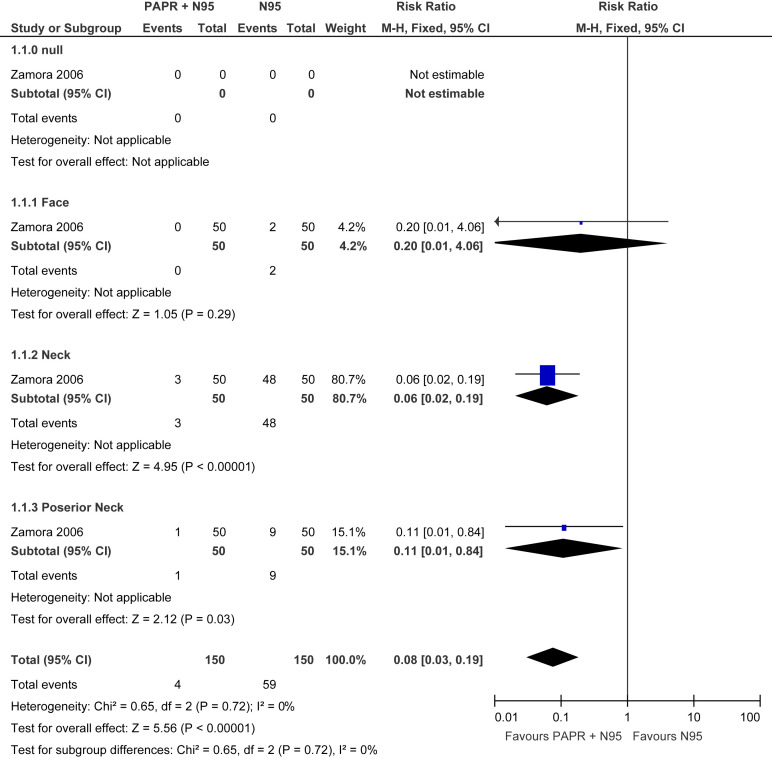

Data from 3 randomized controlled trials demonstrated a reduction in laboratory-confirmed viral infections from coronavirus species, although the results were imprecise (RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.54–1.14). See evidence profile in Table 4 . In addition, there was a strong association between use of N95 respirators (compared to no masks) and protection from SARS infection in health care workers (OR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.06–0.26). See evidence profile in Table 5 . Second, a systematic review from Tran et al52 revealed an increased risk of viral transmission in health care workers performing aerosol-generating procedures (mostly bronchoscopy or tracheal intubation) (Supplementary Figure 3). Zamora et al53 investigated the amount of contamination on the neck and face from individuals using a PAPR mask (in combination with N95) compared with an N95 mask alone. Individuals who used the PAPR-based strategy experienced a lower risk of face and neck contamination compared to N95 mask alone (RR, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.03–0.19) (see evidence profile in Table 6 , Supplementary Figure 4). Limitations of these studies include small numbers of health care workers and data on tracheal intubation or bronchoscopy, not GI endoscopy.

Table 4.

Evidence Profile: N95 Compared to Surgical Masks for COVID-19 Prevention for Gastrointestinal Upper Endoscopic Procedures

| Infection | Certainty assessment |

Patients, n (%) |

Effect, OR (95% CI) |

Certainty | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | N95 | Surgical masks | Relative | Absolute | ||

| SARS | 3 | Observational studies | Seriousa | Not serious | Not seriousb | Seriousc | None | 4/141 (2.8) | 24/452 (5.3) | 0.86 (0.22 to 3.33) | 7 fewer per 1000 (41 fewer to 104 more) | □◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

| Viral respiratory | 3 | Randomized trials | Not seriousd | Not serious | Seriouse | Seriousc | None | 48/1740 (2.8) | 52/1274 (4.1) | 0.78 (0.54 to 1.14) | 9 fewer per 1000 (18 fewer to 5 more) | □□◯◯ LOW |

Concern for recall bias.

Although studies are on SARS population, given the similarities in the virus we did not rate down for indirectness.

Low event rate and crosses the clinical threshold.

Although the compliance to the assigned mask type was self-reported and is not clear if there is a performance, bias study staff was doing regular checks on the study participants to control for performance bias, thus, we did not rate down for risk of bias.

Not only coronaviruses but other upper respiratory infection viruses.

Table 5.

Evidence Profile: N95 Compared to No Personal Protective Equipment for COVID-19 Prevention for Gastrointestinal Upper Endoscopic Procedures

| Infection | Certainty assessment |

Patients, n (%) |

Effect, OR (95% CI) |

Certainty | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | N95 | no PPE | Relative | Absolute | ||

| SARS | 5 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not seriousa | Not serious | Strong association | 9/163 (5.5) | 86/234 (36.8) | 0.12 (0.06 to 0.26) | 302 fewer per 1000 (334 fewer to 236 fewer) | □□□◯ MODERATE |

Although studies are on SARS population, given the similarities in the virus we did not rate down for indirectness.

Supplementary Figure 3.

Forest plot. Exposed vs unexposed health care workers to tracheal intubation as a risk factor for SARS transmission from systematic review by Tran et al.52 M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Table 6.

Evidence Profile: Powered Air-Purifying Respirators (+N95) vs N95 in Health Care Workers During Gastrointestinal Procedures

| Variable | Certainty assessment |

Patients, n (%) |

Effect, RR (95% CI) |

Certainty | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | PARP | N95 | Relative | Absolute | ||

| Efficiency in particulate air | 1 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousa | None | High-efficiency particulate air filters filter at least 99.97% of particles 0.3 μm in diameter, compared to N95 masks that filter at least 95% of aerosol (<5 μm) | □□□◯ MODERATE | |||

| Contaminated areas on face and neck | 1 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Very seriousb | None | 4/150 (2.7) | 59/150 (39.3) | 0.08 (0.03 to 0.19) | 362 fewer per 1000 (382 fewer to 319 fewer) | □□◯◯ LOW |

Only 1 study.

Very small number of events.

Supplementary Figure 4.

Forest plot. PAPR +N95 vs N95 in reducing contamination of health care workers. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Discussion and Rationale

To estimate the risk of viral transmission in endoscopic procedures, we examined data evaluating non-GI aerosolizing-generating procedures, such as bronchoscopy and tracheal intubation. Our search strategy did not yield comparative studies on the degree of aerosolization with upper or lower GI endoscopy compared with bronchoscopy or tracheal intubation. However, we assume that insertion of the endoscope into the pharynx and esophagus is likely to be associated with a similar risk of aerosolization of respiratory droplets to that of bronchoscopy.

To inform our estimate of the risk of infection for individuals performing endoscopy, we used evidence from the review by Tran et al,52 which examined the risk of respiratory infections among health care workers from aerosol-generating procedures. We conducted an original meta-analysis of retrospective cohort studies identified in this review. The data revealed a higher risk of viral transmission to health care workers exposed to aerosol-generating procedures compared to unexposed health care workers (RR, 4.66; 95% CI, 3.13–6.94). Therefore, we recommend utilizing N95s (or masks that are equivalent or better) for all patients regardless of COVID-19 status, given higher risk of transmission during aerosol-generating procedures.

Finally, the Panel’s decision to extend this recommendation to all patients, regardless of COVID-19 status, is specifically in the context of documented community spread during a pandemic. It also assumes a small proportion of persons who are negative or have recovered from COVID-19; this may change with the availability of wider testing and the ability to test for past infection or immunity. Recent data from China, by Chang et al,54 revealed the greatest risk of COVID-19 exposure to health care workers during early stages of the pandemic when testing was not yet widely available. In a JAMA report published from Zhongnan Hospital in Wuhan, 29.3% (40 of 138) of COVID-19–infected patients were health care workers who presumably had hospital-acquired infections.25 Among 493 health care workers caring for hospitalized patients, 10 became infected with COVID-19; all 10 were unprotected health care workers (no mask) caring for patients on medical wards with a low risk of exposure (no known or suspected COVID-19 patients). In contrast, none of the 278 protected (with N95 mask) health care workers caring for high-risk patients (known or suspected COVID-19) became infected (adjusted OR, 464.82; 95% CI, 97.73 to infinite).55 One study evaluating health care worker exposure in the care of 1 COVID-19–positive patient revealed that none of 41 health care workers (surgical masks only) developed infection despite absence of N95 mask, although studies evaluating health care workers in context of larger cohorts of COVID-19–positive patients are not yet available.56

The decision to extend the recommendation to lower GI procedures is based on evidence of possible aerosolization during colonoscopy, especially during the insertion and removal of instruments through the biopsy channel,46 and the uncertain risks associated with evidence of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in fecal samples. These data provided indirect evidence to extend the recommendation to lower GI procedures pending more definitive evidence.30

Limited Resource Settings

Recommendation 4: In extreme resource-constrained settings involving health care workers performing any GI procedures, regardless of COVID-19 status, the AGA suggests extended use/reuse of N95 masks over surgical masks, as part of appropriate PPE. (Conditional recommendation, very low certainty evidence)

Summary of the Evidence

No direct evidence on the prolonged use or reuse of N95, N99, or PAPR masks in a COVID-19 pandemic was identified. We also did not find indirect comparative evidence on any mask reuse strategies that would impact infection rates and subsequent morbidity and mortality of health care workers. Furthermore, there were no studies on aerosol-generating procedures in context of SARS or MERS. The available evidence was limited to low-quality reports evaluating N95 protection in combination with face shield or surgical mask, mathematical models, experimental studies examining decontamination strategies for PPE preservation during pandemics, and laboratory tests evaluating durability and fit endurance of respirator masks.

CDC recommendations during H1N1 pandemic included guidance to use a cleanable face shield or surgical mask over the N95 respirator to reduce contamination and extend respirator use.57 These strategies were utilized during the SARS outbreak, but the effects of prolonged use of a combination of a face shield or surgical mask over an N95 mask have not been reported.58 During the H1N1 pandemic, an estimated 40% or more of health care workers reported reuse of their N95 respirator but no data are available to estimate the impact on influenza infections.59 , 60 A mathematical model to calculate the potential influenza contamination of facemasks from aerosol sources in various exposure scenarios revealed that the amount of exposure in a single cough (≈19 viruses) is much lower than that transmitted from aerosols (4473 viruses on N95 masks and 3476 viruses on surgical masks).61 Finally, in laboratory testing, an estimated 5 consecutive donnings of PPE can be performed before fit factors consistently drop to unsafe levels.39 In addition, in experiments examining decontamination of N95 with hydrogen peroxide and mechanical testing, up to 50 cycles of exposure to hydrogen peroxide did not lead to any degradation of the filtration media, but the elastic straps were stiffer after exposure to up to 20 cycles and this could impair proper fit.62 See evidence profile in Tables 7 and 8 . The data on PAPR reuse after cleaning and disinfection were also limited with select institutions reporting on their experience with established PAPR programs and instructions for cleaning.63

Table 7.

Evidence Profile: Reuse of N95 Compared to Surgical Masks for Health Care Workers During Gastrointestinal Procedures

| Variable | Certainty assessment |

Impact | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Study design | Certainty | ||

| Infection with COVID-19 | 8 | Anecdotal reports Experiments under laboratory conditions |

□◯◯◯ VERY LOWa,b,c |

No direct evidence was found with regard to the safety of reuse of masks (surgical masks [SMs] and N95) during a COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, indirect evidence from other pandemic outbreaks did not reveal empiric data on infection rates, but rather reports of anecdotal experience or experiments under laboratory conditions or mathematical models. Anecdotal reports on using SMs over N95 as a barrier to pathogens and extend the useful life of the N95 respirator has been published.58 This was sparingly utilized during the SARS outbreak, but the effects of prolonged use of this combination on health care workers and the infection rate have not been reported. Similarly, reports exists that >40% of health care workers reused their N95 during the H1N1 pandemic.59,60 Furthermore, a mathematical model to calculate the potential influenza contamination of facemasks from aerosol sources in various exposure scenarios, showed that single coughs (≈19 viruses) were much less than likely levels from aerosols (4473 viruses on filtering facepiece respirators and 3476 viruses on SMs).61 In laboratory testing, it has been reported that 5 consecutive donnings can be performed before fit factors consistently drop to unsafe levels.62 In addition, decontamination of N95 with hydrogen peroxide has showed that exposure up to 50 cycles does not degrade the filtration media and mechanical testing but has demonstrated that the elastic straps were stiffer after exposure to up to 20 hydrogen peroxide vapor cycles. Thus, more than 20 cycles can impair proper fit.63 There have been narrative reports, news conference reports, and the CDC recommendation90 during H1N1 pandemic suggesting use of a cleanable face shield or surgical mask to reduce N95 respirator contamination.57 |

Risk of bias: There is no comparator with optimal PPE to understand the risk of the acceptable protection from COVID-19.

There are multiple layers of indirectness. The population is different—studies were done on influenza virus or simulation studies on healthy participants, and there are no studies on aerosol generating procedures (AGP). Outcome is indirect as well; most of these studies have tolerability of the mask or laboratory testing as outcomes.

Unable to assess for imprecision because outcome cannot be measured.

Table 8.

Evidence Profile: Prolonged Use of N95 Compared to Surgical Masks for Health Care Workers During Gastrointestinal Procedures as a Last Resort in Resource-Limited Settings

| Variable | Certainty assessment |

Impact | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Study design | Certainty | ||

| Infection with COVID-19 | 4 | Anecdotal reports Experiments under laboratory conditions |

□◯◯◯ VERY LOWa,b,c |

No direct evidence was found with regard to the safety of extended use of masks (surgical masks [SMs] and N95) during a COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, indirect evidence from other pandemic outbreaks did not reveal empiric data on infection rates, but rather reports of anecdotal experience or experiments under laboratory conditions or mathematical models. Experiment on tolerability of the N95 with prolonged use on health care workers showed that health care workers were able to tolerate the N95 for 89 of 215 (41%) total shifts of 8 hours. Other 59% mask was discarded before 8 hours because it became contaminated or intolerance.91 Furthermore, a mathematical model to calculate the potential influenza contamination of facemasks from aerosol sources in various exposure scenarios, showed that single coughs (≈19 viruses) were much less than likely levels from aerosols (4473 viruses on filtering facepiece respirators and 3476 viruses on SMs).61 Additionally, there was a survey on health care workers during H1N1 pandemic and >40% of the health care workers were reusing or had a prolong use on their N95.59,60 |

Risk of bias: There is no comparator with optimal PPE to understand the risk of the acceptable protection from COVID-19.

There are multiple layers of indirectness. The population is different—studies were done on influenza virus or simulation studies on healthy participants, and there are no studies on AGP. Outcome is indirect as well; most of these studies have tolerability of the mask or laboratory testing as outcomes.

Unable to assess for imprecision because outcome cannot be measured.

Discussion and Rationale

There is insufficient evidence to comment on the safety of reuse (up to 5 consecutive donnings) and extended use (over 8 hours) of masks and other PPE. Limited indirect evidence suggests loss of durability and fit of N95 masks under these conditions. With regard to PAPRs with disposable protective shields, the protective shields may be disinfected with standard biocidal-containing wipes and reused. However, no evidence of safety of such an approach was identified.

Gloves During COVID-19

Recommendation 5: In health care workers performing any GI procedure, regardless of COVID-19 status, the AGA recommends the use of double gloves compared with single gloves as part of appropriate PPE. (Strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence)

Summary of the Evidence

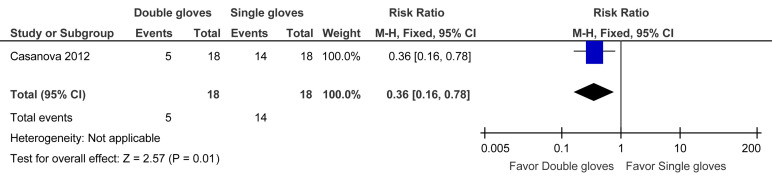

The evidence to support this recommendation is largely derived from observations of health care workers during the SARS epidemic in 2003. Transfer of organisms from contaminated PPE to hands or clothing may contribute to infection of health care workers and associated contacts. Casanova et al64 performed a human challenge study using the bacteriophage MS2 for simulated droplet contamination. One group of participants donned a full set of PPE with 1 pair of gloves. The second group donned identical PPE with 2 pairs of Latex gloves. The first (inner) pair of gloves was applied so that the wrist of the glove was under the elastic cuff at the wrist of the gown sleeve. The second (outer) pair, one size larger, was worn over the first pair so that the wrist of the glove was positioned over the gown sleeve. During the doffing phase, the inner pair of gloves was removed last. The double-glove strategy was associated with less contamination than the single-glove strategy (RR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.16–0.78). See evidence profile in Table 9 and Supplementary Figure 5.

Table 9.

Evidence Profile: Double Gloves Compared to Single Gloves for Health Care Workers During Gastrointestinal Procedures

| Variable | Certainty assessment |

Patients n (%) |

Effect, RR (95% CI) |

Certainty | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Double gloves | Single gloves | Relative | Absolute | ||

| Contamination | 1 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not seriousa | Seriousb | None | 5/18 (27.8) | 14/18 (77.8) | 0.36 (0.16 to 0.78) | 498 fewer per 1000 (653 fewer to 171 fewer) | □□□◯ MODERATE |

Study was done with the bacteriophage MS2, but the drops size was similar to SARS and COVID-19 to simulate droplet contamination, so we decided not to rate down. We recognize that there is some indirectness but we also took into account the large effect size.

Low event rate.

Supplementary Figure 5.

Forest plot. Double gloves compared to single gloves for prevention of contamination. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Discussion and Rationale

The Casanova et al64 study highlights the importance of double gloving as part of the doffing process for PPE with either N95 mask or PAPR to minimize contamination and reduce the risk of viral transmission.

Negative-Pressure Room During COVID-19

Recommendation 6: In health care workers performing any GI procedure, with known or presumptive COVID-19, the AGA suggests the use of negative-pressure rooms over regular endoscopy rooms, when available. (Conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence)

Summary of the Evidence

We did not find any direct evidence to inform this recommendation but indirect evidence was identified to confirm the viability of coronaviruses as an aerosol. In an experimental model, van Doremalen et al65 demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 could remain viable in aerosol form for up to 3 hours, similar to what has been previously reported for the SARS-CoV-1 virus. Epidemiologic and airflow dynamics modeling studies from the SARS 2003 and MERS-CoV outbreaks additionally support airborne spread.66, 67, 68 As GI procedures may generate aerosols, indirect evidence to support the viability of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in aerosols and airborne transmission support a recommendation in favor of preferential use of negative pressure rooms pending further evidence.

Discussion and Rationale

The experimental study by van Doremalen et al65 further demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 may stay viable on copper surfaces up to 4 hours, on cardboard surfaces up to 24 hours, and on plastic and stainless steel surfaces up to 72 hours.65 These data combined with the available epidemiologic and airflow dynamics studies of related coronavirus infections suggest that GI procedures may contribute to nosocomial transmission of COVID-19. Thus, the use of negative-pressure rooms with anterooms may mitigate the spread of the infection within health care facilities. The Panel acknowledges that the use of a negative-pressure room may impact efficiency and procedural workflow, but anticipate that GI procedures performed during the initial pandemic phase will be predominantly limited to time-sensitive procedures performed in hospitalized settings.

In limited-resource settings where negative-pressure rooms are unavailable, portable industrial-grade high-efficiency particulate air filters may be a reasonable alternative. Industrial-grade high-efficiency particulate air filters are alternatives suggested by the CDC to enhance filtration when air supply systems are not optimal, when anterooms are not available for patients in airborne isolation rooms, and during intubation and extubation of patients with active tuberculosis patients.50 , 69

Endoscopic Decontamination During COVID-19

Recommendation 7: For endoscopes utilized on patients regardless of COVID-status, the AGA recommends continuing standard cleaning endoscopic disinfection and reprocessing protocols. (Good practice statement)

Summary of the Evidence

Current guidelines for infection control during GI endoscopy include mechanical and detergent cleaning, followed by high-level disinfection, rinsing and drying through sterilization, using US Food and Drug Administration–approved liquid chemical germicide solutions.70 Cleaning must precede high-level disinfection to remove any organic debris (eg, blood, feces, and respiratory secretions) from the external surface, lumens, and channels of flexible endoscopes. Studies examining the natural bioburden levels detected on flexible GI endoscopes show ranges from 105 CFU/mL to 1010 CFU/mL after clinical use; appropriate cleaning followed by high-level disinfection (a process that eliminates or kills all vegetative bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, and viruses, except for small numbers of bacterial spores) reduces the number of microorganisms and organic debris by 4 logs, or 99.99%.71 Studies examining the risk of viral transmission of hepatitis B or C or human immunodeficiency virus among patients have demonstrated a very low risk of transmission.72 Several cases of patient-to-patient hepatitis C virus transmission have been reported, but these were related to inadequate cleaning and disinfection of GI endoscopes and accessories and/or the use of contaminated anesthetic vials or syringes. A recent review by Kampf et al73 reported effective inactivation of coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV, by standard biocidal agents, which are active ingredients in current endoscopic disinfecting solutions (Table 10 ).

Table 10.

Biocidal Agents Against SARS-CoV

| Studya | Biocidal agent | Exposure time | Efficacy (reduction of viral infectivity by log10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rabenau, 200592 | 95% Ethanol | 30s | ≥5.5 |

| 85% Ethanol | 30s | ≥5.5 | |

| 80% Ethanol | 30s | 4.3 | |

| Rabenau, 200593 | 78% Ethanol | 30s | ≥5.0 |

| 100% 2-Propanol | 30s | ≥3.3 | |

| 70% 2-Propanol | 30s | ≥3.3 | |

| 45% and 30% 2-Propanol | 30s | ≥4.3 | |

| 1% Formaldehyde | 2 min | >3.0 | |

| 0.7% Formaldehyde | 2 min | >3.0 | |

| 0.5% Glutardialdehyde | 2 min | >4.0 | |

| Siddharta, 201794 | 75% 2-Propanol | 30s | >4.0 |

Subgroup analysis taken from Kampf, 2020.73

Discussion and Rationale

Decontamination of coronavirus species has been confirmed with commonly used biocidal agents for decontamination, such as hydrogen peroxide, alcohols, sodium hypochlorite, or benzalkonium chloride.73, 74, 75 There are ample data to support continuation of current endoscope decontamination practices in the context of known COVID-19.71 Similar biocidal agents are additionally present in hospital-grade disinfecting wipes commonly used to decontaminate surfaces for endoscopy room cleaning.73

Personal Protective Equipment Implementation Considerations

-

1.

Review and be observed practicing PPE don and doff. Make sure that you have been fitted for an N95. See Figure 3 for donning and doffing of PPE

-

2.

Do not take personal belongings (such as phones, stethoscopes) into any procedural area as these may become contaminated.

-

3.

Minimize the number of personnel in the room during any endotracheal intubation. Only the anesthesia team should remain during intubation if possible.

-

4.

Review and determine the appropriateness of trainee involvement in procedures with consideration of procedural time and PPE supply.

-

5.

Avoid personnel switches during procedures.

-

6.

Consider nursing teams that follow the patient from the pre-procedure area to the procedure room and to the recovery area, to minimize personnel exposure.

-

7.

Consider teams (eg, physician, registered nurse, technician, and anesthesia) that remain together for the entire day so as to compartmentalize and minimize personnel exposure.

-

8.

Nonprocedural personnel should avoid entering any procedure room once a patient has entered.

Figure 3.

(A) Donning and (B) doffing of PPE.

How Should Gastroenterologists Triage Gastrointestinal Procedures?

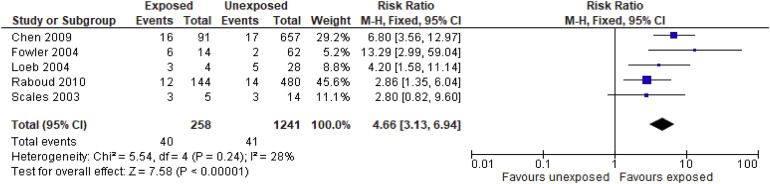

Since the WHO declared COVID-19 a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, US health systems started implementing infection control measures, planning for surge capacity in health care facilities, and proposing triage of health care services (Figure 4 ). The US Surgeon General and the American College of Surgeons recommended suspension of all elective surgical procedures,76 , 77 and on March 15, 2020, a joint society statement by 4 GI organizations recommended that elective nonurgent procedures be rescheduled to mitigate COVID-19 spread and preserve PPE. However, this raises difficult questions about which procedures can be safely postponed.

Figure 4.

WHO phases of a pandemic.

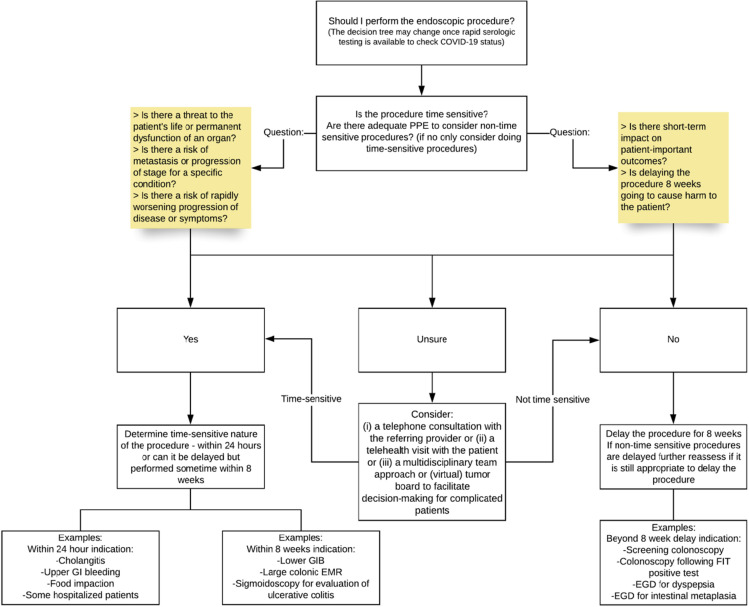

For guidance on how to implement a triage system see Figure 5 .

All procedures should be reviewed by trained medical personnel and categorized as time-sensitive or not time-sensitive using the framework outlined below in Table 11 . (Good practice statement)

In an open access endoscopy system where the listed indication alone may provide insufficient information to make a determination about the time-sensitive nature of the procedure, consideration should be given for the following options: a telephone consultation with the referring provider or a telehealth visit with the patient or a multidisciplinary team approach or (virtual) disease/tumor board to facilitate decision-making for complicated patients. (Good practice statement)

Figure 5.

Flowchart. EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; FIT, fecal immunochemical test; GIB, gastrointestinal bleeding.

Table 11.

Framework for Triage

| Time-sensitivea (within 24 h to 8 wk) | Non–time-sensitive | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Threat to the patient’s life or permanent dysfunction of an organ, eg, diagnosis and treatment of GI bleeding or cholangitis | Risk of metastasis or progression of stage of disease, eg, work up of symptoms suggestive of cancer | Risk of rapidly worsening progression of disease or severity of symptoms, eg, management decisions, such as treatment for IBD | No short-term impact on patient-important outcomes, eg, screening or surveillance colonoscopy, follow up colonoscopy for +FIT |

+FIT, positive fecal immunochemical test; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Time-sensitive procedures are defined as procedures that, if deferred, may negatively impact patient-important outcomes. The decision to defer a procedure should be made on a case-by-case basis.

Summary of the Evidence

Data on the urgency of when to perform GI procedures and complications related to delays on patient important outcomes are sparse. Studies in lower GI bleeding suggest little difference in outcomes, such as blood transfusions or surgery when comparing urgent colonoscopy (<24 hours) vs delayed colonoscopy (up to 72 hours after presentation).78 , 79 In a pandemic setting, one might consider opting to delay the procedure (especially while awaiting COVID-19 testing). In contrast, a patient presenting with an upper GI bleed likely should have an esophagogastroduodenoscopy performed within 24 hours.80 , 81

The impact of delays in diagnosis may also have significant ramifications on immediate management (eg, in question of inflammatory bowel disease diagnosis or treatment) and on cancer treatment decisions (eg, colon cancer and pancreatic cancer). Additionally, tests related to treatment of precancerous lesions may also lead to anxiety among patients and providers (eg, treatment of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s or an endoscopic mucosal resection for a larger colon polyp). Indirect evidence supports that delays of weeks to a few months in some cancer diagnoses may not lead to progression of stage or worse clinical outcomes, even when symptoms are present in some GI cancers.82, 83, 84

Non–time-sensitive procedures are most routine screening and surveillance colonoscopy. There is evidence to suggest that after a positive fecal immunochemical test, a colonoscopy can be delayed up to 6 months without negatively impacting patient outcomes. Corley et al85 reported on 70,124 patients with a positive fecal immunochemical test and found no difference in outcomes of colorectal cancer diagnosis and advanced-stage disease when the colonoscopy was performed 8–30 days after the test vs waiting up to 6 months. However, when delaying 7–9 months there was a nonsignificant increase in risk and a more profound increase risk when delayed more than 12 months. Using data from this study, one could suggest that in patients undergoing colorectal cancer screening, even when a test suggests a possible polyp or cancer, delaying the procedure for some period of time may not be harmful on the population level.85

Discussion/Rationale

In the setting of a pandemic, the limited availability of resources (such as critical shortages of PPE) combined with the risk of potential exposure and spread of infection to patients and the availability of appropriate health care workers, often become the main drivers for provision of health care services. The proposed framework of separating procedures into time-sensitive and non–time-sensitive cases may be useful in determining which procedures, if delayed, may negatively impact on patient-important outcomes. The Panel intentionally chose to focus on patient-important outcomes as a driver for decision-making, acknowledging the difficulties with using specific indications to categorize procedures as elective vs nonelective. The Panel also acknowledged the limitations of the body of evidence in assessing the time-sensitive nature of endoscopic procedures. Although there were data to support a delay of up to 3–6 months for patients undergoing colonoscopy for positive fecal immunochemical test, and this was likely generalizable to patients undergoing colonoscopy for polyp surveillance, the data to support delays for procedures such as endoscopic mucosal resection for large polyps are lacking. Moreover, there may be added issues around patient anxiety or worry and concerns about medicolegal risks that may influence decisions about deferring procedures; therefore, the Panel suggests the use of a multidisciplinary team approach to facilitate decision-making for complicated patients.

Telemedicine also provides an opportunity to communicate with patients and provide continued patient care while reducing risk of exposure to COVID-19 to patients and health care workers. The AGA and a number of other professional medical organizations have been working to lift restrictions on reimbursement for telehealth visits.86

The Panel chose the time period of 8 weeks based on consensus from the group that some procedures require endoscopy within 24 hours, but others are not as time-sensitive and can be delayed in the short-term for a few weeks without affecting important patient outcomes related to the disease state. As there is uncertainty about the duration of the pandemic, a predefined time period should be used for reassessment of all deferred procedures, especially if resources become available and the time-sensitive nature of the procedure changes.

In addition, as innovations in testing (ie, rapid tests and serologic tests of immunity) and treatment or vaccines allow for better risk stratification, one may be able to consider restarting non–time-sensitive procedures.

Public Perspective

The Panel also sought feedback from 2 patients affected by COVID-19 to ensure that we captured the consumer/patient perspective. They understood and agreed with the importance and process of triaging procedures. One patient additionally expressed concerns about the focus on limiting PPE for health care workers when “they are the ones who need the protection the most” and the lack of clear evidence on the variability of GI symptoms.

Conclusions

Clinical guidelines should be informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the desirable and undesirable consequences of alternative care options. Rapid guidelines, typically completed within 1–3 months, are needed to provide guidance in response to a time-sensitive need, such as during a public health emergency.87, 88, 89 Using a rapid guideline process, the AGA aims to provide timely guidance on appropriate PPE and triage of GI endoscopy in context of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Due to the paucity of evidence specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection, many questions regarding clinical management remain unanswered, including implications and clinical considerations for vulnerable populations, such as individuals with inflammatory bowel disease or other autoimmune GI or liver conditions on immunosuppression, patients with cirrhosis or end-stage liver disease, and individuals with GI malignancies requiring systemic chemotherapy. International registries, such as the Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus (COVID-19) Under Research and Exclusion, or SECURE-IBD, (https://covidibd.org), can serve as a valuable data source in the future as clinicians engage in information sharing to inform stronger evidence-based guidance. Ongoing clinical trials for COVID-19 treatment may be associated with GI adverse effects and increase the demands for GI consultative care. Furthermore, the severity and duration of resource limitations for SARS-CoV-2 testing and PPE may further challenge clinical management decisions. Importantly, due to the rapidly evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, these recommendations will likely need to be updated within a short timeframe.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments The authors sincerely thank Kellee Kaulback, Medical Information Officer, Health Quality Ontario, for helping in the literature search for this technical review.

This document represents the official recommendations of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and was developed by the AGA Clinical Guideline Committee and Clinical Practice Update Committee and approved by the AGA Governing Board. Development of this guideline was conducted with no internal funding by the AGA Institute and no additional outside funding.

Expiration Date: 6 months.

Conflicts of interest All members were required to complete the disclosure statement. These statements are maintained at the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) headquarters in Bethesda, Maryland, and pertinent disclosures are published with this report. None of the panel members had any relevant disclosures.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at http://dxdoi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.072.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J. Genomic characterization and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:545–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coronavirus Resource Center Johns Hopkins University of Medicine. http://coronavirus.jhu.edu Available at:

- 5.Stadler K., Masignani V., Eickmann M. SARS—beginning to understand a new virus. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2003;1:209–218. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui D.S., Azhar E.I., Kim Y.J. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: risk factors and determinants of primary, household, and nosocomial transmission. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:e217–e227. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30127-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention [published online ahead of print February 24, 2020. JAMA https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.CDC COVID-19 Response Team Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)–United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR. 2020;69:343–346. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahase E. China coronavirus: WHO declares international emergency as death toll exceeds 200. BMJ. 2020;368:m408. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bedford J., Enria D., Giesecke J. COVID-19: towards controlling of a pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1015–1018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30673-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan L., Mu M., Ren H.G. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients with digestive symptoms in Hubei, China: a descriptive, cross-sectional multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:766–773. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holshue M.L., DeBolt C., Lindquist S. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu J., Han B., Wang J. COVID-19: gastrointestinal manifestations and potential fecal-oral transmission. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1518–1519. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao F., Tang M., Zheng X. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831–1833.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang C., Shi L., Wang F.S. Liver injury in COVID-19: management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:428–430. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30057-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Gastroenterological Association Joint GI Society Message: COVID-19 clinical insights for our community of gastroenterologists and gastroenterology care providers. https://www.gastro.org/press-release/joint-gi-society-message-covid-19-clinical-insights-for-our-community-of-gastroenterologists-and-gastroenterology-care-providers Available at:

- 17.American Gastroenterological Association AGA Institute clinical practice guideline development process. http://www.gastro.org/guidelines-policies Available at: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 18.Graham R., Mancher M., Miller . Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al, eds. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The GRADE Working Group. Available at: guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook. Published October 2013. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 20.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen N., Zhau M., Dong X. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L., Liu H.G., Liu W. Analysis of clinical features of 29 patients with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;43:203–208. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang D., Lin M., Wei L. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus infections involving 13 patients outside Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1092–1093. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu K., Fang Y.-Y., Deng Y. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133(9):1025–1031. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young B.E., Ong S.W.X., Kalimuddin S. Epidemiologic features and clinical course of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. JAMA. 2020;323:1488–1494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou F., Ting Yu, Ronghui D. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheung K.S., Hung I.F.N., Chan P.P.Y. Gastrointestinal manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and virus load in fecal samples from a Hong Kong Cohort: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:81–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauchner H, Golub RM, Zylke J. Editorial concern: possible reporting of the same patients with COVID-19 in different reports [published online ahead of print March 16, 2020]. JAMA https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3980. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan P., Zhang D., Yang P. Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:411–412. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30113-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen L., Lou J., Bai Y. COVID-19 disease with positive fecal and negative pharyngeal and sputum viral tests. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:790. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang W., Du R., Li B. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:386–389. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1729071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y. Pathological finding of COVID-19 associated with respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia W., Shao J., Guo Y. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID-19 infection: different points from adults. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55:1169–1174. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao Y., Pan H., She Q. Prevention of SARS-Co-V-2 infection in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:528–529. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.AASLD COVID-19 Guidance American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/AASLD-COVID19-ClinicalInsights-FINAL-3.23.2020.pdf Available at:

- 38.Cai J., Sun W., Huang J. Indirect virus transmission in cluster of COVID-19 cases, Wenzhou, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1343–1345. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), February 16–24, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf Available at: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 40.Remuzzi A., Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.COVID-19 testing site opens in South Philadelphia, but with restrictions ABC News Local Philadelphia. March 21, 2020. https://6abc.com/6031085/ Available at: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 42.COVID-19 hits doctors, nurses, EMTs, threatening the health system Washington Post. March 17, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/covid-19-hits-doctors-nurses-emts-threatening-health-system/2020/03/17/f21147e8-67aa-11ea-b313-df458622c2cc_story.html Available at: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 43.With 160 employees in quarantine, Berkshire Medical Center taps 54 temporary nurses Berkshire Eagle. March 26, 2020. https://www.berkshireeagle.com/stories/with-160-employees-in-quarantine-bmc-taps-54-temp-nurses,600096?newsletter=600097 Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 44.Johnston E., Habib-Bein N., Dueker J.M. Risk of bacterial exposure to the endoscopist’s face during endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:818–824. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohandas K.M.1, Gopalakrishnan G. Mucocutaneous exposure to body fluids during digestive endoscopy: the need for universal precautions. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1999;18:109–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vavricka S., Tutuian R., Imhof A. Air suctioning during colon biopsy forceps removal reduces bacterial air contamination in the endoscopy suite. Endoscopy. 2010;42:736–741. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van den Broek P.J. Bacterial aerosols during colonoscopy: something to be worried about? Endoscopy. 2010;42:755–756. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pandemic Influenza Preparedness and Response: A WHO Guidance Document. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Institute of Medicine . The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2015. The Use and Effectiveness of Powered Air Purifying Respirators in Health Care: Workshop Summary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sehulster L.M., Chinn R.Y.W., Arduino M.J. American Society for Healthcare Engineering/American Hospital Association; Chicago IL: 2004. Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities. Recommendations from CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) [Google Scholar]

- 51.Offeddu V., Yung C.F., Low M.S.F. Effectiveness of masks and respirators against respiratory infections in healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:1934–1942. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tran K., Cimon K., Severn M. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zamora J., Murdoch J., Simchinson B., Day A. Contamination: a comparison of 2 personal protective systems. CMAJ. 2006;174:249–254. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang D., Xu Huiwen, Rebaza A. Protecting health-care workers from subclinical coronavirus infection. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(3):PE13. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30066-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang X., Pan Z., Cheng Z. Association between 2019-nCoV transmission and N95 respirator use. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105:104–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ng K., Poon B.H., Kiat Puar T.H. COVID-19 and the risk to health care workers: a case report. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:766–767. doi: 10.7326/L20-0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bailar J., Burke D. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. Reusability of Facemasks During an Influenza Pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roberge R.J. Effect of surgical masks worn concurrently over N95 filtering facepiece respirators: extended service life versus increased user burden. J Public Health Manage Pract. 2008;14(2):E19–E26. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000311904.41691.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beckman N.G. The distribution of fruit and seed toxicity during development for eleven neotropical trees and vines in Central Panama. PLoS One. 2013;8(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hines L., Rees E., Pavelchak N. Respiratory protection policies and practices among the health care workforce exposed to influenza in New York State: evaluating emergency preparedness for the next pandemic. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fisher E.M., Noti J.D., Lindsley W.G. Validation and application of models to predict facemask influenza contamination in healthcare settings. Risk Anal. 2014;34:1423–1434. doi: 10.1111/risa.12185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bergman M.S., Viscusi D.J., Zhuang Z. Impact of multiple consecutive donnings on filtering facepiece respirator fit. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:375–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Battelle, Final Report for the Bioquell Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor (HPV) Decontamination for Reuse of N95 Respirators Prepared under Contract No. HHSF223201400098C Study Number 3245, July 2016, US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/media/136386/download Available at: