Abstract

Background

Physician-staffed emergency medical services (p-EMS) are resource demanding, and research is needed to evaluate any potential effects of p-EMS. Templates, designed through expert agreement, are valuable and feasible, but they need to be updated on a regular basis due to developments in available equipment and treatment options. In 2011, a consensus-based template documenting and reporting data in p-EMS was published. We aimed to revise and update the template for documenting and reporting in p-EMS.

Methods

A Delphi method was applied to achieve a consensus from a panel of selected European experts. The experts were blinded to each other until a consensus was reached, and all responses were anonymized. The experts were asked to propose variables within five predefined sections. There was also an optional sixth section for variables that did not fit into the pre-defined sections. Experts were asked to review and rate all variables from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree) based on relevance, and consensus was defined as variables rated ≥4 by more than 70% of the experts.

Results

Eleven experts participated. The experts generated 194 unique variables in the first round. After five rounds, a consensus was reached. The updated dataset was an expanded version of the original dataset and the template was expanded from 45 to 73 main variables. The experts approved the final version of the template.

Conclusions

Using a Delphi method, we have updated the template for documenting and reporting in p-EMS. We recommend implementing the dataset for standard reporting in p-EMS.

Keywords: Documentation, Data collection, Pre-hospital, Physician, Emergency medical services, Consensus, Air ambulances, Quality of health care

Background

Physician-staffed emergency medical services (p-EMS) are common in European countries, and they provide highly specialized, goal-directed therapy. Pre-hospital physicians have the potential to restore adequate flow and physiology in severely sick or injured patients, but the subject remains debated [1–6]. P-EMS are resource demanding compared with standard paramedic-staffed services [7], and more research is needed to evaluate any potential effects of p-EMS [1, 8, 9]. High-quality research relies on data quality and uniform documentation is essential to ensure reliable and valid data. Currently, p-EMS data are low quality, and the lack of systematic documentation complicates comparison, creating a barrier for high-quality outcome research [10].

In 2011, a consensus-based template for documenting and reporting data in p-EMS was published [7]. Templates for uniform documentation may facilitate international multi-centre studies, thereby increasing the quality of evidence [11]. Such templates, designed through expert agreement, are valuable and feasible, but they need to be updated on a regular basis due to developments in available equipment and treatment options [12–15]. The p-EMS template has been incorporated for daily use in Finland, but it has not yet been implemented in other European countries. A recent study concluded that the published template is feasible for use in p-EMS and that a large amount of data may be captured, facilitating collaborative research [16]. However, the feasibility study revealed areas for improvement of the template. To make the template even more relevant, further revisions should be made.

The aim of this study was to revise and update the template for documenting and reporting in p-EMS through expert consensus [7] using the Delphi method.

Methods

The experts

No exact criterion exists concerning selection of participants for a Delphi study.

Many European countries share similarities with regards to infrastructure, socio-political system and health care services, favouring research collaboration [17]. Representatives from European p-EMS were invited to join an expert panel using the same inclusion criteria as the original template:

Clinical experience by working in p-EMS to ensure personal insight into the operative and medical characteristics of advanced pre-hospital care.

Scientific and/or substantial leadership responsibilities in pre-hospital care to ensure competency in research methods and governance of pre-hospital emergency systems.

Ability to communicate in English.

The experts were identified via the European Prehospital Research Alliance (EUPHOREA) network. The EUPHOREA network consists of representatives from p-EMS throughout central Europe, UK and Scandinavia. Experts were invited via e-mail. Non-responders were reminded via e-mail. For all rounds non-responders were reminded twice per e-mail.

The Delphi method

A Delphi technique was applied to achieve a consensus from a panel of selected experts interacting via e-mail. No physical meetings were held. A research coordinator interacted with the participants, administered questionnaires and collected the responses until a consensus was reached. The experts were blinded to each other until an agreement was reached. All responses were anonymized. The Delphi process ran from Feb. 19 to Oct. 1, 2019. The final dataset was approved by all experts.

Objectives for each round of the Delphi process

The experts were asked to propose variables within each of five predefined sections:

-

Fixed system variables

Variables describing how the p-EMS is organized, competence in the p-EMS team and its operational capacities (e.g., dispatch criteria, population, mission case-mix and equipment utilized by the services). These data do not change between missions and are considered fixed.

-

Event operational descriptors

Variables documenting the mission context (e.g., data on logistics, type of dispatch, time variables and mission type).

-

Patient descriptors

Variables documenting patient state (e.g., age, gender, comorbidity, patient physiology and medical complaint).

-

Process mapping variables

Variables documenting diagnostic and therapeutic procedures (e.g., monitoring, medication, airway devices used, etc.) performed during the period of p-EMS care.

-

Outcome and quality indicators

Variables describing patient outcome and quality.

There was also an optional sixth section for proposals of variables that did not fit into one of the pre-defined sections.

Round I

Each expert suggested 10 variables considered to be most important for routine documentation in p-EMS within each of the five predefined sections.

Round II

The results from the first round were structured in a worksheet (Excel for Mac, version 16.31, 2019 Microsoft). Duplicate suggestions were removed before the variables were returned to the experts. Variables from the original template were included if not suggested by the experts. Experts were asked to review and rate all variables from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree) based on relevance.

Round III

Variables rated ≥4 by more than 70% of the experts were included in the template draft and presented to the experts [18, 19]. In addition, the experts received a number of questions pertaining to the wording of questions, consent to delete some questions because of overlap, relevance of alternatives under a main question, and whether there should be a free-text field for addressing key lessons. Furthermore, they were instructed to provide comments and grade the variables as either compulsory or optional. Later, the experts were asked to suggest the frequency of variable reporting (for each mission, monthly or annually). Variables rated ≥4 by less than 50% of the experts were excluded. Variables rated ≥4 by more than 50% of the experts were summarized and re-rated by the experts. If more than 70% of the experts rated a variable ≥4 in this second round, the variable was included in the final template.

Round IV

After summarizing the feedback from round III, the list of variables achieving consensus, accompanying comments, and further questions were distributed to the experts. All variables were numbered. This round provided an opportunity for the experts to revise their judgements and combine similar variables.

Round V

Feedback from round IV was summarized into a final version of the template and sent to the experts to elicit any objections and/or to give final approval of the template for routine reporting in p-EMS.

The study was drafted according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) [20].

Results

The experts

Thirty experts were invited to join the consensus process and 15 agreed to participate. Eleven experts responded in the first Delphi round, ten responded in the second round and nine responded in the last three rounds.

Round I

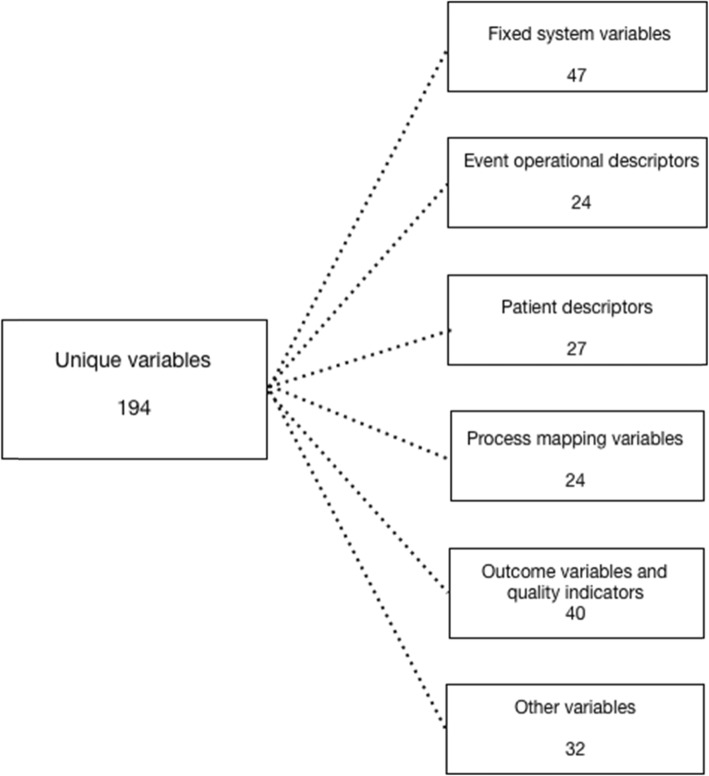

The experts suggested 194 unique variables in the first round (Fig. 1). All variables from the original template were among the suggested variables.

Fig. 1.

Suggested variables. Number of suggested variables for the different sections in the first round of the Delphi process

Round II

The experts rated the variables suggested in round I from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree) based on relevance. A total of 68 main variables (24 fixed system variables, 10 event operational descriptors, 15 patient descriptors, 10 process mapping variables, 9 outcome and quality indicators and no other variables) were rated ≥4 by more than 70% of the experts and included in the preliminary template. Thirty-five main variables and 32 sub-variables were rated < 4 by 50–70% of the experts. Ninety-one variables were rated ≥4 by less than 50% of the experts and were excluded.

Round III

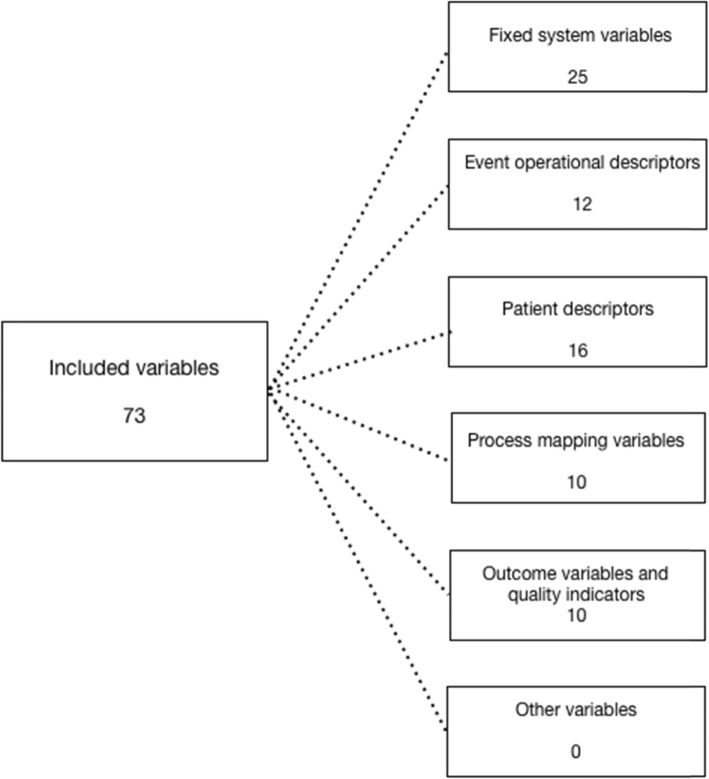

The preliminary template was presented to the experts. Additionally, the experts rated the 35 main variables and 32 sub-variables that were initially rated ≥4 by 50–70% once more. Five more main variables and 9 sub-variables were included after this second rating. In total, 73 main variables were included (Fig. 2). The experts agreed that all fixed system variables should be reported annually while all event operational descriptors, patient descriptors, process mapping variables and outcome and quality indicators should be reported after each mission.

Fig. 2.

Included variables. Final number of variables included in the updated template

Round IV

The included variables were presented to the experts. After feedback from the experts the wording of variables 1.23.6 and 3.5.6. were changed from “Chest pain, excluding MI” to “Chest pain, MI not confirmed”. Variable 3.8.4. “Systolic blood pressure (SBP) not recordable” and 3.10.4. “SpO2 not recordable” were added. Variables 3.13.1. and 3.13.2. were changed to record the VAS score instead of pain as none, moderate or severe and variable 4.6.17. was changed from “Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA)” to “Endovascular Resuscitation (EVR)”.

Round V

The experts approved the final version of the template (Table 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5).

Table 1.

Fixed system variables

| Data variable number | Main data variable name | Type of data | Data variable categories or values | Data variable sub-categories or values | Type | Definition of data variable | How often should variable be reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fixed system variables | |||||||

| 1.1. | Specialty of physicians | Categorical | 1.1.1 Anaesthesiology | Check box | Specialty of physicians working in the service on a regular basis | Annual | |

| 1.1.2 Emergency medicine | |||||||

| 1.1.3 Intensive care | |||||||

| 1.1.4 Surgery | |||||||

| 1.1.5 Internal medicine | |||||||

| 1.1.6 Other | |||||||

| 1.2. | Training level of physicians | Categorical | 1.2.1 Trainee/registrar | Check box | Annual | ||

| 1.2.2 Specialist | |||||||

| 1.3. | Composition of team | Categorical | 1.3.1 Nurse | Check box | Qualification of non-p-EMS personnel accompanying the physician during mission | Annual | |

| 1.3.2. Paramedic | As defined by each national service | ||||||

| 1.3.3. EMS-technician | As defined by each national service | ||||||

| 1.3.4. Other | |||||||

| 1.4. | Catchment population | Continuous | Number | Number of citizens in the area covered by the service on a regular basis | Annual | ||

| 1.5. | Catchment area | Continuous | 1.5.1. Square km | Number | Area in which the service is planned to operate on a regular basis, square km | Annual | |

| Categorical | 1.5.2. Type | 1.5.2.1. Urban | Check box | Type of area where service operate on a regular basis (as defined by each service) | |||

| 1.5.2.2. Rural | |||||||

| 1.6. | Does the service conduct primary missions? | Categorical | 1.6.1. Yes | Bullet list | On-scene missions | Annual | |

| 1.6.2. No | |||||||

| 1.7. | Does the service conduct inter-hospital transfer missions? | Categorical | 1.7.1. Yes | Bullet list | Patient transfers between different hospitals or facilities | Annual | |

| 1.7.2. No | |||||||

| 1.8. | Number of consultations only (advice) per year | Continuous | Number | Physician is consulted by EMS or other professionals (give advice) | Annual | ||

| 1.9. | Number of primary missions per year | Continuous | Number | Missions where physician is on-scene. Total number for the service | Annual | ||

| 1.10. | Number of inter-hospital transfer missions per year | Continuous | Number | Inter-hospital or interfacility transfer. Total number for the service | Annual | ||

| 1.11. | Number of cancelled missions per year | Continuous | Number | Any mission where p-EMS is alarmed but not able to respond or must interrupt mission | Annual | ||

| 1.12. | Number of events per year per physician | Continuous | Number | The average number of missions per individual physician per year | Annual | ||

| 1.13. | Number of events for p-EMS unit/100,000 inhabitants per year | Continuous | Number | Annual | |||

| 1.14. | Number of EMS events/100,000 inhabitants per year | Continuous | Number | Number of events for the whole EMS system, including p-EMS | Annual | ||

| 1.15. |

Number of p-EMS units/ 100,000 inhabitants |

Continuous | Number | Annual | |||

| 1.16. | Number of p-EMS units/km2 | Continuous | Number | Area in which the service operates on a regular basis | Annual | ||

| 1.17. | Available vehicles in service | Categorical | Check box | Available vehicles on a regular basis for p-EMS | Annual | ||

| 1.17.1. Rapid response car | Regular car, no stretcher | ||||||

| 1.17.2. Regular ambulance staffed with physician | Car with stretcher. Physician is attending on a regular basis | ||||||

| 1.17.3. Rotor Wing | |||||||

| 1.17.4. Fixed Wing | |||||||

| 1.17.5. Boat staffed with physician | Physician is attending on a regular basis | ||||||

| 1.17.6. Other | |||||||

| 1.18. | Operating hours | Categorical | 1.18.1. Daytime | Bullet list | Regular working hours, e.g., 08–16, as defined by each service | Annual | |

| 1.18.2. Daylight only | Service operates only in daylight (different opening hours during the year due to seasonal variations). Daylight as defined by each service | ||||||

| 1.18.3. 24/7 (full-time service) | Service operates during the day and night | ||||||

| 1.18.4. Other | |||||||

| 1.19. | Activation criteria | Categorical | 1.19.1. Criteria based | Check box | P-EMS activated in accordance with a pre-defined set of activation criteria used by EMCC | Annual | |

| 1.19.2. Consultation with physician | Physician-staffed unit activated only after consultation with an on-call physician | ||||||

| 1.19.3. Individual | No predefined criteria for activation of p-EMS | ||||||

| 1.20. | Dispatch system | Categorical | 1.20.1. Integrated EMCC | Check box | Integrated EMCC includes dispatch centres coordinating all levels of pre-hospital services | Annual | |

| 1.20.2. Special EMCC | Special EMCC includes centres only responsible for p-EMS units | ||||||

| 1.20.3. Other | |||||||

| 1.21. | Advanced equipment carried by service | Categorical | 1.21.1. Blood products | Check box | Advanced equipment available on a regular basis to service | Annual | |

| 1.21.2. Mechanical chest compression device | |||||||

| 1.21.3. Ultrasound | |||||||

| 1.21.4. Advanced drugs | Drugs not available to regular EMS in the individual system | ||||||

| 1.21.5. Additional airway management equipment (e.g., videoscope) |

Airway management equipment beyond the scope of regular EMS |

||||||

| 1.21.6. Surgical procedures supported | Service carries equipment for predefined surgical procedures | ||||||

| 1.22. | Does a system for registration and reviewing of adverse events, critical incidents and educational events in the service exist? | Categorical | 1.22.1. Yes | Bullet list | Annual | ||

| 1.22.2 No | |||||||

| 1.23. | Categorization of events/case mix | Categorical | 1.23.1. Cardiac arrest medical aetiology | Check box | Mission types the service responds to | Annual | |

| 1.23.2. Cardiac arrest traumatic aetiology | |||||||

| 1.23.3. Trauma | |||||||

| 1.23.4. Breathing difficulties | |||||||

| 1.23.5. Myocardial infarction (MI) | Confirmed by ECG | ||||||

| 1.23.6. Chest pain, MI not confirmed | |||||||

| 1.23.7. Stroke | |||||||

| 1.23.8. Acute neurology excluding stroke | |||||||

| 1.23.9. Reduced level of consciousness | |||||||

| 1.23.10. Poisoning/Intoxication | |||||||

| 1.23.11. Burns | |||||||

| 1.23.12. Obstetrics and childbirth | |||||||

| 1.23.13. Infection | |||||||

| 1.23.14. Anaphylaxis | |||||||

| 1.23.15. Surgical | |||||||

| 1.23.16. Asphyxiation | |||||||

| 1.23.17. Drowning | |||||||

| 1.23.18. Psychiatry excluding poisoning/intoxication | |||||||

| 1.23.19. All of the above | Service responds to all types of events | ||||||

| 1.23.20. Other | |||||||

| 1.24. | Number of intubations successful on first attempt and without desaturation (DASH1a intubations) /100 intubations | Continuous | Number | Annual | |||

| 1.25. | Number of patients where blood glucose was measured after ROSC/100 ROSC | Continuous | Number | Annual | |||

EMS- Emergency medical services, p-EMS - Physician-staffed emergency medical services, EMCC - Emergency medical communication centre, MI - Myocardial infarction, ECG – Electrocardiogram, DASH1a - Definitive airway sans hypoxia/hypotension on first attempt,

ROSC – Return of spontaneous circulation

Table 2.

Event operational descriptors

| Data variable number | Main data variable name | Type of data | Data variable categories or values | Data variable sub-categories or values | Type | Definition of data variable | How often should variable be reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2. Event operational descriptors | |||||||

| 2.1. | Time points | Continuous | For each mission | ||||

| 2.1.1. Call received at EMCC | hh:mm | When the alarm call is answered at the initial EMCC | |||||

| 2.1.2. Time of system activation (dispatch time) | hh:mm | When EMCC dispatch p-EMS | |||||

| 2.1.3. Unit en route/take-off time | hh:mm | When vehicle starts to move (car or rotor wing/fixed wing) | |||||

| 2.1.4. Unit arrival on scene | hh:mm | When vehicle stops at a location as close as possible to the patient | |||||

| 2.1.5. Time of first physician contact with patient | hh:mm | When pre-hospital physician arrives at patient site | |||||

| 2.1.6. Time when patient leaves scene | hh:mm | When patient is transferred from the original location or time of death if dead on scene | |||||

| 2.1.7. Time when patient arrives at hospital (or alternative site if not delivered to hospital) | hh:mm | When the patient is formally transferred to receiving medical facility personnel | |||||

| 2.2. | Date of event | Continuous | dd.mm.yyyy | The date the unit was dispatched | For each mission | ||

| 2.3. | Type of mission/dispatch | Categorical | Check box | For each mission | |||

| 2.3.1. Primary medical mission | Includes all primary missions other than trauma (medical, surgical, paediatric, obstetric) | ||||||

| 2.3.2. Primary trauma mission | Includes all primary trauma missions | ||||||

| 2.3.3. Inter-hospital transfer mission | Inter-hospital or inter-facility mission | ||||||

| 2.3.4. SAR mission | |||||||

| 2.3.5. Major incident response | |||||||

| 2.3.6. Contingency | |||||||

| 2.3.7. Rendezvous with ambulance | |||||||

| 2.3.8. Consultation | |||||||

| 2.3.9. Single patient | Only one patient treated by p-EMS during the mission | ||||||

| 2.3.10. Multiple patients | More than one patient treated by p-EMS during the mission | ||||||

| 2.3.11. Other | |||||||

| 2.4. | Dispatch criteria | Categorical | Check box | Medical reason for dispatch | For each mission | ||

| 2.4.1. Medical | |||||||

| 2.4.2. Trauma | |||||||

| 2.4.3. Neurologic | |||||||

| 2.4.4. Obstetric | |||||||

| 2.4.5. Burn | |||||||

| 2.4.6. Other | |||||||

| 2.5. | Activation type | Categorical | Bullet list | For each mission | |||

| 2.5.1. Primary mission | |||||||

| 2.5.1.1. Initiated by dispatch centre | |||||||

| 2.5.1.2. Requested dispatch from other units | |||||||

| 2.5.1.3. Other | |||||||

| Categorical | 2.5.2. Inter-hospital transfer mission | ||||||

| 2.5.2.1. Physician-staffed unit used because of level of treatment during transport | |||||||

| 2.5.2.2. Physician-staffed unit used because of speed of transport | |||||||

| 2.5.2.3. Both above | |||||||

| 2.5.2.4. Other | |||||||

| 2.6. | Mode of transportation to scene | Categorical | Bullet list | Main type of vehicle used to get p-EMS to the scene | For each mission | ||

| 2.6.1. Rapid response car | Regular car, no stretcher | ||||||

| 2.6.2. Regular ambulance | Car with stretcher | ||||||

| 2.6.3. Rotor Wing | |||||||

| 2.6.4. Fixed Wing | |||||||

| 2.6.5. Boat staffed with physician | |||||||

| 2.6.6. Other | |||||||

| 2.7. | Mode of transportation from scene | Categorical | Bullet list | Main type of vehicle used to transport the patient to definitive care | For each mission | ||

| 2.7.1. Rapid response car | |||||||

| 2.7.2. Regular ambulance staffed with physician | Physician is part of the ambulance crew on a regular basis | ||||||

| 2.7.3. Regular ambulance with physician attending | Ambulance crew normally without a physician, physician is attending because of patient need | ||||||

| 2.7.4. Patient transported in ambulance without physician | |||||||

| 2.7.5. Rotor wing | |||||||

| 2.7.6. Fixed wing | |||||||

| 2.7.7. Boat staffed with physician | |||||||

| 2.7.8. Patient not transported due to no indication | |||||||

| 2.7.9. Patient not transported due to patient refusal | |||||||

| 2.7.10. Patient dead and not transported | |||||||

| 2.7.11. Other | |||||||

| 2.8. | Result of dispatch | Bullet list | Dispatch means unit alarmed for mission or request/advice/supervision | For each mission | |||

| Categorical | 2.8.1. Patient attended | P-EMS attended the patient | |||||

| 2.8.1.1. Transported with physician escort | |||||||

| 2.8.1.2. Transported without physician escort | |||||||

| 2.8.1.3. Discharged on-scene | Patient not transported | ||||||

| 2.8.1.4. Pronounced dead on scene | |||||||

| Categorical | 2.8.2. Patient not attended | P-EMS did not attend the patient. The main reason why mission is aborted or refused | For each mission | ||||

| 2.8.2.1. Weather | |||||||

| 2.8.2.2. Technical reasons | |||||||

| 2.8.2.3. Other mission (concurrency) | |||||||

| 2.8.2.4. Alternative tasking | |||||||

| 2.8.2.5. Mission refused due to duty time limitations | |||||||

| 2.8.2.6. Fatigue | |||||||

| 2.8.2.7. Not needed | |||||||

| 2.8.2.8. No time benefit | |||||||

| 2.8.2.9. Patient has left scene (before arrival of unit) | |||||||

| 2.8.2.10. Mission taken over by another p-EMS | |||||||

| 2.9. | Trauma mechanism | Categorical | Bullet list | The Utstein Trauma template. The mechanism (or external factor) that caused the injury event | For each mission | ||

| 2.9.1. Not trauma | |||||||

| 2.9.2. Blunt trauma | |||||||

| 2.9.2.1. Traffic - motor vehicle injury | Car, pickup, truck, van, heavy transport vehicle, bus | ||||||

| 2.9.2.2. Traffic - motorbike | |||||||

| 2.9.2.3. Traffic - bicycle | |||||||

| 2.9.2.4. Traffic - pedestrian | |||||||

| 2.9.2.5. Traffic - other | Ship, airplane, railway train | ||||||

| 2.9.2.6. Fall from same level | Low energy fall. From the persons height or less | ||||||

| 2.9.2.7. Fall from higher level | High energy fall. From more than the persons height | ||||||

| 2.9.2.8. Struck or hit by blunt object | Tree, tree branch, bar, stone, human body part, metal, other | ||||||

| 2.9.2.9. Explosives | Blast injuries | ||||||

| 2.9.2.10 Other | |||||||

| 2.9.2.11. Unknown | |||||||

| 2.9.3. Penetrating trauma | |||||||

| 2.9.3.1. Stabbed by pointed or sharp object | Knife, sword, dagger or other | ||||||

| 2.9.3.2. Gun | By handgun, shotgun, rifle, or another firearm of any dimension | ||||||

| 2.9.3.3. Other | |||||||

| 2.9.4. Unknown | Unknown trauma mechanism | ||||||

| 2.10. | Specialty of the attending physician | Categorical | Check box | The pre-hospital physician attending patient on scene | For each mission | ||

| 2.10.1. Anaesthesiology | |||||||

| 2.10.2. Emergency medicine | |||||||

| 2.10.3. Intensive care | |||||||

| 2.10.4. Surgery | |||||||

| 2.10.5. Internal medicine | |||||||

| 2.10.6. Other | |||||||

| 2.11. | NACA score | Categorical | Bullet list | NACA 0–7 | For each mission | ||

| 2.11.1. NACA 0 | |||||||

| 2.11.2. NACA 1 | |||||||

| 2.11.3. NACA 2 | |||||||

| 2.11.4. NACA 3 | |||||||

| 2.11.5. NACA 4 | |||||||

| 2.11.6. NACA 5 | |||||||

| 2.11.7. NACA 6 | |||||||

| 2.11.8. NACA 7 | |||||||

| 2.11.9. NACA score unknown | |||||||

| 2.12. | Where patient is delivered | Categorical | Bullet list | Where physician-staffed unit delivers patient | For each mission | ||

| 2.12.1. Major Trauma Centre/Definitive care centre | Hospital where all definitive treatment is available (to the particular patient) | ||||||

| 2.12.2. Local hospital | Hospital where all definitive treatment is not available (to the particular patient) | ||||||

| 2.12.3. Other health care facility | Facility not defined as hospital | ||||||

EMCC Emergency medical communication centre, SAR Search and rescue, p-EMS physician-staffed emergency medical services, NACA score National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics score

Table 3.

Patient descriptors

| Data variable number | Main data variable name | Type of data | Data variable categories or values | Data variable sub-categories or values | Type | Definition of data variable | How often should variable be reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3. Patient descriptors | |||||||

| 3.1. | Age | Continuous | Number | Patient age at the time of event | For each mission | ||

| 3.2. | Gender | Categorical | 3.2.1 Female | Bullet list | Patient gender | For each mission | |

| 3.2.2 Male | |||||||

| 3.2.3 Unknown | |||||||

| 3.3. | Pre-event comorbidity | Ordinal | Bullet list | Pre-event ASA-PS. The comorbidity existing before event. Derangements from present disease should not be considered | For each mission | ||

| 3.3.1 ASA-PS 1 | A normal healthy patient | ||||||

| 3.3.2 ASA-PS 2 | A patient with mild systemic disease | ||||||

| 3.3.3 ASA-PS 3 | A patient with severe systemic disease | ||||||

| 3.3.4 ASA-PS 4 | A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life | ||||||

| 3.3.5 ASA-PS 5 | A moribund patient who is not expected to survive without operation | ||||||

| 3.3.6 ASA-PS 6 | A declared brain-dead patient whose organs are being removed for donor purposes | ||||||

| 3.3.7 ASA Unknown | |||||||

| 3.4. | Chronic medications | Categorical | 3.4.1 Yes | Bullet list | Does patient use medication on a regular basis? | For each mission | |

| 3.4.2 No | |||||||

| 3.4.3 Unknown | |||||||

| 3.5. | Medical problem | Categorical | Bullet list | The condition most likely to be the patient’s true medical problem, main clinical symptom or diagnosis, decided by attending p-EMS | For each mission | ||

| 3.5.1 Cardiac arrest medical aetiology | |||||||

| 3.5.2 Cardiac arrest traumatic aetiology | |||||||

| 3.5.3 Trauma | |||||||

| 3.5.4 Breathing difficulties | |||||||

| 3.5.5 Myocardial infarction (MI) | Confirmed by ECG | ||||||

| 3.5.6 Chest pain, MI not confirmed | |||||||

| 3.5.7 Stroke | |||||||

| 3.5.8 Acute neurology excluding stroke | |||||||

| 3.5.9. Reduced level of consciousness | Aetiology unknown | ||||||

| 3.5.10 Poisoning/Intoxication | |||||||

| 3.5.11 Burns | |||||||

| 3.5.12 Obstetrics and childbirth | |||||||

| 3.5.13 Infection | |||||||

| 3.5.14 Anaphylaxis | |||||||

| 3.5.15 Surgical | |||||||

| 3.5.16 Asphyxiation | |||||||

| 3.5.17 Drowning | |||||||

| 3.5.18 Psychiatry excluding poisoning/intoxication | |||||||

| 3.5.19 Other | |||||||

| 3.6. | Glasgow Coma Scale | Ordinal | 3.6.1 First | Number | First recorded pre-interventional GCS upon arrival of p-EMS | For each mission | |

| 3.6.2 Last | GCS at end of patient care or patient handover | ||||||

| 3.6.3 Not recorded | |||||||

| Categorical | 3.6.4 Patient intubated | 3.6.4.1 Yes | Bullet list | ||||

| 3.6.4.2 No | |||||||

| 3.7. | Heart rate | Continuous | Number | Documented by ECG (1st choice), palpation or SpO2 curves (3rd choice) | |||

| 3.7.1 First | First heart rate per minute measured by p-EMS upon arrival | ||||||

| 3.7.2 Last | Heart rate per minute at end of care or patient handover | ||||||

| 3.7.3 Not recorded | |||||||

| 3.8. | Systolic blood pressure | Continuous | 3.8.1 Lowest | Number | Lowest recorded systolic blood pressure measured by p-EMS (sphygmomanometer, monitor or intra-arterial line) upon arrival | ||

| 3.8.2 First | First recorded systolic blood pressure measured by p-EMS (sphygmomanometer, monitor or intra-arterial line) upon arrival | ||||||

| 3.8.3 Last | Systolic blood pressure at end of care or patient handover | ||||||

| 3.8.4 Not recordable | Not possible to record despite several attempts | ||||||

| 3.8.5 Not recorded | |||||||

| 3.9. | Cardiac rhythm/ECG rhythm | Categorical | 3.9.1 First | 3.9.1.1 Sinus rhythm | Bullet list | First cardiac rhythm interpreted by p-EMS (minimum 3-channel lead). At primary survey/upon arrival | For each mission |

| 3.9.1.2. SVES, VESmono | |||||||

| 3.9.1.3 AF/AFL/AV-block gr II/III, VESpoly | |||||||

| 3.9.1.4 VF, VT, Asystole, PEA | |||||||

| 3.9.1.5 Not recorded | |||||||

| 3.9.2 Last | 3.9.2.1 Sinus rhythm | Cardiac rhythm at end of care or patient handover (minimum 3-channel lead) | |||||

| 3.9.2.2 SVES, VESmono | |||||||

| 3.9.2.3 AF/AFL/AV-block gr II/III, VESpoly | |||||||

| 3.9.2.4 VF, VT, Asystole, PEA | |||||||

| 3.9.2.5 Not recorded | |||||||

| 3.10. | SpO2 | Continuous | 3.10.1 Lowest | Number | Lowest recorded oxygen saturation by p-EMS (measured with pulse oximeter or arterial blood gas (SaO2)) | For each mission | |

| 3.10.2 First | First recorded oxygen saturation by p-EMS (measured with pulse oximeter or arterial blood gas (SaO2) upon arrival) | ||||||

| 3.10.3 Last | Oxygen saturation at end of care or patient handover | ||||||

| 3.10.4 Not recordable | Not possible to record despite several attempts | ||||||

| 3.10.5 Not recorded | |||||||

| 3.11. | Oxygen supplementation | Categorical | 3.11.1 Oxygen supplementation at first measurement of SpO2 | 3.11.1.1 Yes | Bullet list | First measurement by p-EMS | For each mission |

| 3.11.1.2 No | |||||||

| 3.11.2 Oxygen supplementation at last measurement of SpO2 | 3.11.2.1 Yes | Last measurement by p-EMS | |||||

| 3.11.2.2 No | |||||||

| 3.12. | Respiratory rate | Continuous | 3.12.1 First | Number | First respiratory rate per minute measured by p-EMS upon arrival. If mechanically ventilated; document ventilation rate | For each mission | |

| 3.12.2 Last | Respiratory rate at end of care or patient handover | ||||||

| 3.12.3 Not recorded | |||||||

| 3.13. | Pain | Categorical | 3.13.1 First VAS score | Number | First VAS score assessed by p-EMS upon arrival | For each mission | |

| 3.13.2 Last VAS score | VAS score at end of care or patient handover | ||||||

| 3.13.3 Not recorded | |||||||

| 3.14. | End-tidal CO2 | Continuous | 3.14.1 First | Number | First end-tidal CO2 measured by p-EMS | For each mission | |

| 3.14.2 Last | Last end-tidal CO2 measured by p-EMS | ||||||

| 3.14.3 Not recorded | |||||||

| 3.15. | Temperature (core) | Continuous | 3.15.1 First | Number | First core temperature measured by p-EMS upon arrival | For each mission | |

| 3.15.2 Last | Last core temperature measured by p-EMS | ||||||

| 3.15.3 Not recorded | |||||||

| 3.16 | Airway at primary survey | Categorical | 3.16.1 Clear | Bullet list | As rated by attending physician | For each mission | |

| 3.16.2 Threatened | |||||||

| 3.16.3 Obstructed | |||||||

| 3.16.4 Unknown | |||||||

ASA-PS American Society of Anesthesiologists physical scale, p-EMS physician-staffed emergency medical services, MI Myocardial infarction, ECG Electrocardiogram, GCS Glasgow coma score, SpO2 Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation, SVES Supraventricular extrasystole, VESmono Ventricular extrasystole, monomorphic, AF Atrial fibrillation, AFL Atrial flutter, AV-block Atrioventricular block, VESpoly Ventricular extrasystole, polymorphic, VF Ventricular fibrillation, VT Ventricular tachycardia, PEA Pulseless electrical activity, SaO2 Arterial oxygen saturation, VAS Visual analogue scale, CO2 Carbon dioxide

Table 4.

Process mapping variables

| Data variable number | Main data variable name | Type of data | Data variable categories or values | Data variable sub-categories or values | Type | Definition of data variable | How often should variable be reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4. Process mapping | |||||||

| 4.1. | Diagnosis and monitoring procedures | Categorical | 4.1.1 Blood pressure | 4.1.1.1 Non-invasive | Check box | Monitoring used and procedures performed by p-EMS | For each mission |

| 4.1.1.2 Invasive | |||||||

| 4.1.1.3. Other | |||||||

| 4.1.2. SpO2 | |||||||

| 4.1.3. EtCO2 | Capnometry or capnography used | ||||||

| 4.1.4. Temperature (core) | Temperature measured during mission | ||||||

| 4.1.5. ECG | 4.1.5.1. Monitoring (3 or 4-lead or pads) | ||||||

| 4.1.5.2. Analysis (12-lead) | |||||||

| 4.1.6. Ultrasound/Doppler | 4.1.6.1. FAST | By p-EMS | |||||

| 4.1.6.2. Lung for pneumothorax | By p-EMS | ||||||

| 4.1.7. Point of care (POC) blood gas analysis | By p-EMS | ||||||

| 4.1.8. Other POC testing | By p-EMS | ||||||

| 4.1.9. POC lab test | By p-EMS | ||||||

| 4.1.10. Blood glucose | By p-EMS | ||||||

| 4.1.11. Other | |||||||

| 4.1.12. None | |||||||

| 4.2. | Drugs used to facilitate airway management | Categorical | 4.2.1. Sedatives | Check box | By p-EMS | For each mission | |

| 4.2.2. NMBA | |||||||

| 4.2.3. Analgesics | |||||||

| 4.2.4. Local/topic anaesthetics | |||||||

| 4.2.5. Other | |||||||

| 4.2.6. None | |||||||

| 4.3. | Airway management | Categorical | 4.3.1. Oxygen | Check box | Device or procedures used for successful airway management | For each mission | |

| 4.3.2. Manual | Chin-lift, jaw thrust, recovery position | ||||||

| 4.3.3. Bag Mask Ventilation | |||||||

| 4.3.4. Nasopharyngeal device | |||||||

| 4.3.5. Oropharyngeal device | |||||||

| 4.3.6. SAD 1. generation | Laryngeal mask with no mechanism for protection against aspiration | ||||||

| 4.3.7. SAD 2. generation | Laryngeal mask with any aspiration protection mechanism | ||||||

| 4.3.8. Oral ETI | |||||||

| 4.3.9. Nasal ETI | |||||||

| 4.3.10. Surgical airway | 4.3.10.1. Mac-blade | ||||||

| 4.3.10.2. Hyper angulated blade | |||||||

| 4.3.11. Other | |||||||

| 4.3.12. None | |||||||

| 4.4. | Number of attempts to secure airway | Continuous | Number | Number of attempts needed before a definitive airway is in place by p-EMS | For each mission | ||

| 4.5. | Breathing- related procedures | Categorical | Check box | Procedures performed by p-EMS | For each mission | ||

| 4.5.1. Controlled manually | Breathing assistance using physician’s hands. Bag valve mask ventilation | ||||||

| 4.5.2. Controlled mechanically | Use of technical respiratory support; ventilator, NIV | ||||||

| 4.5.3. Needle decompression | |||||||

| 4.5.4. Chest tube | |||||||

| 4.5.5. Thoracostomy | |||||||

| 4.5.6. Escharotomy | |||||||

| Continuous | 4.5.7. FiO2 | If patient is ventilated | |||||

| Continuous | 4.5.8. PEEP | If patient is ventilated | |||||

| 4.5.9. Other | |||||||

| 4.5.10. None | |||||||

| 4.6. | Circulation- related procedures | Categorical | 4.6.1. Peripheral i.v. line | Check box | Procedures performed by p-EMS | For each mission | |

| 4.6.2. Intraosseous access | |||||||

| 4.6.3. Central i.v. line | |||||||

| 4.6.4. Arterial line | |||||||

| 4.6.5. External pacing | |||||||

| 4.6.6. Internal pacing | |||||||

| 4.6.7. Defibrillation | |||||||

| 4.6.8. Cardioversion | |||||||

| 4.6.9. Volume replacement therapy (infusions) administered | Check box | Record if intention is to increase circulating volume. Do not record if intention is to “keep-line-open” | |||||

| 4.6.9.1. Colloids | |||||||

| 4.6.9.2. Crystalloids | |||||||

| 4.6.9.3. Blood products | |||||||

| 4.6.10. Blood products administered | 4.6.10.1. Whole blood | Check box | |||||

| 4.6.10.2. PRBC | |||||||

| 4.6.10.3. Liquid plasma /fresh frozen plasma | |||||||

| 4.6.10.4. Lyoplas | |||||||

| 4.6.10.5. Other | |||||||

| Continuous | 4.6.11. Amount of fluid administered | Number | Millilitres given by p-EMS | ||||

| Categorical | 4.6.12. Haemostatic dressing | 4.6.12.1. Pressure bandage | Check box | ||||

| 4.6.12.2. Packing of wound | |||||||

| 4.6.12.3. Tourniquet | |||||||

| 4.6.12.4. Pelvic binder | |||||||

| 4.6.13. Pericardiocentesis | |||||||

| 4.6.14. Manual chest compressions | |||||||

| 4.6.15. Mechanical chest compressions | |||||||

| 4.6.16. Thoracotomy | 4.6.16.1. Lateral | ||||||

| 4.6.16.2. Clamshell | |||||||

| 4.6.17. EVR | REBOA or other type of EVR | ||||||

| 4.6.18. IABP | |||||||

| 4.6.19. Other | |||||||

| 4.6.20. None | |||||||

| 4.7. | Disability- related procedures | Categorical | 4.7.1. Fracture reduction | Check box | Procedures performed by p-EMS | For each mission | |

| 4.7.2. Fracture splinting | |||||||

| 4.7.3. Spinal immobilization | |||||||

| 4.7.4. Spinal protection | |||||||

| 4.7.5. Therapeutic hypothermia | |||||||

| 4.7.6. Thermal protection | |||||||

| 4.7.7. Amputation | |||||||

| 4.7.8. Other | |||||||

| 4.8. | Other procedures | Categorical | 4.8.1. General anaesthesia | Check box | Procedures performed by p-EMS | For each mission | |

| 4.8.2. Sedation | |||||||

| 4.8.3. Regional anaesthesia | |||||||

| 4.8.4. Incubator | |||||||

| 4.8.5. NO given | |||||||

| 4.8.6. ECMO | |||||||

| 4.8.7. Resuscitative caesarean delivery/perimortem hysterotomy | |||||||

| 4.8.8. Other | |||||||

| 4.8.9. None | |||||||

| 4.9. | Medications administered | Categorical | 4.9.1. Opioids | Check box | Type of medication administered by p-EMS | For each mission | |

| 4.9.2. Analgesics except opioids | |||||||

| 4.9.3. Anaesthetics | |||||||

| 4.9.4. Antiarrhythmics | |||||||

| 4.9.5. Antibiotics | |||||||

| 4.9.6. Antidotes | |||||||

| 4.9.7. Antiemetics | |||||||

| 4.9.8. Antiepileptic | |||||||

| 4.9.9. Antihypertensive | |||||||

| 4.9.10. Bronchodilators | |||||||

| 4.9.11. Diuretic | |||||||

| 4.9.12. Electrolytes | |||||||

| 4.9.13. Fluids (not for keep-line open) | |||||||

| 4.9.14. NMBA | |||||||

| 4.9.15. Procoagulant | |||||||

| 4.9.16. Fibrinolytic | |||||||

| 4.9.17. Sedatives | |||||||

| 4.9.18. Steroids | |||||||

| 4.9.19. Thrombolytics | |||||||

| 4.9.20. Vasoactive | |||||||

| 4.9.21. Tranexamic acid | |||||||

| 4.9.22. Other | |||||||

| 4.9.23. None | |||||||

| 4.10. | Hospital pre-alert done | Categorical | 4.10.1. Yes | Bullet list | Physician has informed receiving hospital of patient state before arriving at the emergency room | For each mission | |

| 4.10.2. No | |||||||

SpO2 Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation, EtCO2 End-tidal carbon dioxide, ECG Electrocardiogram FAST- Focused assessment with sonography for trauma, p-EMS Physician-staffed emergency medical services, POC Point of care, NMBA Neuromuscular blocking agent, ETI Endotracheal Intubation, SAD Supraglottic airway device, NIV Non-invasive ventilation, FiO2 Fraction of inspired oxygen, PEEP Positive end-expiratory pressure, i.v intra venous, PRBC Packed red blood cells, REBOA Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta, EVR Endovascular resuscitation, IABP Intra-aortic balloon pump, NO Nitric oxide, ECMO Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Table 5.

Mission outcome and quality indicators

| Data variable number | Main data variable name | Type of data | Data variable categories or values | Data variable sub-categories or values | Type | Definition of data variable | How often should variable be reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5. Mission outcome and quality indicators | |||||||

| 5.1. | Mission outcome | Categorical | 5.1.1. Patient left at scene | Check box | Patient left by p-EMS at scene. If necessary, taken to GP or other | For each mission | |

| 5.1.2. Patient taken to hospital, not escorted by p-EMS | To hospital by EMS or other | ||||||

| 5.1.3. Patient taken to hospital, escorted by p-EMS | |||||||

| 5.1.4. Patient declared dead on arrival at hospital | |||||||

| 5.1.5. Patient declared dead at scene | |||||||

| 5.1.6. Discharged alive from scene | Patient is alive when leaving scene | ||||||

| 5.1.7. Transported to hospital in cardiac arrest with ongoing CPR | |||||||

| 5.1.8. Patient alive at handover | Patient is alive when p-EMS hand over patient to hospital/GP/EMS unit or other | ||||||

| 5.1.9. Patient alive at discharge from hospital | |||||||

| 5.1.10. Patient alive at 30 days | |||||||

| 5.2. | Was the patient’s “post-p-EMS” followed up and registered? | Categorical | Bullet list | 30-day outcome or outcome at discharge from hospital | For each mission | ||

| 5.2.1. Yes | |||||||

| 5.2.2. No | |||||||

| 5.2.3. Unknown | |||||||

| 5.3. | Intubation success | Categorical | 5.3.1. Yes, on first attempt | Bullet list | Successful ETI by p-EMS | For each mission | |

| 5.3.2. Yes, after two or more attempts | |||||||

| 5.3.3. No | |||||||

| 5.4. | Complications to ETI | Categorical | 5.4.1. Yes | 5.4.1.1. SpO2 < 90% (at any time) | Check box | For each mission | |

| 5.4.1.2. Blood pressure below 90 (at any time) | |||||||

| 5.4.1.3. If TBI: Blood pressure below 120 (at any time) | |||||||

| 5.4.1.4. Blood pressure above 200 (at any time) | |||||||

| 5.4.1. 5. Cardiac arrest or severe, clinically significant bradycardia in relation to the procedure | |||||||

| 5.4.2. No | No complications to ETI | ||||||

| 5.5. | Patient with MI | Categorical | 5.5.1. Transferred to PCI centre? | 5.5.1.1. Yes | Bullet list | Patient meets criteria for myocardial infarction | For each mission |

| 5.5.1.2. No | |||||||

| 5.5.2. On-scene time | Number | ||||||

| 5.6. | Stroke patients | Categorical | 5.6.1. Transferred to a stroke centre? | 5.6.1.1 Yes | Bullet list | All patients considered as having stroke by p-EMS | For each mission |

| 5.6.1.2 No | |||||||

| Continuous | 5.6.2. On-scene time | Number | |||||

| 5.7. | Cardiac arrest patients | Categorical | 5.7.1. Did patient achieve ROSC for more than 5 min | 5.7.1.1. Yes | Bullet list | Patients with cardiac arrest | For each mission |

| 5.7.1.2. No | |||||||

| Categorical | 5.7.2. If ROSC: patient transferred to a PCI centre? | 5.7.2.1. Yes | Bullet list | ||||

| 5.7.2.2. No | |||||||

| 5.8. | Pain | Categorical | 5.8.1. Was the patient’s pain VAS score reduced below 4? | 5.8.1.1. Yes | Bullet list | For each mission | |

| 5.8.1.2. No | |||||||

| 5.8.1.3. Unknown | |||||||

| 5.8.2. Did the prehospital treatment reduce pain or otherwise control/improve the subjective symptoms and well-being? | 5.8.2.1. Yes | As defined by attending p-EMS | |||||

| 5.8.2.2. No | |||||||

| 5.8.2.3. Unknown | |||||||

| 5.9. | Did the prehospital interventions improve or stabilize the vital functions? | Categorical | 5.9.1. Yes | Bullet list | As defined by attending p-EMS | For each mission | |

| 5.9.2. No | |||||||

| 5.9.3. Unknown | |||||||

| 5.10. | Adverse events during mission | Categorical | 5.10.1. Adverse operational events | Check box | Missing material or teamwork issues during mission | For each mission | |

| 5.10.2. Adverse medical events | Any adverse medical events during mission | ||||||

EMS Emergency medical services, p-EMS physician-staffed emergency medical services, GP General practitioner,

CPR Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ETI Endotracheal intubation, SpO2 Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation, TBI Traumatic brain injury, PCI Percutaneous coronary intervention, MI Myocardial infarction, ROSC Return of spontaneous circulation, VAS Visual analogue scale

Discussion

Main findings

Using Delphi methodology, we have updated a template for standard documentation in p-EMS. The new dataset includes new data variables and the template was expanded from 45 to 73 main variables.

Fixed system variables

Throughout the world, there are large differences between p-EMS [21–23], and fixed system variables are important to analyse any influence of system factors and compare systems [11, 24]. The experts suggested reporting all fixed system variables annually. Furthermore, the experts chose to include two variables related to quality. The reason for including these data in this section is that they describe the quality of the system rather than the quality delivered during each mission.

Event operational descriptors

There is no consensus in the literature on how to report mission times [15, 25, 26] and the experts had several suggestions, i.e., exact times (hh:mm), time intervals (dispatch time, on-scene time, etc.) and time reported as year/month/day/hour of event. Response time (time from unit is dispatched to at patient side), on-scene time and transport time (from patient leaving the scene to arrival at the hospital) and time from alarm to arrival at the hospital are all reported in various templates. We argue that by reporting exact times, all desired time intervals can easily be calculated; therefore, exact times should be documented.

The time of the event is usually not possible to accurately identify. In trauma, the time of the event will be distinct, but for other diagnoses a clearly defined start time is often missing. The time when a call is received at the emergency medical communication centre (EMCC) is a distinct time that is easy to document, substituting for the time of the event. This was also emphasized by the experts.

P-EMS differ in service profile, and documenting dispatch type is important for benchmarking. Some services are dispatched to all types of emergency missions, whereas others are dispatched to specific types, e.g., trauma. Some services have an extensive workload due to consultation responsibilities and medical direction for ordinary EMS. This may affect availability if work hours are restricted.

Patient descriptors.

Comorbidity is an important risk adjustment measure, but there is no consensus on comorbidity reporting. The original template for reporting in p-EMS used the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status (ASA-PS) scale in a dichotomized form. However, using full ASA-PS scale has been found to be feasible in p-EMS [27], and it is recommended by the experts.

Reporting the present medical problem is crucial for benchmarking. P-EMS have traditionally reported symptoms, but point-of-care diagnostical options are increasingly available, allowing more precise pre-hospital diagnoses [28–30].

The experts recommended reporting physiological data at two different time points: at arrival of the p-EMS and at hand-over or the end of patient care. This corresponds with the original template. Reporting data at two different time points allows for monitoring changes in the patient state and may serve as a surrogate measure for p-EMS performance [31]. For SBP and SpO2, the experts also suggest reporting the lowest value measured. Hypotension is an independent predictor of mortality for traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients [32], and reporting the lowest SBP value will capture hypotensive episodes. Further, automated data capture from monitors are increasingly available, enabling continuous measurement of physiological variables. Continuous reporting may capture dynamic changes in patient state, thereby increasing the precision of p-EMS research.

Pain is frequent in the p-EMS patient population, and pain relief is considered good clinical practice [33]. The original template used a three-part scale for reporting pain while the expert group of the revised template suggest reporting pain according to the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) [34].

Process mapping variables

The resulting physiological effects of p-EMS treatment and its relation to outcome remains largely unknown in pre-hospital critical care. Such changes in physiology have earlier been difficult to capture but doing so is now more feasible due to technological developments. The experts emphasized this, and as such an expansion of the process mapping section was suggested.

Mission outcome and quality indicators

To date, there is no agreement on standard quality indicators in p-EMS but Haugland et al. recently developed a set of quality indicators for p-EMS [35]. Several of these indicators are documented in the revised template but under various sections. Additionally, the experts suggested several other context-specific quality variables related to the individual patient, but these are yet to be validated.

The experts recommend an event-specific long-term outcome measure to be included on a regular basis. The feasibility of capturing this variable as part of a standardized documentation in the p-EMS population remains to be determined.

General discussion

Several consensus-based templates for reporting in EMS and p-EMS have been created (e.g., trauma, airway handling and cardiac arrest) [14, 15, 26, 36], and studies have proven that data collection according to such templates are feasible [12, 16, 37]. However, to increase the relevance of templates, variables should be coordinated. Of 26 variables in the template on quality indicators in p-EMS [35], five are identical to variables in the current template, six can easily be calculated and three are partially similar. Thus, little extra effort is required to document according to both templates. We believe that the coordination of variables and linking of templates will add value by reducing workload and increasing data capture, thereby facilitating future p-EMS research.

P-EMS are constantly developing, with new diagnostic and therapeutic options available, e.g. pre-hospital blood products, Tranexamic acid, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), thoracotomy and endovascular resuscitation on-scene. To capture these important trends, templates need to be updated regularly. Additionally, the variables shown to be not feasible to document should either be changed or removed. Physiological variables are often reported to be the most often missing variables [38, 39]. In the original template we found the feasibility of collecting physiological data to be good [16], and these variables were not substantially changed in the updated template. Thus, we expect feasibility to be good for physiological variables in the updated template as well.

To be able to compare outcomes, data must be unambiguously defined [26]. A data dictionary with precise definitions will be created for the present template. Furthermore, when implementing the template, it is important to ensure that all requested data are collected. Each service is free to choose whatever supplementary variables it wants, but all core variables should be captured by default, thereby facilitating future research.

Physician-staffed services are more expensive compared to ordinary EMS services making it a limited resource. This emphasize our obligation to use the service for the right patients. Therefore, we continually should strive to identify patients where p-EMS has an additional effect.

To provide a tool for collection of high-quality data is only a first step towards the improvement of p-EMS research. The next step is implementation, which is pivotal for template success. Aiming to increase awareness of the template, we invited experts from all over Europe to participate in its development. We believe this may facilitate implementation. Furthermore, to increase the implementation rate of the template, targeted efforts, such as involvement of stakeholders and highlighting the possibilities which lies within template data research, must be initiated.

Registries (e.g. for trauma and cardiac arrest) have facilitated a large amount of research [14, 40, 41]. In p-EMS there is currently no joint register and each national service manages its own data. Furthermore, data are often registered on paper and later converted to digital format. Automated data capture from monitors and updated digitized data catchment tools could allow for complete template data to be imported directly into a common registry. This would provide a substantial opportunity for joint research. If such a registry could also link template data to outcomes and standardized coding systems for process and outcome issues, we may be able to assess e.g. for which patients p-EMS are useful, which procedures should be performed out-of-hospital and which procedures should not. However, the ethical and legal requirements of data sharing for research purposes (e.g. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)) must be taken into account and a substantial work to adhere to the current regulations are needed to succeed.

In the present study, we applied a Delphi method. This approach is in contrast with the Nominal Group Technique (NGT) that was used in the development of the original template. The classic Delphi method applies questionnaires with e-mails whereas the NGT involves a physical meeting with experts to reach a consensus [42]. The methods can also be combined into a modified NGT that starts with a Delphi process and ends with a physical meeting as a final step before consensus. Because this is an update of an existing template, we considered a physical meeting to be unnecessary. Furthermore, we wanted to ensure anonymity of the experts to prevent authors from favouring certain responses.

Reaching agreement is fundamental in Delphi studies, but a commonly accepted definition of consensus is absent [43]. In the present study we defined consensus as variables rated ≥4 (on a scale from 1 to 5) by > 70% of experts. We consider this a transparent and systematic method for reaching a consensus.

Limitations

The recruitment of experts is prone to selection bias. For recruitment we used a set of predefined criteria and recruited experts from the EUPHOREA network consisting of representatives from p-EMS throughout central Europe, UK and Scandinavia. The low number of participants (9–11 physicians) may have introduced a selection bias. However, we managed to recruit a representative cohort of p-EMS physicians representing a broad range of European p-EMS. The physician-staffed services represented in the expert group are amongst the most active services in Europe and we believe this ensures generalizability of the results and that the effect of potential selection bias is minimized. By keeping proposals anonymous, we have avoided the effect of favouring proposals from certain experts.

Conclusions

Using a Delphi method, we have updated and revised the template for reporting in p-EMS. We recommend implementing the dataset for standard reporting in p-EMS.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kirsti Strømmen Holm for the excellent help with communication with the experts and anonymizing the answers. We also thank the donors of the Norwegian Air Ambulance Foundation who by their contributions funded this study and made this project possible. We are sincerely grateful for the contributions from the p-EMS Template Collaborating Group who made this study possible.

The P-EMS Template Collaborating Group: Bjørn Hossfeld (Germany), Ivo Breitenmoser (Switzerland), Mohyudin Dingle (UK), Attila Eröss (Hungary), Francisco Gallego (Spain), Peter Hilbert-Carius (Germany), Jo Kramer-Johansen (Norway), Jouni Kurola (Finland), Leif Rognås (Denmark), Patrick Schober (The Netherlands) and Ákos Soti (Hungary).

Abbreviations

- AF

Atrial fibrillation

- AFL

Atrial flutter

- ASA-PS

The American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status

- AV-block

Atrioventricular block

- CO2

Carbon dioxide

- CPR

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- DASH1a

Definitive airway sans hypoxia/hypotension on first attempt

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- ECMO

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- EMCC

Emergency medical communication centre

- EMS

Emergency medical services

- EtCO2

End-tidal carbon dioxide

- ETI

Endotracheal Intubation

- EUPHOREA

The European Prehospital Research Alliance

- EVR

Endovascular resuscitation

- FAST

Focused assessment with sonography for trauma

- FiO2

Fraction of inspired oxygen

- GCS

Glasgow coma score

- GP

General practitioner

- I.v.

Intra venous

- IABP

Intra-aortic balloon pump

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- NAAF

Norwegian Air Ambulance Foundation

- NACA score

National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics score

- NGT

Nominal group technique

- NIV

Non-invasive ventilation

- NMBA

Neuromuscular blocking agent

- NO

Nitric oxide

- PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- PEA

Pulseless electrical activity

- PEEP

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- P-EMS

Physician-staffed emergency medical services

- POC

Point of care

- PRBC

Packed red blood cells

- REBOA

Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta

- ROSC

Return of spontaneous circulation

- SAD

Supraglottic airway device

- SaO2

Arterial oxygen saturation

- SAR

Search and rescue

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- SpO2

Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation

- SRQR

the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

- SVES

Supraventricular extrasystole

- TBI

Traumatic brain injury

- VAS

Visual analogue scale

- VESmono

Ventricular extrasystole, monomorphic

- VESpoly

Ventricular extrasystole, polymorphic

- VF

Ventricular fibrillation

- VT

Ventricular tachycardia

Authors’ contributions

All authors (KT, AJK, KGR and MR) conceived the idea and participated in designing the study. KT analysed the data, AJK, KGR and MR supervised the analysis. All the collaborators participated in the Delphi process and all collaborators and all authors approved the final version of the template. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript and all authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Norwegian Air Ambulance Foundation (NAAF) funded this project. However, the NAAF had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, writing or submitting to publication. The collaborators received no financial support for their participation in this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Regional Ethics Committee (REK 2017/2498) considered the study protocol and concluded that no ethical approval was required. The Privacy Ombudsman (NSD 58762) considered the project not to include personal information, thereby exempting the duty of notification according to the European Union (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kristin Tønsager, Email: kristin.tonsager@norskluftambulanse.no.

the P-EMS Template Collaborating Group:

Bjørn Hossfeld, Ivo Breitenmoser, Mohyudin Dingle, Attila Eröss, Francisco Gallego, Peter Hilbert-Carius, Jo Kramer-Johansen, Jouni Kurola, Leif Rognås, Patrick Schober, and Ákos Soti

References

- 1.Den Hartog D, Romeo J, Ringburg AN, Verhofstad MH, Van Lieshout EM. Survival benefit of physician-staffed helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) assistance for severely injured patients. Injury. 2015;46:1281–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andruszkow H, Lefering R, Frink M, Mommsen P, Zeckey C, Rahe K, Krettek C, Hildebrand F. Survival benefit of helicopter emergency medical services compared to ground emergency medical services in traumatized patients. Crit Care. 2013;17:R124. doi: 10.1186/cc12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frankema SP, Ringburg AN, Steyerberg EW, Edwards MJ, Schipper IB, van Vugt AB. Beneficial effect of helicopter emergency medical services on survival of severely injured patients. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1520–1526. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giannakopoulos GF, Kolodzinskyi MN, Christiaans HM, Boer C, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Zuidema WP, Bloemers FW, Bakker FC. Helicopter emergency medical services save lives: outcome in a cohort of 1073 polytraumatized patients. Eur J Emerg Med. 2013;20:79–85. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328352ac9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ringburg AN, Thomas SH, Steyerberg EW, van Lieshout EM, Patka P, Schipper IB. Lives saved by helicopter emergency medical services: an overview of literature. Air Med J. 2009;28:298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.amj.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters J, van Wageningen B, Hendriks I, Eijk R, Edwards M, Hoogerwerf N, Biert J. First-pass intubation success rate during rapid sequence induction of prehospital anaesthesia by physicians versus paramedics. Eur J Emerg Med. 2015;22:391–394. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruger AJ, Lockey D, Kurola J, Di Bartolomeo S, Castren M, Mikkelsen S, Lossius HM. A consensus-based template for documenting and reporting in physician-staffed pre-hospital services. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2011;19:71. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-19-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popal Z, Bossers SM, Terra M, Schober P, de Leeuw MA, Bloemers FW, Giannakopoulos GF. Effect of physician-staffed emergency medical services (P-EMS) on the outcome of patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a review of the literature. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23:730–739. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2019.1575498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fevang E, Lockey D, Thompson J, Lossius HM. The top five research priorities in physician-provided pre-hospital critical care: a consensus report from a European research collaboration. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2011;19:57. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-19-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engel DC, Mikocka-Walus A, Cameron PA, Maegele M. Pre-hospital and in-hospital parameters and outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury: a comparison between German and Australian trauma registries. Injury. 2010;41:901–906. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lossius HM, Kruger AJ, Ringdal KG, Sollid SJ, Lockey DJ. Developing templates for uniform data documentation and reporting in critical care using a modified nominal group technique. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013;21:80. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-21-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ringdal KG, Lossius HM, Jones JM, Lauritsen JM, Coats TJ, Palmer CS, Lefering R, Di Bartolomeo S, Dries DJ, Soreide K. Collecting core data in severely injured patients using a consensus trauma template: an international multicentre study. Crit Care. 2011;15(R237). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Engel DC. Standardizing data collection in severe trauma: call for linking up. Crit Care. 2012;16:105. doi: 10.1186/cc10561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perkins GD, Jacobs IG, Nadkarni VM, Berg RA, Bhanji F, Biarent D, Bossaert LL, Brett SJ, Chamberlain D, de Caen AR, et al. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update of the Utstein Resuscitation Registry Templates for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: a statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa, Resuscitation Council of Asia); and the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation. Circulation. 2015;132:1286–1300. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sunde GA, Kottmann A, Heltne JK, Sandberg M, Gellerfors M, Kruger A, Lockey D, Sollid SJM. Standardised data reporting from pre-hospital advanced airway management - a nominal group technique update of the Utstein-style airway template. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2018;26:46. doi: 10.1186/s13049-018-0509-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tonsager K, Rehn M, Ringdal KG, Lossius HM, Virkkunen I, Osteras O, Roislien J, Kruger AJ. Collecting core data in physician-staffed pre-hospital helicopter emergency medical services using a consensus-based template: international multicentre feasibility study in Finland and Norway. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:151. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-3976-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruger AJ, Skogvoll E, Castren M, Kurola J, Lossius HM. Scandinavian pre-hospital physician-manned emergency medical services--same concept across borders? Resuscitation. 2010;81:427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy A, Wakai A, Walsh C, Cummins F, O'Sullivan R. Development of key performance indicators for prehospital emergency care. Emerg Med J. 2016;33:286–292. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2015-204793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz HP, Bigham MT, Schoettker PJ, Meyer K, Trautman MS, Insoft RM. Quality metrics in neonatal and pediatric critical care transport: a National Delphi Project. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16:711–717. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89:1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Bartolomeo S, Gava P, Truhlar A, Sandberg M. Cross-sectional investigation of HEMS activities in Europe: a feasibility study. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:201570. doi: 10.1155/2014/201570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mould-Millman NK, Dixon JM, Sefa N, Yancey A, Hollong BG, Hagahmed M, Ginde AA, Wallis LA. The state of emergency medical services (EMS) Systems in Africa. Prehosp Disast Med. 2017;32:273–283. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X17000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ong ME, Cho J, Ma MH, Tanaka H, Nishiuchi T, Al Sakaf O, Abdul Karim S, Khunkhlai N, Atilla R, Lin CH, et al. Comparison of emergency medical services systems in the pan-Asian resuscitation outcomes study countries: report from a literature review and survey. Emerg Med Australas. 2013;25:55–63. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roudsari BS, Nathens AB, Cameron P, Civil I, Gruen RL, Koepsell TD, Lecky FE, Lefering RL, Liberman M, Mock CN, et al. International comparison of prehospital trauma care systems. Injury. 2007;38:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dick WF, Baskett PJ. Recommendations for uniform reporting of data following major trauma--the Utstein style. A report of a working party of the international trauma Anaesthesia and critical care society (ITACCS) Resuscitation. 1999;42:81–100. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9572(99)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ringdal KG, Coats TJ, Lefering R, Di Bartolomeo S, Steen PA, Roise O, Handolin L, Lossius HM. The Utstein template for uniform reporting of data following major trauma: a joint revision by SCANTEM, TARN, DGU-TR and RITG. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2008;16:7. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-16-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tønsager K, Rehn M, Krüger AJ, Røislien J, Ringdal KG. Kan luftambulanseleger skåre ASA pre-hospitalt? In Høstmøtet 2017. Oslo: NAF forum; 2017:46.

- 28.Hov MR, Zakariassen E, Lindner T, Nome T, Bache KG, Roislien J, Gleditsch J, Solyga V, Russell D, Lund CG. Interpretation of brain CT scans in the field by critical care physicians in a Mobile stroke unit. J Neuroimaging. 2018;28:106–111. doi: 10.1111/jon.12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walter S, Kostopoulos P, Haass A, Keller I, Lesmeister M, Schlechtriemen T, Roth C, Papanagiotou P, Grunwald I, Schumacher H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with stroke in a mobile stroke unit versus in hospital: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:397–404. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergmann I, Buttner B, Teut E, Jacobshagen C, Hinz J, Quintel M, Mansur A, Roessler M. Pre-hospital transthoracic echocardiography for early identification of non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Crit Care. 2018;22:29. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1929-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reid BO, Rehn M, Uleberg O, Kruger AJ. Physician-provided prehospital critical care, effect on patient physiology dynamics and on-scene time. Eur J Emerg Med. 2018;25:114–119. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aiolfi A, Benjamin E, Khor D, Inaba K, Lam L, Demetriades D. Brain Trauma Foundation guidelines for intracranial pressure monitoring: compliance and effect on outcome. World J Surg. 2017;41:1543–1549. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-3898-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scholten AC, Berben SA, Westmaas AH, van Grunsven PM, de Vaal ET, Rood PP, Hoogerwerf N, Doggen CJ, Schoonhoven L. Pain management in trauma patients in (pre) hospital based emergency care: current practice versus new guideline. Injury. 2015;46:798–806. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wewers ME, Lowe NK. A critical review of visual analogue scales in the measurement of clinical phenomena. Res Nurs Health. 1990;13:227–236. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haugland H, Rehn M, Klepstad P, Kruger A. Developing quality indicators for physician-staffed emergency medical services: a consensus process. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2017;25:14. doi: 10.1186/s13049-017-0362-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cummins RO, Chamberlain DA, Abramson NS, Allen M, Baskett PJ, Becker L, Bossaert L, Delooz HH, Dick WF, Eisenberg MS, et al. Recommended guidelines for uniform reporting of data from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the Utstein style. A statement for health professionals from a task force of the American Heart Association, the European resuscitation council, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Australian resuscitation council. Circulation. 1991;84:960–975. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.84.2.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okubo M, Komukai S, Izawa J, Gibo K, Kiyohara K, Matsuyama T, Kiguchi T, Iwami T, Callaway CW, Kitamura T. Prehospital advanced airway management for paediatric patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A nationwide cohort study. Resuscitation. 2019;145:175–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Laudermilch DJ, Schiff MA, Nathens AB, Rosengart MR. Lack of emergency medical services documentation is associated with poor patient outcomes: a validation of audit filters for prehospital trauma care. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Reilly GM, Cameron PA, Jolley DJ. Which patients have missing data? An analysis of missingness in a trauma registry. Injury. 2012;43:1917–1923. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2012.07.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Reilly GM, Joshipura M, Cameron PA, Gruen R. Trauma registries in developing countries: a review of the published experience. Injury. 2013;44:713–721. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shivasabesan G, Mitra B, O'Reilly GM. Missing data in trauma registries: a systematic review. Injury. 2018;49:1641–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:655–662. doi: 10.1007/s11096-016-0257-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM, Wales PW. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.